Archive for the 'Directors: Hitchcock' Category

When Hollywood ruminates: Calm after THE MORTAL STORM

The Mortal Storm (1940).

DB here:

We don’t usually think of classic studio cinema as particularly contemplative. But many films open up spaces for quiet reflection on what we’re seeing, or have seen. In the 1940s, that tendency owed a good deal to the ways that Hollywood became, to put it roughly, more novelistic.

Movies had been based on novels for many decades, but in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, I claimed something more specific. I think that many 1940s filmmakers became more acutely aware of sound film’s capacities for manipulating time and point of view. These are novelistic techniques par excellence, distinctly different from the largely “theatrical” conceptions of presentation that we find in most studio cinema of the 1930s. Films turned inward, probing perceptions, memories, and dreams. If you need a storytelling twist, one journalist cracked, just call it psychology, and it will get by.

Of course, there are plenty of precedents for time and POV shifts in early decades. Still, I wanted to show that between 1939 and 1952 many major options emerged and were developed in ambitious directions. The results left a legacy. Today, when flashbacks are common and we easily grasp elaborate shifts in viewpoint, our films rework the possibilities refined and consolidated in the 1940s.

One stretch of the book considered some films from early-to-mid 1940 that offered glimpses of innovations we’d see in later years. Married and in Love, One Crowded Night, Stranger on the Third Floor, and Edison, the Man previewed techniques that would dominate the next decade. Particularly chock-full of storytelling ideas, I argued, was Our Town, a daring transposition of 1930s theatrical devices into the key of cinema.

Missing from my roster, though, is The Mortal Storm, a film that went into release in June of 1940. I had neglected to rewatch it when writing the book. A couple of weeks back I caught up with it during a screening at our Cinematheque. Restored by UCLA, it fairly shimmered off the screen.

How could I not have remembered the stunning closing sequence? It’s a bundle of narrative strategies that would get elaborated in the years to come. And it achieves its effect from being somber, slow, and based on human absence. In this epilogue, the movie pauses to think.

To talk about this passage and its counterparts, I have to parade plenty of spoilers. Sorry. But at least you get video.

Emptying the nest

The Mortal Storm.

The plot starts in Germany at the moment of Hitler’s ascension to power in 1933. Elderly Viktor Roth is a much-loved Jewish professor of medicine. His household includes his stepsons Otto and Erich, his wife Emilia, and their daughter Freya. Two other young men are close to the family: Fritz, who aspires to marry Freya, and Martin, a farm boy training to be a veterinarian.

Otto, Erich, and Fritz become enthusiastic Nazis, but Freya draws closer to Martin, who quietly resists the growing bigotry in their small town. Professor Roth is arrested and killed. Martin and Freya, now deeply in love, try to escape by ski to Austria. A squad of soldiers, under Fritz’s direction, fires on them. Freya is killed.

In the crucial scene, Fritz returns to the family home to tell Otto and Erich.

The sequence blends several narrational choices. Most obvious is the camera movement that seems to drift off on its own. It is, we might say, semi-subjective. It suggests Otto’s slow walk through the now-empty home, but it isn’t clearly marked as his optical POV. The opening stretch of the shot shows him pacing more or less obliquely to us, before the camera pans and tracks to the table and beyond.

The framing insistently keeps Otto offscreen. Only the sound of his footsteps and pauses suggest that he’s present, off left or behind us, at each station of the shot.

As the camera drifts along, we get auditory flashbacks to earlier scenes, three at the table, and one echoing the Professor at his lectern. Flashbacks are characteristic features of 1940s cinema, and purely auditory ones will come into prominence, as in The Fallen Sparrow (1943). Since we’ve seen the action these flashbacks evoke, they’re as much flashbacks for us as for Otto. Indeed, Otto has been a minor character in the story. His walk triggers them, but his absence from the frame makes it easier for us to project our memories onto these spaces.

The transition among the flashbacks prepares for Otto’s defection. The voice shifts from Freya, whose death Otto is grieving, to the men challenging authority. We hear Professor Roth urge youth forward, and Martin advocating peace and free thought. These later moments seem to crystallize Otto’s change of heart. Dwelling a bit on the statuette of Youth carrying the torch of knowledge suggests that Otto may become inspired to take up his father’s commitment to humanism.

At the climax of the shot, the camera frames the staircase (another icon of 1940s cinema) and starts to back up. This can hardly be Otto’s optical viewpoint. The rapid footsteps suggest that he has left the house by striding out, as it were, behind us. The sound of a closing door confirms our inference. He has left us behind.

As he does in the final moments, when Otto’s flight is depicted as footprints in the snow. Perhaps, now that he has become revolted by the cruelty of Fritz and the Nazi regime, he will take up resistance in Martin’s spirit.

Accompanying the shots of the footprints is the voice-over narrator whom we heard at the film’s start. (Such narrators proliferate in 1940s movies.) His speech, from a poem called “The Gate of the Year,” echoes the visuals: a man “at the gate,” the prospect that one may “tread safely into the unknown.” In giving up Nazism, Otto is giving up home.

The camera tilts up to show the empty house. The snow-encased home is quite different from the bustling view we saw at the film’s start, when the postman delivered gifts for Professor Roth.

Hitler has destroyed the family. Still, as the snow buries the footprints, the narrator urges that divine guidance can provide safety for Otto’s escape, and perhaps a decision to fight Nazism.

We don’t normally think of MGM as a hotbed of cinematic innovation in the studio years. But the company had its moments (here and there), and this is one of them. The Mortal Storm‘s play with time (flashbacks, the solemn duration of the house tour) and viewpoint (Otto triggering some bits of remembered dialogue) resembles what we might get in a psychologically slanted novel of the time. We’re given a few minutes to breathe deeply and think about what we’ve seen, and to build up expectations about what Otto may do.

The house as memory vessel

The Miniver Story (1950).

One section of Reinventing Hollywood analyzes Enchantment (1948), a film narrated by a house. The house presents itself as a cozy repository of the memories of several generations. More generally, houses are powerful images in 40s films; think of Tara, Manderly, the estate in Dragonwyck, and the Gothic mansions of Jane Eyre, Gaslight, and The Spiral Staircase. Often they’re presided over by ominous portraits, as Steven Jacobs and Lisa Colpaert have shown.

One lesser-known example is House of Strangers (1949), directed by Joseph Mankiewicz. This story of an Italian immigrant who has become the head of a big bank is framed by his son Max returning to their massive home. The bulk of the film is given in flashback, but the flashback is launched by a wandering camera accompanied by “M’apparti tutt’amor” (from the opera Martha) playing on the phonograph. After a trip up the stairs we are taken via dissolve to the patriarch singing it in his bath.

The plot’s central section treats the lyric (“You all seem to love me”) with doubled implication: Gino’s reckless loans endear him to his customers, but his sons resent his power over them. The long flashback ends at Gino’s funeral, passing from the portrait in the past to the phonograph and to his son Max, brooding under the looming picture.

The huge Minafer mansion is practically a character itself in The Magnificent Ambersons (1942). One of Welles’ late script versions envisioned a climax in which George, distraught by the shabbiness of their neighborhood, would pass numbly through the house, and our sense of it would be given through his eyes.

145 FULL SHOT of the Amberson Mansion, seen from behind George who is standing in front of camera. He starts walking toward the mansion. CAMERA FOLLOWS, moving faster than he does and soon is so close to him that his body creates a dark screen for a DISSOLVE TO:

146 CAMERA is on the steps of the Amberson Mansion, MOVING up to the door and STOPPING. George’s hands enter the scene, insert a key in the lock, turn it —

147 On the Narrator’s words, “move out” the door opens and CAMERA MOVES thru it into the house.

MOVING SHOT as CAMERA WANDERS SLOWLY about the dismantled house — past the bare reception room; the dining room which contains only a kitchen table and two kitchen chairs, up the stairs, close to the smooth walnut railing of the balustrade. Here CAMERA STOPS for a moment, then PANS down to the heavy doors which mask the dark, empty library. HOLD on this for a short pause, then CAMERA PANS back and CONTINUES, even more slowly, up the stairs to the second floor hall where it MOVES up to the closed door of Isabel’s room. The door swings open and we see Isabel’s room is still as it always has been; nothing has been changed. FADE OUT

This passage is strikingly similar to what we see in The Mortal Storm. True, the cues for George’s optical viewpoint are more explicit than what Borzage gives us for Otto. But Welles is subtler along another dimension. He counts on our remembering earlier scenes without benefit of auditory flashbacks. The camera revisits the reception area we saw during the ball, the dining room where George challenged Eugene Morgan, and the staircase where George and Fanny quarreled, before coming to rest in Isabel’s room, where we saw her waste away and die. We are asked to supply our own flashbacks.

Some of this POV passage might have been filmed, but it wasn’t retained in Welles’ final version, even before RKO’s mangling. In the film as we have it, only Welles’ lead-in and conclusion remain. The narrator supplies a moving-camera montage, as George registers the changes in Amberson Avenue.

The street sequence ends in darkness and tracks back from George kneeling at the bed begging forgiveness. The fact that the shot starts from his darkened head reinforces the subjectivity of the montage.

Welles’s handling is novelistic in the sense of wrapping a character’s flowing impressions inside an omniscient verbal commentary using free indirect discourse (“Tomorrow they were to move out”). George’s moments of rueful meditation are moments for us as well.

Like the narrator that closes The Mortal Storm, this voice is external to the story world. But the same house-haunting effect can be achieved by a narrator who lives in that world. Coupled with the wandering camera, this can turn our view of a scene in the present into a view of the past–or of an eternal future.

The example I have in mind is from The Miniver Story (MGM again, 1950). In Reinventing, I analyze a sequence that creates layers of time: Clem Miniver’s voice-over in our present, an image of he and Kay in the past, and references in the commentary to periods still earlier than what we see. (The clip of this sequence is online here.) At the end of the film, after the Minivers have married off their daughter Judy to Tom, they must face Kay’s impending death from cancer.

The final sequence shifts from the day of the wedding to a kind of timeless realm in which Kay’s spirit lives on. Again, camera movement suggests an invisible presence.

By 1950, we’ve had several permutations. The camera wanders without verbal narration (music alone in House of Strangers). It does so with auditory flashbacks (The Mortal Storm). It does so with a nondiegetic (external) narrator (The Magnificent Ambersons). And it does so with a diegetic (story-world) narrator (The Miniver Story). I try to show in the book that 1940s filmmakers swiftly expanded, even exhausted, menu options involving many storytelling techniques.

Trust Hitchcock to give us yet another variant, and in a tour de force at that.

Enough rope

In the eleven shots of Rope (1948), set almost completely in an apartment, the camera’s peregrinations are usually motivated by character movement or simple track-ins and track-outs. At the climax, though, the camera cuts loose. Sort of.

Brandon and Phillip have strangled their friend David and hidden his body in a chest in their living room. They’ve ghoulishly used the chest as a buffet table for their afternoon party. After the party, one guest, their prep school teacher Rupert Cadell, has returned. He suspects that something bad has happened to David. Rupert challenges the pair and sketches out how they might have murdered their friend.

His reconstruction isn’t wholly correct. David wasn’t bludgeoned, and apparently the armchair played no role. What’s fascinating is that the camera supplies a hypothetical, virtual flashback. As in our earlier examples, David becomes an invisible guest, summoned up by the mobile frame.

The camera traces out the action Rupert posits, emphasizing the hall closet (where Rupert earlier discovered David’s hat) and edging eventually toward the chest. At that point Brandon steps in, with his hand tensing around the pistol in his pocket. He stands in front of the drinks table.

That’s the climax of the shot. Cut to a shot of Rupert. He seems to intuit that he should avoid mentioning the chest, so he proposes that they might have carried the body out of the building. As the camera traces out that possibility, Brandon steps back into the frame to confront Rupert.

Here I think Hitchcock made a mistake. At the end of the first shot, Brandon and his pistol are quite close to Rupert, near the drinks table. But in the followup shot, he’s not visible when the camera pans left past the table to enact the scenario Rupert is considering. Brandon would have had to skip backward like the Road Runner to get as far away as he is when he steps back into the frame in the second shot.

Still, the important effect is the representation of Rupert’s thinking. Goaded by Brandon, he ponders how the crime might have been committed, and the camera carves into space to reveal the scheme he conjures up. A sort of flashback? Yes, but an unreliable replay, left largely to our imagination. Semi-subjective? Yes, since when we cut to Rupert he seems to be staring down at the chest. Yet the camera is too free-ranging to be purely Rupert’s optical POV. He’s not moving around, as Otto is in the Mortal Storm sequence.

In this most “theatrical” of movies, Hitchcock manages to give us a verbal-visual flow that is something like a cinematic equivalent of the novelist’s conditional perfect tense. If Brandon and Phillip had killed David, they could have done it this way. The camera enacts a speculative train of thought. Call it psychology.

One thing I shouldn’t ever forget: Hollywood in the Forties is a booming rush of visual, auditory, and narrative ideas. In the approximately 5,655 features released in the period I marked off, there are surely many other startling instances of creative craft. I’ll keep looking.

Thanks as ever to our Wisconsin Cinematheque for fine programming under the auspices of Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser and excellent projectionist Roch Gersbach. Thanks as well to Joe McBride for sharing material on The Magnificent Ambersons. More on Ambersons can be found here and here.

The Mortal Storm‘s “novelistic” final moments owe nothing to its source, Phillis Bottome’s The Mortal Storm (1938). An earlier version of my ideas about Enchantment are here.

Chapters 4 through 6 of Patrick Keating’s The Dynamic Frame: Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood offer a careful survey of creative choices facing filmmakers of the period, along with explications of their “practical theories” about cinematography. After writing this entry, I learned that Patrick has also made a fine video essay on the Ambersons sequence.

For earlier blogs on related subjects, see the category 1940s Hollywood.

PS 2 March 2020: Patrick Keating reminds me of another 1940 release I should have mentioned: Hitchcock’s Rebecca. When Maxim narrates his confrontation with Rebecca, the camera moves autonomously to “replay” the scene. It anticipates my Rope example, except that Maxim is recounting what really happened, while Rupert is sketching out his (partially inaccurate) reconstruction of David’s death. Still, though, it’s another variant on an emerging pictorial convention. Thanks, Patrick!

PS 2 March 2020, later: Thanks also to John Belton, who writes to remind me not only of the Rebecca scene but a comparable camera movement in Under Capricorn. Crowdsourcing works.

Rope (1948).

Il Cinema Ritrovato: More and more

Il Cinema Ritrovato Book Fair (photograph Margherita Caprilli).

Kristin here:

I mentioned in my entry on the African thread at this year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato that I filled in blank spaces in my program with a miscellany of intriguing films. Here are some of those films I saw, and others that David saw.

O Pão (1959)

Manoel de Oliveira’s first film, the gorgeous black-and-white documentary short, Douro, Faina Fluvial, was released in 1931. His last, Um Século de Energia, another documentary short, came out in 2015, the year of his death aged 106 (as did Visita ou Memórias e Confissões, a deliberately posthumous legacy film shot in 1982). That’s an 84-year career. I doubt any other filmmaker can claim as much.

Initially that career proceeded in fits and starts. He made more documentary shorts in the 1930s and then a black-and-white feature, Aniki-Boko (1942), during the war under an authoritarian regime. After the war he could not find funding and decided to study color filmmaking in Germany. During the 1950s he applied his resulting expertise to two documentaries: O Pintor e a Cidad (“The Painter and the City,” 1956) and O Pão (Bread). A beautiful print of the latter was shown in this year’s Ritrovati e Restaurati thread. It was to be his last film before he turned to feature filmmaking, though he never entirely gave up documentaries, particularly near the end of his life.

This hour-long film slowly follows the entire progress of bread, from wheat-fields to milling to baking to consumption. The images, whether in field or factory, are lovely, showing that Oliveira had indeed learned a great deal about color.

There is no voice-over narration, even during a lengthy scene in a large mill where technicians perform mysterious tests on samples of flour. The slow progression creates a soothing, almost mesmeric tone. Only toward the end does some social criticism emerge. A hungry urchin stealthily retrieves a roll dropped by a shopper, only to have it snatched away by a little street thug. Clearly bread, despite the lyricism of its production, is not for everyone.

Ghazieh-e Shekl-e Avval, Ghazieh-e Shekl-e Duvvum (1979)

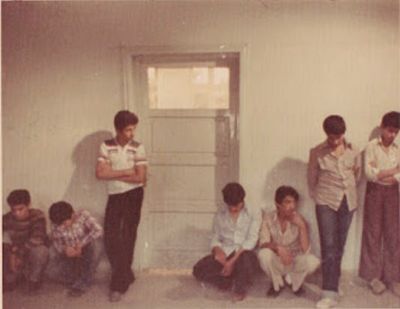

Another must-see was Abbas Kiarostami’s early film, First Case, Second Case, also presented in the rediscovered-and-restored thread. Like Oliveira, Kiarostami began in documentary work. This remarkable film was started before the 1979 Iranian Revolution and finished after it–and then banned.

The film’s beginning rather resembles other Kiarostami openings, with a simple scene in a classroom. A teacher drawing the anatomy of an ear on a blackboard is interrupted by a knocking noise caused by one of his students. No one confesses or reveals who caused the noise, and the teacher suspends seven of the boys, who spend the next days in the hall outside the classroom.

This scene is revealed to be a 16mm film being shown to a succession of teachers, government officials, religious leaders, and the fathers of some of the boys. In the latter cases, some variant of the framing above is shown, with an arrow pointing to the son of the father being interviewed. Unseen, Kiarostami asks them the same question: did the boys do right in refusing to reveal who disrupted the class? Some of these interviewees became key figure in the Islamic Revolution. (Jason Sanders’ program notes for a screening of the film provide some information about this historical context.)

This “documentary” has of course been carefully staged. A page from Kiarostami’s script reveals how he designed the passing days of the boys’ suspension, with different ones standing or sitting each time. The illustration is from Ritrovato programmer Ehsan Khoshbakht’s blog entry on the film, where he credits First Case, Second Case with introducing the interview technique into the director’s work.

This first case shows the boys maintaining their refusal to identify the culprit. In a new scene, the second case, an alternative outcome shows one of the boys naming the guilty classmate to his teacher. Again, Kiarostami interviews many of the same people as to whether they believe the boy’s decision can be morally justified.

If not as charming as some of Kiarostami’s later work, First Case, Second Case contains a familiar combination of complexity and simplicity, as well as a fascination with people telling their own versions of events.

The film has been picked up by Janus in the USA, which should mean that it becomes available from Criterion on Blu-ray and/or its streaming service, The Criterion Channel.

Twelve O’Clock High (1949)

In recent years, Il Cinema Ritrovato has featured the films of a major Hollywood director as one of its main threads. This year it was Henry King. I managed to miss nearly all of his films. In part I feared that, since the auteur du jour is always one of the the more popular items in the program, the screenings would be crowded. Word of mouth suggested that they were.

Still, I had an afternoon free, and I wanted to guarantee myself a good seat for Varda par Agnès, showing later in the day. I went to an earlier screening in the same theater, and I was glad I did. Twelve O’Clock High is an impressive and entertaining film, if not an outright masterpiece.

Fitting into David’s set of innovations typical of the 1940s, the action is enclosed by a framing situation. A man we eventually discover was an American officer posted in England during World War II bicycles out into the countryside and visits the derelict remains of the military airport where he served. (Above, played by Dean Jagger in a role that won him a best-supporting-actor Oscar).

For a long time the story concentrates on General Frank Savage (Gregory Peck), who takes over command of an underperforming bomber unit in the same air station we saw at the beginning. He proves an absolute stickler for discipline, initially alienating the pilots he commands. Eventually he wins their respect, of course, and he learns to unbend a bit.

Eventually a series of air battles occur, with some very impressive and genuine combat footage, including aerial views of bombs exploding on their German targets. The film was presented in a nearly pristine 35mm print, which certainly contributed to my pleasure at having ended up at that screening somewhat by chance.

Faubourg Montmartre (1931)

I definitely planned from the start to see this film. I very much admire director Raymond Bernard’s 1932 World War I drama Wooden Crosses, his next feature after Faubourg Montmartre. Indeed, I had done a video on it for The Criterion Channel (“Observations on Film Art” #16 “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses“)

While a slighter film than Wooden Crosses, Faubourg Montmartre is quite stylish and technically impressive, considering that it was Bernard’s first sound film. In it he abandons his concentration during the silent era on historical epics (his best-known being The Miracle of the Wolves, from 1924).

Here he tackles a melodrama in a contemporary setting, centering around Ginette, a somewhat naive young working-class woman, played by popular star Gaby Morlay. She and her older sister Céline live and work in the titular district of Paris, the disreputable area of cheap entertainment and brothels. Céline works as a prostitute but tries to protect Ginette from such a life. Becoming more dependent on drugs, however, she nearly dupes Ginette into following her into prostitution.

Despite its grim setting, the film has many light moments, mostly provided by the amiable Morlay. It also contains some impressive musical numbers, one a variety number by Florelle and a café song about prostitution by Odette Barencey.

The film was yet another in the festival’s Ritrovati and Restaurati thread.

Georges Franju

There was an unaccustomed focus on documentaries this year, which presumably was the occasion for devoting a small thread to Franju. Of the thirteen shorts which he made or at least is tentatively credited with (most of them commissioned documentaries), eleven were shown. Judex, his fiction feature paying homage to the serial of the same name by Louis Feuillade, was also on the program.

I tried to see all the Franju shorts, since only Le Sang des bêtes (above) and Hôtel des Invalides are well-known in the US. The prints shown ranged widely in quality, some being in 35mm and some 16mm. En passant par la Lorraine was almost unwatchable, though most of the rest were in varying degrees acceptable.

The most interesting revelations were perhaps Mon chien (1955), a melancholy narrative based on the common habit of people abandoning their pets in the countryside. The amazingly callous parents of the little heroine dump her beloved German shepherd in the woods on their way to a vacation spot. The film follows the faithful animal’s trek home, only to find a locked house and a dog-catcher waiting. An empty cage signals that the animal was euthanized, with the voiceover of the girl calling forlornly for her pet. The other was Les poussières (1954), a lyrical survey of many kinds of dust generated in the world, ending in a strong anti-pollution message.

It was a pleasure to see this body of work brought together, but the screenings also demonstrate the pressing need to restore many of these films.

A Gabin tribute

DB here (with films I saw in boldface):

Jean Gabin has become emblematic of French cinema from the 1930s and after, so the several films devoted to him were welcome. Programmer Edward Waintrop included the classic Pépé le Moko (1936) but correctly assumed he didn’t have to show this crowd La Grande Illusion (1937), La Bête Humaine (1938), and Le Jour se Lève (1939). Edward’s catalog entry wisely emphasized how much Gabin owed to Julien Duvivier, an underrated director who helped the young actor find starring roles.

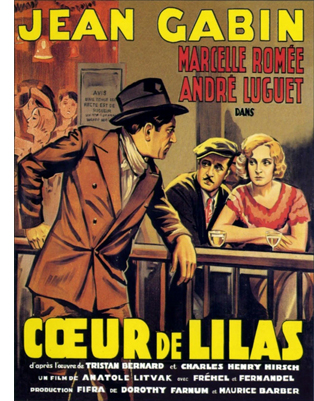

From the heroic thirties, we got the less-seen but still fabled Cœur de Lilas (1931), in which a detective disguises himself as a workman and plunges into the underworld to investigate a murder. The chief suspect, Lilas, is protected by the surly Gabin.

From the heroic thirties, we got the less-seen but still fabled Cœur de Lilas (1931), in which a detective disguises himself as a workman and plunges into the underworld to investigate a murder. The chief suspect, Lilas, is protected by the surly Gabin.

In her book on popular song in French cinema, our colleague Kelley Conway has written a superb analysis of Cœur de Lilas, and you can find a clip of Gabin’s big musical number here. Director Anatole Litvak handles his performance in a long tracking shot that keeps our attention fastened on Gabin’s half-scornful, half-boastful mug as he spits out lines about his girlfriend’s bedroom calisthenics (“The rubber kid. . . She dislocates you”).

Gabin plays the third point of a love triangle in Cœur de Lilas, but he’s somewhat more central to the lesser-known Du Haut en Bas (1933), a sort of network narrative that reminds us that The Crime of M. Lange (1936) isn’t the only film tracing the tangled passions in a courtyard community. More easygoing here but still a force to be reckoned with, Gabin plays a footballer with his eye on an aspiring teacher forced to work as a maid. Other plotlines, including Michel Simon’s raffish wooing of his landlady, intermingle in this thoroughly agreeable movie by the great G. W. Pabst.

A generous sampling of Gabin’s later career included La Marie du Port (1949), Le Plaisir (1951), Maigret tend un piège (1957), and the brutal Simenon adaptation Le Chat (1970), the first film I saw on my first visit to Paris. En Cas de Malheur (1957), an efficient plunge into sex and crime by Autant-Lara, features Gabin as a prestigious but dodgy lawyer drawn to the pouting self-regard of Brigitte Bardot. In youth and age, as a sort of French Spencer Tracy, Gabin could exude both relaxed joie de vivre and stolid menace. An icon, as we say.

Americana, urban and rural

State Fair (1933).

Speaking of Spencer Tracy, it was a pleasure to see this Milwaukee native in a long-neglected racketeer drama. Quick Millions (released May 1931) arrived in the middle of the first big gangster cycle and was overshadowed by two Warners hits, Little Caesar (January 1931) and The Public Enemy (May 1931). As part of Dave Kehr’s welcome second Fox cycle, Quick Millions had its own pungent force.

It traces the familiar trajectory of a working stiff, trucker “Bugs” Raymond, who claws his way to the top of the mob. Thanks to blackmail and crooked labor maneuvers (“The brain is a muscle,” he tells his moll), he winds up triggering a spate of gangland killings that eventually swallows him up.

Quick Millions was noticed as one of the earliest films to find a smart tempo for talkies, one that relies less on long speeches than snappy scenes delivering one point apiece. The passage of time is signaled by changing license plates, and the ending is a shrug, shoving Bugs’ death offscreen and giving him none of the tragic flourishes of Little Rico or Tom Powers. For almost every scene, the little-known director Roland Brown finds an unexpected twist in visuals or performance . Who else would film a sidling George Raft jazz dance from a high angle and then supply inserts of his legs, from behind no less?

Fox found more success with a folksy Grand Hotel variant based on the popular novel State Fair (1932). Henry King’s 1933 film was planned as an “all-star” vehicle, and it did boast Will Rogers, Janet Gaynor, and Lew Ayres. An Iowa family heads to the fair, aiming for blue ribbons in pickle preserving and hog-fattening. The son has a surprisingly carnal affair with a trapeze artist, while the daughter meets a roguish reporter who makes her rethink her engagement to a hick back home. State Fair‘s script gives the plot a happier ending than the book did, but that’s not necessarily a problem; we want these kind souls to enjoy a bit of glory.

Henry King became famous for rustic realism with Tol’able David (1921), a model for Soviet filmmakers, and Ehsan Khoshbakht’s King retrospective reminded us that he worked this vein a long time. From 1915 Twin Kiddies (a Marie Osborne vehicle) to Wait ‘Till the Sun Shines, Nellie (1952), this loyal Fox craftsman showed himself, like Clarence Brown at MGM, an adaptable director with an unpretentious gift for celebrating small-town life.

Still more, more…

Under Capricorn (1949).

I could go on about other films, such as Zigomar: Peau d’Anguille (“Zigomar, the Eelskin,” 1912), Victorin Jasset’s forerunner of Feuillade’s delirious master-criminal sagas. (In one episode, an elephant’s trunk fastidiously picks the lock on a circus wagon and drags away a strongbox.) Our next entry will spend a little time looking at a neat Genina film from 1919. In the meantime, I’ll sign off by mentioning two other high points.

The pretty Academy IB-Tech print of Under Capricorn (1949) made me like the film quite a bit better than previous viewings. As ever, one high point was La Bergman’s virtuoso soliloquy admitting her guilt. Any other director of the time would have reenacted the crime in a flashback, but, in the shadow of Rope (1948), Hitchcock makes her squeeze out her confession in a ravishing single-take monologue running almost eight minutes.

Its power comes partly from the fact that the framing withholds the facial response of the man who loves her. He’s slowly understanding the depth of her devotion to her husband during penal servitude. “How did you live all those years?” he murmurs. How’d you think? Her glance flicks over him, in both guilt and defiance (above).

Finally, no film gave me more pure pleasure than the restoration of Boetticher’s Ride Lonesome (1959). Sony archivist Grover Crisp explained that the original prints had all been made from the camera negative (!) and so he had no internegatives or fine-grain masters to work from. Nevertheless, this digital version, made in 4K with wetgate scanning, looked superb.

I tend to judge Boetticher westerns by the strength of the villains, meaning that Seven Men from Now (Lee Marvin) and The Tall T (Richard Boone) sit at the top of my heap, but it’s hard to resist the laconic dialogue Burt Kennedy supplied everybody in Ride Lonesome. And the antagonists facing Randolph Scott here–Lee Van Cleef (brief but unforgettable), Pernell Roberts (the good-bad rascal), and sweet-natured dimwit James Coburn (on his way to rangy knife-wielding in The Magnificent Seven)–add up pretty powerfully. Against them stands Scott as vengeance-driven Brigade, an unyielding chunk of sweating mahogany.

Thanks as usual to the Cinema Ritrovato Directors: Cecilia Cenciarelli, Gian Luca Farinelli, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Mariann Lewinsky, and their colleagues. Special thanks to Guy Borlée, the Festival Coordinator. Thanks also to Dave Kehr, Grover Crisp, Mike Pogorzelski, and Geoffrey O’Brien for talk about many of the classics on display.

The entire Ritrovato ’19 catalogue, with full credits and essays, is online here. There are also videos of many events, including master classes with Francis Ford Coppola and Jane Campion.

Quick Millions was remembered several years after its release for “the rapid rhythm of its continuity.” See Janet Graves, “Joining Sight and Sound,” The New York Times (29 November 1936), X4.

John Bailey’s introduction to Under Capricorn included a revealing short explaining the Technicolor dye-transfer process. For further information there’s the remarkable George Eastman House Technicolor research site and of course James Layton and David Pierce’s superb book The Dawn of Technicolor.

Kristin discusses Kiarostami’s landscape techniques in a Criterion Channel Observations entry. In American Dharma, discussed by David here, Errol Morris reveals that Twelve O’Clock High was an inspiration for Steve Bannon’s political career.

The Ritrovato program notes credit Fréhal as the working-class singer in Faubourg Monmartre, but Kelley Conway’s Chanteuse in the City: The Realist Singer in French Film (linked above) identifies her as Odette Barencey, a lesser-known chanteuse of the period who resembled Fréhal.

Opening shot of Ride Lonesome (1959).

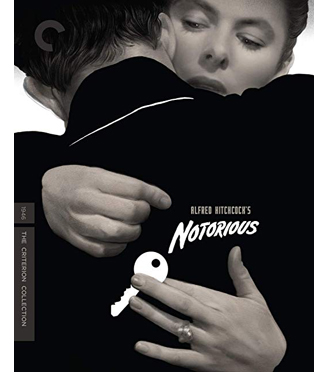

NOTORIOUSly yours, from Criterion

DB here:

Notorious was the subject of the first piece of criticism I published. The venue was Film Heritage, one of those little cinephile magazines that flourished, if that’s the word, in the 1960s. My appreciative essay came out in 1969, as I was finishing my senior year in college.

I haven’t dared to look back at it. Actually, I’m not sure I have a copy. The soft-focus imagery of memory tells me that some things that would preoccupy me in the future–interest in narrative structure, style, point-of-view, the spectator’s engagement with mystery and suspense–are there, though in ploddingly naive shape.

Since those days Hitchcock has always been with me. He’s been the subject of articles and blogs and many, many classroom sessions. Now, thanks to the Criterion collection, I’ve had a chance to revisit Notorious.

The new Blu-ray edition includes a dazzling array of extras. Many were available on the now out-of-print 2001 Criterion DVD: two audio commentaries featuring Rudy Behlmer and Marion Keane, the Lux Radio Theatre adaptation starring Joseph Cotten, and newsreel footage of Hitchcock and Bergman. Added to that earlier material are an interview with Donald Spoto, a video essay on technique by John Bailey, a 2009 documentary about the film, a study of the film’s preproduction by Daniel Raim, and a print essay by Angelica Jade Bastien. Since I just got my copy and wanted to tell you about it, I haven’t had time to plunge into all of this, but the samples I’ve checked are exhilarating.

The new Blu-ray edition includes a dazzling array of extras. Many were available on the now out-of-print 2001 Criterion DVD: two audio commentaries featuring Rudy Behlmer and Marion Keane, the Lux Radio Theatre adaptation starring Joseph Cotten, and newsreel footage of Hitchcock and Bergman. Added to that earlier material are an interview with Donald Spoto, a video essay on technique by John Bailey, a 2009 documentary about the film, a study of the film’s preproduction by Daniel Raim, and a print essay by Angelica Jade Bastien. Since I just got my copy and wanted to tell you about it, I haven’t had time to plunge into all of this, but the samples I’ve checked are exhilarating.

Hitchcock is the most teachable of classic directors. His strategies are just obvious enough for beginners to notice them, but they always open up new directions for more experienced viewers.

I reconfirmed all this when I decided to devote a chapter of Reinventing Hollywood to Hitchcock and Welles. These two masters decisively influenced the 1940s, the period I was considering. But they were in turn influenced by the crosscurrents in their filmmaking community. And they came to epitomize, for me, the artistic richness of what Hollywood could do in this golden age.

In addition, I tried to make the case that they carried storytelling strategies typical of the period into later eras. I declared, in a burst of geek recklessness:

Vertigo constitutes a thoroughgoing compilation/revision of 1940s subjective devices. The obsessive optical POV shots of Scottie trailing Madeleine give way to a dream tricked out with pulsating color, abstract rear projetion, stark geometric patterns, and animated flowers. . . . Along with all the other echoes–portraits, therapy for a traumatized man, voice-over confession, point-of-view switches, the hint of a reincarnated or time-traveling woman–the powerful probes of subjectivity make Vertigo, though released in 1958, one of the most typical forties movies.

But then so is Notorious, a film I had little to say about in the book. So I’m glad that Criterion’s invitation to contribute a 30-minute short on this new release led me back to a film I’ve loved for over fifty years.

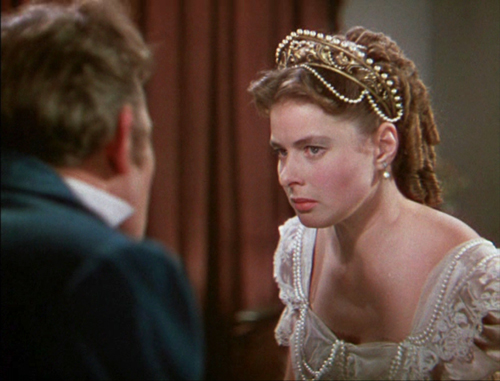

Darned sophisticated, or dead

My supplement concentrates on the climax in Alicia’s bedroom and on the staircase of Sebastian’s mansion. Spiraling out from that sequence, I try to show how it’s the culmination of many storytelling strategies, from point-of-view editing to long takes. I also trace out something I didn’t fully realize until I researched the film’s reception: It was considered very sexy.

For one thing, Ingrid Bergman was associated with innocents, and her playing a promiscuous party girl (“notorious”) was a bit of spice. For another, Hitchcock’s earlier films, though they always had erotic overtones, didn’t really center on a passionate romance. His heroines didn’t convey much smoldering passion, despite all his prattle about glacial blondes thawing out fast. His darkly handsome protagonists (Maxim in Rebecca, Johnnie in Suspicion, Uncle Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt) are more steely than steamy. As for Joel McCrae in Foreign Correspondent and Bob Cummings in Saboteur, they seem virtual Boy Scouts. Only Spellbound, which introduces a psychoanalyst to ecstasy in the rangy form of Gregory Peck, seems a first stab at the sexual complications of Notorious. And the analyst is played, of course, by Bergman, radiant as soon as she takes off her glasses.

The 1940s had a well-established convention that a handsome friend of the family could rescue a wife from the predations of her husband (Gaslight, Sleep My Love) or other tormentor (Shadow of a Doubt). Film scholar Diane Waldman called this figure the helper male. In the second half of Notorious Devlin plays this role. The basic situation–a man stealing another man’s lawfully wedded wife–is pretty edgy in itself, especially since Sebastian is far more frankly in love with Alicia than Devlin is. I try to show that Hitchcock wrings new emotion from the convention by making the husband, trapped between his Nazi gang and his ruthless mother, sympathetic. Meanwhile, the helper male comes off unusually cruel, needling Alicia about the carnal bargain he plunged her into.

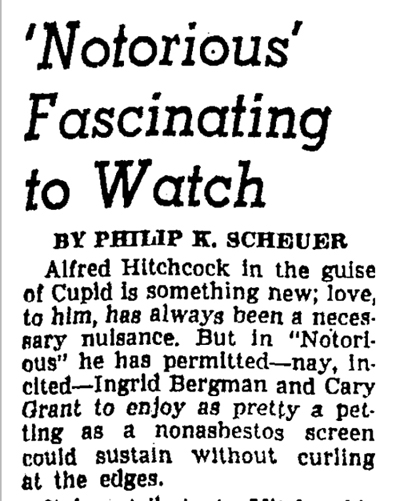

And then there’s all that snogging. The romance in Notorious is one long tease–between the characters, and between the screen and the viewer. The Los Angeles Times critic made it the basis of his lead:

Devlin and Alicia are all over each other, notably in the famous scene in her apartment. (Have they done The Deed? Obviously yes.) Their tight embrace, their constant pecking and nibbling and nuzzling as they float across the room, provoked a lot of notice. In the supplement I quote Dorothy Kilgallen, whom my oldest readers will remember from “What’s My Line?” on TV. She wrote this in Modern Screen:

So it makes a certain amount of sense for a power company to assume that incandescent stars can sell electricity, as below. In Toledo, too.

For this and other reasons, I’m happy to have a chance to revisit one of my very favorite Hitchcock films. I bet that you’ll enjoy seeing this stunning copy and immersing yourself in all the bonuses. Hitch is endlessly fascinating, and he’s one of the main reasons we love movies.

Thanks to Curtis Tsui, who produced the disc, as well as Erik Gunneson and James Runde here at UW–Madison, and all the New York postproduction team. Thanks as well to Peter Becker and Kim Hendrickson for all they do to keep Criterion at the top of its game.

Greg Ruth, designer of cover art for Criterion, explains his creative process on their site. More details on the release, with clip, are here.

The Los Angeles Times review comes from the issue of 23 August 1946, p. A7. The Kilgallen Modern Screen piece is available via Lantern, here. If you youngsters didn’t get her reference to Helen Hokinson, go here.

For another in-depth analysis of a single sequence, see Cristina Álvarez López & Adrian Martin’s Filmkrant video essay, “Place and Space in a Scene from Notorious.” They showed me things I had never noticed–more proof of the richness of Hitchcock World.

Cary Grant’s image was used to sell oil a few years before, as illustrated in this entry.

P.S. 21 January 2019: For more on the steamy side of Notorious, there’s “The Clinch That Filled 1,200 Seats,” at the redoubtable Greenbriar Picture Shows. Thanks to John McElwee for bringing it to my notice!

Better Theatres (24 August 1946).

Is there a blog in this class? 2018

24 Frames (2017)

Kristin here:

David and I started this blog way back in 2006 largely as a way to offer teachers who use Film Art: An Introduction supplementary material that might tie in with the book. It immediately became something more informal, as we wrote about topics that interested us and events in our lives, like campus visits by filmmakers and festivals we attended. Few of the entries actually relate explicitly to the content of Film Art, and yet many of them might be relevant.

Every year shortly before the autumn semester begins, we offer this list of suggestions of posts that might be useful in classes, either as assignments or recommendations. Those who aren’t teaching or being taught might find the following round-up a handy way of catching up with entries they might have missed. After all, we are pushing 900 posts, and despite our excellent search engine and many categories of tags, a little guidance through this flood of texts and images might be useful to some.

This list starts after last August’s post. For past lists, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017.

This year for the first time I’ll be including the video pieces that our collaborator Jeff Smith and we have since November, 2016, been posting monthly on the Criterion Channel of the streaming service FilmStruck. In them we briefly discuss (most run around 10 to 14 minutes) topics relating to movies streaming on FilmStruck. For teachers whose school subscribes to FilmStruck there is the possibility of showing them in classes. The series of videos is also called “Observations on Film Art,” because it was in a way conceived as an extension of this blog, though it’s more closely keyed to topics discussed in Film Art. As of now there are 21 videos available, with more in the can. I won’t put in a link for each individual entry, but you can find a complete index of our videos here. Since I didn’t include our early entries in my 2017 round-up, I’ll do so here.

As always, I’ll go chapter by chapter, with a few items at the end that don’t fit in but might be useful.

[July 21, 2019: In late November, 2018, the Filmstruck streaming service ceased operation. On April 8, 2019, it was replaced by The Criterion Channel, the streaming service of The Criterion Collection. All the Filmstruck videos listed below appear, with the same titles and numbers, in the “Observations on Film Art” series on the new service. Teachers are welcome to stream these for their classes with a subscription.]

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

David writes on the persistence of classical Hollywood storytelling in contemporary films: “Everything new is old again: Stories from 2017.”

In FilmStruck #5, I look at the effects of using a child as one of the main point-of-view figures in Victor Erice’s masterpiece: “The Spirit of the Beehive–A Child’s Point of View”

In FilmStruck #13, I deal with “Flashbacks in The Phantom Carriage.”

FilmStruck #14 features David discussing classical narrative structure in “Girl Shy—Harold Lloyd Meets Classical Hollywood.” His blog entry, “The Boy’s life: Harold Lloyd’s GIRL SHY on the Criterion Channel” elaborates on Lloyd’s move from simple slapstick into classical filmmaking in his early features. (It could also be used in relation to acting in Chapter 4.)

In FilmStruck #17, David examines “Narrative Symmetry in Chungking Express.”

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-Scene

In choosing films for our FilmStruck videos, we try occasionally to highlight little-known titles that deserve a lot more attention. In FilmStruck #16 I looks at the unusual lighting in Raymond Bernard’s early 1930s classic: “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses.”

FilmStruck #3: Abbas Kiarostami is noted for his expressive use of landscapes. I examine that aspect of his style in Where Is My Friend’s Home? and The Taste of Cherry: “Abbas Kiarostami–The Character of Landscape, the Landscape of Character.”

Teachers often request more on acting. Performances are difficult to analyze, but being able to use multiple clips helps lot. David has taken advantage of that three times so far.

In FilmStruck #4, “The Restrain of L’avventura,” he looks at how staging helps create the enigmatic quality of Antonionni’s narrative.

In FilmStruck #7, I deal with Renoir’s complex orchestration of action in depth: “Staging in The Rules of the Game.”

FilmStruck #10, features David on details of acting: “Performance in Brute Force.”

In Filmstruck #18, David analyses performance style: “Staging and Performance in Ivan the Terrible Part II.” He expands on it in “Eisenstein makes a scene: IVAN THE TERRIBLE Part 2 on the Criterion Channel.”

FilmStruck #19, by me, examines the narrative functions of “Color Motifs in Black Narcissus.”

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

A basic function of cinematography is framing–choosing a camera setup, deciding what to include or exclude from the shot. David discusses Lubitsch’s cunning play with framing in Rosita and Lady Windermere’s Fan in “Lubitsch redoes Lubitsch.”

In FilmStruck #6, Jeff shows how cinematography creates parallelism: “Camera Movement in Three Colors: Red.”

In FilmStruck 21 Jeff looks at a very different use of the camera: “The Restless Cinematography of Breaking the Waves.”

Chapter 6 The Relation of Shot to Shot: Editing

David on multiple-camera shooting and its effects on editing in an early Frank Capra sound film: “The quietest talkie: THE DONOVAN AFFAIR (1929).”

In Filmstruck #2, David discusses Kurosawa’s fast cutting in “Quicker Than the Eye—Editing in Sanjuro Sugata.”

In FilmStruck #20 Jeff lays out “Continuity Editing in The Devil and Daniel Webster.” He follows up on it with a blog entry: “FilmStruck goes to THE DEVIL”,

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

In 2017, we were lucky enough to see the premiere of the restored print of Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) at the Venice International Film Festival in 2017. My entry “Lubitsch and Pickford, finally together again,” gives some sense of the complexities of reconstructing the original musical score for the film.

In FilmStruck #1, Jeff Smith discusses “Musical Motifs in Foreign Correspondent.”

Filmstruck #8 features Jeff explaining Chabrol’s use of “Offscreen Sound in La cérémonie.”

In FilmStruck #11, I discuss Fritz Lang’s extraordinary facility with the new sound technology in his first talkie: “Mastering a New Medium—Sound in M.”

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

David analyzes narrative patterning and lighting Casablanca in “You must remember this, even though I sort of didn’t.”

In FilmStruck #10, Jeff examines how Fassbender’s style helps accentuate social divisions: “The Stripped-Down Style of Ali Fear Eats the Soul.”

Chapter 9 Film Genres

David tackles a subset of the crime genre in “One last big job: How heist movies tell their stories.”

He also discusses a subset of the thriller genre in “The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt.”

FilmStruck #9 has David exploring Chaplin’s departures from the conventions of his familiar comedies of the past to get serious in Monsieur Verdoux: “Chaplin’s Comedy of Murders.” He followed up with a blog entry, “MONSIEUR VERDOUX: Lethal Lothario.”

In Filmstruck entry #15, “Genre Play in The Player,” Jeff discusses the conventions of two genres, the crime thriller and movies about Hollywood filmmaking, in Robert Altman’s film. He elaborates on his analysis in his blog entry, “Who got played?”

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

I analyse Bill Morrison’s documentary on the history of Dawson City, where a cache of lost silent films was discovered, in “Bill Morrison’s lyrical tale of loss, destruction and (sometimes) recovery.”

David takes a close look at Abbas Kiarostami’s experimental final film in “Barely moving pictures: Kiarostami’s 24 FRAMES.”

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

We blogged from the Venice International Film Festival last year, offering analyses of some of the films we saw. These are much shorter than the ones in Chapter 11, but they show how even a brief report (of the type students might be assigned to write) can go beyond description and quick evaluation.

The first entry deals with the world premieres of The Shape of Water and Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri and is based on single viewings. The second was based on two viewings of Argentine director Lucretia Martel’s marvelous and complex Zama. The third covers films by three major Asian directors: Kore-eda Hirokazu, John Woo, and Takeshi Kitano.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

My usual list of the ten best films of 90 years ago deals with great classics from 1927, some famous, some not so much so.

David discusses stylistic conventions and inventions in some rare 1910s American films in “Something familiar, something peculiar, something for everyone: The 1910s tonight.”

I give a rundown on the restoration of a silent Hollywood classic long available only in a truncated version: The Lost World (1925).

In teaching modern Hollywood and especially superhero blockbusters like Thor Ragnarok, my “Taika Waititi: The very model of a modern movie-maker” might prove useful.

Etc.

If you’re planning to show a film by Damien Chazelle in your class, for whatever chapter, David provides a run-down of his career and comments on his feature films in “New colors to sing: Damien Chazelle on films and filmmaking.” This complements entries from last year on La La Land: “How LA LA LAND is made” and “Singin’ in the sun,” a guest post featuring discussion by Kelley Conway, Eric Dienstfrey, and Amanda McQueen.

Our blog is not just of use for Film Art, of course. It contains a lot about film history that could be useful in teaching with our other textbook. In particular, this past year saw the publication of David’s Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Hollywood Storytelling. His entry “REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD: Out of the past” discusses how it was written, and several entries, recent and older, bear on the book’s arguments. See the category “1940s Hollywood.”

Finally, we don’t deal with Virtual Reality artworks in Film Art, but if you include it in your class or are just interested in the subject, our entry “Venice 2017: Sensory Saturday; or what puts the Virtual in VR” might be of interest. It reports on four VR pieces shown at the Venice International Film Festival, the first major film festival to include VR and award prizes.

Monsieur Verdoux (1947)