Archive for the 'Directors: Disney' Category

Homage to Mme. Edelhaus

Why are Americans polarized between francophobia and francophilia? Some people mock the French for liking Jerry Lewis, when most French people probably don’t even know who he is. Others think that France is the repository of world culture and represents the finest in writing about the arts, even though the Parisian intelligentsia can be pretentious and hermetic.

But we must face facts. When it comes to cinephilia, the French have no equals. They grant film a respect that it wins nowhere else. Spend a year, or even a month, in Paris, and you will feel like a Renaissance prince. This is a city where one lonely screen can run tattered prints of One from the Heart and Hellzapoppin!, once a week, indefinitely.

My first trip was too brief, only a week in 1970, but my second one—four weeks of dissertation research in 1973—left me exhausted. Reading Pariscope on the way in from the airport, I learned about a Tex Avery festival. I checked into my hotel and Métro’d to the theatre, where I and a bunch of moms and kids gazed in rapture upon King-Size Canary. Another time, also coming in from the airport, Kristin and I passed a marquee for King Hu’s Raining in the Mountain. Next stop, Raining in the Mountain. My memories of The Naked Spur, Ministry of Fear, Liebelei, Tati’s Traffic, and Vertov’s Stride Soviet! are inextricable from the Parisian venues in which I saw them.

Sound like a lament for days gone by? Nope. You can find the same variety on offer today. Of course the two monthlies, Cahiers du cinéma and Positif, have to take a lot of credit for this. Add Traffic, Cinéma, and several other ambitious journals, and you get a film culture unrivalled in the world.

Critics from Louis Delluc onward have led thousands of readers toward appreciating the seventh art. Historians like Georges Sadoul, Jean Mitry, Laurent Mannoni, Francis Lacassin, and others have enlightened us for decades. Academic film analysis would not be what it is without Raymond Bellour, Noel Burch, Marie-Claire Ropars, Jacques Aumont, and a host of other scholars. Above all stands André Bazin, the greatest theorist-critic we have had.

And the books! Arts-and-sciences publishing receives government subsidies; the French understand that books contribute to the public good. There are plenty of worse ways to spend tax dollars (e.g., trumped-up military invasions). The French, like the Italians, have created an ardent translation culture too. If you can’t read something in Russian or German, there’s a good chance it’s available in French.

I was reminded of the glories of Gallic film publishing when the mailman tottered to my door this week with twenty-two pounds worth of recent items I’d ordered. I haven’t even read them yet; otherwise, they’d be filed with Book Reports. Instead I want to spend today’s blog celebrating them as fruits of an ambition that has no counterpart in English-language publishing. All are grand and gorgeous and informative to boot.

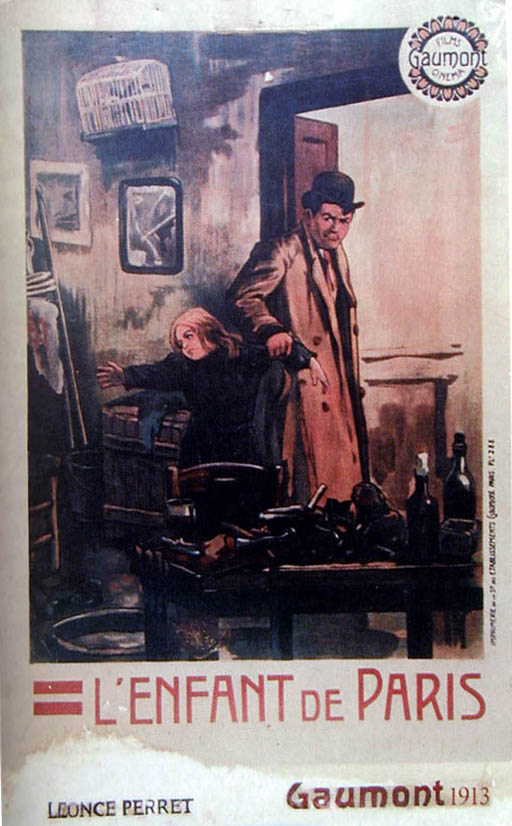

Daniel Taillé, Léonce Perret Cinématographiste. Association Cinémathèque en Deux-Sèvres, 2006. 2.5 lbs.

Daniel Taillé, Léonce Perret Cinématographiste. Association Cinémathèque en Deux-Sèvres, 2006. 2.5 lbs.

A biographical study of a Gaumont director still too little known. Perret was second only to Feuillade at Gaumont, and he performed as a fine comedian as well. His shorts are charming, and his longer works, like L’enfant de Paris (1913), remain remarkable for their complex staging and cutting. After a thriving career in France, Perret came to make films in America, including Twin Pawns (1919), a lively Wilkie Collins adaptation. He returned to France and was directing up to his death in 1935.

Although the text seems a bit cut-and-paste, Taillé has included many lovely posters and letters, along with a detailed filmography, full endnotes, and a vast bibliography. It compares only to that deluxe career survey of the silent films of Raoul Walsh, published by Knopf. . . .Oh, wait, there’s no such book. . . .Think there ever will be?

Il était une fois Walt Disney: Aux sources de l’art des studios Disney. Galéries nationales du Grand Palais, 2006. 4 lbs.

Il était une fois Walt Disney: Aux sources de l’art des studios Disney. Galéries nationales du Grand Palais, 2006. 4 lbs.

A luscious catalogue of an exposition tracing visual sources of Disney’s animation. Illustrated with sketches, concept paintings, and character designs from the Disney archives, this volume shows how much the cartoon studio owed to painting traditions from the Middle Ages onward. It includes articles on the training schools that shaped the studio’s look, on European sources of Disney’s style and iconography, on architecture, on relations with Dalí, and on appropriations by Pop Artists. There’s also a filmography and a valuable biographical dictionary of studio animators.

Some of the affinities seem far-fetched, but after Neil Gabler’s unadventurous biography, a little stretching is welcome. This exhibition (headed to Montreal next month) answers my hopes for serious treatment of the pictorial ambitions of the world’s most powerful cartoon factory. The catalogue is about to appear in English–from a German publisher.

Jean-Pierre Berthomé and François Thomas. Orson Welles au travail. Cahiers du cinéma, 2006. 4 lbs.

Jean-Pierre Berthomé and François Thomas. Orson Welles au travail. Cahiers du cinéma, 2006. 4 lbs.

The authors of a lengthy study of Citizen Kane now take us through the production process of each of Welles’ works. They have stuffed their book with script excerpts, storyboards, charts, timelines, and uncommon production stills.

The text, on my cursory sampling, will seem largely familiar to Welles aficionados; the frames from the actual films betray their DVD origins; and I would like to have seen more depth on certain stylistic matters. (The authors’ account of the pre-Kane Hollywood style, for instance, is oversimplified.) Yet the sheer luxury of the presentation overwhelms my reservations. A colossal filmmaker, in several senses, deserves a colossal book like this.

Alain Bergala. Godard au travail: Les années 60. Cahiers du cinéma. 2006. 5 lbs.

Alain Bergala. Godard au travail: Les années 60. Cahiers du cinéma. 2006. 5 lbs.

In the same series as the Welles volume, even more imposing. If you want to know the shooting schedule for Alphaville or check the retake report for La Chinoise (these are eminently reasonable desires), here is the place to look. Detailed background on the production of every 1960s Godard movie, with many discussions of the creative choices at each stage. Once more, stunningly mounted, with lots of color to show off posters and production stills.

Anybody who thinks that Godard just made it up as he went along will be surprised to find a great degree of detailed planning. (After all, the guy is Swiss.) Yet the scripts leave plenty of room to wiggle. “The first shot of this sequence,” begins one scene of the Contempt screenplay, “is also the last shot of the previous sequence.” Soon we learn that “This sequence will last around 20-30 minutes. It’s difficult to recount what happens exactly and chronologically.”

Emrik Gouneau and Léonard Amara. Encyclopédie du cinéma du Hong Kong. Les Belles Lettres, 2006. 6.5 lbs.

Emrik Gouneau and Léonard Amara. Encyclopédie du cinéma du Hong Kong. Les Belles Lettres, 2006. 6.5 lbs.

The avoirdupois champ of my batch. The French were early admirers of modern Hong Kong cinema, but their reference works lagged behind those of Italy, Germany, and the US. (Most notable of the last is John Charles’ Hong Kong Filmography, 1977-1997.) More recently the French have weighed in, literally. 2005 gave us Christophe Genet’s Encyclopédie du cinéma d’arts martiaux, a substantial (2 lbs.) list of films and personalities, with plots, credits, and French release dates.

Newer and niftier, the Gouneau/ Amara volume covers much more than martial arts, and so it strikes my tabletop like a Shaolin monk’s fist. There are lovely posters in color and plenty of photos of actors that help you identify recurring bit players. Yet this is more than a pretty coffee-table book. It offers genre analysis, history, critical commentary, biographical entries, surveys of music, comments on television production, and much more. It has abbreviated lists of terms and top box-office titles, as well as a surprisingly detailed chronology.

Above all—and worth the 62-euro price tag in itself—the volume provides a chronological list of all domestically made films released in the colony from 1913 to 2006! Running to over 200 big-format pages, the list enters films by their English titles and it indicates language (Mandarin, Cantonese, or other), release date, director, genre, and major stars. Until the Hong Kong Film Archive completes its vast filmography of local productions, this will remain indispensable for all researchers.

Above all—and worth the 62-euro price tag in itself—the volume provides a chronological list of all domestically made films released in the colony from 1913 to 2006! Running to over 200 big-format pages, the list enters films by their English titles and it indicates language (Mandarin, Cantonese, or other), release date, director, genre, and major stars. Until the Hong Kong Film Archive completes its vast filmography of local productions, this will remain indispensable for all researchers.

Mme. Edelhaus was my high school French teacher. A stout lady always in a black dress, she looked like the dowager at the piano during the danse macabre of Rules of the Game. She was mysterious. She occasionally let slip what it was like to live under Nazi occupation, telling us how German soldiers seeded parks and playgrounds with explosives before they left Paris. When I asked her what avant-garde meant, she replied that it was the artistic force that led into unknown regions and invited others to follow–pause–“in the unlikely event that they will choose to do so.”

For three years Mme. Edelhaus suffered my execrable pronunciation. When I tried to make light of my bungling, she would ask, “Dah-veed, why must you always play the fool?”

I suppose I’m still at it. But thanks largely to her I’m able to read these books as well as look at them. She opened a path that’s still providing me vistas onto the splendors of cinema.

Uncle Walt the artist

From Robert Benayoun, Le Dessin animé après Walt Disney.

The epos of Chaplin is the Paradise Lost of today. The epos of Disney is Paradise Regained.

Sergei Eisenstein

DB here:

I’m not qualified to write a comprehensive or penetrating review of Neal Gabler’s biography Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. For that you can go to Mike Barrier, one of our finest historians of US animation. Barrier’s own Disney biography will come out this spring, with apparently little overlap with Gabler’s.

I’m not qualified to write a comprehensive or penetrating review of Neal Gabler’s biography Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. For that you can go to Mike Barrier, one of our finest historians of US animation. Barrier’s own Disney biography will come out this spring, with apparently little overlap with Gabler’s.

I found Gabler’s book a thorough, somewhat cautious bio, even-handed about Disney and judicious about such controversial matters as Walt’s reputation as an anti-Semite. A lot of it reads like a notecard book, with quotes, paraphrases, and commentary dutifully snipped and pasted in, packing each paragraph. Chronology, not concept, rules. Still, I learned a lot.

Gabler’s book reminded me how much I admire Disney films. The attachment started–as for most of us–in childhood. Peter Pan (1953) was the first one I remember seeing in a theatre, but when I saw a reissue of Snow White later, parts looked so familiar that it must have impressed itself on me at an earlier time. Of course it still scared the hell out of me.

In 1973, when I was doing dissertation research in New York City, I attended a massive Disney retrospective at MoMA. As a twenty-five-year-old bearded guy among moms and kids, I felt obscurely criminal just being there, like a character in a Patricia Highsmith novel. But what I saw, in excellent prints, showed me that Disney was important on both cultural and artistic levels. So I designed a Disney unit into my first Introduction to Film course, taught here at University of Wisconsin–Madison to 300-400 souls whom fate cast my way.

I wanted to talk about film’s relation to society, and Disney was a touchstone for all my students. No matter where they came from, they knew Mickey, Donald, Snow White, Fantasia, and the rest. I showed early films, like Flowers and Trees, The Band Concert, and The Old Mill, as well as a True-Life Adventure nature doc, and the extraordinary Trip through the Disney Studio which was originally attached to The Reluctant Dragon. Students were able to see, I hope, how the ideology at work in Disney films could shape a conception of the world, of American life, and of their childhood.

Our assigned reading was Richard Schickel’s The Disney Version (1969); it’s a coruscating study, perfectly crystallizing that era’s feelings about Disney’s debasement of popular culture. At about the same time, Armand Mattelart’s Marxist critique How to Read Donald Duck was informing most film academics’ study of Disney. As Gabler indicates, intellectuals fell out of love with Disney in the 1940s. He handled labor disputes at the studio in a high-handed, paranoid way. He also seemed to personify the blandness of postwar consensus culture, and Disneyland became the theme-park equivalent of Norman Rockwell Americana. Even though hippies were turning on to re-releases of Alice in Wonderland and Fantasia, most cultural critics treated Disney pretty roughly. My friends and I goggled at Wally Wood’s 1967 Realist cartoon showing Walt’s whole gang engaging in a panoply of naughty sexual encounters.

Today the academic study of Disney is well-established, producing far too much for me to keep up with. A lot of it is cultural critique. For something funnier and even more scurrilous, see Carl Hiaasen’s Team Rodent. Despite all there is to read about Walt’s empire and its cultural consequences, I want something else as well.

Even when I was conducting my Disney Demystification Exercise, I tried to point out that these cartoons were artistically very strong. I still admire the powerfully emotional storytelling that, like that found in other fairy tales, preys so mercilessly on childhood fears. Schickel claims that after screenings of Snow White at Radio City Music Hall, the seats had to be cleaned because the Witch had scared kids into emptying their bladders.

Then too there’s the dynamism and grace of the animation, which remains unsurpassed. For Sergei Eisenstein Disney exemplified the contagious power of expressive movement on the screen. Many have disdained “Mickey-Mousing,” the close matchup between a film image and the accompanying music. But Eisenstein saw this as “synchronization of senses,” a primal, visceral unity that could move the spectator involuntarily. He sought this subconscious synchronization in his own sound films, and Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible show the strong influence of Disney.

Eisenstein was well aware of the delusional aspects of Disney, claiming that the cartoons lulled people into forgetting the harm done by capitalism. But as an artist, Disney was unique:

I’m sometimes frightened when I watch his films. Frightened because of some absolute perfection in what he does. This man seems to know not only the magic of all technical means, but also all the most secret strands of human thought, images, ideas, feelings…. He creates somewhere in the realm of the very purest and most primal depths.[1]

Disney’s art seems magical, but if it’s not a miracle, we ought to be able to study it systematically. How?

Felix in Hollywood (1923)

Felix in Hollywood (1923)

For the Jung at heart

Gabler’s is a sturdy, readable volume teeming with fascinating background material. As an EEG of the ups and downs of the studio, it’s extremely valuable. Gabler also aims to give a portrait of Disney the visionary, a man of boundless Protestant energy who sought to take animated film to ever higher levels. I think the portrait is disappointing, though, in its reliance on conventional psychobiography and Zeitgeist explanations.

Disney, Gabler claims, was dominated by a psychological drive to create a world wholly of his own. He was a control freak. “It had always been about control, about crafting a better reality than the one outside the studio, and about demonstrating that one had the capacity to do so. That was what Walt Disney provided to America–not escape, as so many analysts would surmise, but control and the vicarious empowerment that accompanied it.”

Commentators have long noted that Disney expanded the films’ fantasy world in his theme park. Just as films idealized reality, “so would Disneyland, the creation of a wounded man who expunged what he saw as the darker passages of his past by devising a better world of his imagination, though one that was obviously colored by the images of Hollywood.”

One has to wonder whether this characterization is particular to Uncle Walt. Lots of artists, from architects and topiary gardeners to designers of world’s fairs, have sought to create imaginary worlds over which they rule. Balzac, Faulkner, Lewis Carroll, and J. R. R. Tolkien conjured up imaginary realms populated by dozens of their own creatures. Graphic artist Ho Che Anderson writes:

For the control freak, there are few places better than comics. . . . Pick up a pen and piece of paper and you too can effectively play God. I suspect this love of God-play is the blood that keeps the hearts of many a cartoonist beating.[2]

Moreover, is the desire to build a parallel world necessarily a sign of a wounded past, or dark imaginings? Maybe it’s just one awesome creative challenge for ambitious artists. Granted, Disney took this impulse in a particular direction, toward a vision of life combining technical progress (the multiplane camera, Tomorrowland) with idealized notions of small-town community. But then we have to explain those idiosyncratic factors too.

Gabler goes the psychological route, but we could balance this account with cultural factors in Disney’s immediate milieu. There was the rise of the Technocracy movement. There was Hollywood’s belief that filmmaking would progress through new technologies. There was growing evidence during and after World War II that America’s might would be built on new machines. (One of the most hair-raising movies I saw at the 1973 MoMA Disney fest was Victory through Air Power, an educational short arguing for investment in airborne warfare.) Disney was, along many dimensions, a techie impresario, the Steve Jobs of his day, complete with his unique reality-distortion field.

The other big-picture explanation Gabler offers is a Zeitgeist model. Disney represents the American imagination. By tapping into Jungian archetypes, his 1930s films could both “capture and then soothe the national malaise.” More generally: “In both Disney’s imagination and the American imagination, one could assert one’s will on the world . . . . Indeed, in a typically American formulation, nothing but goodness and will mattered.” Disney’s desire to retreat into a controlled world echoes his country’s self-absorped conception of itself.

Despite these claims, Gabler doesn’t dwell much on the ways the studio seized what he calls “the American psyche,” perhaps because he senses that such explanations tend to be uninformative. One can grab almost any cluster of traits, find them in American popular art, and assert them as quintessentially American. This is how mainstream journalists make current Hollywood releases worth writing about: treating them not as artworks with distinctive appeals and a place in traditions and histories, but as reflections of whatever immediate social trends the writer chooses to pick out.

I won’t extend my criticism of Zeitgeist explanations here; it’s developed in the first essay in my forthcoming Poetics of Cinema. I’ll just say that I think we need more precise explanations than we get from easy juxtapositions of this or that film and some collective mood, sentiment, fantasy, or anxiety that we postulate as existing out there. Is there an American psyche? I’m not convinced.

An alternative to psychological speculation and Zeitgeist thinking is to look for more immediate causal connections. For example, Gabler traces how, around 1932, Disney began a new division of labor among his staff. He created a fairly strict set of specialties (story, gags, continuity sketches) and a chain of command in which head animators would become directors, overseeing particular projects. What’s the explanation of this change of policy? For Gabler, the new rationalization reflects not only the need to manage a bigger staff but also Walt’s effort in “reinventing and perfecting the system under which animations were produced.”

Gabler doesn’t mention that reorganizing the division of labor was going on throughout Hollywood at the same time. Most major studios were moving from a central producer system (this parallels the previous Disney lineup, with Walt at the top) to what Janet Staiger has called the producer-unit system, in which each man was charged with several productions.[3] Mentioning this doesn’t take away from Disney’s resourcefulness, but it does indicate that models for organizing his company were emerging right under his nose.

Similar issues could be examined by looking at Disney’s place in the overall ecology of Hollywood, as the premiere supplier of short subjects. His firm, Douglas Gomery argues, kept RKO afloat for many years. Gomery’s Hollywood Studio System: A History gives a cogent account of Disney’s role in the industry, and he goes somewhat beyond Gabler in tracing the studio’s emergence as in the 1950s as the prototype of modern conglomerate filmmaking.

Life in the cel

For Gabler, what made Walt reorganize production, and indeed what made him do nearly everything, was his obsessive pursuit of “quality” animation. But this quality itself remains fairly mysterious.

For Gabler, what made Walt reorganize production, and indeed what made him do nearly everything, was his obsessive pursuit of “quality” animation. But this quality itself remains fairly mysterious.

Gabler indicates that Disney moved away from the “rubber-hose” style of most cartoons, with their balloon heads, swollen paunches, and elastic arms and legs. (Even the clarinet goes limp in Harman-Ising’s A Great Big Bunch of You, from 1932, shown here.) Floppy limbs were fairly easy to animate. Gabler briskly summarizes Team Disney’s well-known innovations in naturalism, such as the studio’s emphasis on anatomy and life drawing, the breakdown of gestures, complex perspectives, and the rotoscoping of human figures.

Yet Gabler, a former movie critic for television, oddly doesn’t engage with the result of the technical innovations. He summarizes how journalists, critics, and academics have interpreted the movies’ cultural impact, but what he thinks about them as movies, rather than social or psychological symptoms, is almost completely suppressed. Does he admire Snow White or Dumbo or Pinocchio? Does he hate them? Has he studied them in preparation for the book? You will find more sensitive appreciation and critique in Leonard Maltin’s The Disney Films than in all of Gabler’s doorstop tome.

Gabler implicitly acknowledges the technical achievements of Snow White, Pinocchio, Fantasia, Dumbo, and Bambi, but after that he merely chronicles release after release with deadpan indifference. For example, he offers us nothing on the brilliant character animation of Song of the South (1946)–a film no longer in circulation because of its racial stereotyping.

Gabler follows tradition in suggesting that the UPA studio movies challenged Disney’s hyperrealism, but Disney was already moving toward something quite stylized. Gabler doesn’t observe the zesty play with color and line of Melody Time‘s “Blame It on the Samba” episode (1948). Eisenstein would have been pleased to see that the handling of Donald and Jose literalizes the metaphor feeling blue.

Working with lower budgets in the 1940s, the animators let their imaginations run wild. What a pleasure it must have been for Ward Kimball to come up with the funhouse nuttiness of the Serape song in The Three Caballeros (1945).

Kimball must have been quite a character; his parody book Art Afterpieces doesn’t spare the studio’s creatures. More generally, when Disney animators turned to illustrating pop music, they didn’t abandon the wilder sides of Fantasia.

There would be several fruitful ways to study the Art of Uncle Walt. One would require what I call rhapsodic criticism, writing that tries to evoke the movie’s look and feel through energetic, sensuous description. (This is, I think, what Susan Sontag meant in calling for “an erotics of art.”) Here is Don Crafton on the Felix the Cat cartoons:

Perhaps the most appealing aspect of Felix was his use of expressive body parts–a tail that forms gratuitous curlicues when he walks, or ears that click together like scissors. . . . He can mold himself into a mantel clock and have his nose mistakenly wound up; his tail can be an umbrella, a sword, or a clarinet, or Chaplin’s cane. He can use the tail as a bow to play a tune on his whiskers, then take one of the rising notes and use it for a doorkey. His skin is detachable. In Felix Trifles with Time (1925), a tailor flays him, then outfits a client with his pelt. When the man goes swimming, “naked” Felix retrieves his hide from the beach. [4]

In brief compass Crafton brings Felix alive for us. You don’t have to love Disney to write this way about his films; you do need a good eye, some pluck and gusto, plus a gift for language. Nothing like this is to be found in Gabler’s book.

Another way to get closer to Disney’s art is to just look at things more analytically. How does Disney create that expressive movement that Eisenstein admired? Partly, it seems, through having his figures move all over, and at the same instant. Reacting to a line of dialogue, a character can twist his waist, arch his back, swivel his shoulders, lift his head, arch his eyebrows, and raise a forefinger–all in a second or two. Two successive frames from Melody Time show Johnny Appleseed’s guardian angel in action, working his legs, arms, shoulders, jaw, and eyeballs simultaneously.

This is far from the minimal animation to which we became accustomed in the TV era. Treating gesture as a taut, rolling movement helps give Disney characters their unique volume and springiness, so different from the flabby postures of the rubber-hose style.

Or consider pacing, at which the Disney cartoons excel. Most studio animation of the period, constrained by smaller budgets than Disney had, speeded up production by filming each frame twice. That way only 12 cel drawings were needed for the 24 frames that consumed a second of film. One way Disney achieved expressive action, and the high quality to which Gabler refers, was to devote single frames–and cels–to details of particular movements. This choice, though expensive, allowed for exact adjustments in rhythm.

Sometimes there’s more than one movement per frame. You can occasionally find this strategy at work in other studios’ cartoons too, as Kristin has explained in an essay she mentions elsewhere in our blog. But Disney’s animators certainly used the technique with great panache. When Johnny, balancing on a branch, is caught in a rain of apples, he sweeps them up with lighting speed–a deft swirl made possible by multiplying character poses on each cel. If that means giving Johnny many arms and even detaching his hands, so be it.

Johnny’s arms and hands proliferate more quickly and widely as he scoops up the apples, but their number is reduced as he gathers them in to his chest, so the rhythm accelerates and decelerates. Through trial and error Disney’s animators learned that rather strange single images will look exactly right on the screen; these men were practical perceptual psychologists.

There are so many aspects of Disney’s art that need attention: the skill with line and contour; the sort of soft caricature that some consider cutesy but has enormous bounce and vibrancy; the ingenious use of color; and of course, Eisenstein’s “synchronization of senses” between image and music. There’s also Disney’s appropriation of developing live-action techniques, as in the proto-Wellesian crane shot in Pinocchio

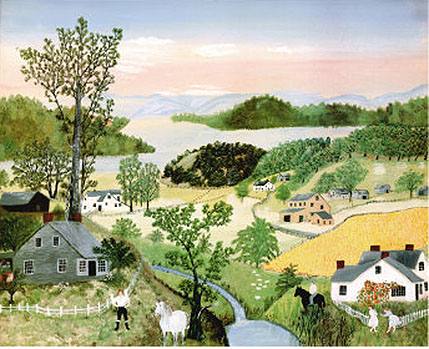

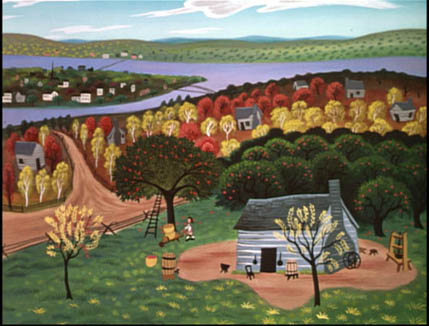

One could also study the studio’s borrowing of high-art motifs and styles. Instead of dismissing the 1940s and early 1950s Disneys as greeting-card kitsch, we can note that they evidently borrowed from the likes of WPA landscape art, American regionalist painting, and the naive-art look of Grandma Moses. (Her painting A Beautiful World, 1948 resembles Disney’s Johnny Appleseed of the same year.)

I’m a duffer in animation matters, so I’ve merely indicated some areas that intrigue me. The key source on the studio’s craft practice remains the gorgeous book The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation (1981, rev. 1995), by two of the great Nine Old Men, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnson. And I expect lots of discoveries in years to come from experts like Barrier, Maureen Furness, Paul Welles, Norman M. Klein, and many others. Since Gabler draws heavily on the research of others, often without naming names, he might have borrowed a bit more from scholars of animation aesthetics.

In fact, you could argue that without the artistic imagination displayed by Disney and his brilliant staff, these films couldn’t have captivated the American imagination. Whatever that is.

[1] Eisenstein on Disney, ed. Jay Leyda, trans. Alan Upchurch (Calcutta: Seagull, 1986), 2.

[2] “Career Tips for Control Freaks,” in The Education of a Comics Artist, ed. Michael Dooley and Steven Heller (New York: Allworth, 2005), 124-125.

[3] Janet Staiger, “The Producer-Unit System: Management by Specialization after 1931, in David Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), 320.

[4] Donald Crafton, Before Mickey: The Animated Film 1898-1928 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993; orig. 1982), 327, 328.