Archive for the 'Books' Category

The adolescent window

DB here:

Last month I visited the University of Texas at Austin. I had a great time, with wonderful people and conversation. The food was tasty too. There was a lot of talk, and one question in particular set me thinking.

In his Film History seminar, Professor Charles Ramirez Berg asked me what movie made me decide to study film. Before I knew what I was saying, I admitted that unlike most people who write about movies, no single movie, nor even a handful of movies, pushed me in this direction. I had no cinematic epiphany.

Nor did I have the sort of childhood that seems archetypal for film geeks. You know the tale. I grew up in New York/ Chicago/ LA and went to the movies every day, sometimes twice or more. I practically lived at the [insert colorful but rundown movie house here]. When I wasn’t at the movies I was watching little-known film noirs/ Monograms/ Budd Boettichers on TV into the night. By the time I could vote, I’d seen thousands of movies, and King Kong at least five times.

This wasn’t me. I grew up on a farm. I saw at most one or two movies a week on those Saturday afternoons when my family went to the town ten miles away. I saw what every kid saw—Disney, Martin and Lewis, Francis the Talking Mule. I did sometimes watch Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto movies on the couple of TV channels we could pull in, but I didn’t saturate myself. About age thirteen I started to get interested in film by reading about it, in books like Arthur Knight’s The Liveliest Art and Paul Rotha’s The Film Till Now. These were my guides to what to watch on TV. So yes, I did stay up late occasionally, but to see bona fide classics like Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons. The joys of Joseph H. Lewis and Robert Siodmak had to wait until in 1963 my hands closed around the Film Culture issue devoted to Andrew Sarris’ American Directors survey.

So I became a film wonk through years of accretion, gradually seeing more and more in high school (once I could drive a car) and college (running the film society) and then deciding to go to graduate school.

But I did find an answer to Charles’ question. I said that my childhood was far more steeped in TV and radio than in movies. Afterward I realized that certain books and magazines had a big influence on me as well.

What follows may seem narcissistic nostalgia, but I do have a general point. It’s the Law of the Adolescent Window:

Between the ages of 13 and 18, a window opens for each of us. The cultural pastimes that attract us then, the ones we find ourselves drawn to and even obsessive about, will always have a powerful hold. We may broaden our tastes as we grow out of those years—we should, anyhow—but the sports, hobbies, books, TV, movies, and music that we loved then we will always love.

The corollary is the Law of the Midlife/ Latelife Return:

As we age, and especially after we hit 40, we find it worthwhile to return to the adolescent window. Despite all the changes you’ve undergone, those things are usually as enjoyable as they were then. You may even see more in them than you realized was there. Just as important, you start to realize how the ways you passed your idle hours shaped your view of the world—the way you think and feel, important parts of your very identity.

Let me get specific.

The view from my window

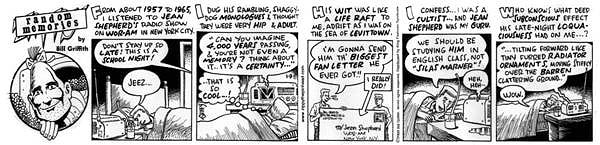

Jean Shepherd. Photo by Fred W. McDarrah.

I was born in 1947 and graduated from high school in 1965. What was my angle of view onto the pop-culture landscape in 1960-1965?

Reading: I read a lot of classic and contemporary American literature, especially Twain and Faulkner. Also a lot of nonfiction, especially Barzun, Orwell, and Kenneth Burke. But more eagerly I soaked up detective stories. Not the hardboiled ones, though I loved Hammett’s Red Harvest. My favorites were Sherlock Holmes, Wilkie Collins, and the Golden Age classics: Agatha Christie, Margery Allingham, John Dickson Carr/ Carter Dickson, Ellery Queen, and Rex Stout. I now realize that from these skilful storytellers I was absorbing lessons in narrative construction, as well as a taste for artifice.

More specifically, I was learning something I could only much later make explicit: Popular culture undertakes formal experimentation as intriguing as anything in the official avant-garde. Ellery Queen’s openly fabulist novels take a central motif—a nursery rhyme, a pun, the Ten Commandments—and then show how it informs action, character psychology, even chapter breaks. John Dickson Carr’s books are like conjuring tricks, with the magician brandishing the clues and steering you away from the trap doors and collapsable top hats. Who else but Carr would call a novel The Reader Is Warned? Among the moderns, perhaps only Ed McBain has the Golden Age flair for creating a multilayered plot based on a central image like ice or a wedge, and he does it within the frame of the most purportedly realistic mode, the police procedural.

Or take a book I’ve probably read twenty times, Anthony Berkeley’s The Poisoned Chocolates Case (1929). Six eminent lawyers, writers, and amateur sleuths have formed a club, the Crimes Circle. They’re presented with a current murder case and challenged to crack it. At six nights of Circle meetings, each one fields a solution, only to have it shot down. Sort of a grad seminar in homicide.

Admirers of film noir and the hardboiled school, who are in the majority now, would complain that this is just the sort of airless exercise that turned the detective story into a crossword puzzle. Yet there is tension whenever we play off competing answers to a question; anyone who thinks that empirical reasoning is bloodless should read a scientist’s biography. Out of a handful of clues and three or four suspects, The Poisoned Chocolates Case conjures up six detailed but mutually exclusive solutions. At the end, there’s a purely aesthetic pleasure in watching the puzzle snap into a surprising whole that integrates aspects of all the failed answers. As a cherry on the sundae, we’re rewarded with one of the niftiest last lines in crime fiction: “Nobody enlightened him.”

My tastes in the genre have broadened. Now I read and reread Le Carré, Rendell, Hillerman, Westlake/ Stark, Bloch, and the procedurals, especially Rankin. Of course I like Highsmith and Elmore Leonard. Robert Barnard and Peter Dickinson can sometimes evoke Golden Age knottiness. But when I want formal highjinks, I pack a classic in my carry-on and I’m seldom disappointed.

On the Austin trip it was Stout’s The Rubber Band, an elegant adventure of Archie Goodwin and Nero Wolfe.

I’ve registered my admiration for Stout elsewhere on this blog; I consider him one of the great masters of American vernacular prose. The Rubber Band is one of his best, and not just because every page boasts at least one of Archie’s irresistible sentences about Wolfe.

I’ve registered my admiration for Stout elsewhere on this blog; I consider him one of the great masters of American vernacular prose. The Rubber Band is one of his best, and not just because every page boasts at least one of Archie’s irresistible sentences about Wolfe.

Since he only went outdoors for things like earthquakes and holocausts, he was rarely guilty of movement except when he was up on the roof with Horstmann and the orchids, from nine to eleven in the morning and four to six in the afternoon, and there was no provision there for pole vaulting.

That’s writing.

TV, I now realize, tutored me further in the unbridled audacity of popular culture. Granted, in certain circles I’ve been known to say unenthusiastic things about TV. Nowadays I don’t watch anything but The Simpsons and Keith Olbermann. But who can deny the past? I’m a creature of the box.

My parents got TV early, in the early 1950s, and my sisters and I spent many a winter afternoon in front of cartoons, the Disney show, and Roy Rogers. But I didn’t like the official hits, like Gunsmoke and Bonanza. As I got older, I was snagged by grownup shows like Jackie Cooper’s Hennessey and the short-lived It’s a Man’s World. Why? I don’t know. Perhaps they showed how badinage could mingle with serious drama. No mystery about Ernie Kovacs, though, whose nuttiness delighted me in the way that Monty Python would capture the kids of the 1970s. And like everybody else, I was haunted by a weekly visit to the Twilight Zone.

But above all stood George and Gracie. When I started to get what they were about, their program was ripening into its baroque phase. More than individual shows, I remember the brilliant central conceit. Gracie would hatch a wacko scheme, usually recruiting the hapless Harry von Zell as her minion. George would get suspicious and retire to his den to tune in the very show we were watching. He was then in a position to block her maneuvers, usually by tormenting von Zell. The idea that George could simply watch his own program still seems a stroke of genius. Artistic form, I must have realized subconsciously, can always be turned into a dizzy game. M. Godard, Ozu-san, meet Burns and Allen.

But above all stood George and Gracie. When I started to get what they were about, their program was ripening into its baroque phase. More than individual shows, I remember the brilliant central conceit. Gracie would hatch a wacko scheme, usually recruiting the hapless Harry von Zell as her minion. George would get suspicious and retire to his den to tune in the very show we were watching. He was then in a position to block her maneuvers, usually by tormenting von Zell. The idea that George could simply watch his own program still seems a stroke of genius. Artistic form, I must have realized subconsciously, can always be turned into a dizzy game. M. Godard, Ozu-san, meet Burns and Allen.

The radio was constantly on in our house, with my mother listening to Arthur Godfrey or Art Linkletter. These geezers were intolerable to my teenage tastes. Give me my two main sources of aural pleasure: WKBW radio and Jean Shepherd.

WKBW was a radio station out of Buffalo. At 50,000 watts it was so powerful it tended to seep into any blank spot on the dial. Actually, the DJs probably didn’t need an antenna, since they conducted their shows at ear-splitting volume. They indulged in all the profound things that characterized radio in the 1950s: cute sound effects (car crashes, always good), music clips (audio tape made it easy), jingles and station IDs that quickly became earworms, and nonstop patter sustained by whinnies, table-pounding, and laughter at feeble jokes. KB’s promotional efforts were no less strenuous. Once the station asked the public’s help in finding a missing DJ, only to reveal that he’d gone into hiding to drum up publicity.

WKBW was a radio station out of Buffalo. At 50,000 watts it was so powerful it tended to seep into any blank spot on the dial. Actually, the DJs probably didn’t need an antenna, since they conducted their shows at ear-splitting volume. They indulged in all the profound things that characterized radio in the 1950s: cute sound effects (car crashes, always good), music clips (audio tape made it easy), jingles and station IDs that quickly became earworms, and nonstop patter sustained by whinnies, table-pounding, and laughter at feeble jokes. KB’s promotional efforts were no less strenuous. Once the station asked the public’s help in finding a missing DJ, only to reveal that he’d gone into hiding to drum up publicity.

In my day, the loudest mouth belonged to Joey Reynolds, who brayed over records and satirized rock and roll with an appalling ditty called “Rats in My Room.” When he was fired, he nailed his shoes to his boss’s door, adding a note: “Fill These.” I was happy to learn that this piece of teenage lore seems to be true, or at least so a fanatical WKBW website indicates. Joey continues on the airwaves, albeit more sedately.

Speaking of music, KB opened the adolescent window to the tunes that still move me. I was too young to like Elvis and had an affectionate but distant relation to the Beatles. My favorites came mostly from what I’ve learned to call the Brill Building sound. On 24 December every year, Kristin folds her arms in weary patience as the Drifters, Gene Pitney, Connie Francis, and Paul Anka pour forth into our living room.

Jean Shepherd was a wholly different story. The WOR signal couldn’t creep into upstate New York by day, so my bedside tube radio crackled and hissed as 11:15 p. m. approached. Would the signal pull through? It usually did. In fact it seemed to get stronger as, lying in the dark, I heard the familiar trumpet call and galloping music that announced Shep’s show. Another difference from Top 40: Here was an adult talking to a kid as if I were an adult. And an adult who lived in Manhattan! I discovered then that the media aim downward, age-wise: a teenage TV show is actually watched by pre-teens, a college show (like Shep’s) appeals most to highschoolers (like me).

Shep was one of the pioneers of long-form talk radio. He didn’t take phone calls and he seldom had guests. He claimed to be a social commentator, and he did point out the foibles of contemporary media and society. Mostly, though, he was a yarn spinner in the Twain tradition. As he told stories from his life, especially his childhood in Indiana, digressions would split off unexpectedly. Somehow, though, everything wound back to make a point–usually about the vainglory of being human. What made the stories fascinating was not only the delivery (poetic turns of phrase, a smooth, earnest voice that could sink to an urgent whisper) but their fundamental ordinariness. He told of midwestern air shows, enamel table tops, summer baseball, and disastrous Valentine’s Day parties. He celebrated the commonplace and advised his listeners to simply watch everything closely, to find the poetry and absurdity that pervade our lives. I think that my sense of humor owes a lot to him. Perhaps also my tendency to yakkiness.

Shepherd is best-known today for A Christmas Story, the movie based on some of his stories. If you’ve seen it, you’ve heard his unique voice as the narrator. But I first heard the tales of the BB gun and the Old Man’s fetishistic leg-lamp while hunched under the blankets, long after my family had gone to sleep, and Shep’s words put a movie in my head. After my nightly WOR adventures, Garrison Keillor seemed labored and condescending.

From Eugene Bergmann’s capacious book on Shepherd (1), I realize that my nighttime communion with this adult voice was shared by thousands of other kids. He fused the nonconformist sensibility of the Beats and the Hips with a Midwestern distaste for airs and pomposity. He called his fans the Night People. The enemies were the Meatballs, the Slobs, or, in a reference to a Pepsi tagline, the Sociables. He spurred his listeners to send Cassavetes money to fund Shadows; a credit to the Night People appears on the movie. Shep’s motto was “Excelsior” (sometimes, “Excelsior, you fathead”), which encapsulated both his optimism (onward and upward, keep striving) and his fatalism (remember the boy with the banner lying frozen in the snow).

Urged on by Bergmann’s book, I recently discovered a wonderful Shepherd website and a vast podcast vault of his shows, which are also available free on iTunes. (2) Broadcast a little before I started listening, the 1960 “Molded Food” episode was a great iPod companion as I wandered around the UT—Austin campus.

Put not aside childish things

I could mention more items seen through my window, such as the Village Voice, Esquire, and, inevitably, Mad magazine. But the moral should be clear. Whatever called out to you when your window opened—Grease, Patti Smith, Buckaroo Banzai, Sassy, David Bowie, Columbo, Godspell, Lord of the Rings (the book), Penn and Teller, National Lampoon, Pavement, John Hughes movies, Kurt Vonnegut, the B-52s, Earth Girls Are Easy, Beat Street, Master of Puppets, Boondock Saints, Sam Kinison, They Might Be Giants, you name it—is likely to retain its bright purity throughout your days. What’s kitsch or cheesy or retro to others is precious to you.

Make no apologies. It’s not mere nostalgia or guilty pleasure to revisit these creations. You can return to them as to old friends. Encountering them again, you remember when you took it for granted that anything was possible in your life. Their sharp, shining lines fitted your range of vision, and mostly they still do.

Your taste was unerring. These teenage passions represent a big chunk of the finest part of you. In some secret place you are still as uncomplicated as you were then.

(1) Eugene B. Bergmann, Excelsior, You Fathead! The Art and Enigma of Jean Shepherd (New York: Applause, 2005).

(2) In the iTunes store, go to “The Brass Figlagee” under Podcasts.

Thanks to Jeff Smith, Jonah Horwitz, and Dan Morgan for suggesting some things they saw through their adolescent window.

Zippy the Pinhead, by Bill Griffith.

Scribble, scribble, scribble

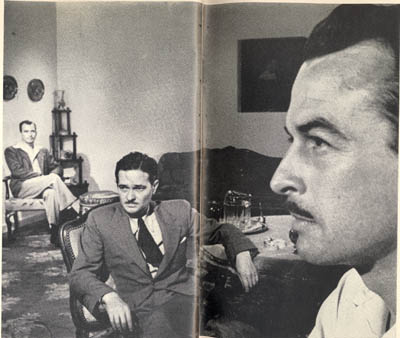

Detective (Godard, 1985).

Another damned, thick, square book! Always scribble, scribble, scribble, eh, Mr. Gibbon?

William Henry, Duke of Gloucester, 1781.

David here:

Kristin kept the blogfires burning while I traveled last week and did UW duties this one. I had a great time at the University of Georgia in Athens (but didn’t see Stipe) and at Emory in Atlanta (but didn’t see Scarlett). At both places I met sharp, energetic students and faculty. I have a couple of blog entries backlogged for posting, but now recent items relating to publications get the pole position.

First, a Japanese translation of our Film Art: An Introduction has just appeared. It’s a very handsome version of the seventh edition, rendered by Fujiki Hideaki and Kitamura Hiroshi. We’re grateful to them and to Nagoya University Press for publishing it.

First, a Japanese translation of our Film Art: An Introduction has just appeared. It’s a very handsome version of the seventh edition, rendered by Fujiki Hideaki and Kitamura Hiroshi. We’re grateful to them and to Nagoya University Press for publishing it.

Second, the University of California Press is having a big sale on many outstanding media titles, from Richard Abel’s books on French silent cinema and André Bazin’s classics of film theory to Michele Hilmes’ study of NBC television and Mike Barrier’s new Disney biography, The Animated Man. To get the discount you must sign up for an e-newsletter, but it’s not intrusive.

Among the books of mine on sale, the biggest bargain is the hardcover edition of Figures Traced in Light (2005), originally priced at $65, now going for $7.95 plus postage. (No, apparently I don’t get the full-price royalties.) You can find this item here. There are also paperback copies of Figures (going for $12.95) and of The Way Hollywood Tells It ($15.95). If you’re inclined, hurry: the sale ends on 31 October.

The biggest news, though, is that I just got my author’s copies of Poetics of Cinema, published last week. For a while Amazon was telling some people who pre-ordered it that copies won’t be available until 27 December, but now, despite what it says here, the book seems ready to ship.

The biggest news, though, is that I just got my author’s copies of Poetics of Cinema, published last week. For a while Amazon was telling some people who pre-ordered it that copies won’t be available until 27 December, but now, despite what it says here, the book seems ready to ship.

Bad news first. Poetics of Cinema is priced at $45 in paperback, with no sellers I know offering it at discount. Go ahead, say it: Very expensive. If you haven’t published a book, you may not know that authors have no say in the pricing of their work. Publishers would never set a price or price ceiling in a contract, and calculations about pricing are based on many factors, including what comparable books sell for. A high cost isn’t my preference, of course; every writer wants to reach as many readers as possible. But unless you blog or self-publish your work, the publisher sets the price.

There are some good reasons for the cost. Running to 500 fairly dense pages and containing over 500 photographs, Poetics of Cinema was a complicated book to produce. I peddled it to other publishers, but they ruled it out as too whopping an investment for them. So Routledge has priced it along lines of comparable books, reckoning in the size of the likely audience (I hope, more than 118.3 readers). I have to thank Bill Germano, then Publishing Director at Routledge, for taking a chance on this project.

From age fifteen or so I’ve been a compulsive writer. Scribble, scribble, scribble. I’ve been at work on one book or another for over thirty years. I’ve got several projects in mind for my next effort, but I’ve held back committing. Is there any point in publishing more books, at least as books?

I mean this as a serious question. Would it have made any difference to me or my readers if Poetics of Cinema appeared as pdfs, available at a price considerably less than $45? Wouldn’t I find more readers? What about variable pricing? If Radiohead can do it, why can’t I? Somebody in film studies should try putting a digital book for sale online; maybe I will. But for a few years at least, this last baggy monster will be available only in dead-tree format.

Poetics: Some puzzles

Gentlemen Marry Brunettes (Richard Sale, 1955).

If you’ve read this far, you may be interested in what the book is about. Most basically, it’s predicated on the belief that we make progress in research by asking questions. Some questions are too deep to be answered—call them mysteries—but others can be answered with a fair degree of precision and reliability. We can turn mysteries into puzzles and puzzles into plausible answers.

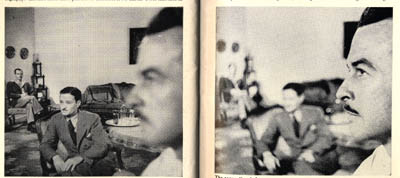

Here’s a fairly common sort of composition in Hollywood cinema of the 1940s. This shot from The Killers (1946) displays the sort of steep depth I’ve talked about at various points on this blog and in my other books.

But now here’s an equally tense confrontation at a counter, from Bad Day at Black Rock (1955), made in early CinemaScope.

It doesn’t look much like the 1940s shot. The characters stand far from us, and the figure in the foreground doesn’t loom over the background. The shot is more open, the composition more porous. And unlike The Killers, Bad Day doesn’t contain close-ups of the actors in any scenes.

So questions come to mind. Did John Sturges have to stage the scene in Bad Day this way? Did other filmmakers resort to the same choice? What factors created pressures toward this more spacious format? Could more resourceful filmmakers have done something different? And given that such shots are rare today, what changes made it possible for filmmakers in later years to create the tight anamorphic widescreen close-ups we have now (as here in Cellular)?

Despite all that has been written about CinemaScope and other early widescreen processes, no one has explored, shot by shot, what staging options were used by filmmakers. A chapter in Poetics of Cinema called “CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See Without Glasses” tries to show how filmmakers used the new format to tell their stories. This led them, I propose, to experiment with some staging strategies that, surprisingly, had precedents as far back as the 1910s.

Take another instance. We’re all familiar with recent films that present alternative futures, like Run Lola Run. A story line runs along and then is interrupted, and we switch to the same characters living a different storyline in a parallel universe. The emergence of such “forking path” movies arouses my curiosity. How do they work? How do they make their alternative-reality stories intelligible to the audience? How is it that we’re able to understand them? (After all, the notion of an infinite number of alternative universes to ours is pretty hard to get your head around.) Are such stories a brand-new innovation, or do they have precedents? (Clue: Remember A Christmas Carol?) Why do we see a cluster of these emerging in recent filmmaking?

I tackle these questions in another essay, called “Film Futures.” There I look at several such movies and try to spell out the tacit rules that filmmakers follow and that audiences pick up on. While this story format probably doesn’t constitute a genre, it does obey certain conventions, and I try to chart those. Some films also make some clever innovations in the format, which I also try to trace. The essay as well suggests how the conventions are handled differently in mass-market films like Sliding Doors and in art films like Kieślowski’s Blind Chance.

These two essays, along with the others in the book, try to explain and illustrate an approach to film studies I call film poetics. At bottom, this is an effort to explain why films are designed the way they are: how filmmakers have made certain choices in order to shape our response to their films. How do movies work? How do movies work on us?

Poetics: The project

Vagabond (Varda, 1985).

As a kind of reverse engineering, film poetics looks at both structure and texture. I argue that we ought to study how films are constructed architecturally, as revealed for instance in plot structure or narration. Poetics also concentrates on stylistic patterning, the way filmmakers organize the techniques available to the medium. Poetics traditionally deals as well with thematics, the subjects and ideas that are mobilized by filmmakers and reworked by large-scale form and cinematic style.

Put it this way: I want to know how filmmakers have confronted problems set by others, or created problems for themselves to solve. I want to know how they draw on the past to borrow or modify or reject creative strategies. I want to know filmmakers’ secrets, including the ones they don’t know they know. And I want to know how all this creative activity is shaped to the uptake of spectators in different times and places.

Some of what I’ve written on this blog could illustrate how the poetics-driven perspective works in particular cases. The book offers more such instances, probed in more detail than is possible here. Using a comparative method, I also trace out some general principles of film form and style as they have developed over history.

The book consists of fifteen essays. Some have been published before; those have been revised for this collection. Other essays are newly written. After a somewhat polemical introduction, the first part concentrates on some theoretical problems. The anchoring essay offers a general introduction to the idea of a film poetics, with several examples. (An earlier version is on pdfs here.) In the same essay, I float a model of how film viewers respond to various aspects of films. I distinguish activities of perception, comprehension, and appropriation, and I suggest that a cognitive perspective sheds light on them.

Part I also contains an essay considering how cinematic conventions work. A poetics-based approach will spend a lot of time on norms, traditions, and received routines, for these are often the basis of filmmakers’ creative choices. This essay argues that some conventions are local and require a lot of cultural knowledge, while others are cross-cultural, compelling us to study why certain cinematic strategies seem to crop up across the world.

The second part of Poetics of Cinema considers narrative, one of the most common ways in which films are organized to affect viewers. I wrote a new essay to launch this section, a wide-ranging study called “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative.” The three dimensions I consider are narration, plot structure, and the narrative world. The essay considers how each of these shapes our understanding of a film’s story. This essay ends with a discussion called “Narrators, Implied Authors, and Other Superfluities.”

Some more tightly-focused pieces follow. One is devoted to forking-path plots. Another concentrates on an odd question: What role does forgetting play in our watching a film? Cognitive theory can offer some answers, and I take Mildred Pierce as an example. There’s an update of an essay that has been something of a golden oldie in film courses, “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice.” In a supplement to that piece I suggest some new avenues of inquiry and draw on more examples, notably Varda’s Vagabond (Sans toit ni loi).

The longest piece in Part II is devoted to what I call network narratives. Prototypes of this would be Grand Hotel, Short Cuts, Crash, and Babel. This essay tries to show how a poetics of cinema shed light on this format, currently a very popular one. When I started looking at these movies, I was surprised to discover how many filmmaking traditions work in this vein; I append a filmography with nearly 250 items, and today I could update it with several more. (1) I consider how this option has developed distinctive strategies of narration, plotting, and worldmaking. I also survey some common themes running across network tales, such as the role of chance and fate. The essay finishes with more in-depth analyses of four films: Altman’s Nashville, Iosseliani’s Favoris de la lune, Anderson’s Magnolia, and Jean-Claude Guiget’s Les Passagers.

Poetics: More problems

Bus Stop (Logan, 1955).

Part III moves from questions of narrative to questions of film style, no stranger to this blog. The opening essay is a tribute to Andrew Sarris that appraises his role in making readers of my generation style-conscious. It’s the most personal piece in the book. There follows a study of Robert Reinert, a director in the German silent cinema who might have become much better known if his quite demented Nerven and Opium had been as widely seen as Caligari. The essay “Who Blinked First?” considers how our reaction to films is affected by the ways in which actors use their eyes, including how and when they blink. Big deal, huh? Actually, yes.

The monster essay in this section is the CinemaScope piece, of which I’ve given versions in lecture form over the last couple of years. I argue that some directors responded to the new widescreen technology by adapting certain norms of staging and shooting to the new format, while other filmmakers moved in more adventurous directions. The piece uses the model of problem/solution as a way to understand stylistic continuity and change, a framework I’ve floated in On the History of Film Style as well.

The last four studies in Part III are devoted to style in Asian cinema. There are two essays on Japanese film of the 1920s and 1930s, both expanded somewhat from their original versions. There I argue that we can see Japanese directors as building upon, as well as adventurously departing from, stylistic norms shared by most filmmaking countries of the period. This brace of essays fills out some ideas that I fielded in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, and they should appeal to that growing body of viewers who have developed a passion for Naruse Mikio and Uchida Tomio. It’s gratifying that several of the films I discuss, which I had to study in archives, are now circulating in touring programs.

Poetics of Cinema concludes with two studies of Hong Kong film, one surveying the stylistic tactics by which that very lively tradition excites its audience, the other analyzing the unique innovations of King Hu. The articles are companion pieces to Planet Hong Kong.

Poetics: The mysteries

A Touch of Zen (King Hu, 1970).

As an approach to answering questions about cinema, poetics blends history, criticism, and theory. It requires that we do research into the artistic history of film, looking at styles, genres, narrative modes, and other traditions. It asks for close analysis and interpretation of films. At the same time, it asks broader questions about what principles govern narrative, stylistic patterning, and the like. I’d say it obliges a historian to concentrate on aesthetics; it makes criticism more historical and theoretical; it ties theory to concrete historical conditions and the fine-grain workings of individual films.

Kenneth Burke used to say that you could get a sense of a book by looking at its first and last sentences. My book’s first essay opens this way:

Sometimes our routines seem transparent, and we forget that they have a history.

I think that this captures my concern to look closely at familiar things in film and try to make their principles a little more evident. Yet in trying to make filmmakers’ choices explicit and tracing out the principles undergirding how we make sense of movies, I’m sometimes criticized for simply stating common sense. Poetics can look bland alongside the skywriting swoops of most academic film theory. But skywriting is blurry and dissolves while you look at it. By contrast, clearly setting out some basics of filmic construction and comprehension offers a firmer place to start answering questions about how movies work and work on us.

Poetics tries to produce concrete, approximately true claims about cinema. Most film theory operates as an application, borrowing big theories of culture, identity, nationhood, and the like and then mapping them onto films. The results are usually thin. It seems to me that most film theory today is not carefully thought through or persuasively argued. For examples, see my essay in Post-Theory, the last chapter of Figures, and my comments here and here on this site.

In trying to establish reliable knowledge about cinema, we won’t answer every question and we will make false steps, but we can make progress. Film poetics is one way we film enthusiasts can join that tradition of rational and empirical inquiry which remains our most dependable path to knowledge. My introduction, though peppered with some pokes at Big Theory, has the serious purpose of making a plea for film scholars to join that tradition.

The final line of the book concludes the essay on King Hu:

The mainstream [Hong Kong] style has given us many beautiful and stirring films, but Hu’s eccentric explorations evoke something that other directors’ works seldom arouse: a sense that extraordinary physical achievement, if caught through precisely adjusted imperfections, becomes marvelous.

To get the full point you need to read the essay, but what should come through here is my concern to highlight filmmakers’ originality when I find it, and to locate it by means of a comparative method. In addition, I hope that what comes through is an appreciation of the sheer exhilaration we feel when a filmmaker has made the right, bold choice. A poetics-based approach probably can’t fully explain this feeling—it may fall under the heading of mysteries rather than puzzles—but at least it can reveal how some forces contribute to it.

My summary, and the size of the book, may leave the impression that I think that I’ve answered these questions fully. Of course I don’t. I try only to make some progress, realizing that offering answers is also an invitation to disagree, to refine the questions and tackle new ones. Nor do I think that these are the only questions that matter. We’re just starting to understand how films work and work on us, and there are a great many areas we haven’t charted. (Performance, to take a big one.) We have to start somewhere, though. I’d hope that by posing some questions and proposing some answers, Poetics of Cinema offers fruitful points of departure.

(1) Some candidates are 25 Fireman Street (1973, Hungary, István Szabó), Feast of Love (2007, US, Robert Benton), Continental—A Film without Guns (2007, Canada/ Stephane Lafleur), The Edge of Heaven (2007, Germany/ Turkey, Fatih Akin), Unfinished Stories (2007, Iran, Pourya Azarbayjani), God Man Dog (2007, Taiwan, Singing Chen [Chen Hsin-hsuan]), A Century’s End (2000, Korea, Song Neung-han), and Why Did I Get Married? (2007, US Tyler Perry).

A Moment of Innocence (Mohsen Makhmalbaf, 1996).

Do filmmakers deserve the last word?

DB here:

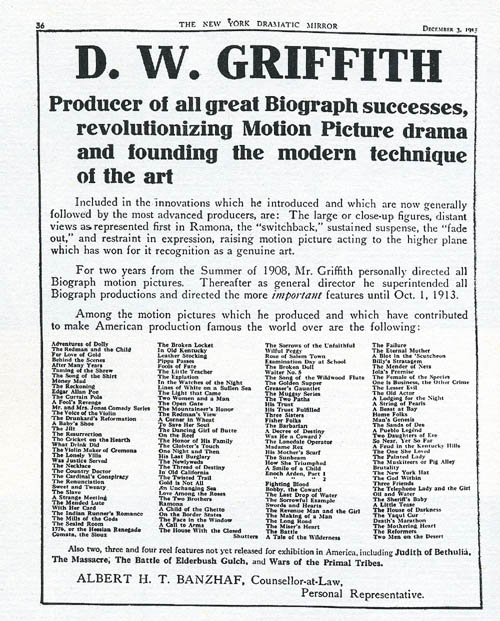

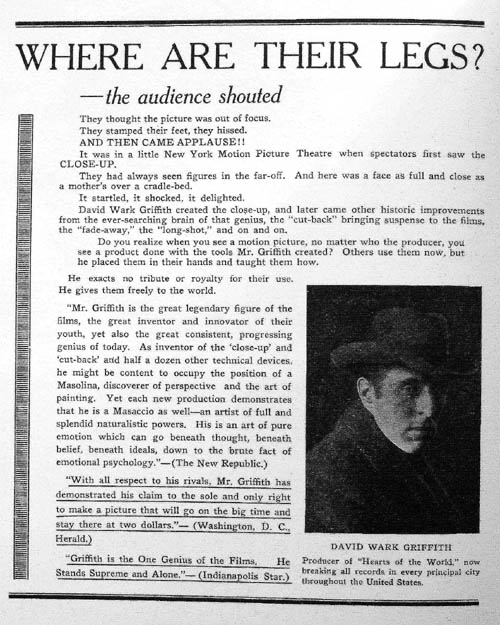

On 3 December 1913, the above advertisement appeared in the New York Dramatic Mirror. D. W. Griffith had left the American Biograph company and set out on an independent path that would lead to The Birth of a Nation and beyond. Because Biograph never credited directors, casts, or crews, he wanted to make sure that the professional community was aware of his contributions. Not only did he point out that he had made several of the most noteworthy Biograph films; he also took credit for new techniques. He introduced, he claims, the close-up, sustained suspense, restrained acting, “distant views” (presumably picturesque long-shots of the action), and the “switchback,” his term for crosscutting—that editing tactic that alternates shots of different actions occurring at the same time.

Griffith’s bid for credit was a shrewd move for his career, and it had repercussions after the stunning success of The Birth of a Nation two years later. Many historians took Griffith at his word and credited him with the breakthroughs he listed. He became known as the father of “film grammar” or “film language.” The idea hung on for decades. Here’s the normally perceptive Dwight Macdonald, criticizing Dreyer’s Gertrud for being anachronistic:

He just sets up his camera and photographs people talking to each other, usually sitting down, just the way it used to be done before Griffith made a few technical innovations. (1)

Filmmakers believed the Griffith story too. Orson Welles wrote of the “founding father” in 1960:

Every filmmaker who has followed him has done just that: followed him. He made the first close-up and moved the first camera. (2)

In the late 1970s a new generation of early-cinema scholars gave us a more nuanced account of Griffith’s place in history. They pointed out that most of the innovations he claimed either predated his Biograph work, (3) or appeared simultaneously and independently in Europe and in other American films. Some Griffith partisans had already conceded this, but they maintained that he was the great synthesizer of these devices, and that he used them with a vigor and vividness that surpassed the sources.

That judgment seems right in part, but Eileen Bowser, Tom Gunning, Barry Salt, Kristin Thompson, Joyce Jesniowski, and other early-cinema researchers have drawn a more complicated picture. (4) Griffith did speed up cutting and devote an unusual number of shots to characters entering and leaving locales. But these innovations weren’t usually recognized as original by previous historians. More interestingly, much of what Griffith did was not taken up by his successors. His technique was idiosyncratic in many respects. By 1915 younger directors like Walsh, Dwan, and DeMille were forging a smoother style that would be more characteristic of mainstream storytelling cinema than Griffith’s somewhat eccentric scene breakdowns. Instead of creating film language, he spoke a forceful but often unique dialect.

The New York Dramatic Mirror ad coaxes me to reflect on how filmmakers have shaped critics’ and historians’ responses to their work. Hawks and Hitchcock developed a repertory of ideas, opinions, and anecdotes to be trotted out on any occasion. Today, directors write books, give interviews, appear on infotainment shows, and provide DVD commentary. We know that many of the talking points are planned as part of the film’s publicity campaign, and journalists dutifully follow the lead. (In Chapter 4 of The Frodo Franchise, Kristin discusses how this happened with Lord of the Rings.) For many decades, in short, filmmakers have been steering critics and viewers toward certain ways of understanding their films. How much should we be bound by the way the filmmaker positions the film?

Deep focus and deep analysis

Citizen Kane (1941).

Determining intentions is tricky, of course. Still, I think that in many cases we can reconstruct a plausible sense of an artist’s purposes on the basis of the artwork, the historical context, surviving evidence, and other information. (5) This may or may not correspond to what the artist says on a particular occasion. For now, I want simply to point to one instance in which filmmakers have shaped critical uptake, with results that are both illuminating and limiting.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, André Bazin, one of the great theorists and critics of cinema, argued that Orson Welles and William Wyler created a sort of revolution in filmmaking. They staged a shot’s action in several planes, some quite close to the camera, and maintained more or less sharp focus in all of them. Bazin claimed that Welles’ Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons and Wyler’s The Little Foxes and The Best Years of Our Lives constituted “a dialectical step forward in film language.”

Their “deep-focus” style, he claimed, produced a more profound realism than had been seen before because they respected the integrity of physical space and time. According to Bazin, traditional cutting breaks the world into bits, a series of close-ups and long shots. But Welles and Wyler give us the world as a seamless whole. The scene unfolds in all its actual duration and depth. Moreover, their style captured the way we see the world; given deep compositions, we must choose what to look at, foreground or background, just as we must choose in reality. Bazin wrote of Wyler:

Thanks to depth of field, at times augmented by action taking place simultaneously on several plane, the viewer is at least given the opportunity in the end to edit the scene himself, to select the aspects of it to which he will attend. (6)

While granting differences between the directors, Bazin said much the same about Welles, whose depth of field “forces the spectator to participate in the meaning of the film by distinguishing the implicit relations” and creates “a psychological realism which brings the spectator back to the real conditions of perception” (7).

In addition, Bazin pointed out, this sort of composition was artistically efficient. The deep shot could supply both a close-up and a long-shot in the same framing—a synthesis of what traditional editing had given in separate shots. Bazin wove all these ideas into a larger theory that cinema was inherently a realistic medium, bound to photographic recording, and Welles and Wyler had discovered one path to artistic expression without violating the medium’s biases.

There are many objections to Bazin’s argument, some of which I’ve rehearsed in On the History of Film Style. My point here is that Bazin was presenting analytical points that stemmed from publicity put out by Welles, Wyler, and especially their talented cinematographer Gregg Toland.

In a 1941 article in American Cinematographer, Toland talked freely about how he sought “realism” in Citizen Kane. The audience must feel it is “looking at reality, rather than merely a movie.” Key to this was avoiding cuts by means of long takes and great depth of field, combining “what would conventionally be made as two separate shots—a close-up and an insert—into a single, non-dollying shot.”(8) Toland defended his sometimes extreme stylistic experimentation on grounds of realism and production efficiency, criteria that carried some weight in his professional community of cinematographers and technicians. (9)

Toland’s campaign for his style addressed the general public too. For Popular Photography he wrote an article (10) explaining again that his “pan-focus” technique captured the conditions of real-life vision, in which everything appears in sharp focus. A still broader audience encountered a Life feature in the same year (11), explaining Toland’s approach with specially-made illustrations. Two samples show selective focus, one focused on the background, the other on the foreground.

An accompanying photo shows pan-focus at work, with Toland in frame center, an actor in the background, and Toland’s camera assistant in the foreground.

In sum, Toland’s publicity prepared viewers, both professional and nonprofessional, for an odd-looking movie.

Throughout the 1940s, Welles and Wyler wrote and gave more interviews, often insisting that their films invited greater participation on the part of spectators. In a crucial 1947 statement, Wyler noted:

Gregg Toland’s remarkable facility for handling background and foreground action has enabled me over a period of six pictures he has photographed to develop a better technique for staging my scenes. For example, I can have action and reaction in the same shot, without having to cut back and forth from individual cuts of the characters. This makes for smooth continuity, an almost effortless flow of the scene, for much more interesting composition in each shot, and lets the spectator look from one to the other character at his own will, do his own cutting. (12)

Some of this publicity material made its way into French translation after the liberation of Paris, just as Kane, The Little Foxes, and other films were arriving too. Bazin and his contemporaries picked up the claims that these films broke the rules. Deep-focus cinematography became, in the hands of critics, a revolutionary new technique. They presented it as their discovery, not something laid out in the films’ publicity.

But the case involved, as Huck Finn might say, some stretchers. Watching the baroque and expressionist Kane, it’s hard to square it with normal notions of realism, and we may suspect Toland of special pleading. Some of Toland’s purported innovations, such as low-angle shots showing ceilings, had been seen before. Even the signature Toland look, with cramped, deep compositions shot from below, can be found across the history of cinema before Kane. Here is a shot from the 1939 Russian film, The Great Citizen, Part 2 by Friedrich Ermler.

More seriously, some of Toland’s accounts of Kane swerve close to deception. For decades people presupposed that dazzling shots like these were made with wide-angle lenses.

Yet the deep focus in the first image was accomplished by means of a back-projected film showing the boy Kane in the window, while the second image is a multiple exposure. The glass and medicine bottle were shot separately against a black background, then the film was wound back and the action in the middle ground and background were shot. (And even the middle-ground material, Susan in bed, is notably out of focus.) I suspect that the flashy deep-focus illustration in Life, shot with a still camera, is a multiple exposure too. In any event, much of the depth of field on display in Kane couldn’t have been achieved by straight photography. (13)

RKO’s special-effects department had years of experience with back projection and optical printing, notably in the handling of the leopard in Bringing Up Baby, so many of Kane‘s boldest depth shots were assigned to them. But here is all that Toland has to say on the subject:

RKO special-effects expert Vernon Walker, ASC, and his staff handled their part of the production—a by no means inconsiderable assignment—with ability and fine understanding. (14)

Kane’s reliance on rephotography deals a blow to Bazin’s commitment to film as a medium committed to recording an event in front the camera. Instead, the film becomes an ancestor of the sort of extreme artificiality we now associate with computer-generated imagery.

Despite these difficulties, Toland’s ideas sensitized filmmakers and critics to deep space as an expressive cinematic device. Modified forms of the deep-focus style became a major creative tradition in black-and-white cinema, lasting well into the 1960s. Bazin’s analysis certainly developed Toland’s ideas in original directions, and he creatively assimilated what Toland and his directors said into an illuminating general account of the history of film style. None of these creators and critics were probably aware of the remarkable depth apparent in pre-1920 cinema, or in Japanese and Soviet film of the 1930s. Their claims taught us to notice depth, even though we could then go on to discover examples that undercut Toland’s claims to originality.

Some little things to grasp at

I assume that Toland and his directors were sincerely trying to experiment, however much they may have packaged their efforts to appeal to viewers’ and critics’ tastes. But sometimes artists aren’t so sincere. By the 1950s, we have directors who started out as film critics, and they realized that they could guide the agenda. Here is Claude Chabrol:

I need a degree of critical support for my films to succeed: without that they can fall flat on their faces. So, what do you have to do? You have to help the critics over their notices, right? So, I give them a hand. “Try with Eliot and see if you find me there.” Or “How do you fancy Racine?” I give them some little things to grasp at. In Le Boucher I stuck Balzac there in the middle, and they threw themselves on it like poverty upon the world. It’s not good to leave them staring at a blank sheet of paper, no knowing how to begin. . . . “This film is definitely Balzacian,” and there you are; after that they can go on to say whatever they want. (15)

Chabrol is unusually cynical, but surely some filmmakers are strategic in this way. I’d guess that a good number of independent directors pick up on currents in the culture and more or less self-consciously link those to their film.

Today, in press junkets directors can feed the same talking points to reporters over and over again. An example I discuss in the forthcoming Poetics of Cinema is the way that Chaos theory has been invoked to give weight to films centering on networks and fortuitous connections. As I read interview after interview, I thought I’d scream if I encountered one more reference to a butterfly flapping its wings.

More recently, Paul Greengrass gave critics some help when he suggested that the jumpy cutting and spasmodic handheld camera of The Bourne Ultimatum suggested the protagonist’s subjective point of view–presumably, Jason’s psychological disorientation and frantic scanning of his surroundings. I expressed skepticism about this on an earlier blog entry, Anne Thompson replied on her blog, and I returned to the subject again. Any director’s statement of purpose is interesting in itself, but it should be assessed in relation to the evidence we detect onscreen.

Another recent instance: the new Taschen book on Michael Mann. The luscious pictures, mainly from Mann’s archive, are the volume’s raison d’etre, but the filmmaker seems to have placed unusual demands on the text. F. X. Feeney writes:

An earlier version of this book completed by another writer attempted (in a spirit of sincere praise) to treat Mann’s films as reactions against film traditions, as subversions of genre. This fetched a rebuke from Mann: “It’s irrelevant and neither accurate nor authentic to compare my films to other films because they don’t proceed from genre conventions and then deviate from those conventions. They proceed from life. For better or worse, what I’ve seen and heard and learned on my own is the origin of this material. Maybe the film medium by nature spawns conventions, because we all built on what’s gone before, but the content and themes of my films are not facile and derivative. They are drawn from life experience.” (16)

We have to wonder if Mann’s objection played a role in eliminating the earlier writer’s version. If that happened, it’s an unusually strong instance of a director’s holding sway over critical commentary. (17)

In the text we have, Feeney provides a chronological account of Mann’s career: plot synopses, thematic commentary, production background. There’s no discussion of broader historical trends, such as the migration of TV directors into film, the creative options available in 1980s-1990s Hollywood, the development of self-conscious pictorialism in modern film, the possibility of genre films becoming art-films or prestige pictures, or the changes in media culture or American society. All of these lines of inquiry would require comparing Mann with other filmmakers. It remains for other writers, perhaps without the director’s cooperation, to put Mann’s achievement into such contexts.

It’s always vital to listen to filmmakers, but we shouldn’t limit our analysis to what they highlight. We can detect things that they didn’t deliberately put into their films, and we can sometimes find traces of things they don’t know they know. For example, virtually no director has explained in detail his or her preferred mechanics for staging a scene, indicating choices about blocking, entrances and exits, actors’ business, and the like. Such craft skills are presumably so intuitive that they aren’t easy to spell out. Often we must reconstruct the director’s intuitive purposes from the regularities of what we find onscreen. (For examples, see this site here, here, and here.) And it doesn’t hurt, especially in this age of hype, to be a little skeptical and pursue what we think is interesting, whether or not a director has flagged it as worth noticing.

(1) Macdonald, “Gertrud,” Esquire (December 1965), 86.

(2) Quoted in Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, ed. Jonathan Rosenbaum, This is Orson Welles (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 21).

(3) Such would seem to be the case of the close-up, which of course is found very early in film history. But Griffith’s idea of a close-up may not correspond to ours. More on this in a later blog, perhaps.

(4) I give an overview of this rich body of research in Chapter 5 of On the History of Film Style. See also various entries in the Encyclopedia of Early Cinema, ed. Richard Abel (New York: Routledge, 2005).

(5) The most detailed argument for this view I know is Paisley Livingston’s book Art and Intention: A Philosophical Study.

(6) “William Wyler, or the Jansenist of Directing,” in Bazin at Work: Major Essays and Reviews from the Forties and Fifties, ed. Bert Cardullo (New York: Routledge, 1997), 8.

(7) Orson Welles: A Critical View, trans. Jonathan Rosenbaum (New York: Harper and Row, 1978) 80).

(8) Toland, “Realism for Citizen Kane,” American Cinematographer 22, 2 (February 1941), 54, 80.

(9) See the discussion in Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), 345-349.

(10) Toland, “How I Broke the Rules in Citizen Kane,” Popular Photography (June 1941), 55, 90-91.

(11) “Orson Welles: Once a Child Prodigy, He Has Never Quite Grown Up,” Life (May 26, 1941), 110-111.

(12) Wyler, “No Magic Wand,” The Screen Writer (February 1947), 10.

(13) Peter Bogdanovich was to my knowledge the first person to publish some of this information; see “The Kane Mutiny,” Esquire 77, 4 (October 1972), 99-105, 180-90.

(14) Toland, “Realism,” 80.

(15) “Chabrol Talks to Rui Noguera and Nicoletta Zalaffi,” Sight and Sound 40, 1 (Winter 1970-1971), 6.

(16) F. X. Feeney, Michael Mann (Cologne: Taschen, 2006), 21.

(17) Mann’s reasoning puzzles me. He insists that his films can’t be compared to others along any dimensions, especially thematic ones. Yet in saying that his films are lifelike, he suggests that other films aren’t as realistic as his. Moreover, what about comparisons on grounds of technique, surely one of the most striking and admired features of Mann’s work? For reasons that are obscure, the director discourages any critical consideration of style; Feeney tells us that Mann hates the very word (p. 20).

Ad in Wid’s Year Book 1918.

PS: 15 October: I’ve received a clarification from Paul Duncan, editor of F. X. Feeney’s Michael Mann book for Taschen. He expresses general agreement with my suggestions about how directors shape the uptake of their work, but he explains that the Mann book isn’t an instance of it. Here are the comments bearing on my blog entry.

In reply to my suggestion of other avenues to explore about Mann’s career:

In fairness to F.X. Feeney, he only had 25,000 words to cover Mann’s career, and all the subjects you write about are really outside the scope of the book. It sounds as though these are subjects that you would like to explore, and I can’t wait to read them in a future book or blog.

As for whether Mann exercised some control over the book’s final form, which I float as one possible explanation for its compass:

First, you speculate whether Mann caused the first version of the book to be scrapped, i.e. He exerted editorial control/censorship over the book. This is not the case, and if it was, do you think that he would have allowed F.X. to write that in the published version of the book?

In Note 17 appended to Feeney’s quote, you write: “Yet in saying that his films are lifelike, he suggests that other films aren’t as realistic as his.” If you had continued Mann’s quote, you would have reported the following: “I don’t look at the excellent French director Jean-Pierre Melville to decide how to tell the story in Thief. I meet thieves. And I guarantee you the reason Melville’s Le Samourai 1967) has authenticity, the reason Raoul Walsh’s White Heat (1949) has authenticity, is because those film-makers knew thieves, too.” I do not see any evidence here that Mann suggests that his films are more lifelike than other directors’. Only that his films stem from life like other films stem from life.

Also, in Note 17, you write: “For reasons that are obscure, the director discourages any critical consideration of style; Feeney tells us that Mann hates the very word (p. 20).” The reason Mann hates the word “style”—and I apologize for not making this clear in the book—is because after producing the Miami Vice TV show, he was forever referred to as a stylist, and the “style” of the show was all anybody ever talked about. The implication was that Mann is a director of style without substance. Subsequently, Mann has been very wary of the word, and discussion of it, because it puts undue weight on one aspect of his work.

Finally, I would like to explain a little of the working method with Mann on the book. The book was researched and written during rehearsal, filming and editing of Collateral. F.X. wrote the text and was given full access to everything that Mann had said in interviews. Mann then read and annotated the text, and this was discussed face-to-face with F.X. Most of these annotations were of a factual nature, correcting dates, being precise about the sequence of events, and to correct misinterpretations of his comments in previous interviews. However, they would also bring up new comments from Mann about his work. F.X. then rewrote some texts to include Mann’s comments, and then F.X. wrote his replies. In this way, the book became more of a dialogue between Mann and F.X. and is stronger for it I feel. So, in this case, the filmmaker did not get the last word.

I thank Paul for his clarifications, which should be of interest to all the book’s readers. On only two matters do we disagree.

First, Feeney’s book achieves what it set out to achieve, and it deserves credit for giving us valuable information about Mann in a clear, pungent style. And no one expects a Taschen book to be an in-depth monograph covering all aspects of a director’s career. But I still think that length limits don’t prevent an author from raising the contextual issues I mention. Many articles manage to address matters that go beyond the sort of career survey that Feeney provides, so there are ways to sketch such issues in an abbreviated way. I inferred, erroneously, that the choice not to tackle them could have been related to Mann’s own views on the comparative dimension that such issues tend to rely on.

Secondly, a minor matter: The fact that Mann can invoke Melville and Walsh on films about thieves suggests that a comparative perspective is valuable; he’s including himself in the company of directors who know their subjects from life, in explicit contrast to those who don’t. I didn’t include the extra sentences because I thought that they simply provided further signs of the contradiction I found in Mann’s own position—that his films can’t be compared to other directors’ works.

Asian media empires, and the greatest of all filmmakers

DB here:

I owe you a final report on my viewings in Vancouver, but while I’m preparing that, I want to signal three publications, two printed books and one online book.

America seems to have cornered the market in branded entertainment. Movies and comics have given us Mickey Mouse, Shrek, Barney the dinosaur, Batman, Jughead, and all those other lovable characters you can’t escape. Once in a while another country gets into the game, as with Tintin (Belgium), the Smurfs (Belgium), and the Teletubbies (Britain). But for sheer numbers, the US’s only real rival, it seems, is Japan.

The cliché is that the Japanese make the hardware and we make the software. But Astro Boy (originally Mighty Atom), Speed Racer, Mighty Morphin Power Rangers, Sailor Moon, Pokémon, Cutie Honey, and Super Mario Brothers beg to differ. And if Zatoichi and Godzilla add their weight to the argument, you’ll back off fast. The Japanese have given the world an unending spate of sagas and characters, often of marked peculiarity. Ranma ½ changes from a boy to a girl and back again, and Mothra, even just being himself, is fairly creepy.

All of which makes Ken Belson and Brian Bremner’s Hello Kitty: The Remarkable Story of Sanrio and the Billion Dollar Feline Phenomenon (Wiley) an informative study and a breezy read. The pudgy cat with no mouth generates about $500 million in annual sales, half of Sanrio’s total, and she adorns over 20,000 products, including vibrators.

All of which makes Ken Belson and Brian Bremner’s Hello Kitty: The Remarkable Story of Sanrio and the Billion Dollar Feline Phenomenon (Wiley) an informative study and a breezy read. The pudgy cat with no mouth generates about $500 million in annual sales, half of Sanrio’s total, and she adorns over 20,000 products, including vibrators.

Belson and Bremner trace Ms. Kitty’s rise from humble beginnings in 1974 to her current status as a media superstar. Just as important, they put her in several intriguing contexts. They trace the rise of the kawaii (cuteness) sensibility throughout Asia, where Peanuts‘ Snoopy became the model. They show that Miss Kitty is emblematic of Japan’s shift from “hard” manufacturing industries to “soft” culture-based ones like comics and videogames. Some consumers, though, choke on all this sugar, and the authors haven’t omitted mention of those media jammers who want to turn our heroine into a hellcat.

The book is especially good at characterizing the distinctive Japanese belief that a product must arouse an emotional attachment in the consumer. Sony does it through sleek design, Tamagotchi the digital pet did it through guilt-tripping. Ms. Kitty might seem the epitome of blandness, her awww quotient and neoteny-driven features rendering her vacuous. Yet the lady has a touch of mystery. You’ve seen a smile without a cat, but here is a cat without a smile. Snoopy shamelessly exposes his fantasy life, but who knows what she’s feeling? Lust? Caution? Is she quietly judging us? Fill in the blank.

For a more comprehensive analysis of how Asian media empires work, go to Michael Curtin’s brand-new Playing to the World’s Biggest Audience: The Globalization of Chinese Film and TV (University of California Press). Michael is a close friend and colleague, so in principle I’m biased; but I’d think this a terrific book if he were a stranger. Among many other things, it shows that media globalization isn’t a one-way flow, from Hollywood to ROTW (Rest of the World). Asian media are globalizing too, and the process is both fascinating and far-reaching.

For a more comprehensive analysis of how Asian media empires work, go to Michael Curtin’s brand-new Playing to the World’s Biggest Audience: The Globalization of Chinese Film and TV (University of California Press). Michael is a close friend and colleague, so in principle I’m biased; but I’d think this a terrific book if he were a stranger. Among many other things, it shows that media globalization isn’t a one-way flow, from Hollywood to ROTW (Rest of the World). Asian media are globalizing too, and the process is both fascinating and far-reaching.

The book provides both history and contemporary analysis. Michael shows that Shaw Bros. pioneered the concept of an entertainment conglomerate in Asia, and he traces their policies across several decades. The story starts in Hong Kong, with its curiously transnational film industry, but the tale sweeps across media (TV, telephony, internets) and territories: Taiwan, Singapore, and mainland China. Michael has interviewed many major players, so if you want to know what’s really behind Golden Harvest, Media Asia, China Star, Star TV, Celestial, and other companies, this is the place to go. In the area I know a little, Michael offers the shrewdest and strongest analysis of the rise and precipitous fall of the Hong Kong film industry I’ve seen.

Playing to the World’s Biggest Audience will attract scholars and business people wanting to understand the dynamics of Asian media. I think as well that fans of Asian film, music, and TV can get a lot out of it. If you’re put off by the first chapter’s theoretical layout, skip to chapter two and jump into the compelling story of how entrepreneurs from southern China assembled a media juggernaut that now enthralls over a billion spectators.

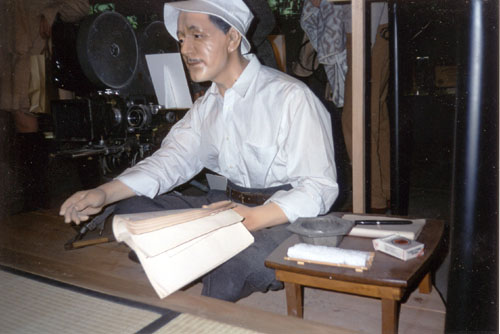

Finally, about a year ago on this blog I wrote an entry about the online arrival of my Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, thanks to the publishing initiative of the Center for Japanese Studies at the University of Michigan. Now an improved online edition of this scarce out-of-print book has just gone online. You can download the whole shebang if you want.

Finally, about a year ago on this blog I wrote an entry about the online arrival of my Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, thanks to the publishing initiative of the Center for Japanese Studies at the University of Michigan. Now an improved online edition of this scarce out-of-print book has just gone online. You can download the whole shebang if you want.

In the first version, posted a year ago, the pictures were hard to see, so we made digital versions of all the original stills. The monochrome ones look very nice, and the color ones (not an option for the print edition) look fine. In addition, if you click on a still in the sidebar, you can enlarge it and even download it. Thanks to web tsarina Meg Hamel, we have a permanent link in the list of books on the left.

There’s also a new introduction, in which I explain a bit about the background of the book, talk about the approach it takes, position it within trends of film studies, and suggest what Ozu means to me. My introduction also shows some rare pictures, including snaps from a strange exhibition about Ozu’s life. The exhibition has vanished now, but maybe that’s an appropriate tribute to an artist who made mutability everlastingly vivid.

A toast to Markus Nornes, Bruce Willoughby, Kristi Gehring, Terry Geitgey, and all the other people who took pains to make this improved online Ozu possible.