Archive for the 'Directors: Hong Sangsoo' Category

Where did the two-shot go? Here.

Our Sunhi (Hong Sangsoo, 2013).

DB here:

I’ve complained here and there about the rudimentary staging of scenes in mainstream American movies. (Short version of common practice: Cut a lot and move the camera instead of moving the actors.) But just as rare as complex staging, in the age of intensified continuity cutting, is the sustained and stable two-shot.

Two actors exchanging lines in a continuous, unmoving take was one building block of mature sound cinema. Today’s directors almost never resort to it. Their face-offs are “given energy” by a drifting or arcing camera, or lots of cuts, or, if they feel like moving the actors around, the Steadicam walk-and-talk.

But the prolonged, balanced two-shot can yield remarkable results. A medium-shot or medium-long-shot framing can work to a human dimension, giving prominence to the actors’ bodies. It doesn’t let their surroundings swamp them, and it doesn’t reduce them merely to faces. It lets the actors act with not just facial expression but with their posture and their upper bodies. And it nicely balances dialogue with the flow of pictorial information. We can watch both actors, with one reacting to the other, as in The Marrying Kind (1951).

Sometimes the two-shot is played with the faces in profile, as in early sound pictures like The Criminal Code (1931).

But directors quickly understood that if you prefer, you can angle the actors so that we get a 3/4 view of one or both. The tactic sacrifices realism (who stands in such ways in real life?) but it’s a piece of artifice we gladly accept. It’s visible in my Marrying Kind example, as well as here in Two Weeks Notice (2002).

Of course two-shots are still with us, but they usually serve to set up passages of shot/ reverse-shot cutting. The sustained two-shot carrying long stretches of dialogue is increasingly rare in Hollywood cinema. It surfaces more often, I think, in indie works (Jarmusch, Linklater, and Hartley, for instance), European films (Garrel, for instance), and perhaps most notably some Asian films.

For reasons not yet well understood, during the 1980s stylistically ambitious directors in Japan, Taiwan, and China began building scenes out of long, static takes. Sometimes those are distant framings, unfolding in elaborate blocking; to my mind Hou Hsiao-hsien is the great master of this. But no less prominent are those films that present simply staged shots of two or more characters in which action and reaction are captured by a fixed camera. Often these shots avoid 3/4 views. That is, we may get two characters in profile, or two characters facing the camera directly. The result is a more abstract, even ceremonial look and feel.

I was remembering this tendency while watching several of the films on display here at the Vancouver International Film Festival. I saw one film very largely made of two-shots. I saw a couple in which the two-shots serve mostly as points of punctuation, breathing space between scenes that are cut up in more orthodox ways. And I saw one film that climaxed in a two-shot showing the actors holding their ground for about fourteen minutes. All were from Asia.

Both visual and plot-based information follows; in other words, as often happens hereabouts, there are spoilers.

The Return of Kids Return

Kids Return: The Reunion, directed by Shimizu Hiroshi, is a sequel to Kitano Takeshi’s 1996 film. The disaffected high-school buddies Shinji and Masaru were last seen riding a bike and declaring that they would show the world what they’ve got. Now, many years later, they haven’t shown much. Masaru is a low-level gangster who has lost the use of his left arm in a jailhouse brawl. Shinji holds a boring job as a security guard, and he’s about to give up boxing. The two meet by accident and resume a more distant version of their friendship. Masaru gets more deeply embroiled in the yakuza world, but he does convince Shinji to stick with prizefighting. As Shinji struggles to improve his skill, Masaru sets out to avenge his betrayed boss, with murderous results.

The new version doesn’t have the dry, laconic quality of Kids Return, and the film doesn’t employ Kitano’s characteristic planimetric framing and compass-point editing. But the incessant over-the-shoulder framings of most movies are avoided; when we cut to a character, he or she is usually isolated in the frame. And some moments recall the cartoon-panel cutting of Kitano. One scene shifts from the yakuza boss, Masaru, and the thug Yuji in a coffee shop to a soundless shot of their young subordinate at the office simply staring off into space. Cut to the three men strolling back to the office, with Yuji commenting that the kid never keeps the sidewalk clean.

A pan following the men into their building shows the office open and men inside. Yuji bolts past his boss and flings himself at a policeman, who is one of several ransacking the place for evidence.

Most directors wouldn’t include the enigmatic shot of the functionary, but it yields a little question–what is he reacting to?–that the next shots gradually answer.

So cutting plays an important part in building up many scenes. But occasionally Shimizu pauses to draw a moment out. When Murasu and Shinji meet after many years, a nearly thirty-second shot squares them off.

Instead of embracing and pounding each other’s back in the American fashion, they stand awkwardly opposite each other, and the anamorphic widescreen image stresses the tentativeness of their reunion. Later, when Murasu’s boss suggests he leave town and work for another boss, a poised two-shot (at the top of this section) lets us watch the interplay between them across two minutes. Again, the ‘Scope ratio helps, and the fixed frame adds a comic touch by setting at frame center the hideous, ticking clock that Yuji has bought the boss.

I don’t want to suggest that there’s anything particularly radical about Shimizu’s two-shots. Kids Return: The Reunion simply reminds us that a two-shot can usefully vary the film’s pace and lend gravity to moments of character reflection.

Absurdist anatomy

Something stranger goes on in Anatomy of a Paperclip, the winner of the Dragons and Tigers Award here at VIFF. The story is an exercise in grotesque nonsense, a sort of Japanese Theatre of the Absurd.

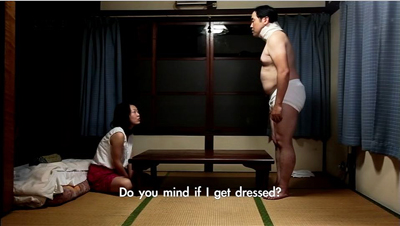

In an undefined town outside time (no cars, videos, or cellphones), a harsh boss rules over a crude cottage industry. Three, sometimes four, workers sit along a bench and make paper clips by snipping and twisting wire. The most hapless is Kogure, a lumpish loser wearing a neck brace. Bullied by two outlaws who constantly make him surrender his money and take off his clothes, eating with painstaking regularity in the same cheap restaurant, he returns home every night to sleep. A butterfly visits him and apparently leaves a pupa behind. As Kogure trudges through his days of petty humiliations, the pupa swells to human size, even bigger than the pods in Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

Director Ikeda Akira shot the film in fifteen days over weekends and holidays. It’s partly in the planimetric mode, with the camera lined up perpendicular to a back wall or lines in the setting.

Even more than Kids Return, the mug-shot and police-lineup staging recall linear, minimalist manga. A great deal of the film’s feel, that of a frozen, almost robotic world, derives from this deliberately “flat” look.

In Anatomy of a Paperclip, the profiled two-shot functions as part of the overall visual pattern. Although some conversations show 3/4 views of the characters, and even yield occasional OTS (over-the-shoulder) framings, many two-shots preserve the geometrical right angles of the master shots.

Another function of our two-shot, then: To play its part in a film’s overall pictorial design, suggesting expressive qualities like rigidity, automatism, and deadpan humor.

Two’s company, four’s a crowd

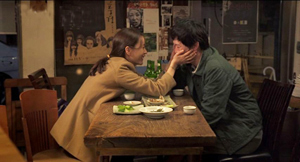

Hong Sangsoo has made the two-shot–usually profiled and showing characters drinking heavily at a restaurant table–into a central formal device. His films are conversation-driven, and he has rung an ingenious series of variations on duologues. They are typically presented in ways that stress similarities and contrasts among characters, often to mildly satiric effect. We see A and B in one setting, then perhaps B and C in another setting, then A and C in the first setting, and so on. For examples, see this entry.

In the more formally complex Hong films, these variants may be played out as intermingled points of view (The Power of Kangwon Province) or as alternative versions of the same events (The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors) or just weird déja-vu (Turning Gate). In an earlier entry, I suggested that Hong exploits our inability to remember certain things precisely, so that we may forget when we first heard a recurring line of dialogue or saw a shot that is echoed by the shot we’re now seeing.

Our Sunhi is about a hugely momentous event that hasn’t, to my knowledge, been dramatized on film before: a professor writing a grad-school recommendation. Sunhi approaches Professor Choi for a reference that will help her study in the States. As she coaxes him into revising his initially cool letter, he becomes attracted to her, as does another university employee Jaehak. Meanwhile Sunhi meets her old lover Munsu, and he becomes attracted to her all over again.

Here the formal rondelay that mocks male vanity–a Hong specialty–doesn’t involve fancy tricks with time or parallel viewpoints.Instead, what circulates are comments about Sunhi, pulled from the professor’s letter (“She has artistic sense,” “She’s honest and brave”) and passed from man to man. The points of circulation come in eleven duologues, each shot in one or two symmetrical long takes. Sunhi meets Jaehak, then Choi, then Jaehak again, then Munsu. Soon Munsu is going out drinking with Jaehak, with whom the prof has coffee before having a rendezvous with Sunhi. Connecting these nodal scenes are brief shots of characters walking through streets, meeting one another by accident, and at the finale, converging in a palace park. As you’d expect, these connecting bits are typically made parallel to each other through framing, situation, music, or other devices.

The two-shots are very long; the longest runs over eleven minutes. It presents a sort of climax, in which a drunken Sunhi reaches out to clutch Jaehak–a gesture of greater intimacy than she has shown any other man.

But soon enough she is meeting the professor for a date in the park. In the very last scene, when she goes off to the toilet, Hong gives us a tiny joke. All three of the men finally meet, waiting for her, and at last a two-shot becomes a three-shot.

This sheerly formal gag is pretty esoteric, I grant you, but it’s typical of Hong’s urge to tweak the simplest materials. In his hands, the lowly two-shot becomes a structuring constraint, a way of deliberately limiting his choices to show us what he can do with it–not least, comic variation.

Two heads, better than one?

During the 1940s, directors in various countries began to rethink the layout of their two-shots. Instead of giving us matching profiled or 3/4 views, they began to arrange their players so that one figure was significantly closer to the camera, yielding what I’ve called a big-foreground composition. In America, the most flamboyant early versions came from Orson Welles (Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons) and William Wyler (The Little Foxes, below). This strategy encouraged staging in depth and even letting players turn their backs to one another.

Tsai Ming-liang’s Stray Dogs is the most elliptical and visually variegated film of this VIFF bunch. It’s less a story than a situation: A father, mother, and two children try to survive on the streets. The father picks up odd jobs, while the mother finds work in a supermarket. They wash in public restrooms and scrounge castoff food, sometimes thanks to the mother’s rescuing market goods past their sell-by date. At night, the father and the kids huddle in a makeshift hut, until the mother finds a somewhat better squat in a ruined office building.

Every scene except one consists of a single take, but the connections between scenes are far more oblique than in the other films in this entry. For instance, the mother is seen weeping beside her sleeping children in the opening shot, but then she vanishes from the plot for a while before reappearing in the supermarket, now with her hair cut shorter. The clear and continuous duration of the scenes is offset by a narrative organization that skips over a lot of time and refuses to explain everything that happens in the interim.

Tsai’s visual strategies are quite diverse. Unlike Hong Sangsoo and others in this trend, he doesn’t always keep his camera within a mid-range zone. A scene’s single take can be a striking extreme long-shot or a tight close-up, often of the father (played by the still remarkably waif-like Lee kang-sheng) eating, drinking, or just reciting a poem.

Stray Dogs makes little use of two-shots, and his “clothesline” layouts aren’t quite as frieze-like as those in Anatomy of a Paper Clip.

He saves his devastating two-shot for what is, in this quiet and melancholy drama, as close as we get to an intimate climax. The image at the top of this section shows the husband and wife, her face looming in the foreground while he stands behind her.

Why is this shot, only three minutes longer than one in Our Sunhi, so fiercely hard to take? Hong Sangsoo fills his restaurant shot with gab and plot development. Tsai’s shot, reminiscent of the big-foreground compositions of Welles and Wyler and many afterward, is almost completely unchanging. Neither husband nor wife speaks for fourteen minutes; the only action we see in most of the shot consists of him occasionally swigging alcohol from the bottles he’s stolen and some tears running down her cheek. And we have no idea of when the shot will end because there’s no obvious trajectory set up for it. Like the fixed close-up of a weeping face that ends Tsai’s Vive l’amour, this shot could go on forever.

About thirteen minutes in, the husband grasps his wife’s shoulders and leans his head wearily against her neck.

In a context scoured of what we normally think of as drama, such tiny movements become major events. The father seems at once apologizing for his drinking and trying for a reconciliation.

Tsai has reserved his two-shot for his climax. Instead of becoming a resource judiciously salted through the film (Kids Return: The Reunion) or a stylized extension of a cartoonish world (Anatomy of a Paper Clip) or a core schema for the film’s visual design (Our Sunhi), the two-shot here, rendered as an aggressive image of faces close to the camera, becomes the marker of a mysterious turning point in two lives.

All the films are very much worth seeing for their own reasons. Treating them together, though, reminded me of the power lurking within one very basic cinematic resource.

Last year I considered long-take shooting and staging techniques in that edition of Dragons and Tigers, with comments on Tsai Ming-liang’s Walker.

Just in case this occurred to you: No, Wes Anderson didn’t invent these techniques. This entry and some others explain.

For more on varieties of staging, see On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. On this site, you can visit the supplement to Figures here, and the categories Film Technique: Staging and Tableau Staging.

Stray Dogs.

Memories are unmade by this

Romance Joe (2011).

DB here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival always provides a host of intriguing experiments with narrative form. This year the Dragons and Tigers series, devoted as usual to new films from Asia, offers such a neat pairing of a veteran director and a newcomer that I can’t resist spending some time on them. Both, it turns out, are interested in memory–not just as a theme, but rather as a process involved in how we watch movies.

Passion for pattern

When we analyze a film, we usually notice patterns—an arc of character development, repeated imagery or musical motifs, recurring framings or lines of dialogue. Filmmakers use these elements of patterning to give elements special significance.

Sometimes the patterns we pick out are noticeable on our first viewing of a movie. Indeed, the film’s effect relies on our seeing later elements as completing a pattern.

Remember “You complete me” from Jerry Maguire? The reason you do, I think, is partly because its first appearance is very salient. It occurs when Jerry and Dorothy are riding in an elevator with a mute couple. Dorothy’s explanation of the couple’s signing highlights it (while characterizing her as a sympathetic person who learned ASL to communicate with a relative). When Jerry restates it in Dorothy’s living room, we recall that it’s a simple declaration of love—a straightforward statement from a man who is habitually slick and evasive. The fact that the phrase stuck in Jerry’s mind from the elevator encounter also offers further proof that he’s not as superficial as he seems. He remembered it, and now we do too.

Sometimes, though, we may find patterns that a viewer may not have noticed on first pass. That’s one of the appeals of doing analysis. As we get to know the film more intimately, we see patterns of coherence that probably many viewers didn’t notice before. In classically made films, for instance, a scene is likely to start with a long shot, proceed to two-shots or over-the-shoulder framings, and then toward tighter close-ups. This stylistic patterning follows the rising drama of the scene’s action. Most viewers probably don’t notice these patterns, but directors, cinematographers, editors, and film students are more likely to catch them. When we analyze a film’s style, we may be surprised to find how often these “hidden” patterns emerge.

Very occasionally a filmmaker gives us something in between obvious patterns and buried ones. A film might repeat something in such a way that (a) you recognize it as a repetition on first pass but (b) you can’t recall exactly what it harks back to. In other words, the filmmaker deliberately organized the movie so that the things that come back are difficult to place in the film as a whole.

The best-known example is perhaps Last Year at Marienbad, where the drifting, dreamlike succession of scenes doesn’t supply standard plot progression. The result is that the images, music, and lines of dialogue are felt as echoes of earlier scenes, but most viewers can’t pinpoint exactly where they first appeared. Another instance would be Buñuel’s Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. Here we get scenes that start more or less realistically, and then devolve into absurdity—at which point one of the people in the scene bolts awake in bed. What we’ve just seen is a dream, but we can’t be sure exactly when the dream started because Buñuel and screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière didn’t supply a scene that shows the character going to bed. One effect is that the movie seems like a daisy-chain of overlapping dreams, with no sure point at which we can declare that this or that moment is real.

Both Marienbad and Discreet Charm rely on a fact of cinema: It unrolls in time. So do novels, of course, in the act of reading anyhow. But when you’re reading a book you can stop and page back to check where you went off-track. Since the arrival of videotape viewing, we can in principle do the same thing, and we’d want to replay moments if we’re undertaking an analysis. But the normal conditions of viewing, in both theatres and at consumer command, bias us toward forward momentum. Intent on what happens next, we have a surprisingly hazy recall of what preceded the scene we’re watching now. Halfway through a movie, try to come up with an accurate scene-by-scene list of what you’ve just watched.

The diffuse memory we have of the prior action, and the difficulty of going back to check, is one reason that films need some explicit patterning, their marked repetitions, their constant restatement of the story’s premises. Redundancy of information compensates for the time-bound nature of viewing. Films that don’t supply this, as in my recent example of Sueño y silencio, demand a second viewing—and risk frustrating audiences.

In another country, at other times

Hong Sang-soo has long been a master of the half-hidden pattern. Each film, usually devoted to the comic deflation of male pretension, is built on a unique armature of repetitions. Most critical commentary simply ignores those, trying to summarize the plots straightforwardly and taking the result as comments on contemporary life—an urban milieu in which intellectuals eat, drink too much, smoke endless cigarettes, and make clumsy attempts at romance and sex. “People tell me that I make films about reality,” Hong remarks. “They’re wrong. I make films based on structures that I have thought up.” It’s the structures, I think, that engage us, and partly by asking us to test our memories of what we saw only an hour or less before.

For instance, The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (2000) at first seems a straightforward he-said/ she-said plot. Initally, scenes showing us a love affair’s progress are organized around one character. Then the affair is replayed, but centering on another character. Many scenes show us each character apart, but when they’re together, that scene gets repeated in the second character’s story. The problem is that some significant details are different in the two versions. We’re asked to wonder whether we’re getting the same story as each character remembers it, or two alternative universes in which the stories differ slightly. Moreover, it’s not easy to recall whether this or that prop or line of dialogue was precisely the same in the first presentation. The strain on our memory is part of the film’s fascination.

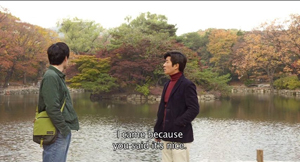

Hong has been a regular in the Dragons and Tigers sidebar over the years. He’s reliably prolific: two of his best films, both made in 2010, were in that year’s program. This year brought us another Hong brain-teaser and funnybone-tickler, In Another Country. It’s a measure of Hong’s growing international reputation that Isabelle Huppert is recruited to play three roles in another mazelike plot.

Yonju, staying with her mother in a coastal hotel and beset by family problems, tries writing film scripts. In the first, Anne, a French filmmaker, is vacationing with a South Korean director and his pregnant wife. As Anne gets involved with a hunky, good-natured lifeguard, the director is also making a play for her. Cut back to Yonju, trying another draft. In this one, Anne is a rich housewife from Seoul having an affair with a married man—again a director, but played by a different actor. As she waits for him to join her at the hotel, she meets the same lifeguard and romantic complications ensue. Back to Yonju trying another draft. Now Anne is accompanied by another woman, an older professor. They meet the first director, pregnant wife again in tow, while Anne has become preoccupied with getting life advice from a monk. Once more, needless to say, the lifeguard plays a central role.

As you’d expect with a multiple-draft narrative, the changes are accompanied by some constants—an evening barbeque, the lifeguard emerging from the sea, an encounter between him and Anne in his tent. There are even repeated ellipses, bits that are skipped over in each mini-story. For instance, in all three drafts Yonju, acting as hostess, starts to take Anne on a shopping trip and promises to show her something interesting. But then we cut to Anne alone, wandering through town. Why did the women separate? Is this Anne on a different occasion?

Most to the point of memory tricks, we’ll see something in a late scene that may result from something we saw in an earlier draft. When a bottle of liquor breaks on the beach late in the film, you might remember that a previous scene showed the bottle there already broken—but which scene, in what point, in what story? It’s as if Yonju’s different versions have contaminated one another, with scenes from one draft taken for granted in a different version. In the third draft, what Yonju promised was so interesting seems to be the lighthouse. We may forget that in the earlier versions, we never knew why Anne was searching for the lighthouse. Still, we’re unlikely to forget the parallel framings.

This sort of play with our memory can bring the movie to a satisfying, if enigmatic, conclusion. An umbrella, a casual and forgettable prop in one version, provides a kind of minuscule climax in the last. And the final shot of Anne walking into the distance becomes a variant of the film’s first one.

In Another Country provides plenty of social comedy. Hong’s customary satire of Korean males’ awkward sexual aggressiveness is now accompanied by digs at westerners’ search for mystic Asian enlightenment. But the narrative structure is amusing in itself. Hong cajoles us into enjoying the surprising but inevitable recycling of situations, lines, and camera setups. Few filmmakers can make audiences laugh at the mere appearance of a shot and tease us to expect a replay of or departure from what we’ve already seen. Even if we couldn’t say precisely when we saw that image before, we recognize it and participate in a light-hearted game—the game of form.

Wristcutters share their stories

Romance Joe (2011) was made by Lee Kwangkuk, Hong Sangsoo’s assistant director on many projects. No surprise, then, that his debut relies on parallels and variants. Yet it’s much more explicitly about storytelling than In Another Country. Hong uses Yonju’s script drafts as a peg to hang his variations on, but he doesn’t suggest he’s exploring the very nature of narrating. Lee puts fiction-making at the center of his game.

It would be misleading to summarize the plot, since the film aims to put any firm sense of what really happened into question. The core, we might be tempted to say, is the story of a schoolgirl, Cho-hee, who is shunned because she has had sex with an unnamed man. A boy in her class takes pity on her, and when he finds that she has slashed her wrists in a forest glade, he rescues her. They tentatively fall in love and flee to Seoul. On their first night there, he takes fright and returns home. Left alone, she turns to prostitution, and years later, when the boy is now in Seoul in film school, she agrees to participate in a student film he’s crewing. He doesn’t recognize her. More years pass, and the boy is now a film director. He returns to the village, recalls their runaway romance, and in despair attempts suicide. Meanwhile, Cho-hee’s son, whom she has left with her grandparents, comes to the village in search of his mother.

I think it’s fair to say that even this bare-bones anatomy of Romance Joe isn’t fully registered on a first viewing. And in any case, my synopsis is misleading. Why? Because many of these actions are presented as intersecting tales told by two characters who don’t know one another. A Seoul screenwriter recounts the story of the boy’s search for his mother as a purely fictitious one, an idea he has for a script. Alongside that tale, but not precisely inside it, we see Lee, another writer who’s blocked on a story and visits a village to compose a film. There he spends a long night with a tea lady-hooker, Rei-ji, who takes over storytelling duties. Like Scheherazade, she regales him with another story (see our top still). Her tale focuses on the suicidal screenwriter she calls “Romance Joe”–who turns out to be a filmmaker who has gone missing.

So we have one character telling the story of another character who’s hearing a story presented by Rei-ji–a story about yet a third filmmaker, the despairing director, and one that includes his own memories. More confusingly, Rei-ji’s story not only overlaps with the boy’s quest; she becomes a character in the first screenwriter’s imaginary plot. To add to the intricacy, the film employs only partial framing situations, so we might get a scene establishing one tale’s telling, then the embedded tale, and then another situation of telling, as if what we’ve just seen was launched by one storyteller but picked up by another. Instead of a Chinese-box or Russian-doll structure, with one tale neatly enclosed in another, we get something like a cut-and-shuffle mix. And like In Another Country, this film doesn’t wrap things up by a return to the narrating frame; we’re left with something more ambivalent–a question about the very status of the whole assemblage of stories.

It sounds choppy, but it all flows. As one scene slips into another, with abrupt reminders that we’re seeing events told by someone or other, we’re confronted with a cascade like that in Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. We’d be unlikely to recall the precise moment when one story melted into another. Storytelling is linked to rumor and gossip, chiefly by the fact that the trigger for Lee’s initial writer’s block is the suicide of a major actress, supposedly hounded by innuendo. The chief parallel is to Cho-hee, driven to suicide by malicious classmates, but other characters sport the scars of slashed wrists. In this context, the motifs of rumor and suicide tie together the stories conjured up by each of the narrators–again, apparently operating in some predetermined harmony.

Throughout, our uncertainty is increased by some tantalizing misdirections. Might Rei-ji, not Cho-yee, actually be the boy’s mother? Has Lee, after hearing Rei-ji’s story, created the very film we have watched? Finally, the possibility that Rei-ji is no less a fictioneer than the professional writers is broached when she returns to the teahouse and tells the younger hooker that you can make more money through talk than through sex. “Everyone wants a different story. Put some thought into what clients want.” In telling one screenwriter a story about another one, she’s just suiting the service to the customer.

When we study narrative we naturally emphasize the main plot points, the twists and climaxes that claim our attention, the hints that pay off: the gun in the first act that goes off in the last. But films like In Another Country and Romance Joe remind us, as Roland Barthes put it, that “reading is forgetting.” By planting items that will become important later, filmmakers keep us focused on what’s to come and eventually mobilize memory to make all the pieces fit. But filmmakers can also seed their plots with small things that we barely register, then bring them back as half-recalled items. Films like Hong’s and Lee’s are more than puzzle movies; they induce our imaginations to grapple with the limited capacity of our memories. Those limitations in turn affect how we judge characters and the truths of the tales they bear. And in films like theirs, as often in life, our judgments have to remain in tense suspension.

I discuss problems of viewers’ memory in “Cognition and Comprehension: Viewing and Forgetting in Mildred Pierce,” in Poetics of Cinema. I consider Jerry Maguire‘s narrative organization in The Way Hollywood Tells It. For previous VIFF entries that examine complex narration and plot structure, go here and here.

P.S. 5 Oct 2012: Sean Axmaker, with whom we spent many lively hours at VIFF, has posted reviews of several Asian films, including Romance Joe, at Parallax View.

In Another Country (2012).

Seduced by structure

Mysteries of Lisbon.

DB here:

If you’re hungry to learn about the ways films can tell stories, a festival provides a feast. A huge array of narrative strategies is spread out for your delectation. You won’t like every movie you see, but thinking about the mechanics of each one can deepen your experience of it, as well as your appreciation for just how wide cinema’s resources can be. You also get to see how more unusual approaches to storytelling are often imaginative revisions of more traditional strategies.

We can usefully think about narrative from three angles. We can study the story world that a film conjures up: the characters, places, and actions we encounter. We can analyze plot structure, the distinct parts that are put together sequentially. They might be scenes or sequences or larger-scale parts, like the Hollywood screenwriters’ “acts.” We can also analyze narration, the patterned, moment-by-moment process of presenting the story world and the plot structure. Think of a narrative as like a building. The building’s furnishings correspond to the story world, and the architectural design of the building, plan and elevation, is like plot structure. Our real-time pathway through the building, from the front doorway into its depths, corresponds to narration.

The Vancouver International Film Festival that Kristin and I have been visiting offers a banquet of storytelling devices—some quite traditional, some fairly fresh. I’ll just survey some aspects of structure that I found intriguing.

The longest distance between points

The Chinese blockbuster Aftershock, centering on the 1976 earthquake that struck Tangshan, has earned some complaints about weepiness and jokes about “Afterschlock.” Perhaps melodrama makes many critics uncomfortable. They seem more at home with comedy and noirish crime stories, perhaps because the emotions stirred by these are bracketed by a degree of intellectual distance. But tell a story about a happy family split apart by a catastrophe; show a mother forced to choose between saving her son and saving her daughter; show that the girl miraculously escapes death; present her raised by a pair of new parents; and dwell on the fact that her mother, living elsewhere, expects never to see her again—do all this, and you court mockery.

Well, mockery from everybody except the hundreds of thousands of people who have always enjoyed these situations. Aftershock is now the biggest box-office success in Chinese film history (presumably using today’s currency standards). Whatever the film owes to Chinese traditions, it is easily understandable in a Western context. Stories based on pseudo-orphans, separated siblings, and parents forced to give up children have long been sure-fire. Les Deux orphelines, an 1874 play, is one strong prototype. This pathetic tale of two sisters torn apart in post-revolutionary Paris was adapted by many directors, including Griffith (Orphans of the Storm, 1921). Feuillade developed similar motifs in Les Deux gamines (1921), L’Orpheline (1921), and Parisette (1922). A mother’s loss of her children through accident or social oppression is another stock situation, seen in sublime form in Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff. The obligation to pick a child to save is at the core of Sophie’s Choice, a more highbrow melodrama. Likewise, the discovery of unexpected kinship forms the climax of many stories, from Oedipus Rex to Twelfth Night and beyond.

You may call these conventions hackneyed, but it would be better to call them tried and true—proven effective by centuries of deployment, counting on emotions aroused by ties of love and blood. Such situations would be good candidates for narrative universals, which can be reshaped by local cultural pressures.

The premise of a fragmented family bears chiefly on the story world. The filmmaker still must choose how to structure the plot. For Aftershock, director Feng Xiaogang and his collaborators settled on the time-honored route: parallel stories across the years, shown by means of crosscutting. After the quake, scenes of the mother and son alternate with scenes showing the girl’s rescue and her life with her adopted parents, both soldiers in the People’s Liberation Army. For about the first sixty minutes, the segments are rather long, but after that shorter scenes from each plot line are intercut. The son moves off to a separate life, but his success as an entrepreneur is given short shrift. The plot concentrates on the daughter’s college career, her sometimes stormy relation with her foster parents, and her unexpected pregnancy. In the meantime, the mother survives, turning aside a kindly suitor in order to preserve her faithfulness to the husband who saved her life.

Narrationally, the alternation between the separated characters gives us superior knowledge. We know, as the mother and brother do not, that the daughter survives; we also know that she nurses a bitter memory of hearing her mother choose the rescue of her brother. Likewise, we know that the mother has tormented herself for decades over her forced choice. Thus the recriminations that will burst out after they rediscover one another will require some healing, which is provided in the plot’s last phase. Melodrama depends on mistakes, and they must be corrected. In a telling image of two sets of schoolbooks (not previously shown to us), we and the daughter realize that over the years the mother has been thinking of her as if she were still alive.

The dual structure can also tease us with suspense. At the hour mark, we learn that both the brother and the daughter are in Hangzhou, without each other’s knowledge. The brother even encounters the foster father. It’s the sort of coincidence that leads us to expect a reunion. Coincidences, I mentioned in an earlier entry, are fascinating narrative devices, and here the fortuitous convergence doesn’t actually pay off. But it does prepare us for the genuine reunion that will take place an hour or so later, when an earthquake hits Sichuan in 2008.

There’s a lot more to be said about Aftershock; I was struck by the fact that the children are left in the collapsing apartment because the parents have sneaked off to have sex in the husband’s truck. (So is the whole arc of suffering the punishment for a little carnality?) But just sticking with structure, we find that a cluster of ancient plot devices, fed into the established technique of crosscutting, can still find purchase in a contemporary film. In films like Aftershock, as in Hollywood’s romantic comedies and horror films and historical adventures, very old narrative conventions live on. Suitably spruced up with CGI, they still provide pleasure.

Sometimes, however, you get the sense that filmmakers in other cultures are borrowing conventions of recent Western films. This seems the case in City of Life from the United Arab Emirates. Faisal is a spoiled playboy who spends his nights with his pal Khalfan, a fistfight-prone club-hopper. Natalia is a Romanian flight attendant who gets romantically involved with an advertising man. Basu is a taxidriver with an uncanny resemblance to a Bollywood star, and so he tries to supplement his earnings by appearing in a nightclub. As all of them move through Dubai, their lives intertwine.

We have, in short, what I’ve called a network narrative. Mostly the plot lines are juxtaposed through crosscutting, but sometimes the characters in one line of action encounter those in another. Faisal is at a club on the same night as Natalia is there, with her boyfriend and her roommate. Objects circulate as well. Natalia pays Basu for a cab ride, and Basu preserves her €20 note until he has hit rock bottom. At the midpoint, an ad campaign links Natalia’s boyfriend, Faisal’s father, and Basu’s job. Many of the conventions of the “small world” network format are included, with one character remarking that Dubai is a small city. Our old friend the traffic accident (shot and cut with exceptional vividness) plays a crucial role. A refuse collector threads through the plot, turning up at unexpected times and providing an ironic coda.

Director Ali F. Mostafa mobilizes a lot of contemporary techniques, including fast motion and rapid cutting (3.6 seconds average shot length). The editing sometimes extends the crosscutting principle by flipping back and forth between two successive scenes, creating little flashforwards. For instance, when the adman Guy phones Natalia to introduce himself, we cut to them talking in a bar and then back to her listening to his sweet talk.

The anticipatory cuts lead us to expect that Guy is calling to ask her out, and Natalia will accept. This sort of cross-stitching can be found in The Godfather and other films of the late 1960s and early 1970s, and it has shown up sporadically since, but it’s rare enough to still look modern.

In cinema, network narratives can occasionally be found before the 1990s, but they’ve become far more common. I count nearly 150 films of the last twenty years employing the structure. In literature, of course, such plots go back quite far, and they formed the basis of nineteenth-century novels by the likes of Balzac, Dickens, Zola, and George Eliot. Television soap operas and ensemble series like Hill Street Blues showed that modern media’s long-form formats fit well with network storytelling. So cinema has caught up, adjusting the template to feature-length plots. City of Life shows that artists from emerging filmmaking nations can use this structure to enter a festival circuit dominated by Western norms of construction. At the same time, those artists can tailor this structure to their own ends—in this case, it seems to me, presenting Dubai as a city of emigrants ruled by a feckless leisure class.

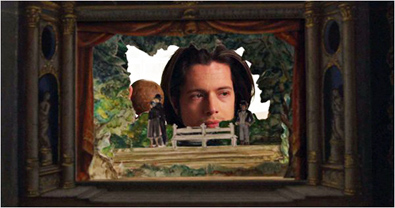

The theatre of memory

What happens, though, when conventions of sprawling nineteenth-century novels aren’t squeezed so drastically into the usual feature length? I had a chance to find out from Vancouver’s screening of Raul Ruiz’s four-and-a-half-hour Mysteries of Lisbon. Based on an 1854 novel by Camilo Castelo Branco, a fictioneer as prolific as Ruiz himself, the film doesn’t trim off the exfoliating plot lines that we enjoy in three-deckers from the period. This being a Ruiz film, there is as well a tangible pleasure in the artifice of storytelling. The film acknowledges that all the handy coincidences, buried pasts, multiple identities, and revelations of kinship are there for our delectation.

Orphans again: João is being raised in a church school, but he has no idea of his parentage. Early on, kindly Father Dimis tells him that his mother is Angela, the countess of Santa Barbara, but her brutal husband is not his father. We are soon embarked on the extended flashback that traces the doomed love affair that results in the birth of the young hero, now named Pedro. In the course of that tale, we meet two more suspicious characters, the gypsy Salino Cabra and the hired assassin Heliodoros.

This recounted history is only the first of a cascade of flashbacks, issuing from several characters, and these gradually show deep connections among persons tied to Pedro’s past. Secondary characters in one story become protagonists of another. The young hero is gradually displaced as the center of the action by war, secret romances, rivalries, duels, and infidelities. Like Pasolini in his Trilogy of Life, Ruiz is happiest when opening up a plot detour that will eventually become a new main road.

By the end, our young hero has become something of a nullity, an empty center around which aristocratic ecstasies and follies have swirled. He’s something like the Dubai of City of Hope: a point of intersection of many fates. He’s also a passive observer of scale-model dramas played out on his toy theatre stage. His voice-over narration has enwrapped the whole film, and our last glimpse of him is as merely a narrator. Pedro seems finally to realize that his entire existence has served simply to gather other people in a tangle of doomed passions.

Mysteries of Lisbon has a rich, high-thread-count look, but it’s not your usual prestige costume drama. The long takes cling to characters as they flirt their way across a ballroom, and the camera slips through walls in the manner of old-fashioned cinema. There are the usual Ruiz flourishes of hallucinatory deep focus (achieved through split-focus diopters), characters floating rather than walking, and the occasional peculiar angle. But the film remains calm and lustrous, culminating in a slow tread into pure light.

Mysteries of Lisbon has a rich, high-thread-count look, but it’s not your usual prestige costume drama. The long takes cling to characters as they flirt their way across a ballroom, and the camera slips through walls in the manner of old-fashioned cinema. There are the usual Ruiz flourishes of hallucinatory deep focus (achieved through split-focus diopters), characters floating rather than walking, and the occasional peculiar angle. But the film remains calm and lustrous, culminating in a slow tread into pure light.

Ruiz’s appetite for narrative is almost gluttonous; he supposedly wrote over a hundred plays in six years, and he’s made about as many films. He once told me that he thought that Postmodernism was simply a revival of the Baroque in modern dress. From Mysteries of Lisbon, it’s clear that he sees in many older narrative traditions affinities with our tastes today. Network narratives? They’ve been done, and maybe better, centuries ago. Follow the lacy tendrils of classic family-origins plots, and you’ll find a pattern as intricate as anything in Short Cuts or Pulp Fiction. More story ahead: there’s a six-hour television version.

Rumination on ruination

Ruiz understands that modernist narrative techniques, including unreliable narrators and fancy time-switches, depend upon a long tradition in at least two ways. First, very often the tradition got there first; scholars like Meir Sternberg and Robert Alter have demonstrated complex plays with chronology and point of view in the Bible and the Greek classics. Secondly, unusual plot structures may ring unexpected variations on more conventional ones. Case in point: reversed plot sequence.

Again, this seems to be something of a modern trend. The locus classicus appears to be Harold Pinter’s 1978 play Betrayal, in which, scene by scene, the plot proceeds in reverse chronology. This was filmed in 1983 and gave birth to a famous Seinfeld episode. As you know, Memento, Irreversible, and other recent films have taken up reverse-chronology plotting. Actually, however, there are several earlier instances, notably the 1934 Kaufman and Hart play Merrily We Roll Along (turned into a musical by Stephen Sondheim) and W. R. Burnett’s 1934 novel, Goodbye to the Past. Other examples, some going back quite far, are listed here.

Rumination, a film by Xu Ruotao in the Dragons & Tigers young directors competition at Vancouver, turns the structure to political ends. Reduced to the bare bones, the film shows a teacher, his wife, and their son caught up in the Chinese Cultural Revolution. The father falls in with a gang of Red Guard youths rampaging through the countryside. The son trails the gang at a distance and occasionally interferes with their acts of violence. These story events are arranged in blocks, with each cluster of scenes associated with a specific year. The blocks proceed backward in time, from 1976 to 1966. After a prologue, the film shows scenes of the waning of the Revolution; before the epilogue, we get a stalwart young man announcing the Revolution’s birth.

The scenes are fairly episodic and independent, so I didn’t detect the backwards structure for quite a while. But my uncertainty had another source. Xu introduces each year’s scenes with a date that is, except for one instance, not the year of the actions shown. In fact, while the segments move in reverse order, the years’ designations move in chronological order.

The opening 1976 section is labeled 1966, the 1975 section is labeled 1967, and so on up to the end, with the 1966 action designated as 1976. So we see the father’s reunion with his wife, a moment of clumsy embrace, long before he decides to leave home. As you’d expect, there’s one year in which the action and the tag coincide, 1971, and that is the only one built out of photos and film clips from the period. The year is privileged, Xu explains, because that was the year of the mysterious plane-crash death of Lin Biao, a military hero and Cultural Revolution leader who was accused of plotting Mao’s assassination.

In my viewing, the misleading dates helped conceal the reverse chronology. Confronted with so many discrete episodes of unidentified characters sprinting through the countryside, beating passersby and stealing chickens, I took the default option and assumed that the segments were chronological. Moreover, the film’s scenes play out almost entirely in overcast landscapes and decrepit factories, a landscape in which I couldn’t detect any indications of change from year to year. Watching Ruination a second time, I saw the reversal more clearly, but I also thought that some segments tease us into thinking along chronological lines. An early scene shows the father getting up in the morning (a conventional way to start a plot), saluting Chairman Mao’s statue, and reading from the Little Red Book. Yet this scene is set in 1975, after the father has returned to his wife from his Red Guard period.

Moreover, there’s some evidence that the son actually matures across the film, even though the scenes show him objectively getting younger. By the end of the plot (the earliest moment in story time) he seems to have transformed himself into a strapping young Red Guard. Supporting this construal is the fact that in the Q & A after the showing, Xu mentioned that one influence on his film’s design was The Curious Case of Benjamin Button!

Xu explained that the tragedy of the Cultural Revolution could not be comprehended through normal storytelling techniques. I suspect that viewers familiar with the relevant events and the film’s slogans, iconography, and oblique citations (even to Godard) could follow the backwards sequencing. But I suspect that those viewers would need a sense of the historical chronology to grasp the 3-2-1 order of the plot. It seems to me that Xu, known until now as a painter, has shown how an innovative approach to plot structure relies on conventional responses even as it thwarts them.

Hahaha indeed

Hong Sangsoo has been one of the leading experimenters with narrative in today’s Asian cinema. My two favorites, The Power of Kangwon Province (1998) and The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (2000) have engaged the viewer in playful puzzlement about how story lines can collide or slip sideways, how our memory of earlier scenes’ action can be tested and found faulty. I haven’t been deeply engaged by his recent forays into more straightforward drama/comedy, such as The Woman on the Beach (2006), but his two latest features, both from this year and both on display in Vancouver, completely satisfied my hunger for intriguing plot structures.

It’s an unspoken convention of recounted-flashback tales that even though the events are told by A, B learns everything that we do—everything, that is, that we can see or hear in the flashback. But Hahaha decouples the verbal recounting from the visual presentation. Here listener B definitely does not grasp what we witness happening onscreen in the tale as told.

Hahaha is a parallel-protagonist tale. Two pals meet for some drinking before one, Munkyung, leaves South Korea for Canada. Through a series of flashbacks, they regale each other with their recent adventures, mostly amorous. The plot is structured as two alternating streams, crosscutting one man’s tale with the other’s and usually returning to the framing situation of their drinking bout. But because we can see what each one recounts, we come to realize that both stories are populated by the same people, notably the tempting female tour guide Seongok. And those people have their own relationships, which we must piece together out of the glimpses we get in each man’s tale.

Neither Munkyung nor his pal Jungshik has a clue that they are part of a fairly tight circle. The result, as usual with Hong, is a comedy of ironic misunderstanding and the puncturing of male pretension. Hahaha can also be seen as his response to the rise of network narratives. Characters in such a film don’t usually realize the larger mosaic they’re part of; the intersecting lives in City of Life transform one another unwittingly. Normally that lack of awareness isn’t the main point of the film. Here it is, and it’s wrung for classic humor at the protagonists’ expense.

In Oki’s Movie, Hong gives us another fractured plot, but now in the form of four short films. They center on three characters: Song, a film director turned professor; his student Jingu; and Oki, the woman both men are interested in. The raggedy credits of each short suggest handmade movies, but what we see in each one is the polished style familiar from Hong himself, including his current interest in abrupt zooms.

The four-part structure is far from transparent. It might be taken as a series of episodes from the trio’s lives. The first film, “Specters of the New World,” which presents Jingu as a professor himself, would have to take place in the present, and the following three would then be presenting flashbacks to the Jingu-Oki-Song triangle. In that case, the first segment would prove that Jingu did not wind up with Oki, as he’s married to another woman.

Perhaps, though, all four films are free hypothetical variations on the central situation. I’m not sure that we can easily arrange the events in the second, third, and fourth episodes chronologically. The films could be presenting successive groups of events, or events scattered across a single time span and then selectively gathered around one of the central characters. The first episode is largely organized around Jingu’s range of knowledge; the second is confined to professor Song; and the third is explicitly presented as Oki’s own thoughts. Earlier Hong films have offered us contrasting, even incompatible plots built out of a core group of characters. Oki’s Movie may be using the framing conceit of student films (none of which is plausible as a student film) to give us a suite of variants on the love triangle.

The idea of ambiguous variation is made explicit in the final mini-film, “Oki’s Movie.” It’s a sustained exercise in—yes, again—crosscutting. This episode alternates two excursions to Mount Acha, one with each man. Shot by shot, we see different courtship styles and we hear her differing reactions to her two lovers. Was she dating both men at once? When did the two excursions take place? Which one occurred first? As these questions are juggled, we get a rapid checklist of Oki’s attitudes, in voice-over, toward both these minor-key losers.

In both Hahaha and Oki’s Movie, Hong takes what’s offered by tradition—in this case, the romantic comedy and the conventions of flashbacks, crosscutting, and restricted narration—and creates a fresh structure. The play of novelty and norm is engrossing in itself, apart from the vagaries of the drama. Our appetite for narrative will always be whetted when directors find ways to whip up something new out of familiar ingredients.

For more on the three dimensions of film narrative, as well as discussion of the principles of network construction, see my Poetics of Cinema. There’s more discussion of flashbacks in film in this entry. On early narrative structure, see Meir Sternberg’s Poetics of Biblical Narrative and Robert Alter’s Art of Biblical Narrative, as well as Sternberg’s discussion of The Odyssey in Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction. For a sharp-eyed consideration of Oki’s Movie, see Andrew Tracy’s review at Cinema Scope.

Oki’s Movie.