Archive for the 'Directors: Davies' Category

Wisconsin Film Festival: Sometimes a camera movement . . . .

A Quiet Passion (2016).

DB here:

. . . . sums up what has happened and hints at what’s to come.

Seeing Terence Davies’ splendid A Quiet Passion again at our Wisconsin Film Festival brought out several subtleties I hadn’t registered on my first pass last year at Vancouver. Among the things I appreciated was a poignant 360-degree-plus tracking shot in the Dickinsons’ parlor.

This poet’s passion isn’t always so quiet. Davies’ earliest films are notably light on dialogue, but this one contains plenty of talk, both bantering and brutal. Perhaps most surprisingly, the supposedly withdrawn Emily Dickinson engages in snappy and snappish exchanges with friends, family, neighbors, and one awkwardly sincere suitor. All the more striking, then, when Davies halts the talk and gives us a suite of images accompanied by discreet sound effects, music, and voice-over portions of Dickinson verse.

Fairly early in the film, we get a spirited exchange between the censorious Aunt Elizabeth and the Dickinson family. After her indignant reply to their mock-heathen teasing, she gulps down some currant wine. Next we see the family quietly sharing an evening. That’s when we get this ripe circular camera movement.

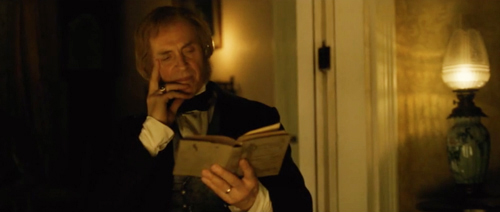

It starts framing Emily, reading by firelight. She looks left.

As the camera coasts past Emily we get a glimpse of a fond smile. The moving frame reveals Aunt Elizabeth, struggling to keep her eyes open.

In the course of this movement, over the soft crackling of the fire and a ticking clock, we hear the older Emily’s voice-over reciting.

The heart asks pleasure first,/ And then, excuse from pain;/ And then, those little anodynes/ That deaden suffering.

The poem is a famously puzzling one. Is the speaker suggesting a bargain–if not pleasure, then no pain, please? Or is it a description of the course of a life: youth seeking pleasure, old age willing to accept absence of pain, and in the end a plea for something that simply ends suffering? The juxtaposition of young Emily and aged Elizabeth suggests two phases of woman’s life: Is Emily still pledged to pleasure (of a bookish kind) while her aunt is already seeking an anodyne, like the brandy she greedily gulped and the sleep that seems to be stealing over her?

As the camera passes Aunt Elizabeth, the poem is completed.

And then, to go to sleep;/ And then, if it should be/ The will of its Inquisitor,/ The liberty to die.

Elizabeth’s drowsiness comes to prefigure the death that will haunt the rest of the film. And the poem’s grim acceptance of physical decline, lifted by the mercies of death, sketches what will be all too vivid in scenes to come.

The camera continues its leftward survey of the family circle, settling next on Emily’s father Edward. He’s thoughtfully reading. So is brother Austin, at the rear table. Sister Vinnie, though, is sewing at the same table.

This survey of the immediate family shows Emily, like the men, gone all literary, while good-hearted Vinnie does no reading, instead attending to women’s tasks. The shot identifies Emily as, if not unfeminine by the standards of the day, at least not sunk in domesticity. She may be searching for that literary spark she will so often identify with glimpses of Eternity.

The view of Edward has been accompanied by clock chimes, and under the image of Austin and Vinnie we hear the clock start to strike the hour of nine. As the camera moves leftward, we see the mother, Emily Norcross Dickinson.

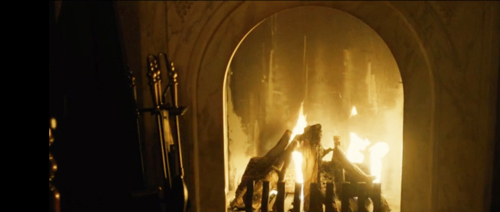

Neither reading nor tending to domestic tasks, Mrs. Dickinson is staring raptly into the fire. Everyone is in a kind of reverie, but hers is inward and melancholy. In the previous scene she has told Aunt Elizabeth “I prefer to listen and remain silent.” Later in the film we’ll learn that she has gradually withdrawn from the family, as if feeling ill-adjusted to these intellectuals, or through some private unhappiness. Later in the scene we’ll get another hint, but after briefly lingering on her, now the camera moves to the fire and then passes beyond.

The piano will be the site of a crucial conflict to come, and the wine decanter, already featured in the scene before, will later be one index of the self-righteousness of the new clergyman’s wife. This “empty” stretch becomes a caesura before we get to the simple, devastating final image of the shot.

So much for books. Emily’s plaintive look, not clearly fastened on any family member, is ambivalent. Has the camera traced her eyes around the family circle, as her sidewise smile at Aunt Elizabeth suggested earlier? If so, what has moved her? Her mother’s solitude? Her siblings’ and fathers’ obliviousness to the older woman? Or is it something more self-centered? Locked within the family circle, has she surveyed the perimeter of her life to come?

The question is partly, teasingly answered, when we hear the offscreen voice of Mrs. Dickinson. She asks Emily to play one of the old hymns. Emily rises and goes to the piano, and we get a cut to the shot surmounting today’s blog entry. After Emily starts playing, the rest of the family is forgotten, and Davies cuts to a closer view of her mother.

Still staring into the fire, she speaks of hearing the hymn sung by a young man with a beautiful voice. He was only nineteen when he died, she tells us, or maybe just herself. The softly delivered memory carries more than mere nostalgia. Are the others even noticing? We never find out.

Unlike her husband and children and Aunt Elizabeth, the mother ponders the past and its losses. We’re invited to imagine an alternative life for her, perhaps with the beautiful young man. Is he kin to the young woman in white with the parasol recalled by Bernstein in Citizen Kane, as he stands before his roaring fire? At the least, this warm parlor is now haunted by death.

Davies is too tactful to push this moment, leaving the character to keep her own counsel. But I can’t resist another probe. The Magnificent Ambersons is one of Terence’s favorite films, he told us during his visit (“better than Kane“). It’s not a stretch to let the image of Mrs. Dickinson remind us of the somber shot of Major Amberson before another fireplace. Deprived of his fortune, baffled by all around him, he ponders the origins of life as the narrator muses that even an Amberson might not get a leg up in the Hereafter.

Terence pointed out to us that the great American films are often about families, because in that setting passions are both aroused and contained. The Dickinson family, tightly bonded by love and respect, ruled by a tender but iron-willed patriarch, harboring a mother and daughter withdrawn from the world, split by failed marriages and angry reproaches, prey to death and broken pledges, is no perfect haven. Perhaps Emily’s stabbing epiphany is a realization of all of that, and what it might mean for her art. All this takes two minutes and ten seconds.

Nowadays the circling camera is a cliché; characters sitting around a table or even just standing in the street seem to be spinning on a turntable. Davies is far more discreet and precise. Step lightly on this narrow spot, a Dickinson poem advises us, and that’s what his camera has done here.

Thanks to Bianca Costello and Music Box Films, which is distributing A Quiet Passion. Its US rollout starts 14 April. Thanks as ever to the Wisconsin Film Festival and its plucky programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser.

And many thanks to Terence Davies for coming to town and providing fine conversation about George Butterworth, Meet Me in St. Louis, and the making of A Quiet Passion. As he told our audience: “I hope you enjoy it, and if you don’t, complain to Mr. Trump.”

Other entries in the intermittent Sometimes. . . . series are here (I Topi Grigi), here (The Mormon’s Victim), here (A Touch of Zen), here (Side Street), and here (Frisco Sally Levy).

Kristin and Terence Davies.

Poets’ summer: PATERSON, A QUIET PASSION

A Quiet Passion (Terence Davies, 2016).

So I write—Poets—All—

Their Summer—lasts a Solid Year—

They can afford a Sun

The East—would deem extravagant—

Emily Dickinson, “I Reckon–when I count it all,” no. 569

DB here:

From the Vancouver International Film Festival, I write on two new films you should see as soon as you can.

How to make a film respecting the power of poetry? More basically: What is that power? Does it lie in the fact that poetry can be a part of ordinary life? This seems to me the angle taken in Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson. Or does poetry’s power arise as an alternative to mundane intercourse, a realm in which we test thoughts and feelings beyond the flow of daily life? I think this is the angle taken in Terence Davies’ A Quiet Passion.

The secret notebook

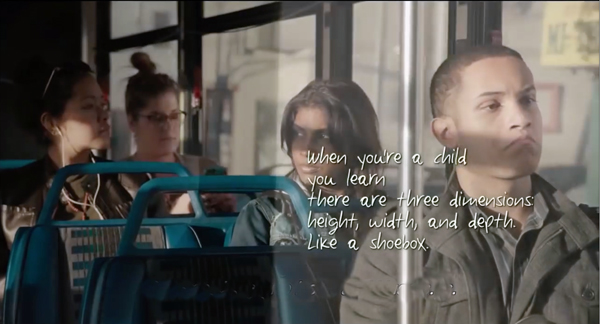

Paterson drives a bus in Paterson. The bus’s destination display bears not a street name but rather the word “Paterson.” Such playful quirks, long a part of the American indie game, is as inoffensive as the film’s title (Paterson, of course). The milieu looks prosaic enough, with quasi-documentary shots of streets and the Great Falls. But Paterson owns a bungalow on a bus-driver’s salary, catches a 1930s horror film at a local theatre, and drops in at a saloon where a barkeep named Doc plays chess with himself. The town has more than its share of twins too.

In this slightly off-track version of a city, the protagonist’s Iranian-American wife Laura paints fabrics, bakes designer cupcakes, and wants to be a country singer. Meanwhile, Paterson has creative impulses of his own. He writes poetry.

Paterson is a quiet, genial fellow to whom you’d happily entrust your morning commute. His poems (written by New York School poet Ron Padgett) are conversational; the first one we hear begins: “We have plenty of matches in our house.” The poems are given their force by their homely details and the repetition of simple declarative phrases.

Repetition is built into the film’s block construction: A Week in the Life. Waking up, having breakfast, walking to the bus terminal, jotting down some verse before beginning his routes, lunch and more jotting, walking home, eating dinner, and visiting the bar—Paterson ‘s routines create a rhythmic matrix that we quickly learn. That the film’s structure is built around work routines makes sense. In America, a poet might be your bus driver, your doctor (William Carlos Williams), your insurance executive (Wallace Stevens), the farmer down the road (Robert Frost), or your teacher in business school (Marianne Moore).

As for poetic texture, the routines get treated in small-scale variations. Take the opening bed shot, an overhead view of the couple that announces a new day. One morning Laura isn’t there. Sometimes we don’t get a shot of Paterson checking his wristwatch. The weekend mornings lack the daily written title that the workdays get. A poetic principle of verse and refrain gets built into the film’s structure.

Finer-grain texture comes in the recitation of the verses as Paterson writes them into his scruffy notebook. We see the lines form on the surface of the screen, in freehand script, while montages of driving surge underneath them–as if these were coming to life in the course of the day. The fate of the secret notebook is probably the biggest dramatic twist in the film, but even that becomes part of a larger pattern after a melancholy Sunday walk.

And drama? There are moments of tension. Paterson is unenthusiastic about Laura’s buying a guitar, and an habitué of the bar seems to create a life-or-death crisis. Yet these and other problems slide away quickly. When Saturday night comes around, a kind of climax occurs. It tails off, subsumed in the playing out of motifs that were installed early on—rhymes, we might say.

As you’d expect in a film living under the aegis of Williams (author, of course, of Paterson the book of verse), it’s all about the discrimination of detail. “No ideas but in things” is the motto. The emblem becomes the Ohio Blue Tip Matches described in Padgett’s poem and shown to us in close-up. Laura reveals her poetic acumen when she asks if Paterson’s verse mentions the megaphone skew of the label’s lettering.

Paterson may write alongside a waterfall like a classic poet inspired by nature’s sublimity. But in tuning his ear to his passengers’ conversations and by finding epiphanies in mass-manufactured objects, he’s in the American grain.

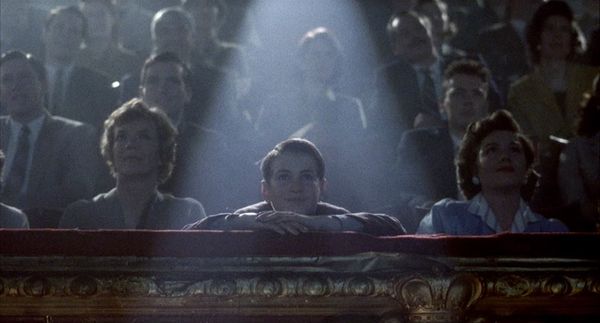

Night thoughts

Paterson is so unassuming in his creativity that his film might have been called A Quiet Passion. That, though, is the title of Terence Davies’ tribute to Emily Dickinson. But not much about her is presented as quiet. The film starts with the tart young Emily declining to accept a place in Mt. Holyoke’s pious “ark of safety.” She prefers the soaring rapture of Bellini’s “Come per me sereno,” a bride’s thank-you to guests at her wedding. While her family listens politely in their concert-theatre box, she sways in sympathy with the singer. The scene seals her pledge to art.

Any biopic of the Belle of Amherst faces the problem of characterizing her through talk and action. One option is to make her meek and introspective. Another is to make her conversation as diffuse, oblique, and staccato as her verse. Davies has boldly tried another tack. He has made her one of a trio of eloquent women who swap epigrams as swiftly as if they were in an opera or an Oscar Wilde play. Davies seems to be suggesting that worldly (and wordy) banter with her kindly sister Lavinia and racier friend Miss Buffam gave Emily a sense of the blunt force of language.

Paterson is laconic and ruminative, like his verses, but Emily is a parlor dialectician. She hammers fierce comebacks at her father, at her brother (especially when he takes a mistress), and even at the devoted Vinnie. What authority she gains in her closed society emerges mostly from her wit and tongue. (Though she can calmly smash a plate too.) At the same time, Emily knows her words can wound. She’s miserable after snapping at the family servants, and after a volatile exchange with Vinnie she despairs of ever being a good person.

Here is a woman who feels the power and pain of language. Once we understand that, we’re better prepared to understand the inward turn of her verse. Unlike her dueling conversations, her poems are skewed and slanted, with unexpected jumps at every line, or dash. They twist nursery-rhyme cadences and simple vocabulary into Donne-like knots of phrasing. The film’s voice-over recitations make the verse even more elusive than on the page, but I don’t know how else Davies could have handled them. Even showing the lines as they emerge, as Paterson does with superimposed writing, wouldn’t fully satisfy. We need time to ponder the impacted syntax on display. I suspect that instead of trying to translate the perplexing force of Dickinson’s verse, Davies’ film exists as a parallel text, a supplement urging viewers to return to the poems after witnessing Emily’s socializing and suffering.

Familiar Davies themes emerge. Fiery spirituality clashes with hypocritical churchifying; family ties are fulfilling but also suffocating; a single room can enclose peace or stabbing pain. There’s the power of women’s friendships, alliances against a world bent on cutting them down. Davies reminds us that “women’s art” often involves handicraft. Emily is not only writer but book-maker, trimming and stitching little pages together into secular devotionals. These mini-books recall and mock those pious guides for meditation that could be tucked into purses and waistcoats.

Paterson writes in the daytime, while waiting to pull the bus out of the garage or on his lunch hour or even while driving. Emily, once her father gives his permission, writes from 3 AM into the morning. Accordingly, the bus driver’s poems, like those of Williams, have the evenly-lit clarity, if not the compression, of a haiku, while Emily’s verses, haltingly phrased, move in a hallucinatory blur. Jarmusch’s no-fuss staging and editing suit the unassertive texture of the verse and the driver’s days, while Davies, himself something of a chamber artist and a master of the musicalized image, scans his parlor tableaux with lush gravity.

Two films, each one both light and grave, adroit and solemn, though in different registers. Whatever cinematic poetry is, they aspire to it.

Michael Koresky has a superb discussion of Paterson at Reverse Shot, the Museum of the Moving Image site.

Note for the theoretically inclined: Paterson‘s structured routines and substitution-slots interestingly conform to Roman Jakobson’s dictum that the poetic function consists of the projection of the paradigmatic axis of language (alternative lexical items) onto the syntagmatic axis (the linear flow) of a text. See his “Closing Statement: Linguistics and Poetics.”

Another entry on this site considers Davies’ Sunset Song and his other films. As Moonrise Kingdom is one of our blog’s favorite recent films, it’s a pleasure to glimpse Jared Gilman and Kara Hayward as kids bringing anarchy to Paterson, N. J.

Paterson (Jim Jarmusch, 2016).

Terence Davies: Sunset songs

Sunset Song (2015).

DB here:

A career retrospective brought director Terence Davies to Astoria’s always enterprising Museum of the Moving Image. On Sunday MoMI ran a handsome 35mm copy of The Long Day Closes (1992), introduced by Sony Pictures Classics Co-President Michael Barker (who originally distributed the movie). The film was followed by Davies’ informative discussion with Michael Koresky, author of a fine critical study of Davies. On Tuesday, there was an avant-premiere of Sunset Song (2015) with Agyness Deyn, the principal player, joining Davies and Koresky. The first screening featured one of the greatest films of the 1990s, while the second showcased the literary adaptation that Davies had sought to make for several years.

The two evenings left me with renewed respect for the power of this audiovisual art we call cinema. They also set me thinking about Davies’ unique contributions to that art, particularly in his first two features.

MGM in Liverpool

The Long Day Closes.

If you needed proof of the unpredictable, zigzag influence of Hollywood cinema, look no farther than the films of Terence Davies. When he saw his first film, Singin’ in the Rain (1952), he knew utter rapture, and his early years were illuminated by visits to the local movie house. But unlike other cinephile directors, he didn’t turn retro. His first two masterpieces, Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988) and The Long Day Closes (1992), decant the splendors of American musicals into vessels more severe and melancholy. The brooding lyricism of these films, presented in a stringently geometrical pictorial style, makes them almost unrecognizable cousins of the 1950s films that nourished him.

Davies understood, as so many postwar critics of mass culture didn’t, that Hollywood, for all its formulas and conventions, captured genuine feeling; indeed, those very formulas and conventions released that feeling. In Davies’ hands, however, the feelings gain a rougher texture. In tales of patriarchal power and everyday betrayals, echoes of the yearning of Judy Garland and the vibrato of Doris Day seem distant and distorted. Davies finds the evanescence hidden in Yankee exuberance, and he takes it very personally.

That’s partly because popular song is filtered through a sensibility deeply committed to classical musical expression. Nobody but Davies would accompany an image of urban squalor with the arching final melody of Vaughan Williams’ Pastoral symphony, or the soft run of George Butterworth’s “Shropshire Lad” tune over the tan rug in The Long Day Closes. The soaring Barber violin concerto accompanies, for an astonishing eleven minutes, the opening images of The Deep Blue Sea (2011); it’s practically a cinematic tone poem. One of those directors who’s unthinkable outside the sound cinema, Davies dissolves any barrier between popular song and art music. The American Song Book, he says, is the country’s greatest gift to the world, and Stephen Sondheim is our Schubert.

Music is tied, in intricate ways, to family. These films are openly autobiographical. The first part of Distant Voices is a terrifying portrait of domestic life with a madman; the second part treats the radiant moments without him. The father is absent in The Long Day Closes, and so life in the household, with Mum and brothers and sister and visiting chums, is blissful. (Surely Davies is the great filmmaker of sibling devotion.) Now the threat lies beyond the threshold; school bullies, sadistic teachers, and a Church that seems indifferent to the suffering of a boy vaguely sensing his homosexuality.

Yet by a kind of benevolent contagion, the joy of American cinema transfigures the grubby side of daily life–through communal singsongs in parlor or pub, through impromptu performances at parties, through hit-parade tunes hummed during daily routines. There are line-readings too; in The Long Day Closes the Boccherini minuet from the ball in The Magnificent Ambersons is matched by quick borrowings from Welles’ voice-over narrator. In one of the great sequences of modern cinema, a survey of the boy Bud’s world is shot from straight-down framings that roll by like scenes in a picture scroll. Birds’-eye views of street, cinema, church, and school are wrapped in the throbbing voice of Debbie Reynolds singing “Tammy.”

Cinema wins on the soundtrack. Take away the music and the snippet from Kind Hearts and Coronets and you have a grim topography. With movies, life’s miseries become bearable.

Chamber pieces

Distant Voices, Still Lives.

Distant Voices and The Long Day Closes balance social realism with a first-person quality shot through with feeling. Davies remembers everything about his childhood, and he can present unsentimentally the gray-brown wallpaper and the bulky furnishings. (He remarked that period films always forget that people didn’t have the most up-to-date things; nobody in 1950 Liverpool owned 1950 furniture.) Even realistic detail is saturated with memory and expression. Similarly, Davies’ reliance on planimetric shooting, dominant in Distant Voices and still strong in The Long Day Closes, creates at once rigid formality and a curious intimacy, as if we were looking at family portraits.

When capturing moments of serenity, the perpendicular shots evoke utter honesty; characters face us frankly, hiding nothing. But confronted with a schoolyard beating or a psychopath thrashing his wife, this curiously impassive camera–no wild handheld bursts or jagged cutting–only accentuates the pain. The camera’s unearthly calm takes on a kind of ruthlessness, as if nothing awful that happens in this world can make it flinch, just as nothing rapturous can make it go giddy. Davies seems fairly Wordsworthian: his poetry is “a spontaneous overflow of powerful feeling,” but the overflow is “recollected in tranquility.” The scene’s situation and the music, we might say, supply the feeling, while the framing supplies the tranquility and suggests the distance of memory.

These tableaus remind us that Davies is one of the few masters of cinematic chamber art. The exteriors, very few in these two features, are treated in the same rectilinear framings as the rooms are, as if one could never escape the carpentered contours of a house. More often, we’re indoors, and the human figures in are caught, nearly frozen, in a parlor or kitchen or hallway or schoolroom. No wonder his favorite painter is Vermeer.

Like Dreyer, Davies finds drama in the nearly closed room, the space slashed by light and opening onto somewhere else: in Davies’ case the doorway and the stoop and the street. These are the little theatres of human relaxation, of sharing, good times, and of course song. All the more jolting, then, when the father in Distant Voices turns up at the door, released from the hospital, or when Bud in The Long Day Closes sees his pal Albie go off to the pictures without him. As Michael Koresky notes in his book, the face at the windowpane looking out at the world is a recurring image for Davies: the edge between two arenas of experience, both harboring pain and exaltation.

Davies is famous for laying out each film with a draftsman’s precision: shot by shot, line by line, musical extract by musical extract. These films are absolutely through-composed. Their strict rhymes channel the feelings of the characters–or rather, the feeling of a scene as a whole–into determinate shapes that we can grasp. The sound is as important as the images; Hollywood musicals taught him the tight coordination of image and phrasing that pattern his song sequences and pictorial cadenzas.

Davies is famous for laying out each film with a draftsman’s precision: shot by shot, line by line, musical extract by musical extract. These films are absolutely through-composed. Their strict rhymes channel the feelings of the characters–or rather, the feeling of a scene as a whole–into determinate shapes that we can grasp. The sound is as important as the images; Hollywood musicals taught him the tight coordination of image and phrasing that pattern his song sequences and pictorial cadenzas.

No surprise, then, that Davies loves music and poetry, to which he constantly compares cinema. And no wonder he admires T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, that poem that takes its title from chamber music. In both music and verse, powerful feelings flow through rigorous forms. The chock-a-block construction of Distant Voices sets up poetic parallels and contrasts between the two parts. More boldly, The Long Day Closes offers a narrative that’s barely there: a suite of situations, a flow of anecdotes that gathers symphonic force. It recalls Pather Panchali and other films about a child coming to understand that whatever happens, painful or exhilarating, is transitory when seen against the backdrop of eternity.

Davies is after, he said in conversation, “the intensity of the moment,” and what happens before or after may seem of little account. Sound, light, color, movement: all become focused on the poignancy of the felt instant. Yet in another echo of Romanticism, that instant isn’t trivial when it’s seen in a cosmic context. Left alone by his brothers and sister, Bud thrusts his flashlight to the sky, creating a movie-projector’s beam as a demonstration that light goes on forever.

In an echo of this moment, Bud’s long days close with a merger of the momentary and the infinite. Two boys sit (in the balcony?) poised against the sky. Their movie becomes a majestic sunset, wrapped in the plangent song that gives the film its title. The light from the stars dates from Jesus’ day, Bud tells Albie, as the sacred chambers of his world open onto the universe.

Daughter of the earth

Terence Davies and Agyness Deyn.

A sadistic, baleful father; a mother bearing the brunt of his demands; a brother and sister as tender with one another as sweethearts; gentle friends who sustain the household with music–with Sunset Song we seem to be back in the world of Davies’ early films. But instead of the grubby city streets we’re in a glorious green-gold landscape of rolling fields, and instead of postwar London we’re in Scotland on the eve of World War I.

Sunset Song, drawn from the 1932 novel by Lewis Grassic Gibbon, exemplifies Davies’ later interest in adapting literary works (The Neon Bible, 1995; The House of Mirth, 2000; The Deep Blue Sea). In all of these, Davies tries to respect the spirit of the original while finding affinities with his own sensibility.

Sunset Song centers on Chris Guthrie, the dutiful daughter of a farm household. For the early stretches of the film she’s a cautious observer, but her voice-over, presented in the third person and past tense, prepares for her to take over the action. At first she’s inclined to run away with her brother, but duty keeps her home. When she comes into ownership of the farm, she realizes that she is rooted in the place. The earth, more eternally solid than sea or sky, gives her strength. If she cannot forgive what her father has done, she can learn to understand and forgive another man’s betrayal.

At first glance, we might seem to be snugly settled in British Cinema of Quality. But Davies has always made “costume pictures,” and his take isn’t in tune with Masterpiece-Theatre fashion shows. The clothes, as Davies always demands, look lived in, worked in, slept in. Agyness Deyn explained that for wardrobe they gladly took the worn leftovers of tonier productions.

Despite the eye-filling landscapes shot in 65mm, Davies hasn’t played false to his intimate aesthetic; this remains a chamber drama, with few primary characters. Like Bud in The Long Day Closes, Chris is our focal consciousness; apart from a substantial flashback to war-torn France, we’re confined chiefly to what happens around her. A few years of history unfold in a rhythm tuned to her growing awareness of her options and decisions, good and bad.

The style is far more mainstream than in the first two features. We get continuity editing (often in its constructive vein), smooth reframings as actors move around sets, and not many images recalling the tableau-vivant look of the earlier work. Chris is introduced in one of those twirling camera movements that are de rigueur nowadays, though Davies refreshes the convention by the visual metaphor of her rising up from the wheat, as if from sprung from the soil, and tipping her face to the sun, like a flower.

But Davies insisted on both evenings that for him, form springs from content. I take that to mean that the brick-by-brick shot assemblage of the first films suits the episodic, memory-driven nature of those tales. Here we have a novelistic saga (the original book is part of a trilogy), and so we must stay engaged with a chronologically unfolding plot. Davies has opted for less stylization, the better to rivet us to the powerful story of his protagonist’s blossoming to maturity.

Again, music yields a model. He urges young filmmakers to study symphonic cycles, like those of Bruckner and Sibelius, in order to appreciate scale and balance and variety in a large-scale structure. The relaxed flow of Sunset Song–and what power the title must have had for him–is like that of a full-scale orchestral essay. If Distant Voices, with its shifting, decentered viewpoint, is a chamber piece and The Long Day Closes is something like a song cycle for voice and quartet, this latest work is perhaps a concerto, with Chris’s sturdy presence an instrument of commanding range set against the massive landscape and a choir of family, friends, and neighbors.

Normally we must wait years between Davies’ films, but A Quiet Passion, his biography of Emily Dickinson, is beginning its career in worldwide distribution now. One feature in 2015, another in 2016. “I’m in danger of becoming prolific.”

Back in 2001, Kristin and I met Terence and his assistant John Taylor (loyal Packers fan) at Belgium’s summer film college. They were good company then, and still are. The MoMI screenings provided a wonderful occasion to see them and the films once more. If you’re in the vicinity, start queueing now for the follow-up items in the series. And Sunset Song opens this Friday at Film Forum, with Terence present. From there it will make its way across the US. You couldn’t spend your time more fruitfully. These movies will last a very long time.

Thanks to David Schwartz and his colleagues at MoMI. The Long Day Closes is available on DVD and Blu-ray from the Criterion Collection; thanks to Kim Hendrickson for her assistance. And thanks to George Nicholis of Magnolia Pictures, which is releasing Sunset Song.

For more on the stylistic tradition that early Davies films work within, you can consult Chapter Six of On the History of Film Style and these entries.

The Long Day Closes (1992).