Archive for the 'Digital cinema' Category

PANDORA’s digital book

DB here:

Looking back at Kristin’s and my ventures online, I see a gradually expanding series of experiments. Step by step, maybe too cautiously, we’ve moved toward what you might call “para-academic” film writing–a way of getting ideas, information, and opinions out to a film-enthusiast readership whom we hadn’t reached with our earlier work. (Although we’re happy when academics take note of what we do.)

Today we have a new experiment to try. Pandora’s Digital Box: Films, Files, and the Future of Movies is now available here. Backstory follows.

Baby steps, then longer ones

To take another metaphor, we’ve been gradually exploring various niches in the online ecosystem. At first, back in 2000, knowing almost nothing about cyberculture, I dumped my vitae and a little essay onto my brand-new Geocities site. Later I saw the site mainly as a supplement to print publication, a way to add and correct things I’d written in my books Figures Traced in Light (2004) and The Way Hollywood Tells It (2005), along with material we’d included in our textbooks Film Art and Film History. By then I had retired from teaching.

I started to write more online. I began posting long, stand-alone pieces that I couldn’t imagine any journal or anthology publishing. (They’re in the list on the left-hand column of this page.) Somewhere around 2007, after finishing the collection Poetics of Cinema, I made Web publishing my primary expressive vehicle. So when I was asked to write pieces for various occasions, I tried to secure permission to publish them here as well. They too have wound up in the line-up on the left– a little essay on Paolo Gioli, one on Shaw Brothers’ widescreen cinema, and a liner note about The Mad Detective for the Masters of Cinema DVD line. There are more to come in this vein, including a historical survey of how film theorists have drawn ideas from psychological research.

While moving to fill the essayistic niche, we saw archival and revival opportunities as well. Thanks to Markus Nornes, I was able to republish the out-of-print Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema in a downloadable pdf version, with color illustrations. That’s on the University of Michigan Press site. Vito Adiraensens, who made a pdf of Kristin’s Exporting Entertainment, allowed us to post that on our site.

At this point, whole books we’ve done were available online. But those were straight reprints. The next logical step was to offer a revised edition. After the rights to Planet Hong Kong (2000) reverted to me, I decided to update and expand it and add color illustrations. I also decided to ask for money, making PHK 2.0 the only item on the site that wasn’t free. That was an experiment too, to see if the year I spent reshaping it might yield some payback. It did; so far, the sales have covered the costs of design and yielded me a little for my efforts.

Meanwhile we’ve explored the blog niche. Started in 2006, refreshed once or twice a week, our blog has become greatly satisfying to us. This entry is number 499. We’ve treated the blog wing of the site as a sort of magazine, with each entry as a feature or column or festival report or book notes. We write about anything cinematic, old or new, that interests us. The freedom is exhilarating, and we don’t lack ideas. I have a desk drawer’s worth of folders on topics I want to explore.

Nearly all of these are long-form endeavors. Some run to 6000 words. Even our festival reports, which could have been emitted in a flurry of communiqués, are blended into spacious pieces that permit us to compare films or develop a common theme. At a time when everyone declares that attention spans have shrunk to pinpoints, readers have been very patient with us. People still visit our blog, recommend it to others, and even Facebook and Tweet about it. Roger Ebert has been an especially generous supporter. Thanks to the efforts of Rodney Powell of the University of Chicago Press, we gathered some of our entries into a book, a “real” one called Minding Movies, and I’d hope that the length and contextual depth of the pieces gave them some bookish solidity.

Another niche coming up: As virtual books have found a public, I’ve made a book designed primarily for an e-reader.

Not bloviation, blogiation

Last fall, after realizing the scope of the digital conversion of movie theatres, I decided to write a series of blogs about it. I had no fixed number in mind, but I didn’t expect it to run as long as it did. I kept learning more, so the series, called Pandora’s Digital Box, stretched from December through March. I was encouraged by people who praised it in blogs and on social media. I decided to try to build a book out of the pieces.

Some people think that this is silly. One reviewer of our blog book, Minding Movies, wondered why anyone would buy something that’s available for free. More alert reviewers, like Scott Foundas of Film Comment (May/June 2011), understood that some readers don’t like to read long-form prose online, or don’t like zigzagging through the labyrinth that is our site, or want some guidance in selecting what to pay attention to. Moreover, by gathering items topically, the book suggested recurring themes and an overall frame of reference governing what we do. The broad aims of our enterprise aren’t apparent in a daily skim of each entry.

Still, Minding Movies was a varied mixture. Pandora was from the start a more focused series. And we added no new essays for our collection, but I had quite a bit more to say about the digital conversion. So I cooked up new rules for my latest experiment.

1. The original entries wouldn’t be taken down. As with Minding Movies, the entries will remain available online.

2. The book wouldn’t be simply a blog sandwich. I’ve rewritten, rearranged, and merged entries for smoother reading. The topics are more logically ordered, and the whole thing hangs together organically. The blogs formed a kaleidoscope; the book is a narrative.

3. The book would have lots of new material. It includes things I didn’t know when I wrote the blog, ideas that have come to me since, and as much background and context as I could supply. The original blogs amounted to about 35,000 words (enough for a Kindle single). The finished book runs over 57,000 words.

4. It wouldn’t be an academic book. It’s written in the same conversational tenor as the blog. I try not to make anybody’s head hurt. No footnotes, but….

5. The book would exploit online access. The text is unsullied by links, to promote continuity of reading. But a section of references in the back contains citations and hyperlinks to documents, interviews, sources, and sites of interest. This section tells you where I got my information and, if that information is online, takes you there.

6. The book would have to be for sale… Part of this experiment is to see whether I can make back what I’ve spent on the project. I reckon that my travel to theatres and events like the Art House Convergence in Utah, along with other expenses like paying our Web tsarina Meg to polish up my self-designed Word book, comes to about $1200. In addition, I’d like something for my extra time and effort.

7. …but not cost too much. Planet Hong Kong 2.0 runs $15, which I think is a fair price given the cost of designing a book with hundreds of color pictures. But Pandora is a lot simpler and has only a few stills. So I’m offering it for much less: $3.99.

Another Whatsit, but only $3.99

Pandora’s Digital Box: Films, Files, and the Future of Movies traces how the digital conversion came about, how it affects different sorts of theatres, how it shapes the tasks of film archives, and what it portends for film culture, especially the culture of moviegoing.

A key concern was trying to go beyond what I’d already written. For one thing, I try to answer questions I didn’t pursue in the blog entries. How did the major distributors orchestrate the transition? How did they reconcile the interests of the various stakeholders—filmmakers, theatre owners, manufacturers? By 2005, the specifications for digital cinema were established, but the real uptake came five to six years later. What led to the delay? How was digital cinema deployed outside the US? And so on.

Second, I provide background and context for areas I surveyed quickly online. For example, instead of sketching how a movie file gets projected, I take you into a booth and we follow the process step by step. The chapter on small-town cinemas reviews the role of single-screen theatres in the industry. The chapter on art-house cinemas goes back to the 1920s and shows remarkable continuity of taste and business tactics up to the present. Throughout, I consider how the US exhibition system has worked since the rise of multiplexes.

Third, there are unexpected tidbits. How did celebrity directors like Lucas, Cameron, and Jackson spearhead the shift to digital and later innovations? (I touched on that in a couple of recent entries here and here, but there’s more in the book.) Who invented multiplexes? Cup holders? When did those annoying preshow displays start, and more important, who controls them? How do distributors decide whether to release a movie wide or to let it “platform”? Why do art-house theatres serve coffee? There are even a couple of jokes (maybe more unintentional ones).

I think it has worked out well. I’ve tested the text on Kindle, Nook, and the iPad, and it fits very snugly. You just have to import it as a pdf from your computer. On the iPad, it seems to work particularly well with the app GoodReader, which permits smooth searches, easy bookmarking, and quick shifts back and forth.

As I mentioned above, you can go here to order the book. On the same page you can examine the Table of Contents and a bit of the Introduction.

It’s possible that some people might want to make a bulk purchase. Pandora might be used in a class, or given to staff members working at a film festival, or presented to members or patrons of an art house. For such worthy purposes, I can make the bulk price quite low. If you’re interested, please write to me at the email address above.

Self-publication is a risk for both author and reader. If you decide to buy the book, I thank you.

The next logical steps? A new ecological niche? A completely original book online, maybe. Or PowerPoint lectures with voice-over. Who knows? As Jack Ryan says at the end of The Hunt for Red October: Welcome to the new world.

Thanks as usual to our Web tsarina Meg Hamel, who did her usual superb job turning Pandora the Blog into Pandora the Book, and who has set up the payment process to be quick and easy. Earlier helpmates were Vera Crowell and Jonathan Frome, whose efforts in creating this site are remembered and appreciated.

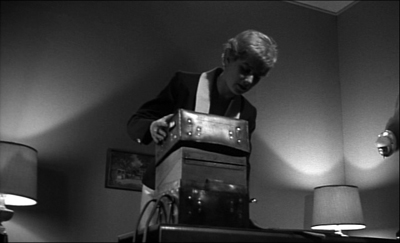

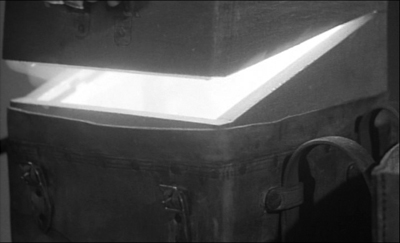

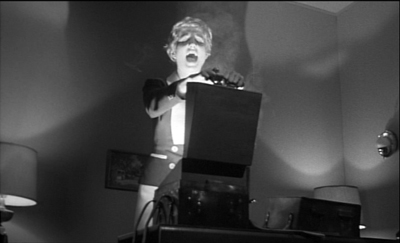

The illustrations are from Kiss Me Deadly and Pandora and the Flying Dutchman, but you knew that. Thanks to Jim Emerson for his suggestions.

The Gearheads

Mourning.

DB here:

At the Wisconsin Film Festival I saw the best film I’ve seen over the last six months. I can’t really say much about it, but I’ll do what I can. My remarks make most sense, I think, if I embark on a pretty long detour.

The frame-rate shuffle

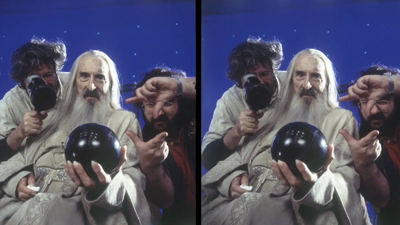

3D still photographs by Peter Jackson taken during the filming of the Lord of the Rings trilogy.

In the wake of April’s convention of the National Association of Theater Owners, the biggest press tumult surrounded Peter Jackson’s ten-minute demo from The Hobbit. Fulfilling what James Cameron had called for at the 2011 NATO confab, Jackson has been shooting at 48 frames per second, and the demo was screened at that rate. Cameron and Jackson are concerned that there’s too much image judder and strobing in digital cinema, especially 3D. They propose a higher frame rate to smooth things out.

Opinion on the Hobbit footage was divided. Some theatre owners and operators were happy with it, but others were uneasy. The higher frame rate tends to eliminate motion blur and create a sharpness that recalls, for some viewers, the brittle look of HD sports broadcasts. “It looked to me like a behind-the-scenes featurette,” said one.

Jackson, who has been preparing for this initiative on his Facebook page, defended his decision. He maintains that audiences will adapt to it, just as his production team has. Many exhibitors seem to have dismissed the new initiative as too expensive, particularly at a time when many are still paying off the digital conversion. But the Regal Entertainment Group, the largest cinema chain in the US, announced plans to outfit up to 2700 screens so that The Hobbit can be screened at 48 fps. It now seems possible that The Hobbit may be shown in no fewer than six formats: 2D, 3D, and Imax, and in each there will be both 24 fps and 48 fps presentations.

Not being present to watch the footage, I have to withhold judgment about how it looks. I haven’t though, withheld my opinion about how Cameron and Jackson, along with George Lucas, have used their roles as superstar directors to prod exhibitors to adopt expensive new technology. They acted as the figureheads for the switch to digital in 2005, using 3D as the incentive for exhibitors to convert. A few years later, after proposing 3D television, Cameron upped the ante by urging higher frame rates for film. Jackson has joined him by actually making a film at 48 fps. Cameron has said he prefers 60 fps, which may mean that the goal posts get shifted again when Avatar 2 or something else comes along.

You can go to my earlier post for more thoughts on their tactics. My book on the digital conversion, due out on this site in a few days, offers a fuller account. In the meantime, I’m going to try to understand this frame-rate fracas in a wider historical context.

The palette

Cinema technology has been surprisingly stable, as befits its status as the last surviving nineteenth-century engine of popular entertainment. The dimensions of the film strip, the rate of shooting and showing, and other fundamental factors have altered relatively little. The coming of sound and then the replacement of nitrate-based film by acetate are perhaps the biggest alterations in the basic technology. Below this macro-level, though, innovation has been constant.

From the 1920s through the 1960s, most of the change came in the production sector. The adoption of panchromatic film stock; color processes, principally Technicolor and the monopack systems like Agfacolor and Eastman Color; the development of various lighting units (carbon-arc, incandescent, Xenon); the shift from optical sound recording and reproduction to magnetic processes; the emergence of different sorts of camera support (varieties of tripod, dollies, and cranes, along with handheld devices)—all of these shaped how movies were made but had relatively little effect on how they were shown.

Some 1950s innovations launched in the production sector, notably widescreen cinema, stereophonic sound, and 3D, reshaped exhibition more drastically, because they came at a moment when theatres were anxious to lure back their clientele. Other revampings of exhibition, like wide-gauge film (65mm/70mm) and Cinerama, were never intended to be the universal standard. They were designed for a distribution system that included roadshow exhibition. Dedicated screens showcased big films like The King and I and Lawrence of Arabia for long, well-upholstered runs before the film hit the neighborhoods and the suburbs.

Producers innovate and exhibitors hesitate. Exhibitors must be cautious and conservative; they risk revamping their venue at great cost only to find that the new technology isn’t catching on. The roadshow system repaid exhibitors well, until it collapsed in response to the rise of saturation booking in the 1970s. For similar conservative reasons, exhibitors looked askance at the digital sound reproduction technologies that emerged from the 1970s through the 1990s. At one point, a house had to accommodate four different sound systems, some of them subject to periodic upgrades.

When technologies emerge in the production sector, they mostly promise to enlarge the filmmaker’s palette. A 1950s film could be made black-and-white or color, deep-focus or soft-focus, with arc or incandescents, flat or anamorphic, and so on.

In practice, of course, not everything was possible on every project. Budgets, as ever, limited options, and many directors and DPs disliked shooting in color or CinemaScope but were obliged to do so. And there were some trade-offs. Filmmakers of the 1930s could not shoot on orthochromatic stock, and after the mid-1950s, it was hard to make a film destined for the classic 1.37 Academy ratio. Still, there were few absolutely forced choices, and many directors explored different options from project to project.

The prospect of an enhanced palette is in fact one reason that some filmmakers embraced new technologies. Sergei Eisenstein (who trained as an engineer) was eager to try out sound, color, and even television because they expanded creative choice. Orson Welles saw in the RKO effects department, which had pioneered sophisticated optical-printer work, a way to create images that couldn’t be generated in the camera. As is now widely known, many of Citizen Kane’s most famous “deep-focus” shots were achieved through special effects. Similarly, Stanley Kubrick renewed the power of his images through his eager adoption of new technologies, including long lenses for Paths of Glory, the handheld camera in Dr. Strangelove, faster lenses for Barry Lyndon, and the Steadicam for The Shining. These filmmakers wanted to multiply options, not foreclose them.

Share our fantasy

The changes that Cameron and Jackson propose are more sweeping. Now that digital projection is an accomplished fact, there will be backward pressure to create a wholly digital workflow. Filmmakers who want to shoot on 35mm will be reminded that they will eventually be fiddling with a digital intermediate, and that the final version will be digital, not film-based. A selling point of digital cinema to the creative community was the promise of complete control over the film’s look and sound, so that the audience gets exactly what the filmmaker envisioned. To assure that integrity, the director will have to shoot and finish the project on digital. That will take away an entire dimension of choice—specifically, shooting on film.

The pressure to shoot 3D adds to this. Martin Scorsese and Ang Lee showed up at the same NATO convention to praise the format. Now films that aren’t tentpole items can be made in 3D, they agreed. According to Variety, Scorsese claimed that “2D projection [sic] will eventually go the way of black-and-white—used primarily as a stylistic choice—as auds will soon acclimate to depth even in indie films.” This sounds like a widening-of-the-palette defense, as does his reaction to new frame rates. “You can do anything you want [in post-production] with that image at that level of clarity, can’t you?”

In contrast to Scorsese’s offhand pluralism, Cameron, Jackson, and their confrère Lucas may be creating a scorched-earth policy. Their conception of cinema, I would say, is now largely that of the Gearhead. Their notion of artistry has become quite mechanical, in that they see progress to depend almost wholly on improved hardware (and software).

They represent three mini-generations of Hollywood techno-lover: Lucas, who began in animation; Cameron, who started as a model-builder; and Jackson, the 1980s fanboy who played with King Kong action figures. They are directors who treat cinema as a delivery system for stories grounded in genre conventions. Fantasy is their touchstone, and realism of any sort bears only on how vividly we perceive the images, not what the films show or say or suggest.

Back in 1999, Lucas noted frankly that film was becoming a form of painting, “unfixing the image.”

You have news footage, you have documentary footage—which are supposedly realistic images—and then you have movies, which are completely fantasy images. There’s nothing in a movie that’s true or real—ever . . . . The people in the movie are actors playing parts. The characters are not real. The sets are not real. If you go behind that door you’ll see there’s no building—it’s just a big flat piece of wood. Nothing is real. Not one little tiny minutia of detail is real.

The Hollywood cinema was then putting fantasy and special effects at the center of its aesthetic, and Lucas understood that every film—action picture, romantic comedy, even dramas—would rely on special effects to a new extent.

Here’s Cameron saying the same thing in defending 3D in 2008.

Godard got it exactly backwards. Cinema is not truth 24 times a second, it is lies 24 times a second. Actors are pretending to be people they’re not, in situations and settings which are completely illusory. Day for night, dry for wet, Vancouver for New York, potato shavings for snow. The building is a thin-walled set, the sunlight is a Xenon, and the traffic noise is supplied by the sound designers. It’s all illusion, but the prize goes to those who make the fantasy the most real, the most visceral, the most involving. This sensation of truthfulness is vastly enhanced by the stereoscopic illusion.

It’s hard to believe that Lucas and Cameron don’t know the long tradition of debate in the arts about realism. Realism can be considered a question of subject matter, plot plausibility, random detail, psychological revelation, and many other things; it isn’t just about trompe l’oeil illusion. Moreover, documentary and experimental filmmakers have suggested that cinema can capture moments of unplanned truth. And André Bazin and others have argued that even when presenting fictional tales, photographic cinema gives us unique access to some essential qualities of phenomenal reality. For Bazin, even an awkwardly shot scene could preserve the sensuous surface of things with a conviction that no painterly manipulation can equal—not perfection but brute facticity. Instead, Lucas and Cameron offer a Frank Frazetta notion of realism: glistening, overripe, academically correct rendering of things we’ve seen many times before.

Turnstile dynamics

NATO’s 2005 ShoWest convention: Lucas, Robert Zemeckis, Randal Keiser, Robert Rodriguez, Cameron.

I see a valid place for a cinema of splendor and spectacle, especially in certain genres. There’s nothing wrong with seeking new methods of pictorial representation, as Spielberg did in Jurassic Park, a genuine triumph of veridical realism. Nor am I trashing Lucas and Cameron wholesale; I admire their early films a fair amount. But they’re forcing their conception of cinema on all filmmakers.

Am I being unfair? I don’t think so. When directors say that digital or 3D or 48 fps is the future of cinema, they’re implying wholesale conversion is in the offing. Although Scorsese says that 2D or another frame rate will remain an option, Cameron and Jackson aren’t quite so open-handed. Because they’re convinced that the result is much more immersive, and immersion is always good, the technology should suit every kind of movie. Cameron again:

It is intuitive to the film industry that this immersive quality is perfect for action, fantasy, and animation. What’s less obvious is that the enhanced sense of presence and realism works in all types of scenes, even intimate dramatic moments.

Both directors usually add that they’re not insisting that every film is suited to the new bells and whistles, that it has to suit the plot and so on—the usual boilerplate about the primacy of “story.” “Stereo [imagery] is just another color to paint with,” says Cameron.

But they sound as if not having 3D or 48 fps puts the movie at a disadvantage. Cameron in 2008:

Every time I watch a movie lately, from 300 to Atonement, I think how wonderful it would have been if shot in 3D.

Jackson in 2011:

You get used to this new look [48 fps] very quickly. . . Other film experiences look a little primitive. I saw a new movie in the cinema on Sunday and I kept getting distracted by the juddery panning and blurring. We’re getting spoilt! . . . There’s no doubt in my mind that we’re headed toward movies being shot and projected at higher frame rates.

As happened before, the pronouncements of the directors mesh well with the initiative of the manufacturers. Back in 2005, Cameron, Lucas, Jackson, Robert Rodriguez, and Bob Zemeckis took to the NATO stage to help sell the Digital Cinema Initiatives program to skeptical exhibitors. Their support (and the box-office numbers of the 3D Chicken Little) aided the projector manufacturers Christie, Barco, NEC, and Sony in rolling out units. The number of digital screens in the US and Canada jumped from ninety in 2004 to over 300 at the end of 2005.

This year, with about two-thirds of all US screens fully converted, Christie circulated a promotional leaflet tied to Jackson’s demo. A few years ago, the future was all about 3D, but now, the text states flatly, “The future of cinema is all about high frame rates.” The cards are on the table.

At just 24 FPS, fast panning and sweeping camera movements that are a critical part of any blockbuster are severely limited by the visual artifacts that would result. . . .

The “Soap Opera Effect” has been derisively used to describe film purist perceptions of the cool, sterile visuals they say is [sic] brought on by digital.

But the success of Hollywood, Bollywood and big-budget filmmakers around the world has little to do with moody art-house films. The biggest blockbusters are usually about immersive experiences and escapism—big, vibrant, high-action motion pictures.

The HFR system, then, aims to spiff up franchises and tentpoles, and all other filmmaking must be dragged along and adjust. Although Jackson says he has heard no plans to charge more for 48 fps shows, Christie thinks we would pay for this treat:

Beyond the simple turnstile dynamics of “must-see” movies, a new, higher standard of movie-going should support premium pricing. Managed right, hotly-anticipated 3D HFR should empower ticket up-charges.

By all signs, the churn won’t stop. “Every three months you’re behind,” says Ang Lee. “We’re guinea pigs.” David S. Cohen, technology writer for Variety, believes that 48 fps is a transitional technology and that 60 fps will win out (“but not soon”). He adds: “Bizzers in both TV and movies are going to be making creative and financial decisions about HFR for years—maybe forever.”

Lucas and Cameron, and then Jackson, grasped that if cinema technology went wholly digital, it would change in fundamental ways. It would turn a medium into a platform, like a computer operating system. The most basic technology of showing a movie would become subject to rapid, radical, ceaseless remaking. It would demand versions, upgrades, patches, fixes, tweaks, and new software and hardware indefinitely.

I’m not sure that NATO’s members have fully realized this. They went into the deal lured by the chance to raise ticket prices and thus offset flat or slumping admission numbers. But attendance is still stagnant, even with the occasional stupendous successes like Avatar and The Avengers. Interestingly, AMC, one of the Big Three circuits that invested heavily in digital projection, is reportedly in talks to sell out to Chinese investors, and other chains are on the auction block. The studios are proceeding with VOD plans that may thin theatrical attendance even more.

Meanwhile, exhibitors face a long future of payouts. When cinema goes IT, as Steve Jobs might put it, we should expect a big bag of pain.

And now for something completely different

I saw Morteza Farshbaf’s Mourning (Soog) on a so-so DigiBeta copy at the Wisconsin Film Festival. This Iranian feature was shot on some godforsaken digital format, certainly nothing that Cameron and Company would approve. For all I know, its camera movements may have strobed unacceptably. I didn’t care.

Cameron et al. claim to worship the god of Story, but no film they’ve made has this subtle a grasp of narrative. Mourning gives us a plot so full of twists—in terms of what happens and how we learn about it—that I can’t summarize even the basic situation without subtracting some of your pleasure. A man and a woman are driving a little boy through a landscape. That’s about all I can tell you.

The film critics at Christie would consider it a moody art-house film. It’s also simple, suspenseful, and surprising, even shocking. It is formally inventive, emotionally poignant, and respectful of its characters and its audience. It is gentle but also unflinching. It’s the closest thing to Chekhov I’ve seen onscreen in a long time.

Was I immersed? Yes, but not in the way Cameron et al. define that state. I was trying to figure out what had already happened, what was happening at the moment, and what might happen next. And maybe I wasn’t seeing things “realistically,” in the 3D sense, but I was seeing something that captured the world we live in—our surroundings (and their stubborn physicality) and our relations to others. That world was also poetically heightened through the most straightforward means: camera placement, lighting, cutting, sound design. The film was, in other words, working in ways that we have always considered central to cinema’s creative mission.

Mourning is part of the fine Global Lens program of circulating features. Here’s a schedule of where and when films in the program are playing. Ask your local festival or art house to book Mourning, or try to see it when it’s available online or on disc. It’s even worth an upcharge.

Lucas’s remarks on realism come from “Return of the Jedi,” an interview with Don Shay in Cinefex no. 78 (July 1999), 18. Figures on the adoption of digital cinema are taken from the report, “Digital Cinema Roll-Out Begins,” Screen Digest (April 2006), 110. A detailed video explaining Hobbit production methods is here, as part of the video diaries on Jackson’s Facebook page. For more from a veteran, see “‘The Hobbit’: Douglas Trumbull on the 48 Frames debate.”

After writing this, I found that Devin Faraci of Badass Digest has a vigorously critical entry on the footage and even calls Jackson and Cameron “gearhead directors.” So I can’t claim originality, but it’s nice to know I have a badass ally.

Thanks to Jim Cortada, author of the forthcoming Digital Flood and Co-Director of the Irvington Way Institute, for explaining IT matters to me.

P.S. 11 May: Christopher Nolan, still embracing film-as-film, claims he’s no gearhead.

Carry me back to the old Virginia

Chaz Ebert and Roger Ebert on the stage of the Virginia Theatre, Ebertfest 2012. Photo by DB.

DB here:

The fourteenth Ebertfest, held in the sumptuous Virginia Theatre in Urbana, had its customary mix of independent films old and new, Hollywood classics (sometimes cult classics), an Alloy Orchestra performance, and some unclassifiable items. It was, as ever, a crowd-pleasing jamboree. It reflected Roger’s eclectic tastes and was brought to us by Chaz Ebert, festival director Nate Kohn, and woman-who-knows-and-does-all-things Mary Susan Britt.

You can see the intros, the panels, and the Q & As—that is, nearly everything, except the movies and the offside fun–on the Festival channel here.

The young and the restless

Kinyarwanda.

First features are a hallmark of Ebertfest, and many have stayed in my memory, among them The Stone Reader (2003), Tarnation (2004), Man Push Cart (2006), The Band’s Visit (2008), and Frozen River (2009). This year there were several feature debuts.

Patang (The Kite) concentrates on a single day in the life of a family celebrating the annual festival of kite-flying in Ahmedabad, India. An uncle has returned to town with his daughter, and usual in such movie reunions, old tensions are reignited. A side-story concerns Bobby, a street-wise local, and a little boy who delivers kites. Needless to say, this story intersects with and sheds light on the primary family conflict.

Prashant Barghava is a pictorialist with an eye for startling color and compositions. Shot in nervous handheld images, with many planes of action jammed together and the camera eye seeking something to focus on, Patang reminded me of The Hurt Locker, but without that film’s sense of ominous vigilance. The tone of this one is more exuberant, and the cast of nonactors gives it vibrancy.

Kinyarwanda, by Alrick Brown and an energetic team of collaborators, explores the Rwandan genocide of 1994 in an unusual way. It displays the role of the Muslim community in protecting the Hutu population (many Christian, some not) from the depredations of the Tutsi death squads. To emphasize the breadth of experience, the film adopts a chaptered network-narrative structure. A Catholic priest, a young woman, an angry Tutsi, a sympathetic imam, a little boy, and a leader of the Rwanda Patriotic Front gradually converge, first in a mosque compound, and ten years later in a reeducation and reconciliation camp. The film also plays with time, replaying some key events—notably the Tutsi’s advance on Jeanne’s home—but also anticipating some outcomes. Interestingly, by showing many of the Tutsi killers in 2004 repenting their crimes before we see those attacks, the film builds a degree of compassion into its overall form.

Scenes with adults are dominated by either personal problems (the Hutu/ Tutsi clash infiltrates a marriage) or discussions of religious doctrine. There are as well wordless moments in which we follow children—a little girl whose Qu’ran has been defaced, a boy who encounters a death squad while sent to fetch cigarettes. If the adults supply the film’s prose, the kids are its poetry.

Patang played both Berlin and Tribeca and will be opening in New York, Chicago, and San Francisco soon. Kinyarwanda won awards at several festivals, including Sundance and AFI Fest, and is coming to several other festivals. It arrives on DVD 1 May.

The misfit section

Terri.

Two other young directors got good exposure. Robert Siegel wrote the screenplay for The Wrestler after working on The Onion (Madison cheer obligatory here). His debut feature, Big Fan, is the story of a football fan who is mangled by his idol and has to struggle against his family’s pressure to sue. Patton Oswalt, who had to cancel his Ebertfest visit at the last minute, played Paul with a potato-like obstinacy that offset the shrieking caricatures around him. On the down side, I could have done with a couple of hundred fewer close-ups. (Watching a movie at the Virginia reminds you of the power of the two-shot.) Still, Siegel wisely doesn’t give his hero a girlfriend who would lead him to the Big Normal and wean him away from his obsession. As Siegel points out, “He’s completely happy, but everyone around him thinks he’s unhappy.” Big Fan is an enjoyable portrait of the sports nerd.

More laid-back was Azazel Jacobs’ second feature Terri. It’s sort of a coming-of-age movie, but it has a peculiar humor that such wistful exercises usually lack. Terri, an enormous teenager, goes to high school in pajamas and is teased mercilessly, but he reacts with a dead-eyed passivity that suggests both resignation and resilience. Like the hero of Gulliver’s Travels, the book Terri is working his way through, he’s tied down by Lilliputians around him, but he gets by.

It’s a film of character revelation rather than plot turns. No, Terri’s addled uncle isn’t going to die; no, Terri’s not going to lose his virginity. The action revolves around Jacob Wysocki as the title character and John C. Reilly, who never disappoints in any film, as the school principal. Their scenes together are the heart of the film, and if Terri is looking for a father-figure/ role model this off-center administrator with a soft heart for hard cases wouldn’t be a bad choice. To the film’s credit, though, we have little reason to suggest that he’s looking for any such thing. This movie has tact.

I ran into another Ebertfest first-time-director, Nina Paley, whose Sita Sings the Blues (2009) I first saw and loved at Roger’s event. Kristin had already seen it at the Wisconsin Film Fest. Sita worked her way into our blog and into our Film Art material. Nina, long a foe of copyright in any form, told me she plans an act of “copyright civil disobedience” soon. In the meantime, check her effervescent blog site, news of her new project Seder-Masochist, and excerpts from her new books about Mimi, Eunice, and their take on IP.

And then there was…

Take Shelter.

The first evening’s late show was given over to John Davies and Raymond Lambert’s Phunny Business, a documentary about the rise of a Chicago comic club, and this was preceded by Kelechi Ezie’s The Truth about Beauty and Blogs. I had to miss the doc, but go here for a review from Scott Jordan Harris. The short was charming—a snappy comedy about a single woman trying to be Queen of All Media on her YouTube show. Very quickly her aplomb cracks and she uses her online persona to recapture her straying boyfriend. Her web skills give her a rostrum, and then a tracking device (she follows him on Facebook), but soon her site turns into a diary of mounting desperation.

Higher Ground: Not a come-to-Jesus moment but a go-from-Jesus one. I had trouble figuring out the tone. I think the obvious caricatures, including an unctuous evangelical marriage counselor, were there to suggest that the ordinary believers were more worthy of respect. But they all gave me the creeps, including the relentlessly sunny pastor. Also, it seemed a bit of a hothouse drama. I missed a sense of exactly where this story took place, and I kept wondering how all these people made a living wage. But of course it’s Vera Farmiga’s film, and as usual she projects a wary intelligence. The opening sequence showing a string of people being immersion-baptized had a winning radiance.

Joe vs. the Volcano: Joe wins the match, sort of. It deserves to be a cult film for its portrayal of a workday out of the dankest basements of Brazil and Hudsucker Industries. Still, I thought everybody was trying a little too hard, especially Meg Ryan. Cinematographer Stephen Goldblatt talked about how he likes shooting on film and showing on digital: Film’s richness can support 4K, 8K, or whatever. As for 48 frames per second: “I can’t wait.”

Paul Cox: On Borrowed Time: A warts-and-all tribute to the stubborn director of over thirty films. I can’t think of a question to ask about Paul Cox that the film doesn’t answer.

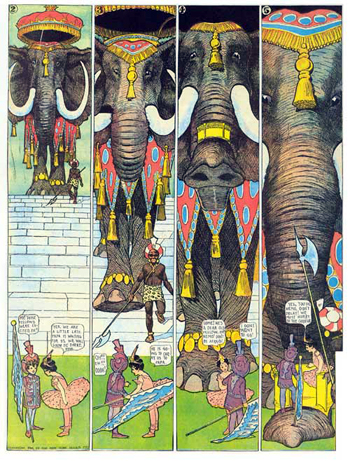

The Alloy Orchestra: Wild and Weird: Classic early trick-films plus a couple of avant-garde items from the 1920s given new brio by the Alloy boys. It was fun but less hefty than earlier efforts. I especially liked re-seeing Winsor McKay’s Dream of a Rarebit Fiend (aka The Pet) from 1921, which replays McKay’s fascination with figures and spaces that swell to mammoth proportions (a bit like Avery’s King-Size Canary), though the effect is less looming onscreen than in the comics. You can see the whole thing, and other of the W & W titles, on Fandor, one of this years E-fest sponsors.

I’d like to see the Alloy talents and others move away from the big spectacles like Napoleon and Metropolis, which appeal to our current tastes in splashy films with special effects, and toward quieter, less-known silent masterworks by the French (e.g., Germinal), the Danes (The Abyss, The Ballet Dancer, The Evangelist’s Life), Italians (Il Fauno, Rapsodia Satanica, Ma l’amore mio non muore) and above all Victor Sjöström. Audiences would, I think, love Ingeborg Holm, Sons of Ingmar, Masterman, and The Girl from Stormycroft, and the Alloyists could do them proud. Not to mention William S. Hart, whose films are among the pride of US silent cinema.

Take Shelter: A tour de force of what literary theorists call the fantastic: Is the hero going mad, or is there indeed something real behind his visions of impending disaster? Everyone has praised, and rightly, the precision of the performances and framings. Jeff Nichols was another first-timer at Ebertfest some years back, with Shotgun Stories. Take Shelter is the sort of movie that makes independent American cinema proud.

A Separation: I wrote about it here a year ago, having seen it during what might be my last visit to Hong Kong. This time around, I admired it all over again. It shows many characters’ attitudes without bias (everyone has his or her reasons), and it’s aware of how lies told out of loyalty corrode love. The screening was enhanced by excellent background information from Michael Barker of Sony Pictures Classics and Omer Mazaffar during the Q and A.

If you’re a good storyteller, I think, you balance straightforward presentation (e.g., A Separation’s exposition, which sketches in the core of a relationship) and somewhat sneaky suppression (e.g., the ellipsis that hides a key event from us). I’ve argued that Iranian directors understand suspense better than almost anybody working today, and this film supports that hunch. Now let’s get hope we get to see, on some platform, Arghadi’s earlier exercise in mystery and ambivalent morality, About Elly. Now there’s an overlooked/ forgotten film.

E-fest goes digital

Ebertfest has shown digital copies of films in the past, notably Bad Santa and Woodstock, but this time around only Take Shelter was on film. Everything else was on HDCam, except Paul Cox: On Borrowed Time, which was on Blu-ray.

James Bond, legendary projection magician and theatre designer/ outfitter, oversaw the shows. Although the films often looked very good on the 50+ -foot Virginia screen, his expert eye saw shortcomings in the digital versions. Even I could detect the videoish quality of Joe vs. the Volcano. It looked pretty good, but compared to what James had shown in years past—70mm prints of Lawrence of Arabia, Play Time, My Fair Lady—there was definitely a sense that we were passing into a new era. Above you see James between his thoroughbreds, the lovingly assembled 35/70mm projectors.

Because Steak ‘n Shake became a festival sponsor this year, Roger presented James with the first-ever S-n-S award, a cap displaying the motto, “In Sight It Must Be Right,” a fitting label for James’ superlative standards in projection. Here he receives the Order of Takhomasak.

James was ably assisted by Steve Kraus and Travis Bird, who is both a musician and a cinephile. Great guys and great professionals, all.

The Virginia Theatre, an analog artifact if there ever was one, is closing after Ebertfest this year. It will be renovated and spiffed up, with new seats and many other upgrades.

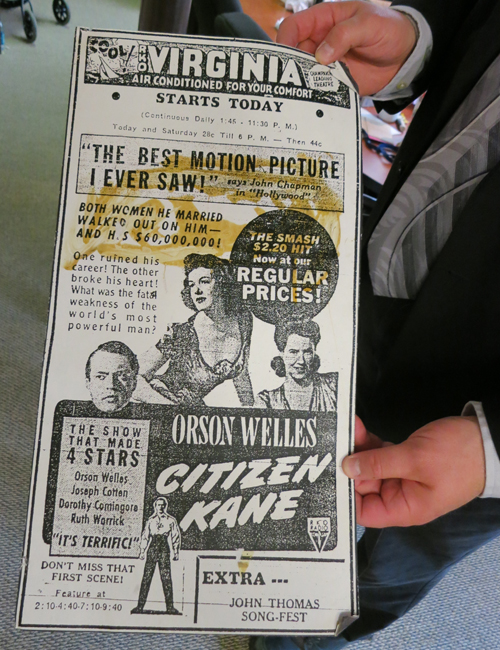

The festival wrapped up with Citizen Kane brought to us digitally. A Blu-ray copy was screened, and instead of the film’s original track, we heard Roger’s pointed and wide-ranging 2001 commentary. He was by this point an old hand at play-by-play explication, after years with his “Cinema Interruptus” series, now taken over by Jim Emerson. After the screening, I was happy to be able to interview Jeff Lerner, of Blue Collar Productions. Jeff produced and recorded Roger’s commentary. Again, check the Ebertfest channel if you want to see the Q & A, which takes off after Chaz’s moving memoir.

Thanks to the many staff and guests who made this year’s Ebertfest especially enjoyable. I’m particularly grateful to C. O. “Doc” Erickson for giving me an interview for an upcoming blog entry, and to David Poland and Michael Barker for enlightening table talk. Thanks as well to Jim Emerson, excellent companion of the highway.

Thanks to Kat Spring and Nate Kohn for correction of boo-boos.

Speaking of digital, here’s a neat possibility: http://gizmodo.com/5906353/the-avengers-screening-delayed-because-some-dunce-deleted-the-freaking-movie.

This deserves a blog entry of its own. The hands belong to Steven Bentz, Virginia Theatre Director, whom we must thank for preserving this ad (from, I assume, 1941). Note the listing of start times for the feature, and the request not to miss the opening. This is a topic discussed elsewhere on this site.

It’s good to be the King of the World

DB here:

Every spring the National Organization of Theatre Owners holds a convention and trade show in Las Vegas. It’s now called CinemaCon, but in earlier times it was known as ShoWest. The gathering assembles thousands of exhibitors from around the world. Directors and stars show up to publicize summer and fall releases. There are screenings, award ceremonies, display booths, and panels about everything from sound systems to popcorn pricing.

The convention is always an extravaganza, but in 2005 things were particularly stirring. Then fewer than a hundred US screens were digital. To ShoWest 2005 came three of the most financially successful directors in history: George Lucas, James Cameron, and Robert Zemeckis. Robert Rodriguez joined them, and Peter Jackson participated in a prerecorded video clip. Their mission: to sell digital cinema.

Battle angels

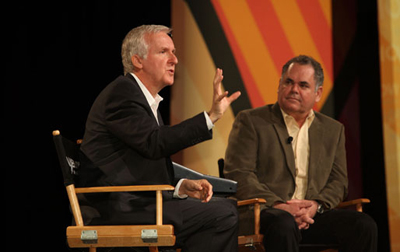

James Cameron and George Lucas at CinemaCon 2011.

Cameron and company knew that the exhibitors needed a rationale for switching that would actually enhance their business. The killer app for digital screening, these directors and others had decided, was 3D.

Lucas claimed that he was hoping to re-release the first Star Wars in 3D in 2007. “We’re giving you two years,” he said pleasantly. Zemeckis announced two 3D films in preparation. In a 3D film clip, Jackson said, “I’m looking forward to one day seeing Hobbits in 3D.” Cameron, who had started working with 3D back in the 1990s, was fresh off the January release of Aliens of the Deep in IMAX 3D. He promised the exhibitors Battle Angel, telling Lucas, “You can have all my theatres when Battle Angel moves out.”

One argument was that 3D offered a way to build the business. 3D screenings would bring in new audiences who seldom went to ordinary movies. More important, the enhanced format would justify higher ticket prices. But of course 3D would necessitate moving to digital projection.

No Battle Angel and no Star Wars IV showed up in 3D, but the celebrity directors kept their word to some extent. Zemeckis led the pack with Beowulf (2007), and Avatar (2009) cemented the deal. With its record $2.7 billion worldwide box office, the latter convinced exhibitors that digital and 3D could be huge moneymakers. In 2009, about 16,000 theatres worldwide were digital; in 2010, after Avatar, the number jumped to 36,000. 3D was the killer app, or Trojan Horse, that pressured exhibitors into going digital.

But here’s the funny thing. At the 2005 confab, the directors summoned up an explanation that goes back to the days when TV threatened the movie trade: You need something special to yank viewers off their couches. In 1953, the bonus was widescreen color images and stereo sound. In 2005, the bonus was stereoscopic projection. All tentpole pictures, Cameron claimed, would be in 3D. “With digital 3D,” he said, “we now have a reason to get people out of their houses from in front of their flatscreen, high-definition TVs and back to the movies.” The premise was that 3D wouldn’t be feasible at home.

Now let’s jump ahead. It’s the 2011 conference of the National Association of Broadcasters. 3D TV is starting to arrive. Celebrity director James Cameron visits with his business partner Vince Case, who have formed the Cameron Pace Group. According to Variety his message to the TV people is:

Your business is about to go 3D. . . . [He said that] the transition to 3D televison as going to happen much faster than usually predicted, even as soon as five years [when] “everything is in 3D and people demand 3D the way people used to demand color, and if you’re not broadcasting in 3D you’re not playing the game and you’re not getting any revenue.”

In 2005 Cameron told filmmakers and exhibitors to shoot in 3D to outrun television. Six years later, when nearly half of movie screens are digital, he advised broadcasters to adopt 3D as fast as possible.

It’s probably not irrelevant that the Cameron Pace Group supplies 3D cameras and assistance to both filmmakers and TV production companies. During the following year, the group announced, it was a 3D equipment provider for CBS Sports and ESPN.

Lest Cameron’s message be missed, he and Pace reiterated it earlier this month. At NAB’s convention he said that sports was only the beginning. Episodic television can also be shot quickly in 3D and easily converted to 2D. Television can’t confine itself to one-off shows or a 3D channel: “We have to hit a critical mass of enough entertainment in 3D.” “The future of 3D,” he told an interviewer, “will be defined by TV.”

Leapfrog

James Cameron and Vincent Pace.

Where does this leave film? Having convinced exhibitors to go digital and to install 3D rigs in their booths, what does Cameron propose to offset the rise of 3D TV? He came to last year’s CinemaCon with a new “incentive”—now all stick and no carrot.

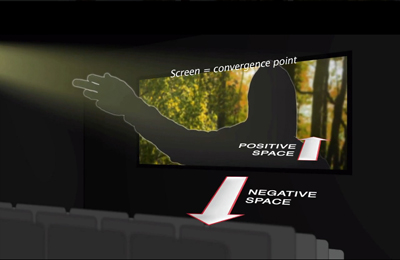

It’s well known that one problem with 3D cinema is a dimmer image. If a vibrant 2D film image is about 16 foot-lamberts, many 3D films are shown at less than four. This turned out to be a problem with screenings of Avatar, which in some venues ran at two foot-lamberts. So Cameron is proposing that exhibitors fit their projectors with gear that permits higher frame rates. Shooting and showing at 48 frames per second (or even 60 fps) instead of the traditional 24 will yield a brighter, sharper picture. Interestingly, 3D TV doesn’t have the same problem with light output, so it’s possible, notes Steven Poster of the ASC, that a 3D HD image would have whiter whites and blacker blacks than a 3D film screening.

Moreover, Cameron prepared a demonstration that showed that in 3D, figure movement and camera movement strobe noticeably at the 24fps rate. They look much smoother at 48fps. This is probably true, but I haven’t noticed problems of strobing in 35mm films by Mizoguchi, Jancsó, Welles, Renoir, and other camera-movement masters. Since they didn’t use our modern 3D, they didn’t encounter the artifacts that Cameron and his peers now brood over.

Having pressured exhibitors to go digital and 3D, Cameron is now asking them to change their equipment to permit him to shoot in a new way he likes better—and to compensate for a deficiency in the 3D system he thrust on them. But he assures them that revamping their projectors is merely a matter of “little tweaks . . . tiny things that make it better.” He has claimed it’s a matter of a software upgrade.

This holds good, evidently, only for the projectors made since January 2010, the so-called “second” series. Projectors made earlier may need replacing. Moreover, one report suggests that the projectors using the Texas Instruments system, the dominant technology in the field, will require not only new software but a new media block. Christie, a major projector manufacturer, says that it will have these available in June for $10,000 apiece.

You have to give Cameron credit for chutzpah. Once more he trots out the argument that theatres have to leapfrog home viewing:

With theatre owners already worried that audiences are abandoning the cinema for the comforts of their home entertainment centers, Cameron argued that exhibitors cannot afford to make the case that “What you’re going to see is special and better than what you have in your home, except the motion sucks.”

The message seems clear. Digital and 3D gave you a competitive advantage for a couple of years, but now it’s time to retool. Those of you who didn’t get 3D along with digital, better start moving, especially if you want Avatar 2 and 3. (Just what Lucas said in 2005 about Star Wars IV 3D, which still awaits us.) And upgrade to 48fps, or even 60. Cameron’s message got support in this year’s NATO convention, when Peter Jackson announced that he’d be trying to induce some theatres to play The Hobbit at 48 fps, the rate at which he’s shooting that 3D production.

Who died and made you King of the World?

I’m left with two observations.

First, there was a time when exhibitors called these directors’ bluff. When Lucas griped that there weren’t enough digital screens for Star Wars: Episode III—Revenge of the Sith (2005), John Fithian, president of the National Organization of Theater Owners, replied memorably: “I don’t put projectors in just for Star Wars.”

Now, it seems, the exhibitors are so scared of missing the next blockbuster that the filmmakers can dictate terms. It’s remarkable that these men can do something neither Griffith nor DeMille nor Disney nor any other powerful Hollywood filmmaker of the classic years dared do. They keep asking that the fundamental technology of cinema be changed so we can all watch a couple of their movies for a month or two every few years.

Second, if these guys are so passionately committed to quality, why don’t they make better movies?

For accounts of Cameron’s 3D explorations before Avatar see Christopher Probst, “Future Shock,” American Cinematographer 77, 8 (August 1996), 38-44; Ron Magid, “Digitizing the Third Dimension,” AC 77, 8 (August 1996), 45-50; Jay Holben. “Taking the Plunge,” AC 84, 7 (July 2003), 58-71; and John Calhoun, “Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea,” AC 86, 3 (March 2005), 58-69.

According to Cameron, he and Vincent Pace, an expert in underwater cinematography, have been working together since 1988. They began building an HD and 3D system in 1999 and finished their first one in 2000. See the GigaOM interview here. In the same interview Cameron mulls over the prospect of 4K television transmission.

A video showing Cameron’s ideas about digital cinema is available at Filmofilia.

As many have pointed out, higher frame rates were argued long ago for film screenings, notably by Doug Trumbull and Dean Goodhill. (See also Roger Ebert on Goodhill’s Maxivision.) Needless to say, Eastman Kodak enthusiastically supported this initiative, since it would step up film consumption.

This entry is a pendant to the series, Pandora’s Digital Box, which ran on this site earlier this year. That series, reorganized and expanded with new material and arguments, will be available in e-book form later this spring.

Avatar.