Archive for the 'Directors: Hou Hsiao-hsien' Category

Good and good for you

Late Autumn (Ozu Yasujiro, 1960).

DB here:

Manohla Dargis of the New York Times has just written a piece that refers to some ideas that have appeared on this site. If you see the article online, you’ll find the links to appropriate entries, but if you’ve come here after reading the paper edition of the Times, you can find the Tim Smith essay she cites here. It is a remarkable piece of work, and it’s gratifying that Dargis has called attention to it. (Tim’s video experiments have received many hundreds of thousands of downloads already.) My table-setting entry, on task-driven looking, is here.

The backstory is simple. On this site in 2008, I took a slow, unemphatic scene from There Will Be Blood as an example of how a director can subtly guide our attention without cutting, camera movement, or auditory underlining. My analysis was guided by recognition of my own responses and some knowledge of traditions of cinematic staging. Tim, in his turn, used the tools of modern perceptual research to show that we can gain firmer knowledge of directorial craft. By tracking viewers’ eye-scanning, Tim demonstrates vividly that filmmakers can shape our experience of the action on a second-by-second basis. This not only helps us understand how we grasp images. It shows that humanistic inquiry and psychological research can collaborate.

Why so unserious?

Late Spring (Ozu Yasujiro, 1949).

Those who navigate Internet eddies and flows know that dozens of responses have swirled around Dan Kois’ “Eating Your Cultural Vegetables.” Kois wants to like long, slow movies, but after trying for years, he has found that he just can’t enjoy many of them. He can mimic, even anticipate, the judgments of those who do, but in his heart he finds most of the celebrated films boring. He’s now decided to give in to his impulse and declare that he needn’t pretend to enjoy Tarkovsky or Hou Hsiao-hsien:

As I get older, I find I’m suffering from a kind of culture fatigue and have less interest in eating my cultural vegetables, no matter how good they may be for me.

As one man’s confession of guilt and fatigue, this is doubtless sincere, although its sideswiping putdowns of viewers who praise such movies suggest more calculation than humility. Still, this cry from the heart has broader implications, as many Net writers have discussed. Kois’ complaint elicited not one but two responses from the New York Times film critics A. O. Scott and Manohla Dargis. For one thing, Kois’ essay seems to offer aid and comfort to people who are afraid to try something different. Indeed, it lets them feel superior to the phonies who claim to like such films. Moreover, Kois justifies the most superficial response a moviegoer can make. Simply shrugging off a film by saying, “It’s boring!” is about as uninformative a response as saying, “It’s interesting!” And one should always be suspicious of somebody, in the name of debunkery, telling us that we shouldn’t bother to know something.

Kois’ piece exploits the special status that film enjoys in today’s culture. High and low mingle. Because movies are so accessible, and Hollywood movies are so eager to give us what somebody has decided that we want, coterie tastes are dismissed as snobbism. Things seem different in other arts. Would the Times publish a piece in which someone confessed to finding Tarkovsky’s contemporary, the Soviet composer Sofia Gubaidulina, boring? No, because to talk about her is already to enter a restricted and high-level conversation. It goes without saying that a great many listeners would be bored by her music, but who cares what non-experts think about a modern composer? Film, however, is a free-fire zone; anybody’s opinion is worth a public hearing.

I’ve kept out of the fracas because I thought Kois’ piece was silly-season fluff. Of course I wrote my own replies in my head, such as We used to have a name for this: Philistinism. I also thought that the essay operated in bad faith. Kois wasn’t as apologetic as he tried to seem. He claims humility (he “yearns…to experience culture at a more elevated level”) when really disdaining this area of cinema and considering the people who claim to enjoy it mere poseurs. The exaggerations show, I think, that this is not a serious piece:

Surely there are die-hard Hou Hsiao-hsien fans out there who grit their teeth every time a new Pixar movie comes out.

Surely not.

Still, Kois’ complaint touches on something important about film history. We have a polarized film culture: fast, aggressive cinema for the mass market and slow, more austere cinema for festivals and arthouses. That’s not to say that every foreign film is the seven-and-a-half hour Sátántangó, only that demanding works like Tarr’s find their homes in museums, cinematheques, and other specialized venues. Interestingly for Kois’ case, many of the most valuable movies in this vein don’t get any commercial distribution. The major works of Hou, Tarr, and others didn’t play the US theatre market. Sátántangó is just coming out on DVD here, nearly twenty years after its original appearance. Most of us can’t get access to the most vitamin-rich cultural vegetables, and they’re in no danger of overrunning our diet.

The race is to the slowest

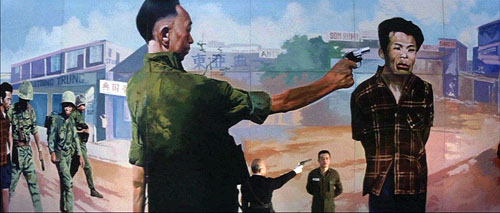

City of Sadness (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1989).

For the historian, the polarization between fast pop movies and slow festival films asks to be explained. My take goes roughly this way.

From the 1940s through the 1960s, certain directors developed a new approach to telling stories. Antonioni, Dreyer, Bergman, and a few others opted for a style that relied on slower pacing and even “dead moments” that seemed to halt the narrative altogether. “Dedramatization,” it was sometimes called, and many rightly considered it a powerful innovation in the history of film as an art. But these films did get a purchase on the international movie market, often for other reasons (sex in Antonioni and Bergman, religiosity in Dreyer). They also came along at a time when there was a niche audience eager to have new cinematic experiences. (On this period see Tino Balio’s Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens.)

But artists being artists, competition grew up. The long take, for instance, got longer and more virtuosic. Miklós Jancsó, shamefully ignored today, made a series of pageants of Hungarian history in superbly sustained, intricate camera movements; some of his films have only twelve shots. But his films are sumptuous compared to what we found elsewhere. From the late 1960s through the 1970s, it seems, a new generation of filmmakers competed to make ever more austere films. They often kept the camera fixed, framed the action at a distance, and sustained the shot for many minutes. The works of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet are the high-water marks of this trend, but there were also Chantal Akerman, Theo Angelopoulos, and even Rainer Werner Fassbinder (Katzelmacher) and Wim Wenders (Kings of the Road). Werner Herzog’s successful career as a documentarist has perhaps let people forget that he once made very slow and demanding films like Fata Morgana; his Heart of Glass, screened in US arthouses in the 1970s, would surely not find a distributor today.

From a marketing standpoint, the avant-garde overplayed its hand. The new austerity came along just when Spielberg and Lucas were reinventing Hollywood. As movies got faster and louder, long-take minimalism looked perversely ascetic. Some of the directors, like Straub and Huillet, remained loyal to their project; others crossed over. It is quite a shift from Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), a 201-minute film mostly about housework, to the musical The Golden Eighties (1986) and A Couch in New York (1996). Likewise with Wenders’ Summer in the City (1970) and Wings of Desire (1987). I happen to admire both strains in these directors’ works, but there’s no doubt which is the more audience-friendly.

Today, directors who persist in long-take, slowly-paced storytelling are aiming chiefly at the festival market, which means that most of their films will be shown theatrically only, to be blunt, in France. But some of the greatest directors of our time, notably Hou Hsiao-hsien, Edward Yang, and Abbas Kiarostami, have done their best work in this mode. The US arthouse market has taken decades to discover them, through more accessible works like Flight of the Red Balloon, Yi Yi, and Certified Copy. Kois confesses to loving Yi Yi, so I’d urge him to look at Yang’s Terrorizers and A Brighter Summer Day, more rigorous but no less gripping films, though they lack the traditional arthouse bait of a charming child. Hou’s Red Balloon also has a cute kid and refers back to an arthouse classic, while Kiarostami, not normally given to couples and romances, offers us in Certified Copy a pleasantly teasing take on Antonioni and Resnais.

Minimalism of the 1970s variety got revived by 1980s American indies, notably Jim Jarmusch, but with more entertainment value. In later years he too crossed over stylistically; however unpredictable the plot maneuvers of Ghost Dog and Broken Flowers, they lack the long takes and open-ended unfolding of time we find in Stranger than Paradise. Even Kelly Reichardt, one of Kois’ targets, doesn’t give us anything like the severity of the 1970s generation. That makes the “purer” films from overseas that persist in this tradition even more off-putting. If Kois can’t take Meek’s Cutoff, as he claims, he’d find Hong Sangsoo (Oki’s Movie) or Liu Jiayin (Oxhide and Oxhide II) cinematic chloroform.

So Kois may assume that “boring” films have persisted in today’s film culture because of snobbism, but there are deeper reasons. The competition among filmmakers to push an aesthetic horizon further, the narrowing of audience tastes, the search for a budget-appropriate niche that could stand in opposition to the visual spectacle of the New Hollywood–these seem to me important factors in making slow movies a ghetto for cinephiles.

Why shouldn’t people follow Kois in giving up their vegetables? No reason, except that they’re missing some worthwhile cinematic experiences. Not all austere movies are good, but viewers who want to expand their cinematic horizons should consider the possibility of learning to look at certain movies differently. Kois can’t see that; he thinks that people who like the movies that bore him are usually phonies. But I believe that some of those admirers have developed a repertory of viewing habits that adjust to different cinematic traditions. If you can like both Stravinsky and rock and roll, why can’t you like Hou and Spielberg?

Look again, closer

Voyage to Cythera (Theo Angelopoulos, 1984).

This is the prospect opened up by Dargis’ latest article. She suggests that Kois’ response isn’t wholly based on taste. It may stem from literally not knowing how to look at certain kinds of movies.

Kois’ article treats most defenses of slow films as a matter of hand-waving and you-see-it-or-you-don’t attitudinizing. Again, he has a point: Those reactions are common, I think. The fact that cinephiles must face is that this sort of film is very difficult to talk about. We can point out the creative choices in Hollywood because narrative in some degree drives everything we see and hear. But when narrative relaxes, most viewers don’t know what to look or listen for.

The problem has haunted me for decades, ever since the 1970s when I took an interest in Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer, and Mizoguchi–all filmmakers felt, at the time, to be slow. I failed to come to grips with the problem in my 1981 book on Dreyer; I even anticipated Kois in calling Gertrud (another item that would never grace theatre screens today) boring–but I took that to be a good thing, as a challenge to conventional viewing habits.

What can I say? I was young. Since then, I think I’ve come up with better ways of talking about the other directors I mentioned, as well as some in their camp, such as Angelopoulos and Hou and Tarr. A lot of my answer comes down to the way, pace Dargis and Smith, they structure our attention.

My arguments are set out in the places I mention in the tailpiece of this entry. In brief, these filmmakers become engaging, even entertaining, when we realize that they are to some extent shifting our involvement from characters and situations to the manner of presentation. Not narrative but narration is what engages us. And we need, as Dargis points out, some schemas for grasping these alternative patterns. We have robust and refined schemas for following a story, but grasping the dynamics of narration, the how as well as the what, takes more practice, and perhaps some instruction from critics.

The process is like taking in an opera on two levels: following the stage action but also registering the patterns, the emotional highs and lows, of the music that accompanies–and sometimes overwhelms–it. Let Papagena and Papageno stammer each one’s name again and again. The repetition isn’t needed for the drama, but it’s thrilling on sheerly musical grounds.

Now imagine that sort of development transposed to cinema, in which we can appreciate, at one and the same time, not only the story’s unfolding but the patterns that present it. The supreme master of this possibility, I think, is Ozu, perhaps cinema’s Mozart. But you can find the same qualities in more somber key elsewhere. For example, in watching Angelpoulos’ Voyage to Cythera, I think that you have to be prepared to see the arrival of track workers in yellow slickers, visible through the speckled window pane in the shot above, as a kind of visual epiphany, the quiet equivalent of a stunt in a summer tentpole picture.

Given a narrative mandate, we’re on the lookout for pictorial factors that affect the dramatic situation. But when narrative slows, other things, maybe not of narrative moment, pop out, like the yellow-garbed train workers on their handcar. At such moments, it’s not that our eyes roam around aimlessly; it’s that the director guides us in a different way, toward a visual search that isn’t wholly driven by plot considerations. Here’s a shot from Ozu’s End of Summer (1961).

The principal action is a party of young people singing. But the faces are no more important than the gleaming drinks on the table, a little suite of colors and shapes that become fascinating in themselves. (For instance, several of the liquids and bottle labels sit along the same horizon line, regardless of how far the drinks are from us.) You don’t discover this half-gag, half-still-life by groping: Ozu has lit it and composed it so that you’re invited to discover it. He has found a way to activate what in most movies would be filler material. And if you think that noticing colors and shapes on the tabletop is just trivial, consider that we enjoy staring at the same sorts of patterns in an abstract Kandinsky. Or is he cultural roughage too?

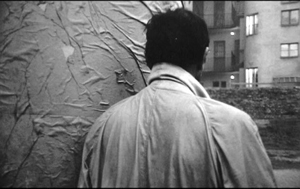

In an Ozu film, even though he cuts rather fast, we’re given time to see everything. But this isn’t random rummaging. It’s visual exploration guided by Ozu’s decisions about composition, lighting, and color. Something similar, I think, is going on with Tarr, although there it’s more a matter of texture and tactile qualities. His people shamble through mud, oily puddles, dusty corners, and tearing winds. In one shot of Damnation, a rain-soaked wall shrivels to match a wrinkled topcoat.

The story is still going forward, but by turning his protagonist from us and aligning him with the wall, Tarr has given his shot an extra layer of sensuous appeal. Try to remember the way any wall looked in Transformers 3, before it got blasted to rubble.

Slow movies let us look around, and good slow-movie makers give us something to see when we do. But what do we do when these accessory appeals don’t just accompany the narrative but swamp it? What if we lose track of the characters? The film may steer us to pictorial or auditory qualities that take over our perception.

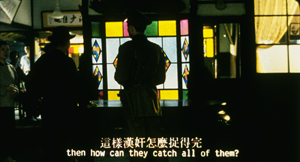

The authorities are looking for a man in the family in Hou’s City of Sadness, but you have to rely almost solely on dialogue to identify what’s going on and who’s speaking.

The sheer pictorial beauty of the shot becomes a sort of anti-narrative pretext. But if you’re alert, you won’t take the plot off the table, because at one crucial moment a figure flashes through the far left background, more or less fully lit, who may be the suspect the cops are seeking.

Sometimes you have to destroy narrative in order to save it.

Hou asks that we engage with his distant, fixed images in a complex way, being patient but vigilant, enjoying abstract geometry while also sustaining old-fashioned suspense. It’s this dynamic between story and style, fastening on plot elements but also discovering accessory pleasures and patterns, that I think constitutes one delight of the sort of films that Kois finds boring.

Add Bresson, Mizoguchi, Dreyer, Tarkovsky, and others to my list of directors whose very different styles invite us to explore what the rapid pace of most narrative cinema refuses to dwell upon. These filmmakers invite us to grasp the space and time of a scene in a fresh way. The details and dimensions of a world surge forward, not simply as a backdrop for characters hurtling toward a goal, but as something valuable in their own right. For some viewers, me included, they do more. They also ask you to transfer those viewing skills to life outside the theatre. They encourage you to find a new way to look at our world.

Not all slow, minimalist movies are good. That’s why I think critics are obliged to rebut Kois with careful analysis, not the gaseous generalities about sublimity and eternal mystery to which we too often resort. Digging deeper, we can not only answer skeptics but expand our understanding of how cinema works. These films have opened windows for many of us. Why should we keep them to ourselves?

First, thanks to Manohla Dargis for enjoyable correspondence about these issues.

Tim Smith’s blog, Continuity Boy, is a good way to keep up with his energetic and expanding research program.

Dargis mentions the invisible gorilla experiments of Chabris and Simons. I talk about their relevance to film here and here.

Kristin has written on comparable matters in Tati; she even wrote an essay on M. Hulot’s Holiday called “Boredom on the Beach.” (It and an essay on Play Time are in her book Breaking the Glass Armor.) Tati’s films, in their spasmodic pauses and shamelessly repeated or sustained gags, could also count as part of the postwar dedramatization trend.

My initial arguments about different registers of viewer perception and cognition were made in Narration in the Fiction Film (1985). My case for Ozu is in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, available online. More recently, I’ve become interested in cinematic staging and have concentrated on challenging directors like Mizoguchi, Angelopoulos, and Hou; see On the History of Film Style (1998) and Figures Traced in Light (2005). All of these “slow” filmmakers ask us to be sensitive to unusual sorts of narrative patterning, and some purely non-narrative patterning. More thoughts on these matters can be found in The Way Hollywood Tells It (20006) and Poetics of Cinema (20007).

On this site, you can find similar lines of argument, especially about Béla Tarr, Mizoguchi Kenji, and silent directors like Louis Feuillade, Victor Sjöström and some Danish creators. See director entries for Hong Sangsoo, Liu Jiayin, and others mentioned above. Later this month I hope to post a bit more about how directors guide our attention without recourse to fast-paced editing–before editing was really invented.

Sátántangó (Béla Tarr, 1994).

Picks from the pile

Or rather, two piles. One stack of consumer durables that I brought home from seven weeks in what we Americans call Yurrp, and another stack of things that came while I was gone.

DVDs of course stand out. Apart from items scooped up in Bologna, here are a few highlights. Some are quite old, some very recent, but all were new to me.

The Magnificent Ambersons, on a Region 2 disc from Montparnasse, in cooperation with Cahiers du cinéma. The squarish box houses a slim booklet, a remastered copy, and bonus documents: interviews with Bill Krohn and Jean Douchet, and a 51-minute conversation between Welles and Bogdanovich. Plus the original trailer.

Engineer Prite’s Project, Kuleshov’s first film from 1918. It’s from Absolut Medien in collaboration with Hyperkino, which we wrote about last year. German subtitles only. Comes with a 54-minute documentary by Semyon Raitburt on the Kuleshov effect.

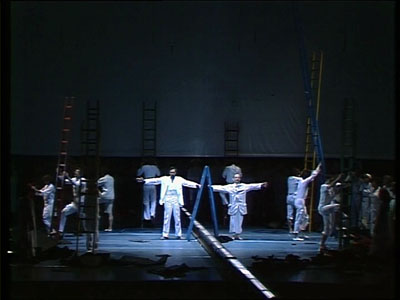

Another German release, but with English subs: Finally, the 1983 Stuttgart production of Philip Glass and Constance de Jong’s gorgeous Satyagraha. For once PoMo staging enhances the story. In the hammering opening of the second act, the mocking laughter of the South African whites comes from a vast row of beer swillers. The pre-HD imagery is a little soft, but my ancient Beta off-air copy can finally be laid to rest. From Arthaus Musik.

Absolut Medien also gives us The New Babylon, one of the greatest but least-known Soviet Montage films. The original Shostakovich score has been used, and the German reconstruction has English subtitles. Apparently a UK edition is on the way. The film is hard to cope with digitally: Lots of fog, smoke, and steam; diffuse photography; shots with significant action in out-of-focus planes. Still, it’s a big improvement on the bargain French edition in circulation. Tom Paulus, a real gentleman, surrendered the last copy in Bruges to me.

The venturesome French company Carlotta has launched an Oshima collection, though it doesn’t seem to appear on the Carlotta website! I found three must-have items at Fnac: A Treatise on Japanese Bawdy Songs, Japanese Summer: Double Suicide, and best of all Three Resurrected Drunkards. The last is a bizarre masterpiece mixing a boy band up with the Vietnam war and Japanese discrimination against Koreans. About 40 minutes in, Oshima provides the most anxiety-provoking reel change in cinema. All Region 2.

Now for some books and journals:

James Udden, one of my last dissertators before I retired, has written the first book-length study of Hou Hsiao-hsien in English. No Man an Island: The Cinema of Hou Hsiao-hsien puts Hou firmly in the context of Taiwanese film history and culture. It offers some provocative suggestions, particularly in arguing that it’s misleading to consider Hou an essentially Chinese director. Jim, who lived in Taiwan and speaks Mandarin, spent many years watching Chinese films from all eras, and he balances this breadth with close study of each Hou film. From Hong Kong University Press.

James Udden, one of my last dissertators before I retired, has written the first book-length study of Hou Hsiao-hsien in English. No Man an Island: The Cinema of Hou Hsiao-hsien puts Hou firmly in the context of Taiwanese film history and culture. It offers some provocative suggestions, particularly in arguing that it’s misleading to consider Hou an essentially Chinese director. Jim, who lived in Taiwan and speaks Mandarin, spent many years watching Chinese films from all eras, and he balances this breadth with close study of each Hou film. From Hong Kong University Press.

Eva Laass has just published a wide-ranging study of current narrative strategies in Broken Taboos, Subjective Truths: Forms and Functions of Unreliable Narration in Contemporary American Cinema. She examines Forrest Gump, Thank You for Smoking, Natural Born Killers, Fight Club, and other works in the light of several questions. What different forms of narrative unreliability can be distinguished? Why have unreliably narrated films become so popular in recent years? Which needs do they meet in American culture? Although available from Amazon.de, the book is in English.

I met Steven Jacobs, a brilliant young art historian with wide-ranging expertise, at the Bruges Zomerfilmcollege some years ago. This year he gave me a copy of his 2007 book, The Wrong House: The Architecture of Alfred Hitchcock. Drawing on research in production documents, it’s a careful and imaginative analysis of the master’s use of interior spaces, including discussion of his “staircase complex.” Steven has even reconstructed floor plans for some movies. He is interviewed about the book, in Dutch, here.

For Paolo Gioli admirers, the forty-fifth Pesaro festival catalogue should be welcome. A retrospective of Gioli films is accompanied by essays, an extensive interview with Giacomo Daniele Fragapane, and a detailed, annotated filmography. Everything is bilingual Italian/ English. You can download the catalogue as a pdf here. I hope to post my contribution, with some extra frames, on this site in the next month or so.

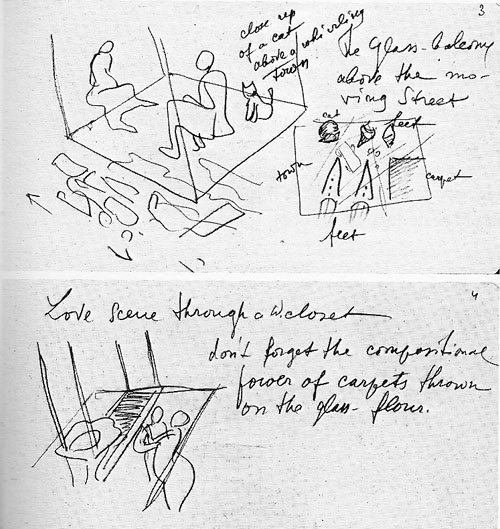

One of Eisenstein’s most ambitious projects was The Glass House (1927-1930). Inspired by skyscrapers, he envisaged a movie set in a high-rise apartment building of the future, with transparent walls and ceilings. He savored the idea of juxtaposing action in different layers (akin to the sequence in M. Giffard’s apartment in Tati’s Play Time). Some of the results can be seen surmounting this entry: a cat curled above a moving street, intertwined lovers seen through a bathroom floor. Another sketch shows a dying woman in the foreground and elevators carrying oblivious people past her.

The bold project is documented in a lovely French volume edited by Alexandre Laumonier and translated by Valérie Pozner and Michail Maiatsky. Glass House contains diary extracts, working notes, and sketches, all thoroughly annotated by François Albera. In a synoptic essay, Albera discusses the role of architecture in Eisenstein’s thinking.

Everyone seems to be talking about the roles of film festivals these days, and a current roundup of opinion can be found in the Cologne-based magazine Schnitt. The magazine is published in German, but for the festival symposium in issue 54, the editors provide English versions of essays by Marco Müller (Venice), Cameron Bailey (Toronto), and many other festmachers. Some radical ideas floating around here, including the suggestion by Lars Henrik Gass (Oberhausen) that subsidies for national film industries, and their festivals, may have to end. (His essay is available in English here.)

Everyone seems to be talking about the roles of film festivals these days, and a current roundup of opinion can be found in the Cologne-based magazine Schnitt. The magazine is published in German, but for the festival symposium in issue 54, the editors provide English versions of essays by Marco Müller (Venice), Cameron Bailey (Toronto), and many other festmachers. Some radical ideas floating around here, including the suggestion by Lars Henrik Gass (Oberhausen) that subsidies for national film industries, and their festivals, may have to end. (His essay is available in English here.)

In the wake of my homage to the Geneva Theatre/ Smith Opera House, Karen Colizzi Noonan kindly sent me some issues of Marquee, the journal of the Theatre Historical Society of America. Marquee is going strong after forty years, and it remains a lavish production, with big stills and in-depth research. The Society, which is currently updating the standard source book Great American Movie Theaters, holds an annual meeting that includes theatre tours. If you’re at all interested in American film history, you should visit the Society’s website.

There were other items on the two piles, but I have to go. My eyes and ears have some work to do. I’ll leave you with the most unexpected development, film-book-wise, I have encountered upon my return.

Three Resurrected Drunkards.