Archive for the 'Books' Category

An auteur, three archives, and the archivist as auteur

City of Sadness (1989).

DB here:

The books have been piling up again, and so I pass along some recommendations. This time the volumes are unusually handsome. Apart from what they say, these publications display how sumptuous a serious film book can be.

Particularly welcome, in light of the touring retrospective of Hou Hsiao-hsien films that began at MoMI on 12 September, is Richard I. Suchenski’s anthology of writings on and by the director. Hou Hsiao-hsien is packed with color illustrations and fully up to the standard of other publications from the Austrian Filmmuseum.

Particularly welcome, in light of the touring retrospective of Hou Hsiao-hsien films that began at MoMI on 12 September, is Richard I. Suchenski’s anthology of writings on and by the director. Hou Hsiao-hsien is packed with color illustrations and fully up to the standard of other publications from the Austrian Filmmuseum.

Some of our top critics and scholars have contributed essays. From Japan comes Hasumi Shigehiko on Flowers of Shanghai; from France, Jean-Michel Frodon on Hou’s collaboration with Chu Tien-wen; from Canada, James Quandt, eloquent as ever on Three Times. American scholars are here too. We have Jean Ma on The Puppetmaster, Abe Mark Nornes on calligraphy and frame space, Kent Jones on time in Hou, and James Udden on Dust in the Wind. Jim is author of the first English-language book on Hou and a contributor to this website. To these essays are added the unique perspectives offered by Taiwanese observers Peggy Chiao on City of Sadness and Wen Tien-hsiang on unmarried women in Hou. A wide-ranging introduction by Richard brings out virtually all the artistic, political, and cultural issues that have been raised by Hou’s body of work.

Unabashedly auteurist—and what’s wrong with that?—the collection adds even more value by including an interview with Hou and Chu, who supply precious information about the work-in-progress The Assassin. There are also statements by three distinguished directors: Olivier Assayas, Jia Zhang-ke, and Koreeda Hirokazu. Koreeda notes: “Life’s details (like eating) should be respected.”

We learn as well about the craft behind the artistry. We get a cascade of information from artistic collaborators, including cinematographers, sound designers, actors and others. For example, Tu Duu-chih, sound expert, says: “What [Hou] wants is a natural form of expression and he always manages the atmosphere to meet his needs. If he shoots a drinking scene, for example, he will select real dishes and alcohol and they must be delicious.” Delicious is a good word for this book too, an absolute necessity for every serious cinephile.

Birthday greetings to Vienna and Brussels

Speaking of the Austrian Filmmuseum, it celebrates its fiftieth anniversary this year. To celebrate, it has issued a heavyweight, unorthodox boxed set, The Austrian Film Museum at Fifty. Director Alexander Horwath has done a monumental job in bringing a great deal of material together, creating not only a history of the Filmmuseum but a real contribution to international film culture.

In volume one, Aufbrechen (Setting Out), Eszter Kondor provides a history of the institution, with emphasis on its emergence the 1960s and 1970s. Volume two pays homage to Béla Balázs with the title Das sichbare Kino (The Visible Cinema). This is a plump anthology of texts, pictures, and documents from the museum’s history. Given the fact that Peter Kubelka was curator for many years, you’re not surprised to find a letter from Michael Snow and an email from Ken Jacobs. But I didn’t expect an interview with Groucho Marx (letter appended) and correspondence from Don Siegel. This volume also includes a complete record of programs at the museum.

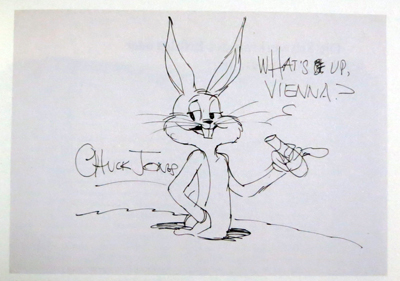

Volume three, Kollection, is a visual treat. It gives us a short history of film in fifty items. The survey includes The Unfinished Letter, a 22mm Edison film ca. 1911-1913, outtakes from Murnau’s Tabu, Morgan Fisher’s site-specific Screening Room (1968), Kurt Kren’s leather jacket, Chuck Jones’ What’s Up, Vienna? (1983), and frames from Norbert Pfaffenbichler’s dizzying Notes on Film 03: Mosaik Mécanique (2007).

The texts in all of the books are in German, but there are so many posters, photos, sketches, diagrams, and storyboards (one by Vertov) that you learn merely by browsing. These volumes are a must for research libraries with a focus on film.

No less idiosyncratic is another anniversary volume, this one from the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, now known as the Cinematek. It was founded seventy-five years ago and, as if by cosmic convergence, it holds 75,000 film titles. But the book, 75000 Films, isn’t a celebration of this particular museum. It’s a book about film archiving in general. As curator Nicola Mazzanti puts it in his introduction:

No less idiosyncratic is another anniversary volume, this one from the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, now known as the Cinematek. It was founded seventy-five years ago and, as if by cosmic convergence, it holds 75,000 film titles. But the book, 75000 Films, isn’t a celebration of this particular museum. It’s a book about film archiving in general. As curator Nicola Mazzanti puts it in his introduction:

Film archiving is already changing and in a few years will be very different from what it is now. New skills, new machines, new people. As no book like this one exists about film archiving we wanted to make sure that at least one is published before the picture changes completely.

What will change? Chiefly, the sheer tactility of the work.

Inspecting a film to check its conditions and its history is all about a physical relation with the material. While winding through a reel of film your fingers run along the edges to feel imperfections and damages. One bends a piece of film to assess its brittleness, caresses a splice to check its resistance. . . .

In other words, it is a precise, careful, dedicated and highly specialized work that often is as tedious as rewinding hundreds and thousand of reels (by hand, as electric motors are often dangerous to the film). An uneventful process until you stumble upon a lost film or a camera negative or perhaps just a beautiful copy in which the colours are perfectly preserved. And the beauty of those images takes your breath away, the thrill of the discovery repays you for all the hours of boring inspections.

To capture both the routine and the exhilaration, Nicola let three photographers document, without constraint, what they saw behind the scenes of the Cinematek. Xavier Harck, Jimmy Kets, and Marie-Françoise Plissart took their cameras into the vaults, the work spaces, the projection rooms, even the loading docks. The images are gorgeous and radiate the touch and heft of reel after reel, can upon can, in profusion that evokes Resnais’ Toute la mémoire du monde.

Along with the photos are three essays about film archives. They are personal reflections on cinematheques and their place in film culture. Dominique Païni writes (in French) about how access to films changed during his years as director of the Cinematheque Francaise. Erich de Kuyper, filmmaker and novelist, reflects in Flemish on guiding the Amsterdam Film Museum and creating the programs there. I contributed a piece in English that tries to fit my personal research work into broader trends of film archiving. My essay is elsewhere on this site.

The age of impresarios

Langlois is the dragon who guards our treasures.

–Jean Cocteau

In spring of 1973 the New York Times announced that a city board had approved the leasing of a building that would house the City Center Cinematheque. This was to be the American counterpart of the Cinémathèque Française, and Henri Langlois was to be its director.

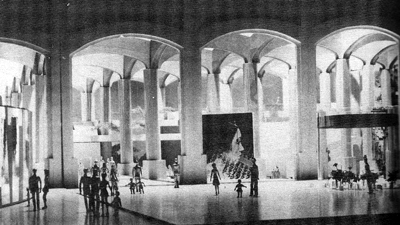

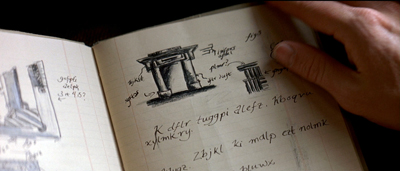

Langlois’ project was as vast and flamboyant as the man himself. An old storage building under the Queensboro Bridge, on First Avenue between 59th and 60th Streets, would be converted into a cathedral of cinema. I. M. Pei would design the new building. (One sketch is above.) There would be three auditoriums, a staff screening room, an exhibition space, a restaurant, a bookstore, and a flower market. Programs would draw upon Langlois’ archive of 60,000 titles, and there would be screenings from morning to midnight, offering as many as fourteen films a day. Langlois predicted that attendance would surpass a million a year.

My own encounters with Langlois, brief though they were, came at just this moment. I needed to see several French silent films for my dissertation work, and in 1972-1973 I wrote to Langlois asking for permission to visit his archive. Thanks to Sallie Blumenthal, we made contact and he gave me permission. In July, during the summer of Watergate, I arrived at the Cinémathèque. An expansive Langlois welcomed me and gave me a tour of the Musée du cinema, which had been somewhat prematurely opened. Jean-Louis Barrault’s costume from Les Enfants du Paradis was draped on a coat hanger nailed to a wall. During my two months in Paris, thanks to Langlois and Mary Meerson, I saw several rare films on Marie Epstein’s viewing table.

I have sometimes wondered if my stay there was an accident of timing. Perhaps as a young American I benefited from Langlois’ high hopes for his transatlantic alliance. Pressed by money problems in Paris, he could imagine that the American branch of the Cinémathèque would vindicate his vision of a motion picture museum without walls: films circulating everywhere, films shown all the time, no film too minor to merit attention. Had the City Center venue come to fruition, it would have overshadowed the Museum of Modern Art, Manhattan’s temple of cinema history. But the project collapsed fairly soon. It required private financing, and during the recession and the oil crisis money was hard to come by.

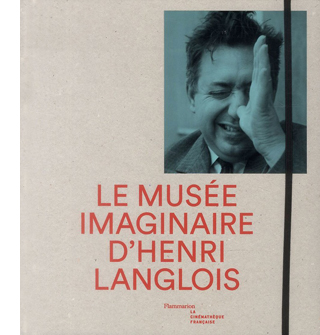

Langlois’ American adventure is just one episode in the tapestry presented in another archive-related anniversary volume: Le Musée imaginaire d’Henri Langlois. Edited by Dominique Païni, this de luxe production accompanied the Cinémathèque’s massive exposition from April to August. If Langlois were still living, he’d be 100 this year, and the sumptuousness of this catalogue is in part a testimony to what he accomplished. He helped make cinema equal to the other arts in cultural significance. But the enterprise is not too serious: Païni has made the volume’s emblem the famous shot, taken by an unknown hand, of Langlois in the kiss-my-ass salute.

The menu is familiar. There are informative essays by various hands, interspersed with illustrations and documents. But the execution is extraordinary. Reminiscent of 1920s publications, on rough paper and with decentered blocks of type, this square volume seduces you into sustained browsing. Moreover, it contains reproductions of artworks related to Langlois and his institution. We have works by Beuys, Chagall, Duchamp, Fischinger, Léger, Matisse, Miró, Picabia, Richter, Severini, and Survage—all connected, somehow to Langlois and cinema. There are frames from Le Métro, a 1934 film by Langlois and Franju., There are guest-book signatures, catalogue covers, correspondence, and much more.

The catalogue of the exposition is accompanied by a slender but no less ingratiating biographical chronology, festooned with still more images. Mais qui est ce Monsieur Langlois? opens with a striking portrait by Henri Cartier-Bresson and ends with the telegram sent by Jean Renoir after Langlois’ death in 1977. “We have lost our guide, and now we feel alone in the forest.”

I met Langlois in the days of rivalry among archives, a good deal of it triggered by him. If you were welcomed to Archive X, and word got to Archive Y, that venue would shun you. Surveying these books, I was struck by their quiet assumption that archives must collaborate on projects and share their treasures. After Langlois, archiving became more cooperative, more routinized, more professional, and–Langlois and his allies would say–more boring. We may not need dragons now. Perhaps, though, we had to go through the turmoil of the Age of Impresarios in order to appreciate why collecting films was so important.

For some ideas on Hou’s visual style, see Chapter 5 of my Figures Traced in Light, this entry, and a discussion of the early films on this site.

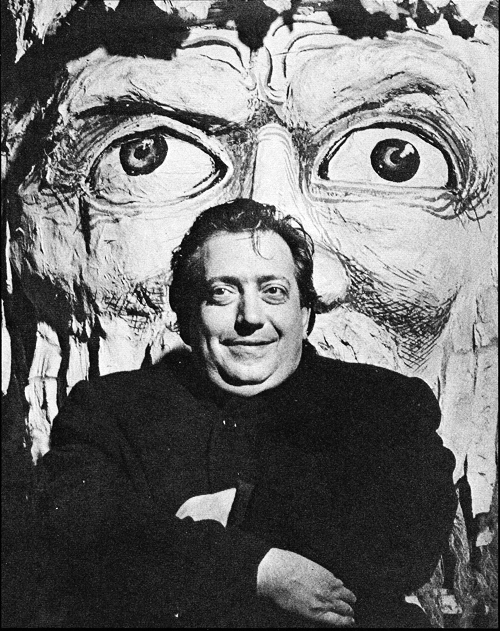

Henri Langlois. Photo by Pierre Boulat.

Somewhere it’s always GROUNDHOG DAY

Phil earns his groundhog halo.

Kristin here–

Back in 1999, my book Storytelling in the New Hollywood (Harvard University Press) was about to be published. It was an attempt to suggest that, contrary to the talk of “post-classical” or “post-Hollywood” norms having taken over American filmmaking, the most important classical principles that had been at work since the 1910s were still going strong.

I outlined those principles in the opening chapter, discussing character goals, deadlines, dialogue hooks, unity, and the like. I also argued that, based on my analysis of many films from the 1910s to the 1990s, the vast majority of features followed a structure involving four large-scale parts, or acts–not three, as the popular Syd Field model would have it.

To do that, I analyzed the techniques of ten films usually considered to be models of unified, sophisticated narrative structure: Tootsie, Back to the Future, The Silence of the Lambs, Groundhog Day, Desperately Seeking Susan, Amadeus, The Hunt for Red October, Parenthood, Alien, and Hannah and Her Sisters.

The book was not intended to be a screenplay manual as such, though I know it has been used in some classes and by some aspiring screenwriters.

Ordinarily the press would have asked me to name some prominent film scholars who could be asked to write blurbs for the cover. It occurred to me, though, that it might be better in this case to take each chapter and send it to its director and to its main screenwriter and ask them for blurbs instead.

That turned out to work pretty well. Several didn’t answer, and other answered too late to be included. I ended up with three blurbs of which I am very proud, from Ted Tally for The Silence of the Lambs, Susan Seidelman for Desperately Seeking Susan, and from Harold Ramis for Groundhog Day.

Ramis’ recent death prompted me to dig out that old file. He had written back to my editor not with a sentence or two to use as a blurb, but with a page-and-a-half letter on the subject; it included a blurb down toward the bottom. It’s a letter that reflects how kind and smart Ramis was, and how much he had thought about writing and narrative–even though the process of writing screenplays was probably largely an intuitive one. It shows that he knew something about academic film studies, even if he had some “quibbles” with them. I certainly never meant to suggest that everything I pointed out in the films I analyzed was intended by the director and/or screenwriter. I would say that everything I pointed out was a result of their skill and experience. Even when something happens by accident during filming, someone has to decide whether or not to keep it in.

Rather than just sticking the letter back in the file, I thought I would share it with you. Having a little more of Ramis available can’t be a bad thing.

Dear Lindsay,

Thanks for sending the chapters of Kristin Thompson’s book Storytelling in the New Hollywood and please convey my thanks to Ms. Thompson for including Groundhog Day among the “modern classics.” My only quibble with scholarly film analysis is the occasional tendency to read more significance into certain details than was actually intended, or to think that certain accidents of production, on-set discoveries, or improvisational dialogues were planned and scripted. I realize, from a Deconstructionist point of view, it hardly matters what I think anyway, so let me set aside my minor quibbles and congratulate Ms. Thompson on her new book. If you would, please pass this letter along to her.

I am not a student of screenwriting so I’m afraid I can’t comment intelligently on Ms. Thompson’s theoretical model. Certainly, the fact that most movies are about two hours long will determine to a large extent the length of the set-up, the placement of the crisis, the climax, and the denouement, but rather than look at films in terms of “acts,” I prefer to think in terms of “actions,” as if the narrative line were a string of pearls, dramatically linked, each taking the audience forward to the next point. If any particular action doesn’t advance the plot or contain some new information, it doesn’t belong in the narrative. As a writer I generally proceed more intuitively than structurally. As Ms. Thompson suggests, I suspect that most of us have simply absorbed the classical film structure during our formative years as members of the audience.

When I was hired to write my first Hollywood screenplay, Animal House, the producer handed my collaborators and I paperback copies of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and said, “This is what a good screenplay looks like. Just do that.” More than twenty years later, my only useful conclusion about structure is that nothing will work if you don’t have interesting characters and a good story to tell. One can argue for or against the three-action structure, but, whether or not there are consistent rules about the :well-made” screenplay, it’s already true that there are more well-constructed, formulaic screenplays than there are good ones. Also, one must always keep in mind that Hollywood films are almost invariably rewritten by additional (though not always credits) writers. One writer may be thought of as strong on structure, good for a solid first draft, another may be known for his dialogue, others for punching up action or comedy. Also , the Hollywood writer is always responding to script notes from studio executives, story departments, his producers, the director, and from his principal actors. In this convoluted and often tortured process, it’s sometimes impossible to attribute the final screenplay to the calculated intentions of one writer or team, and it’s often left up to a panel of Writers Guild arbiters to determine screen credit.

I didn’t intend to write such an inflated letter but there’s a lot to say on the subject and I have a considerable amount of experience.

If it’s useful to you, you may quote me as saying that Ms. Thompson’s insightful analysis of Groundhog Day and of the screenwriting process in general should be fascinating to both writers and audience alike. More thoughtful writing and more discerning audiences can’t help but lead to better movies, and this informative and provocative book is a step in that direction.

Best of luck on the publication of Storytelling in the New Hollywood and please feel free to contact me if you need any further comments.

Sincerely,

Harold Ramis

Harold Ramis as Allan “Crazy Legs” Hirschman (SCTV, “Indecent Exposure,” 1982).

Nothing, if not critical

The Woman in the Window (1944).

O, gentle lady, do not put me to’t,/ For I am nothing, if not critical.

Iago, Othello

DB here:

Movie aficionados seem endlessly interested in film criticism—not just in what a writer says about a film, but in the very idea of criticism. I’ve suggested in a recent entry some of the historical reasons for this: the rise of the celebrity reviewer in the 1960s, the surge in interest in foreign and alternative cinemas, the emergence of filmic experiments, from Persona to Memento, that seemed to demand discussion.

With the internet, you can’t turn around without bumping into a film review. Aggregate sites like Rotten Tomatoes and Metacritic get tens of millions of hits a month. Of course many people are just checking on the range of opinions of a specific release, but I get a sense that many readers are more or less addicted to critical buzz as such. Connoisseurs of sentiment and snark, they still follow favorite reviewers just as we did in the 1960s, and they enjoy reading a critic they don’t agree with because she or he is an enticing writer.

In one corner of my workroom a steadily growing pile of books is no less a tribute to the flourishing of film criticism. Yes, books. I’m a committed Netizen (I’d better be, after three e-books, several web essays and videos, and over 610 blog entries). And for certain purposes, such as word search, I prefer digital versions of texts. But nothing beats a book for reading anywhere you happen to be, thumbing back to check a point, marking up margins with invective, and throwing across a room when you’ve decided the author is a dunce.

Here, though, are some books that won’t become missiles.

Revaluation

One consequence of the 1960s cult of the movie critic was a new genre of book—the anthology of a writer’s reviews, think pieces, and long-form essays, perhaps spiced by an interview or two. Call it a predecessor of a website if you must, but such books were tempting packages to cinephiles who wanted their fix in big gulps, not weekly doses. Then we eagerly read through Agee on Film, Dwight Macdonald on Movies, Kael’s I Lost It at the Movies, and many other collections. Some of these are now classics, most are forgotten, but the format still has life in it. Roger Ebert, exceptional in all respects, kept it going for years and crowned it with his Great Movies series. The format passed to academic presses like Wesleyan with Kent Jones’ Physical Evidence (2007) and Chicago with Dave Kehr’s When Movies Mattered (2011).

Like me, James Naremore is a creature of the 1960s, but with his typical discretion he has waited forty years to bring together a collection. Jim’s 1973 Filmguide to Psycho introduced me to his elegant thinking about movies. Since then he has written about a great many subjects, always with wit, steady vision, and deep and unostentatious learning. Now we have An Invention without a Future: Essays on Cinema (University of California Press).

Every essay here is a polished gift from a master of the literary essay. The book’s first section considers classic topics like adaptation, authorship, and acting. It includes a sharp discussion of the rhetorical dimension of both filmic creation and critical commentary. In the second section we see Naremore the close reader, turning to the classic Hollywood cinema he has done so much to illuminate. He considers Hawks, Hitchcock, Welles, Huston, Minnelli, and Kubrick—the subjects of earlier writing he’s done, but now refocused through new lenses. One recurring question is: Does cinema, either as a physical medium or a public spectacle or a humanistic art have a future? Although the book’s compass swings constantly to the 1940s through the 1960s, Jim is fully up to date, writing with sensitivity on Shirin, Uncle Boonmee, and Mysteries of Lisbon.

Every essay here is a polished gift from a master of the literary essay. The book’s first section considers classic topics like adaptation, authorship, and acting. It includes a sharp discussion of the rhetorical dimension of both filmic creation and critical commentary. In the second section we see Naremore the close reader, turning to the classic Hollywood cinema he has done so much to illuminate. He considers Hawks, Hitchcock, Welles, Huston, Minnelli, and Kubrick—the subjects of earlier writing he’s done, but now refocused through new lenses. One recurring question is: Does cinema, either as a physical medium or a public spectacle or a humanistic art have a future? Although the book’s compass swings constantly to the 1940s through the 1960s, Jim is fully up to date, writing with sensitivity on Shirin, Uncle Boonmee, and Mysteries of Lisbon.

The latter pieces were among Jim’s efforts at real-time film reviewing at Film Quarterly. Perhaps the sharpest edge of the book comes in the section housing them, called “In Defense of Criticism.” Jim, I think, considers criticism as, say, Lionel Trilling or Edmund Wilson considered it. Endowed with a tolerant, generous mind, the critic uses all the resources of culture—philosophical and moral ideas, social forces, artistic traditions—to illuminate the unique identity of the artwork.

More deeply, the critic expects the encounter with the artwork to challenge and change us. This to me is one difference between the reviewer and the critic. The reviewer expects the film to live up to his or her solidly entrenched point of view. The critic is open to being shaken, taught, and even transformed by the film. The reviewer projects confidence, the critic displays curiosity.

This ambitious conception of criticism is at risk today from two forces. There is the sheer blather of pop journalism and the Internet, which have pushed film culture from criticism to comments to chat to chatter. At the other end, some professors are allied against film as an art.

Today the humanities are in danger of losing their soul. Academic film studies has tended to focus on formal systems, industrial history, fandom, and identity politics—essential topics without which good criticism can’t be written, but topics that don’t engage directly with questions of art and artists.

Admitting that a certain detachment is valuable for research purposes, Naremore thinks that academics have become somewhat too clinical. Part of his book’s purpose is to draw their attention back to the intellectuals who flourished outside the academy, and for whom quality was worth arguing about.

I nevertheless think that evaluative criticism needs to be encouraged more, and I miss the days before the full-scale development of film studies, when film was made exciting and relevant by virtue of critical writing and debates over value.

So the last section consists of thoughtful essays on James Agee, Manny Farber, Andrew Sarris, and Jonathan Rosenbaum—those who “had the greatest influence on the development of my taste.”

For my $.02, I’d just add that appraisals of quality shape a lot of academic writing, even in the Cult Studs vein. Showing that a film is racist or classist is surely an exercise in evaluation, employing moral or political criteria. Showing that fans of Twilight aren’t dumb no-hopers often springs from the researcher’s own esteem for the franchise. (Remember one of The Blog’s mottos: We are all nerds now.)

In effect, I think, Jim is pointing out that in a lot of film studies evaluation isn’t framed in specifically artistic terms. On that I’d certainly agree. Jim opens a new conversation by asking academics to look beyond their specializations and learn how the best arts journalists argue about quality. Seriously thought-through yet accessible to all, An Invention without a Future is a bracing, quietly subversive book.

Auteurs: From the ridiculous to the sublime

Jim would find signs of hope in two books dedicated to major directors.

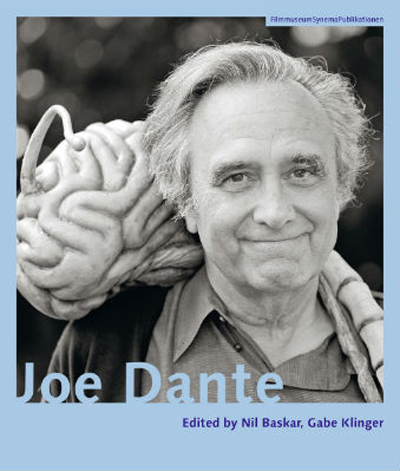

Nil Baskar and Gabe Klinger’s Joe Dante, a collection from the enterprising SYNEMA series at the Austrian Film Museum. Dante is just the sort of auteur that cinephiles prize. Working on the fringes of the system in despised genres, he’s a Movie Brat who loves B cinema, noir, and crazy comedy. This thick, square book contains virtually everything you’d ever want to know about the man who could be seen as Spielberg’s demented, funnier alter ego. Dante’s kiddie adventure stories and teen terror pix have celebrated and parodied Americans’ feverish love of war, big business, junk food, and lunatic media.

From The Movie Orgy through Looney Tunes: Back in Action to The Hole (still not released in 3D in the US, as far as I know), Dante has been a paradigmatic case of the termite artist praised by Manny Farber. In this collection John Sayles recalls that for The Howling he and Dante agreed they would center on characters who knew horror-movie conventions and wouldn’t make the typical fatal mistakes. Bill Krohn, J. Hoberman, Christoph Huber, and Michael Almereyda are among the admirers assembled here, and their spirit of amiable, film-geek homage is infectious. There’s also a long interview with Klinger, a detailed chronology, and a filmography zestfully annotated by Howard Prouty.

From The Movie Orgy through Looney Tunes: Back in Action to The Hole (still not released in 3D in the US, as far as I know), Dante has been a paradigmatic case of the termite artist praised by Manny Farber. In this collection John Sayles recalls that for The Howling he and Dante agreed they would center on characters who knew horror-movie conventions and wouldn’t make the typical fatal mistakes. Bill Krohn, J. Hoberman, Christoph Huber, and Michael Almereyda are among the admirers assembled here, and their spirit of amiable, film-geek homage is infectious. There’s also a long interview with Klinger, a detailed chronology, and a filmography zestfully annotated by Howard Prouty.

Dante’s opposite number is Béla Tarr, whose films run the gamut from glum to morose, but they’re no less exhilarating. They find their ideal explication in András Bálint Kovács’ The Cinema of Béla Tarr: The Circle Closes. Kovács scrutinizes all the films, some little-known outside Hungary, and produces careful analyses that balance thematic interpretation with precise examinations of style. As a friend of Tarr’s, András is in a unique position to take us into this filmmaker’s grimy, splendid world.

Tarr, Kovács suggests, asks his audience to accept the illusions shaping the narrative world. Yet his structure and technique in the end yield a clearer view of the underlying forces than the characters can achieve—often, forces driven by conspiracy or betrayal. Accordingly, Tarr’s narratives tend to be cyclical, even when the story situation is unchanging, and his camera movements often trace a circular path. Many readers will particularly welcome Andras’ exciting account of Sátántangó, Tarr’s most demanding film. Based on a novel with an intricately circular structure, the film finds its own means to suggest a story swallowing its own tail. Most film books nowadays have pretty good frame illustrations, but these are well-sized to illustrate some of Tarr’s fine points of staging. In all, this book is likely the definitive study of Tarr’s art.

Museum pieces

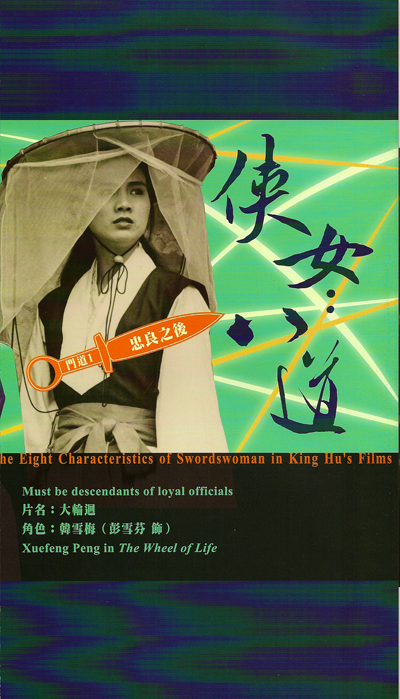

There’s another way to make the case for an auteur’s value: produce a dazzling book that pays tribute with gorgeous illustrations and informed critical commentary. This has been done by Taipei’s Museum of Contemporary Art in its catalogue King Hu: The Renaissance Man.

The 2012 exhibition it preserves in its pages went beyond the usual regimen of talks and panel discussions. There were children’s events and in-person painting of film billboards. In one display, you could watch Tsui Hark’s calligraphy form a tribute to his master (“The integrity of swordsmanship remains as the spirited rain….”). An installation tableau by Tim Yip presents a modern woman watching King Hu TV appearances while texting, her vacant mind suspended between two spaces.

The 2012 exhibition it preserves in its pages went beyond the usual regimen of talks and panel discussions. There were children’s events and in-person painting of film billboards. In one display, you could watch Tsui Hark’s calligraphy form a tribute to his master (“The integrity of swordsmanship remains as the spirited rain….”). An installation tableau by Tim Yip presents a modern woman watching King Hu TV appearances while texting, her vacant mind suspended between two spaces.

Open the catalogue and you’re greeted by a large gatefold that sums up King Hu’s career. Thereafter, articles like Edmond Wong’s study of King Hu’s archetypes (derived from legend and theatre) supply the academic ballast, while images of the gallery displays fill up page after page. There are photo essays devoted to each of the films, as well as more gatefolds, illustrating themes such as “The Eight Characteristics of Inns in King Hu’s Films.” Just the hundred pages of King Hu documents—stills, portraits and self-portraits, along with caricatures of Bill Clinton and Princess Di—would be worth our attention. In all, this is the sort of museum show every cinephile dreams of visiting.

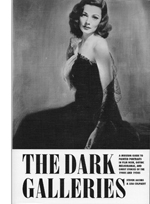

Art historian Steven Jacobs, author of The Wrong House, has collaborated with Lisa Colpaert to produce a dream of another sort. Their book invites you into an imaginary exhibition.

Visualize a museum containing all the paintings you find in films of the 1940s and 1950s. Now assume that some diligent scholar has sniffed out the provenance of all of them and provided stylistic and thematic commentary. And now assume that the research is presented as a guide to this virtual museum, using all the paraphernalia of art-historical commentary.

Confused? Here’s the opening of one entry:

[III.9] Portrait of Lady Caroline de Winter

(Unknown Artist, late 18th Century)

This full-length portrait represents Lady Caroline de Winter (1760-1808). The carefully rendered white dress, the column and curtains, and the vista of the landscape are unmistakably reminiscent of the portraits by Thomas Gainsborough, for instance his often-reproduced The Honourable Mrs. Graham (1775-1777). The landscape with trees probably stands for Manderley, the de Winter family estate on the Cornwall coast. For more than a century, the portrait was hanging in a long corridor in Manderley’s east wing, which was decorated with ancestral de Winter portraits. In the 1930s, the portrait played an important part in the life of one of Lady Caroline’s descendants, Maxim de Winter (Laurence Olivier). Maxim’s first wife Rebecca died in mysterious circumstances and once had a copy made of the white dress on the occasion of a masquerade ball at Manderley. . . .

This straight-faced experiment in creative criticism is called The Dark Galleries: A Museum Guide to Painted Portraits in Film Noir, Gothic Melodramas, and Ghost Stories of the 1940s and 1950s. All the conventions are there: the scene-setting introduction, the iconographic interpretations (“crimes and clues,” “paintings concealing safes”), and an exhibition guide that takes you from room to room, from Dying Portraits to Ghosts to Modern Portraits and more. They track the ways in which paintings in movies have altered time, refashioned faces, and, if the painting is disturbingly “modern,” signified madness and criminality. As zealous researchers, Steven and Lisa have done what they could to trace the provenance of the actual artifacts too, and they’ve discovered a large number of commercial artists hired by the studios.

This straight-faced experiment in creative criticism is called The Dark Galleries: A Museum Guide to Painted Portraits in Film Noir, Gothic Melodramas, and Ghost Stories of the 1940s and 1950s. All the conventions are there: the scene-setting introduction, the iconographic interpretations (“crimes and clues,” “paintings concealing safes”), and an exhibition guide that takes you from room to room, from Dying Portraits to Ghosts to Modern Portraits and more. They track the ways in which paintings in movies have altered time, refashioned faces, and, if the painting is disturbingly “modern,” signified madness and criminality. As zealous researchers, Steven and Lisa have done what they could to trace the provenance of the actual artifacts too, and they’ve discovered a large number of commercial artists hired by the studios.

A few years back at our summer film school, Steven impressed me when he identified the famously puzzling cubist still life in Suspicion as Picasso’s Pitcher and Bowl of Fruit (1931). The ultimate result of his and Lisa’s efforts is at once charming and deeply serious, enlightening us about a major motif in Hollywood’s “dark cinema.” It’s an extraordinary accomplishment, and an ideal gift for the patriarch, matriarch, exotic woman, or mystery man in your life.

Thanks to Lin Wenchi for giving me the King Hu catalogue. I’m unable to find an online source for this book, but when I do I will note it here. In the meantime, the sponsoring museum produced several videos for the exhibition. YouTube supplies a playlist of them. Our entries on this great director are here. I discuss his work in more detail in the books Planet Hong Kong and Poetics of Cinema.

For more exercises in creative criticism, visit Hilde D’haeyere’s website on silent comedy.

For more thoughts on film criticism on this blog, go here and here and here. A series on major American film critics of the 1940s starts here.

I record Joe Dante’s visit to Madison here and wrote about Béla Tarr’s films in these entries.

F for Fake (1972).

Our new e-book on Christopher Nolan!

DB here:

Earlier I’ve described our site as a series of experiments in para-academic writing—a strategy for getting our ideas and research to film enthusiasts both inside and outside educational institutions. Once we had created the site and mounted essays and blog entries, we pushed on to other possibilities.

Could we, we wondered, post published books that are out of print, making them free for anyone with access to the Web? Yes and yes.

Could we create a print book out of blog entries? Thanks to the University of Chicago Press, we did.

Could we supplement our textbook Film Art with extracts-plus-commentary from classic films? Thanks to the Criterion Collection, it proved possible. (Go here for a sample.)

Could I post as an e-book a revised version of a published book, with expanded text and color stills? You bet!

Could I post a new e-book based on blog entries? Done.

Could we post our own video essays? Check and check.

How about lectures in video form? Yup, yup.

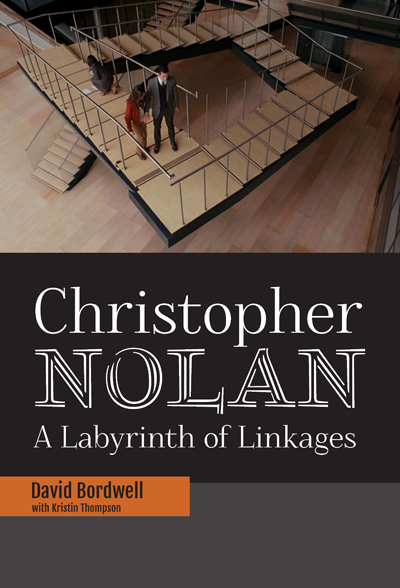

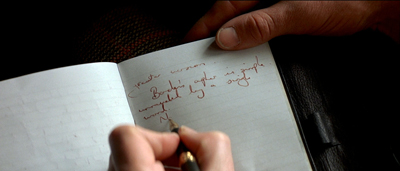

Today we launch another experiment. Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages is offered to you as an e-book. It revises, reorganizes, and expands on several earlier posts. What’s the new wrinkle? For the first time we offer film clips “baked into” the text. A version without extracts is also available. The cost for either one is $1.99.

You can acquire either here, along with more information. What follows provides a little background on the project.

Nolan contendere

Is Christopher Nolan a good filmmaker? A bad one? Good on some dimensions, bad on others? What about the faults and virtues of individual films?

These are questions people consider typical of film criticism—questions turning on evaluation. Then there are questions of personal taste. Even if his films are good, do you dislike them? Even if they’re bad, do you enjoy them? Most people don’t distinguish between evaluation and taste, but I’ve argued before that this is an important distinction.

Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages grants that along certain dimensions Nolan’s films can be faulted. By some criteria, his technique occasionally falters. Along other dimensions, the work is valuable. But the primary concern of the book isn’t to evaluate Nolan. Kristin and I want to analyze some ways in which his narratives have been innovative.

Innovation isn’t inherently a good thing, of course, but we think that Nolan has fruitfully explored some fresh options in cinematic storytelling. Contrary to common opinion, we don’t think that the Dark Knight trilogy is a significant part of this tendency. We concentrate on Following, Memento, Insomnia, The Prestige, and especially Inception. We see in these films a consistent inquiry into how multiple time frames and embedded plotlines can be orchestrated in fresh and engaging ways.

The key problem is comprehensible complexity: How do you build more elaborate structures and still not lose your audience? How do you design a labyrinth that contains enough linkages to guide your viewer toward a unified experience? This is a problem that confronts any filmmaker who tries for ambitious storytelling within the tradition of mainstream American cinema.

So if one of your criteria for a good film is adventurous novelty, then there is a case to be made for Nolan. But maybe you don’t accept that criterion, or you resist the claim that he’s doing something intelligent with classical plot structures, or maybe his work just isn’t to your liking. Nonetheless, we hope that our analyses will shed light on his films—and more generally, on other films.

One of the goals of all our research, online and off, is to trace out broad tendencies. We’re interested in disclosing creative options that are available to filmmakers working in different traditions and at different points in film history. Other directors or screenwriters can push Nolan’s experiments in other directions. And we can study all these options and pathways while suspending evaluation and personal taste.

Old rules, and new

Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages sticks to some of the rules I outlined with respect to Pandora’s Digital Box: Films, Files, and the Future of Movies.

The original blog entries aren’t taken down. All the original blog entries will remain available online. To see them, click on the Nolan category on the right.

The book isn’t simply a blog sandwich. One reason I created this book was to revise and reorganize the somewhat diffuse blog posts into something tighter, with a smoother flow of ideas.

The book has substantial new material. Some points in the original posts are expanded, while we add some fresh ideas about Nolan’s significance.

It isn’t an academic book. It’s written in the conversational style of our blogs. Nonetheless, the text and a reference section in the back provide links to documents, interviews, sources, and sites of interest.

The book isn’t free… Again, I’ve had to pay for design and work on the video clips. So my hope is to recoup my expenses and even pay myself something for my effort.

…but it’s very, very cheap. Planet Hong Kong 2.0 runs $15, which I think is a fair price given the cost of designing a long book with hundreds of color pictures. Pandora is a lot simpler and has only a few stills, so it costs $3.99. The Nolan book, quite a bit shorter than Pandora but with many stills and several video extracts, is priced at $1.99.

And there will be video. One version of the book contains six short extracts from films that are analyzed. These are “baked in.” That is, you don’t have to be online to watch them.

Tech talk

So now, some specifics. These are also reviewed on the purchase page.

We offer a vanilla version of Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages that is a pdf file of 10 MB. It contains lots of stills but no clips. It will display well on any computer or tablet. It costs $1.99.

The audiovisual version of the book is a much fatter pdf file, nearly 300 MB. That one will take longer to download, of course, but it will enable you to play the clips anywhere, whether you’re online or not. It too costs $1.99.

All the clips play smoothly on laptops and desktops, whether PC or Mac. As far as we know, Android-based tablets will run the clips organically. Still, some operating systems on some devices may not natively display the videos. Most notably, the Adobe PDF Reader on the iPad will not run the clips. But there is at least one iOS-friendly application available, PDF Expert, that will play the clips. Probably other apps exist or will be developed. You may want to experiment for best results.

Payment procedure is via PayPal, funneled through PayHip. PayHip enables us to put a big e-book file on the Cloud. When you make your purchase, you will be directed back to the PayHip site to download the book. An email will also be sent to the address you provided, with a download link.

Once more, you can go here to order the book. On the same page you can examine the Table of Contents.

As I said back in 2012 when we introduced Pandora: If you decide to buy the book, we thank you. And again we quote Jack Ryan from the end of The Hunt for Red October: Welcome to the new world.

Thanks to our Web tsarina Meg Hamel, who did her usual superb job turning the Nolan blogs into this little book, and who has set up the payment process to be quick and easy. Thanks as well to Erik Gunneson for his work preparing the clips for our analyses.

All illustrations in this entry from The Prestige.