Archive for the 'Directors: Feuillade' Category

Thrills and melodrama from the 1910s

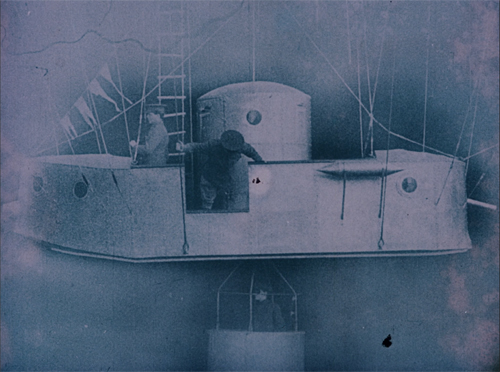

Filibus: The Mysterious Air Pirate (1915).

DB here:

Two new DVD releases remind us how 1910s filmmakers, unconstrained by realism, used the newish medium of film as a vehicle of charming, sometimes silly fantasy. One is the virtually unknown 1915 Italian feature Filibus: The Mysterious Air Pirate; the other is the famous but little-seen 1919 serial adventure Tih-Minh, by Louis Feuillade. The Filibus disc also contains a 1916 Italian feature Signori giurati… (“Gentlemen of the Jury,” here The Jury Decided). None seems to me a masterwork, but all are enjoyable and have something to teach us about the almost mad ambitions of an era discovering the power of long-form cinematic storytelling.

Lady with an airship

One thread over the life of this blog has been my nagging claim that the 1910s have not been widely recognized as the lively, innovative years they were. Yes, there was Griffith and Chaplin, but after that people tend to move on to rhapsodize about the glories of 1920s Europe and Hollywood. Of course many viewers appreciate the early work of Mary Pickford, William S. Hart, Buster Keaton, and Doug Fairbanks, and there are fans of great European directors like Sjöström and Feuillade, but even these luminaries are chiefly known for only a film or two.

Many scholars have labored loyally to bring to light major figures like Lois Weber and Albert Capellani, but these revelations remain niche tastes. Kristin and I have done our bit on the blog, in many entries and in the video lecture “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.” That suggests that today’s film industries, film culture, and artistic options have their sources in this era that, in retrospect, teems with creative possibilities.

The sheer imaginative variety of this output is brought home to me virtually every time I go back to see something recently discovered. My extended stay at the Library of Congress Kluge Center back in early 2016 was a smack on my head. In America, while filmmakers were elaborating the “continuity” system of storytelling (still with us), they were also pursuing side paths and fresh possibilities. (To check, start with “Anybody but Griffith” and move to later entries.) My discoveries complemented my years of visiting European archives to investigate both major auteurs and little-known films. (See the category “tableau staging.”) Now these releases, courtesy of Gaumont (Tih-Minh) and the cooperative efforts of Amsterdam’s Eye Filmmuseum, Milestone Film and Video, and Kino Lorber (Filibus) offer some new angles on the period.

Filibus centers on a supervillain who, unlike Fantômas or Dr. Gar el-Hama, is a woman. Like them, she’s a master of disguise, appearing as a genteel lady but also a suave gentleman and a sleek masked marauder. She steals jewelry through the usual methods: casing a household, sizing up the spoils, and confounding the authorities. What sets her apart is that she travels in a midsize airship that allows her to move swiftly from place to place and lower herself in a gondola to the numerous balconies that give access to the treasures.

She’s also adept at outsmarting the detective Kutt-Hendy. Exploiting the current public fascination with pseudo-scientific detection, the film shows her capturing his fingerprints on a rubber glove, and then leaving them at the scene of the crime. But she has old-fashioned tools as well, including a mysterious knockout scent.

Capably if unspectacularly directed by Mario Roncoroni, the scenes are mounted in straightforward ways for the period. Cutting, as you’d expect, consists largely of linking scenes or occasionally enlarging a detail we need to see, such as a camera inside the eye of a cat statue.

Within dialogues, simple axial cuts give us access to actors’ expressions. Sometimes Rondoroni moves a figure closer to the camera without motivation, simply to show us things more clearly, before the figure then retreats a couple of steps.

This is an anachronistic device, common in much earlier films. Most directors of the period motivated such movements by having something in the foreground that would draw the actor nearer to the camera.

The preposterousness of it all is well-recognized by everyone concerned, I think. The most impressive set, a parlor boasting Egyptomania galore along with the supposedly ancient but highly inauthentic cat sculpture, gets a good workout during the crime and the investigation. What remains, though, is Filibus’ unique transport system that allows her to bypass all the driving down roads and clambering up building facades we get in Feuillade. A blimp and a basket do the trick, leaving Filibus to sail off to her next conquest.

The film was noted as over-the-top in its own day. One critic wrote: “Great drama of adventure? Say rather a great cinematic mess of adventures. . . .” Evidently the tackiness of the special effects was evident as well. But we’re lucky to have it as one more document of the sometimes overstrained efforts to pack fresh sensations into the still-emerging format of the feature film.

Opium and murder

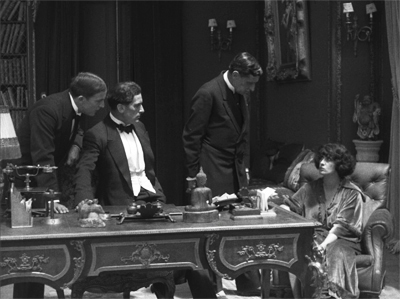

Signori giorati… is more orthodox and, I think, more satisfying as a story. A classic salon melodrama with plenty of diva posturing, it shows the decadence of the very rich brought to account. The adventuress Julienne (originally Lina) Santiago has seduced Dr. Nancey into setting up a plush opium parlor. Every night, the rich come to the “House of Forgetfulnesss,” where Julienne and the doctor blithely pick their pockets. When the police get interested, Julienne betrays Nancey and bolts, later to take up with one of their clients, the Marquis de Vallier. He resolves to marry her and brings her home to meet his daughter Helène (Valeria Creti, aka Falibus) and her husband. A deadly intrigue begins.

Signori giorati… shows the pluralism of visual expression of the period. While depth staging isn’t much developed here, the vast opium-den set carries the action far into the distance, where Julienne, masked, awaits the Marquis (above). Later, lurking in the reeds, Julienne stalks Helène’s husband.

Courtroom scenes in 1910s films are surprisingly varied, and director Giuseppe Giusti offers an unusual array of angles on the action.

A split-frame flashback illustrates courtroom testimony.

None of these moments is extraordinary for the period, but they nicely exemplify visual strategies becoming normalized in European cinema. Likewise, the somewhat awkward linkage between the first section around the opium den and the second on the Vallier estate show the need to tighten up the overall arc of the narrative–a problem European films would face for some years.

An unusual feature of the disc is the inclusion of five short films from the Amsterdam premiere of Filibus in 1918. This was made possible by the Eye Filmuseum’s splendid collection of early films from around the world shown in the Netherlands by the distributor Jean DeSmet. There’s also a brief short giving background to that collection.

From Vietnam to the Riviera

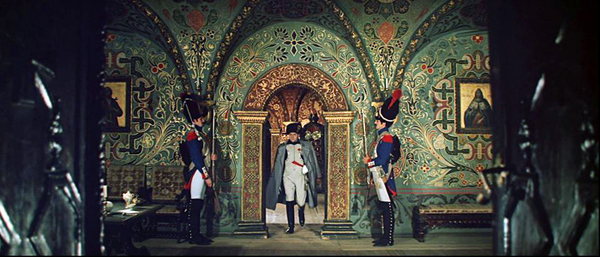

Tih-Minh (1919) followed in the wake of Louis Feuillade’s successful serials Fantômas (1913-1914), Les Vampires (1915-1916), Judex (1917), and La Nouvelle mission de Judex (1918). Released in installments from February to April 1919, Tih-Minh followed an important Feuillade feature, Vendémiaire, released in January. Throughout the same years Feuillade signed dozens of shorter comedies and dramas. Not only was he an efficient director on a scale we can hardly imagine today, but he had a powerful incentive: Gaumont gave its top directors a percentage of a film’s revenues, and Feuillade’s salary made him wealthy.

The plot revolves around a treasure supposedly hidden in Indochina. But where? A Sanskrit book contains notes, in code, about its whereabouts. The explorer Jacques d’Athys has unwittingly acquired it during his last expedition. Learning this, former German spies Kistna the “Asiatic” and Dr. Gilson recruit the hapless Marquis Dolores (above) and target Jacques’ villa in Nice. Jacques has also brought back the delicate young woman Tih-Minh (also above), daughter of a French colonist murdered, it’s revealed, by Gilson (né Marx!). The complications around the coded message lead the gang to a series of raids on the household, usually involving efforts to kidnap Tih-Minh. The efforts are resisted by our heroes–Jacques, his loyal servant Placide, the maid Rosette, and the British diplomat Sir Francis Gray.

Tih-Minh has an essentially comic structure. Unlike Fantômas and the Vampires, this gang can’t catch a break. Nearly every attempt they make, involving poisons, amnesia serum, hypnosis, and accomplices smuggled into the household, is thwarted, quickly or eventually. The ineptitude of Kistna’s gang is nearly matched by the passivity of Jacques’ team. They seem to wait around for the next assault, and when they prepare a trap, it usually fails. Only Placide, consistently suspicious, mounts countermeasures. Just when you wonder whether Nice has a police force, Jacques announces they can handle things best themselves.

Tih-Minh, a favorite of mine over the years, cracked a bit on this go-round. For the first time I found the opening installments dilatory and meandering. Feuillade is counting on our enjoying the company of these comfortably rich people and their rounds of coffee breaks, walks on the estate, and flower-picking in dazzling sunlight. And it is a kind of Bower of Bliss, which will eventually host three weddings.

Unlike the earlier serials, where he relies on composition in depth, here he favors lateral layouts. It’s as if the speed of the production pressed him toward lining up characters talking to one another in long-shot and medium-shot. Yet as I wrote about here, he varies the placement of heads in graceful waves.

These framings look forward to his later work’s “long-take” setups, broken only by dialogue titles.

The pacing and flashy visual invention pick up considerably in the later installments, when Feuillade hurls his cast through the magnificent landscapes of the Riviera. During the war, Gaumont moved substantial portions of production to the Victorine studios in Nice. Installing himself there in 1918, Feuillade takes advantage of everything in the neighborhood. You can sense his delight in finding ways to use the ocean front, rocky terrain, gorges, mountain crags, decrepit hilltop castles, luxurious estates, and hotel rooftops.

Pursuits across these forbidding spaces are a powerful attraction in their own right, and the second half of the film does not disappoint. For some shots the camera seems a mile away from the tiny human figures.

The actors accordingly give their all. Placide’s physical comedy is matched by his willingness to be beaten up, dropped from a great height, or folded up into a trunk lashed to an automobile roof. Flung into the ocean, he laughs it off.

Heroes and villains alike are willing to clamber around scaffolding and window ledges and crawl down the face of a mountain.

Mary Harald as Tih-Minh, apparently a wilting flower, seems game for anything as well.

We’re so used to stunt doubles for action scenes that we forget that long ago actors were athletes.

The vertiginous spaces and the bravado of the performers come to a climax when the chase moves to a zipline carrying rock from a quarry down into a valley. The villains dive into one of the gondolas and ride off to infinity. Undaunted, our heroes follow.

These shots, a rebuke to the cheesiness of Falibus‘ special effects, are alone worth the price of a DVD. And you thought Preminger treated actors roughly?

One more aspect of this release makes it a must-have for admirers of early film. It is one of the finest digital transfers of a silent film to disc that I have ever seen. Derived from a pristine negative, it is a perfect illustration of what 1910s cinema looked like at its best. (Thankfully, it is not tinted. Tinted versions often smudge original photographic detail.) We always knew that there was more on a 35mm orthochromatic film than we could see. Now we see it.

Gaumont’s disc of Tih-Minh is coded for all regions and contains optional English subtitles. Unless a US distributor picks it up, it will be available only at places like Fnac and Amazon.fr. University libraries and film departments should be able to get copies easily. Beware the bootleg version of the Belgian print (the source for the restoration’s intertitles) offered on eBay and elsewhere.

The Italian cinema of the 1910s was no less stylistically innovative than that of other nations, but the films haven’t achieved canonical status. Except for big, influential productions like Cabiria (1914), the output of this major industry has been overlooked, largely for reasons of availability. A breakthrough came with the superb collection, Italian Silent Cinema: A Reader, ed. Giorgio Bertellini (New Barnet: Libbey, 2013). My amateur forays into the area have yielded some nifty items, such as Fabiola (1918) and Maman Poupée (1919) and Il Maschera e il Volto (1919), as well as many I hope to share in the future.

Critical response to Filibus is sampled in Vittorio Martinelli, Il cinema muto italiano 1915, part 1: I film della grande guerra (Rome: Bianco e Nero, 1992), 190-192.

The standard study of Feuillade is Francis Lacassin’s magisterial Louis Feuillade: Maître des lions et des Vampires (Pairs: Bordas, 1995). (It’s a real bargain here.) I survey Feuillade’s staging strategies in Chapter 2 of Figures Traced in Light. A more general account of silent film staging in depth is in Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style.

Not incidentally, the Eye Filmmuseum offers a rich array of films from many periods, including the 1910s, for free viewing online.

Tih-Minh (1919).

Quality bingeing

Mon Oncle (1958)

Kristin here:

Or binging, if you prefer. Either is an acceptable spelling.

Streaming entertainment is one of the things that are saving our sanity as we sit in our homes. With the theaters closed and new movies either delayed or sent straight to streaming, movie critics, other journalists, and movie buffs are now making best-films-to-stream-during-the-pandemic lists a new and common genre across the internet.

Maybe you’ve been streaming a lot of TV series, even ones you’ve already seen, and are feeling a bit guilty about that. Maybe you’re longing for something more worthwhile to watch but wishing that that something would take up more time than your average feature film.

For those people, I offer a list of films to binge. These are either long in themselves or are split up into many parts that can be binged just like TV series. Others are stand-alones but can be grouped in meaningful ways.

My experience is that online disc orders are taking longer than usual. With Amazon prioritizing health and work-at-home supplies, Blu-rays are taking around two weeks rather than two days. (David and I, of course, count Blu-rays and streaming as part of our work-at-home requirements.) While you’re waiting, I’ll bet many of you have some of these discs on your shelves already and have always meant to make time for them. That time, lots of it, has arrived.

Serials

Many fine serials were made in the silent era, but Louis Feuillade remains the director that most of us think of first in relation to this format. His three great serials of the 1910s (not including, alas, the fine Tih Minh [1918]) are available on home video.

Fantômas (1912). 5 episodes, 337 minutes. Fantômas is available in Blu-ray and DVD from Kino Lorber. David wrote a viewer’s guide to it here.

Les Vampires (1915). 10 episodes, 417 minutes. Les Vampires is available on Blu-ray and DVD from Kino Lorber. As far as I can tell, it is streaming only on Kanopy (apart from unwatchable public domain pre-restoration prints).

Judex (1917). 12 episodes, 315 minutes. Judex is ordinarily available from Flicker Alley, though it is currently listed as out of stock. Amazon has 5 left. For maximum bingeing opportunities, watch all three serials in a row and then stretch them out with Georges Franju’s charming remake, Judex (1963) for an extra 98 minutes (it’s $2.99 to stream it on Amazon Prime).

Miss Mend (Boris Barnet, 1926). Three episodes, 235 minutes. The only American-style serial from the Soviet Union that I know of, or at least the only one easily available. I wrote about it briefly when it first came out from Flicker Alley. You can still get it from Flicker Alley or Amazon. We wrote briefly about it here.

Le Maison de mystère (Alexandre Volkoff, 1923). 10 episodes, 383 minutes. I’ve already written in some detail about this long-lost serial. It’s probably not as good as Feuillade’s best, but it’s good fun and beautifully photographed (see top of section) and acted–and long enough to require a meal break. Fans of the great Ivan Mosjoukine (as he spelled his name after emigrating from Russia to France) will especially want to see this one. Available from Flicker Alley

Berlin Alexanderplatz (Rainer Werner Fassbender, 1980) 13 episodes and an epilogue. 15 hours, 31 minutes. Back when it first came out, this was treated more as a film than a TV series. It showed in 16mm at arthouses and archives. David and I drove to Chicago to see the whole thing in batches over a single weekend at The Film Center (now the Gene Siskel Film Center). It’s available on either DVD or Blu-ray as a Criterion Collection set (#411 for you Criterion number-lovers). It’s also streaming on the Channel. Both have a batch of supplements, even the 1931 German film of the novel, so you can stretch the experience out even longer.

Silent serials may work for some families, if the kids have been introduced to silents already through the more obvious route of films with Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and the other great comics of the era. If not, families can fill their time with more recent films in episodes with continuing stories.

The serial format has had a comeback in recent decades, partly due to the influence of the first Star Wars trilogy and partly to the need for ever expanding amounts of moving-image content in the era of home-video, cable, and internet services. For those who want to binge Star Wars, you don’t need my guidance. Anyway, I gave up after the first of the recent series, the one where Adam Driver took over as the villain. (Not that I have anything against Adam Driver. It was the film.) Even daily life in a pandemic is too short for more.

The Harry Potter series. (2001-2011) Eight episodes, 990 minutes, or 16.5 hours. This series is not high art, but it’s pretty good, highly entertaining (to some, at least), and even has one episode, number three, directed by Alfonso Cuarón, HP and the Prisoner of Askaban (above). The others are HP and the Sorcerer’s Stone (or Philosopher’s Stone in the UK and elsewhere; Chris Columbus), HP and the Chamber of Secrets (Chris Columbus), HP and the Goblet of Fire (Mike Newell), HP and the Order of the Phoenix, HP and the Half-Blood Prince, HP and the Deathly Hallows: Part I, and HP and the Deathly Hallows: Part II (the last four, David Yates). These films are, of course, available in multiple versions, on disc and streaming. As far as I can tell, none of the complete boxed sets have the two last parts in 3D; those have to be purchased separately. Having seen the last film in a theater in 3D, I can say that it doesn’t seem to be one of those films that is much improved if one sees it that way (unlike Mad Max: Fury Road, in the section below).

The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings extended editions: An Unexpected Journey (2012), The Desolation of Smaug (2013), The Battle of the Five Armies (2014), The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), The Two Towers (2002), and The Return of the King (2003, above). 6 episodes, 1218 minutes, or 20 hours, 18 min. Yes, for sheer length this serial tops them all. Plus there are lots of supplements. Each part of the Hobbit films has one commentary track and a bunch of making-ofs, adding up to 40 hours, 5 1/2 minutes. This pales, however, in comparison with the LOTR extended editions, which have four commentary tracks, totaling 45 hours, 44 minutes. The making-ofs are hard to get exact figures for, but I estimate about 22 hours for all three films. That’s about 68 hours of audio and visual supplements.

To top that off, the Blu-ray set contains the three feature-length documentaries by Costa Botes: The Fellowship of the Rings: Behind the Scenes, The Two Towers: Behind the Scenes, and The Return of the King: Behind the Scenes, all adding another 5 hours, 2 1/2 minutes. (Botes’s films were also included in a “Limited Edition” reissue of the theatrical versions of the LOTR films in 2006.) In toto, if one watches every single item and listens to all the commentaries, one could escape 133 hours and 10 minutes of isolation boredom–and possibly go mad in the process. But treating the bingeing as an eight-hour-a-day job, it would come to 16 1/2 days.

All this does not include the supplements accompanying the theatrical-version discs. These are charming but more oriented toward introducing complete neophytes to the universe of Middle-earth than toward giving filmmaking information.

Series

Series, as opposed to serials, usually involve continuing characters but self-contained stories. Most of the series below could be watched out of order without suffering much. It would help to watch Mad Max first, since it’s an origin story. The Apu Trilogy should be watched in order because it’s about the central character’s stages of life. Each of the M. Hulot films bears the traces of the contemporary culture in which it is set, but one can understand each fine out of order. I saw Traffic first, in first run, and then saw the others.

Mad Max (1979), Mad Max 2, aka The Road Warrior (1981), Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985), and Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) add up to 411 minutes, or 6 hours and 51 minutes. You know them, you love them–but have you ever watched them straight through? We’ve written about Fury Road (here and here). That’s a film where the 3D really does play an active role.

Jacques Tati’s Monsieur Hulot films: Mr. Hulot’s Holiday (1953), Mon Oncle (1958, see top), Play Time (1967), and Traffic (1971). They add up to 7 hours and 4 minutes. Or add his non-Hulot films, Jour de fête (1949) and Parade (1974) for just under an additional 3 hours of hilarity. You can buy all of Tati’s films at The Criterion Collection or stream them at The Criterion Channel. Throw in my “Observations on Film Art” segment on Parade for an extra 12 minutes. And check out Malcolm Turvey’s new book, Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comedic Modernism, soon to be discussed in a portmanteau books blog here.

Dr. Mabuse films plus Spione: Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (1922), Spione (1928, frame above), The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933) and The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960), adding up to 610 minutes, or 6 hours and 10 minutes. Few if any directors have extended a series over such a stretch of time, and the Mabuse films are quite different from each other (including having different actors play the master criminal). I throw Spione into the mix because the premise and tone are so similar to the first Mabuse film. Haghi is basically Mabuse as a master spy instead of a gambler and general creator of chaos; given that he’s played by Rudolf Klein-Rogge, who was the first Mabuse, the comparison is almost inevitable. One can almost imagine Haghi as just another of Mabuse’s disguises and it fits right into the series. I’ve linked the streaming sources to the titles above.

Kino Lorber has the restored version of Der Spieler on DVD and Blu-ray, Eureka has the restored version of Spione on DVD and Blu-ray (note: Region 2 coding) The Criterion Collection offers a DVD of Testament, and Sinister Cinema has a DVD of The 1,000 Eyes. (For those who want to dig deeper, there a Blu-ray set of all of Lang’s silents, from Kino Classics and based on the F. W. Murnau Stiftung restorations. That totals 1894 minutes, or about 31 and a half hours. I don’t know if that counts the supplements, but there are lots of them.)

Apu Trilogy: Pather Panchali (“Song of the Little Road,” but nobody calls it that, 1955), Aparajito (1956), and The World of Apu (1959). 341 minutes. Satyajit Ray’s trilogy may seem like a serial, in that it follows the life of the main character, Apu. Yet Ray had not planned a sequel until Pather Panchali achieved international success, and the films have big time gaps in between, with no dangling causes. These are three of the most beautiful, touching films ever made, and the stunning restoration from a damaged negative and other materials is little short of a miracle. If you have never seen these or saw them before the restoration, do yourself a favor and binge them. Have some tissues handy, and I don’t mean for stifling coughs and sneezes. Available on disc from The Criterion Collection and streaming on The Criterion Collection here, here, and here.

Now I briefly cede the keyboard to David for his recommendations of Hong Kong series.

Triads vs. cops, Triads vs. Triads

Infernal Affairs (2003).

There are many delightful Hong Kong series. I enjoy the silly Aces Go Places franchise (1982-1989) and the pulse-pounding Once Upon a Time in China saga (1991-1997). Alas, almost none of these installments entries are represented on streaming. I could find only the weakest OUATIC title, Once Upon a Time in China and America (1997) on Amazon Prime, Vudu, and iTunes.

If you want to go for samples, there are two diversions from the ever-lively Fong Sai-yuk series. The Legend (US title of the first entry, a bit pricy from Prime). The more reasonably priced Legend II, the US version of the second entry, has a fantastically funny martial-arts climax featuring Josephine Siao Fong-fong as Jet Li’s mom. This is available from several streamers. Older kids won’t find either one too rough, I think.

There are two outstanding series more suitable for adult bingeing. Infernal Affairs (2003-2004) was made famous by Scorsese’s remake The Departed (2006), but the original is better, and the follow-ups are loopier. The first entry offers solid, suspenseful plotting and meticulous performances by top HK stars Tony Leung Chui-wai and Andy Lau Tak-wah, supported by a rogues’ gallery of unforgettable character actors. Parts two and three spin off variations on the first one, tracing out before-and-after incidents and throwing in some quite strange narrative contortions. The whole thing provides an engrossing five and a half hours of entertainment. Available from several services.

In my book Planet Hong Kong I analyze the trilogy as an example of how directors Andrew Lau and Alan Mak Siu-fai created a more subdued thriller than is usual in their tradition. Bonus material: In the spirit of providing free stuff during the crisis, here in downloadable pdf form is my little chapter on the trilogy: Infernal Affairs interlude.

Also subdued, even subtle, is Johnnie To Kei-fung’s Election (2005) and Election 2 (aka Triad Election, 2006). These films dared to show secret gang rituals that other filmmakers shied away from. The first part plays out ruthless competition among rival Triad leaders, including strikingly unusual methods of punishing one’s adversary. The second entry, even more audacious, suggests that Hong Kong Triad power is intimately tied up with mainland Chinese gangs, backed up by political authority.

Johnnie To’s pictorialism, so feverish in The Longest Nite (1998), A Hero Never Dies (1998), The Mission (1999), and other films, gets a nice workout here as well. Infernal Affairs is agreeably moody, but the Election films are black, black noir.

The pair add up to three hours and a quarter. The first film is apparently available only on disc but the second is streaming from several sources.

Of course, to get into the real Hong Kong at-home experience, some viewers will find all these films easily and cost-free on the Darknet.

Thematic combos

Flicker Alley’s Albatros films. 5 films, 664 minutes, or 11 hours and 4 minutes. I wrote about the DVD set, “French Masterworks: Russian Émigrés in Paris 1923-1929” when it first came out. It’s still available here. The Albatros company made some of the key films of the 1920s, most of which are still too little known, including Ivan Mosjoukine’s Le brasier ardent (1923, above). If this is still a gap in your viewing of French films, here’s a chance to fill it.

Yasujiro Ozu: The Criterion Collection has released a helpful thematic grouping of some of Ozu’s early films. One is “The Silent Ozu: Three Family Comedies” (DVD and streaming), including I Was Born, but …, Tokyo Chorus, and Passing Fancy, adding up to 281 minutes. The British Film Institute has gone further along the same lines, releasing “The Gangster Films,” also three silents: Walk Cheerfully (1930), That Night’s Wife (1930), and the wonderful Dragnet Girl (1933); they add up to 259 minutes. The BFI has also put out “The Student Films,” (listed as out of stock at the moment) yet more silents: Ozu’s earliest complete surviving film, Days of Youth (1929), I Flunked, But … (1930), The Lady and the Beard (1931) , and Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth? (1932), adding up to 251 minutes.

David has recorded an entry on Ozu’s Passing Fancy for our sister series, “Observations on Film Art,” on the Criterion Channel; it should go online there sometime this year.

Or watch all the “season” films in a row: Late Spring (1949), Early Summer (1951), Early Spring ((1956), Equinox Flower (1958), Late Autumn (1960), End of Summer (1961), and An Autumn Afternoon (1962), for a grand total of 840, or 14 hours. Including An Autumn Afternoon is cheating a bit, since the original title means “The Taste of Mackerel.” Still, it’s so much like the earlier films in equating a season with a stage of life that the English title seems perfect. The early films equate the seasons with the young people, about to marry or recently married, while in the later films, and especially the last three, the seasons refer to the older generation, lending an elegiac tone to the end of Ozu’s career. David has done commentary for the DVD of An Autumn Afternoon.

All of these (except for Days of Youth) and many other Ozu films can be streamed on The Criterion Channel, which also has a bunch of supplements on this master director.

Or just watch The Criterion Channel’s Kurosawa films in chronological order, or Bresson’s or Godard’s or Bergman’s or …

Or watch all of Hideo Miyazaki’s films in chronological order, with or without the company of kids.

Just really long films

War and Peace (Sergei Bondarchuk, 1965-1967, above) 4 parts: 7 hours, 3 minutes, 44 seconds. I suppose this is technically a serial, since the parts were released over three years. Still, the idea presumably was that it ultimately should be seen as one film, and the running time would permit it being seen in one day fairly easily. I have not seen this restored version, only the considerably cut-down American release back when it first came out. I remember it as being quite conventional, but on a huge scale in terms of design, cinematography, and crowds of extras. Seeing it in its original version would no doubt be impressive (see above). Available on disc at The Criterion Collection and streaming on The Criterion Channel. The supplements total 175 minutes and four seconds, pushing the total up to nearly 10 hours.

Satan’s Tango (Béla Tarr, 1994) 450 minutes, or 7 hours 30 minutes. Film at Lincoln Center has just made Tarr’s epic available for streaming; you can rent it for 72 hours and support a fine institution. As to owning it, the DVDs seem to be out of print. There is, however, a Blu-ray coming from Curzon Artificial Eye on April 27 in the UK. Pre-order it here. Obviously many of us will still be stuck inside by the time it arrives. Or if you have it on the shelf and never quite got around to watching it, here’s your chance. Derek Elley’s Variety review sums up its pleasures. Our local Cinematheque has shown it twice, once in 35mm and more recently on DCP (see here, with the news buried at the bottom of the story). David reported on that first showing, and later he wrote a general entry about Tarr’s work on the occasion of having met the man himself.

Shoah (Claude Lanzmann, 1985) 550 minutes, or 9 hours and 10 minutes. The Holocaust examined through modern interviews with a broad range of people involved. Available in a restored version on disc from The Criterion Collection. It does not seem to be available currently for streaming.

Unclassifiable

Then there’s Dau (2020-), a biopic of a Soviet scientist that is perhaps the most ambitious filmmaking venture ever.

Shot on 35mm over three years in a real working town with 400 characters played by actors who remained in character and costume round the clock the whole time. Few have seen these, though two showed at the Berlin festival this year. We haven’t seen them but plan to give it a go, since they have just shown up online. Here’s a helpful summary of the project. At the Dau Cinema website, you can stream the first two films for $3 each: Dau. Natasha (2:17:53) and Dau. Degeneration, (6:09:06) adding up to 8 hours and 27 minutes. Twelve more films are announced for future release, with no timings given. Clearly not suitable for family viewing.

I have not attempted to add up all these timings, but if you can track most of them down, they might get you through much of the isolation period. Stay safe!

Election (2005).

What’s left to discover today? Plenty.

Der Tunnel (William Wauer, 1915).

DB here:

Being a cinephile is partly about making discoveries. True, one person’s discovery is another’s war horse. But nobody has seen everything, so you can always hope to find something fresh. There’s also the inviting prospect of introducing a little-known film to a wider community–students in a course, an audience at a festival, readers of a blog.

A festival like Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato (we covered this year’s edition here and here and here) offers what you might call curated discoveries. Expert programmers dig out treasures they want to give wider exposure. Such festivals are both efficient–you’re likely to find many new things in a short span–and contagiously exciting, because other movie lovers are alongside you to talk about what you’re seeing.

A year-round regimen of curated discoveries is a large part of the mission of the world’s cinematheques. This is why places like MoMA, LACMA, MoMI, BAM, TIFF, ICA, and other acronymically identified showcases are precious shrines to serious moviegoing.

But other discoveries are made in a more solitary way. Film researchers, for instance, ask questions, and some of those can really only be answered by visiting film archives. Sometimes we need to look at fairly obscure movies. And despite the rise of home video, there are plenty of obscure movies that can be seen only in archives. It’s here that the programmers of Ritrovato and Pordenone’s Giornate del Cinema Muto come to select their featured programs.

Archive discoveries aren’t predictable, and many are likely to be of interest only to specialists. Such was the case, mostly, with our archive visits this summer. But as in years past (tagged here), all our archive adventures yielded pure happiness.

This time I concentrated on films from the 1910s-early 1920s films because I hope to make more video lectures about this, the most crucial phase of film history. (One lecture is already here.) In our archive-hopping, we saw films I was completely unfamiliar with. I re-watched some films I’d seen before and found new things in them. I detected some things of interest in films I hadn’t known. Most exciting was our viewing of a major film that has gone unnoticed in standard film histories.

In the steps of Jakobson and Mukarovský

Love Is Torment ( Vladimír Slavínský, Přemysl Pražský, 1920); production still.

First stop was Prague, where I was invited to give two talks. At the NFA we saw two films on a flatbed: a portion of Feuillade’s Le Fils du Filibustier (1922) and a cut-down version of Volkoff’s La Maison du mystere (1922), the latter a big gap in our viewing. The expurgated Maison came off as rather drab, lacking nearly all the big moments much discussed in reports like James Quandt’s from a decade ago. So we search on for the full version. . . .

As for the Feuillade: Le Fils du Filibustier was his last “ciné-roman.” Our two-reel segment, which seemed fairly complete, confirmed his late-life switch to fairly fast, Hollywood-style editing, with surprisingly varied angles.Again, though, we yearn to see the entirety of this pirate saga.

On another day the archive kindly screened several 1910s-early 1920s Czech films for us. Our hosts Lucie Česálková and Radomir Kokes translated the titles and provided contexts. Among the choices were Devil Girl (Certisko, 1918), with a protagonist who’s more of a tomboy than a possessed soul; and the full-bore melodrama Love Is Torment (Láska je utrpením, 1919). The plot, outlined here, involves scaling and jumping off a tower, twice. Once it’s a stunt for a film within the film, the second time (below) it’s the real thing.

Radomir explained to us that one of the co-directors, Vladimír Slavínský, seemed in his 1920s films to specialize in building two reels (often the third and fourth) in a “classical” fashion before letting the other three become more episodic. And indeed, most of the late 1910s-early 1920s films we saw were up to speed with other European filmmaking, in their staging, cutting, and use of intertitles.

We look forward to viewing more Czech films as the opportunity arises. A culture that gave us Prague Structuralism is definitely worth getting to know better. In the meantime, the journal Illuminace, edited by Lucie, is injecting a great deal of energy into local film studies, and the archive is entering a fresh phase with its new director, Michal Bregant.

3D excavations

Der Hund von Baskerville (1914).

In Munich, we reconnected with our old friends Andreas Rost, now retired from administering the city’s cultural affairs, and Stefan Drössler, director of the Munich Filmmuseum. We also reunited with the stalwart archivists Klaus Volkmer, Gerhard Ullmann, and Christoph Michel. Talking with them, we realized we hadn’t been back for over ten years. Klaus and Gerhard were warm and helpful during our earlier visits.

One rainy afternoon, Stefan shared his research on the history of 3D. He presented a spectacular PowerPoint, with rare images and some truly startling revelations. He has given this talk at intervals over the years, but it grows and deepens as he discovers more. Accompanying it, he screened some Soviet 3D films, including the 1946 Robinzon Cruzo. This mind-bending item was made with diptych images, so that the projected image turned out to be slightly vertical. The soundtrack runs down the middle.

The director, Aleksandr Andriyevsky, made excellent use of 3D to evoke the stringy vines and protruding leaves of Crusoe’s island. Amid all the talk today about glasses-free 3D, it’s interesting to learn that Soviet researchers prepared such a system. Stefan’s archaeology of 3D, for me at least, was a pretty big discovery.

At Munich we also saw three silent German titles. Two were associated that resourceful self-promoter Richard Oswald. Sein eigner Morder was a 1914 version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr Hyde, directed by Max Mack from Oswald’s screenplay. Shot in big sets, it spared time for the occasional huge close-up. The other film was Oswald’s semi-comic adaptation of The Hound of the Baskervilles (Der Hund von Baskerville, dir. Rudolf Meinert, 1914), which he had already turned into a play. The sleuth isn’t exactly our idea of Holmes (see above), and he isn’t as quick-witted, I thought, but it was an enjoyable item. Dr. Watson has a sort of tablet which picks up messages; Holmes’ orders are spelled out in lights on a grid. Stefan rightly called it a 1914 laptop.

As for the third film: More about that coming up.

The shadow of Hollywood

Les Deux gamines (1921).

At Brussels, thanks to the cooperation of the Cinematek, I was able to see several items for the first time, and two held considerable interest. The short The Meeting (1917), by John Robertson, showed a real flexibility in laying out the space of a cabin both in front of the camera and behind it. Most interior scenes in 1900-1915 cinema bring characters in from a doorway in the rear of the set (as Feuillade does in his 1910s films) or straight in from the sides, perpendicular to the camera (as Griffith tends to do). The Meeting shows that the diagonal screen exits and entrances that we see in exteriors were coming into use in interior sets as well.

Another 1917 film, Frank Lloyd’s A Tale of Two Cities, was further support for the idea that American continuity filmmaking was well-established and already being refined at the period. Dickens’ classic tale is handled with dispatch–rapid exposition, smooth crosscutting to set up the plot lines–and the film makes dynamic use of crowds surging through well-composed, starkly lit frames. There are also some remarkably expressive close-ups, evidently made with wide-angle lenses.

To clinch a plot point, the resemblance of aristocrat Charles Darnay to British solicitor Sydney Carton, the star William Farnum plays both characters. Not much of a problem if you keep the characters in separate shots; the good old Kuleshov effect (aka known as constructive editing) makes it easy. At this period, though, filmmakers were perfecting ways to show one actor in two roles within a single shot. The most famous examples involve Paul Wegener in The Student of Prague (1913) and Mary Pickford in Stella Maris (1918).

Cinematographer George Schneiderman contrives some really convincing multiple-exposures showing Farnum as both Darnay and Carton. There are some standard trick compositions putting Farnum on each side of the screen, but several images take the next step and let the actor cross the invisible line separating the two halves. At another point, we get a flashy passage showing the two facing one another in court, followed by a “Wellesian” angle of the two characters’ heads in the same frame.

Hollywood’s pride in photorealistic special effects, so overwhelmingly apparent today, has deep roots.

Part of my Brussels visit involved checking and fleshing out notes on certain films I saw many years ago. Some were wonderful William S. Hart movies like Keno Bates, Liar (1915; surely one of the best film titles ever). There was, inevitably, Feuillade as well. The influence of Hollywood was powerful in the ciné-roman Les Deux gamines (1921). This baby, released in 12 parts originally, runs nearly 27,000 feet. At 20 frames per second, it would take six hours to screen. What with changing reels, making notes, counting shots, pausing to study things, and taking stills, Kristin and I took about ten hours to watch it.

Was it worth it? An adaptation of a popular stage melodrama, it can’t count as one of Feuillade’s major achievements. Two girls are left alone when their mother is reported dead. They are adopted by their gloomy grandpa and tormented by his overbearing housekeeper. They become the target of kidnapping by gangster pals of their father, who has divorced their mother and turned to a life of petty crime. Their allies are their young cousins, a wealthy benefactor, and their godfather and music-hall star Chambertin. Everything ends happily, if you count the father’s redemptive sacrifice on behalf of a pregnant woman.

Les Deux Gamines is determined to delay its ending by any means necessary. Form here definitely follows format; Feuillade fills out the serial structure with plots big and small. (Shklovsky would love it.) There are incessant abductions, escapes, rescues, coincidental meetings, and timely reformations, plus at least three cases of people wrongly assumed to be dead. All of this is accompanied by an endless exchange of telegrams and letters. People are forever piling into and out of carriages, train cars, and taxis. Such material serves as makeweight for some genuinely big moments, including a cliff-hanging scene and a stunning climax in a smuggler’s warehouse stuffed with gigantic bales of used clothing.

Like Le Fils du Filibustier, this film shows Feuillade trying to change with the times. The supple long-take staging of Fantômas and Les Vampires and Tih-Minh mostly goes away, to be replaced by rapid editing. Feuillade employs standard continuity devices, as when the grandfather discovers that the kids have sneaked out at night and are trying to return by scaling the gate.

Feuillade varies his angles and lighting to accentuate the moment of visual discovery. Elsewhere, some appeals to “offscreen sound” (cutaways to doorbells and telephones) built up to a surprise effect.

But by the energetic standards of, say, Robertson or Lloyd several years earlier, Les Deux gamines is fairly timid. Feuillade doesn’t explore editing resources very much here, not even as much as in Le Fils du Filibustier. The fairly quick cutting pace stems partly from the stratagem of having dialogue titles interrupt static two-shots of characters talking to one another. This sort of proto-talkie-technique yields efficient storytelling but not much visual momentum. Feuillade tried flashier things in other films of the period (see here).

Hours and hours of nothing but Bauers

The Alarm (1917).

Yevgeni Bauer, one of the master directors of the 1910s, remains lamentably unknown. About two dozen of his over seventy films survive, but many of the ones we have lack intertitles. A few of his films are available on DVD (most obviously here; less obviously here). He died of penumonia in 1917, between the February revolution and the Soviets’ coup d’état in October. He was only 52.

My first archive-report entry back in 2007 recorded my interest in Bauer, and I’ve returned to his films over the years. Now here I was watching some again, confirming things I found of interest then, and discovering (that word again) new felicities. I hope to say more in those short video lectures on the 1910s, but I can’t leave without giving you a taste of his qualities.

Two of the films I saw this time were from 1917. The Alarm (Nabat) came out in May 1917, just before Bauer’s death in June. Originally running eight reels, it was cut down after the initial release, and that’s evidently the version we have. For Luck (Za Schast’em, September 1917) was directed by Bauer from his sickbed. Both films are fairly hard to follow. The Alarm lacks intertitles, and For Luck has many fewer than it had originally.

The two films are of exceptional interest, though. For one thing, there’s the involvement of Lev Kuleshow, who at the age of eighteen served as art director for the earlier film and, apparently reluctantly, as an actor in the later one. More important, the films remain as beautifully designed, staged, and acted as ever.

The Alarm is a wide-ranging drama set before the February upheaval. The drama involves romantic intrigues among the upper class, interwoven with a workers’ rebellion against a master capitalist. The millionaire Zeleznov holds court in a vast office with chairs bearing ominous spires and spiky arches; the windows open onto a view of his factory. A long-shot view is above; here’s a sample of how Bauer shows off his decor in something akin to shot/ reverse-shot.

The idea of capitalism as an overreaching religious striving is evoked by turning Zeleznov’s headquarters into a Symbolist cathedral. And looking at the second shot, you wonder whether Kuleshov’s inclination to stage his own scenes against pure black backgrounds has its source in his work for the man he called “my favorite director and teacher.”

As ever, Bauer makes fluid use of depth. He choreographs meetings of Zeleznov’s brain trust in ever-changing arrangements, and he eases a man out of a boudoir through a mirror reflection over a woman’s fur-draped shoulder.

Compared to the scale of The Alarm, For Luck is decidedly low-key–a bourgeois melodrama that extends barely beyond an anecdote. Zoya has been a widow for ten years, and she hopes to marry the loyal family friend Dmitri. But Zoya’s daughter Lee hasn’t yet reconciled to losing her father. The couple hope that Lee has worked out her grief during her dalliance with a young painter (played by Kuleshov), but she reveals that all along she has hoped to marry Dmitri.

The Alarm used some extravagant sets, both for interior and exterior scenes, but a good deal of For Luck takes place in parks and terraces. The sincere Enrico sketches Lee in front of swans, and they steal some moments in a bower.

Still, there are some interiors boasting Bauer’s famous pillars and columns, which create massive, encapsulated spaces. Here Zoya looks off, in depth, at the ailing Lee, in bed on the far right.

Sharp-eyed Bauerians will notice the mirror set into the left wall, reflecting Zoya. Kuleshov, who did art direction on this as well as The Alarm, worried more about the trumpet-blowing Cupid floating between the pillars on the left. (“It turned out bad on the screen–incomprehensible and inexpressive.”) He did think that the tonalities of the set worked well: “As an experiment, I put up a set painted in shades of white that were ever so slightly different from one another.”

“Ever so slightly different” isn’t a bad evocation of the tiny variations of shape and shade, light and texture, that characterize Bauer’s ripe, sometimes overripe, imagery. This is a social class on the way out, but it leaves behind a great glow.

Tunnel: Vision

The Tunnel (1915).

In 1913, the popular novelist Bernhard Kellermann published Der Tunnel. It’s not quite science-fiction, more a prophetic fiction or realist fantasy in the vein of Things to Come. The book became a best-seller and the basis of a 1915 film directed by William Wauer.

The plot would gladden the heart of Ayn Rand. A visionary engineer persuades investors to fund building an undersea railway connecting France to the United States (specifically, New Jersey). No meddling government gets in the way of this titanic effort of will. Max Allan buys land for the stations, hires diggers from around the world, and risks everything he has. The obstacles are many. An explosion scares off workers; there is a strike; impatient stockholders raid and burn the company headquarters.

Max Allan moves forward undeterred, though he hesitates when his wife and child are stoned to death by a mob. After twenty-six years, the railway is opened. Max, along with his new wife (the daughter of his chief backer), proves it’s safe by taking the first transatlantic train. The event is covered by television, projected on big screens around the world (above). In the original novel, a film company was commissioned to document every stage of work.

The book skimps on characterization, and the film is even less concerned with psychology. Once the character relations are sketched, Wauer goes for shock and awe. The Tunnel‘s thrilling crowd scenes of work, fire, devastation, riots, and panic look completely modern. Bird’s-eye views of stock-market frenzy anticipate Pudovkin’s End of St. Petersburg, and Wauer creates an Eisensteinian percussion of light and rushing movement as workers flee the tunnel collapse.

For the sequences showing the tunnel construction, Wauer supplies violent alternations of bright and dark as men, stripped and sweaty, attack the rock face. The variety of camera positions and illumination is really impressive.

Comparisons with The Big Film of 1915 are inevitable. The intimate scenes of The Tunnel are far less delicately realized than the romance and family life of The Birth of a Nation, and the battle scenes in Birth have a greater scope than what Wauer summons up. But Wauer’s handling of crowds is more vigorous than Griffith’s riots at the climax of Birth, and his pictorial sense is in some ways more refined, even “modern.” There’s little in Birth as daringly composed as the static long shot surmounting today’s entry.

Wauer can handle small-scale action very crisply. The opening scene in an opera house creates low-angled depth compositions more arresting than Griffith’s depiction of Ford’s Theatre. Max’s wife, in one box, is watching his efforts to attract funding from the millionaire Lloyd. Wauer constantly varies his camera setups to highlight Max’s wife in the background studying Lloyd’s daughter, sensing in her a rival for her husband. Whether the angle is high or low, the wife’s presence in her distant box is signaled at the top of the frame.

The second and third shots above present similar but not identical setups, adjusted to reset the depth composition.

It was at Munich’s Filmmuseum a decade ago that I first encountered the brooding power of Robert Reinert’s Opium (1919) and Nerven (1919), the latter now available on DVD. I was convinced that Nerven was as important, and in some ways more innovative, than the venerated Caligari. Now the conviction grows on me that in The Tunnel we have another galvanizing, outlandish masterwork of the 1910s. I hope it will somehow get circulated so that wider audiences can discover it. Yeah, that’s the word I want: discover.

Without archivists, no archives. We’re grateful to Michal Bregant, head of the Czech Republic’s archive, for access to films and for his companionship during our visit. Thanks as well to Lucie Česálková, our host; her knowledgable colleague Radomir Kokes (who kindly corrected the initial version of this post); Petra Dominkova, our Czech translator; and Vaclav Kofron, editor of the Czech versions of our books. Lucie supplied the frame enlargement from Love Is Torment. As well: Good luck to the Kino Světozor!

In Munich, we owe a huge debt to archive chief Stefan Drössler, for his generous sharing of information and his and Klaus Volkmer’s rehabilitation of The Tunnel. Stefan also provided the images from Robinson Crusoe and The Hound of the Baskervilles. Coming up is his work for the annual Bonn International Silent Film Festival, 7-17 August. Thanks as well to Gerhard Ullmann and Christoph Michel.

In Brussels, as ever, the Cinematek has made us welcome, and we thank archive director and long-time friend Nicola Mazzanti and vault supervisor Francis Malfliet. Over the last thirty years, a great deal of our research has depended upon the cooperation the Cinematek leadership: Jacques Ledoux, Gabrielle Claes, and now Nicola.

My quotations from Kuleshov come from Silent Witnesses: Early Russian Films, 1908-1919, ed. Yuri Tsivian and Paolo Cherchi Usai (Pordenone: Giornate del Cinema Muto, 1990), 388-390.

There’s a chapter on Feuillade in my Figures Traced in Light, where Bauer is discussed as well. My essay on Robert Reinert is in Poetics of Cinema.

Thanks to Antti Alanen for correction of a misspelled title. Speaking of discoveries, you’ll find plenty on his wonderful Film Diary site. During his recent trip to Paris, he’s writing about art exhibitions, Dominique Paini’s Langlois exposition at the Cinémathèque, and Godard’s Adieu au langage.

Screening at the Czech Republic’s National Film Archive. From left: Michal Večeřa, Tomáš Lebeda, Radomir Kokes, Lucie Česálková, and Kristin.

Talks, pictures, and more

Hard though it is to believe, our dear friend and colleague Janet Staiger is retiring this year from her post as the William P. Hobby Centennial Professor of Communication at the University of Texas. About a year and a half ago, Janet joined us in writing an essay celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of the publication of our collaborative volume, The Classical Hollywood Cinema. Several of our other books have gone out of print, but that one remains available. We’re convinced that its success rests on the fact that the three of us were able to contribute different areas of expertise that meshed seamlessly to cover what turned out to be a far more ambitious topic than we initially envisioned.

We’re delighted to help celebrate Janet’s retirement, since the Department of Radio-Television-Film has invited both of us to lecture at an event to pay tribute to Janet. We’d love to see any of you in the Austin area on March 19. We chose our topics without planning it that way, but they end up book-ending the classical era. David will be speaking on the 1910s, when the early cinema was coalescing into the art of “the movies,” and Kristin deals with the question of how one can deal with a contemporary event that has not yet run its course. (KT)

Short film

The American release of Jafar Panahi’s This Is Not a Film, as well as the first Best Foreign Film Oscar for an Iranian film, A Separation (Asgar Farhadi), have kindled a new interest in Iranian cinema just as some of its most prominent practitioners are dealing with exile, house arrest, and censorship. The International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran has recently posted a short film, Iranian Cinema Under Siege, which lays out the issues succinctly.

Earlier many cinephile sites, including ours, called attention to Panahi’s plight. Anthony Kaufman updates us on his still-undetermined fate. (KT)

Lotsa pictures, lotsa fun (cont’d)

Lynda Barry, Ivan Brunetti, and Chris Ware share a mic.

Our Arts Institute has brought Lynda Barry to campus as an artist in residence this spring, and it’s been a breath of fresh air—actually, make that “blast.” Kristin and I have loved Barry’s work since the 1970s, but only recently did we learn that she was born in Wisconsin and still lives here.

Barry’s UW webpage is a captivating foray into Barryland, and her course, “What It Is: Manually Shifting the Image,” has been open to anyone interested in exploring drawing and/or writing. Convinced that art is a biological phenomenon (“Anybody can make comics,” she says), she encourages people to expand their creative powers without fear of being considered unskillful.

As part of her visit, Professor Lynda has also scheduled events to introduce people to writers and artists. She hosted Ryan Knighton (“badass blind guy”), gave a talk

As part of her visit, Professor Lynda has also scheduled events to introduce people to writers and artists. She hosted Ryan Knighton (“badass blind guy”), gave a talk on with guest Matt Groening, and will interview Dan Chaon (3 May). Her first pair of invitees, on 15 February, was Chris Ware and Ivan Brunetti.

You know I was there.

In fact, I came ninety minutes early to get my front row seat, alongside comics guru Jim Danky. Good thing too; by the time the session started, the big lecture hall was packed.

The first part of the session was a brief panel discussion among Barry, Brunetti, and Ware. As if by design, the table mike didn’t work, so Barry’s lavaliere, threaded up through her pants and blouse, had to be yanked out and stretched across the table when her guests wanted to talk. Result shown above.

Barry called Brunetti a master of balancing the verbal and the visual aspects of comics, and she introduced Ware as “the Wright Brothers” of the graphic novel, with Lint as his Kitty Hawk. Then the two guests, who live in Chicago and get together for Mexican lunch once a week, talked about their influence on one another. Brunetti says that seeing Ware’s work in Raw made him rethink comics altogether. Ware finds in Brunetti “an honest critic.”

Then Ware left the stage to Brunetti, who took us through his career in PowerPoint. He traced the influence of comics like Nancy and Peanuts on his pretty but edgy big-head style, and he talked about the autobiographical impulse behind much of his work. (“I draw these things to make fun of myself.”) Like many comics artists, he’s fascinated by cinema—be sure to check his “Produced by Val Lewton” page—and some of his New Yorker ensemble panels have the fluid connections we find in network narratives.

In all, it was a lively session that reminded me, among other things, how comic-crazy our town is. Not to mention our state: don’t forget Paul Buhle’s Comics in Wisconsin. That book is filled with work by Crumb, the Sheltons, Spiegelman, etc. It’s as well a tribute to enterprising publisher Denis Kitchen and the now-departed Capital City comics distribution firm. (DB)

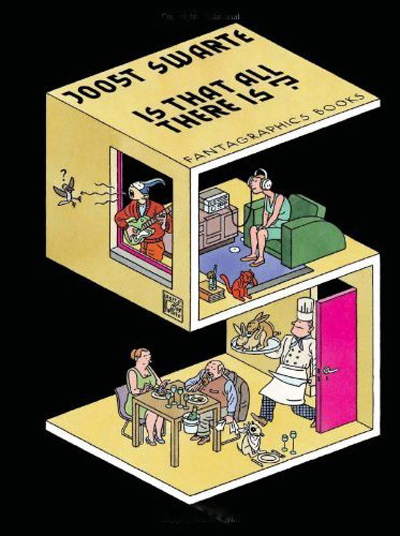

Le mot Joost

I got a little chance to talk to Ware, and we shared our admiration of Joost Swarte, one of the greats of cartooning. Readers of this blog may recall my shameless promotion of Swarte’s work (here and here and here); one of the big events of my fall was getting to meet him in a Brussels gallery. As chance would have it, a couple of days after Barry’s event, I got my copy of the new Swarte collection Is That All There Is?

The book is a fine introduction to work that has for too long been restricted to French and Dutch publications. You get to meet the infinitely knowledgable Dr. Anton Makassar, the lumpish Pierre van Genderen, and the hip but mysteriously ethnic Jopo de Pojo. You also get the first statement of Swarte’s idea of the “Atom Style” of postwar design, connected to the “clear line” school of cartoon art. The book, done up in gorgeous graphics, is graced by an introduction by none other than Chris Ware.

It’s sort of hard to write an introduction for a cartoonist you can’t completely read. . . . I’ve read plenty of his drawings, however. Studied, copied, and plagiarized them, actually; the precise visual democracy of his approach compelled me as a young cartoonist to consider the meaning of clear and readable or messy and expressive, and it was the former which won out.

Now that he mentions it, there is a line running from Ware’s obsessive schematics of narrative space (and time, as Barry says) straight back to the fluent precision of Swarte’s design. Both artists invite your eye to discover things at all level of scale and visibility, while leading you, in Hogarth’s phrase, “on a wanton kind of chase.” (DB)

Derange your day with Feuillade

Two patient, ambitious researchers have contributed to our knowledge of Louis Feuillade’s work, a central concern of DB’s writing and this blog (here and here, in particular). They also teach us intriguing things about cinematic space.

First, Roland-François Lack of University College, London hosts The Cine-Tourist, a site that traces the use of Paris locations in films. His devotion to Paris equals that of the city’s filmmakers, so he provides a thorough canvassing of areas seen in Les Vampires, Fantômas, and Judex. Beyond Feuillade, you can find the places featured in other movies, including L’Enfant de Paris and Le Samourai. Roland-François has even solved the riddle of what movie house Nana visits in Vivre sa vie.

Hector Rodriguez of the City University of Hong Kong has set up a site devoted to Gestus. It’s a program that tracks vectors of movement in a shot and generates abstract versions of them that can be compared with action in other sequences. Gestus can whiz through an entire film–in this case, Judex–and come up with an anatomy of its movement patterns. Hector sees the enterprise as sensitizing us to movement patterns that we don’t normally notice. It also provides a dazzling installation.

Gestus’ ability to generate a matrix of comparable frames recalls Aitor Gametxo’s Sunbeam exploration. But Aitor was interested in how Griffith maps adjacent three-dimensional spaces. Hector’s project focuses on two-dimensional patterning, specifically the deep kinship between different shots when rendered as abstract masses of movement. And while the Sunbeam experiment lays out how spectators mentally construct a locale, Hector is just as interested in friction. “The system invites, confuses, and sometimes frustrates the viewer’s cognitive-perceptual skills.”

That, of course, is part of what cinema is all about. Visit Roland-François’ and Hector’s sites and have a little derangement today. (DB)

If you’re unfamiliar with Chris Ware’s work, a good overview/interview can be found here. Swarte’s stupendously beautiful site is here.

PS 12 March: Because I’ve been immersed in other stuff, I didn’t realize that Matt Groening actually showed up for Barry’s session! And I missed it! Hence the strikeout correction above, initiated by Jim Danky. More on Groening’s visit here.

Echoic patterns of stooping in Judex, as revealed by Gestus.