Archive for the 'Criterion Channel' Category

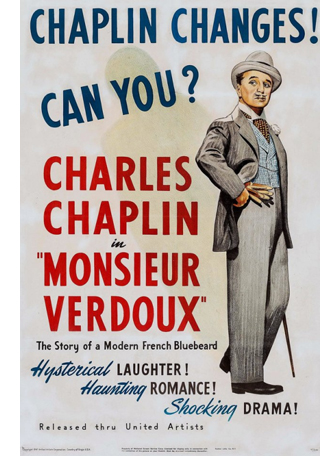

MONSIEUR VERDOUX: Lethal Lothario

DB here:

The newest installment of our Criterion Channel series on FilmStruck is now up. There I try to look at Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux (1947) from a fresh perspective: as a perverse contribution to the serial-killer cycle of the 1940s. You can sample it on the Criterion blog.

The killers inside them

When we say that we take up a new perspective on a film, or any artwork, what are we doing? I think the process involves at least two things. First, you need categories, some fresh conceptual groupings that allow for a perspective shift. Second, you relate the film in question to other particular films—that is, you pick prototypes of the categories. People don’t realize, I believe, the extent to which picking prototypes shapes our reasoning about nearly everything. (Is your prototype of a horror film Cat People, Halloween, or Saw? You’ll think of the genre differently.)

Take film noir. The category didn’t exist in 1940s Hollywood; no producer or director or writer set out to make a noir. A film might be a thriller, crime melodrama, even a horror movie. I discuss the elasticity of these categories here. When French, then American critics started talking about film noir, they were creating a perspective shift. The new category “film noir” pulled together several aspects of films that hadn’t seemed so salient in their day: skepticism about orthodox authority, for example, or suspicion of women’s sexuality. Similarly, the critics elevated certain films, like Double Indemnity and The Big Sleep and Possessed, to the status of prototypes, and less vivid examples were situated in relation to them.

Something like this perspective shift occurred to me when I was writing my book, Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. I tried to come up with some categories that could show continuity and change in film narrative of the period. I looked for strategies of plotting and narration that cut across received categories like genre. Among the categories I explored are block construction, multiple-protagonist plots, subjective viewpoint, non-chronological story sequence, voice-over narration, and others. Some had come to be associated with certain genres (thanks again to prototypes), but I found that they were quite pervasive. Several of these I’ve tried out on the blog.

Once I was peering through the lenses of these categories, my prototypes changed too. Now little-discussed films like Our Town (1940) and Tales of Manhattan (1942) and The Human Comedy (1943) and The Chase (1946) became surprisingly central. I couldn’t ignore the classics, but they were now lit by a crosslight that brought out fresh aspects. And with these categories of narrative technique in mind, we can discover some new sides of well-known auteurs, like Welles, Hitchcock, Sturges, and Mankiewicz.

One broader category I tried out was that of “murder culture.” Mystery and suspense are perennial narrative appeals, but they took on new power in in fiction, film, and theatre of the Forties. (An early version of the chapter’s case is made here.) Part of murder culture was the rise of the serial-killer tale—not new in the 1940s, of course, but more common than in earlier Hollywood eras. Films like Shadow of a Doubt (1943), The Lodger (1944), Bluebeard (1944), Hangover Square (1945), Lured (1947), Follow Me Quietly (1949), and others became prototypes for my purposes.

Then Monsieur Verdoux appeared in a new light. What better evidence of the pervasiveness of murder culture than the effort by the most-loved film star in history to play a serial killer?

Landru in LA

Orson Welles and Charles Chaplin, Brown Derby restaurant, March 1947.

It was Orson Welles who prompted Chaplin to make Monsieur Verdoux. Welles was a thriller fan. He carried a trunkload of crime novels around on his travels. One of his early RKO projects was an adaptation of Nicholas Blake’s Smiler with a Knife, and after the debacle of It’s All True, his work as a freelance director consisted of thrillers (The Stranger, The Lady from Shanghai, Mr. Arkadin) and Shakespeare adaptations (Macbeth, Othello). Indeed, he treated Shakespeare’s plots as thrillers, in accord with his belief that the Bard wrote not classical tragedies but blood-and-thunder melodramas.

According to biographers, Welles wrote a screenplay based on the wife-murderer Landru and offered the role to Chaplin. Chaplin at first accepted, then decided to direct the film himself and bought the idea from Welles. There was apparently some dispute about giving Welles credit; early prints are said to have lacked acknowledgment of Welles’ idea as the source.

By late 1941, the trade press reported that Chaplin was preparing the film, then called “Lady Killer.” A year later, it was still discussed as a “plan.” Chaplin didn’t finish the screenplay until 1946, and the film was shot between May and September. By then it was entitled “A Comedy of Murders,” although Chaplin toyed with “Bluebeard” and “Bluebeard Rhapsody.” It wasn’t released until spring of 1947.

This long gestation period is significant because when Chaplin started, the idea of a comedy about killing would have been fairly fresh. By the time Verdoux was released, however, Arsenic and Old Lace (1944) and Murder, He Says (1945) had already shown that audiences would accept humor mixed with homicide. The original stage production of Arsenic and Old Lace had opened to great success in January of 1941, and it’s interesting to speculate that it might have encouraged Chaplin to buy Welles’ Landru idea.

Both Arsenic and Murder, He Says treat murder with a consistently farcical tone. I suggest in my FilmStruck Observations episode that Chaplin risks something more complex. For one thing, he takes the conventions of the serial-killer film more seriously than the other films do. He goes on to amplify and exaggerate those conventions in fascinating ways. For instance, he makes the policemen more or less stick figures, so we don’t care if they’re in jeopardy. In turn, Verdoux tries to win our allegiance through clumsy efforts to be debonair. (Uncle Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt is far more poised.) Chaplin’s use of the cycle’s conventions gets pretty specific. There were dead narrators in 40s films before Sunset Blvd. (1950), but we tend to forget that Chaplin uses the same device in Verdoux.

Going further, I discuss how Chaplin’s treatment of serial killing mixes different sorts of comedy—social satire and slapstick, the traditional comedy of manners and the comedy of ideas associated with George Bernard Shaw. This mix is rather discordant, and it’s responsible, I think, for much of the criticism the film attracted, then and now.

The Tramp as provocateur

Verdoux failed in the US for several reasons. Reviews were mostly unsympathetic, even harsh. Chaplin had been back in the headlines thanks to a messy paternity suit filed by Joan Barry. His reputation as a seducer of young women had unpleasant associations with Verdoux’s conquests. He was also known for his support for liberal causes and his strong stance against fascism. After the war, he was more and more reviled by right-wing politicians and activists. Chaplin’s defense of civil liberties made him seem too much a Communist dupe, or an active sympathizer. Charles Maland has suggested that the film’s promotion completely mishandled Chaplin’s star image.

The disgraceful New York press conference on the film was chronicled in the New Republic:

The disgraceful New York press conference on the film was chronicled in the New Republic:

He couldn’t have expected the shockingly rude, sustained impertinence of the attack that followed. Reporters were there, not to discuss his work with him, but to discredit and vilify and ridicule him personally—to hound him on his own opinions and habits. Was it true that one of his good friends (I am omitting names), a great musician, was a radical? Did this mean that he, Chaplin, condoned treason to this country, since his friend’s brother was accused of being a spy? Was Chaplin a Communist? Why, then, had he shown so little regard for the United States that, although he had paid taxes here for years, he was still a British subject? Even though two of his sons fought for this country in the war, and he did war work himself, why didn’t he do more? Exactly what percentage of his vast income made in the US had gone to alleviate the suffering of humanity?

While two perambulating mikes broadcast these questions and others, a swarm of cameramen set off lights in Chaplin’s face, so that in an hour he was not only knee-deep in spent flash bulbs, but practically blinded. His patience and courtesy were astounding, since his disgust must have at least compared to that of the few of us who could only be ashamed of what ugly, hostile liberties can be taken in the name of the freedom of the press.

The final scenes of Verdoux only heightened the suspicion that Chaplin was a danger to patriotic values. Soon he was subpoenaed by the House Unamerican Activities Committee, though he never testified. In 1952, after he and his new wife Oona left for Europe, his re-entry permit was rescinded. He went into exile in Switzerland.

The reviewers’ most common complaint was that the film refused to jell, but the film had eloquent defenders and brought forth some of the subtlest critical commentary of the period. James Agee, the only person to defend Chaplin during the press conference, wrote a famous three-part appeciation of the film that, I think, represents an early instance of in-depth film interpretation. Theatre historian Eric Bentley argued against those who found the movie a jumble of sentiment and slapstick. It was, he claimed, in the vein of Pirandello, where comedy gives way to the more philosophical mode, that of humor.

Reflection turns the merely funny into humor. . . . Thus, Pirandello argues, humor breaks up the normal form by interruption, interpolation, digression, and decomposition; and the critics complain of lack of unity in all humorous works from Don Quixote to Tristram Shandy—and we might add from Little Dorrit to Monsieur Verdoux.

Going still wilder, Parker Tyler speculated that in a parallel universe, Verdoux wasn’t executed. He abandoned his wife and son and took off on the road. Charlie the Tramp “had a past like anyone else. . . . Verdoux is . . . how Charlie came to be.”

Tyler’s flight of fancy isn’t surprising. This film can drive you a little nuts. It’s not ingratiating. It’s less perfect than provocative. It’s like the name itself, ver-doux, which translates as “sweet worm” or “gentle worm”—a little pleasant and a little creepy. The film is an obstinate thing that insists on being its contradictory self, not what you want it to be. For me, it’s perversely unlovable, and that unlovability is part of the Chaplin myth too. We should remember that the earliest Chaplin films show the Tramp as fairly nasty.

I suspect that Monsieur Verdoux can’t become a prototype; it flouts too many cherished categories. Or maybe the best category for it is that of experimental Hollywood movie. After all, the 1940s furnished more than its share of them.

Thanks as usual to Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and Peter Becker of Criterion. Our complete Observations on Film Art Criterion series is here. (I think you need to be logged in to see it.)

Welles discusses Shakespeare as blood-and-thunder melodramatist in This Is Orson Welles (HarperCollins, 1992), 217, and in a little more detail, in audiocassette number 4 accompanying the book, side A, 18:37. I draw my information about the preparation of Verdoux from Frank Brady, Citizen Welles (Scribners, 1989), 416-417; “Chaplin Announces Bluebeard Film,” Motion Picture Herald (29 November 1941); and Glenn Mitchell, The Chaplin Encyclopedia (Batsford, 1997), 191-198. Charles Maland’s reflections on Verdoux‘s promotional problems are in Chaplin and American Culture: The Evolution of a Star Image (Princeton, 1989), 250-251. The coverage of the Monsieur Verdoux press conference is by Shirley O’Hara in “Chaplin and Hemingway,” New Republic (15 May 1947), 39. Bentley’s 1948 essay is “Monsieur Verdoux and Theater,” In Search of Theater (Vintage, 1953), 154.

I’ve argued in The Rhapsodes that Agee’s critique displays the interpretive techniques borrowed from literary New Criticism. In the same book I discuss Tyler’s Chaplin book as an ultimate flight of performative criticism. One consequence of 1940s murder culture was the crystallization of the suspense thriller, a genre that has flourished ever since, for several reasons.

There’s more on my forthcoming book on the 1940s here.

Monsieur Verdoux.

Going inside by staying outside: L’AVVENTURA on the Criterion Channel

DB here:

This month, our entry on FilmStruck’s Criterion Channel is a discussion of L’Avventura. This isn’t my favorite Antonioni movie, but it’s one I enjoy and admire—not least because of its striking originality of mise-en-scene. So that’s what I tackle in the Criterion entry.

The installment is here, and if you’re a subscriber you can watch it immediately. Otherwise, there’s a chance to sign up. If you’re not aware of FilmStruck, one of the great adventures in modern film culture, you can check on it here. (The Twitter feed is enjoyable even to non-tweeters like me.) Today, I want to flesh out my entry with some other comments. I hope they’ll be of interest even to those who aren’t signed on to the FilmStruck enterprise.

Two ways of doing deep

Le Amiche (1955).

During the 1950s, Antonioni displayed vigorous experimentation in visual style. Like many directors, he embraced the long take, usually in conjunction with camera movement. Within those parameters, he staged his action both laterally and in depth. But depth staging comes in many flavors.

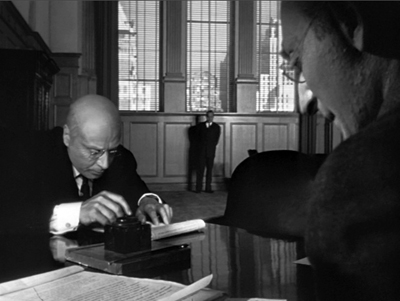

One is the aggressive deep-focus technique of Welles, with large heads or objects very close to the camera in the foreground. Here are two famous instances from Citizen Kane (1941).

This fairly extreme approach was picked up by some 40s and 50s directors, especially those interested in what came to be called film noir.

You can find somewhat mild versions of these compositions in early Antonioni, especially in cramped surroundings. A bus ride and a necking party in I Vinti (1953) bring forth some big foregrounds.

Despite occasional shots like these, Antonioni’s early work favors an alternative approach to depth, the one cultivated by Jean Renoir, Mizoguchi Kenji, William Wyler, and others. That approach doesn’t go for Citizen Kane baroque. It keeps the foreground plane fairly distant–say a medium-shot or further–and uses both lateral and fairly deep staging to multiply key points of interest in the shot. Less fancy than the Welles tradition, it allows more naturalistic blocking because it yields more playing space.

Go back to I Vinti, and we’ll find that most shots aren’t as thrusting as Welles’ images, largely because of their reliance on real locations and naturalistic lighting. The film tends to stages its long takes in mid-range, porous compositions. A two-minute shot of teenagers lounging at a cafe and plotting a murder is rendered in a gentle diagonal that spreads out multiple points of interest.

By the way: Why doesn’t anybody make shots like this any more?

One advantage is that while the packed Wellesian frame tends to make its actors assume fixed poses, the more open frames of the alternative can show more of actors’ bodies and develop gestures and other actorly bits. This happens in the I Vinti café scene, which depends on characters’ changing postures, along with the distraction of the annoying little girl blowing on drink straws.

Similarly, Antonioni’s first feature, the noirish romance Story of a Love Affair (1950) makes adroit use of the mid-range foreground. The famous single-shot, 360-rdegree scene between lovers quarreling on a bridge is a paradigm case of how location filming can be made rigorous and purposeful. A complex camera camera movement is coordinated with figures resolutely evading each other in constantly varied medium-shots.

Le Amiche (1955) continues down the same path, with characters alotted distinct pockets of the frame to expose their fleeting reactions.

But there’s now a more intricate choreography, as befits a plot with several story lines. A scene gathering the major characters at a cafe is a magnificent exercise in the Wyler manner, with heads meticulously spotted across the frame.

For years I was surprised that L’Avventura (1960) and its successors La Notte (1961) and L’Eclisse (1962) make less use of this sort of precise staging in depth. While the director’s style remains fluid and rigorously patterned, and powerfully exploits urban vistas, it relies more on editing. But looking again at L’Avventura for the Criterion Channel installment, I became convinced that he was exploring a new way to handle staging—one that built upon his mastery of Renoir-Wyler choreography.

From the back or from the front

When a film’s narrative harbors mysteries, they’re often a matter of plot. Something has happened that we don’t fully know about, and the business of the plot is to bring that to light, either in the short term or across the whole movie. In the detective film, there’s a mysterious crime that needs solving, and the clarification will typically come at the climax, when the malefactor (and the motive, and the means) will get revealed. Plot-centered mysteries are easily dismissed as superficial, but the great tradition of literary detection shows that they can be imaginative and gripping, while also exploring literary techniques in sophisticated ways.

There are also mysteries of character—not just whodunit, but something deeper. A narrative might induce us to ask what makes characters do what they do. This can result in fairly superficial probing, as in many psychoanalytic films of the 1940s, but it can, again, prod the storyteller to exploit some aspects of the medium that engage us. At the limit, mysteries of character can lead the narrative to explore the moods and motives of its people, bringing out contradictions of mind and action. Even a potboiler like Gone Girl not only reveals the rage bubbling beneath Amy’s perfect porcelain surface but explains that anger as a response to the Cool Girl role dictated by yuppie culture.

I usually don’t employ the distinction plot vs. character when I’m thinking about film narratives, but as a first approximation it points up the nuances of L’Avventura’s visual strategies. The film has, initially, a clear-cut plot-based mystery: What has led Anna to disappear? Is she dead, or lost, or simply escaping from the situation? This is, in a way, the bait luring us to pursue mysteries of character.

What, to start, does Anna want from her affair with Sandro? She seems alternately flirtatious, cynical, angry, and passionate. And assuming her disappearance wasn’t accidental, what impelled her to leave the party? As for Sandro, what sort of man is he? And why does he, with unseemly haste after Anna’s vanishing, seize Claudia and kiss her violently?

Claudia, for her part, seems to gradually accept her role as the Anna substitute. We’d expect her to be torn by her betrayal of her friend, and maybe she is, but we can’t be sure. With almost no backstory supplied for these people and no plunge into their inner lives through dreams, voice-over, subjective visions, and the like, we’re forced to read their minds and hearts on the basis of what they say and do. This is relentlessly behaviorist cinema.

Here’s where visual style kicks in, I think. Antonioni declared his interest in moving the Neorealist impulse from social observation to psychological revelation.

The neorealism of the postwar period, when reality was what it was, so intensely present, focused on the relationship between characters and reality. What was important was that very relationship, which created a cinema based on “situations.” . . . That’s why, nowadays it’s no longer important to make a film about a man whose bicycle has been stolen. . . . It is important to see what is inside this man whose bicycle was stolen, what are his thoughts, what are his feelings.

How to achieve this psychological penetration? Not through the sort of definite scene structure of a Hollywood film, a crisp slice of action that can be summed up in a story beat.

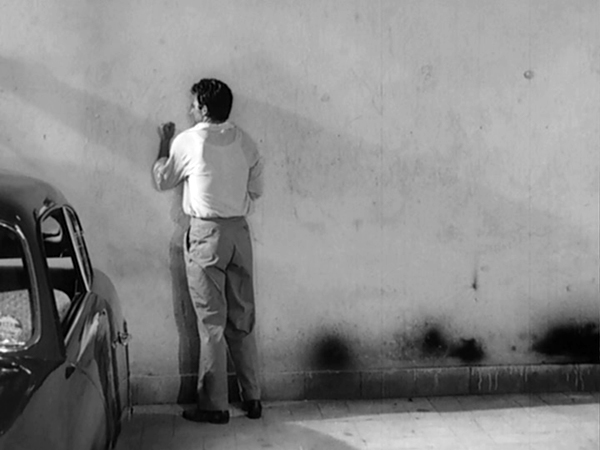

I believe it is much more cinematic to try and capture the thoughts of a person through an ordinary visual reaction, rather than enclose them in a sentence. . . . One of my concerns in filming is to follow the characters until I feel it is time to stop. . . When all has been said, when the main scene is over, there are less important moments; and to me, it seems worthwhile to show the character right in these moments, from the back or the front, focusing on a gesture, on an attitude.

Antonioni scenes, critics sometimes say, begin a bit before they start and end a bit after they stop.

You might expect from this emphasis on character psychology and the habit of lingering on a scene’s resonance would yield few mysteries. Yet what interests me in L’Avventura is the way in which it doesn’t allow us to “see what is inside” its characters. Perversely, having braked the dramatic momentum in order to probe character, Antonioni goes on to block our access to his people’s minds.

His visual strategies for doing this are many, and they’re flaunted in the film made just before L’Avventura. The witholding of character reaction is flamboyant in Il Grido (1957), maybe over the top.

L’Avventura‘s reticent pictorial strategies are more nuanced and naturalistic, and my FilmStruck contribution tries to chart them. For about the first hour of the film, Antonioni lets landscape overwhelms his characters, gives them equivocal facial expressions, refuses the full information of shot/reverse shot cutting, and at crucial moments simply makes his actors turn from the camera, denying us access to their emotional reactions.

What’s just as interesting, the second half of the film selectively returns to the techniques that were initially banned. It’s as if these more familiar image schemas–reverse shots, frontal close-ups, more marked facial reactions–have become suitable to the growing romance between Claudia and Sandro. Now the first hour’s stingy attitude toward psychological information is balanced by a greater degree of emotional exposure, especially on Claudia’s part. By the very end, the two broad strategies coexist uneasily, and some enigmas remain.

During the late 1960s Antonioni changed his style. He turned from deep-focus, wide-angle images to flat telephoto ones, and he began relying on a pan-and-zoom technique. These were partly responses to shooting in color and wider formats, I think, but they also offered the opportunity for a painterly look that he exploited in the films from Red Desert (1964) on. Fellini, Bergman, Visconti, and others took a similar path, as I tried to show in this early blog post.

In 1960 those developments were yet to come. It seems to me that the style of L’Avventura enhances the mysteries of plot and character in a unique and unsettling way. We get a visual surface that entrances us with its measured beauty and teases us with its calm opacity.

Thanks as usual to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and the Criterion team for including us in their FilmStruck enterprise.

My quotation from Antonioni comes from his essay “My Experience [1958],” in his book The Architecture of Vision: Writings and Interviews on Cinema (Marsilio, 1996), 7-9.

The L’Avventura discussion on FilmStruck is the fourth in our Criterion Channel series, “Observations on Film Art.” The others are Jeff Smith on the music of Foreign Correspondent, me on Sanshiro Sugata, and Kristin on landscape in Kiarostami. Some clip extracts can be found here and here. Jeff has amplified his installment with further comments on this blog, and I’ve done the same with Sanshiro , as today with L’Avventura. We introduce our collaboration in this entry. The Criterion introduction to us is here.

For more on Mizoguchi’s approach to depth staging, see this summary entry. There’s more on Wyler’s style here. I compare the two directors in this entry on sleeves. I discuss the broader shift from deep-focus techniques to pan-and-zoom ones in On the History of Film Style, Chapter 6.

I Vinti.

Action and essence: Kurosawa’s SANSHIRO SUGATA on the Criterion Channel

DB here:

Our contributions to FilmStruck’s Criterion Channel continue. Last month brought Jeff Smith’s analysis of musical motifs in Foreign Correspondent and his celebration of the skill of Alfred Newman, supplemented by a blog entry here. This month it’s my turn, taking on Kurosawa’s Sanshiro Sugata (1943; all Japanese names hereafter in Western order, family name last). My presentation is here, if you are a FilmStruck subscriber. A bit of it is available to all at the Criterion site. Today’s entry fleshes that out with some contextual background.

If the streaming version of Observations on Film Art is a bit like a bonus material on a DVD, think of these blog entries as liner notes with clips. This format allows us to tackle the films from an angle not covered in our videos. We’re sorry that not all of our readers can access the Criterion Channel. But if these entries inspire you to go back to the films in whatever form you can find them, that would be all to the good.

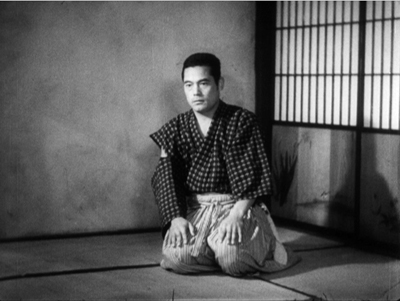

Conquering the self

Sanshiro is a film à clef, using martial arts to promote a nationalistic cultural pride. The character of Sanshiro was based on Shiro Saigo (above), who was one of the first pupils of the founder of judo, Jigoro Kano. (In the film, Kano is called Yano, below.) Kano learned the traditional fighting technique called jujutsu (aka jujitsu). Like jujutsu, judo involves grappling, locking, and throwing, and it deploys the opponent’s force against him (or her). But Kano tried to refine the art, eliminating some of the harsher techniques, like biting and kicking, and aiming for maximum efficiency of energy.

By treating judo as a sport and encouraging sparring and public matches, Kano led judo to prominence. His pupils defeated jujutsu challengers. In 1885-1886 matches against Tokyo police champions, Kato’s star pupil Saigo proved judo’s prowess.

In the hands of Kano and Saigo, unarmed fighting techniques were turned to spiritual ends. Ju-jutsu, “flexible technique” was replaced by ju-do, “the path of flexibility”—a devotion to a way of life rather than mere mastery of grips and throws. This distinction is enacted in the film, when Sanshiro, having learned enough technique to bully people with abandon, must learn to master himself.

Judo’s emphasis on spiritual seeking fitted an ideology that emerged in the Meiji period (1868—1912). Japan’s elite was bent on incorporating Western technology and social institutions while maintaining, or rather constructing, a distinct national identity. Accordingly, jujutsu, whose origin lay in Chinese boxing, came into disfavor as part of “feudal” traditions. With young people becoming entranced by Western sports like boxing and wrestling, the government encouraged the development of judo as both modern and uniquely Japanese. As often happened, these “inherently Japanese” cultural forms were of recent invention.

Kano became a public figure and oversaw the introduction of judo into the public school system in 1908. At the same time his pupil Saigo featured in popular culture as a hero of novels, often as the quasi-mythical Sanshiro Sugata. By then, judo was well established as recreation. And by 1943, when Kurosawa made his film, he was at pains to show judo as the progressive force replacing old-fashioned jujutsu.

Kano became a public figure and oversaw the introduction of judo into the public school system in 1908. At the same time his pupil Saigo featured in popular culture as a hero of novels, often as the quasi-mythical Sanshiro Sugata. By then, judo was well established as recreation. And by 1943, when Kurosawa made his film, he was at pains to show judo as the progressive force replacing old-fashioned jujutsu.

There’s another dimension to the story. John Dower has pointed out that imperial wartime propaganda tended to emphasize not triumph over the enemy but the need to purify the self. Accordingly, judo’s victory in the social sphere parallels Sanshiro’s conquest of his anger and egotism.

In the film, Sanshiro comes to Tokyo in 1882, the year Kano actually founded his school. After training, both physical and spiritual, the young man proceeds to defeat the surly jujutsu master Monma. Bristling with youth and vigor, Sanshiro then comes to represent a rising generation capable of surpassing its elders. The next fight references Saigo’s most famous combat during the 1886 police tournament. He must defeat the kindly jujitsu master Murai. But he is attracted to Murai’s daughter Sayo, and so it pains him to trounce her father. But Murai acknowledges judo’s superiority and easily forgives Sanshiro. Judo, he says, awakens his senses.

Most intently, Sanshiro’s purity of spirit clashes with the foppish, Europeanized Higaki, who exploits judo for aggression and self-aggrandizement. Their big fight comes on a wind-swept hillside, perhaps a reference to Saigo’s signature technique yama-arashi (“mountain storm”). The polarity Japanese/ Western would become even stronger in the film’s sequel, Sanshiro Sugata II (1945), in which Sanshiro must fight an American boxer. But from fight to fight, Sanshiro gains greater and greater self-possession, so that in the climactic combat, he can spare time to stare at clouds and envision lotus blossoms.

The film’s plot reverses Saigo’s actual life course: He became a street brawler after he won his tournament victories. More basically, Sanshiro Sugata goes beyond its historical sources and political program, as ambitious films tend to do. Nationalistic messages appropriate to wartime are transformed, reworked—”cinematized”—through Kurosawa’s remarkably dynamic approach to film style.

A resumé film?

Sanshiro is a young man’s first film. Kurosawa started on it when he was thirty-two (within my magic-number deadline). In the Criterion Channel video, I treat the movie as an occasion for an ambitious director to display his versatility—a sort of resumé film, as we’d say nowadays, and maybe a little showoffish.

He was ready for the project. He had a busy several years as an assistant director and screenwriter at the fast-moving Toho studios. He worked on twenty-eight dramas and comedies between 1936 and 1942. When he read Sanshiro’s source novel upon publication, he urged Toho to buy it, and he plunged into his project with fervor.

Like other young directors in Japan, he was well aware of developments abroad. His autobiography records seeing many imported films, from Broken Blossoms (1919) and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) to Metropolis (1927) and The Blue Angel (1930). Interestingly, he claims to have seen Storm over Asia (1928), Epstein’s Fall of the House of Usher (1928), Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928), and even films by Buñuel and Man Ray. His viewing included Hollywood fare by Ford, Lubitsch, Borzage, Wellman, Sternberg, and others. Indeed, he could have kept up with American cinema right up to Pearl Harbor; prints of Edison the Man (1940), Morocco (1930), and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) seem to have been playing in Tokyo in late 1941. Then all American films were banned.

So he was a cinephile director, perhaps not quite as passionate as Ozu, but a young man who looked and learned. Like most Japanese directors, he had mastered Hollywood continuity staging and cutting. I’ve argued elsewhere that many of his contemporaries were bolder stylists than the Americans. Whether it’s a matter of long takes, camera movements, rapid cutting, or subtle transitions—the Japanese found their own striking innovations.

Ozu’s distinctive 360-degree staging space, low camera height, and play with graphic editing constitute an extreme example of Japanese pictorial invention, but he wasn’t alone. Take this passage from Naruse’s Street without End (1934). The heroine has left her husband’s hospital bed after denouncing him, his mother, and his sister for selfishness. Servants and family rush past her; he may be dying. She hesitates in the corridor. Should she return?

The pattern of cuts and frame entrances accentuates her uncertainty—taking a step, and halting—while the clashing directions in which she moves (right, left, right) have a Soviet-montage flavor. So do the blank frames at the start of every shot, since we have no idea of where we are in the corridor, or where she is, until she thrusts into the frame. And we don’t know whether she chooses to return or not; the geometrical cutting expresses her hesitation.

This geometrical approach to editing is one of the characteristics of Sanshiro I discuss in the video entry. You see it near the start, when alternating single shots of Yano, back to the river, are intercut with slow tracking shots across Monma and his truculent students. To push the pattern further, the tracking shots alternate—first in one direction, then another. Like two rhyming lines in poetry, each of these cinematic couplets brackets one futile attack on Yano after another. Later fight scenes will get more complicated, but display no less rigorous a patterning. And the purpose is always to add to the tension and excitement of the combat.

Another sort of pattern we find in Sanshiro is simpler, but Kurosawa works some nifty variations on it. It’s also somewhat geometrical, but it serves mostly to accentuate a moment of stillness. This is the axial cut, the shot change that moves in or back along the axis of the camera lens. The effect is of sudden enlargement or de-enlargement, a popping out toward the viewer or a sudden withdrawal. Like most directors, Kurosawa uses the axial cut to enlarge something–here, Sayo’s act of praying for her father at a temple.

When the axial cut is justified as a character’s viewpoint, it has the effect of signaling a sharp narrowing of attention. This happens here, when we realize in the voice-off remark (“How beautiful”) and a fourth shot that Yano and Sanshiro have come upon her. That exemplifies an axial cut that moves backward rather than inward.

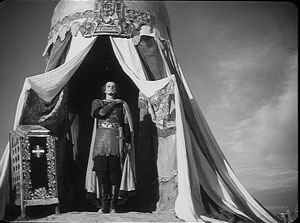

I discussed Kurosawa’s fondness for axial cuts years ago, but it’s interesting to see their origins here. They’re present from the earliest years of cinema, but Kurosawa, again like the Russians, used them expressively. Most uses in Hollywood consist of just two shots, a long shot and then a closer one on the camera axis. But the Soviets, perhaps starting with Eisenstein, multiplied the number of shots and made them fairly brief, so the effect is of a person or object punching out at the viewer. Eisenstein uses the device throughout his silent films, but in both Alexander Nevsky and the two parts of Ivan the Terrible, he develops the device in a very virtuoso manner. Here’s Ivan, standing above the battlefield.

Eisenstein adds to the popout effect by cheating Ivan’s position between shots, so he jumps forward out of his tent.

I’ve found some axial cuts in Japanese films before Kurosawa started directing. One of the most “Kurosawa-ish” comes in a minor 1939 Nikkatsu swordplay film called Faithful Servant Naosuke (Chuboku Naosuke). Again, the cut-ins emphasize a poised moment.

Even if Kurosawa didn’t invent the technique, he made it more prominent and percussive in Sanshiro. It makes the pauses within combat as staccato as the action of fighting. I spend some time in the video talking about how this all works in particular scenes.

Kurosawa’s next film, The Most Beautiful (1944), itself a real beaut, uses the technique quite differently, mainly for tension. His later films continue to explore its possibilities. Sanshiro Sugata Part 2 (1945) resorts to the device to express our hero’s lingering departure for the big duel. He trots toward us, and each time he pauses to look back, Sayo bows.

Today’s filmmaker would probably pull us back with a tracking or crane shot, but by relying on editing Kurosawa gives us his typical crisp geometrical patterning. The abrupt cuts underscore Sanjuro’s realization that he may not return from this life-or-death confrontation. Sanshiro Sugata Part 2, along with the first film and The Most Beautiful, is available from Criterion, as a disc and on FilmStruck streaming.

My streaming presentation discusses other cinematic strategies Kurosawa employs, but these remarks should give you a sense of just how energetically creative he’s being in his first film. It’s a very flashy item, and it looks far into the future. Decades of kung-fu films have been based on dueling dojos, rival fighting methods, and escalating challenges. In addition, Kurosawa’s technique, moving lightly under the weight of an official message, seems very modern.

Youthful, too. As he told Donald Richie, “I really make my films for people in their twenties.”

The information about the history of judo comes from Gabrielle and Roland Habersetzer, Encyclopédie des arts martiaux d’extrême orient (Amphora, 2000), 265-268, 300-301, 549, and 765. Kurosawa lists films he saw in his youth in Something Like an Autobiography, trans. Audie Bock (Knopf, 1982), 73-74. John Dower’s discussion of Japanese propaganda is in War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (Pantheon, 1987). The closing quotation comes from a 1962 conversation reprinted in Akira Kurosawa Interviews, ed. Bert Cardullo (University of Mississippi Press, 2008), 8. Thanks to Hiroshi Komatsu for information about Faithful Servant Naosuke.

Street without End is available in the Criterion Eclipse collection Silent Naruse. If you don’t have this set, get it pronto.

Informative books about Kurosawa and Sanshiro include Donald Richie, The Films of Akira Kurosawa third ed. (University of California Press, 1999); Stephen Prince, The Warrior’s Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa, rev. and exp. ed (Princeton University Press, 1991); and Stuart Galbraith IV, The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune (Faber, 2001). Especially revealing about Kurosawa’s production methods in his later films is Teruyo Nogami, Waiting on the Weather: Making Movies with Akira Kurosawa, trans. Juliet Winters Carpenter (Stone Bridge Press, 2006). On the “spiritist” trend in government policy in the media of the period, see Peter B. High’s magisterial The Imperial Screen: Japanese Film Culture in the Fifteen Years’ War, 1931-1945 (University of Wisconsin Press, 2003), Chapter 6.

For more on axial cutting in Soviet and modern films, and The Simpsons, go here. I discuss Eisenstein’s axial cutting in The Cinema of Eisenstein, Chapters 2, 4, and 6. On Ozu’s characteristic staging, shooting, and editing system, see my Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, available for download from the University of Michigan Library site. The full PDF takes a while to download, but you can get access quickly by clicking on “List of all pages.” I discuss other aspects of the tradition from which Kurosawa comes in Poetics of Cinema, Chapters 12 and 13. See also the Kurosawa, Ozu, Mizoguchi, and Shimizu entries on this site.

Kim Hendrickson, Criterion producer, and Grant Delin, DP, filming DB from a closet.

Spies face the music: Jeff Smith on FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT

DB here: Here’s another guest contribution from colleague, Film Art collaborator, and pal Jeff Smith. He inaugurates a series of entries tied to our monthly Observations on Film Art videos on FilmStruck.

About a month ago, a new streaming service for film lovers debuted. Its name is FilmStruck and it’s a joint venture of Turner Classic Movies and the Criterion Collection.

As regular readers of the blog already know, David, Kristin, and I have launched a series for FilmStruck. Every month, we’ll be featured in short videos that offer appreciations of particular films and filmmakers. In baseball lingo, I got the leadoff spot. As the first up, I offered an overview of the principal musical motifs in Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent. Below is a supplement to the video that goes into a little more depth regarding the way Alfred Newman’s score for Foreign Correspondent fits into the film’s larger narrative strategies.

Fair warning: there are some spoilers in what follows. Some of you who are FilmStruck subscribers or owners of the Criterion disc may want to watch this Hitchcock classic before proceeding.

Founding a Hollywood dynasty

Alfred Newman.

If you were looking for someone whose work epitomized the qualities of the classical Hollywood score, Alfred Newman would be a pretty good candidate for the job.

Newman’s career in Hollywood began when Tin Pan Alley stalwart, Irving Berlin, recommended him for the 1930 musical, Reaching for the Moon. Having worked for years as a music director on Broadway, Newman planned to stay for only three months. But the lure of the Silver Screen was too strong. Newman spent the next forty years working in Hollywood.

In 1931, Newman became the musical director at United Artists, working mostly for producer Samuel Goldwyn. He also established himself as one of the industry’s leading composers, contributing to nearly ninety films over the course of the 1930s and earning nine Oscar nominations in the process. Newman’s most memorable early scores included such titles as The Prisoner of Zenda, The Hurricane, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and Wuthering Heights. Eventually, he would leave Goldwyn to take over the music department at 20th Century-Fox, a position he held for more than twenty years.

Alfred, however, would be just one of several Newmans who would make the name synonymous with the Hollywood sound. Alfred would establish a film composing dynasty that would come to include his brothers Lionel and Emil; his sons, Thomas and David; and his nephew, Randy.

Overture, hit the lights….

If you asked most film music aficionados for their favorite Alfred Newman scores, I suspect Foreign Correspondent would be pretty low on the list. Most fans of the composer’s work would likely opt for one of the later Fox classics he scored, such as How Green Was My Valley (1941), A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1945), The Captain from Castile (1947), or The Robe (1953). Yet, if you want to get a handle on the basic features of the classical paradigm, Foreign Correspondent’s typicality makes it more useful as an exemplar. Newman’s music neatly illustrates several of the traits commonly associated with the classical Hollywood score’s dramatic functions.

One of these characteristic traits is Newman’s use of leitmotif as an organizational principle. Foreign Correspondent’s score is organized around five in all. The first is a theme for the film’s protagonist, Johnny Jones. The second is a theme for Carol, Johnny’s love interest in the film. As is typical of studio-era scores, both themes are introduced in the film’s Main Title.

Like an overture, the Main Title previews the two most important musical themes in the film. The A theme is upbeat, sprightly, and lightly comic. It captures some of Johnny’s ebullience and masculine charm, and it helps establish the tone of the early scenes, which draw upon the conventions of the newspaper film. The B theme is slower and more lyrical. It features the kind of lush orchestrations for strings that became a hallmark of Newman’s style.

Each theme roughly correlates with the dual plot structure common to classical Hollywood narratives. The A theme previews the main plotline focused on Johnny’s efforts as an investigative reporter. The B theme previews the story’s secondary plotline: the budding romance between Johnny and Carol.

Both themes recur throughout the remainder of the movie. In fact, Johnny’s theme returns even before the opening credits have ended, appearing underneath a title card valorizing the power of the press. In contrast to the lively, spunky version heard earlier, Newman gives it a maestoso treatment, slowing the tempo and orchestrating it for brass. In this instance, Newman’s arrangement of Johnny’s theme is attuned less to the brashness of his character and more to the social role that newspaper reporters play as a source of information to the world.

Up until this point, the music simply primes us for what is to come. Johnny’s theme returns about two minutes later when he is first introduced.

The reprise of his theme makes explicit the Main Title’s tacit association between music and character. Here, though, it plays in a jazz arrangement as a slow foxtrot. Newman’s arrangement nicely captures the tone of these early scenes, which display the lightness and pacing of other newspaper comedies.

It returns 22 more times in the film. In all, Johnny’s theme accounts for more than a quarter of the film’s 94 music cues. Usually, the theme functions to underline Johnny’s heroism and resourcefulness as in the scene where he gives chase to Van Meer’s assassin. At one point, Johnny even whistles his theme. This occurs in the scene where he eludes a pair of suspicious men posing as police by pretending to draw a bath and crawling out the window.

In contrast, Carol’s theme is used less frequently, appearing in about thirteen cues in all. After its introduction in the main title, it returns when Johnny and Carol first meet at the luncheon sponsored by the Universal Peace Party. Johnny unknowingly insults Carol, first by mistaking her for a publicist, and then by expressing skepticism about the organization’s mission, griping about well-meaning amateurs interfering in international affairs. Newman’s theme hints at Carol’s attraction to Johnny despite his obvious boorishness. The music says what the characters can’t or won’t say. As Johnny and Carol trade insults, Carol’s theme captures the romantic spark that lurks beneath their badinage.

The theme’s other uses often work along similar lines, providing an emotional resonance to the couple’s expression of feelings for one another. A good example is found in the scene where Carol and Johnny huddle together on the deck of a steamship. Here, as a pair of refugees, each member of the couple declare their love for one another and their desire to marry.

Music for the hope of the world

In addition to these two principal themes, the score also utilizes three other themes and motifs to represent important secondary characters. A theme for Professor Van Meer is introduced when Johnny spots him getting into a taxicab.

It returns nine more times in the film in scenes that feature the character or make reference to him.

The theme itself is simple, slow, stately, and quite frankly, a little bit boring. Indeed, if it wasn’t for the multiple references to a “Van Meer Theme” on the cue sheet for Foreign Correspondent, the music would simply blend into the other material that surrounds it.

The orchestration of the theme for solo wind instruments, usually an oboe, gives it a kind of pastoral feeling. The image of peaceful shepherds is likely an appropriate one for Van Meer, who functions as a stand-in for a global desire to avoid armed conflict. Yet, both the character and Newman’s musical theme for him seem nondescript, making Van Meer seem like little more than the walking embodiment of an abstract ideal of world harmony.

Truth be told, Van Meer mostly operates in Foreign Correspondent as the classic Hitchcock MacGuffin–that is, the thing the characters all want, but with which the audience need not concern itself. When Van Meer appears to be assassinated, it sets in motion a chain of events that uncovers a conspiracy organized through Steven Fisher’s World Peace Party. Van Meer is the object that all the characters want to find, and the search for him drives the narrative forward. Yet the character himself has about as much personality as the microfilm in North by Northwest. Newman’s nondescript melody seems to fit the “blank slate” quality of Van Meer himself.

Like the classic MacGuffin, Van Meer’s function as something of an empty vessel allows his theme to be used several times late in the film in scenes where the character isn’t physically present. Although the norm is to use characters’ themes or leitmotifs when they are onscreen, Newman’s treatment of Van Meer shows they can evoke absent characters. This occurs, for example, in a scene where Scott ffolliot explains to Stephen Fisher that he’s arranged for the kidnapping of Carol. Fisher asks ffolliot why he would do such a thing, and ffolliot replies that he wants to know where Stephen has stashed Van Meer.

As we’ll see, Fisher has a theme of his own that itself appears several times in this same scene. But the use of Van Meer’s theme in this context becomes a way of signifying both the character and the peaceful values that he represents – that is, values that Fisher seeks to destroy.

And though Van Meer’s music is a bit dull, the theme proves a bit more interesting when one considers the way it works within Hitchcock’s larger strategies of narration. At a key point, Hitchcock and Newman use the Van Meer theme to mislead the audience about what has just transpired onscreen. I’m referring here to the moment when Van Meer appears on the steps just as the Peace conference in Amsterdam is about to commence.

The theme is cued by Johnny’s glance offscreen after briefly chatting with Fisher, his publicist, and a diplomat. Hitchcock cuts to a shot from Johnny’s optical POV that shows Van Meer climbing up the staircase. We return to Johnny, who smiles and walks out of the frame. Johnny and Van Meer meet in a two-shot where the former offers a warm greeting. A cut to Van Meer’s reaction, though, reveals a blank stare, even as Johnny tries to remind the elderly professor of their previous encounter in the taxi.

The moment is an important one, but before the viewer can even grasp its significance, the two men are interrupted by a request for a photograph. Hitchcock then tracks in on the newsman, who surreptitiously sneaks a gun next to the camera he is holding. He pulls the trigger, and Hitchcock cuts to a brief insert of Van Meer, who has been shot in the face.

As I noted earlier, the assassination we witness is a key turning point in the story, and Hitchcock handles the scene with considerable finesse. Almost unnoticed, though, is the fact that Hitchcock and Newman cleverly use Van Meer’s musical theme as a form of narrative deceit. At first blush, the musical theme helps to reinforce Van Meer’s identity, serving the kind of signposting function that some film music critics believed was a hackneyed device. As we later learn, though, the murder victim is not Van Meer, but rather a double killed in his place to foment international tensions. This information ultimately recasts the old man’s seeming failure to recognize Johnny. As Van Meer’s double, these two men have never actually met.

Has Hitchcock played fair in using Van Meer’s theme for a character that is not Van Meer but only looks like him? Perhaps, but the creation of this red herring is justified if one considers the fact that composers frequently write cues meant to reflect or convey a character’s point of view. Every composer must make a choice about whether to write a cue from the particular perspective of the character or the more global perspective of the film’s narration. Newman might have opted for conventional musical devices that connote suspense (ostinato figures, string tremolos, low sustained minor chords), and these would have signaled to the viewer that Van Meer is in peril, thereby creating a heightened anticipation of the violence that erupts in the scene. Instead, though, following the visual cues provided by Hitchcock’s cinematography and editing of the scene, Newman plays Johnny’s perspective and his recognition of Van Meer as he approaches the building’s entrance. By combining two common tactics–leitmotif and character perspective – Newman and Hitchcock briefly mislead the audience in order to create two surprises: the first when it appears that Van Meer is killed and the second when Van Meer is discovered inside the windmill and proves to be very much alive.

Menace (without the Dennis)

There is also a brief six-note motif used to signify the conspirators as a group. Labeled the “menace” motif, it is introduced just after Van Meer’s apparent assassination. In the chase that follows, Newman alternates between the “menace” motif and Johnny’s theme in order to sharpen the conflict and to capture the ebbs and flows of our hero’s dogged pursuit of the bad guys.

The motif returns, though, at just about any point where one of the group’s henchmen gets up to no good. In the scene inside the windmill, the menace motif appears several times to underscore the kidnappers’ nefarious scheme. Johnny sneaks inside the windmill, and after locating Van Meer, he tries to rescue him only to find out that the elderly professor has been drugged. As Johnny tries to figure out his next move, muted trumpets play the “menace” motif, signaling the kidnappers’ approach and thereby heightening the scene’s suspenseful tone.

Here again, Newman’s thematic organization reinforces a larger narrative tactic in Hitchcock’s film. Herbert Marshall serves as the typical suave villain commonly found in the Master’s oeuvre and Edmund Gwenn steals the show as Johnny’s would-be assassin, Rowley. But the rest of the conspirators are a largely undistinguished lot, and the use of a single motif for the group in toto reflects their relative impersonality. Unlike North by Northwest, where Martin Landau makes a vivid impression as Van Damm’s reptilian assistant Leonard, this spy ring seems to be filled out by thugs from Central Casting.

Father, leader, traitor, spy

Besides motifs for Johnny, Carol, Van Meer and the conspirators, there is also a short motif for Carol’s father, Stephen Fisher. It is harmonically and melodically ambiguous, structured around the rapid, downward movement of a chromatic figure.

In classical Hollywood practice, a leitmotif is usually introduced when the character first appears onscreen. But in an unusual gesture, Newman and Hitchcock resist this convention. The motif does not appear until more than eighty minutes into the film in the aforementioned scene just before ffolliot tries to blackmail Fisher into divulging Van Meer’s location.

By withholding Fisher’s motif, Hitchcock and Newman avoid tipping their hand too early. Since Fisher is later revealed to be the leader of the spy ring, the score circumspectly avoids comment on him in order to preserve the plot twist.

Several cues featuring Fisher’s motif return in the scene where Johnny, Carol, ffolliot, and the other survivors of the plane crash cling to wreckage waiting to be rescued. Carol spots the plane’s pilot stranded on its tail.

He swims over to the group and clambers about the wing. The pilot’s added weight threatens to upend the wing, thereby endangering everyone sitting atop it.

Recognizing this, the pilot asks the others to let him go so that he can simply “slip away.” Fisher overhears this exchange and decides to remove his life jacket and dive into the waters himself, leaving room on the plane’s wing for the rest of crash’s survivors.

The harmonic and melodic ambiguity of Fisher’s motif is most pronounced here, a moment where the character’s duality is also most clearly revealed. Is this a heroic act of self-sacrifice, an act of atonement for the damage Fisher has done to both his daughter’s reputation and his organization’s peaceful cause? Or has Fisher taken the coward’s way out, committing suicide in order to avoid facing the consequences of his actions?

Newman’s rather opaque musical motif doesn’t seem to take sides on this question, leaving Fisher’s motivation more or less uncertain. But this, too, is in keeping with the basic split between the character’s public and private personae. Introduced earlier as Carol’s father, Fisher appears to be cultured and debonair. Yet, when he seeks to extract information from a reluctant captive, Stephen resorts to the physical torments used by two-bit gangsters to make mugs talk. Like those gangsters in the 1930s, Fisher refuses to be taken alive and is swallowed up in briny sea. Still, his action does help to save other lives, and in this way, Fisher enables Carol to find a small measure of grace in the final memory she will have of him.

Putting earworms inside actual ears

As the principal composer of music for Foreign Correspondent, Newman had a major impact on the film’s ultimate success. Yet Newman was not responsible for the music that has engendered the most attention in critical work on the film. I’m referring here to two source cues written by Fox staff arranger, Gene Rose, that are featured in the scene where Van Meer is psychologically tortured. His captors use sleep deprivation techniques to elicit van Meer’s cooperation, including bright lights and the repeated playing of a jazz record. The two cues received rather cheeky descriptions on the cue sheet for Foreign Correspondent: “More Torture in C” and “Torture in A Flat.”

The use of jazz for these cues is likely a little bit of wicked humor on Hitchcock’s part. Despite its popularity as dance music in the 1930s, some listeners undoubtedly believed that jazz was little more than noise with a swinging rhythm. From a modern perspective, though, the scene eerily anticipates the “enhanced interrogation” techniques that would become notorious at Guantánamo and Abu Ghraib. As The Guardian reported in 2008, US military played Metallica’s “Enter Sandman” at ear-splitting volume for hours on end, both at Guantanamo and at a detention center located on the Iraqi-Syrian border. At the other end of the musical spectrum, one of the other pieces played repeatedly was “I Love You” sung by Barney the purple dinosaur. Presumably the first was selected because of its aggressiveness, the latter because of its insipidness. But the Barney song has the distinction of being characterized by military officials as “futility” music – that is, its use is designed to convince the prisoner of the futility of their resistance.

Although, in 1940, Hitchcock could not have envisioned the use of heavy metal and kidvid music as elements of enhanced interrogation, the scene from Foreign Correspondent is eerily prescient. Viewed today, the scene also carries with it a strong element of political critique insofar as it associates such psychological torture techniques with a bunch of “fifth columnists” who are willing to commit murder and even engineer a plane crash in order to achieve their political ends. Touches like these make Foreign Correspondent seem timely today, more than seventy-five years after its initial release.

Alfred Newman the Elder

After Foreign Correspondent, Alfred Newman would go on to score more than a hundred and thirty feature films, and earn several dozen more Academy Award nominations. His nine Oscar wins remain an achievement unmatched by any other film composer. Newman died in Hollywood in 1970 at the age of 69, just before the release of his last picture, the seminal disaster movie, Airport. His work on Airport received an Oscar nomination for Best Original Score, the 43rd such nomination of his long and distinguished career.

For some film music scholars, Newman’s death marked the end of an era, as his career was more or less contemporaneous with the history of recorded synchronized sound cinema in Hollywood. As fellow composer Fred Steiner wrote in his pioneering dissertation on the development of Newman’s style:

As things are, we can be grateful for the dozen or so acknowledged monuments of this twentieth-century form of musical art— absolute models of their kind— that Newman did bestow on the world of cinema. Fashions in movies and in movie music may come and go, but scores such as The Prisoner of Zenda, Wuthering Heights, The Song of Bernadette, Captain From Castile, and The Robe are musical treasures for all time, and as long as people continue to be drawn to the magic of the silver screen, Alfred Newman*s music will continue to move their emotions, just as he always wished.

Because of its typicality, Foreign Correspondent may well seem like a speed bump on Newman’s road to Hollywood immortality. Yet it remains a useful introduction to the composer himself, who along with Max Steiner and Erich Wolfgang Korngold, is part of a triumvirate that would come to define the sound of American film music.

For more on music in Alfred Hitchcock’s films, see Jack Sullivan’s encyclopedic Hitchcock’s Music. For more on the production of Foreign Correspondent, see Matthew Bernstein’s Walter Wanger: Hollywood Independent. Readers interested in learning about Alfred Newman’s career should consult Fred Steiner’s 1981 doctoral dissertation, “The Making of an American Film Composer: A Study of Alfred Newman’s Music in the First Decade of the Sound Era,” and Christopher Palmer’s The Composer in Hollywood.

Tony Thomas’s Film Score: The Art & Craft of Movie Music includes Newman’s own account of his work for the Broadway stage before coming to Hollywood. Readers interested in an overview of the classical Hollywood score’s development should consult James Wierzbicki’s excellent Film Music: A History.

Alfred Newman conducts his most famous film theme, Street Scene, in the prologue to How to Marry a Millionaire (1953).