Archive for the 'Directors: Hitchcock' Category

The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt

Looking is as important in movies as talking is in in plays. Thanks to optical point-of-view shots (POV) and reaction-shot cutting, you can create a powerful drama without words.

Everybody knows this, but sometimes it’s good to be reminded. (I did that here long ago.) Now I have another occasion to explore this terrain. But first: How I spent my summer vacation.

After Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I went to the annual Summer Film College in Antwerp. (Instagram images here.) I’ve missed a couple of sessions (the last entry is from 2015), but this year I returned for another dynamite program. There were three threads. Adrian Martin and Cristina Álvarez López mounted a spirited defense of Brian De Palma’s achievement. Tom Paulus, Ruben Demasure, and Richard Misek gave lectures on Eric Rohmer films. I brought up the rear with four lectures on other topics. As ever, it was a feast of enjoyable cinema and cinema talk, starting at 9:30 AM and running till 11 PM or so. The schedule is here.

After Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I went to the annual Summer Film College in Antwerp. (Instagram images here.) I’ve missed a couple of sessions (the last entry is from 2015), but this year I returned for another dynamite program. There were three threads. Adrian Martin and Cristina Álvarez López mounted a spirited defense of Brian De Palma’s achievement. Tom Paulus, Ruben Demasure, and Richard Misek gave lectures on Eric Rohmer films. I brought up the rear with four lectures on other topics. As ever, it was a feast of enjoyable cinema and cinema talk, starting at 9:30 AM and running till 11 PM or so. The schedule is here.

Because I was fussing with my own lectures, I missed the Rohmer events, unfortunately. I did catch all the De Palma lectures and some of the films. Cristina and Adrian offered powerful analyses of De Palma’s characteristic vision and style. I especially appreciated the chance to watch Carlito’s Way again (script by friend of the blog David Koepp) and to see on the big screen BDP’s last film Passion, which looked fine. I confess to preferring some of his contract movies (Mission: Impossible, The Untouchables, Snake Eyes) to some of his more personal projects, but he takes chances, which is a good thing.

Two of my lectures had ties to my book Reinventing Hollywood. “The Archaeology of Citizen Kane” (should probably have been called “An Archaeology…) pulled together things touched on in blogs, topics discussed at greater length in books, and things I’ve stumbled on more recently. Maybe I can float the newer bits and pieces here some time.

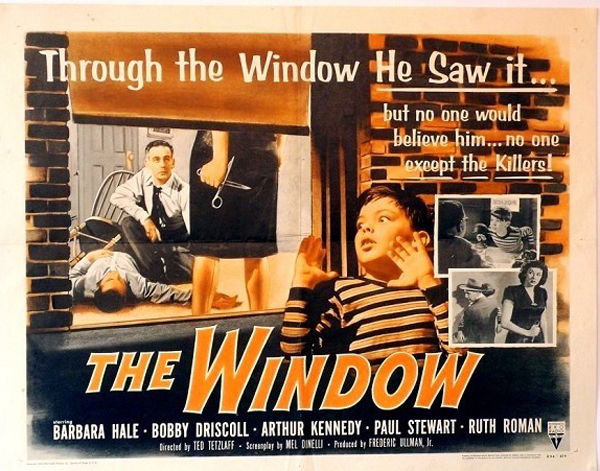

The other lecture took off from my book’s discussion of the emergence of the domestic thriller in the 1940s. We screened The Window (1949), a film that I hadn’t studied closely before. If you can see or resee it before reading on, you might want to do that. But the spoilers don’t come up for a while, and I’ll warn you when they’re impending.

Exploring the how

It is to the thriller that the American cinema owes the best of its inspirations.

Eric Rohmer

One strand of argument in Reinventing Hollywood goes like this.

During the 1930s Hollywood filmmakers mostly concentrated on adapting their storytelling traditions to sync sound and to new genres (the musical, the gangster film). By 1939 or so, those problems were largely solved. As a result, some ambitious filmmakers returned to narrative techniques that were fairly common in the silent era but had become rare in talkies. Those techniques–nonlinear plots, subjectivity, plays with viewpoint and overarching narration–were refined and expanded, thanks to sound technology and quite self-conscious efforts to create more complex viewing experiences.

Wuthering Heights, Our Town, Citizen Kane, How Green Was My Valley, Lydia, The Magnificent Ambersons, Laura, Mildred Pierce, I Remember Mama, Unfaithfully Yours, A Letter to Three Wives, and a host of B pictures and melodramas and war films and mystery stories and even musicals (Lady in the Dark) and romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan)–all these and more attest to new efforts to tell stories in oblique, arresting ways. They seem to have taken to heart a remark from Darryl F. Zanuck (right). It forms the epigraph of my book:

Wuthering Heights, Our Town, Citizen Kane, How Green Was My Valley, Lydia, The Magnificent Ambersons, Laura, Mildred Pierce, I Remember Mama, Unfaithfully Yours, A Letter to Three Wives, and a host of B pictures and melodramas and war films and mystery stories and even musicals (Lady in the Dark) and romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan)–all these and more attest to new efforts to tell stories in oblique, arresting ways. They seem to have taken to heart a remark from Darryl F. Zanuck (right). It forms the epigraph of my book:

It is not enough just to tell an interesting story. Half the battle depends on how you tell the story. As a matter of fact, the most important half depends on how you tell the story.

Put it another way. Very approximately, we might say that most 1930s pictures are “theatrical”–not just in being derived from plays (though many were) but in telling their stories through objective, external behavior. We infer characters’ inner lives from the way they talk and move, the way they respond to each other in situ. And the plot thrusts itself ever forward, chronologically, toward the big scenes that will tie together the strands of developing action. In this respect, even the stories derived from novels depend on this external, linear presentation.

In contrast, a lot of 1940s films are “novelistic” in shaping their plots through layers of time, in summoning a character or an omniscient voice to narrate the action, and in plunging us into the mental life of the characters through dreams, hallucinations, and bits of memory, both visual and auditory. We get to know characters a bit more subjectively, as they report their feelings in voice-over, or we grasp action through what they see and hear.

The distinction isn’t absolute. Some of these “novelistic” techniques were being applied on the stage as well, as a minor tradition from the 1910s on. I just want to signal, in a sketchy way, Hollywood’s 1940s turn toward more complex forms of subjectivity, time, and perspective–the sort of thing that became central for novelists in the wake of Henry James and Joseph Conrad.

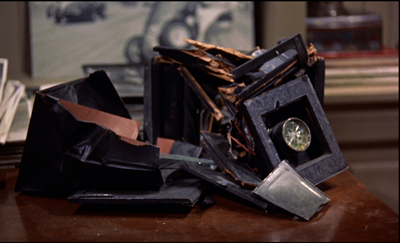

In tandem with this greater formal ambition comes what we might call “thickening” of the film’s texture. Partly it’s seen in a fresh opennness to chiaroscuro lighting for a greater range of genres, to a willingness to pick unusual angles (high or low) and accentuate cuts. The thickening comes in characterization too, when we get tangled motives and enigmatic protagonists (not just Kane and Lydia but the triangles of Daisy Kenyon or The Woman on the Beach). There’s also a new sensitivity to audiovisual motifs that seem to decorate the core action–the stripey blinds of film noir but also symbolic objects (the snowstorm paperweights in Kane and Kitty Foyle, the locket in The Locket, the looming portraits and mirrors that seem to be everywhere). Add in greater weight put on density and details of staging, enhanced by recurring compositions, as I discuss in an earlier entry.

One genre that comes into its own at the period relies heavily on the new awareness of Zanuck’s how. That’s the psychological thriller.

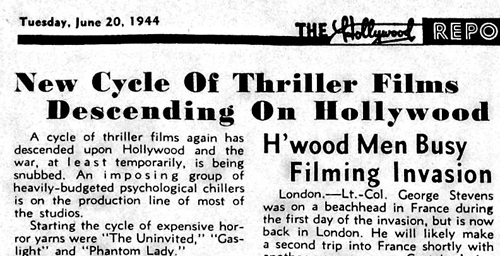

I’ve written at length about this characteristic 1940s genre (see the codicil below), so I’ll just recap. The 1930s and 1940s saw big changes in mystery literature generally. The white-gloved sleuth in the Holmes/Poirot/Wimsey vein met a rival in the hard-boiled detective. Just as important was the growing popularity of psychological thrillers set in familiar surroundings. The sources were many, going back to Wilkie Collins’ “sensation fiction” and leading to the influential works by Patrick Hamilton (Rope, Hangover Square, Gaslight). In the same years, the domestic thriller came to concentrate on women in peril, a format popularized by Mary Roberts Rinehart and brought to a pitch by Daphne du Maurier. The impulse was continued by many ingenious women novelists, notably Elizabeth Sanxay Holding and Margaret Millar. The domestic thriller was a mainstay of popular fiction, radio, and the theatre of the period, so naturally it made its way into cinema.

Literary thrillers play ingenious games with the conventions of the post-Jamesian novel. We get geometrically arrayed viewpoints (Vera Caspary’s Laura, Chris Massie’s The Green Circle) and fluid time shifts (John Franklin Bardin’s Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly). There are jolting switches of first-person narration (Kenneth Fearing’s The Big Clock), sometimes accessing dead characters (Fearing’s Dagger of the Mind). There are swirling plunges into what might be purely imaginary realms (Joel Townsley Rogers’ The Red Right Hand).

Ben Hecht remarked that mystery novels “are ingenious because they have to be.” Formal play, even trickery, is central to the genre, and misleading the reader is as important in a thriller as in a more orthodox detective story. No wonder that the genre suited filmmakers’ new eagerness to experiment with storytelling strategies.

Vision, danger, and the unreliable eyewitness

What does a thriller need in order to be thrilling? For one thing, central characters must be in mortal jeopardy. The protagonist is likely to be a target of impending violence. One variant is to build a plot around an attack on one victim, but to continue by centering on an investigator or witness to the first crime who becomes the new target. In Ministry of Fear, our hero brushes up against an espionage ring. While he pursues clues, the spies try to eliminate him.

Accordingly, the cinematic narration intensifies the situation of the character in peril. A tight restriction of knowledge to one character, as in Suspicion, builds curiosity and suspense as we wait for the unseen forces’ next move. Alternatively, a “moving-spotlight” narration can build the same qualities. In Notorious, we’re aware before Alicia is that Sebastian and his mother are poisoning her. Even “neutral” passages can mask story information through judiciously skipping over key events, as happens in the opening of Mildred Pierce.

Using point-of-view techniques to present the threats to the protagonist brought forth a distinctive 1940s cycle of eyewitness plots. Here the initial crime is seen, more or less, by a third party, and this act is displayed through optical POV devices. There typically follows a drama of doubt, as the eyewitness tries to convince people in authority that the crime has been committed. Part of the doubt arises from an interesting convention: the eyewitness is usually characterized as unreliable in some way. Sooner or later the perpetrator of the crime learns of the eyewitness and targets him or her for elimination. The cat-and-mouse game that ensues is usually resolved by the rescue of the witness.

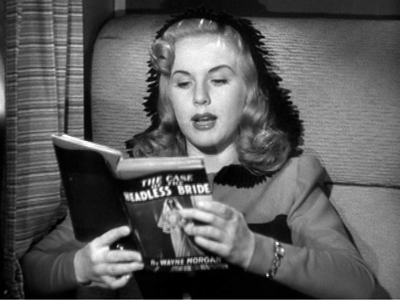

The earliest 1940s plot of this type I’ve found isn’t a film, but rather Cornell Woolrich’s story “It Had to Be Murder,” published in Dime Detective in 1942. (It later became Hitchcock’s Rear Window. But see the codicil for earlier Woolrich examples.) The earliest film example from the period may be Universal’s Lady on a Train (1945), from an unpublished story by Leslie Charteris.

The opening signals that this will be a murder-she-said comedy. Nicki Collins is traveling from San Francisco to New York and reading aloud, in a state of tension, The Case of the Headless Bride (a dig at the Perry Mason series?). As the train pauses in its approach to Grand Central she comes to a climactic passage: “Somehow she forced her eyes to turn to the window. What horror she expected to see…” Nicki looks up from her book to see a quarrel in an apartment. One man lowers the curtain and bludgeons the other, and as Nicki reacts in surprise, the train moves on.

The over-the-shoulder framings don’t exactly mimic Nicki’s optical viewpoint, but they do attach us to her act of looking. Reverse-angle cuts show us her reactions. Her recital of the novel’s prose establishes her suggestibility and an overactive imagination. These qualities fulfill, in a screwball-comedy register, the convention of the witness’s potential unreliability. We know her perception is accurate, but her scatterbrained chatter justifies the skepticism of everybody she approaches. As the plot unrolls, her efforts to solve the mystery make her the killer’s new target.

More serious in tone was Lucille Fletcher’s radio drama, “The Thing in the Window” from 1946. In the same year, Cornell Woolrich rang a new change on the “Rear Window” theme with the short story “The Boy Who Cried Wolf,” and Twentieth Century–Fox released Shock. In this thriller an anxious wife waits in a hotel room for her husband, who has been away at war for years. Elaine Jordan’s instability is indicated by a dream in which she stumbles down a long corridor toward an enormous door that she struggles to open.

Awakening, Elaine nervously goes to the window in time to see a quarrel in an adjacent room. She watches as a man kills his wife.

Now she’s pushed over the edge. As bad luck would have it, the killer is a psychiatrist. When he learns that Elaine saw him, he takes charge of her case. He spirits her away to his private sanitarium, where he’ll keep her imprisoned with the help of his nurse-paramour.

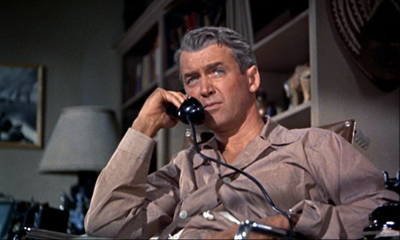

I was surprised to learn of this eyewitness-thriller cycle because the prototype of this plot was for me, and maybe you too, was a later film, Rear Window (1954). Again, the protagonist believes he’s seen a crime, though here it’s the circumstances around it rather than the act itself. Accordingly a great deal of the plot is taken up with the drama of doubt, as the chairbound Jeff investigates as best he can. He spies on his neighbor and recruits the help of his girlfriend Lisa and his police detective pal.

Hitchcock, coming from the spatial-confinement dramas Rope and Dial M for Murder, followed the Woolrich story in making his protagonist unable to leave his apartment. Following Woolrich’s astonishingly abstract descriptions of the protagonist’s views, Hitchcock made optical POV the basis of Jeff”s inquiry. By turning Woolrich’s protagonist into a photojournalist, he enhanced the premise through use of Jeff’s telephoto lenses.

Woolrich and Hitchcock’s reliance on spatial confinement worked to the advantage of the unreliable-witness convention. How much could you really see from that window? Jeff can’t check on the background information his cop friend reports. Besides, Jeff is bored and susceptible to conclusion-jumping. “Right now I’d welcome trouble.”

Hitchcock, who kept an eye on his competitors, doubtless was aware of The Window (1949), an earlier entry in the cycle. Derived from Woolrich’s “Boy Who Cried Wolf,” this RKO film has some intriguing things to teach us about the mechanics of thrillers and about the 1940s look and feel.

Spoilers follow.

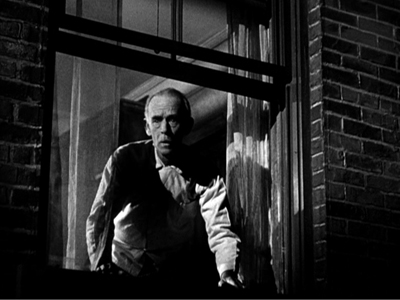

At the window, and outside it

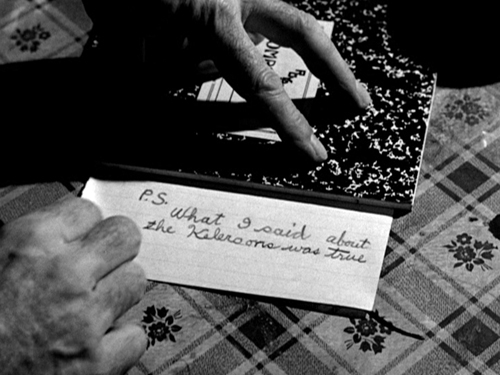

On a hot summer night, the boy Tommy Woodry is sleeping on a tenement fire escape one floor above his family’s apartment. He awakes to see Mr. and Mrs. Kellerson murder a sailor they have robbbed. Next morning Tommy tries to report the crime to his parents and then the police, but no one will believe him because he’s long been telling fantastic tales. A family emergency leaves him alone in the apartment, and the Kellersons lure him out. After nearly being killed by them, he flees to a tumbledown building nearby. There he evades Mr. Kellerson, who falls to his death. With Tommy’s parents and the police now believing him, he’s rescued from his perch on a precarious rafter.

Woolrich’s original story confines us strictly to Tommy’s range of knowledge, but in the interest of suspense screenwriter Mel Dinelli uses moving-spotlight narration. When Tommy flees the fire escape, for instance, we follow the efforts of the Kellersons to rid themselves of the body. This becomes important to show how difficult it will be for Tommy to prove his story. There’s also a moment during their coverup when the camera lingers on Mrs. Kellerson, both in profile and from the back, as if she were hesitating about going along with the plan.

This shot prepares for the climax, when as her husband is about to shove Tommy off the fire escape, she blocks his gesture and allows Tommy to escape across the rooftops.

Likewise, Woolrich’s story simply reports that the young hero waited at the police station for the result of Detective Ross’s visit to the Kellersons. The film’s narration attaches us to Ross and creates a scene of considerable suspense when we wonder if Ross will discover any clues to the murder. And whereas in the story Tommy must worry about how Kellerson will get to him, through crosscutting between Kellerson in the kitchen and Tommy locked in his room we know everything that’s happening. This permits a wry passage of suspense in which Kellerson toys with Tommy by letting him think he’s retrieving the door’s key.

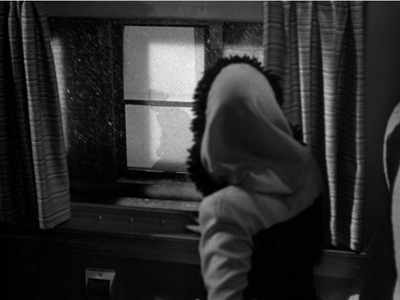

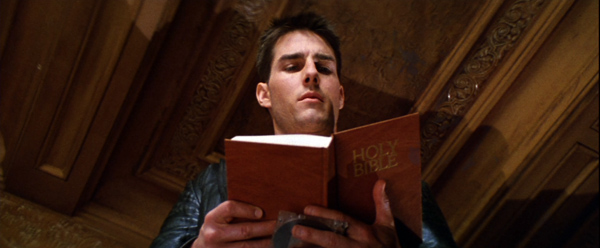

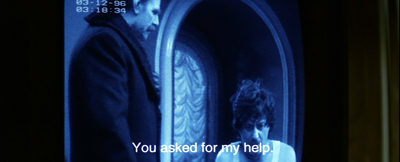

In contrast to the moving-spotlight approach, though, crucial passages are rendered with a limited range of knowledge. Optically subjective shots come to the fore here, as when Tommy witnesses the murder.

It seems likely that Hitchcock’s early American films heightened filmmakers’ awareness of subjective optical techniques, and here director Ted Tetzlaff puts them to good use. The script I’ve seen for The Window doesn’t indicate such pure POV shots, instead opting for something like what we get in Lady on a Train. “CAMERA is ON the pillow back of Tommy, so that we see his head in the f.g and the window in the b.g.” There is a shot matching these directions, but it’s surrounded by the straight POV imagery framed by Tommy’s frightened stare.

The decision by Tetzlaff and his colleagues to rely on optical POV is confirmed when, during Ross’s visit, he spots a stain on the floor.

Is this a bloodstain that will put Ross on the scent? Crucially, we haven’t seen the lethal scissors leave a trace. Kellerson explains the stain as coming from a leak in the ceiling. Obediently Ross looks up and, to prolong the suspense, so does Mrs. Kellerson, apparently as apprehensive as we are. That extra shot of her nicely delays the reveal: there is a leak above them.

In tune with the tendency to thicken the narrative texture, this POV dynamic reappears at other moments. Tommy sees his parents leave, and the reverse angle reveals that the Kellersons see them too, and so they know that Tommy is now unguarded.

At the climax in the abandoned tenement, Tommy spots his father and the policeman outside. He shouts to get their attention, but they can’t hear.

But Kellerman does hear Tommy and uses the sound to stalk him.

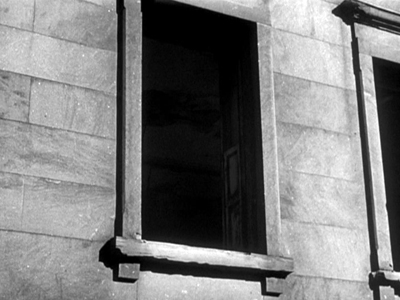

1940s stylistic thickening includes the use of audiovisual motifs that impose a distinctive look on the film. So a movie called The Window begins, after a couple of establishing shots of Manhattan street life, with a shot of a window.

This one has no special importance in the plot, but it announces the image that will recur throughout the movie. By shooting ordinary scenes through window frames, Tetzlaff reminds us that the locals live partly through those windows and the fire escapes outside.

Naturally enough, Kellerson plans to kill Tommy by having him tumble from the fire escape outside the window.

The film’s key image reappears at the end, when after Kellerson’s fall a new crop of witnesses take to their windows.

Another motif is the vertical link between the two apartments, given in looming shots of the staircase (a common piece of iconography in 1940s cinema) and in cutting that links Tommy’s bedroom to the Kellersons above him. He listens to their footsteps through his ceiling.

The next layer up, the rooftop, serves as a route from the families’ building to the abandoned one, and eventually the chase will play out there.

Vertical space more generally is important at the very start of the film. During Tommy’s mock ambush of his playmates, we look down over his shoulder. At the very end, Kellerson has trapped Tommy on the broken rafter.

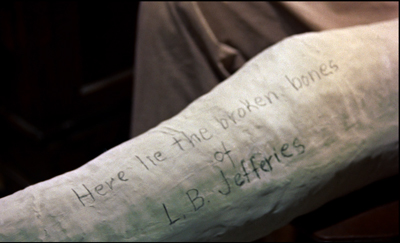

The rooftop and rafter become part of another pattern, the circular one that rules the plot. Woolrich’s original story doesn’t feature the opening we have, showing Tommy in the abandoned tenement pretending to snipe at the other boys. Nor does the shooting script I’ve seen. Starting the film there establishes the locale of the climactic chase, while creating parallel scenes of Tommy hiding. We even get to see the broken rafter early on, when Tommy is prowling around his playmates.

The result is a pleasing, somewhat shocking symmetry of action: Tommy pretends to kill somebody at the start, and he succeeds in killing someone at the end.

The film offers a cluster of images that are recycled with variations, amplifying the basic story action through patterns of space and visual design.

The thickening of texture isn’t only pictorial. The drama of doubt involves a questioning of parental wisdom. Tommy’s mother actually endangers her boy by asking him to apologize to Mrs. Kellerson. More central is a testing of the father’s faith in his son. Tommy’s dilemma is to tell the truth even though he’ll be disbelieved by all the figures of social authority. The father’s increasingly desperate efforts to change Tommy’s story are revealed in Arthur Kennedy’s delicate portrayal of exasperation–at first gentle, then severe and nearly abusive.

Ed Woodry fails in his duty. The adults aren’t capable of protecting the child. A conventional plot would’ve had Ed redeem himself by rescuing his son, but the film we have leaves the killing to Tommy. It’s a grim condemnation of the people supposed to protect him.

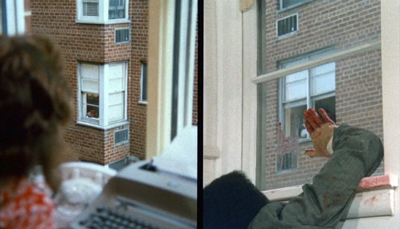

Another convention, it seems, of the eyewitness film involves punishing the peeper. In Lady on a Train, Nicki has to brave a spooky house and risk death. Elaine of Shock suffers in the mental institution, and in Rear Window Jeff eventually falls from the very window that was his interface with the courtyard. Tommy, who acknowledges his inclination to tell whoppers, is subjected to a final burst of peril. After Kellerson has plunged to his death, Tommy is left in mid-air and he must jump to the firemen’s waiting net. In the epilogue, he announces that he’s learned his lesson, not least because of several brushes with death.

Revising the rules

The 1940s eyewitness cycle laid out some options for future thrillers. Rear Window, as we’ve seen, crystallizes the plot premise in rather pure form, and interestingly that was copied almost immediately in the Hong Kong film Rear Window (Hou chuang, 1955). Some passages are straight mimicry, albeit on a much smaller budget.

Thereafter, the eyewitness premise resurfaced, notably in Sisters (1973, with split screen) and with another child protagonist in The Client (1994).

In recent decades filmmakers have revised the premise in ways typical of post-Pulp-Fiction Hollywood. Vantage Point (2008) multiplies the eyewitnesses and uses replays to conceal and eventually reveal information. The Girl on the Train (2016), streamlining the multiple-viewpoint structure of the novel, alternates plotlines centered on three women. The novel and the film recast the eyewitness schema by making the eyewitness unable to recall exactly what she saw, thanks to an alcoholic blackout. (It’s a cousin to our old 1940s friend amnesia). This uncertainty raises the possibility that the eyewitness is actually the killer.

With its goal-directed protagonist and trim four-part plot structure, The Window is a completely classical film. As often happens, a forgivably flawed character gains our sympathy by being treated unfairly but triumphs in the end. And in the film’s integration of dramatic and pictorial elements, its alternation of subjectivity and wide-ranging narration for the sake of suspense, it nicely illustrates some ways in which 1940s filmmakers recast classical traditions for the thriller format and opened up new storytelling options.

Woolrich’s “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” is available under the title “Fire Escape” in Dead Man Blues (Lippincott, 1948), published under the pseudonym William Irish. Woolrich, ever the formalist, initially gave “It Had to Be Murder”/”Rear Window” my dream title: “Murder from a Fixed Viewpoint.” An earlier Woolrich story, “Wake Up with Death” from 1937, flips the viewpoint: A man emerges from drunken sleep to discover a murdered woman at his bedside and gets a call from someone who claims to have watched him commit the crime. Then there’s “Silhouette” from 1939, in which a couple witness a strangling projected on a window shade. See Francis M. Nevins, Jr.’s exhaustive Cornell Woolrich: First You Dream, Then You Die (Mysterious Press, 1988), 158, 186, 245. There are doubtless many earlier eyewitness thrillers, which the indefatigable Mike Grost could tabulate.

The screenplay by Mel Dinelli that I consulted, with help from Kristin, is a rather detailed shooting script dated 23 October 1947. It is housed in the Dore Schary collection at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Dinelli benefited from the thriller boom in his screenplays for The Spiral Staircase, The Reckless Moment, House by the River, Cause for Alarm!, and Beware, My Lovely.

There are plenty of discussions of thrillers on this site; try here and here. Apart from the chapter in Reinventing Hollywood, you can find overviews here and here. See also the category 1940s Hollywood. I discuss the sort of plot fragmentation characteristic of some current Hollywood cinema, built on 1940s premises, in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

For more images from my summer movie vacation, visit our Instagram page.

P.S. 24 July: Thanks very much to Bart Verbank for correcting my embarrassing name error in Rear Window! Also, if you’re wondering why I didn’t mention the very latest instantiation of the the eyewitness plot, A. J. Finn’s Woman in the Window, it’s because (a) I haven’t read it; and (b) I resist reading a book with a title swiped from a Fritz Lang movie.

DB accepts a fine Kriek from the Antwerp Summer Film College team: David Vanden Bossche, Tom Paulus, Lisa Colpaert, and Bart Versteirt.

Spies face the music: Jeff Smith on FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT

DB here: Here’s another guest contribution from colleague, Film Art collaborator, and pal Jeff Smith. He inaugurates a series of entries tied to our monthly Observations on Film Art videos on FilmStruck.

About a month ago, a new streaming service for film lovers debuted. Its name is FilmStruck and it’s a joint venture of Turner Classic Movies and the Criterion Collection.

As regular readers of the blog already know, David, Kristin, and I have launched a series for FilmStruck. Every month, we’ll be featured in short videos that offer appreciations of particular films and filmmakers. In baseball lingo, I got the leadoff spot. As the first up, I offered an overview of the principal musical motifs in Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent. Below is a supplement to the video that goes into a little more depth regarding the way Alfred Newman’s score for Foreign Correspondent fits into the film’s larger narrative strategies.

Fair warning: there are some spoilers in what follows. Some of you who are FilmStruck subscribers or owners of the Criterion disc may want to watch this Hitchcock classic before proceeding.

Founding a Hollywood dynasty

Alfred Newman.

If you were looking for someone whose work epitomized the qualities of the classical Hollywood score, Alfred Newman would be a pretty good candidate for the job.

Newman’s career in Hollywood began when Tin Pan Alley stalwart, Irving Berlin, recommended him for the 1930 musical, Reaching for the Moon. Having worked for years as a music director on Broadway, Newman planned to stay for only three months. But the lure of the Silver Screen was too strong. Newman spent the next forty years working in Hollywood.

In 1931, Newman became the musical director at United Artists, working mostly for producer Samuel Goldwyn. He also established himself as one of the industry’s leading composers, contributing to nearly ninety films over the course of the 1930s and earning nine Oscar nominations in the process. Newman’s most memorable early scores included such titles as The Prisoner of Zenda, The Hurricane, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and Wuthering Heights. Eventually, he would leave Goldwyn to take over the music department at 20th Century-Fox, a position he held for more than twenty years.

Alfred, however, would be just one of several Newmans who would make the name synonymous with the Hollywood sound. Alfred would establish a film composing dynasty that would come to include his brothers Lionel and Emil; his sons, Thomas and David; and his nephew, Randy.

Overture, hit the lights….

If you asked most film music aficionados for their favorite Alfred Newman scores, I suspect Foreign Correspondent would be pretty low on the list. Most fans of the composer’s work would likely opt for one of the later Fox classics he scored, such as How Green Was My Valley (1941), A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1945), The Captain from Castile (1947), or The Robe (1953). Yet, if you want to get a handle on the basic features of the classical paradigm, Foreign Correspondent’s typicality makes it more useful as an exemplar. Newman’s music neatly illustrates several of the traits commonly associated with the classical Hollywood score’s dramatic functions.

One of these characteristic traits is Newman’s use of leitmotif as an organizational principle. Foreign Correspondent’s score is organized around five in all. The first is a theme for the film’s protagonist, Johnny Jones. The second is a theme for Carol, Johnny’s love interest in the film. As is typical of studio-era scores, both themes are introduced in the film’s Main Title.

Like an overture, the Main Title previews the two most important musical themes in the film. The A theme is upbeat, sprightly, and lightly comic. It captures some of Johnny’s ebullience and masculine charm, and it helps establish the tone of the early scenes, which draw upon the conventions of the newspaper film. The B theme is slower and more lyrical. It features the kind of lush orchestrations for strings that became a hallmark of Newman’s style.

Each theme roughly correlates with the dual plot structure common to classical Hollywood narratives. The A theme previews the main plotline focused on Johnny’s efforts as an investigative reporter. The B theme previews the story’s secondary plotline: the budding romance between Johnny and Carol.

Both themes recur throughout the remainder of the movie. In fact, Johnny’s theme returns even before the opening credits have ended, appearing underneath a title card valorizing the power of the press. In contrast to the lively, spunky version heard earlier, Newman gives it a maestoso treatment, slowing the tempo and orchestrating it for brass. In this instance, Newman’s arrangement of Johnny’s theme is attuned less to the brashness of his character and more to the social role that newspaper reporters play as a source of information to the world.

Up until this point, the music simply primes us for what is to come. Johnny’s theme returns about two minutes later when he is first introduced.

The reprise of his theme makes explicit the Main Title’s tacit association between music and character. Here, though, it plays in a jazz arrangement as a slow foxtrot. Newman’s arrangement nicely captures the tone of these early scenes, which display the lightness and pacing of other newspaper comedies.

It returns 22 more times in the film. In all, Johnny’s theme accounts for more than a quarter of the film’s 94 music cues. Usually, the theme functions to underline Johnny’s heroism and resourcefulness as in the scene where he gives chase to Van Meer’s assassin. At one point, Johnny even whistles his theme. This occurs in the scene where he eludes a pair of suspicious men posing as police by pretending to draw a bath and crawling out the window.

In contrast, Carol’s theme is used less frequently, appearing in about thirteen cues in all. After its introduction in the main title, it returns when Johnny and Carol first meet at the luncheon sponsored by the Universal Peace Party. Johnny unknowingly insults Carol, first by mistaking her for a publicist, and then by expressing skepticism about the organization’s mission, griping about well-meaning amateurs interfering in international affairs. Newman’s theme hints at Carol’s attraction to Johnny despite his obvious boorishness. The music says what the characters can’t or won’t say. As Johnny and Carol trade insults, Carol’s theme captures the romantic spark that lurks beneath their badinage.

The theme’s other uses often work along similar lines, providing an emotional resonance to the couple’s expression of feelings for one another. A good example is found in the scene where Carol and Johnny huddle together on the deck of a steamship. Here, as a pair of refugees, each member of the couple declare their love for one another and their desire to marry.

Music for the hope of the world

In addition to these two principal themes, the score also utilizes three other themes and motifs to represent important secondary characters. A theme for Professor Van Meer is introduced when Johnny spots him getting into a taxicab.

It returns nine more times in the film in scenes that feature the character or make reference to him.

The theme itself is simple, slow, stately, and quite frankly, a little bit boring. Indeed, if it wasn’t for the multiple references to a “Van Meer Theme” on the cue sheet for Foreign Correspondent, the music would simply blend into the other material that surrounds it.

The orchestration of the theme for solo wind instruments, usually an oboe, gives it a kind of pastoral feeling. The image of peaceful shepherds is likely an appropriate one for Van Meer, who functions as a stand-in for a global desire to avoid armed conflict. Yet, both the character and Newman’s musical theme for him seem nondescript, making Van Meer seem like little more than the walking embodiment of an abstract ideal of world harmony.

Truth be told, Van Meer mostly operates in Foreign Correspondent as the classic Hitchcock MacGuffin–that is, the thing the characters all want, but with which the audience need not concern itself. When Van Meer appears to be assassinated, it sets in motion a chain of events that uncovers a conspiracy organized through Steven Fisher’s World Peace Party. Van Meer is the object that all the characters want to find, and the search for him drives the narrative forward. Yet the character himself has about as much personality as the microfilm in North by Northwest. Newman’s nondescript melody seems to fit the “blank slate” quality of Van Meer himself.

Like the classic MacGuffin, Van Meer’s function as something of an empty vessel allows his theme to be used several times late in the film in scenes where the character isn’t physically present. Although the norm is to use characters’ themes or leitmotifs when they are onscreen, Newman’s treatment of Van Meer shows they can evoke absent characters. This occurs, for example, in a scene where Scott ffolliot explains to Stephen Fisher that he’s arranged for the kidnapping of Carol. Fisher asks ffolliot why he would do such a thing, and ffolliot replies that he wants to know where Stephen has stashed Van Meer.

As we’ll see, Fisher has a theme of his own that itself appears several times in this same scene. But the use of Van Meer’s theme in this context becomes a way of signifying both the character and the peaceful values that he represents – that is, values that Fisher seeks to destroy.

And though Van Meer’s music is a bit dull, the theme proves a bit more interesting when one considers the way it works within Hitchcock’s larger strategies of narration. At a key point, Hitchcock and Newman use the Van Meer theme to mislead the audience about what has just transpired onscreen. I’m referring here to the moment when Van Meer appears on the steps just as the Peace conference in Amsterdam is about to commence.

The theme is cued by Johnny’s glance offscreen after briefly chatting with Fisher, his publicist, and a diplomat. Hitchcock cuts to a shot from Johnny’s optical POV that shows Van Meer climbing up the staircase. We return to Johnny, who smiles and walks out of the frame. Johnny and Van Meer meet in a two-shot where the former offers a warm greeting. A cut to Van Meer’s reaction, though, reveals a blank stare, even as Johnny tries to remind the elderly professor of their previous encounter in the taxi.

The moment is an important one, but before the viewer can even grasp its significance, the two men are interrupted by a request for a photograph. Hitchcock then tracks in on the newsman, who surreptitiously sneaks a gun next to the camera he is holding. He pulls the trigger, and Hitchcock cuts to a brief insert of Van Meer, who has been shot in the face.

As I noted earlier, the assassination we witness is a key turning point in the story, and Hitchcock handles the scene with considerable finesse. Almost unnoticed, though, is the fact that Hitchcock and Newman cleverly use Van Meer’s musical theme as a form of narrative deceit. At first blush, the musical theme helps to reinforce Van Meer’s identity, serving the kind of signposting function that some film music critics believed was a hackneyed device. As we later learn, though, the murder victim is not Van Meer, but rather a double killed in his place to foment international tensions. This information ultimately recasts the old man’s seeming failure to recognize Johnny. As Van Meer’s double, these two men have never actually met.

Has Hitchcock played fair in using Van Meer’s theme for a character that is not Van Meer but only looks like him? Perhaps, but the creation of this red herring is justified if one considers the fact that composers frequently write cues meant to reflect or convey a character’s point of view. Every composer must make a choice about whether to write a cue from the particular perspective of the character or the more global perspective of the film’s narration. Newman might have opted for conventional musical devices that connote suspense (ostinato figures, string tremolos, low sustained minor chords), and these would have signaled to the viewer that Van Meer is in peril, thereby creating a heightened anticipation of the violence that erupts in the scene. Instead, though, following the visual cues provided by Hitchcock’s cinematography and editing of the scene, Newman plays Johnny’s perspective and his recognition of Van Meer as he approaches the building’s entrance. By combining two common tactics–leitmotif and character perspective – Newman and Hitchcock briefly mislead the audience in order to create two surprises: the first when it appears that Van Meer is killed and the second when Van Meer is discovered inside the windmill and proves to be very much alive.

Menace (without the Dennis)

There is also a brief six-note motif used to signify the conspirators as a group. Labeled the “menace” motif, it is introduced just after Van Meer’s apparent assassination. In the chase that follows, Newman alternates between the “menace” motif and Johnny’s theme in order to sharpen the conflict and to capture the ebbs and flows of our hero’s dogged pursuit of the bad guys.

The motif returns, though, at just about any point where one of the group’s henchmen gets up to no good. In the scene inside the windmill, the menace motif appears several times to underscore the kidnappers’ nefarious scheme. Johnny sneaks inside the windmill, and after locating Van Meer, he tries to rescue him only to find out that the elderly professor has been drugged. As Johnny tries to figure out his next move, muted trumpets play the “menace” motif, signaling the kidnappers’ approach and thereby heightening the scene’s suspenseful tone.

Here again, Newman’s thematic organization reinforces a larger narrative tactic in Hitchcock’s film. Herbert Marshall serves as the typical suave villain commonly found in the Master’s oeuvre and Edmund Gwenn steals the show as Johnny’s would-be assassin, Rowley. But the rest of the conspirators are a largely undistinguished lot, and the use of a single motif for the group in toto reflects their relative impersonality. Unlike North by Northwest, where Martin Landau makes a vivid impression as Van Damm’s reptilian assistant Leonard, this spy ring seems to be filled out by thugs from Central Casting.

Father, leader, traitor, spy

Besides motifs for Johnny, Carol, Van Meer and the conspirators, there is also a short motif for Carol’s father, Stephen Fisher. It is harmonically and melodically ambiguous, structured around the rapid, downward movement of a chromatic figure.

In classical Hollywood practice, a leitmotif is usually introduced when the character first appears onscreen. But in an unusual gesture, Newman and Hitchcock resist this convention. The motif does not appear until more than eighty minutes into the film in the aforementioned scene just before ffolliot tries to blackmail Fisher into divulging Van Meer’s location.

By withholding Fisher’s motif, Hitchcock and Newman avoid tipping their hand too early. Since Fisher is later revealed to be the leader of the spy ring, the score circumspectly avoids comment on him in order to preserve the plot twist.

Several cues featuring Fisher’s motif return in the scene where Johnny, Carol, ffolliot, and the other survivors of the plane crash cling to wreckage waiting to be rescued. Carol spots the plane’s pilot stranded on its tail.

He swims over to the group and clambers about the wing. The pilot’s added weight threatens to upend the wing, thereby endangering everyone sitting atop it.

Recognizing this, the pilot asks the others to let him go so that he can simply “slip away.” Fisher overhears this exchange and decides to remove his life jacket and dive into the waters himself, leaving room on the plane’s wing for the rest of crash’s survivors.

The harmonic and melodic ambiguity of Fisher’s motif is most pronounced here, a moment where the character’s duality is also most clearly revealed. Is this a heroic act of self-sacrifice, an act of atonement for the damage Fisher has done to both his daughter’s reputation and his organization’s peaceful cause? Or has Fisher taken the coward’s way out, committing suicide in order to avoid facing the consequences of his actions?

Newman’s rather opaque musical motif doesn’t seem to take sides on this question, leaving Fisher’s motivation more or less uncertain. But this, too, is in keeping with the basic split between the character’s public and private personae. Introduced earlier as Carol’s father, Fisher appears to be cultured and debonair. Yet, when he seeks to extract information from a reluctant captive, Stephen resorts to the physical torments used by two-bit gangsters to make mugs talk. Like those gangsters in the 1930s, Fisher refuses to be taken alive and is swallowed up in briny sea. Still, his action does help to save other lives, and in this way, Fisher enables Carol to find a small measure of grace in the final memory she will have of him.

Putting earworms inside actual ears

As the principal composer of music for Foreign Correspondent, Newman had a major impact on the film’s ultimate success. Yet Newman was not responsible for the music that has engendered the most attention in critical work on the film. I’m referring here to two source cues written by Fox staff arranger, Gene Rose, that are featured in the scene where Van Meer is psychologically tortured. His captors use sleep deprivation techniques to elicit van Meer’s cooperation, including bright lights and the repeated playing of a jazz record. The two cues received rather cheeky descriptions on the cue sheet for Foreign Correspondent: “More Torture in C” and “Torture in A Flat.”

The use of jazz for these cues is likely a little bit of wicked humor on Hitchcock’s part. Despite its popularity as dance music in the 1930s, some listeners undoubtedly believed that jazz was little more than noise with a swinging rhythm. From a modern perspective, though, the scene eerily anticipates the “enhanced interrogation” techniques that would become notorious at Guantánamo and Abu Ghraib. As The Guardian reported in 2008, US military played Metallica’s “Enter Sandman” at ear-splitting volume for hours on end, both at Guantanamo and at a detention center located on the Iraqi-Syrian border. At the other end of the musical spectrum, one of the other pieces played repeatedly was “I Love You” sung by Barney the purple dinosaur. Presumably the first was selected because of its aggressiveness, the latter because of its insipidness. But the Barney song has the distinction of being characterized by military officials as “futility” music – that is, its use is designed to convince the prisoner of the futility of their resistance.

Although, in 1940, Hitchcock could not have envisioned the use of heavy metal and kidvid music as elements of enhanced interrogation, the scene from Foreign Correspondent is eerily prescient. Viewed today, the scene also carries with it a strong element of political critique insofar as it associates such psychological torture techniques with a bunch of “fifth columnists” who are willing to commit murder and even engineer a plane crash in order to achieve their political ends. Touches like these make Foreign Correspondent seem timely today, more than seventy-five years after its initial release.

Alfred Newman the Elder

After Foreign Correspondent, Alfred Newman would go on to score more than a hundred and thirty feature films, and earn several dozen more Academy Award nominations. His nine Oscar wins remain an achievement unmatched by any other film composer. Newman died in Hollywood in 1970 at the age of 69, just before the release of his last picture, the seminal disaster movie, Airport. His work on Airport received an Oscar nomination for Best Original Score, the 43rd such nomination of his long and distinguished career.

For some film music scholars, Newman’s death marked the end of an era, as his career was more or less contemporaneous with the history of recorded synchronized sound cinema in Hollywood. As fellow composer Fred Steiner wrote in his pioneering dissertation on the development of Newman’s style:

As things are, we can be grateful for the dozen or so acknowledged monuments of this twentieth-century form of musical art— absolute models of their kind— that Newman did bestow on the world of cinema. Fashions in movies and in movie music may come and go, but scores such as The Prisoner of Zenda, Wuthering Heights, The Song of Bernadette, Captain From Castile, and The Robe are musical treasures for all time, and as long as people continue to be drawn to the magic of the silver screen, Alfred Newman*s music will continue to move their emotions, just as he always wished.

Because of its typicality, Foreign Correspondent may well seem like a speed bump on Newman’s road to Hollywood immortality. Yet it remains a useful introduction to the composer himself, who along with Max Steiner and Erich Wolfgang Korngold, is part of a triumvirate that would come to define the sound of American film music.

For more on music in Alfred Hitchcock’s films, see Jack Sullivan’s encyclopedic Hitchcock’s Music. For more on the production of Foreign Correspondent, see Matthew Bernstein’s Walter Wanger: Hollywood Independent. Readers interested in learning about Alfred Newman’s career should consult Fred Steiner’s 1981 doctoral dissertation, “The Making of an American Film Composer: A Study of Alfred Newman’s Music in the First Decade of the Sound Era,” and Christopher Palmer’s The Composer in Hollywood.

Tony Thomas’s Film Score: The Art & Craft of Movie Music includes Newman’s own account of his work for the Broadway stage before coming to Hollywood. Readers interested in an overview of the classical Hollywood score’s development should consult James Wierzbicki’s excellent Film Music: A History.

Alfred Newman conducts his most famous film theme, Street Scene, in the prologue to How to Marry a Millionaire (1953).

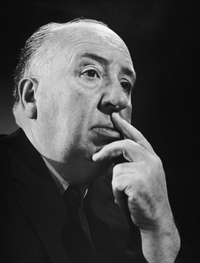

TRUFFAUT/HITCHCOCK, HITCHCOCK/TRUFFAUT, and the Big Reveal

Photo by Philippe Halsman.

I’m going through a Hitchcockian period; every week I go and see again two or three of those films of his that have been reissued; there’s no doubt at all, he’s the greatest, the most complete, the most illuminating, the most beautiful, the most powerful, the most experimental and the luckiest; he’s been touched by a kind of grace.

François Truffaut, letter, 1961

DB here:

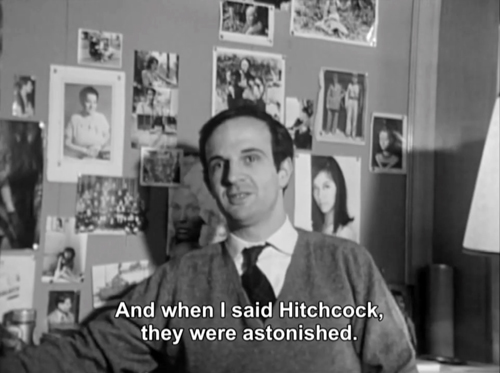

In June of 1962, François Truffaut wrote to Alfred Hitchcock proposing a lengthy interview. Hitchcock agreed, and Truffaut materialized in Los Angeles in August, with his translator and collaborator Helen Scott. After six days of discussion, Truffaut had accumulated, he claimed, fifty hours of tape. Over the next four years the tapes were transcribed, the book was edited, and extra sessions were recorded to cover the films Hitchcock made in the meantime. The result was published in France in late 1966 and a year later in an English translation.

Energetic scholars have recently discovered that the finished book bears signs of massive cutting, compression, and recasting of the conversation. It seems that Hitchcock approved something like the final version, but on this director we want everything. Eventually we will want a complete transcription, but with some tapes still missing, that isn’t possible for now. But we do have some tapes, and just as important, we have the book known in English as Truffaut/Hitchcock.

What Truffaut called his “Hitchbook” is now the subject of fascinating documentary by Kent Jones. Premiered at Cannes, Hitchcock/Truffaut was so successful that an extra screening was scheduled to meet the demand. Why so much interest? Of course, Hitchcock remains a filmmaker known to everyone. But we should also recognize that the Hitchbook was one of the most important books on film ever published.

Popular material treated with intelligence

Alfred Hitchcock, who is a remarkably intelligent man, formed the habit early—right from the start of his career in England—of predicting each aspect of his films. All his life he has worked to make his own tastes coincide with the public’s, emphasizing humor in his English period and suspense in his American period. This dosage of humor and suspense has made Hitchcock one of the most commercial directors in the world. . . . It is the strict demands he makes on himself and on his art that have made him a great director.

François Truffaut, review of Rear Window, 1954

The film’ s title is an impudent reversal: “Hitchcock/Truffaut” puts first things first, a dialogue between a master and his adoring admirer.

At first glance, this is a clips-plus-talking-heads doc. But that impression doesn’t do it justice. For one thing, many of the clips are fresh ones, drawn from rarely shown Hitchcock films. These tease us with their unfamiliarity, like a gallery of less-known pictures flanking a hall of masterpieces.

Moreover, the film’s perspective is far more sophisticated than what we usually find in the genre. Hitchcock/Truffaut respects its viewers enough to summon up suggestive and subtle links between sequences, between image and commentary. Often there’s no title marring the images, so they stand out with a hallucinatory purity. Often a clip starts to play before the commentary kicks in, all the better to let the imagery strike us in its integrity; only then do we get the connection to what came before. The extracts are the prime movers, with the text snapping into place to catch up.

The speed and precision of Hitchcock’s movies are paralleled by the swift opening of Jones’s film, which introduces the main themes. As shots from Sabotage are intercut with the book’s flipping pages, we hear a chorus of voices. These belong to our talking heads, and the heads are full of ideas. Remarkably, all the commenters are film directors. It’s a top-tier lineup, of Movie Brats (Scorsese, Schrader, Bogdanovich) and younger talents David Fincher, James Gray, Wes Anderson, and Richard Linklater. From overseas come Kurosawa Kiyoshi, Olivier Assayas, and Arnaud Desplechin. There are no academic experts, no journalists or friends or family. Everything, we quickly learn, is going to be about cinema as art, craft, and vocation.

Immediately, as if reenacting Family Plot, the film shows how two paths crossed. A quick summary of each man’s career leads to that six-day week in 1962, overseen by the beaming Helen Scott, and our film launches itself into the depths.

We learn of Hitchcock’s urge to outwit the audience, and his thoughts on plausibility. He reviews matters of technique, from image size to the expansion of time. How do you handle actors? How do you give your film a shape? About halfway through, the questions go bigger, and the Cahiers concerns preside. Is M. Hitchcock a Catholic artist? (He gives his answer off-mike.) Is his work haunted by guilt, even Original Sin? (“Yes,” he murmurs.) Don’t the plots enact a transfer of guilt? Don’t they exhibit the logic of dreams?

At one level, Hitchcock/Truffaut is a fine introduction to the issues in French film writing about the Master, articulated most fully by Desplechin. But the Americans bring in plenty of insights as well. Fincher and Scorsese track changing acting styles of the 1940s and hint at the problems those caused for Hitchcock. Schrader notes the recurring fetish-objects (keys, handcuffs) and points out that Vera Miles (Hitchcock’s choice for Vertigo) could never have carried off Kim Novak’s painfully sluttish turn.

Two extended sequences are devoted to Vertigo and Psycho. These allow Jones and his co-screenwriter Serge Toubiana to knot together all the major themes. Vertigo encapsulates the dream elements, and through careful editing Hitchcock/Truffaut turns Hitchcock’s interview remarks into a commentary track under key sequences. Meanwhile, the filmmakers riff freely on what we see. What about Judy’s story? asks Fincher. Scorsese finds “a sense of loss and melancholy.” Judy’s stepping out of the bathroom yields what Gray calls “the single greatest moment in the history of movies.”

But Vertigo wasn’t a huge success, especially for a filmmaker who aimed at arousing the mass audience. The movie that exemplified “pure film,” Hitchcock says, was Psycho. Again our filmmakers are powerfully eloquent about its creative choices (pacing, framing, point-of-view) and, above all, its devastating shocks. It was, says Bogdanovich, “the first time that going to the movies was dangerous.” Psycho’s stupendous popularity, Truffaut remarks in the last edition of the book, made it the capstone of the Master’s career. “I am convinced that Hitchcock was not satisfied with any of the films he made after Psycho.”

Many reviewers of Hitchcock/Truffaut have fastened on moments in the interviews when Hitchcock expressed doubt. Should he have veered off from controlling the “rising shape” of every story? Should he have been “more experimental”? Should he have paid more attention to character rather than situation?

Such questions were raised in Truffaut’s 1983 addendum, but I’m not convinced they’re valid. They presume that plot is less valuable than character, and that thriller plots are somehow intrinsically thinner than other kinds. Truffaut offered the best defense of the power of a gripping intrigue when he suggested that a disciplined format didn’t make things shallow. He suggested that following Hitchcock’s example could be fruitful.

Don’t tell me that it would be inferior or vulgar. Just think of Shadow of a Doubt and Uncle Charlie’s thoughts: the world is a pigsty, and honest people like bankers and widows detest the purity of virgins. It’s all there, but inserted into a framework that keeps you on the edge of your seat.

Hitchcock put it another way: A good film, he remarked, consists of “popular material treated with intelligence.” And that intelligence can take chances. Shadow of a Doubt, Lifeboat, Rope, Rear Window, Psycho, and Family Plot are among Hollywood’s great experiments.

The Figure in the carpet

Storyboard image for Psycho.

My initial aim in undertaking [Truffaut/Hitchcock] was not to make the best-seller list, but to influence and shake up the smug attitudes of the New York critics.

François Truffaut, letter, 1967

Truffaut/Hitchcock had been out for a year when I got my copy in December 1968. Why did I wait? No paperback edition, and the hardback cost a princely $10. That’s about $70 in today’s currency.

That sturdy copy has followed me around ever since, and now, nearly fifty years later, I still find it stimulating. I can’t think of another book on the cinema that has had its influence. Let me count some ways.

It changed tastes. Truffaut tells us that he decided to do the book when he learned that American critics considered Hitchcock as merely a popular entertainer. Not all reviewers needed convincing, though. Robert Sklar found it “likely to become a classic book on the art of the film. . . . No book before this one has made a better case for Hitchcock’s genius or for the French ‘author’ theory of film directorship.”

In the pages of the New York Times, Bosley Crowther had long treated Hitchcock as a talented purveyor of suspense who sometimes gave good value (Rear Window, To Catch a Thief, Vertigo) but who too often favored wildly implausible plots (Strangers on a Train) and “slow buildups to sudden shocks that are old-fashioned melodramatics” (Psycho). Yet the Times granted Truffaut/Hitchcock two admiring reviews. One by Eliot Fremont-Smith declared that Hitchcock had turned out “a surprising number of perfect or nearly perfect movies.” Arthur Knight praised Truffaut’s careful preparation for the encounter and celebrated Hitchcock’s almost unique control over his projects. His films were at once technically adept, emotionally exciting, and bristling with what Truffaut called “moral dilemmas.”

In the pages of the New York Times, Bosley Crowther had long treated Hitchcock as a talented purveyor of suspense who sometimes gave good value (Rear Window, To Catch a Thief, Vertigo) but who too often favored wildly implausible plots (Strangers on a Train) and “slow buildups to sudden shocks that are old-fashioned melodramatics” (Psycho). Yet the Times granted Truffaut/Hitchcock two admiring reviews. One by Eliot Fremont-Smith declared that Hitchcock had turned out “a surprising number of perfect or nearly perfect movies.” Arthur Knight praised Truffaut’s careful preparation for the encounter and celebrated Hitchcock’s almost unique control over his projects. His films were at once technically adept, emotionally exciting, and bristling with what Truffaut called “moral dilemmas.”

As Sklar indicates, Truffaut/Hitchcock gave aid and comfort to auteurists. If you wanted to make a case for creative artistry in Hollywood, Hitchcock was the logical point man—a cinematic virtuoso and a director whose films were instantly recognizable. Andrew Sarris’s first Village Voice review set the tone: Psycho indicated that “the French have been right all along.” The English critics of Movie followed with vigorous analytical essays, while Robin Wood’s probing thematic study Hitchcock’s Films (1965) may have helped establish an audience for Truffaut’s book. Truffaut predicted in 1983 that “By the end of the century, there will be as many books written about him as there are now about Marcel Proust.” The prophecy may well have been fulfilled, and in a new century the literature seems to be swelling even faster.

The book affected tastes in another way, I think. It appeared when French filmmaking enjoyed great prominence in America. Unlike what happened in later decades, in the 1960s and early 1970s we could see virtually everything being made by Truffaut, Varda, Chabrol, Demy, Resnais, Bresson, Rohmer, Melville, and other major filmmakers; Godard sometimes gave us three a year. There were middlebrow hits too, like Sundays and Cybèle (1962) and A Man and a Woman (1966). It seems hard to believe now, but in 1966-1967, twelve numbers of Cahiers du cinéma were published in a handsome English-language edition. Just as important, the year 1967 brought America not only Truffaut’s book but Hugh Gray’s translation of Bazin’s What Is Cinema?

For years afterward, France set the tone for both arthouse distribution and serious cinephilia. Importers brought us La Cage aux Folles, Tous les matins du monde, Amélie, Ma vie en rose, and other vessels of Gallic charm and profundity. Journalists and programmers stalked through French festivals searching for the next big auteurs. Later, academics learned about semiology, neo-Marxism, and Lacanian psychoanalysis from their Parisian counterparts. To this day, critics beg their editors to send them to Cannes and academics beg presses to consider another book on Deleuze. The Hitchbook helped establish France as the home of adventurous thinking about cinema.

Master and disciple

I’d like everyone who makes films to be able to learn something from it, and also everyone whose dream it is to become a filmmaker.

François Truffaut, letter, 1962

It influenced filmmakers. Jones’ documentary highlights the Hitchbook’s enduring power for generations of directors. Wes Anderson says that his copy has fallen to tatters; Fincher read his dad’s over and over, marveling at how the layout of images made the editing patterns apparent. For the young Gray it was “a window into the world of cinema.” The book, says Scorsese, gave courage to a generation: “We became radicalized.” It showed that he and his cohort “could go ahead.”

The book’s impact came from its insider aspects. As Schrader points out, we already had many books about the art of cinema, but Hitchcock shared secrets of craft. How did he get particular effects, like Foreign Correspondent’s plane crash, with the ocean bursting straight into the cockpit? Hitchcock had views on what made film art (montage, mostly) but he also knew, as Fincher puts it, what made it fun. The flagrant virtuosity which Hitch’s detractors attacked was a powerful stimulant for 1960s filmmakers. The chef has taken us into the kitchen and revealed his recipes.

Take camera placement. Many of today’s moviemakers and TV directors are fairly indifferent to the niceties of framing. Scorsese crisply shows how important the high angle is in Hitchcock’s work. You can read it thematically (God looking down) but it’s also elegantly functional. In Topaz, Scorsese points out, the camera’s deviation from the straight-on view is unsettling, and it accentuates the defector’s eye movements. An unexpected, queasily close high-angle is practically a Hitchcock signature, as here from The Man Who Knew Too Much and North by Northwest.

Beyond their craft, Hitchcock films yielded a personal vision of the world. That vision wasn’t a matter of messages articulated in clunky dialogue (vide Stanley Kramer). Hitch’s personality soaked into the very textures of his plots, his characterizations, and above all his attitude toward the story and the audience. The Cahiers critics had found individual expression in the Hollywood studio product, and Hitchcock’s world revealed some fairly sordid corners.

He was obsessed with looking, duplicity, doubles, and hidden identities. Some of his characters, such as Uncle Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt and John Brandon in Rope, are suave sociopaths. In Notorious, the putative hero is a cynical bully, while the Nazi he’s stalking is a gentle and charming husband. A detective obsessed with a woman manages to kill her twice; a husband who wishes his wife dead gets what he wanted. The plots pass harsh judgment on momentary slips, like looking out your back window, listening politely to a loopy train passenger, or placing imaginary racetrack bets. If Ben Jonson lifted sardonic misanthropy to the level of art, why couldn’t Hitchcock?

It’s as if the Movie Brats and those who followed were scoping out the realities of the business they were entering. I think they took hope from a man who made a great deal of money working with stars, flummoxing producers (Selznick in particular), embracing new technologies (sound, widescreen, even 3D), and managing to put an idiosyncratic spin on forced-march projects. It’s easier to reconcile the one-for-them-and-one-for-me dynamic when you remember what Hitch made of assignments like Rebecca, Dial M for Murder, and (even) Topaz. By letting Hitchcock explain the commercial pressures he faced, and the ways he found to dodge or work within them, Truffaut must have given young filmmakers a conviction that they could do personal work in the industry.

Pictures that work hard

The interest of the book will lie in the fact that it will describe in a very meticulous fashion one of the greatest and most complete careers in the cinema and, at the same time, constitute a very precise study of the intellectual and mental, but also physical and material, “fabrication” of films.

Francois Truffaut, letter, 1962

It influenced film criticism too. For one thing, it confirmed the interview as a legitimate critical tool.

Truffaut didn’t invent the cinephiliac director interview, of course. Cahiers and Movie undertook interrogations of directors; Pauline Kael notably mocked Movie for asking Minnelli about a crane shot. But after the revelations of Truffaut/Hitchcock, people who wanted to put movies down couldn’t automatically assume that directors were inarticulate. Yes, they’d recycle their favorite stories, usually mythical; yes, they knew ways to dodge the hard questions; but get them going on craft and you stood a chance of learning something. The god of cinema dwelled among the details, and Hitchcock spread out details with solemn largesse.

Sarris had displayed some of the possibilities in his Interviews with Film Directors (1967 again!). But that book republished interviews already out there. Truffaut’s through-composed marathon showed the power of the interview format as an analytical probe. Today, nobody would think of writing about a filmmaker without consulting published interviews—or better yet, trying to wangle a fresh one. The book-length interview has become a genre, as in the X-on-X series from Faber and Faber and, more lavishly, Matt Zoller Seitz’s books on Wes Anderson.

Furthermore, despite Truffaut’s insistence on Hitchcock’s commitment to “pure cinema,” the book gave new credence to a quasi-literary approach to film criticism. Truffaut repackaged the Cahiers thematic interpretations of Hitchcock. A film’s true meanings were elusive; they had to be unearthed. Films could now be read. Once we could find Catholic guilt in Strangers on a Train and an omniscient, perhaps bemused deity in a high angle, why not extend the strategy to other filmmakers? It seems to me that Truffaut/Hitchcock was a major step toward our apparently endless efforts to find hidden meanings in popular filmmaking.

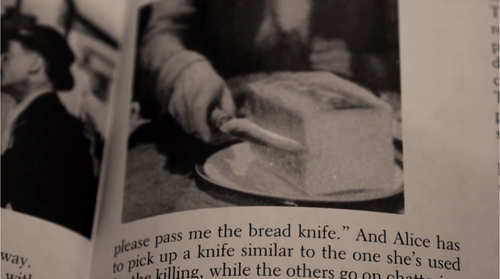

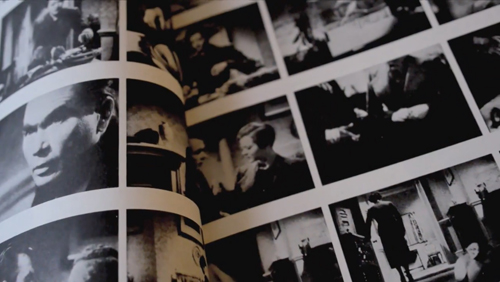

To his credit, Truffaut understood that such reading had to be very close. He needed pictures. His correspondence details his demand that the illustrations “correspond exactly to Hitchcock’s own comments on the film.” Truffaut shrugged off any worries about permissions. Film books of the day, when they included pictures, used production stills—photos taken on the set, which seldom corresponded to what was on the screen. Truffaut used some production stills, but he took pride in packing in genuine frame enlargements, actual images from film prints. I can think of only one earlier author who systematically deployed actual frames to illustrate points of technique: Sergei Eisenstein, in The Film Sense (1943) and Film Form (1949).

To his credit, Truffaut understood that such reading had to be very close. He needed pictures. His correspondence details his demand that the illustrations “correspond exactly to Hitchcock’s own comments on the film.” Truffaut shrugged off any worries about permissions. Film books of the day, when they included pictures, used production stills—photos taken on the set, which seldom corresponded to what was on the screen. Truffaut used some production stills, but he took pride in packing in genuine frame enlargements, actual images from film prints. I can think of only one earlier author who systematically deployed actual frames to illustrate points of technique: Sergei Eisenstein, in The Film Sense (1943) and Film Form (1949).

Today, when hundreds of websites run clips and framegrabs, we need to remember just how bold and tenacious Truffaut was. He borrowed 35mm prints from studio archives and spent three days in London making stills from the British titles not available in France. He could then provide meticulous shot-by-shot presentations of sequences—central to proving the artistry of a man who put editing at the center of film art. The original French edition flaunted its production values, slugging frames from the Psycho shower sequence across front and back cover.

Once Truffaut made such displays thinkable, film criticism could become more analytical. Enterprising writers got hold of prints, projected them incessantly or studied them on editing machines. Most notable was Raymond Bellour, whose 1969 analysis of The Birds (below) pushed analysis to an unprecedented degree of exactitude.

Throughout the 1970s, film critics became more adept at this shot-by-shot study. It was one hallmark of my generation of academic film writers, especially in dissertations. That group included Ted Perry at Iowa (in a dissertation on L’Eclisse, 1968) and NYU scholars Fred Camper, Paul Arthur, and Vlada Petrić. P. Adams Sitney’s trailblazing Visionary Film (1974) brought this sort of scrutiny to the avant-garde tradition. I followed the same line in my 1973 monograph on La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc and in my 1975 dissertation on 1920s French cinema.

Throughout the 1970s, film critics became more adept at this shot-by-shot study. It was one hallmark of my generation of academic film writers, especially in dissertations. That group included Ted Perry at Iowa (in a dissertation on L’Eclisse, 1968) and NYU scholars Fred Camper, Paul Arthur, and Vlada Petrić. P. Adams Sitney’s trailblazing Visionary Film (1974) brought this sort of scrutiny to the avant-garde tradition. I followed the same line in my 1973 monograph on La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc and in my 1975 dissertation on 1920s French cinema.

French scholars were following Bellour’s lead, and a significant school of textual analysts emerged. The BFI magazine Screen opened up similar avenues with Stephen Heath’s 1975 analysis of Touch of Evil. A few teachers started to incorporate frame enlargements as slides for lecture courses. Kristin and I did, while inserting frame enlargements into our publications. We may have been the first to publish a film aesthetics textbook, Film Art (1979), relying on actual shots, not production stills.

Studying films shot by shot was difficult, requiring 16mm or 35mm prints and machinery like analysis projectors and flatbed viewers. To document the shots, you had to take frame enlargements with a bellows and a still camera. By the time videotape and laserdiscs came along, intensive study was far easier. Not until we got DVD technology, though, was it simple to make decent frame grabs to illustrate critical pieces.

Now everybody does what Truffaut did. But let’s remember that we analysts, along with nimble video essayists like Seitz, Kevin B. Lee, and Tony Zhou, owe a debt to Truffaut’s obstinate insistence that “quoting” a film, even partially, allows us to understand it more deeply.

Looking in his direction

This book on Hitchcock is merely a pretext for self-instruction.

François Truffaut, letter 1962

Given Truffaut’s deep admiration for the Master of Suspense, we’ve long assumed that he tried to learn from him. Like Hitchcock, he cared very much about evoking a response from his audience, and he sought as well to master the disciplined technique that could create precise effects. As early as The 400 Blows, he had Hitchcock in mind, as he confessed in the interview.

The recent availability of the 1962 tapes enabled Hitchcock scholar Sidney Gottlieb, in an article teasingly titled “Hitchcock on Truffaut,” to explore portions of the conversation in which Hitchcock comments on a key passage in Truffaut’s film. Truffaut tells Hitchcock of the moment when Antoine Doinel and his schoolmate, playing hooky, catch his mother kissing her lover on the street. Antoine rushes off and she guiltily turns away, telling her lover that her son has recognized her. Hitchcock, who apparently hasn’t seen the film, asks about Truffaut’s intention and tries to visualize the scene.

Jones’ film smoothly incorporates the sequence, letting the men’s voice-over discussion provide a gloss. The passage allows us to pinpoint some important aspects of Hitchcock’s discipline.

Truffaut is shooting on location, with a camera that’s often very far from the action. We see the boys walking right to left in an extreme long shot, and then we cut to another extreme long shot, in which Antoine’s mother and the lover are embracing by a Métro entrance. They are centered, but there’s a great deal of city life in this frame as well, so one can easily miss them. Even if we notice the couple, we can’t clearly recognize the woman as the mother.

In order to make clear what’s happening at the Métro entrance, Truffaut gives us two further shots of the couple. The first conveys only the act of kissing; we can’t really identify the characters. The second shot reveals that the woman is Antoine’s mother.

Truffaut indicates to Hitchcock that he was short of footage, but there’s also the problem of shooting on location. Truffaut could have cut directly from the extreme long-shot to reveal the mother (that is, from my second shot to my fourth). But that would have been rather disjunctive, and without the railing in the third shot we wouldn’t know the characters’ orientation very clearly. The shot of the railing indicates that we’re roughly opposite to the angle taken in the extreme long shot. Still, the whole series—three shots needed to establish that the mother has a lover and is kissing him—is somewhat uneconomical.

Having given us important information about the mother’s affair, Hitchcock might have made us wait longer, raising suspense about whether Antoine would discover the illicit couple. Instead Truffaut cuts immediately to a panning shot of Antoine and his pal passing and looking more or less to the camera. That’s followed by a shot of the mother seeing Antoine and turning abruptly away. The boys also turn away and hurry off.

We’re in the familiar territory of constructive editing and the Kuleshov effect. There’s no establishing shot that includes all the dramatic elements. Similarity of locale, the exchange of glances, continuity of sound effects, and the concept (they see each other) knit the shots together.

Again, though, there’s a certain roughness to the effect. The second shot of the mother looking into the camera seems to be roughly Antoine’s point of view, but that camera setup has already been given us as an “objective” shot of her kissing her partner. Apart from the eyeline, there isn’t any marker of the second one as subjective—such as a sidelong camera movement that might correspond to Antoine’s walking viewpoint. POV shots can be slippery in classical filmmaking, so it’s not exactly an error, but Truffaut gave up the chance for a more nuanced variant.

The couple’s placement remains a little vague in this shot too, again because there’s no railing to orient us. If the mother is more or less blocked by her lover (her back is to the railing), her later glance at Antoine must fall quite far down the sidewalk on her left. But when he passes he’s further up the sidewalk, on her right. Yet he’s supposedly looking more or less directly at her.

Put it another way. In the physical terms given by earlier shots, the lover’s back would hide the mother from Antoine until he was quite far down the sidewalk on her left. He’d have to turn back to see her. Yet the boy seems to be looking at her from a position more or less opposite her, in effect “through” the lover’s back.

Plainly we get the point of the scene. But there’s a certain roughness to the presentation. That may be why Truffaut felt he needed the return to the railing setup to show the mother turning away, followed by an explicit underscoring of what just happened through dialogue.

Hitchcock, a little sadly: “I would’ve hoped that there was nothing spoken.”

Truffaut admitted to Hitchcock that he didn’t have enough footage and was forced to intercut the shots too much. “In the cutting room it was absurd. . . . It was less good than if I’d thought it out beforehand. Then I would have had a variety [of shots].”

In the interview Hitchcock goes on to remake the sequence at one remove. He suggests that we could start with Antoine walking and markedly seeing the mother. Then we see her turn, “looking in his direction.” The boy turns away, then she turns away. Simple and straightforward.

To get a concrete example, consider how Hitch directed a scene of one person catching another by surprise. In Stage Fright, the blackmailing maid Nellie Goode has come to the garden party to squeeze more money from Eve Gill. Hitchcock shows us that Nellie is present and then shows Eve and Ordinary Smith approaching unawares in a distant shot—more or less from Nellie’s optical standpoint.

Thus the shot of the person seen is anchored in relation to the person seeing. After a reverse angle on Nellie, with the long-shot scale more or less matching its mate, we get a shot of Eve noticing Nellie.

We have another piece of constructive editing, but we scarcely notice the absence of a master shot. The geography is crystal clear, not least because of the marked eyeline. And now, as in Truffaut’s scene, an objective framing becomes subjective. We get a parallel series of shots, one setup showing Nellie advancing, the other a tight framing just on Eve, who halts Nellie by signaling with her eyes and mouth. On the couple, the framing has gone from long-shot to two-shot to single.

When Nellie stops, puzzled, Eve launches her plan to send Smith off to her girlfriends. Eve leaves, Smith follows, and we’re back to Nellie watching in annoyance.