Archive for the 'Directors: Jackson' Category

Frodo lives! and so do his franchises

Given the saturation of fantasy, sci-fi and superhero films we experience today, not to mention how frequently we quote from Lord Of The Rings, it bears reminding now and again (not too obsessively, mind) just what a game changer Lord Of The Rings was.

Jordan Adcock

Kristin here:

A little over ten years ago, in April 0f 2006, I finished the manuscript of The Frodo Franchise: The Lord of the Rings and Modern Hollywood (University of California Press, 2007). Given that I had previously written books and essays on films by such auteurs as Sergei Eisenstein, Jacques Tati, Jean-Luc Godard, Jean Renoir, and Robert Bresson, those who knew my work were perhaps bemused by this change of direction.

I had decided to tackle this project, which proved to be an enormous but richly rewarding one, in 2002, after the release of the first part of The Lord of the Rings, The Fellowship of the Ring (December, 2001). Already it was apparent to me that Peter Jackson’s adaptation would be an enormously influential film, to the point where, whether or not one likes the movie itself, it would be among the most historically important films ever made. New Line used the internet to promote it at a time when it was still not common for a film to have its own studio-created website. The cooperation between the filmmakers and the video-game designers was unprecedented. The extended-version DVD releases, arriving only five years after the introduction of the format, had unique depth and breadth. The impact of its technical innovations, particularly in digital special effects and color grading, was enormous. The film’s success boosted the many independent producers around the world who had largely financed it. Not to mention the ways in which the movie transformed New Zealand through tourism, a small but sophisticated and thriving film industry, and a surge of national pride. The film and the franchise impacted the Hollywood industry in almost any way one could imagine.

In 2002, to believe all of this was going to happen and to commit to spending time, money, and effort in researching all these topics required something of a leap of faith. It was one I was confident in making. Uncharacteristically for a historian, I made some predictions about the lasting power of LOTR and its franchise. This risk was inevitable, given that I was writing about a lengthy ongoing event, one which clearly would last far into the future. The book begins: “The Lord of the Rings film franchise is not over, not will it be for years.” [p. XIII] Later I specified:

The franchise is not nearly over. Middle-earth-themed video games continue to appear. Additional licensed toys and collectible items are still being brought out. Fan activity remains lively in cyberspace and the real world. The phenomenon has reached into international culture in ways that go far beyond the commercial confines of the franchise. Politics, education sports, and religion all reflect the influences of the film. An extinct race of tiny people discovered on a Pacific island was instantly dubbed “hobbits” by headline writers and even the scientists who discovered them. [pp. 9-10]

I was reminded of these claims by two recent events. First, last week’s Comic-Con included, as usual, a Weta Workshop booth, and, as usual, several of its popular limited-edition collectible figures from LOTR were debuted there. Second, on June 23, Jordan Adcock posted an intriguing article, “Can fantasy films escape Lord of The Rings’ shadow?” on Den of Geek. Yes, thirteen years after the release of The Return of the King (December, 2003) and ten after I ended the coverage in my book, the franchise goes on, as does the influence of Peter Jackson’s film. The number of products and tie-ins is far smaller than at the height of the films’ releases, but it seems to have settled down to a steady flow.

This combination suggested that it is an opportune time to point out that this film is still influencing the fantasy genre–perhaps too greatly–and that its franchise, though reduced, rolls on. I don’t think I was being terribly prescient in predicting all this, but it’s a bit of a relief to find out that I was right.

Collectibles, video-games, and more

Fans and collectors continue to purchase LOTR studio-licensed and fan-generated items of all sorts. Some of these are from the era of the film’s release, and some are new. A search on “Lord of the Rings” in the collectibles category on eBay generates 13,476 items, only a small percentage of which are related to products relating to the novel’s franchise or that of the 1978 Ralph Bakshi film. Some of the upscale and/or rare items sell for hundreds of dollars. There is still a demand.

In my book I made no effort to catalog all the products made to that point. In fact, I don’t think it would have been possible, unless I had had access to New Line’s records of its licensing contracts. Besides, that wasn’t part of the purpose of the book. In discussing licensed products, I was more interested in digital technology had affected what sorts of items were made. There was the motion-capture for the video games, for example. There were the DVDs–a format introduced as recently as 1997, the year when Miramax signed a contract with Saul Zaentz, thus obtaining the rights for Peter Jackson to make LOTR. (In Chapter 7 I give a little history of the introduction of DVDs and the part LOTR played in the studios efforts to move from rentals to purchases of home video.) There was the facial scanning of the actors for the action figures. There was, however, a dizzying array of hundreds, or more likely thousands of other, more conventional products licensed around the world. I once bought a lottery ticket in London not because I hoped to win a prize but because it was LOTR-themed and had a picture of Elijah Wood as Frodo on it.

Here I just want to give a few examples to show that New Line-licensed products are continuing to appear. I won’t include any Hobbit-based licensed products except in passing. Obviously the second trio of films extended the original franchise, but here I am only concerned with the longevity of the LOTR’s ability to generate more products and to influence the fantasy genre.

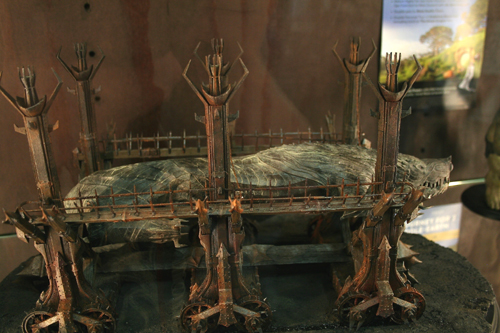

I mentioned the Weta Workshop collectible figures, which continue to be among the most popular products among devoted fans. The main fan-site, TheOneRing.net (Disclosure: I am a member of the staff) annually posts a video tour of the Weta booth at Comic-Con. This year’s video, Collecting the Precious-Weta Workshop Comic-Con 2016 Booth Tour (by TORn staffer Josh Long, about 18 minutes), lovingly moves over the glass cases containing the new items, including statues of Lurtz and Boromir enacting the latter’s death scene late in Fellowship. There’s also a big piece with the battering-ram, Grond. (I have a sentimental attachment to Grond, since it was the only one of the large miniatures made by Weta Workshop that I saw during my 2003 tour of facilities at Stone Street Studios. See above for the miniature version of the minature.) In watching the video, I didn’t keep count, but although over half of the figures are from The Hobbit, there are quite a few LOTR ones as well.

I have lost track of all the Middle-earth-based video games that have appeared since the last one the book covered: “The Battle for Middle-earth” (released on December 6, 2004, and, as far as I can tell, still in print). It was the fourth, and the first to concentrate on battles and strategies rather than on the plot of the movies themselves. By now here have been 22 of them, according to the “Middle-earth in video games” entry on Wikipedia, the most recent being “Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor” (2014). Its action takes place between that of The Hobbit and of LOTR. The total given above includes “Lego The Lord of the Rings.”

Lest one think that the only products are expensive ones aimed at the most enthusiastic core fans and dedicated gamers, I should mention that there are less pricey items. Inevitably, given the recent fad for adult coloring-books, there is one based on LOTR, list price $15.99, released May 31 of this year. (See top.) I expect a Hobbit one will follow. Warner Bros. has continued to bring out a film-based LOTR wall calendar each year. You can already pre-order the 2017 one, due out on September 15.

The posthumous career of J. R. R. Tolkien

As I pointed out in The Frodo Franchise, there has long been a franchise based around Tolkien’s original novels, which I discussed briefly. Lest we think that the film franchise must inevitably fade, it is worth noting that HarperCollins, Tolkien’s publisher, has kept the novel-based one going for decades after the author’s 1973 death.

There are, for example, numerous games like “The Lord of the Rings: The Card Game” (judging from the comments on Amazon, this must have appeared in 2013). HarperCollins publishes its own calendar, based on Tolkien’s work as a whole rather than just LOTR. Many do center on LOTR, often featuring the work of a major Tolkien illustrator. With The Hobbit having been published in 1937, however, its 80th Anniversary is being featured for 2017, also available for pre-order.

The Tolkien-based franchise items tend to be somewhat more dignified than many of the film-derived ones. This is especially true given that many of the products consist of new or reissued works by Tolkien.

Non-fans of the books may not be aware that the Tolkien publishing juggernaut goes on as well. These are not all cobbled-together variants of existing Tolkien works. Actual new texts by him appear at intervals as his son Christopher Tolkien slowly releases editions of unfinished manuscripts by his father. By now Tolkien has far more literary works published posthumously than during his lifetime, even if one does not count Christopher’s epic assemblage of the drafts for LOTR in the twelve thick volumes of “The History of Middle-earth.” (Tolkien was a notorious non-finisher and left behind many incomplete academic manuscripts as well.)

Earlier this year there appeared The Story of Kullervo, retold by Tolkien from the Finnish epic The Kalevala. Amazingly, a second is due this year: The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun (out November 3). These poems, both with historical and formal analysis by notable Tolkien scholar Verlyn Fleiger, are not for the broad audience of Tolkien fans, but they obviously generate enough interest among core devotees and scholars to be worth publishing.

Tolkien was a talented amateur artist who occasionally illustrated his own work, most notably The Hobbit, and drew many sketches and maps to help him visualize Middle-earth. The ones for LOTR were published last October as The Art of The Lord of the Rings.

There are also, of course, as many different new editions of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings as the publishers can possibly justify in some fashion. Every now and then a “gift edition” with new illustrations appears. The one tied to the 80th anniversary of The Hobbit is a version illustrated by Jemima Catlin, announced for early next year. On September 22, the long-delayed facsimile of the first edition of The Hobbit is due to appear. (As I recall, it was originally supposed to be part of the 75th anniversary celebration.) This facsimile is of considerable interest to fans and scholars alike, since Tolkien revised portions of the original tale. Most notably, it contains a very different version of the famous riddles scene between Bilbo and Gollum, in which the Ring is introduced in a way completely incompatible with the premises concerning it established later by Tolkien in LOTR.

Even bits of film and audio recordings of Tolkien occasionally resurface. On August 6 at 8 pm London time, BBC Radio 4 will broadcast of “Tolkien: The Lost Recordings.” This program is based around some newly rediscovered audiotapes of outtakes from the BBC’s 1968 documentary, Tolkien in Oxford.

Fantastic stories and where to find them

Jordan Adcock’s “Can fantasy films escape Lord of the Rings‘ shadow?” was inspired by the release and failure of Warcraft: The Beginning. He uses the occasion both to explain why the Jackson’s LOTR trilogy so dominates conceptions of filmic fantasy and to suggest how Hollywood might make films that won’t be compared to it and inevitably found wanting.

Alcock largely credits the film’s lingering impact to the depth and plausibility of its visual rendering of Tolkien’s invented world, Middle-earth. He spends some time describing how Tolkien, with his brilliant command of history and ancient languages, managed across his lifetime to develop a consistent, appealing continent with different races, languages, countries, and landscapes, as well as its own history. Jackson’s film manages to create “a fantasy world with both digitally-aided grandeur and a practical, lived-in feel […] Jackson recreates Tolkien’s precision of time and setting.”

Certainly the film’s production design, its New Zealand locations, and its cinematography creates a Middle-earth that impressed even the film’s harshest critics. Its treatment of the plot and characters, though less successful overall, stuck far closer to the novel than did the more recent Hobbit trilogy. (See here, here, here, and here for my comments on the strengths and failures of the three parts of the latter.) Long-time fans like me forgave LOTR a lot, including added schoolboy humor and Arwen supposedly dying, for the visuals and the music and the near-perfect casting. And, as David, who has never read Tolkien, remarked to me when we walked out of theater after his first viewing of Fellowship, “Well, it’s better than Star Wars!” Within the fantasy genre, LOTR probably is the finest achievement in modern American moviemaking. It is no wonder that subsequent films, even twelve years later, are seen by critics either as pale imitations of it or as failed attempts to create a different but equally dense and coherent fantastical world.

Alcock’s hints at how filmmakers might avoid such problems, but in the process he also admits that his solutions are nearly impossible to achieve. First, he points out that the fantasy world need not be created across several decades–and yet if it isn’t, it will not measure up.

Authors and screenwriters don’t have to go away and devote the rest of their lives [to] creating a universe as large and self-sustaining as Tolkien’s, but against such a brilliant creation done such justice, all other attempts feel a little short-termist.

I assume “done such justice” refers to Jackson’s film, the implication being that the screenwriters need not necessarily invent an entire world but might find it ready-made in a literary work. The fact that the Harry Potter serial achieved such fierce fan devotion and high BO seems to confirm that. Though not an impressive stylist, J. K. Rowling shares with Tolkien a remarkable imagination when it comes to making the Wizarding World vivid to readers. She also anchors it just enough in the real world to make it appealing and easy to relate to. Her novels bear almost no resemblance to LOTR, apart from the fact that the Dementors seem derived from the Black Riders. To a considerable extent, the strongest aspects of the film adaptation’s version of Rowling’s world parallels that of LOTR, superb design and excellent casting being perhaps foremost among them.

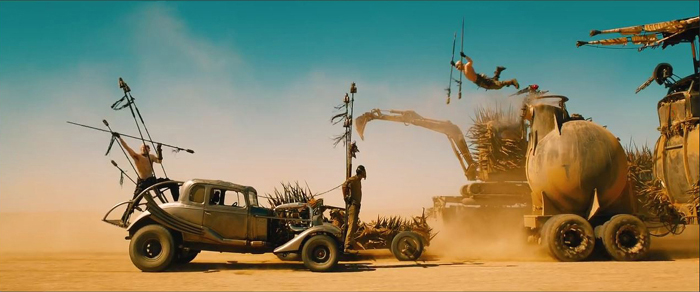

Creating an original screenplay with a similarly original world, however, seems an extremely tall order. To be sure, it is not impossible. George Miller’s first Mad Max film was not a fantasy but an action-revenge film shot on the cheap with an unknown star-to-be. Its success, probably based on skillful direction and an appealing actor, allowed Miller to transform Max’s ordinary Australian Outback into a distinctive fantasy world, a post-apocalyptic Wasteland. This, too, was fairly low-budget, requiring little more than a desert, a bunch of eccentric, souped-up vehicles, and a team of daredevil stunt performers. Even greater success allowed the third film a big Thunderdome set, some modest special effects, and a second star. Most recently Miller gained a blockbuster-size budget for special-effects, an Oscar-winning co-star, and a multiplication of the weird vehicles. This is not to say that Miller’s created world is as complex as Middle-earth, but it has a visceral sense of reality and a distinctive look that set it apart from any other films, fantasy or not. But how often can you generate a Mad Mad-style franchise from almost nothing?

Alcock doesn’t mention it, but fairy tales have become a fallback option for Hollywood fantasy. Such films, adapting the originals into versions aimed at adults, have largely failed to catch on. (Given the recent failure of The Huntsman: Winter’s War, we might suspect that the success of Snow White and the Huntsman was due largely to the star power of Kristen Stewart, fresh off the Twilight series.) Fairy tales are sketchy stories with fantastical events and minimal characterization. They usually either take place more-or-less in our world or else spend little time describing the look of Faerie.The designers are left to their own imaginations to create settings, most of which tend to be pretty conventional.

Following in the footsteps of the LOTR and Harry Potter filmmakers, finding a novel or other literary property with the built-in popularity to carry a big-budget special-effects film seems the way to go. Despite the plethora of fantasy novels since LOTR appeared in the 1950s, choosing just the right one has proven a considerable challenge.

New Line’s adaptation of The Golden Compass, the first book in Philip Pullman’s brilliant His Dark Materials trilogy, was creditable but not exciting enough to create a successful film, let alone a franchise justifying the expense. Perhaps the novel was too little known in the US. The same could be true for The BFG, another British children’s classic, which is doing even worse at the box-office. (The studio could at least have had the sense to rename it The Big Friendly Giant, though that probably would not counteract what I suspect was the public’s mistaken impression that the film was aimed strictly at children, and very young ones at that.)

Alcock carries on his speculations.

So how does a different fantasy film emerge from the shade that Middle-earth put over all the competition? Frankly, it’d have to be another masterpiece to do it. The problem is the cohesion of vision or sincerity of intent from these other would-be franchises.

“Make a masterpiece” is excellent advice but rather difficult to follow. It doesn’t always work, either. Probably the two best mainstream American films I saw last year were Mad Max: Fury Road and Pixar’s Inside Out. Both were fantasies. Neither, as far as I know, drew any comparisons to LOTR from critics or fans, so they did escape its shadow. Both were highly praised by critics and won Oscars. They may or may not be considered masterpieces in the long run, but they certainly could count as such in the context of contemporary Hollywood. One made lots of money and may eventually spawn a sequel, given Pixar’s growing penchant for such things. The other, given its hefty budget, probably did not make a profit, or at any rate not one that Warner Bros. would consider large enough to justify taking the franchise to a fifth film–unless, perhaps, Miller went for a lower-budget project. So making a masterpiece may help distance a film from LOTR, but it does not guarantee a more practical sort of success.

On the issue of vision or sincerity mentioned above, Alcock touches on one subject that I think helps explain why it’s extremely hard to produce successful fantasies that have not the slightest whiff of Middle-earth about them. His point also explains why we seem to be stuck in a dismal summer where every week the same set of interchangeable films come out. He discusses Hollywood’s failure to follow up the LOTR with a fantasy franchise that would avoid the inevitable comparisons to LOTR.

Just think of The Golden Compass, New Line’s attempt to create a new fantasy franchise out of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials, much more lukewarmly received and whose box office led to New Line’s end as an independent company. Now there’s food for thought–would Warner Brothers [sic], who own New Line as all but a label today, have really greenlit Lord of the Rings in its ultimate form?

I think we know that the answer to that question is almost certainly no.

In fact, LOTR actually did fail to get greenlit in its final form, though at a different major studio. As I describe in The Frodo Franchise, in 1998 Harvey Weinstein was planning to produce LOTR as a two-feature film directed by Jackson and with a budget of $140 million. When the project was a year and a half into the scripting and design process, Weinstein was called into Michael Eisner’s office at Disney, parent company of Miramax. Eisner demanded that he cut the film to one feature, made for $75 million. Jackson balked and persuaded Weinstein to put the project into turnaround for two weeks. Famously Jackson pitched it to Bob Shaye, founder and co-president of New Line, a man who knew the value of a franchise with a built-in fan base and proposed to make LOTR as three features.

Today’s New Line, a mere production unit of Warner Bros., could not undertake such a project on its own accord, and today’s Warner Bros. surely would not. With studios opting for the most established formulas, a film comparable in originality to LOTR being made, especially with all three parts shot simultaneously, would be little short of a miracle.

The only circumstance in which such things can happen would be an adaptation of a book so successful that it virtually guarantees box-office success. Warner Bros. undertook the Harry Potter series under such circumstances, given the overwhelming popularity of the book. That the resulting series of films pleased established fans and new audiences probably owes much to the fact that Rowling took an active role in consulting on the scripting and other aspects.

Today’s largely unappealing lineup of summer films (and I am writing here of mainstream Hollywood films, not including such original independent fare as James Schamus’ excellent Indignation) has been punctuated so far by two entertaining and satisfying items: The BFG and Pixar’s Finding Dorie. Both fantasies, one an undeserved box-office failure, the other a record-breaker. Which goes to show, I suppose, that good, non-LOTR-influenced fantasy (whatever its box-office record) rests with auteurs and Disney/Pixar.

Is television the answer?

Like numerous other writers, Alcock offers Game of Thrones as a model for what fantasy films with richly realized worlds might be.

If Middle-earth has a “successor,” it’s Game of Thrones. Based on George R. R. Martin’s books, the TV series has come far closer to Lord of the Rings‘ immersive world-building and cultural impact than any other fantasy, and perhaps suggests how Lord of the Rings might be adapted today.

He is far from the only writer to offer Martin’s books and the TV series based on them as an example of successful world-building. Many would say, to be sure, that the shadow of Tolkien’s and Jackson’s influence hovers over it, but perhaps that does not matter. It has brought respected long-form fantasy to TV, just as LOTR brought it to the big screen. It has gradually achieved critical acceptance, garnered a healthy number of awards, and contributed familiar tropes to modern culture, even for those unfamiliar with the books or series. I myself gave up on the novel after reading the first volume and have seen no episodes of the series. Already by the end of the first book it seemed to me that Martin was starting repeat his own devices, and if he was doing that within one book, what would later volumes be like? I certainly can’t see it as literature on a level even remotely approaching that of LOTR or even Harry Potter. I have not seen any episodes of the HBO series and hence cannot judge it. From what I can tell, it does not escape the shadow of Jackson’s LOTR, but that’s probably a matter of opinion.

Many fans who long to see an adaptation of Tolkien’s The Silmarillion have suggested that long-form television would be a more plausible medium than theatrical film. I consider The Silmarillion utterly unfilmable, except possibly in the hands of a brilliant animator, but that’s another issue. The point is that television, and especially powerful cable channels like HBO, are seen as the venue for long films that would be unlikely to be greenlit as high-budget theatrical features.

Despite appearances, I am not a keen fan of fantasy literature and films. The only fantasy novels (apart from children’s books) I have enjoyed enough to reread are LOTR, the Harry Potter series, and Susannah Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell. The seven-part TV series based on the latter ended its American run on BBC 2 just over a year ago. I believe it is somewhat parallel to the LOTR film in being a reasonably successful–artistically at least–adaptation of a major work of literature It also bears no trace of Tolkien’s influence.

How does it escape? If you asked someone who had read both Martin’s books and Clarke’s whether they had read Tolkien, he or she would probably guess that Martin had and would have no idea whether or not Clarke had.

Martin admits his debt to Tolkien freely. “I revere Lord of the Rings, I reread it every few years, it had an enormous effect on me as a kid. In some sense, when I started this saga I was replying to Tolkien, but even more to his modern imitators.”

Clarke also was a Tolkien fan, but I have never seen anyone compare JS&MN to LOTR, either the original novel or the TV series. For one thing, she had other, quite different influences well, as described in a reader’s guide on her publisher’s website.

During an illness that required her to rest a great deal, Clarke re-read Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, and when she finished she decided to try writing a novel of magic and fantasy. She had long admired the fantasy writing of Ursula Le Guin and Alan Garner, but also loved the historical fiction of Rosemary Sutcliff and novels of Jane Austen. These various influences were to come together in a novel which is part magical fantasy, part scrupulously researched historical novel, with teasing faux-academic footnotes referencing a bibliography of magical books entirely of her own invention.

Clarke also has a literary skill that elevates her above most writers in the genre. Her approach was not to invent an imaginary world à la Middle-earth, but to begin by setting her story in the actual English history of the Regency era. Into that she inserted two magicians seeking to revive the tradition of Faerie-derived English magic and use it to aid their country during the wars with Napoleonic France. Her seamless blend of real historical figures and events with her own inventions can leave many nonspecialist readers wondering which is which.

I have already written about the TV adaptation of Clarke’s book, pointing out both what I consider some problems with the adaptation of the narrative and some real strengths of the series. As with LOTR, the adaptation’s strengths have much to do with the design, the special effects, and the acting. Indeed,the series won two BAFTA TV Craft awards, for production design (above, designer David Roger accepts his award) and special effects. In some ways, it could have been to TV what LOTR was to film, though it was far less successful with audiences and thus will no doubt have concomitantly less influence.

The elusive “masterpieces” of fantasy that Adcock suspects might escape from the shadow of Jackson’s LOTR could be either films or TV series. But unless the studios greenlight more imaginative fare, that shadow will persist for a long time.

On the point about whether Warner Bros. would greenlight a LOTR trio of films today. I discuss studio executives’ decisions about which fantasy films to make, specifically in relation to Warner Bros. and Jack the Giant Slayer, in “Jack and the Bean-counters.” In my 1999 book, Storytelling in the New Hollywood, I suggested that Hollywood’s originality and risk-taking had declined so much, even by then, that many classic and successful films could not be greenlit; I suggested Witness, Chinatown, The Fugitive, and Alien as fairly recent examples. By now the system has become even more exclusionary.

The idea that series TV offers the advantage of more time to play out the narrative of a long book is not true in all cases. Including credits, JS&MN runs a total of 406 minutes, while LOTR runs 558 minutes in its theatrical edition and an extra two hours in the extended home-video release. (In the 50th Anniversary edition, Tolkien’s novel runs 1029 pages without the appendices. The first edition of JS&MN is 782 pages.) Ironically, in the wake of LOT’s success, New Line optioned JS&MN as a possible successor to Jackson’s film. The Golden Compass took precedence, and eventually JS&MN became available for the BBC to adapt. Made as a trilogy, with a higher budget, it would have looked great on the big screen.

Wildstyle, Gandalf, and Batman in The Lego Movie (2014)

A Hobbit is chubby, but is he pleasingly plump?

Kristin here:

Some readers have been kind enough to ask if I would be writing a wrap-up entry on The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies now that the entire set of Peter Jackson’s films have appeared, including the extended edition of the last part. I was somewhat hesitant to do so. Five Armies is my least favorite among the six parts, and I have many fond associations with researching and writing about the Lord of the Rings films for The Frodo Franchise book and blog. Still, it makes sense to follow up on my previous comments on the strengths and weaknesses of the two earlier parts of the HOB trilogy and suggest how they continued on into this concluding chapter.

I have previously blogged three times about The Hobbit at intervals since just before the release of the first part. In September of 2012, I posted “A Hobbit is chubby, but is he padded?” In it I discussed the July 30 announcement that the film would be released in three parts rather than the originally announced two. I expressed cautious optimism, suggesting that there was enough material in the original novel plus the appendices of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings to create a film reasonably faithful to the original.

In mid-January of 2013, I posted a follow-up entry, “A Hobbit chubby, but is he off-balance?” The first part of the film, An Unexpected Journey, had been out for about a month, and I felt the additions mostly worked well, or at least were acceptable. I still think the first part is the best.

Almost exactly a year later, I added a third entry, based on the release of The Desolation of Smaug: “Is Tauriel more powerful than Eowyn? and other questions we shouldn’t have to ask.” By this point I felt that the project had considerably strayed in directions that betrayed Tolkien’s source material. As the title implies, I felt that the modest “prequel” film had also begun to swell inordinately and threatened to overshadow the fine trilogy that the filmmakers had made earlier.

These problems are even more evident in the final installment.

Marvelous moments

To be sure, there are some impressive shots and scenes in the final film. In the opening sequence of Five Armies, Smaug’s flights over the town and his confrontation with Bard are the most impressive parts of the scene, and the dragon’s death is appropriately enough its high point, both literally and figuratively. The overhead shot of his lifeless body drifting downward, seen against the inferno that he has created, is one of the best of the film (see top). It recalls the marvelous shot of him at the end of Desolation, emerging from Erebor covered in the coating of molten gold that the Dwarves had hoped would kill him and rising into the sky as he effortlessly shakes it off.

Some of the later shots in Erebor are wonderful as well. (See the image at the bottom.)

The climactic confrontation between Thorin and Azog on the frozen lake has been widely praised. It’s a complete invention of the filmmakers; there is nothing like it in the novel. It contains many lovely shots which, I must say, provide a welcome change from the crowded battle scenes. The lake is introduced as Kili and Fili creep along its edge, hoping to reach the summit of Ravenhill, where Azog had been located as he commands the battle. (See top of this section.)

The confrontation itself contains many impressive compositions, both as the two competitors circle each other and later as Thorin, mortally wounded, watches the Eagles swooping as Azog’s corpse lies in the foreground.

Surely one of the film’s best scenes is the one where Thorin, driven nearly mad by his obsession with the treasure, wanders on the solid-gold floor left behind by the failed attempt to kill Smaug by flooding him with molten gold. We see him wander over the floor as a hallucinatory vision of Smaug slithers through the gold below him (left). Finally Thorin imagines himself sinking into the gold 9Right), an overhead shot that echoes the one of Smaug’s death at the top of this entry.

Another very different high point is Bilbo’s arrival back at Bag End only to find himself presumed dead and an auction of his effects going on. No doubt fans were looking forward to seeing this scene from the book, and it delivers considerable humor as well as poignancy once Bilbo gets inside his nearly empty house and replaces the portraits of his parents on their hooks.

Gaps and missed opportunities

Some things that one would expect to see in the film are simply not there. In the opening framing scene in Unexpected Journey, the elderly Bilbo remarks that the little trunk in which he has stored the treasured objects from his adventure still “smells of troll.” In Unexpected Journey we see the Dwarves bury treasure in trunks, so that it may be collected later. In Five Armies, we see Bilbo carrying his trunk on his journey as he nears home. Yet we never see him and Gandalf return to the scene of the encounter with the trolls and dig up the treasure. In the book, they do so and agree to divide the loot. Why bother to place such emphasis on the trunk and show Bilbo taking it home with him if the story does not include him retrieving it on the way back to Bag End? We last saw the trolls’ trunks two films ago, and surely at least a mention of their retrieval would remind those unfamiliar with the book where Bilbo got this rather large piece of luggage. Surely at least in the extended version a minute or so could have been spared from the overextended battle scene.

As to gaps, the big battle at Dol Guldur ends with Saruman telling Elrond to take the weakened Galadriel back to Lothlorien and “Leave Sauron to me!”

This is one the largest dangling causes in the film, and yet it never comes to anything. In between the Hobbit and LOTR films, Saruman seems to have come under Sauron’s sway, but there is no indication as to how that might have happened. Causes that dangle need to be taken up and explained.

More generally, fans have complained that Bilbo often seems to be missing from his own story.

The original novel is told almost entirely from Bilbo’s point of view. There are only a few scenes where he is not present, and his personality gives the book considerable unity of narrative tone. In Martin Freeman, the filmmakers found the perfect actor to portray him. It is a pity that Bilbo has to cede so much of his screen time to Azog and Bolg and Alfrid and even Tauriel, pleasant though she is in some ways.

The expanded edition

As with all five other parts of this serial, Five Armies was released in an extended version. This added 20 minutes, as compared with 13 minutes for An Unexpected Journey and 25 for The Desolation of Smaug. (For a list of which scenes were extended or added to all three parts, see here.) In the two previous parts, the additions were mainly more conversations and characterization. In Desolation, for example, the brief scene of Gandalf, Bilbo, and the Dwarves visiting Beorn were significantly expanded. In Five Armies, however, much of the extra footage expanded the already lengthy battle scene. There are some pluses and minuses in this new material.

Fans of the book were particularly annoyed by the elimination of the funeral of Thorin, Kili, and Fili, and a short but touching scene of the Dwarves and Bilbo grieving over their bodies was restored. This scene establishes that the Arkenstone, the cause of so much strife, has been returned to Thorin and will rest on his body, thus wrapping up the question of what ultimately happened to it.

A few additions provided explanations for plot points, as when Gandalf visits Radagast’s home after being rescued from Dol Guldur and receives Radagast’s staff to replace his own–thus confirming fans’ speculations about where he got the new one. (See above.)

Whence came the giant rams on which Thorin, Kili, Fili, and Dwalin ride up Ravenhill? Now we learn that they were the mounts of part of Dain’s Dwarf army.

By the way, I’m puzzled by the Hobbit film’s the obsession with using odd animals for transportation: Thranduil’s elk, Dain’s hog, other Dwarves’ rams, and Radagast’s bunny sled. The only one that comes from the book is the habit of orcs riding wolves and wargs, though we do know from LOTR that Dwarves don’t like riding horses–but Elves certainly do.

The one quiet conversation that was added has Bilbo talking with Bofur (in a track entitled “The Night Watch”). Bofur strongly hints that Bilbo would be justified if he simply slipped out and returned home before the battle starts, but Bilbo assures him he’s not leaving.

I suppose it’s a nice little reversal in the scene in Unexpected Journey when Bilbo does try to slip out of the cave in which the group are sleeping and go home. There Bofur spots him and kindly wishes him well. He is one of the few Dwarves that Bilbo seems especially to befriend, but it doesn’t really add much. In fact, about half of the Dwarves have been relegated to barely speaking. Some seem to have no audible lines, and some are barely glimpsed. It’s a considerable change from the earlier parts, where the writers took care to give each of them bits of business or dialogue.

One Dwarf’s role is considerably filled out from his relatively brief role in the theatrical edition. Dain Ironfoot, Thorin’s hog-riding cousin, now has considerable dialogue and swings a mighty war-hammer in battle. He is a much more comic character than in the book, which is unfortunate in that it makes him seem an inappropriate figure to replace the serious, majestic Thorin as King under the Mountain.

His salty language, though relatively mild as profanity (calling his foes bastards and buggers), is out of keeping with the language in the rest of the series. There is also some unintended humor as Dain and Thorin are able to pause in the midst of a crowded and chaotic battle to greet each other, exchange pleasantries, and discuss strategy, with the melee conveniently receding to provide them a little safety zone. Their discussion does help us a bit in understanding what is now an even more scattered, confusing battle scene.

Finally, we find out in this longer version how the comic villain Alfrid met his well-deserved end. Attempting to flee with some gold coins he has discovered, he hides on a catapult and inadvertently sends himself hurtling into the mouth of a large troll.

Alfrid, who does not exist in the novel, was a tolerable figure while the characters were still in Laketown and he could interact with the Master. Bringing him safely ashore and making him part of the actions of the citizens as they take refuge in the ruins of Dale, however, was in my opinion a big mistake. Without any justification, he becomes a sort of assistant to Bard. Fans widely expressed mystification as to why Bard and even Gandalf would give him important duties to perform when both should know that he is completely unreliable, foolish, dishonest, and selfish. In general he injects a humor that undercuts the serious nature of many of the scenes. He, like the Master, should have been left to go down with the ship back in Laketown.

Increased violence

Throughout the LOTR and Hobbit series, the filmmakers have pushed the limits of the rating system, always achieving a hard PG-13 label for both the theatrical and extended versions. With Five Armies, they have for the first time crossed the limit and been given an R rating, though only for the extended edition.

I see this as something of a betrayal of the fans, especially families, who have fallen in love with this franchise, sharing the films over many years. The reason for the R rating is probably entirely due to some extreme violence and cruelty. Certainly there is no sexual basis for such a rating, and the mild profanity mentioned above, introduced with the character of Thorin’s cousin Dain seems unlikely to have been a significant cause of the stricter rating.

One particularly disturbing figure is a troll who figures prominently in the battle. He has apparently had all four limbs systematically amputated and replaced with prostheses in the form of giant metal weapons. Moreover, he is controlled by a rider who guides him with reins made of large chains attached to his blinded eye sockets with hooks. While most of the trolls who serve the enemy’s troops seem to do so more-or-less willingly, this one does so through sheer torture. This is all the more disturbing because at one point Bofur manages to gain control of this troll and delightedly uses him as a weapon in the same fashion, directing him with the reins and hooks.

Apart from such scenes, there are numerous new moments where decapitations and amputations are copiously meted out, often in humorous fashion. In one scene Thranduil’s battle elk scoops up eight or so orcs, and the Elven King beheads them all with a single sweep of his sword.

The chariot drawn by large rams has blades sticking out from the hubs of its wheels, and these provide the opportunity for much carnage, as when one cuts off a large orc’s legs and it staggers about on the stumps of his thighs or when a row of trolls are rapidly decapitated as the the chariot bounces past them.

I watch and write about movies for a living and have been exposed to a great deal of cinematic violence, but such scenes as these seem particularly out of place to me in a series aimed at an audience intended to include young people.

More echoes of LOTR

In the third entry, I discussed what I consider a serious problem with The Hobbit: the tendency to copy so many elements from LOTR.

Most crucially, I think, instead of using these already established characters in Desolation or just sticking more closely to the book, the filmmakers have introduced many new elements that are essentially diminished versions of characters and events in LOTR. That strikes me as a bad idea and perhaps really does betray a lack of inspiration. Already fans of the LOTR films have complained that so many echoes of LOTR appear in Desolation. Worse is to come, though. When people view LOTR as part of a series of six parts beginning with The Hobbit, they will end up seeing things in LOTR as echoes of Desolation. The result will be to rob LOTR of some of its originality and effectiveness.

Take Tauriel. She’s a pleasant, admirable character, with a stubborn, headstrong streak that keeps her from being bland. Evangeline Lilly’s performance strikes me as excellent. A lot of fans worried about her inclusion in the film but came to like her. They seem to see her as blending well into the world of the film. But there’s a reason for that. She does come from the world of LOTR.

Was it really a good idea to add a major character who’s basically a blend of Arwen and Eowyn? Doesn’t she make both of those characters less distinctive?

Similar things happen in Five Armies. Bombur blows a big horn outside Erebor during the Battle, just had Gimli had done to signal the big charge out of Helm’s Deep in The Two Towers (in a more impressive composition).

Yes, one takes place in daytime and is seen in low angle, the other at dawn and from above, but still.

Or take the appearance of the Eagles, which in both films drift out of the bright clouds in the background, their leader carrying a wizard. (Radagast does not appear at all in the book, let alone as part of the battle.)

The berserker troll that butts his head into the protective wall at Dale recalls the similar Uruk Hai with a torch who dived into a drain tunnel at Helm’s Deep, sacrificing himself to set off an explosive and create a similar entryway for the attacking army of orcs.

In addition, there’s the scene of the arming of the men and boys in Dale echoing the one in Helm’s Deep. Or Dale in flames, see from above and looking very like Minas Tirith in a similar situation.

I wish I could give the filmmakers the benefit of the doubt and say that these echoes are attempts to create motifs that would knit the two films into a single, unified tale. That’s not the effect of them, however. Aren’t these just repetitions without any real connections? Why would things so often happen in the same way? Doesn’t it distract from the drama at hand to keep thinking back to when we’ve seen something like this before? Wouldn’t we’d rather be seeing something new and original?

There should instead be more echoes like the one mentioned above, between the death of Smaug above a lake of fire and the scene where Thorin’s hallucinations are staged on a similarly glowing golden floor. That’s the way to create a rich narrative, and that comparison resembles nothing in LOTR–except perhaps the shot of Gollum, also seen from above, falling into the pit of lava. Whether or not the similarity of the two shots in Five Armies were intended to echo the Gollum one, it’s a reasonable comparison to make.

I haven’t yet tried the experiment of watching all six parts straight through, The Hobbit and then LOTR, to see how they work as a complete serial. More than ever I fear that the result will be to diminish LOTR, which is clearly the better of the two by a long way.

Basically I do not think that many of The Hobbit‘s problems result from the splitting of the adaptation into three rather than two parts. Done in service to the original book, it could have worked. Rather, those problems stem from a fundamental mistake made by the filmmakers.

They decided to adapt The Hobbit into an adult story with the same sorts of somber moments and terrors that LOTR contains. I basically agreed with that decision in a previous entry, saying this was now Peter’s Hobbit. But given how far he took all this–with the overextended battles, the urge to interject grotesque humor into serious situations, and the extra characters who turn Bilbo into a supporting player in his own tale–I believe he should have done what Tolkien did: let the two books (or films) be different. Let one be aimed at children—less violent, simpler, more humor—and the other be aimed at adults.

So what if the two aren’t consistent with each other? Generations have read Tolkien’s two novels and noticed that they are essentially in different genres and simply accepted that. The problem has been compounded by the fact that so much that happens in The Hobbit is copied so closely from LOTR. Now that we have every bit of the second trilogy, I’m afraid I must conclude that yes, this Hobbit is chubby but also off-balance and padded.

My “A Hobbit is chubby” phrase refers to the fact that Tolkien’s Hobbits are all to some degree chubby. This is not the case with three of the four main Hobbits in LOTR, nor is it true of Bilbo. Still, given the controversy over the added length of the film adaptation, it was impossible to resist the reference.

Although much has been made of the idea that the two trilogies are the same length, in that they are three parts each, it’s worth pointing out that the extended version of The Hobbit (8 hours 52 minutes) totals an hour and a half shorter than that of The Lord of the Rings (11 hours 22 minutes). Over such a span it may not seem like much, but it’s the equivalent of a shortish feature film.

The waning thrills of CGI

Kristin here:

There have been rumblings lately about the surfeit of CGI-heavy films, especially superhero movies, and about a certain monotony in the results. Critics and fans are hailing Mad Max: Fury Road, in no little part because George Miller did stage much of the action, with real fantasy vehicles and hair-raising stunts, and employed CGI only when necessary. Among the diehard Peter Jackson fans over on TheOneRing.net, many argue that the emphasis on practical effects over digital in the Lord of the Rings trilogy should have been carried over to the Hobbit trilogy, despite the advances in CGI technology in the nine-year gap between them.

Earlier this month, Variety‘s Brian Lowry published an editorial laying out the problem. He concentrated on the superhero movies that have increasingly come to dominate the tentpole level of big-studio filmmaking:

The ability to mount enormous battles featuring multiple super-powered characters, however, has become its own trap. And while the results can be visually astounding, the movies regularly feel as lifeless and mechanized as the technology responsible for bringing those visions to fruition.

The why of it remains something of a mystery, but the outcome is frequently a hugely expensive–if often enough quite lucrative–tentpole release that certainly puts the money onscreen, yet nevertheless proves more numbing than exciting, even during what should be the show-stopping sequences.

The original “Avengers” was mostly a happy exception, even with its prolonged alien-invasion climax. “Age of Ultron,” while ambitious in exploring relationships among characters, becomes drearily repetitive as the heroes mow down another CGI horde, this time consisting of artificially intelligent robots.

[…]

The pattern has become predictable. “Iron Man,” a terrific movie overall — particularly in capturing the origin story — degenerated into a mundane brawl between two armor-clad characters. Ditto the “Hulk” reboot with Edward Norton, which culminated with the title character’s ho-hum showdown with another green behemoth, the Abomination.

One can argue, in fact, that the much-maligned second “Star Wars” trilogy sacrificed an element of its humanity in George Lucas’ embrace of a wholly digital filmmaking approach. At a certain point, watching droid armies being whacked to pieces begins to yield diminishing returns.

Put more simply, just because CGI wizardry allows you to do something, whether hoisting an entire city into the air or leveling skyscrapers willy-nilly, doesn’t always mean you should. Because while the box office figures might suggest otherwise, there is an audience out there that’s weary of these movies precisely because of the hollow quality to the inevitable final 30 minutes of unrelenting mayhem.

This struck a chord with me, because since the beginning of the year I have seen trailers for several CGI-heavy films. (How many of them begin with an ominous “helicopter shot” high over a CGI city, usually at night?) Most of them melt into each other in my memory, but I do recall that they included Insurgent (the teaser, below left) and Jupiter Ascending (trailer #3, below right).

My reactions to the Insurgent and Jupiter Ascending images were: 1) another burning cityscape with a CGI person flying through the air, and 2) wild horses couldn’t drag me to these.

Compare these two frames with the image at the top of this entry. My reactions to the Mad Max: Fury Road teaser, which I only saw in HD on my computer, were: 1) what a gorgeous shot, 2) why is that guy doing that–he’s crazy, 3) George Miller and all these other people are crazy, and 4) I must see this film ASAP. The same qualities attracted me to The Road Warrior, but this time Miller had a far bigger budget, allowing him to create more vehicles and make them more elaborate.

The increasingly same old-same old quality about superhero films extends to science-fiction films and dystopian future ones.

CGI is a marvelous technology and has been used to create wonderful films, scenes, and characters. Gollum remains one of its most successful and memorable creations. I suspect that many, like me, remember that initial jolt of amazement in the scene in The Two Towers when the mild “Smeagol” and villainous “Gollum” sides of his nature talked to each other, and a sudden switch to shot/reverse shot made his split visible, as if he had two bodies:

It was a brilliant way to handle the scene, but it also depended on us accepting Gollum as a character on the same plane of existence as Frodo and Sam. Yes, the technology for Gollum was improved for his reappearance in The Hobbit, but it wasn’t dramatically better, and the first trilogy was the real breakthrough.

Smaug was another creation where one could hardly deny that CGI was used with astonishing complexity and skill (see bottom). The same is true for The Dawn of the Planet of the Apes and The Rise of the Planet of the Apes (also with effects by Weta Digital, which also managed to fill in scenes involving the late Paul Walker in Furious 7 without barely anyone noticing).

Lest all this become too Weta-centric, I also have seen the teaser for Robert Zemickis’ The Walk a few times. Again there’s a computer-generated cityscape, as in Insurgent and Jupiter Ascending, but the effect is quite different. It’s an attempt to create realism in a story based on actual events; the actor obviously can’t be placed high above New York, and the Trade Towers are gone. The effect is anything but clichéd. That I was to see, too.

Another well-reviewed current science-fiction film, Ex Machina, uses CGI in an original way. David liked it less well than I did, but whatever one thinks of the film as a whole, the robot character Ava is not something we’ve seen on the screen before–at least, not done this way.

Historically, any art form goes through cycles. Hugely successful films will give rise to many imitators, and imitation eventually leads to cliché. The question is, will the filmmakers called upon to make big effects-heavy films make the effort to use CGI in an imaginative way? With sequel after sequel in the largest franchises already planned by the studios for years into the future, will the apparent assumption that flashy CGI is enough to attract the action-movie crowd prove wrong?

The madness of Mad Max

Despite the critics’ emphasis on the practical effects and real locations in Fury Road, it should be pointed out that Miller used quite a bit of CGI in the film. Indeed, he was no stranger to digital effects. For Babe (1995), his team used CGI to achieve the most realistic talking animals in films to that time. (Miller produced and wrote the script, with Chris Noonan directing; he directed Babe: Pig in the City.) Previously talking animals were usually done with puppets and animatronics, but Miller’s team used 3D scans of animals snouts and muzzles and manipulated the results. Babe won the 1996 Oscar for best visual effects. There were no exploding cities, giant armies, or battling superheroes, but experts recognized those moving animal mouths as cutting-edge stuff.

In Fury Road, CGI is used for effects that would be difficult, impossible, or prohibitively expensive otherwise. Furiosa’s missing left wrist and hand are an obvious example, as is the massive sandstorm that hits the fugitives and pursuers.

The blue night scene was shot day for night and then enhanced digitally, presumably with tinting and the addition of stars. The city which is the Citadel’s source of gasoline and is supposedly Furiosa’s goal as her truck sets out early in the film, is shown on the distant horizon but clearly was not built, since none of the action takes place there. The Citadel scenes were done in Australia, while most of the desert material was shot in Namibia. Some parts of the Citadel were built full-scale (e.g., the winch room), while green-screen replaced by digital set extensions supplied the rest. I think I spotted some digital matte paintings in some of the landscapes. But on the whole, Miller stuck to real locations, and most of the scenes of the chases were done with real vehicles and actors, chasing each other around the Namibian desert.

Miller commented, “We don’t defy the laws of physics–there are no flying human beings, no spacecraft–so it doesn’t make sense to do it as CGI. We’ve got real vehicles and real humans in a real desert, and you hope that all that texture will be up there on the screen.” Miller had in fact assumed that he would have to create the “pole cat” sequence, which has men perched on long, swaying poles atop speeding vehicles (above). Action unit director Guy Norris, however, shot a test scene on video, with no CGI. Miller was thrilled: “There were 10 pole cats swaying, coming down the road at speed, all of them on cars, and Guy was on one of the poles filming them. I choked up. I thought, ‘Wow, it’s real. It’s absolutely real.”

According to Simon Gray’s “Max Intensity” in the latest American Cinematographer (not yet online), “Months of rehearsals enabled the stunt crew to perform their choreographed sequences while the vehicles traveled at speeds up to 50 miles an hour.” (AC, June 2015, p. 42)

The reality of it comes through, as in this scene of one of many explosions. The stunt man flinching in the foreground is not the sort of thing you’d see if this were all being faked.

And some of the stunts are not all that different from what we saw in The Road Warrior or Beyond Thunderdome, both made in the pre-CGI days. This scene, for example, among the best in the film, where a motorcycle gang chases Furiosa’s rig.

One reason why Fury Road looks so good is results from Miller’s and and his cinematographer’s decision to avoid the look of most post-apocalyptic movies. Anne Thompson describes their approach: “The cliches of the genre were to desaturate the cinematography. So he and great Australian cinematographer John Seale (dragged out of retirement), saturated the color. ‘We were able to change the skies, and go against the idea that because it’s the apocalypse, there’s no longer any beauty in the world.'” (AC, June 2015, p. 48)

There are desert areas of Africa where the sand is the rich, peachy color that appears in the film. The Namibian desert, however, is not so colorful.

(George Miller, in the official Warner Bros. making-of publicity short)

The film’s senior colorist, Eric Whipp, describes the challenge of differentiating the largely brown, beige, and grey colors of the costumes and vehicles from such backgrounds: “The desert sand in Namibia is, in reality, closer to be gray color, but pushing it toward rich gold colors complemented the characters and vehicles, providing a strong, graphic look. The only other dominant color in the film was blue sky, which we embraced.”

The transformation of the desert into rich yellow and orange tones was done with what was obviously aggressive digital color grading. It runs marvelously counter to the dull blues, browns, and grays that form the dominant look of so many action films.

[May 31: On fxguide, Ian Failes has posted an excellent piece that lays out the practical vs. the digital effects in Fury Road.]

LOTR vs. The Hobbit

Reading Lowry’s comments made me think of Andrew Lesnie, who died recently at the young age of 59. Lesnie had unintentionally played a small but pivotal role in my attempts back in 2002-2003 to get permission to interview the Lord of the Rings filmmakers for my book, The Frodo Franchise. I needed to contact someone high in the production who could be a sort of sponsor for me, helping to gain New Line’s cooperation. The only people I figured could do that would be producer Barrie Osborne or Peter Jackson or Fran Walsh.

In November 2002, I was at a conference in Adelaide, Australia and met Annabelle Sheehan, who at that time was an administrator at the Australian School of Film, Radio and Television. When I told her of my potential project, she offered to put me in touch with Lesnie. I hesitated before responding. I knew that it would be wonderful to interview him, but my subject didn’t relate to cinematography at all. Moreover, he wasn’t in a position to sponsor such a project. Then Annabelle offered to introduce me to Barrie Osborne, which subsequently happened via email. The project became real at that point.

I’ve always regretted that I had no excuse to interview Lesnie. From interviews and his appearances in the supplements for the extended DVD editions of LOTR, he seems a genial man. I also admire the cinematography for LOTR. There’s a great variety in the lighting schemes, and he contributed some very striking moments to the film.

It’s of course very difficult to pin down exactly what Lesnie’s contributions to LOTR were in many scenes, given the considerable dependence on CGI. Still, I think he probably had more affect on the final look of LOTR than he did on The Hobbit. As the three parts of The Hobbit came out, it became increasingly clear that there were no shots or sequences that could stand comparison with the best things in LOTR. I think of well-conceived, dramatic shots like the one in The Fellowship of the Ring where a scene begins with a bucolic view out over a misty morning in the Shire, which is suddenly interrupted by ominous music and the entry from offscreen of one of the Black Riders’ horses.

Another shot I admire is the first exterior after the long sequence of the passage through the Mines of Moria in Fellowship. Gandalf has just fallen into the abyss with the Balrog, and the others flee. The cut to an extreme long shot of the rocky terrain (filmed on Mt. Owen) outside the eastern gate to the Mines is jolting, seemingly switching from a color film to a black-and-white one. A trace of green plants at the lower left is virtually unnoticeable, and only as the camera arcs around to follow the remaining Fellowship’s movements away from the gate (which was added digitally) does a bit of blue sky appear at the upper right and eventually the green of the landscapes in the distance.

Although there are plenty of New Zealand locations in The Hobbit, I can’t think of any that are used as effectively as some of the ones in LOTR–most memorably the Edoras set, which was built full-size on Mount Sunday on the South Island. The swooping helicopter shots around the rocky promontory, with the snowy mountains revolving slowly around it, became iconic moments in the film.

Viewers might think that those background mountains were added digitally, and certainly some scenes, including the ones set at Orthanc, did have backgrounds built up of mountains from a variety of places. The extreme long shots of Rivendell are a patchwork of elements. Not so for Edoras, however. David and I were privileged to fly around Mount Sunday in a small plane–after the Edoras set had been removed–and we saw more or less what one sees in the film.

It was a different time of year, November (the Southern Hemisphere’s equivalent of May), but the mountains are clearly the same ones.

There was a helicopter camera team, so Lesnie might have had nothing to do with these circling shots, nor with the mountain photography for the magnificent Beacons Sequence in The Return of the King (to which the fires were added digitally).

Again, there is nothing to compare with this in The Hobbit, which, I would say, suffers from having so many sequences with CGI-created landscapes.

The only really memorable shot I can think of from The Hobbit is entirely digital, the emergence of Smaug from Erebor, covered in gold, at the end of The Desolation of Smaug. He bursts through the door and soars up away from the camera, shaking the gold off in sparkling droplets.

The shot of the dragon’s death is nearly as impressive, as Smaug falls slowly downward away from the camera.

The problems with The Hobbit arise, I think, because so much of it, especially in the third part, has been conceived as almost entirely digital. Compare these two pre-battle moments from The Return of the King and The Battle of the Five Armies.

As Théoden addresses his troops before their charge during the Battle of the Pelennor, we are clearly watching real riders on real horses, their spears held at various angles. To be sure, the MASSIVE program was used to multiply horses and riders, but primarily in the extreme long shots. Hundreds of real ones were used in the scene. In the background we again see impressive non-CGI snow-covered mountains. There are four characters here about whom we care: Théoden, Éowyn, Merry, and Éomer. The Battle of the Five Armies shot of Thranduil’s troops, in contrast, involves perfect ranks of anonymous Elves, moving in synchronization. There is no actual landscape behind them, just vague patches of blue, brown, and white.

MASSIVE was used here as well, but for far more figures. Wasn’t the program devised to allow digital “extras” to move independently of each other rather than replicating a very limited number of gestures? It’s ironic, since in the film’s endless battle, characters moving in synchronization seem to be the rule. See the moment when the dwarves assemble their shields into a wall against the orcs, with Elves leaping effortlessly over them.

Which brings up the matter of seemingly weightless characters and creatures. There has been much discussion of the fact that Legolas and Tauriel leap about, stand on other characters’ heads while fighting, and bound up collapsing stone staircases. Admittedly, Tolkien says in the blizzard scene of The Fellowship of the Ring that Legolas’ “feet made little imprint in the snow.” But even assuming that Elves are very light, some of the antics in The Hobbit look plain silly.

And it’s not just Elves that zip about in this fashion. Partway through the Battle of the Five Armies, large rams appear out of nowhere. (I gather that their presence will be explained in the extended edition.)

Thorin, Kili, Fili, and Dwalin ride the rams up the sheer pinnacle to reach Azog’s command post. The rams bounce weightlessly and effortlessly up the steep cliffs, looking more like ping-pong balls than heavy animals. Indeed, gravity seems to be defied quite a bit in the films–even putting aside from the fact that the characters are able to survive impossibly long falls without a scratch. I can’t think of cases in LOTR where such things happen.

Much has been made of the fact that The Hobbit contains many echoes of LOTR, in terms of characters, scenes, and even specific repeated lines. I’ve complained about that myself. Yet there are many fans who prefer The Hobbit to LOTR–many of them fangirls obsessing over Richard Armitage (Thorin), Aidan Turner (Kili), Dean O’Gorman (Fili), and/or Lee Pace (Thranduil). Such fans proudly point to the “fact” that the second trilogy had higher box-office totals than did LOTR. In unadjusted dollars, yes. In adjusted dollars, LOTR made considerably more, and that without the benefit of 3D surcharges. I suspect this disparity arose from the fact that LOTR was so extraordinarily original, and because it balanced CGI and practical effects so effectively. The Hobbit tipped far in the direction of CGI, and it shows.

Many studios and filmmakers will continue to rely on the standard look of action/sci-fi/fantasy CGI, at least until it becomes so obviously repetitive that audiences lose interest. But films like Fury Road and LOTR offer models of how CGI and practical effects can be balanced for a much livelier film.

[April 18, 2016: Ex Machina, to the surprise of many, won the Academy Award for best special effects. This was probably because it was so original in its use of effects. After all, most special effects doesn’t equal best special effects.]

Comic-Con: The end of an era, and other highlights

Kristin here:

Long-time readers of this blog may recall that in 2008 I went to Comic-Con for the first time. I can’t recall exactly what led me to take the plunge. It may have been that by that time it was evident that the con had grown into a major opportunity for Hollywood studios to publicize their upcoming blockbusters to their core audience and I wanted to witness the process in person. Until this year, I hadn’t returned to Comic-Con. I was motivated in part by the fact that this was the last big promotional event for a film in the Lord of the Rings/Hobbit franchise. I had briefly discussed Comic-Con in relation to LOTR in The Frodo Franchise, but I had not witnessed any of the appearances of cast and crew promoting the first trilogy. This was my final chance, the end of an era.

I blogged about my first visit four times. I wrote about the LOTR/Hobbit presence on the Frodo Franchise blog. On this blog I gave an overview of the Comic-Con experience, analyzed why Hollywood poured so many resources into an event nominally about comic books, and posted a conversation between Henry Jenkins and me. Henry, who had helped found the area of fan studies back in the 1990s with such widely cited publications as Textual Poachers, was also a Comic-Con newbie that year, and we shared our reactions. (This year Henry was on a panel, “Creativity Is Magic: Fandom, Transmedia, and Transformative Works,” one of a number of panels on fan culture. I missed it because I was in line for Hall H. More on that below.)

A friend of mine who has a press pass assured me that they were not as hard to obtain as I had feared, so, based on my collaboration on this blog and my position on the staff of TheOneRing.net, I applied. To my delight, I was granted one, so I set out to cover Comic-Con more officially.

Going to Comic-Con alone isn’t nearly as fun, and I was lucky enough this year to meet up there with my friends, Professors Jonathan Kuntz and Maria Elena le las Carreras and their irrepressible daughter Rebecca, who are always terrific company.

Preview night

On the Wednesday evening before Comic-Con begins, there is a preview. This means that people with various special passes can get into the big exhibition hall where most of the booths are set up. These range from dealers in rare comic books to the biggest entertainment companies, like Warner Bros. and Lego. Many of them offer unique items only for sale or give-away at Comic-Con.

Many attendees have realized this, and they buy tickets that include the preview evening. The floor was much more crowded than when I attended the preview night in 2008. There were lots of lines with people trying to get those unique collectibles.

Others were there to look at comics. Yes, there are still plenty of comics at Comic-Con. There are dealers offering rarities, as in the image above. There are comics publishers with their latest offerings.

A particular favorite of ours is Fantagraphics, which specializes in reprinting comics. They’ve launched a set of hard-cover volumes of Walt Kelly’s syndicated Pogo strips. They also, I discovered, are doing a series of Don Rosa comics, also in hardback. In fact, when I was strolling around the booth, I realized that Rosa himself was signing autographs until 8 pm. It was then 7:59, so I grabbed volume 1 and was the last person to get my copy signed. By the way, it includes “Cash Flow,” one of the Uncle Scrooge stories I mentioned in our first blog entry on Inception. Volume 1 hasn’t actually been published, but it’s available for pre-order on Amazon.

The big moment of my evening, entirely by chance.

My first press conference

Once you’re granted a press pass, your name is put on a list made available to the exhibitors and publicists planning events. Companies big and small send you announcements about signings, press  conferences, swag available at booths, parties in downtown venues, and so on. Many of these events promote video games, graphic novels, and television, but one sounded intriguing to my film interests: a press conference for Penguins of Madagascar, an entry in Dreamworks’ animated Madagascar franchise. The odd thing was that the event was scheduled in the morning at 11:15, fifteen minutes before the DreamWorks panel in Hall H. If we came to the conference, we couldn’t get into Hall H–unless the PR people reserved seats there for us. The big attraction was that some of the voice talent, including Benedict Cumberbatch and John Malkovich, as well as the two directors would be there.

conferences, swag available at booths, parties in downtown venues, and so on. Many of these events promote video games, graphic novels, and television, but one sounded intriguing to my film interests: a press conference for Penguins of Madagascar, an entry in Dreamworks’ animated Madagascar franchise. The odd thing was that the event was scheduled in the morning at 11:15, fifteen minutes before the DreamWorks panel in Hall H. If we came to the conference, we couldn’t get into Hall H–unless the PR people reserved seats there for us. The big attraction was that some of the voice talent, including Benedict Cumberbatch and John Malkovich, as well as the two directors would be there.

I showed up and got a front-row seat off to the side. The room filled up (right).

The event itself started somewhat late, and two gentlemen who were not Benedict Cumberbatch or John Malkovich appeared and answered some questions. (I would give their names, but the usual signs put on the table in front of guests were not in evidence.) We were approaching 11:25. John Malkovich and another gentleman appeared. Another couple of questions were asked, and someone announced that Benedict Cumberbatch’s plane had gotten in late the night before and besides we had to leave to make room for the next event scheduled in the room. We were not escorted to reserved seats in Hall H, where I hear that Benedict Cumberbatch did appear.

I can only trust that this is not how most press conferences turn out. Perhaps I will be invited to another one and find out.

Bill Plympton in person

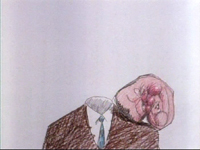

Given that I had no option to go to the Hall H DreamWorks Animation presentation, I sought out an alternative among the several items offered during the noon slot. I had had my eye on a panel which had as its guests the well-known animator Bill Plympton, as well as Jim Lujan, the co-director of the feature-length Revengeance, in progress. David and have long been fond of Plympton’s work, especially his laugh-out-loud classic, Your Face (1987), which was nominated for an Oscar. It’s just a series of distortions of a man’s face as he sings an utterly wimpy love ditty (above).

Plympton continues to be remarkably prolific. He has worked on fourteen episodes of The Simpsons, including doing twelve couch gags. Now he has a feature, Cheatin’, which will be shown for a week starting on August 15 at the downtown independent in Los Angeles. (Earlier this year it played at Slamdance, but I can find no theatrical release date.) You can see a short appeal animated by Plympton for the film’s Kickstarter appeal; its quite informative about the animation techniques used. The campaign itself is over, having raised $100,916, exceeding the goal of $75,000.

Plympton continues to be remarkably prolific. He has worked on fourteen episodes of The Simpsons, including doing twelve couch gags. Now he has a feature, Cheatin’, which will be shown for a week starting on August 15 at the downtown independent in Los Angeles. (Earlier this year it played at Slamdance, but I can find no theatrical release date.) You can see a short appeal animated by Plympton for the film’s Kickstarter appeal; its quite informative about the animation techniques used. The campaign itself is over, having raised $100,916, exceeding the goal of $75,000.

Apart from clips from Revengeance, Plympton also showed a brand new short, Footprints, a charming tale of a man’s search for a mysterious house invader. It will be shown on August 14 as part of the Hollyshorts Film Festival, which will honor Plympton with the Indie Animation Icon Award. The film was entirely hand-drawn in black and white and then colored digitally.

During the panel there was a contest for a T-shirt. The question was: What is Bill Plympton’s middle name? Despite a plethora of cell phones, laptops, and tablets in the audience, no one could come up with the right answer. A second question was put forth: what was Plympton’s first theatrically released film? “The Tune,” came a cry from the audience. It was Sam Viviano, art director of Mad Magazine; he walked off with the shirt. Plympton then sheepishly confessed that his middle name is Merton.

Plympton’s films have been hard to find online, but this fall they will become available on Source HD: “It’s the entire catalog, everything I’ve ever done.” That includes about 60 shorts. As a result of this online exposure, he says, “I expect that when I come back to San Diego next year they’re going to have to give me one of those huge 2000-seat rooms.” I hope so, and I hope it will be filled–but not so jammed that I could not get a seat.

Plympton offered all attending his panel a free autographed drawing. I went to collect mine at his booth in the exhibition hall and found him drawing (right), as he must constantly be doing. Note the Cheatin’ poster behind him at the left and the usual bustle of Comic-Con in the background. He paused to dash me off a delightful image of his famous Dog character. (An animator who doesn’t use cels has to be really fast at drawing.)

Plympton DVDs are not all that easy to find, though you can get them and other merchandise at his website’s shop. If you don’t know his work, it’s time to start catching up.

A new experience: The Indigo Ballroom

Seeking to accommodate more fans without violating fire regulations, Comic-Con has expanded into nearby buildings. One of the facilities utilized this year was the Hilton San Diego Bayfront, just across from the Convention Center on the Hall H end. That’s where the DreamWorks press conference sort of took place. Its biggest room was the Indigo Ballroom. I’m not sure it had 2000 seats, but I wouldn’t be surprised.