Archive for the 'Directors: Eisenstein' Category

But what kind of art?

2046.

From DB:

We don’t have to think of film as an art form. A historian can treat a movie as a document of its time and place. A war buff could scrutinize Eastwood’s Iwo Jima movies for their accuracy, and a chess expert could sieve through Looking for Bobby Fischer to discover, move by move, what matches were dramatized. But most of the time we assume that cinema is an art of some sort.

Not necessarily high art. Cinema is often a popular art, or in Noël Carroll’s phrase, a mass art. From this angle, there’s no split between art and entertainment. Popular songs are undeniably music, and best-selling novels are instances of literature. Similarly, megaplex movies are as much a part of the art of film as are the most esoteric experiments. Whether those movies, or the experiments, are good cinema is another story, but cinema they remain.

So, at least, is our position in Film Art: An Introduction. We draw our examples from documentaries, animated films, avant-garde films, mainstream entertainment vehicles, and films aimed at narrower audiences. In other writing, Kristin has done research on high-art movements like German Expressionism and Soviet Montage (she wrote her dissertation on Ivan the Terrible), but she’s also written about popular cinema from Doug Fairbanks to The Lord of the Rings. I’ve indulged my admiration for Hou and Dreyer but also I’ve tried to tease out the aesthetics of Hong Kong action pictures and contemporary Hollywood blockbusters. Ozu gives us the best of both worlds: one of cinema’s most accomplished artists, he was also a popular commercial filmmaker.

Still, people who look upon cinema as an art don’t necessarily share the same conceptions of what kind of art it is. We have different conceptions of cinema’s artistic dimensions, and we won’t find unanimity of opinion among filmmakers, critics, academics, or audiences.

When we study film theory, this sort of question comes to the fore, and so today’s blog will be a bit more theoretical than most. Don’t let that scare you off, though; I’m trying for clarity, not murk.

Dimensions

People have tended to think of cinema as an art by means of rough analogies to the other arts. After all, film came along at a point when virtually all the other arts had been around for milennia. It’s commonly said that film is the only artform whose historical origins we can determine. So it’s been natural for people to compare this new medium with older arts.

Here are the dimensions that come to my mind:

*Film is a photographic art.

*Film is a narrative art.

*Film is a performing art.

*Film is a pictorial art.

*Film is an audiovisual art.

Let me say off the bat that I think that film is a synthetic medium, in the sense that all these features and more can be found in it. It’s like opera, which is at once narrative, performative, musical, and even pictorial. I mark out these dimensions simply to show some emphases in people’s thinking about cinema. As we’ll see, these ideas can be mixed together in various ways.

Film as a photographic art.

La petite fille et son chat (1900).

For many early filmmakers, such as the Lumière brothers (above), cinema was a means of capturing reality, documenting the visible world. Movies were moving photographs. Naturally, this conception of cinema leads us to treat documentary as the central mode of filmmaking.

It’s an appealing idea. G.W. Bush reading “My Pet Goat” wouldn’t be as revelatory presented as a painting or a theatre performance. On film we can see the event as it occurred and judge it as if we were in the same room. Even in fictional cinema, you can argue, the physicality of the actors, the tangibility of the setting, and the details–a train’s pistons, wind rustling through grass–could not be rendered, or even imagined, so powerfully in a non-photographic medium. In addition, consider Jackie Chan. His stunts are astonishing partly because we know he really did them and the camera photographed them. In an animated film, or a CGI-based one, a character’s acrobatics or brushes with death aren’t so thrilling.

The great film theorist André Bazin claimed that cinema’s photographic basis made it very different from the more traditional arts. By recording the world in all its immediacy, giving us slices of actual space and true duration, film puts us in a position to discover our link to primordial experience. Other arts rely on conventions, Bazin thought, but cinema goes beyond convention to reacquaint us with the concrete reality that surrounds us but that we seldom notice.

I think that Bazin’s idea lies behind our sense that long takes and a static camera are putting us in touch with reality and inviting us to notice details that we usually overlook in everyday life. (I try out this line of argument in relation to the tactility of Sátántangó here.) Moreover, you can argue that in treating cinema as a photographic art the filmmaker surrenders a degree of control over what we see and how we see it. Bazin made this claim about the Italian neorealists and Jean Renoir: creation becomes a matter of an existential collaboration between humans and the concrete world around us.

An example I used in my book Figures Traced in Light pertains to a moment in Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Summer at Grandfather’s, when a tiny toy fan falls between railroad tracks as a locomotive roars past. The fan’s blades stop, then spin in the opposite direction as the train thunders over it. The blades reverse again when the train has gone. (This detail might not be visible on video.) Did Hou know how the fan would behave? Isn’t it just as likely he simply discovered it after the fact, making his shot a kind of experiment in the behavior of things? Conceived as a species of photography, cinema can yield visual discoveries that no other art can.

Interestingly, cinema didn’t have to be photographic. Many early experiments with moving images were made with strips of drawings, such as the Belgian Émile Reynaud’s Praxinoscope. You can argue that recording glimpses of the world photographically simply proved to be the easiest way to obtain a long string of slightly different images that could generate the illusion of movement. Some filmmakers, such as George Lucas, hold that filmmakers are no longer tied to photography, and that the digital revolution will allow cinema to finally realize itself as a painterly art. More on that below.

Film as a narrative art.

Rope.

This is at the core of Hollywood’s explicit concerns. Producers, directors, crew, and of course screenwriters will agree that Without a good story, the movie fails. Our Indie and Indiewood filmmakers say they’re trying to find fresh stories, the ones that “haven’t been told yet.” Overseas filmmakers dominated by Hollywood tell us, “We have our own stories to tell.” Even the most celebrated arthouse filmmakers often say they’re interested in character as revealed through action. Resnais, Rivette, Fassbinder, Haneke, and all the rest may have told unusual stories, but still they told ’em.

Likewise, many viewers will say that they go to the movies to experience a story. Reviewers online and in the popular press, if they do nothing else, are obliged to sketch out the film’s plot, though they mustn’t give away the ending. Even in academia, most discussions of films focus on what happens in the narrative.

When we consider film genres, we’re usually concentrating on the narrative aspects of them. Most genres display typical characters and plot patterns. The backstage musical features aging stars and young hopefuls, caught up in the process of putting on a show. The horror film typically centers on a monster’s attack on humans, who must fight back. One type of science fiction shows us an overweening scientist striving to go beyond “what is proper for humans to know.” Both fans and scholars discuss other aspects of genre films, but narrative is often central to their concerns.

Historians have traced in great detail how filmmakers employed cinema as a narrative art, but we’re making more discoveries all the time. How, for instance, have films signaled flashbacks? How do they let us know we’re in a character’s mind, or attached to his or her optical point of view? How have they structured their plots? Can we pick out distinct approaches to narrative–in various periods, or genres, or national cinemas? How have narrative conventions changed over the years? Some of the answers Kristin and I have proposed can be found elsewhere on this site, and in our books and articles.

Film as a performing art.

The Marrying Kind.

In the West, since Plato and Aristotle we’ve distinguished between verbal storytelling and dramatic presentation, or performance. Films may be stories, but they’re not exactly told: they’re enacted. At Oscar time, we’re especially conscious of this analogy, for the Actor/ Actress nominees usually garner the most public attention.

Hollywood acknowledged cinema as a performing art in the 1910s, when it created the star system. The Star reminds us that film acting isn’t exactly the same as theatre acting, since an elusive charisma puts the performance across. John Wayne, Marilyn Monroe, Keanu Reeves, and many other “axioms of the cinema” aren’t good actors by stagebound standards, but once they show up on screen, you can’t take your eyes off them. This notion intersects with the photographic premise: we say that the camera seems to love them.

You can argue that Andy Warhol revamped this idea. His superstars weren’t photogenic by ordinary standards but their almost clinical narcissism and exhibitionism, captured by the camera, made them as mesmerizing as any matinee idols. Warhol films like Paul Swann create rather disturbing emotions by putting us in the presence of an awkward performer.

Reviewers place a premium on a movie’s performance dimension. After they’ve told us a bit of the plot , they appraise the job the actors did. Some ambitious critics have written wonderful appreciative essays on acting, as in Andrew Sarris’s “You Ain’t Heard Nothin’ Yet” and the collection OK You Mugs. See also the two collections of articles by Gary Giddins, which I discuss in an earlier blog.

Academic film studies has been slow to study acting systematically, partly because of a bias against considering cinema as a theatrical art, and partly because acting is very hard to analyze. But Charles Affron, Jim Naremore, Roberta Pearson, and Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs have greatly helped us understand performance practices. They show, among other things, that it isn’t just a matter of the face or the voice: a fluttered hand or a willowy stance can be as powerful as a frown or a line reading.

Film as a pictorial art.

Ohayu (Good Morning).

Progressive opinion in the silent era tended to deny that film was a performing art, since that would make it a form of theatre. No, film had unique capacities. Cinema was essentially moving pictures.

It was a visual art that unfolded in time, so a movie was neither quite the same as a painting (frozen in time) or as a stage play (not pictures but three-dimensional reality). The coming of sound somewhat reduced the appeal of this line of argument, but to a very great extent, students of film technique still emphasize cinema as a visual art.

Theorists argued that the film frame was a pictorial field, not a proscenium stage. Action unfolded in the frame in ways that dynamized space. The choice of angle, camera distance, camera movement, and the like created a visual fluidity that had no equivalent on stage or in other graphic arts. Even cinematic staging was quite different from blocking in a theatrical space. Add to this the ability to join one strip of pictures to another via editing, and we have a unique pictorial artform.

The theorists of the silent era, like Rudolf Arnheim and the Russian montagists, gave us a vocabulary and an orientation to studying visual style, but their legacy hasn’t been fully developed. Journalistic reviewers typically don’t pay that much attention to the way movies look. Nor, surprisingly, do academics. Film studies departments seldom pursue research into visual style and structure.

Here the professors are out of sync with the people whose work they study. Manuals and film schools teach composition, lighting, cutting, camera placement and the like. Professional filmmakers all over the world often think in pictures; they prepare shot lists and storyboards and care very much about the color values and editing patterns of the finished work. We can see their interest in visuals in DVD commentaries and supplements, and as viewers start to absorb bonus materials, perhaps their interest will be whetted too.

Needless to say, a number of avant-garde filmmakers, from Viking Eggeling and Walter Ruttmann to Deren, Brakhage, Ernie Gehr, James Benning, and Nathaniel Dorsky, have also thought of cinema as having the power to refresh, even redeem, our vision. But many of the most important directors aiming at broader audiences are also renowned for their visual styles. To mention just a few: Griffith, Feuillade, Sjostrom, Keaton, De Mille, Murnau, Lang, Dreyer, Lubitsch, and Dovzhenko; Ford, Hitchcock, and von Sternberg; Renoir, Ozu (above), Mizoguchi, and Ophuls; early Bergman, Antonioni, Jancsó, Resnais, Angelopoulos, Tarr, Tarkovsky, Kieślowski, Kiarostami, and Makhmalbaf; Scorsese, Spielberg, Michael Mann, and Tim Burton. Some, like Oshima, Sokurov, and Johnnie To, have been polystylistic, exploring many different visual pathways.

Film as an audiovisual art.

In the 1920s, many theorists feared the coming of synchronized sound, since that would thrust film back toward theatre. The “talkies” would sacrifice visual artistry to Broadway dialogue. This worry was mistaken, but I can sympathize. Probably the mandatory silence of early film pushed filmmakers to find means of visual expression. Would we have Chaplin and the other clowns if they could have spoken at the start?

Yet a great deal of sound cinema wasn’t canned theatre. Film became a synthetic medium blending imagery, the spoken word, sound effects, and music into something that was neither painting nor theatre nor illustrated radio.

Though he’s thought of as the premiere theorist of editing, Eisenstein actually developed this idea of audio-visual synthesis. He was fascinated by the ways in which images and music worked together, creating an idea or feeling that couldn’t be expressed by either one. If shot A followed by shot B gave us something that wasn’t present in either one, then why couldn’t shot A and sound B yield the same results? He believed that Disney’s 1930s films were the strongest efforts in this direction, as when a peacock fanned out his tail to a rippling melody. Eisenstein called it “synchronization of senses.”

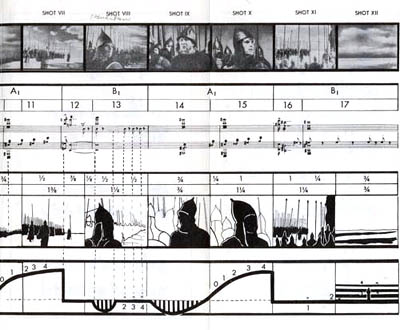

Eisenstein sometimes pushed this idea pretty far. His remarkable analysis of one sequence in Alexander Nevsky (sample above) tried to show how the movement of the viewer’s eye across a suite of shots actually mimicked the movement of the music. He made the case tough for himself because the shots contain almost no movement within them: Eisenstein claimed that we read the compositions from left to right, in time with the musical chords!

Not only Disney but many filmmakers of the 1930s experimented with audiovisual fusion–Kozintsev and Trauberg in Alone, Pudovkin in Deserter, Mamoulian in Love Me Tonight, Renoir in the final danse macabre of Rules of the Game, and Busby Berkeley’s Warners and MGM musicals. Welles made Citizen Kane a feast of audio-visual echoes, as when the wobbly descent of Susan’s singing voice is matched by the flickering of a stage light that finally goes out.

With magnetic and multichannel recording in the 1940s and 1950s, filmmakers could compose very complex sound mixes, and later improvements offered still more possibilities. After Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, we expected a movie to be an immersive audiovisual experience, like the light show at a rock concert. Scorsese, especially in Raging Bull and Goodfellas, created powerful mergers of music, sound effects, camera movement, and character movement. So did the Hong Kong kung-fu films of the 1970s and early 1980s. The spellbinding languor of Wong Kar-wai’s films stems largely, I think, from their synchronization of color, slow motion, drifting camerawork, and evocative music.

The avant-garde has pursued more elusive synchronizations of sense modes.The idea of synthesis was floated in the silent era, when experimenters like Oskar Fischinger used musical pieces to anchor their abstract imagery. This tendency has resurfaced in music videos, some of which (Michel Gondry’s in particular) have clear links to the experimental tradition. So too do the shorts and features of Peter Greenaway, especially in his collaborations with composer Michael Nyman. In a film like Prospero’s Books, Greenaway seems to follow Eisenstein in imagining a Wagnerian synthesis of writing, image, and sound.

By contrast, Godard explores all manner of unpredictable junctures between image and sound, with the tracks teasing us but always avoiding a complete coordination. Somewhat similar are the disjunctive image/sound juxtapositions in Peter Kubelka’s Unsere Afrikareise and Bruce Connor’s Report, or the inverse and retrograde organizations of Structural Film soundtracks like Michael Snow’s Wavelength and J. J. Murphy’s Print Generation.

Film academics have begun to analyze image/ sound juxtapositions, studying the development of early talkies and more recent Dolby technology. Arguably, film researchers now pay more attention to music than they pay to imagery. By contrast, most journalistic critics ignore a film’s soundtrack, except occasionally to comment on line readings and pop tunes. As for ordinary audiences, perhaps DVD and home theatre technology have made people more aware of how movies can saturate our senses with audiovisual correspondences.

Three waivers

1. Once I floated these distinctions in a seminar discussion, and a participant mentioned that cinema was also an emotional art. I’d agree that a lot of cinema aims at arousing feelings, but this idea can be found in all the dimensions I traced. Each conception of film favors different means of stirring up emotion.

For example, the photographic approach holds that recording and revealing the world is the most effective way to move spectators, while the narrative approach favors stories as the means to that end. The performance-based approach trusts that we’ll react empathetically to the emotional states displayed by our fellow humans, but the visual-art approach says that cinema can arouse feeling by manipulating pictures in time and space, perhaps even pictures that don’t show any people at all. Eisenstein argued that synchronization of senses was the most powerful form of emotional stimulation, creating in the viewer an “ecstasy” comparable to religious fervor. Beyond these general considerations, it would be worthwhile to tease out the different sorts of emotion that each perspective tends to emphasize.

2. Someone else might ask: What about other analogies? Filmmakers and critics have sometimes compared cinema to music or poetry. Shouldn’t those arts be added to the list?

I think that these comparisons show up principally within the broad idea of film as a pictorial art. The French Impressionist directors of the silent era thought that they were making “visual music,” and Brakhage and Deren’s conceptions of the “film lyric” were mainly pictorial. (See girishshambu for thoughts on the latter.) I’d suggest that filmmakers in the pictorial-art camp have looked to these adjacent arts for models of patterning (meter, rhythm, motif development) and imagery (metaphor and subjective states in lyric verse). Filmmakers are also attracted to the idea that music and poetry tend to be suggestive rather than explicit, conveying powerful feelings in elusive and open-ended ways.

Polemically, filmmakers often conjure up these musical and literary analogies to counter the mainstream cinema’s emphasis on narrative and performance. If we think of film as lyric or rhapsody, story seems less important. The same thing goes, I think, for thinking of film as moving architecture or kinetic sculpture; the analogy again targets film’s pictorial dimension and its non-narrative potential.

3. To think of film as having an affinity with another art form isn’t to say that they’re identical. Thinking of cinema as a performance-based art, for example, doesn’t commit you to saying that film acting is the same as theatrical acting. Instead, thinking along these lines seems to create a first approximation, an initial comparison that lets you move on to notice differences. Once you consider film as a pictorial art, you can then ask in what ways it differs from other pictorial arts, or in what ways this particular movie transforms or reworks the techniques of painting. Ballet Mécanique, which we analyze in Film Art (pp. 358-366), owes a lot to cubism, but its imagery isn’t identical to what Picasso, Braque, and Gris came up with on canvas. All of these analogies seem to work best as frameworks for sensitizing us to both similarities and differences between film and other arts.

And . . . so?

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me.

Each conception of film art harbors a good portion of truth. Each may fail to cover all of cinema, but for certain types of film, or particular movies, some are likely to be more helpful than others.

For example, it’s useful to consider David Lynch as making audiovisual works, in which blinking lights or grooves in pine planks seem uncannily synchronized with throbs and hums and Julee Cruise vibrato. Very often story and acting seem to precipitate out of an enveloping pictorial/auditory atmosphere. This isn’t to say that you couldn’t study narrative or performance in Lynch films; it’s just that taking up the audiovisual-mix perspective will throw certain aspects into sharper relief.

You could also argue that the Hollywood studio era blended many of these appeals into a single strong tradition. Story was important, but so was performance. Visual style was often striking, but so too was an expressive soundtrack that went beyond simply recording the dialogue. Sound effects, musical scores, and verbal hooks between scenes created imaginative resonances with the image track. Contrariwise, we can see some avant-garde traditions as taking a purist tack. In several of his films, Brakhage reduces narrative, purges performance, and bans sound: we have to engage wholly and solely with a pictorial experience.

Just as we can distinguish film traditions along these dimensions, we can contrast writers and thinkers. Some critics are very good in pinning down performance qualities, others excel at plot dissection or visual analysis. Arnheim is sensitive to pictorial values but he has little to contribute to understanding storytelling.

Bazin and Eisenstein are attuned to several of the dimensions I’ve traced out. Bazin’s interest in cinema’s photographic basis also alerted him to pictorial possibilities, like deep-focus and camera movement. Eisenstein, famous for his ideas on cinema’s visual dimension, was as I’ve said interested in sound as well. He was no less concerned with film performance, which he conceived as expressive movement (to be synchronized with properties of the image and the soundtrack). But he voiced almost no interest in narrative or photography.

I warned you that this blog would be theoretical, but I hope the takeaway message is clear. Cinema is teeming with artistic possibilities, and each of these frameworks can illuminate certain areas of choice and control. We don’t need to pick a single creed to live by, but we deepen our understanding of film by being sensitive to as many as we can manage.

Uncle Walt the artist

From Robert Benayoun, Le Dessin animé après Walt Disney.

The epos of Chaplin is the Paradise Lost of today. The epos of Disney is Paradise Regained.

Sergei Eisenstein

DB here:

I’m not qualified to write a comprehensive or penetrating review of Neal Gabler’s biography Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. For that you can go to Mike Barrier, one of our finest historians of US animation. Barrier’s own Disney biography will come out this spring, with apparently little overlap with Gabler’s.

I’m not qualified to write a comprehensive or penetrating review of Neal Gabler’s biography Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. For that you can go to Mike Barrier, one of our finest historians of US animation. Barrier’s own Disney biography will come out this spring, with apparently little overlap with Gabler’s.

I found Gabler’s book a thorough, somewhat cautious bio, even-handed about Disney and judicious about such controversial matters as Walt’s reputation as an anti-Semite. A lot of it reads like a notecard book, with quotes, paraphrases, and commentary dutifully snipped and pasted in, packing each paragraph. Chronology, not concept, rules. Still, I learned a lot.

Gabler’s book reminded me how much I admire Disney films. The attachment started–as for most of us–in childhood. Peter Pan (1953) was the first one I remember seeing in a theatre, but when I saw a reissue of Snow White later, parts looked so familiar that it must have impressed itself on me at an earlier time. Of course it still scared the hell out of me.

In 1973, when I was doing dissertation research in New York City, I attended a massive Disney retrospective at MoMA. As a twenty-five-year-old bearded guy among moms and kids, I felt obscurely criminal just being there, like a character in a Patricia Highsmith novel. But what I saw, in excellent prints, showed me that Disney was important on both cultural and artistic levels. So I designed a Disney unit into my first Introduction to Film course, taught here at University of Wisconsin–Madison to 300-400 souls whom fate cast my way.

I wanted to talk about film’s relation to society, and Disney was a touchstone for all my students. No matter where they came from, they knew Mickey, Donald, Snow White, Fantasia, and the rest. I showed early films, like Flowers and Trees, The Band Concert, and The Old Mill, as well as a True-Life Adventure nature doc, and the extraordinary Trip through the Disney Studio which was originally attached to The Reluctant Dragon. Students were able to see, I hope, how the ideology at work in Disney films could shape a conception of the world, of American life, and of their childhood.

Our assigned reading was Richard Schickel’s The Disney Version (1969); it’s a coruscating study, perfectly crystallizing that era’s feelings about Disney’s debasement of popular culture. At about the same time, Armand Mattelart’s Marxist critique How to Read Donald Duck was informing most film academics’ study of Disney. As Gabler indicates, intellectuals fell out of love with Disney in the 1940s. He handled labor disputes at the studio in a high-handed, paranoid way. He also seemed to personify the blandness of postwar consensus culture, and Disneyland became the theme-park equivalent of Norman Rockwell Americana. Even though hippies were turning on to re-releases of Alice in Wonderland and Fantasia, most cultural critics treated Disney pretty roughly. My friends and I goggled at Wally Wood’s 1967 Realist cartoon showing Walt’s whole gang engaging in a panoply of naughty sexual encounters.

Today the academic study of Disney is well-established, producing far too much for me to keep up with. A lot of it is cultural critique. For something funnier and even more scurrilous, see Carl Hiaasen’s Team Rodent. Despite all there is to read about Walt’s empire and its cultural consequences, I want something else as well.

Even when I was conducting my Disney Demystification Exercise, I tried to point out that these cartoons were artistically very strong. I still admire the powerfully emotional storytelling that, like that found in other fairy tales, preys so mercilessly on childhood fears. Schickel claims that after screenings of Snow White at Radio City Music Hall, the seats had to be cleaned because the Witch had scared kids into emptying their bladders.

Then too there’s the dynamism and grace of the animation, which remains unsurpassed. For Sergei Eisenstein Disney exemplified the contagious power of expressive movement on the screen. Many have disdained “Mickey-Mousing,” the close matchup between a film image and the accompanying music. But Eisenstein saw this as “synchronization of senses,” a primal, visceral unity that could move the spectator involuntarily. He sought this subconscious synchronization in his own sound films, and Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible show the strong influence of Disney.

Eisenstein was well aware of the delusional aspects of Disney, claiming that the cartoons lulled people into forgetting the harm done by capitalism. But as an artist, Disney was unique:

I’m sometimes frightened when I watch his films. Frightened because of some absolute perfection in what he does. This man seems to know not only the magic of all technical means, but also all the most secret strands of human thought, images, ideas, feelings…. He creates somewhere in the realm of the very purest and most primal depths.[1]

Disney’s art seems magical, but if it’s not a miracle, we ought to be able to study it systematically. How?

Felix in Hollywood (1923)

Felix in Hollywood (1923)

For the Jung at heart

Gabler’s is a sturdy, readable volume teeming with fascinating background material. As an EEG of the ups and downs of the studio, it’s extremely valuable. Gabler also aims to give a portrait of Disney the visionary, a man of boundless Protestant energy who sought to take animated film to ever higher levels. I think the portrait is disappointing, though, in its reliance on conventional psychobiography and Zeitgeist explanations.

Disney, Gabler claims, was dominated by a psychological drive to create a world wholly of his own. He was a control freak. “It had always been about control, about crafting a better reality than the one outside the studio, and about demonstrating that one had the capacity to do so. That was what Walt Disney provided to America–not escape, as so many analysts would surmise, but control and the vicarious empowerment that accompanied it.”

Commentators have long noted that Disney expanded the films’ fantasy world in his theme park. Just as films idealized reality, “so would Disneyland, the creation of a wounded man who expunged what he saw as the darker passages of his past by devising a better world of his imagination, though one that was obviously colored by the images of Hollywood.”

One has to wonder whether this characterization is particular to Uncle Walt. Lots of artists, from architects and topiary gardeners to designers of world’s fairs, have sought to create imaginary worlds over which they rule. Balzac, Faulkner, Lewis Carroll, and J. R. R. Tolkien conjured up imaginary realms populated by dozens of their own creatures. Graphic artist Ho Che Anderson writes:

For the control freak, there are few places better than comics. . . . Pick up a pen and piece of paper and you too can effectively play God. I suspect this love of God-play is the blood that keeps the hearts of many a cartoonist beating.[2]

Moreover, is the desire to build a parallel world necessarily a sign of a wounded past, or dark imaginings? Maybe it’s just one awesome creative challenge for ambitious artists. Granted, Disney took this impulse in a particular direction, toward a vision of life combining technical progress (the multiplane camera, Tomorrowland) with idealized notions of small-town community. But then we have to explain those idiosyncratic factors too.

Gabler goes the psychological route, but we could balance this account with cultural factors in Disney’s immediate milieu. There was the rise of the Technocracy movement. There was Hollywood’s belief that filmmaking would progress through new technologies. There was growing evidence during and after World War II that America’s might would be built on new machines. (One of the most hair-raising movies I saw at the 1973 MoMA Disney fest was Victory through Air Power, an educational short arguing for investment in airborne warfare.) Disney was, along many dimensions, a techie impresario, the Steve Jobs of his day, complete with his unique reality-distortion field.

The other big-picture explanation Gabler offers is a Zeitgeist model. Disney represents the American imagination. By tapping into Jungian archetypes, his 1930s films could both “capture and then soothe the national malaise.” More generally: “In both Disney’s imagination and the American imagination, one could assert one’s will on the world . . . . Indeed, in a typically American formulation, nothing but goodness and will mattered.” Disney’s desire to retreat into a controlled world echoes his country’s self-absorped conception of itself.

Despite these claims, Gabler doesn’t dwell much on the ways the studio seized what he calls “the American psyche,” perhaps because he senses that such explanations tend to be uninformative. One can grab almost any cluster of traits, find them in American popular art, and assert them as quintessentially American. This is how mainstream journalists make current Hollywood releases worth writing about: treating them not as artworks with distinctive appeals and a place in traditions and histories, but as reflections of whatever immediate social trends the writer chooses to pick out.

I won’t extend my criticism of Zeitgeist explanations here; it’s developed in the first essay in my forthcoming Poetics of Cinema. I’ll just say that I think we need more precise explanations than we get from easy juxtapositions of this or that film and some collective mood, sentiment, fantasy, or anxiety that we postulate as existing out there. Is there an American psyche? I’m not convinced.

An alternative to psychological speculation and Zeitgeist thinking is to look for more immediate causal connections. For example, Gabler traces how, around 1932, Disney began a new division of labor among his staff. He created a fairly strict set of specialties (story, gags, continuity sketches) and a chain of command in which head animators would become directors, overseeing particular projects. What’s the explanation of this change of policy? For Gabler, the new rationalization reflects not only the need to manage a bigger staff but also Walt’s effort in “reinventing and perfecting the system under which animations were produced.”

Gabler doesn’t mention that reorganizing the division of labor was going on throughout Hollywood at the same time. Most major studios were moving from a central producer system (this parallels the previous Disney lineup, with Walt at the top) to what Janet Staiger has called the producer-unit system, in which each man was charged with several productions.[3] Mentioning this doesn’t take away from Disney’s resourcefulness, but it does indicate that models for organizing his company were emerging right under his nose.

Similar issues could be examined by looking at Disney’s place in the overall ecology of Hollywood, as the premiere supplier of short subjects. His firm, Douglas Gomery argues, kept RKO afloat for many years. Gomery’s Hollywood Studio System: A History gives a cogent account of Disney’s role in the industry, and he goes somewhat beyond Gabler in tracing the studio’s emergence as in the 1950s as the prototype of modern conglomerate filmmaking.

Life in the cel

For Gabler, what made Walt reorganize production, and indeed what made him do nearly everything, was his obsessive pursuit of “quality” animation. But this quality itself remains fairly mysterious.

For Gabler, what made Walt reorganize production, and indeed what made him do nearly everything, was his obsessive pursuit of “quality” animation. But this quality itself remains fairly mysterious.

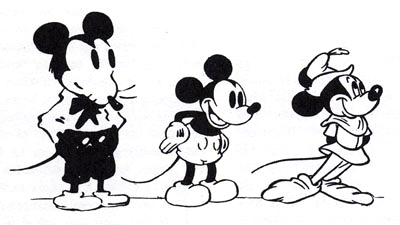

Gabler indicates that Disney moved away from the “rubber-hose” style of most cartoons, with their balloon heads, swollen paunches, and elastic arms and legs. (Even the clarinet goes limp in Harman-Ising’s A Great Big Bunch of You, from 1932, shown here.) Floppy limbs were fairly easy to animate. Gabler briskly summarizes Team Disney’s well-known innovations in naturalism, such as the studio’s emphasis on anatomy and life drawing, the breakdown of gestures, complex perspectives, and the rotoscoping of human figures.

Yet Gabler, a former movie critic for television, oddly doesn’t engage with the result of the technical innovations. He summarizes how journalists, critics, and academics have interpreted the movies’ cultural impact, but what he thinks about them as movies, rather than social or psychological symptoms, is almost completely suppressed. Does he admire Snow White or Dumbo or Pinocchio? Does he hate them? Has he studied them in preparation for the book? You will find more sensitive appreciation and critique in Leonard Maltin’s The Disney Films than in all of Gabler’s doorstop tome.

Gabler implicitly acknowledges the technical achievements of Snow White, Pinocchio, Fantasia, Dumbo, and Bambi, but after that he merely chronicles release after release with deadpan indifference. For example, he offers us nothing on the brilliant character animation of Song of the South (1946)–a film no longer in circulation because of its racial stereotyping.

Gabler follows tradition in suggesting that the UPA studio movies challenged Disney’s hyperrealism, but Disney was already moving toward something quite stylized. Gabler doesn’t observe the zesty play with color and line of Melody Time‘s “Blame It on the Samba” episode (1948). Eisenstein would have been pleased to see that the handling of Donald and Jose literalizes the metaphor feeling blue.

Working with lower budgets in the 1940s, the animators let their imaginations run wild. What a pleasure it must have been for Ward Kimball to come up with the funhouse nuttiness of the Serape song in The Three Caballeros (1945).

Kimball must have been quite a character; his parody book Art Afterpieces doesn’t spare the studio’s creatures. More generally, when Disney animators turned to illustrating pop music, they didn’t abandon the wilder sides of Fantasia.

There would be several fruitful ways to study the Art of Uncle Walt. One would require what I call rhapsodic criticism, writing that tries to evoke the movie’s look and feel through energetic, sensuous description. (This is, I think, what Susan Sontag meant in calling for “an erotics of art.”) Here is Don Crafton on the Felix the Cat cartoons:

Perhaps the most appealing aspect of Felix was his use of expressive body parts–a tail that forms gratuitous curlicues when he walks, or ears that click together like scissors. . . . He can mold himself into a mantel clock and have his nose mistakenly wound up; his tail can be an umbrella, a sword, or a clarinet, or Chaplin’s cane. He can use the tail as a bow to play a tune on his whiskers, then take one of the rising notes and use it for a doorkey. His skin is detachable. In Felix Trifles with Time (1925), a tailor flays him, then outfits a client with his pelt. When the man goes swimming, “naked” Felix retrieves his hide from the beach. [4]

In brief compass Crafton brings Felix alive for us. You don’t have to love Disney to write this way about his films; you do need a good eye, some pluck and gusto, plus a gift for language. Nothing like this is to be found in Gabler’s book.

Another way to get closer to Disney’s art is to just look at things more analytically. How does Disney create that expressive movement that Eisenstein admired? Partly, it seems, through having his figures move all over, and at the same instant. Reacting to a line of dialogue, a character can twist his waist, arch his back, swivel his shoulders, lift his head, arch his eyebrows, and raise a forefinger–all in a second or two. Two successive frames from Melody Time show Johnny Appleseed’s guardian angel in action, working his legs, arms, shoulders, jaw, and eyeballs simultaneously.

This is far from the minimal animation to which we became accustomed in the TV era. Treating gesture as a taut, rolling movement helps give Disney characters their unique volume and springiness, so different from the flabby postures of the rubber-hose style.

Or consider pacing, at which the Disney cartoons excel. Most studio animation of the period, constrained by smaller budgets than Disney had, speeded up production by filming each frame twice. That way only 12 cel drawings were needed for the 24 frames that consumed a second of film. One way Disney achieved expressive action, and the high quality to which Gabler refers, was to devote single frames–and cels–to details of particular movements. This choice, though expensive, allowed for exact adjustments in rhythm.

Sometimes there’s more than one movement per frame. You can occasionally find this strategy at work in other studios’ cartoons too, as Kristin has explained in an essay she mentions elsewhere in our blog. But Disney’s animators certainly used the technique with great panache. When Johnny, balancing on a branch, is caught in a rain of apples, he sweeps them up with lighting speed–a deft swirl made possible by multiplying character poses on each cel. If that means giving Johnny many arms and even detaching his hands, so be it.

Johnny’s arms and hands proliferate more quickly and widely as he scoops up the apples, but their number is reduced as he gathers them in to his chest, so the rhythm accelerates and decelerates. Through trial and error Disney’s animators learned that rather strange single images will look exactly right on the screen; these men were practical perceptual psychologists.

There are so many aspects of Disney’s art that need attention: the skill with line and contour; the sort of soft caricature that some consider cutesy but has enormous bounce and vibrancy; the ingenious use of color; and of course, Eisenstein’s “synchronization of senses” between image and music. There’s also Disney’s appropriation of developing live-action techniques, as in the proto-Wellesian crane shot in Pinocchio

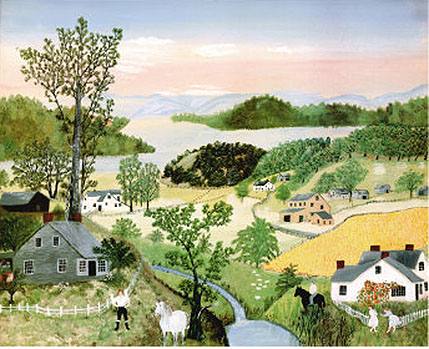

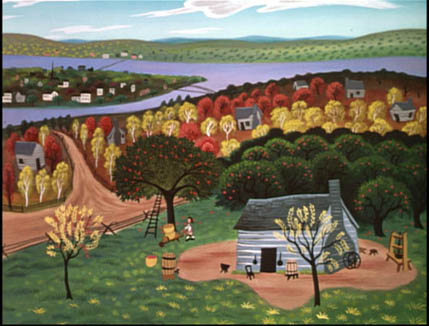

One could also study the studio’s borrowing of high-art motifs and styles. Instead of dismissing the 1940s and early 1950s Disneys as greeting-card kitsch, we can note that they evidently borrowed from the likes of WPA landscape art, American regionalist painting, and the naive-art look of Grandma Moses. (Her painting A Beautiful World, 1948 resembles Disney’s Johnny Appleseed of the same year.)

I’m a duffer in animation matters, so I’ve merely indicated some areas that intrigue me. The key source on the studio’s craft practice remains the gorgeous book The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation (1981, rev. 1995), by two of the great Nine Old Men, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnson. And I expect lots of discoveries in years to come from experts like Barrier, Maureen Furness, Paul Welles, Norman M. Klein, and many others. Since Gabler draws heavily on the research of others, often without naming names, he might have borrowed a bit more from scholars of animation aesthetics.

In fact, you could argue that without the artistic imagination displayed by Disney and his brilliant staff, these films couldn’t have captivated the American imagination. Whatever that is.

[1] Eisenstein on Disney, ed. Jay Leyda, trans. Alan Upchurch (Calcutta: Seagull, 1986), 2.

[2] “Career Tips for Control Freaks,” in The Education of a Comics Artist, ed. Michael Dooley and Steven Heller (New York: Allworth, 2005), 124-125.

[3] Janet Staiger, “The Producer-Unit System: Management by Specialization after 1931, in David Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), 320.

[4] Donald Crafton, Before Mickey: The Animated Film 1898-1928 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993; orig. 1982), 327, 328.

Lotsa pictures, lotsa fun

1. “It hypnotizes the viewer,” writes Paul van Yperen of the Nerven poster he printed in the new issue of the Dutch journal Skrien. Paul sent it to me because I wrote about Robert Reinert’s film in my forthcoming collection of essays, Poetics of Cinema. Nerven is a disorienting, highly experimental work. Released in 1919, before The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (early 1920), it might have become a prototype of German Expressionist cinema if it had been widely seen and preserved by archives. Nerven, along with Reinert’s other major film Opium (1919) would make a wonderful twofer on a DVD release.

2. We’ve set up an archival supplement to our textbook, Film Art: An Introduction elsewhere on this site. It includes analyses that appeared in earlier editions but were cut for reasons of space or film availability.

The pieces discuss Stagecoach, Hannah and Her Sisters, Desperately Seeking Susan, Day of Wrath, Last Year at Marienbad, Innocence Unprotected, Disney’s Clock Cleaners, Tout va bien, High School, and Hitchcock’s first Man Who Knew Too Much. DVD has made nearly all of these films easily accessible, so we hope reviving the essays will be of use to students and free-ranging viewers.

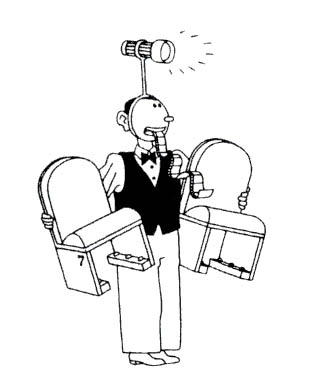

3. Check out the nifty interview with Joost Swarte in the new issue of The Comics Journal. Excerpts are here.

Swarte is the greatest heir to the Belgian-Dutch “clear-line” style, and his witty cartoons have become worldwide classics. Kristin and I have been collecting Swarte books and posters since the 1980s, although as his projects have expanded to building design his output of images has waned (except for the occasional item for The New Yorker).

Swarte has much to say about Hergé’s mastery of visual storytelling, claiming that the Tintin tales are like little movies.

Swarte has much to say about Hergé’s mastery of visual storytelling, claiming that the Tintin tales are like little movies.

He was very much influenced by cinematographic laws. Where do you place your camera? Is the hero always coming from the left? What’s the relation between foreground and background? All sorts of terms that he used come from cinema.

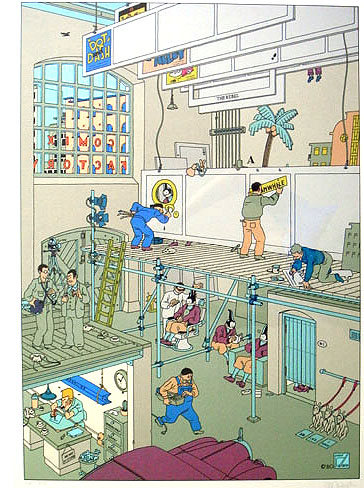

Swarte too has an affinity for film. One of his best pictures, Comic Factory, treats cartooning as if it were moviemaking. Our cartoonist labors in lower left, the girder of a deadline hanging above him, while a producer (with cigar) seems to be telling the photographer how to shoot the panels. Jopo de Pojo gets spruced up for his close-up while his doubles (or clones) lounge around. Set designers and scene painters labor over the panels.

Swarte’s teeming street scenes, usually including dog turds, are filled with glimpsed gags in the manner of Tati. Not surprising, then, that under the skilful questioning of David Peniston, he confesses his admiration for Play Time. New collections of Swarte’s comics are apparently forthcoming, in several languages, in 2007. By the way, the same issue of the Journal has a nice appreciation of Cliff Sterrett, another comics genius, creator of the amiable, lovely, and quite nuts Polly and Her Pals. Click here for a nice blow-up sample.

4. Speaking of cinema in still images: One of Eisenstein’s favorite pastimes was to find anticipations of film in earlier media. He loved the fact that Myron’s discus thrower was portrayed in an impossible position, with the limbs indicating different phases of the action.

This and similar items were inspirations for the plate-smashing scene in Potemkin.

So in a holiday spirit, I’d ask: what would Eisenstein have made of this painting, which I saw again last summer in London’s National Gallery–Botticelli’s Mystic Nativity of 1501?

Reproduction, especially this tiny, doesn’t do the picture justice, but you should be able to see how the symmetry of the composition is broken by the slope up to the central scene of Mary and the mule bending over the baby. As with Swarte cityscapes, there’s a lot to dig for. Angels on left and right of the manger direct the Magi to the main action, and in the lower section angels kiss men while devils dive into the fissures of the earth.

Key for students of cinema, though, is the whirling dance of the angels in the upper third of the picture. Strictly speaking, they all seem out of step, no two in sync. But then you notice that each is executing a slightly different phase of one continuous movement, as if Muybridge had captured a single dancer’s circling trajectory with his early stop-motion photography. Angel Locomotion, he might have called it; but Botticelli got there before him.

Good Actors spell Good Acting

Kristin here–

I suppose all movie-lovers have favorite quotations that become part of their everyday conversation. Norman Bates’s “One by one you drop the formalities” fits a surprising number of situations. The film-studies professors here in Madison often communicate with each other using lines from Howard Hawks films, especially Rio Bravo. “Let’s take a turn around the town,” “We’ll remember you said that,” and, of course, “It’s nice to see a smart kid for a change.” Any time David or I get a particularly small royalty check, we echo Hildie Johnson’s sour “Buy yourself an annuity.”

One of our favorite everyday-life quotations comes not from a movie but from the endlessly hilarious SCTV series. It’s a skit in which Steve Roman (played by John Candy) promotes his new TV show, Juan Cortez, Courtroom Judge. He explains part of its appeal: “It’s got good actors, and that spells good acting.” (Fifth season, episode 110, for you SCTV buffs.)

Almost invariably we use this line when we come across one of those films that receive highly positive reviews largely because of one great performance. You know the kind: Charlize Theron in Monster, Halle Berry in Monster’s Ball, Hillary Swank in Boys Don’t Cry, and more recently Forest Whitaker in The Last King of Scotland and Helen Mirren in The Queen.

Usually I avoid such films, because the reviews tend to plant the idea that they are primarily actors’ vehicles. I enjoy good acting as much as the next person, but I want the rest of the film to be interesting as well.

Are there any film classics that are truly great solely for the acting? It’s hard to think of any. Maybe The Gold Rush, which is stylistically fairly pedestrian but which is redeemed by Chaplin’s inspired performance. Maybe Duck Soup, also quite undistinguished for much of anything other than the Marx Brothers cutting loose without being saddled with the sort of plots involving young, singing lovers that MGM would soon foist upon them. Maybe a few others. Usually, though, we tend not to think of a performance, however dazzling, as adding up to a great film.

Still, when I think of some of the finest performances ever put on film, I think of Falconetti in La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc by Carl Dreyer. There her luminous portrayal of determination and religious devotion is embedded in an equally extraordinary film, with its minimalist sets by Herman Warm, its insistently tight framings on faces, and its vertiginous camera movements. Similarly, Nicolai Cherkasov as Ivan the Terrible in Eisenstein’s film poses against the shapes of the settings, moves to the music of Prokofiev, and casts great shadows on the walls. Buster Keaton, though not as popular in his day as Chaplin, had an instinctive feel for both the flat space of the screen and the depth of the represented image, and his films are exciting in themselves and not simply as backgrounds to his clowning.

We’re now well into the time of year when the studios bring out the films they hope will garner Oscar nominations and even wins. Journalists covering film, reviewers and feature writers alike, can get some copy out of speculating about the Oscars. That speculation seems to start earlier and earlier each year, like Christmas shopping. Given that the public is a lot more interested in acting than cinematography or screenwriting, perhaps it’s not surprising that reviewers focus so much on star turns. But in doing so, do they slight other aspects of those films? Do they unfairly scare off those of us who are wary of Oscar bait?

I decided to do my part for the good of the blog and see The Queen. I’m not a huge fan of Stephen Frears, but My Beautiful Launderette is a good film, with an early sympathetic, non-sensationalized view of homosexuality in London. Mary Reilly is not exactly a masterpiece, but it’s worth watching and has been underrated. Its failure may have been due in part to the fact that most reviewers focused in on whether Julia Roberts could handle a dramatic role in a thriller and then found her wanting.

Anyway, The Queen turned out to be an entertaining, well-made film. Yes, Helen Mirren is remarkable as Queen Elizabeth II, and she may well win an Oscar for her performance. Yet equally interesting is the fact that Frears almost entirely avoids the “intensified continuity” style that David has analysed in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

The film is basically pretty simple, moving back and forth between the royal family and the newly elected Tony Blair surrounded by his wife and staff. The royals notoriously reacted to the death of ex-Princess Diana with stony silence despite the huge outpouring of public grief. It’s clear from the indifference and even hostility toward Diana that the members of family’s older generations voice in private, they do not feel a comparable grief. But Blair strives to maneuver the Queen into going public and expressing a sense of loss.

Frears set out to contrast the two worlds stylistically. The scenes with the royals are shot in a classical, non-intensified style. Distant shots to establish space, two shots for face-to-face conversations, over-the-shoulder shot/reverse shots as the dialogue unfolds. The framing seldom goes in for the tight close-up but stays in medium shot or medium close-up. The cutting is slow relative to the current norm, as befits both the subject and the style. One reason people are so impressed with Mirren’s performance may be that it is not made up of a bunch of different shots stitched together. She has shots that allow her to develop a reaction or attitude slowly.

And best of all, the camera doesn’t glide toward or around the characters. It stays put unless it needs to perform one of its traditional roles: reframing to keep characters balanced, and following the characters as they move from one room to another or walk along a country track. The lighting is suitably subdued and directional, another reversion to a more classical age.

A great deal is currently being made of Steven Soderbergh’s reversion to 1940s Hollywood style in The Good German. Frears isn’t quite as systematic, perhaps, but the royal-family scenes in The Queen look very 1950s to me.

In contrast, the Tony Blair scenes were shot with a handheld camera, to convey the bustle of his staff and the more casual situation. Even so, the camera movement is not obtrusive, and Frears still doesn’t constantly cut in for the tight close-up. Here, too, he keeps his camera back a bit, framing groups as they talk. The lighting tends to be brighter and more diffuse. The contrast works well, and yet Frears never pushes it in our faces and asks us to be impressed.

The narrative seems a little thin, mostly because, unlike most classical films, The Queen has only one plot line. There’s no subsidiary crisis, no romance, no other conflict. It’s just the royals versus the liberal prime minister’s team until one side cracks. Even the potential conflict that could have easily arisen from Blair’s wife’s anti-royalty position never goes anywhere. She’s mainly there as a sounding-board for him. And if the plot is thin, it is also refreshingly elegant in its simplicity.

One remarkable aspect of the plot is that none of the characters is treated as a villain. Blair’s position is held up as the wise one, yet the film goes to great lengths to suggest that the Queen and her family have reasons for behaving the way they do. Not excuses, but reasons. Fittingly, the film concludes with the Queen and her new prime minister walking out into the palace gardens for a stroll and a chat.

At the end, I didn’t feel that I had sat through a great performance. I had seen a good, entertaining, somewhat unusual, and skillfully made film that had a great performance in it. Indeed, it has a second from Michael Sheen as Blair, and the supporting players are fine as well.

But good directors spell good directing, and good cinematographers spell … You get the idea. Variety’s reviewers, it must be said, seem to have a mandate to mention style, since ever review comments at least briefly on the film’s techniques. But most critics give you no sense of the film as a whole—its narrative construction (apart from a plot synopsis) or its stylistic texture. It would be nice to see more rounded reviews.