Archive for the 'Comic strips and cartoons' Category

Live with it! There’ll always be movie sequels. Good thing, too.

DB:

You’ve heard it before. Facing a summer packed with sequels, a journalist gets fed up. This time it’s Patrick Goldstein in the Los Angeles Times, and his lament strikes familiar chords. Sequels prove that Hollywood lacks imagination and is interested only in profits. Sequel films are boring and repetitious. They rarely match the original in quality. And when good directors sign on to do sequels, they get a big payday but they also compromise their talents.

Me, I want more original and plausible ideas. So, I expect, do you. Time to call in the Badger squad, the ensemble of email pals drawn from various generations of UW-Madison grad students and faculty. I asked them if we can’t understand sequels in a more thoughtful and sophisticated way—historically, artistically, in relation to other media. The result is another virtual roundtable, like the one on B-films held here a few months ago.

There were enough ideas for several blogs, and I’ve regretfully had to drop a whole thread devoted to comics and videogames. Maybe I’ll compile those remarks into a sequel. For now, the participants are: Stew Fyfe; Doug Gomery; Jason Mittell (of JustTV); Michael Newman (of Zigzigger and Fraktastic); Paul Ramaeker; and Jim Udden. I throw in some ideas as well.

Are all sequels in the arts automatically second-rate?

DB: The Odyssey is a sequel to the Iliad, and the second, better part of Don Quixote is a sequel to the first. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy is explicitly a followup to The Hobbit. After killing off Sherlock Holmes in “The Adventure of the Final Problem,” Conan Doyle resurrected him for more exploits. The Merry Wives of Windsor brings back Sir John Falstaff after his death in Henry IV Part II, because, supposedly, Queen Elizabeth wanted to see him again, this time in a romance plot.

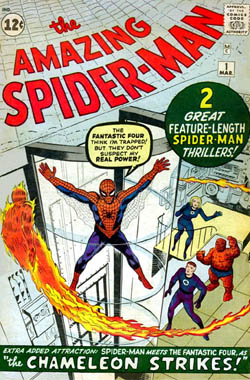

Michael Newman: Sequels exist in all narrative forms–novels, plays, movies, television, videogames, comics, operas. What is the Bible but a series of sequels? Didn’t Shakespeare follow up Henry IV with a part II? What of Wagner’s Ring Cycle and Updike’s Rabbit novels? Many novelists of high reputation have written sequels, including Thackeray, Trollope, Faulkner, and Roth. There is nothing intrinsically unimaginative about continuing a story from one text to another. Because narratives draw their basic materials from life, they can always go on, just as the world goes on. Endings are always, to an extent, arbitrary. Sequels exploit the affordance of narrative to continue.

What about film sequels? What’s their track record?

DB: Goldstein grants the excellence of Godfather II, but what about Aliens, The Empire Strikes Back, Toy Story 2, and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (arguably the best entry in the franchise)? We have arthouse examples too, provided by Satyajit Ray (Aparajito and The World of Apu), Bergman (Saraband as a sequel to Scenes from a Marriage), and Truffaut (the Antoine Doinel films). If we allow avant-garde sequels, we have James Benning‘s One-Way Boogie Woogie/ 27 Years Later. As for documentaries, what about Michael Moore’s Pets or Meat?, the pendant to Roger and Me?

The world of film would be a poorer place if critics had by fiat banned all the fine Hong Kong sequels, notably those spawned by Police Story, A Better Tomorrow, Drunken Master, Once Upon a Time in China, Swordsman, and so on up to Johnnie To’s Election 2 and Andrew Lau’s Infernal Affairs 2. And arthouse fave Wong Kar-wai hasn’t been shy about making sequels.

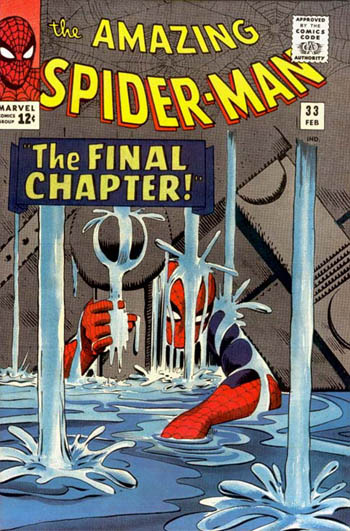

Stew Fyfe: Other sequels of quality: The Bride of Frankenstein, Mad Max II (The Road Warrior), Spider-Man 2, X-Men 2, Dawn of the Dead, Sanjuro, Quatermass and the Pit. Personally, I’d also add Blade 2, Babe 2 and The Devil’s Rejects, but I’m sure those are arguable. Would The Limey be a sequel to Poor Cow? Del Toro speaks of Pan’s Labyrinth as a companion piece or “sister-film” to The Devil’s Backbone. If you want to include docs, there’s always the Up series.

Why are there film sequels in the first place?

DB: Most film industries need to both standardize and differentiate their products. Audiences expect a new take on some familiar forms and materials. Sequels offer the possibility of recognizable repetition with controlled, sometimes intriguing, variation. This logic can be found in sequels in other media, which often respond to popular demand for the same again, but different. Remember Conan Doyle reluctantly bringing back Holmes, and Queen Elizabeth asking to see Sir John in love.

Doug Gomery: Sequels happen because the studio owners have never figured out any business model to predict success. If #1 is popular, perhaps #2 will be almost as popular. Until recently, producers seldom expected the followup’s revenues to equal the first. The basics were keep costs low, keep risks low, and make a profit. Maybe not a large as the breakthrough initial film—but at least a profit.

But they’re not a contemporary development. As part of the Hollywood studio system, they have existed in all eras—the Coming of Sound, the Classical Era, and the Lew Wasserman era. They surely seem to be surviving Wasserman as well. Indeed, as much as I admire Wasserman, who can defend Jaws 2 and its successors?

In the classic era, it may seem that there were fewer sequels as such, but there was a variant called rewrites in another genre. Years ago as I did my first book, a study of High Sierra, I watched Colorado Territory with something close to awe. It’s a gangster film turned western almost line by line. After all, Warners owned the literary rights: why not recycle it?

Given the mercenary impulse behind sequels, does a director’s willingness to make one mean that he or she has sold out?

Goldstein: “Look at the great talent who’s on the sequel beat: Steven Soderbergh has done two Ocean’s sequels. Bryan Singer, the wunderkind behind The Usual Suspects, has done X-Men 2 and is at work on a sequel to Superman Returns. Christopher Nolan has left behind the raw originality of Memento to do Batman movies. Robert Rodriguez, who burst on the scene with El Mariachi, has done two sequels for Spy Kids, with a Sin City sequel on its way. After making Darkman and A Simple Plan, Sam Raimi seemed poised to be our generation’s dark prince of meaty thrillers but has turned himself into an impersonal Spider-Man ringmaster instead.”

Paul Ramaeker: To assume that the Spider-Man films must necessarily be less personal than Darkman or A Simple Plan (both of which are heavily indebted to the strictures of their genres) is to perpetuate a culturally snobbish perspective on comic books. I’ve not seen S-M3, but Raimi is a genuine fan of the character, a character with a long and complex narrative history, and given the way S-M2 continues and develops threads from the first film, I see no reason to assume he didn’t have some artistic investment in presenting his interpretation of the character over 3 films (or however many) to present a larger “story” about the character. Why should this not be seen as “personal” filmmaking to the same extent as any other kind of adaptation?

Moreover, speaking as a Soderbergh fan: I may not like Ocean’s 12 as much as Ocean’s 11, but it seems like an experiment made in good faith to me. It is a stranger movie than you would think from the way it gets picked up in articles like Goldstein’s. In fact, the way it plays with audience expectations is both dependent upon familiarity with the first film, and radically divergent from it- in many ways, it does the exact opposite of what sequels are supposed to do, which is to provide a “cozy” (Goldstein’s word) repetition of familiar pleasures. Perhaps it failed (again, I remain sort of fond of the film, which I think was best described as being like an issue of Us Weekly as put together by the editors of Cahiers du cinéma), but even so I think you’d have to call it a failed experiment rather than a rehashing.

Stew Fyfe: At a guess, I’d say that audiences or critics might evaluate the worthiness/mercenary nature of sequels by asking three questions:

(1) Has the sequel been made because there’s more story to tell?

(2) Has the sequel been made because the characters are great and people want to see them again?

(3) Has the sequel been made because there’s more money to be made?

Obviously, any combination of all three can be answered in the affirmative for any sequel and presumably the sequel wouldn’t get made if the answer to (3) was No. But with something like The Two Towers, (1) gets priority, while with Pirates 2 + 3, (3) nudges out (2). Even with (3), money, as the primary motivation, one could still make a good film. The suspicion of milking the franchise just makes the movie an easier target for critics.

Do sequels automatically equal predictability?

Jason Mittell: The line that most interests me in Goldstein’s piece is the last: “When it comes to entertainment, I’ll take excitement and unpredictability over familiarity every time.” This sets up a false dichotomy between the known and the unknown. As David and I both blogged about a few months ago, knowing a story doesn’t preclude suspense and excitement (and for some viewers, it might actually enhance it). And arguably knowing a storyworld actually allows for greater opportunities for excitement and unpredictability – a film/episode/entry in any series that doesn’t need to spend much time introducing already-established settings, characters, conflicts, etc. can literally cut to the chase. Think of the second Bourne film as a good example, or Spider-man 2 as a chance to deepen character once basic exposition is accounted for.

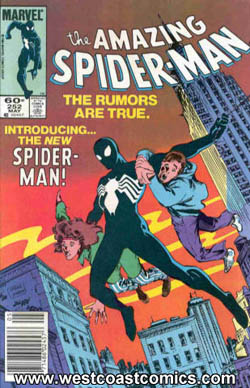

Paul Ramaeker: I have a theory. In the contemporary comic-book blockbuster, the sequels will always be better than the first entries. Spider-Man 2 is better than Spider-Man, X-Men 2 is better than X-Men, and I will bet that The Dark Knight will be better than Batman Begins, just as Batman Returns was better than Batman. The pattern seems to me to be that the first film in the series is relatively impersonal—the franchise must be established as a franchise, meaning that few boats will be rocked, and the director must prove that they can handle both a film on that scale, and can be trusted with the property with all the investment it represents.

But once they’ve done so, in the above cases where the first films enjoyed significant economic (and critical) success, the directors are given a bit more leeway, are allowed to drive the family car a little further and a little faster. In each case, the second film in the series by the same director has been significantly more idiosyncratic. Batman Returns has much more of Burton‘s sense of humor and interest in the grotesque; X-Men 2 is a much more serious and ambitious film narratively and thematically, more obviously the product of a prestige filmmaker (Singer’s never been an auteur by any stretch, so that will have to do). Spider-Man seemed sort of anonymous in terms of style, but Spider-Man 2 had a much more extensive and playful use of classic Raimi techniques: short, fast zooms; canted angles; rapid camera movements; whimsical motivations for techniques, like the mechanical-tentacle POV shot (virtually a repeat of his flying-eyeball POV from Evil Dead 2).

Who knows what The Dark Knight will be like, but I’m prepared to put money on the claim that it will have something to do with how people construct elaborate narratives around themselves to explain, justify, or obscure their actions and motives.

Are sequels part of a larger trend toward serial narrative?

DB: We can continue a story in another text within the same medium, but we can also spread the storyline across many platforms—novels, films, comic books, videogames. Henry Jenkins has called this process transmedia storytelling.

Michael Newman: Compared with literary fiction, there seems to be a strong propensity toward the never-ending story in genre storytelling like sci-fi and fantasy and superhero comics and spy novels and soap operas. Much of the cinematic sequel storytelling today might be considered as this kind of serialized genre storytelling. Such serials tend to have a low aesthetic reputation in comparison to more respectable genres. (The cinematic comparison would be summer blockbusters vs. fall Oscar bait.) Serial forms have historically been associated with children (e.g., comic books) and women (e.g., soaps). In other words, there is cultural distinction, a system of social hierarchy, at play.

Stew Fyfe: Yes, the longer-standing comics universes have made regular use of serial continuity to forge after-the-fact connections. It’s a form of what fans call retcon or “retroactive continuity.”

Sci-fi writer Phillip Jose Farmer used a similar concept, the “Wold Newton family” to link various mystery, pulp, crime, sci fi, adventure and spy fiction characters (so that Sherlock Holmes, Doc Savage, Sam Spade, The Shadow, Captain Blood and James Bond, among others, all become linked). Alan Moore did something similar with The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, and Warren Ellis in Planetary. More limited filmic examples of this might be Zatoichi vs. Yojimbo, or Enemy of the State (which more or less sticks The Conversation‘s Harry Caul into a Bruckheimer film). There’s Freddy vs. Jason, which very adroitly observes and incorporates the continuities of two long-standing, mostly dormant franchises. In television, there’s that whole, rather insane St. Elsewhere continuity thing.

In the current crop of movie sequels featuring superheroes, one thing that has been noticeable is the casting of minor characters who might serve as springboards for later storylines. We’ve seen Dylan Baker play Dr. Connors in two Spidey films, for example, so if they decide to go with The Lizard as a villain in one of the later films, they’ve already set him within the film series’ continuity. Aaron Eckhart’s casting as Harvey Dent in The Dark Knight could similarly be used to set up Two Face as a villain for film 3.

This is similar to the idea of leaving a film “open for a sequel,” but it seems more closely integrated into the planning and execution of the film. It also points to a middle ground between the “We’re going into this making three unified films” model (Lord of the Rings) and the “We can make more money, so let’s see what plot elements we can build off of” (Pirates of the Caribbean). This is more of a “We’re probably going to make more films, let’s give ourselves something to work with” model.

It also raises the question, I guess, if you want to start speaking of dangling causes extending past the end of a film, or in the case of Pirates, the conversion of plot elements into something like dangling causes. In Pirates 1, we hear of Bootstrap Bill Turner getting chained to a cannonball and shot out into the ocean, but wasn’t it after he was made immortal by the curse of the Aztec gold? I guess you could call this a retroactive cause. Or, noting the similarity to “retcon,” a “retcause.” Never mind, that sounds lame.

Michael Newman: In the contemporary era of media convergence, serialized storytelling is becoming a mainstay across media and genres. Serial narratives supposedly facilitate spreading franchises out across multiple platforms. The media franchise demands long-format storytelling that can be spun off in multiple iterations. The rise of sequels is a much larger issue than a bunch of directors trying to make lots of money or audiences having unadventurous tastes–sequel/serial franchises are a central business model in the media industry today, supported and encouraged by the structure of conglomeration and horizontal integration.

The real point of the LAT article is that Hollywood is all commerce and no art, and sequels are a symptom. But this is such old news. And to connect it to a Squeeze summer tour is really stretching.

Jason Mittell: I think Michael’s cross-media point is crucial – continuity of a narrative world is a core part of nearly every storytelling form, but the language of “sequel” is applied predominantly to film. “Series” seems a more respectable term, as it suggests an organic continuity rather than a reactive stance of “Hey, let’s do that again!”

Are some serial/ sequel forms better suited to different media?

Jason Mittell: I think the LAT article is ultimately trying to valorize cinema’s potential to introduce something new, in reaction to the presumed rise of legitimate and praised series narratives on television (The Sopranos, Six Feet Under, Lost, etc.). And perhaps he has a point. Maybe film should stick to presenting compelling stand-alone short stories, since television has emerged as the leader in narrating persistent worlds? Or maybe I’m just saying that to pick a fight…

Jim Udden: I disagree that films should stick with one-off feature-length productions and leave ongoing series work to TV. Television has long had its Made for TV Movies, so why shouldn’t cinema think more in terms of series than it does? After all, if these are truly hard times for the film industry, as we’re always told, doesn’t it make more economic sense to adapt, just as TV has done in the last couple of decades?

True, there are things that cannot be matched on either side. I cannot imagine any film ever matching the daunting complexity of Deadwood or The Wire. Then again, some things work best as a stand-alone concern. Try to imagine a sequel to Pan’s Labyrinth or Children of Men, or try to imagine either film being made only for TV, for that matter. Moreover, some sequels should never be made. (Remember 2010?) On the other hand, some films would have been better off had they been pitched as an HBO series. (Syriana comes to mind.)

Yet film has proven its ability to take on a series format even when it is not called that. In a sense the oeuvres of most of the great art cinema auteurs are series of sorts. Aren’t Tati’s films a series with the ongoing presence of Hulot (or Hulots, if we include the false ones in Play Time)? And does anybody castigate Wong Kar-wai for following up Chungking Express with Fallen Angels, or In the Mood for Love with 2046, which are not series, but mere (gasp!) sequels? Clearly these examples were based not just on aesthetic visions, but on banking on previous success. Why do we give them a pass, but not more mainstream fare?

I think the more closely we look, the more we might find there are series and sequels even if they are not tagged by those names. It does happen in documentary, and not just in the 7 Up series. For example, American Dream does seem to me to a continuation of Harlan County USA, if not an outright sequel. Bowling for Columbine and Fahrenheit 9/11 combined make for a more complex argument about the relation of the defense industry to class issues than each one does on its own.

In other words, none of these formats has any value on its own. Everything depends on the type of stories to be told and the talent and economic wherewithal to find the best format for that story (or argument). The most appropriate format could be just a two-hour film, or it could be a television series going on for years. Or it could be something in between, such as the first two Infernal Affairs films, which got clumsily condensed into one film in The Departed. Both television and film can equally participate in such in-between formats.

DB: I don’t agree with all of these arguments and opinions, and I don’t expect you to either. The point is that compared to journalists’ rote dismissal of sequels, these writers offer more stimulating and more probing arguments. These guys are researchers and teachers, and they offer detailed evidence for their claim. They also write clearly, a point to remember when people say that film academics always talk in jargon and pontificate about gaseous theories.

To end on an upbeat note, I note that some journalists avoid the conventional wisdom. Consider Manohla Dargis’ recent and welcome defense of the blockbuster. Her case doesn’t seem to me spanking new: the artistic possibilities of the format have been defended for several years by film historians, as well in Tom Shone’s lively 2004 book Blockbuster. (1) Still, in the pages of the good, gray Times, Dargis’s piece remains something of a breakthrough. Maybe some day the paper will host a defense of sequels as well. If so, consider this communal blog a prequel.

(1) A sample, with Shone responding to the charge that the ’70s blockbuster drove out ambitious American filmmaking: “Any revolution that left it difficult for Robert Redford to make a movie as self-importantly glum as Ordinary People can be no bad thing” (Blockbuster, 312).

PS 30 June: Jason Mittell continues the conversation by contesting another journo’s claim that the public is tiring of sequels this summer.

An appetite for artifice

Offscreen (Christoffer Boe)

DB here (no, not above):

Catching up with several of the fall’s films, I was struck by how often they played quite self-consciously with the overall shape of their plots. Here are some examples.

Network narratives. This is the label I applied in The Way Hollywood Tells It to those films highlighting several protagonists inhabiting distinct, but intermingling, story lines. In Poetics of Cinema, I have an essay examining the conventions of this format. Several films I saw this fall continued this tradition.

*Bobby used the familiar device of gathering everyone in a single spot–a hotel–within a short time frame and interweaving personal stories with a fateful climax. I thought the film was fairly clumsy, but I was still moved. In 1964 I filmed RFK when he stumped our town for the presidential nomination, and in college, though leaning toward Gene McCarthy I thought Bobby was the only candidate who could beat the Republicans. “Dump the Hump!” (Hubert Humphrey) was the rallying cry.) His assassination, during the same year Martin Luther King was killed, was very traumatic to young idealists. Estevez’s film becomes most powerful, I think, by simply replaying footage and speeches, reminding us that there was once a rich politician who talked incessantly about helping the poor. Just as Stone’s JFK positioned Jack as the man who could have averted the Vietnam War, Bobby makes RFK the anti-Bush.

*Fast Food Nation was for me a more satisfying use of the network narrative format. Here the time scheme is more diffuse because Linklater is tracing a large-scale process, the burger from the hoof to the Happy Meal. By starting with the middle-management character (Greg Kinnear) and then easing us into the harsh working life facing Mexican illegals, the film builds sympathy for the immigrants. Gradually, the illegals’ stories take over, and the social conscience of one of the burger chain’s teenage workers is ignited.

The plotting makes some thoughtful moves. A more literal approach would have shown us the meat-processing plant’s killing floor early, as part of the step-by-step process. But here the shocking material isn’t presented until the very climax of the film, as the fate to which the immigrant working woman must submit. Likewise, the film drops the Kinnear character about halfway through, a ploy that conceals from us how he’ll act on his new knowledge. Will he blow the whistle on the plant, and endanger his job? A European film might have left his whole line of action open, but Linklater adheres to the tendency of American films to resolve a plotline one way or another. He does it, however, in an epilogue which leaves us with a sharpened sense of the acute problems of the system.

*The Uchoten Hotel (aka Suite Dreams, Japan, 2006). In the vein of Tampopo and Shall We Dance?, Mitani Koki offers gentle humor mixed with satiric social observation. Confusion reigns at the Avanti Hotel on New Year’s Eve, as a philandering professor, a corrupt Senator, low-end showbiz types, and the hotel staff become embroiled in one another’s lives. Lively long takes display subtle staging, and there’s a ventriloquist’s duck. A tribute to Grand Hotel, Billy Wilder, and Jacques Tati, this good-hearted survey of human aspirations was the most uncynical movie I saw all year.

Many critics seem to feel that the network format is tired out. At indieWire, Nick Schager calls for “a moratorium on second-rate Nashville-style ensemble pieces that seem increasingly to be the province of every Tom, Dick, and Emilio.” The key words are “second-rate”: Like any storytelling pattern, the network option can be used well or badly. Linklater and Mitani use it with flair.

The point I’d stress is that although the network model can claim to be a realistic device (in our world, our projects commingle), it’s almost always presented through a series of conventions–traffic accidents, people brushing past each other, narration that holds back information about the characters’ relationships, and so on. We recognize these as part of the artifice in this tradition of storytelling.

Broken Timelines. During his DVD commentary for Basic, John McTiernan uses this phrase to explain the film’s flashbacks and replays. In the terms we use in Film Art, the linear story action is scrambled or rearranged in the plot that that the film presents to us.

Screenwriters used to urge novices to avoid breaking up the timeline, but in the 1940s through the mid-1950s, films began to play around with story order. Citizen Kane (1941) probably encouraged the flashback form, as did film noir’s emphasis on mystery and crime detection. Siodmak’s fine The Killers offers a prototype. (I discuss its plot maneuvers in Narration in the Fiction Film.)

We don’t lack for flashbacks in contemporary films, but things are getting complicated. Today a film may open with a quite mystifying sequence, before backtracking to acquaint us with the situation. In itself, this isn’t very unusual, since flashback-based films have often opened at a point of crisis and then taken us back to the beginning of the action. The Big Clock and Written on the Wind are instances. The new wrinkle is to actually replay the opening situation or just the images from it in a new context.

*The Fountain by Darren Aronofsky offers one example. Using three time layers, it can keep replaying the opening portions in ways that recontextualize the material we saw at first. In its out-of-this-world realm, as well as its suggestion that the story is in some sense being written as we see it, it reminded me of Slaughterhouse-Five (1972)–another indication that these innovations aren’t brand new.

*Another instance: The opening image of Christoffer Boe’s Offscreen (2006), with a bloody Nicolas Bro in close-up advancing to the camera, gets explained only at the grisly climax.

*The recontextualizing replay isn’t an avant-garde device. Tony Scott’s well-done thriller Déjà Vu uses it in the context of a time-travel plot. It replays the opening sequence in a way that suggests both a branching or alternative future and a deeper understanding of what we saw initially. A similar pattern is found in Flags of Our Fathers, in which we reinterpret the opening differently now that we know the characters more fully. I suppose that Pulp Fiction‘s opening became a powerful influence on this formal choice.

When an action is replayed, it can be shown from different characters’ perspectives. Again, this was explored a lot in the 1940s, as in Mildred Pierce (a replay of the opening) and Crossfire (a replay of the crucial incident). The device is on display in The Killing and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance as well. Kurosawa’s Rashomon made the technique more ambiguous, by not confirming which version of events is accurate. The same idea guides the money exchange in Tarantino’s Jackie Brown, which we discuss in the new edition of Film Art.

*The broken timeline of Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada uses multiple points of attachment mildly, in the murder scene. The replays are more significant and fragmentary in The Prestige. More films in this vein are in preparation, including Vantage Point, which shows an assassination attempt on a US president as seen from five characters’ points of view, “unfolding in 15-minute increments.”

Companion films. Back in the 1960s, Fox announced that it wanted to make Tora! Tora! Tora! with two directors, one Japanese and one American. My friends and I indulged in a game: Whom should they pick? (I favored Ozu and Samuel Fuller.) As you probably know, Kurosawa’s collaboration came to naught (though he did shoot some footage, discussed by Richard Fleischer in his book and his DVD commentary on the film). Fukasaku Kinji and evidently some other directors contributed to the Japan-based footage.

Now, instead of one film with two directors, Clint Eastwood gave us two complementary films from a single hand. I haven’t yet seen Letters from Iwo Jima, but the very idea of showing the same battle from opposite sides in two movies acknowledges a level of artifice.

The French got here first, I think. Marguerite Duras made a companion film to her mesmerizing India Song (on right) called Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta desert. Son nom had exactly the same soundtrack as India Song but a wholly different image track–only landscapes around the site of action, empty (as I recall) of all human presence. A comparable instance is the alternate-worlds pairing by Alain Resnais, Smoking/ No Smoking, adapted from a cylce of Alan Ayckbourn plays.

The French got here first, I think. Marguerite Duras made a companion film to her mesmerizing India Song (on right) called Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta desert. Son nom had exactly the same soundtrack as India Song but a wholly different image track–only landscapes around the site of action, empty (as I recall) of all human presence. A comparable instance is the alternate-worlds pairing by Alain Resnais, Smoking/ No Smoking, adapted from a cylce of Alan Ayckbourn plays.

The companion-film concept seems to be expanding. Red Road, directed by Andrea Arnold, is launching a series of films to based in Scotland and all featuring the same group of characters, but filmed by different directors. The characters are conceived by filmmakers Lone Scherfig (Wilbur Wants to Kill Himself) and Anders Thomas Jensen (Brothers). In a way, a sort of episodic-television idea applied to feature films.

What’s behind this? Why are today’s movies using such self-conscious artifice in their plotting? Is form the new content, the way gray is the new black?

Complex storytelling can be found in a lot of other media today. It’s common to point to Hill Street Blues and later TV shows as reinforcing tendencies toward network narratives in film. Jason Mittell discusses the tendency in Velvet Light Trap no. 58. His article “Narrative Complexity in Contemporary American Television” (available here), makes the case that shows like 24, Arrested Development, Buffy, Malcolm in the Middle, and so on have offered viewers ways “to be actively engaged in the story and successfully surprised through the storytelling’s manipulations”–a good way to describe some of the strategies I’ve been sketching.

In graphic novels and comic art we’re seeing the same tendencies. Daniel Clowes and Chris Ware manipulate time and space in virtuoso ways, as does the highly formalized movement known as OuBaPo. You can check out an American version of OuBaPo in Matt Madden’s 99 Ways to Tell a Story.

In graphic novels and comic art we’re seeing the same tendencies. Daniel Clowes and Chris Ware manipulate time and space in virtuoso ways, as does the highly formalized movement known as OuBaPo. You can check out an American version of OuBaPo in Matt Madden’s 99 Ways to Tell a Story.

In Everything Bad Is Good for You, Steven Johnson argues that people are just getting smarter, and so popular culture is pitched at a more sophisticated level. But quite complex artifice can be found in mass media of earlier eras. As I mention in The Way, we can find backward-told stories in popular fiction long before Memento, and Grand Hotel is an early prototype of the network narrative. Our ancestors weren’t necessarily dumber than we are, and popular art has long harbored experimental impulses.

I’d hypothesize some other causes. Regardless of IQ, more members of the audience have been to college today than in early eras. More of the creators have studied modern art and literature and are ready to borrow experimental devices they’ve encountered in other media. This process has a familiar ring. American filmmaking has often renewed itself by absorbing all manner of experiment, from German Expressionism (for 1930s horror films) to serial music (for 1950s psychological dramas). Usually, I feel compelled to add, the experimental devices are absorbed into existing forms, like classical script structure, genres, or stylistic principles.

I suspect as well that the new genre hierarchy that emerged in the last couple of decades cranked up the artifice level. The rise of science fiction, mystery, fantasy, horror, and comic-book movies probably encouraged clever juggling with story order, point of view, and states of knowledge. So did the rise of indie cinema, which needs narrative innovation to set itself apart from the mainstream. Again, Pulp Fiction fuses the two strands: an indie neo-noir that attracted attention through its bold manipulation of story/ plot relations.

At the same time, filmmakers in other countries have been eager to push the boundaries. Many of the broken-timeline devices have their sources in art cinema of the 1950s and 1960s. Younger European directors like Boe and Tom Tykwer (Run Lola Run) have revived this adventurous attitude toward storytelling, putting them somewhat in sync with American directors. Asian experimentalists like Wong Kar-wai and Hou Hsiao-hsien continue to exercise a comparable influence.

We need to think more about where this impulse toward innovation comes from and how it shows itself, but it seems likely that the flourishing trade in self-conscious storytelling will be with us for some time yet. Hollywood cinema has long been self-consciously, almost fussily formal, and it has a vast appetite for artifice.

Lotsa pictures, lotsa fun

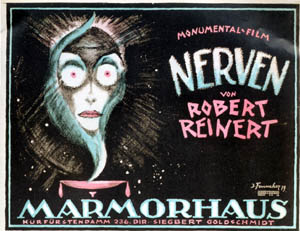

1. “It hypnotizes the viewer,” writes Paul van Yperen of the Nerven poster he printed in the new issue of the Dutch journal Skrien. Paul sent it to me because I wrote about Robert Reinert’s film in my forthcoming collection of essays, Poetics of Cinema. Nerven is a disorienting, highly experimental work. Released in 1919, before The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (early 1920), it might have become a prototype of German Expressionist cinema if it had been widely seen and preserved by archives. Nerven, along with Reinert’s other major film Opium (1919) would make a wonderful twofer on a DVD release.

2. We’ve set up an archival supplement to our textbook, Film Art: An Introduction elsewhere on this site. It includes analyses that appeared in earlier editions but were cut for reasons of space or film availability.

The pieces discuss Stagecoach, Hannah and Her Sisters, Desperately Seeking Susan, Day of Wrath, Last Year at Marienbad, Innocence Unprotected, Disney’s Clock Cleaners, Tout va bien, High School, and Hitchcock’s first Man Who Knew Too Much. DVD has made nearly all of these films easily accessible, so we hope reviving the essays will be of use to students and free-ranging viewers.

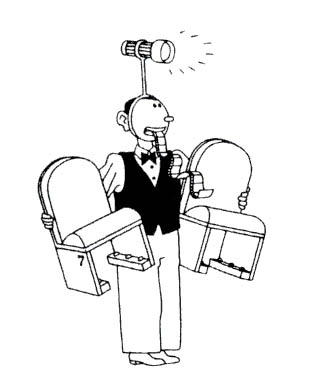

3. Check out the nifty interview with Joost Swarte in the new issue of The Comics Journal. Excerpts are here.

Swarte is the greatest heir to the Belgian-Dutch “clear-line” style, and his witty cartoons have become worldwide classics. Kristin and I have been collecting Swarte books and posters since the 1980s, although as his projects have expanded to building design his output of images has waned (except for the occasional item for The New Yorker).

Swarte has much to say about Hergé’s mastery of visual storytelling, claiming that the Tintin tales are like little movies.

Swarte has much to say about Hergé’s mastery of visual storytelling, claiming that the Tintin tales are like little movies.

He was very much influenced by cinematographic laws. Where do you place your camera? Is the hero always coming from the left? What’s the relation between foreground and background? All sorts of terms that he used come from cinema.

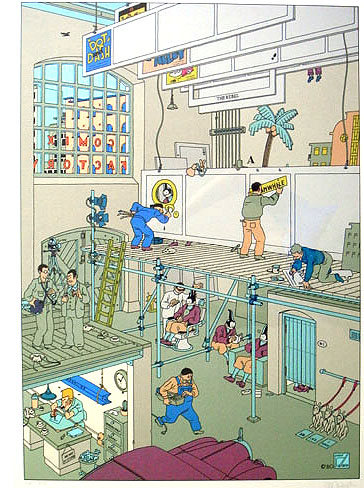

Swarte too has an affinity for film. One of his best pictures, Comic Factory, treats cartooning as if it were moviemaking. Our cartoonist labors in lower left, the girder of a deadline hanging above him, while a producer (with cigar) seems to be telling the photographer how to shoot the panels. Jopo de Pojo gets spruced up for his close-up while his doubles (or clones) lounge around. Set designers and scene painters labor over the panels.

Swarte’s teeming street scenes, usually including dog turds, are filled with glimpsed gags in the manner of Tati. Not surprising, then, that under the skilful questioning of David Peniston, he confesses his admiration for Play Time. New collections of Swarte’s comics are apparently forthcoming, in several languages, in 2007. By the way, the same issue of the Journal has a nice appreciation of Cliff Sterrett, another comics genius, creator of the amiable, lovely, and quite nuts Polly and Her Pals. Click here for a nice blow-up sample.

4. Speaking of cinema in still images: One of Eisenstein’s favorite pastimes was to find anticipations of film in earlier media. He loved the fact that Myron’s discus thrower was portrayed in an impossible position, with the limbs indicating different phases of the action.

This and similar items were inspirations for the plate-smashing scene in Potemkin.

So in a holiday spirit, I’d ask: what would Eisenstein have made of this painting, which I saw again last summer in London’s National Gallery–Botticelli’s Mystic Nativity of 1501?

Reproduction, especially this tiny, doesn’t do the picture justice, but you should be able to see how the symmetry of the composition is broken by the slope up to the central scene of Mary and the mule bending over the baby. As with Swarte cityscapes, there’s a lot to dig for. Angels on left and right of the manger direct the Magi to the main action, and in the lower section angels kiss men while devils dive into the fissures of the earth.

Key for students of cinema, though, is the whirling dance of the angels in the upper third of the picture. Strictly speaking, they all seem out of step, no two in sync. But then you notice that each is executing a slightly different phase of one continuous movement, as if Muybridge had captured a single dancer’s circling trajectory with his early stop-motion photography. Angel Locomotion, he might have called it; but Botticelli got there before him.

Milwaukee: Philosophers turn arty

Today the Virginia senatorial campaign seems to revolve around whether you reveal yourself to be a bad person if you write a novel with disturbing or naughty scenes. It’s the sort of question routinely considered, more dispassionately, by the members of the American Society for Aesthetics. The Society consists mostly of professors, mostly of philosophy, who try to understand the most basic principles of how art works. I’ve been at their annual conference in Milwaukee since Wednesday night.

The Milwaukee Hilton Hotel

The event is held in the Hilton, an opulent building finished in 1928 (that is, just before opulence went away for quite a while). It’s an overpowering, somewhat eerie place, a little like the hotel in The Shining. Chandeliers hang from high ceilings. Corridors stretch on forever, silent and empty. Around any corner you may find a painting, a throne, or a signpost pointing you in several directions. You don’t exactly get lost, but the sheer size of the place, along with the occasional touch of Midwestern kitsch, suggests Last Year at Marienbad redecorated to suit the Amberson family. The same aesthetic principles, blown out to a more humungous scale, gave us The House On The Rock, one of Wisconsin’s great contributions to grassroots Dada.

In my first day here, there were intriguing papers and discussions. I couldn’t go to all of them, but I did visit a session on artistic genius. Peter Kivy’s paper, “Mozart’s Skull,” argued that an artist we acclaim as a genius raises some problems for ordinary mortals. Genius disturbs us, especially genius in very young people, like the prodigy Mozart. Genius is also very mysterious; we don’t know how someone like Mozart could produce so much music of such high quality—indeed of perhaps the highest quality in the Western art-music tradition.

Kivy believes, as I understood it, that genius is a real quality that we can’t explain by trends in taste or strategies of careerism. He castigated what he called “political deconstructionists” who want to deny that genius exists. In his account, they try to show that praise for gifted artists is actually PR: the reputation is constructed by historical circumstances and has nothing actual at the center. Kivy insisted that, regardless of how his career was promoted, Mozart was truly gifted by orders of magnitude beyond nearly all composers. So how to explain those gifts?

Kivy suggests that genius is a mystery that we may never be able to solve. He compares his argument to one floated by philosopher Colin McGinn, who suggests that consciousness is the sort of problem that we may never resolve, because it’s just not in the cards for creatures like us. That’s not to say that the explanation would be supernatural, as if, say, Mozart was truly kissed by God. (The play and movie, Amadeus, use his middle name to play with this possibility.) Maybe there are non-supernatural factors that create a genius; but we might not ever be able to detect them.

The questions raised in the discussion period were fascinating, with a couple of people saying that one could study how Mozart’s reputation was constructed through social institutions of the time without denying that the basis of the reputation was the genuine excellence of the music. Another listener pointed out that Mozart’s reputation is something of a special case. He was praised and understood instantly, but the music of the late Beethoven puzzled people who had acclaimed his earlier work; it took later generations to see the “genius” embodied in the Ninth Symphony and the late string quartets. Maybe the standard of genius does indeed change with time.

I began to muse over whether we cinephiles ever talk about great filmmakers as true geniuses. Even the directors that are most admired across film history—Renoir, Ozu, Welles, Hitchcock, Dreyer, Eisenstein, Hitchcock, etc.—don’t usually get called “geniuses.” Perhaps this way of talking about artists is part of a classical-art tradition that film never joined…or came too late to join.

A longer session was devoted to comments on my old friend Paisley Livingston’s book Art and Intention. I’ve mentioned this book elsewhere on this site, and it seems to me a remarkable attempt to show how an idea of intentional action can help explain creative processes in art. For students of film, his ideas about collective artistic creation—several people pooling efforts to make a film or some other work—are particularly interesting. In this panel, several other distinguished philosopher of art analyzed, praised, and criticized the views expressed in the book.

That night, after my own talk on early CinemaScope, we went to a reception at the lovely Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design. (Animator Bill Plympton will be visiting it soon.) Across the evening, I met several people keenly interested in cinema–actually, who isn’t? Our talk about movies went on for a long time, continuing in a pub in the hotel. There was a reunion of former Madison philosophy students, all protégées of Noel Carroll, and it was fun to talk movies with them. I don’t think I convinced them that Tom Cruise and Keanu Reeves are excellent screen actors, though they were more sympathetic to my case for Sandra Bullock.

Next day I skipped the ASA sessions to go book-hunting with Paisley. Among other stops, we visited the Renaissance Bookstore, another Wisconsin monument. Several stories high, the collection of old books and magazines is monumentally daunting. This is where all books go to die, in dust. Still, I found mysteries by my new passion, George V. Higgins. Earlier that day, I picked up Scott McCloud’s Making Comics, which looks like a worthy successor to his superb Understanding Comics and his followup, Reinventing Comics. Film scholars can learn a lot from comic art (graphic novels, comic strips, etc.), and McCloud is the best guide to the aesthetics of comics I know. Come to think of it, he should be invited to the next ASA convention. . . .