Archive for the 'Critics: Shklovsky' Category

You say “formalism” like it’s a bad thing

The Godfather (1972).

DB here:

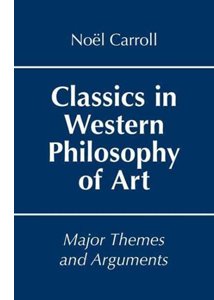

This year I caught up with three powerful books. The first was Noël Carroll’s Classics in Western Philosophy of Art: Themes and Arguments. I’ve praised Noël’s work previously on The Blog, and this volume didn’t disappoint.

It’s a survey of major philosophers’ efforts to define art and explain its appeal. Starting with Plato and ending with Clive Bell, it’s an entertaining, in-depth analysis of their theories and disputes. I learned a lot from every chapter, especially about figures I hadn’t known, like Francis Hutcheson. Of particular interest was Noël’s account of a major trend in modern thinking about art, which he calls Autonomism.

This view holds that an art work is defined by features that are unique to art, and that our “aesthetic experience” of an art work is radically unlike other experiences. The Autonomist view is often expressed as a version of “formalism,” the effort to anchor artistic purity and aesthetic experience in some conception of artistic form. As in his earlier Art in Three Dimensions (2012), Noël subjects this trend of thought to a devastating critique.

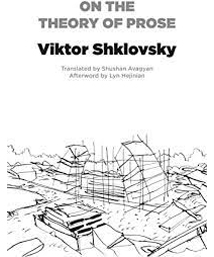

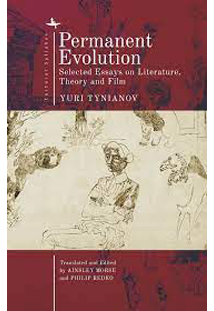

Carroll’s book speaks to two other books I had to have. One is a new translation of Victor Shklovsky’s On the Theory of Prose (1925), the landmark volume of Russian Formalist literary theory. The other is Permanent Evolution: Selected Essays on Literature, Theory and Film, by another major Formalist, Yuri Tynianov. The Formalist school emerged in the 1910s but by the end of the 1920s it had petered out, chiefly because of withering attacks. As the name implies, the Formalist writers were vulnerable to charges of simply chasing after fancy filigree and ignoring the real stuff of art, “content”–particularly its social and political dimensions. (The label “Formalist” was initially applied by opponents; the Formalists called themselves “specifiers.”)

Their work has been periodically rediscovered without ever gaining long-term recognition. René Wellek and Austin Warren’s Theory of Literature (1949) introduced their ideas to the English-speaking world, but the literati played down this aspect of the book. A timid 1956 survey (Victor Erlich, Russian Formalism: History and Doctrine) left many readers thinking that the school was a variant of Anglo-American New Criticism and just as blind to cultural implications. Now Shushan Avagyan’s careful translation of Shklovsky and the superb, refreshingly scathing introduction to the Tynianov collection by Daria Khitrova might change this long-standing bias, but I fear that most readers will consider these writers and their peers relics from a bygone era.

Which would be a pity, in my view. The Formalists changed my idea of film research. Several contributed scenarios to movies, and they composed essays in film theory, but it’s been their literary theories that taught me more about cinema. Now, reading Carroll and rereading Shklovsky and Tynianov have sharpened my sense of what’s valuable in their work.

In their early thinking, their theory of art in general is somewhat vulnerable to Carroll’s Autonomist critique. However, they were evolving away from that sort of purism when they were shut down by political dogma. From another angle, their empirical research into literary forms offers us many tools for understanding films. It’s the difference between a philosophy of art and a conceptually driven criticism.

If you want to be fancy: As an ontology and psychology of art in general, Formalism is problematic. But as a methodological perspective, it’s very rewarding. Or so I’ll suggest.

Getting automatized

Victor Shklovsky and Yuri Tynianov.

In most of the debates about “form,” that usage refers to two aspects of an art work. There is the overall relation among parts of the whole. In music and painting, it’s called “composition,” but the term obviously wouldn’t work for film. So “form” can refer to structural relations at various levels: acts in a play, chapters in a book, phases of a plot, sections of a scene. Then there’s style, the patterned and functional use of the materials of the medium: the arrangement of melodies and harmonies, the use of paint, the organization of film techniques. I’ll mostly refer to both as “form” in what follows, but sometimes I’ll need to refer to them separately.

Carroll argues that as Western science forged ever more powerful ways of explaining the world, some thinkers took art to be “a realm unto itself, apart from the claims of utility, morality, politics, religion and so forth, a realm of art for its own sake.” Hutcheson and Kant developed ideas of beauty and our experience of it as radically distinct from other activities, and Schopenhauer extended these ideas to the realm of art works. The emergence of program music and post-Impressionist painting gave support to the notion that art works are self-sufficient. Now that art was no longer seen as a craft, as the Greeks had believed, it became a source of pleasure in its own right–an attractive idea to bourgeois patrons.

Carroll argues that as Western science forged ever more powerful ways of explaining the world, some thinkers took art to be “a realm unto itself, apart from the claims of utility, morality, politics, religion and so forth, a realm of art for its own sake.” Hutcheson and Kant developed ideas of beauty and our experience of it as radically distinct from other activities, and Schopenhauer extended these ideas to the realm of art works. The emergence of program music and post-Impressionist painting gave support to the notion that art works are self-sufficient. Now that art was no longer seen as a craft, as the Greeks had believed, it became a source of pleasure in its own right–an attractive idea to bourgeois patrons.

This attempt to define the necessary and sufficient conditions of art culminated in Clive Bell’s Art (1914), which argued that the distinctive feature of the art work was “significant form.” Its identity as art depended, in Carroll’s words, “on its internal logic or internal structure.” Bell’s primary concern was painting, in which significant form is “arresting configurations of shape and hue that give a painting its unity.” Representing the visual world is a secondary, non-artistic goal; recognizable things are in a picture only to support its underlying form. As for the viewer, she undergoes an “aesthetic experience” insofar as she has a disinterested appreciation of significant form. Subject matter and theme are at best subordinate, at worst irrelevant, to experiencing form. The art work, and art in general, are in principle autonomous from what Carroll calls “the world of suffering.”

Autonomism has been a powerful influence in modern art, fueling many critical movements, notably musicology, New Criticism in literature, and studies of abstract painting. Carroll allows that it has had salutary effects in encouraging people not to overlook form and style. But he objects to elevating form as the determining factor in a philosophy of art in general.

I’ve had to be too quick in reviewing Carroll’s account, but I think it’s clear that when the Russian Formalists pronounced on art in general they sometimes moved toward autonomy assumptions. Shklovsky once remarked that art didn’t care about the color of the flag flown on the fortress. “By objects of art, in the narrow sense, we mean things created through special devices designed to make them as obviously artistic as possible.” Here we have both the idea of all-powerful form and the aesthetic experience that it fosters.

I’ve had to be too quick in reviewing Carroll’s account, but I think it’s clear that when the Russian Formalists pronounced on art in general they sometimes moved toward autonomy assumptions. Shklovsky once remarked that art didn’t care about the color of the flag flown on the fortress. “By objects of art, in the narrow sense, we mean things created through special devices designed to make them as obviously artistic as possible.” Here we have both the idea of all-powerful form and the aesthetic experience that it fosters.

That experience, though, isn’t operating within a special, remote realm. Shklovsky famously declared that the purpose of art was to “defamiliarize” or “estrange” our perception of the ordinary world. This process doesn’t ease our retreat into a world of “pure form.” It was, he claimed, aimed at returning us to a world we normally did not notice. Habitual actions have made our perception automatic, but art removes this and “makes the stone stony.” His chief example is “Strider,” a Tolstoy short story that takes a horse as its narrator. The horse’s untutored experience of flogging, ownership, and Christian doctrine makes routine human affairs seem alien. Here the idea of “perception” is doing a lot of work, going beyond the stoniness of the stone to local habits and concepts of everyday life.

In the key essay, “Art as Device,” I think that Shklovsky sometimes conflates estrangement as an essential condition of art with estrangement as a particular technique. Most generally, writers use devices like repetition and parallelism with a wilful irrealism that makes us aware of them as “obviously artistic.” Still, the result is that we see what the techniques render in a fresh, “estranged” way. Perhaps this view lies behind the comment made by many viewers of Tati’s Play Time that they can never see an airport or a traffic circle the same way again. This is, we might say, autonomism with benefits: form demands attention in order to renew our awareness of our world.

Tynianov is hard to read, but I think he’s probably best considered more of a functionalist than a formalist. True, he sometimes seems to reduce “content” to formal factors. Anticipating Roland Barthes in S/z, he calls a novel’s protagonist a “semantic unit. . . . a set of heterogeneous dynamic elements united under a single external sign,” such as a proper name. So much for characters as persons!

Tynianov is hard to read, but I think he’s probably best considered more of a functionalist than a formalist. True, he sometimes seems to reduce “content” to formal factors. Anticipating Roland Barthes in S/z, he calls a novel’s protagonist a “semantic unit. . . . a set of heterogeneous dynamic elements united under a single external sign,” such as a proper name. So much for characters as persons!

Yet it seems to me that he did not consider the philosophical essence of the literary work. Every work, he maintained, was a system of elements, each with a distinct function. In some poems, such as Poe’s, rhyme takes a major role; in others, it is secondary or negligible. And the literature of any time itself forms a dynamic system, which is constantly in fluctuation. Genres promote certain elements over others, and over time, genres shift the weight they assign to given factors. At any moment, many trends are active, so that claims that an era is ruled by a certain “tradition” is an arbitrary freezing of the protean literary system.

“Literariness,” a term that the Formalists adopted, looks like the sort of essence that the Autonomist would prize. For Tynianov, though, it isn’t a fixed quality but the tendency of literary works to constantly absorb new materials, cast out old ones, and reassign functions. What drives this process is automatization and defamiliarization, but not quite in Shklovsky’s sense. What gets automatized, for Tynianov, is not everyday perception but a particular form or style. After a few years, analytical cubist painting no longer looks daring, so something new must replace it. A classic can be parodied, which exposes the limits of its techniques and opens the way for alternatives. The literary system changes when conventions of genre, construction, and style have grown stale and the literary milieu (see below) fosters novelty.

In the mid-1920s Tynianov pushed the Formalists toward a more historical conception of how literature worked. Rather than positing a philosophical position, they developed a method of criticism that exposed principles of construction open to change. Even Shklovsky moved toward historical functionalism, as he points out in his (widely misunderstood) apologia, “Monument to a Scientific Error.”

My approach consisted of taking remote examples from literatures of different eras and national contexts and of asserting their aesthetic equivalence. I studied each of these works as a closed system, outside of that system’s correlation with the literary system as a whole and with the primary, culture-forming economic plane.

Empirically, in the process of inquiry into literary phenomena, it became clear that every work exists only against the background of another work and that it can be understood only as part of the literary system. . . .

It became clear that one could not study individual devices in isolation, as all of them correlate with one another and with the literary system as a whole.

Early fruits of this new research program are visible in several Tynianov essays and other pieces by Boris Eikhenbaum, particularly his brilliant O. Henry and the Theory of the Short Story But the program never developed fully. By 1930, the Formalists had lost their institutional support and were obliged to write fiction, biography, and journalism. (Tynianov authored the now-classic Lieutenant Kizhe.) The project of Russian Formalism, as Daria Khitrova notes in her introduction to Permanent Evolution, remains incomplete.

Incomplete, but suggestive. Here are ideas that Kristin and I and others have tried to explore further, in analyzing film rather than literature.

Form vs. content? No, form vs. material

Most centrally, the Formalists challenge us to rethink the idea of content.

The metaphor of “content” makes form merely a vessel for something that’s poured in and stays intact, like coffee in a cup. Shklovsky, Tynianov, and others argued that form was transformative, pervading whatever prior materials we find in the work of art. This is obviously true of, say, music or painting, where stretches of sound and items of the visible world get fundamentally altered by the conditions of the medium. It seems harder to apply to literature, where propositional “content” can simply be stated in a novel or poem: The world is too much with us… But even bald statement is qualified by context and treatment. Shakespeare didn’t say, “Neither a borrower nor a lender be.” Polonius said that, and why should we trust him?

The filmmaker has two sorts of material, I think. There’s the stuff of the audiovisual world, either preexisting (in documentaries and some fiction films) or created for filming (as in animation and some fiction films). Then there’s ideational material, subjects and themes that can serve as material for formal work. Those obviously come from the filmmaker’s experience and from the general culture. The ideational sort of material supplies the film with an “aboutness.”

But ideational material doesn’t come raw to the task. The subject matter comes already conceptually packaged as an issue or problem–teen suicide, homelessness. Likewise, a theme is already shaped as a general topic, maybe as a proverb (There’s no place like home. Just be yourself). And like other materials, subjects and themes become part of a larger construction. The land of Oz tests Dorothy’s proverb by offering an alternative world, while in Hollywood movies learning to “be yourself” often means discovering and developing powers you didn’t know you had.

Ideational material is always filtered through the institutions of filmmaking; topics of race and gender identity are likely to be handled according to prevailing norms. (See below.) For example, narrative form often stages its thematic dynamic through conflict, such as the clash between personal preference and social duty. The plot will find ways to bring out strengths and weaknesses in each and arrive at some sort of resolution, or compromise.

The themes don’t come out unchanged. The Godfather can be said to be about the conflict of family obligation and social morality. It isn’t just about the strength of kinship ties, but the cost they exact in personal integrity. Is family loyalty okay if it leads to murder? Form doesn’t just display themes; it can interrogate them. This especially happens when “symptomatic meanings” are at work.

For examples of how subjects and themes can function in broader patterns, see these entries: “Superheroes for Sale,” “Hunting Deplorables, Gathering Themes” and “Zip, zero, Zeitgeist.”

The importance of norms

Following the Formalists, Jan Mukařovský and other Prague theorists emphasized the role of norms in any art form. (Shklovsky calls them “backgrounds.”) Through craft practice, certain devices become favored because they work on audiences, or because reigning institutions favor them. Happy endings are perennially popular; portraying Christ as a suffering martyr gets approval from Church patrons.

One implication is that norms function as pressure points for artistic choices. There is usually more than one way to do anything, but the range of choice is likely to be constrained. Norms are, I think, like a menu, presenting alternatives but still setting a limit on what can be ordered. Another implication is that norms are variable. A philosophical search for the essence of art is replaced by a methodology that tries to understand principles that inform various periods, schools, and trends. No appeal to “universal laws of art” is necessary, although it can be revealing to find that some norms cut across times and places.

A key finding of the Formalists is that genre norms are very powerful. Even when you’re not doing “genre criticism,” surveying the range of musicals or science-fiction films of a period or place, the concept of genre is fundamental to understanding the form of an individual movie. Shklovsky and Tynianov concentrated on verse genres like the ode and prose ones like the novel. Shklovsky was especially astute in pointing out how conventions of the riddle and the folktale recurred in modern literature. And he noted that genre can override ideology. A Soviet Sherlock Holmes would still need a Watson figure and an incompetent rival (perhaps a bourgeois amateur Lestrade) to build up the mystery plot.

Genre norms can dictate aspects of form. Mysteries demand fairly tight plotting, while coincidences are favored in comedy and melodramas. If they are included in other genres, they usually need extra motivation. But many films include convenient accidents, especially when it can precipitate a climax. Many denouements depend on somebody accidentally overhearing something important or discovering a fateful document, as in Get Out.

Some norms transcend genres, as the happy-ending device does. “What are you doing here?” is a line in nearly every film. Hollywood films rely on some broad norms of plot construction. Kristin has proposed, and James Cutting has confirmed, that many studio films have a four-part structure (Setup, Complicating Action, Development, and Climax), capped by an epilogue. These are based on setting up, modifying, and thwarting character goals. Similarly, many films in all genres rest on deadlines and two story lines (romance/ work or dual romances). Interestingly, norms aren’t always acknowledged by filmmakers when they discuss their work; they’re taken-for-granted aspects of craft.

Because norms offer a range of options, we find variety. Take protagonists. In modern cinema, there can be single protagonists, dual protagonists (such as a romantic couple), or multiple protagonists (as in Love Actually). Occasionally we encounter parallel protagonists (as in Chungking Express). And these devices can be tweaked. Who’s the protagonist of The Godfather? By the end, Michael is clearly the initiator of the major actions, and he has undergone the greatest change; he has a “character arc.” But at the start, and intermittently thereafter, it’s Don Vito who calls the shots. Once he’s sidelined by his wounding and recuperation, Michael comes to assume the protagonist role. When Michael retreats to Sicily, the Don resumes some control, but when Michael returns, he takes over.

The gangster movie often enacts the takeover of a crime empire by a young, audacious and even reckless striver. But in The Godfather it’s not a parvenu displacing a rival but a son replacing the father by jumping the line of birth order. The film has two characters tag-teaming the protagonist function, the purpose being to trace the fluctuations of power and contrast managerial styles. Such variants remind us that filmmakers have flexibility in assigning narrative roles.

There are stylistic norms as well. The clearest example is the continuity system of editing, which has become nearly universal in mainstream filmmaking, and is foundational for alternative practices. Other examples would be three-point lighting, nondiegetic musical scores, and walk-and-talk camera movements. Earlier in film history, there are staging norms associated with 1910s “tableau cinema.” In The Godfather, Coppola follows many stylistic norms of Hollywood cinema, but he also innovates, as when he films the garrotting of Carlo from an unusually forceful position.

Kristin and I have spent much of the last fifty years tracing how stylistic norms came about and how Tati, Ozu, Eisenstein, Dreyer, Angelopoulos, Hou, Wes Anderson, and other filmmakers have created their own variants, which can achieve different effects. Even avant-garde filmmaking has norms, as indicated by the distinct schools which have emerged, such as Expressionism, Surrealism, mythic cinema, Structural Film, and others.

A great many of our website entries illustrate the analysis of norms. Blogs under the categories Narrative Strategies, Tableau Staging, and the topics under Film Techniques provide examples. For a quick sampling, try “Intensified Continuity Revisited,” “Anatomy of the Action Picture,” “Another Shaw Production: Anamorphic Adventures in Movietown,”and the video lecture “CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See without Glasses.” Kristin explains four-part structure in “Times go by turns.” One historical discussion of emerging norms is “Hollywood starts here, or hereabouts.” Recently we posted an entry trying to show how across his career Godard challenged reigning norms of story and style.

Understanding narrative form and style

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (c. 1555) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

Carroll points out that narrative art in any medium poses severe problems for an Autonomist formalist. When artworks tell stories, they recruit form and style to that purpose. The story itself may require knowledge “outside” the work. Carroll points out that we can’t appreciate the form of Bruegel’s painting without knowing the tale of Icarus. That gives force to the figures’ indifference to the thrashing legs in the lower right of the format. Contrary to Autonomists who saw narrative as a pretext or distraction, the Russians’ critical method eagerly sought to analyze how story contributed to form.

In the 1979 edition of Film Art, we introduced the concepts of story and plot as analytical tools, borrowing the Formalists’ distinction between fabula, the causal and chronological tale that is presented in a narrative, and syuzhet, the way that tale is composed in the final text. It was a distinction that most film researchers hadn’t pursued, but we found it very fruitful.

For one thing, it allowed us to show how the effects of a movie were carefully built up through information revealed by the plot. The plot can skip over story events, leaving them to be revealed as surprises later. The plot can rearrange story events, as when flashbacks fill in backstory and flashforwards tease us with what’s to come. Point of view is a central tactic of plot construction; constraining us to what a single character knows can increase mystery and suspense. The plot can control information through spatial maneuvers too, as when the action gets confined to a single space, such as a room (Room) or a police wagon (Clash).

Shklovsky had some very original ideas about plot. Most radically, he suggested we think of a plot as not a harmonious unity but an assemblage, sometimes a rather rickety one. He took Don Quixote as his example, arguing that Cervantes discovered his story in the act of pulling together folk tales, bits of other texts, and clichés of chivalric literature. Even the character of Quixote, he argued, was a mashup of quotations and commonplaces; he’s presented as both foolish and wise.

Shklovsky also emphasized the role of delay, the prolonging of an action beyond simple economy. The hero of an adventure novel is captured, but then escapes, only to be captured again, until it’s convenient to end the plot. Shklovsky related delay to the prevalence of repetition in oral literature: the three trials of a hero, the three roads that can be taken. Along such lines, he found Tristram Shandy, a novel built upon digressions and a constantly interrupted revelation of the hero’s injury, “the most typical novel in world literature.” In keeping with this model, Shklovsky’s essays take off in unexpected directions; his favorite angle is a tangent.

Tynianov picked up on the idea of narrative unity as a tense, even fragile thing, where different components competed for supremacy. In a narrative poem, which will rule: verse or plot? Tynianov’s insistence on dynamism within an art work, as well as among art works, gave him, like Shklovsky, an affinity with the Constructivist movement in the visual arts. The Constructivists stressed conflict among parts–like the Soviet filmmakers’ embrace of the technique of aggressive montage. A narrative, we might say, is a montage of disparate, often ill-fitting parts, and the critic shouldn’t suppress these dissonances in the name of a sacred unity. Part of the point of Bruegel’s picture is the dissonance between a placid landscape and Icarus’ violent death.

Of the many discussions of narrative on our site over the years, “Open secrets of classical storytelling: Narrative Analysis 101” offers an orienting roundup. I try to see a plot as a Shklovskian assemblage in “Pulverizing plots: Into the woods with Sondheim and Shklovsky.”

Motivation and delay

Still, we should expect that style and overall form hang together, and the Formalists weren’t reluctant to point out strategies that make a narrative coherent. Shklovsky noted that disparate plot lines could be tied together through convergence, as when unconnected characters gather at a hotel or inn. This device dominates the beginning of The Godfather, in which Connie’s wedding party brings together most of the major characters and prepares lines of action that will come. We learn of Johnny Fontane’s Hollywood problems, the role of Luca Brasi as muscle for the family, Sonny’s philandering, Michael’s romance with Kay, Tom’s role as counselor, and the gangsters who will become rivals and betrayers of Don Vito. Even the later ministrations of the mortician Bonasera are established through his initial visit to the Godfather. The party serves as the plot’s exposition of backstory and as foreshadowing of future developments.

Another coherence device is parallelism, which Shklovsky made much of. Although a story is driven by chronology and causality, the plot can compare characters and situations. The opening Godfather party draws several parallels, notably with respect to family cohesion. The Don indirectly upbraids Sonny for his infidelity while praising Johnny (“A man who doesn’t spend time with his family can never be a real man”). Crosscutting the erotic song “C’è la luna mezzo mare” with Sonny’s seduction of a wedding guest creates a more localized parallel. In a parallel highlighting contrast, Michael disavows his relatives: “That’s my family, Kay, that’s not me.” As the plot develops, Shklovsky might find the comparison of the Corleone brothers a result of parallelism, as we get to see their differing responses to the crises confronting the family business. A parallel of Don Vito and Michael is given visually, when McCluskey’s brutal punch gives Michael his father’s swollen jaw.

The parallel is capped by the beginning and the ending, with supplicants coming to Don Vito at the party and new followers currying favor with Michael at the close, calling him Godfather.

Yet another way narratives hang together is through motivation, the justification for the presence of some element in the story world or the plot’s presentation. Cinematographers speak of motivated light sources as sources that could plausibly be in the setting. (Such was the motivation for the overhead lighting in those hollow-eyesocket shots in The Godfather.) In general, film style is motivated by narrative demands. You cut to a close-up when you want to emphasize a detail or a character’s reaction. Admittedly, there are today some weakly motivated stylistic choices. Do we really need so many circling tracking shots of characters around a table? Such a whirling shot can be useful showing a character besieged by psychic torments, though now it’s becoming a norm.

Coincidences can be more or less well motivated. If a couple are to meet cute at a coffee shop, you can show them visiting it separately on earlier occasions before they finally encounter one another. Likewise, impossibilities like time travel can be justified simply by introducing into the story world a gadget that permits it. As this example shows, generic motivation can trump realistic motivation.

When it comes to character, motivation is usually a psychological reason for action. Mild-mannered Michael Corleone must become a ruthless killer. How to motivate the change? Well, unlike his brothers, he’s been in the war, so combat may have hardened him. His father has been betrayed and nearly killed. The police are too corrupt to intervene, so he has to protect the old man himself. Sonny is too hot-tempered to lead the family, and Fredo is too weak. And the woman Michael loves, Apollonia, is blown up by confederates of the New York gang. The lesson in Machiavellian intelligence is: Feign cooperation, but be ready to betray. That is: Keep your friends close, but….

Even delay can assist the tighter weaving of form. Here Kristin and I depart a little from Shklovsky. He thought that delay was an artistic end in itself because it prolongs perception, a good thing in itself. In our view, delay functions partly to fill out a narrative to the length demanded. Demanded by what? By the platform or format of the artistic project. A novel needs enough incidents to run 70,000 words or more. A play often demands three acts. A sitcom needs an A and a B storyline to fill out 22 minutes.

Perplexing Plots traces how the demand for novel-length detective stories obliged writers to pad things out with faked alibis, second murders, and false solutions. But “pad” isn’t the right word because delay can function positively, to create gaps that can be filled by other material–subplots, character backstory, diverting byplay, and the like. This happens in conventional Hollywood screenwriting, when story background and comic digressions prolong the Development section before the Climax. Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe novels fill the gaps with entertaining exchanges between Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin, which enrich their characterizations and provide commentary on the action.

Delayed patterns of action can mutually reinforce one another. Each of the four intercut stories in Intolerance delays the plot’s resolution of the others. Similarly, viewers of long-form streaming TV series are familiar with coordinated delaying devices (“streaming bloat”) that tease us to keep bingeing. Through several episodes I kept waiting for the couple in Extraordinary Attorney Woo to kiss. Alongside this delay were major courtroom story lines that held their own interest, so that the romantic interludes served to delay the suspenseful outcome of the cases. And then once the couple kissed, they started to break up–more delay! (But motivated, of course.)

By laying out norms of plot construction, the Formalists lead us to think of how our emotions are recruited. Story/plot maneuvers can build curiosity, suspense, apprehension, and surprise. They can summon up sympathy or turn us against a character who initially seemed admirable. They can create what Meir Sternberg calls “the rise and fall of first impressions.” And they can intensify our appreciation of a character’s emotion. Suppose that Puzo and Coppola had not shown Sonny Corleone ruthlessly ambushed at the toll booth, and that we had only the Don’s grieving appraisal of the body. “Look how they massacred my boy.”

Brando’s acting pierces the heart. But having seen Sonny cut down, we realize that the word “massacre” is metaphorically apt, and we know that the father is looking at a horrendous sight. The plot includes the ambush as a story event not just for momentary shock but as a way to intensify a later spurt of sympathy.

An instance of a tightly woven plot is provided in Knives Out, as I try to show in this entry. On motivating coincidences, there’s “No coincidence, no story.” I try to convert the plot/story distinction into three analytical tools in “Understanding film narrative: The trailer” and “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative.”

Inside/outside

Historically, commentators have distinguished between formalism as an “intrinsic” approach to artworks and alternatives that consider social and cultural factors “extrinsic” ones. But this distinction seems misguided.

It seems that no artwork can be considered as a wholly self-sufficient entity. Noël Carroll’s argument against Autonomism rightly asks what can plausibly be said to be “inside” the artwork. Any representational art refers to persons, places, things, and ideas that exist “outside” it. To talk of characterization we rely on concepts we apply to real people. Moreover, every artwork is connected to other works. To speak of a plot’s protagonist or a climax is to acknowledge patterns of structure that it shares with other narratives. It’s significant that formalism initially gained traction in relation to post-Impressionist art and absolute music. But to identify a painting as a still life or a musical piece as a symphony is to apply a genre concept that extends beyond the individual work.

This shows that it’s not reasonable to charge a formalist approach to cinema with being reluctant to treat culture as playing a determining role in filmmaking and film reception. Cultural factors operate in film form at many levels.

For one thing, cultural ideas function as materials for form to work on. In my book on Ozu I’ve tried to show how his 1930s films dramatize the shortcomings of Meiji ideology and its promises to the Japanese working class. Debates about Hong Kong identity inform police films made in that colony. These are, as we’d expect, presented through characterization, images, or dialogue rather than fully-developed arguments. Carroll has suggested that many films resort to proverbs or clichés to provide thematic nuggets (“Be yourself,” “Love at first sight”) that can be tested by plot action.

Sometimes we can recognize a film’s cultural dynamic when alternatives are suppressed. Kristin’s analysis of Laura in Breaking the Glass Armor points out that one obvious suspect, the artist Jacoby, is never seen because he represents an attractive middle ground between the intellectual Waldo and the cop McPherson, the masculine duality that faces Laura. Likewise, the usual gangster film includes one incorruptible cop, but that option is excluded from The Godfather, the better to center the (relative) source of virtue in Don Vito, who refuses to traffic in drugs and defends family values.

More fundamentally, norms and other principles of form have cultural sources. The well-shaped Hollywood plot grew out of various models in popular literature and theatre. Continuity editing can be traced to schemas in painting, lantern slides, comic strips, and other visual media. To revert to Shklovsky, we can see a film as a package of appeals, archaic plot devices jostling contemporary attention-grabbers, all with roots in society.

The simplest, I think laziest, way to bring cultural factors to bear on a movie is to invoke reflectionism. Some aspect of the film is said to involuntarily “reflect” social ideas. As a result, the door closing on Kay at the end of The Godfather could be said to reflect the patriarchal bias of American society, and particularly of Hollywood. Yet the staging of the scene, as well as the treatment of women throughout the film, would seem consistent with a deliberate critique of the homosocial world of the mafia.

That’s not to say that the film is unproblematically signaling men’s misanthropy. The treatment of Michael’s Sicilian bride Apollonia displays erotic fascination with one conception of naive female beauty, as defined by US culture. (Here again, ideology comes through institutions and iconography.) In other words, social commonplaces are put into play by the dynamic of the overall form. Whenever we say a movie’s cultural resonance is “complicated,” we tend to be saying that various formal pressures are pulling it this way and that. Reflectionism wants a simple flaunting of political views, but form tends to undermine such rigidity.

As a further twist, I’ve argued that the “it’s complicated” cases are themselves strategic maneuvers in having it many ways. Hollywood filmmakers have become adept at presenting mixed messages and heaving the whole thing into our laps for us to sort out. This allows the filmmakers to defend themselves against critiques from many sides while still falling back on the primal cry: “We’re just telling a story.” But this ploy again shows that form is bound by norms, which are mobilized by institutions.

Examples mentioned earlier also try to show how cultural inputs shape artistic form: “Superheroes for Sale,” “Hunting Deplorables, Gathering Themes” and “Zip, zero, Zeitgeist.” Other entries are “Pockets of Utopia: True Stories,” “Welcoming Jews as heroes in alternate 1924 Vienna,” “A24: The studio as auteur,” and Jeff Smith’s masterful dissection of the music cultures informing True Stories, as well as his analyses of Memories of Underdevelopment and Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood.”

Crooks in crooked history

House of Strangers (Mankiewicz, 1949).

Once we admit that we critics are always both “inside” and “outside” the film, institutions have to be acknowledged. Their pressure has been there from the start, in the creation of norms and the setting of platforms and formats. The Formalists were conscious of what they called the “literary milieu,” the ways that social conditions of production and reception shaped the demands put upon writers. If a poem is read in a book, recited in a salon, or declaimed to a crowd, the demands on the poet will vary. A novel published in serialized installments will demand cliff-hanging chapter endings, just like serial TV now.

Milieus of reception constitute subcultures, and these have stronger effects on the work than Culture in general. The subculture of Hollywood favors certain stories and filters out those in circulation that can’t be made to fit. Reciprocally, a work presented in different contexts will encourage audiences to perceive aspects that correspond to their interests. There are as well institutions of reception–megaplex, arthouse, avant-garde venues; critics of various persuasions–and these too make certain aspects of films salient. Watch Rocky Horror Picture Show alone and you’ll notice some pretty square tunes.

Enter history. Early on, Shklovsky saw literary history as a stockpile of devices. Some, such as folktale motifs, were perennial, but others had gone stale and lost their power. An innovative writer could resurrect old techniques and make them seem new. This was the “knight’s move,” the crooked path of history. The son, Shklovsky said, might turn out to resemble not the father but the uncle.

With respect to The Godfather, we might note that while family relations had some role in the classic gangster film, personal ambition seems to have been more dominant. Perverse as it may sound, the domestic tensions and reconciliations of Coppola’s film hark back to the family sagas of the 1930s and 1940s (Four Daughters, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, I Remember Mama) and the Cain-and-Abel rivalries of the 1950s (Winchester 73, East of Eden). Such a hybrid plot did emerge occasionally, as in the fraternal conflict of the crime family in House of Strangers (1949), but it wasn’t common in the era of The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre (1967) and The Valachi Papers (1972). These films emphasized gang warfare and avoided deep plunges into the personal lives of the hoods. Perhaps House of Strangers is the “uncle” of The Godfather.

The radical Tynianov rejected ideas of influence and tradition as too static. For him, historical change was fluctuating, with the entire literary system altered by innovative works but also by shifts in the milieu. He was particularly concerned with the way writers introduced novelty by incorporating the speech of their time. For him, it seems, the social sphere closest to literature was everyday language; here was where we should look for culture’s impact on form.

In cinema, what is the most pertinent and proximate sphere of culture? My hunch is: other media. The press and adjacent art forms feed into film and provide not only cultural memes but also models of form. In Reinventing Hollywood I suggested that in the 1940s new conceptions of structure and style were borrowed from popular literature, theatre, and radio, and then transformed by film treatment. (Reciprocally, these rival media borrowed from film.) The Godfather provides a modern example, being an adaptation of a bestselling novel that was acclaimed as an insider look at organized crime. Still, Puzo and Coppola took the opportunity of the feature-film format to tighten the book’s plot and heighten the theme of family loyalty, not least because they were pressured not to glamourize cosa nostra and omertà or even use the word “mafia.” Cinematic form and institutional norms shaped the cultural givens that founded the project.

There are several entries considering film form’s relation to other media. The general category is here. A provocative example is Kristin’s “The eyeline match goes way, way back.” See also “Eisenstein makes a scene,” “Watching a movie, page by page,” “Beach blanket ballads: SUN & SEA (MARINA),” and “Who will match the Watchmen?”

My examples from The Godfather don’t add up to an analysis; I used them only as illustrations of how pervasive the principles identified are. The Formalists tried to reveal the general principles that guided verbal artists in their creative choices. We can do the same with cinema. The concepts can become tools for finer-grained study of, as Shklovsky might put it, “how X movie is made.” Not how was it made, in the sense of a production history, but how it’s put together to achieve its effects. One of our entries, on La La Land, is an explicit test run.

“The formal method is fundamentally simple,” Shklovsky wrote. “It’s the return to craft.” This perspective not only promises to heighten our understanding of how movies work and work upon us. It also gives us more respect for the skills of the makers. One reason, we think, that working screenwriters and directors sometimes thank us for our writing is that we try to take account of the creative decisions they make, while still considering their choices in a broader historical frame of reference.

Thanks to Noël Carroll for comments on this entry.

Meir Sternberg’s careful critique and revision of Russian Formalism is laid out in Expositional Modes and Temporal Modes in Fiction.

Kristin called her version of Formalism “Neoformalism.” See Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis. I’ve proposed my own variant as a “poetics of cinema.” See Poetics of Cinema and Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema. Both of us are somewhat more functionalist than Shklovsky. Formalist ideas feature in all of my books, not least the forthcoming Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder. Oooh, scary, huh?

Extraordinary Attorney Woo (2022).