Archive for the 'Books' Category

Is there a blog in this class?

First edition, Addison-Wesley, 1979

Kristin here–

As our blog’s name suggests, we started it partly so we could write about subjects that would be of interest to lovers of cinema. It’s also a resource upon which teachers, students, and general readers using our textbook, Film Art: An Introduction, can draw. For that matter, many entries contain material that is pertinent to Film History: An Introduction as well. The entries are written in a more informal fashion than are the textbooks, but they often extend or elaborate points made in the books.

Now that universities here in the U.S. and in many other countries are beginning their autumn semesters, it seemed a good time for us to suggest some possibilities for using specific blog entries to cast light on topics in our text.

Second edition, Random House, 1986

First, there are some general entries that might aid the teacher as courses begin. For those who show excerpts from DVDs in classes and are nervous about copyright issues, my piece, “Film educators no longer criminals” will be reassuring. It explains how last year fair-use exemptions covering just that situation were put into effect last year. Create that Powerpoint lecture or bring a DVD into class to analyze with impunity.

First, there are some general entries that might aid the teacher as courses begin. For those who show excerpts from DVDs in classes and are nervous about copyright issues, my piece, “Film educators no longer criminals” will be reassuring. It explains how last year fair-use exemptions covering just that situation were put into effect last year. Create that Powerpoint lecture or bring a DVD into class to analyze with impunity.

Teachers often confront the problem of overcoming students’ resistance to subtitled, black-and-white, and/or silent films. My entry “Subtitles 101” might be of some help in persuading them to be more open to viewing unfamiliar kinds of films. David’s “From Hollywood to Atlanta to us,” on the huge variety of films to be found on Turner Classic Movies, suggests the delights of having access to such a wide range of cinema history. (Also check out Jim Emerson’s recent “Gimme them old-time furrin pictures” on his Scanners blog.)

For students who don’t see a difference between watching films on an iPod and a cinema screen, David ruminates on some of the advantages and disadvantages of the tiny digital image in “Area man lives in fear that attractive woman will ask what’s on his iPod.” Similarly, for those who confidently expect to be able to find anything they need for viewing or researching term papers online, my “The Celestial Multiplex” might prove an eye-opener.

Third edition, McGraw-Hill, 1990

Chapter 1 begins by briefly introducing film as an art form. David’s entry, “But what kind of art?” could be used to fill out that section, though it is most appropriate for film majors and advanced classes.

Chapter 1 begins by briefly introducing film as an art form. David’s entry, “But what kind of art?” could be used to fill out that section, though it is most appropriate for film majors and advanced classes.

The chapter also differentiated between studio and independent filmmaking. David’s “Independent film: how different?” is relevant here. For a discussion of the auteur theory as contested by one prominent Hollywood writer, Joe Eszterhas, see David’s “Who the devil wrote it? (apologies to Peter Bogdanovich).”

These days news sources cover the weekend box-office figures and rank the highest grossing films. The raw figures don’t tell the whole story, though, since they don’t specify how many theaters each title is showing in or how big each film’s production budget was. A film playing in only a few theaters might be low on a list, but if it is making thousands of dollars more per theater, it might ultimately be more successful. A low-budget film doesn’t need to gross as much to become profitable as a costly epic does. My “What won the weekend, or, How to understand box-office figures” adds some nuances to the simple lists reporters give us each Monday.

Chapter 2 includes a section on “Formal Expectations.” One of the effects of creating expectations can be suspense. In “This is your brain on movies, maybe,” David explores why viewers enjoy watching films where they know the outcome, either through having seen the film before or because the story is based on real events—in this case United 93.

Chapter 3 is devoted to cinematic storytelling. A sample analysis of narrative organization can be found outside the blog, in David’s online essay on Mission: Impossible III. On our very first blog entry, back in September 2006, we quoted the director of One Hour Photo explaining how he rethought the film’s original plot structure so as to maximize curiosity. In the same chapter, we include “Openings, Closings, and Patterns of Development” as one of the principles of narrative construction. David’s blog entry “First shots” discusses some of the ways filmmakers have historically used first shots to plant narrative information, introduce motifs, establish tone, and, in recent decades, to lead off with a dense, virtuoso moment to be savored as such.

Fourth edition, McGraw-Hill, 1993

Recent years have seen sequels, prequels, series, and other forms of extended narratives being used more pervasively in Hollywood cinema. My “Originality and origin stories” discusses the phenomenon of the film that jumps back to an early stage in the life of a character in a previous film. David explores two other current trends, toward narratives involving networks of criss-crossing characters and those that play self-consciously with plot, in “An appetite for artifice.”

Recent years have seen sequels, prequels, series, and other forms of extended narratives being used more pervasively in Hollywood cinema. My “Originality and origin stories” discusses the phenomenon of the film that jumps back to an early stage in the life of a character in a previous film. David explores two other current trends, toward narratives involving networks of criss-crossing characters and those that play self-consciously with plot, in “An appetite for artifice.”

Does the increasing consumption of films on DVDs rather than in theaters change the way we watch and understand narratives? Does the remote control encourage us to manipulate what we’re seeing in ways unexpected by the filmmakers? David tackles that question in “New media and old storytelling.”

One of the most popular topics covered in Chapter 4, on Mise en scene, is acting. In “Good actors spell good acting,” I consider how a focus on an impressive performance can sometimes lead a critic to downplay other aspect of a films. An older tradition of ensemble performance in relation to camera position gets some analysis in “Watching movies very, very slowly.”

David’s fascination with modern styles of cinematography (Chapter 5) and editing (Chapter 6) is evident in several entries, most illustrated with many frame enlargements. In “Can they make ‘em like they used to? continued,” he deals with foreground objects and depth of focus. His essay on “Shot-consciousness” examines a specific type of framing that places the characters against a flat background and frontally facing the camera—a technique he terms “planimetric framing.”

In another entry on cinematography, “Funny framings,” David explores how the manner in which the camera frames its subject can create humor. This has been one of our most popular entries, as is evidenced by the number of people who wrote to David with their favorite examples. In “Walk the talk,” David discusses the specific sort of tracking shot that follows characters talking with each other.

Occasionally our blog gets caught up in a topic that has generated controversy among critics. One of these is the use of fast cutting and abnormally fast, out-of-focus camera movements in The Bourne Ultimatum. Nausea-inducing excess or deliberately disorienting style? In two entries, David argues that the hyperactive camera is largely unmotivated and distracting: “Unsteadicam chronicles” and “[insert your favorite Bourne pun here].”

One of our first entries to gain widespread attention was David’s discussion of story structure and editing in “The Departed: no departure.” He discussed the increasing rapidity of Scorsese’s cutting and linked it to a broader trend of intensified continuity in American cinema. That trend is explained further in “Intensified continuity revisited.” In the case of The Good German, a film that claimed to mimic classical Hollywood films of the 1940s and 1950s, David discussed the concept of “coverage” in traditional filming. See his “Cutting remarks on THE GOOD GERMAN, classical style, and the Police Tactical Unit.”

Fifth edition, McGraw-Hill, 1997

In teaching non-classical approaches to film editing, David’s “Another pebble in your shoe” might be useful. There David discusses how Lars von Trier used multiple cameras to film scenes and a computer to dictate seemingly random cutting in The Boss of It All.

In teaching non-classical approaches to film editing, David’s “Another pebble in your shoe” might be useful. There David discusses how Lars von Trier used multiple cameras to film scenes and a computer to dictate seemingly random cutting in The Boss of It All.

Chapter 6 includes a section on “Rhythmic Relations Between Shot A and Shot B.” There we discuss the number of frames in each shot as a measure of screen duration. David talks about counting frames in film vs. various video formats in “My name is David and I’m a frame-counter.”

In our extended analysis of continuity editing in the opening scene of The Maltese Falcon, we discuss the technique of shot/reverse shot—the basic editing pattern used in conversation scenes in classical films. “Angles and perceptions” discusses this technique and what happens when a scene holds on a shot of one speaker without cutting to the reverse shot. Late in “Walk the Talk,” there’s an analysis of how continuity editing can be coordinated with staging and framing.

When watching a film, we seldom perceive the sound tracks as a blend of many separate recordings. It comes across as a seamless sonic accompaniment to the images. David had the opportunity to sit in on a sound-mixing session for the new film 3:10 to Yuma, directed by James Mangold. He describes that experience in “Christian Bale picks up a rail.” (This could provide an additional example for the section of Chapter 7 entitled, “Selection, Alteration, and Combination,” pp. 268-272.)

In Chapter 8 of Film Art we use Citizen Kane as our summary instance of film style. Some blog entries that deal with style in specific films include: “TANGO marathon” (on Béla Tarr’s epic Sátántangó); “Not back to the future, but ahead to the past” (on Steven Soderbergh’s attempt to mimic 1940s Hollywood style in The Good German); and “Classical cinema lives! New evidence for old norms” (on computer-generated special effects and their narrative functions).

Sixth edition, McGraw-Hill, 2001

In Chapter 9, we deal with film genres. In “Swords vs. lightsabers,” I talk about the cyclical nature of genres, suggesting that science-fiction films are waning in popularity just as fantasy films are becoming popular.

In Chapter 9, we deal with film genres. In “Swords vs. lightsabers,” I talk about the cyclical nature of genres, suggesting that science-fiction films are waning in popularity just as fantasy films are becoming popular.

Chapter 10 examines documentary, experimental, and animated films. Pixar is currently at the forefront of Hollywood animation. I’ve written on Cars in “Reflections on cars,” and David and I have a dialogue on Ratatouille in “Rat rapture.” In “By Annie standards,” I discuss why recent animated films are often better than live-action ones. David offers an appreciation of Disney’s classic features in “Uncle Walt the artist.”

We dicuss experimental filmmakers in “Lewis Klahr, X 3, X 4” (David), “3 notions about CREMASTER 2” (David on Matthew Barney’s cycle of films), and “Len Lye, renaissance Kiwi” (me on New Zealand’s great creator of experimental animation).

Chapter 11 ends with a section on “Writing a Critical Analysis of a Film.” David’s entry, “Watching movies very, very slowly,” gives a vivid demonstration of how we go about the research that goes into a detailed film analysis.

Some of our blog entries could be read in relation to more than one chapter. David’s “Charlie, meet Kentaro,” on the Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto B-film series, deals with film history, style, and ideology.

Seventh edition, McGraw-Hill, 2004

For musings on the relationship of early cinema to Victorian painting, see David’s “Professor sees more parallels between things, other things.”

For musings on the relationship of early cinema to Victorian painting, see David’s “Professor sees more parallels between things, other things.”

David’s book, Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, is now available online. For details, see his “I wrote a book, but …; or, what did the professor forget?”

Some teachers dealing with the classical Hollywood cinema of the 1930s to 1950s may wish to cover the B movie. Grad students and alumni of the University of Wisconsin film-studies program contribute to a dialogue on the subject in “Bs in their bonnets: A three-day conversation well worth the reading.”

We deal with the important institution of film festivals. I review a book on one of the most important of these festivals in “Cannes: Beyond the art, hype, and politics.”

When the second edition of Film History came out, two of the auteurs whose careers we examine in Chapter 19 were still alive. Now Ingmar Bergman and Michelangelo Antonioni have both died, and on the same day. David’s “Bergman, Antonioni, and the stubborn style” could make a coda for our chapter sections on those directors.

For updated information on Asian cinema, check the tags on the right. For recent Danish cinema, see David’s, “My Danish December.”

At intervals we report from film festivals we attend. So far such reports have come from the 2006 Vancouver Film Festival, the 2007 Hong Kong Film Festival, Roger Ebert’s Overlooked Film Festival (aka “Ebertfest,” 2007), and Il Cinema Ritrovato (“Rediscovered cinema,” in Bologna, Italy, 2007). These reports deal with the people we meet there, the films we see, and the institutions that run the festivals. We’ll continue to write such dispatches during our travels. Most of these reports have multiple parts, so be sure to follow the links.

As I said at the outset, our blog can serve as a supplement to our textbooks. We usually don’t, however, write new entries with that in mind. As we see recent films, revisit old ones, read books, and see information posted on the internet, we find inspiration to engage with the cinema in fresh ways. We find ourselves making contact with people we had never met and reconnecting with colleagues we have not heard from in decades. We hope that we are learning as we go along and passing along some of that learning to readers of Film Art and Film History.

Note: Elsewhere on this website there is a section on Film Art. Here you can find a list of corrections for errata in the 8th edition. We also include all of the sample analyses that have been cut from various editions: The Man Who Knew Too Much, Stagecoach, Hannah and Her Sisters, Desperately Seeking Susan, Day of Wrath, Last Year at Marienbad, Innocence Unprotected, Clock Clearners, Tout va bien, High School.

[November 15, 2009: See also the 2008 and 2009 updates on more recent blog entries.]

Eighth edition, McGraw-Hill, 2008

Updates: Len Lye, Frodo Franchise, blockbusters, and news from/about Hong Kong

Kristin here—

More on Len Lye

After my recent post on Len Lye, I heard from both Roger Horrocks, Lye’s biographer, and Tyler Cann, Curator of the Len Lye Collecton of the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in New Plymouth, New Zealand. (Neither with corrections, I am happy to say!) They have filled me in on some activities that should make Lye’s film work more accessible.

First, a DVD of Lye’s films is being prepared. Unfortunately factors like the process of assembling the best surviving prints means that the finished product will not be available in the near future.

Second, the near future will bring a touring program of Lye’s films to North America. Called “Free Radical: The Films of Len Lye,” it has been organized by The New Zealand Film Archive, the Len Lye Foundation, and Anthology Film Archives. (The name was inspired by Lye’s scratched-on-film animated short, Free Radicals, 1958.) Here are the venues and dates:

Oct 12 Anthology Film Archives, New York

Oct 12 Anthology Film Archives, New York

Oct 18 NASCAD (Nova Scotia College of Art and Design) Halifax, Nova Scotia

Oct 23 Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley

Oct. 28 Film Forum, Los Angeles

Oct 30th CALARTS, Los Angeles

Nov 2nd University of Notre Dame, Indiana

Nov. 7th George Eastman House, Rochester

Nov. 26th Harvard Film Archive, Cambridge

Dec 8th Chicago Filmmakers, Chicago

Dec. 15th International House, Philadelphia

Roger tells me that he intends to write a book on Lye’s theory and practice of what he called “the art of motion.” This reminds me that I forgot to mention that there is a collection of Lye’s writings, Figures of Motion: Len Lye Selected Writings, co-published in 1984 by Auckland University Press and Oxford University Press. It was co-edited by Roger and Wystan Curnow and is, alas, long out of print. Another thing to look for in your local library.

The Frodo Franchise

I am happy to report that The Frodo Franchise is now in the process of being rolled out. The University of California Press has been shipping copies for weeks, and it should soon appear on bookstore shelves—and may have already in some places. The copy we pre-ordered from Amazon back in April arrived on July 30.

I have bowed to the inevitable and am in the process of constructing a separate website, “Frodo Franchise,” to deal with matters relating to the book and the films. (That is, Meg, our web czarina, is constructing it.) I don’t want information about the book, comments on the Hobbit film situation, and similar items to overbalance our blog, which they threaten to do. I’ll post a notice when the site is up and running.

In the meantime, Pieter Collins of the Tolkien Library, an excellent reference and news site dedicated to the novels, has interviewed me about my book. You can read the result here. Henry Jenkins has done the same, through his site, Confessions of an Aca-Fan, is more oriented toward popular media and fandom. The interview is in three parts here, here, and here.

Hollywood Blockbusters Doing Pretty Well

On February 28 I posted an entry, “World rejects Hollywood blockbusters?” There I argued against claims in an article by Nathan Gardels, editor of NPQ and Global Viewpoint, and Michael Medavoy, CEO of Phoenix Pictures and producer of, among many others, Miss Potter. They claimed that there were many signs that Hollywood’s big-budget films are being rejected at the box office: “Audience trends for American blockbusters are beginning to show a decline as well, both at home and abroad.”

Since then, of course, Hollywood blockbusters have been cleaning up at home and abroad. We’re all familiar by now with the series of huge international openings, with many blockbusters being released day and date in most major markets. As one example, take Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, which so far has grossed $774,070,000 worldwide. The US and Canada claimed only about one-third ($264 million) of that total (Box Office Mojo, August 4). Overseas, Phoenix has scored $510 million, for 65.9% of its global haul. The Three Threes, Shrek, Pirates, and Spider-man, all cleaned up internationally, as did Transformers. (The fourth Three film, The Bourne Ultimatum, looks set to do the same.) The Simpsons Movie has recently begun its climb to box-office glory.

Leonard Klady, an excellent writer on the international film industry, summed up the situation for 2007 in the 22 June print edition of Screen International: “Worldwide predictions that 2007 would break recent box-office records look to be well founded. The international box office generated $4.5bn in the first four months of 2007. Combined with revenues from the domestic North American marketplace, the global gross for the period was $7.2bn. International theatrical [i.e., markets outside the U.S. and Canada] accounted for 61.6% of the worldwide box office on gross figures that exceeded domestic ticket sales by 60.6%. Based on current viewing trends, global box office could finish the year at a record-breaking $24.6bn.”

Klady points out that much of the rise comes from the factor I discussed in my earlier entry: the expansion of the international market. According to him, “The international market has become increasingly significant in the past decade.” A decade ago, foreign income averaged 45% of Hollywood films’ takings. By 2006 it was around two-thirds.

These facts also bear on Neil Gabler’s February article, “The movie magic is gone,” where he lamented the purported decline in theatrical films’ importance. That there was such a decline, he claimed, was evidenced by the fact that box-office revenues are down, both domestically and abroad. I refuted Gabler’s claims at some length in this March 11 post, and the successful summer that Hollywood is now enjoying adds further evidence to show that his argument was based on false assumptions.

DB here–

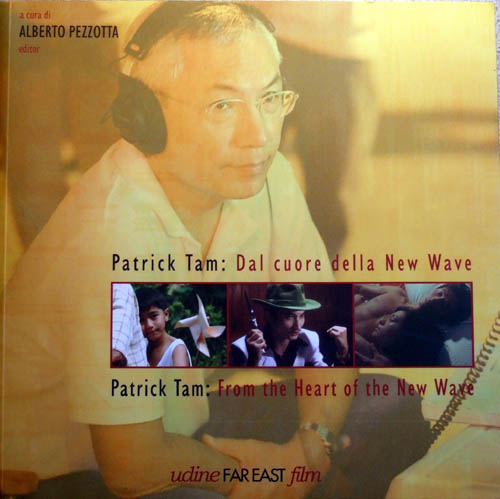

The Udine Far East Film Festival had a tremendous program this year, and just the YouTube promo made you want to book a ticket. But I couldn’t go! Still, the organizers kindly sent me their excellent catalogue Nickelodeon and the real topper, the festival’s thick volume dedicated to Patrick Tam Kar-ming. Editor Alberto Pezzotta, indefatigable researcher into Hong Kong film, organized a vast retrospective of Tam’s key New Wave films, such as Nomad and The Sword, as well as his less-known television work. The book includes critical essays, a detailed filmography, and a long, informative interview. Tam brought a cosmopolitan sensibility to Hong Kong film, thanks to his sensitivity to European directors like Godard and Antonioni. His latest film, the widely acclaimed After This, Our Exile, signals a new phase in his career.

When I was writing Planet Hong Kong between 1997 and 1999, I was often frustrated by a lack of solid information and in-depth critical writing. Tony Rayns’ superb essays and the annual catalogues published by the Hong Kong International Film Festival were about all I could rely on. That situation has improved in recent years, with many well-researched books on Hong Kong film appearing. Outstanding here is Stephen Teo, who has given us two books this year alone: King Hu’s A Touch of Zen and the just-out Director in Action: Johnnie To and the Hong Kong Action Film. This efflorescence of writing comes just when local cinema is in its deepest slump. You won’t find me quoting Hegel often, but in this instance it does seem that the owl of Minerva is flying at dusk.

When I was writing Planet Hong Kong between 1997 and 1999, I was often frustrated by a lack of solid information and in-depth critical writing. Tony Rayns’ superb essays and the annual catalogues published by the Hong Kong International Film Festival were about all I could rely on. That situation has improved in recent years, with many well-researched books on Hong Kong film appearing. Outstanding here is Stephen Teo, who has given us two books this year alone: King Hu’s A Touch of Zen and the just-out Director in Action: Johnnie To and the Hong Kong Action Film. This efflorescence of writing comes just when local cinema is in its deepest slump. You won’t find me quoting Hegel often, but in this instance it does seem that the owl of Minerva is flying at dusk.

Arrivederci Ritrovato

The three chiefs of Cinema Ritrovato: Peter von Bagh and Gianluca Farinelli strategize, while Guy Borlée does some heavy lifting.

Our last days at Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato were as busy as the first ones. Inevitably, choices, choices. Invasion of the Body Snatchers in a rare SuperScope print, or Asta Nielsen as Hamlet? Emilio Fernandez’s melodrama Enamorada (1946) or a 1907 version of Little Red Riding Hood, with a big dog playing the Wolf? You can’t see it all, but we offer some notes on some of the choices we made.

I can’t say that I am a great fan of Frank Borzage’s films of the 1930s and 1940s. For me his great period was the mid- to late 1920s. 7th Heaven (1927) somehow manages to climb beyond its blatant sentimentality, much as the hero and heroine ascend the stairs of their tenement apartment house, and earns our emotional investment in their transcendent love. For me, Lazybones (1925) and Lucky Star (1929) were the revelations of the Borzage retrospective during the 1992 Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone. It is a true pity that both remain largely unknown.

Borzage’s No Greater Glory (1934) was shown in a stunning print supplied by Sony Columbia. It didn’t fall into any of this year’s themes but was simply one of the “Ritrovati & Restaurati” items. The film deals with rival youth gangs in Budapest who organize themselves along strict military lines. Purportedly an anti-war tale, it manages to make the self-imposed discipline and even gallantry of the boys seem almost redemptive. I found the young hero, a scrawny but brave lad who struggles to be worthy of promotion within the ranks of his chosen gang, a bit too calculated to tug at the heartstrings. Still, it was entertaining, and the print showed it—and especially Joseph H. August’s cinematography—off to the best possible advantage. (KT)

While Kristin was watching Borzage, I decided to revisit Ilya Trauberg’s Goluboi Express (1929), one of the least known of the Soviet Montage films. Like Pudovkin’s Storm over Asia, it’s an attack on Western imperialism. Chinese, many sold into servitude, are packed into the rear cars of the train, while colonialists loll around up front. Two western soldiers of fortune attack a Chinese girl, and a young Chinese tries to defend her. This launches a prolonged battle and chase while the train roars on. By 1929, Trauberg had absorbed the lessons in cutting taught by Kuleshov, Eisenstein, and Pudovkin, and he adds his own imaginative touches. The taut construction and torrential editing (over 1400 shots in less than an hour) create an electrifying experience.

This particular version is an intriguing rarity. In his introduction, Bernard Eisenschitz explained that Soviet authorities persuaded Abel Gance to distribute the film in France. Gance recut it to avoid censorship, and he commissioned musical accompaniment by Edmund Meisel, the experimental composer who scored Battleship Potemkin. Meisel’s score amplifies and sharpens Trauberg’s hammering visuals. (DB)

The book room was running for only about half the festival, so I was glad I nabbed my consumer durables early. Many high points, including a fascinating DVD collection of Marey films, but the most memorable, if only because of the struggle to carry it back home, is This Film is Dangerous. Published by the International Federation of Film Archives, this colossal book appears to present everything you wanted to know about this incendiary filmstock. It includes discussions of how nitrate came to be an ingredient of film, how the nitrate preservation movement (“Nitrate won’t wait”) started, case histories of restorations, poems in praise of nitrate, a chronology of nitrate fires, and an anonymous contribution called “Nitrate Pussy.” In all, virtually a film geek’s bathroom book, although its bulk demands a large lap. It doesn’t yet seem to be available on the FIAF website, but it should be soon.

Speaking of swag and plunder, Dan Nissen of the Danish Film Institute kindly gave me a copy of their latest DVD publication, the first of several volumes devoted to Jørgen Leth. It’s a handsome production and sure to increase interest in the man behind The Perfect Human and the target of Lars von Trier’s painstaking abuse in The Five Obstructions. It’s available at the DFI website. (DB)

Although Michael Curtiz’s 1929 epic Noah’s Ark has been shown at various festivals in recent years, I somehow had always managed to miss it. Perhaps this was just as well, since the print shown in Bologna as part of the salute to Curtiz is longer than most and has the original sound restored from the Vitaphone records. (More often the film has been shown in its silent version.) Piecing together bits from several release prints held in different archives, something approximating the 1929 release version has been reassembled and matched to the sound. The credits in the program—“Print restored by YCM laboratories, funded by Turner Entertainment Company and AT&T in collaboration with La Cinémathèque Française and The Library of Congress”—hints at the complexity of the task.

Like The Jazz Singer and other early talkies, Noah’s Ark has long stretches of purely musical accompaniment. At intervals, though, characters suddenly start speaking, usually at the lugubrious pace typical of performances at the dawn of sound. The effect is startling, especially when the transition happens within a scene. Such switches proved jarring to the reviewers of the day, but the chance to see a film hovering between silent and sound can be fascinating to a modern viewer. The pacifist message of Noah’s Ark reflects a general anti-war sentiment in Hollywood films of the 1920s and 1930s—a healthy reminder of a day when the majority of good, patriotic Americans could take a dim view of warfare. The film’s ending, in fact, optimistically declares that the Great War had put an end to all wars. (KT)

Having written a book on Ernst Lubitsch’s silent features, Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood, I was particularly interested in a dossier on the director. It included a reconstruction of Die Flamme (1922), of which only one reel survives, using publicity photos, set designs, and descriptive intertitles. Though still short at only 44 minutes, this version gives a good sense of the plot, which was certainly not evident from the existing footage.

We have long known that Lubitsch’s intended first project in Hollywood was to be a version of Faust with Mary Pickford as Marguerite. That fell through, but it went far enough that screen tests were made. Twelve minutes of tests for a series of actors trying out for the part of Mephistopheles were shown. These were not exactly a revelation, but they do shed light on this transitional moment in the director’s career. (KT)

What do we do with a terrible movie by a sublime filmmaker? I’d argue that at least three directors achieved greatness in the years before 1920: D. W. Griffith, Louis Feuillade, and Victor Sjöström. Sjöström’s Ingeborg Holm (1913), Terje Vigen (1917), The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), The Outlaw and His Wife (1918), and Sons of Ingmar (1919) remain deeply moving and cinematically inventive. Sjöström moved smoothly from the fixed camera, long-take “tableau” style of the early 1910s to profound mastery of continuity editing on the US model only a few years later. He continued into the 1920s with such key American films as The Scarlet Letter (1926) and The Wind (1928).

So it’s saddening to report that A Lady to Love (1930) is a turkey. Edward G. Robinson, in full hambone overreach, plays an Italian-American grape farmer who seems to be flourishing despite the Volstead Act. Tony brings a down-at-heel waitress from the big city to be his wife, and she grows to love him, despite a little indiscretion involving Tony’s best friend. The sort of inert stage adaptation that gave talkies a bad name, A Lady to Love is solely for completists (of which Cinema Ritrovato boasts many). It was Sjöström’s last Hollywood picture. (DB)

The programs of 1907 films continued to yield treasures. Max Linder’s career got going that year, and he had not yet settled into the debonair, top-hatted persona that would within a few years become so familiar. In the simple and not terribly funny Débuts d’un patineur, he plays a novice ice-skater reduced to tears at by the film’s end, and in the more amusing Pitou bonne d’enfants Linder is a bumbling soldier who loses a baby confided to his care by his nursemaid sweetheart. The same program contained Louis Feuillade’s ever-popular Le Thé chez la concierge, where the guests start carousing so loudly that they drown out the bell rung by tenants trying to get into the house.

There were many early attempts to record synchronous sound, though all too often the accompanying discs have been lost even if the image track survives. The 1907 films contained a few such, but one, La Marseillaise, had its singer’s original voice, remarkably clear and perfectly synchronized. The result was an unusually poignant and vivid sense of a link to a hundred-year-old performance, an immediacy that went beyond what most silent films can convey, wonderful though they might be.

A familiar but welcome short was La course aux potirons (“The Pumpkin Chase”), one of the great entries in the very familiar genre of the day, the chase film. Special effects allow a wagon-load of pumpkins (looking like they were probably constructed from old tires) to bounce along city streets, up a chimney, and through windows, followed by the usual growing group of passersby. The inclusion of a donkey, duly hauled through the windows and up the chimney, makes the whole pursuit far funnier than in most such films.

Finally, the inclusion of a series of films about bomb-throwing anarchists, another common genre of the day, reminds us that the current international situation is not altogether a new one. (KT)

The DVD awards singled out efforts to making unusual cinema available in the DVD format. The top prize, Best DVD, was won by the Ernst Lubitsch collection, from Transitfilm and the Murnau Stiftung (available, with some variations, on Kino in the US). The committee commended it as “a model in the elegant packaging of rare materials in a form that is certain to attract new audiences.”

Anke Wilkening of the Murnau Stiftung accepts the award for best DVD.

Other awards: L’amore in città (Minerva, Italy), Best discovery; Seven Samurai (Criterion, US), Best Extras; the series on German cinema published by the Munich Film Archive, Best Series; and Akerman films of the 1970s (Carlotta, France), the French Naruse set (Wild Side) and the British Naruse set (Eureka), Best Box Sets.

Peter von Bagh commented that DVD producers are continuing the traditional work of film archives, and they often go beyond what archives can afford to tackle. Ironically, we sometimes find ourselves in the position of having excellent DVD versions of films that don’t exist in equally good prints. (DB)

Finally, some snapshots. Glancing around the book room, you’ll see Sawako Ogawa and Hiroshi Komatsu pouncing on items.

Not to be left behind, Janet Bergstrom and Richard Koszarski display Janet’s find.

Every year, Frank Kessler‘s birthday occurs during Ritrovato; this year was his fiftieth, and so Sabine Lenk made it a special treat.

At another meal, Danish film archivist Thomas Christensen, who really ought to know better, fends off the camera’s magical powers.

Same meal: shellfish and pasta sacrificed in a good cause.

Danish film historian Casper Tybjerg and Kristin sample gelato. Later I ate the one in the middle.

On the final evening, the film cans are wheeled out. Ci vediamo l’anno prossimo!

Simplicity, clarity, balance: A tribute to Rudolf Arnheim

DB here:

On Monday, at age 102, Rudolf Arnheim died. You can read his obituary here, and this is a lovely website devoted to his work. He was one of the most important theorists of the visual arts of the last century, and he had enormous impact on how people, including Kristin and me, think about film.

A good Gestalt

In parallel with E. H. Gombrich, who died in 2001, Arnheim brought modern psychological concepts into the study of visual art. His most famous work, Art and Visual Perception (1954, new version 1974) has the sort of magisterial presence that very few books in any era achieve. Arnheim delighted in the fact when, visiting a painter’s studio, he would find a spattered copy on the workbench. Of the revised edition, entirely rewritten, he noted:

All in all, I can only hope that the blue book with Arp’s black eye on the cover will continue to lie dog-eared, annotated, and stained with pigment and plaster on the tables and desks of those actively concerned with the theory and practice of the arts, and that even in its tidier garb it will continue to be admitted to the kind of shoptalk the visual arts need in order to do their silent work (new ed., x).

He aimed at theory that actively participates in the way artists do their job. The chapter titles of Art and Visual Perception deal with the nuts and bolts of picture-making: Balance, Shape, Form, Growth, Space, Light, Color, Movement, Dynamics, and Expression. No puns, slashes, dashes, or parentheses. What academic theorist today would so boldly announce their concern with the craft of creating images?

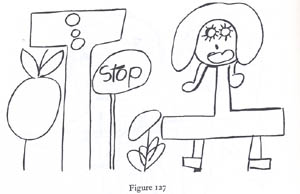

The book is subtitled, A Psychology of the Creative Eye, and the chapters’ subsection titles explain why. The hidden structure of a square . . . Vision as active exploration . . . Perceptual concepts . . . What good does overlapping do? . . . Why do children draw that way? . . . Gradients create depth . . . Visible motor forces . . . The priority of expression. Arnheim’s principal achievement in art theory was to integrate the Gestalt theory of perception with the traditional concerns of picture-making. He sought to show how perceptual laws discovered in the psychological laboratories of Berlin were intuitively applied by classic and modern artists.

As he put it, he was at the university at around age twenty:

My teachers Max Wertheimer and Wolfgang Köhler were laying the theoretical and practical foundations of gestalt theory at the Psychological Institute of the University of Berlin, and I found myself fastening on to what may be called a Kantian turn of the new doctrine, according to which even the most elementary processes of vision do not produce mechanical recordings of the outer world but organize the sensory raw material according to principles of simplicity, regularity, and balance, which govern the receptor mechanism.

This discovery of the gestalt school fitted the notion that the work of art, too, is not simply an imitation or selective duplication of reality but a translation of observed characteristics into the forms of a given medium (Film as Art, 3).

The Gestalters thought that these principles–figure/ground, completeness, good continuation, and the like–were fundamental to all human perception, across times and cultures. Art and Visual Perception makes a powerful case for this view. Today this position is so unfashionable that Arnheim’s calm confidence in it is quite stunning. For many scholars today, all that matters is what divides and differentiates us. But for eighty-plus years Arnheim emphasized ways in which we share a common experience of the world and of art.

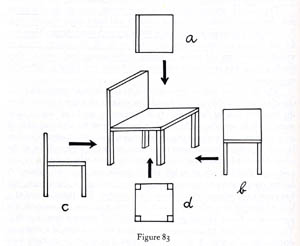

It’s often said that Arnheim favored modernist styles, like Cubism and expressionism, and that his emphasis on art as going beyond mere copying reflects modern artists’ will to distorted form. But he saw a deep continuity between classic art and modern art. Both traditions explored the perceptual force of form. Amazingly, he argues that the cockeyed creche in Fig. a conveys a stronger sense of three-dimensionality than the correct perspective presented in b. The “inverted” perspective encloses baby Jesus’ head fully, just a hollow cradle would.

It’s often said that Arnheim favored modernist styles, like Cubism and expressionism, and that his emphasis on art as going beyond mere copying reflects modern artists’ will to distorted form. But he saw a deep continuity between classic art and modern art. Both traditions explored the perceptual force of form. Amazingly, he argues that the cockeyed creche in Fig. a conveys a stronger sense of three-dimensionality than the correct perspective presented in b. The “inverted” perspective encloses baby Jesus’ head fully, just a hollow cradle would.

Arnheim saw the same form-giving activity at work in “primitive” art, the art of children, and even the art of the mentally ill. It turns out that the “universalism” of Gestalt theory underwrites diversity no less vigorously than the most ardent postmodernism.

Flexible striving

Arnheim made another contribution to our thinking about art, one that I think is rarely recognized. In a bold stroke, he extended the Gestalt conception of form beyond its concern with geometrical qualities and argued that form was inherently expressive. A triangle resting on its base wasn’t just balanced; it was weighty. We see the weeping willow as not just curved but sad; a skyscraper isn’t just tall, it’s aggressively thrusting upward. Every shape or movement we apprehend has a distinctive flavor and feeling. Indeed, he writes, “expression can be described as the primary content of vision”!

We have been trained to think of perception as the recording of shapes, distances, hues, motions. The awareness of these measurable characteristics is really a fairly late accomplishment of the human mind. Even in the Western man of the twentieth century it presupposes special conditions. It is the attitude of the scientist and the engineer or of the salesman who estimates the size of a customer’s waist, the shade of a lipstick, the weight of a suitcase. But if I sit in front of a fireplace and watch the flames, I do not normally register certain shades of red, various degrees of brightness, geometrically defined shapes moving at such and such a speed. I see the graceful play of aggressive tongues, flexible striving, lively color. The face of a person is more readily perceived and remembered as being alert, tense, concentrated rather than being triangularly shaped, having slanted eyebrows, straight lips, and so on (Art and Visual Perception, first ed., 430).

Arnheim found feeling in his forms.

Moving pictures

Arnheim wrote about many artforms, including mass media in his 1936 monograph on radio. His book on cinema, Film als Kunst (1932), was quickly translated into English as Film (1933). Always in search of greater clarity and point, Arnheim rewrote it in 1957. Oddly, he didn’t update it: You’ll search in vain for examples from the 1930s, 1940s, or 1950s. The touchstones remain Chaplin, Keaton, von Sternberg, and the Soviets. Arnheim held that cinema was essentially a pictorial art (see my earlier blog on this question) and that synchronized sound added very little; in fact, it might even inhibit visual experimentation. It was so easy to convey a story point with dialogue that lazy filmmakers would simply create photographed stage plays.

As a result, Arnheim is usually taken to be the summation of a certain strain of 1920s film theory. Like many earlier thinkers, Arnheim emphasized how film technique reshapes what is filmed. Close-ups, shot design, camera angles, and cutting make cinema no simple medium of reproduction. Film form transforms the world that is photographed. This position, commonplace today, was a real advance in the silent era and gave cinema artistic respectability, a subject that Arnheim reflected on thoughtfully in the 1933 edition of Film.

Again, Arnheim did more than synthesize current ideas. Theorists’ hunches that film stylized reality could now be grounded in Gestalt ideas about medium and form. In effect, Arnheim rewrote Film in the light of Art and Visual Perception, and the result was Film as Art. Here is the most famous passage:

Not until film began to become an art was the interest moved from mere subject matter to aspects of form. What had hitherto been merely the urge to record certain actual events, now became the aim to represent objects by special means exclusive to film. These means obtrude themselves, show themselves able to do more than simple reproduce the required object; they sharpen it, impose a style upon it, point out special features, make it vivid and decorative. Art begins where mechanical reproduction leaves off, where the conditions of reproduction serve in some way to mold the object (Film as Art, 57).

This, you might say, is Arnheim’s reply to Walter Benjamin’s theory of cinema as mechanical reproduction: no less than other artists, filmmakers use their medium, a photographic one, to create perceptually vivid effects akin to those in other arts.

Still, Arnheim held that film, like photography, has more limits than other arts. Tied to recording, film and photography can never achieve the range of expressive form we find in painting. I don’t believe this for a moment, but Arnheim clung to this opinion, I suspect, because of his deep love for creative freedom he found in other visual arts. And I sometimes think that for him, a painting harbored enough pushes, pulls, twists and torques. Movies just made explicit what was tactfully implied in still images.

Envoi

Kristin and I first saw Arnheim when we were graduate students at the University of Iowa, March 1972. He gave a lecture that stuck to his principles of 1933:

*Every art medium has a ceiling, beyond which it cannot effectively pass. The ceiling is somewhat low for the reproductive arts. Photography is more limited in what it can do than painting, and so is film.

*Films should be in black and white, the better to stylize reality. Are there no worthwhile color films? Pause. Red Desert, perhaps.

*Do you see many contemporary films? No.

Around 1980, I lined him up for a visiting lecture at UW. But he had to cancel; he had slipped on ice and broken his hip. He was then about seventy-five.

Later in the 1980s I visited Ann Arbor and had lunch with him. It was wonderful. By then I had read enough to ask him about Gombrich–an old friend and courtly opponent of his. (Read one of his reviews of Gombrich’s books to see what genuinely respectful disagreement looks like.) He saw pretty quickly that I was a Gombrichian and he gave a shrewd analysis of the dividing line: Gestalt psychology vs. ‘New Look’ cognitivism, illusions vs. expressive percepts, brain fields vs. schemas. He asked me to send me copies of my publications, which I did on and off during the decade. I never heard what he thought about my favorite fancy-pants sentence in Narration in the Fiction Film, when I contrasted J. J. Gibson’s theory of optical realism with Arnheim’s idea of expressiveness: “Gibson likes likeness, Arnheim loves liveliness.”

I thought of him often as I read more perceptual psychology. Gestalt work had once seemed to me a dead-end, but with David Marr’s theory of visual perception, a prototype of computational perceptual psychology, Gestaltism came roaring back. The “3D model representation” that Marr claimed operated in early vision uncannily echoes Arnheim’s discussion of our perception’s reliance on “characteristic aspects.” (Arnheim illustrates the idea with the various views of the chair, above. Which one is instantly recognizable as a chair?) And with contemporary interest in the relation between emotion and cognition, Arnheim’s theory of the expressive side of perception is creeping back too. Nothing worthwhile is forgotten, nothing goes away.

When we ran a book series at the University of Wisconsin Press, we were eager to publish an anthology of Arnheim’s film criticism, a collection originally published in German in 1977. Brenda Benthien, a close friend of Arnheim and his wife Mary, executed a lively translation and Arnheim supplied a touching introduction. A refugee of the Hitler years, an émigré across Europe and America, Arnheim summoned up the failure of the Weimar republic:

Even now I keep as a sort of talisman a bullet which in the days of the 1918 revolution, when I was fourteen, flew over the neighboring houses, bored a little hole through the windowpane, and fell inert on the carpet before my bed. Thus it began (Film Essays and Criticism, 3).

In the same introduction, Arnheim deplores the current state of cinema (“my basic objection to the talking film as a mongrel seems to me just as valid today as then”) and he warns against the cheapening of our vision:

Without the flourishing of visual expression no culture can function productively (5).

Aspiring film critics, and especially bloggers, should go back and read Arnheim on Keaton, Eisenstein, Gance, Pudovkin, Chaplin, von Sternberg, and other greats, as well as the essays “Style and monotony in film,” “Epic and dramatic film,” and especially “The Film Critic of Tomorrow.”

Scarcely a month goes by when I don’t have some idea that can be traced, however circuitously, to my reading of Arnheim. For instance, my blog on funny framings, posted a couple months ago, starts with his discussion of Chaplin’s The Immigrant. Arnheim’s theory of expression goes a long way toward explaining how composition can trigger laughter. I doubt that I’d be so alert to the possibilities of two-dimensional design in film shots if I hadn’t been tutored by Film as Art, Art and Visual Perception, The Power of the Center (1982, rev. 1988), his 1962 monograph on Picasso’s creative process in painting Guernica, and the essays in Toward a Psychology of Art (1966)–one of which is a skeptical review of Gombrich’s Art and Illusion. In preparing this entry, I found that my pleas that we probe the norms that guide filmmakers’ craft practices is just a clumsier restatement of this, which I discovered marked in Art and Visual Perception, the New Version:

Good art theory must smell of the studio, although its language should differ from the household talk of painters and sculptors (4).

Three years ago, after the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image convention in Grand Rapids, several of us from Madison–Ben Singer, Jen Chung, and Jonathan Frome–detoured back by way of Ann Arbor in order to call on Arnheim. He had just turned 100. He resided in an assisted-living facility, and his room was bright and clean, packed with books, remarkable drawings and paintings (Feininger, Köllwitz), a microfilm reader, and a worktable with a gigantic magnifying lens on an articulated arm. Conversation was difficult for him, but he seemed to understand everything we were saying. His smile was quick and his eyes were bright. When I showed him the first German edition of Film als Kunst I’d brought along, he turned it over in his hands as if he hadn’t seen one in years. He signed it, then shook his head apologetically at the shaky writing.

Now that Benjamin and Kracauer have become the prototypical Weimar intellectuals, it’s a pity that so many media students and professors are unaware of the importance of Arnheim’s work. His Leonardo-like interest in merging art and science is discouraged in a climate that posits the cultural construction of everything. He also writes with a grace and clarity that’s all too rare. In an unfashionable way, he exemplifies the passion, rigor, and dignity that interwar German intellectuals brought to the study of the arts. A lot of what he believed remains–what’s the word I want? Oh, yes–true.

Rudolf Arnheim, with Jonathan Frome, July 2004.

Line illustrations come from Art and Visual Perception.