Archive for the 'Directors: Godard' Category

Godard: The power of imperfection

Opening credits of Bande à part (1963).

DB here:

He was a sketchy fellow, to put it mildly. Childhood episodes of theft were followed by larceny as an adult, when he stole his grandfather’s Renoir and swiped cash from the Cahiers du cinéma till. Notorious for taking funding for projects that were never made, he once contracted for $500,000 to create a film on the Museum of Modern Art. He declined to visit the museum and instead shot the footage from stills at home. When The Old Place was finished, he agreed to introduce it in Manhattan. Hours before he was about to fly out (on the Concorde) he canceled, using anti-American cinephilia as his excuse: “I will return to New York when the films of Kiarostami are playing on Broadway.”

He liked to fight. Friends, romantic partners, performers, producers, government officials, and critics all felt his wrath. Jane Fonda was the target of Letter to Jane, a critique of a photograph of her meeting the North Vietnamese. The voice-over narration insisted it was not an attack on her as a person but as a “star.” Breaking with Truffaut led Godard not only to harangue his former pal (“liar”) and the films he made, but demand money so that he could make a film in response to Day for Night. Truffaut’s twenty-page reply called him “a piece of shit on a pedestal.” They never spoke again, and Godard’s remarks after Truffaut’s death praised him as a critic but omitted mention of his films.

Meeting Professor Pluggy

King Lear (1987).

I never had an abrasive encounter with Godard, but I always sensed that he was aloof at best. My first, very brief meeting was in spring of 1973 when he and Jean-Pierre Gorin visited the University of Iowa with Tout va bien (1972). Onstage, he was calm and earnest, while saying fairly provocative things. (Go here for a record of one session.) Asked what he thought of The Godfather, he replied: “The Godfather is shit. But there is a part of me that loves shit.” My eyewitness encounter took place in an elevator, when the host told Godard and Gorin that their schedule now had an empty hour. Godard said: “I am a prostitute. Why do you not use me?”

I had more prolonged exposure to him in 1981, when he visited a lecture series I was giving at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. He was touring with Sauve qui peut (la vie) (1980), and the series director Melinda Ward took the opportunity for us to do a career review onstage. I planned to juxtapose clips from his work with those by other directors, and called him at Rolle to review my choices. He listened politely and said they would be fine, adding: “No matter what you choose, it always works.”

The session turned out well, with Godard modest about his efforts compared to those of Preminger (“like Manet”) and others. The only time the audience seemed ruffled was when he said of Jerry Lewis and the clip from The Ladies’ Man: “He is Robert Rauschenberg” (seems reasonable). For a couple of days Kristin and I drove him to interviews around town, and he spent his time reading Variety, noting only that he was pleased that Gance’s Napoleon was doing good business. Attempts to engage him in conversation were fruitless. But once onstage he was alert and genial, all soft speaking and gentle smiles.

The big stir came the following night with the screening of Sauve qui peut. A considerable portion of the audience objected to the film’s sexual politics. The most fraught moment, as I recall it, went like this:

Woman in the audience: Why do you make films only about women prostitutes, not male ones?

JLG (after a pause): They are different things.

Woman: How can you claim to talk about a women prostitute’s life?

JLG: Well, every time I hire a prostitute I ask her about her experiences.

Audience: stunned silence.

My last encounter was the most embarrassing. Invited to a conference on his work at Liège in 1986, I had horrible jet lag. In the first evening, a Q & A with the master, I made the mistake of sitting, as usual, in the front row. The problem was I kept dropping off to sleep. Every time I blinked awake, Godard was staring impassively at me. I thought no one noticed, but afterward one of the conference speakers said: “He was looking at you sleeping all the time.” Jesus.

I consider myself lucky to have escaped the treatment others have reported. Maybe it made it easier for me to admire his work. Yet even that admiration is tempered by exasperation. Bypassing von Stroheim and Buñuel, he might be the most annoying great filmmaker of all.

I’m not referring just to his obsession with female nudity, or his pretentious wordplay, or his pseudo-profundity. His provocation goes all the way down to the very texture of the film. In form and style he embraced irregularity. He will create a scene that’s conventionally beautiful, only to spoil it with a harsh disjunction or a silly gag or a deflating commentary. He seems to want to coax us to enjoy imperfection. His deformations of story and style are the result of testing the limits of what cinema had done, and might do.

Early work: Puncturing the plot

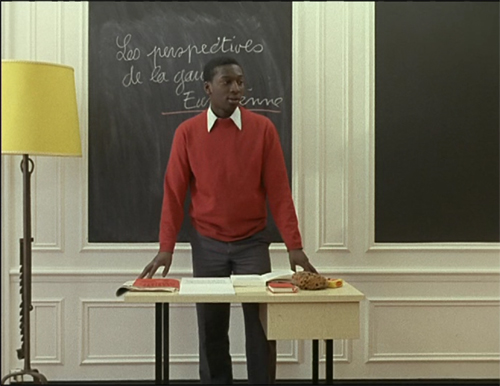

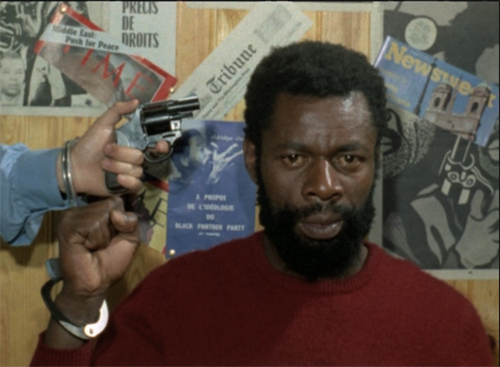

La Chinoise (1967).

Everything about him is troublesome. As a rough approximation, we tend to divide Godard’s career into three parts, but the results are peculiar. The early New Wave period runs from 1959 to 1967. The second, his overtly “agitprop” phase runs until 1980. Then we have “late Godard,” which dates from Sauve qui peut (la vie) until his death this year. What other artist has a “late” period running over forty years?

In all these periods, it’s common to say that Godard attacked, even destroyed, previous forms of cinema. But it helps to specify a bit more. I want to focus on his peculiar relation to narrative.

He often derided Hollywood’s reliance on stories, but throughout his career he depended on them. Asked about Hail Mary, he replied that the Bible had many good stories one could use. The project he proposed to Coppola about Bugsy Siegel and the founding of Las Vegas was initially titled simply “The Story.” Even the collage form he utilized in his last completed film, The Image Book, ends with a fictional tale about how Sheikh Ben Kadem, ruler of a kingdom called Dofa, tried to resist American imperialism.

One reason his early work succeeded, and survives as a body of classics, is that he relied on narrative conventions of traditional filmmaking. He rummaged through familiar genres: the couple on the run (Breathless, Pierrot le fou), spy intrigue (Le petit soldat), musical comedy (Une femme est une femme), social drama (Vivre sa vie, Two or Things I Know about Her), war picture (Les carabiniers), marital drama (Contempt, Une femme mariée), a robbery scheme (Band of Outsiders), a detective investigation (Alphaville, Made in U.S.A), and young romance (Masculin féminin).

More radically than his New Wave colleagues, Godard transforms these conventions. Sometimes he de-dramatizes intense situations, as in the violence of Le petit soldat and Les carabiniers. More commonly, he punctures the stories with digressions, skits, and uncertainties about character psychology. There’s also often a mockery of the very conventions invoked. Nonetheless the genres provide an armature for the audience to cling to, and the plots wrap up with more or less decisive endings.

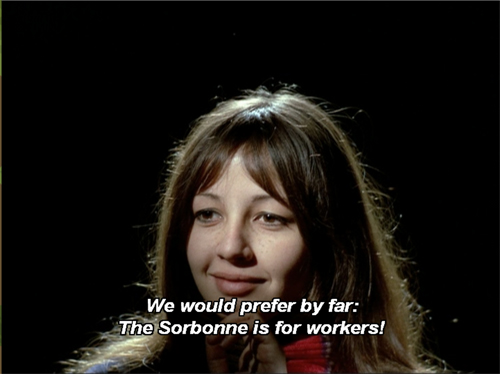

With La Chinoise, not only does the plot swerve from traditional genres (I suppose it’s a perverse roommate-relationships story) but the dynamic of the drama becomes overtly rhetorical, with both the characters and the overall narration setting out political theses. Weekend has a narrative core–a couple set out to visit and kill a rich relative–but the familiar journey schema becomes apocalyptic as the bourgeois encounter a world bent on revenge for oppression.

One strategy Godard pursues is to deform narrative by mixing in other formal principles. The later early films introduce passages cast in rhetorical form, as when characters indulge in extensive arguments about philosophy or politics (La Chinoise, Vivre sa vie).

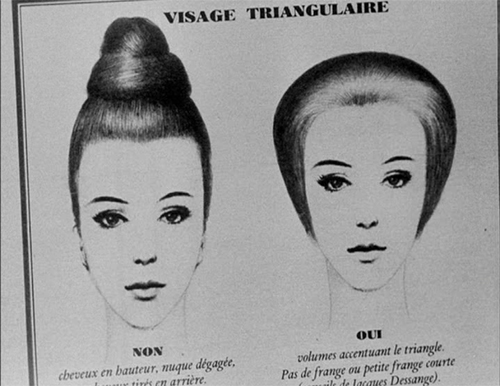

The early work also introduces passages of associational form. More and more often, Godard interrupts the action with cutaways to images that create commentary, analogies, and contrasts. Book titles are the simplest examples, but we also get the shots of fashion advertising interpolated into Une femme mariée and the landscape of consumer goods inserted into Two or Three Things.

With Le gai savoir of 1968, narrative is sidelined altogether as the primary characters conduct a political deciphering of a cascade of mass-media images.

The late 1960s-early 1970s quasi-Maoist films that Godard made with Jean-Pierre Gorin, sometimes under the rubric of the Dziga Vertov group, rely mostly on rhetorical and associational form, as in One Plus One and Pravda. Vladimir and Rosa, however, returns to narrative in providing a caricatural replay of the trial of the Chicago Eight, and Tout va bien is like the early work in embedding its political commentary in a more or less linear plot line.

After the break with Gorin, Godard continued to mix narrative and other formal options in Numéro deux, Ici et ailleurs, and several striking documentaries of the mid-1970s. Seen today, Comment ça va looks ahead to both the style and the construction of his late films in tracing two couples caught up in the politics of the mass media.

Style as rewriting

JLG par JLG (1995).

By emphasizing Godard’s reliance on narrative principles I don’t mean to reduce his originality. Like a Cubist painter creating a portrait or a still life, he needs some norms in order to introduce his disturbing deformations. He gives with one hand and takes away with the other, and to feel his work’s disruptive force we need a tacit background of what’s ordinarily done.

The same holds for matters of style. Most scenes in the early films rely on standard continuity, as I tried to show in one chapter of Narration in the Fiction Film. Even a film as fragmentary as Vladimir and Rosa depends on eyeline-match cutting.

Godard’s limited obedience to standard style makes the deviations stand out. In the shots above, the curtain background forestalls expectations of real space. Often the calculated disruptions of continuity have an arbitrary air, as if there’s no particular motivation except the opportunity to try something new. The celebrated jump cuts in Breathless, for example, seem to have no specific functions as motifs or narrative cues. They register as glitches, gratuitously spoiling a shot. Like DJ scratches and skips in hip hop, they come to form percussive passages that can be appreciated for themselves.

The early films try everything: labyrinthine camera movements, shots too short to be grasped, abrupt dropouts of sound and image, wisps of voice-over. Drama could be punctured or entirely suppressed. Alphaville expands a moment of suspense into a lyrical interlude, while Un petit soldat, after arousing our concern for the woman the hero meets, shoves her torture and death offscreen, reported in a tossed-off line of dialogue. All of cinema was simultaneously available to the New Wave directors, who at Langlois’ Cinémathèque saw a Griffith film alongside a Nicholas Ray picture. Godard gleefully ransacked film history, while deforming each device to see what he could make of it.

For example, Godard gave new life to a compositional option I’ve called planimetric framing. The camera shoots figures perpendicular to the background and places those figures frontally or in profile. Earlier it had been an almost ephemeral moment. Godard makes it a stylizing gesture, offering pictorial abstraction that short-circuits naturalistic drama (Pierrot le fou, Two or Three Things I Know about Her, Vladimir and Rosa).

What binds these all stylistic tactics together, I think is a broader narrational strategy. Godard carries the auteur theory to a new limit. In watching the film, we become aware not just of “a narrator” but of a specific agent, Godard the director, who insists that his story world is created and transformed by the practices of cinema. This isn’t just “Brechtian” distancing but persistent signs of this particular filmmaker’s creative work. Godard invites us to admire his sometimes annoying audacity.

The intertitles are the most evident signs of this agent’s activity, but so too are the unrealistic staging, the abstract compositions, the geometric camera movements, and especially the manipulations created in post-production. Sound mixing cuts off noises, muffles dialogue, provides anonymous voice-overs, scatters audio across many channels, and wedges in chunks of music. Post-production is seen as offering the filmmaker’s final, if sometimes inconclusive, revisions of his creation. It’s as if a novel were published as the copy-edited and marked up proofs of the author’s manuscript.

Critics are fond of saying that 1960s Godard changed the language of cinema. That’s sort of true, but we should remember things that were abrasive or alluring in his films have mostly been tamed by their assimilation to mainstream uses. Chapter breaks and intertitles are now recruited to create coherent story connections, as in Tarantino. The handheld camera is commonplace, but it serves chiefly as a wavering substitute for standard framing. His planimetric framings create a painterly abstraction, but in the hands of Wes Anderson they function as seriocomic establishing shots. Today’s directors use jump cuts mostly to compress time between stages of an action, not to annoyingly break the flow. And even our filmmakers who treat auteurism as a brand do not create the sense of the filmmaker’s hand fooling with every image and sound on the fly. Godard’s unpredictable tweaking asks us to adjust to a film that will undercut its own effects.

It makes me revert to a quotation I’ve used before. Supposedly Picasso told Gertrude Stein: “You do something new and then someone comes along and makes it pretty.” It’s worth noting that as mainstream films adopted his early technical tics, Godard abandoned most of them. His later work locks down the camera, favors depth staging over planimetric flatness, and avoids jump cuts. Three separate, disjunctive shots in Hélas pour moi show how he can reinvent continuity jumps, this time to harshly italicize a gesture: departure.

Late films: What the hell is going on?

Film Socialisme (2010).

The late films of Godard are tremendously varied, and I can’t claim to have seen, let alone assimilated, all the shorts and medium-length projects. But consider just two main types of features. There are the “film essays,” the prototype being Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988-1998). His last feature, The Image Book, is also an instance.

I’m disinclined to call them essays, since the ones I know don’t coherently marshal evidence to support a line of argument. They’re largely associational collages of found footage, suggesting pictorial or conceptual links among them. If you want a literary analogy, the poetry of Whitman or Pound would be close. The collage films also have rhetorical overtones, presenting ideas about, for instance, the way Hollywood evolved after World War II in Histoire(s). In its mixture of rhetorical and associational patterning, Le gai savoir was a rough prototype for the collage films; they simply delete the characters whose dialogue frames a flurry of images and substitute Godard’s own voice, or a merger of other voices.

I’m in that minority of Godardolators who find the collage films of limited interest. I find the philosophizing often facile, the claims about film history too broad, the politics obscure and even naive. Most essays take opposing views seriously enough to confront them, but Godard doesn’t rebut positions. He contents himself with post-production reworking of the imagery, twiddling the knobs to destabilize the image. As in the early films, his documentary images can’t escape transformation by the all-powerful filmmaker. At the least, comments might be scrawled on the images. But there will also be superimpositions, spasmodic slow motion, and freeze frames. Color values are garishly recast and aspect ratios pinched or stretched (Histoire(s), The Image Book).

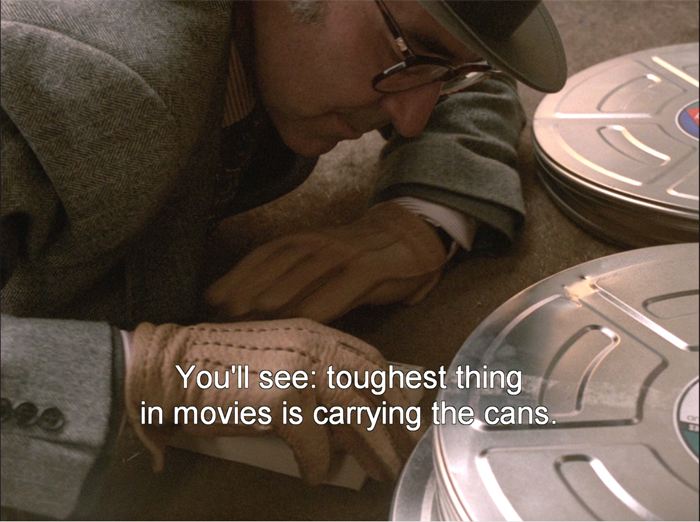

The demiurgic filmmaker can’t leave any picture alone. And of course his voice will guide the soundtrack. Other auteurs have a discreet signature; Professor Pluggy, thanks to all those RCA cables, gives us incessant audio graffiti.

For me the triumphs of the late career are the narrative features. Just as the early films deformed norms of classical storytelling, these can be taken as a continuing dialogue with contemporary “art cinema,” that psychologically-driven filmmaking that explores characters’ minds and relationships. While art-cinema narration sometimes challenges the viewer, Godard goes much further.

Again, story entices us. The late films return to situations he has long relied on, usually involving a romantic couple but sometimes also a family, as in the second section of Film Socialisme. There are recurring arcs of action: seduction and courtship, a dissolving couple, an investigation, or an artistic project–recording a song, making a film. There will be at least one long conversation, but also communication through body language, often violence.

The milieu is often that of a workplace–a factory or business, especially that of prostitution or filmmaking. (Passion makes the film studio a parallel setting to the factory.) Godard once said that the most important things in life are love and work, and these concerns supply his late works’ narratives with a recognizable world.

He sometimes provides “braided” plots, tracing two or or more groups of characters, parallel or intersecting. For Ever Mozart bears the label “36 Characters in Search of History.” Such braiding is comparatively rare in his early period. The plot will be partitioned by chapter divisions, but they don’t necessarily mark off portions of a story; just as often they interrupt a scene. Instead of braiding, we may get a sort of geometry, with two or three side-by-side stories–leaving us to sense connections among them. As the late career progresses, I think that those connections become more elusive.

Once we have narrative conventions in place, they can be blocked. Reviewers who confidently sum up a Godard plot don’t do justice to Godard’s astounding resourcefulness in impeding our understanding while still teasing us to try to get it. If the early films interrupt the action, in the later films we have trouble figuring out what the action is.

Bereft of point-of-view shots, visualized memories and dreams, appointments, and deadlines, these films avoid the commonplaces of modern movie storytelling. In that sense his films are “objective” in relying on characters’ behaviors to convey the action. But that behavior is often difficult to understand.

The characters may be unidentified, or inconsistent, or unrealistic in their actions and reactions. Why does the factory boss in Passion carry a rose in his teeth? Where does the twin of Alain Delon come from in Nouvelle Vague? On first seeing Hélas pour moi, I found every image ravishing and every scene baffling.

The most basic exposition about the characters’ relationships is often suppressed. Often you must watch the film several times to figure out kinship and alliances because there is only one hint, not the redundant signaling we get in mainstream cinema. And even when we’ve sorted out the characters’ roles, a scene may not have a clear-cut arc. We might enter the action partway through and leave it before the scene ends.

Part of the difficulty comes from an idiosyncratic style. He favors “troubled” master shots. The action is given a kind of coverage, but with obscure angles, partial framings, and time gaps between shots (alternatively, repetitions of dialogue). The editing of a scene often relies on the Kuleshov effect, with shots of single characters linked through eyelines.

Overall, a scene’s presentation is both sparse and dense. The action is built out of details, but sometimes things get overbusy, with jammed frames and layers of dialogue. And he loves to block our view of faces, by using the frame to decapitate major characters, or to interpose objects that make it hard to understand who’s present, or to tuck faces into apertures.

More blockage: main characters are often turned from us, plunged into shadow, or put out of focus, making expressions difficult to read. Combined with depth staging, these shots challenge us to carve out the prime narrative action (Passion, Éloge de l’amour, Notre musique).

Refusing the Steadicam (and today’s annoying slow track-ins to a character), Godard locks down the camera. He moves his figures through the shot and insists on filling the 1.37 ratio: every zone of space can matter. Any area of the image can harbor a significant gesture or facial expression (Hail Mary, Detective).

Godard’s fastidious attention to the precise image has not prevented him from his characteristic “overwriting” in post-production. The action, inevitably, is interrupted by intertitles. Classical music or ECM samples drop in and out, with a voice-over elaborating on what we see. Not content to let others supply English subtitles, Godard has lately provided his own, or simply suppressed them during certain stretches of dialogue or voice-over.

One result of this obscurity is to redirect our attention. If we can’t comprehend the full story action, we focus on other things, such as the composition of the image, the interplay of sounds, the expressiveness of the music. Alternatively, the absence of clear-cut scenic structure throws an emphasis onto the texts that his characters obsessively read, cite, and recite. And when we do see clearly, there are the faces, given weight by the shots devoted to them (Notre musique, Allemagne année 90 neuf zéro).

There’s also the historical dimension of the deformations. A Picasso still life asks us to compare it to the classic exemplars of the genre. Similarly, Godard asks us to compare his forms and styles to their precedents. Détective, one of the few late films that hark back to classic Hollywood, proffers a mystery (who killed the Prince two years ago?), investigated by three characters. There’s also suspense, and a deadline for payment during a prizefight. Alongside this noirish premise is a Grand Hotel template juggling several couples and romantic triangles. But this “ensemble film,” packed with opaque shots and fragmented scenes, is far from the trim construction of classical Hollywood.

Similarly, Éloge de l’amour, with its quest to grasp the Holocaust, invites us into an art-cinema investigation plot reminiscent of L’Avventura. But instead of a search for a missing person, we get a dense adventure split into two parts (black and white film, trembling color video) that does what it can to cloud the inquiry, while bringing out a critique of Hollywood’s treatment of history.

“The best criticism of a film is another film.” Taking film history as a conversation among filmmakers, Godard bounces off Rossellini’s Germany Year Zero, Pialat’s Sous le soleil du Satan, and Truffaut’s Man Who Loved Women and Day for Night (below, with Passion).

Late Godard has shadowed Tati with distracting long-shot staging reminiscent of Play Time (here, Hélas pour moi) and has paid homage to him in Soigne ta droite.

Even more pervasive is the invocation of Bresson. With a behavioral narrative, sound that replaces image, and the fragmentation of a scene through partial views, Godard seems to take a perverse “next step” beyond the master. Bresson died during the shooting of Éloge de l’amour, so there’s of course an homage, but more generally the late films’ style often radicalize Bresson’s technique, hands above all (Soigne ta droit, Détective).

Godard’s deformations not only “spoil” his own work but point to fresh possibilities in the traditions of narrative cinema.

Moments

Pierrot le fou (1965).

It’s not enough to note all the ways Godard impairs our comprehension of the story. As critics we need to show how the result can still add up to something coherent, even rigorous. We probably won’t be able to clarify everything, but we can try to show underlying patterns, in the way a critic can show a compositional logic underlying a cubist painting. I’ve tried to do this in two installments of our series on the Criterion Channel and in my analysis of Adieu au langage. Check the codicil to this entry for details.

But even if the overall strategy of disruption remains obscure, there’s a lot to engage us otherwise. Godard has given us scores of shots that no one had ever made before. Here are a few of my favorites, apart from ones I’ve already shown (Une femme mariée, Hail Mary, Made in USA, La Chinoise, Détective).

You have your own, I bet.

Given such shots, you can argue that the Godard narrative has been the bait to lure us into savoring privileged moments of cinema. Is this the heritage of Cahiers cinephilia–Godard’s version of “movie moments” that thrill us through what film (and video) can uniquely do? Or are they a refutation of the overblown CGI of Hollywood, showing what kinds of dazzling imagery can be achieved without special effects?

At any rate, such moments are especially resonant in the context of all the uncertainty. In all, we’re left with an aesthetic of exquisite spoilage. Godard teaches us to sense form underneath deformations, while still making imperfection a ripe artistic pleasure.

My references to Godard’s life are drawn from two excellent career accounts, Richard Brody’s Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard (Metropolitan, 2008) and Antoine de Baecque, Godard: Biographie (Grasset, 2010). Brody’s exemplifies what a true “critical biography” should be.

On the Criterion Current, David Hudson compiles links to several Godard tributes. Don’t miss David’s own discerning essay here.

For some years I’d thought of writing a little e-book on Godard, complete with clips. (Why not rip him off as he has done with so many others?) But as I’ve aged I recognized that I’m overmatched. Instead, some entries on this site approach him in bite-size chunks. This piece goes into some detail about his preference for the 4:3 ratio, and how video versions in wider format degrade his compositions. Thoughts about his use of Scope in Le Mépris are elaborated in my Criterion Channel installment of Observations on Film Art. Another Criterion Channel commentary considers the use of the classic ratio in Vivre sa vie. Quick remarks about Le petit soldat are here, based on a visit to Belgium’s Summer Film College. (Visit Cinéa and photogénie to survey the vast number of events and critical studies the College has fostered over the years.)

At another session of the College I offered some ideas about the late films, particularly Nouvelle Vague. (And when will a video version give us the proper 1.37 image for this film? Same goes for Sauve qui peut (la vie) and King Lear.) This entry looks at Godard’s use of Bressonian editing in Hail Mary. Kristin offers a contextual analysis of Film Socialisme, with close consideration of the controversial subtitles. Earlier she took it as an example of the sort of film arthouses should be committed to screening. My comments on that film are here. At the Vancouver film festival KT and I saw 3 x 3D and offered some comments. One entry on Adieu au langage traces some of his 3D tactics, while another considers this film in relation to other late features and offers a detailed analysis of the film’s opening. These essays were revised into the Kino Lorber DVD liner notes.

Soigne ta droit (1987).

An update about our blog

Contempt (Le Mépris, 1963).

DB here:

After fifteen years of fairly steady blogging, we suspended putting up new entries in early October. We were reluctant to go into explanations of a fluid situation, but now things are stable enough for us to set out what happened.

I had surgery for oral cancer in July and August, followed by brief hospital stays. My doctors, all excellent, have said and continue to say that my prognosis for recovery is good. After a hiatus of rest at home, when I posted two blogs, I went in for radiation treatments and chemotherapy. This process took six weeks and has left me very tired, while also dealing with side effects of the treatments and medications.

Since then, I simply have lacked the energy and concentration to write anything new. I try to find time for clerical cleanup work on my book manuscript, Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder. The plan is to submit it for production in March at Columbia University Press.

But Kristin, who has been devotedly taking care of me, and I now have a routine that should permit at least occasional blogging. She will of course provide her annual list of Best Films of the Year for 90 Years Ago, and she has some other ideas. I hope as well to offer something, though naps and streaming always seem to obtrude.

In some ways, there are a couple of substitutes for my blogging–both courtesy of Criterion. One is my video essay on Johnnie To Kei-fung’s Throw Down, “Hidden in Plain Sight.” A look at the movie’s characteristic narrative and stylistic strategies, it’s available on both the Channel and the blu-ray release. I’m grateful to Curtis Tsui, the producer, for asking me to do it; I now appreciate the film a lot more. The other bonus materials are extremely informative as well. If you haven’t seen Throw Down, what are you waiting for?

Before I went into surgery, I recorded two linked installments of our “Observations on Film Art” series. Both concern Godard’s use of aspect ratios. The first, on Vivre sa Vie, is available here. The second, on Le Mépris/Contempt, is here. I try to show how Godard exploits the differences between 4:3 proportions and the anamorphic widescreen format. (In a way, they balance the exploration of Godard’s late-career use of aspect ratios, seen in this blog entry.)

Kristin and Jeff Smith weren’t idle during our hiatus. The Channel released her analysis of the road motif in Pather Panchali and Jeff’s study of Agnès Varda’s editing in Le Bonheur. More installments are planned, of course. We appreciate our loyal viewers who have stuck with us through 45 episodes!

During my confinement, the books have kept arriving on our doorstep, and many deserve notice. I’d be remiss, though, if I didn’t call your attention to a couple of my favorites. One is J. J. Murphy’s monograph on The Florida Project. This in-depth exploration of Sean Baker’s creative process and the contributions of many collaborators is timely, given the release of Red Rocket. Besides, how many authors get the director they wrote about to do PR for them?

The other book is a magnificent contribution to our understanding of cinema: James E. Cutting’s The Movies on Our Minds: The Evolution of Cinematic Engagement. It offers a history of popular films from the standpoint of psychological engagement of the spectator. It shows “how they are structured, and how that structure has been crafted by a century’s worth of filmmakers to affect our minds.” Using Big Data (hundreds of films) and fine-grained analysis of cuts, lighting, and other techniques, James brings in evidence from empirical psychology to show that filmmakers are, as we’ve long known, “practical psychologists.” Beautifully designed with color illustrations, written in a conversational style, it’s destined to be a classic. I hope to blog about James’ book more at length when stamina returns.

It’s been heartening to see that we still get many pageloads every day; some of our efforts seem to endure. In addition, my colleagues here and elsewhere have been wonderfully kind in offering their support during these days. There are still months to go, but Kristin and I remain confident.

Contempt (Le Mépris, 1963).

Wisconsin Film Festival: Footage fetishism

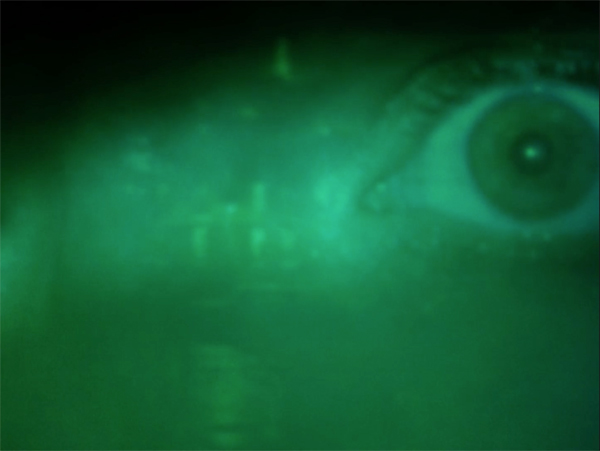

The Green Fog (2017).

DB here:

Kristin and I have been unusually busy during this year’s fest, its twentieth, so I got to see only ten of the vast array of offerings. Herewith a first report on what our intrepid team–Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Matt St John, and Ella Quainton–programmed and put before adoring crowds. Today we look at movies about movies.

JLG par Not JLG

The title of Michel Hazanavicius’s Le redoubtable has been Francoanglicized as Godard mon amour, not a bad way of signaling it’s a French movie. (The same tactic turned Nikita into La Femme Nikita.) The title also lets us know it centered on the most important living director. And the possessive pronoun correctly puts us in the place of the heroine, the late Anne Wiazemsky, whose memoir-novel chronicled her few years with Godard. How could the film not take her side? On my limited exposure to the man, “difficult” doesn’t begin to describe his temperament.

The film omits Anne’s role in Bresson’s Au hasard Balthasar, which Godard admired extravagantly, and takes us briefly through the shooting of La Chinoise (1967). Soon we’re plunged into ’68 debates about making commercial films, making political films, and “making films politically.” We’re firmly attached to Anne, to the point that Godard’s activities at the Cannes festival are kept obstinately offscreen while we see her sunbathing at a villa. There are unattributed voice-overs from an older male, but mostly we’re in Anne’s consciousness as she struggles to live with the torn, cruel, more or less ridiculous man who brought her into the film industry.

As a satire, the film goes for straightforward targets, such as the moments when people come up to our filmmaker and ask why he doesn’t make movies like Contempt any more. That seems to be Hazanavicius’s question as well. He makes no effort to match his film’s style to Godard’s work in the years when the story takes place. It would have been bold, though probably off-putting, to mimic La Chinoise or Le Gai Savoir (1969), one of his most daring experiments, a sort of Child’s Garden of Semiology. Instead we get snatches of pre-1967 scores, chapter titles, compositions, and iconography, with special emphasis on Une Femme mariée (1964), perhaps a sly reference to Anne’s role.

While pastiching the early work, Hazavanicius softens its edges. One of Godard’s minor innovations, for instance, was inserting a chapter title partway through a new section, rather than planting it at the outset. That not only blurs the boundary between segments and usefully jars the viewer, but it also lets the title give a sharper commentary on the images around it. Tarantino embraced this technique, but Hazanavicius is tidier in his chaptering. Similarly, his shoutouts to planimetric framing don’t really exploit their disruptive possibilities.

His film reminds us that Early Godard has become virtually a period style. Hence, perhaps, Godard’s own flight from it over the last forty years, in the process making films of exceptional beauty and abrasiveness. Still, we tend to forget how unsettling the early films remain. (At the Venice International Film Festival last year, Kristin attended the packed 400-seat screening of the restored Two or Three Things I Know about Her and reported that perhaps a third of the audience had walked out by the end.) Despite all his influence, the original Godard will never become “normalized,” just as Schoenberg will never become elevator music.

Godard mon amour goes down easy and doesn’t, to my way of thinking, have a brain in its pretty head. Godard emerges as a wacky celebrity, politically confused and emotionally bullying. There’s no attempt to show how his personality surfaces in his art, or even why his art is important. Still, Godard mon amour usefully calls attention to a director who, in his 88th year, has another feature coming to Cannes. It’s called Livre de l’image, and it promises to be in five chapters, like the fingers of a hand.

Fog over Frisco

Made on commission from the San Francisco International Film Festival, The Green Fog is a collage exercise in associational mode, with echoes of Craig Baldwin’s work. In their own gonzo filmfreak way, Guy Maddin and Evan and Galen Johnson have created an homage to the city and its ultimate film, Vertigo.

It can please on many levels. First, there’s the spot-the-clip quiz in the manner of Marclay’s The Clock. Some bits I found fairly easy to identify, but others are drawn from obscure movies and TV programs. All showcase San Francisco. Second, there’s the looping and twisting motifs of male-female tension, surveillance (films projected, phone lines tapped), and class identity: we’re forced to notice how tony restaurants set the stage for 80s big-hair melodrama.

Then there’s the pleasure of watching how cutting can suggest expanding narrative trajectories through eyelines. The Green Fog is an extended exercise in the Kuleshov effect. Sometimes the whole process gets embedded: people watch screens showing people watching people. Or they’re watching a scene from another movie: McMillan, without wife, sees a tree that was 68 years old when Jesus was born.

These linkages are accentuated by the habit of omitting lines of dialogue, so that characters seldom speak but, in shots plagued by visual hiccups, emphatically react to one another, sometimes just by smacking their lips or gulping.

Not least, The Green Fog is a free fantasia on incidents and images from Vertigo. Although only one Vertigo shot is shown, the canonical moments are evoked by their mates in films both earlier and later: people scrambling up buildings and plummeting, couples embracing in horse stables, men pulling women out of the bay, and–thanks to the invading green miasma–a woman stepping out of a doorway to confront her lover. Scotty’s vision of Judy’s aura is made into a city-wide contagion of obsessive love.

The film takes our memories of bits of Hitchcock’s film and spirals out from them, creating a hallucinatory whirlpool of variations on clichés. Going beyond Vertigo, the film evokes its own vertigo, a media phantasmagoria. I was reminded of Geoffrey O’Brien’s book The Phantom Empire.

How did you wander into this maze, anyway, and how would you get out? Do you in fact want to, or do you prefer to sink deeper into it, savoring its manifold ramifications and outlying distortions?

The teeming image-clusters of The Green Fog, made even more eerie and lyrical by Jacob Garchik’s score, capture the delirium of cinephilia, reminding us of how much a masterpiece owes to anonymous, banal visions pulsing through popular culture.

Right here in River City

William Brinton and his wife Indiana were a colorful couple. They were nudists and kept a mummy in their living room. More to our point, around 1900 they ran an Iowa theatre and traveled throughout the midwest showing films and lantern slides. Brinton died in 1919, Indiana in 1955, and the executor of her estate in 1981.

The Brinton collection passed to Michael Zahs–junior-high history teacher and confessed “saver” of things. Three truckloads of boxes came to Zahs labeled “Brinton crap.” They contained over 130 films, 700 magic-lantern slides, many sound recordings, and a host of vintage equipment.

Zahs was told to bury the nitrate materials and dispose of the rest. Instead he hung on to everything, and eventually the American Film Institute and the Library of Congress selected several reels for preservation. Since 1997 16mm copies of Brinton titles have been shown in festivities at the Graham Opera House in Washington, Iowa–a site recently declared by the Guinness Book of World Records to be the world’s oldest surviving film venue. The University of Iowa Library has committed to keeping safety copies of the entire collection.

This fascinating story is brought to light by Tommy Haines and Andrew Sherbourne of Northland Films. Saving Brinton is, like Bill Morrison’s Dalton City: Frozen Time (reviewed by Kristin here), a heroic tale of cinema lost and refound. Morrison’s film centers on 1910s and early 1920s features, but the Brinton legacy takes us back to earlier times. There are “actualities” (newsreels) and gag reels and even–watch Serge Bromberg’s eyes light up–a lost Méliès. Many items are in superb condition, with well-preserved hand-coloring. There are films from Lumière, Edison, and other major companies. In one, a powerful panning shot shows Teddy Roosevelt parading down Market Street in San Francisco (without green fog) just before the earthquake. And then there are the projectors and paper, including a Pathé catalogue.

Saving Brinton is as much a portrait documentary as an account of film rescue. The Brintons stand out, not least for William’s fascination with airships, but the star of the present-day show is Michael Zahs. With his Darwinian beard and jovial presence, he comes across as one of those impresarios who knows a lot about everything, from chemistry to grave marker symbolism. For four years the filmmakers followed his efforts to preserve and show the Brinton legacy, while also tracing his personal life. We get scenes of his devotion to his ailing mother, who died during filming, and interplay with his wife, a smiling woman who doesn’t mind sharing her household with combustible materials. At the same time, this packed documentary evokes the community that welcomed Zahs’ cheerful obsession. As a graduate of the University of Iowa, I had to beam at the sheer niceness radiating from these people and their town and the earth they steward.

On 23 April the University Library in Iowa City will be screening the whole collection, with seven projectors running the films on loops. You can sample them online, in pretty copies. And Saving Brinton will continue to tour festivals; you can track its progress here. This charming documentary is a must-see for everybody who loves old movies, not to mention flyover Americana.

My quotation from Geoffrey O’Brien’s The Phantom Empire: Movies in the Mind of the 20th Century (New York: Norton, 1993) comes from p. 28.

The Saving Brinton website gives more information on the film. Diana Nollen’s story in The Gazette supplies helpful background. Watch the trailer and glimpse our old friend Rick Altman, emeritus at the University of Iowa.

The Language of Flowers (n.d.).

Watch those hands; or, Burt, Jean-Luc, and Bill come to Cinephile Summer Camp

Nouvelle Vague (1990).

DB here:

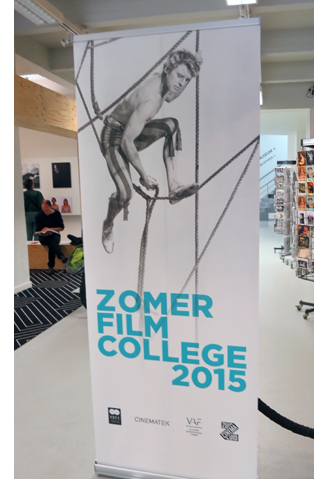

At this year’s Summer Film College in Antwerp, Peter Bosma pointed out that the event seems to be a unique mixture.

Films are screened from morn to midnight: this time, 38 films across 6 days and two half-days. But it’s not exactly a film festival, as there are no new releases.

So is it like Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato? Not exactly. While the shows included some restored titles (notably the Belgian Cinematek’s pretty makeover of Pollyanna, 1920), the films were mostly original prints with an occasional DCP.

So is it like Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato? Not exactly. While the shows included some restored titles (notably the Belgian Cinematek’s pretty makeover of Pollyanna, 1920), the films were mostly original prints with an occasional DCP.

Moreover, the films cluster around two or three major themes. This year we had Late Godard (fourteen titles, counting episodes of Histoire(s) du cinema) and the career of Burt Lancaster (eleven). In addition, there were nightly showcases called “Masterworks in Context,” which included one surprise film, title undisclosed. But unike most movie marathons, the Summer Film College introduces screenings with lectures and discussions. This year there were fourteen sessions, each running about ninety minutes. These are serious, intensely informative talks—very far from the usual brief introductions one gets at festivals or in art house warm-ups.

So is it an educational enterprise? Definitely, but without assignments, tests, or grades. It’s designed to serve Flemish-speaking professors and students, but also civilians who are just interested in a weeklong package of film and film talk. The event helps forge a community of film appreciation.

Finally, there’s often a guest filmmaker on hand, usually related to the main threads. This time it was Bill Forsyth, who directed Burt in Local Hero. That film was screened, along with Bill’s wonderful Housekeeping.

So what would you call the College? I once called it Cinephile Summer Camp, and that still seems accurate in evoking the sense of fun and camaraderie that pervade the place. We don’t all get mosquito bites, but after a week you come to enjoy seeing familiar faces and talking with them about what they’re seeing. Just as when you go to summer camp, you get to stay up late. But at no summer camp I ever attended did we drink so much beer.

JLG/SJ/DB

The principal speakers were Tom Paulus and Anke Brouwers, who covered Burt, and Steven Jacobs on Late Godard. The Masterworks in Context shows were introduced by several guest speakers, including Lisa Colpaert (excellent on I Walked with a Zombie) and Vito Adriaensens (covering both Murder! and Vampyr). For Pollyanna, Bruno Mestdagh of the Cinematek staff explained the process of restoration. I played utility infielder, offering one talk on Burt and three on JLG.

How often do you get to see 35mm prints of Une femme mariée, Passion, Je vous salue Marie, Détective, JLG/JLG, Eloge de l’amour, and Nouvelle Vague? The Godard series, which ended with a 3D show of Adieu au langage, was a high point of my summer viewing. Back home I had prepared by rewatching all Godard’s features from Sauve qui peut (la vie) onward, but my video homework didn’t prepare me for the way the big screen amps up their prickly, seductive power.

I don’t speak or read Dutch, so I missed many subtleties in Steven Jacobs’ talks, but thanks to Power Point I could figure out the main points. Few lecturers can pack so much information and ideas into ninety minutes.

We had no way of knowing how familiar the audience was with Godard, early or middle or late, so Steven started with an orienting talk on JLG’s pre-1980 work (above). He swiftly reviewed key aspects of Godard’s New Wave period, traced his shift toward “a critical cinema” between 1967-1969, and explored the move into his Marxist phase. Along the way, he stressed the way cultural developments like auteur theory, Pop Art, Maoism, Brechtian theatre, and semiotics shaped Godard’s films. Particularly acute was his discussion of the “one image after another” sequence in Ici et ailleurs (1975). In all, the talk was an ideal prelude to Une femme mariée, which pointed up so many motifs of the later work: the focus on the couple, the emphasis on media-based images, and the persisting shadow of the Holocaust.

Steven is an art historian at University of Ghent; he earlier appeared on this blog as co-author of the imaginative book The Dark Galleries. After tracing Godard’s return to mainstream cinema and his move to Rolle, Switzerland, Steven focused on that splendid example of JLG the painter, Passion. Steven has written eloquently on the film in his Framing Pictures, and here he widened his focus to discuss its relation to other films centered on the tableau vivant, like Pasolini’s La Ricotta and Ruiz’s Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting.

You’d expect that Steven would have a field day with Histoire(s) du cinema, and he did. Unlike most Godardophiles, I’m not wild about this series of video essays. I can’t take them as serious studies in film history, and too often I sense he’s just playing around. (Enough with the stroboscopic flashes, okay?) But Steven obliged me to rethink them by showing how they fit into the Postmodern art scene, especially the video art movement after the 1970s. He pointed out the central importance of the Hitchcock episode and the series’ constant concern with the Holocaust, often in dialogue with Shoah. Citing Godard’s claim that video taught him to see cinema in a new way, Steven suggests that the format also created a tenor of paradoxical melancholy. It’s as if JLG’s experiments with this new technology drove him to celebrate the death of the cinema he knew.

My three talks on Late Godard tried to ask something that I didn’t find many traces of in the literature. What are these films doing with (or against) narrative? I think that the focus on JLG as “film essayist” has sometimes obscured the fact that he has long insisted that he needs stories. Yet he seems to have no interest in the craft of storytelling as we understand it. He avoids dense exposition, careful foreshadowing, well-timed revelations, and cumulative climaxes. He tends to spoil the narrative expectations he sets up.

As a result, his plots—for his films have them—are distressingly opaque. Exactly what happens in a Late JLG film is often difficult to determine. I’m always surprised when discussions of these late films provide capsule plot summaries, for the very difficulty of arriving at these should claim our attention. As just one instance, many critics seeing Adieu au langage for the first time thought the film centered on one couple. It centers on two. But the fact of that mistake ought to interest us enormously: What in the film’s presentation made it difficult to follow the basic situation? Are there strategies Godard follows in creating his apparently willful obscurity?

Godard’s unique strategies of storytelling are carried down into felicities of visual and verbal style. Again, I think that critics haven’t sufficiently acknowledged just how strange and opaque the surfaces of these movies are. For one thing, characters are unidentifiable from scene to scene, thanks to camera setups that cut off their faces, wrap them in shadow, or leave them offscreen altogether.

I’ve touched on these matters earlier (here and here), but just as a quick example, consider this shot from the opening of Nouvelle Vague. It has to be one of the most oblique introductions to a protagonist we can find in cinema.

Corporate owner Elena Torlato Favrini strides out of her mansion past her chauffeur while taking a transatlantic call. Any other director would favor us with a close view of her, perhaps tracking as she cuts a swath through her entourage. Instead we get a shot framing her chauffeur climbing out of their Mercedes.

As he crosses in front of the car, we hear her on her cellphone. She can be glimpsed fleetingly in the background, through the car window.

She approaches us, becoming briefly visible as she passes the car, but when she stops, she’s decapitated. We don’t get anything like a good look at her, and the locked-down camera refuses to reframe her. Instead, the framing emphasizes her slipping on her gloves.

The gesture ties into other imagery in the film. A little before this shot, there’s an isolated shot that establishes hands as a major motif in the film. But we should also notice that this fairly abstract shot also presents the gesture of Elena slipping on a glove. Or rather, it almost presents it, as the shot is abruptly chopped off just as the gesture begins.

So slipping on the glove, started in an earlier shot, is finished at the Mercedes. But just as important, the visual idea of a hand gesture broken by a cut resurfaces at the climax. When Richard Lennox helps Elena out of the water, the action is also incomplete. Only five frames show him grabbing her arm before a cut interrupts the action.

Another filmmaker would have held the image on that triumphant grip, but Godard denies us this little burst of satisfaction. Of the five frames in this bit of the shot, there is just one frame showing Richard’s hand seizing her. Godard again spoils a solid narrative effect. But he does narrative in his own way, with the broken-off gestures counterpointed by the hands that do meet at other points in the film.

Every scene in Nouvelle Vague, and most scenes in Late JLG, seem to me to be built on one or more fine-grained pictorial and auditory ideas like these. Those ideas can seem perverse, as in the chauffeur scene: why let us see his face but play down Elena’s? He’s not a major character; we don’t even learn his name until the film’s final moments. Unhappily, this peculiar instant of comparison is lessened in the 1.66 version of the film available on DVD. That image suppresses the driver’s face no less than Elena’s, losing Godard’s peculiar version of “gradation of emphasis.”

All the more reason to try to see these films in their full-frame glory, as I’ve argued before.

BL (Beautiful Loser)/AB/TP

Criss Cross (1949).

With big tousled hair, unadulterated sinew, and teeth gleaming like a Pontiac grille, Burt Lancaster came to fame in the late 1940s. He belonged to a new cohort of actors quite different from the 1930s Debonairs (William Powell, Melvyn Douglas, Cary Grant) and the Bashful Boys (Cooper, Fonda, Stewart). Yet the new lads were also at variance with the rugged Ordinary Joes (Cagney, Bogart, Tracy, Gable).

For one thing, Lancaster, Victor Mature, Robert Ryan, Robert Mitchum, Kirk Douglas, and Charlton Heston were brawny—monsters, in a way. They often took off their shirts. One publicity still for River of No Return shows Mitchum more unclothed than Monroe. Three of them played prizefighters, and Mitchum, himself a boxer, had the broken nose of a brawler.

For one thing, Lancaster, Victor Mature, Robert Ryan, Robert Mitchum, Kirk Douglas, and Charlton Heston were brawny—monsters, in a way. They often took off their shirts. One publicity still for River of No Return shows Mitchum more unclothed than Monroe. Three of them played prizefighters, and Mitchum, himself a boxer, had the broken nose of a brawler.

Of the group, Burt had probably the strongest A-list career overall. He fostered a great variety of projects. Who else of his generation appeared in films by Visconti and Malle? What other unflinching liberal was prepared to play a US general bent on a coup (Seven Days in May) or a conspirator behind the Kennedy assassination (Executive Action) or an obstinate officer fighting in Vietnam (Go Tell the Spartans)? He portrayed a renegade officer demanding the revelation of the brutal policy behind the Vietnam War (Twilight’s Last Gleaming). His closest rival and frequent costar Kirk Douglas didn’t enjoy such a vigorous and prestigious twilight. Only Brando kept beating him to the prize: Burt wanted to play the lead in Streetcar Named Desire and The Godfather. Unpredictably, he wanted as well to play the gay prisoner in Kiss of the Spider Woman.

I had had only slight interest in Burt as a star before this edition of the Summer School. But listening to the talks, seeing the films, and preparing my contribution made me realize how extraordinary an actor he was, and how important in Hollywood postwar history. Burt was well-served by the fine lectures offered by Tom Paulus and Anke Brouwers.

Anke provided an in-depth survey of how Burt and the Brawny Gang brought to a new level the culture of male athleticism—on display in Fairbanks and Valentino, developed further in the body-building craze of the 1930s, and culminating in what one 1954 magazine article called Hollywood’s “Age of the Chest.” She brought in forgotten pin-up boys like Guy Madison and pointed out how Burt and his peers paved the way for Rock Hudson and Tony Curtis. Anke went on to specify Burt’s beefcake persona, established in The Flame and the Arrow (1950) and locked into place in The Crimson Pirate (1952), which we saw. In her followup talk next day, she surveyed Burt’s place in the industry. He was one of the few stars to supervise a successful independent production company, Hecht Hill Lancaster (earlier, Norma Productions and Hecht Lancaster).

Tom moved on to consider Burt’s star charisma. He traced how Burt adjusted his authoritative image to different roles—the con man, the confident leader, the embittered idealist. Tom was especially good at analyzing Burt’s acting technique, tying it to particular trends in theatre and film of the time and pointing up the physicality of his performance of specific, precise tasks. Given the standard situation of rigging a bomb, he contrasted Burt’s meticulous finger work in The Train (1964) with that of Kirk going through the motions in The Heroes of Telemark. Tom even spared some time for Burt’s diction—a quality that really popped out when we watched Elmer Gantry (1960).

In a later lecture, Tom surveyed “Late Burt,” and his relation to political cinema of the 1960s and 1970s. He followed that with a revealing account of Burt’s relation to the trend of “Mexican Westerns” launched in the 1950s. Another arc in Burt’s career: from Vera Cruz (1954) to Ulzana’s Raid (1972), with The Professionals (1966) in between. That we saw in another gorgeous print.

I could go on a lot more about Tom and Anke’s lectures, but I don’t want to give away too much. The talks contained so much original research and discerning analysis of both the films and trends within film history that I’m hoping Tom and Anke will lay these ideas out at book length. Part “star study,” part film criticism, part industry history, their lectures were exhilarating.

My own contribution was minimal, a talk on First-Phase Burt. The Brawny guys were well-suited to the trend toward hard-boiled movies, those crime pictures we later decided to call “noirs.” Those weren’t usually suitable for older players (though there were some makeovers, such as Dick Powell and Fred MacMurray). To fill these roles came Alan Ladd, Glenn Ford, Dana Andrews, and Richard Widmark, along with the beefcakes. At the same time, “independent” producers within the studios began contracting their own new talent and loaning it out. Burt was signed by Hal Wallis at Paramount, who also had Kirk Douglas, Wendell Corey, and Lizabeth Scott in his stable. Films like Desert Fury (1947) and Sorry, Wrong Number (1948) were Wallis package projects.

Hired straight from the stage with no film experience, Burt debuted as the Swede in The Killers (1946), on loanout to Mark Hellinger at Universal International. Burt benefited from a galvanizing entrance. Lying on a bed in the dark, refusing to flee the hitmen on his trail, Burt is a shadowed, curiously languid torso in a tight undershirt.

Only after a beat do we see something else: massive hands rubbing a weary head. Soon that head is revealed.

As the killers burst in, the whole image comes together.

Has a Hollywood beginner ever been given such a gift as this opening?

With this onscreen wattage, it’s all the more striking that this young discovery is curiously absent from his early films. He’s onscreen for only a third of The Killers’ running time, and not even half of Brute Force (1947) and Sorry, Wrong Number. The film Wallis wanted to be his debut, Desert Fury (1947), gives him only twenty-three minutes out of ninety, and in the second male lead at that. All My Sons (1948) puts him in an ensemble drama. I Walk Alone (1948), the Norma production Kiss the Blood Off My Hands (1948), and another Universal project, Criss Cross (1949) start to make him a proper, central protagonist. By then, he is ready to become the star attraction of the swashbuckling films.

Moreover, in his early phase, he mostly plays losers. Not the brightest guy in the room, he’s easily suckered by a femme fatale in The Killers and Criss Cross. He makes amateurish mistakes at crime (Sorry, Wrong Number) and, coming out of prison, he is the last to realize the rackets have gone corporate (I Walk Alone). At the start of Kiss the Blood he punches a man too hard and kills him. He’s caught and whipped and imprisoned, and when he comes out he stumbles back into crime again. He’s shrewd enough to set up a prison break in Brute Force, but so doggedly determined is he to reunite with his girl on the outside that he launches a suicidal bloodbath.

When he finally catches on to his fate, we get expressions ranging from stupefaction to anguish (The Killers, Criss Cross).

He even cries (All My Sons, Kiss the Blood).

Loser or winner, when he is onscreen, he has the outlandish physical presence of the born star. Most obvious is a physique (Kiss the Blood, Brute Force).

Even his back, featured with a prominence we get with few other actors, is straining against a drenched prison uniform (Brute Force) or a tailored suit (Criss Cross).

The face was a cameraman’s dream; it could be craggy or somber, thoughtful or tormented (The Killers, Brute Force x2, Criss Cross).

He can be stiff-armed and zombielike coming out of prison in Kiss the Blood, but he can also gamely cock his elbows, ready to spring, like Cagney and Cary Grant (I Walk Alone).

The enormous hands, which look likely to crush a skull (Criss Cross) or rip apart a phone cord (Sorry, Wrong Number), could be surprisingly delicate, tentatively touching his girlfriend’s wheelchair or laying down plans like playing cards (Brute Force).

In The Killers he makes skillful use of those hands, pocketing his busted one or spreading out the scarf given him by the treacherous Kitty.

Easily taken in by Kitty’s plan, he seems to have a qualm when his gripping embrace relaxes and the fingers splay in hesitation.

This sort of handwork would become crucial, as Tom pointed out, to Burt’s performance style, particularly in The Birdman of Alcatraz.

“I’d never looked in eyes as chilling as Lancaster’s,” Norman Mailer once said. You can see what he meant.

Again, though, the actor is in control. Some years back I wrote that eyes by themselves aren’t very expressive: the eyelids, eyebrows, and mouth tell us more. I still think that’s right, but Burt manages to convey the sense of the beast at bay with remarkable control of just the eyeballs. He seems to be looking for an escape hatch without moving his head an inch.

While Burt was playing losers, his counterpart Kirk Douglas was often playing heels—cynical manipulators who stomp on everybody else, as in I Walk Alone. Sometimes Kirk learns his errors (Young Man with a Horn, 1950) but several roles of the period, in Out of the Past, Champion, and Ace in the Hole, make him a glib villain or tawdry antihero. Somewhat later Burt explored this characterization too, notably in Vera Cruz, Elmer Gantry, and The Rainmaker (1956). How did he shift from the beautiful loser to the fast-talking con artist?

I think there are hints from the start. In The Killers, after he’s washed up as a fighter, the Swede goes in for street crime. When he confronts his old friend the cop, Lancaster brings those arms and hands into play. In his enormous unstructured topcoat, he lifts his fists up to his waist. It’s both the businessman’s getting-down-to-brass-tacks sweep, but also a kind of puffing up, exposing that massive frontal expanse. Little Sam Levene can grasp his lapels, but he doesn’t stand a chance against this.

Burt uses the same imperious gesture when, in Sorry, Wrong Number, he’s trying to bully a company employee into joining a crooked deal.

In these noir movies, his intimidation of others won’t put him ahead of the game. But perhaps these arm movements begin to sketch a more flamboyant loser like Gantry. By striking what actors used to call an “attitude,” Burt could start to build an entire character: a hell-for-leather charlatan.

Seeing the films, listening to Tom and Anke, and studying Lancaster’s work on my own brought home to me again the importance of the details of performance and the presence of a star. These movies would be utterly different if Mitchum or William Holden played the Burt parts. Our actors don’t wear masks or Hazmat suits. We’re powerfully affected by what they bring to the character in voice, body, face, and gesture—the expressive dimensions of cinematic presence.

BL/JLG/BF

College coordinators Lisa Colpaert and Bart Versteirt, flanking Bill Forsyth.

What do Burt and JLG have in common? For one thing, some images from Criss Cross in Histoire(s) du cinema 1a (see above). For another, Bill Forsyth.

With the success of Gregory’s Girl (1981), Bill was invited by David Puttnam, then at Columbia, to make a Scottish movie with a couple of American actors. The result, Bill says, now looks to be a “soft-core environmental movie.” Local Hero (1983) remains much loved, and for good reason. It makes nearly all of today’s multiplex raunch look adolescent. It has a tone of civility, an embrace of eccentricity, and a genuine interest in people reminiscent of Ealing comedies. For me it’s a masterpiece of sweet, light-hearted art.

Local Hero feels loose and leisurely, but it’s actually a very economical movie. The first few minutes should be studied by screenwriters interested in tight exposition and fast attachment to a protagonist. It’s peppered with sidelights on its central drama, such as the Russian’s song about how “even the Lone Star State gets lonesome.” That neatly sums up the situation of the yuppie sad sack MacIntyre (“I’m more of a Telex man”) learning about village life. As usual, I was moved by Mark Knopfler’s plangent score, the electronic overtones meshing with the pulsations of the Northern Lights.

Burt’s role is that of CEO deus ex machina. Having assigned Mac to buy a Scottish seacoast town for an oil refinery, Mr. Happer eventually descends in his chopper and decides to establish a laboratory there instead. Burt’s crisp delivery and tight fingerwork are still on display at age seventy. The other actors don’t use their hands as much as he does–partly so they’re not distracting us from him, I suspect, but also because newer-style Hollywood acting doesn’t encourage it. In any case, as usual Burt uses his acrobat’s sense of physicality to intensify his performance. Even clasping his hands behind his back tells about the character’s authoritative dignity.

Bill learned that Burt regretted not doing more comedy, so he wrote the mogul’s part with him in mind. Burt signed on eagerly. He showed up on the set with a full beard, hoping Bill would let him keep it; they compromised on a mustache.

Bill had worked mainly with teenage actors on That Sinking Feeling (1979) and Gregory’s Girl, so Burt was really the first adult performer he ever directed. Across their three weeks together, Burt demanded nothing, except that he wanted to loop his dialogue. Bill preferred not to loop, and as it turned out only one scene needed to be rerecorded.

Burt and Bill skipped lunch in order to prepare the next scene, becoming “lunch bums.” Bill remembers Burt hanging out with the other actors and chatting with extras. He freely made fun of Bill’s accent: “”He speaks no known language.” He told Bill: “I don’t know what you’re saying, but I know what you mean.”

Bill talked as well about his own career. Starting out in the days before home video, he learned dialogue and pacing by audio taping classic films. (Sounds like a good idea to me.) He became a performer’s director. “The only thing I’ve ever said to a cameraman is: ‘Accommodate the actors.” He quoted Burt approvingly: “The space in front of the camera is the actor’s space.”

What’s the connection to JLG? It turns out that Godard was the director Bill most admired in his salad days. During the 60s he sated himself on art cinema, especially New Wave imports. When he saw Pierrot le fou, he left the theatre stunned. Godard became “the master. He still is, for me.”

Accordingly, Bill’s earliest cinema efforts were in an avant-garde vein. One piece, puckishly called Film Language, started with ten minutes of black leader while a text by Beckett was read out. Another, Waterloo, included a vast ten-minute shot in which the camera left one household, climbed into a car, rode a great distance, and ended up in another home. The film played at the Edinburgh film festival to an audience of 200. By the end three viewers were left. “I’d moved my first audience.”

Bill remarked that he sometimes regrets not sticking with experimental media. Today, he says, he might be a video-installation artist. A teasing idea. But we should be grateful that we got his features. I don’t know if Jean-Luc would agree, but I bet Burt would.

Thanks to Bart Versteirt, Lisa Colpaert, and their colleagues for a great week. Thanks as well to the participants, whose willingness to take on anything we threw at them was very encouraging. And a farewell to two friends who have projected films at every Summer Film College I’ve attended over the last sixteen years: Esther Dijkstra and Joost De Keijser. They have helped make the event the splendid enterprise it is.

Peter Bosma’s informative book Film Programming: Curating for Cinemas, Festivals, Archives is available here.

A detailed “index of references” for Histoire(s) du cinema is provided by Céline Scemama.

Our first encounter with Bill Forsyth was at Ebertfest. For more on actors’ handiwork, try this entry.

An eager crowd of campers awaits Adieu au langage.