Archive for the 'Directors: Hawks' Category

Some cuts I have known and loved

DB here, belatedly:

We’ve been so busy revising our textbook, Film History: An Introduction, for its third edition that we’ve had no time to see new movies, let alone blog on our regular schedule. To those loyal readers who have been checking back occasionally, we say: Thanks for your patience. An entry that should intrigue you is in the works, possibly to be posted very soon.

In the meantime, here’s an item on a subject I’ve been meaning to slip in at some point. It’s a tribute to cuts I admire.

Warning: Superb as Eisenstein’s, Ozu’s, and Hitchcock’s cuts are, I’m deliberately leaving them out. Too obvious!

Kata and cutting

Okay, Kurosawa is an obvious choice too, but I can’t pass up some of the first outstanding cuts I noticed in his work, back when I was projecting movies for my college film society. The cuts occur during the climactic battle of Seven Samurai (1954).

As is well-known, Kurosawa shot the sequence with several cameras using different focal-length lenses. What is less often acknowledged, I think, is the power of certain cuts as they combine with fixed camera positions. In his last films, Kurosawa would rely strongly on long-lens shots that pan over the pageantry of his crowd scenes, but here he exploits static frames.

In the eye of the battle, Kambei fires his arrow in one shot, and a horseman falls victim to his marksmanship in the next. So far, so conventional. But what’s unusual is that we don’t actually see the arrow hit its target. Kambei fires, and Kurosawa cuts to an empty bit of the town square, churned with mud and dimly visible through horses’ legs. Only after an instant does a fallen bandit skid into the telephoto frame.

The same thing happens when Kambei shoots his second arrow: we must wait for the victim to plunge into the frame.

The result, I think, is a sense of exhilarating inevitability. The camera knows that the horseman will fall, and it knows exactly where. That’s a way of saying that Kurosawa’s visual narration fulfills our expectation, but with a slight delay. The empty frame prompts us to anticipate that the man will be hit—why else show it?—and we have a moment of suspense in waiting to confirm what we expect. Moreover, the force of Kambei’s arm is given us through a principle of Movie Physics: motion communicated to another body is magnified, not diminished, and the fixed frame allows us to see just how far the bodies are propelled. The arrow must have been Homerically powerful if it sends these men to earth with such impact.

Most directors would have panned to follow the victim as, wearing the arrow, he tumbled off his horse and hit the ground. This choice would have been natural given the multiple-camera situation. Instead Kurosawa had his camera operators frame the exact spot the stuntman would hit and wait for the action to hurtle into the shot. The patient expertise of Kambei’s marksmanship has its counterpart in the confidence of Kurosawa’s style. (1)

The moving image, Mr. Griffith, and us

Then there’s Intolerance (1916).

The Musketeer of the Slums is trying to seduce the young man’s wife, the Dear One. He pretends he can retrieve her baby. But his earlier conquest, the Friendless One, has followed him to the tenement, and at the same time the Boy has learned about the Musketeer’s visit. As the Musketeer attacks the Dear One, the Boy bursts in. The two men struggle and the Boy is momentarily knocked out; the Dear One has swooned. So no one sees what really happens next: From the window ledge the Friendless One fires her pistol and downs the gangster. She flees, and the boy believes that he is the killer. He will be charged with the murder.

Here’s what I admire. Griffith sets the situation up with his usual rapid crosscutting—the Musketeer and the Dear One struggling, the Boy returning, and the Friendless One crawling out on the ledge. When the fight starts, Griffith shows the Friendless One growing wild-eyed at the window. She fires once, and Griffith gives the action to us in three shots: a medium shot of her in profile, a medium-long shot of the pistol at the window (irised so we notice it), and a long-shot of the room, as the Musketeer is hit.

Griffith repeats the series of shots when the Friendless One fires again.

This time the Musketeer staggers out to the hall and dies. Neatly, Griffith gives us three more shots, but omits the setup showing the Friendless One. Cut to the curtains again, with her hand waving the pistol, then to another long shot of the room as the gun is tossed in, and finally to a close-up of the pistol landing on the floor.

If you’re looking for a pattern, the pistol in close-up is in effect substituted for the shot of the Friendless One at the start of each cycle. But I’m most interested in the shots of the pistol. The first one at the window goes by at blinding speed—ten frames in the two prints Kristin and I have examined. (2) That works out to a bit more than half a second, if you assume 16 frame per seconds as the projection rate, which was common at the time.

Okay, fussy, but I’ve already confessed that I turn into a frame-counter, when I get the chance. The second shot of the pistol poking out of the curtains, parallel to the first, is also ten frames long. Griffith seems to have been a frame-counter too.

What’s most remarkable is that the long-shot of the pistol being flung into the room is even briefer than these closer views—only seven frames long, or less than half a second at 16fps. As a nice touch, the close-up of the pistol landing in the corner is twice that (15 frames).

In the decades that followed, directors would believe that long shots shouldn’t be cut as fast as close-ups, so the Intolerance passage can strike us as a typical Griffith misjudgment. But I admire his willingness to cut long shots so fast. It certainly creates a percussive accent. In case we didn’t catch the story point, the close-up of the pistol hitting the floor clinches it.

This is the sort of sequence that the Soviet filmmakers probably learned from. They may even have gotten ideas from Griffith’s interspersed black frames (two by my count) before each of the shots of the pistol thrusting out of the curtain. (3)

Behind the desk

Speaking of the Russians, one of my favorite cuts in Pudovkin’s movies comes during a confrontation in The End of St. Petersburg (1927). The somewhat oafish young worker known only as the Lad, who has sold out his comrades, attacks the boss Lebedev in his office. He seizes the boss and shoves him down, jamming him between his desk and the window. We see the action from one angle and then what seems to be an opposing angle.

Actually, this is a big discontinuity. Using the desk, the telephone, and the window as reference points, we can see that in the first shot, the Lad moves in from the left side of the desk to push the boss down. In the second, he has come in from the right side and Lebedev’s head is pointing in the opposite direction. We can see the weirdness of this more clearly if we simply flip one of the frames: now it looks like a consistent change of angle.

Pudovkin has created an impossible event. But the cut gives the strong sense of graphic conflict that the Soviets (not just Eisenstein) sought, creating a kind of visual clatter to underscore the violence of the action. It’s possible that Pudovkin actually flipped a “correct” framing to create the disjunction, as some of his contemporaries did. (4)

Meg, all aflutter

Pudovkin’s cut reminds us that filmmakers can get away with a lot if they change the angle drastically. It’s harder to spot a cheated element or a mismatch if the new shot makes us reorient ourselves. Why does this happen? That’s a subject for research, as I’ll suggest at the end.

Here’s another tricky item. In Kate & Leopold (2001), Kate has brought her time-traveling guest to an audition for a butter commercial. In the studio, he’s behind her as she tries to convince her colleagues to watch him. As she talks, she first watches Leopold in the monitor above them, then swivels to talk to her boyfriend and other suits. The camera positions change 180 degrees.

This drastic shift works to prepare us for a remarkable cut a little later. Kate waves her hand, saying she only needs two minutes. She pivots her body, moving her hand downward.

Cut 180 degrees to a setup similar to the one we’ve seen earlier: She drops her hand to her side as she swings to us.

The gesture is smoothly matched. The only trouble is that it’s executed by the wrong hand. In the first shot Kate is wiggling her left hand, but in the second, it’s her right hand that continues the movement and drops to her hip.

I don’t think that many people would notice this. Indeed, when I first saw the film, I felt a bump hereabouts, but when I watched it over again on DVD, it looked fine to me. Then I watched it again and saw what was wrong. Even then, I thought I might be hallucinating. It’s one of the trickiest cheats I know of, and it’s beautifully done.

The real question is: Why don’t we notice it? We usually say, “Because we’re watching the story and ignore little irregularities.” But that’s not very satisfactory. Why isn’t the wave of Kate’s hand part of the story? We certainly notice it as expressing her attitude—hence as part of the story. And if you didn’t notice the disjunction in my End of St. Petersburg example, the same question arises: Isn’t the Lad’s attack on the boss the very story action we’re watching?

Consider the alternative. If director James Mangold had matched the left hand, it would have to cross the center of the frame as Kate pivots, shifting from screen left to screen right before landing at her hip. It would have been ostentatious and somewhat graceless, and perhaps that would have been distracting. So the mismatch is perhaps a line of least resistance, a compromise–as so many stylistic choices are.

In addition, Kristin suggests that our pickup is made easier by the placement and action of the hand. In both shots it’s quite central and moving in the same direction at the same rate, so that it’s easy to read as a graphically continuous element across the cut.

Perhaps too the fact that we’re switching our position 180 degrees leads us to expect, wrongly, the sort of reversal we get here—the way that we think our reflection in a mirror is the way we really look. And of course the earlier 180-degree switch, in which no mismatch occurs, probably serves to prime us for the shift in orientation this provides.

Mangold doesn’t mention the cut in his director’s commentary on the Kate & Leopold DVD, but when I asked him he said: “I think of shots as blocks, like legos or words. I don’t want them to resolve–come to an end. . . . Movement cuts work as long as the action is somewhat similar. The tough continuity cuts when you have a mismatch are the still ones.” Even if the mismatch here was accidental, it works very well. More generally, like other mismatches this one obliges us to think about what we see and what we don’t see when we watch a movie.

Hawks’ eyes

Among the many pleasures of Howard Hawks’ movies are their lovely matches on action. Of course his editors had a lot to do with this, but Hawks clearly had to provide the right footage so that it could be precisely matched. Bringing Up Baby (1938) yields a crisp cut as Susan, perched on the constable’s desk, strikes a match. (I show the cuts from a 16mm print; enough of this video stuff.)

Here Hawks seems to rely on what’s been called the two-frame rule: If you’re going to match on action, overlap the action by two frames to show a bit of the action again. This allows the audience time to absorb the fact of the cut and then to see the action as continuous. But Hawks could be quite cavalier about his matches as well. The golfing scene from Bringing Up Baby is full of wild cuts.

The caddies advance and recede, Susan and David are caught in different postures, and at some cuts they’re striding across different parts of the course. These cuts have a swagger about them, as if Hawks is daring us to spot his outrageous cheats. How many of us do?

All these trompe l’oeil effects can be studied psychologically, and prominent researchers who have tested such effects in the laboratory are attending our 11-14 June meeting of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. Dan Levin studies discontinuities in film from the standpoint of “inattentional blindness”; here he’s interviewed by Errol Morris. Barry Hughes of Arizona State University at Tempe has probed the two-frame rule, and he’s talking in Madison as well. Go here for more information; I’ve plugged the event previously here.

Next time, we expect: Secrets of film restoration.

(1) Kurosawa has prepared us for this passage when Kikuchiyo’s sword attacks the bandits earlier in the sequence. There too a shot of his flailing stroke is followed, after a pause on a patch of mud, by a falling horseman. But the calm deliberateness of Kambei’s drawing of his bow enhances the sense of inevitability, I think. Kiku does his damage through furious energy, but Kambei hits his mark thanks to a mature warrior’s almost contemplative precision.

(2) Forget checking these frame counts on DVD. I get several different counts, depending on the player I use. For reasons discussed here, DVDs don’t preserve the original film frames, and in a fast-cut passage you can lose any sense of how many frames the shot lasted.

(3) By the way, Griffith died on 23 July 1948, my first birthday.

(4) For more on this extraordinary movie’s use of discontinuity editing, see Vance Kepley, Jr., The End of St. Petersburg (London: Tauris, 2003).

Creating a classic, with a little help from your pirate friends

DB here:

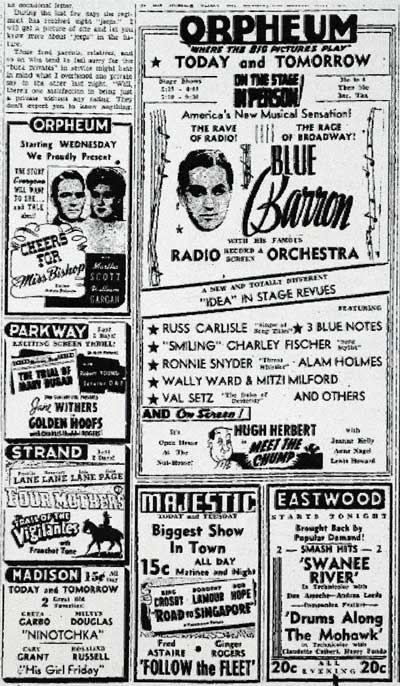

In early April of 1940, His Girl Friday came to Madison, Wisconsin. It ran opposite Juarez, The Light that Failed, Of Mice and Men, and a re-release of Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Pinocchio was about to open. Most screenings cost fifteen cents, or $2.21 in today’s currency.

Before television and home video, film was a disposable art. Except in big cities, a movie typically played a town for a few days. Programs changed two or three times a week, and double bills assured the public a spate of movies—nearly 700 in 1940 alone. People responded, going to the theatres on average 32 times per year. Given the competition, it’s no surprise that His Girl Friday didn’t stand out in the field; it was nominated for no Academy Awards and honored by no prizes. On just a single day in Madison, the cast of His Girl Friday was up against icons like Muni, Colman, March, and Bette Davis.

Nowadays, of course, nearly everyone regards HGF as one of the great accomplishments of the studio system. Most would consider it a better movie than any of the others it played opposite in my home town. A typical example of critical exuberance is Jim Emerson’s comment here. Or read James Harvey’s 1987 encomium:

It would be hard to overstate, I think, the boldness and brilliance of what Hawks has done here: not only an astonishingly funny comedy, but a fulfillment of a whole tradition of comedy—the ur-text of the tough comedy appropriated fully and seamlessly to the spirit and style of screwball romance. His Girl Friday is not only a triumph, but a revelation.

Oddly, this extraordinary film lay largely unnoticed for three decades. How did it become a classic? The answer has partly to do with the rising status of Howard Hawks, the director, among critics. It also owes something to changes in how academics thought about film history. And a little movie piracy didn’t hurt.

An unseen power watches over the Morning Post

Hawks the Artist is a creation of the 1960s. Before that, American film historians almost completely ignored him. Andrew Sarris often reminds us that he’s absent from Lewis Jacobs’ Rise of the American Film (1939), but he’s also missing from Arthur Knight’s The Liveliest Art (1957), the most popular survey history of its day. Apart from press releases and reviews of individual films, there were few discussions of Hawks in American newspapers and magazines. The most famous piece is probably Manny Farber’s “Underground Movies” of 1957, which treats Hawks along with other hard-boiled directors like Wellman and Mann.

From the start, Hawks was more appreciated in France. There film historians acknowledged A Girl in Every Port (1928), in part because of the presence of Louise Brooks, and they usually flagged Scarface (1932) as well, which they could see and Americans couldn’t. (Howard Hughes kept it out of circulation for decades.) But Hawks is barely mentioned in Georges Sadoul’s one-volume Histoire du cinéma mondiale (orig. 1949) and he’s ignored in the 1939-1945 volume of René Jeanne and Charles Ford’s monumentally monotonous Histoire encyclopédique du cinéma (1958).

The essay that marked the first phase of reevaulation was evidently Jacques Rivette’s “The Genius of Howard Hawks” in Cahiers du cinéma in 1953. Inspired by Monkey Business, Rivette’s philosophical flights and you-see-it-or-you-don’t tone helped define the auteur tactics identified with Cahiers’s young Turks. Rivette and his colleagues became known as “Hitchcocko-Hawksians.” The essay, however, doesn’t seem to have been immediately influential. Antoine de Baecque claims that within Cahiers, an admiration for Hawks was controversial in a way that liking Hitchcock was not. (1) It took some years for Hawks to ascend to the Pantheon.

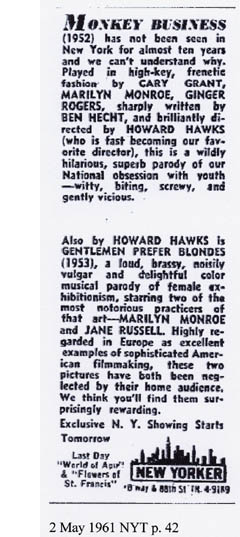

The story of that ascent has been well-told by Peter Wollen in his essay, “Who the Hell Is Howard Hawks?” In France, the Young Turks’ tastes had been nurtured by Henri Langlois, who showed many Hawks films at the Cinémathèque Française. In New York, Andrew Sarris and Eugene Archer had become intrigued by Cahiers but were ashamed that as Americans they didn’t know Hawks’ work. They persuaded Daniel Talbot to show a dozen Hawks films at his New Yorker Theatre during the first eight months of 1961. The screenings’ success allowed Peter Bogdanovich to convince people at the Museum of Modern Art to arrange a 27-film retrospective for the spring of 1962. The package went on to London and Paris, sowing publications in its wake.

The story of that ascent has been well-told by Peter Wollen in his essay, “Who the Hell Is Howard Hawks?” In France, the Young Turks’ tastes had been nurtured by Henri Langlois, who showed many Hawks films at the Cinémathèque Française. In New York, Andrew Sarris and Eugene Archer had become intrigued by Cahiers but were ashamed that as Americans they didn’t know Hawks’ work. They persuaded Daniel Talbot to show a dozen Hawks films at his New Yorker Theatre during the first eight months of 1961. The screenings’ success allowed Peter Bogdanovich to convince people at the Museum of Modern Art to arrange a 27-film retrospective for the spring of 1962. The package went on to London and Paris, sowing publications in its wake.

For the MoMA retrospective, Hawks granted Bogdanovich a monograph-length interview, which was to be endlessly reprinted and quoted in the years to come. (2) Sarris, now knowing who the hell Hawks was, wrote a career overview for the little magazine, The New York Film Bulletin, and this piece became a two-part essay in the British journal Films and Filming. Both Bogdanovich and Sarris made brief reference to His Girl Friday, as did Peter John Dyer in another 1962 essay, this one for Sight and Sound. At the end of 1962, another British magazine, Movie, published an issue on Hawks. At the start of 1963, Cahiers devoted an issue to him, including an homage by Langlois himself. Thanks to the work of Archer, Bogdanovich, Sarris, and MoMA, Hawks was rediscovered.

Sarris provided a condensed case for Hawks in his far-reaching catalogue of American directors, published as an entire issue of Film Culture in spring of 1963. There followed an interview with Hawks’s female performers in the California journal Cinema (late 1963), an appreciation by Lee Russell (aka Peter Wollen) in New Left Review (1964), another Cahiers issue (November 1964), J. C. Missiaen’s slim French volume Howard Hawks (1966), Robin Wood’s Howard Hawks (1968), and Manny Farber’s Artforum essay (1969). There were doubtless other publications and events that I never learned about or have forgotten. In any case, by the time I started grad school in 1970, if you were a film lover, you were clued in to Hawks, and you argued with the benighted souls who preferred Huston. . . even if you hadn’t seen His Girl Friday.

Light up with Hildy Johnson

One of my obsessions in graduate school was the close analysis of films. But I was also interested in whether one could build generalizations out of those analyses. My initial thinking ran along art-historical lines. My Ph. D. thesis on French Impressionist cinema sought to put the idea of a cinematic group style on a firmer footing, through close description and the tagging of characteristic techniques. But that approach came to seem superficial. I wasn’t satisfied with my dissertation; although it probably captured the filmmakers’ shared conceptions and stylistic choices, I couldn’t offer a very dynamic or principled account of formal continuity or change.

Watch a bunch of movies. Can you disengage not only recurring themes and techniques, but principles of construction that filmmakers seem to be following, if only by intuition? As I was finishing my dissertation, reading Russian Formalist literary theory pushed me toward the idea that artists accept, revise, or reject traditional systems of expression. These become tacit norms for what works on audiences. My reading of E. H. Gombrich pushed me further along this path. We should, I thought, be able to make explicit some of those norms. Eventually I would call this perspective a poetics of cinema.

I was assembling my own version of some ideas that were circulating at the time. In the early 1970s, several theorists floated the idea that different traditions fostered different approaches to filmic storytelling. People were seeing more experimental and “underground” work, as well as films from Asia and what was then called the Third World. Being exposed to such alternative traditions helped wake us up to the norms we took for granted. The mainstream movie, typified by what Godard called “Hollywood-Mosfilm,” seemed more and more an arbitrary construction.

People began examining films not as masterworks or as expressions of an auteur, but as instances of a representational regime. Films became “tutor-texts,” specimens of formal strategies that were at play across genres, studios, periods, and directors. Again, the French pointed the way, particularly Raymond Bellour, Thierry Kuntzel, and Marie-Claire Ropars. At the same moment, Barthes’ S/z was published in English, and it seemed to provide a model for how one might unpick the various strands of a text, either literary or cinematic. Screen magazine was a conduit for many of these ideas in the English-speaking world.

Some of my contemporaries disdained the mainstream cinema and moved toward experimental or engaged cinema. Others read the dominant cinema symptomatically, for the ways it revealed the contradictions of ideology. I learned from both approaches, but I believed that the current analysis of how Hollywood worked, even considered as a malevolent machine, was incomplete. Could we come up with a more comprehensive and nuanced account of the mainstream movie? This line of thinking was already apparent in non-evaluative studies of form and style, such as essays by Thomas Elsaesser, Marshall Deutelbaum, and Alan Williams. (3)

At some point in graduate school at the University of Iowa, between fall 1970 and spring 1973, I saw a screening of His Girl Friday. I fell in love with its heedless energy. It seemed to me a perfect example of what Hollywood could do.

In my admiration I was channeling the cultists. Rivette, in a review of Land of the Pharoahs: “Hawks incarnates the classical American cinema.” (4) Bogdanovich: He is “probably the most typical American director of all.” Richard Griffith, then film curator of MoMA, had slighted Hawks in his addendum to Paul Rotha’s The Film Till Now, but in his foreword to the Bogdanovich interview he caved to the younger generation: “Hawks works cleanly and simply in the classical American cinematic tradition, without appliquéd aesthetic curlicues.” As for HGF, in the 1963 Cahiers tribute Louis Marcorelles called it “the American film par excellence.”

Praising Hawks, and HGF specifically, was part of a larger Cahiers strategy to validate the sound cinema as fulfilling the mission of film as an art. What traditional critics would have considered theatrical and uncinematic in HGF—confinement to a few rooms, constant talk, an unassertive camera style—exactly fit the style that Bazin and his younger colleagues championed. (For more on that argument, see Chapter 3 of my On the History of Film Style.)

These niceties didn’t inform my reaction at the time. I was already primed to like Hawks, though, having caught what films I could after reading Wood et al. (During my initial summer in Iowa City, I went to a kiddie matinee of El Dorado and got Nehi Orange spilled down my neck.) On my first viewing His Girl Friday delighted me with the sheer gusto of the pace and playing. Clearly the cast was having fun. A press release sent out before the film claimed that during one scene, with Cary Grant dictating frantically to Rosalind Russell, she cracked him up by handing over what she had typed.

Cary Grant is a ham. Cary Grant is a ham. Now is the time for all good men to quit mugging. You don’t think you can steal this scene, do you—you overgrown Mickey Rooney? The quick brown fox jumps over the studio. Cary Grant is a ham.

Even discounting this tale as PR flackery, we know from Todd McCarthy’s excellent biography that Hawks encouraged competitive scene stealing and wily improvisation. Russell hired an advertising copywriter to compose quips she could “spontaneously” conjure up in her duels with Grant.

If there was a “classical Hollywood cinema”—a phrase that was in the early ’70s coming into circulation via Screen—the buoyant forcefulness of His Girl Friday embodied it. Here was a film pleasure-machine that hummed with almost frightening precision. What else do you expect from a director who studied engineering and whose middle name is Winchester?

Production for use

When I saw His Girl Friday, little had been written about it. Despite Langlois’ screenings, before the 1962 touring program, the Cahiers critics seemed to have had limited access to Hawks’ prewar work. His Girl Friday wasn’t released theatrically in France until January of 1945 (not perhaps the most propitious moment), and it apparently made no long-lasting impression on the intelligentsia. I can’t find any critical commentary on it in French writing before the 1963 issue of Cahiers.

In the United States, HGF earned Hawks a courteous write-up in the New York Times by, of all people, Bosley Crowther, (5) but it wasn’t acknowledged as an instant classic like Mr. Smith Goes to Washington or The Philadelphia Story. After the initial flurry of mostly favorable reviews, the movie seems to have been forgotten until Manny Farber’s 1957 essay, and even there it’s only mentioned in a list. Interestingly, it wasn’t screened during the 1961 New Yorker series. Robin Wood’s sympathetic but not uncritical discussion in his Hawks book of 1968 seems to have been the most comprehensive account available since the movie’s release.

At about the time Wood’s book was published, something big happened. Columbia Pictures failed to renew its copyright, and His Girl Friday fell into the public domain.

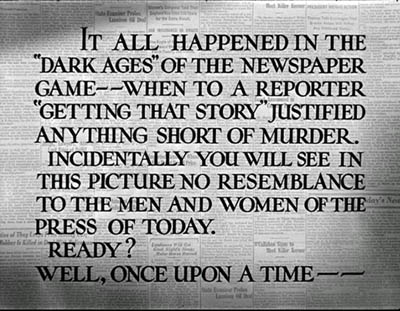

Entrepreneurs made dupe copies, in quality ranging from okay to terrible. You could rent one for peanuts and buy one for only a little more. Some of these bleary prints have been telecined and turned into the DVD versions of the film that fill bargain bins today. After I got to the University of Wisconsin, where Hawks films stoked the two dozen campus film societies, I bought a public domain print. The copy was better than average, although it lacked the fairy-tale warning title at the start. From 1974 on, I showed the poor thing constantly.

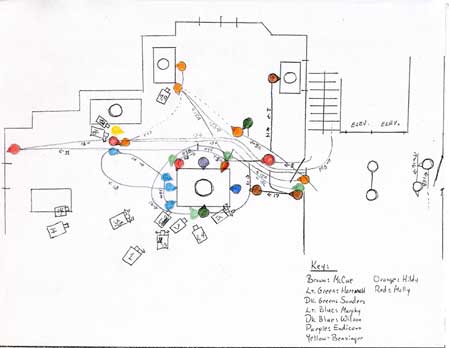

In Introduction to Film, taught to hundreds of students each semester, HGF illustrated some basic principles of classical studio construction. It had the characteristic double plotline (work/ romance), a careful layout of space, an alternation of long takes and quick cutting, manipulation of point-of-view, judicious depth framing (see frame below), and cascading deadlines. In Critical Film Analysis, I asked students to map out scenes shot by shot (see diagram above) and to show how different approaches (genre-based, feminist, Marxist) would interpret the film. In a seminar on “the classical film and modernist alternatives” HGF grounded comparisons with Bresson, Dreyer, Ozu, Godard, and Straub/Huillet. By steeping ourselves in such alternative traditions, could we resist the naturalness of Hollywood artifice?

The movie became a UW staple. It went into the first edition of Film Art (1979) as an instance of classical construction; even the telephones were scrutinized. Marilyn Campbell’s paper from our seminar was published in 1976. (6) Over the years, many of our grad students, exposed to the film in our courses, have gone on to use it in their teaching.

Doesn’t have to rhyme

I can’t let HGF go. I still use moments to illustrate points in my writing and lectures. Madison colleagues and I swap banter from it; Kristin and I talk in Hawks-code, as she explains here. I’ve been told that grad students in another PhD program compared our program to the Morning Post pressroom (favorably or not, I don’t know). Thanks to Lea Jacobs, the invitation to my retirement party was surmounted by a picture of Walter Burns whinnying into his phone.

But seriously, His Girl Friday, isn’t a bad guide to a lot of social life. You can learn a lot from its Jonsonian glee in selfishness and petty incompetence, as well as its sense that virtue resides with the person who has the fastest comeback. Think as well how often you can use this line in a university setting:

If he wasn’t crazy before, he would be after ten of those babies got through psychoanalyzing him.

I’m not claiming special credit for the HGF revival, of course. Plenty of other baby-boomer film professors were teaching it. It became a reference point for feminist film criticism, particularly Molly Haskell’s From Reverence to Rape (1974), and it has never lost its auteurist cachet. Richard Corliss’s 1973 book on American screenwriters flatly declared that “His Girl Friday is Hawks’s best comedy, and quite possibly his best film.”

Most important of all, TV stations were screening their bootleg prints. HGF didn’t become a perennial like that other public domain classic It’s a Wonderful Life, but its reputation rose. Its availability pushed the official Cahiers/ Movie masterpieces Monkey Business and Man’s Favorite Sport? into a lower rank, where in my view they belong.

Once HGF became famous, the proliferation of shoddy prints became an embarrassment. In 1993 it was inducted into the National Film Registry, which gave it priority for Library of Congress preservation. Columbia managed to copyright a new version of the film. A handsomely restored version was released on DVD, and a few years back I saw a 35mm copy whose sparkling beauty takes your breath away.

The lesson that sticks with me is this. If Columbia had renewed its copyright on schedule, would this film be so widely admired today? Scholars and the public discovered a masterpiece because they had virtually untrammeled access to it, and perhaps its gray-market status supplied an extra thrill. Thanks mainly to piracy, His Girl Friday was propelled into the canon.

Epilogue

In May of 1940, His Girl Friday hung around Madison, shifting from its first venue, the Strand downtown, to an east side screen, the Madison. The film came back in late September to yet a third screen, the Eastwood (now a music venue).

HGF was revived in March of 1941, as the second half of a double bill at the Madison (bottom left below). Check out the competition: some killer re-releases from Ford, Lubitsch, Astaire-Rogers, and Hope-Crosby. A Midwestern city of 60,000 could become its own cinémathèque without knowing it.

(1) Antoine de Baecque, Cahiers du cinéma: Histoire d’une revue, vol. 1: À l’assaut du cinéma, 1951-1959 (Paris: Cahiers du cinéma, 1991), 202-204.

(2) Bogdanovich has published a much fuller version in Who the Devil Made It? (New York: Knopf, 1997) , 244-378.

(3) Thomas Elsaesser, “Why Hollywood?” Monogram no. 1 (April 1971), 2-10; “Tales of Sound and Fury,” Monogram no. 4 (1972), 2-15; Marshall Deutelbaum, “The Structure of the Studio Picture,” Monogram no. 4 (1972), 33-37; Alan Williams, “Narrative Patterns in Only Angels Have Wings,” Quarterly Review of Film Studies 1, 4 (November 1976), 357-372.

(4) Jacques Rivette, “Après Agesilas,” Cahiers du cinéma no. 53 (December 1955), 41.

(5) Bosley Crowther, “Treatise on Hawks,” New York Times (17 December 1939), 126. “He brings to his work as a director the ingenious and calculating brain of a mechanical expert. . . . He pitches into the job just as though he were building a racing airplane.”

(6) Marilyn Campbell, “His Girl Friday: Production for Use,” Wide Angle 1, 2 (Summer 1976), 22-27.

For a helpful collection of conversations with the master, see Howard Hawks Interviews, ed. Scott Breivold (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2006). Go here for a 1970s piece by James Monaco on then-current controversies.

PS 24 Feb: Jason Mittell responds to my post with some nice nuancing and draws out the implication for copyright issues: contrary to current media policy, the wider availability of a work can actually enhance its value.

Coming attraction: Kristin is preparing a blog entry commenting on fair use in the digital age.