Archive for the 'Comic strips and cartoons' Category

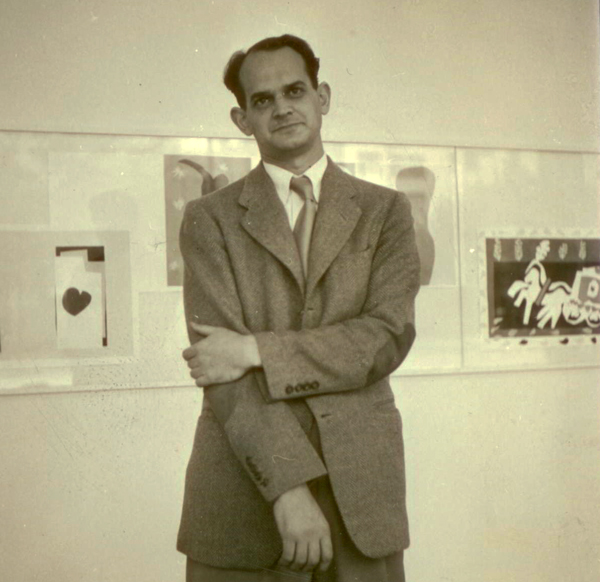

Manny Farber 1: Color commentary

Manny Farber, undated photo. Courtesy of Patricia Patterson.

The original entry at this URL, published 17 March 2014, has been removed. Revised and expanded, it forms a chapter in the book The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture, to be published by the University of Chicago Press in spring 2016.

You can find more information on the book here and here.

I explain the development of the book in this entry.

Thank you for your interest!

The Maestro of Chagrin Falls

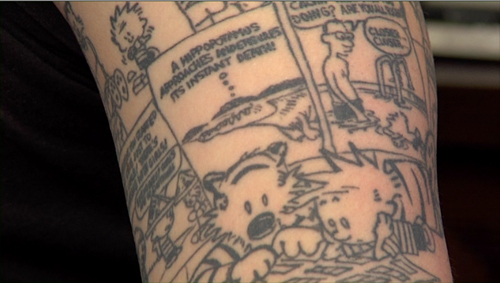

A fan’s tattoo, from Dear Mr. Watterson (2013).

DB here:

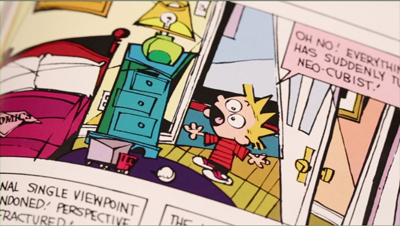

Bill Watterson, creator of Calvin and Hobbes, was probably the best cartoon draftsman since Carl Barks and Walt Kelly. His versatile line could be thick or thin, fluent or jagged. His coloring was rich, his layout experimental in the Herriman vein. His energetic picture stories provided zany humor and an unsentimental look at childhood imagination.

If Schulz treated kids as miniature adults, complete with obsessions and neuroses, Watterson saw Calvin as an adolescent in a child’s body, a rebellious teenager-to-be surrounded by adversaries and fools. Schulz’s Peanuts kids suffer in thin, wriggly lines, but Calvin’s mood swings from rage to rapture are rendered by manic exaggeration in the classic cartoon tradition. Meanwhile Hobbes, contrary to his name, exercises a gentling effect, becoming a tolerant Superego to Calvin’s Id.

Watterson was the Pynchon of cartoondom. His studio in Chagrin Falls, Ohio yielded a solitude rare for a publishing celebrity. He almost never appeared in public and seldom answered mail. In one of his rare public gestures, he criticized syndicate power, the tired old strips put on life support, and the scramble for licensing deals. Accordingly, he permitted no merchandising beyond book collections. Any Calvin and Hobbes toys or T-shirts or decals you see around you are DIY handicraft. After ten years Watterson simply halted the strip, an abnegation that drove his millions of admirers to despair. And he has remained reclusive.

Dear Mr. Watterson, which won a Golden Badger award at our Wisconsin Film Festival, sprang from Joel Schroeder’s fondness for the strip. He realized early on that interviewing Watterson wasn’t in the cards. So he set out to find ordinary readers who would testify to their love for Watterson’s creation. He found plenty of eloquent ones, but the movie is no mere fanboy indulgence. Schroeder’s travels took him to many of today’s top cartoonists, from Berkeley Breathed to Stephan Pastis, as well as critics and syndicate executives.

By outlining the shape of Watterson’s achievement in comics history, Dear Mr. Watterson mutes its admiration with regret, and not merely because Watterson quit at the height of his popularity. The film shows that, as one interviewee puts it, Calvin and Hobbes is very likely the last great comic strip.

Why? The conditions of publishing have a lot to do with it. As newspapers got thinner and smaller, the space allotted to comics shrank. Complex compositions and spacious storytelling became difficult in the slots allotted to Sunday strips, while the daily panel formats were minuscule. Only the sketchiest drawing survives the reduction.

The squeeze was starting in Schulz’s day: Peanuts was the beginning of the “minimalist” look of Cathy and Fox Trot. Watterson’s bold drawing style and appetite for scale posed problems for publishing. Ironically, as Schroeder pointed out in his Q & A, the sort of freedom and flexibility Watterson sought would become available a decade later on the Net.

Something else suffocated comics creativity. Just as tentpole films need an array of ancillaries, a successful cartoon demands the womb-to-tomb merchandising that Watterson foreswore. Children need to be hooked on the franchise before they can read. Garfield clothes and toys introduce infants to a pudgy beast that will stalk them throughout their lives, on lunchboxes and calendars and mugs and mousepads and refrigerator magnets and TV shows and “Is it Friday Yet?” placards for office cubicles. Watterson realized, I think, that being surrounded forever by leering images of cute creatures was one version of Hell.

Schroeder, a graduate of UW—Madison, has made a smart, touching movie. It deserves wide circulation and even, I should say, a PBS airing. It’s at once a tribute to a fine artist, a probe into comics history, and a revelation of how integrity can be maintained in the era of Monetization. Turning down hundreds of millions of dollars, Watterson in effect said something that almost no one imagines possible today: I don’t need that much money.

One observer comments that when Calvin and Hobbes ceased, many critics expected its fan base to dwindle, because it wouldn’t be maintained by all the spinoffs. Instead, parents pass down their Watterson paperbacks as family heirlooms. Fans have the lavish three-volume compendium of the strips, which is selling briskly on Amazon, while school libraries are replenishing their holdings of the slim anthologies. Our children are following the adventures of the hyperkinetic brat and his imaginary tiger in the best way: By reading books.

P.S. 2 May: Chris Blunk of Through a Glass Productions writes this followup:

Coincidentally, this past Sunday I met John Glynn, who works at Andrews/McMeel promoting their properties to Hollywood (such as Garfield and Over the Hedge). He was at the Free State Film Festival in Lawrence, Kansas where he showed the Sundance-boosted Small Apartments, also based on an Andrews/McMeel property. He was the first person I’d ever met who has any kind of semi-regular contact with Watterson. Though Watterson retains nearly all ancillary rights to his characters, A/M-Universal consults him on book printings, electronic distribution, etc.

While there were several tidbits that thrilled a fan like me, one item he mentioned particularly pertained to your article. He claimed that traffic at the Universal comics website (www.gocomics.com) is by and large driven by the Calvin and Hobbes classic – i.e. rerun – strips. The majority of visitors to all other comics on the site – including popular current strips like Get Fuzzy, Pearls Before Swine, Dilbert, etc, – arrive through Calvin and Hobbes.

So in addition to being propagated through handed-down book collections, as you pointed out, Calvin has managed to attract new fans and dominate comics circulation even in the new frontier of the web that grew into being long after Watterson’s retirement. And this with no new strips published in the past 20 years.

He told a couple other anecdotes that were similarly surprising. Such as a time in the early 90s when Spielberg was involved in some animation projects (Tiny Toon Adventures, Family Dog, Animaniacs, etc) and made inquiries about the rights to Calvin and Hobbes. According to Glynn, Watterson turned down a direct phone call with Spielberg himself reasoning they had nothing to discuss.

Thanks to Chris for his thoughts and information, and for reading our blog.

P.P.S. 16 July 2013: Gravitas Ventures announces that it will be releasing Dear Mr. Watterson on theatrical and VOD in November.

Dear Mr. Watterson.

Make mine music, not to mention pictures

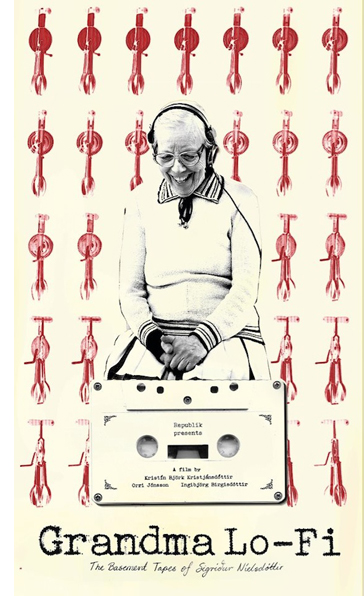

Collage by Sigrídur Níelsdóttir.

DB here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival has had strong commitments to certain types of cinema–Asian, Canadian, environmentally-sensitive documentaries, and perhaps least well-known, arts documentaries. I still recall seeing The Red Baton, a vivid account of Russian musical life under Stalin, at my first VIFF visit in 2006, and ever since I’ve tried to check out at least a few entries in this category. They’re not usually very daring formally, but they do open up areas of the arts that I cherish, and–just as important–areas I’m completely unaware of.

Childhood and the morning of the world

For instance, as an admirer of comic strips and comic books, I had to see Josh Melrod and Tara Wray’s Cartoon College. The institution in question is the Center for Cartoon Studies at White River Junction, Vermont. (Go here for the most educational college catalog I’ve ever seen.) Each year twenty students are admitted for the two-year MFA program, and the film follows several as they move through the curriculum.

Don’t be misled by the black clothes, Kool-aid hair, and cats’-eye glasses. These kids aren’t your usual Art School posers. They want to tell stories. Jen explores menstruation; Al, the 61-year-old Boston archaeologist, takes time off to learn to draw; and Blair the Mormon wants to chronicle his missionary work. Interviews with Lynda Barry, Art Spiegelman, Charles Burns, and Chris Ware are salted through this story of intense work, achievement, and occasional disappointment.

Don’t be misled by the black clothes, Kool-aid hair, and cats’-eye glasses. These kids aren’t your usual Art School posers. They want to tell stories. Jen explores menstruation; Al, the 61-year-old Boston archaeologist, takes time off to learn to draw; and Blair the Mormon wants to chronicle his missionary work. Interviews with Lynda Barry, Art Spiegelman, Charles Burns, and Chris Ware are salted through this story of intense work, achievement, and occasional disappointment.

One accomplishment of the film is to remind us of the very unusual qualities needed to be a cartoonist. There’s the patience of drawing hundreds of panels, and sometimes the same figure in hundreds of different postures, along with the hours of fine-grain line work and coloring. There’s also the sense that of all artists, cartoonists are most in touch with childhood, that period, as Ware remarks, when each experience is “rich and warm . . . and days seem to last for weeks.”

Perhaps that’s why the students radiate that awkward innocence that’s easily mocked. They explain how they didn’t fit in with their high-school milieu; one man recalls that people assumed he was either gay or a British exchange student “because I didn’t contract all my g’s and used proper English.” The great thing students find at CCS, says Spiegelman, is that “instead of being the outcast in art school you get to be with a bunch of other outcasts.” Yet these outcasts bond, forming couples and offering group critiques, and cooperating on projects for conventions and festivals. Cartoon College teaches you a lot about cartooning, but it also reminds you of the vitality of young imagination.

Lou Harrison, whom I knew chiefly as a pioneer of melding non-Western music with classical traditions, proved to be a fascinating figure in Eva Soltes’s Lou Harrison: A World of Music. This biographical account showed me that this man often considered marginal–far less well-known than Copland or Bernstein–in fact thrived at the center of the bohemian world of American music. He went to Mills College, taught at Black Mountain College, hung around with Henry Cowell and John Cage and Virgil Thompson, collaborated with Merce Cunningham and Mark Morris, and conducted the premiere of Ives’ monumental Third Symphony.

Harrison was open to every influence, from Schoenberg’s serialism to Harry Partch’s unorthodox instrumentation. He drew on Korean and Taiwanese music and Javanese Gamelan, and even composed pieces for Geiger counters (as a protest against nuclear testing). The result is music of great delicacy, with sumptuous textures and fluid melodies. Go here to listen to some samples.

Harrison was open to every influence, from Schoenberg’s serialism to Harry Partch’s unorthodox instrumentation. He drew on Korean and Taiwanese music and Javanese Gamelan, and even composed pieces for Geiger counters (as a protest against nuclear testing). The result is music of great delicacy, with sumptuous textures and fluid melodies. Go here to listen to some samples.

Like many of his peers and collaborators, Harrison was gay, and he wasn’t shy about saying so. The partner of his later years, Will Colvig, lovingly crafted unique instruments for his compositions. After Colvig’s death, Harrison struggled to put onstage Young Caesar, a gay-centered opera–for puppets, no less. “Lou was always out of fashion,” reflects conductor Michael Tilson Thomas. Unfashionable or not, Harrison left us music of pulsating lyricism and quiet, unforced radiance. The film’s celebration of this American original deserves wide circulation. Now a personal request to Ms. Soltes: How about Alan Hovhaness next?

Nordic thaws

Then there were two films that opened my ears. I wasn’t prepared for the brawny music of Kimmo Pohjonen, who is on roaring display in Kimmo Koskela’s Soundbreaker (aka Ice Bellows). Along with street mimes and face-painters, accordion playing has become a bad joke, but Pohjonen makes it a contact sport. Built like a torpedo, with short hair razored to a cellbock edge, he plays his amplified squeezebox like he’s grappling with a python. Our musician is first shown tramping across a frozen lake and then plunging through a hole before taking up his instrument and playing underwater.

It’s a nice introduction to Extreme Music, Finnish style. Thereafter, a mixture of concert footage and daily routine takes us into a world like Lou Harrison’s, where any sound can become music. Pohjonen will solo with the Kronos Quartet or with chugging farm machinery (the clip is here). Soundbreaker was the first film I saw in my VIFF visit. After hearing this infectious wahoo music, I ordered some albums. Consider doing the same.

Speaking of Nordic revelations, there’s Grandma Lo-Fi: The Basement Tapes of Sigrídur Níelsdóttir. I can’t do better than quote the VIFF catalog, describing a lady who

decided to become a musician at the unlikely age of 70. Equipped with little more than a cassette recorder, cheap keyboards, common household items, and an adventurous spirit, she crafted an astonishing 59 albums in a mere seven years and became a DIY icon for a generation of Icelandic musicians.

Since some of those musicians include ones I follow, like múm, I had to catch up with Sigrídur.

Born in Denmark to a German mother and Danish father, she learned a little piano as a child. Later, after her sweetheart was lost at sea, she left her parents and made her own way. Parts of her life are hazy, but she wound up in Iceland with several children. Having worked as a shopkeeper, dog-walker, and lacemaker, she settled in old age in a basement apartment, where she began composing at a keyboard she called her “entertainer.”

Born in Denmark to a German mother and Danish father, she learned a little piano as a child. Later, after her sweetheart was lost at sea, she left her parents and made her own way. Parts of her life are hazy, but she wound up in Iceland with several children. Having worked as a shopkeeper, dog-walker, and lacemaker, she settled in old age in a basement apartment, where she began composing at a keyboard she called her “entertainer.”

Thanks to a double-tape boom box, she could dub and redub her compositions, often reusing commercial audiocassettes discarded from her library. Her music and voice were garnished with animal sounds (including barking dogs and cooing pigeons) and kitchenware noises. Eggbeaters made good helicopters, cheese graters evoked shamisens, and tinfoil provided campfire sounds. “Everyone is free to use these things. I don’t charge.” Like the rest of us, she self-publishes.

She filled her apartment with religious images and awoke at 4:30 AM to pray and read the Bible. Music, she says, taught her what the Bible really means. When she couldn’t sleep, she chirped to the birds; for all she knew, she might have been swearing in bird-talk. After 687 original songs, some dedicated to friends and family, she abruptly stopped her musical career and turned to cut-and-paste art. Her collages, like her music and album graphics, display simple geometric structures overwritten by doodlish embellishments, marks of classic “naive” or “outsider” art. But now outsider art inspires everyone.

The film, by Orrí Jónsson, Kristín Björk Kristjánsdóttír, and Ingíbjörg Bírgisdóttir, mimics the low-tech quality of Sigrídur’s oeuvre with rashes of graininess, images reminiscent of 8mm and VHS, and some self-conscious animation and SPFX tableaus featuring pop artists indebted to her. But the film isn’t mocking this remarkable woman, who perpetually grins in modest pride. As she tells us, “I don’t think you can do any harm with songs like these, right?” Like Lou Harrison, who was composing in his eighties, Sigrídur easily rivaled the energy and passion of Pohjonen and the kids of Cartoon College. Art keeps you young, as if you didn’t know.

I learn from many VIFFers that Alan Franey, Festival Director and CEO, is the guiding spirit behind the festival’s commitment to arts documentaries, and particularly those focused on music. For this and many other things, Kristin and I owe him our thanks.

10 October 2012: Thanks to Olli Sulopuisto for a major correction; I had initially called Pohjonen an Icelandic musician. Thanks to Olli as well for correcting a misspelled name.

Young Caesar, opera by Lou Harrison (1971).

Talks, pictures, and more

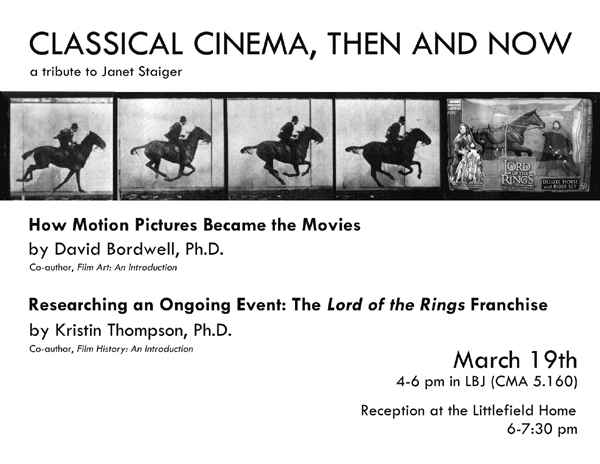

Hard though it is to believe, our dear friend and colleague Janet Staiger is retiring this year from her post as the William P. Hobby Centennial Professor of Communication at the University of Texas. About a year and a half ago, Janet joined us in writing an essay celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of the publication of our collaborative volume, The Classical Hollywood Cinema. Several of our other books have gone out of print, but that one remains available. We’re convinced that its success rests on the fact that the three of us were able to contribute different areas of expertise that meshed seamlessly to cover what turned out to be a far more ambitious topic than we initially envisioned.

We’re delighted to help celebrate Janet’s retirement, since the Department of Radio-Television-Film has invited both of us to lecture at an event to pay tribute to Janet. We’d love to see any of you in the Austin area on March 19. We chose our topics without planning it that way, but they end up book-ending the classical era. David will be speaking on the 1910s, when the early cinema was coalescing into the art of “the movies,” and Kristin deals with the question of how one can deal with a contemporary event that has not yet run its course. (KT)

Short film

The American release of Jafar Panahi’s This Is Not a Film, as well as the first Best Foreign Film Oscar for an Iranian film, A Separation (Asgar Farhadi), have kindled a new interest in Iranian cinema just as some of its most prominent practitioners are dealing with exile, house arrest, and censorship. The International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran has recently posted a short film, Iranian Cinema Under Siege, which lays out the issues succinctly.

Earlier many cinephile sites, including ours, called attention to Panahi’s plight. Anthony Kaufman updates us on his still-undetermined fate. (KT)

Lotsa pictures, lotsa fun (cont’d)

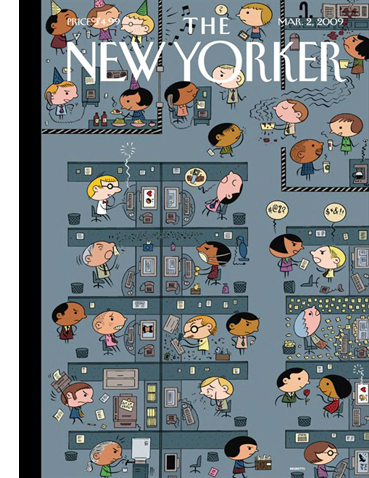

Lynda Barry, Ivan Brunetti, and Chris Ware share a mic.

Our Arts Institute has brought Lynda Barry to campus as an artist in residence this spring, and it’s been a breath of fresh air—actually, make that “blast.” Kristin and I have loved Barry’s work since the 1970s, but only recently did we learn that she was born in Wisconsin and still lives here.

Barry’s UW webpage is a captivating foray into Barryland, and her course, “What It Is: Manually Shifting the Image,” has been open to anyone interested in exploring drawing and/or writing. Convinced that art is a biological phenomenon (“Anybody can make comics,” she says), she encourages people to expand their creative powers without fear of being considered unskillful.

As part of her visit, Professor Lynda has also scheduled events to introduce people to writers and artists. She hosted Ryan Knighton (“badass blind guy”), gave a talk

As part of her visit, Professor Lynda has also scheduled events to introduce people to writers and artists. She hosted Ryan Knighton (“badass blind guy”), gave a talk on with guest Matt Groening, and will interview Dan Chaon (3 May). Her first pair of invitees, on 15 February, was Chris Ware and Ivan Brunetti.

You know I was there.

In fact, I came ninety minutes early to get my front row seat, alongside comics guru Jim Danky. Good thing too; by the time the session started, the big lecture hall was packed.

The first part of the session was a brief panel discussion among Barry, Brunetti, and Ware. As if by design, the table mike didn’t work, so Barry’s lavaliere, threaded up through her pants and blouse, had to be yanked out and stretched across the table when her guests wanted to talk. Result shown above.

Barry called Brunetti a master of balancing the verbal and the visual aspects of comics, and she introduced Ware as “the Wright Brothers” of the graphic novel, with Lint as his Kitty Hawk. Then the two guests, who live in Chicago and get together for Mexican lunch once a week, talked about their influence on one another. Brunetti says that seeing Ware’s work in Raw made him rethink comics altogether. Ware finds in Brunetti “an honest critic.”

Then Ware left the stage to Brunetti, who took us through his career in PowerPoint. He traced the influence of comics like Nancy and Peanuts on his pretty but edgy big-head style, and he talked about the autobiographical impulse behind much of his work. (“I draw these things to make fun of myself.”) Like many comics artists, he’s fascinated by cinema—be sure to check his “Produced by Val Lewton” page—and some of his New Yorker ensemble panels have the fluid connections we find in network narratives.

In all, it was a lively session that reminded me, among other things, how comic-crazy our town is. Not to mention our state: don’t forget Paul Buhle’s Comics in Wisconsin. That book is filled with work by Crumb, the Sheltons, Spiegelman, etc. It’s as well a tribute to enterprising publisher Denis Kitchen and the now-departed Capital City comics distribution firm. (DB)

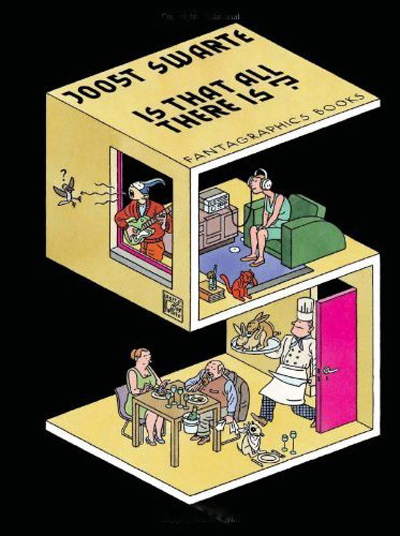

Le mot Joost

I got a little chance to talk to Ware, and we shared our admiration of Joost Swarte, one of the greats of cartooning. Readers of this blog may recall my shameless promotion of Swarte’s work (here and here and here); one of the big events of my fall was getting to meet him in a Brussels gallery. As chance would have it, a couple of days after Barry’s event, I got my copy of the new Swarte collection Is That All There Is?

The book is a fine introduction to work that has for too long been restricted to French and Dutch publications. You get to meet the infinitely knowledgable Dr. Anton Makassar, the lumpish Pierre van Genderen, and the hip but mysteriously ethnic Jopo de Pojo. You also get the first statement of Swarte’s idea of the “Atom Style” of postwar design, connected to the “clear line” school of cartoon art. The book, done up in gorgeous graphics, is graced by an introduction by none other than Chris Ware.

It’s sort of hard to write an introduction for a cartoonist you can’t completely read. . . . I’ve read plenty of his drawings, however. Studied, copied, and plagiarized them, actually; the precise visual democracy of his approach compelled me as a young cartoonist to consider the meaning of clear and readable or messy and expressive, and it was the former which won out.

Now that he mentions it, there is a line running from Ware’s obsessive schematics of narrative space (and time, as Barry says) straight back to the fluent precision of Swarte’s design. Both artists invite your eye to discover things at all level of scale and visibility, while leading you, in Hogarth’s phrase, “on a wanton kind of chase.” (DB)

Derange your day with Feuillade

Two patient, ambitious researchers have contributed to our knowledge of Louis Feuillade’s work, a central concern of DB’s writing and this blog (here and here, in particular). They also teach us intriguing things about cinematic space.

First, Roland-François Lack of University College, London hosts The Cine-Tourist, a site that traces the use of Paris locations in films. His devotion to Paris equals that of the city’s filmmakers, so he provides a thorough canvassing of areas seen in Les Vampires, Fantômas, and Judex. Beyond Feuillade, you can find the places featured in other movies, including L’Enfant de Paris and Le Samourai. Roland-François has even solved the riddle of what movie house Nana visits in Vivre sa vie.

Hector Rodriguez of the City University of Hong Kong has set up a site devoted to Gestus. It’s a program that tracks vectors of movement in a shot and generates abstract versions of them that can be compared with action in other sequences. Gestus can whiz through an entire film–in this case, Judex–and come up with an anatomy of its movement patterns. Hector sees the enterprise as sensitizing us to movement patterns that we don’t normally notice. It also provides a dazzling installation.

Gestus’ ability to generate a matrix of comparable frames recalls Aitor Gametxo’s Sunbeam exploration. But Aitor was interested in how Griffith maps adjacent three-dimensional spaces. Hector’s project focuses on two-dimensional patterning, specifically the deep kinship between different shots when rendered as abstract masses of movement. And while the Sunbeam experiment lays out how spectators mentally construct a locale, Hector is just as interested in friction. “The system invites, confuses, and sometimes frustrates the viewer’s cognitive-perceptual skills.”

That, of course, is part of what cinema is all about. Visit Roland-François’ and Hector’s sites and have a little derangement today. (DB)

If you’re unfamiliar with Chris Ware’s work, a good overview/interview can be found here. Swarte’s stupendously beautiful site is here.

PS 12 March: Because I’ve been immersed in other stuff, I didn’t realize that Matt Groening actually showed up for Barry’s session! And I missed it! Hence the strikeout correction above, initiated by Jim Danky. More on Groening’s visit here.

Echoic patterns of stooping in Judex, as revealed by Gestus.