Archive for the 'Directors: Bong Joon-ho' Category

PARASITE fever

Kristin here:

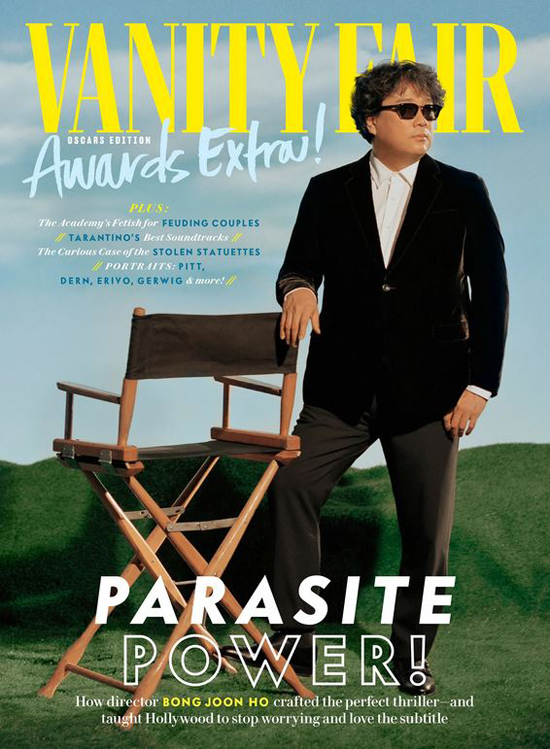

It seems like anyone writing for an online or print periodical, whether media-oriented or not, is searching for some sort of hook on which to hang an article about Parasite and Bong Joon Ho. Some of these are a bit of a stretch, others are a bit ephemeral but interesting. All testify to the surprisingly broad interest in a relatively little-known director of the first foreign-language film ever to win the Best Picture Oscar.

Some of this burst of coverage undoubtedly stems from the fact that relatively few people know anything about Bong. Predictably there are many quick overviews of his career to catch people up, as well as plenty of interviews and of where-you-can-stream-Bong’s-films guides.

Here I offer a some links to a fair sampling of some of the less predictable pieces that I have run across. Some are quite bemusing. A few were published before the February 9 Academy Awards ceremony, but the flood has, not surprisingly, come after it.

Such pieces tend to fall into categories.

Items of Mise-en-scene

People are fascinated by the Parks’ gorgeous (at least on the surface) house and yard. Back on October 31, 2019, Architectural Digest, of all places, published an interview with Bong about the set. This is surely one of the most prestigious of non-media outlets to publish on the film. After the Oscars, The Guardian, which has diligently published on various aspects of the film (see bottom), caught up and ran a piece about the set being the “real star” of the film and considering it from a genre point of view.

The mysterious “viewing stone” has been discussed. The Guardian again (see bottom line of bottom image), on February 17, ran a story entitled “Built on rock: the geology at the heart of Oscars sensation ‘Parasite.'”

The Translator

Everybody seems to be enchanted by Sharon Choi, who has accompanied Bong internationally during the long awards season from Cannes to the Oscars. On February 10, Buzzfeed reported, “There’s a Ton of Love and Memes for the interpreter of ‘Parasite’ director Bong Joon Ho.” Sure enough, all over social media there are people gushing about her (above, from the Buzzfeed story).

On February 18, a Variety headline trumpeted, “Bong Joon Ho Interpreter Sharon Choi Relives Historic ‘Parasite’ Awards Season in Her Own Words (EXCLUSIVE).” Choi had, the story reveals, turned down “hundreds of interview requests” before allowing Variety to print her story. In fact, there are interviews with Choi available on the internet, but the Variety story is not an interview. It’s a memoir by Choi in which she recalls the awards season.

Meta

There are articles about the popularity of Parasite and Bong.

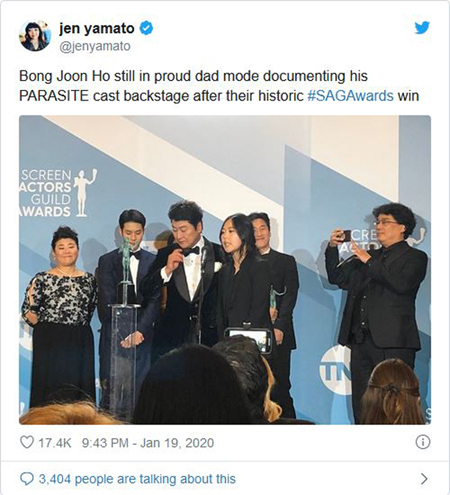

On January 20, into awards season but before the Oscars, Morgan Sung posted a piece on Mashable: “Parasite director Bong Joon Ho became a proud dad meme.” On social media, people were posting photos of Bong taking “proud dad” photos of his cast and crew getting awards (above). Note the number of likes and people “talking about this,” plus the presence of Sharon Choi in the group. The Mashable piece presents several more such snips.

Two days after the Oscar nominations were announced, on January 15 Junkee’s Joseph Earp posted about “Bong Joon-Ho, Viral Superstar,” proposing that Bong has become one of those rare directors who becomes a brand in himself. He picks up on Quentin Tarantino’s remark that Bong could become the new Spielberg.

On February 19, the livemint site reported gleefully that the day after the Oscars saw a 857% surge in searches on “Parasite.” This as opposed to 117% for 1917 and 132% for Jojo Rabbit. As the author remarks, “Bong Joon-ho’s tragicomedy thriller has been sweeping all awards and cleaning up at the box office, and people have not been able to stop talking (or searching) on Google.”

And why? “Search for director Bong Joon-ho increased for not only being the mastermind behind the film but also for his quirky sense of humour.”

I suppose the blog entry that you are now reading falls into this category as well. (And then there are our earlier comments.)

Lessons to be learned

On February 10, one of the odder stories I’ve seen went up on CNBC’s “Make It” page entitled: “‘Parasite’ director says his success is due to ‘a very simple lifestyle,’ not meeting a lot of people.” Why a business-oriented website would consider a South Korean film director’s lifestyle relevant to people aspiring to make a lot of money is anyone’s guess. Clearly CNBC was not able to get an interview with Bong so soon after the awards ceremony. Instead, the insights are derived from an article in the British Telegraph (behind a paywall). That piece is also dated February 10, and since it’s a review (albeit a late one), one must presume that its author had interviewed Bong earlier or derived his information from yet another source.

The Guardian (yet again) ran a story on February 18 headlined “Trust your nose: what rich people can learn from Parasite.” This turns out to be a satirical piece, including such tips as not buying a huge coffee table that intruders can hide under without being noticed.

This ‘n’ that

Even a periodical devoted to cuisine found a way to work in a story. On February 10, the day after the awards, Eater Los Angeles ran a story, “Oscar-Winning ‘Parasite’ Cast Parties Until 5 in the Morning at LA Koreatown Restaurant.” We learn, among other things, that “Bong Joon-ho hadn’t eaten anything all day and was so famished that the restaurant cooked up galbi jjim (braised short ribs), eundaegu jorim (braised spicy black cod), galbi (grilled short ribs), bibimbap, and seafood tofu pancakes for him and the cast.”

On February 15, Indiewire‘s Anne Thompson took us “Behind the Scenes of Bong Joon Ho’s Oscar-Winning PR campaign.” Behind the scenes is publicist Mara Buxbaum, seen above with Bong. To Bong’s left is presumably Sharon Choi, who, Thompson tells us, is writing a book about her experiences as Bong’s interpreter.

I suppose the Parasite fever really does result in part from the fact that this is the first time that a foreign-language film has won a best picture Oscar. It’s probably also to a considerable extent the fact that Bong is a charming person, modest, humorous, straightforward, and very talented, and he comes across as such in his acceptance speeches and interviews. People want to know more about him, as is suggested by looper’s February 12 piece on unknown facts about Bong. If they want to know what his favorite films are and maybe watch them, they can read No Film School’s “25 Favorite Films of ‘Parasite’ director Bong Joon Ho” (February 7).

The only people who dislike Parasite and presumably its maker seem to be President T***p and his gormless fans. On February 20, he decried the awarding of the best-picture Oscar to a foreign film:

And the winner is… a movie from South Korea! What the hell was that all that about? We’ve got enough problems with South Korea, with trade. On top of that, they give them the best movie of the year. Was it good? I don’t know. Let’s get Gone With the Wind back, please? Sunset Boulevard. So many great movies.

I shan’t try to unpack the levels of ignorance and misunderstanding jammed into that passage, which was cheered by many who had never heard of Parasite and had no idea what he was going on about. It does make me pause at the notion of T***p watching Sunset Blvd., if indeed he has, and that he seems to think re-released films are eligible for Oscars decades after they were made. I’ve got to believe he at least knows that Gone with the Wind and Sunset Blvd. have already been “gotten back” and are easily available for viewing in numerous formats. The point though, is that even he has a vague notion that Parasite (or, since he doesn’t know the title, “a movie from South Korea”) is good copy.

Two Parasite items on The Guardian’s February 18 film alert.

Awards! and a very long movie

Bong Joon-ho and team accept Oscar. Photo: New York Times.

DB here:

The big news is that Bong Joon-ho has pulled off a coup. Parasite won four major Academy Awards, including Best Picture–a first for a foreign-language title.

Throughout awards season he was his bemused, genial self, and at the big ceremony he charmed everyone with his easygoing generosity toward Scorsese, Tarantino, and others. He went beyond the standard appreciation for the other nominees by saying something too seldom said at this ceremony of superficial self-congratulation: What matters is cinema, from whenever and wherever.

We’ve been supporting Bong’s work since the first days of this blog, and it was thrilling to see his triumph last night. In homage, we’ve posted some earlier encounters with Bong on our Instagram feed.

Just as exciting were the awards given to another FoB (Friend of the Blog), James Mangold. Years ago I wrote about a visit to the studio where Donald Sylvester and his team were preparing sound for 3:10 to Yuma. What a pleasure to see his work acknowledged with an Oscar. I like Ford v. Ferrari a lot, and much of its impact comes from its sound design and its picture editing (which snagged another Oscar last night, this one to Michael McCusker and Andrew Buckland). Congratulations as well to Mr. Mangold, a fine director.

Usually I’m an Oscar cynic, and not just because forgettable pictures too often claim the top honors and masterpieces are ignored. I had many favorites in the race this year, but I’m happy that filmmakers who have worked as hard to make strong, resonant genre pictures got acclaim this time around.

Usually I’m an Oscar cynic, and not just because forgettable pictures too often claim the top honors and masterpieces are ignored. I had many favorites in the race this year, but I’m happy that filmmakers who have worked as hard to make strong, resonant genre pictures got acclaim this time around.

Less crowded but a big deal for us was another ceremony, held last Friday. Then our colleague Kelley Conway, another FoB, received the Chevalier d’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres from the French government. You know, the same award given to Philip Glass, Tina Turner, Cate Blanchett, Ang Lee, Mia Hansen-Löve, Mads Mikkelson, Sylvia Chang, et al. It was a swell get-together, overseen by Dean Susan Zaeske and conducted by Guillaume Lacroix, the French Consul General for the Midwest.

It was a great moment for us and our department. Kelley’s work includes books on the singer in French films of the 1930s, on Agnès Varda, and in progress, a study of French film culture after World War II. She has also guest-blogged for us (here and here and here).

Score another point for Cinema.

Finally, another big event, which took place weekend before last. Our Cinematheque screened Béla Tarr’s legendary Sátántangó. When we showed it last, intrepid projectionist Jared Lewis handled all those reels. This time, no-less-intrepid projectionist Mike King had to massage a DCP.

In that 2006 screening, there were maybe two dozen people. This time, despite freezing cold, there were over 100. And instead of that number dwindling in the course of the day, the audience actually grew. People came in at the middle and they stayed.

See? It’s just cinema being Cinema.

Thanks to our Cinematheque for its excellent programming, and a special thanks to Tony Rayns, who brought Bong to Vancouver many years ago and enabled me to meet him. Tony has been an untiring supporter of young Asian talent, and our sense of modern cinema owes a great deal to his championing directors in their formative years.

For more thoughts on Béla Tarr, go here.

Tony Rayns and Bong Joon-ho, Hong Kong 2014. Photo by DB.

The trim, tight movie: Three variants at Vancouver

Parasite (2019).

DB here:

As a student of storytelling, I recognize that we can enjoy loose, episodic plots. But I also admire the shrewd craft of constructing a movie that develops a situation in precise, logical, yet surprising ways. Things may be resolved neatly, or not, but the satisfaction comes from the way that characters pursuing goals create conflicts, overcome obstacles, and change (or not) in the course of the action. American studio cinema developed its own version of this in what Kristin and I have called “classical Hollywood” plotting. Other countries have borrowed that model, adapting it to new needs but still keeping the storytelling trim and tight.

Three films on display at this year’s Vancouver International Film Festival illustrate some options. All have won acclaim at other festivals and constitute A-productions in their local industries. I enjoyed all of them, and I liked learning how broad principles of narrative construction can be treated in significantly different ways.

Storming the basilica

François Ozon’s By the Grace of God, a prizewinner at Berlin this year, turns Spotlight (2015) inside out. The American film follows the investigation of a news team bringing priestly pedophilia to light; it’s a detective story, with the victims serving as witnesses to the crime. By the Grace of God concentrates on the victims’ search for justice, and finds an unusual structure to give each one due weight.

The film is based on a real case in Lyon. The film starts with businessman Alexandre Guérin accusing Father Preynat of abusing him as a child. Surprisingly, Preynat admits he did the deed, so there’s no mystery to be solved. With the statute of limitations expired, the Church authorities decline to punish Preynat. He’s kept in service, and his duties still associate him with children. The only thing that worries Cardinal Barbarin is that Preynat didn’t apologize when Alexandre confronted him.

A pious Catholic, Alexandre trusts that if he appeals high enough in the Church hierarchy (even up to the Pope), some action will be taken. He is rudely awakened to the cynical willingness of Barbarin to stall and cast a smokescreen over the case. Alexandre decides to file a legal complaint and to find other victims to join him.

At this point, Ozon’s script takes an intriguing turn. The plot drops Alexandre and introduces us to another victim, François Debord, who is a fairly militant atheist. Investigating Alexandre’s charges, the police call on François’s parents. He told them of the abuse at the time, but they pressured him to stay quiet. Now he embarks on a crusade to find other victims to speak out. For some of them, the statute of limitations may not have expired.

Alexandre becomes a minor player in this stretch of the film, meeting François occasionally to plan strategy, but François is the motor of the action. His zeal leads him to yet another victim, Emmanuel Thomassin. We now follow him and learn how his life has been damaged quite severely by Preynat’s abuse.

Eventually the three men find more victims willing to go public, and by cooperating they confront the Church’s coverup.

With three sections each lasting 45-50 minutes, Ozon has mounted a block-construction plot (although without explicit chaptering). He has compared it to a relay race, with the story impulse passed like a baton from one character to another. And each phase of the action raises the stakes: growing proof of the Church’s malfeasance, a broader survey of the consequences of the crimes.

Ozon has also said that he tried to distinguish each of his three protagonists’ sections stylistically. Alexandre’s phase of action has highly economical narration, using the exchange of letters and emails (read in voice-over) to move the action swiftly, forcing us to keep up at every moment. When the action shifts to the flamboyant, web-savvy François, the emphasis falls on building online support for an organization. Emmanuel’s painful story is treated with more intimacy and empathy; the other men have overcome their childhood traumas and have buoyant families, but Emmanuel is adrift.

By the Grace of God has the carpentered solidity of Ozon’s Frantz (2016). If we can say that the French “Tradition of Quality” of the 1940s and 1950s persists today, it’s surely here in this taut, elegant piece of storytelling.

City on fire

Stylistically, Les Misérables doesn’t look as sleek and controlled as Ozon’s film. It’s shot in the free-camera style that’s now common throughout the world: handheld shots, fast cutting, tight framing on faces, lots of panning to follow the action. When cops brace three women on the street we get a rapid-fire exchange in the manner of Homicide: Life on the Streets.

Although we’re basically on one side of the confrontation, the cutting is somewhat freer than in classic continuity, as the above shot of Stéphane indicates. To emphasize the quasi-sexual gesture of Chris checking the young woman’s fingers for the smell of pot, the editing jumps the line before returning to the main setup.

Les Misérables, directed by Ladj Ly, is not quite as pure an example of the free-camera approach as Young Ahmed, (also shown at VIFF) because it affords a greater degree of “camera ubiquity.” It crosscuts among lines of action, and it relies on reaction shots that the Dardennes avoid. Still, the purpose is to immerse us, smashmouth fashion, in each scene’s conflict.

And there’s plenty of conflict. Stéphane Ruiz has joined a team of tough cops patrolling an impoverished Parisian suburb teeming with immigrants. To keep things under control Chris, the team leader, has formed alliances with drug gangs and the boss of the territory. Gwada, a Muslim cop, backs Chris loyally.

The main action, which consumes around 24 hours, shows Stéphane trying to bring a measure of humanity to the confrontations between his unit and the local residents. A petty crime escalates into a burst of police brutality, captured on video by a boy’s drone. The second half of the film puts the cops in conflict with one another and an increasingly outraged community ready to take on both the police and the gang leaders.

Ly has made short films and web videos, and while growing up in the banlieue projects he documented police actions.

For five years I filmed everything that went on in my neighborhood, particularly the cops. The minute they’d turn up, I’d grab my camera and film them, until the day I filmed a real police blunder.

Ly filmed the 2005 riots as well (365 Days in Montfermell), as part of the filmmaking collective Kourtrajmé. Les Misérables is called that partly because this is the district where Hugo wrote his masterpiece. “I wanted to show the incredible diversity of these neighborhoods. I still live there: it’s my life and I love filming there. It’s my set!” In 2018 Ly established a filmmaking school in Montfermell.

Although Ly comes from the world of documentary, he has a shrewd sense of fictional plotting. A prologue shows little Issa among thousands of Parisians celebrating France’s World Cup victory (above). It’s an image of diversity within national unity, but also a bit of narrative priming that makes us sympathetic to the boy. The rising tension of the action, from a childish prank through increasingly horrific scenes (one in a lion’s cage had me trembling) to a final cataclysm, is carefully constructed out of a series of misunderstandings, brutal decisions, overreactions, and desperate survival maneuvers.

There’s solid motivation and foreshadowing. The drone is established early as the all-seeing eye of the projects, steered by the withdrawn boy Buzz. Stéphane has reluctantly transferred to the Parisian police from the provinces because he wants to be near his son, in the custody of his ex-wife. This information prepares us for his sympathetic gestures toward the children of the projects. And just before the climax, Ly’s script gives us a pressurized nighttime pause, a sequence that cuts among all the adults we’ve seen trying to adjust to the day’s turmoil. Next day all hell will break loose.

Les Misérables shared the Jury Prize at Cannes last May with another VIFF entry, Bacunau. (Comments on this coming soon.) In the US it will be distributed, who knows how, by Amazon.

Class struggles

Viewers of Memories of Murder (2003), The Host (2006), and Mother (2009; also here) know that Bong Joon-ho has a fine hand with mystery, suspense, and abrupt plot twists. His skill is on full display in Parasite, Palme d’or winner in Cannes and already considered one of the most striking films of 2019.

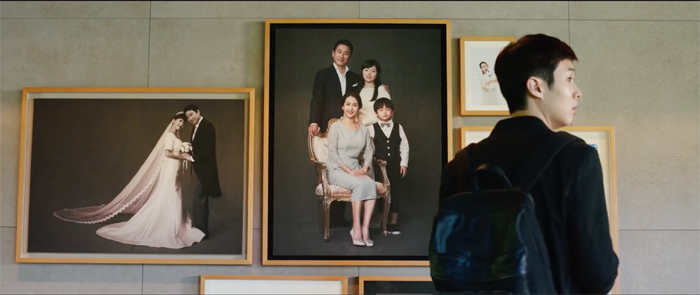

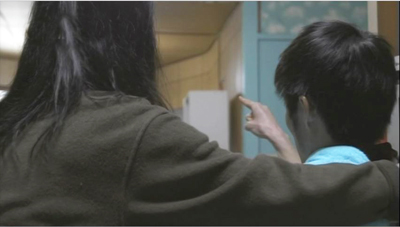

As suits the Age of Inequality, the action centers on two families. The Kims live in a crammed basement and struggle to get by. When the son Ki-woo gets a job tutoring the daughter of the rich Park family, he schemes to insert all his family members into the household. (This recalls the stratagems of the play and film Kind Lady.) The Kims’ adroit manipulation of the Parks, especially the insecure helicopter mom, provides mordant comedy. But in a long central scene, the Kims’ scam starts to unravel. They’re shocked to discover what actually goes on in the splendid mansion they’ve taken over.

Bong’s skill in shooting, staging, and composition seems effortless. Neither as academic as Ozon or as nervous as Ly, his deliberate style makes every sequence build to a neat point. The contrast between the Park house, perched high on a hill, and the Kims’ basement apartment, is echoed in vertical camera movements that carry us up and down through locales. (Here, in more instances than one, the poor live underground.) Parasite‘s opening camera setup, a view of the street through the Kims’ window, recurs at various points to mark stages of the action. Here nighttime violence erupts in the street outside.

The Kims’ barred view contrasts with the spacious picture window at the Park mansion. Fussy as ever, Bong places a comparable shot of the Kim window at the very end.

Bong plants significant motifs through the film. He forgets nothing. Cub scouts, Morse code, peach allergies, and the smell of poverty pay off in comedy while supplying thematic resonance. The parallels between the married couples are enhanced by the introduction of another husband and wife who have launched their own desperate scheme. The climax, an orgy of rich folks’ complacency, brings all together in a shocking but not ultimately surprising confrontation.

I had almost called this entry “The well-made movie,” indicating not only my praise for the films but also their kinship with the dramatic tradition of the “well-made play” (pièce bien faite). That was one powerful set of principles for plot-building. If you construe that form narrowly (as the Wikipedia entry does), these films don’t completely fit it. I think that Ibsen, Shaw, and those who followed owe more to that form than is generally admitted.

In any case, the impulse toward tight construction, full motivation of characters’ actions (usually guided by a goal), and a rising arc of conflict leading to a decisive climax–these design features, so manifest in the well-made play, have carried over to the cinema since the rise of the feature film in the 1910s.

Today’s films have a look and feel that seem of our moment, but their underlying “engineering” principles are surprisingly indebted to a long-running tradition. Those principles can be deployed, revised, and reversed in a great many ways–as these three films show.

We thank Alan Franey, PoChu Auyeung, Jenny Lee Craig, Mikaela Joy Asfour, and their colleagues at VIFF for all their kind assistance. Thanks as well to Bob Davis, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Tom Charity for invigorating conversations about movies.

For more on the general principles of “classical” construction, see this entry on The Wolf of Wall Street. In our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema Kristin traces some literary and dramatic sources of the format.

On the “free-camera” shooting style, see our blog entry on Toni Erdmann (viewed at VIFF back in 2016). We discuss the emergence of the technique in Chapter 25 of the fourth edition of Film History: An Introduction.

By the Grace of God (2019).

Here be dragons, and tigers

Revivre.

DB here:

My first visit to the Vancouver International Film Festival back in 2005 was at the invitation of Tony Rayns, programmer of the Dragons and Tigers series. That series included both new films by established directors and a batch of first or second features by beginners. Tony asked me to be on the jury for the young D & T award.

I enjoyed working on that jury, which consisted of old friend Li Cheuk-to of the Hong Kong Film Festival and new friend Gerwin Tamsma of the Rotterdam fest. We gave the prize to Liu Jialin’s Oxhide, and it’s been gratifying to track her career since. In the course of my stay I realized what an excellent festival Vancouver had, not least because of the warmth and enthusiasm of its staff.

My Vancouver experience helped launch this blog, which really got under way during my second visit, in several entries in 2006. That was also the year I met Bong Joon-ho, who was at VIFF with The Host. I kept going back, and Kristin began joining me, so every year we’ve been writing about this admirable event.

During that 2006 festival Tony decided to rearrange his commitment to Dragons and Tigers. He turned the curating of Chinese-language films over to expert programmer Shelly Kraicer, who was living on the mainland and had excellent contacts within China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Now things have changed again. This year the festival accepted fewer beginners’ features and folded them into a broader international competition. One of the Asian films in the collection, Rekorder by Mikhail Red, tied with a French entry, Miss and the Doctors, for the award. In the old days, the winner received a cash prize; alas, that benefit has not been retained, but maybe some far-sighted patron will step forward to give the award a little more heft.

There were fewer D & T titles overall this year, but I still found several of great interest. Herewith some notes on them.

Time, and time again

Revivre.

If your movie is going to include flashbacks, you have a choice among several standard ways of motivating them. You can use the very old device of presenting an investigation or trial, in which the film translates testimony into dramatized scenes. Or you might frame the flashbacks with a scene of a character who thinks back on events in the past. Three of the Dragons and Tigers films used some other common flashback setups, but treated them in fresh ways.

Im Kwon-taek’s Revivre (Hwajang, his 102nd film!) starts with another canonical flashback situation. In fairly washed-out footage a funeral procession crosses the screen. A man at the head of the group looks back and sees a beautiful young woman looking gravely at him. Immediately the film triggers questions: Whose funeral is this? Why is the young woman important?

The rest of the film fills us in via flashbacks,. The protagonist, Oh Sang-moo, is a manager of the advertising section of a cosmetics company. His wife is stricken with a brain tumor and he cares for her as best he can during her years of surgery and recovery. At the same time, he develops a restrained affection for Ms. Choo, an employee in his division. Eventually Oh’s wife dies and there is the lingering possibility of his starting his life afresh with Ms. Choo, whose phantom face we’ve seen in the procession. Threaded through this are the pressures of a business deadline, his need to keep his staff on track, his occasionally fraught relations with his daughter, and his wife’s adamant insistence that after she dies he keep none of her things, not even her beloved dog.

The film scrambles the order of Oh’s experiences. After the funeral, within about five minutes we get a scene of Oh’s wife dying in the hospital, then a scene of his own medical problems, and then the moment that Oh’s wife collapsed in the garden, yielding the first sign of a tumor. The rest of the film gives us incidents from all phases of their last years together, with emphasis on his careful attention to her bodily functions. Although his daughter finds the task repellent, Oh changes his wife’s diapers and cleans her private parts with the same calm professionalism that he brings to the meetings in his company. In all, the non-chronological flashbacks work effectively to show Oh juggling the pressures of business with the demands of his family situation.

What makes Im’s treatment a little unusual is that the flashbacks aren’t presented as Oh’s memories. They are rearranged by the narrational authority of the film itself, rather than by situations that provoke Oh to recall this or that incident. We’re restricted to Oh’s range of knowledge throughout, but that doesn’t draw us closer to him. We have to read his mind through his expressions and his gestures, and these are often severely controlled. A master of the poker face, this executive keeps a polite distance from everyone, including the viewer. Is he one of nature’s stoics? Or is he emotionally detached, attending to his dying wife more out of duty than love?

These questions are partly answered by some brief fantasy scenes in which Oh visualizes Ms. Choo as a romantic partner. She seems to intuit his interest, and responds through small signals. When she starts to reciprocate more explicitly, Revivre returns to its mood of impassive sadness for its final scenes.

Time and freedom

Hong Sangsoo has been playing with time from the start of his career. He has tried replays from different viewpoints (The Power of Kangwon Province, 1998), replays that differ in details (The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, 2000), odd déjà-vu experiences (Turning Gate, 2002), and all manner of theme-and-variations plotting (as noted on this blog here and here and here). So it’s a bit surprising to find him exhuming the old reliable setup of letters recounting events in the past. Yet here as ever he has a couple of tricks up his sleeve.

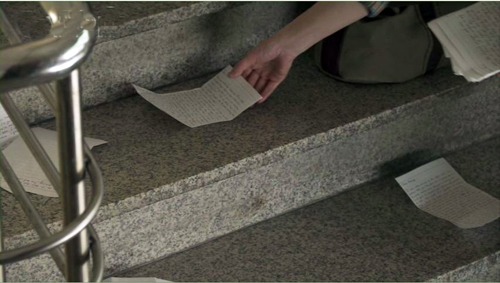

Like Im, Hong has scrambled the flashbacks in Hill of Freedom, but he offers a comically exact motivation. Kwon, a young language teacher in Seoul, returns to find a sheaf of letters written to her by a Japanese admirer, Mori. He taught with her at the school two years earlier. He has come to Seoul to reunite with her, and he has left her a letter every day. She starts to read them in the school lobby, and Mori’s voice-over narration establishes the beginning of his story. He tells how he found lodging, left a note at Kwon’s apartment, and paid his first visit to the “Hill of Freedom” café.

So far, 1-2-3 preparation. But when Kwon starts to leave the language institute, she staggers on the staircase, as if stricken, and scatters the letters on the steps. She gathers them back up in random order. This sets up the scrambled timeline of the flashbacks to come. (Hong mischievously zooms in on a letter she fails to retrieve, hinting at a gap in the story that will follow.)

What Kwon learns, in mixed-up order, is that Mori’s search for her leads him to meet and hang out with his landlady’s nephew, while also becoming romantically involved with Youngsun, the café owner. In the grip of a possessive lover, Youngsun attaches herself to the fairly passive Mori. Their affair plays out in Hong’s usual mix of drinking bouts and pillow talk.

By the time we’re used to this pattern, Hong sets up a new game. As he keeps cutting back to Kwon reading through the letters, accompanied by Mori’s voice-over, Hong gradually reveals that she is reading them in the Hill of Freedom café—the very place Mori hoped to meet with her (but never did).

Eventually, Kwon steps outside for a cigarette, and we suddenly get her voice-over remarking that the last letter was postmarked a week ago. Has Mori then already left and stopped writing? At this point Kwon encounters Youngsun coming in, and they greet each other as friendly acquaintances. The next scene finds Kwon visiting Mori’s guest house.

What happens there shifts the ground under our feet. After talking with friends, I think that we can’t be sure about what’s actually taking place. A mysteriously bruised cheek, a surprise reunion, and the return of Mori’s voice-over fill the penultimate scene. The coda is even more of a puzzler, at least to me. (I wonder if it’s the scene described in the letter that Kwon didn’t retrieve.) In any event, Hong’s usual themes of the foolish arrogance of Korean men and the comedy of male-female interactions are given new expression in this lightweight but enjoyable movie. The fact that Hill of Freedom is mostly in English, which Mori must employ to communicate with the Korean characters, adds to the fun.

Video virus

Yet another trigger for a flashback can be provided by a crisis situation. It might be rather near the story’s climax, so that we are left hanging and the plot takes us back to the origins of the problem. This is what we get in movies like The Big Clock (1947), which starts with our hero hiding out from the police and wondering how he got in this pickle. Or the crisis situation may come earlier in the story, with the flashback again filling in what led up to it before continuing the situation presented in the frame.

This latter option is followed in Mikhail Red’s Rekorder. After a brief prologue showing violent acts captured by CCTV cameras, we are in a police van with stern cops chatting about killing a dog before we’re introduced to the shaggy, wasted protagonist Maven riding with them.

From this framing situation we flash back to the reason Maven is in the van. Once a cinematographer in the glory days of Filipino cinema, he’s now a loner using his ancient camcorder to film movies in theatres and sell them to a friend who bootlegs DVDs.

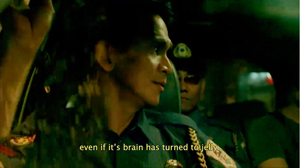

Maven is a compulsive recorder. As the director puts it, he is “a ghost in the city observing everything through his lens.” So naturally he’s filming when a street gang kills a young man in front of a crowd who simply watch. Maven doesn’t volunteer his footage, since it includes part of a movie he was pirating. But now he’s been nabbed and is riding to headquarters with the cops, who are very curious about what’s on his tape.

Much of the rest of the film involves Maven’s attempt to keep the cops from examining his footage, while he agonizes about his passive acceptance of street violence. There are still more flashbacks, appropriately presented through old video footage of his wife and daughter. Not until the end of the film do we witness–again, on CCTV footage–the trauma that has turned him into the burnt-out case he is.

Mikhail Red commented that he was inspired to make Rekorder by a viral video in which a youth was shot in the street by thugs and a big crowd didn’t intervene but instead filmed the murder. He staged his own CCTV-style video to supply the denouement, and was shocked to find that it was appropriated in documentaries about street crime. Through a multimedia format, Rekorder updates the sort of social criticism that Raymond Red, Mikhail’s father, brought to Filipino cinema of the 1980s. That era as well is evoked through another sort of flashback, the clips from classic movies that Maven films. “I wanted,” Red says, “to pay homage to the pioneers.”

Straight time

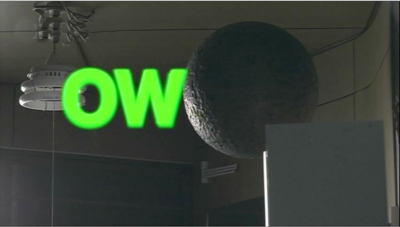

You don’t need to play time tricks to create an uneasy movie. Ow (Maru) presents a typical family squeezed by Japan’s economic stagnation. Dad pretends to have a job, when he actually sets out each day for the unemployment office. Mom and grandma putter about. Grown but spacy Tetsuo lounges about his room talking baby talk. One day, when his girlfriend has just snuggled into bed with him, they are transfixed by a big gray-brown sphere that drifts into his room.

Transfixed, literally. They freeze upon seeing it. So does Dad, and so do the cops who are called. Director Suzuki Yohei introduces us to the big ball with a shot of it slowly spinning, held long enough for us to get slightly hypnotized too. There follows some comic suspense in which people enter the bedroom and may or may not leave. The biggest tease is the reporter who, after learning of a death during the sphere’s arrival, researches the case and then lunges into the room, ranting about a police cover-up.

The tension–will others fall under the spell or the sphere?–is accentuated by shrewd camera setups. When the cops arrive, we get a low-angle shot behind Yuriko and Tetso, showing the frozen cops and a new one not yet transfixed. He pushes one stiff colleague over, revealing the ball, still hovering there, and we wait for him to be the new victim.

Much later, when the reporter first visits the room, the sphere has vanished. But a rhyming angle forces us to remember its presence, and to let the reporter–the source of the plot’s momentum for the rest of the movie–take the place of the hapless cop.

Finally, for another exercise in unkinked time, there is the Korean action picture Haemoo. Produced by Bong Joonho, it centers on the desperate captain of a fish-trawler who agrees to bring illegal immigrants into Korea. Everything that could go wrong does: storm, fog, Coast Guard patrols, a horny crew, and an idealistic novice seaman who tries to protect a woman. Everything, including the accident that creates a horrifying midway turning-point, is carefully prepared in the film’s opening scenes. The film’s second half locks us into the relentless consequences of covering up a huge crime.

The pace is so snappy that I expected lots of cutting, but I counted only about eight hundred shots in 106 minutes. (The Equalizer, only twenty minutes longer, has three times that number.) I attribute this cutting rate to neatly functional direction, with no fuss or waste. The ship’s engine room is a cramped set, hazy with steam and dust, and the shots there are finely calibrated to build the drama through depth, fluid camera movement, and our old friend The Cross. The randy engineer’s business of checking the equipment carries him from one side of the shot to the other, while the young seaman shifts around him–first on frame right, then on frame left, then in the center.

The plot has that satisfying neatness that is characteristic of Bong’s work, and its forward thrust has no need of flashbacks. We can’t ask for backstory when the upcoming twists are as fast-paced and exciting as they are here. Dragons and Tigers has always showcased not only the experimental films like Ow and Hill of Freedom but also the crowd-pleasers, and Haemoo (which translates as “Sea Fog”) solidly fulfills that mission. Long live linearity!

Hill of Freedom has sharply divided critical opinion. Richard Brody considers it a masterpiece; others consider it fluff. At Fandor David Hudson painstakingly surveys the cut and thrust of the controversy.

Hill of Freedom.