Archive for the 'Directors: Borzage' Category

Glancing backward, mostly at critics

DB bere:

As Freud’s mom says in Huston’s film, “Memory plays queer tricks, Siggy.” Herewith, some journeys into the past, launched on a lazy June afternoon.

Ten-best lists are nothing new. The New York Times ran them in the 1930s. Here’s one for 1940 (NYT 29 Dec 1940, p. X5).

The Grapes of Wrath, The Baker’s Wife, Rebecca, Our Town, The Mortal Storm, Pride and Prejudice, The Great McGinty, The Long Voyage Home, The Great Dictator, and Fantasia.

The author’s runner-up titles include Of Mice and Men and The Philadelphia Story. Pretty tasteful by today’s standards, no? Who came up with a list including Hitchcock, Borzage, Sturges, Pagnol, Chaplin, Disney, Milestone, Cukor, and Ford twice?

None other than Bosley Crowther, long-serving Times reviewer who became the emblem of middlebrow taste in endless polemics (including some I’ve mounted). Who knew he was a closet auteurist?

Winchester ’73 (1950).

Now try this one.

The movies live on children from the ages of ten to nineteen, who go steadily and frequently and almost automatically to the pictures; from the age of twenty to twenty-five people still go, but less often; after thirty, the audience begins to vanish from the movie houses. Checks made by different researchers at different times and places turn up minor variations in percentages; but it works out that between the ages of thirty and fifty, more than half of the men and women in the Unites States, steady patrons of the movies in their earlier years, do not bother to see more than one picture a month; after fifty, more than half see virtually no pictures at all.

This is the ultimate, essential, overriding fact about the movies. . . .

Yes, another oldie, this time from Gilbert Seldes’ book The Great Audience (1950). What we’ve been told for years was characteristic of our Now—the infantilization of the audience—has been in force for at least sixty years.

By the way, here are some US features released in 1950: Father of the Bride, Gun Crazy, House by the River, In a Lonely Place, Julius Caesar, Mystery Street, Night and the City, Panic in the Streets, Rio Grande, Shakedown, Stage Fright, Stars in My Crown, Summer Stock, Sunset Blvd., The Asphalt Jungle, The Baron of Arizona, The File on Thelma Jordan, The Furies, The Gunfighter, The Third Man, Twelve O’Clock High, Union Station, Wagon Master, Where the Sidewalk Ends, Whirlpool, Winchester ’73, and probably some other good movies I haven’t seen.

Perhaps not a luminous year, but I’d settle. Especially compared with 2010. Did kids just have better taste then?

Beyond reviewing

Most people conceive a film critic as a film reviewer. The review is a well-established genre, and we all have its conventions in our bones. At a minimum, you synopsize the plot, comment on the acting, mention the pacing or the cinematography, throw in some wisecracks, and recommend or condemn the film. Good reviewers do these things well, but the genre remains a limited one.

Crowther was a reviewer; Seldes was something more. But how to define that extra something? Two long-lived heavyweights can help us.

In the 1935 essay “The Literary Worker’s Polonius: A Brief Guide for Authors and Editors,” Edmund Wilson spells out what he takes to be the duties and genres of literary labor. At the time, the “New Criticism” in the universities had barely gotten started, so most literary criticism Wilson encountered was journalistic and belletristic—that is, reviewing.

Accordingly, Wilson distinguishes different types of reviewers. There the people who simply need work. There are literary columnists who pump out observations on the latest books. There are people who want to write about something else; that’s when you use the book under review as a pretext to ride your hobby horse. There are the reviewer experts, as when a philosopher is called in to review a book of philosophy. Then there’s the rarest, the “reviewer critics.” Here is why such creatures are rare.

Such a reviewer should be more or less familiar, or ready to familiarize himself, with the past work of every important writer he deals with and be able to write about an author’s new book in the light of his general development and intention. He should also be able to see the author in relation to the national literature as a whole and the national literature in relation to other literatures. But this means a great deal of work, and it presupposes a certain amount of training.

In sum, the best critic has to be very, very knowledgeable. But is knowledge enough?

T. S. Eliot, it’s often said, believed that the only qualification of a critic is to be very intelligent. (One example of this claim is here.) What Eliot actually wrote is more interesting. His 1920 essay “The Perfect Critic” is considering Aristotle as a theorist of literature. Of The Poetics he notes:

In his short and broken treatise he provides an eternal example—not of laws, or even of method, for there is no method except to be very intelligent, but of intelligence itself swiftly operating the analysis of sensation to the point of principle and definition.

The final clause is a good description of what I take “poetics” to be as applied to film. We analyze effect (“sensation”) so to discover not laws but principles (governing a genre, a trend, a style, whatever) that we in turn articulate (“definition”). In this analysis, we don’t use a method—that is, I take it, a prior commitment to a system of thought that blocks our seeing the object in its own terms.

Contrary to the common modern view that our personal feelings and ideas color everything we think about, Eliot seems to advocate a more objective way of thinking. Aristotle the theorist is praised because “in every sphere he looked solely and steadfastly at the object.” His search for the principles underlying tragedy, comedy, and epic is contrasted with the dogmas of Horace, the “lazy critic” who offers us precepts, tips from the top about laws to be obeyed. (Sound familiar from screenplay manuals?)

Aristotle, Eliot thinks, was endowed with “universal intelligence”: “He could apply his intelligence to anything.” Such a gift overrides the sort of specialized inquiry that yields “methods.” I read “The Perfect Critic” as recommending that critics try to combine their sensitivity to nuance with Aristotelian intelligence:

Aristotle had what is called the scientific mind—a mind which, as it is rarely found among scientists except in fragments, might better be called the intelligent mind. For there is no other intelligence than this, and in so far as artists and men of letters are intelligent (we may doubt whether the level of intelligence among men of letters is as high as among men of science) their intelligence is of this kind.

This is what it is to be “intelligent” in Eliot’s sense: to be wide-ranging, rigorous, and committed to understanding the artwork both as unique object and embodiment of principle. He finally spells it out in his praise for the Symbolist Remy de Gourmont:

Of all modern critics, perhaps Remy de Gourmont had most of the general intelligence of Aristotle. An amateur, though an excessively able amateur, in physiology, he combines to a remarkable degree sensitiveness, erudition, sense of fact and sense of history, and generalizing power.

So Wilsonian erudition and historical knowledge aren’t enough. You need sensitivity, “a sense of fact,” and “generalizing power”—the ability to see larger implications and principles at work in what you’re writing about. In short, the best critics don’t shy away from probing ideas.

The general go

Where do the ruminations of Wilson and Eliot leave us with writers who go beyond reviewing? Let’s go back to Seldes.

He became one of our best American critics, in fact one of our first media critics, thanks to his “generalizing power.” The 7 Lively Arts (1924) was a trailblazing defense of Tin Pan Alley, comic strips, vaudeville, jazz, and films. Reacting against “genteel” taste, Seldes believed that the bursts of exaltation to be found in the “minor” arts were as profound as anything to be found elsewhere. “Our experience of perfection is so limited that even when it occurs in a secondary field we hail its coming.” Such perfection is to be found, he says, in an instant in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, when Cesare seizes Jane and the bed curtains snag her gown. He starts with what Eliot called “sensation,” the piercing arousal.

A moment comes when everything is exactly right, and you have an occurrence—it may be something exquisite or something unnamably gross; there is in it an ecstasy which sets it apart from everything else.

But Seldes goes beyond noting moments that give him a buzz. He tries to explain how and why the vulgar arts can arouse us. It’s hard for us now to realize that what we take for granted as vital popular culture was scorned by the much of the intelligentsia. In 1924 Seldes set out on a crusade to convince his readers that the Keystone Kops, Flo Ziegfeld, Irving Berlin, ragtime, and Fanny Brice offered more of genuine artistry than the Bogus Arts (we’d say middlebrow) that were then ruling high culture. In 1924, this was a thunderbolt:

The daily comic strip of George Herriman (Krazy Kat) is easily the most amusing and fantastic and satisfactory work of art produced in America today.

If the best critics offer not only opinions but information and ideas to back them up, The 7 Lively Arts had both in abundance. Seldes begins the book with the suggestion that the consolidation of the film industry, and particularly the establishment of Triangle, Kay-Bee, and Keystone, was the turning-point in the history of American film. But instead of the usual litany of praise for Griffith’s and Ince’s discovery of “cinematic” storytelling, Seldes condemns them as too quickly seduced by extravagant spectacle. The journeyman Mack Sennett stuck to making “the most despised, and by all odds the most interesting, films produced in America. . . . He is the Keystone the builders rejected.” Far more than the work of Griffith and Ince, Sennett’s comedies exploit what cinema is best suited for: chases, crashes, explosions, “locomotives running wild, yet never destroying the cars they so miraculously send spinning before them. . . . And all of this is done with the camera, through action presented to the eye.”

Seldes wrote about radio, dancing, and other pastimes, but films were his special love. An Hour with the Movies and the Talkies (1929) and The Movies Come from America (1937) combine historical knowledge with subtle appreciation of the forces operating on studio picturemaking. These books thrum with ideas. For instance, Seldes defends the director as the key creative artist in cinema. One reason is that only the director can control pacing.

The director is responsible for the general go of a picture, for making it run off neatly, for controlling the speed of its various parts, for seeing that a romantic episode does not race along while a melodramatic conversation lags. He is, or ought to be, responsible for the interruptions of the main action of the picture so that a comic interlude is not placed too near to the climax of a tragic one, but only near enough to give more intensity to the emotion.

What about the camera? Hollywood movies, he says, have developed a rapid-turnover tradition that favors conciseness and novelty in the flow of images.

When Van Dyke in 1934 [in The Thin Man] wished to show a familiar event in the life of any man who walks a dog—an event which, although familiar, might not be passed by the censors—he merely showed the leash tightening and the hand of the man being jerked back; then the man stood still and a little later the same operation was repeated. . . . The part not only takes the place of the whole, but is more effective because the imagination of the spectator supplies what is missing.

Seldes might have added that once we’ve supplied that missing piece, we laugh at Asta’s ability to puncture Nick Charles’ serious disquisition on murder.

Seldes became a tamer thinker later in life. By the 1950s he was part of the media establishment, producing television shows on culture. He grew disappointed with the film industry, leading to his critiques in The Great Audience. Still, his critical skills persisted. His next major book, The Public Arts (1956), pins his hopes on television but also offers a balanced account of Hollywood’s widescreen revolution. Confronted with CinemaScope and its kindred systems, he worried, again, about pacing.

Wherever the movie touches time, it as mysterious and primordial as the beating of the heart. Absorbed in new techniques, directors may neglect essentials as they did a generation ago when they immobilized the camera to favor the microphone; but, as they recovered mobility then, so I am confident that they will recover the art of using and manipulating time in the substructure of their pictures.

Although he’s seldom discussed in film circles now, Seldes stands out as a worthy critic not because of one-off reviews but in virtue of his pointed, sometimes daring ideas, his knowledge, and the zest they arouse in the reader. These are the payoffs, I think, when a critic leaves reviewing, even the 10-best lists and other fun parts, behind.

My quotations from Seldes come from The Great Audience (New York: Viking Press, 1950), 12; The 7 Lively Arts (Mineoloa, NY: Dover, 2001), 204, 309, and 5; Movies for the Millions (London: Batsford, 1937), 75; The Public Arts (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1956), 55-56. For more on Seldes and his milieu, see Michael Kammen’s excellent intellectual biography, The Lively Arts: Gilbert Seldes and the Transformation of Cultural Criticism in the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996).

My quotation from “The Literary Worker’s Polonius,” comes from Edmund Wilson, Literary Essays and Reviews of the 1920s and 1930s (New York: Library of America, 2007), 490.

Although the terminology is different, Eliot seems to be advancing something similar to Kristin’s arguments about film analysis in the first chapter of Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988).

The Thin Man (1934). Seldes forgot that it was Nora, not Nick, who senses Asta’s response to the call of nature.

Arrivederci Ritrovato

The three chiefs of Cinema Ritrovato: Peter von Bagh and Gianluca Farinelli strategize, while Guy Borlée does some heavy lifting.

Our last days at Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato were as busy as the first ones. Inevitably, choices, choices. Invasion of the Body Snatchers in a rare SuperScope print, or Asta Nielsen as Hamlet? Emilio Fernandez’s melodrama Enamorada (1946) or a 1907 version of Little Red Riding Hood, with a big dog playing the Wolf? You can’t see it all, but we offer some notes on some of the choices we made.

I can’t say that I am a great fan of Frank Borzage’s films of the 1930s and 1940s. For me his great period was the mid- to late 1920s. 7th Heaven (1927) somehow manages to climb beyond its blatant sentimentality, much as the hero and heroine ascend the stairs of their tenement apartment house, and earns our emotional investment in their transcendent love. For me, Lazybones (1925) and Lucky Star (1929) were the revelations of the Borzage retrospective during the 1992 Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone. It is a true pity that both remain largely unknown.

Borzage’s No Greater Glory (1934) was shown in a stunning print supplied by Sony Columbia. It didn’t fall into any of this year’s themes but was simply one of the “Ritrovati & Restaurati” items. The film deals with rival youth gangs in Budapest who organize themselves along strict military lines. Purportedly an anti-war tale, it manages to make the self-imposed discipline and even gallantry of the boys seem almost redemptive. I found the young hero, a scrawny but brave lad who struggles to be worthy of promotion within the ranks of his chosen gang, a bit too calculated to tug at the heartstrings. Still, it was entertaining, and the print showed it—and especially Joseph H. August’s cinematography—off to the best possible advantage. (KT)

While Kristin was watching Borzage, I decided to revisit Ilya Trauberg’s Goluboi Express (1929), one of the least known of the Soviet Montage films. Like Pudovkin’s Storm over Asia, it’s an attack on Western imperialism. Chinese, many sold into servitude, are packed into the rear cars of the train, while colonialists loll around up front. Two western soldiers of fortune attack a Chinese girl, and a young Chinese tries to defend her. This launches a prolonged battle and chase while the train roars on. By 1929, Trauberg had absorbed the lessons in cutting taught by Kuleshov, Eisenstein, and Pudovkin, and he adds his own imaginative touches. The taut construction and torrential editing (over 1400 shots in less than an hour) create an electrifying experience.

This particular version is an intriguing rarity. In his introduction, Bernard Eisenschitz explained that Soviet authorities persuaded Abel Gance to distribute the film in France. Gance recut it to avoid censorship, and he commissioned musical accompaniment by Edmund Meisel, the experimental composer who scored Battleship Potemkin. Meisel’s score amplifies and sharpens Trauberg’s hammering visuals. (DB)

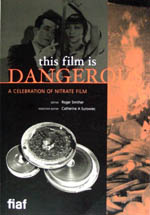

The book room was running for only about half the festival, so I was glad I nabbed my consumer durables early. Many high points, including a fascinating DVD collection of Marey films, but the most memorable, if only because of the struggle to carry it back home, is This Film is Dangerous. Published by the International Federation of Film Archives, this colossal book appears to present everything you wanted to know about this incendiary filmstock. It includes discussions of how nitrate came to be an ingredient of film, how the nitrate preservation movement (“Nitrate won’t wait”) started, case histories of restorations, poems in praise of nitrate, a chronology of nitrate fires, and an anonymous contribution called “Nitrate Pussy.” In all, virtually a film geek’s bathroom book, although its bulk demands a large lap. It doesn’t yet seem to be available on the FIAF website, but it should be soon.

Speaking of swag and plunder, Dan Nissen of the Danish Film Institute kindly gave me a copy of their latest DVD publication, the first of several volumes devoted to Jørgen Leth. It’s a handsome production and sure to increase interest in the man behind The Perfect Human and the target of Lars von Trier’s painstaking abuse in The Five Obstructions. It’s available at the DFI website. (DB)

Although Michael Curtiz’s 1929 epic Noah’s Ark has been shown at various festivals in recent years, I somehow had always managed to miss it. Perhaps this was just as well, since the print shown in Bologna as part of the salute to Curtiz is longer than most and has the original sound restored from the Vitaphone records. (More often the film has been shown in its silent version.) Piecing together bits from several release prints held in different archives, something approximating the 1929 release version has been reassembled and matched to the sound. The credits in the program—“Print restored by YCM laboratories, funded by Turner Entertainment Company and AT&T in collaboration with La Cinémathèque Française and The Library of Congress”—hints at the complexity of the task.

Like The Jazz Singer and other early talkies, Noah’s Ark has long stretches of purely musical accompaniment. At intervals, though, characters suddenly start speaking, usually at the lugubrious pace typical of performances at the dawn of sound. The effect is startling, especially when the transition happens within a scene. Such switches proved jarring to the reviewers of the day, but the chance to see a film hovering between silent and sound can be fascinating to a modern viewer. The pacifist message of Noah’s Ark reflects a general anti-war sentiment in Hollywood films of the 1920s and 1930s—a healthy reminder of a day when the majority of good, patriotic Americans could take a dim view of warfare. The film’s ending, in fact, optimistically declares that the Great War had put an end to all wars. (KT)

Having written a book on Ernst Lubitsch’s silent features, Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood, I was particularly interested in a dossier on the director. It included a reconstruction of Die Flamme (1922), of which only one reel survives, using publicity photos, set designs, and descriptive intertitles. Though still short at only 44 minutes, this version gives a good sense of the plot, which was certainly not evident from the existing footage.

We have long known that Lubitsch’s intended first project in Hollywood was to be a version of Faust with Mary Pickford as Marguerite. That fell through, but it went far enough that screen tests were made. Twelve minutes of tests for a series of actors trying out for the part of Mephistopheles were shown. These were not exactly a revelation, but they do shed light on this transitional moment in the director’s career. (KT)

What do we do with a terrible movie by a sublime filmmaker? I’d argue that at least three directors achieved greatness in the years before 1920: D. W. Griffith, Louis Feuillade, and Victor Sjöström. Sjöström’s Ingeborg Holm (1913), Terje Vigen (1917), The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), The Outlaw and His Wife (1918), and Sons of Ingmar (1919) remain deeply moving and cinematically inventive. Sjöström moved smoothly from the fixed camera, long-take “tableau” style of the early 1910s to profound mastery of continuity editing on the US model only a few years later. He continued into the 1920s with such key American films as The Scarlet Letter (1926) and The Wind (1928).

So it’s saddening to report that A Lady to Love (1930) is a turkey. Edward G. Robinson, in full hambone overreach, plays an Italian-American grape farmer who seems to be flourishing despite the Volstead Act. Tony brings a down-at-heel waitress from the big city to be his wife, and she grows to love him, despite a little indiscretion involving Tony’s best friend. The sort of inert stage adaptation that gave talkies a bad name, A Lady to Love is solely for completists (of which Cinema Ritrovato boasts many). It was Sjöström’s last Hollywood picture. (DB)

The programs of 1907 films continued to yield treasures. Max Linder’s career got going that year, and he had not yet settled into the debonair, top-hatted persona that would within a few years become so familiar. In the simple and not terribly funny Débuts d’un patineur, he plays a novice ice-skater reduced to tears at by the film’s end, and in the more amusing Pitou bonne d’enfants Linder is a bumbling soldier who loses a baby confided to his care by his nursemaid sweetheart. The same program contained Louis Feuillade’s ever-popular Le Thé chez la concierge, where the guests start carousing so loudly that they drown out the bell rung by tenants trying to get into the house.

There were many early attempts to record synchronous sound, though all too often the accompanying discs have been lost even if the image track survives. The 1907 films contained a few such, but one, La Marseillaise, had its singer’s original voice, remarkably clear and perfectly synchronized. The result was an unusually poignant and vivid sense of a link to a hundred-year-old performance, an immediacy that went beyond what most silent films can convey, wonderful though they might be.

A familiar but welcome short was La course aux potirons (“The Pumpkin Chase”), one of the great entries in the very familiar genre of the day, the chase film. Special effects allow a wagon-load of pumpkins (looking like they were probably constructed from old tires) to bounce along city streets, up a chimney, and through windows, followed by the usual growing group of passersby. The inclusion of a donkey, duly hauled through the windows and up the chimney, makes the whole pursuit far funnier than in most such films.

Finally, the inclusion of a series of films about bomb-throwing anarchists, another common genre of the day, reminds us that the current international situation is not altogether a new one. (KT)

The DVD awards singled out efforts to making unusual cinema available in the DVD format. The top prize, Best DVD, was won by the Ernst Lubitsch collection, from Transitfilm and the Murnau Stiftung (available, with some variations, on Kino in the US). The committee commended it as “a model in the elegant packaging of rare materials in a form that is certain to attract new audiences.”

Anke Wilkening of the Murnau Stiftung accepts the award for best DVD.

Other awards: L’amore in città (Minerva, Italy), Best discovery; Seven Samurai (Criterion, US), Best Extras; the series on German cinema published by the Munich Film Archive, Best Series; and Akerman films of the 1970s (Carlotta, France), the French Naruse set (Wild Side) and the British Naruse set (Eureka), Best Box Sets.

Peter von Bagh commented that DVD producers are continuing the traditional work of film archives, and they often go beyond what archives can afford to tackle. Ironically, we sometimes find ourselves in the position of having excellent DVD versions of films that don’t exist in equally good prints. (DB)

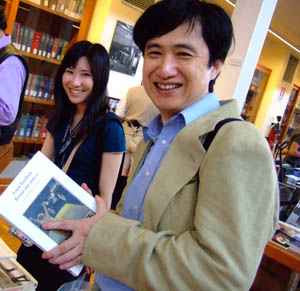

Finally, some snapshots. Glancing around the book room, you’ll see Sawako Ogawa and Hiroshi Komatsu pouncing on items.

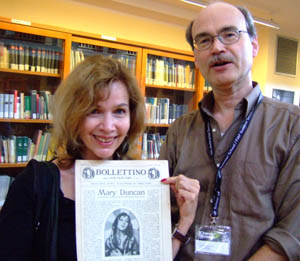

Not to be left behind, Janet Bergstrom and Richard Koszarski display Janet’s find.

Every year, Frank Kessler‘s birthday occurs during Ritrovato; this year was his fiftieth, and so Sabine Lenk made it a special treat.

At another meal, Danish film archivist Thomas Christensen, who really ought to know better, fends off the camera’s magical powers.

Same meal: shellfish and pasta sacrificed in a good cause.

Danish film historian Casper Tybjerg and Kristin sample gelato. Later I ate the one in the middle.

On the final evening, the film cans are wheeled out. Ci vediamo l’anno prossimo!

Another Bologna briefing

More notes and notions from Cinema Ritrovato, all from DB:

Could you make a movie today about a farm girl who becomes a concert pianist under the sway of a womanizing egomaniac? The slightly nutty I’ve Always Loved You (1946) displays Frank Borzage’s usual faith in the way lovers communicate by spiritual ESP, this time aided by Rachmaninoff. Borzage talked the low-end Republic studio into this expensive project, and the result, though marred by strained performances, looks great in a glowing restoration by UCLA. A teenage André Previn darts through, and for once someone playing the piano onscreen (in this case Catherine McCloud) looks skillful. (The playback renditions were those of Arthur Rubinstein, credited as “the world’s greatest pianist.”) The title is perfectly ambiguous, since it could refer to any character’s attitude toward almost any other.

Travel delays prevented Ben Gazzara from introducing the fine print of Anatomy of a Murder. Too bad. It would be fascinating to hear how he developed his disturbing portrayal of an accused killer under Preminger’s notoriously dictatorial direction. But Gazzara did participate in an interview with Peter von Bagh that led into a screening of a beautiful restoration of Jack Garfein’s The Strange One (aka End as a Man).

Gazzara talked of coming out of the Actors Studio after the success of Marlon Brando, a tremendous influence on Gazzara’s generation. He recalled that he was in the same Studio class as James Dean, Steve McQueen, and Paul Newman. What was the Method? “It’s a word I never use. I don’t know what it means. . . It gave you things to fall back on” if you couldn’t come to grips with the script material.

Gazzara talked of coming out of the Actors Studio after the success of Marlon Brando, a tremendous influence on Gazzara’s generation. He recalled that he was in the same Studio class as James Dean, Steve McQueen, and Paul Newman. What was the Method? “It’s a word I never use. I don’t know what it means. . . It gave you things to fall back on” if you couldn’t come to grips with the script material.

He said that he loved Hollywood acting of the studio era: Gable, Grant, Tracy, and Stewart remain fresh and modern. When he saw Meet John Doe, he realized that Gary Cooper used his own version of the Method: “He did very little, but he did everything.”

Gazzara said that seeing Faces (1968) drew him to Cassavetes. “I was mesmerized. I was so jealous. I thought, I’ve gotta work with this man.” A year later he made Husbands. Cassavetes was very supportive, always “waiting for surprises.” He was laughing in enjoyment behind the camera, encouraging his players. “All you did was safe, and you could do no wrong.”

The Strange One, set in a Southern military academy, was Gazzara’s first film. He was offered the part of the cadet who eventually leads a revolt against the Machiavellian cadet Jocko De Paris. But Gazzara said that he wanted to play DeParis because “he got all the laughs.” George Peppard wound up with the good guy role. Though the film seems to me confused on several dimensions, Gazzara revels in the showy part of a soft-spoken, eminently reasonable sociopath. As in Anatomy of a Murder, he makes gently menacing use of a cigarette holder.

In the early 1930s, Japanese companies explored the possibility of exporting their films to Europe and the US. One result of these initiatives was Nippon: Liebe und Leidenschaft in Japan, a 1932 German compilation created by Carl Koch. It originally consisted of three films from the Shochiku studio, condensed and supplied with German intertitles. The original films were silent, so, oddly enough, synced Japanese dialogue was added.

In the version screened here, only two episodes were presented. What beauties they were! Since many of the 1920s and 1930s Japanese films that survive look quite weatherbeaten, it was wonderful to see, in the print from the Cinémathèque Suisse, how gorgeous quite ordinary movies from this era could be.

The first story, Kaito samimaro (orig. 1928), deals with a young samurai rescuing his beloved from the clutches of a corrupt priest. Brisk and beautifully shot, it came to the sort of frothing swordplay climax typical of the period—rapid cutting, dynamic tracking, and slashing assaults aimed at the camera. Kagaribi (1928), about a young vassal betrayed by his corrupt lord, likewise ended with a protracted action scene capped by a jolting climax. A prolonged tracking shot follows the young man’s former lover as she backs away from him, but then we cut to a full shot. With a single stroke he kills her, jaggedly ripping a paper door in his follow-through. Both stand motionless for a moment before she falls. A conventional finish, but no less eye-smiting for that. For more on the power of this action-cinema tradition, see an earlier entry on this site.

There are no fewer than ten flashbacks in the 1950 Swedish film Flicka och Hyacinter (Girl with the Hyacinths, above). Peter von Bagh’s Bologna programming has often highlighted Nordic work that’s little known outside the region, such as this engrossing post-Kane exercise in probing a dead person’s life. Teasingly directed by Hasse Ekman, the interlocking flashbacks would be savored by today’s puzzle-film aficionados, and the movie’s equivalent of Rosebud is genuinely surprising. The twist would never have been permitted in Hollywood of that era.

Kristin and I hope to post one more entry, probably soon after Ritrovato’s final session on Saturday. Lots more to report–Lubitsch, Borzage, Chaplin (of course), etc. For now, a glimpse of the official names of the Cineteca’s two screening rooms…