Archive for the 'Directors: Hong Sangsoo' Category

Dragons, tigers, and two programmers

Yellowing (Chan Tze Woon, 2016).

DB here:

It was Asian film that brought me to the Vancouver International Film Festival in 2006, when Tony Rayns asked me to serve on the Dragons and Tigers awards jury. Ever since, Kristin and I have been returning; Tony made VIFF North America’s prime venue for cutting-edge Asian film. Name a major director from the region, and you’ll find that Tony scouted his or her early work for Vancouver.

For some years now, Tony’s co-programmer has been Chinese cinema expert Shelly Kraicer, who has been no less energetic in seeking out exciting new films. You can survey their track record by scanning our VIFF blog entries across the years.

Out of the many films in this year’s D & T retrospective, here are five that I especially admire.

Genres redux

Godspeed.

Across his career, Kore-eda Hirokazu has been a genre pluralist, but in recent years he seems to have settled into the shomin-geki, the bittersweet tale of lower-middle-class life. On the heels of Our Little Sister comes another family dramedy, After the Storm.

Once a prize-winning novelist, Ryota (the lanky, lantern-jawed Abe Hiroshi) is now a racetrack addict and a cheap detective not averse to shaking down high-school kids. After his father dies, and under the jaundiced eyes of his mother, he makes feeble efforts to reunite with his divorced wife and his baseball-playing son.

As usual with Kore-eda, everything flows in simple, unforced fashion, with every shot trimly composed and expertly timed. The emphasis falls on the actors, particularly as they’re captured in mundane activities. Ryota’s mother and sister are first seen writing thank-you notes to people who came to the funeral; he swills in fast food and throws away money on lottery tickets.

Ryota is one of Kore-eda’s most objectionable protagonists. He uses his admittedly minimal surveillance skills to spy on his wife, and he tries to swipe a family scroll to pawn. In an American film, this unlikable loser would pass through an arc that makes him caring, sharing, and on the road to rehab. Instead, as in many Japanese films, the unhappy character relapses into childhood—here, curling up with his son inside a playground octopus during a typhoon. It’s his effort to mimic a bonding moment with his father, but does it succeed now? Kore-eda isn’t betting on it.

Altogether less tranquil is Godspeed, from the Taiwanese director Chung Mong-hung. Chung has given us the horror film Soul (2013), the well-received Fourth Portrait (2010), and the lively Parking (2008), which I reviewed at an earlier VIFF session.

Godspeed is a Tarantinoish excursion into the underworld. It alternates violent scenes of betrayal and reprisals with comic interludes involving a drug courier and the taxi driver he’s hired to carry him to meet the bosses. The film is made with great panache, but for me what makes it noteworthy is that the driver is played by the great Michael Hui, dean of sour Hong Kong social satire.

Hui made his name as a television star before switching to films like The Private Eyes (1976), Security Unlimited (1981), and our favorite, Chicken and Duck Talk (1988). Godspeed revives Hui’s comic persona, the tight-fisted, corner-cutting bargainer who isn’t as clever as he thinks. As Old Xu, he reminisces about Hong Kong traffic and marital woes while trying to wangle a high fare from the phlegmatic, not overbright drug mule. Their misadventures—stumbling into a funeral, being stuffed into a car boot—serve as a counterpoint to the drug war escalating around them. No masterpiece, Godspeed is a beguiling exercise and a welcome return to a legendary and apparently ageless figure of Chinese cinema.

Mysterious, and fun

Another year, another stroll through Hong Sangsoo’s garden of forking paths.

With compositions that are about as banal as they can be, the films don’t aim to dazzle us pictorially. (Nice lighting, though.) The basics are really basic: Straight-on angles, fixed long take two-shots, simple come-and-go pans, an occasional and inexplicable zoom. These are his tools.

Dialogue and performance drive the action, which consists mostly of chance encounters and conversations in cafés, bars, restaurants, and bedrooms. His characters are students, artists, and film directors (usually fairly pretentious ones). Romantic hookups emerge, only to dissolve or play themselves out in parallel worlds, the whole presented in a “stacked” arrangement of modular scenes.

These scenic blocks display an obsessive, almost never mechanical, recourse to split viewpoints, recursive time schemes, mirror inversions, and whimsically varied replays. I’ve argued earlier that these permutations often test our faulty memory for exactly what transpired in a scene many minutes before, but it should be noted that sometimes, as in the last stretch of Oki’s Movie (2010), he’ll set the variations side by side.

Or maybe just side by side in your head. If the auteur theory didn’t exist, it would have to be invented to account for the effect of Yourself and Yours. In any other movie, when a man recognizes a young woman in a café, and she says he’s mistaken her for her twin, we might be inclined to take it as a brush-off. In a Hong movie, the scene makes us think back through all his other plots that have relied on doubling. So maybe this time he’s found a new variation? Has he got an actual pair of twins who will circulate through the scenes, constantly being taken for one another?

Suffice it to say that the young woman (women?), repeatedly encountering three men who are attracted to her (them?), becomes (become?) the pretext for the usual Hong mockery of male vanity and insecurity. The lackadaisical painter Youngsoo is worried about his girlfriend Minjung, who drinks more than he’d like. Moreover, his friend reports that she’s been seen with other men. Quickly enough, we spot her sharing drinks with an older man and a film director—who discover that they are old classmates. “This is mysterious,” the director remarks, “and fun.” None of the would-be Romeos notice that the lady in question is reading Kafka’s The Metamorphosis.

Hong always has another card up his sleeve, and Yourself and Yours, while not as ingenious as his previous entry Right Now, Wrong Then (2015), is satisfyingly teasing. It also yields one of the most flagrantly self-indulgent trailers I know: faithful to the movie, but frustrating in just the right ways.

Taking it to the streets

When college students en masse join a movement for social change, their positions tend to be vindicated in the long run. In the United States, students were right to support movements against nuclear proliferation, against racial discrimination, against American involvement in Vietnam, for women’s liberation and LGBT rights, against the invasion of Iraq, and, right here in Wisconsin, against Republican union-busting and voter suppression. The same pattern can be observed around the world, in student protests in Europe, South America, and Asia. Elders deride students as naïve, but more often than not, student activists critical of the status quo get principled politics right.

Why? I suspect several causes, including the fact that many (not all) students are reading, thinking, and learning while the general populace trudges through the dull compulsion of everyday labor. College flings together students from many backgrounds and may open eyes about how other people live. (Right-wingers worry too much about liberal professors indoctrinating students. In my experience, students are more influenced by their peers than by the likes of me.) And of course the flexible scheduling of college days allows motivated students the time to engage in political action.

Whatever the causes, it’s no surprise that in Hong Kong, the street protests running from September through December of 2014 were launched by young people. In August the mainland’s Communist Party decreed that instead of direct election of the territory’s Chief Executive, candidates would be chosen by a nominating committee comprised of businessmen and politicians sympathetic to Beijing. In effect, this guaranteed a puppet leader of the type all too familiar in the territory. Students responded by organizing actions similar to the Occupy movement in America. With surprising speed, civil disobedience and sit-down occupation spread through downtown areas of Hong Kong Island and the Kowloon Peninsula.

Hong Kongers were long considered indifferent to politics, only concerned with scrambling to get ahead and make money. But the world had to notice when tens of thousands of students and ordinary men and women built vast encampments in the streets in front of chic shops and noodle restaurants. Wearing yellow ribbons and hard-hats, and armed with umbrellas to protect them against sun, rain, and tear gas, they were apparently ready for a long stay.

This epochal event in Hong Kong history is documented in Yellowing, a new film by Chan Tse Woon. It was made under the auspices of Ying e chi, a filmmaking collective that has been working since the propitious year 1997, when the British turned the territory over to the People’s Republic. Although framed as a diary, it’s basically a cinéma vérité account of moments and vignettes of the Umbrella Revolution. The voice-over narration is keenly personal, beginning with home-movie footage of Chan’s childhood and youth, interrupted by his memory of repeated promises that democracy would soon arrive.

Loosely organized, Yellowing offers no systematic chronology of events à la a PBS program. It’s defiantly local, a snapshot album for Hong Kongers who will recognize each phase of the movement. At the start, some gorgeous nighttime cityscapes are shattered by confrontations with police (“Police, retreat,” the students chant) and conversations with student organizers in their down time. In the two hours that follow, we spend a lot of that time with young people like the ceaselessly beaming Rachel, who’s now considering becoming a civil rights lawyer. We see one boy passing out wristbands reading, They can’t kill us all.

Students set up tents, squat in pounding rain, organize English classes, and run supply chains across the vast areas of occupation. There are clashes with police and civilians. (“Your flesh and blood belongs to your family,” a man charges.) Chan’s camera captures, helter-skelter, assaults from cops and street gangs. There are camera duels, with police filming demonstrators while demonstrators film police. Chan’s voice-over says that he thought his camera would protect him, but he still gets punched in the face. The occupiers practice tactical evasion and passive resistance, but there’s no effort to heroicize them. Many are crying as police lead them away.

Despite the almost casual presentation, you realize how much these kids are risking. Many are poor, some are trying to hang onto a job, and nearly all realize that this will change their lives. “Even if we lose this fight, we’ll lose together.” As for the angry citizens wearing blue ribbons declaring support for authorities, the students are sympathetic: “Don’t you think they need democracy too?”

The film circles back to the opening, with Daddy-cam shots of children. We hear Rachel writing in reply to a professor who had urged the students to give way for the sake of “security,” and to stop being tools of “foreign subversion.” The film lingers on her cheerful, polite suggestion that Mainland domination has replaced British colonialism, and that the children of the future deserve better.

Most of our politicians and all of our plutocrats will never know the sort of courage that these young people displayed with modest, good-humored tenacity. Unarmed—unlike the Y’all Queda fraidycats who occupied our Oregon wildlife refuge—these unprepossessing kids stood a very good chance of being brutalized by a government not known for recognizing the niceties of due process. You feel proud of the young people of Hong Kong while watching this heartbreaking, hopeful film. As often happens, the students were both righteous and right.

Not hope, fear

Ying e chi has often worked with theatres to show independent films, but Yellowing has been denied a theatrical release. Instead, Variety reports, producer Vincent Chui has arranged for guerrilla screenings. Five ticketed shows were held at the Hong Kong Film Archive, in order to qualify for this year’s Hong Kong Film Awards.

The resistance to Yellowing doubtless owes a lot to the controversy surrounding another film, Ten Years (2015). It won astonishing success in local theatres. According to Maggie Lee in Variety, it cost only US$65,000 but earned nearly $800,000 before Beijing realized how subversive it was and blasted it as a “thought virus.” Ten Years was nominated for a Hong Kong Film Award, which made the PRC cancel television coverage of the ceremony. When the film won the Best Picture prize, shock waves went through the film community, and it was denounced by producers and executives. It was soon cast out of theatres, but screenings continued in community centers, churches, and outdoor venues. It’s slated for a DVD release soon.

Ten Years consists of five shorts linked by the premise of local life in 2025. In its dystopian portrayal of Mainland domination of Hong Kong, it’s a fairly direct outgrowth of the Umbrella Revolution. But if Yellowing documents the movement’s hope, this film exposes, as many commentators have noted, fear.

One episode, “Extras,” dramatizes behind-the-scenes scenes political machinations as a sort of noir comedy. Two hapless thugs are hired to stage an assassination attempt that will arouse public support for a new security law. While the men rehearse their gun choreography, the puppeteers debate whether killing or wounding the targets would play better in the media.

Other episodes are more concerned with the cultural impact of Beijing’s dominance of local life. “Season of the End” presents scientists searching rubble for signs of now-vanished Hong Kong life, shot in ominously clinical detail. “Dialect” presumes that Mandarin is becoming the official language of the territory, and we see a taxi driver struggling to cast off his Cantonese. “Local Egg” also centers on language. Here a shopkeeper is forbidden to use the word “local” because it suggests those political factions struggling to keep Hong Kong distinct, or maybe pushing it to become independent. In an echo of the Cultural Revolution, this episode shows schoolkids in uniform arriving with iPads to check shops’ compliance with the list of forbidden words and retail items.

The most emotionally wrenching episode, “Self-Immolator,” is a pseudo-documentary. Startling scorch-marks on the sidewalk are the traces of someone who burned to death in protest of government oppression. Through talking heads, a collage of demonstration footage, and some investigation, the film traces how a young man’s hunger strike led to the mysterious self-immolation. Several candidates for the self-sacrifice are canvassed before, in a break with the documentary frame, the protest suicide is shown. In the conclusion, an umbrella is seen aflame, perhaps forming a requiem for the 2014 protests.

Ten Years is a good example of how a film can have social importance because of the moment at which it emerges. Along with Yellowing, it will be a lasting memorial to the struggles of Hong Kong people to introduce democracy to China.

Thanks to Tony and Shelly for all their work in setting up these screenings. In addition, Kristin and I are grateful to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, and Jennie Lee Craig and their colleagues for making our VIFF visit so enjoyable and enlightening. Special thanks to Tallulah for cheerfulness and Lillooet for the waffles.

Thanks to our regular attendance at VIFF, we’ve discussed many of Hong Sangsoo’s films; see the director category.

The development of the Umbrella Revolution is traced in this long New York Times story. Last August, accused student leaders got surprisingly light sentences. Some of the “localists” and Occupiers won places in the Legco elections and are expected to make waves.

Tony Rayns and Shelly Kraicer.

What-if movies: Forking paths in the drawing room

Dangerous Corner (1934).

DB here:

We habitually indulge in what-if thinking. What if you hadn’t gone to that particular school, met those specific friends, lived in that particular place? Your future would have been very different, in ways you sometimes speculate about. Here is Brian Eno explaining how he found his career:

As a result of going into a subway station and meeting Andy [Mackay], I joined Roxy Music, and as a result of that I have a career in music I wouldn’t have had otherwise. If I’d walked ten yards further on the platform or missed that train or been in the next carriage, I probably would have been an art teacher now.

We think this way on a small time-scale too. If you had left that damned parking lot a little earlier, you wouldn’t have had the fender-bender you had down the street.

Just as flashbacks exploit our common-sense intuitions about memory, other narrative strategies tap our habit of what-if thinking. Some movies evoke alternative but parallel fictional worlds. The most recent what-if movie I know is Edge of Tomorrow, whose tagline and video release title, Live Die Repeat, sums up its premise. I thought it was an ingenious use of the format, although the ending left me puzzled. Earlier on this site I wrote about a more intriguing example, Duncan Jones’s Source Code. Sometimes I call these “multiple-draft” plots because they keep revising the action until it comes out right.

Hong Sangsoo has explored the what-if possibility with unusual energy, but he’s less explicit about setting up the structure than Hollywood films are. With his movies, sometimes you don’t realize you’re in a parallel-world plot until you notice repetitions of action with tiny differences. (We have entries on Hong here and here and here.)

Some years back I wrote an essay, “Film Futures,” in which I analyzed the what-if, or “forking-path” narrative. That essay, revised for the book Poetics of Cinema, is now available on this site. It explores several examples: Kieślowski’s Blind Chance, Tykwer’s Run Lola Run, Wai Ka-fai’s Too Many Ways to Be Number One, and Peter Howitt’s Sliding Doors.

One Hollywood experiment in this vein was a film version of J. B. Priestley’s 1932 play, Dangerous Corner. I mentioned the play in the essay, but I wasn’t then aware that a film version had been made by RKO in 1934. (To add an extra sting to my ego, it was sitting in our massive collection of RKO movies on campus.) I learned of it just recently when it aired on Turner Classic Movies, a national treasure I have celebrated before. The film quickly showed up online at Rarefilmm, and probably elsewhere.

In the essay, my approach was to treat these films as a sort of genre. What conventions rule them? What motivates the forking-path format—a science-fiction device such as a time machine, or fortunetelling, or something else? How do they tap our what-if thinking? Dangerous Corner lets me test my proposal on a new instance and offer a trailer for a new online essay.

As with any comprehensive narrative analysis, there are spoilers.

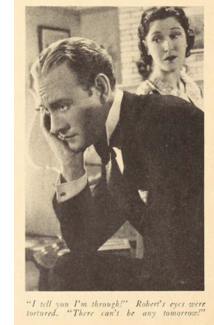

They have been here before

Darkness. We hear a gunshot and a woman’s scream. The stage lights come up and reveal some women in a drawing room listening to a radio play, “The Sleeping Dog.” Soon they’re joined by their male partners. An inadvertent remark by one of the women starts a cascade of confessions. The couples reveal a seething mass of illicit affairs, drug addiction, and repressed sexual desires.

As a result of the frenzy of truth-telling, the husband who set the process in motion lurches offstage and shoots himself. Darkness descends; a woman’s scream. When the lights come up, we are back in the drawing room. The broadcast play is at the same point as before. This time things go differently, and music from the radio fills the room as the couples enjoy a banal evening.

The action centers on three men who are partners in a publishing house. Robert is married to Freda, Gordon is married to Betty, and Charles is unattached. The young woman Olwen works at the firm, and Robert’s dissolute brother Martin is dead when the plot begins. The action centers around some missing bonds, which either Robert, Charles, or Martin stole a year earlier. Soon after the bonds went missing, Martin was found shot dead, an apparent suicide. He was assumed to have been the thief.

The action centers on three men who are partners in a publishing house. Robert is married to Freda, Gordon is married to Betty, and Charles is unattached. The young woman Olwen works at the firm, and Robert’s dissolute brother Martin is dead when the plot begins. The action centers around some missing bonds, which either Robert, Charles, or Martin stole a year earlier. Soon after the bonds went missing, Martin was found shot dead, an apparent suicide. He was assumed to have been the thief.

In the course of evening number one, all sorts of naughtiness are revealed. Martin, much loved by all, is revealed to have been a thrill-seeking drug addict with whom Robert’s wife Freda has been having an affair. Olwen is secretly in love with Robert. Gordon’s wife Betty is Charles’s mistress. Gordon in turn is in love with Martin, and we’re to understand they’ve had an intermittent gay affair. Martin has died not by suicide but by accident, when Olwen was struggling to escape from his attempt to rape her. In all, the three publishers’ private lives would suffice for a steamy best-seller.

The point of Priestley’s play is that revealing the truth is a risky business, like driving around a dangerous corner. He uses the forking-path format to suggest the harm of revealing things best kept hidden. Hence the radio play’s title, a reference to letting sleeping dogs lie. For Priestley, however, the parallel-worlds conceit was more than an artistic device. He insisted that Dangerous Corner not be regarded as a dream play but rather “a What Might Have Been.” It proceeded from Priestley’s deep interest in time, which he saw as not merely the linear, “once-and-for-all” track of daily life.

Our real selves are the whole stretches of our lives, and . . . at any given moment during those lives we are merely taking a three-dimensional cross-section of a four-, or multi-dimensional reality.

The same interest in time as split or looped is seen in his 1937 plays Time and the Conways and I Have Been Here Before.

The film version of Dangerous Corner makes some important changes. As you’d expect for a film of the 1930s, the gay plotline and the drug addiction are excised. The character of Charles (Melvyn Douglas) is made more virtuous. He is revealed as the thief, as in the original, but here he has stolen the bonds to help Betty pay off gambling debts. She is no longer his mistress but a friend he is protecting. In addition, Charles is shown pursuing Ann (the play’s Olwen), who turns aside his proposals of marriage. At the end of the film, she agrees to marry him, providing a romantic wrapup.

The first seventeen minutes of the film establish the Charles-Ann courtship and present portions of the play’s backstory. We witness the three men discovering the theft of the bonds, and soon we watch Charles’ discovery of the dead Martin. An inquest declares the death a suicide, and a year passes. Now begins the play’s opening situation, with the women in the parlor. But there’s no longer a radio play running; instead, they’re listening to music before they hear a gunshot. That turns out to be the result of Robert’s firing his pistol into the garden to show it off to Gordon and Charles.

Coming into the drawing room, the men pair up with the woman and banter with their guest, the novelist Maude Mockridge. (She’s in the play as well.) The radio becomes important when Gordon goes to it to tune in some dance music, but the tube fails and, as he puts it, “I guess we’ll have to talk.” From then on the film follows the general contours of the play, and I think it exemplifies the conventions of forking-path plots pretty well. What are those conventions?

Using the correct fork

In the essay I start by suggesting that the action in forking-path plots is understood to be linear. Within each track, there is a smooth progression of cause and effect. Both play and film obey this condition through the simple chronology of scenes, but it’s also controlling the puzzle of the missing bonds, which is eventually explained by detective-story logic. Charles admits to taking them, and in the film Betty further explains that he did it to cover the gambling debts she wouldn’t confess to Gordon.

Linearity is also reinforced by a simple either-or switch. In the film’s tell-all version, Gordon can’t play dance music on the radio because there isn’t a spare tube for the radio set. Then begin the exposures of all the peccadilloes. In the alternate-reality version, there is a spare tube in the drawer, and so the exposures can be averted. Tube there: certain things follow. Tube not there: other things follow. Each chain of events proceeds without break or further splitting.

The radio tube is part of the film’s use of a second principle, what my essay calls signposting. If we’re to understand that there are alternative plotlines, we need some clear markings. In the film, we get several.

First there is the “reset” moment in the second version, when we return to the women moving to the French windows and hearing Robert’s firing of the pistol into the garden. That is a pure replay. What follows reiterates the action we saw earlier: The men joining the women, the radio announcing the time, and the initial chat before the signal fails and Gordon looks for—and this time, finds—a fresh radio tube. He thoughtfully reiterates the split for us. Dancing with Betty, Gordon says: “If Freda hadn’t had that spare radio tube, there wouldn’t have been any dance music, and then—well, anything might have happened.” As I suggest in the essay, characters in forking-path plots often get quite explicit about the what-if premise.

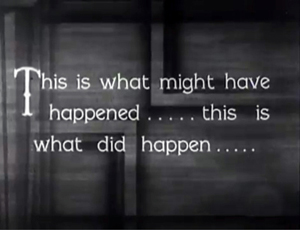

More unusual is the film’s use of intertitles as signposts. Robert, overcome with despair by the results of his relentless demand that everyone confess, runs to his room and shoots himself. The screen goes dark, with traces of smoke. Then we get this title:

At face value, this intertitle says that the stretch of time in which the characters exposed their private lives (the first “This”) is fictitious, while the amicable, truth-concealing version we’re about to see (the second “This”) is veridical.

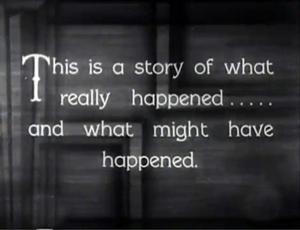

Is this a bit of hand-holding for an audience that wasn’t prepared for the forking-path device? It does have that function, and to our taste it’s probably too explicit signposting. But it’s more interesting than it appears, because it reverses an intertitle that appears in the film’s opening.

Before the action starts, we get this expository title.

Even without knowing how the film will develop, we are invited to imagine a two-part structure. After seeing the whole film, we can see that this puts the dual worlds on the same footing. The phrasing could be suggesting that the cascade of admissions we’ll see is what really happened, while the smooth social veneering of the final scenes was only an alternative possibility. At the climax, we’ll see the second title as a revision of this slightly puzzling one, which now might seem a bit of playful misleading.

But I think this first title is ambiguous in an intriguing way. The film really has three parts. First there are the 1933 events outside the drawing room, involving the robbery and Martin’s apparent suicide; these scenes aren’t in the play. Next block is the first, confessional versions of the 1934 evening. The third part is the alternative, calm version of the 1934 evening. From this angle, the first title is telling us that the 1933 section leading up to the crucial evening is “what really happened,” and that is indeed the case. We don’t get alternative versions of the robbery or Martin’s death. Accordingly, the sordid first iteration of the evening, the film’s second part, becomes “what might have happened.” In a weird way, the title is accurate about the first two chunks of the plot.

In other words, I’m suggesting that the titles fit the film’s structure as follows. The first title is in red, the second in green.

“This is a story of what really happened…”: The 1933 section.

“…and what might have happened.”/“This is what might have happened…”: First, scandalous version of 1934 evening events.

“…this is what did happen.”: Second, banal version of 1934 evening events.

Anyhow, two versions of the evening are quite enough for us. We can imagine more, but in films we never really encounter the radical plurality of multiple worlds. The physics of a true multiverse would offer indefinitely many variants, including ones in which any particular person doesn’t exist. In some worlds, Gordon would be married to Ann, Robert would court Betty, Charles would be a terrier, and so on. But—and here’s my third principle of such storytelling—the usual forking-path plot revisits essentially the same story world with the same characters, relationships, and settings, and most of the same actions. I call it the principle of intersection.

Intersection assures that we don’t get overwhelmed by having to meet a raft of new characters, figure out new settings or time periods, and generally reorient ourselves with each path we’re led down. Forking-path plots, from A Christmas Carol to It’s a Wonderful Life, keep things simple for us by changing very a few features of their rival worlds. Despite Priestley’s belief that each instant of our lives opens up many alternatives, that gigantic exfoliation of actions is very hard to dramatize and even harder for us to keep track of. So in both play and film, we have the same small world, with only a few differences. That works to the plot’s advantage, because those small differences—the radio works/ it doesn’t work, the cigarette box attracts attention/ it doesn’t—can be given enormous importance.

More rules

A fourth principle of forking-path plots involves the use of cohesion devices—elements of story or narration that smoothly link scenes. Cohesion devices are mid-sized examples of Hollywood’s love of continuity on every scale: cause and effect across the whole plot, foreshadowing of a later scene by an earlier one, hooks between sequences, and at the finest grain, shot-to-shot matching. Accordingly, each path in a forking plot ought to lead us along as easily as a normal plot would.

The essay mentions appointments and deadlines as common cohesion tactics. These aren’t very prominent in either the play or the film version of Dangerous Corner, chiefly because the forked action takes place in such a limited time span. But other devices, such as dissolves and fades, help the parts stick together. In the film a flashback dramatizes what Ann says took place on the night of Martin’s death in a way that fits tidily into the overall arc of the plot.

More interesting in the film are the parallels, a common byproduct of forking-path construction. At a macro-level, the two or three or however many paths are sensed as equivalent, variant versions that the viewer is invited to liken or contrast. And both our play and film reiterate the parallels among the couples; the visiting novelist Maude Mockridge says in the film that Charles and Ann should marry and complete the perfect symmetry set up by the “snug” pairings of the two other couples.

In the course of the first night’s exposures, hidden parallels are brought to light. Ann is mutely in love with Robert, who is mutely in love with Betty. Both the Freda-Robert marriage and the Gordon-Betty one are revealed as loveless. In the play, more parallels are piled on: Both Freda and Gordon have Martin for a lover, while Charles keeps Betty as his mistress.

Since parallels invite us to note contrasts, we can see that Phil Rosen (never accorded the status of an auteur) has somewhat altered things during the replay portion of the climax. Some variations in framing mark the second version as different from the first.

Mostly the purpose of the new angles in the replay is to highlight Charles and Ann, preparing us for their romantic alliance on the patio. The first version makes them small and far off-center left; the second emphasizes them much more, with the high angle enlarging and centering their flirtatious encounter.

My two last principles are also borne out in the film version of Dangerous Corner. One says that the last path traced presupposes the others. By that I mean it can take the earlier iterations as already read.

One result is that later versions of events can presented more briefly. When an alternative reality runs through bits we’ve already seen, we don’t need to see the full original version. This happens in the second fork of the film, which takes less than three minutes to get us to the crucial split—when Gordon discovers the fresh radio tube and tunes in the dance music. The first iteration of the evening’s events took almost five minutes to get us to the same point. This may seem a minor difference, but such intervals matter in a movie whose action consumes only sixty-two minutes on the screen.

Moreover, one time-saving passage shows the importance of the first iteration as setting up the situation. In the first version, Maude the novelist inquires about Martin, and she bends over a portrait photo of him.

This shot is less for her than for us, introducing the character whom we’ll see in Ann’s flashback. During the second version, we don’t get the full discussion between Maude and Freda, and we aren’t shown the photo. The narration assumes that after the flashback Martin is vivid enough in our memory. What replaces the insert of Martin is a reverse shot of Freda, describing Martin.

Now that we know she was Martin’s mistress, we’re in a position to appreciate how her dialogue and expressions conceal their relationship.

Similarly, the first version stresses the cigarette box that Ann inadvertently says she recognizes. The second version contents itself with a long shot, because now no one will question her about it.

The sense that the last path we see presumes the others has a more interesting side effect. Sometimes we get the sense that in the last go-round the character is mysteriously aware of the other paths she or he has taken. This happens in Sliding Doors and Run Lola Run, when each heroine seems to have learned from her experiences in the parallel worlds. And multiple-draft films like Groundhog Day and Edge of Tomorrow make this learning process essential to the action. The premise is illogical, but narratives often violate logic.

Something similar happens in the film (but not the play) of Dangerous Corner. Alone with Charles on the patio, Ann accepts his marriage proposal because the cigarette box she saw at Martin’s, now in Freda’s hands, made her realize she’s “been a fool.” We have seen the flashback in which she fought off Martin and accidentally killed him. The flashback isn’t in the play, and it’s especially interesting because presumably that scene really did take place, in both paths. That is, the evening orgy of confessions is one hypothetical alternative, but the manner of Martin’s death a year before, revealed in this path, is an actual event. It’s as if reliving Martin’s attack during the first path has made Ann appreciate Charles’s genuine love for her.

My seventh principle also bears on the last path we encounter. It’s a simple one: We take the final path as the correct one. Since endings are typically the place where all is revealed, we’re prepared to accept the last reiteration as what really happened. (This can be reinforced by a character’s learning curve, such as Ann’s.) Dangerous Corner is a good example.

I think we’re urged, by the second intertitle but also by the overall arrangement of the parts, to see that the quiet maintenance of civility predominated during that evening. The more sordid alternative, though given at much greater length, is what’s under the surface but what will never be acknowledged. The truth of the theft and Martin’s death, along with all the love affairs and animosities spilled out in the first version, will never be brought to light.

Other factors give the second version more weight. There are the shots I mentioned that stress the Ann-Charles relationship more, but for me the clinchers are more structural than stylistic. For one thing, both Ann and Charles play the role of raisonneur–the character(s) who explains the action and articulates central themes of the piece. In both the first path and the second, Ann echoes Priestley’s notion of our limited knowledge, saying that we prefer half-truths to the complete, factual account, the one that only God knows. And in both paths Charles warns against telling the truth, as it presents a “dangerous corner” that could lead to a smash-up. No other characters reflect so fully on the consequences of letting everything out.

Another structural factor involves the film’s beginning and the ending. The 1933 section starts with a scene in which Charles calls on Ann and once more asks him to marry her. Thanks to the primacy effect, this pair of characters becomes more salient in what follows than the married couples do. As a result, the epilogue, set on a terrace like the first one, harks back to the indubitably actual, pre-fork opening.

The fact that the movie ends with the creation of a couple, the uniting of the two characters who are the most self-aware and sympathetic throughout the film, reinforces the sense that this is the “real” outcome.

I hope you’ll read the whole essay. My purpose is to understand the dynamics of a small but increasingly common body of films. Forking-path films ask us to construct stories in unusual ways, but we quickly learn what guidelines to follow. Once the format exists, filmmakers take up the challenge of mastering it, stretching it, applying it to new material. (Edge of Tomorrow was sometimes considered Groundhog Day Goes to War against Aliens.) As filmmaking practice develops, we can track contemporary experiments and relate them to earlier efforts they are based on.

In addition, it’s worth knowing that a fairly sophisticated filmic treatment of the format appeared eighty years ago. In the essay, I find even earlier examples. And in a period when every movie seems at least 130 minutes long, it’s nice to encounter one that offers so much narrative complexity in about half that running time.

More generally, I think that probing this body of film shows the value of systematically studying narrative formats of any type. We’re used to talking about genre as a fluctuating body of conventions, but we should also study conventions that cross genres—conventions of story worlds, plot structure, and narration. These conventions can prod us to execute some unusual mental moves. Filmmakers are practical psychologists, and they’ve learned how to tease and tickle our minds. What-if movies are just one example of how norms and forms guide our understanding of story.

My first quotation from Priestley comes from Three Plays and a Preface (Harper and Brothers, 1935), ix. The second comes from Two Time Plays (Heinemann, 1937), ix.

In production, Dangerous Corner seems initially to have replaced Priestley’s what-if premise with more of a whodunit plot, while incorporating subjective sequences. According to a Variety review of an 83-minute cut before release, the explanations offered for Martin’s death by the various men are followed by something fairly unusual.

Surprise and twist, with increasing suspense, are accomplished through a shift from the factual elements to subjective processes on the part of the three women most closely related–as wives or sweethearts–with the suspected men. An innocent revolver shot precipitates the terrific speculations as each woman wonders if her man has killed himself in an adjoining room (Daily Variety, 13 September 1934, p. 3).

By the final release, however, the film had lost twenty minutes, and the result was the version we have. I haven’t seen versions of the screenplay, but I bet they’d be interesting. We’re left with other what-if questions, this time about the production of the movie itself.

Some of the basic concepts I employ here and in “Film Futures” are explained in the essay “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative,” online here. That essay is in turn applied to The Wolf of Wall Street in this blog entry.

Dangerous Corner (1934).

Here be dragons, and tigers

Revivre.

DB here:

My first visit to the Vancouver International Film Festival back in 2005 was at the invitation of Tony Rayns, programmer of the Dragons and Tigers series. That series included both new films by established directors and a batch of first or second features by beginners. Tony asked me to be on the jury for the young D & T award.

I enjoyed working on that jury, which consisted of old friend Li Cheuk-to of the Hong Kong Film Festival and new friend Gerwin Tamsma of the Rotterdam fest. We gave the prize to Liu Jialin’s Oxhide, and it’s been gratifying to track her career since. In the course of my stay I realized what an excellent festival Vancouver had, not least because of the warmth and enthusiasm of its staff.

My Vancouver experience helped launch this blog, which really got under way during my second visit, in several entries in 2006. That was also the year I met Bong Joon-ho, who was at VIFF with The Host. I kept going back, and Kristin began joining me, so every year we’ve been writing about this admirable event.

During that 2006 festival Tony decided to rearrange his commitment to Dragons and Tigers. He turned the curating of Chinese-language films over to expert programmer Shelly Kraicer, who was living on the mainland and had excellent contacts within China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Now things have changed again. This year the festival accepted fewer beginners’ features and folded them into a broader international competition. One of the Asian films in the collection, Rekorder by Mikhail Red, tied with a French entry, Miss and the Doctors, for the award. In the old days, the winner received a cash prize; alas, that benefit has not been retained, but maybe some far-sighted patron will step forward to give the award a little more heft.

There were fewer D & T titles overall this year, but I still found several of great interest. Herewith some notes on them.

Time, and time again

Revivre.

If your movie is going to include flashbacks, you have a choice among several standard ways of motivating them. You can use the very old device of presenting an investigation or trial, in which the film translates testimony into dramatized scenes. Or you might frame the flashbacks with a scene of a character who thinks back on events in the past. Three of the Dragons and Tigers films used some other common flashback setups, but treated them in fresh ways.

Im Kwon-taek’s Revivre (Hwajang, his 102nd film!) starts with another canonical flashback situation. In fairly washed-out footage a funeral procession crosses the screen. A man at the head of the group looks back and sees a beautiful young woman looking gravely at him. Immediately the film triggers questions: Whose funeral is this? Why is the young woman important?

The rest of the film fills us in via flashbacks,. The protagonist, Oh Sang-moo, is a manager of the advertising section of a cosmetics company. His wife is stricken with a brain tumor and he cares for her as best he can during her years of surgery and recovery. At the same time, he develops a restrained affection for Ms. Choo, an employee in his division. Eventually Oh’s wife dies and there is the lingering possibility of his starting his life afresh with Ms. Choo, whose phantom face we’ve seen in the procession. Threaded through this are the pressures of a business deadline, his need to keep his staff on track, his occasionally fraught relations with his daughter, and his wife’s adamant insistence that after she dies he keep none of her things, not even her beloved dog.

The film scrambles the order of Oh’s experiences. After the funeral, within about five minutes we get a scene of Oh’s wife dying in the hospital, then a scene of his own medical problems, and then the moment that Oh’s wife collapsed in the garden, yielding the first sign of a tumor. The rest of the film gives us incidents from all phases of their last years together, with emphasis on his careful attention to her bodily functions. Although his daughter finds the task repellent, Oh changes his wife’s diapers and cleans her private parts with the same calm professionalism that he brings to the meetings in his company. In all, the non-chronological flashbacks work effectively to show Oh juggling the pressures of business with the demands of his family situation.

What makes Im’s treatment a little unusual is that the flashbacks aren’t presented as Oh’s memories. They are rearranged by the narrational authority of the film itself, rather than by situations that provoke Oh to recall this or that incident. We’re restricted to Oh’s range of knowledge throughout, but that doesn’t draw us closer to him. We have to read his mind through his expressions and his gestures, and these are often severely controlled. A master of the poker face, this executive keeps a polite distance from everyone, including the viewer. Is he one of nature’s stoics? Or is he emotionally detached, attending to his dying wife more out of duty than love?

These questions are partly answered by some brief fantasy scenes in which Oh visualizes Ms. Choo as a romantic partner. She seems to intuit his interest, and responds through small signals. When she starts to reciprocate more explicitly, Revivre returns to its mood of impassive sadness for its final scenes.

Time and freedom

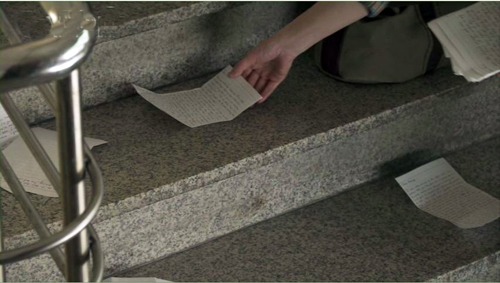

Hong Sangsoo has been playing with time from the start of his career. He has tried replays from different viewpoints (The Power of Kangwon Province, 1998), replays that differ in details (The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, 2000), odd déjà-vu experiences (Turning Gate, 2002), and all manner of theme-and-variations plotting (as noted on this blog here and here and here). So it’s a bit surprising to find him exhuming the old reliable setup of letters recounting events in the past. Yet here as ever he has a couple of tricks up his sleeve.

Like Im, Hong has scrambled the flashbacks in Hill of Freedom, but he offers a comically exact motivation. Kwon, a young language teacher in Seoul, returns to find a sheaf of letters written to her by a Japanese admirer, Mori. He taught with her at the school two years earlier. He has come to Seoul to reunite with her, and he has left her a letter every day. She starts to read them in the school lobby, and Mori’s voice-over narration establishes the beginning of his story. He tells how he found lodging, left a note at Kwon’s apartment, and paid his first visit to the “Hill of Freedom” café.

So far, 1-2-3 preparation. But when Kwon starts to leave the language institute, she staggers on the staircase, as if stricken, and scatters the letters on the steps. She gathers them back up in random order. This sets up the scrambled timeline of the flashbacks to come. (Hong mischievously zooms in on a letter she fails to retrieve, hinting at a gap in the story that will follow.)

What Kwon learns, in mixed-up order, is that Mori’s search for her leads him to meet and hang out with his landlady’s nephew, while also becoming romantically involved with Youngsun, the café owner. In the grip of a possessive lover, Youngsun attaches herself to the fairly passive Mori. Their affair plays out in Hong’s usual mix of drinking bouts and pillow talk.

By the time we’re used to this pattern, Hong sets up a new game. As he keeps cutting back to Kwon reading through the letters, accompanied by Mori’s voice-over, Hong gradually reveals that she is reading them in the Hill of Freedom café—the very place Mori hoped to meet with her (but never did).

Eventually, Kwon steps outside for a cigarette, and we suddenly get her voice-over remarking that the last letter was postmarked a week ago. Has Mori then already left and stopped writing? At this point Kwon encounters Youngsun coming in, and they greet each other as friendly acquaintances. The next scene finds Kwon visiting Mori’s guest house.

What happens there shifts the ground under our feet. After talking with friends, I think that we can’t be sure about what’s actually taking place. A mysteriously bruised cheek, a surprise reunion, and the return of Mori’s voice-over fill the penultimate scene. The coda is even more of a puzzler, at least to me. (I wonder if it’s the scene described in the letter that Kwon didn’t retrieve.) In any event, Hong’s usual themes of the foolish arrogance of Korean men and the comedy of male-female interactions are given new expression in this lightweight but enjoyable movie. The fact that Hill of Freedom is mostly in English, which Mori must employ to communicate with the Korean characters, adds to the fun.

Video virus

Yet another trigger for a flashback can be provided by a crisis situation. It might be rather near the story’s climax, so that we are left hanging and the plot takes us back to the origins of the problem. This is what we get in movies like The Big Clock (1947), which starts with our hero hiding out from the police and wondering how he got in this pickle. Or the crisis situation may come earlier in the story, with the flashback again filling in what led up to it before continuing the situation presented in the frame.

This latter option is followed in Mikhail Red’s Rekorder. After a brief prologue showing violent acts captured by CCTV cameras, we are in a police van with stern cops chatting about killing a dog before we’re introduced to the shaggy, wasted protagonist Maven riding with them.

From this framing situation we flash back to the reason Maven is in the van. Once a cinematographer in the glory days of Filipino cinema, he’s now a loner using his ancient camcorder to film movies in theatres and sell them to a friend who bootlegs DVDs.

Maven is a compulsive recorder. As the director puts it, he is “a ghost in the city observing everything through his lens.” So naturally he’s filming when a street gang kills a young man in front of a crowd who simply watch. Maven doesn’t volunteer his footage, since it includes part of a movie he was pirating. But now he’s been nabbed and is riding to headquarters with the cops, who are very curious about what’s on his tape.

Much of the rest of the film involves Maven’s attempt to keep the cops from examining his footage, while he agonizes about his passive acceptance of street violence. There are still more flashbacks, appropriately presented through old video footage of his wife and daughter. Not until the end of the film do we witness–again, on CCTV footage–the trauma that has turned him into the burnt-out case he is.

Mikhail Red commented that he was inspired to make Rekorder by a viral video in which a youth was shot in the street by thugs and a big crowd didn’t intervene but instead filmed the murder. He staged his own CCTV-style video to supply the denouement, and was shocked to find that it was appropriated in documentaries about street crime. Through a multimedia format, Rekorder updates the sort of social criticism that Raymond Red, Mikhail’s father, brought to Filipino cinema of the 1980s. That era as well is evoked through another sort of flashback, the clips from classic movies that Maven films. “I wanted,” Red says, “to pay homage to the pioneers.”

Straight time

You don’t need to play time tricks to create an uneasy movie. Ow (Maru) presents a typical family squeezed by Japan’s economic stagnation. Dad pretends to have a job, when he actually sets out each day for the unemployment office. Mom and grandma putter about. Grown but spacy Tetsuo lounges about his room talking baby talk. One day, when his girlfriend has just snuggled into bed with him, they are transfixed by a big gray-brown sphere that drifts into his room.

Transfixed, literally. They freeze upon seeing it. So does Dad, and so do the cops who are called. Director Suzuki Yohei introduces us to the big ball with a shot of it slowly spinning, held long enough for us to get slightly hypnotized too. There follows some comic suspense in which people enter the bedroom and may or may not leave. The biggest tease is the reporter who, after learning of a death during the sphere’s arrival, researches the case and then lunges into the room, ranting about a police cover-up.

The tension–will others fall under the spell or the sphere?–is accentuated by shrewd camera setups. When the cops arrive, we get a low-angle shot behind Yuriko and Tetso, showing the frozen cops and a new one not yet transfixed. He pushes one stiff colleague over, revealing the ball, still hovering there, and we wait for him to be the new victim.

Much later, when the reporter first visits the room, the sphere has vanished. But a rhyming angle forces us to remember its presence, and to let the reporter–the source of the plot’s momentum for the rest of the movie–take the place of the hapless cop.

Finally, for another exercise in unkinked time, there is the Korean action picture Haemoo. Produced by Bong Joonho, it centers on the desperate captain of a fish-trawler who agrees to bring illegal immigrants into Korea. Everything that could go wrong does: storm, fog, Coast Guard patrols, a horny crew, and an idealistic novice seaman who tries to protect a woman. Everything, including the accident that creates a horrifying midway turning-point, is carefully prepared in the film’s opening scenes. The film’s second half locks us into the relentless consequences of covering up a huge crime.

The pace is so snappy that I expected lots of cutting, but I counted only about eight hundred shots in 106 minutes. (The Equalizer, only twenty minutes longer, has three times that number.) I attribute this cutting rate to neatly functional direction, with no fuss or waste. The ship’s engine room is a cramped set, hazy with steam and dust, and the shots there are finely calibrated to build the drama through depth, fluid camera movement, and our old friend The Cross. The randy engineer’s business of checking the equipment carries him from one side of the shot to the other, while the young seaman shifts around him–first on frame right, then on frame left, then in the center.

The plot has that satisfying neatness that is characteristic of Bong’s work, and its forward thrust has no need of flashbacks. We can’t ask for backstory when the upcoming twists are as fast-paced and exciting as they are here. Dragons and Tigers has always showcased not only the experimental films like Ow and Hill of Freedom but also the crowd-pleasers, and Haemoo (which translates as “Sea Fog”) solidly fulfills that mission. Long live linearity!

Hill of Freedom has sharply divided critical opinion. Richard Brody considers it a masterpiece; others consider it fluff. At Fandor David Hudson painstakingly surveys the cut and thrust of the controversy.

Hill of Freedom.

Cinematic storytelling: A podcast on narrative

The Wolf of Wall Street (2013).

DB here:

Michael Neelsen is a filmmaker and consultant based here in Madison. In a discussion on ReelFanatics Michael and I consider some ideas about cinematic storytelling. My allergies gave me some Clintonesque hoarseness, and there are some things I’d rephrase better if I were writing them down, but maybe you’ll find something of interest there.

A couple of blog entries are relevant to our conversation: one on The Wolf of Wall Street and another on American Hustle. The first of these links to a general analysis of film narrative originally published in Poetics of Cinema and available elsewhere on the site. Our discussion of suspense and surprise harks back to other entries too, in particular those about Hitchcock and the bomb under the table (here and here). In the podcast I mention the Godard film Adieu au langage as well because I was then working on this blog entry.

You can also visit Michael’s company site StoryFirst.

Thanks to Michael for an enjoyable discussion, and for sharing it via podcast.