Archive for the 'Directors: Anderson, Paul Thomas' Category

Hands (and faces) across the table

DB here:

In books and blogs, I’ve expressed the wish that today’s American filmmakers would widen their range of creative choices. From the 1910s to the 1960s (and sometimes beyond), US filmmakers cultivated a range of expressive options—not only cutting and camera movement but other possibilities too. Studio directors were particularly adept at ensemble staging, shifting the actors around the set as the scene develops.

You can still find this technique in movies from Europe and Asia, as I try to show in Figures Traced in Light and elsewhere on this site. But it’s rare to find an American ready to keep the camera still and steady and to let the actors sculpt the action in continuous time, saving the cuts to underscore a pivot or heightening of the drama. Now nearly every American filmmaker is inclined to frame close, cut fast, and track that camera endlessly. I’ve called this stylistic paradigm intensified continuity.

As Los Angeles agent and former editor Larry Mirisch once put it in conversation with me: “They used to move their actors; now they move the camera.” Most of today’s prominent directors prefer kinetic camerawork and machine-gun cutting. This tends to make their staging rather simple and static: we get stand-and-deliver or walk-and-talk (subject of a blog entry here).

The result is a split in contemporary American style. Action scenes are often gracefully and forcefully choreographed (though sometimes the editing fuzzes up character position and overall geography). By contrast, conversation scenes, which could be choreographed as well, are handled either as a Steadicam walk-and-talk or simply as seated actors talking to one another, with cuts breaking up the lines and the camera on the prowl. (I discuss some examples in The Way Hollywood Tells It, pp. 128-173.) (1) You sometimes suspect that today’s directors are most at home shooting lots of people hunched over workstations, making the principal form of suspense a LOADING command.

Don’t get me wrong. Like all styles, intensified continuity isn’t a bankrupt option; many fine directors, from the Coens to Michael Mann, have worked vigorous variants on it. What I’m arguing for is more plurality, more tones in the director’s palette. I’ve revived these cranky ideas in discussing a single shot, this time in Variety. Today’s blog entry expands on that brief piece, so you may want to hop over to it here before reading what follows.

Directing us

One task facing any director is to direct—not only actors but us. The filmmaker must direct our attention to what’s important for responding to the drama at any moment. Since the late 1910s, we’ve known that close-ups and frequent cutting do just that. Tight framings and rapid cuts can steer the audience’s attention through a scene. So the question becomes: How can you direct attention without using close views and fast cutting?

Well, for one thing you can place the main action in the center of the picture format. If there are several points of interest in the shot, which is usually the case, you can arrange them symmetrically around the central zone of the shot—in film, usually an zone just above the geometrical center of the picture format. You can also position your main players so that the most important ones are closer and/or facing toward the camera. By turning a character away from the camera, you can drive the audience’s eye to someone else. There are other pictorial cues worth mentioning (lighting, color combinations, patterns in the set design), but these will hold us for now. Add in movement—characters shifting their position, especially coming closer to the camera—and you have a suite of cues that a film shot can provide.

Apart from these purely compositional factors, you the director can exploit some cues that are part of our social proclivities. When we watch other people, we’re attracted to areas of high information—which, for creatures like us, are faces and hands. Faces send signals about what people are thinking and feeling, with the areas around the eyes and mouth telling us most. Hands are the source of gestures, as well as potential threats. And of course if someone is speaking and others are listening, we are likely, all other things being equal, to look at the speaker.

The crucial fact is that in ensemble staging all these cues, and more, are at work at the same time. The director’s skill is orchestrating them so that they support one another, guiding us to see this or that. (On rare occasions, the director will use them to misguide us, but let’s stick with the default for the moment.) For a long time, filmmakers knew intuitively how to coordinate these cues to create rich and intricate shots; I fear that they no longer know how. (2)

That’s what makes one passage in Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood of interest to me. The scene presents Paul Sunday explaining to Daniel Plainview that there’s oil on his family’s property. Daniel and Paul are bent over a map on a tabletop, with Daniel’s assistant Fletcher Hamilton and Daniel’s son HW watching. The scene is presented in a single shot, with a slight camera movement forward at the start.

The composition could hardly be simpler: four people lined up, three at the edge of the table. The heads cluster around the center of the format, with HW lower and off-center; no surprise that he’s the least important character in the scene (though his question to Paul foreshadows action in the film to come). Paul is explaining where the oil is, and the two men’s faces and hands command our attention as they speak.

Many directors would have cut in to a close-up of the map, showing us the details of the layout, but that isn’t important for what Anderson is interested in. The actual geography of Plainview’s territorial imperative isn’t explored much in the movie, which is more centrally about physical effort and commercial stratagems.

Questioning Paul about his family, Daniel turns slightly away. This clears a moment for HW to ask about the girls in Paul’s family, and for a moment our attention is steered to the right, to pick up their interchange.

Then Fletcher asks about the farm, and as Paul and Daniel tilt their faces to him, he earns his place in the center of the frame. Before, when we could see the faces of the two men closest to the camera, he was subsidiary, but now he becomes salient. On the left, Daniel shifts away uneasily, turning almost completely away from the camera. In answering Fletcher, Paul turns away in the opposite direction, as if shy or guilty; his awkward gesture of stroking his hat seems to confirm Daniel’s doubts about him.

During a pause, Paul turns back to stare directly at Daniel, saying quietly, “The oil is there.” At the same time, Daniel, still turned away, is exchanging a glance with Fletcher. At this point, Anderson’s training of us pays off: we’re ready to detect the slight shift in Fletcher’s eyes, which confirms that Daniel’s looking at him. “Watch their eyes,” as John Ford liked to say.

Paul sets out to leave, and he refuses the invitation to stay the night. At this point comes the scene’s biggest gesture. Daniel raises his hand, in the dead center of the frame.

Spreading his long, thin fingers, Daniel commands our attention. He seems at once to be halting the young man and threatening him. But the gesture becomes the prelude to a handshake. Daniel’s characteristic blend of bluff assurance, friendliness, and aggressiveness are packed into this single gesture. (At the climax, other gestures will recall this one.)

Daniel steps closer to Paul, blocking out Fletcher, to make his threat: If he travels so far and doesn’t find oil, he’ll find Paul and “take more than my money back.” Paul agrees and moves away. “Nice luck to you, and God bless.”

The men watch Paul leave the building. End of scene.

Without any close-ups or cutting, Anderson has skillfully steered us to the main points of the scene, which are carried by the performers. The drama builds through small changes of position, shifts of weight, and facial expressions that accompany the dialogue. (The somber, plaintive music adds an uneasy edge.) Daniel seems more threatening when we don’t see his reaction, and Anderson’s camera forces us to scrutinize Paul’s expressions and body language for signs that this is a scam. It takes confidence to make a raised hand the climax of a scene, but the gesture gains its force by being the most aggressive moment in an arc of quietly accumulating tension.

All the principles involved here—frontality, spacing of figures, slight shifts of compositional focus, actors’ body language—are simple in themselves, but they gain a strong impact by cooperating with one another. The scene’s quiet obliqueness is characteristic of the film, which, at least until the last few minutes, carries us along with hints about where the action might go and what drives its characters.

Yet simplicity shouldn’t imply simplification. Anderson’s willingness to give the shot several points of interest, some more stressed than others, creates an understated tension. The shot’s gravity stems from its conciseness, a quality that Anderson admires in 1940s studio films like The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.

Two more tabletops

The staging strategies Anderson uses aren’t new, as I’ve suggested. They’re part of the history of film as an art form, and many directors have continually relied on them. I don’t think that this is always a matter of influence, although surely filmmakers learned from watching earlier films. Often, directors working within similar constraints intuitively rediscover what other directors have already done.

Consider this scene from Kurosawa Akira’s The Most Beautiful (1944). The setting is a plant where Japanese workers, mostly girls and women, are manufacturing bombsights. The workers have vowed to increase production for the war effort, and they are working to the point of exhaustion. The plant supervisors are worried that the pace will take its toll on the girls.

The scene starts with the eldest supervisor studying the output chart, lying on a table below the frame edge. His colleagues are turned away, at the window. He is the one who must decide how to keep the girls healthy and the output steady. The table and the window will be the two poles of the action, and the actors will oscillate between them. The process starts when the eldest retreats to the window, and one comes forward to study the report.

He’s followed by his opposite number, and they echo one other in rubbing their necks. They’re as tired as the assembly-line girls. Their superior turns and says that there’s no point in lowering the quota because the girls are so devoted that they’d push harder anyway.

The men have turned to listen to him, driving our attention to his centered, frontal figure. After the elder has turned away again, the man on the right says that this might be the critical juncture. Remarkably, all three men remain turned from us, creating a slight pictorial tension.

This tension is extended when the supervisor on the left states his confidence in the children, their team leader, and their teacher. This makes the eldest turn around.

The speaker walks to the window, arguing that the girls will succeed, but the leader turns away again dubiously. He doesn’t offer a decision because an offscreen voice announces that a teacher has come to see them, and they all turn to look.

The factory’s problem isn’t solved; the seesawing of the staging has presented that irresolution dynamically. In a single shot, the difficulty of the administrative decision has been expressed in counterweighted movements in and out, by the figures’ frontality and dorsality. Again, it can seem simple, but where a contemporary American director would have given us a prolonged passage of stand and deliver, with intercut close-ups, Kurosawa has created a little ballet out of the men’s uncertainties. Like Daniel’s raised hand, but with even less emphasis, the assistant’s plea on behalf of the girls’ commitment has gained a subtle prominence. Yet all he has done is walk to the window.

I’m not saying, of course, that Anderson took the idea from Kurosawa. Given the initial choice to stage the scene behind a table, and the inclination to present the action in one shot, both directors spontaneously drew on basic staging principles. This is what film directors have always done. So as a finisher, here’s one last tabletop interlude from Cecil B. DeMille’s Kindling (1915). The entire scene is a dense and intricate affair, but let’s pick just one moment. Maggie has become a servant to a rich woman, Mrs. Burke-Smith, and she’s about to be arrested for theft. Detective Rafferty is ready to handcuff her, but Mrs. Burke-Smith changes her mind.

DeMille arranges his actors so that we can’t miss the rich woman’s moment of decision. She is in the foreground, and her face is in the upper center of the frame. The other actors are blocked, so that her expression is the only one we can see clearly at the crucial moment. Her hand gesture, stretching across the central axis of the frame, confirms that she won’t charge Maggie. (For a similar use of “blossoming” actors’ movements in 1910s cinema, go here and look at Figs. 2A10-2A11.) What DeMille knew, Kurosawa discovered afresh, and Anderson hit upon it again.

Strategies of staging, like other principles shaping how films tell stories, lie behind each concrete creative decision the film artist makes. They run as undercurrents through film history, almost never discussed by critics. They form a body of tacit knowledge, flowing across our usual distinctions of period, genre, director, national cinema. We can trace continuities and changes, examining how the strategies are revived, revised, or rejected. They can provide us with subtle but powerful experiences. They constitute a skill set that is available to filmmakers today. . . if any will, like Anderson, seize the chance.

(1) True, Wes Anderson keeps the camera still, but in his frontal, family-portrait framings the cutting and line readings do all the work; dynamic staging isn’t on his menu.

(2) I survey the development of these and other tactics in Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style. On this site, for one example go here and scroll down to the Bauer material.

I drink your Oscar promo

Kristin here–

A week or so ago, David and I were watching Keith Olbermann’s “Countdown” on MSNBC. As the tagline to one of the stories, Keith quoted, “I drink your milkshake!” David was puzzled and asked why that sentence was suddenly popping up all over the place. I reminded him that Daniel Plainview says that line in the final scene of There Will Be Blood—a film that both of us like very much. That was when I learned that “I drink your milkshake” had entered the buzz of pop culture.

On Saturday, February 9, the new Entertainment Weekly arrived, with a half-page story, “Shake, Shake, Shake,” by Gregory Kirschling, dealing with the milkshake-line phenomenon. (The piece doesn’t seem to be online yet.) Kirschling calls it “one of the strangest exclamations of film history.”

Why so very strange? Odd, maybe, but it makes perfect sense in context. It comes in the film’s final scene, set in the bowling alley of Daniel’s mansion. Naive preacher Eli Sunday has just told Daniel that he should buy a last bit of oil-rich land, whose owner had earlier refused to sell. Daniel replies that he has already extracted the oil from that plot.

The Milkshake Dialogue [Spoilers Ahead!]

Eli brings drinks and sits with Daniel near the bowling lanes, saying, “Mr. Bandy has passed on to the Lord.” He adds that William, Bandy’s grandson, wants to be an actor in Hollywood. Eli offers to help Daniel negotiate with William concerning the land: “Daniel, I’m asking if you’d like to have business with the Church of the Third Revelation in developing this lease on young Bandy’s thousand-acre tract. I’m offering you to drill on one of the great undeveloped fields of Little Boston.”

Daniel replies, “I’d be happy to work with you.” But he adds a condition: Eli must state that he is a false prophet and that God is a superstition. After receiving Daniel’s apparent agreement to financial terms, Eli reluctantly makes these statements over and over as Daniel insists that he speak more forcefully.

After Eli’s declaration, Daniel declares abruptly, “Those areas have been drilled.”

Eli, baffled, murmurs, “What?”

Daniel repeats, “Those areas have been drilled.”

Eli, as before: “No, they haven’t.”

Daniel: “Yes. It’s called drainage, Eli. See, I own everything around it, so, of course, I get what’s underneath it.”

Eli: “But there are no derricks there. This is the Bandy tract. Do you understand?”

Daniel: “Do you understand, Eli? That’s more to the point. Do you understand? I drink you water. I drink it up. Every day, I drink the blood of lamb [or land?] from Bandy’s tract.”

At this point Eli confesses how desperate he is, having sinned and lost his investments. Daniel taunts him viciously, saying that Eli’s twin brother Paul was the chosen one, having taken the $10,000 that Daniel had given him and started a small but successful oil company as a result. (The actual amount handed over in the one scene in which Paul appears was $500.)

Reverting to the subject of the Bandy tract, Daniel continues, “That land has been had. There’s nothing you can do about it. It’s gone. It’s had.”

Eli: “If you would just—“

Daniel, loudly, drooling: “Drainage! Drainage! Eli, you boy. Drained dry. I’m so sorry. If you have a milkshake and I have a milkshake—there it is. [He holds up his index finger]. That’s the straw, you see. [He turns and walks away from Eli] And my straw reaches acrooooooossssss [walking back toward Eli] the room … I … drink … your … milkshake. [He makes a sucking noise] I drink it up!”

Eli: “Don’t bully me, Daniel.”

At this point Daniel throws Eli down, begins hurling bowling balls and pins at him, and finally beats him to death.

The milkshake analogy isn’t all that bizarre. Daniel choses a metaphor for drainage that he thinks Eli can understand.

Beyond that, the milkshake speech is a way of emphasizing Daniel’s delight, not just in making a fortune in the oil business, but in doing so by paying little, or in this case no, money to those whose land he exploits. Stealing someone’s milkshake is a petty form of theft, so Daniel is able to trivialize the removal of oil that Eli has been counting on as his last chance for financial and spiritual salvation. The taunting also allows Daniel to revenge himself for the parallel earlier scene in the church where Eli had forced him repeatedly to confess how he had betrayed his own son. In this final portion of the film, Daniel no longer has any need to put on a friendly face, to pretend to have empathy with others.

Daniel mentions drinking water as well. He’s eating a cold, leftover piece of meat during much of this, and Eli is drinking whiskey. Eating and drinking are common motifs in the film, with elaborate discussions of how the rocky land of the Sundays’ ranch produces no grain but only supports goats. Upon Daniel’s arrival there, the family can offer him no bread but only milk and potatoes.

Thus I don’t think the milkshake line is out of place. That portion of the scene is, however, as Kirschling says, “weird, vaguely hilarious, and unsettling.”

By the way, according to a story in USA Today, director Paul Thomas Anderson derived the dialogue from “a transcript he found of the 1924 congressional hearings over the Teapot Dome scandal.” Sen. Albert Fall described oil drainage thus: “Sir, if you have a milkshake and I have a milkshake and my straw reaches across the room, I’ll end up drinking your milkshake.” He was convicted of taking bribes for oil rights on public lands.

Blenderized by the Internet?

Kirschling points out that the speech has spread far indeed. There’s a YouTube video, “There Will Be Milkshakes,” by Kevin Koonz (spelled Kunze in the EW and USA Today stories). There’s a website, “I Drink Your Milkshake.com,” which started as just a posting of the line and became a forum for discussing the film. The USA Today article declares the line “Hollywood’s Hottest Catchphrase.” There are various designs of T-shirts available on Cafepress and eBay.

It does seem odd that a line from a film that is an art-house favorite, with under $25 million grossed in the U.S. to date, should spread so widely. But these things happen.

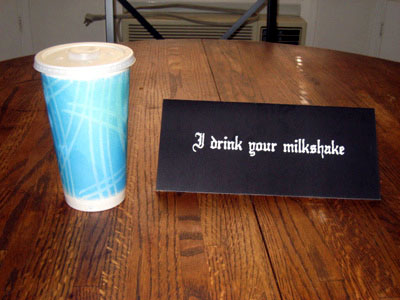

The phenomenon doesn’t stop there, though. On February 8, Variety blogger Kristopher Tapley revealed that he and a friend had received courier-delivered milkshakes with an accompanying promotional flyer for the film. (Presumably Tapley himself is to be credited with the photos above and below. The small print in the lower one reads, “From Your Friends at Paramount Vantage.”)

Upon reading Tapley’s entry, David’s first reaction was, “Where can I get one of those milkshakes?” (I doubt they get delivered here in flyover territory, but the Dairy State can provide its own fine milkshakes.) My first reaction was, “I wonder how soon one of those promo fliers will show up on eBay.” (So far, none has. Just the T-shirts.)

[Added February 12: Apparently there is a hierarchy among the recipients of the Paramount Vantage promo. Tapley specifies that his milkshake came hand-delivered. On February 8, Peter Sciretta posted on the /film site the news that he received the same brochure, but his contained a coupon for a free milkshake (shown in a picture in his entry). He also reveals the brand involved: Cold Stone Creamery.]

Kirschling’s EW piece deplores this sort of thing: “The ironic, Internet-fast catchphrasing of a movie as rich and serious as Blood—and a performance as emotional as Day-Lewis’—is more than a little depressing. It reduces art to a punchline; it puts an epic in a blender and comes out with … a milkshake.”

True, in a sense. But great art has always been subject to humorous treatment and tends to come through unscathed. Marcel Duchamp stuck a mustache on a reproduction of the Mona Lisa and put it in a museum, and the act is considered a daring stroke of avant-garde art. The 1941 comedy Hellzapoppin’ contains a gag about the Rosebud sled from Citizen Kane. There are innumerable examples. The internet has accelerated such of manipulation of artworks and made us more aware of them, but it’s not new—and it is inevitable.

Indeed, the creators of the film don’t seem to be terribly upset. Paramount Vantage obviously seized upon the publicity opportunities, ordering high-quality milkshakes delivered like so many “For your consideration” ads. The USA Today article refers to the director’s reaction: “Not that Anderson minds—or worries that it will undermine the gravitas of the movie, which is up for eight Oscars, including best picture, director and actor. ‘I love the YouTube video,’ he says. ‘It’s completely insane and hilarious. It’s crazy what people latch onto.’”

Anderson is no doubt being polite about the video. It’s a typical hastily made mashup with randomly edited images from a trailer juxtaposed with Kelis’ 2003 song “Milkshake.” As Kirschling remarks, “How original!” But you have to believe that as a result of all the fuss quite a few more people will get intrigued and go to see There Will Be Blood than would have otherwise. They’ll certainly have to sit through the whole thing before reaching the moment they came to savor. And, knowing all of the above, I still was able to re-watch that final scene and find it as chilling as it was the first time through.