Archive for the 'Directors: Hawks' Category

Off-center 2: This one in the corner pocket

DB here, again:

We got a keen response to my entry on widescreen composition in Mad Max: Fury Road. Thanks! So it seemed worthwhile to look at composition in the older format of 4:3, good old 1.33:1–or rather, in sound cinema, 1.37: 1.

The problem for filmmakers in CinemaScope and other very wide processes is handling human bodies in conversations and other encounters (such as stomping somebody’s butt in an an action scene). You can more or less center the figures, and have all that extra space wasted. Or you can find ways to spread them out across the frame, which can lead to problems of guiding the viewer’s eye to the main points. If humans were lizards or Chevy Impalas, our bodies would fit the frame nicely, but as mostly vertical creatures, we aren’t well suited for the wide format. I suppose that’s why a lot of painted and photographed portraits are vertical.

By contrast, the squarer 4:3 frame is pretty well-suited to the human body. Since feet and legs aren’t usually as expressive as the upper part of the body, you can exclude the lower reaches and fit the rest of the torso snugly into the rectangle. That way you can get a lot of mileage out of faces, hands and arms. The classic filmmakers, I think, found ingenious ways to quietly and gracefully fill the frame while letting the actors act with body parts.

Since I’m watching (and rewatching) a fair number of Forties films these days, I’ll draw most of my examples from them. after a brief glance backward. I hope to suggest some creative choices that filmmakers might consider today, even though nearly everybody works in ratios wider than 4:3. I’ll also remind us that although the central area of the frame remains crucial, shifts away from it and back to it can yield a powerful pictorial dynamism.

Movies on the margins

Early years of silent cinema often featured bright, edge-to-edge imagery, and occasionally filmmakers put important story elements on the sides or in the corners. Louis Feuillade wasn’t hesitant about yanking our attention to an upper corner when a bell summons Moche in Fantômas (1913). A famous scene in Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912) shows Griffith trying something trickier. He divides our attention by having the Snapper Kid’s puff of cigarette smoke burst into the frame just as the rival gangster is doping the Little Lady’s drink. She doesn’t notice either event, as she’s distracted by the picture the thug has shown her, but there’s a chance we miss the doping because of the abrupt entry of the smoke.

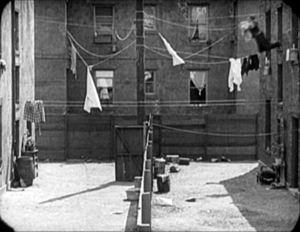

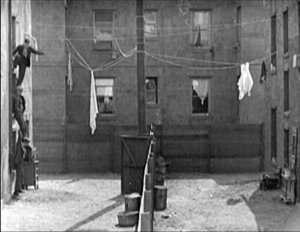

In Keaton’s maniacally geometrical Neighbors (1920), the backyard scenes make bold (and hilarious) use of the upper zones. Buster and the woman he loves try to communicate three floors up. Early on we see him leaning on the fence pining for her, while she stands on the balcony in the upper right. Later, he’ll escape from her house on a clothesline stretched across the yard. At the climax, he stacks up two friends to carry him up to her window.

Thankfully, the Keaton set from Masters of Cinema preserves some of the full original frames, complete with the curved corners seen up top. It’s also important to appreciate that in those days there was no reflex viewing, and so the DP couldn’t see exactly what the lens was getting. Framing these complex compositions required delicate judgment and plenty of experience.

Later filmmakers mostly stayed away from corners and edges. You couldn’t be sure that things put there would register on different image platforms. When films were destined chiefly for theatres, you couldn’t be absolutely sure that local screens would be masked correctly. Many projectors had a hot spot as well, rendering off-center items less bright. And any film transferred to 16mm (a strong market from the 1920s on) might be cropped somewhat. Accordingly, one trend in 1920s and 1930s cinematography was to darken the sides and edges a bit, acknowledging that the brighter central zone was more worth concentrating on.

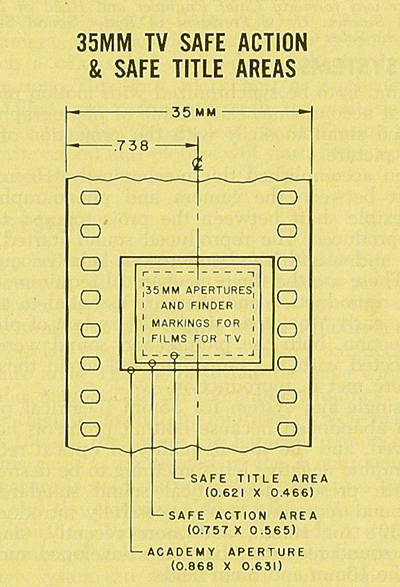

That tactic came in handy with the emergence of television, which established a “safe area” within the film frame for video transmission. TV cropped films quite considerably; cinematographers were advised in 1950 that

All main action should be held within about two-thirds of the picture. This prevents cut-off and tube edge distortion in television home receivers.

Older readers will remember how small and bulging those early CRT screens were.

By 1960, when it was evident that most films would eventually appear on TV, DP’s and engineers established the “safe areas” for both titles and story action. (See diagram surmounting this section.) Within the camera’s aperture area, which wouldn’t be fully shown on screen, the safe action area determined what would be seen in 35mm projection. “All significant action should take place within this portion of the frame,” says the American Cinematographer Manual.

Studio contracts required that TV screenings had to retain all credit titles, without chopping off anything. This is why credit sequences of widescreen films appear in widescreen even in cropped prints. So the safe title area was marked as what would be seen on a standard home TV monitor. If you do the math, the safe title area is indeed 67.7 % of the safe action area.

These framing constraints, etched on camera viewfinders, would certainly inhibit filmmakers from framing on the edges or the corners of the film shot. And when we see video versions of films from the 1.37 era (and frames like mine coming up) we have to recall that there was a bit more all around the edges than we have now.

All-over framing, and acting

Yet before TV, filmmakers in the 40s did exploit off-center zones in various ways. Often the tactic involved actors’ hands–crucial performance tools that become compositional factors. In His Girl Friday (1940), Walter Burns commands his frame centrally, yet when he makes his imperious gesture (“Get out!”) Hawks and DP Joseph Walker (genius) have left just enough room for the left arm to strike a new diagonal.

The framing of a long take in The Walls of Jericho (1948) lets Kirk Douglas steal a scene from Linda Darnell. As she pumps him for information, his hand sneaks out of frame to snatch bits of food from the buffet.

As the camera backs up, John Stahl and Arthur Miller (another genius) give us a chance to watch Kirk’s fingers hovering over the buffet. When Linda stops him with a frown, he shrugs, so to speak, with his hands. (A nice little piece of hand jive.)

The urge to work off-center is still more evident in films that exploit vigorous depth staging and deep-focus cinematography. Dynamic depth was a hallmark of 1940s American studio cinematography. If you’re going to have a strong foreground, you will probably put that element off to one side and balance it with something further back. This tendency is likely to empty out the geometrical center of the shot, especially if only two characters are involved. In addition, 1940s depth techniques often relied on high or low angles, and these framings are likely to make corner areas more significant. Here are examples from My Foolish Heart (1950): a big-head foreground typical of the period, and a slightly high angle that yields a diagonal composition.

Things can get pretty baroque. For Another Part of the Forest (1948), a prequel to The Little Foxes (1941), Michael Gordon carried Wyler’s depth style somewhat further. The Hubbard mansion has a huge terrace and a big parlor. Using the very top and very bottom of the frame, a sort of Advent-calendar framing allows Gordon to chart Ben’s hostile takeover of the household, replacing the patriarch Marcus at the climax. The fearsome Regina appears in the upper right window of the first frame, the lower doorway of the second.

In group scenes, several Forties directors like to crowd in faces, arms, and hands, all spread out in depth. I’ve analyzed this tendency in Panic in the Streets (1950), but we see it in Another Part of the Forest too. Again, character movement can reveal peripheral elements of the drama.

At the dinner, Birdie innocently thanks Ben for trying to help her family with their money problems and bolts from the room, going out behind Ben’s back. The reframing brings in at the left margin a minor character, a musician hired to entertain for the evening. But in a later phase of the scene he will–still in the distance–protest Marcus’s cruelty, so this shot primes him for his future role.

At one high point, the center area is emptied out boldly and the corners get a real workout. On the staircase, the callow son Oscar begs Marcus for money to enable him to run off with his girlfriend. (As in Little Foxes, the family staircase is very important–as it is in Lillian Hellman’s original plays.) Ben watches warily from the bottom frame edge. Nobody occupies the geomentrical center.

Later, on the same staircase, Ben steps up to confront his father while Regina approaches. It’s an odd confrontation, though, because Ben is perched in the left corner, mostly turned from us and handily edge-lit. Marcus turns, jammed into the upper right. Goaded by Ben’s taunts, he slaps Ben hard. Here’s the brief extract.

The key action takes place on the fringes of the frame, while the lower center is saved for Regina’s reaction–for once, a more or less normal human one. Even allowing for the cropping induced by the video safe-title area, this is pretty intense staging.

The corners can be activated in less flagrant ways. Take this scene from My Foolish Heart. Eloise has learned that her lover has been killed in air maneuvers. Pregnant but unmarried, she goes to a dance, where an old flame, Lew asks her to go on a drive. They park by the ocean, and she succumbs to him. Here’s the sequence as directed by Mark Robson and shot by Lee Garmes (another genius).

In the fairly conventional shot/ reverse-shot, the lower left corner is primed by Eloise’s looking down at the water and Lew’s hand stealing around her.

Later, when Lew pulls her close, (a) we can’t see her; (b) his expression doesn’t change and is only partly visible; so that (c) his emotion is registered by the passionate twist of his grip on her shoulder. Lew’s hand comes out from the corner pocket.

Perhaps Eloise is recalling another piece of hand jive, this time from her lost love.

For many directors, then, every zone of the screen could be used, thanks to the good old 4:3 ratio. It’s body-friendly, human-sized, and can be packed with action, big or small.

Mabuse directs

In other entries (here and here) I’ve mentioned one of the supreme masters of off-center framing, Fritz Lang. Superimpose these two frames and watch Kriemhilde point to the atomic apple in Cloak and Dagger (1946).

From the very start of Ministry of Fear (1944), the visual field comes alive with pouches, crannies, and bolt-holes. The first image of the film is a clock, but when the credits end the camera pulls back and tucks it into the corner as the asylum superintendant enters. (The shot is at the end of today’s entry.) Here and elsewhere, Lang uses slight high angles to create diagonals and corner-based compositions.

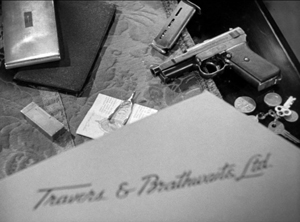

In the course of the film, pistols circulate. Neale lifts one from Mrs. Bellane (strongly primed, upper left), keeps her from appropriating it (lower center), and secures it nuzzling his left knee (lower right).

Later, Neale’s POV primes the placement of a pistol on the desktop (naturally, off-center), so that we’re trained to spot it in a more distant shot, perilously close to the hand of the treacherous Willi.

Amid so many through-composed frames, an abrupt reframing calls us to attention. Unlike Hawks and Walker’s handling of Walter in His Girl Friday, Lang and his DP Henry Sharp (great name for a DP, like Theodore Sparkuhl and Frank Planer) gives things a sharp snap when Willi raises his hand.

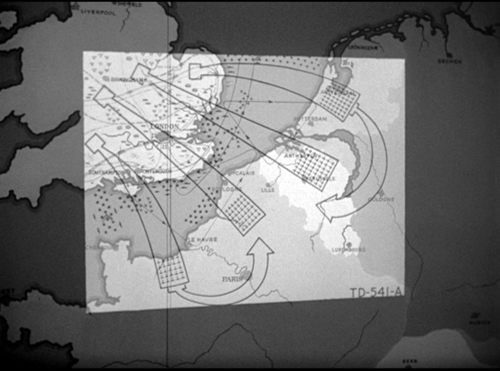

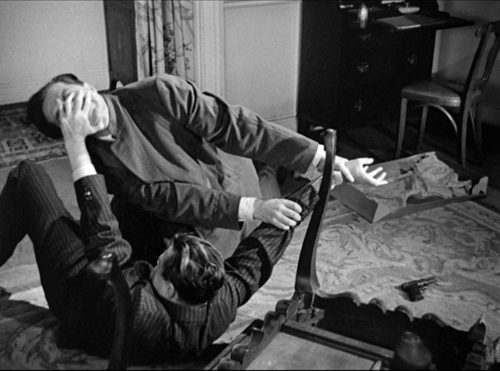

Lang drew all his images in advance himself, not trusting the task to a storyboarder. Avoiding the flashy deep-focus of Wyler and company, he created a sober pictorial flow that can calmly swirl information into any area of the frame. It’s hard not to see the stolen attack maps, surmounting today’s entry, as laying bare Lang’s centripetal vectors of movement. No wonder in the second frame up top, as Willi and Neale struggle in a wrenching diagonal mimicking the map’s arrows, that damn pistol strays off on its own.

Sometimes film technology improves over time. For instance, digital cinema today is better in many respects than it was in 1999. But not all changes are for the better. The arrival of widescreen cinema was also a loss. Changing the proportions of the frame blocked some of the creative options that had been explored in the 4:3 format. Occasionally, those options could be modified for CinemaScope and other wide-image formats; I trace some examples in this video lecture. But the open-sided framings in most widescreen films today suggest that most filmmakers haven’t explored the wide format to the degree that classical directors did with the squarish one.

More generally, it’s worth remembering that the film frame is a basic tool, creating not only a window on a three-dimensional scene but also a two-dimensional surface that requires composition–either standardized or more novel. Instead of being a dead-on target, the center can be an axis around which pictorial forces push and pull, drift away and bounce around. After all, we’re talking about moving pictures.

Thanks to Paul Rayton, movie tech guru, for information on 16mm cropping.

My image of the safe areas and the second quotation about them is taken from American Cinematographer Manual 1st ed., ed. Joseph C. Mascelli (Hollywood: ASC, 1960), 329-331. The older quotation about cropping for television comes from American Cinematographer Handbook and Reference Guide 7th ed., ed. Jackson J. Rose (Hollywood: ASC, 1950), 210.

I hope you noticed that I admirably refrained from quoting Lang, who famously said that CinemaScope was good only for…well, you can finish it. Of course he says it in Godard’s Contempt (1963), but he told Peter Bogdanovich that he agreed.

[In ‘Scope] it was very hard to show somebody standing at a table, because either you couldn’t show the table or the person had to be back too far. And you had empty spaces on both sides which you had to fill with something. When you have two people you can fill it up with walking around, taking something someplace, so on. But when you have only one person, there’s a big head and right and left you have nothing (Who the Devil Made It (Knopf, 1997), 224).

For more on the stylistics and technology of depth in 1940s American film, see The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (Columbia University Press, 1985), which Kristin and I wrote with Janet Staiger, Chapter 27, and my On the History of Film Style (Harvard University Press, 1997), Chapter 6. Many blog entries on this site are relevant to today’s post; search “deep-focus cinematography” and “depth staging.” If you want just one for a quick summary, try “Problems, problems: Wyler’s workarounds.” Some of the issues discussed here, about densely packing the frame, are considered more generally in “You are my density,” which includes an analysis of a scene in Lang’s Hangmen Also Die (1943).

Ministry of Fear (1944).

The Getting of rhythm: Room at the bottom

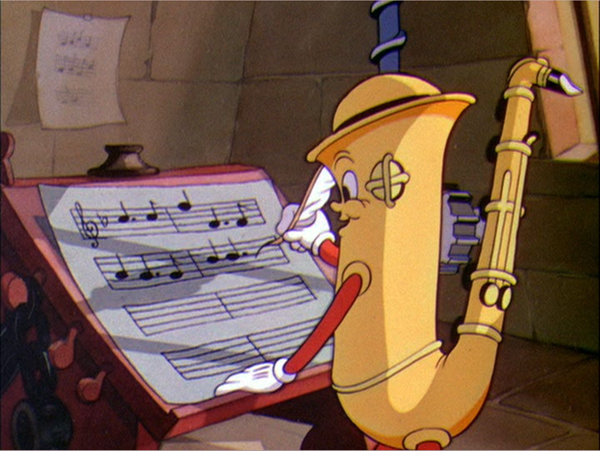

Music Land (Disney, 1935).

DB here:

“The great directors, I’ve learned, have a great sense of rhythm.” So says Alexandre Desplat, who’s again earned two Oscar nominations in the same year (for The Imitation Game and The Grand Budapest Hotel). The statement sounds true but vague. Musicians and musicologists have a firm sense of what the term rhythm means, but how can we understand it in relation to movies?

Well, surely it refers, at least, to the rhythm of the music we hear in the film. But we usually think there’s more involved. There’s rhythm in the movement on the screen. The people and things we see can be infused with a beat and tempo and pace. (Critics of the 1920s considered Chaplin a dancer, like Nijinsky.) There’s a rhythm to the combination of images too, as everybody who’s tried film editing knows. And we think that the story can be told in a way that has a distinctive pace–narrative rhythm, we sometimes call it. But how do these components work together to create an overall rhythm for the film?

When synchronized sound recording entered movies, critics and filmmakers worried a lot about this problem. Filmmakers who had mastered visual storytelling in the silent era had to figure out how to merge spoken language, music, and sound effects with the flow of images. The lazy solution was simply to shoot plays, filling the scenes with dialogue. But both audiences and critics missed the dynamism of silent films. Talkies were too talky.

The opposite solution, to eliminate words as much as possible and simply use music and sound effects, was of limited value. After all, silent film needed the written language of intertitles to make the story clear; why give up the advantages of spoken language? But how then to integrate image and sound into something that engaged the audience–not only through the film’s story but also, perhaps more deeply, through that elusive quality called rhythm?

Today this debate may seem sterile. We think filmmakers have solved the problem. Maybe they have, collectively, but each one faces it at every moment. How do you blend movement, music, pictorial composition, sound effects, and dialogue to create an overall pace that will benefit your movie? No single recipe will work. The rhythm of the Coen brothers’ Raising Arizona is very different from that of No Country for Old Men. Both Gone Girl and Non-Stop are thrillers, but Fincher’s pacing is far more deliberate and understated than Collet-Serra’s; yet both take hold of us.

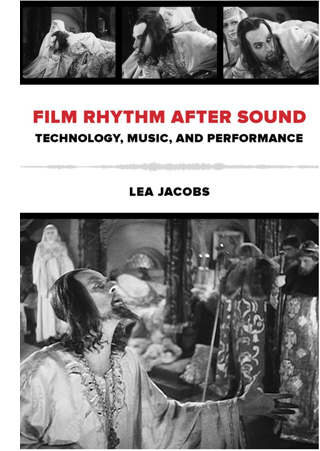

Filmmakers solve the problem of rhythm in practice, often brilliantly. Those of us who want to understand how films work, and work upon us, want to get specific and explicit. What is this thing called cinematic rhythm? What contributes to it? Can we analyze it and explain its grip? Very few scholars have tackled these questions; they’re hard. In her new book, Film Rhythm after Sound: Technology, Music, and Performance, our friend and colleague Lea Jacobs takes us quite a ways toward some answers.

Mickey-mousing redux

Lea starts from the assumption that the debates of the early 1930s are still relevant. So she looks at some much-praised examples of sound/image integration: the musicals of Mamoulian and Lubitsch and the cartoons from the Disney studio. She studies these paradigm cases more closely than anyone has before. She also goes beyond them to consider the theory and practice of Eisenstein (a big admirer of Disney) and the handling of dialogue in Howard Hawks’ work from The Dawn Patrol (1930) to Twentieth Century (1934).

Central to Lea’s inquiry is the notion of synchronization. How can distinct moments in the image flow, the sound flow, and the narrative action be pinched together, like the toothpick pinning the ingredients in a sandwich? One answer is to rehabilitate the old idea of mickey-mousing. Mickey-mousing makes the patterning of the sound match, in some way, the pattern of onscreen action. Mickey-mousing has had a bad press, but Lea shows that if we look at it afresh, it offer a solid point of departure for thinking about rhythm.

Eisenstein develops the idea of sync, in a fresh but still general way, in his notion of “brickwork” structure–the non-coincidence of image and sound, like the staggered array of bricks in a wall. That is, your cut shouldn’t come on the beat (are you listening, music-video directors?). Save your sync until it can have maximum impact, ideally through accenting some action in the image and maybe a high point in your drama. This is a step beyond the duality synchronous/asynchronous sound that was floated in the early 1930s. Eisenstein shows how all the different lines of pictorial and auditory movement can be woven in a flow that will create various degrees of emphasis. In this “wickerwork” pattern (another of his metaphors), actor movement might coincide with a melodic run rather than a beat, and the cut might accentuate a line of dialogue while the music subsides. Or instead of Hollywood’s underscoring, the music might be abnormally loud, doubling and clashing with dialogue in a “Godardian” manner. At certain moments, several accents in these lines could hit simultaneously. Just as important are the moments when the imagery and the mix get thinned out so that a single element–a word, a chord, a gesture–is isolated.

The key example comes from Ivan the Terrible, Part I, in which the ailing tsar asks the Boyars to kiss the cross in allegiance to his baby son Dmitri. In unprecedented detail, Lea tracks how the melody, meter, motifs, orchestration, and dynamics of the music fluctuate in relation to staging, line readings, and narrative developments. In a passage lasting only six minutes, she shows how–as so often happens–Eisenstein’s practice outruns his theory and creates a rich audiovisual texture at an almost microscopic level.

The key example comes from Ivan the Terrible, Part I, in which the ailing tsar asks the Boyars to kiss the cross in allegiance to his baby son Dmitri. In unprecedented detail, Lea tracks how the melody, meter, motifs, orchestration, and dynamics of the music fluctuate in relation to staging, line readings, and narrative developments. In a passage lasting only six minutes, she shows how–as so often happens–Eisenstein’s practice outruns his theory and creates a rich audiovisual texture at an almost microscopic level.

Rhythm is constructed frame to frame, sync point to sync point, and involves very small durations of a half second or a quarter second. This proposition may seem obvious to anyone who has been involved in editing or scoring film music. Classical Hollywood click tracks measured tempi to fractions of a frame, as defined by the sprocket holes, and there are clear indications that composers and editors haggled over durations of five or six frames.

This urge to “think small” and study the finest grain of image and sound carries through Lea’s analysis of rhythm in Disney cartoons. Some have accused Eisenstein’s Ivan of being a live-action cartoon, and there’s no hiding either the old man’s admiration for Disney or his belief that cinema was capable of highly “engineered” effects. Still, music and its mickey-mousing possibilities determine animated films even more strongly than live-action ones. Lea takes Disney’s early sound films as experiments in synchronization.

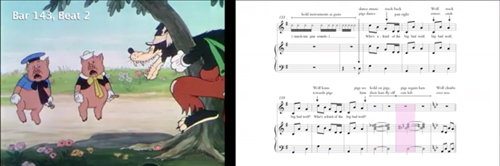

Early sound cartoons are sometimes characterized as “prisoners of the beat” because they create cycles of motion that are lined up with the musical meter. Lea traces how Disney animation became more fluid and flexible, syncing more around sound events than around rigid beats. She illustrates her case with analyses of Hell’s Bells (1929), The Three Little Pigs (1933), and Playful Pluto (1934). The last two are widely regarded as classic Silly Symphonies, and she sheds fresh light on them through the sort of micro-analysis brought to bear on Ivan.

She shows how sections gain a fast or slow tempo through the interaction of many factors, of which shot length is only one. In particular, Disney directors could change pace through a tool that Eisenstein didn’t have: altering the frame rate of animation. Normal animation is “on twos”; each drawn frame is photographed twice, to last for two film frames. Many stretches of the Disney cartoons are on twos, but sometimes, to create vivid sync points, the filmmakers go “on ones,” allotting one frame for each drawing. This is more expensive and time-consuming, but it allows for the sort of fine control of pace that we find in The Three Little Pigs. There the Wolf launches into “a jazzy, up-tempo gallop” that accelerates the danger bearing down on the pigs. In a similar way, Playful Pluto creates variety by “matching movement to different fractions of the beat and establishing differential rates of movement within the shot.” Imagineering, for sure.

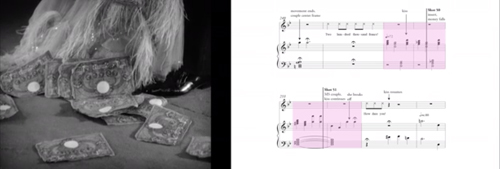

How to convey this fine-grained analysis on the page? Lea uses the familiar tactics of presentation: verbal description, musical scores, and frame enlargements. But she goes farther. At great effort and expense, she has constructed analyses of key passages as video clips, with the film scene running in interlock with a highlighting bar that shifts across the score. Annotations on the score mark actions and sync points. These analyses are designed to be watched as you read along in the book. You’ll see some frame grabs in this entry, but to watch them simply go here, select the Audio/Video tab, and choose what you want to see from the menu. This is a real step forward for film scholarship, and the University of California Press should be congratulated for helping her take it. Why shouldn’t every film book hereafter come garlanded with clips?

No age for rhythm

Monte Carlo (1930).

Okay, you might say. Rhythm is of concern to top-down audiovisual masters like Eisenstein and Disney. But there are other notions of film as art–for instance, that performance is central to its storytelling. Lea shows that, again, early sound film explored a more open and porous integration of music and image. Ernst Lubitsch, as Kristin has shown, was one of the masters of image-based cinema in the silent era. Yet as soon as sound came in, he was exploring how to blend music with the mercurial repartee and attitudes of his sophisticated characters. Rouben Mamoulian, who had indulged in sync experiments in the theatre, contributed as well to a broader trend that gave music a central role in structuring scenes.

The result wasn’t exactly “musicals” as we usually understand them, although there might be song numbers; instead, the music worked its way into the crannies of the scenes–pauses in the dialogue, moments when characters cross a courtyard or boudoir. Thanks to post-synchronization (music performed after the film was shot and cut) and sync-to-playback (prerecorded music played on the set during performance), early sound films could boast a tight rhythmic bond of performance style and musical accompaniment. That created a sort of cinematic operetta, one no longer bound to a theatrical space. In “Isn’t It Romantic?” in Mamoulian’s Love Me Tonight (1932), a song begun in a tailor’s shop is passed along through Paris, onto a train, to the open road (soldiers march to it), and eventually to a gypsy campfire, where the heroine hears it from her balcony.

Most historians find strong similarities between such passages in Love Me Tonight and scenes in Lubitsch’s Monte Carlo (1930), but Lea contrasts them. She argues that Mamoulian’s film is more like early Disney in syncing music one-to-one with figure movement and camera movement. Lubitsch (although working earlier than Mamoulian) is interested in synchronization at another level, linking musical segments to dramatically coherent parts and wholes. She shows how one sequence in Monte Carlo accelerates its techniques to culminate in a patter song, creating a curve of rhythmic interest that sculpts the scene’s overall shape. Significantly, as in the famous choo-choo “Beyond the Blue Horizon” number, the song uses noises rather than music to launch its rhythmic arc.

The case-study method leads Lea to some generalizations too, as in her survey of manners of dialogue underscoring. This section of the books seems to me especially rich, because it shows how tactics of underscoring associated with the 1930s “symphonic” scores were already available, at least sketchily, in the early years of sound. At the same time, she’s able to distinguish some creative options, such as the conversion of patter songs to a more conversational tempo, that seem very distinctive of these early sound films and not their successors. She and other scholars can now build upon her survey to track a variety of styles of dialogue underscoring.

Okay, again, but these early musicals are still very pre-structured, you might say. What about movies that don’t rely on music so much and that give the actors more freedom during shooting?

Okay, again, but these early musicals are still very pre-structured, you might say. What about movies that don’t rely on music so much and that give the actors more freedom during shooting?

Enter Howard Hawks.

The book’s last in-depth analysis is devoted to probably the trickiest aspect of the whole problem: rhythm in speech, performance, and narrative. Lea points out that sound film acting required quite exact timing of pauses, glances, gestures, movement around the set, and deployment of hand props–probably tighter timing than in the silent era, with its shorter takes and greater scene dissection. (Consider how often a silent film gives us a close-up of a hand picking up something; in talkies, picking up something seldom gets that emphasis, so that the actor has to integrate the action into the flow of the full shot.) In sound filming, the shooting of the scene and the actor’s performance choices limited what an editor could do to slow it down or speed it up.

Hawks is a notoriously difficult director to analyze because he doesn’t have an obvious signature style at the visual level. His conception of cinematic art relied upon his players. He famously developed his scenes slowly, letting actors improvise, asking screenwriters to recast the scene, and working out the blocking gradually. In this actor-centered cinema, we’re often told, a lot of the Hawksian tang comes from overlapping dialogue. Lea points out, though, that overlapping dialogue was already in wide use on the theatre stage and Hawks was comparatively late in importing it to film. His earliest 1930s experiments don’t owe much to it, largely because early sound technology couldn’t discriminate voices very well. Lea breaks new ground in showing other ways in which speech patterns, regulated through rhythm as well as pitch and timbre, not only contribute to characterization but supply that zesty bounce we associate with the Hawksian world.

His tactics include shifting actors around the set, letting background and foreground sound alternate in clarity, and shortening scenes. Lea goes on to show how these and other options led Hawks to create the “tough talk delivered in a tough way” that became one of his hallmarks. By measuring the length of actors’ lines in seconds and fractions of a second, she’s able to track a subtle orchestration of voices–long speeches delivered fast (or slow), short speeches delivered slow (or fast), and many varieties in between, all interwoven. Overlapping comes in occasionally, as icing on the cake. When it does, especially in Twentieth Century, Lea is ready to specify it, showing how syllables and phonemes are stepped on or cut off.

Now the control freaks aren’t the directors, the Eisensteins and Lubitsches, but the actors. Working together, they plan their lines, expressions, and gestures down to the word. They make their own music. Hawks, says Lea, gives us rhythm “without benefit of a beat.”

Film Rhythm after Sound is a breakthrough in showing how narrative cinema masters time in its finest grain. We’re used to talking about scenes, shots, and lines of dialogue. Lea has taken us into the nano-worlds of a film: frames and parts of frames, fractions of seconds, phonemes. As Richard Feynman once said of atomic particles, “There’s plenty of room at the bottom.” Of course Lea doesn’t overlook characterization, plot dynamics, themes, and other familiar furniture of criticism. But she shows how our moment-by-moment experience depends on the sensuous particulars that escape our notice as the movie whisks past us. We can’t detect these micro-stylistics on the fly. Yet they are there, working on us, powerfully engaging our senses. Film criticism, informed by historical research, seldom attains this book’s level of delicacy. Analyzing a movie’s soundtrack will not be the same again.

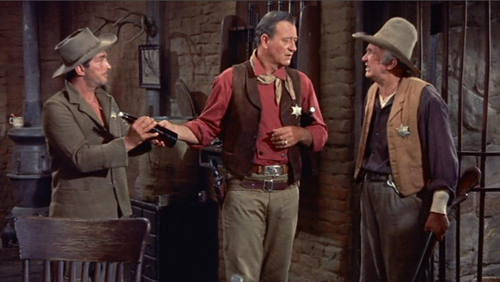

The Tao of RIO BRAVO; or, A Yakky Way of Knowledge

Too long has this scrolling site ignored the Sacred Text. In a gesture of penance, I return to the true path. Like all Sacred Texts, this one attracts worshippers in different degrees: the Seekers, the Initiates, the Adepts, and the Exegetes. There are Heretics too. Today, I wish merely to introduce you, who may not yet be even a Seeker, to the serenity of The Way.

The Word, in plenty

Seekers who have become Initiates agree: Their blinding moment of conversion came when they realized that the words of the Sacred Text speak to all times, all places.

Other Sacred Texts dispense a few trinkets of wisdom (“I have a bad feeling about this.” “We’re gonna need a bigger boat.” “Show me the money.”) These are tag lines, sound bites, not poetic glimpses of glory. Uniquely and universally, passages in our Text raise the spirit and cast out doubt and despair. But far from being otherworldly, they carry practical wisdom and illuminate every situation. What crisis in your life, brother or sister, would not be piercingly clarified if you were able to utter one of these lines?

It’s nice to see a smart kid for a change.

I’d say he’s so good he doesn’t feel he has to prove it.

That’s what I’d do if I were the kind of girl you think I am.

Sorry don’t get it done, Dude.

You look a little used.

Aw, I’m not gonna hurt him.

If I’m gonna get shot at, I might as well get paid for it.

Let’s take a turn around the town.

I’m glad we tried it a second time. It’s better when two people do it.

Borachone talking big.

You’d better go easy on that stuff.

Don’t set yourself up as being so special. You’d think you invented the hangover.

Aw, hell, what’s the difference? We’d all be dead by then.

Nobody’s run in here./ We’ll remember you said that.

Found yourself another knot-head who don’t know when he’s well off?

A game-legged old man and a drunk. That’s all you got?/ It’s what I’ve got.

Think you’re good enough?

Is he as good as I used to be?/ It’d be pretty close. I’d hate to have to live on the difference.

To become an Initiate, the Seeker must commit these to memory and meditate upon them intently. An Adept will be able to summon them up, half-consciously, in a range of situations–the more far-fetched, the more enlightening. One will always be appropriate.

The Name

Exegetes have pointed out that the figures of light in the Sacred Text do not have the usual names. They are, emblematically, called Stumpy, Dude (aka Borachone), Colorado, Feathers. He Who Is Called Chance is named John T., but even the middle initial is turned into an epithet (“T for Trouble”).

Far from being an accident, the names in the Sacred Text are there to impel the Initate into deeper mysteries. Is, for instance, Stumpy The Elder called Stumpy because of his lameness—always a sign of grace in sacred texts? Because of his inertness (as stiff as a stump)? Or because a tree, even though harvested, retains its attachment to the earth by remaining rooted? Perhaps He Who Is Called Stumpy is “grounded,” as the current saying has it.

The Text is figural, both metonymic and metaphoric. Young Colorado is son of Rocky Ryan from Denver. He Who Is Called Wheeler is a man of wagons. She Who Is Called Feathers wears feathered clothes, but also has a teasing lightness of manner. He Who Is Called Dude constitutes a crux. Is he a “dude,” an Easterner who has come west, or is he a dude because he favors fancy outfits? (See “Raiment,” below.)

The central fact is that in this text, the mystery of naming opens on to the Mystery of Being. Everyone is named something, but many are not named by their name.

Raiment

Once the devout Seeker has sensed the limitless depths of the The Words, the more inquisitive will turn to the images. In the opening scene of the Sacred Text, a largely wordless series of encounters in barrooms, a world is created before our eyes. It is a world of debasement, treachery, and sudden death. A contemporary text called Variety, secular but still enlightening, notes: “…gets off to one of the fastest slam-bang openings on record.”

Exegetes have long praised this eloquent passage. They note that a text so replete with Words benefits from an extended passage of muteness. Not silence, for the almost continuous music attributed to Dmitri Tiomkin provides its own wordless “commentary” on the action. This sordid, barbarous world will be redeemed; those who are left low on the saloon floor will rise three days afterward (note!) to triumph.

Serious study of the Text’s images drives the Adept to note the raiment in which the figures are clothed. The Nemesis Joe Burdette wears a bright cowhide vest, suggesting his animalistic anima. He Who Is Called Dude begins in dirty garments, earns the right to garb himself in splendor, but through weakness of soul he is once more soiled.

She Who Is Called Feathers manifests the most dazzling changes in raiment.

Hers receive commentary within the Text, while the garments of He Who Is Called Chance are noticed only by her.

Those things have big possibilities, but not for you.

Hey, Sheriff, you forgot your pants.

But these may be interpolations by later hands.

Disputed passages

Like all Sacred Texts, this contains stretches that excite puzzled commentary. What, in the opening scene, is Wheeler supposed to “tell his men”? Why so many flying insects at night? Why is He Who Is Called Chance once, and only once, seen awkwardly grappling with his rifle, trying to hold it while he shrugs into his jacket?

There is the curious verbal slippage in the song sung by He Who Is Called Dude. He sings of “My three good companions—my rifle, pony, and me.” To the heathen mind, this is a flagrant error. You can have a rifle and a pony as a companion, but you can’t have you as your companion. Can you?

To doubt the Sacred Text at this point is to underestimate the subtlety of the Authors. Recall that the tale told by the song is a dream (“It’s time for a cowboy to dream“). As in other venerable texts (e.g., Bible, Ramayana), dreams are to be taken as warnings, prophecies, or hints as to the true meaning of the story. And so it proves here. We know that He Who Is Called Dude is a divided man: Borachone and pistolero, drunk and deputy. The singer, as we’ve seen, has an untamed side that bursts out into violence against nearly everyone, including his Savior, He Who Is Called Chance.

Hence the split identity of the rider in the song. He is a me, but he also has a me. And around the bend, waiting for both of them, is another divided figure, a woman called “my sweetheart darling.”

There are Exegetes who would see in this passage the source of another worthy text, Western Redundancy Playhouse Theatre, but exploring that would take us too far afield.

More obvious is the Text’s great cosmic sign: The sun rises and sets on the same horizon.

No further proof is needed of the miraculous nature of this narrative.

Heresies

I do not refer to callow efforts to dishonor the Text (e.g., “I think we need a few more scenes in the jail”). Instead, I mention simply the most important efforts by believers, often Adepts, to sow petty doubts. There is, for instance, the efforts to replace the canonical status of this Text by later, more derivative ones (El Dorado; Rio Lobo). Uneven and fragmentary, they have never achieved widespread recognition of Sacredness. Other heresies claim our text itself is derivative, and one offers the biggest challenge to the devout.

I refer of course to the Heresy of the Spittoon.

In the Genesis section already mentioned, Nemesis Burdette flips a coin into a spittoon, and He Who Is Called Dude, needing to buy drink, stoops to retrieve it from the rancid vessel.

Only the intervention of He Who Is Called Chance saves He Who Is Called Dude from this act of degradation. This passage has a parallel later in the Text, when another nemesis must fish a coin out of a spittoon.

The reversal in power is also a step in the redemption of He Who Is Called Dude.

But Adepts have noticed that in Decision at Sundown, a text attributed to one Budd Boetticher and dated 1957 (the Sacred Text we have is dated 1959), a sheriff refuses to accept the money of the protagonist and drops the coins into a spittoon.

Consider another passage in another Boetticher-signed text of the era, Buchanan Rides Alone (confirmed to be from 1958). Here the protagonist, prosaically named Buchanan, disarms a young gunslinger and drops the boy’s bullets into a spittoon.

The vessel, offscreen below frame, announces its presence by the tinkling sound made by the falling rounds.

Heretics have hinted at plagiarism, especially in the light of a reference in another text of the period, Ride Lonesome (dated February 1959, two months before the appearance of our Sacred Text). Here a nemesis tells of a poster “gun-tacked to every tree and stump (!) between here and Rio Bravo.”

While undeniably puzzling, these correspondences do not point to plagiarism. There may have been an earlier, Ur-version of our Sacred text, that has simply not survived. In moments like these we must put our faith in the Authors.

Recurring formulae

Finally, we must return to the Word. Seeker, Initiate, Adept, Exegete: All acknowledge the Text’s verbal echoes. As with Homer’s wine-dark sea and Vergil’s pious Aeneas, formulaic tags recur in our tale, but with more variation than in classic texts.

Our first business is business.

We have important business …. Me and my friend we make our business alone.

I’ll tell you what I’m a lot better at, Mr. Wheeler. That’s minding my own business.

I figure why is not my business./ You’ve got peculiar ways of choosing what is your business.

You think I’ll ever get to be sheriff?/ Not unless you mind your own business.

As if to signal to the devout the importance of every word, the Text provides its own meta-commentary. As a French exegete has said: “Discourse cleansing discourse, backchat ruling over chatter and chitchat.”

I’ll go outside so you can talk more freely.

I guess I talk too much.

He’ll keep talking till we get out of here.

Can’t you talk plainer than that?

Young Colorado says that Nemesis Nathan Burdett is “talking now” through the Deguelo tune./ I guess we made him talk after all.

Me, I just talk all the time./ You most certainly do./ You’ll get used to that. You’ll have to. Either that, or start talking to me.

Now I’m running out of breath. You talk if you want to.

Like all Sacred Texts, for all this talk of talk, this one knows that the ultimate truth lies beyond words.

Just stop talking. Just let it be.

Good advice.

Before I followed the Way, the spittoon was a spittoon. As I began to learn the Way, the spittoon was more than a spittoon. When I had learned the way, the spittoon was once again a spittoon.

Addendum 15 April 2012: This humble guide to the Text has aroused further passion among Exegetes. Three have pressed even more fiercely the Heresy of the Spittoon, claiming that it derives from a much more ancient text than the Boetticher-attributed ones mentioned above.

Antonio of the Red Palace writes:

Regarding the scene involving the spittoon, I think it’s a shout-out to another one from Sternberg’s Underworld. You know, that one involving an equally “Borachone” character (Rolls Royce Wensel) being humiliated by “Buck” Mulligan. Interestingly, the “hero” (in this case Bull Weed) stands for the weak one.

Even in both films, the female character is called Feathers. ¿ Coincidence?

The Exegete declares a heartening willingness to believe, as all Seekers must, that There are no coincidences. From David Cairns, Sifu of Shadowplay, Exegete Extraordinaire of many other texts, comes further observations:

Like Antonio of the Red Palace, Shadowplay Sifu displays admirable historical awareness and interpretive ingenuity. But there is still room for disputation about sources and the path of influence. Here is Lea Jacobs of the School of the Badger to open another avenue:

The earliest version of the coin in the spittoon that I know is Underworld. Charles Furthman, brother of Jules [scribe who co-penned Rio Bravo], worked on the adaptation [of Underworld]. So I have always assumed the bit was “in the family.”

It is a measure of the spiritual power of the Sacred Text that it so stirs the imagination of the devout. And in truth, this scrolling blog’s little guide should have pointed out the strongest evidence for the Spittoon heresy (as well as the philological question of “Feathers”). These Exegetes are hereby thanked for extending the already vast commentary on the Text. But let us remember that the earlier text in question is regarded by many Adepts as itself derivative.

In Underworld, the nemesis who flings a ten-dollar bill into the spittoon is called “Buck” Mulligan–a transparent trace of literary lineage. For what readers text do not recognize the reference?

Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed.

Let us not forget that this literary “Buck Mulligan” has the proper first name Malachi, usually translated as “God’s messenger.” This surely changes our understanding of the blowhard who mockingly offers the ten-dollar bill to Rolls Royce; for he starts Rolls Royce on his path toward sobriety and self-respect.

For such reasons, Ulysses is most fruitfully read as a gloss on Underworld.

Nonetheless, consultation with wiser heads than this chronicler’s yields a change in the Canon. Henceforth the Heresy of the Spittoon will be known as the Cuspidor Crux.

Addendum 21 April 2012: Another Adept, Simone Starace, has disclosed more evidence for the Cuspidor Crux. She points to a passage in the secondary writ, Joseph McBride, Hawks on Hawks (1982), p. 131:

JMB: There are several things in Rio Bravo that are similar to Underworld, which you and Furthman also helped write.

HH: I stole two things, the dollar in the spittoon and the girl’s name, Feathers.

Simone adds that on page 159, according to McBride’s filmography: “Hawks claimed to have contributed to the script of Underworld.” The palimpsest thickens.

Bringing up Hawks

Hawks looms large in any history of American film, but even so…

DB here:

Still scrambling to keep up with all the movies at Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I offer a quick entry on three films in the complete retrospective of Howard Hawks’ early work. Go back here for comments on Cradle Snatchers (1927).

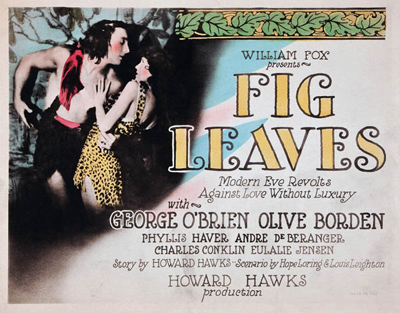

Those who claim that Hawks’ talents are at full stretch in comic situations would find solid evidence in several Ritrovato picks. Fig Leaves (1926) starts in the Garden of Eden, where Adam uses a teetering cocoanut as his alarm clock and the Serpent coaxes Eve into complaining that she simply hasn’t a thing to wear. With its Flintstones anachronisms and genial dinosaurs, the prologue of Fig Leaves makes fun of the hoary device of showing primitive life as a parallel to today, a wheeze Keaton had already exploited in Three Ages (1923).

Our modern Eve’s longing for nice clothes impells her into a job modeling for the house of André, while a shrewd jazz-baby neighbor plays the role of the Serpent in the modern garden. Filled out by Technicolor fashion parades (much praised at the time, but surviving only in contrasty black-and-white), this satirical modern comedy remains a pleasant diversion.

As ever with Hawks, there’s a play on sexual identity. When Adam and Eve wake up in the morning, he’s shot with hard-edged lighting and sharp focus. By contrast, Eve is wrapped in soft light and plenty of diffusion in the manner of the Fox heroines in Borzage and Murnau movies. No surprise there, but later the vaguely Continental dress designer André is introduced in a moderately soft, diffused image, as if he were halfway between man and woman. Although he’s not gay (that role falls to his preening assistant), he’s presented as a sissy as much through the cinematography as through his performance. Then again, most guys look effeminate compared to the brawny Charles Farrell, who is given plenty of chances to strip to the waist. Olive Borden is a matching mate. Variety predicted that “her big, dark, soulful eyes ought to carry her far in the picture world,” but it’s not her eyes that attract André. He’s riveted by the sight of her in a gown, lit from behind so that her figure pops into a curvy silhouette.

E. C. Bentley’s Trent’s Last Case of 1913 was a turning point in the modern detective novel, but you wouldn’t know it by the time that Hawks got around to filming it in 1929. He turns it into a comedy. The murder victim, the millionaire Manderson, uses a book, Unsolved Murders, as a guide to committing suicide in a fashion that will incriminate his secretary, who is in love with Manderson’s wife. The tone is uncertain, and a few cornball low angles with horror lighting are thrown in to goose up some rather overplayed moments.

E. C. Bentley’s Trent’s Last Case of 1913 was a turning point in the modern detective novel, but you wouldn’t know it by the time that Hawks got around to filming it in 1929. He turns it into a comedy. The murder victim, the millionaire Manderson, uses a book, Unsolved Murders, as a guide to committing suicide in a fashion that will incriminate his secretary, who is in love with Manderson’s wife. The tone is uncertain, and a few cornball low angles with horror lighting are thrown in to goose up some rather overplayed moments.

The Trent of the novel set the fashion for the dilettante savant (later incarnated in Lord Peter Wimsey and Ellery Queen), but he remains a somewhat withdrawn figure. In the film, comedian Raymond Griffith plays him as a parody of the chipper playboy, breezy in Griffith’s signature topper and tails. The climax provides a pure travesty of the original. The major innovation of the book, the mistaken solution that takes the sleuth down a peg, becomes a gag in Hawks’ hands. At the climax, Trent denounces one suspect, is proven wrong, moves to another, gets it wrong again, until he has arrived at the truth through elimination. Convinced that he would have sent at least four persons to the gallows, he shrugs off detective work and declares this is his last case.

The film was released in two versions, one completely silent and the other incorporating some sound sequences. The surviving print contains no talking scenes and runs nearly twenty minutes shorter than either 65-minute original. The US release of Trent’s Last Case was evidently quite brief. It remains the strangest and probably the weakest entry in the Hawks filmography.

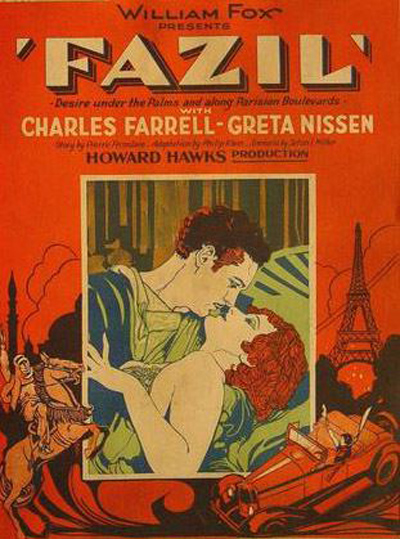

Fazil (1928) could use a lot more comedy, but it brings out Hawks’ interest in vigorous sexual situations. Fazil, a prince from “Araby,” meets Fabienne, a passionate French girl. They marry immediately. Fabienne’s desire for Fazil overcomes her worry that he believes in total domination over her. She defies his commands, and they separate, only to be reunited after she seeks him out in his homeland. When she sees his harem, and then realizes his intent to take a second wife, she again tries to opt out, this time with the help of her European friends. Her escape from his compound climaxes in a gun battle that fatally wounds Fazil. Fabienne accepts a lethal injection from his poison ring so that they may die together, with him finally confessing that he loves her.

This Orientalist farrago, handled humorously at the start (the call to prayer interrupts a beheading), quickly turns serious, even a little decadent. The sexual ambience of the Sheik cycle becomes fairly steamy. After the couple meet at a Venetian party, fade out to the next scene. Fabienne is now sharing Fazil’s bed. Has an affair started? For a little while we’re entitled to think so, until Fazil goes to the window and we see the Eiffel Tower. Soon Fabienne is on the phone talking about her marriage to the prince.

The New York Times review charged that Hawks erred “in his eagerness to display the voluptuous side of a desert chieftain’s life, a series of scenes which would never be missed. “ Actually, I’d miss the moment when Fabienne is introduced to Fazil’s harem. Tracking shots run along the line of scantily-dressed women sizing her up, and reverse shots follow her as she surveys them in fear and fascination, her fingers nervously stroking her upper chest. “August heat,” boasted a Fox ad at the time, “is intensified by the torrid Fazil.” Something like it happened in the June heat of Bologna.

The image surmounting this entry is taken from this year’s extraordinary Ritrovato catalog. Variety‘s review of Fig Leaves was published in the 7 July 1926 issue, p. 16. Bentley’s novel Trent’s Last Case is available free online. The New York Times review of Fazil appeared in the 5 June 1928 issue, p. 21. Fox’s ad for its 1928 slate was published in Variety on 11 January 1928, p. 11.

…But brunettes prefer programmers. Guy Borlée and colleagues.