Archive for the 'Critics: Agee' Category

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD: Out of the past

Cover Girl (1944).

DB here:

I just got my first copy of Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. I’m always scared to look at a published piece because I expect my eye to light on (a) a misprint; or (b) a sentence of unusual clumsiness or simplemindedness. Other writers have told me they have similar qualms. But I did look, and on this fat volume: so far, so good. It even has black, slightly corrugated endpapers, like the paper inside a box of chocolates.

This was a personal project for me, for reasons I’ve sketched elsewhere on this site. I grew up watching 1940s films on TV and have always had a fondness for what James Naremore has called “the beating heart of Hollywood.” In my teen years, watching Welles and Hitchcock movies along with B films and minor musicals fed my interest in studio cinema.

When I started teaching in the 1970s, I was keen to catch up with all those nifty movies sitting comfortably in our Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. My classes screened His Girl Friday (in a pirate copy) and Meet Me in St. Louis and Possessed and The Locket and White Heat and The Ministry of Fear and many more. Students working with me studied Gothics, war films, and I Remember Mama. It was then I started to realize just how creative this period was.

One piece of boilerplate for the book puts it more melodramatically.

In the 1940s American movies changed. Flashbacks began to be used in outrageous, unpredictable ways. Viewers were plunged into characters’ memories, dreams, and hallucinations. Some films didn’t have protagonists. Others centered on anti-heroes or psychopaths. Women might be on the verge of madness, and neurotic heroes were lurching into violent confrontations.

Films were exploring parallel universes and supernatural dimensions. Characters switched bodies or intuited the future. Combining many of these ingredients, there emerged a new genre—the psychological thriller, populated by murderous spouses and witnesses who became targets of violence.

If this sounds like our cinema of today, that’s because it is. In Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, David Bordwell examines for the first time the range and depth of the 1940s trends. Those trends crystallized into traditions. The Christopher Nolans and Quentin Tarantinos of today owe an immense debt to the dynamic, occasionally delirious narrative experiments of the 1940s.

Bordwell shows that the booming movie market at the start of the Forties allowed ambitious writers and directors to push narrative boundaries. He traces how Orson Welles, Preston Sturges, Alfred Hitchcock, Otto Preminger, and dozens of lesser-known creators built models of intricate plotting and psychological complexity.

Those experiments are usually credited to the influence of Citizen Kane, but Bordwell shows that the experimental impulse had begun in the late 1930s, in radio, fiction, and theatre before migrating to cinema. And even with the late 1940s recession in the industry, the momentum for innovation could not be stopped. Some of the boldest films of the era came in the late forties and early fifties, when filmmakers sought to outdo their peers.

Through in-depth analysis of films both famous and virtually unknown, from Our Town and All About Eve to Swell Guy and The Guilt of Janet Ames, Bordwell analyzes the era’s unique ambitious and its legacy for future filmmakers.

Today I’d like to give you some background on the book and flag a new page on this site you might find of interest. (If you can’t wait, you have permission to go there now.)

Questions, questions

Kitty Foyle (1940).

Reinventing Hollywood turned my enthusiasm for the 1940s into a set of questions.

The enthusiasm was based on a hunch that Hollywood cinema between 1939 and 1952 saw a burst of innovative storytelling. The innovations weren’t utterly new, but they differed from what was seen in the 1930s by virtue of their range, number, and complexity. The more I looked, the more I realized that the Forties recaptured the narrative range and fluidity of silent cinema, extending and nuancing it with sound. In essence, a new set of norms emerged, forged by many filmmakers.

Several questions followed. How to describe those innovations? How to chart their range and variations? How to analyze their effects—on the sort of stories told, on how viewers understood them? How did the innovations alter genres, or create new ones? How might we explain the rise and expansion of these new norms? And finally, what sort of legacy did this process of changing conventions leave to the filmmakers that followed? In all, how did various trends coalesce into a tradition?

This plan, ridiculously ambitious, at least has the virtue of originality. Most books about the 1940s concentrate on major figures—stars, producers, directors, the Hollywood Ten. Other books explain how studios or censorship or labor disputes worked. Others focus on genres such as the musical or the melodrama or the combat film. A popular option is devoted to that not-quite-a-genre film noir. These are all worthy subjects. And there’s no shortage of books seeing 40s film as a reflection of wartime or postwar America, or the geopolitics of the Cold War.

Studying narrative norms cuts across many of these common perspectives. Individuals matter, particularly ambitious screenwriters, producers, and directors striving to tell stories in unusual ways. But institutions matter too, as studio culture and writers’ associations prized a degree of originality in plotting or point of view. And narrative devices cut across genres to a considerable degree. Although flashbacks have come to be associated with film noir, they actually appear in all genres, and take on different roles accordingly.

So, 621 films later, my project has become an effort to contribute to a history of film form—the various storytelling methods that filmmakers have developed in different times and places. (In other words, a poetics of cinema.) In effect, I’m asking that the kind of appreciation people show for genres, actors, and auteurs be stretched to narrative strategies as well.

Darryl F. Zanuck, with his shrewd narrative instinct, gave me my epigraph.

It is not enough just to tell an interesting story. Half the battle depends on how you tell the story. As a matter of fact, the most important half depends on how you tell the story.

The book in between

Daisy Kenyon (1947).

The project blended in with earlier work I’d done, particularly in The Classical Hollywood Cinema and The Way Hollywood Tells It. In a sense, Reinventing Hollywood is a bridge between those two books.

CHC, written with Kristin and Janet Staiger, traced continuity and change in the studio storytelling tradition from its inception to 1960. It analyzed how conventions of story, style, and work practices were established and maintained over the decades. The Way Hollywood Tells It suggested that after 1960, the broad conventions remained in place but were modified in particular ways.

In passing, I suggested that innovations of “contemporary Hollywood” owed a lot to experiments launched in the 1940s. The new book tries to pay off that IOU. Reinventing Hollywood asks how, within the broad conventions of classical Hollywood, particular innovations could emerge in the boom-and-bust 1940s. Many standard devices of our films today, from voice-over and fragmentary flashbacks to block construction and tricks with point of view, can be traced back to the Forties, when they were consolidated and refined.

The two earlier books also considered film technique—staging, shooting, editing, and the like. Reinventing Hollywood doesn’t tackle visual style, for two reasons. It would have doubled the book’s length, and I’ve said my say on 40s style in other work. Style shapes story, of course, and I’ve tried to take this factor into account. But I concentrate on the principles of story world, plot construction, and narration—the three dimensions of narrative I’ve outlined elsewhere.

None of these books is auteurist in basic orientation, but they aren’t anti-auteurist either. Surveying techniques in a systematic way helps call attention to adepts, middling talents, and innovators. In Reinventing, I think the interludes on Mankiewicz, Sturges, Welles, and Hitchcock show how skillful filmmakers mobilized emerging conventions in powerful ways. In effect, we reconstruct a menu of options to sense the values in picking and mixing them. For example, Citizen Kane‘s investigation plot, adorned with a dying message and a bevy of flashbacks, was a vigorous synthesis of devices that were circulating through film and other media in the late 1930s. The boldness of the effort made it influential on what followed. We get a better sense of directors’ (and writers’ and producers’) idiosyncratic strengths when we know the norms they’re working with, and sometimes against.

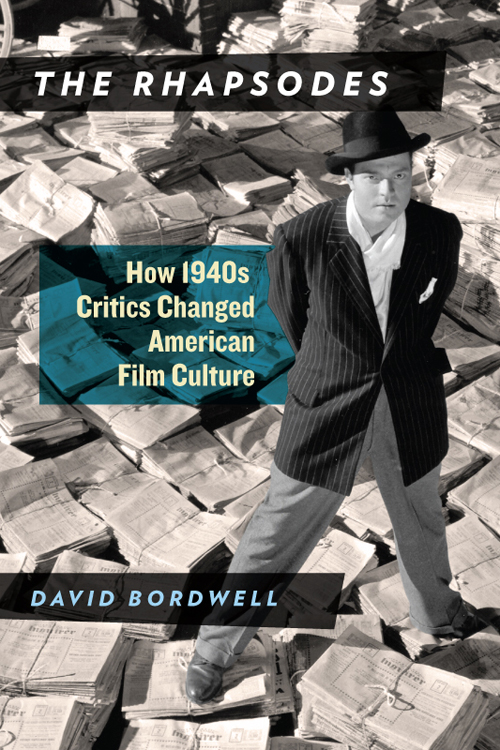

Reinventing Hollywood, running nearly 600 pages, makes The Rhapsodes look scrawny. But it isn’t the behemoth that CHC is. CHC could give this book noogies.

The big and the small

The Bishop’s Wife (1947).

It was hard to discuss broad trends and still probe particular cases in detail. So the chapters move from generalities to specifics in steps. Some films are merely mentioned, others described briefly, others considered at greater length, and some analyzed in depth. After a conceptual introduction and a historical panorama of Hollywood as a creative community (Chapter 1), there are chapters on flashbacks, plot construction, woven versus chaptered plots, manipulation of viewpoint, voice-over, character subjectivity, psychoanalytic plots, realism and fantasy, mystery plots, and self-conscious artifice. The conclusion looks at the impact of the period on later filmmakers.

I try to go beyond obvious observations to study the mechanics of familiar devices. So I come up with terms and concepts to pick out finer-grained tactics: the breadcrumb trail that sets up many flashbacks, block construction, hooks, switcheroos, and the like.

The chapters on particular techniques are broken by “interludes” devoted to particular movies or moviemakers. Some of these interludes involve well-known films and figures, but others look at obscure items. (Yes, The Chase is involved.) Even the treatment of Big Names tries to offer something original, as when I argue that Hitchcock and Welles pushed 40s innovations very far and sustained them throughout their later careers.

Here’s the table of contents, with small annotations

Introduction: The Way Hollywood Told It

Chapter 1: The Frenzy of Five Fat Years (Hollywood as an ecosystem)

Interlude: Spring 1940: Lessons from Our Town

Chapter 2: Time and Time Again (flashbacks)

Interlude: Kitty and Lydia, Julia and Nancy

Chapter 3: Plots: The Menu (conventions of plot structure)

Interlude: Schema and Revision, between Rounds

Chapter 4: Slices, Strands, and Chunks (alternative structural options)

Interlude: Mankiewicz: Modularity and Polyphony

Chapter 5: What They Didn’t Know Was (managing narrative information)

Interlude: Identity Thieves and Tangled Networks

Chapter 6: Voices out of the Dark (voice-over)

Interlude: Remaking Middlebrow Modernism

Chapter 7: Into the Depths (subjectivity)

Chapter 8: Call It Psychology (psychoanalytic films)

Interlude: Innovation by Misadventure

Chapter 9: From the Naked City to Bedford Falls (realism, fantasy, and in-between)

Chapter 10: I Love a Mystery (thrillers and mystery-based plotting)

Interlude: Sturges, or Showing the Puppet Strings

Chapter 11: Artifice in Excelsis (self-conscious display of conventions)

Interlude: Hitchcock and Welles: The Lessons of the Masters

Conclusion: The Way Hollywood Keeps Telling It (legacy of the 1940s)

To keep things specific, I’ve prepared eleven film clips keyed to particular analyses. Just playing the clips might give you a sense of the book’s range. They’re also fun in their own right.

No zeitgeists, please

Blues in the Night (1941).

Two last points. One bears on preferred explanations. How do we explain why cinematic innovation burst out at this particular time? Again, the book tries to pursue an uncommon path.

Many writers look to a zeitgeist—the anxieties of war, the anxieties of postwar adjustment, the anxieties of the anti-Communist crusade, any anxiety you can imagine. Instead I try to look for institutional factors shaping the films’ norms. Centrally, there are the conditions of the film industry, with its rich interplay of personnel and story materials shuttling all over the place. There are also the cinematic traditions themselves, such as plots depending on amnesia. Particularly important are the adjacent arts, including theatre, radio, and popular fiction. All these sources get modified by a process of schema and revision—borrowing something already out there but warping it to new ends. In short, instead of looking for remote causes in the broader society, I try to locate more proximate ones within the filmmaking community and the turmoil of popular culture.

Someone might argue that this just pushes the problem back a step. Don’t social anxieties surface in all these media? To this I’d argue, as I did here and here, that those anxieties are very hard to identify. Not all anxieties or concerns will be shared by a populace (viz. our current political situation). And we can’t establish a strong causal connection between them and the products of popular media—especially since media are indeed mediated, by tastemakers, gatekeepers, and the institutions that produce popular culture.

For the period I’m concerned with, James Agee noted the role of mediators in his complaints aimed at the film-as-dream sociologists of the period:

It seems a grave mistake to take [movies] as evidence as definitive, as from-the-public, as if 40 million people had actually dreamed them. Take the far simpler case of advertising art. The American family, as shown therein, is not only not The Family; it isn’t even what the American people imagines as The family. It is A’s guess at that, subject to the guesswork of his boss, which is subject in turn to the guesswork of the client. At best, a queer, interesting, possible approximation, but certainly never definitive. In movies many more people take part in the guesswork, but not enough to represent a population: and many more accidents and irrelevant rules and laws deflect and distort the image.

A movie does not grow out of The People; it is imposed on the people— as careful as possible a guess as to what they want. Moreover, the relative popularity or failure of a picture, though it means something, does not at all necessarily mean it has made a dream come true. It means, usually, just that something has been successfully imposed.

Instead of social reflection, we should expect refraction. Decision-makers opportunistically grab memes and commonplaces (the unhappy housewife, the juvenile delinquent, the returning vet) in hopes they can make something appealing out of them. They absorb those into familiar (narrative) forms. We get, then, not a “vertical” or top-down flow of social anxieties into artworks, but a “horizontal” ecosystem, a dynamic of exchange and transformation. The creators copy one another, obeying local norms while also resetting boundaries. This process includes selective assimilation of ideas thrown up by the culture, and it gets amplified by network effects, as sticky ideas themselves get copied. In other words, ideology doesn’t turn on the camera. The final film is always mediated by humans working in institutions, and both the people and the institution have many agendas.

A second point follows. Working on this book brought home to me how much film owes to other media. In a way, Forties cinema became more “novelistic” because it sought to assimilate techniques of split viewpoints, replays, inner monologue, and subjective response characteristic not so much of modernism (those were old hat by the 1940s) but of popular fiction and what we might call “middlebrow modernism.” A Letter to Three Wives (1948) attaches itself in turn to three women, each with memories of the past, with that trio interrupted by a never-seen fourth woman mockingly narrating the tale. It’s a cinematic treatment of the shifting viewpoints and personified narrative voices to be found in the nineteenth-century novel (Dickens, Collins, James) and later in genre fiction, not least in mystery tales. (It’s also a modification of the source novel.)

But you could also argue, as André Bazin did, that the 1940s saw a new “theatricalization” of cinema, with self-conscious adaptations that stressed stage conventions like the single-setting action. And of course radio supplied important prototypes for acoustic texture and first-person voice-over. Each of these devices wasn’t simply ported over to film; moving images and recorded sound gave literary, theatrical, and radio-based techniques new expressive possibilities. And all depended on the churn of people working side by side to innovate within familiar norms.

Every author discovers or remembers too late those things that should have been mentioned. Doug Holm reminded me of the dream narrative of Sh! The Octopus (1937). Jim Naremore pointed out that Rex Stout had already done my work for me in Too Many Women (1947, year of my birth), when Archie reports, “It was a wonderful movie . . . Only two people in it have amnesia.” On a different pathway, I’d love to do more research on moguls’ screening rooms as a condition of influence. (They could borrow films from rival studios without charge.) Julien Duvivier is a minor hero of my book, but only after the book was submitted did I see his L’Affaire Maurizius (1954), a perfect extension of 1940s storytelling to a French milieu.

And just recently I found a nice confirmation of the unexpected byways of the ecosystem. According to the author, the figure of the “psycho-neurotic” returning soldier was at first mandated by government policy but then twisted by ambitious screenwriters into tales of civilian madmen. The article has the enviable title: “That Psycho Story Swing Is No Cycle; It’s Now an Obsession.” If you buy the book, please write that into the endnotes.

And for the third time, feel free to visit the clips page!

I owe a lot to several people who saw this book through publication. Foremost are my editor at the University of Chicago Press, Rodney Powell, and his colleagues Melinda Kennedy and Kelly Finefrock-Creed. Then too there is Bob Davis, who supplied the book’s jacket photograph; Kait Fyfe, who prepared the clips for posting; and web tsarina Meg Hamel who set up the clips page. My other debts are recorded in the acknowledgments, but of course I must mention Kristin who had the hardest job of all. She had to put up with the author.

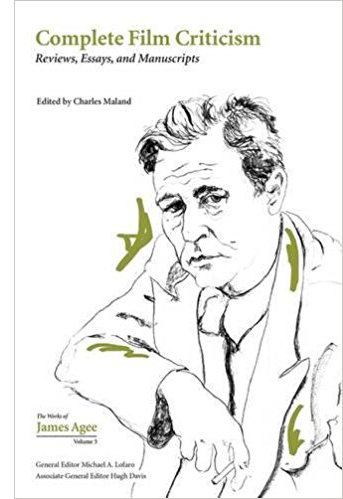

My Agee quotation comes from “Notes on Movies and Reviewing to Jean Kintner for Museum of Modern Art Round Table (1949),” in James Agee, Complete Film Criticism: Reviews, Essays, and Manuscripts, ed. Charles Maland (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2017), 975. I’m indebted to Chuck for sharing this with me. Chuck’s discussion of Agee on our site is well worth a read.

Many entries on this site are dedicated to 1940s Hollywood. See the relevant category. “Murder Culture” has been revised as a chapter in the book. On 1940s visual style, see Chapter 27 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema, Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style, and entries under 1940s Hollywood. There’s also the web essay on William Cameron Menzies. My most detailed arguments against social reflection and zeitgeists in historical explanations comes in the title essay in Poetics of Cinema, pp. 30-32.

Although the Amazon page offering Reinventing Hollywood says copies aren’t available until October, it seems that copies are shipping now from Chicago’s webpage. Amazon offers no discount on the title. (See P.S.) It’s currently available only in hardcover, with a paperback planned for the distant future.

P.S. 27 Sept 2017: Actually, Amazon is now discounting Reinventing Hollywood; it’s $30.77, as opposed to the $40 list price.

P.P.S. 13 October: Amazon’s prices on the thing have been fluctuating wildly. See this entry. Those wild and crazy algorithms!

Our Town (1940).

James Agee: Astonishing excellence: A guest post by Charles Maland

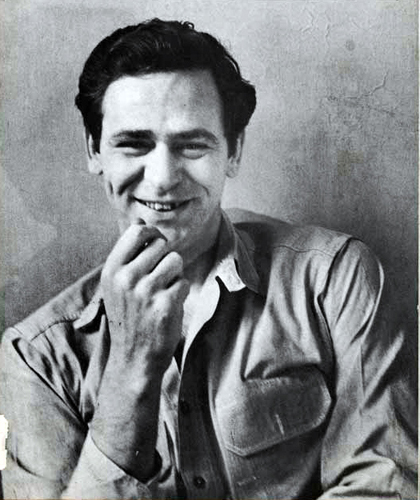

James Agee.

DB here: Charles Maland, a distinguished historian of American film, has just completed editing the definitive collection of James Agee’s film writings. It’s due to be published in July.

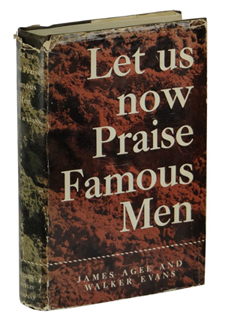

Agee changed American literature with Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, and he changed film criticism with his reviews for The Nation and Time. After I wrote a 2014 blog entry on his work, I learned of Chuck’s project. Later I decided to turn the entry into a chapter of The Rhapsodes, a study of 1940s American film criticism. Naturally, I turned to Chuck for help. He was magnificently generous, steering me to sources and sharing new material he discovered. In particular, Agee’s unpublished manuscripts contain some powerful arguments and insights. Chuck’s historical introduction to the collection fills in many details of Agee’s relation to popular journalism, to the political and intellectual currents of his time, and to the Hollywood industry.

This book will be one of the most important film publications of 2017. As a warmup, we invited Chuck to write a guest entry on Agee and the process of editing the volume. We’re glad he responded, and we think you will be too.

In the summer of 1927, a precocious seventeen-year-old high school student wrote this to an older friend:

To me, the great thing about the movies is that it’s a brand new field. I don’t see how much more can be done with writing or with the stage. In fact, every kind of recognized “art” has been worked pretty nearly to the limit. Of course great things will undoubtedly be done in all of them, but, possibly excepting music, I don’t see how they can avoid being at least in part imitations. As for the movies, however, their possibilities are infinite—is, insofar as the possibilities of any art CAN be so.

Sixteen years later, British poet W.H. Auden wrote of the “astonishing excellence” of a movie column in The Nation, written by the same person, calling it “the most remarkable regular event in American journalism today.”

Auden was commenting on none other than James Agee (pronounced AY’-jee), a writer that New York Times reviewer A.O. Scott later called “the first great American movie critic.” Acknowledging that Agee didn’t “invent” movie criticism, Scott contends that he did show “what it could be as a form of journalism and a way of talking about the world.”

I concur with Scott about the importance of James Agee’s movie criticism, and for the past several years I’ve been preparing a complete edition of Agee’s movie reviews and criticism. Complete Film Criticism: Reviews, Essays, Manuscripts will appear this July from the University of Tennessee Press as Volume Five of The Collected Works of James Agee. Here I’d like to tell you a little more about who James Agee was and how he became a movie reviewer, what problems I encountered and discoveries I made in compiling the volume, and why Agee’s movie writings still deserve our attention.

Who was James Agee, and how did he become a movie reviewer?

James Agee (1909-1955) was born in Knoxville, Tennessee. In his relatively short career he was a feature writer for Fortune magazine; a book reviewer and movie reviewer for Time magazine; a movie columnist for The Nation; a co-screenwriter of, among others, The African Queen and The Night of the Hunter; and author of a volume of poetry, Permit Me Voyage (1934), an expansive social documentary book called Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), and two novels, The Morning Watch (1951) and A Death in the Family (1957). The latter was published posthumously and won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1958.

The novel also draws on Agee’s autobiography. When Agee was six, his father was killed in a car accident, and the novel explores just such a situation of a young boy, growing up in the Fort Sanders neighborhood of Knoxville, and the way he and his family cope with the father’s death. In real life, following his father’s tragic death, Agee’s mother sent her son to the St. Andrew’s School, a boarding school in Sewanee, Tennessee. After a year at Knoxville High School, Agee transferred to Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire. There he finished high school and published his first movie review, on F.W. Murnau’s The Last Laugh, which is included in the volume. He then completed his education as an English major at Harvard.

Agee loved movies from childhood. A Death in the Family includes a scene in which father and son walk from their neighborhood to go to the movies in downtown Knoxville, where they see a Charlie Chaplin short and a William S. Hart western. But he didn’t get the opportunity to review movies professionally until the 1940s. His first job as a feature writer for Henry Luce’s Fortune magazine paid the bills.

His book on Alabama sharecropper farmers in the Depression, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, started as an assignment from Fortune, but when Agee discovered that the subject far exceeded the boundaries of a feature article, he took a leave from Fortune to write the book. When it appeared in 1941, Americans were thinking about World War II and it sold only 600 copies, despite some positive reviews. The book’s reputation began to grow during the social turbulence of the 1960s, when it was reprinted and spoke to readers during that era in powerful ways. .

Following that disappointing commercial response, Agee returned to work for Time, Inc., now as a book reviewer for Time. (Volume 3 of the Collected Works, edited by Paul Ashdown, includes all of Agee’s published book reviews and non-film journalism.) While reviewing books, Agee kept alert to openings in the movie section, and he finally got his chance by reviewing The Big Street, starring Lucille Ball and Henry Fonda; the piece appeared in the September 7, 1942, issue of Time.

From then on, he remained on staff at Time as a movie reviewer until November 1948. His reviewing stint was interrupted after he wrote a powerful cover story for Time about the detonation of atomic bombs in Japan. For a few months in late 1945 and early 1946, Henry Luce put him on special assignment to write on social and political topics.

In December 1942, Agee also received an invitation from Peggy Matthews, arts editor of The Nation¸ a left-leaning journal of politics and the arts, to do a regular movie column for that audience. Agee accepted and his first contribution appeared late that month. Agee was writing about movies in two different places until his last Nation column on July 31, 1948. In between, by my best count, he reviewed 561 films in Time and 460 films in The Nation. Of that number Agee discussed 320 titles in both venues.

Agee stopped reviewing because he got the itch to write screenplays. Between 1948 and his death, he sometimes supported himself and his family as a screenwriter. His two most famous credits are on John Huston’s The African Queen (1951) and Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter (1955). (Volume Four of the Collected Works, edited by Jeffrey Couchman, contains the script versions of these two films.) Partly to provide some income after he stopped reviewing but before his screenwriting career gained traction, Agee contracted with Life magazine (another Luce publication) to write extended essays on silent film comedy and John Huston. The resulting pieces, “Comedy’s Greatest Era” and “Undirectable Director,” are familiar to many readers. These pieces, along with some other individual Agee movie essays, like a review of Sunset Boulevard in Sight & Sound, also appear in the collection.

Problems and discoveries

The goal of this Agee collection is to provide access in one volume—for the first time—to all of Agee’s movie reviews, all of his other published articles and essays on movies, and a number of unpublished manuscripts I discovered in my research that cast light on Agee’s movie aesthetic and writing. Nearly all of Agee’s Nation reviews appeared in Agee on Film, Reviews and Essays (1958)—oddly, only his review of It’s a Wonderful Life was omitted—so compiling and editing those reviews was relatively uncomplicated.

The goal of this Agee collection is to provide access in one volume—for the first time—to all of Agee’s movie reviews, all of his other published articles and essays on movies, and a number of unpublished manuscripts I discovered in my research that cast light on Agee’s movie aesthetic and writing. Nearly all of Agee’s Nation reviews appeared in Agee on Film, Reviews and Essays (1958)—oddly, only his review of It’s a Wonderful Life was omitted—so compiling and editing those reviews was relatively uncomplicated.

Only a small selection of Agee’s Time reviews had appeared in Agee on Film. Because I began with what I thought was a full and accurate bibliography of all of Agee’s Time movie reviews, I thought that compiling them would be an uncomplicated task, too. I was wrong.

When he started reviewing for Time, and especially in his last months there, Agee was only one of several movie reviewers (although he was generally the primary reviewer). For the whole period he worked there, Time did not give bylines to writers. To verify what reviews Agee wrote, I enlisted the services of Bill Hooper, Time’s chief archivist. From him I learned that a copy-desk employee would handwrite in one master copy of each issue the name of the author of every article and review. These issues were then bound quarterly, and they eventually were deposited in the Time archives.

Mr. Hooper generously checked each volume against the bibliography I sent him and also responded to a number of questions that arose from the initial inquiry. The only period he was unable to verify was for the first three months of 1946: the bound volume from that period was missing. Fortunately, though, that was the time when Agee had taken an assignment as a special correspondent for social and political affairs.

As a result of these inquiries, I discovered that thirteen of the Time reviews and articles included in Agee on Film were in fact written by other journalists. It was even more suprising to discover that all thirteen of those pieces also appeared in the Library of America edition of Agee’s writings, Film Writing and Selected Journalism (2005). Thus, of the 39 film reviews, essays, and profiles included in that volume, Mr. Hooper and I discovered that Agee had written only 26 of them. So I’m deeply indebted to Mr. Hooper. He enabled me to compile all of Agee’s film writings at Time in one place for the first time, at least as close as it is humanly possible to do.

As a result of these inquiries, I discovered that thirteen of the Time reviews and articles included in Agee on Film were in fact written by other journalists. It was even more suprising to discover that all thirteen of those pieces also appeared in the Library of America edition of Agee’s writings, Film Writing and Selected Journalism (2005). Thus, of the 39 film reviews, essays, and profiles included in that volume, Mr. Hooper and I discovered that Agee had written only 26 of them. So I’m deeply indebted to Mr. Hooper. He enabled me to compile all of Agee’s film writings at Time in one place for the first time, at least as close as it is humanly possible to do.

The Agee papers, held principally in the special collections units at the University of Texas and the University of Tennessee, also contained a variety of fascinating information. I learned from financial records that Agee was well paid as a salaried employee of Time and that he was paid modestly at The Nation ($25 a column at first, later—it seems—by the word, which often amounted to less than $25). A few uncashed checks from The Nation in the archives suggest that Agee wasn’t much of a businessman. Other documents contained lists of film screenings that had been set up for Agee; they suggest that he saw a great many films, both in press screenings and regular theatre showings.

Perhaps most interesting for our purposes were a number of previously unpublished manuscripts. They included: 1) four-page typed “Movie Digest,” written in late 1935 or early 1936, containing thumbnail reviews (most with grades—A through F) of films, mostly from 1934 and 1935; 2) a scathing 1938 review of Bardèche and Brassilach’s The History of Motion Pictures that Partisan Review decided not to publish, probably because of how unrelentingly harsh it was; 3) a long letter that Agee wrote upon the request of Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish with suggestions about possible films to include in the Library of Congress film collection; and 4) some notes on movies and reviewing, probably from 1949, for a proposed Museum of Modern Art roundtable discussion of movies. All these manuscripts, including several essays or proposals for essays on René Clair and Sergei Eisenstein—both Agee favorites—are included in the collection.

Agee as movie critic

It’s hard in a short space to make generalizations about Agee’s aesthetic and why he should continue to interest us as a movie reviewer. Yet I would say he’s important for at least five reasons.

First, grounded in the history of film, he took films seriously and thought they were capable of being great, even though most movies failed to live up to his exacting standards. Beginning his childhood movie-going about the time that Chaplin was becoming an enormous star, Agee came to embrace a pantheon of filmmakers against which he measured other work. That pantheon included silent film comics like Chaplin and Keaton; filmmakers with great ambitions who had difficulty fitting into the system in which they worked, like D.W. Griffith, Erich von Stroheim, and Sergei Eisenstein; and European masters like Murnau, Pabst, Clair, Hitchcock, Dovzhenko, and Dreyer. He also praised a variety of contemporary American filmmakers, including those as diverse as William Wyler, Preston Sturges, Val Lewton, and John Huston.

First, grounded in the history of film, he took films seriously and thought they were capable of being great, even though most movies failed to live up to his exacting standards. Beginning his childhood movie-going about the time that Chaplin was becoming an enormous star, Agee came to embrace a pantheon of filmmakers against which he measured other work. That pantheon included silent film comics like Chaplin and Keaton; filmmakers with great ambitions who had difficulty fitting into the system in which they worked, like D.W. Griffith, Erich von Stroheim, and Sergei Eisenstein; and European masters like Murnau, Pabst, Clair, Hitchcock, Dovzhenko, and Dreyer. He also praised a variety of contemporary American filmmakers, including those as diverse as William Wyler, Preston Sturges, Val Lewton, and John Huston.

Second, his work is historically significant. He began writing just as the film industries of the United States and its Allies were trying to determine the role of movies during the world war that was raging. In his earliest reviews, Agee tended to celebrate the Allied documentaries (what he called “record” films) to the detriment of fiction movies. He was especially sensitive to a kind of poetic realism that he celebrated in Italian Neorealism (in his review of Shoeshine, for example) and in George Rouquier’s Farrebique.

Third, Agee was a magnificent and witty writer. He could write sustained, insightful essays, like his Time cover stories on Ingrid Bergman and on Laurence Olivier’s Henry V or his famous three-part defense of Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux. But he was also funny, especially when criticizing a film. Early in 1948 Agee got behind in his Nation reviews when he was hospitalized with appendicitis: to catch up he reviewed as many as 25 films in a single column, often in one sentence or two. Here are a few favorites:

On a mystery film starring Claude Rains, Agee wrote: “The Unsuspected is suspected too soon by the audience and too late by most of his fellow actors.” He disposed of an odd cinematic blend of whodunit and romance with this review: “Embraceable You is dispensable entertainment.” A John Wayne vehicle also took it on the chin: “Tycoon. Several tons of dynamite are set off in this movie; none of it under the right people.” He titled his February 14, 1948 column “Midwinter Clearance.” Perhaps my favorite was a Jeanne Crain-Dan Duryea vehicle: “You Were Meant for Me. That’s what you think.”

Fourth, Agee stands out because he had such catholic tastes. Although he was hard to please, he wrote enthusiastically and positively about a wide range of films. Agee praised European classics like Zero for Conduct, Ivan the Terrible (Part One), Day of Wrath, Children of Paradise, and Farrebique; British films like Henry V, Hamlet, Great Expectations, Odd Man Out, and Black Narcissus; a variety of American movies like The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, Meet Me in St. Louis, The Big Sleep, The Best Years of Our Lives, Notorious, Monsieur Verdoux, and The Treasure of Sierra Madre; documentary films like Desert Victory, San Pietro, and They Were Expendable; Hollywood B films like Val Lewton’s Curse of the Cat People; the emerging Neorealist films; and dark urban dramas like Double Indemnity that later became known as film noir. Any critic who could write informatively and with enthusiasm about such a broad range of films had to possess a wide-ranging sensibility that welcomed the breadth of artistic possibilities presented by the movies of his era.

I should acknowledge here that some commentators have argued that Agee was not critical enough about really bad films and that he was too equivocal, trying to find something good to say about most of the films he reviewed. I’d respond to these claims in a couple of ways. First, it’s true that Agee was often equivocal in his reviews, but that equivocation often took the form of saying a film could have been more successful if it had done something better, but it didn’t. Another form of Agee equivocation was to say that an otherwise failed film did have some redeeming element (a song, a performance, a stylistically effective moment).

I think the fact that he would sometimes give bad films some positive gesture was partly a function of his love of the movies as an art form. I have to say I’m sympathetic to Agee here. I usually find something redeeming in almost every movie I see, and my wife regularly tells our friends that she’s the true critic in the family—they should ask her, not me, if they should see a film!

Second, I think there’s some difference between Agee’s Nation and Time reviews. He was under tighter editorial oversight at Time, and I think he was under more pressure to avoid completely lambasting a film than he was in his Nation columns. Getting a chance to read all of Agee’s Time and Nation reviews will offer readers an opportunity to think about how he wrote differently about movies for different audiences. The fact remains, however, that of the films and filmmakers he really admired, Agee showered praise on an unusually wide range of different kind of films.

Finally, as David Bordwell has observed, the publication of Agee on Film: Reviews and Essays in 1958 had a strong influence on the growth of film culture in the United States during the 1960s and after. As Bordwell put it,

There’s no knowing how many teenagers and twentysomethings read and reread that fat paperback with its blaring red cover. We wolfed it down without knowing most of the movies Agee discussed. We were held, I think, by the rolling lyricism of the sentences, the pawky humor, and the stylistic finish of certain pieces—the three-part essay on Monsieur Verdoux, the Life piece “Comedy’s Greatest Era,” the John Huston profile “Undirectable Director.” The adolescent fretfulness that put some critics off didn’t give us qualms; after all, we were unashamedly reading Hart Crane, Thomas Wolfe, and Salinger too. Some of us probably wished that we could some day write this way, and this well.

Agee on Film came along at a propitious time: European art film was beginning to flourish and a new generation of critics and reviewers—Sarris, Kauffman, Kael, Schickel, Simon, and later Ebert—engaged with this exciting new film culture. All, at one time or another, acknowledged Agee’s contributions. All, like Agee, published their reviews in book form.

For all these reasons, James Agee’s writings on the movies deserve our continued attention. I hope that by preparing a volume which contains all of Agee’s movie reviews and essays in Time and The Nation, all his other published writings on movies, and a number relevant but previously unpublished essays, I will help enable interested readers to get an accurate and fuller appreciation of Agee’s contributions to our evolving film culture.

Charles Maland is the author of Chaplin and American Culture (Princeton University Press, 1991) and the BFI classics volume on City Lights (2008). We thank him for his willingness to serve as a guest blogger.

Agee’s youthful encomium to film comes from Dwight Macdonald, “Agee & the Movies,” in Dwight Macdonald on Movies (Prentice-Hall, 1969), 3. Auden’s praise of his criticism is in “Agee on Film (Letter to the Editor),” Nation 159, no. 21 (18 November 1943): 628. A. O. Scott’s remarks come from Gerald Peary’s For the Love of the Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism (Bullfrog Films, 2009). The Bordwell quotation is in The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture (University of Chicago Press, 2016), 2-3.

Agee’s name was frequently mispronounced. At the end of a 1948 Nation column, Agee apologized for mistakenly calling Amos Vogel “Alex” in a column, then went on to say, “I apologize to Mr. Vogel and to you; and sadly join company with an aunt of mine who used to refer to Sacco and Vanetsi, and with all those who call me Aggie, Ad’ji, Adjee’, Uhjee’, and Eigh’ ggeee’.”

Our next stop: Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato!

P.S. 1 May 2019: For more on Agee, observed from many perspectives, including Chuck Maland’s, see the commentaries at the Criterion Collection.

James Agee, portrait by Helen Levitt.

The Rhapsodes return

DB here:

In early 2014 I posted a blog series on three 1940s film critics. The entries were essays on James Agee, Manny Farber, and Parker Tyler. Under the title of “The Rhapsodes,” the entries discussed their backgrounds, their place in the history of American criticism, and each one’s perspective on the cinema of the 1940s. I called them Rhapsodes because I admired the daring, ecstatic, sometimes zany quality of their writing. Like the ancient singers of tales, these critics seemed in touch with the gods–in this case, the gods of cinema. They deployed their gifts shrewdly, in an effort to understand how Hollywood movies worked.

The series had actually begun a few months earlier with an essay on a fourth critic, Otis Ferguson, the big brother of my rhapsodic crew. I wound up with several essays that, I realized, could make a short book. I spent some months expanding, clarifying, and, I hope, deepening the ideas floated in the entries. The manuscript got sharp and supportive reading from Jim Naremore, who has written sensitively on Agee and Farber, and Chuck Maland, who is editing Agee’s film criticism for the University of Tennessee Press’s complete Agee collection. Sagacious editor Rodney Powell guided the book to and through the University of Chicago Press. Kristin and I are going over the page proofs now.

The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture is scheduled for April 2016 publication. You can learn more about it on the University of Chicago Press site. The Amazon page includes things said about it by David Koepp, Manohla Dargis, and Phillip Lopate. If you’re intrigued, you can preorder the book from either site.

I’ll be writing more about the book just before official publication in spring.

When publishing Minding Movies: Observations on the Art, Craft, and Business of Filmmaking and Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages, Kristin and I left the original posts online. But now that the Rhapsodes project has become more subtle and cohesive, I’d prefer that people read it in its new state. For this reason, in the near future I’ll be taking down the original posts.

Thanks to readers who have already expressed appreciation for the series and interest in the book!

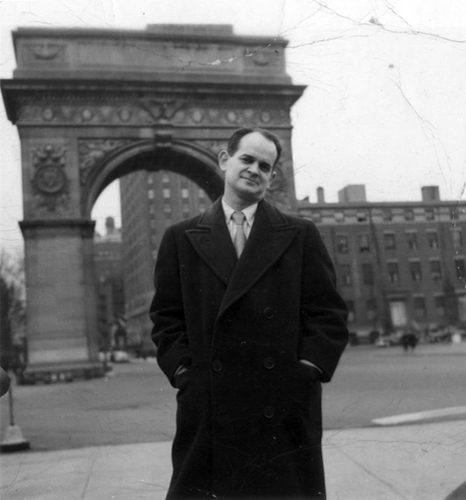

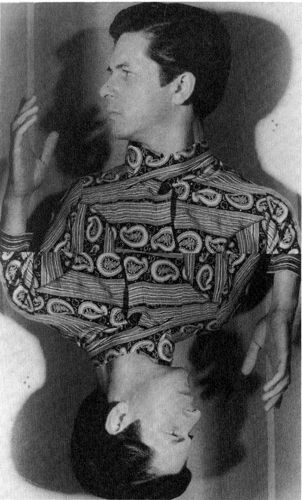

Since the book doesn’t include portraits of the writers and the original entries did, I’m offering some images below. From left to right: Otis Ferguson, James Agee, Manny Farber (courtesy Patricia Patterson), and Parker Tyler, photographed by Maya Deren.