Archive for the 'Directors: Griffith' Category

Lucky ’13

The Mysterious X (1913).

Each film is interlocked with so many other films. You can’t get away. Whatever you do now that you think is new was already done in 1913.

Martin Scorsese, quoted in Scorsese by Ebert (University of Chicago Press, 2008), 219.

DB here:

Most historical events don’t abide by clocks and calendars. Seldom does a trend begin neatly on one date and end, full stop, on another. Changes have vague origins and diffuse destinies. When Kristin and I, along with others, argued for 1917 as the best point to date the consolidation of the Hollywood style of storytelling, we realized that it’s a useful approximation but not as exact as a Tokyo subway timetable.

It’s just as hard to argue that a year constitutes a meaningful unit in itself. Who expects anything but tax laws to change drastically at midnight on 31 December? Yet evidently our minds need benchmarks. Film historians, while being aware that trends are slippery and dating is approximate, have long spotlighted certain years as particularly significant.

Take 1939, which has become a sort of emblem of the peak achievements of Hollywood’s Golden Age. We had Gone with the Wind, The Wizard of Oz, Only Angels Have Wings, Stagecoach, Gunga Din, Wuthering Heights, Dark Victory, Young Mr. Lincoln, Beau Geste, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Ninotchka, The Roaring ‘20s, and Destry Rides Again. I’d watch any of those, except Gone with the Wind, right now—something I find it hard to say about most Hollywood movies I’ve seen in 2008.

Another strong year is 1960, with La Dolce Vita, L’Avventura, Rocco and His Brothers, The Apartment, Elmer Gantry, Spartacus, Psycho, Exodus, The Magnificent Seven, Shadows, Late Autumn (Ozu), and The Bad Sleep Well (Kurosawa). Arguably, 1960 was owned by the French, who gave us Breathless, Shoot the Piano Player, Paris nous appartient, Les Bonnes femmes, Le Trou (Becker), Moi un noir (Rouch), and Letter from Siberia (Marker). (See Postscript.)

Let’s go back still further. Researchers sometimes split the silent-film period in two, with the first stretch, usually called “early cinema,” running up to 1915 or so. (1) The second phase then runs roughly from 1915 to 1928. (2) So for many historians the year 1915 functions as a tacit pivot-point, and it is remembered not only for The Birth of a Nation but also for Regeneration, The Tramp, Kindling, The Cheat, Les Vampires, Daydreams (Yevgenii Bauer), and several William S. Hart films. But another year holds a special place in the minds of silent film aficionados.

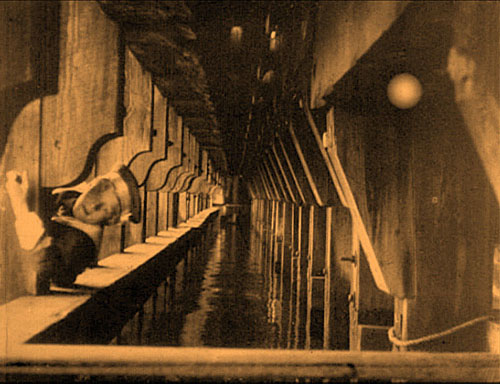

Over a decade ago, the annual Days of the Silent Cinema festival (Il Giornate del cinema muto), took 1913 as its focus. (3) It was an extraordinary year. Denmark produced Atlantis (August Blom) and The Mysterious X (Benjamin Christensen). From France we had L’Enfant de Paris (Leonce Perret), Germinal (Albert Capellani), and Louis Feuillade’s Fantomas series. Germany gave us Urban Gad’s Engelein and Filmprimadonna and Franz Hofer’s obsessively symmetrical The Black Ball. The staggering set of Italy’s Love Everlasting (Ma l’amor mio non muore!, Mario Caserini) was matched by the breadth of Enrico Guazzoni’s Quo vadis? In Russia Bauer released Twilight of a Woman’s Soul. American audiences saw Traffic in Souls (George Loane Tucker) and Death’s Marathon and The Mothering Heart, from a guy named Griffith. Several historians would argue that 1913 marked the first major achievements of film as an artform.

Two outstanding films of that annus mirabilis have recently been issued on US DVD. One is a striking accomplishment, the other a flat-out masterpiece. Both discs belong in the collections of everyone who’s serious about cinema.

Your call is important to us

A wife and her baby are alone in an isolated house when a tramp breaks in. As the wife tries to keep the invader at bay, her husband happens to telephone and learn what’s happening. He scrambles to return home. He steals an idle car, and its owner, accompanied by police, race after him. We cut rapidly between the besieged mother and the husband’s frantic drive, as he is in turn pursued. Just as the tramp is about to attack the wife, the husband bursts in, followed by the police. The family is saved.

This is the story of the 1913 one-reel film, Suspense, co-directed by Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley. If the plot sounds familiar, it’s probably because you know that one of D. W. Griffith’s most famous films, The Lonely Villa (1909) tells the same basic tale.There are still earlier versions, including one, The Physician of the Castle (Le Médécin du chateau, 1908), which may have inspired Griffith. The ultimate source seems to be a 1902 play by André de Lord, Au téléphone (translated here).

So Weber and Smalley are reviving an old idea. Their task is to make it fresh. How they do so has been studied in depth by Charlie Keil in his book Early American Cinema in Transition: Story, Style, and Filmmaking, 1907-1913.I can’t match Keil’s subtlety, and it’s better that you see the film first, so I’ll drop only some hints, pointers, and comments.

We’re inclined to say that The Lonely Villa influenced Suspense. But maybe we can capture the situation in a more illuminating way. The art historian E. H. Gombrich has suggested that we can often trace the relationship between artworks in terms of schema and revision. (4) A schema is a pattern that we find in an artwork, one that a later artist can borrow. Most often, later artists copy the schema straightforwardly. This is the usual way we think of influence. But instead of replicating the schema, the next artist can revise it. She can elaborate on it, strip it to its essence, drop parts and add others, whatever—in order to achieve new purposes or evoke fresh responses.

In The Lonely Villa, Griffith uses crosscutting to build suspense. He cuts among the thuggish vagrants trying to break in, the wife and daughters trying to hold them off, and the father learning by phone of the situation and then plunging after them with a policeman. The obvious pattern here is the principle of alternation between different lines of action, all taking place at the same time and converging in a last-minute rescue.

So Smalley and Weber inherit the crosscutting schema, but they go beyond simply copying it. They find ways to revise it, some quite surprising. These revisions aim to create more tension and to dynamize the situation.

The obvious option, at least to us today, would be to use more shots than Griffith does; we think that increasing the cutting pace builds up excitement. Interestingly, however, Suspense uses only a couple of more shots than The Lonely Villa within a comparable running time. (5) We usually expect that American films become more rapidly cut as the 1910s go on, but this isn’t the case here. Shortly, I’ll suggest why.

Smalley and Weber recast Griffith’s parallel editing in several ways. For instance, The Lonely Villa prolongs the phone conversation between husband and wife, building suspense through the husband’s instruction to use his revolver on the thugs. Suspense, by contrast, doesn’t dwell on the telephone conversation but devotes more time (and shots) to the chase along the highway. That’s because Weber and Smalley have complicated the chase by having the husband pursued by the irate motorist and the police, something that doesn’t happen in the Griffith film.

Just as important, Smalley and Weber revise the crosscutting schema through framings that are quite bold for 1913. For example, Griffith’s tramps break into the house in long shot, and they move laterally across the frame.

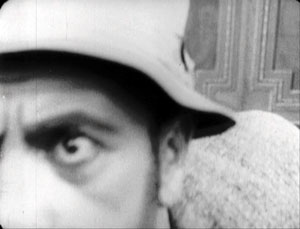

But Weber and Smalley’s tramp sneaks steadily up the stairs, into a menacing extreme close-up.

Elsewhere, Suspense gives us close views of the wife and of the door as the tramp breaks in. There are oblique angles on the back door of the house, and virtually Hitchcockian point-of-view shots when the wife sees the tramp breaking in and he looks straight up at her.

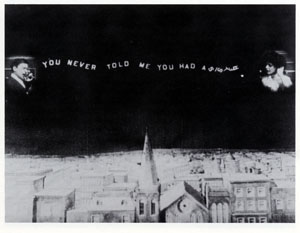

What struck me most forcibly on watching the film again was the way in which Weber and Smalley’s daring framings serve as equivalents for parallel editing. In effect, they revise the crosscutting schema by putting several actions into a single frame. The most evident, and the most famous, instances are the triangulated split-screen shots. They cram together three lines of action: the wife on the phone, the husband on the phone, and the tramp’s efforts to break into the house (here, finding the key under the mat). (6)

Split-screen effects like this were common enough in early cinema, especially for rendering telephone conversations. Eileen Bowser points out that the three-frame division was one variant, with a landscape separating the two callers. (7) Her example is from College Chums (1907).

But my sense is that in early cinema the split-screen effect was used principally for exposition or comedy, not for suspense. Smalley and Weber have made this framing substitute for crosscutting: instead of giving us three shots, we get one, showing the plot advancing along different lines of action. These splintered frames function much like Brian De Palma’s multiple-frame imagery in Sisters, Blow-Out, and other films. There’s also the nice touch of the conical lampshade over the husband’s head, providing a fulcrum for the composition.

Earlier in the film, instead of crosscutting between the tramp outside and the wife indoors, Suspense gives us both in the same shot, with the tramp peeking in behind her.

A more ingenious revision of the crosscutting schema comes during the shots on the road. Instead of cutting between the father in the stolen car and the police pursuing him, Suspense packs them into the same frame. This is done not only in long shot but also in striking depth compositions.

Flashiest of all are the shots showing the pursuers reflected in the rear-view mirror of the father’s car as he races ahead of them.

Again, a single framing has done duty for two shots, one of the father looking back and another showing the cops coming closer to him. By compressing several lines of action into a single frame, our 1913 film doesn’t need to use significantly more shots than the 1909 one.

These are just a few of the imaginative ways in which Weber and Smalley have recast their standard situation. I could have considered as well the unobtrusive use of the knife as a multi-purpose prop, the echoed shots of mirrors, and the shrewd employment of repetitions in the intertitles.

It would take an early-cinema specialist like Keil to trace out all the connections between Suspense and other films of its era. One among many would be the fact that Griffith wasn’t exactly standing still between 1909, the year of The Lonely Villa, and 1913. For instance, his Battle at Elderbush Gulch, made about the same time as Suspense (though released in 1914), displays far more rapid cutting than Weber and Smalley attempt. Griffith also employed a swelling advance to the foreground, like that of the tramp shot I showed above, in The Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912).

Here, Smalley and Weber seem to have replicated a schema that was believed to ratchet up tension, the so-called looming effect.

The very title of the film exhibits self-consciousness about its artistic purpose. By 1913, it seems, American filmmakers were confident enough in their skills to announce their aims. We want, the title seems to say, to arouse you, to make you wait, hanging there, for the resolution. We know how to tell a twelve-minute story cinematically. The film seems uncannily to anticipate all those one-word titles that Hitchcock invoked to unsettle us–Suspicion, Spellbound, Psycho, Frenzy. As in a Hitchcock movie, the fact that we are pretty certain how Suspense will turn out doesn’t seem to dissipate our anxiety. (For more on this paradox of suspense, see this entry.)

Tunnel vision

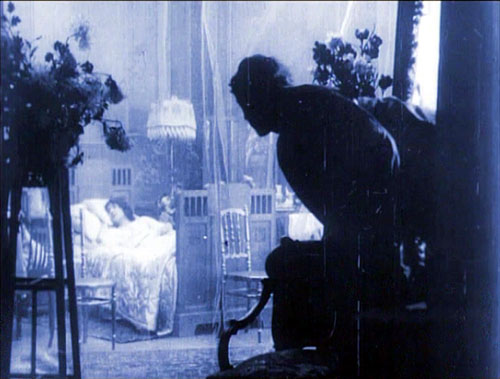

It was during the Pordenone 1913 season that the full brilliance of Victor Sjöström’s Ingeborg Holm hit me. I had seen the film a couple of times before and found it deeply moving in its restrained treatment of a poignant situation. The film traces the dissolution of a family. Sven Holm is doing a brisk retail business, but his health problems, along with a thieving clerk, plunge the family into poverty. When Holm dies, his wife Ingeborg must take the children into the poorhouse, and from there they are boarded out to foster families. Her plight worsens over the years, and its sorrowful depths are revealed when her son, now grown, returns to visit her.

Ingeborg Holm has long been recognized as a milestone in European film, not least for its effect on improving Sweden’s treatment of the poor. (8) The acting style is muted and delicate, with no mugging or arm-waving. For long periods, the main actors turn from the audience. (9) Just as impressive are the poised compositions, sustained in unhurried long takes. These give what is essentially a bourgeois tragedy a kind of majestic relentlessness. Watching, I remembered what Dreyer had admired in Sjöström’s Ingmar’s Sons (1918):

The film people here at home shook their heads because Sjöström had really a boldness to let his farmers walk heavily and soberly as farmers do. Yes, they used up an eternity to come from one end of the room to the other. (10)

But sitting in the Cinema Verdi in 1993, I spotted yet another level of artistry. Knowing the story of Ingeborg Holm, I was able to watch the shots unfold. I could study how Sjöström was unobtrusively moving characters so that they became shifting centers of interest. Although he didn’t cut in to close-ups, he harmonized his actors’ movements so that at one point you noticed Ingeborg, at another her husband. Performers spread themselves across the frame, arrayed themselves in depth, turned from or toward the camera. Most subtly of all, one actor might mask another one, driving our attention to other parts of the frame. Sjöström could sustain this intricate play of blocking and revealing for minutes on end.

My favorite example of this tactic is the three-minute passage showing Ingeborg’s daughter and son taken away by new mothers. You can read the whole discussion on pp. 191-195 in On the History of Film Style (1997), but here is an excerpt, with stills intercalated. (These stills, grabbed from the DVD, lack a little on the left. The film has been printed and reprinted so many times, and now fitted to the TV monitor, that it has lost some information along that edge.)

Ingeborg’s entry with her children from the rear doorway establishes the trajectory that will be followed during the scene, as foster mothers come in and take away the children. (Again, the scene is built around movements toward and away from the camera.) In a brilliant stroke, Sjöström immediately plants the young son in the foreground, back to us. The boy will stand there immobile for this first phase of the scene, occasionally serving to block the superintendent.

Ingeborg buries her face in her daughter’s shoulder at the precise moment the foster mother enters from the rear left. She passes behind Ingeborg, and as she is momentarily blocked, the superintendent twitches into visibility, handing the woman a document to sign.

During the signing, when the woman is briefly obscured, the superintendent shifts position again and Ingeborg lifts her face once more. Then Ingeborg and her daughter move slightly leftward as the foster mother comes forward.

This phase of the scene concludes with the departure of the daughter and the embrace of Ingeborg and her son in the foreground, once more concealing the superintendent.

Granted, I picked one of the film’s most exactingly staged scenes, but there are several other examples. Consider the climax, when the adult son comes to visit Ingeborg: the camera position and staging ask us to recall the scene I’ve just mentioned. Or take a look at the handling of the space behind the counter in the various scenes in the Holms’ shop. One instance surmounts this section.

This choreography is hard to catch on the fly: by the time you notice a change, what prepared for it has gone. To understand the overall dynamic, we must reverse-engineer the effects, moving backward from the result to the conditions. As I studied the film, it became clear that creating shifting centers of interest was basic to the scenes’ effects. All the finesse of acting, both solo and ensemble, would come to little if we weren’t primed to watch the most important area of the shot. Directors of the 1910s became supremely skilful in guiding our eye from one major story point to another within the fixed frame.

Some of the tactics of guiding our attention could be borrowed from other arts. Painting and theatre supplied certain schemas, like placing an item in the center of the picture format and turning faces toward the viewer. But some tactics for directing our eye relied on capacities that were as “specifically cinematic” as cutting was argued to be. Theatre is staged for many sightlines, but cinema is staged for a single one, that of the camera lens. That fact allowed directors to organize the unfolding action in depth, prompting the viewer to notice things at many distances from the camera.

It also allowed a precise blocking and revealing of information that would not work on the stage. In a live theatre performance, the slight shifts we detect in the Ingeborg Holm scene would be apparent to only very few viewers; people sitting in other vantage points wouldn’t see them. For another example of this phenomenon, go elsewhere on this blogsite.

There’s a more basic explanation of what’s going on. Cinematic space is a result of optical perspective, like the space of classic painting. The actors may seem to be standing in a cubical space, but in fact they move within a tipped-over pyramid, with the tip resting at the camera lens. They work inside a ground area that’s the shape of a slice of pie. Here’s a reminder from The Black Ball.

When there are figures close to the camera, as here, they fill up more of the frame, indicating that the field of view has narrowed. Filmmakers of the 1910s had discussed this property of their “cinematic stage,” so as researchers we can confirm that the control of position and timing we observe on screen results from the firm intentions of the makers. They might have echoed Uccello, the Renaissance artist who bent over his drawings late at night and exclaimed: “How sweet a thing is this perspective!”

Suddenly the tableau tradition made sense to me. Directors had to organize both the two-dimensional composition and the tapering three-dimensional playing space in front of the camera. The purpose was to create ever-changing centers of interest, laterally and in depth, flowing along with the key moments in the unfolding action.

By studying the same tactics in Feuillade, Bauer, and others, I found that these principles offered a fruitful way to understand much of what was happening in the films of the tableau era. The dynamic of schema and repetition/revision was at work as well, since I found earlier, more rudimentary uses of these principles; these were then refined during the 1910s. Moreover, the idea helped me generalize beyond that era and analyze later directors, including Mizoguchi Kenji and Hou Hsiao-hsien, who also used staging to shape the viewer’s experience. The results can be found in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light. Those books largely owe their existence to that flash of awareness kindled by Ingeborg Holm. (11)

We can’t reconstruct Sjöström’s stylistic development with much confidence. (12) His first directed film, The Gardener (Trädgärdsmästaren, 1912) survives, but I saw it before I knew how to watch 1910s movies in this way, so I can’t comment on it. Of the twenty-six films he made from 1912 to 1917, nearly all have been lost. Apart from Ingeborg, I have managed to see Havsagamar (The Sea Vultures, 1916). This retains aspects of the tableau tradition, but virtually no scenes display the intricate staging of his 1913 masterpiece.

In the late 1910s, judging by the films we have, Sjöström seems to have moved quickly toward continuity editing in the American vein. (13) The Girl from Stormycroft (Tösen frän Stormyrtorpet, 1917) contains extended passages of analytical editing, and the scenes display a freedom of camera setup one seldom sees in European cinema of the period. Sjöström clearly understands the principles of continuity down to the smallest detail. For instance, he not only uses the frame-edge cut (the cut that lets a character exit one shot and enter another, as the body crosses the frameline); he accelerates it. Our heroine leaves the kitchen, and in the shot’s final frame she hits the right edge. Another director would have had her exit the frame entirely and held the kitchen shot a little longer, to give her time to get to the next room. But Sjöström simply cuts to her already in another room, completing her trajectory.

Sjöström presumes that the constant pace of her approach and the vector of her movement will smooth the shot-change. It does, but few directors of that day would had such confidence that our mind would create continuity of motion.

During this summer’s archive viewing, I spent some time studying Sjöström’s cutting in The Girl from Stormycroft and subsequent films. I may offer some more thoughts later. For now I’ll just say that in these early years we seldom encounter such a versatile director, one who mastered the tableau tradition and then moved, with apparently little effort, to nuanced continuity editing. More generally, examining his technique isn’t a dry exercise. We never lose by studying craftsmanship. Sjöström’s films succeed because his style carefully guides our moment-by-moment apprehension of the heart-rending stories he has chosen to tell.

Have I convinced you to surrender your credit-card number? Suspense is available in a dazzling Flicker Alley collection, Saved from the Flames, compiled from the French series Retour de flame. Ingeborg Holm comes with a tinted print of the estimable Terje Vigen (A Man There Was) on a DVD from Kino. The latter disc includes vibrant scores from Donald Sosin and David Drazin.

(1) For the purposes of the outstanding Encyclopedia of Early Cinema (New York: Routledge, 2005), the editor Richard Abel considers that the early cinema constitutes the period from film’s invention ca. 1894 to the mid-1910s.

(2) Silent films were still made into the 1930s, notably in Russia and Japan—a situation that shows the rough-and-ready quality of period divisions.

(3) For an informative series of articles around the 1913 theme, see Griffithiana no. 50 (May 1994).

(4) Gombrich proposes these ideas at various points in Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation, new ed. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000). The book is a milestone in twentieth-century humanistic inquiry.

(5) The Lonely Villa (1909) has, in the version I’ve seen, 54 shots in a 750-foot reel (that is, about twelve and a half minutes at 16 frames per second). Suspense has nearly the same number of shots, 56, in about the same running time.

(6) Sharp-eyed readers will recognize one of these shots as Fig. 5.82 in Film Art: An Introduction, 8th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008), 187.

(7) Eileen Bowser, The Transformation of Cinema 1907-1915, vol. 2 of History of the American Cinema (New York: Scribners, 1990), 65.

(8) For more background on the film, see Jan Olsson, “‘Classical’ vs. ‘Pre-Classical’: Ingeborg Holm and Swedish Cinema in 1913,” Griffithiana no. 50 (May 1994), 113-123.

(9) Kristin wrote about this technique in “The International Exploration of Cinematic Expressivity,” in Film and the First World War, ed. Karel Dibbets and Bert Hogenkamp (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 1995), 65-85. She also discusses it in our Film History: An Introduction, 2d ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), 67.

(10) Carl Dreyer, “A Little on Film Style,” Dreyer in Double Reflection, ed. and trans. Donald Skoller (New York: Dutton, 1973), 133.

(11) I was probably primed for this by lectures presented by Yuri Tsivian, who has long been studying mirrors in 1910s cinema and calculating how they revealed offscreen space.

(12) Detailed information on Sjöström’s relation to the film industry in these years can be found in John Fullerton’s epic Ph. D. thesis, The Development of a System of Representation in Swedish Film, 1912-1920 (University of East Anglia, 1994). See also Fullerton, “Contextualising the Innovation of Deep Staging in Swedish Film,” Film and the First World War, ed. Dibbets and Hogenkamp, 86-96.

(13) Several people have analyzed Sjöström’s editing. Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs’ Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 133-136 shows how cutting supports the acting in a crucial scene of Ingmar’s Sons. Tom Gunning’s essay “‘A Dangerous Pledge’: Victor Sjöström’s Unknown Masterpiece, Mästerman,” in John Fullerton and Jan Olsson’s anthology Nordic Explorations: Film before 1930(Sydney: John Libbey, 1999), 204-231, argues that Sjöström’s cutting gives his characters a degree of psychological opacity. Most recently, in an unpublished paper Jonah Horwitz discusses patterns of performance, composition, and editing in Terje Vigen (1917).

Twilight of a Woman’s Soul (1913).

PS 31 August: Some corrections. David Cairns writes to point out that the triangle at the top of the frame in the Suspense split-screen isn’t a lamp but simply the shade behind the father’s head, cropped by the masking. Wishful thinking on my part, I’m afraid. By the way, David has an intriguing movie giveaway going on his site.

Roland-François Lack corrects dates on two of my Greatest French Hits from 1960: “The great Marker from that year is Description d’un combat, not Lettre de Sibérie (1958), and likewise Rouch’s Moi un noir is from 1958.” Thanks to him and David. To my original list, I should probably have added Cocteau’s Testament d’Orphée, released in 1960.

Some cuts I have known and loved

DB here, belatedly:

We’ve been so busy revising our textbook, Film History: An Introduction, for its third edition that we’ve had no time to see new movies, let alone blog on our regular schedule. To those loyal readers who have been checking back occasionally, we say: Thanks for your patience. An entry that should intrigue you is in the works, possibly to be posted very soon.

In the meantime, here’s an item on a subject I’ve been meaning to slip in at some point. It’s a tribute to cuts I admire.

Warning: Superb as Eisenstein’s, Ozu’s, and Hitchcock’s cuts are, I’m deliberately leaving them out. Too obvious!

Kata and cutting

Okay, Kurosawa is an obvious choice too, but I can’t pass up some of the first outstanding cuts I noticed in his work, back when I was projecting movies for my college film society. The cuts occur during the climactic battle of Seven Samurai (1954).

As is well-known, Kurosawa shot the sequence with several cameras using different focal-length lenses. What is less often acknowledged, I think, is the power of certain cuts as they combine with fixed camera positions. In his last films, Kurosawa would rely strongly on long-lens shots that pan over the pageantry of his crowd scenes, but here he exploits static frames.

In the eye of the battle, Kambei fires his arrow in one shot, and a horseman falls victim to his marksmanship in the next. So far, so conventional. But what’s unusual is that we don’t actually see the arrow hit its target. Kambei fires, and Kurosawa cuts to an empty bit of the town square, churned with mud and dimly visible through horses’ legs. Only after an instant does a fallen bandit skid into the telephoto frame.

The same thing happens when Kambei shoots his second arrow: we must wait for the victim to plunge into the frame.

The result, I think, is a sense of exhilarating inevitability. The camera knows that the horseman will fall, and it knows exactly where. That’s a way of saying that Kurosawa’s visual narration fulfills our expectation, but with a slight delay. The empty frame prompts us to anticipate that the man will be hit—why else show it?—and we have a moment of suspense in waiting to confirm what we expect. Moreover, the force of Kambei’s arm is given us through a principle of Movie Physics: motion communicated to another body is magnified, not diminished, and the fixed frame allows us to see just how far the bodies are propelled. The arrow must have been Homerically powerful if it sends these men to earth with such impact.

Most directors would have panned to follow the victim as, wearing the arrow, he tumbled off his horse and hit the ground. This choice would have been natural given the multiple-camera situation. Instead Kurosawa had his camera operators frame the exact spot the stuntman would hit and wait for the action to hurtle into the shot. The patient expertise of Kambei’s marksmanship has its counterpart in the confidence of Kurosawa’s style. (1)

The moving image, Mr. Griffith, and us

Then there’s Intolerance (1916).

The Musketeer of the Slums is trying to seduce the young man’s wife, the Dear One. He pretends he can retrieve her baby. But his earlier conquest, the Friendless One, has followed him to the tenement, and at the same time the Boy has learned about the Musketeer’s visit. As the Musketeer attacks the Dear One, the Boy bursts in. The two men struggle and the Boy is momentarily knocked out; the Dear One has swooned. So no one sees what really happens next: From the window ledge the Friendless One fires her pistol and downs the gangster. She flees, and the boy believes that he is the killer. He will be charged with the murder.

Here’s what I admire. Griffith sets the situation up with his usual rapid crosscutting—the Musketeer and the Dear One struggling, the Boy returning, and the Friendless One crawling out on the ledge. When the fight starts, Griffith shows the Friendless One growing wild-eyed at the window. She fires once, and Griffith gives the action to us in three shots: a medium shot of her in profile, a medium-long shot of the pistol at the window (irised so we notice it), and a long-shot of the room, as the Musketeer is hit.

Griffith repeats the series of shots when the Friendless One fires again.

This time the Musketeer staggers out to the hall and dies. Neatly, Griffith gives us three more shots, but omits the setup showing the Friendless One. Cut to the curtains again, with her hand waving the pistol, then to another long shot of the room as the gun is tossed in, and finally to a close-up of the pistol landing on the floor.

If you’re looking for a pattern, the pistol in close-up is in effect substituted for the shot of the Friendless One at the start of each cycle. But I’m most interested in the shots of the pistol. The first one at the window goes by at blinding speed—ten frames in the two prints Kristin and I have examined. (2) That works out to a bit more than half a second, if you assume 16 frame per seconds as the projection rate, which was common at the time.

Okay, fussy, but I’ve already confessed that I turn into a frame-counter, when I get the chance. The second shot of the pistol poking out of the curtains, parallel to the first, is also ten frames long. Griffith seems to have been a frame-counter too.

What’s most remarkable is that the long-shot of the pistol being flung into the room is even briefer than these closer views—only seven frames long, or less than half a second at 16fps. As a nice touch, the close-up of the pistol landing in the corner is twice that (15 frames).

In the decades that followed, directors would believe that long shots shouldn’t be cut as fast as close-ups, so the Intolerance passage can strike us as a typical Griffith misjudgment. But I admire his willingness to cut long shots so fast. It certainly creates a percussive accent. In case we didn’t catch the story point, the close-up of the pistol hitting the floor clinches it.

This is the sort of sequence that the Soviet filmmakers probably learned from. They may even have gotten ideas from Griffith’s interspersed black frames (two by my count) before each of the shots of the pistol thrusting out of the curtain. (3)

Behind the desk

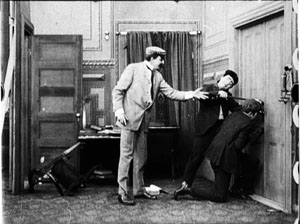

Speaking of the Russians, one of my favorite cuts in Pudovkin’s movies comes during a confrontation in The End of St. Petersburg (1927). The somewhat oafish young worker known only as the Lad, who has sold out his comrades, attacks the boss Lebedev in his office. He seizes the boss and shoves him down, jamming him between his desk and the window. We see the action from one angle and then what seems to be an opposing angle.

Actually, this is a big discontinuity. Using the desk, the telephone, and the window as reference points, we can see that in the first shot, the Lad moves in from the left side of the desk to push the boss down. In the second, he has come in from the right side and Lebedev’s head is pointing in the opposite direction. We can see the weirdness of this more clearly if we simply flip one of the frames: now it looks like a consistent change of angle.

Pudovkin has created an impossible event. But the cut gives the strong sense of graphic conflict that the Soviets (not just Eisenstein) sought, creating a kind of visual clatter to underscore the violence of the action. It’s possible that Pudovkin actually flipped a “correct” framing to create the disjunction, as some of his contemporaries did. (4)

Meg, all aflutter

Pudovkin’s cut reminds us that filmmakers can get away with a lot if they change the angle drastically. It’s harder to spot a cheated element or a mismatch if the new shot makes us reorient ourselves. Why does this happen? That’s a subject for research, as I’ll suggest at the end.

Here’s another tricky item. In Kate & Leopold (2001), Kate has brought her time-traveling guest to an audition for a butter commercial. In the studio, he’s behind her as she tries to convince her colleagues to watch him. As she talks, she first watches Leopold in the monitor above them, then swivels to talk to her boyfriend and other suits. The camera positions change 180 degrees.

This drastic shift works to prepare us for a remarkable cut a little later. Kate waves her hand, saying she only needs two minutes. She pivots her body, moving her hand downward.

Cut 180 degrees to a setup similar to the one we’ve seen earlier: She drops her hand to her side as she swings to us.

The gesture is smoothly matched. The only trouble is that it’s executed by the wrong hand. In the first shot Kate is wiggling her left hand, but in the second, it’s her right hand that continues the movement and drops to her hip.

I don’t think that many people would notice this. Indeed, when I first saw the film, I felt a bump hereabouts, but when I watched it over again on DVD, it looked fine to me. Then I watched it again and saw what was wrong. Even then, I thought I might be hallucinating. It’s one of the trickiest cheats I know of, and it’s beautifully done.

The real question is: Why don’t we notice it? We usually say, “Because we’re watching the story and ignore little irregularities.” But that’s not very satisfactory. Why isn’t the wave of Kate’s hand part of the story? We certainly notice it as expressing her attitude—hence as part of the story. And if you didn’t notice the disjunction in my End of St. Petersburg example, the same question arises: Isn’t the Lad’s attack on the boss the very story action we’re watching?

Consider the alternative. If director James Mangold had matched the left hand, it would have to cross the center of the frame as Kate pivots, shifting from screen left to screen right before landing at her hip. It would have been ostentatious and somewhat graceless, and perhaps that would have been distracting. So the mismatch is perhaps a line of least resistance, a compromise–as so many stylistic choices are.

In addition, Kristin suggests that our pickup is made easier by the placement and action of the hand. In both shots it’s quite central and moving in the same direction at the same rate, so that it’s easy to read as a graphically continuous element across the cut.

Perhaps too the fact that we’re switching our position 180 degrees leads us to expect, wrongly, the sort of reversal we get here—the way that we think our reflection in a mirror is the way we really look. And of course the earlier 180-degree switch, in which no mismatch occurs, probably serves to prime us for the shift in orientation this provides.

Mangold doesn’t mention the cut in his director’s commentary on the Kate & Leopold DVD, but when I asked him he said: “I think of shots as blocks, like legos or words. I don’t want them to resolve–come to an end. . . . Movement cuts work as long as the action is somewhat similar. The tough continuity cuts when you have a mismatch are the still ones.” Even if the mismatch here was accidental, it works very well. More generally, like other mismatches this one obliges us to think about what we see and what we don’t see when we watch a movie.

Hawks’ eyes

Among the many pleasures of Howard Hawks’ movies are their lovely matches on action. Of course his editors had a lot to do with this, but Hawks clearly had to provide the right footage so that it could be precisely matched. Bringing Up Baby (1938) yields a crisp cut as Susan, perched on the constable’s desk, strikes a match. (I show the cuts from a 16mm print; enough of this video stuff.)

Here Hawks seems to rely on what’s been called the two-frame rule: If you’re going to match on action, overlap the action by two frames to show a bit of the action again. This allows the audience time to absorb the fact of the cut and then to see the action as continuous. But Hawks could be quite cavalier about his matches as well. The golfing scene from Bringing Up Baby is full of wild cuts.

The caddies advance and recede, Susan and David are caught in different postures, and at some cuts they’re striding across different parts of the course. These cuts have a swagger about them, as if Hawks is daring us to spot his outrageous cheats. How many of us do?

All these trompe l’oeil effects can be studied psychologically, and prominent researchers who have tested such effects in the laboratory are attending our 11-14 June meeting of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. Dan Levin studies discontinuities in film from the standpoint of “inattentional blindness”; here he’s interviewed by Errol Morris. Barry Hughes of Arizona State University at Tempe has probed the two-frame rule, and he’s talking in Madison as well. Go here for more information; I’ve plugged the event previously here.

Next time, we expect: Secrets of film restoration.

(1) Kurosawa has prepared us for this passage when Kikuchiyo’s sword attacks the bandits earlier in the sequence. There too a shot of his flailing stroke is followed, after a pause on a patch of mud, by a falling horseman. But the calm deliberateness of Kambei’s drawing of his bow enhances the sense of inevitability, I think. Kiku does his damage through furious energy, but Kambei hits his mark thanks to a mature warrior’s almost contemplative precision.

(2) Forget checking these frame counts on DVD. I get several different counts, depending on the player I use. For reasons discussed here, DVDs don’t preserve the original film frames, and in a fast-cut passage you can lose any sense of how many frames the shot lasted.

(3) By the way, Griffith died on 23 July 1948, my first birthday.

(4) For more on this extraordinary movie’s use of discontinuity editing, see Vance Kepley, Jr., The End of St. Petersburg (London: Tauris, 2003).

Three nights of a dreamer

DB here:

The close-up blogathon launched by Matt Zoller Seitz is over, but it contains enough specimens and analyses for a hefty book. It also inspired Jim Emerson to devote a cine-lyric to the close-up. I missed the deadline, so I suppose that this constitutes my sideways contribution to Matt’s enterprise.

Sideways, because a full-blown analysis of In the City of Sylvia (En la ciudad de Sylvia; Dans la ville de Sylvie) would be a breach of decorum. Most people haven’t heard of this new film by José Luis Guerin, let alone seen it. I saw it at the Vancouver festival in September, and it will make its way through the festival circuit over the coming months and should show up on cable or DVD thereafter. But apart from calling attention to it as a remarkable film, I want to look at one of its most absorbing sequences and suggest some of its originality. Lee Marshall has already pointed out one of Sylvia‘s arresting features:

Guerin seems to have created pure drama without recourse to story. We’re always taught that story is the engine of drama. Not here: somehow Guerin has created an almost plotless film that has the dramatic tension of vintage Hitchcock. (1)

Although the story situation is slight, the tension we feel springs partly from vivid stylistic patterns. In other words: Minimal and uncertain story action is heightened by engaging visual narration. This narration in turn derives its power from one of the most traditional devices of filmic storytelling.

Consider the other person’s point of view

The point-of-view shot is a mainstay of cinematic storytelling, and its history is an intriguing one. Many of the earliest examples we have are motivated as views through optical gadgets. Two films by the Englishman G. A. Smith, both from 1900, handily show the options. Grandma’s Reading Glass justifies the point-of-view image as what the boy sees when he peers at granny through her big magnifier.

Smith’s As Seen through a Telescope motivates the cut-in POV shot as what our dirty old man in the foreground has an eye for.

Fairly soon, this use of the magnifying POV shot was mingling with more straightforward ones. In The Birth of a Nation (1915), D. W. Griffith offers a rough-edged example. When the Stoneman brother and sister visit Ford’s Theatre on the night of Lincoln’s assassination, we see Elsie pointing out the famous actor John Wilkes Booth.

Booth is framed in an iris, which Griffith often uses to underscore an important image. But when Elsie studies Booth through her opera glasses, Griffith, usually not fastidious about such things, supplies the same irised image, now doing duty for the sort of magnifier-masking we get in the Smith films.

Presumably a more consistent technique would show Booth in long shot first, without the iris, and reserve the optical masking for replicating the view through the opera glasses. This is what happens in Ernst Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan (1926), which contains a sequence built entirely around crisscrossed character looks. (1)

The woman of the world Mrs. Erlynne arrives at the racetrack and creates a stir, causing many men to watch her from all over the grandstand.

Note that Lubitsch has gone beyond Griffith by fitting the angle of Shot B to the viewer’s orientation, looking up. There are so many POV shots that at one point Lubitsch simply shows her from different angles and deletes the shots of each watching man.

This is a fascinating example of a process we often see in stylistic history. An “overlearned” visual convention can be treated elliptically; the filmmaker can leave out bits and we’ll fill them in. The binocular masking suffices to let us know that Mrs. Erlynne is being studied from afar. Moreover, Lubitsch gets an expressive bonus from being so concise. Now it doesn’t matter who’s watching, just that somebody is—actually, a lot of somebodies.

Later, after much more byplay with people looking at one another and misunderstanding what they see, Mrs. Erlynne sits down. Three gossips have been studying her, but now their view is blocked. So one gossip has to twist around to spy on her, and Lubitsch obligingly gives us a slightly tipped point-of-view framing—a full shot, without masking.

Adjusting her binoculars, the gossip is able to get a bigger view of Mrs. Erlynne, and she racks focus gleefully to catch a gray hair peeping out.

The visual narration in this sequence, already perfectly modulated, supplies the stylistic premise for Hitchcock’s Rear Window and all of its progeny, most recently Disturbia (2007). What might be overlooked is that by the 1920s the view through a device—field glasses, a microscope, a surveillance camera—had become a special, marked case. From then till now, the default POV pattern is the simple shot of a character looking, followed by an unadorned shot of what that person sees, from more or less the correct standpoint. Lubitsch’s sideways shot of the gossip’s view of Mrs. Erlynne, casually introduced, exemplifies the modern norm for presenting a character’s vision, and it’s so common that we seldom notice it.

POV shots: The basics

In his book Point of View in the Cinema, Edward Branigan itemizes the cues that the filmmaker can manipulate in creating a POV construction. (2) To simplify somewhat: Shot A shows a point in space and a character glance from that point. Shot B is taken from a camera position more or less approximating the point in A, and it shows an object. The shot-change presumes temporal continuity between A and B, and we assume as well that the character is aware of the object shown in B.

This seems like a complicated way of stating the obvious, but by teasing these elements apart, Branigan shows that each one can be manipulated in intriguing ways. For example, you can create a disorienting moment by violating the condition of temporal continuity. Ozu does this in Early Summer (1951), when Noriko and Aya decide to peek in at the man Noriko almost married. The two women tiptoe down a hall toward us as the camera tracks slowly backward. Ozu cuts to a forward-tracking shot that momentarily suggests a reverse angle POV on the corridor.

In fact, however, the camera movement is revealed to be the first shot of a new scene, among different characters, and we won’t ever see the man the two women went to spy on.

Here’s another interesting case, not cited by Branigan. In Halloween (1978), John Carpenter shows Laurie looking out a window and seeing Michael Myers in his mask, standing between fluttering washlines.

Cut back to Laurie, now frowning slightly.

Cut to a second POV shot; but now Michael has vanished.

This simple change in shot B’s object, Michael himself, has an uncanny effect. Did Michael just walk away from the washline? If so, this is an odd way to present it. Why not show him walking away? Alternatively, did he just disappear? Surely not; Laurie would be shocked. Carpenter wins twice over. Without obviously violating realism or directly showing that Michael has supernatural powers, he gives Michael the ability to come and go in a ghostly fashion. By the end of the film, when he miraculously disappears after a fall that would kill an ordinary person, we are prepared to believe that he is indeed, as Dr. Sam Loomis says, the Boogyman.

Who is Sylvia? What is she that all the swains commend her?

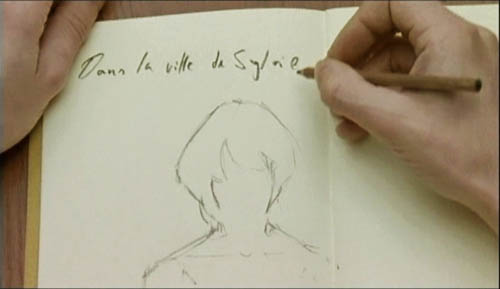

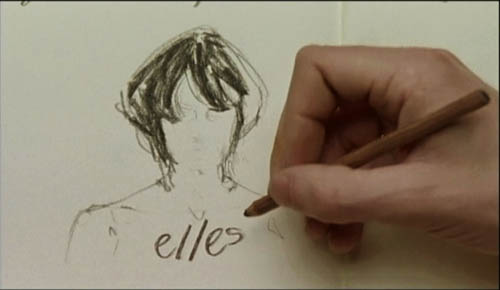

In the City of Sylvia centers on a young man staying at a hotel. We’re given no reason why he’s visiting the city, and no backstory about him. One day he’s sitting at a café. Now, across nearly twenty minutes of screen time he watches women and idly sketches them.

The sequence is a pleasure to watch, partly because of the constant refreshing of the image with faces, nearly all of them gorgeous, most of them female. Either Strasbourg has an extraordinary gene pool, or this café attracts only Ralph Lauren models. Yet the scene builds curiosity and suspense too, thanks to Guerin’s sustained and varied use of optical POV. He gives us an almost dialogue-free exploration of a cinematic space through one character’s optical viewpoint. (Stop reading here if you don’t want to know anything more about the film before you see it.)

The young man, known in Guerin’s companion film Unas fotos en la ciudad del Sylvia as the Dreamer, is almost expressionless as he scans the women’s faces. Slight shifts of his glance are accentuated by his habit of turning his head but keeping his eyes fixed. In over a hundred shots, Guerin uses some ingenious cinematic means to tease us into ever-greater absorption in the Dreamer’s visual grazing.

Fairly far into the sequence, Guerin gives us more or less the orthodox POV construction. The Dreamer looks at one woman at a table, and we see her return his look.

But here shot B isn’t really clean: the hands of the woman on the left sometimes block our view of the principal woman. This obtrusiveness is one of Guerin’s most basic strategies in the sequence. Inevitably, in passages before and after the cut I just showed, what the Dreamer is looking at is partially hidden in layers of faces and body parts.

Our prototype of the POV cut presumes a more or less single ‘point’ we are watching in shot B, but throughout this scene Guerin plays with this cue. He tantalizes us with several points to be observed, and he often obscures the most important ones. He also creates some startling juxtapositions. Near the very start we get this shot, which may or may not be the Dreamer’s POV.

By making the background girl seem to kiss the foreground guy, Guerin, as Eisenstein would say, “christens” his sequence. In effect, the image says: Watch out! Layered space will become important! When I saw this shot, I nearly jumped out of my seat.

The Dreamer is treated no differently, at least at the start. In most movies, the POV construction is set up with a clear, clean framing of our looker in shot A. Here, though, at the start of the scene Guerin peels away layers to get to our man. For the first six shots of the café, we don’t know he’s on the scene. Then he’s shown out of focus, in the background of more prominent action. The woman in the foreground has been primed to be the shot’s subject. At the moment she shifts her gaze and we try to read her expression, a second woman on the distant right shifts aside to reveal the Dreamer behind her.

Surely this is the most unemphatic entry of a protagonist we’ve seen in a while! Guerin is able to add planes to block the main ‘point’ of shot B because he’s working with long lenses, a crowded space, and careful choreography. Even focus plays a role, as in this case; our Dreamer is pretty hazy.

One upshot of this strategy is that we’re plunged into a “cubistic” space, in which slightly varied camera angles pick up bits of space we’ve seen in earlier combinations and oblige us to assemble it all in our head. Be thankful for the guy in the blue shirt above, for he plays an anchoring role in several setups that would otherwise float free.

It’s hard to convey in stills how much fascination and frustration that this teasing style creates. Like the Dreamer, we’re given only glimpses of the women, and even though we don’t know his purposes—is he just an artist in search of beauty? a serial killer picking out victims?—the partial views lure us at several levels. We try to complete the faces. We try to infer the women’s state of mind from their expressions and gestures, which are far more animated than our Dreamer’s.

And a search for story plays a part here. We’re primed for some action to start, and we browse through these shots looking for anything that might initiate it. Each face the Dreamer spots promises to kick-start a plot: when the Dreamer gets a full view of one of these women, perhaps things will get going.

Without giving away every detail, I’ll just say that the sequence has a strong visual arc as the Dreamer starts paying more and more attention to certain women. And just as he finally gets a full view of one fabulous face, his attention wanders to . . . another layer, this time one inside the café.

As he gapes at the woman inside, layers pile up, creating a cubistic climax of all the optical obstructions we’ve encountered.

The motif of reflections will take over the rest of the film’s visual design, and eventually we’ll see that some of the Dreamer’s drawings evoke the piled-up and sliced-up faces in the café shots.

Later in the film, the Dreamer will explain why he’s in the city and why he’s scanning women. We’ll have a tram ride that Guerin compares with Sunrise, and a scene in a music club that not only parallels the café sequence but evokes Manet. We’ll also have occasion to compare this film with Bresson’s Four Nights of a Dreamer, a citation signaled from the outset.

All that is to come. Even if the later scenes weren’t as compelling as they are, this café sequence would make Sylvia one of the most adventurous films I’ve seen this year. By revising the simple, long-lived POV schema, Guerin has made it yield fresh feelings and implications. Like Lubitsch’s racetrack scene, this imaginative sequence provokes the jubilation you feel in the presence of calm, precise artistry.

(1) Lee Marshall, “Past Perfect,” Screen International (19 October 2007): 27. The web version is here, but it may require a subscription.

(2) I analyze the visual narration of Lady Windermere, which I think deserves to be ranked with Potemkin and Sunrise, in Narration in the Fiction Film (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985), 178-186.

(3) Edward R. Branigan, Point of View in the Cinema: A Theory of Narration and Subjectivity in Classical Film (The Hague: Mouton, 1985), 102-121.

Do filmmakers deserve the last word?

DB here:

On 3 December 1913, the above advertisement appeared in the New York Dramatic Mirror. D. W. Griffith had left the American Biograph company and set out on an independent path that would lead to The Birth of a Nation and beyond. Because Biograph never credited directors, casts, or crews, he wanted to make sure that the professional community was aware of his contributions. Not only did he point out that he had made several of the most noteworthy Biograph films; he also took credit for new techniques. He introduced, he claims, the close-up, sustained suspense, restrained acting, “distant views” (presumably picturesque long-shots of the action), and the “switchback,” his term for crosscutting—that editing tactic that alternates shots of different actions occurring at the same time.

Griffith’s bid for credit was a shrewd move for his career, and it had repercussions after the stunning success of The Birth of a Nation two years later. Many historians took Griffith at his word and credited him with the breakthroughs he listed. He became known as the father of “film grammar” or “film language.” The idea hung on for decades. Here’s the normally perceptive Dwight Macdonald, criticizing Dreyer’s Gertrud for being anachronistic:

He just sets up his camera and photographs people talking to each other, usually sitting down, just the way it used to be done before Griffith made a few technical innovations. (1)

Filmmakers believed the Griffith story too. Orson Welles wrote of the “founding father” in 1960:

Every filmmaker who has followed him has done just that: followed him. He made the first close-up and moved the first camera. (2)

In the late 1970s a new generation of early-cinema scholars gave us a more nuanced account of Griffith’s place in history. They pointed out that most of the innovations he claimed either predated his Biograph work, (3) or appeared simultaneously and independently in Europe and in other American films. Some Griffith partisans had already conceded this, but they maintained that he was the great synthesizer of these devices, and that he used them with a vigor and vividness that surpassed the sources.

That judgment seems right in part, but Eileen Bowser, Tom Gunning, Barry Salt, Kristin Thompson, Joyce Jesniowski, and other early-cinema researchers have drawn a more complicated picture. (4) Griffith did speed up cutting and devote an unusual number of shots to characters entering and leaving locales. But these innovations weren’t usually recognized as original by previous historians. More interestingly, much of what Griffith did was not taken up by his successors. His technique was idiosyncratic in many respects. By 1915 younger directors like Walsh, Dwan, and DeMille were forging a smoother style that would be more characteristic of mainstream storytelling cinema than Griffith’s somewhat eccentric scene breakdowns. Instead of creating film language, he spoke a forceful but often unique dialect.

The New York Dramatic Mirror ad coaxes me to reflect on how filmmakers have shaped critics’ and historians’ responses to their work. Hawks and Hitchcock developed a repertory of ideas, opinions, and anecdotes to be trotted out on any occasion. Today, directors write books, give interviews, appear on infotainment shows, and provide DVD commentary. We know that many of the talking points are planned as part of the film’s publicity campaign, and journalists dutifully follow the lead. (In Chapter 4 of The Frodo Franchise, Kristin discusses how this happened with Lord of the Rings.) For many decades, in short, filmmakers have been steering critics and viewers toward certain ways of understanding their films. How much should we be bound by the way the filmmaker positions the film?

Deep focus and deep analysis

Citizen Kane (1941).

Determining intentions is tricky, of course. Still, I think that in many cases we can reconstruct a plausible sense of an artist’s purposes on the basis of the artwork, the historical context, surviving evidence, and other information. (5) This may or may not correspond to what the artist says on a particular occasion. For now, I want simply to point to one instance in which filmmakers have shaped critical uptake, with results that are both illuminating and limiting.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, André Bazin, one of the great theorists and critics of cinema, argued that Orson Welles and William Wyler created a sort of revolution in filmmaking. They staged a shot’s action in several planes, some quite close to the camera, and maintained more or less sharp focus in all of them. Bazin claimed that Welles’ Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons and Wyler’s The Little Foxes and The Best Years of Our Lives constituted “a dialectical step forward in film language.”

Their “deep-focus” style, he claimed, produced a more profound realism than had been seen before because they respected the integrity of physical space and time. According to Bazin, traditional cutting breaks the world into bits, a series of close-ups and long shots. But Welles and Wyler give us the world as a seamless whole. The scene unfolds in all its actual duration and depth. Moreover, their style captured the way we see the world; given deep compositions, we must choose what to look at, foreground or background, just as we must choose in reality. Bazin wrote of Wyler:

Thanks to depth of field, at times augmented by action taking place simultaneously on several plane, the viewer is at least given the opportunity in the end to edit the scene himself, to select the aspects of it to which he will attend. (6)

While granting differences between the directors, Bazin said much the same about Welles, whose depth of field “forces the spectator to participate in the meaning of the film by distinguishing the implicit relations” and creates “a psychological realism which brings the spectator back to the real conditions of perception” (7).

In addition, Bazin pointed out, this sort of composition was artistically efficient. The deep shot could supply both a close-up and a long-shot in the same framing—a synthesis of what traditional editing had given in separate shots. Bazin wove all these ideas into a larger theory that cinema was inherently a realistic medium, bound to photographic recording, and Welles and Wyler had discovered one path to artistic expression without violating the medium’s biases.

There are many objections to Bazin’s argument, some of which I’ve rehearsed in On the History of Film Style. My point here is that Bazin was presenting analytical points that stemmed from publicity put out by Welles, Wyler, and especially their talented cinematographer Gregg Toland.

In a 1941 article in American Cinematographer, Toland talked freely about how he sought “realism” in Citizen Kane. The audience must feel it is “looking at reality, rather than merely a movie.” Key to this was avoiding cuts by means of long takes and great depth of field, combining “what would conventionally be made as two separate shots—a close-up and an insert—into a single, non-dollying shot.”(8) Toland defended his sometimes extreme stylistic experimentation on grounds of realism and production efficiency, criteria that carried some weight in his professional community of cinematographers and technicians. (9)

Toland’s campaign for his style addressed the general public too. For Popular Photography he wrote an article (10) explaining again that his “pan-focus” technique captured the conditions of real-life vision, in which everything appears in sharp focus. A still broader audience encountered a Life feature in the same year (11), explaining Toland’s approach with specially-made illustrations. Two samples show selective focus, one focused on the background, the other on the foreground.

An accompanying photo shows pan-focus at work, with Toland in frame center, an actor in the background, and Toland’s camera assistant in the foreground.

In sum, Toland’s publicity prepared viewers, both professional and nonprofessional, for an odd-looking movie.

Throughout the 1940s, Welles and Wyler wrote and gave more interviews, often insisting that their films invited greater participation on the part of spectators. In a crucial 1947 statement, Wyler noted:

Gregg Toland’s remarkable facility for handling background and foreground action has enabled me over a period of six pictures he has photographed to develop a better technique for staging my scenes. For example, I can have action and reaction in the same shot, without having to cut back and forth from individual cuts of the characters. This makes for smooth continuity, an almost effortless flow of the scene, for much more interesting composition in each shot, and lets the spectator look from one to the other character at his own will, do his own cutting. (12)

Some of this publicity material made its way into French translation after the liberation of Paris, just as Kane, The Little Foxes, and other films were arriving too. Bazin and his contemporaries picked up the claims that these films broke the rules. Deep-focus cinematography became, in the hands of critics, a revolutionary new technique. They presented it as their discovery, not something laid out in the films’ publicity.

But the case involved, as Huck Finn might say, some stretchers. Watching the baroque and expressionist Kane, it’s hard to square it with normal notions of realism, and we may suspect Toland of special pleading. Some of Toland’s purported innovations, such as low-angle shots showing ceilings, had been seen before. Even the signature Toland look, with cramped, deep compositions shot from below, can be found across the history of cinema before Kane. Here is a shot from the 1939 Russian film, The Great Citizen, Part 2 by Friedrich Ermler.

More seriously, some of Toland’s accounts of Kane swerve close to deception. For decades people presupposed that dazzling shots like these were made with wide-angle lenses.

Yet the deep focus in the first image was accomplished by means of a back-projected film showing the boy Kane in the window, while the second image is a multiple exposure. The glass and medicine bottle were shot separately against a black background, then the film was wound back and the action in the middle ground and background were shot. (And even the middle-ground material, Susan in bed, is notably out of focus.) I suspect that the flashy deep-focus illustration in Life, shot with a still camera, is a multiple exposure too. In any event, much of the depth of field on display in Kane couldn’t have been achieved by straight photography. (13)

RKO’s special-effects department had years of experience with back projection and optical printing, notably in the handling of the leopard in Bringing Up Baby, so many of Kane‘s boldest depth shots were assigned to them. But here is all that Toland has to say on the subject:

RKO special-effects expert Vernon Walker, ASC, and his staff handled their part of the production—a by no means inconsiderable assignment—with ability and fine understanding. (14)

Kane’s reliance on rephotography deals a blow to Bazin’s commitment to film as a medium committed to recording an event in front the camera. Instead, the film becomes an ancestor of the sort of extreme artificiality we now associate with computer-generated imagery.

Despite these difficulties, Toland’s ideas sensitized filmmakers and critics to deep space as an expressive cinematic device. Modified forms of the deep-focus style became a major creative tradition in black-and-white cinema, lasting well into the 1960s. Bazin’s analysis certainly developed Toland’s ideas in original directions, and he creatively assimilated what Toland and his directors said into an illuminating general account of the history of film style. None of these creators and critics were probably aware of the remarkable depth apparent in pre-1920 cinema, or in Japanese and Soviet film of the 1930s. Their claims taught us to notice depth, even though we could then go on to discover examples that undercut Toland’s claims to originality.

Some little things to grasp at

I assume that Toland and his directors were sincerely trying to experiment, however much they may have packaged their efforts to appeal to viewers’ and critics’ tastes. But sometimes artists aren’t so sincere. By the 1950s, we have directors who started out as film critics, and they realized that they could guide the agenda. Here is Claude Chabrol:

I need a degree of critical support for my films to succeed: without that they can fall flat on their faces. So, what do you have to do? You have to help the critics over their notices, right? So, I give them a hand. “Try with Eliot and see if you find me there.” Or “How do you fancy Racine?” I give them some little things to grasp at. In Le Boucher I stuck Balzac there in the middle, and they threw themselves on it like poverty upon the world. It’s not good to leave them staring at a blank sheet of paper, no knowing how to begin. . . . “This film is definitely Balzacian,” and there you are; after that they can go on to say whatever they want. (15)

Chabrol is unusually cynical, but surely some filmmakers are strategic in this way. I’d guess that a good number of independent directors pick up on currents in the culture and more or less self-consciously link those to their film.

Today, in press junkets directors can feed the same talking points to reporters over and over again. An example I discuss in the forthcoming Poetics of Cinema is the way that Chaos theory has been invoked to give weight to films centering on networks and fortuitous connections. As I read interview after interview, I thought I’d scream if I encountered one more reference to a butterfly flapping its wings.

More recently, Paul Greengrass gave critics some help when he suggested that the jumpy cutting and spasmodic handheld camera of The Bourne Ultimatum suggested the protagonist’s subjective point of view–presumably, Jason’s psychological disorientation and frantic scanning of his surroundings. I expressed skepticism about this on an earlier blog entry, Anne Thompson replied on her blog, and I returned to the subject again. Any director’s statement of purpose is interesting in itself, but it should be assessed in relation to the evidence we detect onscreen.

Another recent instance: the new Taschen book on Michael Mann. The luscious pictures, mainly from Mann’s archive, are the volume’s raison d’etre, but the filmmaker seems to have placed unusual demands on the text. F. X. Feeney writes:

An earlier version of this book completed by another writer attempted (in a spirit of sincere praise) to treat Mann’s films as reactions against film traditions, as subversions of genre. This fetched a rebuke from Mann: “It’s irrelevant and neither accurate nor authentic to compare my films to other films because they don’t proceed from genre conventions and then deviate from those conventions. They proceed from life. For better or worse, what I’ve seen and heard and learned on my own is the origin of this material. Maybe the film medium by nature spawns conventions, because we all built on what’s gone before, but the content and themes of my films are not facile and derivative. They are drawn from life experience.” (16)

We have to wonder if Mann’s objection played a role in eliminating the earlier writer’s version. If that happened, it’s an unusually strong instance of a director’s holding sway over critical commentary. (17)

In the text we have, Feeney provides a chronological account of Mann’s career: plot synopses, thematic commentary, production background. There’s no discussion of broader historical trends, such as the migration of TV directors into film, the creative options available in 1980s-1990s Hollywood, the development of self-conscious pictorialism in modern film, the possibility of genre films becoming art-films or prestige pictures, or the changes in media culture or American society. All of these lines of inquiry would require comparing Mann with other filmmakers. It remains for other writers, perhaps without the director’s cooperation, to put Mann’s achievement into such contexts.

It’s always vital to listen to filmmakers, but we shouldn’t limit our analysis to what they highlight. We can detect things that they didn’t deliberately put into their films, and we can sometimes find traces of things they don’t know they know. For example, virtually no director has explained in detail his or her preferred mechanics for staging a scene, indicating choices about blocking, entrances and exits, actors’ business, and the like. Such craft skills are presumably so intuitive that they aren’t easy to spell out. Often we must reconstruct the director’s intuitive purposes from the regularities of what we find onscreen. (For examples, see this site here, here, and here.) And it doesn’t hurt, especially in this age of hype, to be a little skeptical and pursue what we think is interesting, whether or not a director has flagged it as worth noticing.

(1) Macdonald, “Gertrud,” Esquire (December 1965), 86.

(2) Quoted in Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, ed. Jonathan Rosenbaum, This is Orson Welles (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 21).

(3) Such would seem to be the case of the close-up, which of course is found very early in film history. But Griffith’s idea of a close-up may not correspond to ours. More on this in a later blog, perhaps.

(4) I give an overview of this rich body of research in Chapter 5 of On the History of Film Style. See also various entries in the Encyclopedia of Early Cinema, ed. Richard Abel (New York: Routledge, 2005).

(5) The most detailed argument for this view I know is Paisley Livingston’s book Art and Intention: A Philosophical Study.

(6) “William Wyler, or the Jansenist of Directing,” in Bazin at Work: Major Essays and Reviews from the Forties and Fifties, ed. Bert Cardullo (New York: Routledge, 1997), 8.

(7) Orson Welles: A Critical View, trans. Jonathan Rosenbaum (New York: Harper and Row, 1978) 80).

(8) Toland, “Realism for Citizen Kane,” American Cinematographer 22, 2 (February 1941), 54, 80.

(9) See the discussion in Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), 345-349.

(10) Toland, “How I Broke the Rules in Citizen Kane,” Popular Photography (June 1941), 55, 90-91.

(11) “Orson Welles: Once a Child Prodigy, He Has Never Quite Grown Up,” Life (May 26, 1941), 110-111.

(12) Wyler, “No Magic Wand,” The Screen Writer (February 1947), 10.

(13) Peter Bogdanovich was to my knowledge the first person to publish some of this information; see “The Kane Mutiny,” Esquire 77, 4 (October 1972), 99-105, 180-90.

(14) Toland, “Realism,” 80.

(15) “Chabrol Talks to Rui Noguera and Nicoletta Zalaffi,” Sight and Sound 40, 1 (Winter 1970-1971), 6.

(16) F. X. Feeney, Michael Mann (Cologne: Taschen, 2006), 21.

(17) Mann’s reasoning puzzles me. He insists that his films can’t be compared to others along any dimensions, especially thematic ones. Yet in saying that his films are lifelike, he suggests that other films aren’t as realistic as his. Moreover, what about comparisons on grounds of technique, surely one of the most striking and admired features of Mann’s work? For reasons that are obscure, the director discourages any critical consideration of style; Feeney tells us that Mann hates the very word (p. 20).

Ad in Wid’s Year Book 1918.

PS: 15 October: I’ve received a clarification from Paul Duncan, editor of F. X. Feeney’s Michael Mann book for Taschen. He expresses general agreement with my suggestions about how directors shape the uptake of their work, but he explains that the Mann book isn’t an instance of it. Here are the comments bearing on my blog entry.

In reply to my suggestion of other avenues to explore about Mann’s career:

In fairness to F.X. Feeney, he only had 25,000 words to cover Mann’s career, and all the subjects you write about are really outside the scope of the book. It sounds as though these are subjects that you would like to explore, and I can’t wait to read them in a future book or blog.

As for whether Mann exercised some control over the book’s final form, which I float as one possible explanation for its compass:

First, you speculate whether Mann caused the first version of the book to be scrapped, i.e. He exerted editorial control/censorship over the book. This is not the case, and if it was, do you think that he would have allowed F.X. to write that in the published version of the book?

In Note 17 appended to Feeney’s quote, you write: “Yet in saying that his films are lifelike, he suggests that other films aren’t as realistic as his.” If you had continued Mann’s quote, you would have reported the following: “I don’t look at the excellent French director Jean-Pierre Melville to decide how to tell the story in Thief. I meet thieves. And I guarantee you the reason Melville’s Le Samourai 1967) has authenticity, the reason Raoul Walsh’s White Heat (1949) has authenticity, is because those film-makers knew thieves, too.” I do not see any evidence here that Mann suggests that his films are more lifelike than other directors’. Only that his films stem from life like other films stem from life.

Also, in Note 17, you write: “For reasons that are obscure, the director discourages any critical consideration of style; Feeney tells us that Mann hates the very word (p. 20).” The reason Mann hates the word “style”—and I apologize for not making this clear in the book—is because after producing the Miami Vice TV show, he was forever referred to as a stylist, and the “style” of the show was all anybody ever talked about. The implication was that Mann is a director of style without substance. Subsequently, Mann has been very wary of the word, and discussion of it, because it puts undue weight on one aspect of his work.

Finally, I would like to explain a little of the working method with Mann on the book. The book was researched and written during rehearsal, filming and editing of Collateral. F.X. wrote the text and was given full access to everything that Mann had said in interviews. Mann then read and annotated the text, and this was discussed face-to-face with F.X. Most of these annotations were of a factual nature, correcting dates, being precise about the sequence of events, and to correct misinterpretations of his comments in previous interviews. However, they would also bring up new comments from Mann about his work. F.X. then rewrote some texts to include Mann’s comments, and then F.X. wrote his replies. In this way, the book became more of a dialogue between Mann and F.X. and is stronger for it I feel. So, in this case, the filmmaker did not get the last word.

I thank Paul for his clarifications, which should be of interest to all the book’s readers. On only two matters do we disagree.

First, Feeney’s book achieves what it set out to achieve, and it deserves credit for giving us valuable information about Mann in a clear, pungent style. And no one expects a Taschen book to be an in-depth monograph covering all aspects of a director’s career. But I still think that length limits don’t prevent an author from raising the contextual issues I mention. Many articles manage to address matters that go beyond the sort of career survey that Feeney provides, so there are ways to sketch such issues in an abbreviated way. I inferred, erroneously, that the choice not to tackle them could have been related to Mann’s own views on the comparative dimension that such issues tend to rely on.

Secondly, a minor matter: The fact that Mann can invoke Melville and Walsh on films about thieves suggests that a comparative perspective is valuable; he’s including himself in the company of directors who know their subjects from life, in explicit contrast to those who don’t. I didn’t include the extra sentences because I thought that they simply provided further signs of the contradiction I found in Mann’s own position—that his films can’t be compared to other directors’ works.