Archive for the 'Directors: Coens' Category

Let’s play God, imperfectly: BLOOD SIMPLE on the Criterion Channel

Blood Simple (1984).

DB here:

Over the last couple of years I’ve been writing a book on common strategies of popular storytelling in film and other media. I go on to trace how those strategies get worked out in detective stories and thrillers. If you follow this blog, you know that these genres are ones I enjoy and like studying.

So I was happy to offer as one installment of our Criterion Channel series, Observations on Film Art, a short analysis of storytelling strategies in Blood Simple. In it I suggest that although the film has the trappings of a neo-noir–the somewhat downmarket characters, the seedy milieu, the chiaroscuro lighting–in its narrative techniques it’s closer to a Hitchcock thriller. That’s because its manipulation of point of view, one of the resources of popular storytelling, is close to the “partial and misleading omniscience” of the thriller genre and Hitchcock’s narration in particular.

Put it another way. We aren’t restricted to what only one character knows, as in a detective story like The Big Sleep (1946). Instead, Blood Simple steers us selectively from one character to another. So we always know more than any one of them does. That creative choice increases suspense–knowing the dangers that lurk ahead–but it also summons up an ironic detachment from them, as we watch them make their foolish mistakes. In a word, if you know the film: fish. Here’s another: lighter.

This shifting viewpoint doesn’t give us absolute knowledge, though. There is still some information that slips through the cracks. So we can enjoy superior knowledge in long stretches, while still getting some sudden surprises, or even shocks. (Consider the climax with the perforated wall and the knife at the window.) In their first feature, the Coens prove themselves already fully in control of finely-tuned cinematic storytelling. We’re a step ahead of the characters, but the film is a step ahead of us.

The Coens are also aware of our pleasure in their control. The characteristic Coen awareness, a sly recognition of letting the audience share their power over our access to the story world, is everywhere in evidence. I didn’t have time to mention the shot that everybody remembers, the tracking shot down the bar that simply lifts over the drunk sprawled on the bar top. We become aware of how the movie’s unfolding narration is absolutely ruling how we see this world, and the Coens make a gag out of it. Even the camera-god has a sense of humor.

If you have a chance to watch it, Jeff Smith, Kristin, and I hope you enjoy it–and, of course, the film, which is endlessly rewatchable.

As usual, thanks to the team at Criterion: Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Penelope Bartlett, and their superb postproduction boffins. We recorded the commentary under Covid conditions, with the expert guidance of Erik Gunneson, Meg Hamel, and James Runde.

For more on the Coens’ mastery of storytelling technique, check out the analysis of their fine The Ballad of Buster Scruggs.

You can sample other blog entries on mysteries and thrillers in several entries, in particular our discussions of Hitchcock (of course), and the genre as a whole (here and here and here). An early version of one chapter of my book in progress is devoted to the great Rex Stout. Another chapter will revise what I said about Gone Girl. I also discuss Hollywood’s approach to crime and mysteries in the book Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

Blood Simple (1984).

Oscar’s siren song: The return: A guest post by Jeff Smith

A Star Is Born.

As you probably know, Jeff Smith has been our collaborator on Film Art: An Introduction and our Criterion Channel series “Observations on Film Art.” For the last few years (here and here and here), Jeff has offered his thoughts on the Academy’s music nominees. This time around, he concentrates on the songs.

Here’s a brief preview of the Best Original Song category in this year’s Academy Awards. I also include a prediction for this year’s winner. Of course, I’d be the first to admit I don’t even win my own Oscar pool. So you’ll want to take that into account before making any wagers.

A good old-fashioned tune

Mary Poppins.

The Academy has a long history of nominating songs from live action and animated musicals. This year is no exception.

“The Place Where Lost Things Go” from Mary Poppins Returns fits that bill, giving Disney a third straight nomination in this category. (“Remember Me” from Coco and “How Far You’ll Go” from Moana are the others.) Like the Sherman Brothers, who wrote songs for the original Mary Poppins, Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman derived inspiration from British Music Hall.

In fact, although actor Lin-Manuel Miranda insisted that he didn’t want his character to sound like Hamilton, Shaiman and Wittman wrote a patter section of “A Cover is Not a Book” for him, enabling Miranda to show off his unique skill set. With its tricky wordplay and fast pace, the classic patter song is a forerunner of the rhymes spat by rap and hip-hop artists. As Shaiman noted, “So we got very lucky there because we didn’t want to feel like we were pandering to the audience, to supply Lin with rap that would seem anachronistic.”

“The Place Where Lost Things Go” sits on the opposite side of the musical spectrum as a soft, mid-tempo ballad scored for strings and winds. Fans of the original Mary Poppins will note that it bears more than a faint resemblance to “Stay Awake.” Both songs are sung to the Banks children at bedtime in an effort to inveigle them to sleep. Whereas “Stay Awake” shows the über-Nanny using reverse psychology, “The Place Where the Lost Things Go” is a paean to memory, loss, and grief. The children’s mother has recently died and they further risk losing their beloved house. Mary Poppins reassures the children that they will be reunited one day with all their loved ones and that, in the meantime, their mother will forever have a place in their hearts.

The number is beautifully sung by Emily Blunt and it captures the sense of melancholy that gives Mary Poppins Returns its emotional heft. Still, it seems like a long-shot to take home the award. I admire Marc Shaiman’s work. He has written some absolutely iconic scores in the past, like The American President. And I’d love to see him recognized this Sunday, even if it is just for his phenomenal work on South Park: Bigger, Longer, and Uncut. But I fear that an Oscar statuette with his name engraved upon it is also in the place where the lost things go.

When corn meets pone

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs.

The second nominee is David Rawlings and Gillian Welch’s “When a Cowboy Trades His Spurs for Wings.” It appears in the comically violent opening story of the Coen Brothers’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. It is sung as a duet by the titular character and the Kid, a mysterious gunslinger dressed in black. Buster has just been shot dead in a duel. In the song, the Kid imparts some lessons learned from his short, rugged life as a cowboy with Buster chiming in to provide harmony. Kid’s grimly acknowledges that he will suffer the same fate as Buster. It is just a matter of time.

Rawlings and Welch are long-time collaborators, having worked together on the former’s debut album. Rawlings has also produced albums by Welch and by Willie Watson, who plays the Kid. Adding to the sense of family reunion is the fact that Welch provided the voice of one of the Sirens in O Brother Where Art Thou? Among those enchanted by the Sirens? You guessed it – Tim Blake Nelson, who plays Buster.

In an interview in Variety, Welch describes the absurdity of the original pitch the Coens made to her and Rawlings:

It was a pretty straightforward thing: “Well, we need a song for when two singing cowboys gun it out, and then they have to do a duet with one of ‘em dead. You think you can do that?” “Yeah, I think we can do that,” she laughs.

In crafting the song, Rawlings and Welch pull off a rather neat trick. They’ve created something evocative of the “singing cowboy” films that inspired the first segment of The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. Yet is also connects with a larger tradition of mournful ballads that are part of folk and country music history. A lilting Texas waltz, the number is sparsely orchestrated, relying largely on guitar, harmonica, and vocals. The lyrics also make reference to a “bindling sheet.” As Welch noted, the word “bindling” was something she and Rawlings made up as a gesture toward the Coens’ fondness for anachronistic language. Yet it also works as a clever allusion to the “white linen” that is wrapped around a dying cowboy’s body in “Streets of Laredo.”

As was the case with Mary Poppins Returns, this song perfectly blends music and narrative, beautifully capturing the darkly humorous sensibility characterizing the Coens’ career. The lyrics are solemn, but Tim Blake Nelson’s yodeling lightens the tone to keep it from seeming maudlin. If I had a vote to cast, this is where I’d put it. Yet my gut tells me that the Academy’s beacon will shine on one of the other nominees.

A song for one of the Supremes

Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

The third nominee, “I’ll Fight,” was written by Diane Warren, a longtime Academy favorite. The song represents Warren’s tenth nomination, but she has never taken home top honors. This year, in an ironic twist, she may lose out to former co-writer Lady Gaga. (The two were nominated for “Til It Happens to You” in The Hunting Ground.) Warren admits that “I’ll Fight” is another of her “call to arms” songs as she has turned more of her energies toward films that support social causes.

One can easily make a solid prima facie case for “I’ll Fight” as the song to beat. It features a strong, soaring vocal performance by Jennifer Hudson, a previous Oscar winner for Dreamgirls.

Warren’s melody and lyric capture the inspirational vibe that is found in several previous winners, most recently “Glory” from Selma. And, of course, Warren herself seems long overdue.

Even so, “I’ll Fight” has a number of things working against it. It is featured in a documentary, and documentaries usually don’t get the exposure of more mainstream releases. It appears over The RBG’s closing credits, which mostly restricts the song to a summative function. And, unlike “All the Stars” and “Shallow,” the song failed to chart, an indication that it didn’t get much exposure in the music marketplace. I feel confident that Warren’s opportunity to make an acceptance speech will come someday. But on Oscar night, she’ll once again be the “bridesmaid” rather than the “bride.”

The battle of the titans

Black Panther.

For me, the race comes down to the remaining two nominees: “All the Stars” from Black Panther and “Shallow” from A Star is Born. Both tracks have gotten extraordinary exposure outside the films in which they appeared. The former was a chart hit in 25 countries, garnering steady radio airplay and thousands of streams and downloads in the process. The latter arguably did even better, charting in 40 countries, selling nearly 600,000 downloads and accruing almost 150 million streams. Both songs are fueled by star power: hip-hop sensation Kendrick Lamar for “All the Stars” and pop diva Lady Gaga for “Shallow.”

Lamar has just the right profile to woo Academy voters, even those in the music branch for whom “big beatz” and “flow” seem like foreign concepts. He has won thirteen Grammy Awards as well as the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for Music, becoming the first artist to do so from outside the domains of classical and jazz music. Billboard even compared Lamar to Shakespeare.

Although some music critics argue that “All the Stars” is not entirely typical of Lamar’s and SZA’s respective styles, it does fit beautifully with the overall vibe of Ryan Coogler’s pathbreaking film. The song begins with loping rhythms, electronic textures, and auto-tuned vocals. When Lamar drops the beat in the chorus, “All the Stars” gains intensity thanks to the layering of additional synthesizers and SZA’s melismatic topline.

The overall effect is one that neatly draws together Black Panther’s principal settings, being equal parts Wakanda and Oakland. The tension in the lyrics between the sung choruses and Lamar’s linguistic turns also restages the film’s central conflict: Prince T’Challah’s policy of peaceful co-existence vs. Killmonger’s thirst for violent world revolution. Appearing over the end credits, the number also works brilliantly with the shifting lines, shapes, and textures of the sequence’s graceful animation.

Lady Gaga, of course, supplies “Shallow” with its vocal fireworks. But she shares her nomination with three other collaborators, all of whom cut pretty large figures in the world of popular music.

Chief among them is superproducer Mark Ronson, who twirled the knobs on Gaga’s fifth album, Joanne in 2016. Ronson is perhaps best known for his smash hit, “Uptown Funk.” Yet, Ronson had already won three Grammy’s for his production of Amy Winehouse’s Back to Black long before he gave us his Bruno Mars earworm. Besides his production work for Gaga, Winehouse, and Mars, Ronson has collaborated with a “who’s who” of current stars and pop music legends: Adele, Lily Allen, Miley Cyrus, Kaiser Chiefs, Chance the Rapper, Janelle Monae, Duran Duran, Nile Rodgers, and Paul McCartney.

One of Ronson’s other songwriting partners, Anthony Rossomondo, shares the nomination for “Shallow.” Rossomondo is a guitarist and trumpet player who was a founding member of Dirty Pretty Things and toured with the Libertines as Pete Doherty’s replacement. Fans of British television might also remember Rossomondo as Pete Neon in The Mighty Boosh, the surrealist comedy series about a pair of failed musicians working in an alien shaman’s magic shop.

Rounding out the quartet of songwriters is Andrew Wyatt, still another songwriting partner of both Ronson and Gaga, who also penned tunes for Mars, Lil’ Wayne, Beck, Florence + the Machine, and former Oasis bad boy, Liam Gallagher. Wyatt also has previous experience writing for film. He composed four songs for the Hugh Grant/Drew Barrymore romantic comedy, Music and Lyrics, including the wonderful pastiche of eighties New Wave, “PoP! Goes My Heart.”

With so much musical talent on board, it is hard to see how “Shallow” could miss. Yet the song’s many virtues are enhanced by its perfect placement in the story. It was a lot to expect that one song could deliver something that a) pays off the romantic sparks of Ally and Jackson’s initial flirtation; b) signifies Ally’s leap of faith as she returns to the stage to complete Jackson’s arrangement of her song; and c) convince the audience that Ally could legitimately be the proverbial overnight sensation of the film’s title. “Shallow” delivers on all that and more.

The song begins with Jackson singing, “Tell me something, girl.” The first verse is sparely arranged for just voice and acoustic guitar. Jackson essentially baits Ally into claiming a spotlight he believes is rightfully hers. When Ally comes on stage, she begins the second verse in the lower part of her vocal register, adding a husky sensuality that captures the slow-burn of the couple’s simmering passions. Piano, violin, and pedal steel guitar slightly thicken the arrangement while maintaining the relatively soft dynamic level. An octave leap leads into the chorus, which Ally belts out with newfound confidence.

The lyrics serve as a metaphor for the character’s personal journey, her willingness to take the emotional and professional risks that Jackson had encouraged. This is Ally’s moment of self-realization. Yet it also foreshadows the relationship’s failure by previewing a future in which her stardom will overtake his.

This is followed by Jackson and Ally finally harmonizing together on the phrase, “In the shallow, the sha-ha-low.” Their voices blend, suggesting the consummation of their romantic connection onstage, if not yet in bed. Ally follows with a kind of vocal cadenza. No longer bound by lyrics, she sets free the “yargh” in her voice that rock critic Greil Marcus famously ascribed to Van Morrison’s Irish soul.

The addition of drums and bass enhance the big crescendo that leads into the final chorus. Jackson joins Ally at her microphone and the two finish the song with a final duet. The song is in G major, but ends on an E minor chord, another subtle hint of the sadness that ultimately consumes couple’s relationship.

As an Oscar nominee, “Shallow” has a lot to offer. It is a duet between a major movie star and a major star of the recording industry. It not only pays off a previous dangling cause, but also foreshadows later plot developments. Best of all, it takes the audience on an emotional journey that symbolizes the characters’ story arcs in microcosm. If the snatch of “Shallow” heard in the A Star is Born trailer proved surprisingly meme-worthy, the full performance of it in the film was indelible. Moreover, in a cheeky bit of self-mythologization, it invites viewers to consider “Joanne,” the flesh-and-blood being that sits just behind the Gaga mask.

Prediction: “Shallow”

I likely tipped my hand earlier, but I fully expect Lady Gaga and company to add Oscar to the Grammy and Golden Globe they’ve already won. If that happens, I’ll be content with the result, even if the memory of Tim Blake Nelson and Willie Watson’s duet tickles me every time I think of it. I’ve enjoyed Mark Ronson and Lady Gaga’s music for more than a decade. And if nothing else, an Oscar for Andrew Wyatt will balance the scales of justice. Back in 2008, I felt Wyatt was robbed when he failed to secure a nomination for a song Billboard called “the greatest fake 80s song of all time.” Well, if I see Wyatt clutching an Oscar come Sunday, you’ll hear a little PoP! go in my heart.

For an alternate take on this year’s music nominees, a real pop star from the eighties, Thomas Dolby, offers his perspective here. A report on a panel discussion at the Los Angeles Film School featuring several of the nominees can be found here.

Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman talk about their work on Mary Poppins Returns here and here.

Gillian Welch discusses working with the Coen Brothers on The Ballad of Buster Scruggs here and here.

Diane Warren offers her perspective on writing “empowerment anthems” here and here. A deep dive into Warren’s career can be found on a Hollywood Reporter podcast featuring the 10-time Oscar nominee.

Finally, much ink has been spilled about the process of writing “Shallow” for A Star is Born. You can read more here and here and here and here.

Jeff Smith has provided us many guest blogs related to film music, most recently his discussion of the score for True Stories.

Music and Lyrics (2007).

The spectacle of skill: BUSTER SCRUGGS as master class

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018).

DB here:

Craft isn’t everything in art, but it counts for a lot. Even when you’re going against tradition, you can’t just willy-nilly do whatever. You need to create a counter-craft (as Bresson, Brakhage, Ozu, and others showed us). Reviewers, in their urge to thump out quick judgments, often don’t address craft practice directly. So if we simply talk of the Coens’ Ballad of Buster Scruggs as a grim, occasionally grotesque and zany take on Western conventions, we’re apt to take for granted just what a trim, absorbing piece of sheer filmmaking it is.

It’s worth attuning ourselves to what Adam Gopnik called his collection of Robert Hughes’ writings: The Spectacle of Skill. Paying attention to that enhances our appreciation for what filmmakers accomplish, and maybe it can nudge aspiring filmmakers to consider things to try.

So, herewith a quick analysis of the very beginning of the film’s second episode. The whole piece is not as audacious as the title episode, and not as poignant as “Meal Ticket” or “The Gal Who Got Rattled.” It’s more of a light interlude. But we shouldn’t let its shaggy-dog payoff (“Your first time?”) make us think there’s anything slapdash about it.

There follow spoilers.

All the meanness in the Used-To-Be

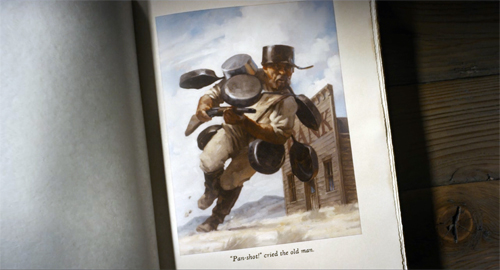

In the book that frames each tale, this one is called “Near Algodones.” As in the other episodes, an illustration prepares us for something we’ll see in the scene. The caption reads: “Pan-shot!” cried the old man.

Lesson 1: Make everything clear and simple, except what you want to suppress.

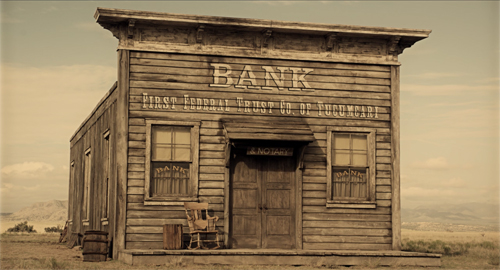

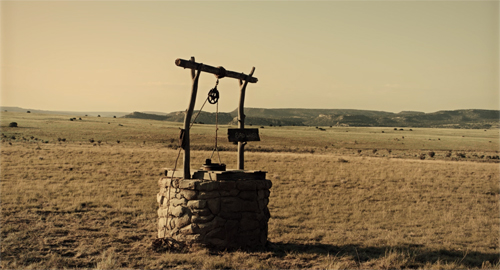

A master shot gives us the elemental situation: A bank, a well, and a lone rider with his horse.

These are the central components of the sequence. The isolation of the bank makes it a plausible target for a holdup. The geography will become important in the second stretch of the scene, while the well will provide cover to the Cowboy. His horse will prove notably reluctant to move.

Lesson 2: Attach the narration to a single character.

Throughout this episode, we’re “with” the Cowboy, not always through exact optical POV but more generally: our range of knowledge of the unfolding situation approximates his. This sort of restriction arouses curiosity (what’s going on in the bank?), as well as suspense and surprise (as we’ll see).

Lesson 3: Motivate new shots by offscreen sound.

Attachment to the Cowboy is reinforced by the play of his attention. Over the Leone-esque close-up we hear a creak. This motivates a cut to the bank’s hanging sign. As we hear a thump, he shifts his eyes; we see it’s caused by the bucket bumping against the well.

Lesson 4: Delay when you can.

Attachment doesn’t mean immersion. Instead of a shot from the Cowboy’s POV as he’s entering the bank, we get him pausing to size up the scene.

Only then do we get a shot of the bare bank and the teller’s windows, which (thanks to a wide-angle lens) seem impossibly far away.

Lesson 5: Let expectations go to work.

The holdup scenario, a convention of Westerns, is surely hovering in many viewer’s minds. When the Cowboy advances, we wait to see if our expectations pay off. You get suspense simply by having your actor move forward; what could be more economical?

Lesson 6: Prepare for later shots.

The tracking shot of the Cowboy’s boots and spurs might seem mere decoration, but it further delays his arrival at the window and sets up an important shot to come.

Lesson 7: Scale your shots according to the information they present.

Reverse shots are the workhorses of mainstream storytelling cinema. They are vehicles for character interaction, either based in dialogue or just the exchange of glances. The over-the-shoulder (OTS) version specifies the spaces the characters occupy, typically in a conversation. OTS framings also serve as a transition to closer views. Here the Cowboy’s goal in the scene is to learn how fortified the bank is against robbery.

After the opening stretch of purely visual storytelling, dialogue takes over. For us to grasp it better, the OTS framings give way to singles, which enlarge the teller’s performance and the Cowboy’s reactions.

The geezer’s chatter joins the motif of flowery monologues and eloquent bafflegab we’ll encounter throughout the film. The framing also lets us enjoy the performance, which suggests that this scatterbrain might be an easy mark. He does, however, mention that he has put down one attempted robber and “shredded the legs” of another.

The climax of the exchange is the Cowboy’s drawing his pistol and the teller’s explanation that he has to stoop to get “the large denominations.” The result is more shot-scale calibration: We need a single to see the gun looming (an OTS wouldn’t be as punchy), but the reverse shot can be OTS because we need to see how the teller’s stooping maneuver is concealed from the Cowboy. We are still attached to him and what he knows–or doesn’t know.

Another benefit: as variants of framings we’ve seen before, these let us quickly grasp what’s new in them (brandishing the pistol, ducking down).

Lesson 8: Use a cut, a crisp gesture, or a discrete sound to arrest attention.

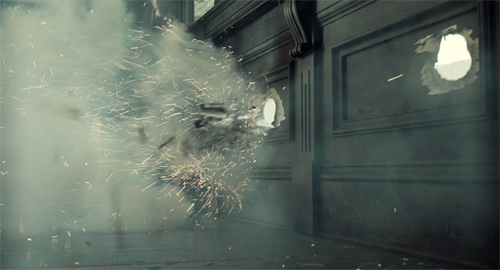

Actually, the next shot does all three. The Cowboy tries to peer over the till, and a shot shows him taking a step forward as we hear a click. This framing pays off the shot of striding boots we saw in Lesson 6.

Within the same shot, the front of the teller’s window is blasted open. The Cowboy jumps sideways as another hole explodes, then another.

We’re back to visual storytelling. Now we understand why the teller has “shredded the legs” of another would-be robber. When the debris clears, a camera tilt shows that the Cowboy has sprung to the counter.

A mini-spectacle of skill: Handling the three blasts and the Cowboy’s evasion in a single percussive shot.

Lesson 9: Stagger the reveals.

Alexander Payne once remarked: “Whenever you can do a reveal, do it.” Here we have a suite of reveals, but they’re handled in a simple, cogent way.

When the Cowboy crouches on the counter, we have several questions. Is the teller going to fight? What created the blasts? And will the Cowboy get to the money?

These questions are answered, purely pictorially, in the shots to come. First, from his perch the Cowboy sees the partly open door. The teller has escaped, but because we’re restricted to the Cowboy’s perspective, we don’t know where he’s gone.

Just as one concise shot showed us the gunblasts and the Cowboy’s leap to the counter, now his descent and landing, followed in a single tilt, reveals the teller’s infernal machine: a row of shotguns poised to fire.

Another director would have devoted a POV shot to this revelation, but here it’s provided without fuss or forcing, as we follow the Cowboy’s crouch. He barely reacts and smoothly sets about finding the money. He grabs it in a single crisp close-up. And another cut takes us to the doorway, as the Cowboy hopes a view outside will reveal where the teller has gone.

Once more a POV is recruited, but it shows how much our protagonist doesn’t know.

The elements we were given at the start–bank, well, horse–are laid out again, from the opposite angle. Thanks to the clarity of presentation, we fully understand that the old teller is hiding somewhere (probably with his lauded scattergun) and the Cowboy has to make a run for it. But to where?

There are other things to talk about here, such as the homages to Leone (the mention of Tucumcari from For a Few Dollars More, the creaking of the sign recalling Once Upon a Time in the West‘s operatic opening). Perhaps the device of the book owes something to William S. and Mary Hart’s Pinto Ben (1919).

But we’re so used to considering the Coens pasticheurs that these allusions don’t interest me as much as the compact finesse of their style.

The rest of this scene will depend on reworking the narrative, auditory, and pictorial elements we’ve already encountered. You could go through that, and indeed the rest of the film, and trace the artisanal precision on display. (Let alone the sheer boldness of certain depth shots.) And the Coens are expert at using visual ideas for humor, as in the later scene when the Cowboy’s horse, browsing for more grass to nibble, stretches his noose-rope to the limit (see top image).

But I think I’ve said enough to indicate how rich an apparently straightforward handling can be. When we speak of careful pacing; when we think of building a scene; when we think of a movie that’s easy and graceful to follow, what Otis Ferguson called “a smooth clear line”–this is what we’re talking about.

There’s plenty of spectacle here, what with landscapes and gun blasts, but there’s another sort of spectacle as well: the quiet virtuosity of craft. You don’t see it that often these days, so when we encounter it, we should acknowledge it.

For another study of the Coens’ technique, see Jim Emerson on No Country for Old Men.

Other blog entries celebrate this sort of precision. See, for example, this analysis of Panic in the Streets, or the mind-boggling visual engineering of Fritz Lang (here and here). Otis Ferguson’s ideas about smooth cinematic storytelling are discussed in The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture.

My first impressions of Scruggs, after seeing a magnificent big-screen presentation in Venice, are here. Netflix and Annapurna are to be congratulated for backing this movie, but it really deserves a wider theatrical release than it got. At least, please give us a Blu-Ray!

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018).

Venice 2018: Assorted malefactors

Ying (Shadow).

DB here:

You don’t have to be an addict of crime fiction to notice that bad behavior–from lying and cheating to assault and murder–is a prime motivation in all genres of storytelling. A gripping plot often depends not on innocent mistakes but something worse: an assassination plot (Macbeth), a savage robbery (Crime and Punishment), wicked mind games (Les Liaisons dangereuses). Some of my favorite films from the latest Venice Film Festival feature scurrilous intrigue and a whole lot worse. Hell, in one movie the subject was happy to be compared to Satan, and that was a documentary.

Shadow warrior

After the extravagantly peculiar Great Wall, Zhang Yimou has come back with a more sober, somewhat arty wuxia drama. Leaning a bit on the premise of Kurosawa’s Kagemusha, Ying (Shadow) presents a king trying to reclaim territory with the aid of a crafty general. But he’s relying on a ringer; the real general languishes in a secret chamber recovering from a severe wound. Court intrigue–the general’s wife falls in love with her husband’s double, the king’s sister resents his manipulation of her–builds toward a massive military attack on the Jing stronghold. The sister, in rebuff to the enemy’s insult to her, enlists in the ranks as well.

It’s quite a show. For one thing, Zhang has reengineered the color-design principles of Hero. There each flashback episode was keyed to a different palette.

In Ying, the settings exist almost entirely in deep blacks and soft grays. For most of the film, only flesh and blood are given in their natural colors, and even then they are pastels.

For another thing, in contrast to the overcast skies of Hero and in perhaps another Kurosawa nod, here it’s almost always raining. This constant downpour extends the gray-black color palette of the palace to the massive landscapes.

Above all, the training of the young imposter in a technique of fighting with a metallic umbrella leads to some memorable combat sequences. Little do we realize in the initial practice sessions that the umbrella technique will expand on a grand scale. Pei’s troops invade a town using umbrellas as bobsleds, and they attack the enemy with umbrellas as scythes and buzzsaws. Despite the fact that digital rain doesn’t bounce off shoulders or trickle down the tracery of armor, the water-drenched attack at the climax of Ying yields the tingling sense of tactile spectacle that we’ve come to expect from the maker of Red Sorghum.

Cops and/as crooks

Dragged Across Concrete (production still).

In another but not wholly different genre, we have S. Craig Zahler’s Dragged Across Concrete. I was unfamiliar with his two earlier features, Bone Tomahawk and Brawl in Cell Block 99, though alert viewer Dave Kehr urged me to see the latter last year. (I tried, on streaming, but I gave up because the image was too small; Zahler’s eye is calibrated for the big screen.) Now, seeing this latest enterprise smashed across the Lido’s Darsena screen, I’m here to declare myself a fan.

It’s got a neat structure. There are two protagonists. We’re first introduced to Henry Johns, a discharged prisoner. He’s ready to reenter a life of crime to keep his disabled brother safe and rehabilitate his mom, who’s tricking to support her drug habit. After twenty minutes, he drops out of the plot and we pick up Brett Ridgeman, a cop whose menacing interrogation techniques, captured on cellphone video, result in a suspension. Pressed by money problems and his wife’s MS, Ridgeman decides to get “proper compensation” by ripping off a gang planning a heist. Of course Henry and Ridgeman’s trajectories intersect, while drawing in others: Henry’s sideman Biscuit, Ridgeman’s partner Anthony, and a woman working at the company that’s the target of the robbery.

At two and a half hours, Dragged Across Concrete might seem to be an overinflated genre movie, but it owes its leisurely pace, I think, to the tradition of crime novelists like Lionel White, George V. Higgins, Elmore Leonard, and George P. Pelicanos. In their work crime, duplicity, betrayal, and revenge are at the center of a web of human relations. Unrestricted narration follows outlaws, cops, and bystanders whose fates will be intertwined with acts of violence. You need a certain amount of time to give solidity to the lives of these stakeholders in criminal action.

The sweep of such plotting allows us to appreciate irony, especially when characters misjudge each other’s motives. In Zahler’s film, the split structure of the narration–setting up Henry before we see Ridgeman–pays off in several ways. Having access to the frustrations that push Henry back into crime allows us to judge Ridgeman’s occasional bursts of bigotry as both understandable (given the treatment of his daughter in the neighborhood) but no less hateful. At the climax, there’s a crisis of trust that depends on mutual ignorance. Both Henry and Ridgeman err because each man doesn’t know something crucial about the other.

The film’s length is also warranted by Zahler’s classical approach to composition and cutting. He knows how to exploit anamorphic widescreen, to let the camera stay still and watch action unfolding.

The film’s title summons up Sam Fuller sensationalism (and Zahler’s overheated prose in his novels isn’t far removed from Sam’s). But the film reminded me of Jean-Pierre Melville and Kitano Takeshi, partly for the laconic dialogue but also for the deliberate pacing. (The average shot length is 6.5 seconds, about twice what we find in most Hollywood movies today.) Lacking Tarantino’s self-congratulatory flamboyance, Dragged Across Concrete exemplifies the power of a dry but not unemotional approach to genre conventions.

The Forties, yet again

Charlie Says.

Police thrillers like Dragged Across Concrete became salient creative options in the 1940s, as I tried to suggest in my book about that era in Hollywood. Other 1940s options surfaced in two other crime-based movies I saw at Venice.

The first, rarer choice, was the chaptered film, the movie broken into blocks that are marked as distinct. Meet Me in St. Louis does it by season, Holiday Inn by, well, holidays. We’ve become used to chaptering since Pulp Fiction revived the scheme.

In The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, Joel and Ethan Coen literalize the technique by beginning with an old-fashioned book consisting of six chapters. The tales all center on the American West, and each one is introduced by a captioned color plate and ends with a glimpse of the closing passages of text.

This direct address to the audience is carried on in the first episode, “You seen ’em, you play ’em.” Here the gunslinger Buster Scruggs tries to charm us while singing “Cool Water.” The conceit is that a fancy-pants singing cowboy is planted in the grubby, dangerous west of actual history.

At first Buster dispatches fast-draw artists, but when he meets his match he’s lofted to heaven in a goofy cadenza that recalls stretches of The Big Lebowski.

Thereafter we get tales of bank robbery and lynching (with a shaggy-dog punch line), a bleak carnival sideshow, gold prospecting, a wagon train, and a mysterious stagecoach ride. All are rendered with the patented Coen panache. Such a pleasure to see a movie that is designed, from first frame to last, to give you time to see everything. The Coens’ love of the grotesque, their eagerness to satirize movie conventions while still honoring them, their parodic side (e.g., the opening Leone riffs), and their gift for gorgeous landscapes and catchy tunes–all are here.

Still, the wagon-train episode, much in the spirit of True Grit, shows that not everything is fodder for mischief. The highly formal, archaic dialogues and grave sincerity of the performances in this section are for me deeply moving. The chaptering device itself carries a certain warmth; we might be kids discovering a great-grandparent’s childhood reading.

Mary Harron’s Charlie Says uses a more common 1940s template, that of an inquiry that triggers flashbacks to the past. It’s also, as Harron notes, a woman-in-prison movie. Karlene Faith is a feminist and social activist who counsels three women on Death Row. They participated in the murders instigated by cult leader Charles Manson. As she gets to know them and they probe her own life, we’re shown increasingly brutal episodes of their absorption into Manson’s brood.

The task of Harron and screenwriter Guinevere Turner was to make the women sympathetic and comprehensible. The script might have offered mini-biographies showing how each one’s unfulfilled life led her to fall prey to Manson’s manipulation. Instead, they make one woman, Leslie nicknamed Lulu by Charlie, our primary focus, and through her they lead us gradually into the monstrous crimes.

The early flashbacks, attached to Leslie as she enters the fold, emphasize Manson’s rather mild, almost offhand seduction style. At first he comes across as a gentle, guitar-strumming hippie wooing his followers with a lifestyle challenge: Give up consumerism, learn to live simply, share the love. Certain signals–the men always eat first, Charlie has claim on all the women–are outweighed by Manson’s glowering conviction and the group’s hopes that his songs will earn a record contract.

The flashbacks trace a shift from communitarian idealism to “subversive” rock music (the coded message in the Beatles’ “Helter Skelter”) to whacked-out politics. (Manson promises a race war in which blacks will need a leader like him.) Men as well as women fall under Charlie’s patriarchal management style. By the end, murdering the piggies through home invasion comes to be the ultimate test of Manson family values.

The flashbacks, shot in a nervous style in sun-soaked terrain, contrast with the locked-down camera and drab prison surroundings of the present. The unpretentious production values are matched by a sober style that favors the performances, particularly those of Hannah Murray, Merritt Wever, and in the flashiest role Matt Smith as Manson. In all, it’s a very worthy, unsensational effort to understand how naive idealism can be recruited by lunatic evil.

Better to reign in Hell

American Dharma (production still).

Speaking of lunatic evil, Donald Trump has had many abettors and acolytes, but few are as clever and intellectually pretentious as Steve Bannon. Errol Morris’s interview film, American Dharma, premiered at Venice and was put to the blade in the press conference.

Reporters’ objections seemed to me twofold.

You were too easy on him. You didn’t pose enough hard questions and you cut away when he fell silent. Morris replied that this was an investigation, not a debate. He wanted to probe Bannon’s worldview, not “pin him to the wall, like a butterfly expert handling a specimen.” And Morris does push Bannon on several points, notably the contrast between his apocalyptic intentions (Trump is the “blunt-force candidate, an armor-piercing shell”) and his earnest claim to be fighting for those people who want a stable, steady life. For my part, I thought that Morris scored points whenever the garrulous Bannon didn’t reply or changed the subject.

In addition, Morris peppers Bannon’s discourse with montages of cutaways to internet news and commentary. Like the newspaper headlines of The Thin Blue Line and Tabloid, this swarm of Facebookings, Twitteries, and soundbites acts as both challenge to what’s been said and a reminder of how the media snatch up phrases and images and spew them back at us, complicating and sometimes obscuring our understanding. At the very least, we’re reminded that there is pushback to virtually every lie put forth by the Trump regime: the Resistance will be videoized.

Nothing new here. What did we learn from this? Well, said Morris, we learn that “at the heart of his beliefs is a deep self-deception.” Morris challenged Bannon to explain how, if he believes that Trumpism is a populism on behalf of the forgotten middle class, all his policies are aimed to strengthen the wealthy and weaken the ordinary citizen. Bannon got quiet. And though Bannon claims to be a rationalist, he soon enough rails against rationalism.

All of which makes him a guy who has given a tongue bath to the Blarney Stone. A Hollywood investor with ties to the videogame industry, Bannon strikes me as less a thought leader than a canny VC opportunist, spraying out memes like a scriptwriter in a pitch session. He even assures us solemnly: “The medium is the message.” In his cascade of clichés I saw the desperate self-confidence of a hip boomer who wants to be the brightest boy in the meeting.

Along these lines I thought I learned something else important. Bannon the vaunted intellectual gets his inspiration from pop culture. Most of what I’ve read about his ideas emphasize their philosophical pedigree–his readings in Eastern and Western religion, his defense of Julius Evola–but it turns out that Bannon is a geek like the rest of us.

When he draws life lessons from Paths of Glory and The Searchers, Morris punctures these absurd pretensions simply by literalizing them. This creep casts himself as Kirk Douglas or John Wayne? Like Falstaff in Chimes at Midnight, Bannon claims, he has prepared a carouser for rule before the pupil betrays the mentor. So Morris straight-facedly inserts Welles’ footage, and Bannon, no Fat Jack, is thereby shrunk. Likewise, Morris makes monumental fun of Bannon’s shallowness by building a duplicate of the Quonset hut of Twelve O’Clock High, Bannon’s favorite movie. In this set Bannon, not exactly Gregory Peck, is interrogated before Morris sets it ablaze.

When he draws life lessons from Paths of Glory and The Searchers, Morris punctures these absurd pretensions simply by literalizing them. This creep casts himself as Kirk Douglas or John Wayne? Like Falstaff in Chimes at Midnight, Bannon claims, he has prepared a carouser for rule before the pupil betrays the mentor. So Morris straight-facedly inserts Welles’ footage, and Bannon, no Fat Jack, is thereby shrunk. Likewise, Morris makes monumental fun of Bannon’s shallowness by building a duplicate of the Quonset hut of Twelve O’Clock High, Bannon’s favorite movie. In this set Bannon, not exactly Gregory Peck, is interrogated before Morris sets it ablaze.

I didn’t think that the journalists in the press conference gauged the ways in which Morris made Bannon seem naive. But I always forget that a hermeneutics of pop-culture justification, with The Simpsons and The Matrix fodder for philosophers trying to fill their courses, is taken for granted now. Bannon encountered Twelve O’Clock High when it was taught as a leadership model in, of all places, Harvard Business school. To my mind, Morris shows that the would-be highbrow’s search for allegories in mass culture is a caricature of serious thinking.

Another piece of news: Bannon admits to being a Miltonic rebel angel, one who would rather reign in Hell than serve in Heaven. Think about that. Morris got Bannon to embrace Satan. He asked, with justification: “How many interviewers have done that?” Errol Morris, boy detective, may have revealed the real puppeteer behind Trump’s coup d’état: the petty overachiever swollen with dreams of grandeur drawn from movies.

This is my last dispatch from a festival that became a high point of my cinephiliac life. Apart from seeing fine films in splendid circumstances, talks with Dave Kehr, Chris Vognar, Michael Philips, Glenn Kenny (some choice reviews here), Stephanie Zacharek, Mick LaSalle, Kim Hendrickson, Peter and Françoise Cowie, Alberto Barbera, Michel Ciment, Olaf Möller, and other friends have set me thinking ever since.

As ever, thanks to Paolo Baratta, Alberto Barbera, Peter Cowie, Michela Lazzarin, and all their colleagues for their warm welcome to this year’s Biennale.

For more Venice snapshots, see our Instagram page.

October 31, 2018: Netflix has announced that The Ballad of Buster Scruggs will be narrowly platformed starting November 8 and will premiere on its streaming service on November 16; also on the 16th it will show in selected theaters in the US and Europe, as well as Toronto.