Archive for the 'Directors: Cuarón' Category

Harry Potter treated with gravity

Kristin here:

Going into the summer movie season this year, I wasn’t particularly excited about most of the upcoming films. I was looking forward to Monsters University, which I thoroughly enjoyed, though it didn’t return to the dazzling levels of Pixar’s films before Cars 2. Right now I’m assembling my viewing list from the impressive array of offerings at the Vancouver International Film Festival. (The new Oliveira! Godard in 3D! Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s long-awaited return to filmmaking!)

But I’m also aware that during the festival, another film that I’m really excited to see will be released in North America: Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity. I didn’t see the 17-minute opening shot shown at Comic-Con, but I watched one of the trailers, and it was the most exciting new piece of filmmaking I’ve seen this year. If you haven’t seen one of the four trailers, you can watch them on Warner Bros.’s site, or on any number of video and infotainment sites. The one called “Drifting” reminded me of Michael Snow’s brilliant Central Region, but with narrative, with the earth and stars spinning past a close-up of Sandra Bullock as the marooned, panicky astronaut protagonist.

Unfortunately a still frame conveys almost nothing of the dazzling effect of this image. You’ll just have to follow the link above and look for yourself.

Judging by the ecstatic reviews and descriptions of audience responses that came out after Gravity was screened as the opening-night gala at the Venice Film Festival, the movie lives up to the expectations generated by the clip and trailers. One of the most insightful reviews is by Todd McCarthy, who combines giddy enthusiasm (mentioning twice that people will want to see the film repeatedly) with some solid analytical comments on the soundtrack, camerawork, and special effects. After Cuarón screened the film for James Cameron, the latter enthused: “I was stunned, absolutely floored. I think it’s the best space photography ever done, I think it’s the best space film ever done, and it’s the movie I’ve been hungry to see for an awful long time.” Indiewire’s Steve Greene has compiled a selections of excerpts from reviews from the Venice opening.

Cuarón’s previous film had been Children of Men, released way back in 2006. After such a gap, authors of articles and reviews have felt the need to summarize his career briefly. Most frequently they mention Children of Men and the 2001 Mexican comedy Y tu mamá también, which was a breakthrough film for the director. Less frequently there is a reference to Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004) and A Little Princess (1995).

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban in Cuarón’s career

Living paintings in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azakaban

As that line-up of titles suggests, Cuarón has had a career that makes him difficult to characterize. Although he is perceived as a Mexican director, he has done relatively little work there. Apart from shorts and TV projects, his Mexican features consist only of Love in the Time of Hysteria (Sólo con tu pareja, 1991) and Y tu mamá también. He’s also perceived as an art-film director. Variety′s cover story on Gravity was entitled “An Auteur’s Re-entry” in the September 3 print edition (though it was “Alfonso Cuaron Returns to the Bigscreen after Seven Years with ‘Gravity’ online). This impression obviously arose from the success of Y tu mamá también (distributed in the USA by Good Machine, now Focus Features) but also from the fact that the grim Children of Men was a financial flop and succès d’estime. Yet Children was produced and distributed within the Hollywood mainstream by Universal.

Instead of pursuing his career in Mexico, Cuarón headed for Hollywood immediately after his first feature. He described this career move in a 2006 interview:

After coming up the ranks as a cable operator on a movie set and an assistant director, he made his first feature, “Sólo con tu pareja,” in 1991, and it won several awards at the Toronto Film Festival. However, the Mexican Film Commission, which had subsidized it, wasn’t happy with the movie.

“I basically burned my bridges with the commission,” says Cuarón, who moved to Los Angeles with no contract to do another film. Director-producer Sydney Pollack gave him a chance to shoot an episode on the cable TV series, “Fallen Angels.”

“Tom Cruise had directed one episode and Tom Hanks another. But mine was the one that won a cable award,” Cuarón says. “It was one of those things that led to the next.”

That turned out to be the sublime children’s movie “A Little Princess.”

“I never watch my movies after I’m done with them, but in my memory that’s the one I love the most,” he says.

Cuarón’s next experience directing a modern-day version of “Great Expectations” [1998] starring Gwyneth Paltrow and Ethan Hawke, wasn’t so great.

“My instinct always told me not to do it, and I ended up doing it anyway,” he says. “So I learned to trust my instinct.”

Also in this interview, Cuarón describes himself as lucky in his Hollywood work:

That a major studio (Universal) was willing to underwrite such a downbeat story [as Children of Men] is a credit to Cuarón’s reputation. Unlike many foreign directors used to having enormous latitude in their native countries, Cuarón has learned to work within the Hollywood system.

“There is a tendency to see Hollywood like Darth Vader trying to destroy filmmakers,” he says. “And I’m sure that’s sometimes true. I have been very lucky to be able to create my own stuff without studio interference.”

The perception of Cuarón as an art-film director has perhaps led to a tendency to dismiss his one venture into the Harry Potter series as an aberration. In his excellent analysis of the long takes in Children of Men (which focuses on the fact that they were created by digitally blending multiple takes), James Udden remarks on how, after first using long takes in Y tu mamá también, “Next, Cuaron takes a ‘step back’ in a sense with Prisoner of Azkaban, paying yet more ‘dues’ to the system.” Justin Chang’s brief but informative survey of long takes in Cuarón’s work does mention that the technique “even reared its head in 2004’s ‘Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban,’ in which the director boldly imprinted his personality onto one of Hollywood’s most successfull–and most risk-averse–franchises,” though he does not mention how the technique “reared its head.”

Yet Cuarón evidently loved his experience working on Prisoner of Azkaban. The interview just quoted was one of several in 2006 where he expressed keen interest in making another film in the series: “If I’m invited, I would be very tempted to direct it. The idea of revisiting that beautiful universe is irresistible [….] Everything that happens around a J. K. Rowling creation is enveloped in this beautiful, beneficial energy.” Maybe he will have a chance to work on a Rowling film again, given the recent announcement that she will write the script for a franchise-starter for a new film series based in her wizarding world.

Setting aside Cuarón’s feelings about his experience making the film, we should not dismiss it as a minor part of his career, something he supposedly made so that he would be able to make other, more personal projects. For a start, it does have a style distinctly different from the other Harry Potter films. It’s not always recognizable as a Cuarón style, but then, Cuarón’s films are so different from each other that that is hardly surprising. Udden points out that while Children of Men has an average shot length of slightly over sixteen seconds, Prisoner of Azkaban′s ASL is about 5.5 seconds. Still, it contains three long takes, each of considerable interest. Moreover, the introduction to cutting-edge CGI would leave Cuarón with valuable experience that he could apply to his two subsequent features.

Prisoner of Azkaban has a reputation as one of the best, if not the best, of the Harry Potter films. Its quality is not solely due to Cuarón’s direction. The book is arguably also the best of Rowling’s series. While the first two books (Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone and Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets) are pleasant, entertaining children’s stories, Prisoner of Azkaban marks a leap in the complexity and depth of the plotting. It adds two major new characters, the sympathetic professor (and werewolf) Remius Lupin and the apparently threatening Sirius Black, who turns out to be Harry’s parents’ best friend and his godfather. It also adds a third character, the dotty Prof. Trelawney, who seems just to offer a source of comedy but will eventually prove to have affected Harry’s life in unsuspected ways.

New villains also appear, notably the soul-sucking Dementors and the literal and figurative rat, Peter Pettigrew, another old friend turned traitor who has become Voldemort’s main helper. Lupin introduces the technique of casting a “patronus,” a protective figure of light that repels the Dementors–something that will continue to be crucial for the rest of the series. Finally, there is the ingenious episode of the time-turner, a device Hermione has been employing to take multiple classes at once but which she ultimately uses to allow her and Harry to go back in time and manipulate a series of tragic events and make them end happily. This lengthy scene, one of the high points of Rowling’s series, is even better in the film, where we can see the doubled characters on the screen.

Apart from drawing on the book’s strengths, the film also has the advantage of being the one that replaced Richard Harris with Michael Gambon as Dumbledore. Apparently some viewers were fond of Harris’ portrayal, but the casting seems to me a real mistake and no kindness to an actor clearly in failing health. I found him disturbingly feeble, stiff in his movements and expressions, and barely able to get a whole line out without gasping for breath. How the producers thought he could last through the series is a mystery, and Gambon’s livelier and funnier performance came as a relief.

Prisoner of Azkaban also quickly gained a reputation as being much darker in tone than the two films that preceded it. I doubt there was a single reviewer who failed to make this claim. The Washington Post’s critic called it “everything the first two films were not: complex, frightening, nuanced.” For Roger Ebert, “Harry’s world has grown a little darker and more menacing.” In a later survey of the first four Harry Potter directors, Manohla Dargis and A. O. Scott wrote of Prisoner of Azkaban, “the tone and color palette have shifted, the bright, flat lighting giving way to a somber and dangerous feel, evocative of horror films.”

Perhaps such comments had something to do with the fact that Prisoner of Azkaban earned less at the box office than any other film in the series: a mere $797 million. (The second lowest earner, Chamber of Secrets, made $879 million; the highest, Death Hallows Part 2, $1.3 billion.) It’s hard to believe that fewer people would go to the film based on a change of directors. How many, after all, would be likely to know who Cuarón was? More likely parents kept younger children away for fear that the action would be too intense.

The book version of Prisoner of Azkaban also takes a much darker turn. If that was the reason for the downturn, it didn’t last long. The trend toward darker, scarier content continued through the later books, with the return of Voldemort in the fourth and the deaths of major characters in each subsequent book. Similarly, the later films are distinctly more grisly and frightening than Prisoner of Azkaban. None of this kept people from buying books and movie tickets.

One might assume that studio executives decided on Cuarón as an appropriate director for a darker entry in the series, but he had not yet gained a reputation for grim subject matter. That came with Children of Men. In fact, Cuarón was not the first or even second choice as the film’s director. A retrospective article on Den of Geek! gives this account:

The studio’s choices included Guillermo del Toro, who baulked at how the film was “so bright and happy and full of light”, and Marc Forster, who didn’t want to direct children again so soon after making Finding Neverland.

It came down to a final short-list of Kenneth Branagh (who had co-starred in the previous instalment as Gilderoy Lockhart), Alfonso Cuarón (A Little Princess) and Callie Khouri (Divine Secrets Of The Ya-Ya Sisterhood and screenwriter of Thelma And Louise). Eventually, Cuarón was appointed, and the director is largely credited with energising the series.

Let’s examine some of what Cuarón brought to Harry Potter by looking at his signature device, long takes.

Three long takes and some flashy effects

Unlike in Children of Men, the long takes in Prisoner of Azkaban are not used primarily for action scenes. Unlike in more conventional Hollywood films, they are not used at the opening as a flashy way of presenting exposition. Rather, they function to emphasize transitional points in the plot and to create motivic parallels. Not surprisingly for Cuarón, all involve camera movements. Two of the three involve conversations, one with an impressive but not flashy tracking movement to follow the characters, the other with a more subtle, slow push-in and out.

The first and lengthiest of the long takes comes in the Leaky Cauldron inn when Harry encounters the Weasley family and Mr. Weasley takes him aside to warn him about Sirius Black’s escape from Azkaban prison. It lasts for one minute and 53 seconds.

The setting is bustling, and the camera movement serves in part to gradually pull attention away from the crowded dining room and to focus on the conversation. The shot opens on the busy table, with a large tea kettle floating on its own through the air. (In Prisoner of Azkaban, Cuarón frequently uses this tactic of having objects floating in the foreground to suggest a magical environment; he will repeat the device in Gravity to depict weightlessness in space). Mrs. Weasley effusively greets Harry:

Mr. Weasley asks to have a word with the boy, and they move toward a squared-off opening near the back of the set. A wanted poster for Black, visible to the right of center from the opening of the shot, becomes more prominent at the frame edge. Since photographs in this magical world move, we cannot help but notice it:

The camera tracks past the poster through a second opening closer to the camera and stops once the characters are centered. Mr. Weasley tells Harry about Black, and the camera moves back to accommodate them when they come forward to look at the poster:

As they continue to talk, the camera again moves backward as Mr. Weasley steers Harry to a third opening into the main dining room. They pause beside a second poster of Black, and Mr. Weasley explains that Black had betrayed Harry’s parents to Voldemort, who had killed them and tried to kill him. As a man in a bowler sits at the table near them, Mr. Weasley again guides Harry into a more private area:

He says Black is going to try and kill Harry and urges Harry not to go looking for him. The shot ends on a push in toward Harry, who replies, “Mr. Weasley, why would I go looking for someone who wants to kill me?” and the scene ends.

This moment marks a crucial change in the narrative tone. The film started with two comic scenes: Harry’s use of magic to inflate his obnoxious Aunt Marge into a human blimp and then the antics of the fantastical Knight Bus that rescues Harry and transports him to the Leaky Cauldron. Now for the first time the theme of grave danger is introduced, with the insane-looking Black screaming silently in the wanted poster. A darker storyline takes over, though there are many moments of humor to come. This conversation leads into the scene on the train to Hogwarts, which, for the first time in the series, has a heavy rainfall occurring throughout. During this scene the first Dementor appears, and Lupin explains what Dementors are.

The second long take (one minute and thirty seconds) comes in a much quieter scene at Hogwarts. Harry has been unable to accompany the other students on a day’s outing to Hogsmeade, the local village, and he is depressed and lonely. He has a conversation with Lupin, set on a long elevated bridge that was added to the Hogwarts setting for this film. The scene begins with an extreme long shot tracking slowly toward the bridge as Harry discusses his fear of Dementors with Lupin, followed by a cut-in to them:

The camera moves in slowly as Lupin turns away and recalls his friendship with Harry’s mother. As he says, “Well, your father James, on the other hand, he … he had a certain, shall we say, talent for trouble,” Harry smiles:

Lupin walks back to Harry, concluding, “A talent, rumor has it, he passed on to you. You’re more like them than you know, Harry. In time you’ll come to see just how much”:

The scene ends with a cut to a shot of the bridge from the original distant framing:

The two scenes are parallel but contrasting, as Harry receives information from two father figures. Initially he speaks to Mr. Weasley, the head of a large, boisterous family that has semi-adopted Harry; we are reminded of them (including Ginny, whom Harry will eventually marry) at intervals in the background of the Leaky Cauldron long take. The two rooms are divided by a series of square openings in a thick wall, which the pair move through as Mr. Weasley prepares to deliver threatening news. The melancholy Lupin, on the other hand, has no family, and here he comforts Harry in a setting with airy, intricate archways framing a vast, empty mountain vista beyond. The quiet atmosphere is appropriate, since Lupin is the first of three classmates and close friends of his dead parents that Harry meets in this film.

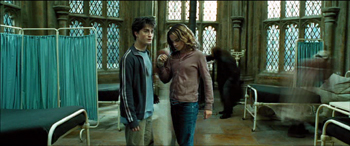

The film’s third long take is the only one that could be said to involve an action scene, though it is really just the prelude to a lengthy segment of the film stringing together several brief action scenes. (It is the shortest of the three long takes, at one minute and eight seconds.) This shot marks another transition, introducing the film’s climax. Everything has just gone wrong. Gamekeeper Hagrid’s pet hippogriff Buckbeak has been executed as too dangerous to be around the students. Sirius, whom the children now know to be innocent of the crime for which he was imprisoned, has been captured and is about to be turned over to the Dementors. Pettigrew, having been revealed as the true traitor to Harry’s parents, has escaped in rat form. In the hospital dormitory where Ron has ended up, Dumbledore hints that Hermione should use the time-turner so that she and Harry can return to the beginning of these events and try to reverse them.

The camera circles around Hermione as she turns away from Ron’s bed and pulls the time-turner on its chain from inside her jacket. She lifts it and places the chain around Harry’s neck, so that they are both wearing it:

He looks on uncomprehendingly as she twirls the time-turner to send them back to a point shortly before the scheduled execution of Buckbeak:

Startled, Harry watches rapid changes in lighting and blurred figures moving backward in fast motion as Hermione keeps track of how far they have traveled. During all this, Ron disappears from the bed at the right rear:

The camera moves in as she hides the time-turner and circles as they run out of the room:

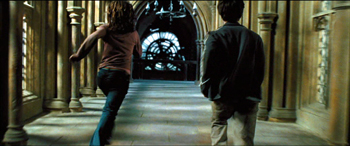

They run along a corridor, the camera following until they turn and exit left:

The camera continues straight ahead, through the large clock wheels, and reveals the school grounds far below:

The camera moves through the glass of the clock window and tilts down to the courtyard, where Hermione and Harry emerge and run out through the doorway at the top of the screen:

Later, after the pair has accomplished their goals, a somewhat similar shot moves with them through this same courtyard and cranes up and through the clock again, joining them at the same point as they run in and away down the corridor to the hospital wing.

On a more modest scale, there is a somewhat similar technique used in Y tu mamá también. The heroine, Luisa, waits in her apartment for Tenoch and Julio to pick her up for a trip to the beach. Once they call to let her know they have arrived, she exits through the front door; the camera tracks rightward to a window and tilts down to reveal the car waiting below and pulling away from the curb as the three depart. Although not a particularly lengthy shot, it functions, as in the third one from Prisoner of Azkaban, to mark a narrative transition, in this case the end of the film’s first portion and move into the long car trip that will occupy most of the rest of the film:

This is a far simpler shot and was accomplished by moving the handheld camera through the room to an open window, sticking it through, and tilting down. The Prisoner of Azkaban “shot” was in fact an elaborate manipulation of images, with the segment where time runs in reverse around Harry and Hermione shot against a green screen; the portion going through the clock’s works and its window was done with CGI elements. (See American Cinematographer‘s article on the film for an explication of the technology involved.)

Admirers of the elaborate “camera movements” in Children of Men and Gravity, some of which were done by stitching together several elements into apparently continuous shots, might take note that Cuarón’s experiences on Prisoner of Azkaban made them possible. A 2006 interview on SFGate describes the director’s progress:

One benefit was a crash course in computer-generated visual effects. Cuarón used “maybe a shot or two in “Y Tu Mamá También”–the 2001 Mexican indie that got him an Oscar nomination for best original screenplay–and in his earlier Hollywood movies, “A Little Princess” and “Great Expectations.”

On the Harry Potter sequel, working with computer effects was “like speaking Russian,” he says. The hardest part was figuring out how to shoot an object such as a plate, knowing that later it would be substituted by some wild effect.

“The important thing was not to be shackled by these effects, to shoot as you would your normal scene. There’s a tendency I witness in movies and completely dislike in which the narrative is kind of forced because of the visual effects. You have to try to keep your character and the visual-effect character as separate as possible.”

By the time he started “Children of Men,” all of this was “like second nature.”

In a more recent (undated) interview given at the time when Gravity‘s principal photography was beginning, Cuarón stressed its connection to the things he had learned about special effects on Prisoner of Azkaban: “Well, Potter was my kindergarten and grammar school and high school and college education of visual effects. It is coming in handy with Gravity which is so, so visual-effects savvy [that] we’re inventing new technologies. Now it’s just second nature.” He also mentions that his work with David Heyman, who produced all the Harry Potter films, was what led him to invite Heyman to produce Gravity.

Apart from the CG-compiled long takes, there were effects like the hundreds of candles floating in the air above the great dining hall of Hogwarts (see top) and the living paintings crowding the walls (above left). It seems remarkable that Cuarón’s third film after his modest Mexican sex comedy could draw such high praise from James Cameron, one of the top directors of effects-heavy films, but working on a Harry Potter movie for a couple of years made that possible. And, as the frame below demonstrates, directing Quidditch matches is a good preparation for showing people drifting weightlessly in space.

The quotation from James Udden comes from his article, “Child of the Long Take: Alfonso Cuaron’s film Aesthetics in the Shadow of Globilization,” Style 43, 1 [Spring 2009]: 40. For those with access to a research library, this issue is available on ProQuest and other online archives.