Archive for the 'Books' Category

Ninotchka’s mistake: Inside Stalin’s film industry

DB here:

It’s a commonplace of film history that under Stalin (a name much in American news these days) the USSR forged a mass propaganda cinema. In order for Lenin’s “most important art” to transform society, cinema fell under central control. Between 1930 and 1953 a tightly coordinated bureaucracy shaped every script and shot and line of dialogue, while Stalin frowned from above. The 150 million Soviet citizens were exposed to scores of films pushing the party line.

True? Not quite.

When cows read newspapers

The Miracle Worker (1936).

In the film division of the University of Wisconsin—Madison, we’ve developed a reputation for revisionism. We like to probe received stories and traditional assumptions. In Soviet film studies, Vance Kepley’s In the Service of the State challenged the idealized portrait of Alexandr Dovzhenko, pastoral poet of Ukrainian film, by tracing his debts to official ideology. In my book on Eisenstein, I suggested that this prototypical Constructivist opens up a side of modernism that is artistically eclectic, and even conservative in its gleeful appropriation of old traditions.

Now we have a new book telling a fresh story. Maria (“Masha”) Belodubrovskaya’s Not According to Plan: Filmmaking under Stalin draws upon vast archival material to argue that filmmaking, far from being an iron machine reliably pumping out propaganda, was decentralized, poorly organized, weakly managed, driven by confusing commands and clashing agendas. Censorship was largely left up to the industry, not Party bureaucrats, and directors and screenwriters enjoyed remarkable flexibility.

draws upon vast archival material to argue that filmmaking, far from being an iron machine reliably pumping out propaganda, was decentralized, poorly organized, weakly managed, driven by confusing commands and clashing agendas. Censorship was largely left up to the industry, not Party bureaucrats, and directors and screenwriters enjoyed remarkable flexibility.

Was this an ideological juggernaut? Aiming at a hundred features a year, the studios were lucky to release half that. In 1936 95 films were planned, but only 53 were produced and 34 made it to screens. From 1942 on, those millions of spectators saw only a couple of dozen annually. The nadir was 1951, with 9 releases. (Hollywood studios released over 300.) The flood of propaganda was more like a trickle. Theatres were forced to run old Tarzan movies.

When quantity became thin, apologists claimed that quality was the true goal. But Ninotchka’s hope for “fewer but better Russians” wasn’t realized in the film domain. Critics and insiders admitted that nearly all the films that struggled into release were mediocre or worse.

Not According to Plan shows that Soviet institutions were incapable, by their size, organization, and political commitments, of organizing a mass production film industry. Efforts to set up something like the U.S. studio system ran up against obstacles: there weren’t enough skilled workers, and decision-makers clung to the notion of the master director. Boris Shumyatsky, who visited Hollywood and tried to create something similar at home, got his reward at the muzzles of a firing squad. But brute force like this was rare; there were few administrators and creators to spare.

The great plan was to have a Plan—specifically, a thematic one. Production would be based on an annual cluster of powerful topics like “Communism vs. capitalism” and “Socialist upbringing of the young.” Personnel were slow to realize that themes were not stories, let alone gripping ones, and the real work of imagination remained un-plannable. Starting from themes rather than plot situations, the overseers could judge only final results, which meant enormous investments in development and production—all of which might never yield a politically correct movie.

Production, wholly divorced from distribution and exhibition, couldn’t count on the vertical integration of Hollywood. Masha shows in rich detail how policies and routines worked against large-scale output. One of the most striking of those policies was the veneration of directors. A great irony of the book is that Hollywood filmmaking, with its platoons of screenwriters both credited and uncredited, was more collectivist than production in the USSR. Soviet directors enjoyed enormous stature and power. They were often the moving force behind a production, bringing on writers and then recasting the script during shooting. Assemblies of directors formed review committees, discussing and often defending their peers’ work. As Masha puts it:

The filmmaking community, and specifically film directors, never gave up on the standard of artistic mastery. They listened to the signals sent by the Soviet leadership, but then incorporated these into their own professional value system, which developed in the 1920s outside the purview of the state. Using the state’s discourse of quality and their peer institutions, they enforced their own shared norms of artistic merit.

The downside of this system, plan or no plan, was that when the film didn’t pass muster, the director was to blame. Yet the twenty or so “master” directors could survive failed projects. New talent wasn’t trusted; there were too few directors; and most basically, the organization of production remained artisanal. The role of the producer (let alone the powerful producer) scarcely existed. To a surprising extent, Soviet cinema encouraged the director as auteur. How’s that for revisionism?

Screenwriters weren’t as powerful, but they did their part. Masha has a fascinating chapter on the changing conceptions of the Soviet screenplay. The “iron scenario,” modeled on a Hollywood shooting script, was intended to lay out the film in toto, so directors couldn’t overshoot or make changes. This initiative, predictably, failed. There followed other variants: the butter scenario, the margerine scenario, and the rubber scenario (no kidding), then the emotional scenario and the literary scenario.

Masha traces the work process of screenwriting and the mostly futile efforts of literary figures to leave their stamp on a production. A similar stress on process characterizes her occasionally hilarious case studies of censorship. Some of these expose the limits of industry self-censorship. One agency signs off on a film, the next one castigates it, the next one reverses that judgment, Pravda weighs in, and finally Stalin speaks up—with a completely unpredictable verdict, à la Trump. The tale of Medvedkin’s The Miracle Worker, which jumped through all the hoops and wound up being banned after initial screenings anyhow, might have been written by Zoshchenko or Ilf and Petrov. Among the elements judged “absolutely impermissible” were shots of cows reading newspapers.

The artistic and popular success of Soviet films during the New Economic Policy (1921-1928) had spurred hopes for a mass-market sound cinema that was also of high quality. What crushed that dream? Masha gives us the hows (the machinations of the studios and government bodies) and the whys (the underlying causes and rationales). Not According to Plan is a trailblazing study of what she calls “the institutional study of ideology.” It’s also a quietly witty account of the failures of managed culture. How could artists be engineers of human souls if they couldn’t engineer a movie?

But go back to the quality issue. What were those Stalinist films like artistically?

Socialist Formalism

Three projects I’ve undertaken led me to Stalin-era cinema. Nearly all English-language film histories ignored it, or reduced it to boy-loves-tractor musicals. So Kristin and I wanted our textbook Film History: An Introduction to consider it. (Revisionism again.) My Cinema of Eisenstein and On the History of Film Style built on what I saw at archives in Brussels, Munich, and Washington DC.

As a result I sought to mount an argument that Stalinist cinema was worth our attention, especially from the standpoint of film technique. The run-of-the-mill productions seemed fairly shambolic, but the top-tier dramas revealed an academic style that interested me. Some films recalled, even anticipated, innovations taking hold in Europe and America, but other creative choices were surprisingly offbeat, and not what we associate with standard propaganda.

For one thing, it was clear that montage experiments didn’t end with the 1920s, the arrival of sound, or even the “official” establishment of Socialist Realism around 1934. Granted, classic continuity editing rules the fiction films of the 1930s and 1940s, and the most flagrant extremes of the montage style were purged.

But some moments recall the silent era. These passages are typically motivated, as in Hollywood and other national traditions, by rapid action. Military combat calls forth stretches of 2-4 frame shots of bombardment in The Young Guard, Part 2 (1948). The combat scenes of The Battle of Stalingrad (1949) include very brief shots. In one passage, an artillery blast consists of three frames—one positive, a second negative, and a third positive again, creating a visual burst.

The abrupt disjunctions of the 1920s style can be felt a little in one cut of The Fall of Berlin (1950), when at the end of a long reverse tracking shot, Alyosha and his comrades rush the camera. Cut to Hitler recoiling, as if he sees them.

As you’d expect in an academic tradition, the use of fast cutting for fast action isn’t disruptive. A little more unusual is the embrace of wide-angle lenses, often more distorting than in Western cinema. Wide-angle imagery was used by 1920s filmmakers, often to caricature class enemies or to heroicize workers. The same sort of thing can be seen in Kutuzov (1945), when a soldier is presented in a looming close-up, or in Front (1943), when a gigantic hand reaches out for a telephone.

This use of wide angles to give figures massive bulk continued through the 1950s, as in The Cranes Are Flying (1957).

The 1940s aggressive wide-angle shots run parallel to Hollywood work, when in the wake of Citizen Kane (1941), The Little Foxes (1941), and other films, many directors and cinematographers created vivid compositions in depth. Those weren’t unprecedented in America, as I try to show in the style book, but there were some early adopters in Russia as well.

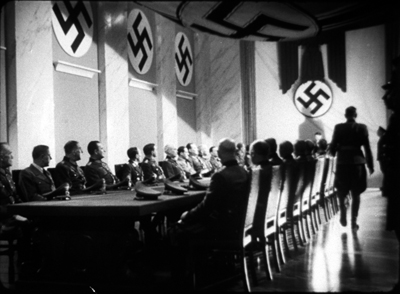

Obliged to show meetings of saboteurs, workers, generals, and party leaders, Soviet filmmakers had to dramatize people in rooms, talking at very great length. The result was a tendency toward depth staging and fairly long takes. The low-angle depth shot stretching through vast spaces became a hallmark of this academic style in the 1930s and after.

Director Fridrikh Ermler, one of the few directors who was a Party member, claimed that he devised a “conversational cinema” to deal with the prolix dialogue scenes in The Great Citizen (1937, 1939). The movie teems with shots that wouldn’t look out of place in American cinema of the 1940s.

As a solution to the problem of talky scenes, staging of this sort makes sense as a way to achieve some visual variety, and to show off production values. By the 1940s, such flamboyant depth became even more exaggerated. We see it in the telephone framing from Front above, as well as in The Young Guard Part 1 (1948, below left) and the noirish stretches of The Vow (1946, below right).

The Fall of Berlin can use depth to contrast the placid self-assurance of Stalin with a ranting Hitler, bowled over by his globe. Is this a reference to the globe ballet in The Great Dictator?

It’s well-known that for Kane Orson Welles and Gregg Toland wanted to maintain focus in all planes, sometimes resorting to special-effects shots to do so. The Soviets valued fixed focus as well, as several shots above suggest. It could be maintained if the foreground plane wasn’t too close, and the depth of field would control focus in the distance. Hence many shots use distant depth. At one point in The Great Citizen, when a woman interrupts a meeting, the official in the foreground trots all the way to the rear to meet her.

The sense of cavernous distance is amplified by the wide-angle lens.

But sometimes pinpoint focus in all planes wasn’t the goal. Another way to activate depth was to rack focus. In this scene of Rainbow (1944), the man who has betrayed the village comes home and discovers a delegation waiting to try him. At first they’re out of focus, but when he turns they become visible.

Focused or not, some of these shots push important action to the edge of visibility in a way that would be rare in American cinema. In A Great Life, a snooper is centered but sliced off by a window frame and kept out of focus, while a trial scene is interrupted by a figure far in the distance who bursts in to announce a mine collapse.

The Great Citizen shows Shakhov discussing a suspect, who hovers barely discernible in the background over his left shoulder. I enlarge the fellow and brighten the image.

This makes Wyler’s sleeve-shot in The Little Foxes seem a little obvious.

The Great Whatsis and the masters of the 1920s

The New Moscow (1938).

If American movies favor titles called The Big …., the Soviets liked The Great …. (Velikiy). But The Big Sleep doesn’t look all that big, and The Big Sick is big only to a few people, and The Big Knife doesn’t even have a knife. In the USSR, calling something big summoned up monumentality. Stalinist culture was grandiose in its architecture, sculpture, painting, literature, and even music, with symphonies of Mahlerian length and oratorios boasting hundreds of voices.

Accordingly, one effect of the depth aesthetic was to grant the characters and their settings a looming grandeur. Earth-changing historical events were being played out on a vast stage that framing and set design put before us.

Naturally, battles are on a colossal scale. Napoleon broods in the foreground (Kutuzov) and troops march endlessly to the horizon (The Vow).

1940s films feature wartime landscapes on a scale almost unknown to Hollywood. If God favors the biggest battalions, God would seem to love the Russians (a prospect that otherwise seems invalidated by history). Below: The Battle of Stalingrad.

These landscapes are surveyed in long tracking shots, a habit that survived in Bondarchuk’s War and Peace (1966-1967).

Soviet forces command impressive headquarters (The Great Change, 1945), perhaps necessary to balance the Nazis’ resources (The Vow).

Parlors and committee rooms are remarkably big, and even prison cells (The Young Guard Part 2) and farmhouses (The Vow) have plenty of room.

Gigantism wasn’t unknown in 1920s cinema, or in Russian painting both classic and recent. The Vow seems to justify its scale by reference to a Repin painting, which the characters see on display.

Not only were the 1920s silent classics monumental; they became monuments. Masha records the veneration that the “master” directors felt for the works of Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Kuleshov, Barnet, and other predecessors. Moments in the Stalinist cinema seem to refer back to that era. The Battle of Stalingrad evokes the mother with the slain child on the Odessa Steps, and The Vow has the nerve to superimpose on Stalin (friend of farmers) an image of concentric plowing from Old and New.

These can be taken as cynical ripoffs, but in a way they testify to the fact that great silent films had forged some enduring iconography.

VIP: Very important, Pudovkin

You don’t hear much about Pudovkin’s 1930s and 1940s films, but they can be exuberantly strange. Eisenstein aside, he stands in my viewing as the director who played around most ambitiously with the academic style. Perhaps he was encouraged in this by his young codirector Mikhail Doller, but Pudovkin had already tried out some audacious strokes in A Simple Case (1932) and Deserter (1933).

For a high Stalinist example take Minin and Pozharsky (1939). This tale of seventeenth-century warfare seems virtually a reply to Alexander Nevsky (1938), as Mother (1926) responded to Strike (1925). Minin opens with statuesque staging reminiscent of Eisenstein’s film, but the scene is handled in telephoto shots and to-camera address. The combat scenes employ handheld battle shots, along with close-ups of fighters and horsemen that aren’t stylized in the Nevsky manner.

But there’s more than pastiche here. One battle shows the Russian forces rushing from the left in tight tracking shots, while the enemy forces move from the right in panning telephoto. Especially striking are axial cuts, beloved of Soviet filmmakers for static arrays, employed in movement. Horses sweep past a tent in extreme long-shot; they smash into the tent in long shot; and in a closer view the tent lies trampled as other horses continue to flash through the foreground.

The shots are 50 frames, 38 frames, and 13 frames respectively. For a moment, we might be back in the great era of Soviet editing.

Victory from 1938 is a drama in which aviators set out to rescue an interrupted around-the-world flight. Here Pudovkin and Doller invoke the depth staging of the era only to disrupt it with what we might call “smear” cuts.

During the parade for the departing airmen, for instance, a young man happily tossing papers, in another grotesque wide-angle shot. He’s blocked by a man passing through the frame. Match on action cut to another figure, close to the camera and moving in the same direction. This figure wipes away to reveal a man reading a newspaper.

This sort of weird graphic match becomes a stylistic motif in the film. Later, when the rescue has been completed, another crowd scene yields a similar pattern of depth smeared and exposed. A shot of the parade is sheared off by a woman’s passing face. That cuts to a man’s passing face, which moves away to show the crowd behind him.

The patterning pays off when the victorious plane rolls triumphantly through the frame, blotting out the image, to be graphically matched by a passing figure who unveils the pilot’s mother embracing him.

In Admiral Nakhimov (1947) Pudovkin and Doller employ the smear-cutting technique during a battle scene. Stills are totally unable to capture the way this looks. Soldiers charge up a hill, and their falling bodies, briefly blocking the camera’s view, are given in jump-cut repetitions that suggest, through a spasmodic rhythm, the sheer difficulty of advancing.

Even stranger is the moment when soldiers rush toward a distant fortification, with a latticework basket in the foreground. Cut to the hill edge, with a comparable blob moving leftward through the frame. It turns out to be a fighter’s shoulder.

The oddest part is that this second shot is only six frames long, and every frame after the first is a jump cut; that is, some frames have been dropped as the blob makes its way across the image. The effect on your eye is percussive, and seems to be anticipated by Pudovkin’s experiments in popping black frames into shots in A Simple Case. What kind of director thinks like this?

Of course these Pudovkin/Doller films also subscribe to the official look, with monumental depth staging. The films acknowledge the 1920s tradition as well. Admiral Nakhimov casts a personal look back to Pudovkin’s great rival. A shot of the crew’s tautly bulging hammocks recalls, maybe cites, the crew’s sleeping area of Potemkin.

In Odessa, Admiral Nakhimov echoes Potemkin even more strongly. We get waving crowds, the stone lions, and a reminder of those famous steps.

In sum, the Stalinist cinema holds a unique interest for students of the history of film style. Not only did it apparently constitute a significant development in technique, but in forming a tradition, it provided a counterpart and sometimes a counterpoint to developments in the West. Later that tradition became something for directors to react against (Tarkovsky and Sokurov come to mind) or to adapt to new purposes (I’d put Jancsó in that category). For all the behind-the-scenes bungling, it became much more than a propaganda vehicle.

Scholars who study Stalinist film are usually impelled by an interest in propaganda or an interest in the audience’s response. My questions were different. I was driven by my interest in Eisenstein and comparative stylistics. So I tried to investigate the formal and stylistic norms of Soviet cinema. Some of those norms Eisenstein helped create, and then revised for his own ends.

Still, I feel like a butterfly collector picking out vivid specimens for an expert to explain. I can’t supply the hows and whys. How did filmmakers manage to create these remarkable images? What technical resources, of lenses and lighting rigs and film stock and set design, permitted them to craft these striking shots? Were their peers and masters insensitive to this official look? Was it taken for granted? Or was it self-consciously promoted and taught? Some of these schemas are developed in Eisenstein’s lectures at the Soviet film school. And how, at a more micro-level, do these patterns function in the individual films?

As for the whys: Why did filmmakers embrace these options rather than others? And why did they develop, sometimes apparently in a spirit of play, some oddball technical innovations?

Such questions seem to me compelled by films that turn out to be more artistically interesting than most commentators have noted. One of the most corrupt and brutal political systems in world history produced films of considerable interest, and a few of enduring value. I hope experts try to figure this all out. I bet Masha Belodubrovskaya will lead the way. Her new book is a splendid start.

Masha is no stranger to this blog, having translated Viktor Shklovsky’s remarkable “Monument to a Scientific Error” for us.

This is a good place to thank all the people who helped me see Stalinist films in archives over the decades. That number includes Gabrielle Claes, Nicola Mazzanti, and the late Jacques Ledoux of the Belgian Cinematek; Enno Patalas, Klaus Volkmer, and Stefan Droessler of the Munich Film Museum; and Pat Loughney, then of the Library of Congress.

I learned of Ermler’s “conversational cinema” (razgovornyi kinematograf) from Julie A. Cassiday’s “Kirov and Death in The Great Citizen: The Fatal Consequences of Linguistic Mediation,” Slavic Review 64, 4 (Winter 2005), 801-804. The depth aesthetic of high Stalinist cinema proved valuable when 1960s bureaucrats decided to make Stalin disappear. See our online supplement to Film History: An Introduction.

There are more examples of “Stalinist formalism” in On the History of Film Style–recently declared out of print, but soon to appear in a new electronic edition on this site. See also my Cinema of Eisenstein for arguments about how he created and then swerved from some of his peers’ norms.

Today’s Google Doodle pays tribute to Eisenstein on his birthday. But they make him a slim, hip metrosexual. Revisionism can go too far.

Kelley Conway, Masha, and Scott Gehlbach, at a party last night celebrating Masha’s book–and her winning tenure! Kelley’s contributions to our blog are here and here and here.

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD: Post-partum downs and ups

The Human Comedy (1943).

DB here:

Some authors think that once their book is published they can lean back and wait to hear what people think. On the contrary. Sometimes the care and maintenance of your book continues well after the publication date.

For one book I did, the university press had promised to run an ad in Film Quarterly. When no ad appeared, I was told that since the press itself published Film Quarterly, it had to yield space to publishers who actually paid for their ads. On a more memorable occasion, a catalog listing the season’s titles from Harvard ran a picture of me that showed a different guy. Someone had chosen a shot of the distinguished literary critic and political commentator David Bromwich, who’s regrettably better-looking than me.

Most recently, I just learned that Harvard has put my On the History of Film Style out of print. (Snif.) It was a favorite of mine, and over its twenty years it sold decently, over 10,000 copies. But with all those stills it’s an expensive book to reprint, and so the rights have reverted to me. I hope to revive it somehow, perhaps in print as I did with the Harvard orphan The Cinema of Eisenstein, kindly picked up by Bill Germano, then of Routledge. Or I might go the digital route, creating a straight-up pdf of the old version (as happened with Kristin’s Exporting Entertainment), or something fancier, as with the 2.0 edition of Planet Hong Kong (another book Harvard discharged). Today we Dr. Frankenstein authors have a lot of ways to jolt our creatures back to life.

Most recently, I just learned that Harvard has put my On the History of Film Style out of print. (Snif.) It was a favorite of mine, and over its twenty years it sold decently, over 10,000 copies. But with all those stills it’s an expensive book to reprint, and so the rights have reverted to me. I hope to revive it somehow, perhaps in print as I did with the Harvard orphan The Cinema of Eisenstein, kindly picked up by Bill Germano, then of Routledge. Or I might go the digital route, creating a straight-up pdf of the old version (as happened with Kristin’s Exporting Entertainment), or something fancier, as with the 2.0 edition of Planet Hong Kong (another book Harvard discharged). Today we Dr. Frankenstein authors have a lot of ways to jolt our creatures back to life.

There are still used copies of On the History…. on Amazon. This is a Good Thing. Still, the Age of Amazon creates other post-partum problems.

In conversation and email, I’ve been hearing from people about the Big Cahuna’s treatment of my 40s book. At first Amazon promised to ship copies on the publication date, 2 October (although the University of Chicago Press was shipping copies a week or so before). Nothing happened. Then Amazon third-party sellers offered copies pronto at $30, $10 less than cover price. Then Amazon joined the fray by offering copies at $32 with Prime membership, thereby undercutting those outlets charging for shipping. This is dynamic pricing in fast motion. Such fluctuating pricing by Leviathan’s algorithms must drive publishers crazy.

Still with me? Those other outlets sold their copies, leaving Amazon the sole vendor. The price went back up to list, $40. For the last ten days Amazon has claimed that the book is out of stock, with no shipping date yet determined. This morning, the algorithm declared that one copy was available, but more were coming soon. Sure enough, as I sat down to write this entry, Amazon was offering copies, with Prime, at $40.

But I just checked again and–Amazon has just reverted to competing with third-party vendors offering it between $26 $31.71 and $41 $45.79. Who’s the nervy profiteer who charges a dollar $5.79 above list? (Prices revised as of 13 October.)

So hurry! These prices won’t last long! (Of that you can be sure.) If you want stability and fast delivery at the original price, you can go to the University of Chicago site.

I know, I know: First-world problems. So let me end by thanking two critics for their generous reviews, newly hatched. Both understood that I was aiming for a broad scope, trying to stress the breadth of storytelling innovation of the period. Given that emphasis, in Film Comment, Nick Pinkerton understood why I inserted interludes on particular films and filmmakers:

Tony Rayns in Sight & Sound rightly saw the book as trying to do something different from auteur studies, but he too got that the Interludes tried to right the balance by going deep on particular classics and directors.

Tony is right about the book’s giving Menzies short shrift, but I’ve devoted some attention to him elsewhere (here and here). Blogging has been a good way to offload material that I decided to keep out of the book. Likewise, maintaining this site allows me to post clips of 40s films I talk about. Feel free to check them out.

I thank these reviewers, and any of this blog’s readers who have bought the book.

Next up, and for free: One last big job.

Neither Nick’s nor Tony’s review is online, as far as I know.

As usual, I owe massive thanks to Rodney Powell, Melinda Kennedy, and Kelly Finefrock-Creed. They and their colleagues have made the production, and post-production, of this book exceptionally un-traumatic.

For more background on my Forties research, see the category 1940s Hollywood. I commemorate the day I shipped out the damn thing here. No, I don’t blog in my pajamas, but I do sleep in my clothes.

P.S. 12 October 2017: Alert reader Geoff Gardner points out that today the not-so-failing New York Times published Douglas Preston’s explanation of how Amazon’s new algorithm pushes gray-market “new” books. Thanks to Geoff! Check out his Film Alert 101 blog.

The Curse of the Cat People (1944).

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD: Out of the past

Cover Girl (1944).

DB here:

I just got my first copy of Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. I’m always scared to look at a published piece because I expect my eye to light on (a) a misprint; or (b) a sentence of unusual clumsiness or simplemindedness. Other writers have told me they have similar qualms. But I did look, and on this fat volume: so far, so good. It even has black, slightly corrugated endpapers, like the paper inside a box of chocolates.

This was a personal project for me, for reasons I’ve sketched elsewhere on this site. I grew up watching 1940s films on TV and have always had a fondness for what James Naremore has called “the beating heart of Hollywood.” In my teen years, watching Welles and Hitchcock movies along with B films and minor musicals fed my interest in studio cinema.

When I started teaching in the 1970s, I was keen to catch up with all those nifty movies sitting comfortably in our Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. My classes screened His Girl Friday (in a pirate copy) and Meet Me in St. Louis and Possessed and The Locket and White Heat and The Ministry of Fear and many more. Students working with me studied Gothics, war films, and I Remember Mama. It was then I started to realize just how creative this period was.

One piece of boilerplate for the book puts it more melodramatically.

In the 1940s American movies changed. Flashbacks began to be used in outrageous, unpredictable ways. Viewers were plunged into characters’ memories, dreams, and hallucinations. Some films didn’t have protagonists. Others centered on anti-heroes or psychopaths. Women might be on the verge of madness, and neurotic heroes were lurching into violent confrontations.

Films were exploring parallel universes and supernatural dimensions. Characters switched bodies or intuited the future. Combining many of these ingredients, there emerged a new genre—the psychological thriller, populated by murderous spouses and witnesses who became targets of violence.

If this sounds like our cinema of today, that’s because it is. In Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, David Bordwell examines for the first time the range and depth of the 1940s trends. Those trends crystallized into traditions. The Christopher Nolans and Quentin Tarantinos of today owe an immense debt to the dynamic, occasionally delirious narrative experiments of the 1940s.

Bordwell shows that the booming movie market at the start of the Forties allowed ambitious writers and directors to push narrative boundaries. He traces how Orson Welles, Preston Sturges, Alfred Hitchcock, Otto Preminger, and dozens of lesser-known creators built models of intricate plotting and psychological complexity.

Those experiments are usually credited to the influence of Citizen Kane, but Bordwell shows that the experimental impulse had begun in the late 1930s, in radio, fiction, and theatre before migrating to cinema. And even with the late 1940s recession in the industry, the momentum for innovation could not be stopped. Some of the boldest films of the era came in the late forties and early fifties, when filmmakers sought to outdo their peers.

Through in-depth analysis of films both famous and virtually unknown, from Our Town and All About Eve to Swell Guy and The Guilt of Janet Ames, Bordwell analyzes the era’s unique ambitious and its legacy for future filmmakers.

Today I’d like to give you some background on the book and flag a new page on this site you might find of interest. (If you can’t wait, you have permission to go there now.)

Questions, questions

Kitty Foyle (1940).

Reinventing Hollywood turned my enthusiasm for the 1940s into a set of questions.

The enthusiasm was based on a hunch that Hollywood cinema between 1939 and 1952 saw a burst of innovative storytelling. The innovations weren’t utterly new, but they differed from what was seen in the 1930s by virtue of their range, number, and complexity. The more I looked, the more I realized that the Forties recaptured the narrative range and fluidity of silent cinema, extending and nuancing it with sound. In essence, a new set of norms emerged, forged by many filmmakers.

Several questions followed. How to describe those innovations? How to chart their range and variations? How to analyze their effects—on the sort of stories told, on how viewers understood them? How did the innovations alter genres, or create new ones? How might we explain the rise and expansion of these new norms? And finally, what sort of legacy did this process of changing conventions leave to the filmmakers that followed? In all, how did various trends coalesce into a tradition?

This plan, ridiculously ambitious, at least has the virtue of originality. Most books about the 1940s concentrate on major figures—stars, producers, directors, the Hollywood Ten. Other books explain how studios or censorship or labor disputes worked. Others focus on genres such as the musical or the melodrama or the combat film. A popular option is devoted to that not-quite-a-genre film noir. These are all worthy subjects. And there’s no shortage of books seeing 40s film as a reflection of wartime or postwar America, or the geopolitics of the Cold War.

Studying narrative norms cuts across many of these common perspectives. Individuals matter, particularly ambitious screenwriters, producers, and directors striving to tell stories in unusual ways. But institutions matter too, as studio culture and writers’ associations prized a degree of originality in plotting or point of view. And narrative devices cut across genres to a considerable degree. Although flashbacks have come to be associated with film noir, they actually appear in all genres, and take on different roles accordingly.

So, 621 films later, my project has become an effort to contribute to a history of film form—the various storytelling methods that filmmakers have developed in different times and places. (In other words, a poetics of cinema.) In effect, I’m asking that the kind of appreciation people show for genres, actors, and auteurs be stretched to narrative strategies as well.

Darryl F. Zanuck, with his shrewd narrative instinct, gave me my epigraph.

It is not enough just to tell an interesting story. Half the battle depends on how you tell the story. As a matter of fact, the most important half depends on how you tell the story.

The book in between

Daisy Kenyon (1947).

The project blended in with earlier work I’d done, particularly in The Classical Hollywood Cinema and The Way Hollywood Tells It. In a sense, Reinventing Hollywood is a bridge between those two books.

CHC, written with Kristin and Janet Staiger, traced continuity and change in the studio storytelling tradition from its inception to 1960. It analyzed how conventions of story, style, and work practices were established and maintained over the decades. The Way Hollywood Tells It suggested that after 1960, the broad conventions remained in place but were modified in particular ways.

In passing, I suggested that innovations of “contemporary Hollywood” owed a lot to experiments launched in the 1940s. The new book tries to pay off that IOU. Reinventing Hollywood asks how, within the broad conventions of classical Hollywood, particular innovations could emerge in the boom-and-bust 1940s. Many standard devices of our films today, from voice-over and fragmentary flashbacks to block construction and tricks with point of view, can be traced back to the Forties, when they were consolidated and refined.

The two earlier books also considered film technique—staging, shooting, editing, and the like. Reinventing Hollywood doesn’t tackle visual style, for two reasons. It would have doubled the book’s length, and I’ve said my say on 40s style in other work. Style shapes story, of course, and I’ve tried to take this factor into account. But I concentrate on the principles of story world, plot construction, and narration—the three dimensions of narrative I’ve outlined elsewhere.

None of these books is auteurist in basic orientation, but they aren’t anti-auteurist either. Surveying techniques in a systematic way helps call attention to adepts, middling talents, and innovators. In Reinventing, I think the interludes on Mankiewicz, Sturges, Welles, and Hitchcock show how skillful filmmakers mobilized emerging conventions in powerful ways. In effect, we reconstruct a menu of options to sense the values in picking and mixing them. For example, Citizen Kane‘s investigation plot, adorned with a dying message and a bevy of flashbacks, was a vigorous synthesis of devices that were circulating through film and other media in the late 1930s. The boldness of the effort made it influential on what followed. We get a better sense of directors’ (and writers’ and producers’) idiosyncratic strengths when we know the norms they’re working with, and sometimes against.

Reinventing Hollywood, running nearly 600 pages, makes The Rhapsodes look scrawny. But it isn’t the behemoth that CHC is. CHC could give this book noogies.

The big and the small

The Bishop’s Wife (1947).

It was hard to discuss broad trends and still probe particular cases in detail. So the chapters move from generalities to specifics in steps. Some films are merely mentioned, others described briefly, others considered at greater length, and some analyzed in depth. After a conceptual introduction and a historical panorama of Hollywood as a creative community (Chapter 1), there are chapters on flashbacks, plot construction, woven versus chaptered plots, manipulation of viewpoint, voice-over, character subjectivity, psychoanalytic plots, realism and fantasy, mystery plots, and self-conscious artifice. The conclusion looks at the impact of the period on later filmmakers.

I try to go beyond obvious observations to study the mechanics of familiar devices. So I come up with terms and concepts to pick out finer-grained tactics: the breadcrumb trail that sets up many flashbacks, block construction, hooks, switcheroos, and the like.

The chapters on particular techniques are broken by “interludes” devoted to particular movies or moviemakers. Some of these interludes involve well-known films and figures, but others look at obscure items. (Yes, The Chase is involved.) Even the treatment of Big Names tries to offer something original, as when I argue that Hitchcock and Welles pushed 40s innovations very far and sustained them throughout their later careers.

Here’s the table of contents, with small annotations

Introduction: The Way Hollywood Told It

Chapter 1: The Frenzy of Five Fat Years (Hollywood as an ecosystem)

Interlude: Spring 1940: Lessons from Our Town

Chapter 2: Time and Time Again (flashbacks)

Interlude: Kitty and Lydia, Julia and Nancy

Chapter 3: Plots: The Menu (conventions of plot structure)

Interlude: Schema and Revision, between Rounds

Chapter 4: Slices, Strands, and Chunks (alternative structural options)

Interlude: Mankiewicz: Modularity and Polyphony

Chapter 5: What They Didn’t Know Was (managing narrative information)

Interlude: Identity Thieves and Tangled Networks

Chapter 6: Voices out of the Dark (voice-over)

Interlude: Remaking Middlebrow Modernism

Chapter 7: Into the Depths (subjectivity)

Chapter 8: Call It Psychology (psychoanalytic films)

Interlude: Innovation by Misadventure

Chapter 9: From the Naked City to Bedford Falls (realism, fantasy, and in-between)

Chapter 10: I Love a Mystery (thrillers and mystery-based plotting)

Interlude: Sturges, or Showing the Puppet Strings

Chapter 11: Artifice in Excelsis (self-conscious display of conventions)

Interlude: Hitchcock and Welles: The Lessons of the Masters

Conclusion: The Way Hollywood Keeps Telling It (legacy of the 1940s)

To keep things specific, I’ve prepared eleven film clips keyed to particular analyses. Just playing the clips might give you a sense of the book’s range. They’re also fun in their own right.

No zeitgeists, please

Blues in the Night (1941).

Two last points. One bears on preferred explanations. How do we explain why cinematic innovation burst out at this particular time? Again, the book tries to pursue an uncommon path.

Many writers look to a zeitgeist—the anxieties of war, the anxieties of postwar adjustment, the anxieties of the anti-Communist crusade, any anxiety you can imagine. Instead I try to look for institutional factors shaping the films’ norms. Centrally, there are the conditions of the film industry, with its rich interplay of personnel and story materials shuttling all over the place. There are also the cinematic traditions themselves, such as plots depending on amnesia. Particularly important are the adjacent arts, including theatre, radio, and popular fiction. All these sources get modified by a process of schema and revision—borrowing something already out there but warping it to new ends. In short, instead of looking for remote causes in the broader society, I try to locate more proximate ones within the filmmaking community and the turmoil of popular culture.

Someone might argue that this just pushes the problem back a step. Don’t social anxieties surface in all these media? To this I’d argue, as I did here and here, that those anxieties are very hard to identify. Not all anxieties or concerns will be shared by a populace (viz. our current political situation). And we can’t establish a strong causal connection between them and the products of popular media—especially since media are indeed mediated, by tastemakers, gatekeepers, and the institutions that produce popular culture.

For the period I’m concerned with, James Agee noted the role of mediators in his complaints aimed at the film-as-dream sociologists of the period:

It seems a grave mistake to take [movies] as evidence as definitive, as from-the-public, as if 40 million people had actually dreamed them. Take the far simpler case of advertising art. The American family, as shown therein, is not only not The Family; it isn’t even what the American people imagines as The family. It is A’s guess at that, subject to the guesswork of his boss, which is subject in turn to the guesswork of the client. At best, a queer, interesting, possible approximation, but certainly never definitive. In movies many more people take part in the guesswork, but not enough to represent a population: and many more accidents and irrelevant rules and laws deflect and distort the image.

A movie does not grow out of The People; it is imposed on the people— as careful as possible a guess as to what they want. Moreover, the relative popularity or failure of a picture, though it means something, does not at all necessarily mean it has made a dream come true. It means, usually, just that something has been successfully imposed.

Instead of social reflection, we should expect refraction. Decision-makers opportunistically grab memes and commonplaces (the unhappy housewife, the juvenile delinquent, the returning vet) in hopes they can make something appealing out of them. They absorb those into familiar (narrative) forms. We get, then, not a “vertical” or top-down flow of social anxieties into artworks, but a “horizontal” ecosystem, a dynamic of exchange and transformation. The creators copy one another, obeying local norms while also resetting boundaries. This process includes selective assimilation of ideas thrown up by the culture, and it gets amplified by network effects, as sticky ideas themselves get copied. In other words, ideology doesn’t turn on the camera. The final film is always mediated by humans working in institutions, and both the people and the institution have many agendas.

A second point follows. Working on this book brought home to me how much film owes to other media. In a way, Forties cinema became more “novelistic” because it sought to assimilate techniques of split viewpoints, replays, inner monologue, and subjective response characteristic not so much of modernism (those were old hat by the 1940s) but of popular fiction and what we might call “middlebrow modernism.” A Letter to Three Wives (1948) attaches itself in turn to three women, each with memories of the past, with that trio interrupted by a never-seen fourth woman mockingly narrating the tale. It’s a cinematic treatment of the shifting viewpoints and personified narrative voices to be found in the nineteenth-century novel (Dickens, Collins, James) and later in genre fiction, not least in mystery tales. (It’s also a modification of the source novel.)

But you could also argue, as André Bazin did, that the 1940s saw a new “theatricalization” of cinema, with self-conscious adaptations that stressed stage conventions like the single-setting action. And of course radio supplied important prototypes for acoustic texture and first-person voice-over. Each of these devices wasn’t simply ported over to film; moving images and recorded sound gave literary, theatrical, and radio-based techniques new expressive possibilities. And all depended on the churn of people working side by side to innovate within familiar norms.

Every author discovers or remembers too late those things that should have been mentioned. Doug Holm reminded me of the dream narrative of Sh! The Octopus (1937). Jim Naremore pointed out that Rex Stout had already done my work for me in Too Many Women (1947, year of my birth), when Archie reports, “It was a wonderful movie . . . Only two people in it have amnesia.” On a different pathway, I’d love to do more research on moguls’ screening rooms as a condition of influence. (They could borrow films from rival studios without charge.) Julien Duvivier is a minor hero of my book, but only after the book was submitted did I see his L’Affaire Maurizius (1954), a perfect extension of 1940s storytelling to a French milieu.

And just recently I found a nice confirmation of the unexpected byways of the ecosystem. According to the author, the figure of the “psycho-neurotic” returning soldier was at first mandated by government policy but then twisted by ambitious screenwriters into tales of civilian madmen. The article has the enviable title: “That Psycho Story Swing Is No Cycle; It’s Now an Obsession.” If you buy the book, please write that into the endnotes.

And for the third time, feel free to visit the clips page!

I owe a lot to several people who saw this book through publication. Foremost are my editor at the University of Chicago Press, Rodney Powell, and his colleagues Melinda Kennedy and Kelly Finefrock-Creed. Then too there is Bob Davis, who supplied the book’s jacket photograph; Kait Fyfe, who prepared the clips for posting; and web tsarina Meg Hamel who set up the clips page. My other debts are recorded in the acknowledgments, but of course I must mention Kristin who had the hardest job of all. She had to put up with the author.

My Agee quotation comes from “Notes on Movies and Reviewing to Jean Kintner for Museum of Modern Art Round Table (1949),” in James Agee, Complete Film Criticism: Reviews, Essays, and Manuscripts, ed. Charles Maland (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2017), 975. I’m indebted to Chuck for sharing this with me. Chuck’s discussion of Agee on our site is well worth a read.

Many entries on this site are dedicated to 1940s Hollywood. See the relevant category. “Murder Culture” has been revised as a chapter in the book. On 1940s visual style, see Chapter 27 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema, Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style, and entries under 1940s Hollywood. There’s also the web essay on William Cameron Menzies. My most detailed arguments against social reflection and zeitgeists in historical explanations comes in the title essay in Poetics of Cinema, pp. 30-32.

Although the Amazon page offering Reinventing Hollywood says copies aren’t available until October, it seems that copies are shipping now from Chicago’s webpage. Amazon offers no discount on the title. (See P.S.) It’s currently available only in hardcover, with a paperback planned for the distant future.

P.S. 27 Sept 2017: Actually, Amazon is now discounting Reinventing Hollywood; it’s $30.77, as opposed to the $40 list price.

P.P.S. 13 October: Amazon’s prices on the thing have been fluctuating wildly. See this entry. Those wild and crazy algorithms!

Our Town (1940).

Books not so briefly noted

“What a piece of junk!” Star Wars: Episode IV–A New Hope.

DB here:

Over there, across the room, a stack of more or less recently published books has haunted me for months. I wanted to tell you about them. True, I had plenty of excuses: My stay in Washington, a health nuisance, our trip to Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, and our looming deadline for a new edition of Film History: An Introduction. But excuses aren’t necessarily good reasons. My delay was especially painful because the books were by friends.

So here’s some penance. As usual, some of the books I’ve read completely; others I’ve read only stretches of. But each is on a fascinating subject, by people of sound mind and impeccable character–in other words, exceptional researchers, thinkers, and writers.

Christine N. (Noll) Brinckmann is both a critic and a filmmaker. In Color and Empathy, she brings hands-on expertise to two subjects too often ignored. Her essays treat the handling of color in silent cinema, 1950s Hollywood, experimental film, and Claire Denis’s Beau Travail. On the empathy side, she analyzes its role in documentary, Hitchcock films, and Eric de Kuyper’s Casta Diva.

Christine N. (Noll) Brinckmann is both a critic and a filmmaker. In Color and Empathy, she brings hands-on expertise to two subjects too often ignored. Her essays treat the handling of color in silent cinema, 1950s Hollywood, experimental film, and Claire Denis’s Beau Travail. On the empathy side, she analyzes its role in documentary, Hitchcock films, and Eric de Kuyper’s Casta Diva.

Noll is very good on what I’d call the “historical poetics” of color, starting from perceptual and technical aspects and moving to the ways conventions emerged historically. For example, she contrasts Pal Joey and Chungking Express: sharp-edged versus blurred, object colors versus ambient colors, narratively motivated color clusters versus poetic and associational ones. She introduces the useful concept of color “chords,” mingled hues that create motifs that weave through the film. With this concept she’s able to treat late 1950s Hollywood color comedies as having a “mannerist” style, with chords dissolving into moments of patches of pure abstraction. She finds this strategy in some very unexpected places; I never thought I’d need to look at Bob Hope’s Bachelor in Paradise again, but now it’s a must.

As a filmmaker, Noll is also sensitive to the bodily reactions of viewers. Empathy is one such general phenomenon. What I appreciated in her discussion was her eagerness to go beyond the usual sense of the term, which involves feeling for characters in an emotional register. By analyzing passages in Secret Agent and Frenzy, she also considers how visceral factors like motor mimicry play into our responses. She takes the face as the main arena of empathy, but gestures–like cracking open fingers closed in death–are central as well. Thanks to empathy, she notes, films align us with some fairly unpleasant people. “We have not invested any sympathy in the characters; we disapprove of their actions, yet wish them to succeed.”

As a filmmaker, Noll understands that films are made not with themes but with images and sounds, so her account of bodily engagement, like her analyses of color dynamics, is pervaded by the recognition that first of all a movie is a concrete experience engaging our senses and our minds. The critic can point to abstract meanings, but we’re also interested in the mechanics underlying those meanings, how movies arouse our appetites for action and emotion.

Two critics attuned to the many levels of a film’s appeals are represented in new collections. There’s now a second edition of Roger Ebert‘s Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert, from the University of Chicago Press. The 2006 original, which contained his personal choice of his strongest reviews and essays through 2005, has been enhanced with new pieces on Roger’s favorite films from the years 2006-2012, the year before his death. Films covered are Pan’s Labyrinth, Juno, The Social Network, A Separation, and Argo, along with shorter notices on many more.

It’s clear that Roger’s abilities were undiminished despite his illness. As ever, he brings his own variety of empathy to the characters and story worlds displayed. His eye stayed sharp:”Del Toro moves between many of these scenes with a moving foreground wipe–an area of darkness, or a wall, or a tree. . .. The technique insists that his two worlds are not intercut, but live in edges of the same frame.” The dozens of pieces in the collection are full of warm, sensitive moments of appreciation. I have updated my introduction to add some further reflections on Roger’s legacy.

While Roger Ebert was starting his career in Chicago with a review of Bonnie and Clyde in 1967, Joseph McBride was at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, writing his own film criticism and working on his still valuable book on Orson Welles. A prodigy, yes. He moved to California the same year Kristin and I came to Wisconsin; we met him once, as I remember, just before he was about to leave. We’re kindred spirits, born sixteen days apart and bound by Boomer Auteurism.

Joe’s most famous screenplay is for Rock ‘n’ Roll High School, but he also scripted many of the AFI tributes. He’s a professional journalist and currently a university professor. But he is at bottom, as he readily admits, a book writer. His biographies of Capra, Spielberg, and Ford have become indispensable, while his memoir and analysis of Welles’ late career (What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?) is just as meticulously researched and intellectually ambitious.

Now Joe has given us a massive collection of his shorter pieces. Two Cheers for Hollywood, its ambivalent title echoing E. M. Forster’s Two Cheers for Democracy, includes a vast panorama of work. Journalist Joe, who has done over 15,000 interviews in his career, gives us a tempting sample here. He records encounters with screenwriters (Polonsky, Michael Wilson, Marguerite Roberts et al.) and directors (from Cukor and Wilder to Bernds, of Three Stooges fame). He talks with Stepin Fetchit in a Madison strip club and Peter O’Toole in the Beverly Wilshire (“his bony white hands and feet protruding from his royal purple robe like the wings of a great pale bird”). Saul Zaentz complains of “pseudo-stars” and Billy Wilder shows Walter Matthau how to rip out a phone cord in two jerks: “Zis is the first one, and the second zis is a ZUMP!” Each interview is prefaced by a thoughtful reflection on Joe’s own evolution as a writer.

Then there are the critical pieces, many of them magnificent. There’s the most detailed defense I’ve ever seen of the Coens, a nuanced investigation of Ford’s attitudes on race, a predictably acute account of Spielberg’s strengths and weaknesses, an appreciation of performance in Fahrenheit 451, a probing of Wild River (Kazan’s most Fordian film, methinks), and much, much more. The book contains 56 essays, all substantial. It runs to over 650 big pages. It lacks neither passion nor precision, just an index.

Another Boomer Auteurist is William Paul. Bill did some film reviewing in his younger days but became an academic like Noll and Joe and me. Currently Professor of Film and Media Studies at Washington University of St. Louis, he has written fine books on Lubitsch’s American films and on the tie between modern horror and modern comedy. What has consumed him in recent years is an in-depth investigation of the history of the movie house. When Movies Were Theater: Architecture, Exhibition, and the Evolution of American Film is the result, and it’s a landmark study.

Another Boomer Auteurist is William Paul. Bill did some film reviewing in his younger days but became an academic like Noll and Joe and me. Currently Professor of Film and Media Studies at Washington University of St. Louis, he has written fine books on Lubitsch’s American films and on the tie between modern horror and modern comedy. What has consumed him in recent years is an in-depth investigation of the history of the movie house. When Movies Were Theater: Architecture, Exhibition, and the Evolution of American Film is the result, and it’s a landmark study.

The broad historical arc moves, as you’d expect, from storefront theaters to picture palaces and then drive-ins and arthouses. But this is no simple account of buildings. Bill argues that the manner of presentation shaped the rise of the feature film, the recurring strategy of roadshows, the demands for double bills, and other factors of film form and industry conduct.

Bill suggests that the 1910s demand for “life-size figures” in film might have been a response to theater size, and he speculates that the move to closer shots in the 1920s might reflect enlarging venues. Makes you wonder if “intensified continuity” of the 1960s and thereafter owes something not only to TV as the ultimate destination of the images but also to the cramped screens of early “twinned” houses, those sticky-floored abominations.

As usually happens when a good historian dives deep, you get surprises. Bill uncovers floor plans with seats facing in the wrong directions, horseshoe-shaped venues, auditoriums packed with pillars, and other peculiarities. One counterintuitive thing that I learned was that screens were rather small for most of film history. A screen for a palace seating a thousand people might be only twenty feet across. Bill’s frames from Footlight Parade and Saboteur show views from the back of a playhouse, and they indicate that often the proscenium area wasn’t filled by the screen, which was cloaked in black masking.

The Hitchcock is of course a studio reconstruction of Radio City Music Hall, but Bill indicates that the proportions are accurate. In all, his When Movies Were Theater joins Douglas Gomery’s Shared Pleasures in showing, in sharp detail, just how varied and diverse American movie exhibition has been.

I would recommend Steven Rybin‘s anthology The Cinema of Hal Hartley: Flirting with Formalism even if I didn’t have a piece in it. For one thing, I too flirt with formalism. Hell, I nearly eloped with it. Second, my study of staging in Simple Men is pretty bare-bones compared to the rich and varied work on display in the other essays in the book. Steve has written widely on American film, both classic and contemporary (Malick, Mann). His introduction to the book ranges across a vast terrain, from models of independent film to debates about “smart cinema.”

I would recommend Steven Rybin‘s anthology The Cinema of Hal Hartley: Flirting with Formalism even if I didn’t have a piece in it. For one thing, I too flirt with formalism. Hell, I nearly eloped with it. Second, my study of staging in Simple Men is pretty bare-bones compared to the rich and varied work on display in the other essays in the book. Steve has written widely on American film, both classic and contemporary (Malick, Mann). His introduction to the book ranges across a vast terrain, from models of independent film to debates about “smart cinema.”

The essays that follow offer agreeably intricate analyses of Hartley as a romantic comedy director, of “small films,” of Parker Posey as a muse, and on the Henry Fool trilogy as centered on the implications of writing. I especially appreciated the way that all the contributors (Mark L. Berrettini, Jason David Scott, Steven Rawle, Sebastian Manley, Daniel Varndell, Fernando Gabriel Pagnoni Berns, Zachary Tavlin, and Jennifer O’Meara) show how Hartley’s authorial obsessions responded to conditions of production, industry pressures, or critical reception. It’s called context, and yields a body of criticism that does honor to a director still not as fully appreciated as he deserves to be.

Another thick context, Wisconsin-revisionist style, is on display in Bradley Schauer‘s Escape Velocity: American Science Fiction Film, 1950-1982. In working on my book on 1940s cinema, I was struck by the absence of today’s dominant genres: fantasy and science fiction. SF books and magazines became widely popular in the period but, apart from cheap serials, the genre had a delayed arrival on movie screens. When it did arrive, Brad explains, it was presented not as classic space opera but something else, what he calls “topical exploitation cinema.”

To escape the pulp associations of Flash Gordon, SF movies traded on current scientific discoveries and headline items like flying saucers. As often happens, it took a marginal player to push a new cycle. Eagle-Lion’s Destination Moon (1950) caught the attention of big studios, which embarked on mid-budget items like When Worlds Collide and The Day the Earth Stood Still (both 1951). Brad traces the cycle’s urge for legitimacy through special effects, more sophisticated narratives, and even appeal to Scripture. These developments were shaped by broader changes in the American film industry, especially concerning budgets and program policy.

To escape the pulp associations of Flash Gordon, SF movies traded on current scientific discoveries and headline items like flying saucers. As often happens, it took a marginal player to push a new cycle. Eagle-Lion’s Destination Moon (1950) caught the attention of big studios, which embarked on mid-budget items like When Worlds Collide and The Day the Earth Stood Still (both 1951). Brad traces the cycle’s urge for legitimacy through special effects, more sophisticated narratives, and even appeal to Scripture. These developments were shaped by broader changes in the American film industry, especially concerning budgets and program policy.

After spelling out this early history, Brad takes us through familiar titles from 2001 to Star Wars: Episode IV–A New Hope, but always fleshing out the story with new information and ideas. He shows that Kubrick gave his film prestige through art-cinema style and storytelling, while Lucas’s film gained traction by treating space-opera formulas with earnestness and respect rather than camp condescension. Brad analyzes important SF films that are often forgotten, like Logan’s Run and Rollerball. His discussion of Alien and Planet of the Apes reminds us that the current incarnations of these franchises have strayed somewhat from their original entries.

Again, the historian unearths surprises. Given the revulsion of today’s intellectuals toward Star Wars, which gets blamed for ushering in the Big Dumb Movie, it’s worth remembering that nearly all the critics praised it. Under the rubric “Fun in Space,” Newsweek‘s reviewer noted: “I loved Star Wars and so will you, unless you’re. . . oh well, I hope you’re not.” That’s sort of the way I feel about these books.

Earlier book-dedicated blog entries are here.

Designing Woman (1957): “There are three pillows stacked on each side of the sofa, and as if by chance they take up the colors of the party: red, turquoise, bluish-purple. . . . The color chord of the party becomes an end in itself, and the composition obtains a playful intrinsic value” (Christine Brinckmann, Color and Empathy, p. 48).