Archive for the 'Directors: Eisenstein' Category

The ten best films of … 1928

La passion de Jeanne d’Arc

Kristin here:

Time for our twelfth annual alternative to the usual list of the ten best films of the current year. Instead, I offer a list from 90 years ago, in part for fun and in part to call attention to some lesser-known classics that are worth discovering. (See here for our lists from 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, and 1927.)

The year 1928 marked the triumphant conclusion of the silent cinema. Very few sound films were made that year, and those that were often included only music, perhaps sound effects, and occasionally some passages of dialogue. Sound was not innovated because the silent cinema was in aesthetic decline. Quite the contrary. It was initially an enhancement that film-industry people assumed would make films more lucrative. In most cases the “talkies” that followed over the next few years were inferior to their silent predecessors, in part due to the limitations of the new sound technology. Those who opposed the addition of sound could point to the films of 1928 as evidence that the young art form had already reached a peak of perfection that was being tarnished by the addition of recorded sound.

In compiling this year’s list, I came up with eight titles that seemed unquestionably to belong on it. There were another six on a list of possibilities for the final two slots. More than in past years, this year gave me a chance to go back and rewatch films I hadn’t seen in a long time, in some cases since graduate school in the 1970s. Some held up well, some not so much. In a few cases, restorations made since my first viewings revealed new strengths in films I remembered from poor prints.

As always, there are films that have been lost but which plausibly could have filled out the list, most notably Ernest Lubitsch’s The Patriot and F. W. Murnau’s 4 Devils.

First, the eight obvious choices, in no particular order apart from #1.

1. La passion de Jeanne d’Arc.

Not every year includes a film that is not only one of the tops of its year but of all cinematic history as well. Carl Theodor Dreyer’s final silent film is one such masterpiece.

Jeanne d’Arc seamlessly blended the stylistic traits of the great artistic film movements of the 1920s, German Expressionism, French Impressionism, and Soviet Montage and made something new and unique of them.

Expressionist designer Hermann Warm’s past credits had included two films that have featured in these lists, Robert Wiene’s Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari and Fritz Lang’s Die müde Tod. Warm collaborated with French theatrical designer Jean Hugo to create spare, white, off-kilter sets that focus our attention on the spiritual drama. Fast editing conveys subjectivity, as in the scenes where Jeanne is threatened with torture and where the citizens are suppressed when they riot after her execution. Rudolph Maté’s cinematography is startlingly dependent on close shots, particularly on the face of Jeanne, played by Renée Falconetti in one of the most intense and affecting performances in any film.

The steady progression of the action condenses days of trial testimony into one apparently continuous story. Between the sets and this inexorable march toward Jeanne’s martyrdom, there is a sense of both spatial and temporal disorientation that focuses our attention intensely on the central conflict.

Until 1981, prints of Jeanne d’Arc were indistinct and incomplete. A pristine print that restored the original visual quality and detail was found in Norway. (The film was among the early ones to be shot on panchromatic film stock without the actors’ using makeup. The result is a detail of texture in the faces that enhances the performances tremendously.) This print is the basis for the Criterion Collection’s edition of the film.

It’s a film that one can see over and over and still be overwhelmed at the originality and intensity of Dreyer’s vision. We saw it projected last November in Houghton, Michigan, with Richard Eichhorn’s recently composed accompaniment, “Voices of Light,” essentially an oratorio and film score rolled into one. We were somewhat trepidatious about whether the score would be distracting, but it proved very effective. Once again, I was reminded of how great this film is. (“Voices of Light” is an optional accompaniment on the Criterion edition linked above.)

2. October

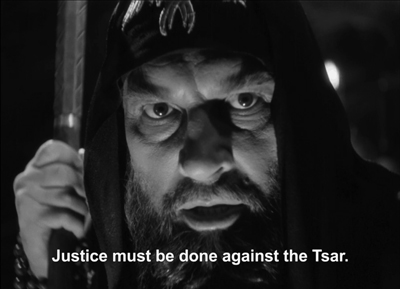

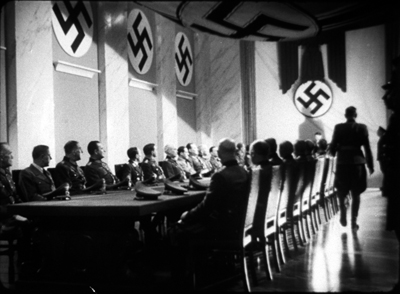

If Jeanne d’Arc gains intensity through a nearly claustrophobic treatment of space, Sergei Eisenstein creates an epic tenth-anniversary celebration of the 1917 Revolution in his October (finished and released a year late).

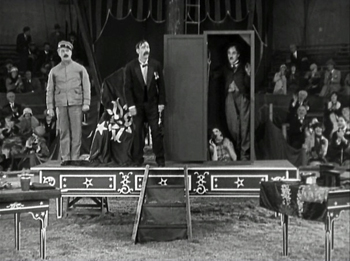

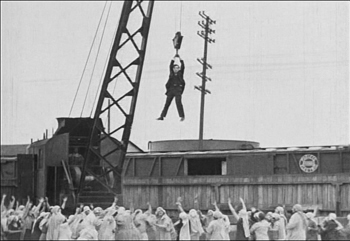

Perhaps the most extreme example of Soviet Montage’s frequent avoidance of a single protagonist, October cuts among a wide variety of the people involved in the revolution. Workers pull down a statue of the Tsar. Lenin speaks at Finland Station. Kerensky and his officials luxuriate in their Winter Palace headquarters. Sailors wait on the Aurora battleship. Elderly citizens try to protect the specious February Revolution. Female soldiers are summoned to protect the Palace from the attacking Red forces. Looters steal bottles from the Tsar’s wine-cellar. The result is a sort of patchwork collage of the Revolutionary events leading up to the storming of the Winter Palace and the attack itself, with a slow build to an exultant climax as the Red forces triumph.

Eisenstein was given extraordinary access to the locales of the actual events, so that the vast halls of the Winter Palace and the trappings of royalty (Fabergé eggs and fancy crystal liquor bottles) give a sense of reality rare in fictional reenactments. (There was a time when October was plundered for “documentary” footage of events which had not been recorded by cameras at the time.) He used the settings to ridicule the anti-revolutionary forces, as when young cadets are summoned to help fight the Red forces and are dwarfed by the muscular colossi that line one area of the Palace’s exterior (above).

The film also represents Eisenstein’s experiments with “intellectual montage,” where he attempts to convey ideas strictly through juxtaposing series of images. In belittling the phrase “for God and country,” he tries to reduce the notion of “God” to absurdity by linking a long series of increasingly exotic depictions of deities from different religions.

Whether Soviet audiences of the late 1920s could make anything of such passages is impossible to know for sure, but one suspects that some of them would have been incomprehensible. Still, it is exciting to see an artist playing with such possibilities. Certainly the technique lived on, whether from the simple juxtaposition of cackling hens and gossiping women in Lang’s Fury or Jean-Luc Godard’s dense, often impenetrable strings of images, especially in his political films.

October exists in many versions. Beware the heavily cut versions under the title Ten Days That Shook the World. These images were taken from the 2008 release by the Soviet Ruscico company in its “Kino Academia” series.

3. Spione

Despite the widespread enthusiasm for Lang’s Metropolis, his other big films of the 1920s–Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler, Die Nibelungen (Siegfried and Kriemhilds Rache), and Spione–seem to me better. Metropolis is perhaps flashier in its design and conception and certainly very entertaining, but it’s also sprawling and implausible and essentially pretty silly.

Spione, on the other hand, has a tight, fast-paced narrative. It’s sort of Dr. Mabuse boiled down to one feature instead of two, and with the villainous Haghi (again played by Rudolf Klein-Rogge) as a banker secretly masterminding a spy ring rather than a gambling racket. There are no great “heart vs. hand” themes here–just a rattling good tale stylishly presented. Expressionism has disappeared in favor of a streamlined look (above), and Lang’s editing has sped up since Mabuse.

There’s not much point in detailing the plot here, since it would involve too many spoilers. Discover it for yourself if you haven’t already.

Spione circulated for years in the truncated American release version, which is how I first saw it. A 2004 Murnau Stiftung restoration of the complete version was a revelation, not only for its more complete narrative but for its superb visual quality. It’s a feast of shots that only Lang could have composed (above and bottom). These frames are from the Eureka! DVD, but the company has subsequently released it in dual format DVD and Blu-ray. Kino Classics has also released it in Blu-ray. The same company has put out a boxed-set of all Lang’s silent films (including Die Pest im Florenz, directed by Otto Rippert from Lang’s script). We were given this recently and haven’t had time to explore it, but it looks like a must for any fan of Lang.

4. L’Argent

Marcel L’Herbier makes his second and final appearance on this annual list with his epic adaptation of Emile Zola’s L’Argent, updated to contemporary Paris. (See the 1921 entry for El Dorado; I also wrote about the Flicker Alley releases of the restored versions of L’Inhumaine [1923] and Feu Mathias Pascal [1925].)

Inspired by Abel Gance’s even more epic Napoléon (1927), L’Herbier set out to make a film that would require a large budget. To obtain that, he made a deal for his own company, Cinégraphic, to co-produce with the mainstream studio, Cinéromans. The result contains brightly lit sets of big banks and expensive apartments, as well as shots made in the Paris Bourse over a three-day weekend (above). L’Argent also had an all-star cast. It included Brigitte Helm and Alfred Abel fresh off Metropolis, thanks to the German distributor, UFA. It also meant that Cinéromans tampered with the film, re-editing and shortening it.

Given L’Herbier’s reputation as an aesthete and an avant-garde filmmaker, L’Argent was dismissed by many at the time as a purely commercial endeavor. It remained unseen and hence virtually forgotten for decades. A screening at the New York Film Festival in 1968 surprised and impressed the spectators. The real recognition of the film as a major artwork came, however, in 1973, when critic and theorist Noël Burch published his monograph, Marcel L’Herbier (Paris: Seghers, 1973). In it he hailed L’Argent as a masterpiece, devoting the entire final chapter to an analysis of it. Burch also wrote the entry on L’Herbier for Cinema: A Critical Dictionary: The Major Film-makers ([New York: Viking Press, 1980], Vol. Two, pp. 621-28), edited by Richard Roud; again Burch devoted much of his text to L’Argent.

I have expressed my reservations about L’Herbier’s films in earlier entries, but for me L’Argent is the big exception: stylistically daring and narratively engaging. Perhaps adapting Zola led L’Herbier to make a more conventionally suspenseful film than usual. Referring to the French Impressionist movement in general, Burch wrote, “L’Argent undoubtedly marks the end of the period of experimentation, since it is itself the culmination of all these experiments–not just L’Herbier’s, but those of the first avant-garde and even, to a certain extent, of the entire Western cinema (with the exception of the Russians)” (Roud, pp. 624-25).

The story involves two powerful bankers who spar for control of one large bank’s standing on the stock market. One, the villainous Saccard, aims to send a famous aviator on a perilous flight across the Atlantic to promote his bank’s oil holders in Latin America–while seducing the aviator’s wife during his absence. The other, Gundermann, tries to thwart him by buying up shares of his rival’s bank and then selling them to cause a drop in the bank’s value.

In portraying all the complex machinations going on, L’Herbier adopts a restless camera, frequently moving among and around characters rather than following them. The most striking example comes early on, when an underling comes to visit Gundermann and waits in an odd, unfurnished room decorated with a map of the world. As he looks around, the camera circles him until a servant unexpectedly appears through a door and escorts him in.

The odd distortions in these shot exemplify another cinematographic technique that was in increasing use during the late 1920s: conspicuous wide-angle lenses. On the left below, Saccard is nearly dwarfed by one of his telephones, while on the right the scene of the aviator’s departure makes the plane’s wings jut into the foreground and extend far into the background.

There are some subjective moments, carrying forward the tradition of French Impressionism. Yet for the most part the restless camera, the distorting lenses, the odd angles (see the top image of this section), and the unusual crosscutting are not subjective, which makes this an atypical Impressionist film. Instead they suggest the unnatural, disconcerting world of capitalism, of money and those who struggle over it. Perhaps by minimizing character psychology and striving to represent more abstract concepts, L’Herbier briefly carried Impressionism to a more political–and dramatic–level.

In 2008, L’Argent was released on DVD by Eureka! in the UK as a “Special 80th Anniversary 2 x Disc Edition.” The source material was a beautiful fine-grain positive struck from the original negative, with something close to L’Herbier’s original intended cut. It includes Jean Dréville’s Autour de “L’argent,” a 40-minute making-of (surely one of the first of its type), recorded during the original production. The DVD is still in print and is, as far as I know, the only release of this restored version.

5. Steamboat Bill Jr.

This was the first Keaton film I ever saw, and I immediately became a fan. (The director is credited as Charles Reisner, but we all know that Keaton was primarily responsible for the direction of his films of this period.) It’s not as good as The General (what is?), but it beats out The Cameraman, Keaton’s other feature of this year, by a nose.

Keaton plays the dandified son of a gruff steamboat owner. He returns home from school and gets put into working clothes by his father, whose deteriorating steamboat is competing for tourists with a larger, newer boat. Naturally young Bill is in love with the daughter of the other steamboat’s owner. The action mainly consists of Bill, Sr. trying to prevent Bill, Jr. from clandestinely meeting his girlfriend.

There’s lots of humor along the way to the climax, in which a huge storm hits the town. It’s a classic sequence of Keaton pulling variant gags on the situation of being in a high wind (above) and surrounded by collapsing buildings and flying objects. Perhaps Keaton’s most famous, and dangerous, gag comes when he pauses in front of a house’s façade, which tears loose and falls straight down on him–with a window sparing him from being crushed.

Reportedly the top of the frame missed his head by six inches, but we know Keaton was a little crazy in how far he would go for a laugh.

Steamboat Bill, Jr. was the last film Keaton made with his own production company. The Cameraman was made at MGM, and though it is very good, thereafter his career slowly declined after his move to that studio. This will, alas, be the last Keaton film represented in this series.

6. The Circus

Coincidentally, The Circus was the first Chaplin film I ever saw. I happened to take my first film course at the point where Chaplin had re-released The Circus, accompanied by a new musical score he composed himself. (Skip, if you can, the added opening, with Chaplin singing a maudlin song over an excerpt from later in the film.) The re-release was 1969, though I must have seen it in 1970 at Iowa City’s art-house, the Iowa. (Also coincidentally, my father managed the Iowa when he was at the university there on the GI bill in the years immediately after World War II. He was dating my mother at that point, and there she saw Day of Wrath. Hence when David and I became a couple in the mid-1970s, she understood what the book he was currently working on was about. But I digress.)

The print I saw at the Iowa was pristine.

Up to that point, The Circus had been unavailable to most viewers, though I suspect bootleg prints circulated among collectors. It’s among the least known of Chaplin’s features, and it’s still hard to see. There’s a Park Circus DVD available in England, consisting of the re-release version equally in mint condition; that’s the one I’ve taken these illustrations from. More recently the film has been released as a Blu-ray/DVD combination. There is also an Artificial Eye Blu-ray available, which gets high marks from DVD Beaver. I haven’t seen this and don’t know whether it’s the re-release version or the original.

Chaplin plays his Little Tramp character, introduced wandering around the sideshow attractions near a circus. Mistaken for a pickpocket, he flees among the booths, occasioning a brilliantly staged triple scene in a hall of mirrors. When he first enters it, he is alone and struggles to figure out how to exit. A short time later, pursued by the pickpocket, the two stumble into the room, and a comic chase ensues (above). Finally, a cop is chasing Charlie, who tries to confuse him by luring him into the mirror maze. It’s a set of gags that builds, with the figures popping unexpectedly into the foreground when we had assumed that the real actors were in the depth of the shot. Each scene in the maze is handled in a single take from the same camera setup.

The flight from the cop leads the Tramp into a failing circus cursed with a group of highly unfunny clowns. Charlie inadvertently and unwittingly becomes a sensation for his antics, including his invasion of a magician’s act.

The cruel circus owner hires him, supposedly as a prop man, and the show becomes a huge success. Charlie falls for the maltreated daughter of the owner, who in turn becomes smitten by a handsome tightrope walker. Trying to impress the daughter, the Tramp goes on when the tightrope walker fails to show up one day. The result is a classic extended scene of Charlie on the high wire, executing a series of comic moments before the whole thing is topped off by a group of monkeys who escape and end up swarming over him as he struggles to keep his balance.

I hope now that The Circus is becoming more available, it can takes its place beside Chaplin’s other features.

[December 29: Thanks to Valerio Greco for alerting me that a restoration of the original version of The Circus is underway in Bologna, to be released by The Criterion Collection.]

7. The Docks of New York

I’ve already written about this, Josef von Sternberg’s final silent feature, in 2010 on the occasion of The Criterion Collection’s release of it alongside Underworld and The Last Command in an essential box-set. The six films von Sternberg made with Marlene Dietrich after she came to Hollywood generally get more attention than any of his silents. If I were allowed three of his films for a proverbial desert-island situation, I would take Underworld, The Docks of New York, and Shanghai Express.

Docks is a concentrated dose of the atmospheric cinematography the director is famous for, in this case employed to create the grungy settings of the film. In the opening, the oil and sweat on the stokers’ bodies (above) is palpable, and the fog, hanging nets and lanterns, and smoke of the dockside sets establish the sleezy, hopeless milieu that drives the heroine to attempt suicide.

Apart from the impressive visuals, the film gains much of its appeal from its two central performances. Betty Compson manages to gain our considerable sympathy for “the Girl” in a remarkably short time, and she has to–the film is only 75 minutes long and she spends her first onscreen appearances unconscious after her near-drowning. George Bancroft, known mostly for supporting roles in westerns, came into his own as the protagonists of three von Sternberg films–including Thunderbolt but not The Last Command. Here he again plays the big lug with a well-hidden heart of gold.

Unfortunately the von Sternberg silents set from The Criterion Collection is out of print. Track it down somewhere or hope for a Blu-ray release.

[December 29: Peter Becker of The Criterion Collection tells me that, although a Blu-ray release is not yet scheduled, there is a good possibility that it will happen.]

8. Storm over Asia

After Mother and The End of St. Petersburg, Storm over Asia (the original title translates as “The Heir of Genghis Khan”) is the last of Vsevolod Pudovkin’s three great silent features. Unlike the first two, it is set in Mongolia. The Soviet industry officials were concerned to portray the Revolution in the various other countries that along with Russia made up the Soviet Union.

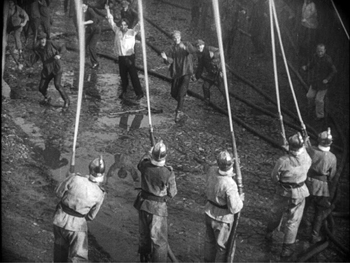

The story takes place during the Civil War years that followed the Revolution. A young Mongolian peasant tries to sell a valuable fox fur at a trading post, but the British dealer cheats him. The peasant strikes him and is forced to flee into the mountains, where he joins the Red partisans fighting the British imperialists. (This does not follow historical fact, since the British occupied parts of Siberia and Tibet, but not Mongolia. In reality, for a brief period in 1921, White Russian forces drove out the Chinese from Mongolia. In response, the Red Army moved in, supporting the Mongols in their quest for independence.)

The British shoot the protagonist but discover on him a document that seems to identify him as the heir of Genghis Khan. So they set him up as a puppet ruler in order to control the local population. Eventually he rebels and leads a storm-like assault that defeats his oppressors.

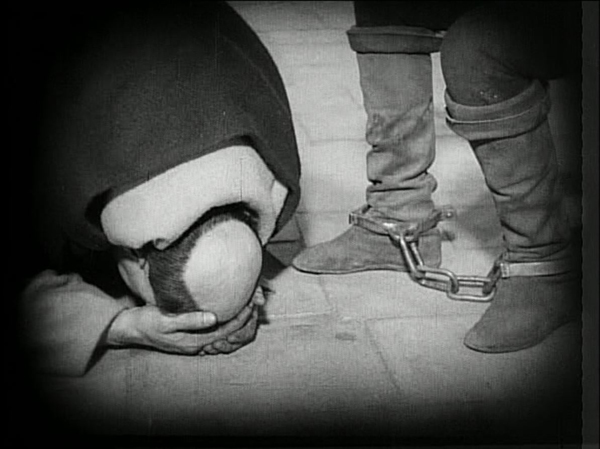

Storm over Asia uses many of the Soviet Montage devices that by 1928 were fairly conventional. For instance, there are many rapid, rhythmic alternations of shots. When the fur trader reacts angrily against the protagonist’s resistance to being cheated, brief shots of his angry call for troops to capture the young man alternate with shots of a drum being beaten. The final “storm” battle uses rapid montage as well. There is also the usual visual symbolism mocking the enemy, as exemplified by the empty officer’s uniform in the shot above.

Early Montage films tried to do away with a single central character in favor of a focus on the masses. October, for example, has no main hero. In Storm over Asia, though, the story arc is definitely crafted around the Mongol’s growth into a rebellious leader of his people. We will see Eisenstein opting for a central identification figure in Old and New (1929).

My illustrations were taken from the old Image release, apparently no longer available. The Blackhawk print has been released by Flicker Alley.

Those are the eight films I put on my “top” list. I thought of stopping there, but the number ten is sacred for such lists, plus part of the point here is to throw a spotlight on lesser-known films.

I gathered a second group of films that might claim the remaining two slots. These were mostly films that were already hallowed classics when I was in graduate school: King Vidor’s The Crowd, Jean Epstein’s La chute de la maison Usher, René Clair’s The Italian Straw Hat, and Victor Seastrom’s The Wind. Beyond that there were the more recently rediscovered and much admired film, Paul Fejos’ Lonesome and the still little-known The House on Trubnoya, by Boris Barnet.

Oddly, the three American films on this list have some distinct similarities. The Crowd and Lonesome are surprisingly parallel. Lonesome follows two lonely people in New York finding each other and falling in love in one hectic day. The Crowd starts with a somewhat similar situation–both even involve dates at Coney Island–but follows the couple through several years of happy times and misfortune during their marriage. The Wind is less realistic, dealing with a sensitive young woman who travels to the west and, plagued by the incessant wind and a real or imagined rape, slips into madness. All three strive to reject the conventional Hollywood romance. Unfortunately all three, however admirable for most of their plots, lead to abrupt, implausible happy endings.

I saw The Italian Straw Hat in my graduate-school days and found it remarkably unfunny, given its reputation. Returning to it now, I still find the first two-thirds largely devoid of humor. (The dance scenes during the wedding party seem interminable, with no little vignettes or gags among the characters at all.) The last portion picks up, but on the whole it’s hardly the model French farce it is held to be. Certainly Clair made a leap forward in skill and sophistication in his early sound films. (Les deux timides, also 1928, is no doubt a better film.)

The Italian Straw Hat probably owes its classic standing in part to the fact that the Museum of Modern Art acquired and circulated it early on. Curator and critic Iris Barry adored it and lauded it in a 1940 essay (reproduced in the booklet included in the Flicker Alley release.) I wonder how many others of the films considered classics have become so because they were among the few silents available in the decades before the 1960s, when film studies and archival curatorship began to be more comprehensive. Knowing the range of international films we know now, would these films have become quite so highly respected above others? I found myself reluctant simply to fill out my list with old standards. The choice was difficult.

Wanting to avoid carrying on the older canon at the expense of more recently rediscovered films for at least one of my films on this list, I always try to include a little-known but worthy film here. This year there is only one (if you don’t count L’Argent), and that is Barnet’s The House on Trubnoya.

The final slot goes to Epstein’s The Fall of the House of Usher. I have always considered this a somewhat tedious film, but the restoration of the film’s full length and improved visual quality in the Epstein box-set released in 2014 by La Cinémathèque Française makes it far more interesting and effective.

So here is the completion of my list.

9. The House on Trubnoya

Boris Barnet was a member of Lev Kuleshov’s school in the early years after the revolution. He played a major role in Kuleshov’s The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr West in the Land of the Bolsheviks, and he began directing films on his own with the wonderful serial, Miss Mend. He made more films, and some others may show up in our coming lists. Right now, there’s The House on Trubnoya.

The House on Trubnoya is included in Flicker Alley’s major DVD set, “Landmarks of Early Soviet Film.” (I can’t believe that we didn’t feature this on our blog, but it includes eight major Soviet films of the silent era.) The copy on the back of the box describes Barnet’s film as “often described as one of the best Soviet silent comedies.” I’m not sure that’s a major distinction, though Kote Miqaberidze’s Georgian satire My Grandmother (1929; available on DVD and Fandor’s Amazon streaming site) is quite funny, as is Ivan Pyriev’s The State Functionary (aka The Civil Servant; not, as far as I know, available on home video). But The House on Trubnoya is my favorite among the comedies I’ve seen.

It’s a satire on middle-class citizens’ maltreatment of their servants, though it doesn’t become Soviet-style preachy until well into the story. The film begins by setting up the titular house (on a well-known street in Moscow). We see it via its staircase and landings in the morning, rendered in a vertical view that looks startlingly like an iPhone image (above). It also recalls the seven levels in the staircase elevator shot climbing upward to 7th Heaven, though who knows whether Barnet had seen that by the time he planned his film. The residents of the various apartments emerge to use the communal stairway as a junkyard and work area, dumping trash, splitting firewood, beating curtains, and generally abusing the rules of the building, as one conscientious young Party member points out.

We are introduced to a barber, whose lazy wife makes him do all the chores. Then suddenly we’re with a professional driver with his own car. Just as suddenly we’re watching a peasant girl chase her runaway duck through a maze of traffic and nearly get hit by a tram. As the driver brakes hastily and jumps out to see if she’s hurt, there’s a freeze-frame.

A narrating title declares, “”But wait, we forgot to tell you how the duck ended up in Moscow.” Reverse motion leads to another title, “A day earlier.” A flashback to the heroine’s comic departure from a train station in the middle of nowhere shows the very uncle whom she is going to Moscow to visit arriving at the station just after she has left. Finding herself lost in Moscow with her duck, the heroine gains employment as a put-upon maid serving the barber and living in the house on Trubnoya. Her political awakening and the rehabilitation of the House on Trubnoya form the rest of the plot.

The House on Trubnoya is, in short, an imaginative, clever, and funny Soviet Montage film. Barnet’s other films are worth exploring as well. Check out The Girl with the Hatbox from 1927; it didn’t make last year’s top items, but it was on the long list.

10. La Chute de la maison Usher

Jean Epstein, who was probably the finest of the French Impressionist directors, has figured in these ten best lists before, in 1923 for Cœur fidèle, in 1924 for the little-known L’affiche, and 1927 for his masterly La Glace à trois faces.

I have long considered La Chute de la maison Usher interesting for its use of German Expressionist-inspired sets, but the fuzzy, incomplete prints that for decades were the only available versions made it difficult to enjoy. The restored version on the complete DVD set of Epstein’s works, which I discussed here, makes it far more interesting.

Taking its slim plot from Poe, the film follows a visit by an elderly man to the isolated castle of his old friend, Roderick Usher. Usher is painting a portrait of his beloved wife, but it is soon made clear that each time he presses the brush to the canvas, a little of her life is drained away–though the local doctor is mystified by her decline.

The film retains some of the traits of Impressionism, as when Madeline’s reaction to the effects of her husband’s painting are rendered in a superimposition of negative and positive images of her face.

The film has a minimal plot, but its focus is largely on experimentation in creating an eerie atmosphere. Shots of books falling in slow motion from their shelves, of curtains blowing in a cold wind that seems perpetually to invade the house, of frogs copulating in a nearby pond, and of the Expressionist-derived decors contribute less to a linear plot than to a mood of undefined menace.

The castle’s exterior is represented by obvious cardboard models, which tends to undermine the effect created by the interiors. The cheapness of these models is particularly noticeable in the climactic scene of the destruction of the house. This is unfortunate, but one must give Epstein credit for having done so much with so little.

This will be Epstein’s final appearance in our “Ten Best” lists, but I would like to call attention to his other 1928 film, Finis Terrae, the first of what the Epstein box-set collects as his “Poémes Bretons.” These are less Impressionistic, though Finis Terrae has a few impressive subjective shots. They are more realistic and poetic, largely involving the sea.

As I wrote at the beginning, 1928 was part of the period when the American industry was on the cusp of making sound standard in its films. Other national cinemas followed at various paces. One film that did not quite make my top-ten list demonstrates what must have worried film theorists and critics–and no doubt some filmmakers.

The restored version of Lonesome includes some dialogue sequences in a film otherwise accompanied by recorded music. There is an enormous contrast between the silent and sound footage. The story is largely told visually, but the dialogue scenes, clearly done in a sound-proof studio, are delivered in a stilted fashion by the young actors who are otherwise so casual and lively. The prospect of whole films being made in that fashion clearly disturbed lovers of films like La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc and Steamboat Bill, Jr. Watching Lonesome gives a dramatic insight into this slice of cinema history–a period that fortunately lasted only a few years as the technology improved and as filmmakers increasingly managed to make sound films that were just as imaginative, artistic, and engrossing as their silent predecessors.

January 6, 2019: Thanks to Docks of New York fan Tony Lucia for a correction on that section.

Spione

Eisenstein makes a scene: IVAN THE TERRIBLE Part II on the Criterion Channel

For Yuri Tsivian

DB here:

Everyone knows Eisenstein as a theorist and practitioner of something called montage, which in his hands comes to mean a lot of things. But he was no less interested in what he called expressive movement. He believed that the viewer could be aroused by dynamic physical action that carried powerful feeling. Expressive movement pervades the set-pieces of his silent films. On the Odessa Steps of 1925’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), we get the robotic descent of the Cossacks opposed to the agitated flight of the citizenry, and the street massacre of October (1927) makes even mechanical bridges seem ferocious. And less flamboyant moments, from the animalistic antics of the spies in Strike to the weeping masses at the Odessa quai, are full of expressive postures, gestures, and facial behavior. Eisenstein sculpts the human body so as to project extreme states of feeling.

That effort is on full display in Ivan the Terrible Part II, which I discuss in our current entry on FilmStruck‘s Criterion Channel. My commentary, grounded in a single sequence, builds on an analysis I offered in my book The Cinema of Eisenstein, but the clever experts at Criterion have created dynamic juxtapositions through cuts and replays that I couldn’t summon up in print. I try to show how, as ever, Eisenstein sacrifices bland realism of behavior to something more sharp and intense. In this “theatrical” film, he goes beyond line readings to offer maniacally heightened physical action–a sort of deadly serious, amped-up, live-action cartoon. Eisenstein worshipped Disney, after all.

Today’s blog entry bounces off that installment to show the connection between expressive movement and the most banal stock-in-trade of cinema: the standard scene of two people talking to each other.

Lessons with the master

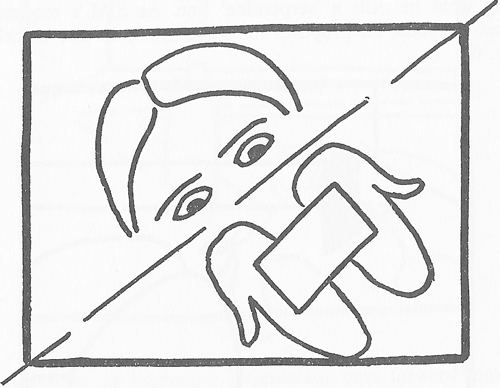

A sketch from Eisenstein’s lectures on Crime and Punishment.

Eisenstein’s silent films seek a “dramaturgy of film form” that would surpass traditions of theatrical and novelistic storytelling. This mission, which creates a sort of epic cinema, left an odd gap. From Strike (1925) to Old and New (1929), his films are notably lacking in one stock ingredient. He seldom creates sustained scenes showing a developing conflict between two characters in an ordinary setting–a parlor or office or street. With few exceptions, Eisenstein “explodes” even standard scenes by cutting to action elsewhere. The factory owners of Strike chortle over drinks while, thanks to parallel montage, the workers are rounded up by soldiers on horseback.

Other Soviet Montage directors were willing to work up theatrical scenes: Pudovkin has a Hitchcockian suspense sequence in Mother (1926), while Kuleshov turns the second stretch of By the Law (1926) into a Kammerspiel. But Eisenstein’s urge to splinter face-to-face dramaturgy came from a different sense of theatre–that “Theatricalism” of his teacher Meyerhold, who saw the stage not as the copy of a real space but as an arena for performance. Eisenstein extended this idea by thinking of the shot and the sequence as an arena for action, specifically expressive movement.

By the 1930s, Eisenstein may have sensed that sound cinema would make films more theatrical in a traditional sense. Sequences would be more concentrated in one locale and focused on a few characters. Crosscutting, a mainstay of silent film, would become rarer. He accordingly began to ponder creative ways of filming two-handers. In his courses at the Soviet film school VGIK he explored ways to intensify dramatic face-offs without interruptive cutting.

These lectures are inspiring because they show you a filmmaker thinking through problems and tracing how one solution leads to new problems. A soldier returns from the war to find his wife pregnant with another man’s child. With his students Eisenstein spent weeks scrutinizing options for performance, shooting, and cutting this simple situation. A banquet is held for Dessalines, Haitian hero. How do you film his realization that his hosts are planning to kill him? How do you present the bedroom of Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, or the claustrophobic apartment of Thérèse Raquin? How do you stage Raskolnikov’s murder of the pawnbroker in Crime and Punishment…and do it in one fixed shot? (You don’t hear much about Eisenstein the long-take man.)

The results of this line of thinking show up in his films. Alas, we have only glimpses in what remains of Bezhin Meadow (finished 1937; banned, now lost). And Alexander Nevsky (1938), still conceived on a broad canvas, doesn’t really face up to the demands of intimate scenes. It’s only in both parts of Ivan the Terrible (1944, 1946) that we can see how Eisenstein plunged into doing what most directors do: filming uninterrupted scenes of people talking to one another.

Needless to say, he doesn’t do it the way they do.

The tsar in your lap

Expressive movement is involved, but so too are other stylistic strategies. For one thing, Eisenstein rethinks analytical editing. Characters need not face one another; they can be turned to the viewer and interact by shifting their eyes. No need for over-the-shoulder reverse angles either; you can cut in or out along the camera axis. Both strategies are introduced at the start of Ivan the Terrible Part I.

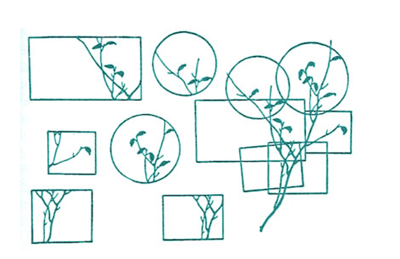

More elaborately, Eisenstein may dissect a scene through what he called in his VGIK classes the “montage unit” (uzel), a cluster of shots taken from roughly the same orientation. These yield chunks of space that overlap when edited together. He diagrammed this procedure in an illustration of cherry blossoms he found in a Japanese drawing manual.

This collage of overlapping bits, anticipating Hockney’s photo paste-ups, is actualized on film in the Pskov sequence of Ivan Part I, as I discuss in my book.

Another strategy is the use of depth. While Renoir, Welles, William Cameron Menzies, and other directors were trying out deep-space staging and depth of camera focus, so was Eisenstein. Well before Welles, he and his Soviet colleagues offered grotesque wide-angle shots. Below, Old and New and China Express (Ilya Trauberg, 1929).

More rigorously, Eisenstein began to think of how to arrange his scenes along the camera axis. True, a great many of his scenes are staged laterally, with figures arrayed from left to right.

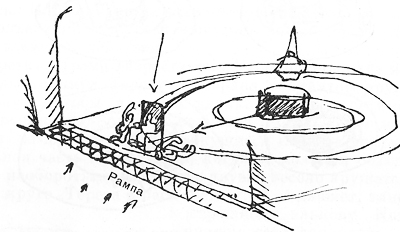

But others, particularly those at a dramatic pitch, are staged in depth. And what distinguishes Eisenstein, to my mind, is a strikingly confrontational or immersive approach. You can see it emerging in the VGIK exercises, notably in his stage designs for a hypothetical production of Thérèse Raquin. Here the paralyzed, speechless Madame Raquin terrorizes the murderous lovers with her glittering eyes. Eisenstein wanted the actors to perform on a turntable that would show her chair rotating to spy on the couple’s affair from different vantage points. At the climax, when the guilty lovers commit suicide, Madame Raquin’s chair was to break from the circle and propel itself forward, so that she would be staring furiously into the audience.

The footlights, marked with arrows, indicate that the effect is exaggerated by horror-style lighting from below.

This effect might look gimmicky, a sort of stage equivalent for what we can easily accomplish in cinema. Don’t directors often heighten the drama by making their actors advance to the camera? But in many scenes Eisenstein moves his players toward us, then cuts further backward, letting axial cuts create an unfolding foreground. A new playing space is opened up, and the actor is free, or rather compelled, to thrust further forward, sometimes into uncomfortably big close-up.

The Soviets called axial cuts “concentration cuts,” and we mostly find them used to enlarge, usually shockingly, something far off. But Eisenstein creates something more risky.“In my work,” he wrote, “set designs are inevitably accompanied by the unlimited surface of the floor in front of it, allowing the bringing forward of unlimited separate foreground details.” In principle the camera can back up again and again, and the foreground could unfold forever.

The result sometimes yields direct address, as in my Criterion Channel example, but more generally it creates a sense of characters passionately engaged in clamping their will upon others and hurling themselves not just at one another but at us. Characters confide in the camera, and–long before all today’s talk of “immersive” cinema–the camera is us.

The short lesson is that we still have a lot to learn from Eisenstein–and his films. Apart from opening up new vistas of cinema, they offer thrilling experiences. Ivan Part II, subtitled “The Boyars’ Plot,” is a dark Jacobean drama of bloody revenge and betrayal. It’s twisted enough to satisfy any connoisseur of palace intrigue. It’s also brilliantly weird as cinema. Once more the Old Man comes through.

Thanks as ever to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and their colleagues at Criterion for making this installment, which was a bit tougher than usual. Thanks as well to old friend Erik Gunneson, and to Masha Belodubrovskaya for translation help. Our entire Criterion Channel series is here.

The best source for Eisenstein’s VGIK classes remains Vladimir Nizhny’s Lessons with Eisenstein, my pick for one of the top ten film books ever published. Direction, Volume 4 of Eisenstein’s Selected Works in Six Volumes (Izbrannie proizvedeniia v shesti tomakh, 1964-1969) is the source of other examples I use here, including Thérèse Raquin, from p. 622.

Of the immense literature on Eisenstein, I especially recommend Yuri Tsivian’s monograph on Ivan the Terrible in the BFI series. Yuri also provided a wonderful video essay for the Criterion DVD release, now unhappily out of print. Kristin wrote a whole book on Ivan: Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible: A Neoformalist Analysis.

I discuss Eisenstein as an action director in an earlier entry. On axial cuts in Eisenstein and others, go here; Kurosawa’s use of them is discussed here.

Hockney’s photomontage Mother 1 is from 1985.

Also, too: I noted earlier that my book On the History of Film Style has gone out of print. An e-book edition, with updates and color images, is nearing completion. I hope to offer a pdf to you soon. Yes, Eisenstein is involved.

Eisenstein sketch: Ivan pleading for mercy in the Last Judgment, planned for Part III of the film.

Ninotchka’s mistake: Inside Stalin’s film industry

DB here:

It’s a commonplace of film history that under Stalin (a name much in American news these days) the USSR forged a mass propaganda cinema. In order for Lenin’s “most important art” to transform society, cinema fell under central control. Between 1930 and 1953 a tightly coordinated bureaucracy shaped every script and shot and line of dialogue, while Stalin frowned from above. The 150 million Soviet citizens were exposed to scores of films pushing the party line.

True? Not quite.

When cows read newspapers

The Miracle Worker (1936).

In the film division of the University of Wisconsin—Madison, we’ve developed a reputation for revisionism. We like to probe received stories and traditional assumptions. In Soviet film studies, Vance Kepley’s In the Service of the State challenged the idealized portrait of Alexandr Dovzhenko, pastoral poet of Ukrainian film, by tracing his debts to official ideology. In my book on Eisenstein, I suggested that this prototypical Constructivist opens up a side of modernism that is artistically eclectic, and even conservative in its gleeful appropriation of old traditions.

Now we have a new book telling a fresh story. Maria (“Masha”) Belodubrovskaya’s Not According to Plan: Filmmaking under Stalin draws upon vast archival material to argue that filmmaking, far from being an iron machine reliably pumping out propaganda, was decentralized, poorly organized, weakly managed, driven by confusing commands and clashing agendas. Censorship was largely left up to the industry, not Party bureaucrats, and directors and screenwriters enjoyed remarkable flexibility.

draws upon vast archival material to argue that filmmaking, far from being an iron machine reliably pumping out propaganda, was decentralized, poorly organized, weakly managed, driven by confusing commands and clashing agendas. Censorship was largely left up to the industry, not Party bureaucrats, and directors and screenwriters enjoyed remarkable flexibility.

Was this an ideological juggernaut? Aiming at a hundred features a year, the studios were lucky to release half that. In 1936 95 films were planned, but only 53 were produced and 34 made it to screens. From 1942 on, those millions of spectators saw only a couple of dozen annually. The nadir was 1951, with 9 releases. (Hollywood studios released over 300.) The flood of propaganda was more like a trickle. Theatres were forced to run old Tarzan movies.

When quantity became thin, apologists claimed that quality was the true goal. But Ninotchka’s hope for “fewer but better Russians” wasn’t realized in the film domain. Critics and insiders admitted that nearly all the films that struggled into release were mediocre or worse.

Not According to Plan shows that Soviet institutions were incapable, by their size, organization, and political commitments, of organizing a mass production film industry. Efforts to set up something like the U.S. studio system ran up against obstacles: there weren’t enough skilled workers, and decision-makers clung to the notion of the master director. Boris Shumyatsky, who visited Hollywood and tried to create something similar at home, got his reward at the muzzles of a firing squad. But brute force like this was rare; there were few administrators and creators to spare.

The great plan was to have a Plan—specifically, a thematic one. Production would be based on an annual cluster of powerful topics like “Communism vs. capitalism” and “Socialist upbringing of the young.” Personnel were slow to realize that themes were not stories, let alone gripping ones, and the real work of imagination remained un-plannable. Starting from themes rather than plot situations, the overseers could judge only final results, which meant enormous investments in development and production—all of which might never yield a politically correct movie.

Production, wholly divorced from distribution and exhibition, couldn’t count on the vertical integration of Hollywood. Masha shows in rich detail how policies and routines worked against large-scale output. One of the most striking of those policies was the veneration of directors. A great irony of the book is that Hollywood filmmaking, with its platoons of screenwriters both credited and uncredited, was more collectivist than production in the USSR. Soviet directors enjoyed enormous stature and power. They were often the moving force behind a production, bringing on writers and then recasting the script during shooting. Assemblies of directors formed review committees, discussing and often defending their peers’ work. As Masha puts it:

The filmmaking community, and specifically film directors, never gave up on the standard of artistic mastery. They listened to the signals sent by the Soviet leadership, but then incorporated these into their own professional value system, which developed in the 1920s outside the purview of the state. Using the state’s discourse of quality and their peer institutions, they enforced their own shared norms of artistic merit.

The downside of this system, plan or no plan, was that when the film didn’t pass muster, the director was to blame. Yet the twenty or so “master” directors could survive failed projects. New talent wasn’t trusted; there were too few directors; and most basically, the organization of production remained artisanal. The role of the producer (let alone the powerful producer) scarcely existed. To a surprising extent, Soviet cinema encouraged the director as auteur. How’s that for revisionism?

Screenwriters weren’t as powerful, but they did their part. Masha has a fascinating chapter on the changing conceptions of the Soviet screenplay. The “iron scenario,” modeled on a Hollywood shooting script, was intended to lay out the film in toto, so directors couldn’t overshoot or make changes. This initiative, predictably, failed. There followed other variants: the butter scenario, the margerine scenario, and the rubber scenario (no kidding), then the emotional scenario and the literary scenario.

Masha traces the work process of screenwriting and the mostly futile efforts of literary figures to leave their stamp on a production. A similar stress on process characterizes her occasionally hilarious case studies of censorship. Some of these expose the limits of industry self-censorship. One agency signs off on a film, the next one castigates it, the next one reverses that judgment, Pravda weighs in, and finally Stalin speaks up—with a completely unpredictable verdict, à la Trump. The tale of Medvedkin’s The Miracle Worker, which jumped through all the hoops and wound up being banned after initial screenings anyhow, might have been written by Zoshchenko or Ilf and Petrov. Among the elements judged “absolutely impermissible” were shots of cows reading newspapers.

The artistic and popular success of Soviet films during the New Economic Policy (1921-1928) had spurred hopes for a mass-market sound cinema that was also of high quality. What crushed that dream? Masha gives us the hows (the machinations of the studios and government bodies) and the whys (the underlying causes and rationales). Not According to Plan is a trailblazing study of what she calls “the institutional study of ideology.” It’s also a quietly witty account of the failures of managed culture. How could artists be engineers of human souls if they couldn’t engineer a movie?

But go back to the quality issue. What were those Stalinist films like artistically?

Socialist Formalism

Three projects I’ve undertaken led me to Stalin-era cinema. Nearly all English-language film histories ignored it, or reduced it to boy-loves-tractor musicals. So Kristin and I wanted our textbook Film History: An Introduction to consider it. (Revisionism again.) My Cinema of Eisenstein and On the History of Film Style built on what I saw at archives in Brussels, Munich, and Washington DC.

As a result I sought to mount an argument that Stalinist cinema was worth our attention, especially from the standpoint of film technique. The run-of-the-mill productions seemed fairly shambolic, but the top-tier dramas revealed an academic style that interested me. Some films recalled, even anticipated, innovations taking hold in Europe and America, but other creative choices were surprisingly offbeat, and not what we associate with standard propaganda.

For one thing, it was clear that montage experiments didn’t end with the 1920s, the arrival of sound, or even the “official” establishment of Socialist Realism around 1934. Granted, classic continuity editing rules the fiction films of the 1930s and 1940s, and the most flagrant extremes of the montage style were purged.

But some moments recall the silent era. These passages are typically motivated, as in Hollywood and other national traditions, by rapid action. Military combat calls forth stretches of 2-4 frame shots of bombardment in The Young Guard, Part 2 (1948). The combat scenes of The Battle of Stalingrad (1949) include very brief shots. In one passage, an artillery blast consists of three frames—one positive, a second negative, and a third positive again, creating a visual burst.

The abrupt disjunctions of the 1920s style can be felt a little in one cut of The Fall of Berlin (1950), when at the end of a long reverse tracking shot, Alyosha and his comrades rush the camera. Cut to Hitler recoiling, as if he sees them.

As you’d expect in an academic tradition, the use of fast cutting for fast action isn’t disruptive. A little more unusual is the embrace of wide-angle lenses, often more distorting than in Western cinema. Wide-angle imagery was used by 1920s filmmakers, often to caricature class enemies or to heroicize workers. The same sort of thing can be seen in Kutuzov (1945), when a soldier is presented in a looming close-up, or in Front (1943), when a gigantic hand reaches out for a telephone.

This use of wide angles to give figures massive bulk continued through the 1950s, as in The Cranes Are Flying (1957).

The 1940s aggressive wide-angle shots run parallel to Hollywood work, when in the wake of Citizen Kane (1941), The Little Foxes (1941), and other films, many directors and cinematographers created vivid compositions in depth. Those weren’t unprecedented in America, as I try to show in the style book, but there were some early adopters in Russia as well.

Obliged to show meetings of saboteurs, workers, generals, and party leaders, Soviet filmmakers had to dramatize people in rooms, talking at very great length. The result was a tendency toward depth staging and fairly long takes. The low-angle depth shot stretching through vast spaces became a hallmark of this academic style in the 1930s and after.

Director Fridrikh Ermler, one of the few directors who was a Party member, claimed that he devised a “conversational cinema” to deal with the prolix dialogue scenes in The Great Citizen (1937, 1939). The movie teems with shots that wouldn’t look out of place in American cinema of the 1940s.

As a solution to the problem of talky scenes, staging of this sort makes sense as a way to achieve some visual variety, and to show off production values. By the 1940s, such flamboyant depth became even more exaggerated. We see it in the telephone framing from Front above, as well as in The Young Guard Part 1 (1948, below left) and the noirish stretches of The Vow (1946, below right).

The Fall of Berlin can use depth to contrast the placid self-assurance of Stalin with a ranting Hitler, bowled over by his globe. Is this a reference to the globe ballet in The Great Dictator?

It’s well-known that for Kane Orson Welles and Gregg Toland wanted to maintain focus in all planes, sometimes resorting to special-effects shots to do so. The Soviets valued fixed focus as well, as several shots above suggest. It could be maintained if the foreground plane wasn’t too close, and the depth of field would control focus in the distance. Hence many shots use distant depth. At one point in The Great Citizen, when a woman interrupts a meeting, the official in the foreground trots all the way to the rear to meet her.

The sense of cavernous distance is amplified by the wide-angle lens.

But sometimes pinpoint focus in all planes wasn’t the goal. Another way to activate depth was to rack focus. In this scene of Rainbow (1944), the man who has betrayed the village comes home and discovers a delegation waiting to try him. At first they’re out of focus, but when he turns they become visible.

Focused or not, some of these shots push important action to the edge of visibility in a way that would be rare in American cinema. In A Great Life, a snooper is centered but sliced off by a window frame and kept out of focus, while a trial scene is interrupted by a figure far in the distance who bursts in to announce a mine collapse.

The Great Citizen shows Shakhov discussing a suspect, who hovers barely discernible in the background over his left shoulder. I enlarge the fellow and brighten the image.

This makes Wyler’s sleeve-shot in The Little Foxes seem a little obvious.

The Great Whatsis and the masters of the 1920s

The New Moscow (1938).

If American movies favor titles called The Big …., the Soviets liked The Great …. (Velikiy). But The Big Sleep doesn’t look all that big, and The Big Sick is big only to a few people, and The Big Knife doesn’t even have a knife. In the USSR, calling something big summoned up monumentality. Stalinist culture was grandiose in its architecture, sculpture, painting, literature, and even music, with symphonies of Mahlerian length and oratorios boasting hundreds of voices.

Accordingly, one effect of the depth aesthetic was to grant the characters and their settings a looming grandeur. Earth-changing historical events were being played out on a vast stage that framing and set design put before us.

Naturally, battles are on a colossal scale. Napoleon broods in the foreground (Kutuzov) and troops march endlessly to the horizon (The Vow).

1940s films feature wartime landscapes on a scale almost unknown to Hollywood. If God favors the biggest battalions, God would seem to love the Russians (a prospect that otherwise seems invalidated by history). Below: The Battle of Stalingrad.

These landscapes are surveyed in long tracking shots, a habit that survived in Bondarchuk’s War and Peace (1966-1967).

Soviet forces command impressive headquarters (The Great Change, 1945), perhaps necessary to balance the Nazis’ resources (The Vow).

Parlors and committee rooms are remarkably big, and even prison cells (The Young Guard Part 2) and farmhouses (The Vow) have plenty of room.

Gigantism wasn’t unknown in 1920s cinema, or in Russian painting both classic and recent. The Vow seems to justify its scale by reference to a Repin painting, which the characters see on display.

Not only were the 1920s silent classics monumental; they became monuments. Masha records the veneration that the “master” directors felt for the works of Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Kuleshov, Barnet, and other predecessors. Moments in the Stalinist cinema seem to refer back to that era. The Battle of Stalingrad evokes the mother with the slain child on the Odessa Steps, and The Vow has the nerve to superimpose on Stalin (friend of farmers) an image of concentric plowing from Old and New.

These can be taken as cynical ripoffs, but in a way they testify to the fact that great silent films had forged some enduring iconography.

VIP: Very important, Pudovkin

You don’t hear much about Pudovkin’s 1930s and 1940s films, but they can be exuberantly strange. Eisenstein aside, he stands in my viewing as the director who played around most ambitiously with the academic style. Perhaps he was encouraged in this by his young codirector Mikhail Doller, but Pudovkin had already tried out some audacious strokes in A Simple Case (1932) and Deserter (1933).

For a high Stalinist example take Minin and Pozharsky (1939). This tale of seventeenth-century warfare seems virtually a reply to Alexander Nevsky (1938), as Mother (1926) responded to Strike (1925). Minin opens with statuesque staging reminiscent of Eisenstein’s film, but the scene is handled in telephoto shots and to-camera address. The combat scenes employ handheld battle shots, along with close-ups of fighters and horsemen that aren’t stylized in the Nevsky manner.

But there’s more than pastiche here. One battle shows the Russian forces rushing from the left in tight tracking shots, while the enemy forces move from the right in panning telephoto. Especially striking are axial cuts, beloved of Soviet filmmakers for static arrays, employed in movement. Horses sweep past a tent in extreme long-shot; they smash into the tent in long shot; and in a closer view the tent lies trampled as other horses continue to flash through the foreground.

The shots are 50 frames, 38 frames, and 13 frames respectively. For a moment, we might be back in the great era of Soviet editing.

Victory from 1938 is a drama in which aviators set out to rescue an interrupted around-the-world flight. Here Pudovkin and Doller invoke the depth staging of the era only to disrupt it with what we might call “smear” cuts.

During the parade for the departing airmen, for instance, a young man happily tossing papers, in another grotesque wide-angle shot. He’s blocked by a man passing through the frame. Match on action cut to another figure, close to the camera and moving in the same direction. This figure wipes away to reveal a man reading a newspaper.

This sort of weird graphic match becomes a stylistic motif in the film. Later, when the rescue has been completed, another crowd scene yields a similar pattern of depth smeared and exposed. A shot of the parade is sheared off by a woman’s passing face. That cuts to a man’s passing face, which moves away to show the crowd behind him.

The patterning pays off when the victorious plane rolls triumphantly through the frame, blotting out the image, to be graphically matched by a passing figure who unveils the pilot’s mother embracing him.

In Admiral Nakhimov (1947) Pudovkin and Doller employ the smear-cutting technique during a battle scene. Stills are totally unable to capture the way this looks. Soldiers charge up a hill, and their falling bodies, briefly blocking the camera’s view, are given in jump-cut repetitions that suggest, through a spasmodic rhythm, the sheer difficulty of advancing.

Even stranger is the moment when soldiers rush toward a distant fortification, with a latticework basket in the foreground. Cut to the hill edge, with a comparable blob moving leftward through the frame. It turns out to be a fighter’s shoulder.

The oddest part is that this second shot is only six frames long, and every frame after the first is a jump cut; that is, some frames have been dropped as the blob makes its way across the image. The effect on your eye is percussive, and seems to be anticipated by Pudovkin’s experiments in popping black frames into shots in A Simple Case. What kind of director thinks like this?

Of course these Pudovkin/Doller films also subscribe to the official look, with monumental depth staging. The films acknowledge the 1920s tradition as well. Admiral Nakhimov casts a personal look back to Pudovkin’s great rival. A shot of the crew’s tautly bulging hammocks recalls, maybe cites, the crew’s sleeping area of Potemkin.

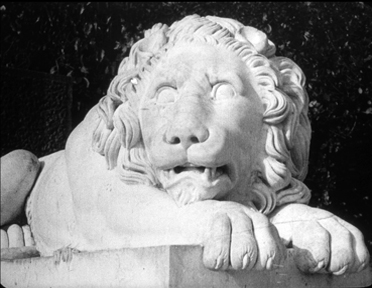

In Odessa, Admiral Nakhimov echoes Potemkin even more strongly. We get waving crowds, the stone lions, and a reminder of those famous steps.

In sum, the Stalinist cinema holds a unique interest for students of the history of film style. Not only did it apparently constitute a significant development in technique, but in forming a tradition, it provided a counterpart and sometimes a counterpoint to developments in the West. Later that tradition became something for directors to react against (Tarkovsky and Sokurov come to mind) or to adapt to new purposes (I’d put Jancsó in that category). For all the behind-the-scenes bungling, it became much more than a propaganda vehicle.

Scholars who study Stalinist film are usually impelled by an interest in propaganda or an interest in the audience’s response. My questions were different. I was driven by my interest in Eisenstein and comparative stylistics. So I tried to investigate the formal and stylistic norms of Soviet cinema. Some of those norms Eisenstein helped create, and then revised for his own ends.

Still, I feel like a butterfly collector picking out vivid specimens for an expert to explain. I can’t supply the hows and whys. How did filmmakers manage to create these remarkable images? What technical resources, of lenses and lighting rigs and film stock and set design, permitted them to craft these striking shots? Were their peers and masters insensitive to this official look? Was it taken for granted? Or was it self-consciously promoted and taught? Some of these schemas are developed in Eisenstein’s lectures at the Soviet film school. And how, at a more micro-level, do these patterns function in the individual films?

As for the whys: Why did filmmakers embrace these options rather than others? And why did they develop, sometimes apparently in a spirit of play, some oddball technical innovations?

Such questions seem to me compelled by films that turn out to be more artistically interesting than most commentators have noted. One of the most corrupt and brutal political systems in world history produced films of considerable interest, and a few of enduring value. I hope experts try to figure this all out. I bet Masha Belodubrovskaya will lead the way. Her new book is a splendid start.

Masha is no stranger to this blog, having translated Viktor Shklovsky’s remarkable “Monument to a Scientific Error” for us.

This is a good place to thank all the people who helped me see Stalinist films in archives over the decades. That number includes Gabrielle Claes, Nicola Mazzanti, and the late Jacques Ledoux of the Belgian Cinematek; Enno Patalas, Klaus Volkmer, and Stefan Droessler of the Munich Film Museum; and Pat Loughney, then of the Library of Congress.

I learned of Ermler’s “conversational cinema” (razgovornyi kinematograf) from Julie A. Cassiday’s “Kirov and Death in The Great Citizen: The Fatal Consequences of Linguistic Mediation,” Slavic Review 64, 4 (Winter 2005), 801-804. The depth aesthetic of high Stalinist cinema proved valuable when 1960s bureaucrats decided to make Stalin disappear. See our online supplement to Film History: An Introduction.

There are more examples of “Stalinist formalism” in On the History of Film Style–recently declared out of print, but soon to appear in a new electronic edition on this site. See also my Cinema of Eisenstein for arguments about how he created and then swerved from some of his peers’ norms.

Today’s Google Doodle pays tribute to Eisenstein on his birthday. But they make him a slim, hip metrosexual. Revisionism can go too far.

Kelley Conway, Masha, and Scott Gehlbach, at a party last night celebrating Masha’s book–and her winning tenure! Kelley’s contributions to our blog are here and here and here.

The ten best films of … 1925

The Big Parade (1925).

Kristin here:

As all about us in the blogosphere are listing their top ten films for 2015, we do the same for ninety years ago. Our eighth edition of this surprisingly popular series reaches 1925, when some of the major classics of world cinema appeared. Soviet Montage cinema got its real start with not one but two releases by one of the greatest of all directors, Sergei Eisenstein. Ernst Lubitsch made what is arguably his finest silent film. Charles Chaplin created his most beloved feature. Scandinavian cinema was in decline, having lost its most important directors to Hollywood, but Carl Dreyer made one of his most powerful silents.

For previous entries, see here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, and 1924.

The lingering traces of Expressionism vs the New Objectivity

The Joyless Street (1925).

Last year I suggested that German Expressionism was winding down in 1924. It continued to do so in 1925. Indeed, no Expressionist films as such came out that year. What I would consider to be the last films in the movement, Murnau’s Faust and Lang’s Metropolis, both went over budget and over schedule, with Faust appearing in 1926 and Metropolis at the beginning of 1927.

Murnau made a more modest film that premiered in Vienna in late 1925, Tartuffe, a loose adaptation of the Molière play. The script adds a frame story in which an old man’s housekeeper plots to swindle and murder him. The man’s grandson disguises himself as a traveling film exhibitor and shows the pair a simplified version of the play, emphasizing the parallels between the hypocritical Tartuffe and the scheming housekeeper.

The film has some touches of Expressionism but cannot really be considered a full-fledged member of that movement. The lingering Expressionism is not surprising, considering that some of the talent involved had worked on Robert Wiene’s Das Cabinet des Dr.Caligari: screenwriter Carl Mayer, designers Walter Röhrig and Robert Herlth, and actors Werner Krauss and Lil Dagover.

The visuals include characteristically Expressionist moments when the actors and settings are juxtaposed to create strongly pictorial compositions. These might be comic, as when the pompous Tartuffe strides past a squat lamp that seems to mock him, or beautifully abstract, as when Orgon is seen in a high angle against a stairway that swirls around him:

A restored version is available in the USA from Kino and in the UK in Eureka!‘s Masters of Cinema series. (DVD Beaver compares the two versions.) The restoration was prepared from the only surviving print, the American release version; it runs about one hour.

The other German film on this year’s list, G. W. Pabst’s The Joyless Street, contrasts considerably with Tartuffe. It was arguably the first major film of the Neue Sachlichkeit or New Objectivity trends in German cinema. I have already dealt with it in a DVD review entry shortly after its 2012 release. The restoration incorporated a good deal more footage than had been seen in previous modern prints, but it remains incomplete.

Once more the comic greats

The Gold Rush (1925).

For several years now these year-end lists have mentioned Charles Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd, in various combinations. Early on it would was Chaplin alone (Easy Street and The Immigrant for 1917) or Lloyd and Keaton alone (High and Dizzy and Neighbors for 1920). In a way most of these films were placeholders, signalling that these three were working up to the silent features that were among the most glorious products of the Hollywood studios in the 1920s. In our 1923 list, each found a place with a masterpiece: Chaplin’s A Woman of Paris, Keaton’s Our Hospitality, and Lloyd’s Safety Last.

This year we may surprise some by giving Lloyd a miss. For years The Freshman was thought of as his main claim to fame, perhaps alongside Safety Last. I think this was largely because The Freshman was the one of the few Lloyd films that was relatively easy to see. (Perhaps also because Preston Sturges dubbed it an official classic by making a sequel to it (The Sin of Harold Diddlebock, aka Mad Wednesday, 1947.) Now that we have the full set of Lloyd’s silent features available, it emerges as a rather tame entry compared to Safety Last, Girl Shy, or our already-determined entries for 1926, For Heaven’s Sake, and 1927, The Kid Brother. Let’s just call The Freshman a runner up.

Keaton’s Seven Chances takes one of the most familiar of melodramatic premises and literally runs with it. James Shannon discovers from his lawyer than he stands to inherit a great deal of money if he is married by 7 pm on his 27th birthday–which happens to be the day when he receives this news. A misunderstanding with the woman he loves leads to a split, and in order to save himself and his partner from bankruptcy, Shannon determines to marry any woman who will volunteer in time. Hundreds turn up.

The result is another of the extended, intricate chase sequences that tend to grace Lloyd’s and Keaton’s features, and to a lesser extent Chaplin’s. In fact Seven Chances has a double chase. The first and longer part involves a huge crowd of women gradually assembling behind Shannon as he unwittingly walks along the street. This accelerates and keeps building, exploiting various situations and locales, as when the chase passes through a rail yard and Shannon escapes by dangling from a rolling crane above the women’s heads. Eventually the action moves into the countryside, where the brides temporarily disappear, taking a short cut to cut Shannon off, and he ends up in the middle of a gradually growing avalanche.

Seven Chances is available on Blu-ray and DVD from Kino.

Of all the films on this year’s list, Chaplin’s The Gold Rush is probably the most widely familiar. The Little Tramp character, here known only as a “Lone Prospector,” blends hilarity with pathos in a fashion that is actually typical of relatively few of the director/performer’s films overall. It is, however, how many people think of him.

The Gold Rush looks rather old-fashioned compared with Seven Chances. Although the opening extreme long shots of an endless line of prospectors struggling up over a mountain pass are impressive, much of the action takes place in studio sets, sometimes standing in for alpine locations. Both the cabins, Black Larsen’s and Hank Curtis’, are like little proscenium stages, with the action captured from the front. Yet the film depends on its brilliant succession of gags and on the Prospector’s status as the underdog who is also the resilient and eternal optimist.

The best bits of humor arise from Chaplin’s ability to create funny but lyrical moments by transforming objects metaphorically. Given the plot, some of the best-known gags arise from meals. One is the dance of the rolls, part of a fantasy sequence in which the Prospector dreams of entertaining a group of beautiful women at dinner (above), when in fact the women stand him up. Trapped by a storm in a remote cabin, the Prospector and his partner cook one of his shoes. He serves it on a platter and carefully “carves it, with the leather becoming the meat, the nails bones, and the laces spaghetti.

Many home-video versions of The Gold Rush have been released, but the definitive restoration of the 1925 version is available from the Criterion Collection.

The Golden Age in full swing

Lazybones (1925).

When people speak of the “Golden Age” of the Hollywood studio system, they usually seem to mean the 1930s and 1940s (and the lingering effects of the system in the 1950s). A look at Hollywood films of the 1920s shows that it was already functioning at full steam. Three features of 1925 display the utter mastery of continuity storytelling and style and a sophistication that matches films of subsequent decades.

Lady Windermere’s Fan may be the best silent made by Ernst Lubitsch, who has appeared on these lists before. It arguably ranks alongside Trouble in Paradise and The Shop around the Corner as one of the best films of his entire career. It’s a loose adaptation of the Oscar Wilde play, but it’s pure Lubitsch throughout.

Anyone who thinks that the classical Hollywood system was merely a set of conventions that allowed films to be cranked out with minimal originality could learn a lot from Lady Windermere’s Fan. Its completely correct use of continuity editing, three-point lighting, and the like does not preclude imaginative touches and methods of handling whole scenes. There’s the sequence when Lord Windermere visits the mysteriously shady lady Mrs. Erlynne in her drawing-room. The camera is planted in the center of the action, with frequents cuts as the two characters move in and out of the frame and even cross behind the camera. There’s not a hint of a mismatched glance or entrance across this complex and unusual series of shots. There’s the racetrack scene, as everyone present watches and gossips about Mrs Erlynne in a virtuoso string of point-of-view shots.

The racetrack scene ends with a wealthy bachelor following Mrs Erlynne out of the track. The camera moves left to follow her, keeping her in the same spot in the frame. As the man gradually catches up, Lubitsch uses a moving matte to hint at their meeting without showing it or cutting in toward the action.

A good-quality transfer of Lady Windermere’s Fan is only available on DVD as part of the More Treasures from American Film Archives 1894-1931. (Beware the copy offered by Synergy, which according to comments on Amazon.com is from a poor-quality, incomplete print.)

The one title on this list whose inclusion might surprise readers is Frank Borzage’s Lazybones. I remember being bowled over by this film during the 1992 Le Gionate del Cinema Muto festival in Pordenone, which included a Borzage retrospective. I found the more famous Humoresque (1920) a disappointment, but Lazybones was a revelation. This is another case of a film that was simply unknown when film historians started writing about the Hollywood studio era. It was not discovered until 1970, when it was found in the 20th Century-Fox archives. As a result, Lazybones was, as Swiss film historian Hervé Dumont put it in his magisterial book on the director, “revealed as the most poignant–and the most accomplished–of Borzage’s works before Seventh Heaven.”

Year by year since we started this annual list, I looked forward to recommending Lazybones, and now we arrive there. I rewatched it for the first time to see if it really deserved to make one of the top ten. The answer is yes. For me, this is as good as 7th Heaven, or as near as makes no difference.

It’s difficult to describe the plot of Lazybones, since it doesn’t have much of one. Steve (played by the amiable Buck Jones) is a very lazy young man living in a rural village. He has a girlfriend, Agnes, whose mother scorns him. The girlfriend has a sister, Ruth, who returns home with a baby in tow. In despair, Ruth leaves the baby on a riverbank and tries to drown herself (image at top of section). Steve rescues her, and she explains that unknown to her family, while she was away she married a sailor who subsequently went down with his ship. She has no proof of this and knows her tyrannical mother will assume that the baby is illegitimate. Steve decides to keep her secret and adopt the apparent foundling himself.

All this happens during the initial setup. Then the little girl, Kit, grows up into a young lady. Along the way, not all that much happens. Steve, lacking any goals, stays lazy, which sets him apart from the energetic, ambitious protagonists of most Hollywood films. Kit is shunned by her classmates and the townspeople, and Steve tries to shelter her from all this. He loves Agnes but quickly loses her to a richer, more respectable man. He goes off to fight in World War I, becomes an accidental hero, and returns home after perhaps the shortest battlefront scene in any feature of the period. Kit finds a boyfriend.