Archive for the 'Directors: Hawks' Category

Unquiet silents

DB here:

It happens every year: the Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna is offering something for everyone. It’s officially dedicated to film history, but its organizers understand that history includes today. This year you can watch films from 1898 (Gaumont shorts) to 2011 (The Actor, hot from Cannes). Silent cinema is given its due, but so are films from the 1930s-1950s, with glimpses of the 1960s (Petri’s The Assassin, the new La Dolce Vita) and 1970s (Kevin Brownlow’s little-seen Winstanley).

The director retrospectives alone are overwhelming. We have a chance to watch great swatches of films by the celebrated Alice Guy, the underappreciated Luigi Zampa, the effortlessly lyrical Boris Barnet, and the still-being-discovered master of the 1910s, Albert Capellani. Oh yeah, then there’s a guy called Hawks, with a complete set of all his surviving silents filled out with little items like Twentieth Century, Tiger Shark, and thanks to Grover Crisp a lab-fresh restoration of Only Angels Have Wings that had even hard-core Ritrovato veterans gaping.

Not to mention sidebars dedicated to images of socialism and utopia, the development of color cinema, and the annual “100 Years Ago” series curated by Mariann Lewinsky, who brought a stunning array of 1911 films into our ken. With Ayn Rand’s gospel of egoism and selfishness finding ever more adherents these days, a screening of the original Italian version of We the Living (Noi Vivi) reminds us that, contrary to the evidence of this year’s Atlas Shrugged, you can make a pretty good movie from one of her books. (Of course the great Rand adaptation is the out-sized Fountainhead.) In the evenings, on the Piazza Maggiore, items like The Thief of Bagdad and Taxi Driver regale a thousand people or more.

In short, a feeding frenzy for the cinephile. We’ve been here before; you can read reports from the last four years in the category Festivals: Cinema Ritrovato. But this time things are even more intense. A fourth venue has been added, the ample and modern Cinema Jolly, so the decisions about what to see are even more pressing.

Kristin has concentrated her viewing on the 1910s, although so far she’s found time for Wind Across the Everglades and an episode of Barnet’s charming Miss Mend. (She wrote about the Flicker Alley DVD of this here). Her upcoming blog entry will concentrate on Capellani. For now, I find that a mere two films give me something to chew on.

From talky silents to talking movies

Upstream.

Ford and Hawks are very different directors, but two 1927 films, both made at Fox, allow us to see their work blending into a broad trend.

Upstream, recently rediscovered and shown to admiring audiences around the world, takes place largely in a boarding house for struggling vaudevillians. A knife-thrower is in love with his assistant, who is in love with a self-centered ham hired to play Shakespeare. Among the roomers are a declining classical actor and the song-and-dance brothers Callahan and Callahan, one of whom is Jewish. The ham accidentally becomes a star, in the process forgetting the girl he once wooed. But her marriage to the knife-thrower is threatened when the ham returns to the boarding house.

The film has the drawling, anecdotal quality of many Ford comedies. The plot is simple, but it’s decorated with character bits and an overall tone of self-aware corn. The latter was enhanced in the Ritrovato screening by the brash musical accompaniment designed by Donald Sosin, with him on piano and Guenter A. Buchwald on violin. Sosin, like Ford, knows hokum when he sees it, and both know that you must revel in it.

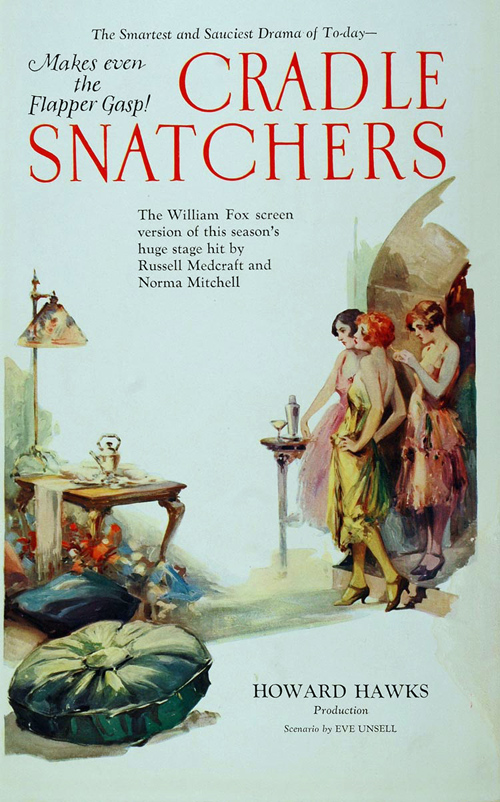

Cradle Snatchers, Hawks’ third film, shows a trio of cheated wives exacting revenge on their philandering husbands. The women arrange for three penniless college boys to pretend to court them so that their husbands can become jealous. Even though some portions are missing, the first reel is intact, and it’s instructive. Instead of opening with the women’s plight, as the source play does, the film starts with the fraternity brothers and mostly anchors our viewpoint to theirs. Variety noticed.

Probably the most remarkable angle of transplanting this “smash” comedy to celluloid lies in the manner in which the three college youths have been duplicated. As a screen threesome they overshadow the women who play the neglected wives. . . Each of the male youngsters does exceptionally well and Hawks has directed them splendidly.

Once Hawks turned it into a male-centered plot, he could indulge in the gay-play that would crop up in his later work. A title points out that “When a roommate takes a girlfriend, he becomes only half a roommate.” One of the boys hangs up on his girlfriend in order to chat up a sexy dame strolling by, but she turns out to be a frat brother in drag (the same Sammy Cohen playing Callahan frère in Upstream). Still, the gags provide equal-opportunity innuendo, as when Louise Fazenda flounces in from a massage and is asked “What have you been doing?” She replies: “I’m not doing, I’ve been done.”

Visually the films are remarkably similar. Removed from Monument Valley, Ford doesn’t give us vistas, deep focus, or even scenes organized around doorways. At home in sparky comedy, Hawks doesn’t provide the graceful, pell-mell staging we get in Twentieth Century and His Girl Friday. Instead, we have classical American silent technique, already by the early 1920s quite polished (as can be seen in the 1922 Ritrovato entry from another master, The Real Adventure by King Vidor).

This silent technique turns out rather talky. Dialogue titles constitute seventeen percent of the shots in Upstream and sixteen percent of the shots in Cradle Snatchers. This isn’t a late 1920s development, since The Real Adventure contains nearly twenty percent dialogue titles. Why are these figures interesting?

The 1920s, the era of the “mature silent cinema,” led many filmmakers and critics to expect that filmmakers would shift toward purely visual methods of storytelling. Keaton’s Our Hospitality (1923), Lloyd’s Girl Shy (1924), and Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925) remain dazzling exercises in getting maximum impact from the flow of images, with dialogue titles adding another layer of dramatic interest.

Ideally, the aesthetes thought, one could make a film entirely without titles. German films like Der letzte Mann (1924) are the most famous examples, but there were American experiments along these lines too, such as The Old Swimmin’ Hole (1921). The arrival of sound threatened this trend toward “purely cinematic” narration. Now, critics fretted, filmmakers would be forced to rely on language to make dramatic points. The visual side of cinema would be secondary to “theatrical” methods.

Actually, however, alongside the consummate pictorial storytelling of Keaton, Lloyd, Lubitsch, and others, something else was happening. During the 1920s, quite a lot of American cinema became dependent on language. This happened, paradoxically, because of what critics then and since called the increasingly “cinematic” qualities of movie storytelling.

Not having either Cradle Snatchers or Upstream available for illustration, here’s an example from a film not playing here. In Henry King’s Winning of Barbara Worth (1926), Holmes the engineer is calling on Barbara before he sets out on a mission. He tells her that he plans to go back east, and he’d like her to join him. He’ll be back in a week for her decision.

At the purely imagistic level, the scene is presented in standard continuity, with a long shot establishing the kitchen, then a series of reverse-angle medium-close shots of Holmes and Barbara as they talk flirtatiously.

The conversation is interrupted by a cutaway to Abe outside, coming in the gate, which serves as a transition to a two-shot of Holmes and Barbara.

It’s from that framing that Holmes leaves, and she lingers at the doorway.

But the scene is even more broken down than this. Of its twenty-eight shots only eighteen are images; the other ten are dialogue titles. They are sandwiched in between the tight singles of Holmes and Barbara, as here:

In effect, breaking the scene down “cinematically” into close views of each character may seem to pull cinema away from theatre. Yet it works to frame and underscore each line of dialogue. The pattern is speaker/ title/ speaker. Even the more distant shots, like the opening establishing shot and the final two-shot framing, are broken up by inserted titles.

Across the 116 seconds of the passage, nearly 36% of the shots consist of dialogue. Of course this proportion wouldn’t be sustained across the whole film, since many sequences are filled with physical action and have no conversation. But in this and many other films American directors were creating a silent-film dramaturgy that incorporated dialogue into the texture of the cutting. Dialogue titles became editing units that could maintain a rapid pace and, combined with legible singles and two-shots, made for cogent storytelling.

This is what happens in Upstream and Cradle Snatchers. They are dialogue-driven vehicles (one a short-story adaptation, the other taken from a play), and both Ford and Hawks, idiosyncratic stylists in other genres and at other times, accept the dominant norms of their moment for these projects. These films employ speaker/ title/ speaker cutting, the singles and firm two-shots, and the careful eyeline matching. In fact, Ford uses a clever “impossible” eyeline match when the ham star looks up from the dinner table and the answering shot shows the distraught Gertie in her room upstairs, looking down, as if at him.

So were films like Upstream, Cradle Snatchers, The Real Adventure, and The Winning of Barbara Worth “preparing” for sound? In the sense of underscoring dialogue, yes. But the detailed breakdown into singles was not the most common option in most talkie scenes, at least in US cinema. (Japan is another story; cf. Ozu’s 1930s films.) The default for most scenes was the two-shot framing, with characters conversing within a sustained shot. This strategy is present at the end of our Barbara Worth scene, and it can be found throughout 1920s cinema. In other words, given the choices already established during the 1920s, sound-era filmmakers usually preferred the two-shot over singles. Accordingly, the cutting rate slowed down in most sound cinema. (The over-the-shoulder shot, a sort of single-plus, was another fairly rare option in the 1920s, but that too came into its own in the talking film.)

As often happens, Hollywood style offers a menu, with some options becoming more common at different periods. For sound filming, directors relied upon what had been an alternative option in the silent era, the two-shot. They saved singles for key moments. Today, with the dominance of what I’ve called intensified continuity, we seem to be back in the late 1920s. Filmmakers are inclined to present a line of dialogue with a tight single of the speaker, as happens in the Ford, Hawks, Vidor, and King films–but this time, of course, sync sound does duty for the intertitles.

This is one of the things that Ritrovato does best—provoke you into seeing new connections and trying out fresh ideas. Of course, it shows you a wonderful time in the process.

Kristin’s 2010 blog entry on Capellani is here. She will update it and write a new one after she’s assimilated the Ritrovato experience. The Variety review of Cradle Snatchers is from 1 June 1927, p. 16. We discuss dialogue intertitles in American cinema throughout The Classical Hollywood Cinema (1985), particularly in the chapters written by Kristin.

Robin Wood

DB here:

Robin Wood has just died. Kristin and I knew him a little; we recall a convivial dinner with Robin and Richard Lippe in New York during the 1970s. We knew him chiefly on the page, as a writer whom we valued enormously. I take this moment to acknowledge his death, to suggest his importance, and to praise his memory.

Today it’s hard to imagine the impact that Wood had on film criticism in the late 1960s and early 1970s. I first encountered his writing while I was in high school. I desperately wanted to know more about movies, but the nearest towns had no libraries. So I wrote to every film magazine I had heard of and said I was considering subscribing. Could they please send me a sample copy? The issues that came through included, most memorably, the Sarris “American Directors” issue of Film Culture and the Howard Hawks issue of Movie. Both changed me forever.

The Hawks issue contained Wood’s essay on Rio Bravo, a sort of draft for what would become one of his most important statements.

Hawks, like Shakespeare, is an artist earning his living in a popular, commercialized medium, producing work for the most diverse audiences in a wide variety of genres. Those who complain that he “compromises” by including “comic relief” and songs in Rio Bravo call to mind the eighteenth century critics who saw Shakespeare’s clowns as mere vulgar irrelevancies stuck in to please the “ignorant” masses. Had they been contemporaries of the first Elizabeth, they would doubtless have preferred Sir Philip Sydney (analogous evaluations are made quarterly in Sight and Sound). Hawks, like Shakespeare, uses his clowns and his songs for fundamentally serious purposes, integrating them in the thematic structure. His acceptance of the underlying conventions gives Rio Bravo, like Shakespeare’s plays, the timeless, universal quality of myth or fable.

Nearly every Wood virtue is already here. He takes it for granted that conventions are crucial to understanding and judging cinema. He refuses an evaluative split between high culture and popular culture. He insists that worthy films have serious thematic implications—in Rio Bravo, a link between self-respect and peer respect. He shows the film’s complexity through shrewd comparison (in the book on Hawks, High Noon will provide the telling contrast). And he gives the whole thing a polemical edge with the sideswipe at Sight and Sound, a target for many years to come.

But it was the books, in an apparently unending flow, that established Wood as a leading voice, and not only for me. I can’t convey the excitement that was ignited by Hitchcock’s Films (1965), Howard Hawks (1968), and Ingmar Bergman (1969), quickly followed by the monographs on Penn (1970) and Ray’s Apu Trilogy (1971). Nearly all books of film criticism were then simply collections of reviews. Wood’s stood as through-written, pondered over, carefully carpentered monographs, comparable to the best literary analysis. These studies showed, in incisive detail, what most auteur criticism simply proclaimed: great directors expressed their personal vision of life in and through cinema. Wood showed, scene by scene and sometimes shot by shot, that movies harbored layers of feeling and implication in their finest grain of detail. Without fanfare he introduced “close reading” to film criticism. Although never academic in the narrow sense, he took cinema as seriously as did critics of art or music or literature.

In fact, the word “serious,” a tonal center of the Rio Bravo essay, might be the keyword of his career. Partly that seriousness is intellectual. From the start Wood’s prose had a rectitude that was argumentative in the best sense. The Hitchcock book begins by imagining the best case one can make against the director; he then demolishes it piece by piece. The author does not try to woo us. He respects his reader enough to spell out his claims and to invite a skeptical reply. At last, we thought: An honest man.

The idea of seriousness took on a deeper import, one shaped by the indelible influence of F. R. Leavis. For Wood as for Leavis, great art inevitably grappled with the ultimate demands of living. Close analysis was nothing unless it revealed the author’s felt engagement with human values. This state of affairs imposed equally stringent obligations on the critic. Nothing could be farther from the snappy badinage and instant turnaround of Netwriting than Wood’s obstinate gravity. Flippancy and showing off had no place in serious criticism. Being a critic, analyzing and interpreting and judging, was a heavy responsibility, and every word had to be weighed. The very status of film as art, indeed the status of art itself, was at stake.

In a passage I cannot find on short notice, Wood once observed that a critic could not write “seriously” about Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Flowers of Shanghai after one viewing. Accordingly, not until he could study the film on DVD did he produce a characteristically penetrating essay. It’s a piece that anyone would be proud to sign, but Wood concludes:

I’m afraid the above analysis, in spelling things out, may have suggested that the film is more schematic than it actually is. Its “scheme” is in fact so subtly worked that it has taken me at least six complete viewings (together with more replays of individual scenes and moments than I can count) to disentangle it from all the detail of the realization. The above account is offered humbly, as a beginning.

This passion for nuance did not lead to a sort of scientific objectivity. The responsibility of criticism made writing inescapably personal. The critic responds to the work as a living being, as a “whole man alive”—a Leavis phrase that Wood was wont to quote. Personal Views, the title of Wood’s first collection of essays, signalled both the artistic visions expressed in the films he studied and the sincerity with which he advocated for or inveighed against a film, a trend, or a system of ideas.

I don’t know any critic whose intellectual and political horizons expanded as much as Wood’s did in the 1970s. Since criticism was for him a form of living, he took his readers along as he discovered structuralist theory (which he had once attacked), accepted some tenets of psychoanalytic theory, and launched ferocious attacks on patriarchy and capitalism. The same moral fervor that informed his 1960s writing became focused upon the political oppression of women, gays, the poor, and free thought. Now, he suggested, the apparent stability of “ordinary” life relied upon psychological and social repression. If one theme runs through his work—that of the precariousness of decent human relations in the face of disorder—it finds its late expression in his belief that conservative politics, in the name of maintaining order, is implacably bent upon destroying our kinship with others. In a sense, CineAction, the journal that he co-founded, was his latter-day Movie, a forum for his new commitment to criticism that promoted progressive social change.

The art he cared most about, I believe, laid bare the struggle between order and disorder. In his first book, he argues that Hitchcock shows comfortable “ordinary” people faced with a world coming to pieces. Across his career Wood ceaselessly questioned what exactly this normal order consists of. Coming out as a gay man, he devoted his finely meshed attention to reading films politically. Now those social forces that he once defined simply as threats to stability, such as the war in Bergman’s Shame, revealed themselves as products of warped political systems. The horror film presents disorder as a monstrous threat to bourgeois norms, yet it can become a powerful force in questioning those conceptions. For nearly four decades Wood recorded his efforts to grasp the concrete social implications behind the films he loved and those, increasingly from Hollywood, he found evasive and duplicitous. In all, complacent acceptance of the status quo was the enemy of the seriousness he prized. When he died he was at work on a study of Michael Haneke.

The seriousness of great artists, he came to believe, was inescapably political. Yet while this made him reevaluate Hawks and Hitchcock, it did not lead him to absolute repudiations. Always a believer in the validity of intuitive response, Wood would trust his sensibility more than the dictates of academic “frameworks” and theoretical systems. A 2004 set of notes on Ozu concludes:

These late Ozu films are detailed and highly intelligent critical studies in cultural change which ultimately defy the application of such terms as “progressive,” “regressive,” “conservative,” etc. . . . “Change” is not necessarily for the better (though our current culture is constantly telling us that of course it is) . . .—an obvious ploy of corporate capitalism, which depends upon the mystification for selling its products. If we gain new freedoms, we should also beware of casually casting off the past without asking ourselves what in it—what standards of seriousness, what beliefs, what aspects of our lives—might be worth preserving. I find all these thoughts in Ozu, incomparably expressed.

Through all the constant reappraisals of films, all the unsparing reconsiderations of his own judgments, one hears the same forthright, urgent voice. Leavis suggested that the good critic always asked, in effect, “This is so, isn’t it?” Wood’s writing consists of firm assertions accompanied by challenges to respond as an equal. The invitation is set out in an impassioned conversational cadence, complete with italics and appositional phrases. In search of clarity, Wood is prepared to argue and dissect forever; who else would produce not one but two books rethinking his defense of Hitchcock? Yet this brisk voice can also move us by its simplicity, as in the sentences concluding that little book on the Apu trilogy.

Suddenly the boy relaxes, and rushes forward into his father’s arms. The film ends with him seated on Apu’s shoulders as Apu walks away towards the future. In accepting the child, he has accepted life, has accepted the death of Aparna. Whether or not he is going back to become a great novelist is immaterial: he is going back to live.

Wood’s essay on Rio Bravo is in Movie no. 5 (undated, 1963?), 25-27. His “Flowers of Shanghai” appears in CineAction no. 56 (September 2001), 11-19. “Notes toward a Reading of Tokyo Twilight (Tokyo boshoku)” is in CineAction no. 63 (April 2004), 57-58.

For a wide-ranging and growing set of links to eulogies for Robin Wood, visit David Hudson at The Auteurs Daily and Catherine Grant at Film Studies for Free. A recent interview framed by enlightening commentary is Armen Svadjian’s 2006 tribute, “A Life in Film Criticism: Robin Wood at 75.” Wood’s 2008 list of the films he most valued is on the Criterion site here. D. K. Holm maintains an invaluable, continually updated bibliography of Wood’s writings here.

François Truffaut, Day for Night (1973).

Between you, me, and the bedpost

Imitation of Life.

DB here:

I do not like finding phallic symbols in movies.

I grant you that there are some films that deliberately evoke the love wand: Tex Avery cartoons, Frank Tashlin and Jerry Lewis movies. Surely the Wolf in Avery’s Red Hot Riding Hood (1943) has more than a Platonic interest in Red’s stage show.

But some critics/ academics look way too hard. For them, as a literature professor of mine put it back in the mid-1960s, phallic symbols are everywhere in art. And I learned fast that he meant everywhere, from the Odyssey to Emily Dickinson. I changed sections.

Films, of course, are full of images that encourage the hunt for avatars of the skin flute. So for forty years, I’ve argued against interpretations of a scene that depend on reading you-know-what into anything that resembles a pole, post, or pylon—any vaguely tubular shape, slender or squat, organic or mechanical. It is a duffer’s mistake to think that film shots including swords, logs, telephone poles, pine trees, skyscrapers, Greek columns, fountain pens, picket fences, shovels, rocket ships, and Pontiac fins always pay homage to the trouser snake.

Except, I must admit, bedposts.

I don’t think I’ve ever slept in a bed with bedposts, not even in those cozy B & Bs that smother you with affection and sugar-sprinkled muffins. But the American cinema likes bedposts. Red-blooded American women in classic movies often have beds braced or decorated with bedposts.

Sometimes those bedposts do some alarming things.

Exhibit A: Start, as we often do (but probably shouldn’t), with D. W. Griffith. In The Birth of a Nation, Elsie Stoneman has just spent a romantic afternoon with Ben Cameron, aka The Little Colonel.

She races into her bedroom, obviously smitten.

What does she do? She hops to the bed and leans dreamily against the fancy tapering bedpost. Now Griffith gives us the closest image of her that we’ve seen so far in the movie.

And since Griffith never passes up a chance to crosscut between anything and anything else, we get another shot of Ben, perhaps looking off toward Elsie’s house. (We have to say perhaps because Griffith is not terribly concerned with consistent eyelines.) It operates as a typical Griffith signal that one character is thinking about another.

And as if aware that Ben is thinking of her, Elsie rewards her bedpost accordingly.

Should you doubt that these bedpost calisthenics are connected with the thought of a guy, I submit Exhibit B. In Bringing Up Baby, Susan Vance (Katharine Hepburn) is taken with David Huxley (Cary Grant). While he showers, she wraps herself around the only thing in the room taller than she is.

One can easily see why a glimpse of Cary Grant stepping out of the shower could make somebody clutch a support , but wouldn’t a chair have done as well?

Exhibit C: Douglas Sirk has done interesting bedpost work in Imitiation of Life (surmounting this entry), but surely his triumph is Magnificent Obsession (1954). A blind Helen Phillips (Jane Wyman) has just learned that no operation is likely to recover her sight. Helen rises from her chair, and we hear a wordless choir along with a piano theme evocative of Rob (Rock Hudson), the mysterious man in her life. As if drawn by magnetism, she makes her way through the darkness to a totemic mass, sort of Elsie Stoneman’s bedpost on Viagra. She moves with the solemnity of a priestess paying homage to an angry god.

Actually, this thing isn’t exactly a bedpost; it’s a strange thrusting protrusion from a love seat that functions as a room divider. But it’s clearly in the bedpost tradition—as we see when, like Elsie, Helen embraces it and leans her head against it.

Soon Rob enters, framed by the post, and in no time the couple are in a clinch.

If forced to interpret these items, I’d probably say that Griffith may have included The Bedpost in a moment of frank eroticism, Hawks knew the cliché and exploited it for an actor’s bit of business, and Sirk, sophisticated Euro émigré, used it ironically. But of course these interpretations are open to dispute. I expect someone to start a dissertation on the matter immediately.

I don’t know of comparable scenes in which men, thinking of women, hug bedposts or crawl into big cavities. Bedpost worship can obviously be interpreted as another sign of Hollywood’s bias toward patriarchal values. But its blatancy and more or less witting silliness also respond to that quality that delighted Parker Tyler about Hollywood movies—the way that flagrant symbolism is flung onto the screen but toyed with, to tease us. For Tyler, the “only indubitable reading of a given movie” was

its value as a charade, a fluid guessing game where the only “winning answer” was not the right one but any amusingly relevant and suggestive one: an answer which led to interesting speculations about society, about mankind’s perennial, profuse, and typically serio-comic ability to deceive itself.

Sometimes, then, a bedpost is just a bedpost. But probably not in the movies.

The quotation comes from Parker Tyler’s Three Faces of the Film, rev. ed. (South Brunswick, NJ: Barnes, 1967), 11.

My frame enlargements from a 16mm print of Magnificent Obsession aren’t good enough in the scene I mentioned, so I’ve been obliged to draw my images from the Criterion DVD. That version crops the frame to 2.0:1, which has seemed too radical for many observers, me included. Should it instead be 1.66 or 1.85? The aspect-ratio debate has played out in extensive detail here and here.

Thanks to Lea Jacobs and Jeff Smith for some DVD loans. Jeff also encouraged me to keep this discussion in good taste.

Queen Christina.

Gradation of emphasis, starring Glenn Ford

DB here:

Charles Barr’s 1963 essay “CinemaScope: Before and After” has become a classic of English-language film criticism. (1) It proffers a lot of intriguing ideas about widescreen film, but one idea that Barr floated has more general relevance. I’ve found it a useful critical tool, and maybe you will too.

Grading on a curve

Barr called the idea gradation of emphasis. Here’s what he says:

The advantage of Scope [the 2.35:1 ratio] over even the wide screen of Hatari! [shot in 1.85:1] is that it enables complex scenes to be covered even more naturally: detail can be integrated, and therefore perceived, in a still more realistic way. If I had to sum up its implications I would say that it gives a greater range for gradation of emphasis. . . The 1:1.33 screen is too much of an abstraction, compared with the way we normally see things, to admit easily the detail which can only be really effective if it is perceived qua casual detail.

The locus classicus exemplifying this idea comes in River of No Return (1954). When Kay is lifted off the raft, she loses her grip on her wickerwork bag and it’s carried off by the current. (See the frame surmounting this entry.) Kay and her boyfriend Harry are rescued by the farmer Matt. As all three talk in the foreground, the camera catches the bundle drifting off to the right.

Even when the men turn to walk to the cabin, Preminger gives us a chance to see the bundle still drifting downstream, centered in the frame.

The point of this shot, Barr and V. F. Perkins argued, is thematic. As Kay moves from the mining camp to the wilderness, she will lose more and more of her dance-hall trappings and be ready to accept a new life with Matt and Mark. The last shot of the film shows her final traces of her old life cast away.

Cutting in to Kay’s floating bag would have been heavy-handed; if you stress a secondary element too much, it becomes primary. Barr reminds us that any film shot can include the most important information, as well as information of lesser significance. A film can achieve subtle effects by incorporating details in ways that make them subordinate as details and yet noticeable to the viewer. Or at least the alert viewer.

In Poetics of Cinema, I wrote an essay on staging options in early CinemaScope, and Barr’s idea helped me illuminate some of the strategies I discuss. (For earlier comments on Barr on Scope and River of No Return, see my article elsewhere on this site.) Today I want to consider how the notion of gradation of emphasis has a more general usefulness.

Barr contrasts the open, fluid possibilities of CinemaScope with two other stylistic approaches, both found in the squarer 1.33 format. The first approach is the editing-driven one he finds in silent film. This tends to make each shot into a single “word,” and meaning arises only when shots are assembled. Barr associates this approach with Griffith and Eisenstein. The second approach, only alluded to, is that of depth staging and deep-focus shooting, typically associated with sound cinema of the late 1930s and into the 1950s.

Both of these approaches, montage and single-take depth, lack the subtle simplicity of Scope’s gradation of emphasis.

There are innumerable applications of this [technique] (the whole question of significant imagery is affected by it): one quite common one is the scene where two people talk, and a third watches, or just appears in the background unobtrusively—he might be a person who is relevant to the others in some way, or who is affected by what they say, and it is useful for us to be “reminded” of his presence. The simple cutaway shot coarsens the effect by being too obvious a directorial aside (Look who’s watching) and on the smaller [1.33] screen it’s difficult to play off foreground and background within the frame: the detail tends to look too obviously planted. The frame is so closed-in that any detail which is placed there must be deliberate—at some level we both feel this and know it intellectually.

To see Barr’s point, consider a shot like this one from Framed (1947).

The shot, rather typical of 1940s depth staging, displays an almost fussy precision about fitting foreground and background together. That bartender, for instance, stands squeezed into just the right spot. (2) Barr claims that we sense a certain contrivance when primary and secondary centers of interest are jammed into the 1.33 frame like this.

We don’t sense the same contrivance in the widescreen format, he suggests. Barr assumes, I think, that the sheer breadth of any Scope frame will include areas of little consequence, whereas that’s comparatively rare in a 1.33 composition. This is an intriguing hunch, but uninformative patches of the frame may not be intrinsic to the Scope technology. Perhaps the fairly neutral and inexpressive uses of Scope that dominate the early 1950s, the sense of empty and insignificant acreage stretching out on all sides, make us expect that little of importance will be found there. Accordingly, directors can create a sense of discovery when we spot a significant detail in this stretch of real estate.

Anyhow, Barr indicates that if static deep-space staging made the frame too constrained, 1930s and 1940s directors who combined depth with camera movement created more spacious and fluid framings. He suggests that Mizoguchi, Renoir, and others anticipated the possibilities of Scope.

Greater flexibility was achieved long before Scope by certain directors using depth of focus and the moving camera (one of whose main advantages, as Dai Vaughan pointed out in Definition 1, is that it allows points to be made literally “in passing”). Scope as always does not create a new method, it encourages, and refines, an old one (pp. 18-19).

Barr believes that Scope positively encouraged gradation of emphasis, and that widescreen directors of the 1950s and 1960s have made the most fruitful use of the strategy. But he allows directors of all periods utilized gradation of emphasis, even in the standard 1.33 format. This is, I believe, a powerful idea.

Before Scope: Making the grade

Barr’s discussion of silent cinema, relying on notions of editing associated with Griffith and Soviet directors like Eisenstein, is done with a broad brush, but it’s typical of the period in which he was writing. We didn’t know much about silent filmmaking until archivists started to exhume important work in the 1970s. It’s no exaggeration to say that we haven’t really begun to understand the first twenty-five years of cinema until fairly recently.

In a way, the staging-driven tradition of the 1910s, which I’ve often mentioned on this site (here and here and here), exemplifies some things that Barr would approve of. Directors of that period made extraordinary use of the frame and compositional patterning. They staged action laterally, in depth, or both. They let shots ripen slowly or burst with new information. This approach to using the full frame (with only occasionally cut-in elements) has come to be called the tableau style, emphasizing its similarity to composition of a painting—although we shouldn’t forget that these films are moving paintings, and the compositions are constantly changing. The result is that emphasis tends to be modulated and distributed among several points of interest.

Central to this strategy, I think, was camera distance. American directors tended to set the camera moderately close, cutting figures off at the knees or hips, and by taking up more frame space, the foreground actors tended to limit the area available for depth arrangement or for significant detail.

This shot from Thanhouser’s The Cry of the Children (1912) is a rough 1910s equivalent of the crammed shot from Framed above. (See also the tightly composed shots from DeMille’s Kindling (1915) here.)

The European directors, by contrast, tended to let the scene play out in more distant shots, creating spacious framings of a sort that would be reinstituted in early CinemaScope. Consider this shot from Holger-Madsen’s Towards the Light (Mod Lyset, 1919) and another from Island in the Sun (1957).

Both, it seems to me, have the type of open composition and the foreground/ background interplay that Barr praises in his article.

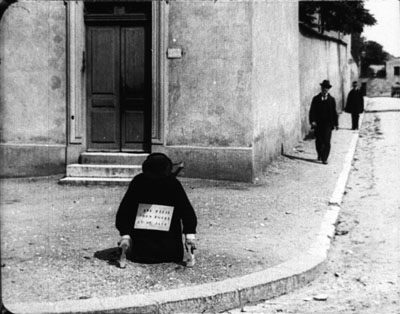

We can go back further. The Lumière brothers’ cameramen made fiction films as well as documentaries, and we occasionally find moments that suggest early efforts at gradation of emphasis. In Le Faux cul-de-jatte (1897), an apparent amputee is begging in the foreground while in the distance a man is walking down the street.

A cop crosses the street from off right and follows the pedestrian.

As the foreground fills up, the man we’ve seen in the distance gives the beggar some money.

As he goes out left, the cop is still approaching, and a vagrant dog appears.

The cop comes to the beggar, partially blocking the dog, who takes care of other business. (Not everything in this movie is staged.)

The cop checks the beggar’s papers and finds them to be suspect. The fake amputee jumps up and races off in the distance, with the cop pursuing.

As with many staged Lumière shorts, several figures converge in the foreground in order to create a culminating piece of action. Here the distant man and the cop, both secondary centers of interest, serve as a kind of timer, assuring us that something will happen when they meet at the beggar.

These are just some quick examples. We should continue to study the ways in which, with minimal use of editing, early filmmakers found ingenious ways to create gradation of emphasis. (2)

Some uses of grading

Barr, like most critics writing for the British journal Movie, was sensitive to the ways in which technique has implications for character psychology and broader thematic meanings. Kay’s bundle is one point along a series of changes in her character and her situation. But gradation of emphasis can serve more straightforward narrative purposes as well.

Consider our old friends, surprise and suspense. In the original 3:10 to Yuma (1957) Dan Evans is confronting the ruthless outlaw Ben Wade.

We get a string of reverse shots.

Then in one shot of Wade, without warning, a shadowy figure emerges out of focus in the left background.

Now we realize that Evans has been diverting Wade from the fact that the sheriff’s posse is surrounding him. Now we wait for Wade to discover it; how will he react?

While we’re on Glenn Ford, another nice example occurs in Framed. Mike Lambert has been romancing a woman named Paula, but we know that she and her lover Steve are plotting to fake Steve’s death and substitute Mike’s body.

She brings Mike to Steve’s elegant country house, having presented Steve as someone she knows only slightly. When Mike goes into the bathroom to wash up, we notice something important behind him.

With Mike at the sink, we have plenty of time to recognize Paula’s robe. Director Richard Wallace prolongs the suspense by giving us a new shot of Mike in the mirror, with the robe no longer visible.

But when Mike turns to leave, a pan following him brings him face to face with what we saw, accentuated by a track forward.

We get Mike’s reaction shot, followed by a cut to Steve and Paula downstairs, suspecting nothing. “So far, so good,” says Steve, looking upward at the bathroom.

The rest of the scene will play out with Mike aware that they’re deceiving him. As often happens with suspense, we know more than any one character: We know the couple’s scheme and Mike doesn’t, but they don’t (yet) know that Mike is now on his guard.

This isn’t as subtle a case as River of No Return, but I suspect that it’s more typical of the way Hollywood filmmakers use gradation of emphasis. Paula’s bathrobe is a good example of what I called in The Classical Hollywood Cinema the strategy of priming: planting a subsidiary element in the frame that will take on a major role, even if initially its presence isn’t registered strongly. My example in CHC was a coat rack in the Dean Martin/ Jerry Lewis comedy The Caddy (1953). In effect, the distant pedestrian in the Lumière film is an early example of priming.

Howard Hawks adopts the Lumière technique in order to sustain a flow of dialogue in Twentieth Century (1934). Here the foreground conversation is accompanied by a procession of people emerging in the distance and stepping up to take part.

The shot concludes, as does the shot of Faux cul-de-jattes, with a retreat from the camera.

The priming of secondary elements here, the summoning of the train attendant and the conductor, obeys Alexander Mackendrick’s dictum that the director ought to construct each shot so as to prepare for what will come next.

As Barr indicates, the idea of gradation shades insensibly off into general matters of cinematic expression. In The Devil Thumbs a Ride (1947), the bank robber has hitched a ride with an unassuming civilian, and they stop for gas. When the attendant shows a picture of his little girl, the robber gratuitously insults her. (“With those ears she’ll probably fly before she can walk.”)

Later, the station attendant hears a radio broadcast describing the fugitive. First he has his head cocked as he listens attentively, but then his gaze drifts to the picture of his little girl.

The attendant is the center of dramatic interest, but when he looks at the picture, so do we (primed by the view of it earlier). Instantly we understand that the attendant’s resolve to call the police springs partly from an urge to get even with the man who insulted his daughter. A minor instance, surely, but it illustrates Barr’s point that the notion of gradation of emphasis leads us to consider “the whole question of significant imagery.”

The more the merrier

Barr seems to favor a plain style; he prefers Preminger’s quiet framings to the rococo imagery of Aldrich’s Vera Cruz (1954). Presumably the famous shot above from Wyler’s Best Years of Our Lives (1946) would be too obviously composed for Barr’s taste.

But there is merit in considering how a secondary center of interest can vie for supremacy. André Bazin declared Wyler’s shot a bold stroke exactly because its self-conscious precision created a tension between what was primary and what was subordinate. (3) The action in the foreground is of dramatic interest because Homer has learned to play the piano, and this represents a phase of his coming to terms with his wartime disability. Yet the most consequential action is taking place in the distant phone booth, where Fred breaks up with Al’s daughter Peggy. The gradation of emphasis is inverted, and we wait in suspense to find out what happens. Bazin taught us to recognize that what appears to be primary may actually be creatively distracting us from the scene’s principal action. (4)

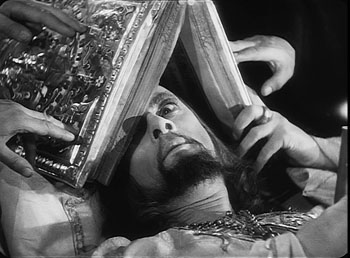

A director can also turn a primary center of interest into something secondary, but powerful. In one sequence of Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible I (1944), the apparently dying tsar is being prayed over by churchmen. Ever suspicious, he peers out from under the book, using only one eye.

As the scene develops, Prince Kurbsky meets Ivan’s wife and tries to seduce her. In the background an icon’s eye glares out, as if Ivan is watching them.

The single eye, which is a motif we find in other Eisenstein films, becomes a significant one throughout both parts of Ivan. More generally, this device manifests Eisenstein’s conception of polyphonic montage, which explored how the filmmaker can control all the various aspects of his images and make them weave throughout the film—promoting one at one moment, demoting it at another. (5)

Barr’s essay assumes that Eisenstein’s montage stripped each image down to a single meaning. In fact, though, Eisenstein wanted to multiply the sensuous and intellectual implications of each shot by weaving objects, gestures, body parts, musical motifs, and the like into an ongoing stylistic fabric. Each shot’s gradation of emphasis can suggest thematic parallels, deepen the drama, or heighten emotional expression, just as a complex score enhances an operatic scene.

Tati as well likes to create an interplay between primary and subsidiary centers of interest. Or rather, he sometimes abolishes our sense of what is primary and what isn’t. The crowded compositions of Play Time (1967) often bury their gags in a welter of inessential details. During the lengthy scene in the Royal Garden restaurant, a minor running gag involves the dyspeptic manager. He has just mixed some headache medicine with mineral water, but the action is easily lost within the tumultuous image. Even the soundtrack cues us only slightly, with a bit of fizz among the music and crowd noise.

As the manager lowers the glass, Hulot thinks it’s pink champagne being offered to him.

Rolling the stuff in his mouth, Hulot realizes his mistake as he earns a stare from the manager.

There is so much competing sound and activity in the shot that some viewers simply don’t notice this bit at all. In Play Time, gradation of emphasis is often flattened out, leaving us to rummage around the composition for the gag.

Some final notes

Barr was not particularly interested in the mechanics of how we come to notice something in the shot, be it primary or secondary in value. In On the History of Film Style, I suggested that many aspects of technique work to call attention to any element in the field. The filmmaker can put a something in motion, turn it to face us, light it more brightly, make it a vivid color, center it in the frame, have it advance to the foreground, have other characters look at it, and so on. These tactics can work together in a complex choreography. In Figures Traced in Light, I argued that they depend on the fact that we scan the frame actively; the techniques guide our visual exploration. (6)

You can see this guidance at work in most of the examples I’ve mentioned. In River of No Return, we are coaxed into noticing Kay’s bundle because we’re cued by movement (the bundle falls and drifts off), performance (she shouts, “My Things!” and stretches out her arm), music (we hear a chord as the bundle splashes), and framing (Preminger’s camera pans slightly as the trunk drifts away). The critic can refine our sense of the effects that a film arouses, but it’s one task of a poetics of cinema, as I conceive it, to examine the principles and processes that filmmakers activate in achieving those effects.

Finally, we might ask: To what extent do we find gradation of emphasis in current filmmaking? Today’s American cinema relies heavily on editing, using a style I’ve called intensified continuity. Each shot tends to mean just one thing, and once we get it we’re rushed on to the next. The unforced openness of the wide frame that Barr celebrated has been largely banned, in favor of tight singles—even in the 2.40 anamorphic format. It seems that most filmmakers are no longer concerned with gradation of emphasis within their shots.

To find this strategy surviving at its richest, I think we have to look overseas. If you want names: Angelopoulos, Tarr, Kore-eda, Jia, Hou. (7)

(1) It was published in Film Quarterly, vol. 16, no. 4 (Summer, 1963), 4-24. Unfortunately, it’s not available free online, nor is a complete version available in anthologies, so far as I know. If you have access to online journal databases, you can find it. Otherwise, off to the library w’ye!

(2) In the Poetics of Cinema piece (pp. 303-307), I argue that some early uses of Scope tried to approximate such tightly organized composition, despite technological barriers to focusing several planes of action.

(3) See André Bazin, “William Wyler, or the Jansenist of Directing,” in Bazin at Work: Major Essays and Reviews from the Forties and Fifties, ed. Bert Cardullo, trans. Cardullo and Alain Piette (New York: Routledge, 1997), 14-16.

(4) Actually the phone booth is primed for our notice by earlier shots in Butch’s tavern. See On the History of Film Style, 225-228.

(5) For more on Eisenstein’s idea of polyphonic montage, see my Cinema of Eisenstein (New York: Routledge, 2005) and Kristin’s Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible: A Neoformalist Analysis (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981).

(6) For some empirical evidence of this guided scanning, see the work of Tim Smith at his website and in this entry on this site.

(7) I discuss some of these alternatives in On the History of Film Style and the last chapter of Figures Traced in Light.

Eternity and a Day.

PS 15 Nov. Two more items. First, if the ideas floated here intrigue you, you might want to take a look at an earlier entry on this site, called “Sleeves.”

Second, I had planned to include one more example, but forgot it. In Lumet’s Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead, Andy Hanson’s life is unraveling. We follow him back to his apartment, and as he enters on the extreme left, his wife Gina is visible sitting on the extreme right, her back to us.

Gina forms a secondary center of attention, but the key to the upcoming action is revealed in a third point of interest: the black suitcase pressed against the right frame edge. The shot tells us, more obliquely than one showing her leaving the bedroom with the case, that she is planning to leave him. Lumet’s image, reminiscent of the framing of the trunk in River of No Return, shows that gradation of emphasis isn’t completely dead in American cinema. The orange scrap of yarn, knotted to the handle for baggage identification, is a nice touch of realism as well as a welcome color accent that further draws the suitcase to our notice.