Archive for the 'Directors: Chaplin' Category

The ten best films of . . . 1918

Kristin here–

We ended 2007 with a salute to the 90th anniversary of the solidification of the classical Hollywood filmmaking system. 1917 was not only the year when all the guidelines—continuity editing, three-point lighting, and unified story structure—gelled in American cinema. It was also one of those years (like 1913, 1927, and 1939) when a burst of creativity took place internationally. For those years, it’s hard to keep one’s greats list to ten.

Enough of you enjoyed that entry that we thought we would come up with another list to end 2008. For some reason, 1918 doesn’t yield the plethora of great films that obviously should go on such a list. Maybe it’s the sheer accident of preservation. After a string of masterpieces from Douglas Fairbanks in 1917, there seems to be a dearth of his films extant from the following year. Some filmmakers, like Cecil B. De Mille, simply released fewer films in 1918. And of course, some masterpieces may still lie gathering dust on archive shelves, waiting to be discovered.

Still, great films were made that year, some familiar—some that should be better known. Some are available on DVD, and some are excellent candidates for release by some of the enterprising companies like Kino International, Image Entertainment, and Flicker Alley.

1. The list isn’t in rank order, but for me the outstanding film of 1918 is Berg-Ejvind och hans hustru, better known to most as The Outlaw and His Wife, by Victor Sjöström. This tale of an enduring love between a man  hunted by the police and a rich landowner who falls in love with him, and, as one title says, “Hearth and home and every man’s respect—she gave it all up for his sake.” The result is one of the cinema’s great romances as the pair flees to the mountains and spend the rest of their lives amidst the natural landscapes that create spectacular backdrops for the action.

hunted by the police and a rich landowner who falls in love with him, and, as one title says, “Hearth and home and every man’s respect—she gave it all up for his sake.” The result is one of the cinema’s great romances as the pair flees to the mountains and spend the rest of their lives amidst the natural landscapes that create spectacular backdrops for the action.

This year Kino also brought out a disc with the dynamite double bill of two tragedies Ingeborg Holm (1913) and Terje Vigen (1916). David and I have both written about the staging in Ingeborg Holm, and David has had much to say on tableau staging in 1910s cinema. Watch these three films, and you will understand why we consider Sjöström perhaps the great director of the decade. It’s a shame that more of his films are not available yet in the U.S. Buy copies of these, and maybe Kino will bring more of them out.

2. Another master of this era, Louis Feuillade, made a sequel to his Judex (1916): La Nouvelle Mission de Judex. David discusses both in the second chapter of his Figures Traced in Light. Although Judex is available on DVD, so far the second serial is not.

3. I suspect that Hearts of the World is one of those D. W. Griffith features that a lot of film enthusiasts have heard of but not seen. Remarkably, it’s not available on DVD. (Keep your old laserdisc if you’ve got one!) I have to admit, it’s not one of my favorite Griffiths, though it does have a charming performance by Dorothy Gish and contains scenes that were actually shot near the front lines in France.

4. Ernst Lubitsch was making the transition from shorts to features in 1917 and 1918. While Carmen is historically important for his development toward his mature style, most audiences these days would probably find Ich möchte kein Mann sein (“I don’t want to be a man”) more entertaining. It’s a comedy about an independent young lady who escapes her strict governess and guardian by going out on the town disguised as a man—in the process joining her guardian without his recognizing her (see the frame at the bottom). Its star, Ossi Oswalda, was an outgoing blonde dynamo, quite different from Pola Negri, whom Lubitsch turned to for his later historical epics.

Kino has made several of Lubitsch’s films from the late 1910s and early 1920s available. Ich möchte kein Mann sein can be bought on a single disc with Die Austerinprinzessin (“The Oyster Princess,” 1919), another Oswalda comedy. I’d recommend getting it as part of the larger “Lubitsch in Berlin” set, which also includes the hilariously imaginative Die Puppe (“The Doll,” 1919), the Expressionist satire Die Bergkatze (“The Wildcat,” with Negri in her one comic role for Lubitsch, 1921), an Arabian-nights epic Sumurun (1920), and the historical epic Anna Boleyn (1921), as well as a documentary on Lubitsch.

5. In 1918 Cecil B. De Mille made a film that would change his career’s trajectory: Old Wives for New. At the  time, this romantic drama that seemed risqué in its casual depiction of adultery, golddiggers, and especially divorce as creating a happy outcome. Up to that point De Mille had been working in a whole range of genres, creating imaginative films that helped define the classical style. The success of Old Wives for New led him to specialize in spicy romances known for their haute couture costumes. The film is available on a disc from Image that includes De Mille’s other major film of 1918, The Whispering Chorus.

time, this romantic drama that seemed risqué in its casual depiction of adultery, golddiggers, and especially divorce as creating a happy outcome. Up to that point De Mille had been working in a whole range of genres, creating imaginative films that helped define the classical style. The success of Old Wives for New led him to specialize in spicy romances known for their haute couture costumes. The film is available on a disc from Image that includes De Mille’s other major film of 1918, The Whispering Chorus.

6. Hell Bent, by John Ford, was long thought to be among his many lost westerns from the early years of his career. It was rediscovered in the Czechoslovakian archive and shown years ago in Pordenone at the Il Giornate del Cinema Muto festival. I must confess that I don’t remember it very well, apart from one spectacular tilt downwards as a stagecoach (?) races down a winding mountain road. Not as good as Straight Shooting, and Hell Bent survives in rocky shape (perhaps too much so for DVD release), but Ford films of this era are so rare that I’ve listed this one.

7. Like Lubitsch, in the late 1910s Charlie Chaplin was making a gradual transition from shorts to features. In 1916 and 1917 he released a remarkable string of Mutual two-reelers, from The Rink (December 1916) to The Adventurer (October 1917). In 1918, with A Dog’s Life and Shoulder Arms, he increased the films’ length to three reels, or roughly 45 minutes, and started releasing through First National. He also cut back on the number of titles released each year. Apart from a brief promotional film for war bonds, A Dog’s Life and Shoulder Arms were his only 1918 releases. Which is better? I suppose most people would say Shoulder Arms. To me it’s a toss-up.

8. David and I started attending Il Giornate del Cinema Muto in 1986, when the festival was launching its great series of national retrospectives. In quick succession, these retrospectives revealed three hitherto virtually unknown but major auteurs of the 1910s: the Swede, Georg af Klercker, in 1986; the Russian, Evgeni Bauer, in 1989; and the German Franz Hofer, in 1990. Bauer’s career ended with his death in 1917. Hofer remained active until the early 1930s. The Giornate’s German program contained only six of his films, however, and those from the 1913-1915 period. I suspect that means the later teens titles are lost.

In contrast, nearly all of af Klercker’s films survive, mostly in the original negatives. The prints shown at Pordenone were stunning. The director had a great eye for settings, using beaded curtains, mirrors, and other elements to considerable effect. He made three films in 1918: Fyrvaktarens dotter, Nobelpristagaren,Nattliga toner, the first two of which were shown in the 1986 retrospective.

Unfortunately since then the films have not been made widely available, either in prints or on DVD. Having not seen the two titles just mentioned since 1986, I can’t say that I remember them well enough to judge between them. So I’ll just leave all three films here, along with the advice to seize any chance you may get to see those or af Klercker’s other films.

(Given how little known af Klercker’s work is outside Sweden, I should point out a major English-language piece on the director’s style, Astrid Söderbergh Widding’s “Towards Classical Narration? Georg af Klercker in Context,” in editors John Fullerton and Jan Olsson’s Nordic Explorations: Film Before 1930 [Sydney: John Libbey, 1999].)

9. Stella Maris, directed by Marshall Neilan, was the first of five features Mary Pickford starred in in 1918. Its reputation lies mainly in the fact that Pickford played a double role, the bed-bound but lovely title character, and an ugly, slightly deformed orphan. In its outline, the story sounds abstract and overly symmetrical. Stella Maris’s relatives shut her off from all ugliness in the world, keeping her in happy innocence well into her teens. Unity, the orphan, has known nothing but deprivation. As Stella comes to glimpse the grim side of life, Unity is adopted and has glimpses of the beauties enjoyed by the rich. Both become miserable as a result.

The overall implication is pretty grim. Stella’s world is initially wonderful only because everyone lies to her. She becomes embittered when she finally discovers this. At the heart of the tale is the deception that life is beautiful. Unity, who has not been deceived, knows better from the start. Even one brief reference to the war, as a troupe of soldiers passes by the estate where Stella lives, makes it seem tragic—this in a film that came out about two months after the U.S. had entered World War I.

The balance between the two characters is made less artificial than it might sound by Pickford’s extraordinary performance—not so much as Stella, who is a rather passive version of the typical Pickford persona, but as Unity. The waif’s frequent disappointments and outright suffering create a strong effect that shadows even the quasi-happy ending. It’s a beautifully made film as well, with the use of glamorous backlight (as in the image at the top of this entry). Stella Maris is available on DVD from Image.

10. I have been hard put to find a feature to round out the list, so I’m substituting a group of shorts. They’re not masterpieces by any means, but each displays the talents of a great silent comic well on the way toward his most fruitful period.

There’s no single great film to mark Harold Lloyd’s transition, but during 1918 he was developing his “glasses” character. He had had a modest success with his “Lonesome Luke” series from 1915 to 1917, where he essentially created a variant of Chaplin. In September, 1917, Lloyd first wore his famous black, lens-less glasses in Over the Fence. His early one-reelers wearing those glasses were still sheer slapstick, with little of the characterization that he would later develop to go with his new look. Arguably it was 1919 or even 1920 before he had fully nailed that persona. Still, during 1918 one can see him groping toward the formula.

Kino’s “The Harold Lloyd Collection” volumes contain four films from that year, all co-starring Lloyd’s  regular co-stars, Snub Pollard and Bebe Daniels. The Non Stop Kid (the title on the film; filmographies mistakenly give it as The Non-Stop Kid; May 21), Two-Gun Gussie (May 19), The City Slicker (June 2, all three on volume 2), and Are Crooks Dishonest? (June 23, on volume 1). The development clearly came in fits and starts. Two-Gun Gussie and Are Crooks Dishonest? are both slapstick affairs involving tricks and mistaken identify. The Non Stop Kid, though, has Lloyd in a more familiar situation, using his wits to foil a crowd of suitors and win the heroine’s hand. The City Slicker has a similar feel to it, though unfortunately the end is missing. The Non Stop Kid also has Lloyd donning a disguise in the form of a false moustache that somewhat resembles the one he had worn as Luke. This scene has a startling effect, blending the glasses character and the Luke character.

regular co-stars, Snub Pollard and Bebe Daniels. The Non Stop Kid (the title on the film; filmographies mistakenly give it as The Non-Stop Kid; May 21), Two-Gun Gussie (May 19), The City Slicker (June 2, all three on volume 2), and Are Crooks Dishonest? (June 23, on volume 1). The development clearly came in fits and starts. Two-Gun Gussie and Are Crooks Dishonest? are both slapstick affairs involving tricks and mistaken identify. The Non Stop Kid, though, has Lloyd in a more familiar situation, using his wits to foil a crowd of suitors and win the heroine’s hand. The City Slicker has a similar feel to it, though unfortunately the end is missing. The Non Stop Kid also has Lloyd donning a disguise in the form of a false moustache that somewhat resembles the one he had worn as Luke. This scene has a startling effect, blending the glasses character and the Luke character.

1917 and 1918 formed the high point of the string of comic shorts directed by Fatty Arbuckle, in which he also co-starred with Buster Keaton and Al St. John. When Keaton went solo, he proved to be a far better director than Arbuckle. Arbuckle tended to simply face his camera perpendicularly toward the back of the set for every shot, just cutting to whatever scale of framing would best display a gag. Here it’s the perfectly timed and executed gags that dazzle, and the films are often hilarious. In 1918, the team made The Bell Boy, Moonshine, Out West, Good Night Nurse, and The Cook. The latter shows off Arbuckle and Keaton’s dexterity at juggling props and Fatty’s surprising grace, as when he improvises a Salome dance with a head of lettuce standing in for that of John the Baptist!

The 13 surviving Arbuckle-Keaton films (some with missing bits) are available on Eureka’s definitive boxed set, “Buster Keaton: The Complete Short Films.” (That’s Region 2 format only, and available from Amazon UK.) Image’s “The Best Arbuckle Keaton Collection” has 12 films, missing only the more recently rediscovered The Cook. Image brought out The Cook on a disc with Arbuckle’s A Reckless Romeo (1917, sans Keaton). Kino’s two separately available volumes of “Arbuckle & Keaton” (here and here) contain 10 shorts total, again missing The Cook.

Apart from all these films, it’s worth noting that in the world of animation, 1918 saw the release of Winsor McCay’s fourth cartoon, The Sinking of the Lusitania, and Dave Fleischer’s first, Out of the Inkwell, which launched the enduring series.

Next year, 1919. Happy 2009 to all our readers!

Cinema bolognese

Cinema Ritrovato, a festival of rediscovered and restored films, is now in its twenty-first year. We visited its two previous installments, and we found it one of the most hugely enjoyable festivals on the calendar. Where else can you see films from 1907, Richard Fleischer’s Violent Saturday (1955), and a tribute to Ben Gazzara in a single week? Then there are the nightly screenings on the Piazza Maggiore, which attract hundreds of locals. The city plays host magnificently, with plenty of fine restaurants and perpetually cheerful people.

Mounting hundreds of screenings and panels is an enormous effort, but Gianluca Farinelli, Guy Borlée, Peter von Bagh, and all their colleagues have made it look easy. (The word sprezzatura comes to mind.) Here are our impressions from the first half of the event.

The home base is the Cineteca di Bologna, the local film archive. It’s located in a wide, quiet courtyard. It houses a large library and meeting rooms, along with two cinemas. During the festival, the Lumiere 1 auditorium specializes in silent screenings with piano accompaniment, while Lumiere 2 presents sound films. Widescreen titles and big events are reserved for the Arlecchino, a big, comfortable commercial theatre built in the era of roadshows and CinemaScope.

Organizing such a mixed program is more difficult in certain ways than presenting an event involving contemporary films, which are moving through the festival circuit already. Ritrovato must find good prints of titles that fit the year’s themes and also coordinate the ongoing efforts of archives that are restoring films.

A good example is a remarkable project overseen by Alexander Horwath of the Austrian Film Museum. One of the most famous lost films in US history is Josef von Sternberg’s 1929 movie The Case of Lena Smith. In 2003, Japanese scholar Komatsu Hiroshi found a fragment, in very good condition, in China. On the basis of this, Horwath and his collaborators created a wonderful book that reconstructs the film. It includes a detailed shot breakdown (based on one published in Japan during the film’s release), along with gorgeous stills, script extracts, summaries of critical reception in various countries, and essays about the film’s place in history.

The fragment, previously screened at the Giornate del Cinema Muto last fall, was tantalizing. Lena and her friend Pepi are in the Prater, Vienna’s dazzling amusement park, and they are eyed by two young officers. The women watch some of the sideshow entertainments before darting away, the officers in pursuit. Several of the shots evoke the heady atmosphere of the park, with prismatic, superimposed images of the sideshow attractions and—typical von Sternberg—a spinning ride providing pulsating visions of the crowd.

In his panel presentation, Horwath stressed that the book couldn’t have been done without the cooperation of researchers around the world. The multilingual volume is to be made available in the UK and the US in 2008. It is a splendid example of what archives and scholars can accomplish working together, with festivals like Cinema Ritrovato providing a forum for rediscoveries. The book is available already at the archive’s website and will be distributed later this year by Wallflower in the UK and Columbia University Press in North America. (DB)

In his panel presentation, Horwath stressed that the book couldn’t have been done without the cooperation of researchers around the world. The multilingual volume is to be made available in the UK and the US in 2008. It is a splendid example of what archives and scholars can accomplish working together, with festivals like Cinema Ritrovato providing a forum for rediscoveries. The book is available already at the archive’s website and will be distributed later this year by Wallflower in the UK and Columbia University Press in North America. (DB)

One of the threads of this year’s festival is the early US career of Michael Curtiz. The Strange Love of Molly Louvain (1932) is an energetic Warners crook melodrama. Starring Ann Dvorak and the ever-annoying Lee Tracy, the film displays Curtiz’s characteristically staccato direction. The scenes with hard-bitten reporters use overlapping dialogue in a manner that prefigures His Girl Friday. Rarer was The Third Degree (1926), an early instance of Europe’s “International Style” infiltrating Hollywood. For his first Warners project, Curtiz fills an implausible mother-daughter melodrama with cloudy superimpositions, canted angles, florid tracking shots, oddball angles, extreme close-ups, and frantic montages played with prismatic lenses. Richard Koszarski gave an amusing and helpful introduction. (DB)

One attractive constant of the Ritrovato is a series of short films from 100 years ago. Thus when we first attended in 2005, there were groups of shorts from 1905. As we progress through the early years of the current century, we go in parallel through the early years of the previous one. Each day one or two small groups of 1907 films have been shown, grouped by country or genre. These included some familiar items, like the poignant Le Bagne des gosses (“Children’s Prison,” Pathé) and the amusing British chase film, That Fatal Sneeze (directed by Lewis Fitzhamon). I have run across references to early Westerns made in Europe but had not seen any from this early period. Les Apaches du Far-West (produced by Pathé) is as unauthentic as one might predict, with the cowboys riding on English-style saddles and the shoot-outs with the Apaches taking place in bucolic fields and woods that are clearly in France, not the West. (KT)

A major new initiative for international film preservation was announced in May at the Cannes Film Festival. The World Cinema Foundation was founded by Martin Scorsese, and its advisory board contains such major filmmakers as Abbas Kiarostami, Elia Suleiman, Walter Salles, and Wim Wenders. The goal is to restore films made in nations that lack the archival facilities to do so locally.

The Moroccan Transes (El Hal, 1981), directed by Ahmed El Maanouni, is the new foundation’s first restoration, and it was introduced by the director and by its producer, Izza Genini. The titles crediting Giorgio Armani, Cartier, and Qatar Airlines as sponsors raised some surprised laughter in the audience, but if Scorsese and his colleagues can draw funding from such sources into film restoration, all the better. Transes is partly a concert film and partly a history of a band that became popular in the 1970s by expressing young people’s frustrations and rebelliousness. The big concert that begins and ends the film is exhilarating in its depiction of the crowd’s enthusiasm—but chilling as well as soldiers patrol the audience and occasionally suppress the more demonstrative spectators. (KT)

Another major theme is the ever-popular star Asta Nielsen. Again, items familiar from other retrospectives are mixed with new discoveries. Karola Gramann has curated the series and plans to restore other Nielsen films, either new discoveries or better prints of familiar films. Zapatas Bande (1913-14), for example, existed before, but now a color print has been made based on tinting notations on an existing black-and-white copy. It’s a slight item, a casual tale of filmmakers getting into trouble while shooting an adventure movie, but it allows Nielsen to get away from her usual melodramas and display her range as a comic actor. (KT)

Another major theme is the ever-popular star Asta Nielsen. Again, items familiar from other retrospectives are mixed with new discoveries. Karola Gramann has curated the series and plans to restore other Nielsen films, either new discoveries or better prints of familiar films. Zapatas Bande (1913-14), for example, existed before, but now a color print has been made based on tinting notations on an existing black-and-white copy. It’s a slight item, a casual tale of filmmakers getting into trouble while shooting an adventure movie, but it allows Nielsen to get away from her usual melodramas and display her range as a comic actor. (KT)

Our first visit to Italy for a film festival was in 1986, when Le Gionate del Cinema Muto, in Pordenone, presented a vast retrospective of Scandinavian cinema from the pre-1919 era. One of the major revelations was that alongside Mauritz Stiller and Victor Sjöström, there was a third great Swedish director during the silent era, Georg af Klerker. The event also brought home to the audience one of the great tragedies of cinema history, the loss of many of Stiller’s and Sjöström’s films in an archive fire in the 1940s.

Every now and then, another film by one of these masters surfaces. This year the Ritrovato festival showed Madame de Thèbes, a 1915 Stiller film. As too often happens, the surviving copy, a French release print discovered by Lobster Films, was incomplete. The Svenska Filminstitutet has filled it out by inserting still shots created from copyright frames deposited at the Library of Congress and by replicating the original Swedish intertitles and letters. The result, full of sumptuous decor and extravagant plot twists, gives as good an approximation of the original as is now possible. It’s one more indication that the 1910s Swedish cinema was one of the glories of the silent era. (KT)

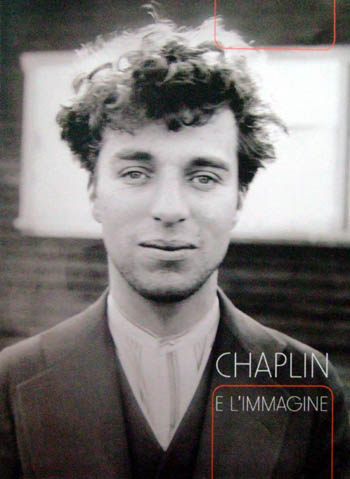

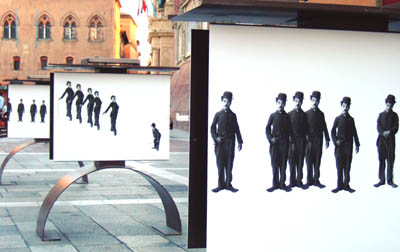

The festival has a close relation with the Charlie Chaplin estate; this is the place to come for the latest in Chaplin restorations and scholarship. Every year the festival mounts a tribute, including a superbly designed book on some aspect of Chaplin’s career. This year’s volume is a collection of rarely seen pictures, and its cover carries one of the most melancholy and haunting portraits of Charlie I’ve ever seen (up top).

The first big event of the festival was a screening in the city’s Teatro Communale, an overpowering opera house. It was a fitting venue for The Idle Class (1921) and The Kid (1921), accompanied by orchestra. The prints were pristine, shown in a nearly square ratio. The version of The Kid was based on Chaplin’s 1971 rerelease, since that represents his final thoughts, but the Bologna gang generously tacked on the material that Chaplin chopped out—all scenes with Edna Purviance, playing the unwed mother who abandons her baby. These scenes include her uneasy meeting her old lover years after she’s achieved success. The plot turn and the regretful tone seemed to me to look forward to A Woman of Paris. This version, along with the deleted scenes, is available on the MK2 DVD release.

The first big event of the festival was a screening in the city’s Teatro Communale, an overpowering opera house. It was a fitting venue for The Idle Class (1921) and The Kid (1921), accompanied by orchestra. The prints were pristine, shown in a nearly square ratio. The version of The Kid was based on Chaplin’s 1971 rerelease, since that represents his final thoughts, but the Bologna gang generously tacked on the material that Chaplin chopped out—all scenes with Edna Purviance, playing the unwed mother who abandons her baby. These scenes include her uneasy meeting her old lover years after she’s achieved success. The plot turn and the regretful tone seemed to me to look forward to A Woman of Paris. This version, along with the deleted scenes, is available on the MK2 DVD release.

The score was by Timothy Brock, who also conducted. On the following day Brock gave an enlightening seminar on how he based his scores on original themes that Chaplin came up with. Chaplin was in the habit of working and reworking tunes at the piano, and many of his efforts were recorded. The recordings came to light three years ago, and Brock was able to integrate the tunes into his scores—sometimes linking five or six in a single passage. (DB)

The score was by Timothy Brock, who also conducted. On the following day Brock gave an enlightening seminar on how he based his scores on original themes that Chaplin came up with. Chaplin was in the habit of working and reworking tunes at the piano, and many of his efforts were recorded. The recordings came to light three years ago, and Brock was able to integrate the tunes into his scores—sometimes linking five or six in a single passage. (DB)

A cloud was cast over our visit by the news of the death of Edward Yang (Yang Dechang). We admired his films and discussed them in Film History: An Introduction and my Figures Traced in Light. Edward was a likeable, tough-minded fellow. His films explored the effects of urbanization and politics on everyday life in Taiwan. He made his breakthrough to a broad international audience with Yi Yi (2000), but his other films, particularly Taipei Story (1985), The Terrorizers (1986), and A Brighter Summer Day (1991) are to me even more important. It’s a great loss that these aren’t easily available on DVD. When I get back to Madison and have access to pictures from my encounter with Edward in Kyoto in 1997, I hope to write a more adequate tribute. (DB)

Funny framings

DB asks: Can a film shot be amusing in itself?

Of course a shot can show us a gag that’s funny. If Jerry Lewis or Adam Sandler is going to fall off a ladder into a Dumpster, we want to see everything clearly. Here the framing can be modestly functional. But can the very choice of lens, angle, scale, or composition play a stronger role? Can camerawork itself provide the gag?

Barry Sonnenfeld, cinematographer for the Coens and now a prominent director, thinks so. He’s remarked that an extreme wide-angle lens is inherently funny. In the commentary for the DVD of RV, he explains, “You just put a big 21mm lens really close to [Will Arnett’s] face and you get comedy without him having to do anything.” I don’t have an RV frame handy, but here’s an example from Big Trouble, with both the wide lens and the low-angle creating the sort of grotesque disproportions that Sonnenfeld finds funny.

Sonnenfeld got this idea, he claims, by working on the Coens’ early films, which used wide-angle shots for cartoonish exaggeration. In Raising Arizona, the angle and lens length make the wandering baby loom; we’re not used to seeing an infant rampant.

But the Coens had a broader approach to funny framings than Sonnenfeld acknowledges. For instance, they created humor by means of geometrical tableaus. In H. I.’s parole hearing in Raising Arizona, an absurd solemnity is set up by the symmetrical layout of actors. At the apex of the triangle, a portrait of Senator Barry Goldwater blesses the occasion.

Even more memorable is the forward tracking shot down the bar top in Blood Simple. The camera, encountering a drunk sprawled in its path, simply crawls over him.

The silent comedians knew how to use camera position to build up their gags. Long ago Rudolf Arnheim praised the opening scene of Chaplin’s The Immigrant. As a ship rocks treacherously, we see Charlie from the rear heaving and kicking on the railing. As Arnheim puts it, “Everyone thinks the poor devil is paying his toll to the sea.” (1)

But then Charlie turns toward the camera to reveal he’s been struggling to reel in a fish.

Here the framing creates the gag by what it doesn’t show. “The element of surprise,” Arnheim notes, “exists only when the scene is watched from one particular position.” The camera setup also makes an expressive analogy; we probably never noticed the similarity between vomiting and wrestling a fish.

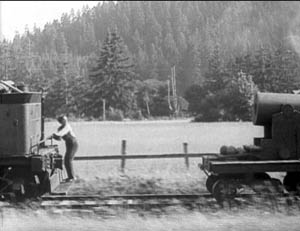

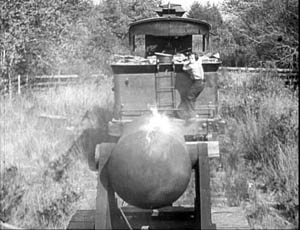

One of my favorite comic framings occurs in The General. Buster’s train is hurtling along, and a cannon on one car is suddenly trained on him. The first shot gives us the situation with maximum clarity, in a profiled shot. But then Keaton cuts to another angle, showing the cannon in the foreground and Buster trying to escape it.

Nothing much has changed in the scene’s action, just the camera setup. But now we get to watch the cannon draw a bead on Buster. Audiences invariably laugh at this shooting-gallery image.

Jacques Tati is in many ways the modern heir of Keaton, and humor in his sequences often stems simply from a juxtaposition of elements in a single frame. An older man ogling a pretty woman on the beach is funny in a standard way, but in M. Hulot’s Holiday, we get more.

No words are spoken, but Tati’s staging and framing juxtapose the very different bodies in telling ways. We’re invited to note the difference between age and youth, paunchiness and health, passing yearning and its likelihood of fulfillment.

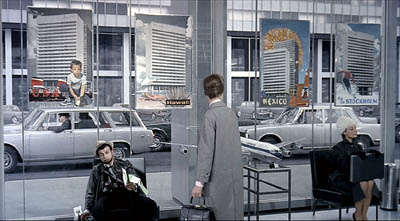

Play Time, Tati’s masterpiece and one of the greatest films ever made, offers an abundance of subtly comic framings. The shot below promotes the film’s theme that modern architecture has homogenized the world. The posters present the same building in different locales, with only stereotyped add-ons to distinguish the US, Hawaii, Mexico, and Stockholm. As one of the ladies on Barbara’s tour says, “I feel at home everywhere I go.”

Again, though, a juxtaposition adds to the humor. Throughout Play Time, Tati suggests the disparity between the joy of travel as promoted by our culture and the stress of hustling from place to place. The promise of the posters is undercut by the dazed traveler who’s flopped underneath them, clutching maps and flightplans. And he in turn contrasts with the no-nonsense businesswoman on the far right.

Tati can create comedy by the exact placement of the camera; a foot to the left or right and the gag would vanish. In the image at the start of this entry, the waiter is pouring champagne, but he seems to be watering the ladies’ flowery hats, which mask their champagne glasses. The same sort of exactitude of placement occurs in a shot we use as an illustration in Film Art (p. 195). M. Hulot is leaving an office building when it’s closing. As a guard locks down a doorway, his cap falls off and Hulot is startled: the guard seems to have grown horns.

Can we find funny framings in current films? Yes! I was prompted to write this blog while rewatching Shaun of the Dead. Zombies have overrun London, and two groups of human survivors meet. Shaun is leading one, Yvonne is leading the other. Instead of being presented as a mingling of the two groups, the scene plays out along two lines of people. Have a look.

The gag’s premise is that each survivor has a counterpart in the other line. There are two posers in brown leather jackets, two can-do girls, two matrons, and two distracted videogame geeks. I wonder how many first-time viewers catch this? (Kristin did, I didn’t.)

These mirror-image depth shots set up the real gag, which pays off in another clever composition. When the two groups set off on separate paths, each member passes and smiles awkwardly at her/his lookalike, while the framing underscores their likenesses.

As they walk through the frames, the similarities increase.

The framing makes a clever point about conformity and social stereotypes. Ending the procession with the two gamers, oblivious to the danger and to one another, tops the topper, as gag writers would say.

Tati would have loved these shots.

Of course I’ve simplified things for the sake of making my point. It’s not that the camera is somehow capturing a free-standing event by selecting the most amusing view. In all these examples, the staging is calculated to match the camera position. Staging, like camerawork and other film techniques, creates filmic narration. I’m only suggesting that in these scenes, the staging wouldn’t work on its own to create humor, nor would a simply functional framing. Choices of lens, camera position, and the like seem to be critical in making the gags work.

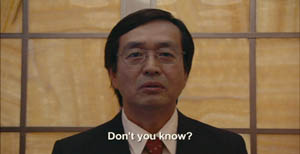

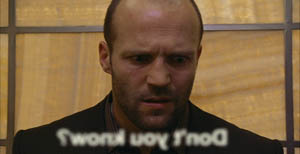

Finally, a borderline case that intrigues me. In last year’s Crank, our hero is in overdrive thanks to a constant intake of drugs. Stepping into an elevator, he faces a man who starts speaking Japanese. Naturally, his line is subtitled.

But then we get this:

The idea of the head-on reverse angle is carried to comic extremes by reversing the subtitle as well (and blurring it to reaffirm the hero’s muzzy mental state).

I think that aspiring filmmakers can learn a lot from this tradition. Our films need more pictorial creativity, which often doesn’t require fancy CGI. Stylistic handling can add fresh layers to a basic story situation, and astute filmmakers can be alert to the possibilities of comic compositions and funny framings.

(1) Rudolf Arnheim, Film as Art (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1957), p. 36.

PS 4 May: Owen Williams writes to point out that the gag in Crank depends not just on a reverse framing but a play on the idea of lens focus. “The subtitle is fuzzy because it’s supposed to exist in real space (at least in this character’s head), with the letters hanging in mid-air in front of the Japanese man. Therefore in the reverse angle they appear out of focus (fuzzy) because they are closer to the camera. It’s a great gag.” Thanks, Owen.

PPS 8 May: I’ve gotten a lot of correspondence about this blog entry. Here are some nifty supplements:

Kent Jones was reminded of the shot in High Anxiety in which the camera moves to a picture window, with people dining behind it, and then crashes through the glass.

Sam Adams recalled a shot in Killer of Sheep that had something of the same effect, showing men trying to load a car engine onto the bed of a pickup truck. But the context isn’t itself comic. Sam reflects: “Based on the examples you choose, it seems that ‘comic framing’ invariably involves a level of self-consciousness, a feeling that the audience is being deliberately toyed with by the figure behind the camera. We get a sense that the scene has been staged for our amusement, rather than feeling that we must identify emotionally with whatever the characters are going through (which even in comedies is often quite sad).”

Stew Fyfe found a host of in-jokes in the Shaun of the Dead shots:

“Viewers of British television might notice an extra parallel between the shots. The actors playing each of the group leaders, Simon Pegg (Shaun) and Jessica Stevenson (Yvonne), were the leads in the sitcom Spaced (also directed by Edgar Wright, the TV predecessor to Shaun). Also split between the two groups are Lucy Davis (Shaun’s Group, hat) and Tim Freeman (Yvonne’s group, second in line), from original The Office and Dylan Moran (Shaun’s group, glasses) and Tamsin Greig (Yvonne’s group, hat), the leads of the sitcom Black Book. Yvonne’s mum (second matron) is played by Julie Deakin, who played the drunk and desperately lonely/horny landlady in Spaced.”

Thanks also to Bryan Wolf for a note on the same subject.

Finally, this from Jeremy Butler:

“I like your example from The General, but my favorite example of comic framing from Keaton’s work (and one I use in class to illustrate how he was more “cinematic” than Chaplin) is in Sherlock, Jr. Buster runs along the top of a freight train, and is then flushed to the tracks by a spout from a water tank. What makes it funny, I’d suggest, is the choice to frame it from the side, at a right angle to the tracks (much like the first General frame in your example). It minimizes the size of Buster’s body and contrasts him with the size of the train cars. Plus, it emphasizes the movements in opposite directions of his body and the train.

All these elements make it visually funny in a way that would not be apparent if it were filmed from an oblique angle or from behind the train.

But then, maybe I just like to show it because it’s the scene in which Buster literally broke his neck–which he didn’t realize until decades later when being x-rayed for something completely different!”

Thanks to everyone who wrote in with comments and who linked to this entry.