Archive for the 'Directors: Griffith' Category

Between you, me, and the bedpost

Imitation of Life.

DB here:

I do not like finding phallic symbols in movies.

I grant you that there are some films that deliberately evoke the love wand: Tex Avery cartoons, Frank Tashlin and Jerry Lewis movies. Surely the Wolf in Avery’s Red Hot Riding Hood (1943) has more than a Platonic interest in Red’s stage show.

But some critics/ academics look way too hard. For them, as a literature professor of mine put it back in the mid-1960s, phallic symbols are everywhere in art. And I learned fast that he meant everywhere, from the Odyssey to Emily Dickinson. I changed sections.

Films, of course, are full of images that encourage the hunt for avatars of the skin flute. So for forty years, I’ve argued against interpretations of a scene that depend on reading you-know-what into anything that resembles a pole, post, or pylon—any vaguely tubular shape, slender or squat, organic or mechanical. It is a duffer’s mistake to think that film shots including swords, logs, telephone poles, pine trees, skyscrapers, Greek columns, fountain pens, picket fences, shovels, rocket ships, and Pontiac fins always pay homage to the trouser snake.

Except, I must admit, bedposts.

I don’t think I’ve ever slept in a bed with bedposts, not even in those cozy B & Bs that smother you with affection and sugar-sprinkled muffins. But the American cinema likes bedposts. Red-blooded American women in classic movies often have beds braced or decorated with bedposts.

Sometimes those bedposts do some alarming things.

Exhibit A: Start, as we often do (but probably shouldn’t), with D. W. Griffith. In The Birth of a Nation, Elsie Stoneman has just spent a romantic afternoon with Ben Cameron, aka The Little Colonel.

She races into her bedroom, obviously smitten.

What does she do? She hops to the bed and leans dreamily against the fancy tapering bedpost. Now Griffith gives us the closest image of her that we’ve seen so far in the movie.

And since Griffith never passes up a chance to crosscut between anything and anything else, we get another shot of Ben, perhaps looking off toward Elsie’s house. (We have to say perhaps because Griffith is not terribly concerned with consistent eyelines.) It operates as a typical Griffith signal that one character is thinking about another.

And as if aware that Ben is thinking of her, Elsie rewards her bedpost accordingly.

Should you doubt that these bedpost calisthenics are connected with the thought of a guy, I submit Exhibit B. In Bringing Up Baby, Susan Vance (Katharine Hepburn) is taken with David Huxley (Cary Grant). While he showers, she wraps herself around the only thing in the room taller than she is.

One can easily see why a glimpse of Cary Grant stepping out of the shower could make somebody clutch a support , but wouldn’t a chair have done as well?

Exhibit C: Douglas Sirk has done interesting bedpost work in Imitiation of Life (surmounting this entry), but surely his triumph is Magnificent Obsession (1954). A blind Helen Phillips (Jane Wyman) has just learned that no operation is likely to recover her sight. Helen rises from her chair, and we hear a wordless choir along with a piano theme evocative of Rob (Rock Hudson), the mysterious man in her life. As if drawn by magnetism, she makes her way through the darkness to a totemic mass, sort of Elsie Stoneman’s bedpost on Viagra. She moves with the solemnity of a priestess paying homage to an angry god.

Actually, this thing isn’t exactly a bedpost; it’s a strange thrusting protrusion from a love seat that functions as a room divider. But it’s clearly in the bedpost tradition—as we see when, like Elsie, Helen embraces it and leans her head against it.

Soon Rob enters, framed by the post, and in no time the couple are in a clinch.

If forced to interpret these items, I’d probably say that Griffith may have included The Bedpost in a moment of frank eroticism, Hawks knew the cliché and exploited it for an actor’s bit of business, and Sirk, sophisticated Euro émigré, used it ironically. But of course these interpretations are open to dispute. I expect someone to start a dissertation on the matter immediately.

I don’t know of comparable scenes in which men, thinking of women, hug bedposts or crawl into big cavities. Bedpost worship can obviously be interpreted as another sign of Hollywood’s bias toward patriarchal values. But its blatancy and more or less witting silliness also respond to that quality that delighted Parker Tyler about Hollywood movies—the way that flagrant symbolism is flung onto the screen but toyed with, to tease us. For Tyler, the “only indubitable reading of a given movie” was

its value as a charade, a fluid guessing game where the only “winning answer” was not the right one but any amusingly relevant and suggestive one: an answer which led to interesting speculations about society, about mankind’s perennial, profuse, and typically serio-comic ability to deceive itself.

Sometimes, then, a bedpost is just a bedpost. But probably not in the movies.

The quotation comes from Parker Tyler’s Three Faces of the Film, rev. ed. (South Brunswick, NJ: Barnes, 1967), 11.

My frame enlargements from a 16mm print of Magnificent Obsession aren’t good enough in the scene I mentioned, so I’ve been obliged to draw my images from the Criterion DVD. That version crops the frame to 2.0:1, which has seemed too radical for many observers, me included. Should it instead be 1.66 or 1.85? The aspect-ratio debate has played out in extensive detail here and here.

Thanks to Lea Jacobs and Jeff Smith for some DVD loans. Jeff also encouraged me to keep this discussion in good taste.

Queen Christina.

Back in Bologna

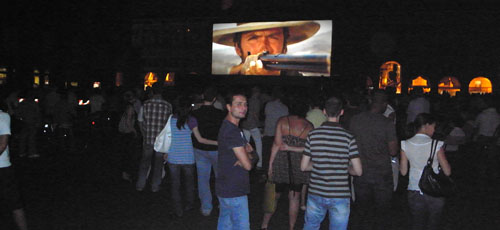

The newly restored version of The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly on the Piazza Maggiore.

Kristin here-

This year, the main complaint about Il Cinema Ritrovato, the annual festival held by the Cineteca Bologna, is that there’s too much to see. With three venues playing films against each other, plus the 10 pm screenings each evening in the Piazza Maggiore, there’s no way to see everything. Some people complain that the conflicts are becoming worse-but I remember these same complaints about the over-abundance of films coming in previous years as well. Yes, it’s frustrating at times, but being offered more films than one can watch is a problem a lot of people would love to have. Basically one either chooses a couple of threads to follow through or just goes to whatever appeals in any given time slot.

According to the 2009 festival’s newsletter, there were 810 attendees, including 557 from outside Italy.

This year there have been several main focuses: a retrospective of Frank Capra’s silent and early sound films; a portion of the Cinémathèque de Toulouse’s program of Jewish-themed Russian and Soviet cinema from the 1910s to the late 1940s; a selection of color films from the early years of the twentieth century to the 1960s; a survey of the work of Vittorio Cottafavi; the annual “100 years” program, this time from 1909; the sea films of Jean Epstein; the silent Maciste films; and many other items.

Even between the two of us, we could not take in nearly all of the riches on offer, so here’s some of what I managed to see, with David’s report to follow.

An annual hundredth birthday

Each year the festival has a thread of programs of films from one hundred years earlier. This tradition started in 2003, when Tom Gunning was asked to put together groups of films from 1903. Thereafter Mariann Lewinsky took over as programmer for these threads. In recent years, her choices have been supplemented by small groups of films chosen by individual national film archives. This year Tom programmed the 1909 Griffiths and a group of other U. S. titles.

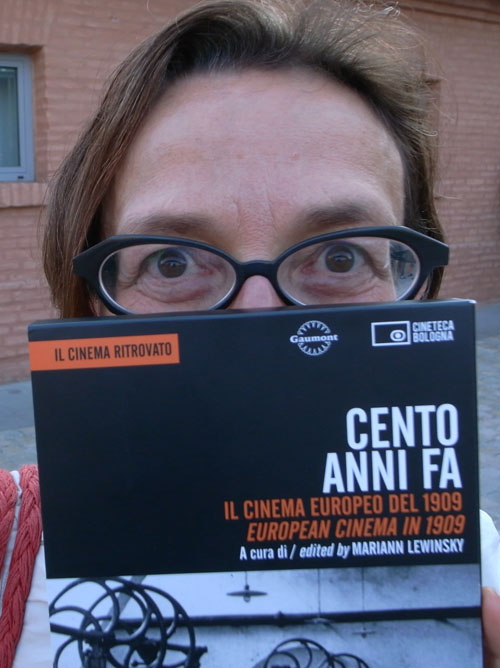

Maybe it’s just my impression, but the hundred-year packages seem to gain in prominence and popularity each year. Presumably in response to such popularity, the festival has just released a DVD with a selection of 22 shorts from this year’s 1909 program: Cento anni fa: Il cinema Europeo del 1909/European cinema in 1909 (running two hours and twenty minutes and presented below by Mariann). It contains only about a fifth of the roughly 100 films screened, but many of the others are available in online archives. DVDs of previous years’ programs are in the works, with 1907 soon to come. The DVD and other publications of the festival are available here.

I managed to see most of the 1909 programs but obviously can mention only a sampling. Undoubtedly the highlight for me and others I talked to was Albert Capellani’s L’Assommoir, notable for its skillful and intricate staging and splendid performances. It looked more like a film from 1912 or 1913. During the comedy, Un chien jaloux (a Gaumont one-reeler by an unknown director, left), pianist Donald Sosin had the audience in stitches by providing barks, whines, and growls as appropriate. (It’s included on the DVD, alas, without the sound effects.)

highlight for me and others I talked to was Albert Capellani’s L’Assommoir, notable for its skillful and intricate staging and splendid performances. It looked more like a film from 1912 or 1913. During the comedy, Un chien jaloux (a Gaumont one-reeler by an unknown director, left), pianist Donald Sosin had the audience in stitches by providing barks, whines, and growls as appropriate. (It’s included on the DVD, alas, without the sound effects.)

French director Alfred Machin contributed two excellent dramatic films, both involving windmills: Le Moulin maudit (also on the DVD) and, in the program of early color films, L’Ame des moulins. Comedy stars were represented by two Cretinetti films and a strange Max Linder film in which he becomes Amoreux de la femme à barbe (“Infatuated with the Bearded Lady”).

There were a great many documentaries giving glimpses into the world of 1909. Airplanes were much in  evidence, as were detailed depictions of industries in colonized countries. Mariann confessed herself to be fascinated by the random, unplanned events that intrude into both non-fiction and fiction films of this early period-particularly those shot in the street. As usual with early films, passers-by frequently come to a standstill and gawk at the camera. As she pointed out, the frequent intrusion of dogs into the frame reflected the reality of the time, when numerous homeless animals inhabited cities. We all became very aware of these animals, which David dubbed “Lewinsky dogs.” At the right, a little one that half-enters the end of one shot of a typical chase film, Les tribulations d’un charcutier (director unknown; also on the DVD).

evidence, as were detailed depictions of industries in colonized countries. Mariann confessed herself to be fascinated by the random, unplanned events that intrude into both non-fiction and fiction films of this early period-particularly those shot in the street. As usual with early films, passers-by frequently come to a standstill and gawk at the camera. As she pointed out, the frequent intrusion of dogs into the frame reflected the reality of the time, when numerous homeless animals inhabited cities. We all became very aware of these animals, which David dubbed “Lewinsky dogs.” At the right, a little one that half-enters the end of one shot of a typical chase film, Les tribulations d’un charcutier (director unknown; also on the DVD).

Mariann watched a great number of 1909 films in order to make her selection. Her experience convinced her of what many of us feel, that this was a turning point for the development of film art, though perhaps not as dramatic a one as 1913. Apart from L’Assommoir, Griffith’s The Country Doctor could be pointed to as evidence that the year saw films of a greater complexity and beauty than had previously been released. Griffith may no longer be quite the lone giant of the pre-1920 era that film historians have portrayed. Still, there are touches in The Country Doctor that no other director could have conceived, such as the early shot of the central family strolling through a field of tall grass that hides everything except the doctor’s top hat floating above the stalks.

Reaching 1909 raises the question as to how long these 100-year anniversary programs can continue and what form they should take. With fiction films getting longer in years to come, particularly in Europe, there emerges a problem of including enough of them to give a sense of a single year without having the programs expand even more. Perhaps non-fiction films will figure as an increasing proportion of this thread-with more Lewinsky dogs inadvertently captured for posterity.

A garland of color films

Two programs of early color films demonstrated the various processes: hand-coloring with stencils, tinting, toning, and attempts at photographic color. The only really successful of the latter were two 1912 shorts using the Gaumont system, which provided images in sharp, reasonably true color.

I caught only a few of the features in the color thread. Victor Schertzinger’s Redskin (1929), in two-strip Technicolor, was a beautiful print. Despite its implausibly happy ending, this story was a sophisticated look not only at racial tensions between whites and Indians but also at equally divisive tensions among Indian tribes. Like the other occasional films of the early decades that show the action from the Indians’ standpoint (Griffith’s The Red Man’s View figured in the 1909 program) are remarkably sympathetic to their culture. The color portrays not only the beautiful desert landscapes of the American Southwest but also Navaho blankets and Pueblo sand paintings.

Toward the end of the week, when people asked me what my favorites had been so far, I forgot to mention Pandora and the Flying Dutchman, which had played way back on the opening Saturday. It has a reputation as a bizarre film, and I wasn’t expecting much beyond some glowing color images of two beautiful stars, Ava Gardner and James Mason. But I was pleasantly surprised by its well-handled fantasy tale of the Flying Dutchman visiting a contemporary Spanish seaside resort and finding his true love. In particular a lengthy flashback to the Dutchman’s original crime has a degree of stylization and intensity that allow it to avoid seeming absurd. The tale has an other-worldly quality that recalls some of Powell and Pressburger’s films-enhanced by the presence of cinematographer Jack Cardiff handling the Technicolor.

Unfortunately Track of the Cat (William A. Wellman, 1954) failed to similarly avoid a sense of the absurd in its overheated Tennessee William pastiche set on an isolated farm in the West. Lumbering dialogue lays out explicitly all the tensions among the members of the central family, exacerbated by the depredations of an elusive puma and a visit by the younger brother’s potential fiancée. The reason for its presence in the festival, though, was its color scheme. Wellman set out to make a “black and white film in color,” as the program describes it. Both the snowy landscapes and the interiors are dominated by white, black, and flesh tones, with the sole exception-the Robert Mitchum character’s bright red coat-disappearing from the action partway through.

Not only silents need restoring

Martin Scorsese’s influence hovers over the festival and the Cineteca Bologna. One of the two screening rooms in the Cineteca’s building is the Scorsese (the other being the Mastroianni). In recent years, films from the institution that Scorsese founded, the World Film Foundation, have been screened here. The WFF is dedicated to restoring and preserving films from countries whose archives might lack the resources to handle such major projects. This year’s presentations were Fred Zinnemann and Emilio Gómez Muriel’s Redes (The Wave, 1936), Shadi Abdel Salam’s Al Momia (known in English as The Night of Counting the Years, 1969), and Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day (1991). The foundation also aided in the editing of Ingmar Bergman’s home movies into Images from the Playground (Stig Borkman, 2009).

I had seen The Night of Counting the Years in one of the faded 16mm copies that have long been the only form in which this Egyptian classic was available. The new copy is a vast improvement, finally revealing why this is considered perhaps the great Egyptian film. It is based around a true story from 1881, when a powerful tribe on the west bank at Luxor discovered a cave containing a huge cache of royal mummies and funerary goods that had been hidden away by ancient priests to preserve them after the extensive robbing of their original tombs. The tribe started selling items gradually on the illicit antiquities market, but one of its members revealed the location of the cache to the authorities, allowing them to salvage most of the mummies and their grave goods. The film was beautifully shot on location in the desert and temples of the west bank and provides a meditation on why the young man might have acted against the apparent best interests of himself and his family.

A 1991 Edward Yang film might not seem an obvious candidate for restoration, yet the complete version of A Brighter Summer Day was barely rescued from oblivion. The original negative does not exist, and the print materials on the shorter version were discovered to be moldy. Rescuing these and combining footage from both versions has resulted in a pristine new print of Yang’s greatest achievement. An in-depth look at Taiwanese society a decade after Chiang Kai-chek took over the island, it follows a middle-class boy drawn gradually into gang violence. The new version, which premiered at Cannes earlier this year, looked great on the big screen in the Arlecchino.

This and that

A brief tribute to Harry d’Abbadie d’Arrast included Laughter, the director’s first sound film. A romantic comedy, it stars Frederick March as a witty young composer aspiring to marry a wealthy society woman against her father’s wishes. The film has touches of Holiday and Design for Living, both films yet to be made. Laughter confirms d’Abbadie Arrast’s reputation as a good but lesser filmmaker in the Lubitsch mold.

We all have reason to celebrate the fact that Georges Méliès’ films went into the European public domain this year. (The films have long been in the public domain in the U.S.) With obstacles to programming out of the way, the festival presented a program in homage, featuring twenty shorts presented by Serge Bromberg, who helped put together the extensive Méliès collection that came out in the U.S. and won the 2008 award for best DVD set here at the Cinema Ritrovato. (It came out in France earlier this year.) While all the films shown are on the DVDs, it was a treat to see them on the big screen. Bromberg provided a lively, if not entirely authentic, running commentary to “explain” the action of the final film, La Fée Carabosse.

We all have reason to celebrate the fact that Georges Méliès’ films went into the European public domain this year. (The films have long been in the public domain in the U.S.) With obstacles to programming out of the way, the festival presented a program in homage, featuring twenty shorts presented by Serge Bromberg, who helped put together the extensive Méliès collection that came out in the U.S. and won the 2008 award for best DVD set here at the Cinema Ritrovato. (It came out in France earlier this year.) While all the films shown are on the DVDs, it was a treat to see them on the big screen. Bromberg provided a lively, if not entirely authentic, running commentary to “explain” the action of the final film, La Fée Carabosse.

Demonstrating that history repeats itself, Belgian film scholar Eric De Kuyper programmed a selection of titles dealing with financial speculation and crisis. These included perhaps the best of several items from Louis Feuillade shown during the week, Le Trust ou les batailles de l’argent (1911). It stars René Navarre, who would soon play Fantômas, as an unscrupulous detective, and the action is more in the thriller mode than a serious depiction of French finances. Also included was a 1916 German feature, Die Börsenkönigin (“The Queen of the Stock Exchange”), with a fine performance by Asta Nielsen as a woman more successful in finance than in love.

More to come from David, on Capra, DVD awards, and personalities glimpsed by a roving camera.

For our previous Cinema Ritrovato entries, see here for 2008 and here, here, and here for 2007. For a thorough discussion of dogs in early film, with comments by Mariann Lewinsky, see Luke McKernan‘s authoritative entry here. On the occasion of Edward Yang’s death in 2007, David offered an homage to him and A Brighter Summer Day here.

Bugs: The secret history

DB here:

One of the many penalties of watching movies on TV is the prevalence of bugs.

This is the nickname adopted by media makers for those little channel logos and watermarks that hop onto your screen. Sometimes these translucent signatures surface at intervals, to minimally satisfy FCC channel identification demands. Others let you know the movie you’re watching, or will be later.

But just as often the bugs just squat in a corner forever, teasing your eye away from the movie. Bugs are to the 2000s what editing and time-compressing were to earlier eras. “Movies, uncut,” boasts the IFC bug. But not unspoiled.

Bugs are bad enough when they are hovering in a black vacuum, made forlorn by letterboxing.

But they really jump into competition when they take up part of the image. How can you watch what actors are doing when there’s something faintly readable floating up from below?

I find it impossible not to look at a bug occasionally. In dark shots, sometimes it’s the most visible thing on the screen. Even in bright shots I stare at it. Maybe I’m hoping that it will be different this time. Yet when it changes, as it does on the Lifetime channel, I watch it more attentively, which only makes me more annoyed.

It’s like the mesmeric spell of Time Code, ticking away the movie’s life, and yours.

I’m not the first to complain. An eloquent manifesto, originally called Squash the Bugs, dates back to 2000, when the infestation was starting. Several other souls participated in the movement.

We know why bugs are swarming all over TV. Somebody better dressed than you or me is worried that we will be recording A Christmas Story or Smokey and the Bandit or Stranger in My Bed. We might even try to sell copies, or post a clip online. In principle, the bug is a badge of ownership, warning that we could be prosecuted. In practice, nobody expects to sue every user, so bugs help spread the brand. It’s like putting a designer logo on a shirt, making you a walking ad. Who wouldn’t want their bug, microscopic as it is, all over YouTube (which of course tacks on its own bug)?

But like everything else that we take for granted, bugs aren’t new. In their earlier form, they’re rather likable.

Silent but deadly

Movie bugs go back to the first years of cinema, when producers were no less worried about media piracy than they are today. Between 1895 and 1915, films circulated very freely around the world, and enterprising crooks happily duped originals and passed them off as their own productions. To block this, filmmakers tried to find ways to keep their trademarks on the film.

The obvious step was to put the trademark in the intertitles, and many companies did. Here is one for For His Son, a 1912 Griffith film from American Biograph. (What did the protagonist do for his son? He created a soft drink called Dopocoke, which turns the college boy into a hopeless addict.) Note the handsome AB insignia.

But of course a pirate could simply replace such original titles with ones of his own. The next logical step was to incorporate the trademark into the images, which couldn’t be replaced. Without the technology to create near-invisible superimpositions, the filmmakers took the obvious course.

They put the company logo into the set.

The AB circle typically appeared as a wall decoration. Biograph characters loved to furnish their surroundings to highlight this motif, preferring to put it at eye level and frame center. The logo could be found in unexpected places, like movie theatres (Those Awful Hats, 1908), and it could brighten the dreariest hovel (What Shall We Do with Our Old?, 1911).

The plaque’s popularity stretched back to Civil War days (In the Border States, 1910), and even in medieval times a king might mount the stylish AB on a brick wall (The Sealed Room, 1909).

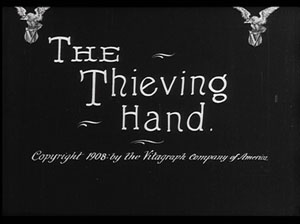

Not to be outdone, Biograph’s competitor, the Vitagraph company, had a beautiful soaring eagle logo, which conveniently furnished a striking V graphic.

Judging from the evidence of this 1908 film, however, Vitagraph had a sideline in manufacturing safes.

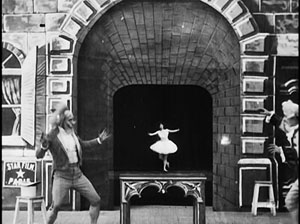

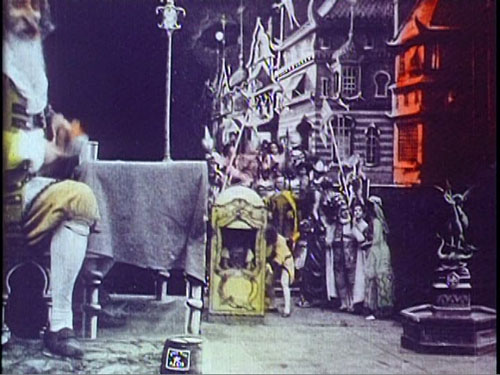

The practice of building the trademark into the mise-en-scene seems to have begun in France. Georges Méliès, whose fantasy films were popular around the world, took measures to counter piracy early. You can see his Star-Film logo on the building stone in the left corner of this frame from La Danseuse microscopique (1902). Shift it to the right corner and we’d have a modern-day bug.

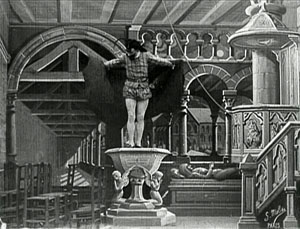

At the very top of this entry is a frame from Le Voyage de Gulliver à Lilliput et chez les géants (1902). There Méliès attached the Star-Film seal to the barrel sitting just left of center.

At the very top of this entry is a frame from Le Voyage de Gulliver à Lilliput et chez les géants (1902). There Méliès attached the Star-Film seal to the barrel sitting just left of center.

But Méliès didn’t always shove his imprimatur to the edge of the frame. In Le Tonnerre de Jupiter (1903) it sits just below the eagle that Zeus bestrides.

In the earlier Diable au convent (1899), Méliès exercised another option, simply signing his image as if it were a painting. To a large extent, it was.

Léon Gaumont had two marques, each enclosed in a chrysanthemum ring. The most famous one is a majestic Gaumont, but an alternative, ELGE (that is, LG), haunts Alice Guy’s Billet de banque (1907). First, in a café, the logo is attached to a table, and later it’s a decorative baseboard in a police station.

In Guy’s Le Frotteur (1907), Gaumont simiply stuck its logo to a chair leg.

Then there’s the Pathé Frères rooster.

Easy enough to embed that, you’d think. Just have a rooster stroll through a shot now and then—not only barnyard scenes, but ones set in a courtroom or a factory. Still, roosters are pretty accessible to any film pirate, so Pathé went the more ordinary route of weaving its logo into the set.

An insistent example comes in The Physician of the Castle (1907), possibly the source for Griffith’s The Lonely Villa (1908) and Lois Weber/ Phillips Smalley’s Suspense (1913). The plot is sort of a 1907 Panic Room. The logo is initially a plaque in the parlor of the castle, visible just behind the kneeling doctor.

An identical plaque is perched in nearly the same spot on the wall of the doctor’s own parlor, as we can tell when his family is besieged by the invading tramps.

The tramps pass through another room, where the trademark stands proudly on another wall, on screen right.

And when the wife tries to phone the husband for help, we get an insert that shows the Pathé cock nearly perched on her shoulder.

Why do I find the old bugs charming and the new ones annoying? I suppose it’s partly because the old ones were hand-crafted, not the result of keyboard twiddling. They are tangible. They are part of the scene’s space. Hard to see on DVD, the embedded marques are striking in 35mm projection, and spotting them is part of the pleasure of early film. Moreover, the filmmakers intended them to be there, or at least they accepted the need for them. But what director today is happy when the Sundance bug creeps into her compositions?

The old bugs seem to have gone extinct around 1912, but they will cling to their films. They bear witness to filmmaking of a specific time, and they anticipate problems that persist today. In tackling the threat of piracy, the old bugs seem at once naïve and intelligent. I see them as a rational solution to a hard problem, narrative consistency be damned. Today’s bugs, floating on top of the story world, seem more like corporate tattoos or graffiti. They don’t exist within the action, so you could argue that they are less disruptive. But they become a different sort of distraction, hovering halfway between the story world and the space of viewing. Bugs are spectres haunting the film.

On rare occasions, a modern add-on can be appropriate. In a Méliès film on the recent Flicker Alley set, L’Oracle de Delphes (1903), some TV agency has clapped its own digital bug into the lower right corner. It really is about beetle-size, and it dares to be a single eye looking back at you. That icon adds a touch of peculiarity not out of keeping with the Méliès aesthetic.

You can argue that this smirch on the image is a minor sacrilege. But I suspect that the Master of Montreuil would have grinned in approval.

For more on bugs, aka DOGS (Digital Onscreen Graphics), see Wikipedia. Thanks to Jason Mittell for helping me name these pests. And all hail Turner Classic Movies for keeping its bugs to a minimum.

The Sunbeam (Griffith, American Biograph, 1912).

PS 19 January 2009: “Subliminal” bugs: I had hoped to include a frame illustrating the anti-piracy stamp used on current 35mm releases, but couldn’t find one quickly. This mark consists of a tight pattern of dots resembling a character in Braille. The stamp would presumably be copied if someone shot off the screen or ran the film through a telecine. How effective these bugs are at tracing pirate copies I can’t say, but you can detect them, especially in bright scenes; I usually notice one every third reel or so, just left of the center of the frame. I’ll keep looking for a frame and try to add one to this entry.

John Powers alerted me to the fact that even Michael Snow’s Région Centrale got the bug treatment when it was telecast on Italy’s RAI 3 TV. Thanks to John for this scary example.

P.P.S. 24 January 2009: On the Internets, ask and ye shall receive. Olli Sulopuisto wrote to link me to the Wikipedia entry explaining the domino dots, known as CAPs. The entry includes an illustration. Olli also contributed to Jim Emerson‘s scanners blog, which contains good commentary on CAPs from Jim and his readers.

P.P.P.S. 29 May 2013: Can anti-piracy bugs be integrated into the movie or TV show? Yes!

The ten best films of . . . 1918

Kristin here–

We ended 2007 with a salute to the 90th anniversary of the solidification of the classical Hollywood filmmaking system. 1917 was not only the year when all the guidelines—continuity editing, three-point lighting, and unified story structure—gelled in American cinema. It was also one of those years (like 1913, 1927, and 1939) when a burst of creativity took place internationally. For those years, it’s hard to keep one’s greats list to ten.

Enough of you enjoyed that entry that we thought we would come up with another list to end 2008. For some reason, 1918 doesn’t yield the plethora of great films that obviously should go on such a list. Maybe it’s the sheer accident of preservation. After a string of masterpieces from Douglas Fairbanks in 1917, there seems to be a dearth of his films extant from the following year. Some filmmakers, like Cecil B. De Mille, simply released fewer films in 1918. And of course, some masterpieces may still lie gathering dust on archive shelves, waiting to be discovered.

Still, great films were made that year, some familiar—some that should be better known. Some are available on DVD, and some are excellent candidates for release by some of the enterprising companies like Kino International, Image Entertainment, and Flicker Alley.

1. The list isn’t in rank order, but for me the outstanding film of 1918 is Berg-Ejvind och hans hustru, better known to most as The Outlaw and His Wife, by Victor Sjöström. This tale of an enduring love between a man  hunted by the police and a rich landowner who falls in love with him, and, as one title says, “Hearth and home and every man’s respect—she gave it all up for his sake.” The result is one of the cinema’s great romances as the pair flees to the mountains and spend the rest of their lives amidst the natural landscapes that create spectacular backdrops for the action.

hunted by the police and a rich landowner who falls in love with him, and, as one title says, “Hearth and home and every man’s respect—she gave it all up for his sake.” The result is one of the cinema’s great romances as the pair flees to the mountains and spend the rest of their lives amidst the natural landscapes that create spectacular backdrops for the action.

This year Kino also brought out a disc with the dynamite double bill of two tragedies Ingeborg Holm (1913) and Terje Vigen (1916). David and I have both written about the staging in Ingeborg Holm, and David has had much to say on tableau staging in 1910s cinema. Watch these three films, and you will understand why we consider Sjöström perhaps the great director of the decade. It’s a shame that more of his films are not available yet in the U.S. Buy copies of these, and maybe Kino will bring more of them out.

2. Another master of this era, Louis Feuillade, made a sequel to his Judex (1916): La Nouvelle Mission de Judex. David discusses both in the second chapter of his Figures Traced in Light. Although Judex is available on DVD, so far the second serial is not.

3. I suspect that Hearts of the World is one of those D. W. Griffith features that a lot of film enthusiasts have heard of but not seen. Remarkably, it’s not available on DVD. (Keep your old laserdisc if you’ve got one!) I have to admit, it’s not one of my favorite Griffiths, though it does have a charming performance by Dorothy Gish and contains scenes that were actually shot near the front lines in France.

4. Ernst Lubitsch was making the transition from shorts to features in 1917 and 1918. While Carmen is historically important for his development toward his mature style, most audiences these days would probably find Ich möchte kein Mann sein (“I don’t want to be a man”) more entertaining. It’s a comedy about an independent young lady who escapes her strict governess and guardian by going out on the town disguised as a man—in the process joining her guardian without his recognizing her (see the frame at the bottom). Its star, Ossi Oswalda, was an outgoing blonde dynamo, quite different from Pola Negri, whom Lubitsch turned to for his later historical epics.

Kino has made several of Lubitsch’s films from the late 1910s and early 1920s available. Ich möchte kein Mann sein can be bought on a single disc with Die Austerinprinzessin (“The Oyster Princess,” 1919), another Oswalda comedy. I’d recommend getting it as part of the larger “Lubitsch in Berlin” set, which also includes the hilariously imaginative Die Puppe (“The Doll,” 1919), the Expressionist satire Die Bergkatze (“The Wildcat,” with Negri in her one comic role for Lubitsch, 1921), an Arabian-nights epic Sumurun (1920), and the historical epic Anna Boleyn (1921), as well as a documentary on Lubitsch.

5. In 1918 Cecil B. De Mille made a film that would change his career’s trajectory: Old Wives for New. At the  time, this romantic drama that seemed risqué in its casual depiction of adultery, golddiggers, and especially divorce as creating a happy outcome. Up to that point De Mille had been working in a whole range of genres, creating imaginative films that helped define the classical style. The success of Old Wives for New led him to specialize in spicy romances known for their haute couture costumes. The film is available on a disc from Image that includes De Mille’s other major film of 1918, The Whispering Chorus.

time, this romantic drama that seemed risqué in its casual depiction of adultery, golddiggers, and especially divorce as creating a happy outcome. Up to that point De Mille had been working in a whole range of genres, creating imaginative films that helped define the classical style. The success of Old Wives for New led him to specialize in spicy romances known for their haute couture costumes. The film is available on a disc from Image that includes De Mille’s other major film of 1918, The Whispering Chorus.

6. Hell Bent, by John Ford, was long thought to be among his many lost westerns from the early years of his career. It was rediscovered in the Czechoslovakian archive and shown years ago in Pordenone at the Il Giornate del Cinema Muto festival. I must confess that I don’t remember it very well, apart from one spectacular tilt downwards as a stagecoach (?) races down a winding mountain road. Not as good as Straight Shooting, and Hell Bent survives in rocky shape (perhaps too much so for DVD release), but Ford films of this era are so rare that I’ve listed this one.

7. Like Lubitsch, in the late 1910s Charlie Chaplin was making a gradual transition from shorts to features. In 1916 and 1917 he released a remarkable string of Mutual two-reelers, from The Rink (December 1916) to The Adventurer (October 1917). In 1918, with A Dog’s Life and Shoulder Arms, he increased the films’ length to three reels, or roughly 45 minutes, and started releasing through First National. He also cut back on the number of titles released each year. Apart from a brief promotional film for war bonds, A Dog’s Life and Shoulder Arms were his only 1918 releases. Which is better? I suppose most people would say Shoulder Arms. To me it’s a toss-up.

8. David and I started attending Il Giornate del Cinema Muto in 1986, when the festival was launching its great series of national retrospectives. In quick succession, these retrospectives revealed three hitherto virtually unknown but major auteurs of the 1910s: the Swede, Georg af Klercker, in 1986; the Russian, Evgeni Bauer, in 1989; and the German Franz Hofer, in 1990. Bauer’s career ended with his death in 1917. Hofer remained active until the early 1930s. The Giornate’s German program contained only six of his films, however, and those from the 1913-1915 period. I suspect that means the later teens titles are lost.

In contrast, nearly all of af Klercker’s films survive, mostly in the original negatives. The prints shown at Pordenone were stunning. The director had a great eye for settings, using beaded curtains, mirrors, and other elements to considerable effect. He made three films in 1918: Fyrvaktarens dotter, Nobelpristagaren,Nattliga toner, the first two of which were shown in the 1986 retrospective.

Unfortunately since then the films have not been made widely available, either in prints or on DVD. Having not seen the two titles just mentioned since 1986, I can’t say that I remember them well enough to judge between them. So I’ll just leave all three films here, along with the advice to seize any chance you may get to see those or af Klercker’s other films.

(Given how little known af Klercker’s work is outside Sweden, I should point out a major English-language piece on the director’s style, Astrid Söderbergh Widding’s “Towards Classical Narration? Georg af Klercker in Context,” in editors John Fullerton and Jan Olsson’s Nordic Explorations: Film Before 1930 [Sydney: John Libbey, 1999].)

9. Stella Maris, directed by Marshall Neilan, was the first of five features Mary Pickford starred in in 1918. Its reputation lies mainly in the fact that Pickford played a double role, the bed-bound but lovely title character, and an ugly, slightly deformed orphan. In its outline, the story sounds abstract and overly symmetrical. Stella Maris’s relatives shut her off from all ugliness in the world, keeping her in happy innocence well into her teens. Unity, the orphan, has known nothing but deprivation. As Stella comes to glimpse the grim side of life, Unity is adopted and has glimpses of the beauties enjoyed by the rich. Both become miserable as a result.

The overall implication is pretty grim. Stella’s world is initially wonderful only because everyone lies to her. She becomes embittered when she finally discovers this. At the heart of the tale is the deception that life is beautiful. Unity, who has not been deceived, knows better from the start. Even one brief reference to the war, as a troupe of soldiers passes by the estate where Stella lives, makes it seem tragic—this in a film that came out about two months after the U.S. had entered World War I.

The balance between the two characters is made less artificial than it might sound by Pickford’s extraordinary performance—not so much as Stella, who is a rather passive version of the typical Pickford persona, but as Unity. The waif’s frequent disappointments and outright suffering create a strong effect that shadows even the quasi-happy ending. It’s a beautifully made film as well, with the use of glamorous backlight (as in the image at the top of this entry). Stella Maris is available on DVD from Image.

10. I have been hard put to find a feature to round out the list, so I’m substituting a group of shorts. They’re not masterpieces by any means, but each displays the talents of a great silent comic well on the way toward his most fruitful period.

There’s no single great film to mark Harold Lloyd’s transition, but during 1918 he was developing his “glasses” character. He had had a modest success with his “Lonesome Luke” series from 1915 to 1917, where he essentially created a variant of Chaplin. In September, 1917, Lloyd first wore his famous black, lens-less glasses in Over the Fence. His early one-reelers wearing those glasses were still sheer slapstick, with little of the characterization that he would later develop to go with his new look. Arguably it was 1919 or even 1920 before he had fully nailed that persona. Still, during 1918 one can see him groping toward the formula.

Kino’s “The Harold Lloyd Collection” volumes contain four films from that year, all co-starring Lloyd’s  regular co-stars, Snub Pollard and Bebe Daniels. The Non Stop Kid (the title on the film; filmographies mistakenly give it as The Non-Stop Kid; May 21), Two-Gun Gussie (May 19), The City Slicker (June 2, all three on volume 2), and Are Crooks Dishonest? (June 23, on volume 1). The development clearly came in fits and starts. Two-Gun Gussie and Are Crooks Dishonest? are both slapstick affairs involving tricks and mistaken identify. The Non Stop Kid, though, has Lloyd in a more familiar situation, using his wits to foil a crowd of suitors and win the heroine’s hand. The City Slicker has a similar feel to it, though unfortunately the end is missing. The Non Stop Kid also has Lloyd donning a disguise in the form of a false moustache that somewhat resembles the one he had worn as Luke. This scene has a startling effect, blending the glasses character and the Luke character.

regular co-stars, Snub Pollard and Bebe Daniels. The Non Stop Kid (the title on the film; filmographies mistakenly give it as The Non-Stop Kid; May 21), Two-Gun Gussie (May 19), The City Slicker (June 2, all three on volume 2), and Are Crooks Dishonest? (June 23, on volume 1). The development clearly came in fits and starts. Two-Gun Gussie and Are Crooks Dishonest? are both slapstick affairs involving tricks and mistaken identify. The Non Stop Kid, though, has Lloyd in a more familiar situation, using his wits to foil a crowd of suitors and win the heroine’s hand. The City Slicker has a similar feel to it, though unfortunately the end is missing. The Non Stop Kid also has Lloyd donning a disguise in the form of a false moustache that somewhat resembles the one he had worn as Luke. This scene has a startling effect, blending the glasses character and the Luke character.

1917 and 1918 formed the high point of the string of comic shorts directed by Fatty Arbuckle, in which he also co-starred with Buster Keaton and Al St. John. When Keaton went solo, he proved to be a far better director than Arbuckle. Arbuckle tended to simply face his camera perpendicularly toward the back of the set for every shot, just cutting to whatever scale of framing would best display a gag. Here it’s the perfectly timed and executed gags that dazzle, and the films are often hilarious. In 1918, the team made The Bell Boy, Moonshine, Out West, Good Night Nurse, and The Cook. The latter shows off Arbuckle and Keaton’s dexterity at juggling props and Fatty’s surprising grace, as when he improvises a Salome dance with a head of lettuce standing in for that of John the Baptist!

The 13 surviving Arbuckle-Keaton films (some with missing bits) are available on Eureka’s definitive boxed set, “Buster Keaton: The Complete Short Films.” (That’s Region 2 format only, and available from Amazon UK.) Image’s “The Best Arbuckle Keaton Collection” has 12 films, missing only the more recently rediscovered The Cook. Image brought out The Cook on a disc with Arbuckle’s A Reckless Romeo (1917, sans Keaton). Kino’s two separately available volumes of “Arbuckle & Keaton” (here and here) contain 10 shorts total, again missing The Cook.

Apart from all these films, it’s worth noting that in the world of animation, 1918 saw the release of Winsor McCay’s fourth cartoon, The Sinking of the Lusitania, and Dave Fleischer’s first, Out of the Inkwell, which launched the enduring series.

Next year, 1919. Happy 2009 to all our readers!