Archive for the 'Comic strips and cartoons' Category

A hundred years, plus a few thousand more, in a day

Charlie Keil, Yuri Tsivian, Henry Jenkins, Kristin Thompson, and Janet Staiger. Photo by Joel Ninmann.

Last Saturday we held the symposium “Movies, Media, and Methods” in honor of Kristin’s arrival at age sixty. Four distinguished scholars, all professors from major universities, presented top-flight talks. As a bonus, Kristin gave The Film People a glimpse into her Egyptological work. I report on this very full day in the hope of giving a sense of how stimulating we found it.

Thanhouser was an American film company that flourished between 1909 and 1917. It has been overshadowed by Biograph because that firm put out more films and, not incidentally, employed D. W. Griffith. But Ned Thanhouser has been diligently gathering his family company’s output from archives around the world and releasing it in informative DVD editions. The most famous Thanhouser production is probably Cry of the Children (1912), a powerful attack on child labor. You could also try the thriller The Woman in White (1917), adapted from Wilkie Collins’ masterful novel. A study in sadism, and more subtle than The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

Charlie Keil, an expert in 1910s US film from the University of Toronto, examined Thanhouser’s films with two questions in mind. Did the studio have a “distinctive personality” in its products? And does its output reflect the development of film style across the crucial transitional years of the early 1910s? Borrowing a method that Kristin had applied to Vitagraph films in an essay, Charlie took one film from 1911, one from 1912, and one from 1913. Charlie wasn’t ready to conclude that these specimens displayed a unique studio style, but it was clear that across just three years, big changes in storytelling were taking place.

The plot of Get Rich Quick (1911) involves a man who joins a business that is scamming innocent investors. The film uses only five locales and plays scenes in long takes. The Little Girl Next Door (1912) has a more complex plot, with two distinct lines of action that converge on a child’s drowning. It uses many more locales and an ellipsis of a year to trace the changes in a family’s fortunes. It also incorporates cut-in close views and point-of-view editing. The Elusive Diamond (1913) is less psychology-driven than The Little Girl Next Door, but its intrigue relies almost completely on dialogue titles and it includes many close-ups and variation of camera setups.

Three films and three years: A vivid cross-section of the rapid development of what soon became classical visual storytelling. Moving from 18 shots to 53 shots to 74 shots, the films became less dependent on staging and more dependent on editing. At the same time, Charlie didn’t fail to notice how the long takes in Get Rich Quick allow some felicities of performance, particularly the way that the wife’s handling of her apron charts her psychological states. She brushes it aside to show how poor they are, then she uses it as a giant hankie.

Like all good papers, Charlie’s left a lot to be discussed. People asked about how much pre-planning was done at Thanhouser, about the directors and screenwriters on staff, about the division of labor. We were left with a sense that here was another mostly unknown region that would reward further study.

Fernand Léger, Cubist Charlot (1923).

Yuri Tsivian of the University of Chicago carried us into the twenties with an in-depth examination of early Russian reactions to Charlie Chaplin. The paper held many surprises. Chaplin was popular in many countries from 1915 onward, and very soon after he was celebrated by European intellectuals. But Russia lagged behind; there’s no concrete evidence that any Chaplin films were shown there until 1922. Yet the Soviet avant-garde embraced him. How and why?

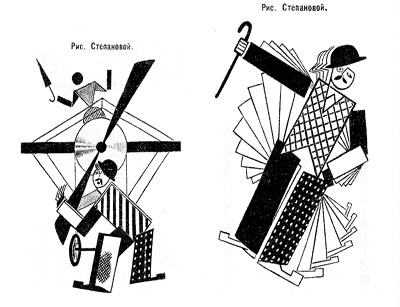

Instead of looking for a dual relationship—Chaplin directly influencing Russian artists—Yuri postulated a “triangular” relationship, in which Chaplin’s image was mediated through other European sources. For instance, Léger’s numerous images of a fragmented Chaplin led Futurists and Constructivists to declare Charlie “one of us.” They loved the idea of man as a machine executing precisely articulated movement, and what they heard of Chaplin’s pantomime and gags led them to praise him. Chaplin, said Lev Kuleshov, is “our first teacher” because he knows bio-mechanical premises better than anyone. According to the photographer and graphic designer Rodchenko Chaplin instructs viewers in how to walk or put on a hat in the most perfect manner.

So strong was this “virtual” image that artists could read Chaplin into the slapstick comedians they did see. Yuri showed that Varvara Stepanova’s striking rendition of Chaplin as an airplane propeller derived from a film he wasn’t in!

Perhaps she didn’t care: Nikolai Foregger suggested that Chaplin himself was unimportant, that the crucial fact was that he created a whole school of comedians within what Yuri called “a collaborative research community”—that is, Hollywood!

Yuri’s paper, in homage to the Russian Formalists, invoked the “law of fortuity” in art. This refers to the possibility that artistic borrowings, blendings, and crossovers are not determined by any broader social processes, as the Marxists were arguing, but are merely contingent. “Life interferes with art from below.” Accidents and unforeseen intersections, such as the Chaplin craze meeting the Constructivist movement, allow artists to seize on whatever is around them for new material. Yuri’s reference was to Kristin’s revival of Formalist methods in her “neoformalist” studies of Eisenstein, Tati, and other filmmakers.

Janet Staiger of the University of Texas at Austin collaborated with us on The Classical Hollywood Cinema, and she has for several years been the leading scholar of reception studies in film and television. In looking at the Indiana Jones series, her paper nodded to Kristin’s work on the Lord of the Rings franchise and her study of fans’ responses to the films.

“Nuking the fridge,” Janet explained, has become fan jargon for an outrageous plot twist. The phrase comes from a notorious moment in Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), in which Professor Jones escapes an atomic blast by diving into a lead-lined refrigerator. The moment becomes a crux for clashing fan judgments: This is totally unrealistic vs. Realism doesn’t matter. Janet went on to show how these and other fan responses, entwined in IMDB commentary threads, utilized several different interpretive frames.

One was authorship. Like academics and journalists, fan are auteurists. They assign the director responsibility for major aspects of the film. But this doesn’t mean that they agree in how to use this frame. In the case of Crystal Skull, a certain Kid Mogul asked if Spielberg’s willingness to reinvigorate the franchise was purely mercenary: “Is it just about the money?” Others took a more career-survey approach, noting that after prestige pictures like Schindler’s List Spielberg recalibrated his popcorn movies, particularly by handling violence more gingerly.

Another frame was story-based “lit talk.” Fans disparaging the film found it clumsily plotted and lacking in character development. Several were quite sensitive to narrative coherence, one-off gags (such as nuking the fridge), and pacing. Those defending the film appealed to the emotional burst of the final chase scenes.

Janet’s third frame of reference was what she called “formula dissonance.” She sought to capture what seeing the film would be like for those who knew Indy’s story only through the TV series or video versions of the earlier installments in the franchise. She suggested that the formula was by 2008 quite abstracted and idealized for many fans. Their sense of the franchise was thus tested by the extraterrestrial twist that resolved the Crystal Skull plot. Does it reframe the whole series in a cosmic context, or is it a violation of the premises of the Indy universe?

Janet’s survey of these types of responses made me notice that the assumptions of academic film studies and of journalistic criticism overlap with fan conversation. Fans who liked the film tried to make everything fit by appeal to organic unity, technical proficiency, emotional intensity, and other familiar criteria. It made me suspect yet another reason why “amateur” and “professional” film criticism seem to be merging: Perhaps their conceptual frames of reference aren’t so far apart. But their tastes and their degrees of commitment surely are.

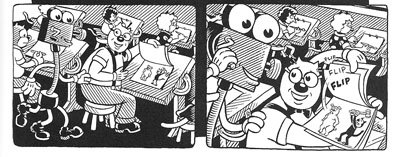

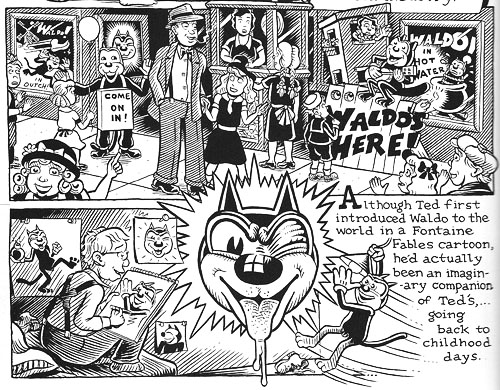

You might have expected Henry Jenkins of the Annenberg School at the University of Southern California to talk about fans too. After all, he practically invented the modern study of media fandom with his book Textual Poachers, and his work influenced Kristin’s study of fan promotion of The Lord of the Rings. Instead he turned to a survey of an artist’s oeuvre. He showed how Kim Deitch’s vast output of stories appropriate imagery from nineteenth and twentieth century mass media and present highly personal versions of the history of popular culture.

In a way, though, Henry’s talk involved fandom because Deitch is himself a prototypical fanman. He’s an obsessive collector, likely to turn his search for a rare toy or drawing into a Byzantine odyssey on the page. Fascinated by Hollywood scandal, he has constructed a phantasmagoric history of mass media through fictional characters (e.g., fake movie stars) who confront real people (e.g., Fatty Arbuckle). He’s particularly concerned about what he takes to be the warping of animated film by the influences of the mass market, epitomized by the Disney empire. The emblematic moment in Boulevard of Broken Dreams comes when Deitch’s Winsor McKay stand-in addresses torpid animators at a tribute dinner and denounces them for selling out.

Deitch’s most famous character is Waldo the cat, and Henry traced the powerful connotations of this emblematic figure. Waldo recalls Felix, the most heavily merchandised comics figure before Mickey, as well as the black cat as a figure of deception, witchcraft, and even African-American minstrelsy. Through Waldo, Deitch could hop across the history of film and comics, from McKay to Mighty Mouse and 1940s abstract films. In Alias the Cat!, Deitch finds in the 1910s everything that we associate with media today: serial narrative, stories shifting across different media platforms, an uncertain line between publicity and self-expression, and a mixing of news and sensational fiction.

Henry situated Deitch in a broader trend of comic artists trying to find a new history of their medium, one that dislodges superheroes from a central role. Deitch’s themes of old-fashioned craftsmanship, lovably antiquated technology, adult dread and degeneracy lurking behind children’s stories, and the commodity demands of comic art link him to contemporaries like Chris Ware and Art Spigelman.

Henry’s talk spurred a lot of discussion, including the question of whether we can treat an artist as offering a history that is comparable to academic research. Can Deitch’s hallucinatory vision of American media be a plausible basis for understanding what really happened? On the whole we don’t expect an artist to offer rigorous arguments. An artwork appropriates history for its own end. (Not all the Greek philosophers actually gathered together in the way Raphael depicts them in the School of Athens painting.) How cogent you find Deitch’s critique probably also depends on whether you share his disdain for Disney. His floppy-limbed denizens fuse headcomix grotesquerie with the 1930s animation that most prestige studios abandoned. As in Sally Cruikshank’s sprightly cartoon Quasi at the Quackadero, Deitch’s rubbery frames revive a style in which everything seems to throb and shimmy.

Kristin’s talk, “How I Spend My Winter Vacations: The Amarna Statuary Project and Techniques of Visual Analysis,” had two parts. In the second part, she reviewed her recent work in assembling statues out of tiny bits that had been dumped by archaeologists decades ago. You can read some of this story here. The side of her work most intriguing to students of film, I think, involves her attraction to Egyptian art in the first place.

Egyptian art is often thought of as unrealistic, but during his reign in the fourteenth century BCE the pharaoh Akhenaten introduced a peculiar sort of stylization into it. When he instituted a monotheistic religion centered on the sun god Ra (embodied in the Aten), he also demanded a new pictorial style. Thus the Aten is depicted as a disc shedding rays, a symbol of life and dominion. In addition, the royal family displays biggish hips and thighs, which fit the fecundity theme. More strikingly to our eye, Akhenaten’s family were represented as somewhat distorted, with long and narrow faces, hands, and feet. The ruler’s crown is elongated as well. Several aspects of the new style are present in Kristin’s favorite scene, a beautiful relief carving known as the Berlin family stela.

You can see the Aten’s rays ending in little hands holding ankh signs to the royal couple’s noses. But just as important is the human dimension of the scene, and two sorts of action displayed there: swiveled shoulders and pointing hands.

Unlike the flat, frontal portrayal we associate with Egyptian art, the family members are caught in twisting postures that bring one shoulder forward. Kristin explained:

Akhenaten is lifting his daughter, his foreground arm moving backward to hold her legs, the other moving forward to support her body as he kisses her. She reaches with her rear arm to chuck him affectionately under the chin, while her other arm moves backward in a pointing gesture. On the opposite site, Nefertiti’s foreground arm is held bent and backward to steady the youngest daughter of the three present, who is standing on her thigh and reaching up rather precariously to grab a golden decoration hanging from her mother’s crown. Nefertiti’s rear hand goes forward to steady the second daughter, who is also pointing, this time with her rear arm as she twists to look at her mother. These kinds of gestures can be found again and again in such scenes.

The twisting movement wasn’t unknown among images of workers and private individuals; Amarna artists, presumably encouraged by Akhenaten, applied the device to portraying the royal family.

Just as significant are the pointing gestures we find in the stela. Some scholars have interpreted them as protective gestures, which are found in other images. But Kristin points out:

In those cases, the protecting figures hold their arms straight, they stare in the direction of the thing to be protected (as one presumably would in reciting a spell), and there is something dangerous present. None of this applies in the scene in the stela.

In those cases, the protecting figures hold their arms straight, they stare in the direction of the thing to be protected (as one presumably would in reciting a spell), and there is something dangerous present. None of this applies in the scene in the stela.

After pondering this scene quite a lot, it occurred to me that it looked like a really early film, a short scene, perhaps 30 seconds long, that we were to interpret as a tiny narrative. The pointing gestures seemed comparable to pantomime, where one has to interpret movements in the absence of intertitles.

Given that so much Amarna art is about displaying the royal couple as having created life by giving birth to their daughters and as sustaining that life, it seems to me that this stela is full of indications of nurturing. The columns and roof indicate that the parents have their kids in a little shelter to keep them out of the hot sun. The rows of pots behind Akhenaten’s stool are no doubt filled with cool drinks for them. Nefertiti carefully holds onto the two children on her lap while Akhenaten kisses the eldest. My interpretation is that the eldest is saying something like, why don’t you kiss sister, too?” and the one opposite is pointing out the kiss to her mother and saying something like, “Look, daddy’s kissing sister; I want a kiss too.”

This may not sound like the sort of thing kids would say, but the circulation of affectionate gestures among the family members in these casual scenes is nearly universal. The chucking under the chin gesture used by Meretaten here shows up again and again, as do embraces and kisses.

Despite all the stylization, then, Kristin concludes that the stela depicts a scene of intimate affection, complete with a child toying with a mother’s ornament. This homely realism chimes with other realistic tendencies in Amarna art, such as the differentiation of right and left feet and the presentation of plants and animals in non-stereotyped ways. In sum, Kristin’s ability to look closely at film style helped her make discoveries about visual narrative in a completely different domain.

So our Saturday talks included cinema-related material from 1911 to about 2010, and with Kristin’s lecture we flashed back about 3300 years. Every talk was crisp and lucid. We were spared the juggling of empty abstractions, the free-associative rambling, and the self-congratulatory cleverness that plague the humanities. We got knowledge and opinion presented with enthusiasm, modesty, and good humor.

Kristin and I are grateful to our presenters, as well to all the friends old and new who showed up: Leslie Midkiff Debauche from Stevens Point, Carl Plantinga from Michigan, Peter Rist from Montreal, Brenda Benthien from Cleveland, Virginia Wright Wexman from Chicago, Vicente José Benet from Spain (via Chicago) and many others. In all, a day to remember.

For more information on Kristin’s research see my earlier entry. For other cinematic implications of the Berlin stela of Akhenaten’s family , see Kristin’s blog entry here. Her article, “Frontal Shoulders in Amarna Royal Reliefs: Solutions to an Aesthetic Problem,” is available in The Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities 27 (1997, published 2000).

All of our speakers are represented on the Web: Henry here, Charlie here, Janet here, and Yuri here (and of course on Cinemetrics). For more on Janet’s study of online critics and the frames they inherit, see her essay, “The Revenge of the Film Education Movement.”

Kim Deitch, Boulevard of Broken Dreams.

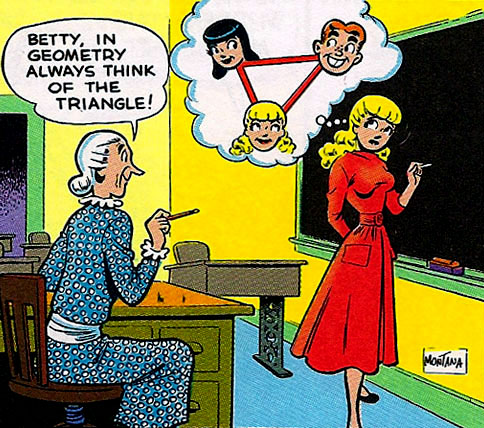

Archie types meet archetypes

DB here:

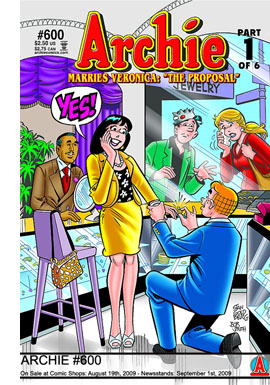

You heard about it in May, but the proof arrived in comic-book stores just lately. Archie has proposed to Veronica. At the midpoint of issue #600, he goes down on bended knee in Spiffany’s and pops the question.

The rest of the issue is devoted to other characters’ reactions. Mr. Lodge, at first outraged, says that Archie must come to work for him. Jughead is judgmental but ultimately forgiving, in his droopy-eyed way. Archie’s parents are delighted. Even Reggie shows a dash of gallantry. All of Riverdale is buzzing, but over the joyous news hangs a cloud of worry.

What about Betty?

She accidentally witnessed the proposal and at first broke down uncontrollably. Later we see her as surprisingly stoic—until she gets a phone call from Veronica (cruel? compassionate?) asking her to be maid of honor. The installment ends with Betty forlornly telling Veronica, “You—you won.”

She accidentally witnessed the proposal and at first broke down uncontrollably. Later we see her as surprisingly stoic—until she gets a phone call from Veronica (cruel? compassionate?) asking her to be maid of honor. The installment ends with Betty forlornly telling Veronica, “You—you won.”

DON’T MISS THE STORY THE WORLD HAS BEEN WAITING MORE THAN 60 YEARS TO READ! we read on the last page. Part Two, “The Wedding,” will follow next month, with four more parts after that. Archie Comics Publications has promised future episodes in which Arch and Ronnie procreate.

On her blog, Veronica is more or less gloating. Betty seems to have come to terms. On her blog she wrote:

What can I say? It is so sad.

Xoxoxoxo

Bets

Still, Betty suggests she feels the sting of mockery, and we can expect more pain in her future. Fan reaction has been far more furious. Mackenzie writes:

ARCHIE SHOULD HAVE MARRIED BETTY!! I MAY ONLY BE 10 BUT HE MUST MARRY BETTY. HOW COULD HE BE SO STUPID. I THINK HE IS TRYING TO BE RICH. POOR POOR BETTY.

One devotee, proprietor of a comics shop, sold his copy of Archie #1 in protest, and the $38,000 it fetched has not assuaged his discontent.

Like all boys I knew, I preferred Betty to Veronica. So I join in the mourning, and not just because it promises a sad married life for Arch. This upheaval threatens to destroy the Riverdale we loved. Betty working in a shop in Manhattan, Reggie in Atlanta selling cars, Moose running a burger joint in Staten Island: All dismally realistic options for today’s grads, but that’s small consolation. And what about Miss Grundy and Mr. Weatherbee and Pop Tate? Have we no cares for them?

In this crisis, panic is understandable. Yet I believe that older heads have a duty to assume leadership and calm the younger, more tempestuous spirits. A careful reading—well, okay, just a simple reading—of fateful issue #600 gives us a glimmer of hope. It also illustrates how a very old narrative convention can be revamped in popular culture.

A man of many parts

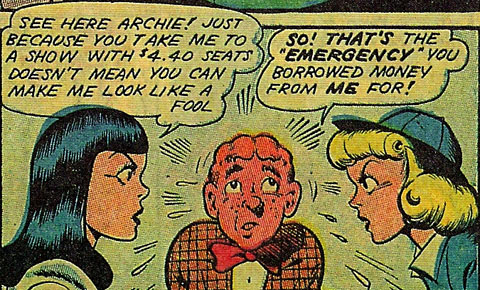

My acquaintance with the Archie series goes back to the mid-1950s. The books had already moved from the 1940s caricatural portrayal of Riverdale’s residents (above) to a more streamlined look reminiscent of Hergé’s clear line style.

Eventually the visual style would become still more minimal, offering little shading or detail and relying on a smaller repertoire of facial types, expressions, and gestures.

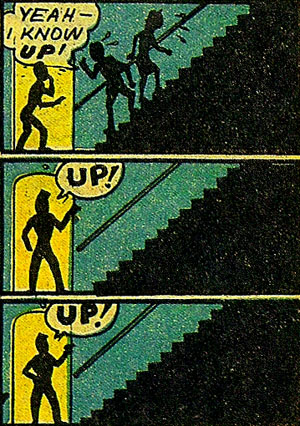

What I didn’t know then was that the first series artist, Bob Montana, was a gifted storyteller who made shrewd use of the graphic shorthand that adds so much to comics. In “Double Date” (#7, 1944), the issue that established the Eternal Triangle, Archie has wound up taking both girls to the same play. Of course neither knows that her rival is there. Archie escorts each one into the theatre and then races between Veronica in the orchestra and Betty in a distant balcony. Montana crisply renders Archie and Betty climbing past ushers to the nosebleed seats. Interestingly, this stack of panels must be read from bottom to top.

Archie races downstairs to check in with Veronica, and the swirl of his descent wraps inside the circular frame like baseball stitching. A horizontal stripe using the vertical panels’ green tone demarcates the movement between floors.

Once Betty discovers Archie’s perfidy, she stalks off, and Montana combines the two earlier framings, circle and square, yellow and green, in showing their zigzag descent.

Morover, in a story based on symmetries, each girl’s discovery of Archie’s perfidy is given a canted deep-focus framing that Orson Welles might have liked.

I wish I could find this sort of pictorial ingenuity in Archie #600, but like most of the 1950s and 1960s entries I’ve reread, this one is all about story. And fairly comedy-free story at that. Years ago boys like me followed Archie, but I suspect that now the prime readership is tween girls, so the romance-based pathos of Betty’s suffering may hit its target audience. Still, what the issue lacks in graphic sophistication may be made up for in its use of a narrative device that has become salient in popular culture, including movies.

The road not taken

In Poetics of Cinema I included an article called “Film Futures.” Originally a paper for a 2001 conference, it sought to analyze an emerging trend in filmic storytelling that has its roots in folktales and popular literature. That is the device of the hypothetical future.

The most famous example in literature probably remains A Christmas Carol, in which a ghost confronts Scrooge with a harrowing vision of his fate if he does not mend his ways. Dickens’ story showed how an alternative-future plot could be motivated by the supernatural, still a common way to show an alternative course of events. Later writers would rely on hallucination or science-fiction premises, such as time travel that allows a return to a point of choice. At various periods, films have drawn on these principles, from The Love of Sunya (1927) to Back to the Future II (1989). There are unmotivated instances of alternative futures as well in plays by J. B. Priestley, novels by Allen Drury, and art-comics by Chris Ware.

The central premise of this device goes back further. Many folktales from various cultures present brothers halting at a crossroads. Each brother picks a different road, and the plot is built out of their contrasting fates. Sometimes each road is marked with an enigmatic prediction about what will happen further along. O. Henry picked up the motif in his audacious 1903 story “Roads of Destiny,” which presents a single protagonist hypothetically taking each path in turn. His fate catches up with him whether he chooses one road or the other or just returns home.

In my essay I explore how the idea of forking-path futures was revived on film in Kieslowski’s Blind Chance (1987), Tykwer’s Run Lola Run (1998), Peter Howitt’s Sliding Doors (1998), and Wai Ka-fai’s Too Many Ways to Be No. 1 (1997). The essay aims to show how this plot formula, so apparently free-form, relies on a set of firm conventions. For example, in principle the character might have an indefinitely large set of fates, but the first parallel universe presented sets the premises–characters, issues, and the like–that will be varied in the other alternatives. The conventions, I argue, allow the filmmakers to establish a surprisingly narrow set of options, but this trains us to notice fine-grained differences.

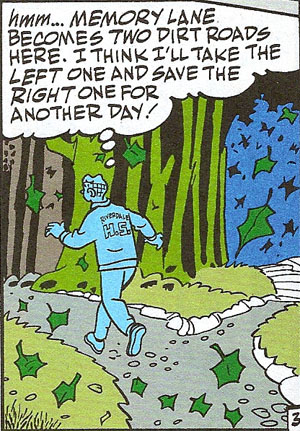

Archie’s proposal to Veronica, we learn, takes place in just such an alternative future. The present time of the narrative in issue #600 is the night of Archie’s last high-school rock concert. But Archie, facing the need to apply to college, goes out for a walk. He arrives at Memory Lane. Instead of walking down the lane—that is, into the past—he walks in the opposite direction, into the future. Suddenly he’s encountering his parents on the night of his graduation from college. A title intervenes.

Stop the presses! Did Mr. Andrews say Archie was graduating from COLLEGE? What happened to HIGH SCHOOL? By walking up Memory Lane, has Archie walked into his own FUTURE?

In short, yes. Everything we encounter from here on takes place four years after the initial scenes. Archie’s proposal and Betty’s fraught response are set in the future, as presumably will be the wedding and the eventual birth of Archie’s and Veronica’s children.

Already, then, there’s a way to set things right in Riverdale. That’s to change the future, to treat it as only one possible line of action. And in taking Archie up Memory Lane our plotters have relied on the folk archetype I’ve just mentioned.

This is quite a tease. The motif of pairs that we saw in “Double Date” returns with a vengeance. (A propos, it’s announced on the Internets that Archie and Veronica will have twins.) More important, the presence of a second road suggests that Archie has another future, one in which he doesn’t propose to Veronica. This device allows Arch to retreat at any time back along Memory Lane, and then back to the choice-point. Maybe there he will take the “right” road and eventually choose Betty? And is it an accident that the road on the left, drawing him toward marriage to Veronica, takes him into a gloomy forest, while the other one, paved in white stones, leads to a blue sky?

So the narrative leaves an escape hatch: Arch could retreat to this fork. Or he might even decide that he doesn’t want to know his other fate. In which case he could go back down Memory Lane, pass the point he entered, go further back in time, and return to his high school days, putting college—Archie a history major?—into a fuzzy future. But plot it yourself. Or follow the developments through the next five months.

Archie #600 may be offering its young readers a tutorial in understanding alternative-future plots–hence the redundant explanations in the panel quoted above. Historically,though, it’s behind the curve; the recent vogue for forking-path plots seems to have passed. Why did such plots become more common around the turn of the last century? We might invoke Steven Johnson’s argument, in Everything Bad Is Good for You, that audiences got smarter, so narratives became more complicated. Other students of “puzzle films” want to trace such narrative hijinks to postmodernity; no surprise there.

My own explanations can be found in the essay, where I look to factors like modern media’s intense demand for novelty, the quick spread (and exhaustion) of narrative innovations, and most specifically the conventions of storytelling established in things like branching-tree video games and the Choose Your Own Adventure books. Whatever the causes, at any point in history, very old narrative techniques lie waiting to be dusted off and given a fresh polish in the popular arts. Even Archie, going on seventy and still technically a bachelor, can get a makeover.

Archie Comic Publications has its website here. The story “Double Date” is reprinted in Charles Phillips, Archie: His First 50 Years (New York: Artabras, 1991), 34-44. An early published version of my “Film Futures” piece is here via library access, but the revised and expanded version in Poetics of Cinema is preferable. The “choice-of-roads” device is N122.0.1 in Stith Thompson’s Motif-Index of Folk Literature. It is discussed in Archetypes and Motifs in Folklore and Literature: A Handbook, ed. Jane Garry and Hasan El-Shamy (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 2005), 333-341.

P.S. 14 August 2010: Archie’s multiple futures were only the beginning of a major rebranding effort.

P.P.S. 23 January 2017: Turns out that Forking-Paths Archie was a turning-point for both the hero and the company. See this fascinating Vulture story.

Books, an essential part of any stimulus plan

The Pathé Palace theatre, Brussels, designed by Paul Hamesse.

DB here:

Some shamefully brief notes on new publications. Disclaimer: All are by friends. Modified disclaimer: I have excellent taste in friends.

You call me reductive like that’s a bad thing

It’s easy to see why we might tell each other factual stories. We have an appetite for information, and knowing more stuff helps us cope with the social and natural world. We can also imagine why people tell fictitious stories that we think are true. Liars want to gain power by creating false beliefs in others. But now comes the puzzle. Why do we spend so much of our time telling one another stories that neither side believes?

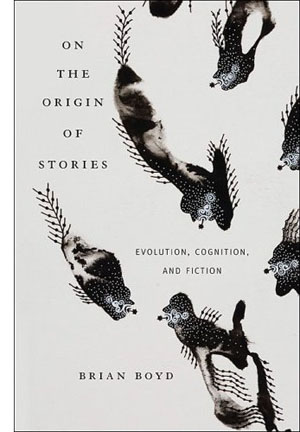

Brian Boyd’s On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction (Harvard University Press) is the first comprehensive study of how the evolution of humans as a social, adaptively flexible species has shaped our propensity for fictional narrative. The book is a real blockbuster, making use of a huge range of findings in the social and biological sciences. Brian paints a plausible picture, I believe, of the sources of storytelling. Along the way he shows how two specimens of fiction, The Odyssey and Horton Hears a Who, exemplify the richness and value of make-believe stories.

Brian Boyd’s On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction (Harvard University Press) is the first comprehensive study of how the evolution of humans as a social, adaptively flexible species has shaped our propensity for fictional narrative. The book is a real blockbuster, making use of a huge range of findings in the social and biological sciences. Brian paints a plausible picture, I believe, of the sources of storytelling. Along the way he shows how two specimens of fiction, The Odyssey and Horton Hears a Who, exemplify the richness and value of make-believe stories.

The standard objection to an evolutionary approach to art is that it’s reductive. It supposedly robs an individual artwork of its unique flavor, or it boils art-making down to something it isn’t, something blindly biological. Art is supposed to be really, really special. We want it to be far removed from primate hierarchies, mating behavior, or gossip. For a typical criticism along these lines, see this review of Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct. Brian has already adroitly responded to this sort of complaint here. See also Joseph Carroll’s examination of reductivism on his site.

It seems to me that all worthwhile explanations are reductive in some way. They simplify and idealize the phenomenon (usually known as “messy reality”) by highlighting certain causes and functions. This doesn’t make such explanations inherently wrong, since some questions can be plausibly answered in such terms. For example, often the literary theorist is asking questions about regularities, those patterns that emerge across a variety of texts. That question already indicates that the researcher isn’t trying to capture reality in all its cacophony. (For me, it’s all about the questions.)

Literary humanists sometimes talk as if they want explanations to be as complex as the thing being explained. But that would be like asking for the map to be as detailed as the territory. In fact, however, humanists tacitly recognize that explanations can’t capture every twitch and bump of the phenomenon. Consider some types of explanations that are common in the humanities: Culture made this happen. Race/ class/ gender / all the above caused that. Whatever the usefulness of these constructs, it’s hard to claim that they’re not “reductive”—that is to say, selective, idealized, and more abstract than the movie or novel being examined. Likewise, when people decry evolutionary aesthetics for its “universalist” impulse, I want to ask: Don’t many academics take culture or the social construction of gender to be universals?

I want to write more about Brian’s remarkable book when I talk about our annual convention of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. For now, I’ll just quote Steven Pinker’s praise for On the Origin of Stories: “This is an insightful, erudite, and thoroughly original work. Aside from illuminating the human love of fiction, it proves that consilience between the humanities and sciences can enrich both fields of knowledge.”

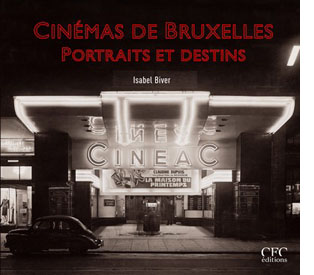

Faded beauties of Belgium

In its day, Brussels played host to some fabulous picture palaces. Now after years of research Isabel Biver has given us a deluxe book, Cinémas de Bruxelles: Portraits et destins. It’s the most comprehensive volume I know on any city’s cinemas.

Isabel glides backward from contemporary multiplexes and tiny repertory houses to the grandeur of the picture palaces. The Eldorado was a blend of Art Deco style and quasi-African motifs sculpted in stucco. King Albert graced the opening in 1933. There was the Variétés, a multi-purpose house built in 1937. It had rotating stages, air conditioning, and space for nearly 2000 souls (cut back to a thousand when Cinerama was installed). It was, Isabel claims, the first movie house in the world to be lit entirely by neon.

Isabel glides backward from contemporary multiplexes and tiny repertory houses to the grandeur of the picture palaces. The Eldorado was a blend of Art Deco style and quasi-African motifs sculpted in stucco. King Albert graced the opening in 1933. There was the Variétés, a multi-purpose house built in 1937. It had rotating stages, air conditioning, and space for nearly 2000 souls (cut back to a thousand when Cinerama was installed). It was, Isabel claims, the first movie house in the world to be lit entirely by neon.

Then there was the Pathé Palace, shown at the top of this entry. Dating back to 1913, it boasted 2500 places and included cafes and even a garden. This imposing Art Nouveau building was designed by Paul Hamesse, probably the city’s most inspired theatre architect. Hamesse also created the Agora Palace, which opened in 1922. Huge (nearly 3000 seats), the Agora was one of the most luxurious film theatres in Europe.

And we can’t forget the Métropole, the very incarnation of the modern style. Sinuous in its Art Deco lines, it packed in 3000 viewers. When it opened in 1932, it attracted nearly 53,000 spectators during its first week. The neon on the Métropole’s façade lit up the night, and its two-tiered glassed-in mezzanine became as much a spectacle as the films inside. See the still at the bottom of this earlier entry of mine. A ghost of its former self still sits on the Rue Neuve. Local historians consider the failure to preserve the Métropole a scandal in the city’s architectural history.

Cinémas de Bruxelles is a model presentation of local theatres. Not only does it trace the history of the major houses, but it includes a glossary of terms, a large bibliography, and an index of all theatres, both central and suburban. Needless to say, it is gorgeously illustrated. Whether or not you read French, I think you would enjoy this book, for it evokes an age we’re all nostalgic for, even if we didn’t live through it.

A TV interview with Isabel in French is here, with glimpses of what remains of the Métropole. She also gives guided tours of the remaining cinemas in the city center and in the neighborhoods. More information here.

A guy named Joe

Tropical Malady.

It’s seldom that a young filmmaker gets a hefty book devoted to him. Apichatpong Weerasethakul (aka Joe) will turn forty next year. He comes from Thailand, not a country adept at negotiating world film culture, and he is known chiefly for only four features. Yet he has become one of the most admired filmmakers on the festival circuit. His films are apparently very simple, usually built on parallel narratives. They have a relaxed tempo, exploiting long takes, often shot from a fixed vantage point, and scenes whose story points emerge very gradually. Joe’s movies tease your imagination while captivating your eyes. Each one could earn the title of his first feature: Mysterious Object at Noon.

It’s appropriate, then, that the tireless Austrian Film Museum has published a lavish collection of critical studies. Edited by James Quandt, the anthology arrives along with a massive retrospective of the director’s work, which includes many short documentaries and occasional pieces.

It’s appropriate, then, that the tireless Austrian Film Museum has published a lavish collection of critical studies. Edited by James Quandt, the anthology arrives along with a massive retrospective of the director’s work, which includes many short documentaries and occasional pieces.

James’ introductory essay, as evocative and eloquent as usual, is virtually a monograph, discussing all the features in depth. Alongside it are discerning essays by other old hands. Tony Rayns offers his usual incisive observations, focusing largely on Joe’s short films and the recurring imagery of hospitals, while Benedict Anderson surveys the Thai reception of Tropical Malady. Karen Newman offers precious information and judgments about Joe’s installations. The director himself signs several essays and participates in interviews and exchanges. Even Tilda Swinton has something to say.

I remember when Mysterious Object at Noon played the Brussels festival Cinédécouvertes in 2000. I was baffled. Joe’s movies taught me to watch them, and finally with Syndromes and a Century I got in sync. Its austere lyricism, off-center humor, and patiently unfolding echoes win me over every time I see it. (You can search this blogsite for several mentions, but JJ Murphy has a fuller appreciation of Syndromes here.) Thanks to Alexander Horwath and his colleagues for making this wonderful anthology, decked out with color stills and rich bibliography and filmography, available to us—and in English.

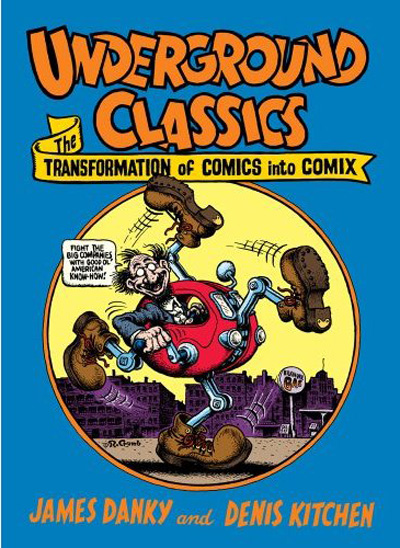

Zap goes the Chazen

Zap, Snarf, Subvert, Young Lust, Tits & Clits, Air Pirates Funnies, Slow Death Funnies, Feds ‘n’ Heads, Corn Fed Comics, Dope Comix, Cocaine Comix, Corporate Crime Comics: The names define the era. The sixties didn’t end until the mid-1970s, and these outrageous cartoon books really came into their own after the election of Nixon in 1968.

On 2 May, the Chazen Museum on our campus launches its exhibition, Underground Classics: The Transformation of Comics into Comix, 1963-1990. A whirlwind of events, including films and lectures, will revolve around galleries full of imagery from the demented pens of Kim Deitch, Aline Kominsky Crumb, Trina Robbins, Gilbert Shelton, Robert Crumb, Bill Griffith, and many other cartoonists.

The show was originated by Jim Danky, a scholar of public media from our State Historical Society, and Denis Kitchen, comic artist and the publisher of Kitchen Sink Press here in Wisconsin. Jim has long argued for the archival value of minority and subcultural publications. He started our Center for Print Culture and has been an advocate for gathering print materials by and for children, women, and ethnic minorities. He virtually created the area of “alternative library journalism”—collecting obscure publications from all zones of the political spectrum. I recall his satisfaction in telling me that he had managed to acquire a collection of The War Is Now!, the radical Catholic newsletter published by Hutton Gibson, father of Mel.

The show was originated by Jim Danky, a scholar of public media from our State Historical Society, and Denis Kitchen, comic artist and the publisher of Kitchen Sink Press here in Wisconsin. Jim has long argued for the archival value of minority and subcultural publications. He started our Center for Print Culture and has been an advocate for gathering print materials by and for children, women, and ethnic minorities. He virtually created the area of “alternative library journalism”—collecting obscure publications from all zones of the political spectrum. I recall his satisfaction in telling me that he had managed to acquire a collection of The War Is Now!, the radical Catholic newsletter published by Hutton Gibson, father of Mel.

For some years Jim has been telling me about his efforts to mount the comix show. It’s no small matter to collect this elusive material and then persuade a museum to show it. Not too many galleries feature talking penises, Jesus visiting a faculty party, or Mickey and Minnie robbed at gunpoint by a dope dealer. Maybe we forget, in the age of the Web and The Onion, just how scabrous these things looked forty years ago. Actually, they still look scabrous. They also look pretty funny, and they’re often well-drawn. As a historical codicil, the exhibition includes 1980s images from artists extending the tradition, such as Drew Friedman and Charles Burns.

The show runs until 12 July 2009. If you can’t get to town, there’s the splendid catalogue. It includes essays by Jim and Denis, Jay Lynch, Patrick Rosenkranz, Trina Robbins, and Paul Buhle. There are free screenings of Fritz the Cat and Crumb at our Cinematheque. And you can read an interview with Jim about the show here.

Remember our motto: Lotsa pictures, lotsa fun.

Up next: Days and nights at Ebertfest.

The Eldorado Cinema, Brussels, designed by Marcel Chabot.

Superheroes for sale

DB here:

After a day at the movies, maybe I am living in a parallel universe. I go to see two films praised by people whose tastes I respect. I find myself bored and depressed. I’m also asking questions.

Over the twenty years since Batman (1989), and especially in the last decade or so, some tentpole pictures, and many movies at lower budget levels, have featured superheroes from the Golden and Silver age of comic books. By my count, since 2002, there have been between three and seven comic-book superhero movies released every year. (I’m not counting other movies derived from comic books or characters, like Richie Rich or Ghost World.)

Until quite recently, superheroes haven’t been the biggest money-spinners. Only eleven of the top 100 films on Box Office Mojo’s current worldwide-grosser list are derived from comics, and none ranks in the top ten titles. But things are changing. For nearly every year since 2000, at least one title has made it into the list of top twenty worldwide grossers. For most years two titles have cracked this list, and in 2007 there were three. This year three films have already arrived in the global top twenty: The Dark Knight, Iron Man, and The Incredible Hulk (four, if you count Wanted as a superhero movie).

This 2008 successes have vindicated Marvel’s long-term strategy to invest directly in movies and have spurred Warners to slate more comic-book titles. David S. Cohen analyses this new market here. So we are clearly in the midst of a Trend. My trip to the multiplex got me asking: What has enabled superhero comic-book movies to blast into a central spot in today’s blockbuster economy?

Enter the comic-book guys

It’s clearly not due to a boom in comic-book reading. Superhero books have not commanded a wide audience for a long time. Statistics on comic-book readership are closely guarded, but the expert commentator John Jackson Miller reports that back in 1959, at least 26 million comic books were sold every month. In the highest month of 2006, comic shops ordered, by Miller’s estimate, about 8 million books (and this total includes not only periodical comics but graphic novels, independent comics, and non-superhero titles). There have been upticks and downturns over the decades, but the overall pattern is a steep slump.

Try to buy an old-fashioned comic book, with staples and floppy covers, and you’ll have to look hard. You can get albums and graphic novels at the chain stores like Borders, but not the monthly periodicals. For those you have to go to a comics shop, and Hank Luttrell, one of my local purveyors of comics, estimates there aren’t more than 1000 of them in the U. S.

Moreover, there’s still a stigma attached to reading superhero comics. Even kitsch novels have long had a slightly higher cultural standing than comic books. Admitting you had read The Devil Wears Prada would be less embarrassing than admitting you read Daredevil.

For such reasons and others, the audience for superhero comics is far smaller than the audience for superhero movies. The movies seem to float pretty free of their origins; you can imagine a young Spider-Man fan who loved the series but never knew the books. What’s going on?

Men in tights, and iron pants

The films that disappointed me on that moviegoing day were Iron Man and The Dark Knight. The first seemed to me an ordinary comic-book movie endowed with verve by Robert Downey Jr.’s performance. While he’s thought of as a versatile actor, Downey also has a star persona—the guy who’s wound a few turns too tight, putting up a good front with rapid-fire patter (see Home for the Holidays, Wonder Boys, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, Zodiac). Downey’s cynical chatterbox makes Iron Man watchable. When he’s not onscreen we get excelsior.

Christopher Nolan showed himself a clever director in Memento and a promising one in The Prestige. So how did he manage to make The Dark Knight such a portentously hollow movie? Apart from enjoying seeing Hong Kong in Imax, I was struck by the repetition of gimmicky situations–disguises, hostage-taking, ticking bombs, characters dangling over a skyscraper abyss, who’s dead really once and for all? The fights and chases were as unintelligible as most such sequences are nowadays, and the usual roaming-camera formulas were applied without much variety. Shoot lots of singles, track slowly in on everybody who’s speaking, spin a circle around characters now and then, and transition to a new scene with a quick airborne shot of a cityscape. Like Jim Emerson, I thought that everything hurtled along at the same aggressive pace. If I want an arch-criminal caper aiming for shock, emotional distress, and political comment, I’ll take Benny Chan’s New Police Story.

Then there are the mouths. This is a movie about mouths. I couldn’t stop staring at them. Given Batman’s cowl and his husky whisper, you practically have to lip-read his lines. Harvey Dent’s vagrant facial parts are especially engaging around the jaws, and of course the Joker’s double rictus dominates his face. Gradually I found Maggie Gyllenhaal’s spoonbill lips starting to look peculiar.

The expository scenes were played with a somber knowingness I found stifling. Quoting lame dialogue is one of the handiest weapons in a critic’s arsenal and I usually don’t resort to it; many very good movies are weak on this front. Still, I can’t resist feeling that some weighty lines were doing duty for extended dramatic development, trying to convince me that enormous issues were churning underneath all the heists, fights, and chases. Know your limits, Master Wayne. Or: Some men just want to watch the world burn. Or: In their last moments people show you who they really are. Or: The night is darkest before the dawn.

I want to ask: Why so serious?

Odds are you think better of Iron Man and The Dark Knight than I do. That debate will go on for years. My purpose here is to explore a historical question: Why comic-book superhero movies now?

Z as in Zeitgeist

More superhero movies after 2002, you say? Obviously 9/11 so traumatized us that we feel a yearning for superheroes to protect us. Our old friend the zeitgeist furnishes an explanation. Every popular movie can be read as taking the pulse of the public mood or the national unconscious.

I’ve argued against zeitgeist readings in Poetics of Cinema, so I’ll just mention some problems with them:

*A zeitgeist is hard to pin down. There’s no reason to think that the millions of people who go to the movies share the same values, attitudes, moods, or opinions. In fact, all the measures we have of these things show that people differ greatly along all these dimensions. I suspect that the main reason we think there’s a zeitgeist is that we can find it in popular culture. But we would need to find it independently, in our everyday lives, to show that popular culture reflects it.

*So many different movies are popular at any moment that we’d have to posit a pretty fragmented national psyche. Right now, it seems, we affirm heroic achievement (Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, Kung Fu Panda, Prince Caspian) except when we don’t (Get Smart, The Dark Knight). So maybe the zeitgeist is somehow split? That leads to vacuity, since that answer can accommodate an indefinitely large number of movies. (We’d have to add fractions of our psyche that are solicited by Sex and the City and Horton Hears a Who!)

*The movie audience isn’t a good cross-section of the general public. The demographic profile tilts very young and moderately affluent. Movies are largely a middle-class teenage and twentysomething form. When a producer says her movie is trying to catch the zeitgeist, she’s not tracking retired guys in Arizona wearing white belts; she’s thinking mostly of the tastes of kids in baseball caps and draggy jeans.

* Just because a movie is popular doesn’t mean that people have found the same meanings in it that critics do. Interpretation is a matter of constructing meaning out of what a movie puts before us, not finding the buried treasure, and there’s no guarantee that the critic’s construal conforms to any audience member’s.

*Critics tend to think that if a movie is popular, it reflects the populace. But a ticket is not a vote for the movie’s values. I may like or dislike it, and I may do either for reasons that have nothing to do with its projection of my hidden anxieties.

*Many Hollywood films are popular abroad, in nations presumably possessing a different zeitgeist or national unconscious. How can that work? Or do audiences on different continents share the same zeitgeist?

Wait, somebody will reply, The Dark Knight is a special case! Nolan and his collaborators have strewn the film with references to post-9/11 policies about torture and surveillance. What, though, is the film saying about those policies? The blogosphere is already ablaze with discussions of whether the film supports or criticizes Bush’s White House. And the Editorial Board of the good, gray Times has noticed:

It does not take a lot of imagination to see the new Batman movie that is setting box office records, The Dark Knight, as something of a commentary on the war on terror.

You said it! Takes no imagination at all. But what is the commentary? The Board decides that the water is murky, that some elements of the movie line up on one side, some on the other. The result: “Societies get the heroes they deserve,” which is virtually a line from the movie.

I remember walking out of Patton (1970) with a hippie friend who loved it. He claimed that it showed how vicious the military was, by portraying a hero as an egotistical nutcase. That wasn’t the reading offered by a veteran I once talked to, who considered the film a tribute to a great warrior.

It was then I began to suspect that Hollywood movies are usually strategically ambiguous about politics. You can read them in a lot of different ways, and that ambivalence is more or less deliberate.

A Hollywood film tends to pose sharp moral polarities and then fuzz or fudge or rush past settling them. For instance, take The Bourne Ultimatum: Yes, the espionage system is corrupt, but there is one honorable agent who will leak the information, and the press will expose it all, and the malefactors will be jailed. This tactic hasn’t had a great track record in real life.

The constitutive ambiguity of Hollywood movies helpfully disarms criticisms from interest groups (“Look at the positive points we put in”). It also gives the film an air of moral seriousness (“See, things aren’t simple; there are gray areas”). That’s the bait the Times writers took.

I’m not saying that films can’t carry an intentional message. Bryan Singer and Ian McKellen claim the X-Men series criticizes prejudice against gays and minorities. Nor am I saying that an ambivalent film comes from its makers delicately implanting counterbalancing clues. Sometimes they probably do. More often, I think, filmmakers pluck out bits of cultural flotsam opportunistically, stirring it all together and offering it up to see if we like the taste. It’s in filmmakers’ interests to push a lot of our buttons without worrying whether what comes out is a coherent intellectual position. Patton grabbed people and got them talking, and that was enough to create a cultural event. Ditto The Dark Knight.

Back to basics

If the zeitgeist doesn’t explain the flourishing of the superhero movie in the last few years, what does? I offer some suggestions. They’re based on my hunch that the genre has brought together several trends in contemporary Hollywood film. These trends, which can commingle, were around before 2000, but they seem to be developing in a way that has created a niche for the superhero film.

The changing hierarchy of genres. Not all genres are created equal, and they rise or fall in status. As the Western and the musical fell in the 1970s, the urban crime film, horror, and science-fiction rose. For a long time, it would be unthinkable for an A-list director to do a horror or science-fiction movie, but that changed after Polanski, Kubrick, Ridley Scott, et al. gave those genres a fresh luster just by their participation. More recently, I argue in The Way Hollywood Tells It, the fantasy film arrived as a respectable genre, as measured by box-office receipts, critical respect, and awards. It seems that the sword-and-sorcery movie reached its full rehabilitation when The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King scored its eleven Academy Awards.

The comic-book movie has had a longer slog from the B- and sub-B-regions. Superman, Flash Gordon, and Dick Tracy were all fodder for serials and low-budget fare. Prince Valiant (1954) was the only comics-derived movie of any standing in the 1950s, as I recall, and you can argue that it fitted into a cycle of widescreen costume pictures. (Though it looks like a pretty camp undertaking today.) Much later came revivals of the two most popular superheroes, Superman (1978) and Batman (1989).

The success of the Batman film, which was carefully orchestrated by Warners and its DC comics subsidiary, can be seen as preparing the grounds for today’s superhero franchises. The idea was to avoid simply reiterating a series, as the Superman movie did, or mocking it, as the Batman TV show did. The purpose was to “reimagine” the series, to “reboot” it as we now say, the way Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns re-launched the Batman comic. Rebooting modernizes the mythos by reinterpreting it in a thematically serious and graphically daring way.

During the 1990s, less famous superheroes filled in as the Batman franchise tailed off. Examples were The Rocketeer (1991), Timecop (1994), The Crow (1994) and The Crow: City of Angels (1996), Judge Dredd (1995), Men in Black (1997), Spawn (1997), Blade (1998), and Mystery Men (1999). Most of these managed to fuse their appeals with those of another parvenu genre, the kinetic action-adventure movie.

Significantly, these were typically medium-budget films from semi-independent companies. Although some failed, a few were huge and many earned well, especially once home video was reckoned in. Moreover, the growing number of titles, sometimes featuring name actors, fueled a sense that this genre was becoming important. As often happens, marginal companies developed the market more nimbly than the big ones, who tend to move in once the market has matured.

I’d also suggest that The Matrix (1999) helped legitimize the cycle. (Neo isn’t a superhero? In the final scene he can fly.) The pseudophilosophical aura this movie radiated, as well as its easy familiarity with comics, videogames, and the Web, made it irrevocably cool. Now ambitious young directors like Nolan, Singer, and Brett Ratner could sign such projects with no sense they were going downmarket.

The importance of special effects. Arguably there were no fundamental breakthroughs in special-effects technology from the 1940s to the 1960s. But with motion-control cinematography, showcased in the first Star Wars installment (1977) filmmakers could create a new level of realism in the use of miniatures. Later developments in matte work, blue- and green-screen techniques, and digital imagery were suited to, and driven by, the other genres that were on the rise—horror, science-fiction, and fantasy—but comic-book movies benefited as well. The tagline for Superman was “You’ll believe a man can fly.”

Special effects thereby became one of a film’s attractions. Instead of hiding the technique, films flaunted it as a mark of big budgets and technological sophistication. The fantastic powers of superheroes cried out for CGI, and it may be that convincing movies in the genre weren’t really ready until the software matured.

The rise of franchises. Studios have always sought predictability, and the classic studio system relied on stars and genres to encourage the audience to return for more of what it liked. But as film attendance waned, producers looked for other models. One that was successful was the branded series, epitomized in the James Bond films. With the rise of the summer blockbuster, producers searched for properties that could be exploited in a string of movies. A memorable character could tie the installments together, and so filmmakers turned to pop literature (e.g., the Harry Potter books) and comic books. Today, Marvel Enterprises is less concerned with publishing comics than with creating film vehicles for its 5000 characters. Indeed, to get bank financing it put up ten of its characters as collateral!

Yet a single character might not sustain a robust franchise. Henry Jenkins has written about how popular culture is gravitating to multi-character “worlds” that allow different media texts to be carved out of them. Now that periodical sales of comics have flagged, the tail is wagging the dog. The 5000 characters in the Marvel Universe furnish endless franchise opportunities. If you stayed for the credit cookie at the end of Iron Man, you saw the setup for a sequel that will pair the hero with at least one more Marvel protagonist.

Merchandising and corporate synergy. It’s too obvious to dwell on, but superhero movies fit neatly into the demand that franchises should spawn books, TV shows, soundtracks, toys, apparel, and so on. Time Warner’s acquisition of DC Comics was crucial to the cross-platform marketing of the first Batman. Moreover, most comics readers are relatively affluent (a big change from my boyhood), so they have the income to buy action figures and other pricy collectibles, like a Batbed.

The shift from an auteur cinema to a genre cinema. The classic studio system maintained a fruitful, sometimes tense, balance between directorial expression and genre demands. Somewhere in recent decades that balance has split into polarities. We now have big-budget genre films that made by directors of no discernible individuality, and small “personal” films that showcase the director’s sensibility. There have always been impersonal craftsmen in Hollywood, but the most distinctive directors could often bring their own sensibilities to projects big or small.

David Lynch could make Dune (1984) part of his own oeuvre, but since then we have many big-budget genre pictures that bear no signs of directorial individuality. In particular, science-fiction, fantasy, and superhero movies demand so much high-tech input, so much preparation, so many logistical tasks in shooting, and such intensive postproduction, that economy of effort favors a standardized look and feel. Hence perhaps the recourse to well-established techniques of shooting and cutting; intensified continuity provides a line of least resistance. A comic-book movie can succeed if it doesn’t stray from the fanbase’s expectations and swiftly initiates the newbies. Not much directorial finesse is needed, as 300 (2007) shows.

The development of the megapicture may have led the more talented directors to the “one for them, one for me” motto. Think of the difference between Burton’s Planet of the Apes or even Sweeney Todd and, say, Ed Wood or Big Fish. Or think of the moments of elegance in Memento and The Prestige, as opposed to the blunt handling of Batman Begins and The Dark Knight.

Shock and awe in presentation. The rise of the multiplex meant not only an upgrade in comfort (my back appreciates the tilting seats) but also a demand for big pictures and big sound. Smaller, more intimate movies look woeful on your megascreen, and what’s the point of Dolby surround channels if you’re watching a Woody Allen picture? Like science-fiction and fantasy, the adventures of a superhero in yawning landscapes fill the demand for immersion in a punchy, visceral entertainment. Scaling the film for Imax, as Superman Returns and The Dark Knight have, is the next step in this escalation.

Shock and awe in presentation. The rise of the multiplex meant not only an upgrade in comfort (my back appreciates the tilting seats) but also a demand for big pictures and big sound. Smaller, more intimate movies look woeful on your megascreen, and what’s the point of Dolby surround channels if you’re watching a Woody Allen picture? Like science-fiction and fantasy, the adventures of a superhero in yawning landscapes fill the demand for immersion in a punchy, visceral entertainment. Scaling the film for Imax, as Superman Returns and The Dark Knight have, is the next step in this escalation.

Too much is never enough. Since the 1980s, mass-audience pictures have gravitated toward ever more exaggerated presentation of momentary effects. In a comedy, if a car is about to crash, everyone inside must stare at the camera and shriek in concert. Extreme wide-angle shooting makes faces funny in themselves (or so Barry Sonnenfeld thinks). Action movies shift from slo-mo to fast-mo to reverse-mo, all stitched together by ramping, because somebody thinks these devices make for eye candy. Steep high and low angles, familiar in 1940s noir films, were picked up in comics, which in turn re-influenced movies.

Movies now love to make everything airborne, even the penny in Ghost. Things fly out at us, and thanks to surround channels we can hear them after they pass. It’s not enough simply to fire an arrow or bullet; the camera has to ride the projectile to its destination—or, in Wanted, from its target back to its source. In 21 of earlier this year, blackjack is given a monumentality more appropriate to buildings slated for demolition: giant playing cards whoosh like Stealth fighters or topple like brick walls.

I’m not against such one-off bursts of imagery. There’s an undoubted wow factor in seeing spent bullet casings shower into our face in The Matrix.

I just ask: What do such images remind us of? My answer: Comic book panels, those graphically dynamic compositions that keep us turning the pages. In fact, we call such effects “cartoonish.” Here’s an example from Watchmen, where the slow-motion effect of the Smiley pin floating down toward us is sustained by a series of lines of dialogue from the funeral service.

With comic-book imagery showing up in non-comic-book movies, one source may be greater reliance on storyboards and animatics. Spfx demand intensive planning, so detailed storyboarding was a necessity. Once you’re planning shot by shot, why not create very fancy compositions in previsualization? Spielberg seems to me the live-action master of “storyboard cinema.” And of course storyboards look like comic-book pages.

The hambone factor. In the studio era, star acting ruled. A star carried her or his persona (literally, mask) from project to project. Parker Tyler once compared Hollywood star acting to a charade; we always recognized the person underneath the mime.

This is not to say that the stars were mannequins or dead meat. Rather, like a sculptor who reshapes a piece of wood, a star remolded the persona to the project. Cary Grant was always Cary Grant, with that implausible accent, but the Cary Grant of Only Angels Have Wings is not that of His Girl Friday or Suspicion or Notorious or Arsenic and Old Lace. Or compare Barbara Stanwyck in The Lady Eve, Double Indemnity, and Meet John Doe. Young Mr. Lincoln is not the same character as Mr. Roberts, but both are recognizably Henry Fonda.

Dress them up as you like, but their bearing and especially their voices would always betray them. As Mr. Kralik in The Shop around the Corner, James Stewart talks like Mr. Smith on his way to Washington. In The Little Foxes, Herbert Marshall and Bette Davis sound about as southern as I do.

Star acting persisted into the 1960s, with Fonda, Stewart, Wayne, Crawford, and other granitic survivors of the studio era finishing out their careers. Star acting continues in what scholar Steve Seidman has called “comedian comedy,” from Jerry Lewis to Adam Sandler and Jack Black. Their characters are usually the same guy, again. Arguably some women, like Sandra Bullock and Ashlee Judd, also continued the tradition.

On the whole, though, the most highly regarded acting has moved closer to impersonation. Today your serious actors shape-shift for every project—acquiring accents, burying their faces in makeup, gaining or losing weight. We might be inclined to blame the Method, but classical actors went through the same discipline. Olivier, with his false noses and endless vocal range, might be the impersonators’ patron saint. His followers include Streep, Our Lady of Accents, and the self-flagellating young De Niro. Ironically, although today’s performance-as-impersonation aims at greater naturalness, it projects a flamboyance that advertises its mechanics. It can even look hammy. Thus, as so often, does realism breed artifice.

On the whole, though, the most highly regarded acting has moved closer to impersonation. Today your serious actors shape-shift for every project—acquiring accents, burying their faces in makeup, gaining or losing weight. We might be inclined to blame the Method, but classical actors went through the same discipline. Olivier, with his false noses and endless vocal range, might be the impersonators’ patron saint. His followers include Streep, Our Lady of Accents, and the self-flagellating young De Niro. Ironically, although today’s performance-as-impersonation aims at greater naturalness, it projects a flamboyance that advertises its mechanics. It can even look hammy. Thus, as so often, does realism breed artifice.

Horror and comic-book movies offer ripe opportunities for this sort of masquerade. In a straight drama, confined by realism, you usually can’t go over the top, but given the role of Hannibal Lector, there is no top. The awesome villain is a playground for the virtuoso, or the virtuoso in training. You can overplay, underplay, or over-underplay. You can also shift registers with no warning, as when hambone supreme Orson Welles would switch from a whisper to a bellow. More often now we get the flip from menace to gargoylish humor. Jack Nicholson’s “Heeere’s Johnny” in The Shining is iconic in this respect. In classic Hollywood, humor was used to strengthen sentiment, but now it’s used to dilute violence.

Such is the range we find in The Dark Knight. True, some players turn in fairly low-key work. Morgan Freeman plays Morgan Freeman, Michael Caine does his usual punctilious job, and Gary Oldman seems to have stumbled in from an ordinary crime film. Maggie Gylenhaal and Aaron Eckhart provide a degree of normality by only slightly overplaying; even after Harvey Dent’s fiery makeover Eckhart treats the role as no occasion for theatrics.

All else is Guignol. The Joker’s darting eyes, waggling brows, chortles, and restless licking of his lips send every bit of dialogue Special Delivery. Ledger’s performance has been much praised, but what would count as a bad line reading here? The part seems designed for scenery-chewing. By contrast, poor Bale has little to work with. As Bruce Wayne, he must be stiff as a plank, kissing Rachel while keeping one hand suavely tucked in his pocket, GQ style. In his Bat-cowl, he’s missing as much acreage of his face as Dent is, so all Bale has is the voice, over-underplayed as a hoarse bark.

In sum, our principals are sweating through their scenes. You get no strokes for making it look easy, but if you work really hard you might get an Oscar.

A taste for the grotesque. Horror films have always played on bodily distortions and decay, but The Exorcist (1973) raised the bar for what sorts of enticing deformities could be shown to mainstream audiences. Thanks to new special effects, movies like Total Recall (1990) were giving us cartoonish exaggerations of heads and appendages.

A taste for the grotesque. Horror films have always played on bodily distortions and decay, but The Exorcist (1973) raised the bar for what sorts of enticing deformities could be shown to mainstream audiences. Thanks to new special effects, movies like Total Recall (1990) were giving us cartoonish exaggerations of heads and appendages.

But of course the caricaturists got here first, from Hogarth and Daumier onward. Most memorably, Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy strip offered a parade of mutilated villains like Flattop, the Brow, the Mole, and the Blank, a gentleman who was literally defaced. The Batman comics followed Gould in giving the protagonist an array of adversaries who would even raise an eyebrow in a Manhattan subway car.

Eisenstein once argued that horrific grotesquerie was unstable and hard to sustain. He thought that it teetered between the comic-grotesque and the pathetic-grotesque. That’s the difference, I suppose, between Beetlejuice and Edward Scissorhands, or between the Joker and Harvey Dent. In any case, in all its guises the grotesque is available to our comic-book pictures, and it plays nicely into the oversize acting style that’s coming into favor.

You’re thinking that I’ve gone on way too long, and you’re right. Yet I can’t withhold two more quickies:

The global recognition of anime and Hong Kong swordplay films. During the climactic battle between Iron Man 2.0 and 3.0, so reminiscent of Transformers, I thought: “The mecha look has won.”

Learning to love the dark. That is, filmmakers’ current belief that “dark” themes, carried by monochrome cinematography, somehow carry more prestige than light ones in a wide palette. This parallels comics’ urge for legitimacy by treating serious subjects in somber hues, especially in graphic novels.

Time to stop! This is, after all, just a list of causes and conditions that occurred to me after my day in the multiplex. I’m sure we can find others. Still, factors like these seem to me more precise and proximate causes for the surge in comic-book films than a vague sense that we need these heroes now. These heroes have been around for fifty years, so in some sense they’ve always been needed, and somebody may still need them. The major media companies, for sure. Gazillions of fans, apparently. Me, not so much. But after Hellboy II: The Golden Army I live in hope.

Thanks to Hank Luttrell for information about the history of the comics market.

The superhero rankings I mentioned are: Spider-Man 3 (no. 12), Spider-Man (no. 17), Spider-Man 2 (no. 23), The Dark Knight (currently at no. 29, but that will change), Men in Black (no. 42), Iron Man (no. 45), X-Men: The Last Stand (no. 75), 300 (no. 80), Men in Black II (no. 85), Batman (no. 95), and X2: X-Men United (no. 98). The usual caveat applies: This list is based on unadjusted grosses and so favors recent titles, because of inflation and the increased ticket prices. If you adjust for these factors, the list of 100 all-time top grossers includes seven comics titles, with the highest-ranking one being Spider-Man, at no. 33.

For a thoughtful essay written just as the trend was starting, see Ken Tucker’s 2000 Entertainment Weekly piece, “Caped Fears.” It’s incompletely available here.

Comics aficionados may object that I am obviously against comics as a whole. True, I have little interest in superhero comic books. As a boy I read the DC titles, but I preferred Mad, Archie, Uncle Scrooge, and Little Lulu. In high school and college I missed the whole Marvel revolution and never caught up. Like everybody else in the 1980s I read The Dark Knight Returns, but I preferred Watchmen (and I look forward to the movie). I like the Hellboy movies too. But I’m not gripped by many of the newest trends in comics. Sin City strikes me as a fastidious piece of draftsmanship exercised on formulaic material, as if Mickey Spillane were rewritten by Nicholson Baker. Since the 80s my tastes have run to Ware, Clowes, a few manga, and especially Eurocomics derived from the clear-line tradition (Chaland, Floc’h, Swarte, etc.). I believe that McCay and Herriman are major twentieth-century artists, with Chester Gould and Cliff Sterrett worth considering for the honor too.

You can argue that Oliver Stone’s films create ambivalence inadvertently. JFK seems to have a clear-cut message, but the plotting is diverted by so many conspiracy scenarios that the viewer might get confused about what exactly Stone is claiming really happened.

On the ways that worldmaking replaces character-centered media storytelling, the crucial discussion is in Henry Jenkins, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide (New York University Press, 2007), 113-122.

On franchise-building, see the detailed account in detail in Eileen R. Meehan, “‘Holy Commodity Fetish, Batman!’: The Political Economy of a Commercial Intertext,” in The Many Lives of the Batman, ed. Roberta E. Pearson and William Uricchio (Routledge, 1991), 47-65. Other essays in this collection offer information on the strategies of franchise-building.

Just as Star Wars helped legitimate itself by including Alec Guinness in its cast (surely he wouldn’t be in a potboiler), several superhero movies have a proclivity for including a touch of British class: McKellan and Stewart in X-Men, Caine in the Batman series. These old reliables like to keep busy and earn a spot of cash.

PS: 21 August 2008: This post has gotten some intriguing responses, both on the Internets and in correspondence with me, so I’m adding a few here.

Jim Emerson elaborated on the zeitgeist motif in an entry at Scanners. At Crooked Timber, John Holbo examines how much the film’s dark cast owes to the 1990s reincarnation of Batman. Peter Coogan writes to tell me that he makes a narrower version of the zeitgeist argument in relation to superheroes in Chapter 10 of his book, Superhero: The Secret Origin of a Genre, to be reprinted next year. Even the more moderate form he proposes doesn’t convince me, I’m afraid, but the book ought to be of value to readers interested in the genre.

From Stew Fyfe comes a letter offering some corrections and qualifications.

*Stew points out that chain stores like Borders do sell some periodical comics titles, though not always regularly.

*Comics publishing, while not at the circulation levels seen in the golden era, is undergoing something of a resurgence now, possibly because of the success of the franchise movies. Watchmen sales alone will be a big bump in anticipation of the movie.

*As for my claim that film is driving the publishing side, Stew suggests that the relations between the media are more complicated. The idea that the tail wags the dog might apply to DC, but Marvel has made efforts to diversify the relations between the books and the films.

They’ve done things like replacing the Hulk with a red, articulate version of the character just before the movie came out (which is odd because if there’s one thing that the general public knows about the character is that he’s green and he grunts). They’ve also handed the Hulk’s main title over to a minor character, Hercules. They’ve spent a year turning Iron Man, in the main continuity, into something of a techno-fascist (if lately a repentant one) who locks up other superheroes.