Archive for the 'Directors: Dreyer' Category

Rebooked

3/60 Baum in Herbst (Kurt Kren, 1960). Hand-drawn soundtrack.

DB here:

It’s time again to write up books that fate and friends have sent my way. And I do mean books, as in printed matter on paper held together by string and glue and wrapped in a decorative cover.

Nothing against e-books, mind you. I’ve put out a couple myself (see right sidebar), and I’ve become more inclined to use them for my research. Every academic sometimes needs to read only parts of a book–a chapter that touches on your project, a bibliography that can help you, chatty footnotes that can suggest a new idea. If your library hasn’t got a copy and Inter-Library Loan is difficult, an e-book can be worth the investment. The only real problem is the prospect of buying, in any format, a book that you must read but that you know will be dire. (Names and titles omitted for the sake of the new year’s mood.) Then at least the e-book, being less expensive, can mitigate the pain of paying, if not of reading.

Direness isn’t on the agenda for the books I have on the desk today. All are worth your attention, in whatever format you can get them.

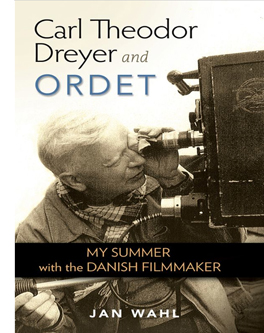

Before Jan Wahl became a prolific writer of children’s books, he left the US to study in Denmark. There he had the great fortune to be a dogsbody for Dreyer on the making of Ordet. Wahl left the country after the exterior shooting, but he kept in touch with Dreyer for some time afterward. His daily notes of their conversations were vetted and corrected by Dreyer, in hopes of eventual publication. Now, nearly sixty years later, the book has arrived.

Dreyer took a shine to the young Fulbright student and confided to him ideas about his earlier work and his plans for his Jesus film. Dreyer was at that point fairly undecided about many aspects of the Jesus script, including how to end the story. But these are sidelights compared to the central action of Wahl’s memoir, the making of Ordet in the cloudy and rainy summer of 1954.

Despite the inhospitable weather, Dreyer planned and shot much more action in exteriors than appeared in the final film. The film’s hermetic “theatricality” seems to have been arrived at through pruning landscape images and shots of characters coming and going. An especially intriguing shot of Anne and Anders meeting in a field took a great deal of time:

Despite the inhospitable weather, Dreyer planned and shot much more action in exteriors than appeared in the final film. The film’s hermetic “theatricality” seems to have been arrived at through pruning landscape images and shots of characters coming and going. An especially intriguing shot of Anne and Anders meeting in a field took a great deal of time:

Anne sets out to deliver a pair of trousers for her father, Peter Tailor, but she takes the long way around in order to have a tryst with Anders. The lovers meet in the field, lingering at a corner in the rye.

The camera had a long traveling movement, its tracks laid on a wooden platform in the shape of an immense letter L whose angle was parallel to the field. On that day, between three and five o’clock there was sufficient light for five takes. . . .

We’re also reminded of Dreyer’s fastidiousness—arranging sheep in ranks around the Borgen farmhouse and demanding that 1925 newspapers should line the drawers in the household. (Seeing a recent paper would “break the spell of concentration should an actor happen to see it.”) It’s a pity that Wahl could not stay through the whole production, which moved to the Palladium studio in the fall, to provide more details like this.

Just as ingratiating are Wahl’s accounts of the village where the film was shot, a tiny place taken over by Dreyer’s project. Wahl lingers over hearthside meals in a land where coffee has almost sacramental significance.

“There is something about coffee that soothes the Danes,” [Dreyer] said, “and puts them in touch with God. . . . On the winter days, which last so long here in Jutland, a warm cup is a balm; they take everyday communion in it.”

The primary value, I think, of Carl Theodor Dreyer and Ordet lies in atmospheric moments like these. I’ll always remember Wahl’s portrait of the gentle but obstinate Dreyer at sixty-five: dreaming of a film on Christ, smoking cigars, and tossing pastry crumbs to the bird that visits his garden every afternoon at three-thirty.

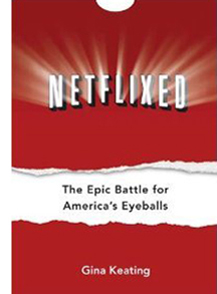

Pop quiz, hot shots:

What firm had the initial idea for VOD rentals? (Hint: Not Netflix.)

What firm had the initial idea for video kiosks? (Hint: Not Redbox.)

The answers, along with a solid story, can be found in Netflixed: The Epic Battle for America’s Eyeballs. Gina Keating’s brisk business reportage pits upstart Netflix against the well-entrenched Blockbuster in a cage match worthy of its title. Keating starts by demolishing Reed Hastings’s tale that he conjured up the service when he was annoyed by late fees on Apollo 13. In fact, tech entrepreneur Hastings entered the start-up as a fairly passive money guy, while the more retiring Marc Randolph devised the Netflix business model, which included what Keating calls an “intuitive user interface and peerless customer service.”

Keating shows how Randolph’s idea for an online video store on the Amazon model tapped into the expansion of internet retail. Randolph, according to Keating, “had what it took to conceive and launch Netflix. What came next—ruthless optimization and relentless growth—were not his strong suits.” By 2002, Randolph had left the company and Hastings ruled.

In counterpoint Keating chronicles Blockbuster’s ups and downs, mostly downs. It was already feeble when Netflix launched, and Viacom was perpetually trying to unload it. The decline was evident, however, in 2007 with the coming of CEO Jim Keyes, who had turned around 7-Eleven. Keyes decided to try to make Blockbuster outlets into “full-service entertainment destinations” where, according to Keating,

In counterpoint Keating chronicles Blockbuster’s ups and downs, mostly downs. It was already feeble when Netflix launched, and Viacom was perpetually trying to unload it. The decline was evident, however, in 2007 with the coming of CEO Jim Keyes, who had turned around 7-Eleven. Keyes decided to try to make Blockbuster outlets into “full-service entertainment destinations” where, according to Keating,

. . . customers would drop in for pizza and a Coke, or buy a book or a flat-screen television or hang out with their kids on weekends while waiting for a movie to download.

It was at this point that the Onion posted its YouTube video of the Living Blockbuster Museum. Still, Blockbuster should be credited with seeing the future of VOD. Execs tested it in 2001 (answer to Question One), but the concept had to wait until Internet access widened and download speeds picked up.

Netflix made missteps too. The firm let the staff who developed the video kiosk concept depart and form Redbox. (Answer to Question Two.) Hastings was also caught off-guard when Blockbuster Online began to surpass Netflix’s customer base. Still, you come away largely admiring the adroitness of the company. I hadn’t realized the power of Netflix’s software innovations, especially its recommendation engines.

Netflixed concentrates on major players, but Keating does introduce many economic-structural factors to provide higher context. And concentrating on personalities makes for a gripping read. Hastings, who declined to be interviewed for the book, is depicted as a math-mind who could inspire software engineers but who dealt coolly with human feelings in a way reminiscent of Steve Jobs. Carl Icahn, who stalks through many other histories of modern US media, has his moments too, mostly ones of fulmination.

Non-fun fact: A 2005 survey indicated that only 22% of Americans preferred to see a movie in a theatre rather than at home on video. And this was before the surge in VOD.

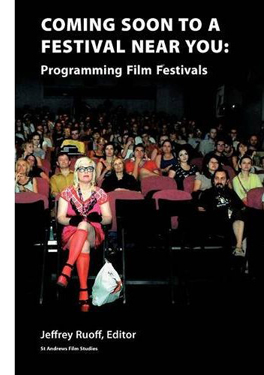

Netflix treated the Sundance Film Festival as a venue for dealmaking and PR. This is just one measure of the importance of such events for film as an art and a business. For decades our bookshelf devoted to film festivals harbored only a few volumes, mostly official histories of Cannes and Venice. By now, however, “festival studies” has become a teeming area of research. This is all to the good. International film culture after World War II, as we pointed out in Film History: An Introduction, has depended centrally on festivals, and film historians have to realize that these gatherings shape the history of cinema in many ways.

Netflix treated the Sundance Film Festival as a venue for dealmaking and PR. This is just one measure of the importance of such events for film as an art and a business. For decades our bookshelf devoted to film festivals harbored only a few volumes, mostly official histories of Cannes and Venice. By now, however, “festival studies” has become a teeming area of research. This is all to the good. International film culture after World War II, as we pointed out in Film History: An Introduction, has depended centrally on festivals, and film historians have to realize that these gatherings shape the history of cinema in many ways.

Jeffrey Ruoff’s new volume, Coming Soon to a Festival Near You: Programming Film Festivals, gathers several essays about the principles and pragmatics of deciding what’s shown. As Ruoff claims in his introduction, festivals perform many functions: they “celebrate film as an art, affirm different kinds of identity via film, [and] facilitate the marketing of films.”

Given these missions, the programmer functions minimally as a critic who aims to satisfy the audience’s tastes while steering it in novel directions. But the programmer can also be a celebrity in him- or herself, making the festival an extension of the programmer’s tastes, as happens with Michael Moore (Travers City), Roger Ebert (Ebertfest), and Tony Rayns’ Asian selections at Vancouver. This is what Ruoff calls the programmer as auteur.

The programmer is also a historian—reviving work from the past in retrospectives, while acting as a kind of future historian, laying down the conditions for later development in cinematic sensibility. The praise awarded to Bergman and Antonioni at 1950s and 1960s European festivals created a narrative of artistic development that historians who followed would elaborate.

Coming Soon to a Festival Near You offers a potpourri of pieces, from academically inflected accounts of festival history to personal memoirs from programmers and critics. Focus Features producer James Schamus provides a pungent entry on the economics of red-carpet galas, and Bill Pence, a long-standing fest entrepreneur, recounts the development of Telluride. All in all, Ruoff’s volume helps us understand the role of festivals as tastemakers and gatekeepers of world cinema.

“It is a country, culturally speaking, that respects its avant-garde filmmakers, present, past, and future,” writes Adrian Martin. He’s describing Austria, from which comes the magnificent volume Film Unframed: A History of Austrian Avant-Garde Cinema. Peter Tscherkassky, a major filmmaker himself, has created a collection that manages to be at once sweeping and in-depth. Many of us (but not enough) know work of the “old” masters Peter Kubelka and Kurt Kren, but this anthology skips back to the early 1950s. There we find artists like Kurt Steinwendner, whose Der Rabe (The Raven, 1951) looks to be a stark exercise in neo-Expressionism, done to electronic music.

“It is a country, culturally speaking, that respects its avant-garde filmmakers, present, past, and future,” writes Adrian Martin. He’s describing Austria, from which comes the magnificent volume Film Unframed: A History of Austrian Avant-Garde Cinema. Peter Tscherkassky, a major filmmaker himself, has created a collection that manages to be at once sweeping and in-depth. Many of us (but not enough) know work of the “old” masters Peter Kubelka and Kurt Kren, but this anthology skips back to the early 1950s. There we find artists like Kurt Steinwendner, whose Der Rabe (The Raven, 1951) looks to be a stark exercise in neo-Expressionism, done to electronic music.

As the chapters move toward the present, some names and films were familiar to me, most were not, but all emerged as intriguing and provocative. The diverse directions of experimentation are traced by some of our best writers (Maureen Turim, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Steve Anker, Andréa Picard, and Christoph Huber, among others). The hefty volume is filled out with color photographs and many pages of -graphies: bio-, filmo-, and biblio-.

Martin’s foreword, from which my initial quotation comes, sets the stage for a comprehensive reappraisal of this major tradition. We have to thank the film collective sixpackfilm and the Austrian Film Museum, which has become a leader in publishing books and DVD editions that mightily expand our horizons. Thanks also to the government subsidies that allow the book to be available at a very decent price. Next up, one hopes: A big fat DVD compilation.

In the fall of 1988 there materialized at my office an elvish man with a neat white beard and a Compaq laptop. He was perpetually smiling, and he soon revealed why: he had one of the quickest wits and sharpest senses of humor I’d encountered. The Lilly Endowment had awarded him a year’s grant to improve his knowledge of film. Very sensibly, he came to UW.

The faculty all welcomed him, and he became friends with Kristin and me. Tapping away quietly on his laptop, sitting on the far side of the front row (to keep plugged in), he took the most extensive and precise notes on my blahblah that I have ever seen. Recalling those days, I have to smile when I realize that the oldest person in the class was the only one who brought a computer. His notes circulated in samizdat among the grads for years.

His name was Peter Parshall. A film fan from his youth, Pete had taught film and literature at Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. He became famous as a beloved, highly demanding teacher: the student slogan was “Peter Parshall picked apart my perfect paper.” After his year in Madison, Pete went on a Fulbright Award to teach American film at the Technical University of Dresden. He retired from Rose-Hulman some years ago but kept active (bicycling, especially) and still teaches film courses.

His name was Peter Parshall. A film fan from his youth, Pete had taught film and literature at Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. He became famous as a beloved, highly demanding teacher: the student slogan was “Peter Parshall picked apart my perfect paper.” After his year in Madison, Pete went on a Fulbright Award to teach American film at the Technical University of Dresden. He retired from Rose-Hulman some years ago but kept active (bicycling, especially) and still teaches film courses.

Now Pete has published a probing book on a broad storytelling strategy that goes by many names—thread structure, hyperlinked plots, network narratives. Altman and After: Multiple Narratives in Film provides incisive analyses of several films, while also offering an illuminating set of categories for understanding them. Nashville is a “mosaic narrative,” an effort to surrender forward-driving plot in favor of fragments that pull the characters into teasingly incomplete patterns. Network narratives, with intersecting and culminating plotlines, are exemplified by Pulp Fiction, Amores Perros, Code Unknown, and The Edge of Heaven.

A new and intriguing category is the “database narrative.” Here the film launches a set of events but then replays them differently, providing alternative pathways for events. Sometimes this strategy is motivated as reflecting different points of view, as in Rashomon. But other tales question the very solidity of the narrative world, as in The Virgin Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Run Lola Run, and The Double Life of Véronique.

Pete’s book has already received praise, with Sarah Kozloff noting in Choice: “For several of these films, Parshall’s discussion is the best analysis available, and teachers and students have much to learn from his searching intelligence.” Altman and After is a fine addition to the growing list of books seeking to understand the permutations of today’s cinematic storytelling.

Torkell Saætervadet, a Norwegian expert on film technology and cinema design (and on aviation!), won our thanks with his authoritative 2005 text The Advanced Projection Manual. Now the International Federation of Film Archives, which co-sponsored the earlier volume, has brought out his new FIAF Digital Projection Guide.

Torkell Saætervadet, a Norwegian expert on film technology and cinema design (and on aviation!), won our thanks with his authoritative 2005 text The Advanced Projection Manual. Now the International Federation of Film Archives, which co-sponsored the earlier volume, has brought out his new FIAF Digital Projection Guide.

It’s a comprehensive overview, written with great lucidity and packed with charts and specs. Sætervadet covers the Digital Cinema Package file system, projection systems, 3-D systems, sound formats, and best practices for projectionists, including advice on preparing one’s own DCP hard drive. Along with judicious presentation of rival formats, Sætervadet provides informed opinions, including a persuasive account of why 4K projection is much to be preferred to 2K. As an inveterate sitter in the Raccoon Lodge, I was happy to learn of the importance of the “front-row rule” in measuring resolution in relation to screen size.

This is an indispensable book for anyone interested in current cinema technology. I wish it had been available when I wrote Pandora’s Digital Box. The Guide is available direct from FIAF and from Amazon.uk.

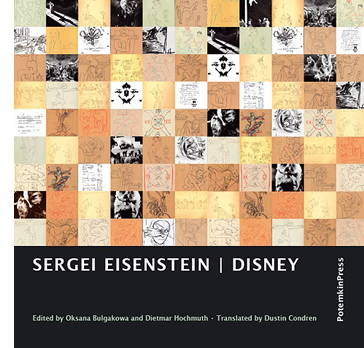

Finally, from the enterprising Potemkin Press comes a new edition of Eisenstein’s writings on Disney animation. An inveterate cartoonist himself, usually somewhere between Cocteau and Keith Haring, the polymath director reflected on Uncle Walt the artist throughout his career, but most deeply while he was at work on Ivan the Terrible. SME made no bones about it:

The work of this master is the greatest contribution of the American people to art–the greatest contribution of the Americans to world culture.

As often happens, Disney furnishes Eisenstein the occasion to launch a fantasia on what he’s been reading and thinking about since the last time he wrote. He hits on the ceaseless, “amoeba-like” change that animation permits and that Disney cartoons exploit. SME’s ruminations lead him into myth, ritual, medieval art, the drawings of Thurber and Steinberg, and much more. Typical is this:

TUSHMAKER’S TOOTHPULLER by John Phoenix, of course, stands in line with other plasmatic fancies. (Never observed this before.) Now I’ve just read some verses on the same topic by Walter de la Mare….

Much of the material is irreducibly private and may never be fully understood. Feel free to unleash your own associations on passages like this:

Octopi: Most plasmatic.

Merbabies.

The tiger is a goldfish.

↓

Lawrence.

↓

Horses like butterflies.

St. Mawr like a fish.

Back in 1986, Jay Leyda and Alan Upchurch gave us Eisenstein on Disney, a fine selection from these energetic, perplexing jottings. Unfortunately that book is currently rare and expensive. Now we have Sergei Eisenstein: Disney, edited by Oksana Bulgakowa and Dietmar Hochmuth. Based on recent archival discoveries, it incorporates more pieces and includes a more extensive commentary and an index. Dustin Condren’s translation reads fluently, and there are many illustrations. The editors employ varying fonts to label passages in different languages, although all passages, including SME’s obsessive cut-and-pastes from books, are fully rendered in English.

Oksana’s Afterword provides a historical account of the manuscript and an in-depth guide to the development of SME’s ideas at the period. She’s particularly helpful in explaining Eisenstein’s flirtation with psychoanalytical ideas. She flavors her account by itemizing the archaeological artifacts the researcher encounters:

Eisenstein writes on an incredible variety of paper–on the back of his own manuscripts and others’ screenplays, on Mosfilm’s or the film committee’s stationery, on concert programs. The annotations from the year 1944 are scribbled on 1942 calendar sheets. Call numbers for books from the library, telephone numbers, doctors’ prescribed diets, and a grocery list are all found in the text–cream meringues, sultanas, nuts.

When I learn things like this, I like him even more.

Sergei Eisenstein: Disney is a remarkable addition to the Eisenstein literature and ought to provoke lively debate in the animation community as well. But try to find or photocopy the Leyda/Upchurch volume too. It includes SME’s earlier 1932 notes on his drawings, where he floats his ideas about “plasmation,” and it has some different illustrations and its own helpful commentary. Both collections are invaluable to every Eisensteinian, which in a just and righteous world should mean everybody.

P.S. 28 January 2013: Thanks to Manfred Polak for correcting a misspelled name.

Thanks also to Peter Parshall for corrections in my memory of his visit (Compaq, not Apple as I’d said; Lilly grant; 1988; all duly adjusted above.) Details, details. He adds:

You probably don’t remember but the other students complained to you after the first day’s class because of the noise my computer keys made as I clattered away, trying desperately to keep up with the barrage of information coming at me. So when I came up to speak to you in my turn, you suggested that perhaps I shouldn’t use the computer. I was stunned! (All that money! That was one of the very first laptop models manufactured and it had cost a bundle!) The next day, instead of sitting in the back, I sat in the front row so that your voice would drown out my clatter and I announced at the class break that I’d put my notes on reserve. The complaints suddenly stopped.

Then on the first day of spring term, I was startled when a student rushed up to me and asked very anxiously what had happened to my notes!!! (I had taken them off reserve after exams were over, thinking they would no longer be needed.) No, No, he exclaimed. All the students wanted copies for prelims. So I put them back on reserve.

The climax to the joke came three or four years later when I flew into Rochester, NY, for a film conference and taxi-pooled with several other conferees to the hotel. I was delighted to learn that they were all grad students from UW, although I didn’t know any of them. I didn’t mention my name, it being of no scholarly importance, but simply said I taught in Indiana and had spent a sabbatical year at UW. A female voice with a rich British accent popped up from the back seat: “Oh, you’re Peetah Paahshall.” Turns out she had acquired a set of the samizdat. I chuckled at the thought of them still being handed on, from one generation of students to the next. . . . I know I learned a ton that year in Madison and if I could help the learning process for some UW students in return for all your hospitality, I was happy to do so.

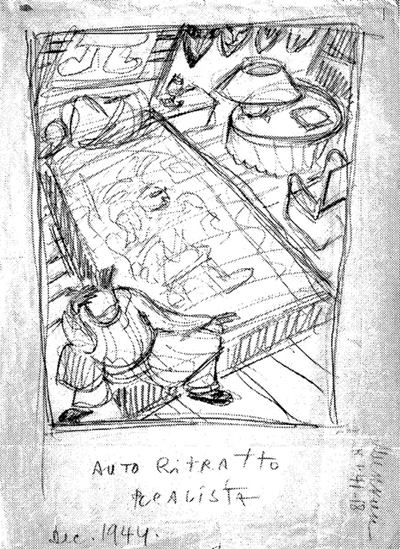

Eisenstein, Self-Portrait (1944).

The ten best films of … 1921

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

Kristin here:

To end the year, we’re continuing our tradition of picking the ten best films not of the current year but of ninety years ago. Our purpose is twofold. We want to provide guidance for those who may not be particularly familiar with silent cinema but who want to do a bit of exploring. We also want to throw in occasional unfamiliar films to shake up the canon of classics a bit.

Like last year, it was strangely difficult to come up with ten equally great films. There were some obvious choices, but beyond them there were a lot of slightly less wonderful items jostling for the other places on the list. The problem had several causes. Some master directors who routinely figure in our year-end ten choices had off-years. In 1921 D. W. Griffith released only one film, Dream Street, a notably weak item. (What I have to say about it can be found on pp. 108-113 of the British Film Institute’s The Griffith Project, Vol. 10.) Ernst Lubitsch released two films that seem like less interesting attempts to repeat earlier successes: Anna Boleyn (a pale imitation of Madame Dubarry) and Die Bergkatze (nice, and I was tempted to include it, but it’s less amusing than the Ossi Oswalda comedies, here and here). Cecil B. DeMille’s The Affairs of Anatol is not nearly as well structured as his earlier sophisticated rom-coms.

In other cases, films simply don’t survive. John Ford released seven films in 1921, all of which are lost.

Death comes calling, twice

Probably the easiest decision was to include The Phantom Carriage (also known as The Phantom Chariot), by Victor Sjöström. As I noted recently, the Criterion Collection has recently issued a beautiful restoration of it (DVD and Blu-ray).

When I first saw The Phantom Carriage, I was probably still an undergraduate. Given its reputation as a great classic, I was somewhat disappointed. No doubt it was partly the battered 16mm copy I watched, but the film is a bit formidable for someone not accustomed to the aesthetic of silent cinema–and especially of the great Swedish directors of the era. Its protagonist, played by Sjöström himself, is a thoroughly, determinedly unlikeable fellow, and the complex flashback structure can be a bit disconcerting on first viewing. But the effort to watch until one “gets” Sjöström is well worth it, since he’s undoubtedly one of the half dozen greatest silent directors.

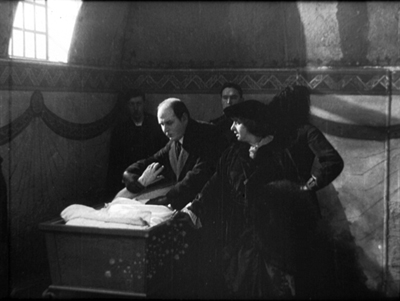

The story opens on New Year’s Eve with Edit, a young Salvation Army volunteer, on her deathbed. She unexpectedly begs her colleague and mother to fetch the town drunk, David Holm, to her bedside. At the same time, Holm sits drinking in a graveyard as midnight approache. He tells two fellow inebriates the legend of the phantom carriage, the vehicle that picks up the souls of the  newly dead; it is driven each year by the last person to die at the end of the previous year. Holm then dies, and the carriage arrives, with its current driver ready to turn over the job to him. Flashbacks enact both the circumstances of how the heroine met Holm and the happy family whom Holm had alienated through his drunkenness.

newly dead; it is driven each year by the last person to die at the end of the previous year. Holm then dies, and the carriage arrives, with its current driver ready to turn over the job to him. Flashbacks enact both the circumstances of how the heroine met Holm and the happy family whom Holm had alienated through his drunkenness.

It’s a deeply affecting story, wonderfully acted and staged. In most scenes the lighting and staging are impeccable, and the famous superimpositions that portray the carriage and the dead are highly ambitious for the period and impressively executed. The filmmakers have managed to make the carriage, superimposed on real landscapes, appear to pass behind rocks and other large objects. In short, a film that has everything going for it.

Death himself appears in Der müde Tod (literally “The Tired Death,” often called Destiny, or occasionally in the old days, The Three Candles). Here the great German director Fritz Lang hits his stride, and you can expect him to figure on most of our lists from now on.

In Destiny (available on DVD from Image Entertainment) a young woman’s fiancé is killed early on. Death, a sympathetic figure who regrets what he must do, gives her three chances to find another person whose demise can substitute for her lover’s. The three episodes in which she tries take place in Arabian-Nights Baghdad, Renaissance Venice, and ancient China; each story casts her as the heroine and her lover as the hero.Things don’t go well, and Death actually gives her a fourth chance when she returns to the present.

This was Lang’s first venture into the young German Expressionist movement, which had been launched the year before with Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. The style shows up only intermittently, perhaps most dramatically in the Venetian episode when the lover shinnies up a rope along a wall painted with a gigantic splash of light. (See bottom.)

Each film has a “happy ending.” I leave it to you to determine which is grimmer.

I’m turning over the keyboard to David now, to describe a film he knows better than I do.

More Northern European drama

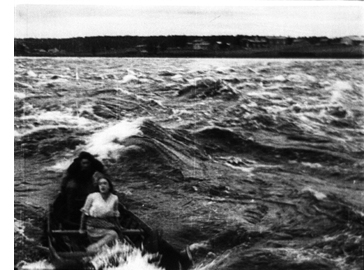

Mauritz Stiller alternated urban comedies (Thomas Graal’s Best Film, 1917; Thomas Graal’s Best Child, 1918; Erotikon, 1920) with more lyrical dramas and romances set in the countryside (Song of the Red Flower, 1919; Sir Arne’s Treasure, 1919). Johan (1921) is in the pastoral vein. Its integration of landscape into the drama suggests it was an effort to recapture the production values that overseas critics had praised in Sjöström’s Terje Vigen (1917) and The Outlaw and His Wife (1918). Like the Sjöström films, however, Johan offers more than splendid spectacle; it’s the study of the undercurrents of a marriage.

At the core is a love triangle. The fisherman Johan is the somewhat thick-headed son of a domineering mother. He is fond of the girl Merit, whom he and his mother rescued as a waif and brought into their household. But this synopsis is actually skewed, because Stiller and the scriptwriter Arthur Norden have told the story in an unusual way.

At the core is a love triangle. The fisherman Johan is the somewhat thick-headed son of a domineering mother. He is fond of the girl Merit, whom he and his mother rescued as a waif and brought into their household. But this synopsis is actually skewed, because Stiller and the scriptwriter Arthur Norden have told the story in an unusual way.

We’re introduced to the couple by following the rogue Vallavan’s entry into the town; Johan seems almost a secondary character until Vallavan leaves. When Johan breaks his leg, Merit agrees to be his wife. Now we’re attached to her standoint and see her life of drudgery under the petty tyranny of Johan’s mother. Vallavan returns, and Merit falls under his spell. Taking her hand, he says, “I want to rescue you.” After she has fled with him, Johan clumsily wanders the rocky shore. “Will I ever see Merit again in this life?” The narrational weight passes to him as he decides to pursue the runaways.

Like Sjöström’s Sons of Ingmar (1918-1919), Johan presents marriage as a trap for unwary women. Our shifting attachment, from Vallavan to Merit and eventually to Johan, allows us to see the situation in many dimensions. As a sort of parallel, Stiller makes fluid use of the now solidly-established conventions of continuity editing. Vallavan’s seduction of Merit is played out in tense shot/ reverse-shot, and there’s an engrossing moment involving delicate shifts in point of view. When the bedridden Johan sees Merit leaving, after his mother has cast her out of the house, he must smash a window pane with his elbow in order to call to her. Stiller’s dynamic eyelines, direction of movement, and precise changes of camera setup here show that he had mastered the American style.

Alongside this finesse, there is still plenty of outdoor action, highlighted when Vallavan rows Merit away in the tumultuous river. Filmed from another boat, the actors are all but engulfed by the waves. It was presumably scenes like this that the parent company, Svensk Filmindustri, hoped would attract international attention. At this period Svensk, dominant in the local industry, was hoping to sell its films on a global scale. That ambitious plan failed, but it left us with many outstanding movies and soon brought Stiller, along with Sjöström, to Hollywood.

Johan is available on a Region 2 PAL DVD, coupled with Kaurismaki’s Juha, another adaptation of the Juhani Aho story.

The joys of small-town life

Last year I included two films by William C. deMille, the considerably less famous brother of Cecil B. The year 1921 saw the release of what is today his best-known film, Miss Lulu Bett. It was based  on the popular novel and play by Wisconsin author Zona Gale, who received her MA here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and in 1921 became the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for drama. The story centers around the heroine, a spinster who lives with her sister’s family, including her niece, nephew, and brother-in-law, Dwight Deacon. Dwight is a tyrant who delights in taunting Lulu over her unwed status, and the rest of the family treats her as a servant.

on the popular novel and play by Wisconsin author Zona Gale, who received her MA here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and in 1921 became the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for drama. The story centers around the heroine, a spinster who lives with her sister’s family, including her niece, nephew, and brother-in-law, Dwight Deacon. Dwight is a tyrant who delights in taunting Lulu over her unwed status, and the rest of the family treats her as a servant.

The return of the husband’s globetrotting younger brother Ninian after a twenty-year absence injects some life into the situation. Taking the family out to dinner, he realizes just how boring the family is (right), and to liven things up, suggests that he and Lulu perform mock marriage vows. Dwight realizes that the ceremony is legally binding, and, already attracted to Lulu, Ninian suggests that they treat it as a real marriage. Desperate to escape her dreary situation, Lulu agrees. The relationship proves agreeable, and Lulu declares that she will learn to love Ninian–when he reveals that he had previously been married, though he doesn’t know whether his first wife is dead (in which case he and Lulu are married) or alive (in which case they aren’t). Unwilling to take a chance, Lulu returns to the Deacons, who consider her disgraced and treat her even worse.

The film avoids melodrama. Ninian is not a villain; he’s kind to Lulu and sorry for the position he’s placed her in. It remains to Lulu to summon the gumption to leave the family and find her own happiness.The whole thing is told with restraint and little touches of humor that draw the viewer into a deep sympathy with Lulu’s plight.

Lois Wilson’s performance as Lulu is crucial in this. She is at once plain enough that we can believe she is in danger of becoming an old maid and pretty enough to plausibly attract the attention of the handsome local schoolteacher. Wilson’s most prominent role came two years later, when she starred as the heroine in James Cruze’s The Covered Wagon.

Miss Lulu Bett is the only one of William’s films available on DVD, paired with Cecil’s Why Change Your Wife? As so often happened, William seems to take a back seat to his famous brother, but the pairing is a logical one, in that William wrote the script for Why Change Your Wife?

Another small-town drama of the same year is Lois Weber’s The Blot. In 1981, when I was teaching a course on American silent film at the University of Iowa, I wanted to quickly demonstrate to the students that the silent period was not an era of exaggerated acting and naively melodramatic plots. I showed a double feature of The Blot and King Vidor’s Wine of Youth (1924). The latter portrays changing sexual mores through the story of three generations of the same family, with a young woman of the Roaring Twenties questions the necessity of marriage when she discovers that her mother is contemplating divorce. I think Wine of Youth (unfortunately not available on video) and The Blot convinced my class that silent films could be both sophisticated and subtly acted.

The “blot” of Weber’s title refers to the notion that people in professions depending on intelligence and education are poorly paid, while tradespeople and children from rich families are well off. The representatives of the underpaid are a college teacher, Prof. Griggs, and a young, idealistic minister. The parallels to recent events are striking. College professors may not be so badly paid as in the 1920s, but the move toward institutions of higher learning depending on adjunct lecturers has created a similar issue. In general, the income gap is familiar: the rich young wastrels taking Prof. Griggs’s course represent what we now call the one percent, while the professor and minister live on a much lower plane.

Weber’s drama is not quite this bald, however. Various levels of prosperity are represented. The professor’s family lives in shabby gentility, his wife grimly struggling to keep food on the table and his daughter Amelia, in delicate health due to a lack of nourishing food, working in the local library. Their neighbors are the family of a successful shoemaker, who live well but lack education. The shoemaker’s wife in particular resents what she perceives as intellectual snobbishness in the professor’s family and takes every opportunity she can to flaunt her comparative wealth.

Her son, however, has a crush on Amelia, as does the poor minister. Into this situation comes Phil West, the professor’s rich but indolent and mischievous student. Also attracted to Amelia, Phil for the first time encounters real poverty and is  shocked by it. As the plot develops, Amelia falls ill, and her mother’s increasingly desperate efforts to obtain the food necessary to nurse her to health become one of the main threads of the drama. To say that a large part of the action in the second half of the film centers on Mrs. Griggs’s temptation to steal a chicken from her neighbors might make the situation seem a trifle comic, but Margaret McWade’s remarkable performance vividly conveys the wife’s struggle in the face of real lack and her humiliations in the eyes of the shoemaker’s gloating wife. When Mrs. Griggs succumbs to temptation, the result is a brief but wrenching scene.

shocked by it. As the plot develops, Amelia falls ill, and her mother’s increasingly desperate efforts to obtain the food necessary to nurse her to health become one of the main threads of the drama. To say that a large part of the action in the second half of the film centers on Mrs. Griggs’s temptation to steal a chicken from her neighbors might make the situation seem a trifle comic, but Margaret McWade’s remarkable performance vividly conveys the wife’s struggle in the face of real lack and her humiliations in the eyes of the shoemaker’s gloating wife. When Mrs. Griggs succumbs to temptation, the result is a brief but wrenching scene.

The plot is remarkably dense and unpredictable. Every scene involves glances that lead to new knowledge or serious misunderstanding, deflecting the plot into new directions. Early on it is impossible to say which of the three young men Amelia will end up with, and even by the late scenes, when only two plausible romantic candidates remain, we have no idea which she will pick. As in many of Weber’s films, she does a bit of preaching about the social problem involved, but in The Blot she leaves this until near the end and gets it over quickly and fairly believably. The considerable but gradual change in Phil’s attitude toward education and the problems of poverty is also made believable. The prosperous neighbor’s change of attitude may seem a bit sudden, though it is somewhat motivated by a line early on.

But on the whole, even more than with Miss Lulu Bett, this is an absorbing story with characters for whom we care. Weber uses motifs as skillfully as any director in the early phase of the classical Hollywood cinema. Watch in particular how many different ways she uses the Griggs family’s cat and her two kittens: to demonstrate the family’s poverty, to be the main means of the neighbor lady’s spite, to introduce some comedy, and so on. Even more pervasive is the way that shoes become tokens of characters’ various social positions.

The Blot is available on DVD from Image. Those interested in Weber as a director should note that next summer’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna plans a retrospective of her work.

Which is best? Damfino.

In past year-end lists, we’ve watched Harold Lloyd, Charles Chaplin, and Buster Keaton creeping toward their great features of the 1920s. This year two of them move cautiously into longer films, and the other releases two more terrific one-reelers.

The Boat is one of Keaton’s most admired shorts. In it, he, his wife, and their two young sons build a boat, the Damfino, and unwisely launch it on the open ocean. Everything that can go wrong does: the life-preserver sinks, the anchor floats, and naturally a storm hits. The wife’s pancakes aren’t edible, but one temporarily patches a leak. Throughout the intrepid band carries on against all obstacles.

Less perfect but more dazzling and (perhaps) funnier is The Playhouse. The premise of a small variety theater creates an episodic, messy narrative, but it allows Keaton to play out a series of four “acts.” Initially we see Keaton buy a ticket and enter an auditorium where the audience, the orchestra, and all the performers are played by “Buster Keaton.” As one of the audience members remarks, “This fellow Keaton seems to be the whole show,” which is true in more way than one. The multiple images of Keaton were accomplished entirely in the camera, by cranking back the film with precise timing and uncovering a different part of the lens at each pass. The precision when one Keaton figure talks to or dances with another is amazing.

This all turns out to be a stagehand’s dream. (Keaton being the stagehand.) The multiplication motif returns as an act involving two pretty girls who happen to be twins–something Buster  doesn’t know, making his encounters with them ever more baffling. Later an orangutan escapes, and Buster dons make-up and costume to replace him. All hilarious stuff, though unfortunately the final act, a Zouave Guard drill, is the least funny one. Still, it’s a terrific film with a big dose of the surrealist quality that will run through the later shorts and the features.

doesn’t know, making his encounters with them ever more baffling. Later an orangutan escapes, and Buster dons make-up and costume to replace him. All hilarious stuff, though unfortunately the final act, a Zouave Guard drill, is the least funny one. Still, it’s a terrific film with a big dose of the surrealist quality that will run through the later shorts and the features.

The Boat is included on Kino’s disc of The Navigator and The Playhouse with their out-of-print DVD of The General. Still in print, however, is Kino’s eleven-disc set of the features and shorts. For those in the UK and other region-2 countries, Eureka! has a “Masters of Cinema” three-disc set, “Buster Keaton: The Complete Short Films 1917-1923,” which includes many of his earlier films with Fatty Arbuckle.

The year saw Lloyd and Chaplin make their first feature films, though both releases were still fairly short. I’m not really counting A Sailor-Made Man as one of the top ten of the year, since it’s a delightful but decidedly light item. Just another reminder that Lloyd is inching toward greatness.

Lloyd presents his “glasses” character as a brash young man who impulsively proposes to a rich man’s daughter. When the father demands that he get a job to prove his worth, Harold enlists in the navy. Highjinks ensure, culminating in a lively chase-and-rescue scene when the heroine gets kidnapped by a lecherous Arabian sheik.

Lloyd presents his “glasses” character as a brash young man who impulsively proposes to a rich man’s daughter. When the father demands that he get a job to prove his worth, Harold enlists in the navy. Highjinks ensure, culminating in a lively chase-and-rescue scene when the heroine gets kidnapped by a lecherous Arabian sheik.

The shipboard scenes allow Harold to get in some funny bits, mainly involving him trying to be tough and succeeding at first by sheer accident. Later, however, he is inspired by the heroine’s danger to become a real rescuer. It’s a sign of bigger things to come.

New Line’s Harold Lloyd boxed set is out of print, but you can still get the volumes separately. A Sailor-Made Man is in Volume 3, along with such delights as Hot Water and For Heaven’s Sake.

Chaplin’s first feature, The Kid, is a skillful blend of the rough-and-tumble slapstick that had characterized his early shorts and the sentimentality that would gradually become a more prominent trait of his films. A unmarried woman (played by Edna Purviance, the elegant beauty who made such a contrast with the Little Tramp in many of his films) abandons her infant in an expensive car which happens to get stolen moments later. Charlie finds the baby, and after numerous attempts to get rid of it–including a brief contemplation of an open storm-sewer grate–decides to raise it. The baby grows into the adorable and amusing Jackie Coogan.

Chaplin’s first feature, The Kid, is a skillful blend of the rough-and-tumble slapstick that had characterized his early shorts and the sentimentality that would gradually become a more prominent trait of his films. A unmarried woman (played by Edna Purviance, the elegant beauty who made such a contrast with the Little Tramp in many of his films) abandons her infant in an expensive car which happens to get stolen moments later. Charlie finds the baby, and after numerous attempts to get rid of it–including a brief contemplation of an open storm-sewer grate–decides to raise it. The baby grows into the adorable and amusing Jackie Coogan.

In the meantime, the mother has become a rich singer, and coincidentally she comes to the slums doing charitable work. The authorities eventually try to remove the Kid to an orphanage, and later a flop-house proprietor turns him in to receive a reward. Still, Chaplin doesn’t milk the pathos, and a happy ending duly arrives.

The Kid is available in a decent print along with A Day’s Pleasure and Sunnyside on the “Charlie Chaplin Special” DVD. Our recording off Turner Classic Movies strikes me as being slightly better quality, so you might keep an open to see if they reshow it. It was also announced this week that The Kid has been added to the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress.

Fuzzy movies, big and small

Soft-style cinematography had been tried in some films of the late 1910s, most notably in Griffith’s Broken Blossoms. But in the 1920s it spread. In Hollywood, it was mainly a technique for making beautiful images and especially for creating glamorous close-ups of actresses. In France, it was a way of tracking a character’s inner life.

Vicente Blasco Ibáñez’s 1918 novel, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse was a huge bestseller, and the first film adaptation in 1921, directed by Rex Ingram, was equally successful. To many, it is remembered for having made a super-star of its main actor, Rudolph Valentino. Anyone who has seen him as the caricatured Latin Lover of his later films will be pleasantly surprised to discover that the man could act, as could his leading lady, the lovely Alice Terry.

Ingram was the quintessential middlebrow director of the 1920s, doing big-budget, respectable adaptations of popular literature (e.g., Scaramouche, The Prisoner of Zenda). To me, Four Horsemen escapes the stodginess of the later films, at least to some extent (as does his other 1921 film, The Conquering Power). It and the other film in this section were borderline cases, chosen as much for their historical importance as their quality, perhaps, but definitely worth watching.

One of Four Horsemen‘s greatest strengths is its photography. Ingram worked consistently with one of the greatest cinematographers of the 1920s, John F. Seitz, who created glowing images of  sets and actors with selective lighting and all sort of means of softening the image. This film, more than Broken Blossoms, brought the soft style into vogue. It eventually culminated in the Dietrich films of Josef von Sternberg before a more hard-edged look came to dominate the 1940s.

sets and actors with selective lighting and all sort of means of softening the image. This film, more than Broken Blossoms, brought the soft style into vogue. It eventually culminated in the Dietrich films of Josef von Sternberg before a more hard-edged look came to dominate the 1940s.

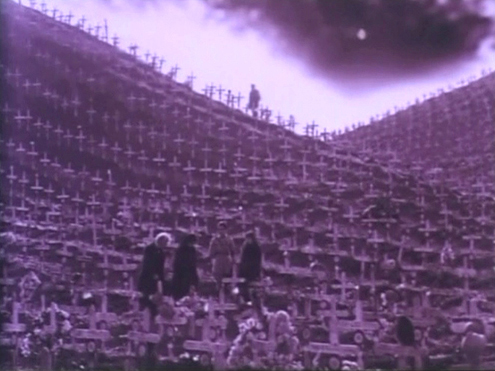

Four Horsemen was also an early entry in the anti-World War I genre of the 1920s and 1930s. Its final scene in a vast military cemetery of identical white crosses remains a powerful one. (See above.) Here, however, the Germans are still stereotypes, militaristic puppets with no redeeming features. Even that notion would gradually change, however, until nine years later All Quiet on the Western Front could recount the war from the German point of view.

Four Horsemen is available on DVD on demand from Amazon, supplied on DVD-R. In the same format, one can order it on a set with a documentary on Valentino. The reviews of the latter suggest that the visual quality is good.

(For more on this photographic style, see my “The soft style of cinematography,” in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, pp. 287-293.)

I’m not a huge fan of Marcel L’Herbier, and I’m not entirely sure that El Dorado is a full-fledged  masterpiece. But it has many virtues, and arguably it’s historically important as the first film of the French Impressionist movement to thoroughly explore ways in which camera techniques could convey perceptual and psychological states. It focuses largely on Sibilla, a singer-dancer who is the main attraction in a tawdry Spanish bar. She and some other women are performing as the story begins, but Sibilla is distracted by worries about her sick son. L’Herbier experimented with tracing her attention by placing gauzy filters over her face when she starts thinking of the boy. In the frame at the left, for example, she is in sharp focus when onstage, but as she passes into the backstage area, she goes fuzzy.

masterpiece. But it has many virtues, and arguably it’s historically important as the first film of the French Impressionist movement to thoroughly explore ways in which camera techniques could convey perceptual and psychological states. It focuses largely on Sibilla, a singer-dancer who is the main attraction in a tawdry Spanish bar. She and some other women are performing as the story begins, but Sibilla is distracted by worries about her sick son. L’Herbier experimented with tracing her attention by placing gauzy filters over her face when she starts thinking of the boy. In the frame at the left, for example, she is in sharp focus when onstage, but as she passes into the backstage area, she goes fuzzy.

In a way this is a somewhat silly, literal notion, and yet it’s exciting to see filmmakers exploring new devices relatively early in film history. Gauzy filters, distorting mirrors, slow-motion superimpositions, rhythmic cutting, and subjective moving camera were soon to be in common use by a small group of French directors. El Dorado was also the first film to be filmed within the Alhambra, which lends it considerable visual interest.

If we’re still writing this blog in 2019, our list will probably include the culminating film of the movement, and arguably L’Herbier’s best silent film, L’Argent.

Not many French Impressionist films are available in the U.S. If you have a multi-region player, El Dorado is paired with L’Herbier’s earlier L’homme du large (1920) on a French DVD.

Tigers and lepers and a mysterious yogi

We tend to think of serials as having many episodes and being low-budget additions to programs. That’s the American model, but in Europe things were different. Louis Feuillade’s serials are among the gems of the 1910s. In Germany, serials tended to have fewer episodes but bigger budgets–much bigger. Many were only two parts, most famously Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (coming next year to our top-ten list) and Die Nibelungen (coming in 2014). Lang had launched into serials with Die Spinnen (1919 and 1920). The two parts have terrific things in them, but Lang never went on to finish it.

He was, however, still collaborating on screenplays for director Joe May, who specialized in epic serials set in exotic countries and starring his wife, Mia May. Highly entertaining though these films are, they are largely forgotten, even by most lovers of silent cinema. Das indische Grabmal is the exception, though even now few have had a chance to see it. In 1996 it was shown at “Il Gionate del Cinema Muto” festival in Pordenone and was all too briefly available on an Image DVD (as The Indian Tomb) now out of print. Track it down if you can.

Full of the stars of its day, Das indische Grabmal is set largely in India, and its plot was inspired by the Taj Mahal. A ruthless maharajah (played with relish by Conrad Veidt) cloaks his cruelty under a veneer of European courtesy. He plots to shut his unfaithful princess (Erna Morena) in a beautiful tomb along with her lover (Paul Richter, better known to modern audiences as Siegfried). He calls in a famous European architect (Danish star Olaf Fønss) to build it, and the architect’s fiancée (Mia May), rightly fearing dirty work afoot, follows. One pit full of tigers and one of lepers lie waiting to endanger the visitors. The sets are beautiful. The Germans by this point could do them at full scale (above left) and as marvelously deceptive miniatures (above right). Das indische Grabmal is constantly entertaining and perhaps the best of its type, at least of the films we have access to.

Lang directed a two-part remake of this film in 1959. Both are good, but I prefer the silent one.

Some runners-up

As I mentioned, we had trouble narrowing down our list this year. Here are some others that could have replaced some of our prime choices. The German stage director Leopold Jessner adapted the play Hintertreppe (Backstairs). It’s a Kammerspiel, set in two apartments and the courtyard between them, and concerns a simple love triangle among a maid, her absent lover, and the postman who loves the maid so much that he forges letters from her sweetheart to keep her happy. Antti Alanen kindly reprinted my notes on the film here.

Carl Dreyer’s third feature, Leaves from Satan’s Book, remains one of the most widely-admired variants on the Intolerance formula of presenting thematically linked historical episodes. The dynamic final last-minute non-rescue shows that Dreyer learned a good deal from Griffith’s crosscutting too. Leaves is available on a Danish DVD with English subtitles and an alternate ending. Murata Minoru’s Japanese feature Souls on the Road, another exercise in complex crosscutting, and Feuillade’s polished L’Orphéline are solid runners-up as well. Neither is available on commercial DVD, as far as we know.

Destiny.

Silents nights: DVD stocking-stuffers for those long winter evenings

Von Morgens bis Mitternachts

Kristin here:

The year 2011 has been a good year for silent cinema on DVD. In time for the holiday shopping season, here’s an overview of some of the highlights.

One-stop shopping for the latest restorations

In the past we have recommended films released on DVD through the Munich Film Museum’s Edition Filmmuseum. We haven’t really emphasized enough, however, what a major resource this site is for film enthusiasts interested in restorations of older films and new editions of hard-to-see modern films (like the work of James Benning). Edition Filmmuseum sells not only its own impressive series of releases but also DVD editions of restorations by other major national European archives. Its website is available in German and English versions, and it is as easy to sign up and order DVDs there as it is through Amazon. The DVDs on offer can be browsed via a number of different categories, such as “Silent films,” “German movies,” and “Danish classics.” Releases from Lobster Films and Flicker Alley are also available through Edition Filmmuseum. Have a look at its forthcoming releases here. North American educational institutions seeking public performance rights for many of these and other titles should contact Gartenberg Media Entertainment.

Scandinavia comes on strong

Danish and Swedish films show up fairly regularly on DVD these days, but Norwegian films are rarities. This year, though, there are two of them.

The Danish Film Institute continues to release the films of Carl Theodor Dreyer. This time it’s a pairing of Elsker Hverandre (Love One Another, 1922) and Glomdalsbruden (The Bride of Glomdal, 1926), also available in Blu-ray. (See below.) I have to admit that these are not among my favorite Dreyer films, and I don’t think many would put them alongside his best works. Still, Dreyer is one of the great masters of world cinema, and anyone seriously interested in film history will want to see these. Back when David was working on his book on Dreyer, we went to Copenhagen and saw these at the Film Institute. They were incredibly rare, and it was a privilege to see them. Now, they’re available to all. Check out the Institute’s entire list of restored Danish classics on DVD here.

[Dec. 16: Archivist Jan-Christopher Horak has recently blogged about Elsker Hverandre.]

The Bride of Glomdal is the first of our two Norwegian features. Dreyer worked outside Denmark a number of times. In the summer of 1925 he shot this film in Norway. His next film was to be La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc.

The second is Laila, a 1929 Norwegian feature, also with a Dreyer connection. Its director, George Schéevoigt, had been Dreyer’s  cinematographer for some of his early films: Leaves from Satan’s Book, The Parson’s Widow, Once Upon a Time, and Master of the House. Laila bears no sign of Dreyer’s influence, but its images, shot in the snowy mountains and valleys of the arctic regions of Norway, are gorgeous.

cinematographer for some of his early films: Leaves from Satan’s Book, The Parson’s Widow, Once Upon a Time, and Master of the House. Laila bears no sign of Dreyer’s influence, but its images, shot in the snowy mountains and valleys of the arctic regions of Norway, are gorgeous.

Like many features made in countries with no real established film industry (Laila’s footage had to be processed and edited in Copenhagen), Laila exploits both national literature and landscapes to distinguish itself from the Hollywood films that dominated European theaters. It was based on an 1881 novel by J. A Friis, Fra Minmarken, Skildringer. Friis strove to promote the rights of the indigenous Sami people (sometimes known as Lapps). The story follows the heroine, Laila, from infancy to adulthood. The first half of the film succeeds in giving a distinctly non-classical feel to the story. Laila is lost in the snowy wastes when wolves attack her family as they travel on sleds. She is found and nurtured by a childless Sami couple who come to love her but return her to her parents when they learn her background. The scene of the return is handled in a subtle and moving fashion. As the grieving parents console each other on Christmas Eve, Aslag, the baby’s foster father, enters at the left, with the tree blocking the door. He crosses to appear at the center and puts the child beside the presents under the tree:

A cut-in to Aslag shows him struggling with his emotions before turning to the parents and declaring, “Tonight all should be happy.” The mystified parents stare at him uncomprehendingly before he explains that he had found their daughter:

Once Laila grows up, the film turns into the more typical romantic triangle. Still, its epic landscapes and focus on a little-known ethnic group make it quite appealing, and the print itself is gorgeous. Flicker Alley has provided a rare opportunity to step outside the more familiar filmmaking countries and explore a bit. Our friend, the fine Danish film historian Casper Tyberg, has provided a helpful text in the accompanying booklet.

Casper also provides a commentary for The Criterion Collection’s release of the restored version of Victor Sjöström’s The Phantom Chariot. (It’s number 579 for you Criterion completists–but you already know about this disc anyway.) I won’t say much about it, since it will inevitably show up in our year-end list of the ten best films of 1921. Here I’ll just note that it’s also a beautiful print, with impeccable tinting and toning that don’t darken the images to the point where the composition is obscured–something I’ve seen too often in recent DVD releases of silent films. The frame above shows the opening scene, with its masterful control of lighting. I was disappointed that the supplements stress Sjöström’s influence on Ingmar Bergman. It may sound heretical, but Sjöström seems to me the better director, and I wish there had been more on his career.

One of the most obscure of German Expressionist films

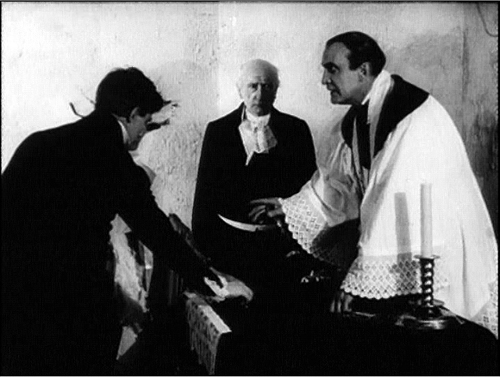

Von Morgens bis Mitternachts (“From Morning to Midnight”) is an early Expressionist film. It came out the same year as Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. It’s based on a play by one of the major Expressionist dramatists, Georg Kaiser, and directed by one of the major Expressionist stage directors, Karlheinz Martin. The problem is, it never got released in Germany.

Most of the classic Expressionist films are, like Caligari, horror films that motivate their stylization through genre. Von Morgens bis Mitternachts adheres to the subject matter of Expressionist theater, which was vehemently critical of modern society. It centers around a downtrodden bank clerk who suddenly rebels against his apparently happy family life and good job, stealing a huge sum from the bank and trying to run off with a glamorous rich woman who visits the bank. Rejected by her, he wanders away to spend the money in frivolous pursuits.

It’s no wonder that German distribution companies shied away from releasing the film. Its only known theatrical screenings were in Japan, where one nitrate positive print survived. I saw an archival copy years ago. It was an impressive film, more extreme in its stylization than Caligari or even Robert Wiene’s second Expressionist film, Genuine. (All three films were released in 1920.) Unfortunately it had no intertitles, which made it seem all the more radical.

In 1987 censorship records were discovered that allowed the Munich Filmmuseum to reconstruct the intertitles and create the restored version that now has been released on DVD. It’s a significant film, not only as an artistic achievement but as a record of stage  Expressionism of the 1910s. Few plays of the era were filmed, most importantly this one and Jeopold Jessner’s 1923 film Erdgeist, adapted from the play by Frank Wedekind and starring Asta Nielsen and Albert Bassermann. (The play was adapted again by G. W. Pabst as Pandora’s Box, starring Louise Brooks, in 1929; wonderful though that version is, it retains little of the radical Expressionism of the original.)

Expressionism of the 1910s. Few plays of the era were filmed, most importantly this one and Jeopold Jessner’s 1923 film Erdgeist, adapted from the play by Frank Wedekind and starring Asta Nielsen and Albert Bassermann. (The play was adapted again by G. W. Pabst as Pandora’s Box, starring Louise Brooks, in 1929; wonderful though that version is, it retains little of the radical Expressionism of the original.)

Von Morgens bis Mitternachts has some of the most avant-garde set designs of the era. Jagged white sets are smeared across back voids, as in the scene at the top where the protagonist flees down an endlessly winding road after being rebuffed by the woman for whom he impetuously stole money. It records another performance by one of the leading Expressionist actors of the era, Ernst Deutsch, whom I mentioned in my entry on Der Golem. Apart from its jagged sets, the film features a remarkable scene at a bicycle race, with the contestants being filmed in a distorting mirror. It was a technique that the French Impressionists would soon popularize, but Martin may have used it first (see left).

Despite the film’s lack of impact at the time it was made, it belongs squarely within the German Expressionist movement. This release at last allows it to take its place. (The forthcoming issue of the restored Expressionist science-fiction film Algol, also from 1920, will give an even broader picture of the movement.)

Eureka! Ford is found

The British company Eureka! continues to bring out classic films of all sorts. Its “Masters of Cinema” series has released John Ford’s 1924 western,  The Iron Horse. By this point in his career, Ford has made many western features, only a few of which survive. They were lively low-budget films, but by the early 1920s the western became a prestige genre with the success of James Cruze’s The Covered Wagon in 1923. The Iron Horse was Ford’s move into the high-budget western, and what it lacks in high-spirited energy it makes up for in impressive landscapes and careful dramatic staging. The Indian attack on the train, revealed by shadows (right) is one of the film’s high points.

The Iron Horse. By this point in his career, Ford has made many western features, only a few of which survive. They were lively low-budget films, but by the early 1920s the western became a prestige genre with the success of James Cruze’s The Covered Wagon in 1923. The Iron Horse was Ford’s move into the high-budget western, and what it lacks in high-spirited energy it makes up for in impressive landscapes and careful dramatic staging. The Indian attack on the train, revealed by shadows (right) is one of the film’s high points.

This Eureka! release is the same version and has the same extras as the DVD in the American series “Ford at Fox.” The two-disc set includes both the 150-minute version released in the U.S. and a 133-minute version, with alternate takes, distributed abroad. Anyone in European Region 2 area who doesn’t want to buy the immense “Ford at Fox” set of 21 discs might want instead to pick up The Iron Horse, one of its highlights, separately. It has plenty of extras as well.

I’ll sneak in an early sound film by recommending another Eureka! release of just about a year ago, Max Ophuls’ La signora di tutti (Everybody’s Lady). Made in italy in 1934, it was Ophuls’ first film after fleeing the Nazi regime. It’s a flashback tale, with the heroine recalling her life after a failed suicide attempt. It’s a new transfer and comes with a video essay by Tag Gallagher and a booklet.

Do yourself, your family, and your friends a favor

The 1994 edition of the “Giornate del Cinema Muto” in Pordenone, Italy, was as memorable as usual. There was the magical presentation of all the surviving Indian films (apart from a few short scraps), accompanied by a delightful and inventive chamber group of three Indian musicians. There were the silent westerns of William Wyler and the sophisticated 1920s features of Monte Bell. The main thread, though, was “Forgotten Laughter,” a celebration of known, little known, and unknown comedians. Their films were mainly shorts, and they provided us with a great deal of laughter.

Then came Wednesday, October 12, when we all witnessed history. A program entitled “Max Davidson” unspooled five two-reelers starring a short, middle-aged guy doing a beleaguered-Jewish-father shtick as well as such a thing has ever been done. We enjoyed four films before the program culminated with the immortal Pass the Gravy. I don’t think I’ve ever heard an audience laugh so loudly and continuously. Don’t assume this is anti-Jewish humor. This is pure Jewish humor, injected for just a few years into mainstream American slapstick filmmaking.

For some reason that year there was a poll taken to determine a film which would be encored at the end of the final evening. Pass the Gravy inevitably won, and we laughed just as hard the second time through. Mere words cannot convey why this film is so funny. It involves Max’s  daughter being engaged to a young man who lives next door with his father, proud owner of a prize rooster which ends up the main dish in a meal shared by both families. The running gag involves the young people trying to convey to Max what has happened without the young man’s father realizing what has happened. But no, you have to see it for yourself, preferably with friends and family about you. Like so many comedies, this one works best with an audience.

daughter being engaged to a young man who lives next door with his father, proud owner of a prize rooster which ends up the main dish in a meal shared by both families. The running gag involves the young people trying to convey to Max what has happened without the young man’s father realizing what has happened. But no, you have to see it for yourself, preferably with friends and family about you. Like so many comedies, this one works best with an audience.

It has taken 18 years for the surviving Max Davidson shorts, most of them supervised by Leo McCarey, to appear on video, a two-disc set, “Max Davidson Comedies.” Fortunately the job has been done well. The Munich Filmmuseum has assembled 13 shorts, 12 silent and one sound. Not all are as funny as Pass the Gravy, and Max plays only a supporting role in the earliest one. (The less said of the sound short, the better.) A booklet, in German and English, includes historical background and complete credits, including descriptions of the lost films. Davidson, by the way, had a long career playing bit parts, often uncredited. Often he played tailors, as in The Idle Class and The Extra Girl; during the sound era he appeared in The Plainsman and The Great Dictator, among many others. But for a short stretch at the Hal Roach studios he was the star.

At this year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival, “Max Davidson Comedies” shared the DVD prize for “Best Rediscovery of a Forgotten Film” with a parallel set put out by the Filmmuseum, “Female Comedy Teams.” The latter included more films shown in Pordenone in 1994.

Of course, the Davidson films were not forgotten by those of us lucky enough to have been in the Cinema Verdi in 1994. Two of them, including Pass the Gravy, were shown on Turner Classic Movies at 6 am a few years later, and we long treasured our VHS tape of that. But now everyone can share in this rediscovery.

A modestly pioneering early American film company

The Kalem company was one of those firms that cropped up during the early years of the American film industry, made shorts and short features for less than ten years, and disappeared without growing into one of the important Hollywood studios. Today it is perhaps best remembered for its 1913 biblical feature, From the Manger to the Cross, which was shot in Egypt and “the Holy Lands” at a time when filming abroad was unusual for  American film companies.

American film companies.

Kalem had pioneered the tactic of filming abroad earlier, however. Its series of films shot in Ireland, beginning with The Lad from Old Ireland (1910), are claimed to be the first American films shot outside North America. Eight of these survive, though often with missing sections. The Irish Film Institute has released a two-disc set including all of them, along with a feature-length documentary, Blazing the Trail: The O’Kalems in Ireland, directed by Peter Flynn.

The films were shot in the region of the Lakes of Killarney, taking advantage of famous locales like the Gap of Dunloe and Torc Waterfall (seen in Rory O’More, right). Intertitles include passages emphasizing that the scenes were shot in the very places where their historical and literary sources were set.

Unfortunately even the surviving films are not in good condition. Some are lacking their endings, and all are worn. The transfer has unfortunately cropped the edges, even though the accompanying documentary stresses that director Sidney Olcott’s main strength was his eye for compositions. Still, this set of films provides a rare example of fairly standard American films of the transitional period between the primitive and classical eras. Most classes in cinema history represent this transitional period mainly through the Biograph shorts of D. W. Griffith. This DVD provides a chance to show the more mainstream filmmaking of the early 1910s.

The accompanying documentary, Blazing the Trail, takes its title from the memoirs of Gene Gauntier, Kalem’s main scenario-writer and leading lady in its early period, including most of the Irish-based films. The film is perhaps a bit over-long for the topic, but it provides a rare in-depth look at a small company of the early era. The DVD set is available only from the Irish Film Institute’s website.

Dreyer re-reconsidered

The President (1920).

DB here:

I was late to the feast, but my contribution to the Dreyer site is now up, thanks to Lisbeth Richter Larsen‘s quick work. You can read it here.

Danish cinema was the first national cinema I studied, and Dreyer was my point of entry. I went to Copenhagen in 1970 to see his films for a little book I wrote in the Movie/ Studio Vista series. The manuscript was finished but never published because the series ceased. Good thing for me. I’d be embarrassed today if that book was still floating out there.

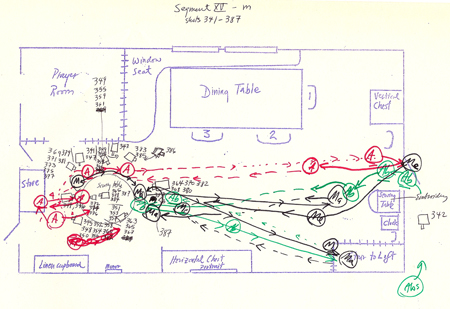

Kristin and I went back to Copenhagen in 1976 to re-watch the Dreyer oeuvre, and I saw the films with new eyes. I had learned a lot more about film analysis and film history, so I was able to see different things in his movies. Now obsessed with how films construct space and time, I drew up elaborate and clumsy plans of actor blocking, camera setups, and camera movements.

What? You don’t recognize this as a string of shots from Day of Wrath? I even notated actor movements offscreen (with dotted lines).

The result of all this fussbudgetry was a 1981 book on Dreyer. I think that some of the ideas there still hold up. But as I learned more about film history in the 1990s, I came to believe that some of my conclusions were off-base.

In particular, my treatment of Gertrud as a radical, deliberately “empty” film seemed tenuous. Influenced by minimalist cinema of the 1970s, especially that of Straub and Huillet (huge admirers of Dreyer), I pushed the case that at the end of his life Dreyer dared to make a movie that was by all ordinary standards simply boring.

Steadier heads tried to talk me out of it, but I clung to the idea. What can I say? I was young and stubborn.

As I studied more cinema of the 1910s, I began to see Dreyer’s career, and particularly his silent films, as tied in complicated ways to other films of that period–not least Danish cinema. For, as I’ve sketched here, Danish cinema of the 1910s was one of the richest traditions of “tableau” staging in Europe. I was able to put my ideas about the Danes’ achievements into clearer form in the last chapter of On the History of Film Style and in an invited essay on the Nordisk company published in a collection at the Danish Film Institute.

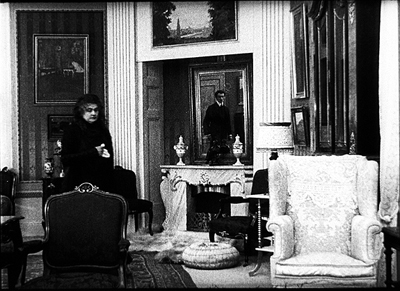

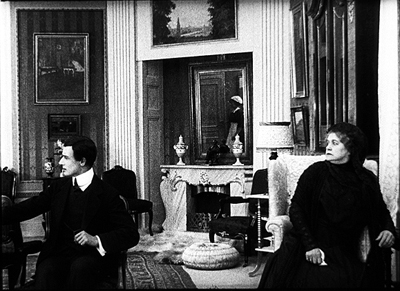

Like their peers in other countries, the Danes often stuffed their shots with furniture and props, in a riot of patterns and textures. Here is an example from Den Frelsende Film (The Woman Tempted Me, 1916). It survives only in fragments, but those fragments are in fine shape.

In addition, the Danes developed elaborate lighting patterns and complex, somewhat Gothic special effects. You can see these options in Ekspressens Mysterium (Alone with the Devil, 1914) and Doktor Voluntas (1915).

Above all there was the intricate staging in depth, often using mirrors. Here’s a seldom-seen example. In Under Blinkfyrets Straaler (Under the Lighthouse Beam, 1913), the father has died, and his wife and son meet in the parlor. A mirror catches them entering, in phases.

The mirror shows Hugo entering the room by moving straight and forward, but when he gets into the shot he comes in somewhat diagonally from the left.

After a moment of sitting in silence, mother and son turn as a maid enters. They look off left, but because we’ve seen Hugo enter in the mirror, we look to the center and see her reflection as she shuts the door.

The maid brings the widow a letter from her other son, Robert. Hugo, fretful, departs and in the mirror we see him look back at his mother.

Or does he? The angle of his glance makes sense compositionally: In reflection Hugo seems to be meeting his mother’s eyes, left to right. But in my first frame, he advanced into the room by looking straight ahead. If he looked straight into the room again now, he’d be looking more or less at us, not at his mother. So I suspect that in my last frame, the actor is actually not looking directly at the actress but off at an angle. He has been directed to this position to allow the mirror to create an artificial, but highly readable, image.

The novice Dreyer, I realized, didn’t indulge in such tableau trickery. His first two films, The President (made in 1918) and Leaves from Satan’s Book (made in 1919), are quite different from the norms that ruled his local cinema. By the time he came to directing, he was more oriented toward analytical editing and fairly flat staging than were the old guard. In this regard he was closer to a younger group of filmmakers emerging at the same time in other countries: Gance, Lang, Murnau, Joe May, and many others, along with Americans like Ford, Walsh, et al. So my newest take is that Dreyer is part of a generation of directors moving toward an editing-driven cinema and away from the tableau style. This idea in turn helped me see Gertrud in a more convincing light.

If you want the argument in full, you can check it on the Dreyer site. The lesson for me is twofold. (A) Dreyer is inexhaustible. (B) The more you learn about cinema (and about life), the more you can see in films that you think you have already understood.

The only book in English surveying the cinema of Dreyer’s elders is Ron Mottram’s indispensable The Danish Cinema before Dreyer (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow, 1988). It doesn’t consider the dual traditions of staging and editing, but it offers a very thorough history of studios, directors, and genres, and mentions some stylistic patterns. The article I referred to is “Nordisk and the Tableau Aesthetic” in Lisbeth Richter Larsen and Dan Nissen, eds., 100 Years of Nordisk Film (Copenhagen: Danish Film Institute, 2006), 80-95. This gorgeous book can be ordered from the DFI shop;I’ll be adding my essay here some time this summer.

For more on the tableau tradition, go to other blog entries here and here and here and here. On the emergence of continuity editing, chiefly in the US, try here and here and here. More detailed treatments are in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, On the History of Film Style, and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging.

I’m grateful as ever to Marguerite Engberg, Dan Nissen, Thomas Christensen, and Mikael Brae for their help in my research on Danish silent film.