Archive for the 'Directors: Hou Hsiao-hsien' Category

An auteur, three archives, and the archivist as auteur

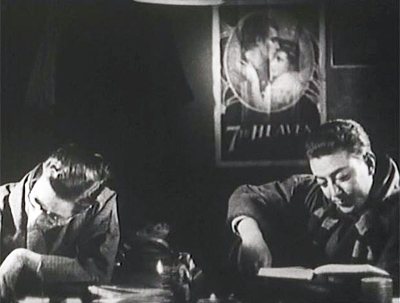

City of Sadness (1989).

DB here:

The books have been piling up again, and so I pass along some recommendations. This time the volumes are unusually handsome. Apart from what they say, these publications display how sumptuous a serious film book can be.

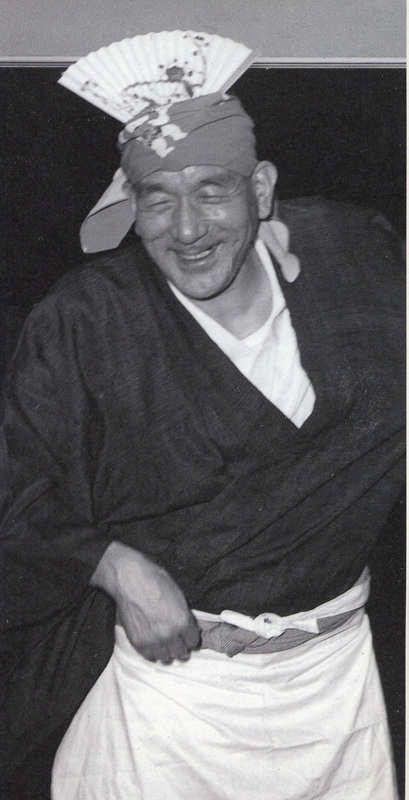

Particularly welcome, in light of the touring retrospective of Hou Hsiao-hsien films that began at MoMI on 12 September, is Richard I. Suchenski’s anthology of writings on and by the director. Hou Hsiao-hsien is packed with color illustrations and fully up to the standard of other publications from the Austrian Filmmuseum.

Particularly welcome, in light of the touring retrospective of Hou Hsiao-hsien films that began at MoMI on 12 September, is Richard I. Suchenski’s anthology of writings on and by the director. Hou Hsiao-hsien is packed with color illustrations and fully up to the standard of other publications from the Austrian Filmmuseum.

Some of our top critics and scholars have contributed essays. From Japan comes Hasumi Shigehiko on Flowers of Shanghai; from France, Jean-Michel Frodon on Hou’s collaboration with Chu Tien-wen; from Canada, James Quandt, eloquent as ever on Three Times. American scholars are here too. We have Jean Ma on The Puppetmaster, Abe Mark Nornes on calligraphy and frame space, Kent Jones on time in Hou, and James Udden on Dust in the Wind. Jim is author of the first English-language book on Hou and a contributor to this website. To these essays are added the unique perspectives offered by Taiwanese observers Peggy Chiao on City of Sadness and Wen Tien-hsiang on unmarried women in Hou. A wide-ranging introduction by Richard brings out virtually all the artistic, political, and cultural issues that have been raised by Hou’s body of work.

Unabashedly auteurist—and what’s wrong with that?—the collection adds even more value by including an interview with Hou and Chu, who supply precious information about the work-in-progress The Assassin. There are also statements by three distinguished directors: Olivier Assayas, Jia Zhang-ke, and Koreeda Hirokazu. Koreeda notes: “Life’s details (like eating) should be respected.”

We learn as well about the craft behind the artistry. We get a cascade of information from artistic collaborators, including cinematographers, sound designers, actors and others. For example, Tu Duu-chih, sound expert, says: “What [Hou] wants is a natural form of expression and he always manages the atmosphere to meet his needs. If he shoots a drinking scene, for example, he will select real dishes and alcohol and they must be delicious.” Delicious is a good word for this book too, an absolute necessity for every serious cinephile.

Birthday greetings to Vienna and Brussels

Speaking of the Austrian Filmmuseum, it celebrates its fiftieth anniversary this year. To celebrate, it has issued a heavyweight, unorthodox boxed set, The Austrian Film Museum at Fifty. Director Alexander Horwath has done a monumental job in bringing a great deal of material together, creating not only a history of the Filmmuseum but a real contribution to international film culture.

In volume one, Aufbrechen (Setting Out), Eszter Kondor provides a history of the institution, with emphasis on its emergence the 1960s and 1970s. Volume two pays homage to Béla Balázs with the title Das sichbare Kino (The Visible Cinema). This is a plump anthology of texts, pictures, and documents from the museum’s history. Given the fact that Peter Kubelka was curator for many years, you’re not surprised to find a letter from Michael Snow and an email from Ken Jacobs. But I didn’t expect an interview with Groucho Marx (letter appended) and correspondence from Don Siegel. This volume also includes a complete record of programs at the museum.

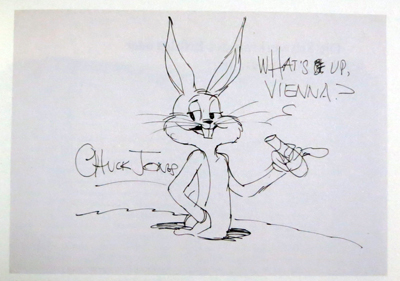

Volume three, Kollection, is a visual treat. It gives us a short history of film in fifty items. The survey includes The Unfinished Letter, a 22mm Edison film ca. 1911-1913, outtakes from Murnau’s Tabu, Morgan Fisher’s site-specific Screening Room (1968), Kurt Kren’s leather jacket, Chuck Jones’ What’s Up, Vienna? (1983), and frames from Norbert Pfaffenbichler’s dizzying Notes on Film 03: Mosaik Mécanique (2007).

The texts in all of the books are in German, but there are so many posters, photos, sketches, diagrams, and storyboards (one by Vertov) that you learn merely by browsing. These volumes are a must for research libraries with a focus on film.

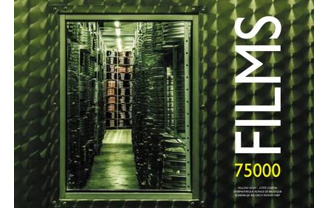

No less idiosyncratic is another anniversary volume, this one from the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, now known as the Cinematek. It was founded seventy-five years ago and, as if by cosmic convergence, it holds 75,000 film titles. But the book, 75000 Films, isn’t a celebration of this particular museum. It’s a book about film archiving in general. As curator Nicola Mazzanti puts it in his introduction:

No less idiosyncratic is another anniversary volume, this one from the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, now known as the Cinematek. It was founded seventy-five years ago and, as if by cosmic convergence, it holds 75,000 film titles. But the book, 75000 Films, isn’t a celebration of this particular museum. It’s a book about film archiving in general. As curator Nicola Mazzanti puts it in his introduction:

Film archiving is already changing and in a few years will be very different from what it is now. New skills, new machines, new people. As no book like this one exists about film archiving we wanted to make sure that at least one is published before the picture changes completely.

What will change? Chiefly, the sheer tactility of the work.

Inspecting a film to check its conditions and its history is all about a physical relation with the material. While winding through a reel of film your fingers run along the edges to feel imperfections and damages. One bends a piece of film to assess its brittleness, caresses a splice to check its resistance. . . .

In other words, it is a precise, careful, dedicated and highly specialized work that often is as tedious as rewinding hundreds and thousand of reels (by hand, as electric motors are often dangerous to the film). An uneventful process until you stumble upon a lost film or a camera negative or perhaps just a beautiful copy in which the colours are perfectly preserved. And the beauty of those images takes your breath away, the thrill of the discovery repays you for all the hours of boring inspections.

To capture both the routine and the exhilaration, Nicola let three photographers document, without constraint, what they saw behind the scenes of the Cinematek. Xavier Harck, Jimmy Kets, and Marie-Françoise Plissart took their cameras into the vaults, the work spaces, the projection rooms, even the loading docks. The images are gorgeous and radiate the touch and heft of reel after reel, can upon can, in profusion that evokes Resnais’ Toute la mémoire du monde.

Along with the photos are three essays about film archives. They are personal reflections on cinematheques and their place in film culture. Dominique Païni writes (in French) about how access to films changed during his years as director of the Cinematheque Francaise. Erich de Kuyper, filmmaker and novelist, reflects in Flemish on guiding the Amsterdam Film Museum and creating the programs there. I contributed a piece in English that tries to fit my personal research work into broader trends of film archiving. My essay is elsewhere on this site.

The age of impresarios

Langlois is the dragon who guards our treasures.

–Jean Cocteau

In spring of 1973 the New York Times announced that a city board had approved the leasing of a building that would house the City Center Cinematheque. This was to be the American counterpart of the Cinémathèque Française, and Henri Langlois was to be its director.

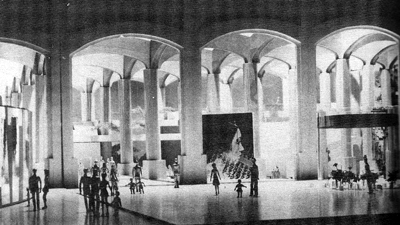

Langlois’ project was as vast and flamboyant as the man himself. An old storage building under the Queensboro Bridge, on First Avenue between 59th and 60th Streets, would be converted into a cathedral of cinema. I. M. Pei would design the new building. (One sketch is above.) There would be three auditoriums, a staff screening room, an exhibition space, a restaurant, a bookstore, and a flower market. Programs would draw upon Langlois’ archive of 60,000 titles, and there would be screenings from morning to midnight, offering as many as fourteen films a day. Langlois predicted that attendance would surpass a million a year.

My own encounters with Langlois, brief though they were, came at just this moment. I needed to see several French silent films for my dissertation work, and in 1972-1973 I wrote to Langlois asking for permission to visit his archive. Thanks to Sallie Blumenthal, we made contact and he gave me permission. In July, during the summer of Watergate, I arrived at the Cinémathèque. An expansive Langlois welcomed me and gave me a tour of the Musée du cinema, which had been somewhat prematurely opened. Jean-Louis Barrault’s costume from Les Enfants du Paradis was draped on a coat hanger nailed to a wall. During my two months in Paris, thanks to Langlois and Mary Meerson, I saw several rare films on Marie Epstein’s viewing table.

I have sometimes wondered if my stay there was an accident of timing. Perhaps as a young American I benefited from Langlois’ high hopes for his transatlantic alliance. Pressed by money problems in Paris, he could imagine that the American branch of the Cinémathèque would vindicate his vision of a motion picture museum without walls: films circulating everywhere, films shown all the time, no film too minor to merit attention. Had the City Center venue come to fruition, it would have overshadowed the Museum of Modern Art, Manhattan’s temple of cinema history. But the project collapsed fairly soon. It required private financing, and during the recession and the oil crisis money was hard to come by.

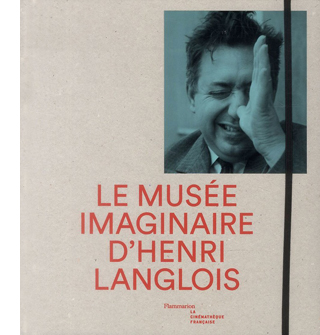

Langlois’ American adventure is just one episode in the tapestry presented in another archive-related anniversary volume: Le Musée imaginaire d’Henri Langlois. Edited by Dominique Païni, this de luxe production accompanied the Cinémathèque’s massive exposition from April to August. If Langlois were still living, he’d be 100 this year, and the sumptuousness of this catalogue is in part a testimony to what he accomplished. He helped make cinema equal to the other arts in cultural significance. But the enterprise is not too serious: Païni has made the volume’s emblem the famous shot, taken by an unknown hand, of Langlois in the kiss-my-ass salute.

The menu is familiar. There are informative essays by various hands, interspersed with illustrations and documents. But the execution is extraordinary. Reminiscent of 1920s publications, on rough paper and with decentered blocks of type, this square volume seduces you into sustained browsing. Moreover, it contains reproductions of artworks related to Langlois and his institution. We have works by Beuys, Chagall, Duchamp, Fischinger, Léger, Matisse, Miró, Picabia, Richter, Severini, and Survage—all connected, somehow to Langlois and cinema. There are frames from Le Métro, a 1934 film by Langlois and Franju., There are guest-book signatures, catalogue covers, correspondence, and much more.

The catalogue of the exposition is accompanied by a slender but no less ingratiating biographical chronology, festooned with still more images. Mais qui est ce Monsieur Langlois? opens with a striking portrait by Henri Cartier-Bresson and ends with the telegram sent by Jean Renoir after Langlois’ death in 1977. “We have lost our guide, and now we feel alone in the forest.”

I met Langlois in the days of rivalry among archives, a good deal of it triggered by him. If you were welcomed to Archive X, and word got to Archive Y, that venue would shun you. Surveying these books, I was struck by their quiet assumption that archives must collaborate on projects and share their treasures. After Langlois, archiving became more cooperative, more routinized, more professional, and–Langlois and his allies would say–more boring. We may not need dragons now. Perhaps, though, we had to go through the turmoil of the Age of Impresarios in order to appreciate why collecting films was so important.

For some ideas on Hou’s visual style, see Chapter 5 of my Figures Traced in Light, this entry, and a discussion of the early films on this site.

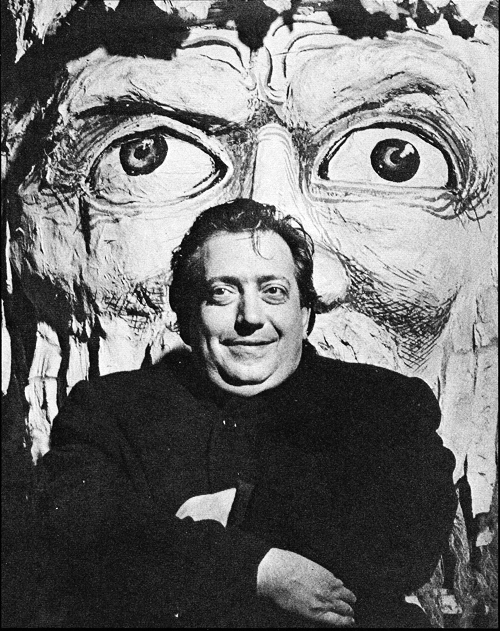

Henri Langlois. Photo by Pierre Boulat.

News from Hou

Hou Hsiao-hsien and producer and production designer Huang Wen-ying on the set of The Assassin. Photo by James Udden.

DB here:

Stephen Cremin brings good tidings: Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Assassin, a project planned since 1989 and in production for several years, has completed shooting. It’s aimed for Cannes. More details at Film Business Asia.

About a year ago Jim Udden visited Hou on the set and shared his insights with us in this entry.

A new Hou film, especially if it featured swordplay, would make me a very happy man. 2013 was a good year for several top Chinese directors, especially Tsai Ming-liang, Jia Zhang-ke, Johnnie To Kei-fung and Wong Kar-wai. Having a new film from Hou augurs well for the Year of the Horse. And it stars the sultry Shu Qi.

P.S. 19 January 2014: Alas, the Year of the Horse won’t be as auspicious as I’d hoped. Jim Udden tells me, on the basis of a message today from Ms. Huang, that The Assassin will require another year for post-production. But they are likely to show some clips at Cannes, so there’s that. . . . Thanks to Jim and Ms. Huang for the correction and update.

Watch again! Look well! Look! (For Ozu)

Okada Mariko and Tsukasa Yoko with Ozu, on the set of Late Autumn (1960).

DB here:

Ozu was born on 12 December (in 1903) and died on 12 December (in 1963). He has been gone fifty years, yet his films are as fresh, inviting, funny, and moving as ever. As chance would have it, my book Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema was published twenty-five years ago. Two events of the past few months have brought me back to him.

First, my biannual summer course in Antwerp, held under the auspices of the Flemish Film Foundation, was focused on him. As I’ve explained in earlier years (2011, 2009, 2007), at this Summer Movie Camp, across a week we immerse ourselves in films and wrap lectures around them. It was a joy to see a dozen of his films, mostly in good 35mm prints. Our sessions provided an occasion for me to rethink some things I said in the book, as well as to notice more about how these dazzling, apparently simple films work and work upon us. I learned as well from the comments and questions of many of the participants. The whole experience didn’t shift my opinion, stated on an earlier Ozu anniversary, that “no director has come closer to perfection.”

The second occasion: Two enterprising Ozuphiles have just published a collection of essays, Ozu à présent (Paris: G3j publishers). Diane Arnaud and Mathias Lavin have worked very hard for several years gathering pieces from filmmakers (Erice, Kurosawa Kyoshi) and critics like Hasumi, Frodon, Rosenbaum, and Jun Furita Hirose. Many other contributors have previously written on the director: Basile Doganis (Le Silence dans le cinéma d’Ozu), Benjamin Thomas (essays for Positif), and Clélia Zernik (Perception-cinéma). As for the editors, Diane has books on Sokurov and Kurosawa Kyoshi, while Mathias has written on Oliveira and art history generally. The entire collection is stimulating and beautifully produced.

The second occasion: Two enterprising Ozuphiles have just published a collection of essays, Ozu à présent (Paris: G3j publishers). Diane Arnaud and Mathias Lavin have worked very hard for several years gathering pieces from filmmakers (Erice, Kurosawa Kyoshi) and critics like Hasumi, Frodon, Rosenbaum, and Jun Furita Hirose. Many other contributors have previously written on the director: Basile Doganis (Le Silence dans le cinéma d’Ozu), Benjamin Thomas (essays for Positif), and Clélia Zernik (Perception-cinéma). As for the editors, Diane has books on Sokurov and Kurosawa Kyoshi, while Mathias has written on Oliveira and art history generally. The entire collection is stimulating and beautifully produced.

As the title indicates, it’s centrally about Ozu’s continuing influence on modern cinema. I was asked to contribute a preface, which Diane and Mathias have kindly allowed me to reproduce below in revised form. I’m now chiefly aware of what I neglected (no mention of Wenders’ Tokyo-Ga) and didn’t know about (for instance, Claire Denis’ admiration for Ozu). These and many other matters are taken up by the book’s contributors. But I think my piece may be of interest as a small update of my Ozu book.

In 1988, most of Ozu’s surviving films weren’t easy to access. Things have changed. And since I wrote the essay, virtually all the extant work has appeared on DVD, on cable television, and in the Criterion collection on Hulu Plus. As his films become more and more familiar, we can expect ever-greater acknowledgment of his centrality. Already, the 2012 Sight and Sound poll of critics put Tokyo Story just below Vertigo and Citizen Kane; the directors’ poll put it at the very top.

Why not watch an Ozu film today? Go beyond Tokyo Story, fine as it is, to Early Summer, Passing Fancy, Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family, An Autumn Afternoon, The Only Son, The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice, Ohayo, Diary of a Tenement Gentleman, What Did the Lady Forget?, Dragnet Girl, Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth?, I Was Born, But… and on and on.

Catching up with Ozu

Ozu is a major presence in today’s international film culture. When I began seeing his work in the early 1970s, about half a dozen Ozu movies were in circulation, and of those only Tokyo Story was known to nonspecialist cinephiles. As late as the 1980s, I had to travel to archives in Europe and the US to see his rarer films. Now even the most obscure early 1930s titles are issued on DVD, and the films have been widely distributed in touring packages. They are screened all over the world, a process lovingly recorded on Twitter. Ozu is better known to a broad public than Mizoguchi Kenji is—an ironic turn of affairs, given that in many countries Mizoguchi gained fame during the 1950s and 1960s, when Ozu was unknown.

Even more famous throughout the west was, of course, Kurosawa Akira. His influence on mainstream cinema has been robust and pervasive. If slow-motion violence has become a convention in American films since Bonnie and Clyde, that is directly traceable to the director of Seven Samurai. The use of very long lenses to cover a scene, common in American cinema of the 1960s and thereafter, owes a great deal to Kurosawa’s strategies in films like I Live in Fear and Red Beard. Editing on the camera axis for visceral impact, a Kurosawa signature technique, has bumped up the visual excitement in many American action pictures.

Ozu has not had such a direct influence. He is much less easy to assimilate. With few exceptions, his signature style has been far less imitated, and it has even been misunderstood. His effect on modern cinema, it seems to me, has been far more oblique, with directors paying him tribute in discreet, sometimes unexpected ways.

Brand Ozu

Ozu wing, Kamakura Cinema World, 1996.

Ozu was careful to mark his uniqueness. He designed his films to be sharply different from those of his contemporaries. His home base, the Shochiku studio, encouraged directors to develop personal styles, and he was allowed to make artistic choices that could only be considered eccentric. At first glance, Ozu’s films may seem to melt into a broader idea of “Japanese artistic culture,” but the more films we see by his colleagues, the more idiosyncratic his works look.

Having allowed Ozu to make such singular films, Shochiku has exacted a reciprocal obligation: his legacy now serves as a trademark for a film studio. For the world at large, Japanese cinema consists of Kurosawa and Toho studios’ Godzilla, Nikkatsu action, and anime. Shochiku had its tradition of modest, humane dramas of working-class and middle-class people, treated with that mixture of humor and tears known as the “Kamata flavor” (after the Tokyo suburb where the studio was located). That tradition was sustained by Ozu and his colleagues through the 1950s as a brand identity. The forty-eight Tora-san films (Otoko wa tsurai yo, “It’s Tough to Be a Man”) became what we’d call a frachise for Shochiku from 1969 through 1996.

But as media became globalized, and as merchandising became central to sustaining filmmaking, Shochiku’s product came to seem narrowly local. Accordingly, the firm turned its attention to its most famous employee. Shochiku’s familiar postwar logo, a view of Mount Fuji, had become for westerners part of Ozu’s iconography.

Now Shochiku tried to reclaim its trademark by reminding viewers that he belonged to a bigger family.

For the local market, Shochiku tried a bit of merchandising, such as phone cards with scenes from Ozu movies. More ambitiously, there was Shochiku Kamakura Cinema World, a theme park established in 1995 at a cost of $125 million. It held many attractions devoted to American cinema, and it even allowed customers to visit a movie in the making, but one wing was devoted to Shochiku’s legacy properties, including a replica of a street from the Tora-san series. There were as well Ozu memorabilia, including a three-dimensional tableau of an effigy Ozu directing a scene in Tokyo Story. The adjacent vitrine housed a reconstruction of his work area at home, complete with whisky bottle and bright red rice kettle.

Cinema World closed in 1998, a financial failure. But Shochiku persisted and declared in 2003 that it would host a worldwide celebration of Ozu’s hundredth anniversary. That celebration consisted of a new touring program of 35mm prints of his films, with ancillary ceremonies and festival activities, and several new DVD releases. Shochiku went further and commissioned Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Café Lumière, a film in homage to the great director. For festivals and arthouse cinemas, Hou’s tribute was aimed to recall Ozu’s greatness and, by association, Shochiku’s place in film history.

As directors have sought to retain the Kamata flavor in later decades, we find hints and traces of Ozu as well. A film like 119: Quiet Days of the Firemen (1994), in which middle-aged men in a small village fantasize about romance with a young researcher, might bring to mind the overactive imaginations of the grown-up schoolboys of Late Autumn (1960). Kore-eda Hirokazu’s Still Walking (Aruitemo aruitemo, 2008) is a family drama made in full awareness of the Ozu tradition. Not surprisingly, Yamada Yoji, impresario of Tora-san, has invoked the Shochiku tradition in several productions (notably Kabei: Our Mother, 2008, and Ototo, 2010). At the start of 2013 Yamada, at 81 years of age, released an updated remake of Tokyo Story.

Ozu comes to America

Days of Youth (1929).

Since at least the early 1920s, the Japanese cinema has responding to the American cinema. During the classic period, American films did not dominate the Japanese market, as they did in many other countries, but filmmakers were nevertheless acutely conscious of Hollywood. In particular, the founding of Shochiku in 1920, with a self-consciously modernizing orientation under Kido Shiro, created a ferment that changed Japanese cinema forever.

Like other Kamata/ Ofuna directors, Ozu relied crucially on American cinema. There are visual citations (the Seventh Heaven poster in Days of Youth), lines of dialogue about Gary Cooper and Katharine Hepburn, borrowed gags (from A Sailor-Made Man in Days of Youth), and even an extract from If I Had a Million in Woman of Tokyo. More deeply, his early films absorbed the analytical editing of 1920s Hollywood. He broke every scene into a stream of precise, slightly varied bits of information in the manner of Ernst Lubitsch and Harold Lloyd.

Ozu paid American cinema a deeper tribute. Having grasped that system of axis-of-action continuity that Hollywood had forged from the late 1910s, he created his own system as an alternative. Instead of a 180-degree organization of space, he proposed a 360-degree one. This allowed him to absorb the Americans’ innovations and yet give them a new force. Cuts would use eyelines, shoulders, and character orientation, but would often show characters looking in the same direction, their figures and faces matched pictorially from shot to shot.

A cut on movement could be made by crossing what American directors called “the line.”

Further, Ozu realized that the establishing shot, that depiction of the overall space of the action, could be prolonged and split into several shots. The result was a suite of changing spaces that could be unified by shape, texture, light, or even analogy (one window/ another window). These transitional sequences substitute for fades and dissolves, turning ordinary locales into something at once evocative and rigorous.

All of these transformations of Hollywood’s stylistic schemata are rendered more palpable by a single, simple choice that is more single-minded than anything to be found in Hollywood: The camera is typically placed lower than its subject. This constant framing choice acts as a sort of basso continuo for the melodic variations Ozu will work on two-dimensional composition and three-dimensional staging.

This entire stylistic machine might seem to be aimed wholly at working out its own intricate patterns, and indeed to some extent that is what happens. The aficionado can appreciate the refinements, the theme-and-variants structuring, created by Ozu’s cinematic narration. There’s playfulness as well; how funny, he seems to say, that editing and composition can play hide-go-seek with quilts and ketchup bottles. Just as important, all these techniques nudge us to arouse our attention—to the possibilities of cinema, but also to the shapes and surfaces of the world as they change. Alongside the characters’ drama is a realm at once stable and ceaselessly shifting; the characters and their drama are subject to the same forces of mutability. Ozu’s modest pyrotechnics activate the world his characters inhabit, subject them and their actions to the same suite of transformations, and have the larger purpose of reawakening us to our world.

Made in USA

As Ozu’s films became known in the west, citation-happy directors of the 1980s took notice. An example is the moment in Stranger Than Paradise (1984, above), when Eddie reads off the list of horses running in the second race: “Indian Giver, Face the Music, Inside Dope, Off the Wall, Cat Fight, Late Spring, Passing Fancy, and Tokyo Story.” After a pause, Eddie says to bet on Tokyo Story. We know from Jarmusch’s account of visiting Ozu’s grave that he was a passionate admirer, but his films seem to me to show his debts chiefly in their “minimalist” approach to their action.

More elaborately, Wayne Wang offers a self-conscious homage in Dim Sum (1985). This story of a widow, her brother-in-law, and her daughter transfers an Ozu situation to San Francisco and a Chinese-American community. Should the daughter marry and leave her mother alone? The uncle, who runs a declining bar, urges the girl to do so. The situation, he says, reminds him of “an old Japanese movie” in which a parent urges the child to start a family. As in Ozu, the generations are sometimes captured in “similar-position” (sojikei) compositions.

To the generational split of the Ozu prototype, Wang adds the cultural division between modern America, the daughter’s home, and Hong Kong, home not only to the mother but all the friends in her age group. The generational contrasts would be elaborated upon in Wang’s later Joy Luck Club (1993), which counterpoints the experience of four mothers and four daughters.

Well aware of the Ozu parallels in the plot, Wang elaborates them through some stylistic choices. The film starts with a static thirty-second shot of curtains blowing alongside a sewing machine. The mother comes into the frame, pours tea, takes pills, and starts the machine. The next sequence consists of isolated details—a birdcage, a table.

Only then do we get a placing shot of the street, but it serves here as a transition taking us out of the home (Ozu would probably have included part of the window frame), then to San Francisco Bay and then to a young woman seen from the rear sitting on shore.

No drama is forthcoming–no conversation, not even a voice-over suggesting the young woman’s thoughts. The lyrical capstone of the sequence comes with a nearly abstract shot of the water, perhaps the woman’s point of view, but unaccompanied by language or music.

Wang has given us an imagistic preview of details to be seen later. Not only will we come to recognize the young woman as the daughter Laureen, but we’ll see the household furnishings, street locations, and bridge views at various points in the film.

The rest of the film is not as disjunctive as this opening, and Wang soon settles into the sort of loose, leisurely plotting that characterized independent film of the period. But the objects and cityscapes we see don’t become dramatically significant; they are part of the ambience of the characters, somewhat in the Ozu manner. But neither do they take on the elaborate variations and minute adjustments we find in Ozu’s “hypersituated” objects and recurring locations. Still, of all American directors Wang has most willingly adapted Ozu’s aesthetic to his own personal concerns, while paying homage to a director who was just starting to be appreciated as both storyteller and stylist.

Otherwise, the balance-sheet seems to me virtually empty. Every young American filmmaker seems to have studied Kurosawa, but which of them knows Ozu—or, like Eddie, have bet only on Tokyo Story? Filmmakers elsewhere have been more generous and discerning.

Citation, pastiche, and parody

Hou Hsiao-hsien, no cinephile in his youth, came to admire Ozu later in life, and he used citation in a more thoroughgoing way than Jarmusch had in Stranger than Paradise. Liang Ching, the modern-day protagonist of Good Men, Good Women (1995), leads a sort of parallel life with a Taiwanese woman she’s playing in a film: Chiang Bi-yu, along with her husband, who joined the anti-Japanese resistance on the mainland in 1940. But the parallel is a contrast as well, since Liang is unhappy in her love relationships and seems to lack any sense of social commitment. Her drifting, rather lost style of living is counterpointed not only to the courageous and energetic Chiang but also, via a televised movie, to Ozu’s postwar world.

Early in the film, Liang is awakened by the beeping of her fax machine. As she droops at her kitchen table, her television monitor runs the bicycling sequence from Late Spring (1948).

These cheerful shots of Noriko and Hattori on an outing provide yet another contrast to Liang’s brooding torpor about the death of her lover Ah-wei. They also suggest another way to be a heroine, quietly strong and capable of both love and defiance. And the chaste outing we see in Late Spring contrasts sharply with the intense eroticism of the flashback that follows this morning scene, showing Liang and her lover caressing each other before a mirror. Unlike Ozu’s couple, they need a narcissistic magnification of their passion. If Good Men, Good Women’s overall plot condemns the Japanese for their army’s invasion of China, Hou from the start reminds the audience of another Japan, one that after the war became, at least in Ozu’s hands, a place of humane feeling. This is no one-off joke as in Jarmusch’s citations; the Late Spring extract deepens the thematic reverberations of Hou’s film as whole.

Likewise, instead of the sporadic invocations of Ozu’s style provided by Wayne Wang, the early films of Suo Masayuki show more engagement with the Ozu manner—particularly because they are turned to comic ends. Suo’s first feature, My Brother’s Wife: The Crazy Family (Hentai kazoku: Aniki no yomeson, 1984) was a curiosity: a softcore pornographic film shot in a distinctly Ozuian style. Only in Japan can an erotic film spare the energy to borrow so explicitly from a master of the cinema. While the newly married couple has thumping intercourse upstairs, the husband’s father, sister, and brother sit calmly downstairs, sighing or frowning slightly in response to the gymnastics overhead. One evening the father comes home from a drinking bout and the son, like the son in An Autumn Afternoon, warns him to cut back.

Suo gives us the father sitting alone in an Ozuesque shot, and as his head slumps, Suo cuts to the wife upstairs, rolling her head forward in a similar gesture.

True to the exhaustive geometry of pornography, the brother graduates to sadomasochism, the adolescent son becomes fixated on his sister-in-law, and the young daughter takes up work in a “soapland” parlor. Thus is the Ozu family drama turned upside down, with the father observing everything with a bemused, helpless smile. Suo, who had studied film under Hasumi Shiguéhiko, turned in a well-crafted film that was a virtual parody of the late Ozu style. Of course, by the time he started, Suo was able to study video releases and mimic the Ozu look shot by shot.

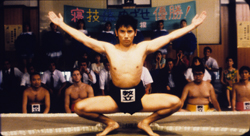

In Suo’s next films, parody turned into pastiche. Fancy Dance (Fanshi dansu, 1989) and Sumo Do, Sumo Don’t (Shiko funjatta, 1992) display a fanatically precise understanding of Ozu’s unique use of space. Suo adheres to the low camera height, builds scenes out of slightly overlapping zones, and avoids camera movement. He indulges in the master’s penchant for head-on shots that can be matched graphically across a cut, leaving us to notice the variations of color and texture within remarkably similar compositions.

Suo will even follow Ozu’s penchant for graphically matched movement across cuts. His sumo opponents spread their arms in a continuous movement as smooth as that displayed by Ozu’s drinking buddies.

Westerners often ignore Ozu’s penchant for social comedy in the Lubitsch vein, but Suo’s films happily explore this dimension. American and European filmmakers seem aware only of Ozu’s postwar films, but Suo the cinephile grasped that the 1930s college comedies offered fertile resources. Suo’s youth pictures show young people giving up modern popular culture in favor of Japanese traditions that are so old that they become fashionably retro. In Sumo Do..., a ragged college sumo team discovers that the sport turns them from slackers into adepts. In Fancy Dance, a talentless rocker, forced to live in the Buddhist monastery he has inherited, eventually learns that Zen can be cool.

Shall We Dance? (1996) modifies the Ozu look into something more generically Kamata-toned, but Suo still shows traces of the master’s rigor. For example, the first time that the camera moves is when the bored executive takes his first tentative lesson in ballroom dance. The film’s social critique is not as harsh as that in Ozu’s 1930s work, but it does dramatize the stifling limits put on both the salaryman and his family.

Just-noticeable differences

Five Dedicated to Ozu.

The two most famous Ozu homages, both from his anniversary year of 2003, are more puzzling. For neither Hou’s Café Lumière nor Abbas Kiarostami’s Five Dedicated to Ozu can be easily categorized as citation, assimilation, or pastiche. How have these two masters paid tribute to him?

Café Lumiere could easily be simply a Hou production that happened to be in Japan. It’s imbued with his characteristic narrative maneuvers, themes, and style. Even the cutaway long shots of trains, recalling some of Ozu’s urban iconography, would be perfectly at home in Hou’s work, which has made memorable use of trains (Summer at Grandfather’s, 1984; Dust in the Wind, 1987).

Likewise, Kiarostami’s Five Dedicated to Ozu might seem to take Ozu as a pretext for a foray into “pure cinema” in the manner of Shirin (2008) or the video installations Sleepers (2001) and Ten Minutes Older (2001). Unlike Hou, though, Kiarostami didn’t conceive his film as a tribute; only after having premiered it at Cannes was he invited to attach it to the fall 2003 Ozu centenary. As a result, he changed the title from the original one, Five. In explanation, Kiarostami claims that the protracted long shots in the first four episodes are akin to Ozu’s style:

His long shots are everlasting and respectful. The interactions between people happen in the long shots and this is the respect that I believe Ozu felt for his audience . . . In his mise-en-scène he respected the rights of the audience as an intelligent audience. His films were not usually very technical, which would make them appear nervous and melodramatic in the manner of today’s montage facilities.

Although Kiarostami’s statement isn’t perfectly clear in translation, he seems to suggest that Ozu favored lengthy and distant shots and avoided editing—a common misconception about the director. There is, in short, something of a mismatch between each of these directors’ “Ozu films” and the oeuvre of Ozu.

Café Lumière has recourse to one of Hou’s favorite maneuvers, casting rising pop-music stars in his films. Hitoto Yo, who had her first hit “Morai-Naki” in 2002, became his lead performer. This was a shrewd marketing move, as she is of both Japanese and Taiwanese ancestry and personifies the “fusion” aspect of Hou’s Shochiku project. Likewise, the male star Asano Tadanobu , an idol of Japanese cinema, has appeared in Thai, Russian, and even American films (e.g., Thor, 2011). Asano is also a pop musician and model. These strategic choices would, I think, have been appreciated by Ozu, who designed his scripts around Shochiku’s biggest stars and was not above “product placement” of favorite alcohol brands in his bar settings. Just as important, as with his Taiwanese films, Hou puts his young stars into a rigorously paced, controlled mise-en-scène—one owing little to Ozu technically, but a great deal to his model of incessant attention.

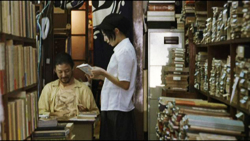

At one level Café Lumière is a family drama, a little reminiscent of Ozu’s Tokyo Twilight (1958). While visiting her parents, Yoko tells her mother she is pregnant and has no intention of marrying the child’s Taiwanese father. Her family must come to terms with this, and the situation is handled with even more subdued reactions than we would find in Ozu. At another level, the film is about a search for sound. Yoko meets the book dealer Hajime while she is researching a Tawainese-Japanese composer from the 1930s. For his part, Hajime has the hobby of recording the sound of Tokyo subways, trains, and trams. Ozu leaves it to the viewer to notice the subtle attenuation of his music and noise effects, while Hou announces and thematizes these components as part of his cross-cultural drama.

Hou, like Ozu, is a director of “just-noticeable differences,” the details that change slightly across a shot or scene. The first encounter that we see between Yoko and Hajime is a lengthy long-lens two-shot. Yoko pays for books that Hajime has kept for her, and as the couple move slightly, we can glimpse Hajime’s dog in the background, a bit of characterization for him. She moves aside to let us see it, then shifts back to allow us to concentrate on their dialogue.

This dynamic blocking and revealing of elements, characteristic of Hou’s staging, shapes the space as an unfolding spectacle, with new facets for us to discover. On the file cabinet on the right, splashes of light from the street outside come to fill the spot Yoko had occupied.

As the couple talk and listen to extracts of the composer’s piano music, illumination ripples over the shop interior, a reminder of the city turmoil that lies outside this cramped sanctuary, and Yoko leans back into the light.

The rest of the film will vary the locations to which we return—a coffee bar, Yoko’s apartment—with slight differences measuring the time that has passed. Likewise, the minimal, barely-started romance, crystallized in meetings over coffee, is nuanced by ever-changing patterns of light. We must watch the people, their gestures and slight displacements, as well as the space that they inhabit and the changing levels of illumination. We must attend to both the drama and its aura, both the café and the lumière.

Kiarostami calls Five Dedicated to Ozu “a real experimental film,” and he’s right: It could as easily have been called Five Dedicated to Warhol. Like American Structural Film, Five… asks us to sink into a fixed frame showing landscape views, and to concentrate on minutiae. A piece of wood, caught on the waves lapping to shore, breaks in two. One piece stays on the sand, while the other is carried out to sea. People stride or stroll along the sea front. Unidentifiable objects at the water’s edge shift uneasily and gradually become recognizable as dogs; but soon they dissolve into spindly black skeletons as the image brightens into dazzling abstraction. Ducks stroll through the shot, each one making a padding sound. Finally, the moon is reflected in a pond at night; the reflections quiver, broken by thunderclaps. For long periods the image is black and we must listen to birds, frogs, and some mysterious creatures.

“I think,” Kiarostami explains, “we should extract the values that are hidden in objects and expose them.” That sensitivity to just-noticeable differences that Hou achieves through the long take and intricate staging, Kiarostami achieves with the cooperation of nature. He is willing to trust to chance, a force that will collaborate with him and invent something he couldn’t conceive. Both filmmakers ask for a patience that most contemporary cinema cannot tolerate. In a general sense, Ozu becomes a model of a possible cinema—not through specific technical choices, as with Wang and Suo, but through an overall effect: a cinema delighting in the textures and weight of our world.

Still, something has been lost. To make us wait and watch today, the director must “gear us down” through long takes and stasis, through deferring, stretching, or purging narrative. Ozu, miraculously, solicits this heightened perception in less strenuous ways, through a cascade of cuts, rapid dialogue, and an engrossing story. The contemplative aspect of his cinema was simply another dimension of a work that incorporated dynamic storytelling. When cinema was newer, it seems, much was possible. Hou and Kiarostami, like Béla Tarr and a few others, have found in a slow pace and minimal drama today’s best analogues to the sharp-edged awareness of the world that came so spontaneously to Ozu in a more industrial mode of production. In a larger sense, though, Ozu and Hou would agree with what Kiarostami claims could be alternate titles for his film: Watch Again! Look Well! or simply Look!

Peter Bosma‘s report on last summer’s Film College can be read here. Thanks as well to Peter for a rare Ozu-related document. I’m grateful as well to Nicola Mazzanti, Gabrielle Claes, Stef Franck, and Bart Versteirt for making my stay in Antwerp so enjoyable, especially including the beer, moules, and frites. Earlier reports on the annual Summer Movie Camp can be read here and here and here.

Once more, thanks to Diane Arnaud and Mathias Lavin for having solicited the essay.

My quotations from Kiarostami come from the interview included in the Kimstim DVD of Five Dedicated to Ozu. On Hou’s staging principles, see Chapter 5 of my Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. I’ve discussed Hou’s staging on this site as well, here and here (with Ozu in the mix). Other entries on Ozu on the site can be found listed on the right. My book Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema is available as a free pdf file, with color illustrations, from the University of Michigan. As ever, thanks to Markus Nornes for making the book available in this format.

Finally, some years ago Lorenzo J. Torres Hortelano, author of a book-length study of Late Spring, wrote to tell me that the Noh play performed in Late Spring is Kakitsubata, not the one I had claimed. I found that he was correct, but had no way to change the book’s mention of it. Seeing Late Spring again last summer, I was reminded of Prof. Torres Hortelano’s message and now want to call readers’ attention to my error in the book. Prof. Torres Hortelano is also the author of The Directory of World Cinema: Spain and World Cinema Locations: Madrid. I thank him for the correction.

Master shots: On the set of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s THE ASSASSIN

Hou Hsiao-hsien oversees set details for The Assassin.

DB here:

For many years now, contemporary Chinese cinema has found success with costume action pictures like Red Cliff and Painted Skin: The Resurrection. Even prestige arthouse directors got into the act. Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) and Zhang Yimou’s Hero (2002) made the popular wuxia (martial chivalry) film respectable, and now we’re about to see several more examples.

Wong Kar-wai, who already found festival and arthouse recognition with Ashes of Time (1994) is (apparently) finally finishing The Grandmaster, a tale centered on Bruce Lee’s teacher Ip Man. Jia Zhang-ke, whose demanding, slowly-paced films Platform and The World got scant distribution in the US, is making a wuxia. Even more surprising is the fact that Hou Hsiao-hsien, master of the gradually unfolding long take, has turned his attention to martial arts. The Assassin, Hou’s first film in several years, is currently shooting in Taiwan.

James Udden is the author of the most comprehensive and authoritative book on Hou, No Man an Island: The Cinema of Hou Hsiao-hsien. For that project he interviewed Hou many times. Jim’s new project, a historical study of how Taiwanese and Iranian cinema became central to world film culture, compelled him to revisit Hou in December. “Hou’s screenwriter, Chu Tian-wen, informed me that if any interview were to happen before I left, it would have to happen on the set itself — if I did not mind. How could I refuse?” Jim has kindly chronicled his visit in the guest blog below, one mixing information with the unabashed admiration of the true fan.

Hou after Hu

Made in Taiwan: A Touch of Zen (King Hu, 1971).

“The first day of a costume picture always goes like this,” Hou Hsiao-hsien remarked to me. It was Assassin’s first day of shooting in Taiwan. The actors had been on call for make-up since 6:30 am were ready to go by 8:00. Now it was late in the morning and the camera had yet to roll. Slowly some of the actors made their way from the dressing into the open air, lounging around in their Tang-dynasty garb, waiting. Shu Qi, the Taiwanese star who launched her career in Hong Kong and has now gained wide exposure (If You Are the One, Millennium Mambo, The Transporter), is among Hou’s cast, and she walked onto the set briefly to inspect something.

Hou made it sound like he had done all this before. And it’s true that he has been at his best with historical material, not contemporary subject matter. Yet never before has Hou gone this far back into the past. Flowers of Shanghai was set in the late 19th century, but this film is set in the 9th century during the Tang dynasty, generally considered the peak of Chinese civilization.

More striking, The Assassin is a wuxia film. The outstanding figure in this genre’s rich history was King Hu, who revolutionized the wuxia in the 1960s and 1970s. A mainland émigré director who began directing in Hong Kong, Hu shot his best work in Taiwan and is a towering figure in that nation’s film history. He was known for his passionate authenticity in costume and settings, but also for his eccentric editing techniques, sometimes involving shots that last a mere fraction of a second.

Hou seeks authenticity no less fervently than Hu, but in terms of editing, he has been the older director’s polar opposite. A cut is rare in any Hou film. Often the shots last on average well over a minute, with Flowers of Shanghai averaging close to three minutes per shot. A year ago I asked Hou if the wuxia tradition would force him to abandon his signature long take. His answer was typical: “ I won’t know the answer to that until I actually get on the set.”

That’s where my visit came in. Hou and his crew had just returned from shooting scenes in mainland China. Now they were starting to film on the lot of the Central Motion Picture Corporation, the government-sponsored production facility that had given birth to the Taiwanese New Cinema of the 1980s.

Many know Hou’s work best through Café Lumière (2003) and The Flight of the Red Balloon (2008), both of which got fairly wide distribution in the West. However, Hou’s lasting reputation as a master is built largely on two things: the remarkable string of films he made in the 1980s as part of the Taiwanese New Cinema trend, and his later works that delve into the historical past, most of all City of Sadness (1989), The Puppetmaster (1993) and Flowers of Shanghai (1998). In these films, Hou explored the subtleties and complexities of mise-en-scène to an extent almost without parallel save for Kenji Mizoguchi. He also explored historical issues in ways almost without precedent. City of Sadness, in particular, gave a human face to a period of Taiwanese history that had long been kept in darkness.

How, through what concrete production decisions, did Hou achieve his lingering, riveting scenes—solemn long takes capturing the textures and tempos of the past? My 2009 book had to rely on secondary reports and my interviews with Hou and his collaborators. Now for the first time, I could observe firsthand.

Admittedly, during my visit I got only a snapshot of the production process. After a prolonged period of financing and preproduction, The Assassin will be shot over several months in China, Taiwan and Japan. According to Hou’s team, it will not be released until 2014. Still, two days on a set did confirm some things about Hou’s creative process, while also leaving some lingering hints of what this major project will be like.

Meticulous mise-en-scène

Sound designer Tu Tu-chih and director of photography Mark Lee Ping-bin.

In my book on Hou, I argued that only in Taiwan could Hou have had the career he had. This is not merely due to the particular set of historical circumstances and institutional pressures and opportunities. It is also because he was fortunate to find a creative team that has sustained his vision.

Prominent members include Mark Lee Ping-bin, the director of photography, and Tu Tu-chih, the sound designer. For Lee and Tu, shooting on the CMPC lot must have seemed like a homecoming, since both had learned their craft at this same studio in the early 1980s. Since then they have become arguably among the best of their respective fields in Asia, if not the world. Then there’s the remarkable production designer, Huang Wen-ying, who has worked with Hou since 1995 and who also is Hou’s main producer. For her this is clearly a dream project. Seeing this calm, soft-spoken yet efficient crew at work in tandem was unforgettable: they seemed to be working hard and meditating at the same time.

Years ago Hou said in an interview that perhaps he is too meticulous when it comes to mise-en-scène. This clearly has not changed. On the first day the camera was not yet on the set. Overheard snippets of Hou’s extended discussions with Huang Wen-ying, Mark Lee and others, gave the impression initially that he was going to shoot an interior scene one way, then another, only by the end of the evening to lead me to believe it had changed once again. Then on the second day, the first day of actual shooting, I returned in the morning to discover that the scene was covered from yet another angle.

Throughout that morning, that single setup underwent three more metamorphoses. Hou and his colleagues tinkered with the set and props so extensively that they broke for lunch before actually shooting — this despite the actors all being on call since around 6:30 am. Not bounded by the union rules typical on a Hollywood set, Hou at times was directly involved in adjusting several minute details. Hou is as meticulous as ever.

Hou never uses storyboards or shot lists. He does not even write out dialogue beforehand for the actors. His scenes have always grown out of the specifics of a setting—usually real locations that spark his imaginative staging and lighting. His modus operandi is to then respond directly to the atmosphere he finds himself in, no matter how long that takes. Everybody who works for him seems to understand this.

Now he had plenty of atmosphere to inspire him. Since original Tang-dynasty buildings are difficult to come by, two large, full-scale structures were being erected from scratch. These were solid buildings that I suspect will be worth a lot of money someday, and they were so large that the CMPC lot could barely contain them.

In the building that was finished, what struck me was the craftsmanship. From the hardwood floors to the intricate slatted, lattice room dividers, the woodwork in the finished structure was immaculate down to the details. Even the tiniest props, including flowers, were real, and breathtaking. Nearby in the production office was evidence of the exhaustive historical research behind this. Drawings and blueprints were to be found among hundreds of over-sized books on Chinese art and architecture.

Although the intricate sets for Flowers of Shanghai had been made in Taiwan in the later 1990s, Huang Wen-ying hired Vietnamese woodworkers to craft them. She claimed they would give slight “French” flavor to the set, evoking a strain of Chinese architecture particular to a foreign concession. I asked if this was the case this time. She laughed, “No, this time it is all ‘Made in Taiwan.’” I sensed some real pride in that statement, and for good reason.

Here lies the answer why this project has taken so long. Last year in Japan, Hou told me that some constraints were financial. The budget, currently reported at between US$12 and 14.5 million, had to be raised from various sources. Above all, though, it took time for Hou’s team to master all of the period details of the Tang dynasty. When it comes to mise-en-scène, no stone is left unturned. In fact, just about every stone, and everything else, is at some point toyed with by Hou himself.

Brushwork, not ballpoint

Crew and Hou with producer and production designer Huang Wen-ying.

Lighting is often the most time-consuming aspect of a film shoot, and you’d expect it to be particularly prolonged on a Hou project. Anyone who has seen either The Puppetmaster or Flowers of Shanghai on the big screen knows the supple gradations of light and shadows typical of a Hou shot. Yet back in 2005, Huang Wen-ying told me that Mark Lee works rather quickly to set up his lighting schemes. I found that almost incredible. Now I know it’s true.

Of all the changes that occurred on the first morning of actual shooting I saw, very few involved the lighting. The illumination was pretty much all set up by the time I arrived around 8:30. Over the course of the morning, only one lighting instrument was added, another was adjusted slightly, and a flag was added to one side.

For the most part Lee had to consult the continuity person about all the subtle changes occurring on the set. Over the course of the morning, Hou and crew dramatically changed the backgrounds of the shot. They hung a new gossamer cloth, added a folding screen revamped with gold leaf, and hoisted a leafless tree that would be visible in the distance. In the picture below you can see the second building under construction.

Lee would observe all these changes and would then confer with Hou as to how things would look on camera. At one point Lee was crouched with the continuity person, pointing at some detail for her to examine from a particular angle. She jotted points down in her large notebook.

In all his films for Hou, Lee’s exceptionally low lighting levels and deep, layered shadow areas would give even Gordon Willis a run for his money. Lee’s subtle lighting has always registered magnificently on film. Accordingly, The Assassin is being shot entirely on Kodak stock, even though digital would be somewhat cheaper. “To shoot on digital instead of film stock,” Lee explains, “is like being asked to paint with a ball-point pen instead of a brush.” No digital work will be done until post-production. I suspect that so long as there is some film stock to be found anywhere, at whatever cost, a Hou film will use it.

Back to basics?

Now that Hou has been on the set, what clues do we have to the result? What will a Hou wuxia film look like?

It’s of course too soon to say, but I did see signs that Hou wants to return to basics. Up to 1993 he notoriously executed long takes with little to no camera movement. Since then his camera has become very mobile — perhaps most notably in the endlessly arcing camera of Flowers of Shanghai. But what I saw in the Assassin shoot was a camera set only on a tripod, not a dolly, and placed at a considerable distance. The arrangement didn’t permit any movements except perhaps some pans or tilts for reframing.

I venture this guess: this will be a Hou film first, and a wuxia film a distant second. It will likely be a wuxia film unlike any other.

On that second day, I had to bid my goodbye to Hou before he had even started shooting. It should have been disappointing to not actually see Hou say “action” or “cut.” Yet this could not be further from the truth. First, I did get my interview late on the first day, fittingly on the CMPC lot. Second, I saw and heard much more than I could have ever expected. When I left America for Taipei, the prospect of being on Hou’s set was the furthest thing from my mind. I came home feeling like the luckiest guy in the world.

More background on Hou’s Assassin project can be found at Film Business Asia and Screen Daily. I discuss principles of Hou’s staging in Chapter 5 of Figures Traced in Light and on this site, in a supplementary essay on his early work and in this blog entry.

Our previous guest post was Tim Smith’s perennially popular “Watching you watch THERE WILL BE BLOOD.”

Hou Hsiao-hsien, James Udden, and Hou’s screenwriter and long-time collaborator Chu Tian-wen; Japan, 2011.

P. S. 7 January 2013: Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster made its censorship deadline and was screened in Beijing. Thanks to Ray Pride and Movie City News curated headlines for the link.

P. P. S. 8 January 2013: James Marsh has a rapturous early review of The Grandmaster at twitchfilm.

P. P. S. 8 January 2013, later: Maggie Lee provides an equally enthralled review in Variety.

P.P.P.S. 16 January 2014: Shooting on The Assassin is said to be wrapped. See Stephen Cremin at Film Business Asia.