Archive for the 'Directors: Green' Category

Long live French cinema at VIFF: A guest post by Kelley Conway

Chocolat (2016).

Kelley Conway, one of our colleagues here at UW–Madison, is an expert on French film; we talked about her latest book, a study of Agnès Varda, here. We invited her to contribute to our blog, and here’s the result.

David and Kristin introduced me to the pleasures of Vancouver and its superb festival, VIFF. Hats off to Alan Franey and the other programmers who created a strong and varied lineup of films. I saw excellent works from Romania (Sieranevada), Poland (The Last Family), Canada (Maliglutit), and Iran (The Salesman), but here I will address some of the strongest selections from France.

Shopping till she drops

Now and then, the French make films that marry the conventions of art cinema and popular genres. François Ozon’s postmodern pastiche 8 Women evokes both the musical and the thriller. Claire Denis’s art-horror hybrid Trouble Every Day is contemplative and painterly, but also bloody and scary. Olivier Assayas continues the tradition by combining the traits of art cinema and Gothic horror in Personal Shopper, his second film featuring Kristen Stewart as a loyal assistant to a famous woman. While The Clouds of Sils Maria (2014) turns on the intense, shifting relationship between Stewart and an aging theater actress (Juliette Binoche), Personal Shopper is about a grieving young woman with little emotional connection to her celebrity boss (Nora von Waldstätten).

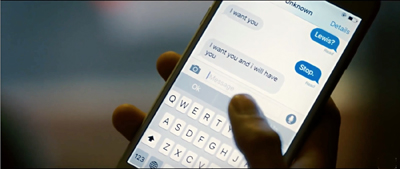

By day, Maureen (Stewart) makes the rounds of Chanel and Cartier, shopping for her employer; by night, she attempts to communicate with her recently departed twin, Lewis. The film’s links to the Gothic are established early on, when Maureen spends the night in a big, drafty house, awaiting a sign from her brother. Shutters bang, wind blows, and spectral figures attack. The supernatural is juxtaposed with the everyday; like so many twentysomethings, Maureen works in a job she hates in order to pay her rent.

Interestingly, she’s really good at this job. Wearing jeans and sneakers, she strides into exclusive boutiques, expertly chooses belts, bags, and baubles worth thousands, and transports them across Paris, skillfully navigating traffic on her scooter. At one point, she makes a quick trip to London to pick up a few dresses. Maureen tracks her employer’s movements via celebrity journalism on the internet and notes with satisfaction when the fashion maven wears the items she has chosen. But this is as close as Maureen gets to the rarefied world of high fashion; she is explicitly forbidden from trying on the beautiful things she covets. When she eventually breaks this rule, she must contend with the consequences.

Personal Shopper divided critics; the film’s Cannes premiere apparently elicited both hisses and a standing ovation. Stewart’s tendency to mumble here can indeed irritate. But the film’s conclusion offers a satisfying mix of suspenseful communication with the dead and art-house ambiguity.

Rape, violent videogames, and other breaches of Parisian decorum

Like Personal Shopper, Elle (Paul Verhoeven) plays with genre conventions. The film opens with a black screen and the offscreen sounds of moaning that could signify pleasure or pain. It’s pain, as it turns out: Michèle (Isabelle Huppert) is being raped on her living room floor by a masked intruder. Later, she calmly cleans up broken glass and soaks in the bathtub. When a circle of blood emerges from between her legs, staining the bubbles, she sweeps it away. She tells her close friends about the rape, invests in pepper spray and an ax, and takes a shooting lesson.

Are we in for a rape-revenge film? Or perhaps a poignant drama about a woman who finds the strength to rebuild her life after a traumatic event? Not exactly. The film references rape revenge and melodrama, only to veer away from these traditions toward an uneasy pairing of satiric comedy and thriller. The film is filled with events typical of a French film about middle aged Parisians in a bourgeois milieu: well dressed people get together for dinner in excellent restaurants, the successful completion of a project at work is celebrated with an elegant party; Michèle loses her mother to a stroke, but gains a grandchild.

But Michèle also runs a company that makes violent and misogynistic video games, is hated by her employees, and mocks her admittedly ridiculous mother and son in public. The film’s revelation of a traumatic event in Michèle’s childhood might have been used to motivate her cynicism, but traditional narrative causality is not on here. Peoples’ reactions to events in Elle are always somehow “off.” The film’s upbeat conclusion is particularly confounding: key characters appear to have changed for the better, but we don’t know why.

Is the film an allegorical treatment of the toxic relationships between men and women? Perhaps. Michèle exhibits behavior often attributed to men. In a reversal of Laura Mulvey’s classic analysis of voyeurism, she spies on a neighbor she finds attractive, holding binoculars in one hand and masturbating with the other. She mechanically performs sexual acts without even pretending to be interested in her partner. She sexually humiliates an employee and sleeps with a friend’s husband because she “felt like getting laid.”

Elle hangs tenuously by its manicured fingernails to European art cinema. The film was directed by Dutch filmmaker Paul Verhoeven, better known for his Hollywood films Robocop (1987), Total Recall (1990), and Basic Instinct (1992) than for his work in Europe. Elle is a hybrid of Tie Me Up, Tie Me Down (1989) and The Piano Teacher (2001), borrowing Almodovar’s rape victim fascinated with her rapist and Haneke’s masochistic ice queen, also played by Huppert. Elle will intrigue and amuse some viewers and disgust others.

The film has been submitted to the Academy as France’s entry for Best Foreign Film. Huppert herself has never been nominated for an Oscar and she certainly deserved a “best actress” award for any number of the films she has made with Godard, Chabrol, Haneke, and Denis. This may be her year: her intriguing cipher in Elle and her subtle performance as a philosophy teacher in Mia Hansen-Løve’s Things to Come (2016), also playing at VIFF, both merit recognition.

Race under the big top

French superstar Omar Sy stars in Chocolat (released as Monsieur Chocolat), a Gaumont biopic about Rafael Padilla. Padilla was an Afro-Cuban who escaped abject poverty to become a famous clown in Belle Époque Paris. The film recounts the early period of Padilla’s career in a provincial circus, where he masquerades as a cannibal. The clown George Footit, played by James Thierrée (a grandson of Charlie Chaplin), sees his potential and they form a duo. Discovered by impresario Joseph Oller, they become “Footit and Chocolat,” and perform nightly at the Nouveau Cirque in Paris.

The film’s rags-to-riches tale condenses and alters the multiple phases of Padilla’s career; he actually enjoyed solo success in Paris before he met Footit. Still, the film succeeds at revealing the clown’s comic talent and physical grace. Padilla is initially naïve and good-natured, like the auguste clown character he plays in his act with Footit, but his rage grows at having to play the perpetual fool. He abandons the act and tries to mount a career in the theater playing Othello, but ends up back in a provincial circus, broke and sick.

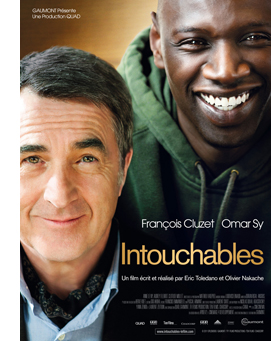

At first glance, the plot of Chocolat resembles that of Zouzou (Marc Allégret, 1934), another all-too-rare French film featuring a black protagonist. In Zouzou, Josephine Baker plays a laundress who becomes queen of the music-hall, but loses the man she loves (Jean Gabin) to her blonde best friend. Chocolat is more self-conscious about its racial politics and, in a way, can be seen as a riposte to the controversy around Sy’s earlier hit, Intouchables (Olivier Nakache and Eric Toledano, 2011). In Intouchables, a wealthy, white, disabled man (François Cluzet) hires as his aid a young, black man (Sy) from the banlieue; friendship, humor, and mutual respect ensue. Intouchables was phenomenally successful at the box office, nearly overtaking the top-grossing French film of all time, Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis (2008). But it had a complicated critical reception. (See the codicil.)

At first glance, the plot of Chocolat resembles that of Zouzou (Marc Allégret, 1934), another all-too-rare French film featuring a black protagonist. In Zouzou, Josephine Baker plays a laundress who becomes queen of the music-hall, but loses the man she loves (Jean Gabin) to her blonde best friend. Chocolat is more self-conscious about its racial politics and, in a way, can be seen as a riposte to the controversy around Sy’s earlier hit, Intouchables (Olivier Nakache and Eric Toledano, 2011). In Intouchables, a wealthy, white, disabled man (François Cluzet) hires as his aid a young, black man (Sy) from the banlieue; friendship, humor, and mutual respect ensue. Intouchables was phenomenally successful at the box office, nearly overtaking the top-grossing French film of all time, Bienvenue chez les Ch’tis (2008). But it had a complicated critical reception. (See the codicil.)

Mainstream French critics saw Intouchables as a fun buddy film, but others denigrated the film for its “televisual” look and its simplistic class politics. But after a Variety critic denounced the film for its “Uncle Tom-ism,” the French rallied around the film, presenting a more unified stance in favor of Intouchables as a welcome step in the move toward racial equality on the screen. Chocolat, for its part, underscores more overtly the racism Padilla experiences. The plot invents an episode in which he is arrested and tortured for not having his identity papers, and it shows his mortification at the sight of Africans performing their exoticism for the pleasure of Parisians at the Colonial Exhibition. Chocolat is well worth seeing for its lively portrait of Belle Époque popular entertainment and for its role in the ongoing debates about French cinema’s representation of race and its place in the blockbuster economy.

Simple, strongest

The Son of Joseph might be the only comedy made this year that pays homage to Bresson, Caravaggio, and the nativity story. In this austere yet witty film, brooding teenager Vincent (Victor Ezenfis) seeks the identity of his father. His single mother Marie (Natacha Régnier), a compassionate nurse, has kept this knowledge from him, and with good reason. Oscar (Mathieu Almaric) is a philandering and pretentious publisher who cannot even remember the names of his three legitimate children, much less acknowledge Vincent.

At a book launch party (in which Parisian intellectual pretension is deliciously skewered), Vincent spies on Oscar. Later, Vincent is hiding under a divan when the louche publisher beds his secretary. Vincent eventually finds a surrogate father in Oscar’s kindly brother Joseph, played by a Fabrizio Rongione, a favorite of Eugène Green and co-producers Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne. Like many of the adolescents in the Dardenne universe, Vincent is an angry kid: he shoplifts, watches as other boys prepare to torture a caged rat, and shuts out his mother. But he returns the tool he stole, rejects animal abuse, and reconnects with his mother.

American-born French director Eugène Green, director of La Sapienza (2014) and The Portuguese Nun (2009), brings to The Son of Joseph his characteristic compositional precision, an appreciation for Baroque art and music, and a distinctive way of filming conversations.

Green is clearly not interested in standard psychological realism or the mumbling delivery and the improvisation we see in some American indie films. Instead, he strives for the understated and precise acting we see in the work of Bresson or Akerman. Green’s actors deliver dialogue, whether arch or sincere, with perfect diction, often while looking directly into the camera. Green also opts for sparse, often symmetrical, compositions, and he usually dispenses with camera movement. Each shot renders the character’s line of dialogue in toto. “Simple things are, for me, strongest,” he said in 2015.

The static shots and direct address are never boring. One never tires of Green’s actors and Paris looks stunning here. Interiors are sparsely decorated and beautifully lit; exteriors typically consist of characters strolling through the Palais Royale or the Luxembourg Gardens. Moreover, Green insists upon the power of art: Caravaggio’s Sacrifice of Isaac and Georges de la Tour’s Joseph the Carpenter figure prominently here, as does an extraordinary singing performance in a church.

The film’s rigorous design does not prevent it from exuding hope and a touching sincerity. The concluding scene on the beach in Normandy retains the film’s minimalist design and rewards viewers who remember Au hasard, Balthazar, but also suggests the formation of a new family and the redeeming power of love.

Upcoming U.S. releases: Sony Pictures Classics has slated Elle for 11 November. Kino Lorber will release The Son of Joseph on 12 January, while Personal Shopper (IFC Films) is scheduled for 10 March. Chocolat does not yet have a U.S. distributor.

Charlie Michael traces the critical response to Intouchables in “Interpreting Intouchables: Competing Transnationalisms in Contemporary French Cinema,” SubStance 133, Vol. 43, no. 1 (2014), 123-137.

Eugène Green’s remarks about simple things comes from his Film Comment interview on La Sapienza. David has written entries on Green’s compass-point editing here and here.

The Son of Joseph (Eugène Green, 2016).