Archive for the 'Directors: Jia Zhang-ke' Category

Picking up the pieces; or, a Blog about previous blogs

A not-so-intimate bedroom scene from Cinerama Holiday (1955).

DB here:

Many of our blog entries are written in response to current events–a new movie, a film festival in progress, a development in film culture. Later we sometimes add a postscript (as here) bringing an entry up to date. Today, though, enough has happened in a lot of areas to push me to post the updates in a single stretch. It’s a sort of aggregate of chatty tailpieces to certain entries over the last year or so. Should the impulse seize you, you can return to an original entry, and there are other peekaboo links to keep you busy.

Out and about

Drug War.

Kristin wrote in praise of Neighbouring Sounds when she saw it at the Vancouver International Film Festival in 2012. Roger Ebert gave it a five-star rating, and A. O. Scott placed it on his annual Ten Best list. This network narrative is Brazil’s official entry for the Academy Awards. Sample Neighbouring Sounds here; the DVD is coming in May.

The annual Golden Horse Awards at Taipei have finished, and the Best Picture winner was the Singaporean Ilo Ilo, which neither Kristin nor I have seen. It would have to be exceptionally good to match the other films nominated, all of which we’ve discussed: Tsai Ming-liang’s Stray Dogs, Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster, Jia Zhang-ke’s A Touch of Sin, and (probably my favorite film of the year so far) Drug War, by Johnnie To Kei-fung. Stray Dogs did bring Tsai the Best Director award and his actor Lee Kang-sheng a trophy for best lead. Wong’s Grandmaster picked up six trophies, including top female lead and Best Cinematography. Jackie Chan won an award for Best Action Choreography. Although his CZ12 struck me as pretty dismal as a whole, its closing montage of Jackie stunts from across his career was more enjoyable than most feature-length films. In all, this has been a splendid year for Chinese-language cinema.

Back in the fall of 2012, I celebrated Flicker Alley‘s admirable release of This Is Cinerama, a very important film for those of us studying the history of film technology. Now Jeff Masino and his colleagues have taken the next step by releasing combo DVD-Blu-ray sets of two more big pictures, Cinerama Holiday (1955), the sequel to the first release, and South Seas Adventure (1958), the fifth and last of the cycle. Both are in the Smilebox format, which compensates for the distortions that appear when the curved Cinerama image is projected as a rectangle. Fortunately, Smilebox retains the outlandish optics to a great extent. The image surmounting today’s entry would give Expressionist set designers a run for their money, and it recalls the Ames Room Experiments. Cinerama wrinkles the world in fabulous ways.

Filled out with facsimiles of the original souvenir books and supplemented with a host of extras putting the films in historical context, these discs are fine contributions to our understanding of widescreen cinema. Because film archives don’t have the facilities to screen Cinerama titles (if they even hold copies), we have never been able to study, or even see, films that now look gloriously peculiar. Dare we hope that, from The Alley or others, we’ll get The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962), a strange, clunky, likeable movie?

Bookish sorts

Spyros Skouras and Henri Chrétien.

2013 saw the first of our online video lectures, one on early film history and the other on CinemaScope. The response to them has been encouraging, but as usual nothing stands still. If I were preparing the ‘Scope one now, I would draw from the newly published CinemaScope: Selected Documents from the Spyros P. Skouras Archive. Skouras was President of 20th Century-Fox, and he kept close tabs on the hardware he acquired from Chrétien in 1953. This collection of documents, edited by Ilias Chrissochoidis, shows that Skouras saw ‘Scope as a way to follow Cinerama’s path and boost the studio’s profits. “I would hate to think what would have happened to us if we had not created CINEMASCOPE. . . . Certainly we could not have continued much longer with the terrific losses we have taken on so many of our pictures.” ‘

Scope didn’t rescue the industry, or even Fox, from the postwar doldrums, but some of the behind-the-scenes tactics of the format’s first years are revealed here. For example, Skouras hoped that filmmakers would put important information on the surround channels deployed by the format, in the hope that theatre owners would make more use of them. “Such scenes would have to be unusual ones, but even with my limited imagination I can visualize many scenes in which dialogue would be heard from only the rear or the sides of the theatre.” This seems fairly extreme even today.

Jeff Smith is a swell colleague here at UW–Madison. (He and I are teaching a seminar that’s just winding down. More about that, I hope, in a later entry.) In his May guest entry for us, Jeff wrote about the new immersive sound system Atmos. But he’s been busy filling hard covers too. Research articles by him have appeared in three new books on film sound.

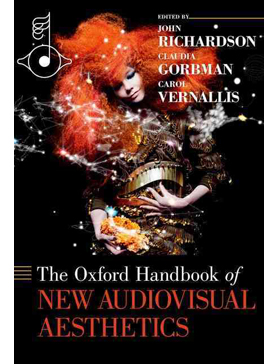

To Arved Ashby’s Popular Music and the New Auteur: Visionary Filmmakers after MTV Jeff contributed “O Brother, Where Chart Thou?: Pop Music and the Coen Brothers”–surely required reading in the light of Inside Llewyn Davis. He’s also a contributor to two monumental volumes that will set the course of future sound research. David Neumeyer has in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies gathered a remarkable group of foundational chapters reviewing the state of the art. Jeff’s piece charts the changing relations between the film industry and the music industry, from The Jazz Singer to Napster and file-sharing. For another doorstop volume, The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, edited by John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis (three more top experts), includes a powerful essay in which Jeff shows how techniques of intensified continuity editing have their counterparts in scoring, recording, and sound mixing. Not to mention his forthcoming book on an altogether different subject, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. All in all, a busy man–the kind we like.

To Arved Ashby’s Popular Music and the New Auteur: Visionary Filmmakers after MTV Jeff contributed “O Brother, Where Chart Thou?: Pop Music and the Coen Brothers”–surely required reading in the light of Inside Llewyn Davis. He’s also a contributor to two monumental volumes that will set the course of future sound research. David Neumeyer has in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies gathered a remarkable group of foundational chapters reviewing the state of the art. Jeff’s piece charts the changing relations between the film industry and the music industry, from The Jazz Singer to Napster and file-sharing. For another doorstop volume, The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, edited by John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis (three more top experts), includes a powerful essay in which Jeff shows how techniques of intensified continuity editing have their counterparts in scoring, recording, and sound mixing. Not to mention his forthcoming book on an altogether different subject, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. All in all, a busy man–the kind we like.

My March essay, “Murder Culture,” devoted some time to the women writers of the 1930s and 1940s who created the domestic suspense thriller–a genre I believe has been slighted in orthodox histories of crime and mystery fiction. The piece brought friendly correspondence from Sarah Weinman, editor of a new anthology from Penguin: Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives. She has assembled a fine collection, boasting pieces by Vera Caspary, Dorothy B. Hughes, Charlotte Armstrong, Dorothy Salisbury Davis, Margaret Millar, Patricia Highsmith, and Elisabeth Sanxay Holding (whom Raymond Chandler considered the best suspense writer in the business). These stories will whet your appetite for the excellent novels written by these still under-appreciated authors. Sarah’s wide-ranging introduction to the volume and her headnotes for each story will guide you all the way.

Finally, not quite a book but worth one: “The Watergate Theory of Screenwriting” by Larry Gross has been published in Filmmaker for Fall 2013. (It’s available online here to subscribers.) The essay is based on the keynote talk that Larry gave at the Screenwriting Research Network conference here in Madison.

Digital is so pushy

From Doddle.

Back in May, I provided an update on the progress of the digital conversion of motion-picture exhibition. Today, 90% of US and Canadian screens are digital, and over 80% worldwide are. (Thanks to David Hancock of IHS for these data.) I wish I could say the Great Big Digital Conversion was at last over and done with, but we know that we live in an age of ephemera, in which every technology is transitional. As I was finishing Pandora’s Digital Box in 2012, the chatter hovered around two costly tweaks.

The first involved higher frame rates. One rationale for going beyond the standard 24 fps was the prospect of greater brightness to compensate for the dimming resulting from 3D. Peter Jackson presented the first installment of his Hobbit film in 48 fps in some venues, and James Cameron claimed that Avatar 2 and its successor would utilize either 48 fps or 60 fps. And in January of this year some studio executives predicted that 48 fps would become standard.

Not soon, though. The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug will play in 48 fps on fewer than a thousand screens. Bryan Singer, who praised the process, has pulled back from handling the next X-Men movie at that frame rate. The problem is partly cost, with 48fps demanding more rendering and vast amounts of data storage. As far as I can tell, no one but Jackson and Cameron are planning big releases in the format.

The other innovation I mentioned in Pandora was laser projection. It too will brighten the screen, and according to its proponents it will also lower costs. Manufacturers are racing to build the machines. Christie has presented GI Joe: Retaliation in laser projection at AMC Theatres’ Burbank complex, and the firm expects to start installing the machines in early 2014. Seattle’s Cinerama Theatre is scheduled to be the first. NEC, the Japanese company, premiered its laser system at CineEurope in May. A basic NEC model designed for small screens (right) will cost about $38,000—an attractive price compared to the Xenon-lamp-driven digital projectors currently available. But the high-end NEC runs $170,000!

How to justify the costs? One Christie exec suggests branding: “Laser is a cool term that audiences immediately identify with.”

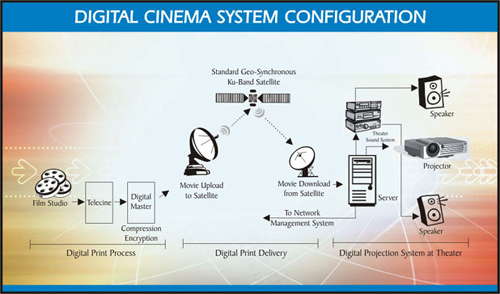

Perhaps the most important innovation since last spring’s entry involves an electronic delivery system. In October, the Digital Cinema Distribution Coalition, a consortium of the top three theatre chains along with Warners and Universal, launched a satellite and terrestrial network for delivering movie files to theatres. Theatres are equipped with satellite dishes, fiberoptic cable, and other hardware. The new practice will render the current system of shipping out hard drives obsolete, although the drives will probably continue for a time as backups. The DCDC has scheduled over thirty films to be sent out this way by the end of the year, and 17,000 screens in the Big Three’s chains are said to be hooked up. For more information, see David Hancock‘s IHS Analyst Commentary.

In the 1990s, satellite transmission was touted as the best way to send out digital films, and it was tried with Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones in 2001. Sometimes things move in spirals, not straight lines.

Speaking of the Conversion, an earlier entry pointed out the creative strategy used by the Lyric Theatre in Faulkton, South Dakota to finance its digital changeover. A gun raffle was announced on the Lyric’s Facebook page. Top prize was planned to be a set of three weapons: an AR-15 rifle, a shotgun, and a 1911 pistol.

The theatre’s screening season concluded, but the raffle is going forward, on New Year’s Eve, no less.

Television in public, movies in private

Dr. Who: Day of the Doctor (2013).

I can’t stand all this digital stuff. This is not what I signed up for. Even the fact that digital presentation is the way it is right now–I mean, it’s television in public, it’s just television in public. That’s how I feel about it. I came into this for film. —Quentin Tarantino

Spirals again. When attendance began to slump after 1947, Hollywood tried a lot of strategies–color, widescreen processes like Cinerama and ‘Scope, stereo sound, and not least “theatre television.” Prizefights, wrestling matches, and even operas were transmitted closed-circuit. Now theatre television is back, made possible by The Great Big Digital Convergence.

Godfrey Cheshire predicted some fourteen years ago that as theatres became “TV outside the home,” what we now call “alternative content” would become more common.

Pondering digital’s effects, most people base their expectations on the outgoing technology. They have a hard time grasping that, after film, the “moviegoing” experience will be completely reshaped by–and in the image of–television. To illustrate why, ponder this: if you were the executive in charge of exploiting Seinfeld’s last episode and you had the chance to beam it into thousands of theaters and charge, say, 25 dollars a seat, why in the hell would you not do that? Prior to digital theaters, you wouldn’t do it because the technology wouldn’t permit it. After digital, such transpositions will be inevitable because they’ll be enormously lucrative.

Godfrey’s prophecy has been fulfilled by all the plays, operas, and other attractions that run in multiplexes during the midweek or Sunday afternoon doldrums. His Seinfeld analogy was reactivated by last month’s screenings of Dr. Who: The Day of the Doctor in 3D. It was shown on 800 screens in seventy-five countries, from Angola to Zimbabwe, while also being broadcast on BBC TV (both flat and stereoscopic). The Beeb boasted that the per-screen average for the 23 November show beat that of The Hunger Games: Catching Fire. Globally, it took in $10 million, despite being available for free on TV and the Net. In the US, the event was coordinated by Fathom, a branch of National Cinemedia, a joint venture of the Big Three chains.

While some complained about dodgy 3D in the show, a surprisingly fannish piece in The Economist declared that “this landmark episode was buoyed up with fun, silliness, and hope.” The larger prospect is that other TV shows will take the hint and host season premieres or end-of-season cliffhangers in theatres. Many art house programmers would kill to show episodes of Game of Thrones or Mad Men, or even marathon runs of House of Cards. If it happens at all, I’d bet on Fathom getting there first.

I’ve had little to say, in this arena or in Pandora, about streaming and VOD, but these are becoming important corollaries of the Great Big Digital Convergence. Netflix in particular is expanding its reach, growing its subscriber base, creating original series, and enhancing its stock value, despite some ups and downs. At the same time, it’s pressing studios and exhibitors for the reduction in “windows,” the periods in which films are available on different platforms.

The theatrical window was traditionally the first, followed by second-run theatrical, airline and hotel viewings, pay cable, and so on down the line. Now that households have fast web connections, streaming disrupts that tidy business model. In October Ted Sarandos, Chief Content Officer for Netflix (right, with Ricky Gervais), suggested that even big pictures should go day-and-date on Netflix.

The theatrical window was traditionally the first, followed by second-run theatrical, airline and hotel viewings, pay cable, and so on down the line. Now that households have fast web connections, streaming disrupts that tidy business model. In October Ted Sarandos, Chief Content Officer for Netflix (right, with Ricky Gervais), suggested that even big pictures should go day-and-date on Netflix.

“Why not follow with the consumer’s desire to watch things when they want, instead of spending tens of millions of dollars to advertise to people who may not live near a theater, and then make them wait for four or five months before they can even see it?” he added. “They’re probably going to forget.”

Exhibitors howled. Sarandos quickly recanted, saying only that he wanted people to rethink the current intervals between theatrical and ancillary release.

Some observers speculated that his October remarks were staking out an extreme position he intended to moderate in negotiations down the line–possibly to suggest that mid-budgeted pictures would be good ones to experiment with on day-and-date. Perhaps too Netflix was emboldened by the much-publicized remarks of Spielberg and Lucas in a panel last June, when they indicated that the future for most movies was VOD, with multiplexes furnishing more costly entertainments for the few. (In the same session, Lucas predicted that brain implants would allow people to enjoy private movies, like dreams.)

In any event, windows are already shrinking. In 2000, the average theatrical run was 170 days; now it’s about 120 days. With about 40,000 screens in the US, films play off faster than ever before. Video piracy, which makes new pictures available well before legal DVD and VOD release, puts pressure on studios to shorten windows. It seems likely that the windows and the intervals between them will shrink, perhaps allowing films to go to all video formats as quickly as 30-45 days after the theatrical release ends.

Studios have incentives to shorten the windows, if only because a single promotional campaign can be kept going long enough for both theatrical and home release. In addition, buying or renting a movie with a couple of clicks encourages impulse purchasing, and the cost feels invisible until the credit-card bill comes. Nonetheless, commitment to day-and-date home delivery would be risky for the studios.

Hollywood is more than ever before playing to the global audience. Even with the VOD boom, digital purchase and rental constitute a small portion of the world’s movie transactions. According to IHS Media and Technology Digest, theatrical ticket sales, purchase and rental of physical media (DVD, Blu-ray) add up to nearly 12 billion transactions, while Pay Per View, streaming, and downloads come to only about a billion or so. (These categories omit subscription services like cable television and basic VOD on Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, and the like.) Moreover, customers in 2012 spent about 61 billion dollars buying tickets to movies, buying DVDs, and renting DVDs. Tania Loeffler of the IHS Digest writes of North America, the most developed market for digital sales and rental:

Movie purchases made online in North America increased year-on-year by 36.6 per cent to reach 29.2m transactions. The rental of movies online also increased, to 112m transactions, an increase of 57.3 per cent over 2011. Despite this strong growth, movies purchased or rented via over-the-top (OTT) online movie services still only accounted for a combined $836m, or 3.3 per cent of total consumer spending on movies in North America.

By contrast, worldwide consumer spending on theatrical movies actually grew in 2012, to a whopping $33.4 billion–over 50 % of all movie transactions. (Thank you, Russia and China.) And despite the decline of disc purchases and rentals, Loeffler estimates that physical media will still comprise about thirty per cent of worldwide movie transactions through to 2016.

Theatrical releases continue to offer studios the best deal. Because the prices of streaming and downloaded films are low, there is less to be gained from them. True, if windows shrink, the studios will demand that Netflix and its confrères price VOD at high levels, say $25-50 for an opening-weekend rental. But consumers used to cheap movies on demand could balk at premium pricing.

At present, digital delivery of movies to the home provides solid ancillary income to the distributors, even if it doesn’t yet offset the decline in physical media. Add in Imax and 3D upcharges, and things are proceeding well for the moment. Like the rest of us, moguls pay their mortgages in dollars, not percentages or transactions. As long as some hits keep coming, we should expect that studios will maintain an exclusive multiplex run for major releases, as the most currently reliable return on investment.

Orpheum metamorphosis

The New Orpheum Theatre, 216 State Street, 1927.

Another note on exhibition relates to the last commercial picture palace in downtown Madison, Wisconsin. My July 2012 entry related the conspiratorial tale of how the grand old Orpheum Theatre on State Street fell on hard times. In fall of 2012 the building seemed slated for foreclosure, but then maybe not. Last month Gus Paras, a hero of my initial post, stepped forward and bought the old place. According to Joe Tarr in our politics and culture weekly Isthmus, there’s a lot of work to do.

Plaster is crumbling off sections of the ceiling, the result of years of water damage from a leaky roof. The walls are littered with scratches and marks, in bad need of a paint job. A plastic garbage can sits in the theater, collecting water leaking from an upstairs urinal. Paras even found dried-up vomit in two spots on the carpet.

Making matters worse, Monona State Bank, which controlled the property while it was in foreclosure, filled in the “vaults” behind the theater, which means replacing the building’s frail boilers and air conditioning will be much more complicated and expensive.

“I don’t have any idea how I’ll get the boiler in and out,” Paras says. “The stairs are not strong enough.”

Envoi

Have any of you worked on a film, say, 10 years ago, and it comes out on Blu-ray and you look at it and think, “This isn’t the film I’ve shot”?

Bruno Delbonnel (DP, Inside Llewyn Davis): Always. Always.

Barry Ackroyd (DP, Captain Phillips): I’ll be watching and it’s in the wrong format.

So what is it like to devote your lives and careers to creating images that you know exist only momentarily in their absolute best state, that may never be seen by most people the way you would like them to be seen?

Sean Bobbitt (DP, Twelve Years a Slave): At least you get a chance to see it once. All you can do is hope that people will see an approximation of that. I’ve been to screenings where I’ve had to get up and walk out because I just couldn’t bear to watch the film in the state it was in. But at the end of the screening, people say, “That was fantastic. That was beautiful. Well done!” and you’re thinking, “If only they had seen the real thing.” We would drive ourselves mad if we worried too much about it.

On shrinking windows, see Andrew Wallenstein and Ramin Setoodeh, “Exhibitors Explode over Netflix Bomb,” Variety (5 November 2013), 16. The chart on this page doesn’t appear in Variety‘s online edition of the story. Tania Loeffer’s report, “Transactional Movies: The Big Picture,” appeared in IHS Screen Digest (now IHS Media and Technology Digest) for April 2013, 123-126. Douglas Gomery discusses the theatre television plans of the 1940s-early 1950s in his Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States, pp. 231-234. My envoi comes from a revealing conversation among cinematographers at The Hollywood Reporter.

A 2012 catchup blog chronicling earlier phases of these developments is here.

P.S. 23 December 2013: David Strohmaier, the creative force behind the Cinerama restorations, has put online the stirring original trailers for Search for Paradise (low resolution and high-definition) . David attended the U of Iowa when Kristin and I did, though alas we didn’t meet him. He deserves a big thank-you for all his work in making these extraordinary films available to us.

The Grandmaster.

VIFF 2013 finale: The Bold and the Beautiful, sometimes together

Gebo and the Shadow (2012).

DB here:

I’m a little late catching up with our viewings at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year (it ended on the 11th), but I did want to signal some of the best things we didn’t squeeze into earlier entries. Kristin and I also want to pay tribute to one of the biggest moving forces behind the event.

Safe but not sorry

Like Father, Like Son (2013).

Among other goals, film festivals aim to provide a safe space for nonconformist filmmaking. Programmers need to find the next new thing—art cinema is as driven by novelty as Hollywood is—and they encourage films that push boundaries. What isn’t so often recognized is that sometimes festivals show filmmakers who were once quite artistically daring backing off a bit from their more radical impulses. Part of this is probably age and maturity; part of it reflects the fact that apart from daring novelties, festivals also showcase works that might cross over to wider audiences. And of course festivals will present recent works by the most distinguished filmmakers, almost regardless of the programmers’ hunches about their quality. Some sectors of the audience want to see the latest Hou or Kiarostami or Assayas.

Koreeda Hirokazu was thirty-three when Mabarosi (1995) won a prize at Venice. It’s an austerely beautiful work, presenting a disquieting family drama in very long, static takes. Once the action shifts to a seacoast village, distant shots render slowly-changing illumination playing over landscapes, while the tension between husband and wife is built out of small gestures. For example, we learn that the forlorn wife is waiting in the bus stop only when a little bit of her comes to light.

Lest this seem just fancy playing around, Koreeda occasionally used his long takes to build suspense. Yumiko’s new husband has been drinking. While he’s out of the room, she opens a drawer to retrieve the bike bell she keeps in memory of her first husband, killed in a traffic accident. The second husband returns unexpectedly, and drunkenly collapses on the table beside her. But when she lifts her hands out of her lap, she inadvertently lets the bell tinkle a little.

The sound rouses him and he asks what she’s holding. She raises her head at last and they begin a quarrel about each one’s motives in marrying the other.

Eventually he will shift woozily to the other side of the table and notice what has been sitting quietly in the frame all along: the still-open drawer on the far right.

In later films, from After Life (1998) to I Wish (2011), Koreeda’s visual design became less reliant on just-noticeable changes within a placid shot. The images have become less demanding, and more extroverted narrative lines carry stronger sentiment. The films remain admirable in their ingenious plotting and mixture of humor and pathos—which is to say, they are committed to that “cinema of quality” that makes movies exportable.

That commitment is firmly in place in Like Father, Like Son. Koreeda, now fifty-one, dares almost nothing stylistically or narratively. Yet every scene leaves a discernible tang of emotion, and his light touch assures that things never lapse into histrionics. If Nobody Knows (2004) and I Wish (2011) are his “children films,” this is, like Still Walking (2008), a movie about being a parent.

The plot has a fairy-tale premise: Babies switched at birth. Our viewpoint is aligned with the well-to-do parents and particularly the ambitious executive Ryota. When he finds that six-year-old Keita isn’t his birth son, he insists on swapping the boy into the household of the happy-go-lucky working-class Saiki family. In exchange, Ryota and his wife take in the boy that Saikis have raised as their own.

As the film proceeds, our view widens to create a welter of comparisons—two ways of being six years old, tough discipline versus easygoing parenting, what rich people take for granted and what poor people can’t, a solicitous mother versus one who can’t spare time for coddling. Koreeda is faultless in measuring the reactions of all involved. Ryota’s wife slips into quiet depression. Saiki is an affable father with a childish streak, but he also looks forward to suing the hospital. Saiki’s wife, a no-nonsense woman with two other kids to care for, is a mixture of toughness and maternal affection. As in a Renoir film, everyone has his reasons, and the drama depends on a process of adjustment stretching across many months. Climaxes become muted, though no less powerful for that.

A smile and a tear: the Shochiku studio formula, enunciated by Kido Shiro back in the 1920s, remains in force here. Simple motifs, such as images stored on a camera’s photo card, hark back to all those affectionate picture-taking scenes in Ozu’s classics. The whole is shot with a conventional polish—coverage through long lenses, straightforward scene dissection—that’s far from the strict, slightly chilly look of Maborosi.

It’s impossible to dislike this warm, meticulously carpentered film. Koreeda has proven himself a master of humanistic filmmaking, and I admire what he’s done (as these entries indicate). Those of us who’ve been following his career for nearly twenty years, however, may feel a little disappointed that he hasn’t tried to stretch his horizons a bit more.

Like Father, Like Son was rewarded with the Jury Prize at this year’s Cannes festival. Steven Spielberg, jury president, has acquired remake rights for DreamWorks.

Action, blunt or besotted

A Touch of Sin (2013).

Jia Zhang-ke’s A Touch of Sin offers a comparable adjustment to broader tastes. It’s far less forbidding than his early features Platform (2000), Unknown Pleasures (2002), and The World (2004). Somewhat like Koreeda, Jia’s earliest fiction films embraced a long-take aesthetic that tended to keep the characters’ situations framed in a broad context. (His documentaries, like the remarkable 2001 In Public, were somewhat different.) Jia proceeded to breach the boundary between documentary and fiction in Still Life (2007), Useless (2007), and 24 City (2008). With A Touch of Sin, Jia takes on a twisting, violent network narrative that is as shocking as Koreeda’s duplex story is ingratiating.

We start with a villager who fumes at the corruption in his town and carries out a vendetta against its rulers. Another story centers on a receptionist who is taken for a prostitute and abused by massage-parlor customers. A third protagonist is an uneducated young man floating among factory jobs who turns his frustration inward. Threading through these is a drifter who shoots muggers from his motorcycle and later takes up purse-snatching.

The sense of inequity and exploitation that ripples through Still Life and 24 City now explodes into rage. Rich men (one played by Jia) puff cigars while strutting through a brothel, businessmen casually exploit their mistresses and buy off politicians, and injustices are settled with fists, knives, pistols and shotguns. “I was motivated by anger,” Jia says. “These are people who feel they have no other option but violence.”

Like Koreeda, Jia has had recourse to some of the casual long-lens coverage we find in many contemporary movies, but certain shots gather weight through his signature long takes–especially shots holding on brooding characters. In all, we get a dread-filled panorama, with bursts of violence staged and filmed with an impact that reminds you how sanitized contemporary action scenes are.

For more, see Manohla Dargis’ rich Times review of the film.

After the painstaking (and pain-giving) dynamics of Drug War (our entry is here), one of Johnnie To Kei-fung’s best recent films, it’s wholly typical that he does something outrageous. His work with Wai Ka-fai at their Milkyway company has always alternated unforgiving crime films of rarefied tenor with sweet and wacko romantic comedies that assure solid returns. But seldom have they combined the two tendencies into something as screechingly peculiar as The Blind Detective.

Initially the investigator, inexplicably named Johnston, seems to be a brother to Bun, the mad detective of To and Wai’s 2007 film. He insists on having the crime reenacted so as to intuit the perp’s identity. But since Johnston is blind, somebody else must tumble down stairs, get whacked on the head, and generally suffer severe pain in the name of the law. Ready to sacrifice herself to Johnston’s mission is officer Ho, a spry and game young woman with a crush on him.

Johnston and Ho are trying to find what happened to a schoolgirl who went missing ten years before. But this account makes the movie seem more linear than it is. Johnston makes his living from reward money, and he’s also dedicated to finding a dancing teacher he fell in love with when he had sight. So the search for Minnie is constantly deflected. Yet the digressions end up, mostly through Johnston’s inexplicable flashes of imagination, carrying them back to their main quest.

This episodic plot, or rather two plots, stretched to 130 minutes (making this the longest Milkyway release, I believe), yields something like a Hong Kong comedy of the 1980s, where slapstick, gore, and non-sequitur scenes are stitched together by the flimsiest of pretexts. The tone careens from farce (not often very funny to Westerners) to grim salaciousness. Johnston’s intuitive leaps are represented by blue-tinted fantasies that show him gliding through a scene at the moment of the murder, or assembling a gaggle of victims to declaim their stories. Characters are ever on the verge of exploding in anger or aggression, and between the big scenes Ho and Johnston dance tangos and gnaw their way through steaks, fish, and other delicacies.

Once more, the congenitally fabulous Andy Lau Tak-wah is accompanied by Sammi Cheng as his love interest, and the two ham it up as gleefully as in Love on a Diet (2001). (They were more subdued in my favorite of the cycle, Needing You…, 1999.) This is, in short, a real Hong Kong popular movie. It brought in US $2.0 million in the territory, and $33 million on the Mainland, about the same as Monsters University. If it keeps Milkyway in business, how can I object?

For a discerning take on The Blind Detective, see Kozo’s review at LoveHKFilm.

JLG in your lap

Kristin and I were keenly looking forward to 3 x 3D, the portmanteau film collecting stereoscopic shorts by Peter Greenaway, Edgar Pêra, and Jean-Luc Godard. Kristin found the Greenaway episode–sort of his version of Russian Ark, taking the camera through the labyrinth of a ducal palace and showing off elaborate digital effects–fairly appealing. But for us the Godard was the main attraction, and he didn’t disappoint.

At one level, The Three Disasters reverts to his characteristic collage of found footage, film stills, scrawled overwriting, and insistent voice-over. (Is it my imagination or does the the 83-year-old filmmaker’s croak sound increasingly like that of Alpha 60?) The montage is sometimes over-explicit, as when Charlie Chaplin is juxtaposed with Hitler. There’s a funny passage of portraits of one-eyed directors (Lang, Ford, Ray), as if to reassert the primacy of classical monocular cinema. At other points, things get obscure, as when Eisenstein’s plea for Jewish causes during World War II is followed by shots from The Lady from Shanghai. But this is the Godard of Histoire(s) du cinema, piling up impressions that beg for acolytes to identify the images and find associations among them.

Frankly, this side of Godard doesn’t grab me as much as his pseudo-, quasi-, more-or-less-narrative features. But in 3D his dispersive poetic musings take on a new vitality. He doesn’t retrofit old movie clips and still photos for 3D. Instead he superimposes them, making one cloudy plane drift over another. He can also, more forcefully, present his signature numerals and intertitles in a new way–by having them pound out of the screen and hang rigidly in front of the image.

There are also some 3D shots made specifically for the film, most consisting of handheld shots that shift around a park, a medical complex, and, of course, a media studio. The very title of Godard’s film, punning on 3D as a technical disaster, as well as a throw of the dice (dés), suggests his ambivalence toward the technology. “The digital,” his voice declares, “will be a dictatorship,” but perhaps it will never abolish chance.

As usual, Godard has fun with simple equipment. He frankly shows us his camera rig, two Canon DSLRs lashed together side by side, one upside down. By shooting them in a mirror and shifting focus, he manages to make each lens pop and recede disconcertingly, as if Escher had gone 3D. This shot alone should inspire DIY filmmakers everywhere. So too should the one-slate credits. Whereas Greenaway’s segment lists scores of names in its credit roll, Godard’s lists only four, alphabetically. I can’t wait for the feature, Farewell to Language. (Trailer here.)

Brian Clark has an informative review of The Three Disasters at twitchfilm.

Looking at the fourth wall

In nineteenth-century Portugal, the elderly Gebo ekes out a living as a company accountant. His wife Doroteia and his daughter-in-law Sofia wait with him for the return of João, a rebellious ne’er-do-well. Gebo feeds Doroteia’s illusions about their son, who has likely become an outlaw. When João returns after eight years away, he throws the family into turmoil and becomes fixated on the cash that his father safeguards for the firm.

After World War II, André Bazin noticed that many filmmakers were starting to take a creative approach to adapting plays. Olivier’s Henry IV, Welles’ Macbeth and Othello, Dreyer’s Day of Wrath, Cocteau’s Les Parents terribles, Melville’s Les Enfants terribles, Hitchcock’s Rope, and Wyler’s Little Foxes and Detective Story, are far from the “photographed theatre” that some critics feared would dominate talking pictures. For decades Manoel de Oliveira has explored avenues of theatrical adaptation that have led us to some daring destinations. Gebo and the Shadow, drawn from a 1923 play by the Portuguese Raúl Brandão, is a powerful recent example, and possibly the best film I saw at VIFF this year.

After the credits show João loitering on the docks, the film confines the action almost wholly to the parlor of Gebo’s family home. Early on we see the street outside through a window, but most of the film concentrates on the characters gathered around the room’s central table. On stage, we can imagine the table at the center and the major characters assembling around it but leaving one side clear, facing the audience–in effect, accepting the convention of the invisible fourth wall that gives us access to the space.

As the still above suggests, it seems initially that Oliveira is playing up this convention, putting us into the stage space and setting the fourth wall behind us. Very soon, though, we’re inserted between the players, so that we see the other side of this lantern-lit playing space.

For the most part, the first stretch of conversations and soliloquys among Gebo, Doroteia, and Sofia are played out in this planimetric, clothesline layout. So is the late-night arrival of the vagrant João, coming to sit opposite his father and laughing wildly. This shot corresponds to the end of the play’s first act.

On the next day, when Gebo and his family receive some friends, the table is sliced in half.

The effect is to redouble the sense of proscenium space, presenting two planimetric arrays that always keep one “behind” us.

Like other chamber-plays-on-film (Dreyer’s Master of the House, Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder), Gebo varies its spatial premises slightly to incorporate other possibilities. In the stretch corresponding to the second act of the play, the angle on the table changes twice, once to present the split table-scene above, and later, to the climactic moment when João joins Sofia and contemplates breaking open the strongbox.

Sometimes we’re shown the window and other walls, usually presented when characters leave one shot and enter another. The constructive editing helps us tie together zones of the room that aren’t ever given in an all-encompassing master shot. And the camera never moves, not even to reframe characters’ gestures.

In previous films, Oliveira has played with the ambiguities of who’s looking where. (See, for instance, Eccentricities of a Blonde-Hair Girl and The Strange Case of Angelica.) After a mysterious prologue involving João, a ravishing image presents Sofia watching at the window, then moving aside to reveal Doroteia behind her (and behind us).

As often happens, the start of a film sets up an internal norm; it teaches us how to watch it. This movie starts with a lesson in optical geometry. Sofia watches the street, goes out to scan for Gebo’s arrival, then watches Doroteia from outside the window before coming back in and resuming her position at the window. As the shot develops, we can see Doroteia lighting a lamp and reflected in the window against the distant doorway.

When Sofia walks out of the shot, Oliveira’s camera lingers on the window, in which we can still see Doroteia turning her head to watch Sofia’s coming to her. This is the shot, imperfectly reproduced, that’s at the top of today’s entry. The image isn’t far from the gently insistent changes of Koreeda’s Maborosi. This film about a shadow starts with an image of a spectre.

Constructive editing often relies on a glance offscreen, so here he can play with minute differences of eye direction. Occasionally the actors look directly out at us. But when the table is halved, as above, the eyelines get very oblique, with opposite characters looking in the same direction.

In the third act, the frontal and planimetric grouping around the table returns. Gebo has searched fruitlessly for João and has returned to take the consequences of his son’s theft.

Oliveira’s adaptation omits the play’s fourth act, when the family is reunited three years later. His version leaves the family suspended in a freeze-frame, haunted by the ghostly son who has betrayed their trust. This dramatic climax is also a visual one, with sunlight for the first time spilling into the chilly, lamplit parlor and its inhabitants startled, as if they shared João’s guilt.

Perhaps more than the other films in this entry, Jebo and the Shadow shows why we need film festivals. Oliveira’s purified experiment demands a lot from the audience, but it repays our efforts. It’s at once an engrossing story and an exciting exercise in what cinema can still do. Note as well that I have managed to get through a discussion of Oliveira’s film without mentioning his age.

For more on the film, see Francisco Ferreira’s very helpful essay in Cinema Scope.

Finally, Alan Franey has announced his departure from the job of Director of the Vancouver International Film Festival. He’s going out on a high note. This year’s edition was a solid success, and its spread to venues around town seems to have brought a wider audience. For twenty-six years Alan has led the process of making the festival one of the best in North America. He has helped give it a unique identity as home to Canadian cinema, documentaries on the arts and the environment, and outstanding current Asian cinema.

Finally, Alan Franey has announced his departure from the job of Director of the Vancouver International Film Festival. He’s going out on a high note. This year’s edition was a solid success, and its spread to venues around town seems to have brought a wider audience. For twenty-six years Alan has led the process of making the festival one of the best in North America. He has helped give it a unique identity as home to Canadian cinema, documentaries on the arts and the environment, and outstanding current Asian cinema.

For Kristin and me, he has been a wonderful friend and good-humored company. Alan’s deep commitment to great cinema has shown in his recruitment of colleagues, his skilful defusing of potential crises (most recently the shift to digital projection), and his genial, almost Zen, good nature. Fortunately for the festival, he will remain as a programmer. He deserves our lasting thanks.

Good news for US audiences on some of these titles: Sundance Selects will distribute Like Father, Like Son, while Kino Lorber has wisely acquired rights for A Touch of Sin. Gebo and the Shadow is available on an English-subtitled DVD from Fnac and Amazon.fr. It’s a very dark movie, and in order to make the frames readable here, I’ve had to brighten them a bit. These images don’t do justice to what I saw in the VIFF screening, or even to what the fairly decent DVD looks like.

For more on planimetric staging of the sort we find in Gebo and Maborosi, see entries here and here and here. It’s a common resource of modern cinema, and directors utilize it in a variety of ways.

Les trois désastres (2013).

Observations on Filmart (This is not a typo)

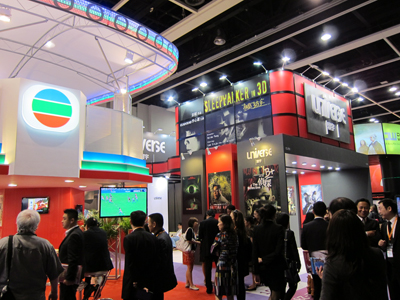

A modest display at Filmart, Hong Kong Convention Centre.

DB here, channeling an apparently apocryphal Soupy Sales line:

Kids, what starts with f and ends in art? No, not that. It’s Filmart, the annual trade gathering that kicks off the Hong Kong Film Festival. Add a space and a capital, and you have the main title of one of our books. Sometimes accidental cross-promotion can work out pretty well, as you see above.

Seriously, though, Filmart is a wonderful event. It includes an opening ceremony to launch the festival, the Asian financing forum known as HAF, the Asian Film Awards (covered a bit here), and a teeming meet-and-greet that sponsors panels, lunches, and hundreds of booths that allow media buyers and sellers to get together. I’ve covered Filmart in 2007, 2008, 2009, and 2010. Here are some comments and images from last week’s edition.

The shebang started with the ceremony introducing some of the opening films and their stars. Here the Filmart’s official hostess, Miriam Yeung, is about to go onstage to greet the audience.

And here at the ceremony are the three stars of Don’t Go Breaking My Heart, Gao Yuanyuan, Daniel Wu, and Louis Koo.

Ho Yuhang’s clever neo-noir Open Verdict was a highlight of the shorts collection Quattro Hong Kong 2. Here he is with his star, the radiant Kara Wai Ying-hung, Shaw Brothers action queen and star of both Open Verdict and Ho’s earlier feature Daybreak.

Filmart’s main business takes place in a vast hall, with companies’ displays lined up in rows and along aisles. Most firms have fairly modest stalls, but others are flamboyant, like these big boys for Mei Ah and Universe, two long-established Hong Kong production/ distribution companies.

But the place isn’t so big that you can’t run into old friends, like Margaret Pu (far right) and her colleagues Jack Lee and Dan Zhu from the Shanghai Film Festival.

More movers and shakers: Patrick Frater, CEO of Film Business Asia, and Peggy Chiao, producer (Trigram Films) and doyenne of Taiwanese New Cinema.

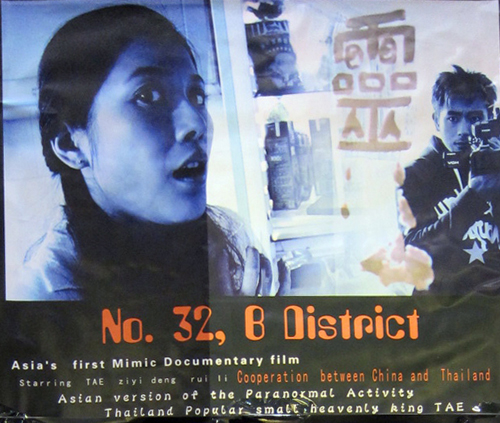

At Filmart one can always find some unclassifiable items, as witness the project pictured at the very end of this entry.

New Action on the Mainland

Most panels ran opposite film screenings, so I usually plumped for the movies. But I did attend an intriguing session on “Beyond Box Office: China: The World’s Largest Developing Market.” Sponsored by the Hong Kong Film New Action committee and moderated by Shanghai media executive Bill Zhang Ming, the panel included many Chinese figures and the American Ted Perkins, who has worked for both Warners and Universal and is now serving as executive VP of production for IDG China Media.

Some of the themes discussed echo things I talked about in the added chapters of Planet Hong Kong, but I garnered some new information as well.

*Several panelists pointed out that the stupendous growth in the Chinese box office, over 50% each year, demands that many new cinemas be built. The major cities have now got a good supply of screens, but now the third- and fourth-tier cities need to have more screens. Some commentators spoke of a “new five-year plan” aiming to upgrade and increase the nation’s screens.

*As in America and other countries, a few films typically garner the lion’s share of receipts; one panelist estimated that 80% of income stems from 20% of the films. For the foreseeable future, the big films, from China or the US, will drive the market.

*The growth of the market is even more remarkable given the comparatively small audience (around 20 million, one panelist surmised). Average ticket price is 32 renminbi, or about US$4.88.

*Hong Kong remains essential to the mainland market but also vulnerable. Films with local stars and directors can succeed, and Hong Kong is a key site for financing and packaging projects. But purely local films will remain low-budget items; the bigger films will be mainland co-productions, with some PRC talent and scenery on the screen.

*The popular audience, according to screenwriter-producer Qi Hai, is driven by female tastes: date movies are chosen by the woman, and family films are picked by mothers.

*Ted Perkins pointed out that although recent growth is good for all players, in any film industry there are always more funds in production than can be recouped overall. There will be winners and losers, especially if there’s an overabundance of production, as there currently is on the mainland. Although about 500 films were produced last year, more than half did not find theatrical release or screen in the best cinemas. (Panelists’ estimates of unseen or underseen titles varied from 250 to 400.) Marcus Lim provides a comparable set of figures.

*Some panelists opined that the market lacks directors and stars who are likely to provide success. One panelist estimated that only half a dozen directors have strong track records, and only one star, Ge You, can guarantee an audience.

*Most panelists agreed that 3D was not viable for most films, but in China the new format can help the business in an unusual way. Historically, most mainlanders couldn’t afford going to films, so they aren’t in the habit of attending theatres. They watch films on video or on the Net. Curiosity about 3D may attract new cinemagoers, “educating” spectators to the pleasures of seeing movies on the big screen.

*Most big countries have a well-structured pattern of “windows,” whereby a film moves from the theatre to video, cable, and online. But in China, the expansion of screens is occurring simultaneously with the growth of online distribution, with the danger of piracy. The Chinese will have to come to grips with decisions about pricing and more stable windows.

Seldom do we have a chance to realize that we’re witnessing a historic change in the global film industry. The rise of China is such an event, and film historians should be watching the unfolding process closely.

Changing the film ecology

The Jockey Club Cine Academy, formed last summer, is an educational enterprise guided by the HKIFF Society and funded by the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust. It’s a three-year program aiming to increase film literacy among young people. The Academy held a major event during Filmart, a nearly three-hour master class with Jia Zhangke, director of Platform, The World, Still Life, and most recently I Wish I Knew. High school students made up a large part of the audience.

Researcher and editor Wong Ain-ling (above, with Jia) interviewed him about his career and then opened things up for questions. Here are a few points Jia made.

*His recent turn toward documentary filmmaking isn’t a new development for him. When he was starting out, documentaries were the most dynamic part of the PRC film scene. Although the films captured aspects of contemporary life ignored by mainstream movies, they were seldom watched by audiences. So the question for Jia became: “How to change our film ecology?”

He has used a documentary project to spark a fiction feature. In Public (2001) became a draft for Unknown Pleasures. Jia enjoyed eliminating dialogue and narration from his documentaries, relying on peoples’ faces and situations to convey ideas. Critics complained that documentarists couldn’t tell stories, but he wanted mainland audiences to learn to find the latent emotions in the scenes, the “poetic” side of realistic cinema.

*His early films incorporated popular music, including Taiwanese tunes sung by Teresa Teng. Why? During the 1980s and 1990s, mounted loudspeakers broadcast a lot of Mandarin pop songs, making this music just part of a city’s ambience. This was something he exploited in his first feature, Xiao Wu.

*Jia had arguments with censors on his first three features, and those films weren’t widely seen. But in 2004, the censorship system changed, mostly for the better. Yet distributors still block films shot on video from being shown in cinemas, creating what Jia called a “technical censorship.”

*The reports are true: He is making a martial arts film with Johnnie To’s Milkyway firm. Jia wants to examine the imperial system in the period around 1900. He would like to follow it with another historical film, this one about Hong Kong in 1949, centering on two characters, a Communist and a KMT Nationalist.

Like Hong Kong itself, Filmart has a pulsating energy and offers an overwhelming array of choices: you can watch movies, attend events, and just gawk. You must run to keep up. That’s as it should be.

For more coverage of industry doings at Filmart, see Liz Shackleton’s rundown at Screen International (may be proprietary). Another story in Screen International mulls over the prospect that China could fairly soon become the world’s biggest market. See as well several items at Film Business Asia, particularly Stephen Cremin’s article on Chinese coproductions. For our takes on some Jia Zhangke films, you can go to this category.

PS 31 March (HK time): I should have mentioned what the New Action panel did not: Piracy. The LA Times has a good recent article on DVD bootlegging in the PRC, raising the crucial factor I’ve heard mentioned as well: the role of the People’s Liberation Army.

Venues and visions

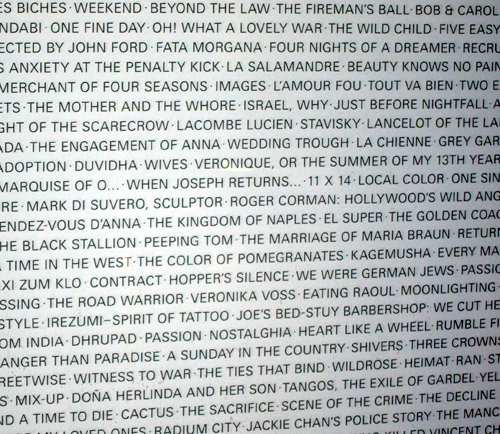

Vitrine outside future quarters of the Film Society of Lincoln Center (detail).

DB here:

During our month in NYC, we didn’t visit only art museums (although KT was at the Met a great deal). We also, no surprise, hit some of the city’s premiere movie spots. The places were often as impressive as the films, and all deserve the support of cinephiles both local and visiting. Herewith, a recap of our visits.

Fun things happen on your way through the Forum

Mike Maggiore, in the lobby of Film Forum.

Film Forum, running since 1970, has established itself as an outstanding venue for new releases and classics. It has done heroic work over the years. I stopped by to see my old Wisconsin friend Mike Maggiore, one of FF’s programmers, and met his colleagues, including Karen Cooper, a legend in US film culture. They had just recently had a remarkable triple-night string of visitors: Scorsese introducing his new documentary Public Speaking, Jerry Schatzberg with Scarecrow, and Paul Schrader with a fresh print of Diary of a Country Priest. The current FF program, running on three screens, is here and it’s very rich.

Uncle Boonmee will have hit FF by the time you read this. Chris Ware’s gorgeous poster decorates the Forum lobby.

The gem of Astoria

Under MoMI projection, Rachael Rakes (Assistant Film Curator), David Schwartz (Chief Curator), KT, Ethan de Seife (Professor, Hofstra).

The refurbished Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria is a thing of great beauty. Family-friendly, with lots of hands-on kid activities, it also offers a bounty to the cinephile.

For one thing, it has a superb screening theatre. We sampled it when MoMI screened a pretty print of King Hu’s The Valiant Ones (1975). Kristin and I were happy to see our old favorite again.

The same hall gave us a restoration of Manoel de Oliveira’s Doomed Love (1978). The movie, 4 ½ hours long, was shot in 16mm for television. It frankly acknowledges its novelistic source by including stretches of letters and florid declamation (“I will be dead to all men, except you, Father!”), as well as a plot turning on forbidden love and oppressive social relations. This is a world of parlors, convents, trusty servants, candlelit rooms, barred windows, and lovers who actually waste away. The title could apply to virtually every character, down to the maidservant who adores our protagonist and vows, “When I see I am not needed, I will end my life.” The affair draws others into its downward spiral, leaving the hero plenty of time to reflect on his misery and the pain he has inflicted on others.

The plot is quite engrossing in the manner of a triple-decker novel. That makes it all the more surprising that we get no Viscontian spectacle or even the plush upholstery of a Masterpiece Theatre episode. The presentation is rather dry and detached. I wondered if Ruiz’s recent Mysteries of Lisbon, drawn from another novel by Camilo Castelo Branco, was in effect a reply to Oliveira’s film. By comparison with Ruiz’s sparkling compositions and glissando flashbacks, Doomed Love looks reticent and austere.

The austerity is heightened by a self-conscious stylization. The music is aggressively modern, and the lengthy takes (the average shot runs about a minute) are often shot with the low, straight-on camera reminiscent of early cinema.The film begins with a partial view of a door opening, inviting us into the story world, but obliquely. The film closes with a hand lifting a bundle of love letters from the sea and a voice-over (Oliveira’s) explaining how the novel came to be written. The images provide as overt a marking of a narrative’s beginning and its end as you could ask for, and one completely in keeping with the film’s balance between respect for artifice and its concern to let compromised passions leak through.

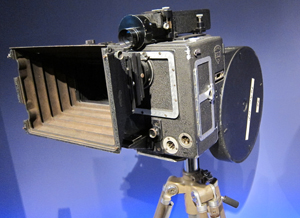

MoMI also hosts a splendid exhibition of media technology. One floor is a wonderland of cameras, sound rigs, printers, and projectors of all sorts, from film to TV and beyond. One favorite among many: A Mitchell VistaVision camera from 1954. It’s a funny-looking thing, but it took very crisp pictures. The horizontal film transport allowed larger and sharper images than the vertically-run formats that were normal for 35mm.

There are also displays devoted to screenplays, make-up, hairdressing, and special effects. I was especially taken with the finely detailed miniature for the Tyrell corporation building in Blade Runner.

In all, MoMI deserves all the praise it has gotten after its reopening. Rochelle Slovin, the founding director of the museum, started in 1981 and is retiring this week. She can be proud of what she and her colleagues have accomplished.

Jaywalking down Broadway

Wundkanal (Thomas Harlan, 1984).

Then there’s Lincoln Center, another long-time shrine of cinephilia. Like MoMI, the Film Society is in the process of building. The new complex will house theatres, a café, and a flexible lobby space. It’s scheduled to open in late spring.

The Film Society’s František Vlácil retrospective early in our stay brought this little-known filmmaker to my attention. I had seen only his best-known item, Marketa Lazarova (1967), and that quite a while back. So I was happy to catch his charming early short, Glass Skies (1958), and three features.

Vlácil mastered both filmic poetry and prose. The White Dove (1960) is a simple, lyrical story of two young people who never meet: a girl living in a beachside town and a wheelchair-bound boy in the city. Alternating sequences show them brought together by the homing pigeon that the girl sends out. The boy in a moment of thoughtless cruelty shoots the pigeon with his air rifle. Soon, with the help of an artist living in the same apartment house, he nurses the bird back to health. The film is richly shot in crisp, wide-angle black-and-white, and Vlácil exploits eyeballish imagery to create links between the girl’s seaside milieu and the artist’s Chagall-like paintings.

Like most filmmakers moving from the 1960s to the 1970s and from black and white to color, Vlácil recalibrated his visual design. Smoke in the Potato Fields (1976) gets your attention from the start with its disconcerting cutting during an airport departure. Laconic and elliptical, shot with long lenses and long takes, it tells an understated story of a middle-aged doctor moving to a small-town clinic. We get a cross-section of the townsfolk, from ambulance driver and gravedigger to censorious nurse and an unhappy married couple. The central drama concerns the doctor’s care for a tomboyish girl who gets pregnant and considers an abortion.

Shadows of a Hot Summer (1977), set in 1947 and shortly before the Communist takeover of the Ukraine, is more conventionally gripping. A farm family is held prisoner by rapacious resistance fighters. The taciturn father has no allies among the locals, who seem to resent his prosperity, and he dares not call attention to his plight. As in a Boetticher film, the hero plays his hand judiciously, mostly passive but carefully picking the battles he can win. The final sequence, precipitated when the marauders find him hoarding shotgun shells, is a taut, suspenseful exercise in action cinema. Shadows of a Hot Summer has daring stretches of silence and an unsettling score, along with discreet zoom shots typical of the period worldwide. These installments in the Vlácil retrospective show that we nonspecialists still probably underestimate the range of artistry that could be achieved in the apparently inhospitable atmosphere of Communist Eastern Europe.

Film Comment Selects brought us a host of strong items, of which I caught four. I had missed Jia Zhangke’s I Wish I Knew (2010) at Vancouver, so I was happy to catch up with it. It seems to me a moving but minor effort in his career, lacking the bolder organization of the comparable Useless (2007; the latter in our blog here) and 24 City (2008). I didn’t think that the figure of the wandering woman Zhao Tao, punctuating people’s recollections of life in Shanghai, developed very much. Still, I was struck by how much Jia’s interviewees were able to say about the effects of the Cultural Revolution on their lives, and there is an unforgettable account by a woman of her father’s execution at the hands of the KMT.

Film Comment Selects brought us a host of strong items, of which I caught four. I had missed Jia Zhangke’s I Wish I Knew (2010) at Vancouver, so I was happy to catch up with it. It seems to me a moving but minor effort in his career, lacking the bolder organization of the comparable Useless (2007; the latter in our blog here) and 24 City (2008). I didn’t think that the figure of the wandering woman Zhao Tao, punctuating people’s recollections of life in Shanghai, developed very much. Still, I was struck by how much Jia’s interviewees were able to say about the effects of the Cultural Revolution on their lives, and there is an unforgettable account by a woman of her father’s execution at the hands of the KMT.

I’m a big fan (at a distance) of the Chauvet caves and their Ice Age imagery, so Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010), a 3D tour of the site, was right up my alley. The film turned out to be a strong argument for 3D (as Kristin anticipated), since it lacked that sense of cardboard-cutout planes you usually get and really brought out volumes. The tigers, bison, and other wondrous creatures seemed to bulge and ripple across the walls.

The biggest revelation the Film Comment program held for me was the double bill of Thomas Harlan’s Wundkanal (Gunwound, 1984) and Robert Kramer’s Notre Nazii (Our Nazi, 1984). Wundkanal was made by Thomas Harlan as part of his crusade to expose the bad faith of postwar Germany, where many former Nazis held positions of power. Harlan’s father was the Nazi filmmaker Veit Harlan, and as Kent Jones pointed out in his illuminating introduction, the son seems to have taken upon himself the burden of guilt that his father should have felt.

Wundkanal proposes that a terrorist gang has kidnapped the respectable citizen Dr. Seibert, interrogated him about his murderous past, recorded the sessions on videotape, and eventually staged some of their own suicides as part of the exercise. Dr. S. is played by Alfred Filbert–himself a Nazi let out of prison for medical reasons. The whole production, then, becomes both a vision of Germany’s blindness to history and a trap for a man whom Thomas Harlan suggests has gotten off far too easily. “A new idea: to use the real criminal, to deceive him and convince him it was a film about him.”

Filmed by the great Henri Alekan, it is a phantasmagoria. We are in a sunless bunker jammed with old photos, thermos jugs, automatic pistols, video clips from a Harlan film, and other detritus: a sort of chamber-play version of a Syberberg no-man’s land. Questioned by offscreen interrogators, Dr. S. admits to his crimes plaintively. The hallucinatory quality of the exercise is enhanced by sound cuts that split a sentence into bits (sometimes clear and close, sometimes filtered through speakers) and a drifting camera that may start on Dr. S. but then wanders across the litter to end on a video image of Dr. S. testifying in another session, at which point the sound of that session may take over. In one passage, the camera tours the room and picks up several bits of Dr. S.’s testimony, in the real space and in several video monitors crowding the area.

Kramer’s Our Nazi is in a way a making-of for Wundkanal, but it’s also a powerful film in its own right. Acting as his own cameraman for the first time, Kramer (director of the classic militant films The Edge, Ice, and Milestones) takes us behind the scenes to show Thomas Harlan’s obsessions and to expose Filbert more directly than Wundkanal does. Harlan talks of the fatal love he had for his father, reflecting that the old man’s charm finally withered in the face of his inhuman complicity with the Reich. Intercut with this soliloquy are shots of Filbert being made up for his video scenes, as he talks of his dueling scars and his youth: “All the ambitious men became Nazis.”

Our Nazi gives us two disturbing confrontations, one with Kramer sitting Filbert down and charging him with crimes against humanity, the other more prolonged and painful. Harlan and the crew encircle their star and hurl accusations at him. This scene, glimpsed and abstracted in Wundkanal, pulls the viewer in different directions as the feeble old man tries to escape Harlan’s relentless recitation of Filbert’s war crimes. In the discussion with Kent Jones after the screenings, Paul McIsaac rightly called the Kramer film a demonstration of the concreteness that direct cinema can yield. Shot in Hi-8, Our Nazi counterbalances the abstract, somewhat detached artifice on display in Wundkanal. Kramer dwells on unexpected details, such as Alekan hesitating to autograph a souvenir production photo for old Filbert. The two movies need to be seen together because they engage in a crosstalk that yields provocatively different information, emotions, and cinematic resources.

Our month in New York went by all too fast. We seldom visit the city these days; I’m in Hong Kong more often than Manhattan. Our trip brought back memories of my undergrad visits from Albany in the 1960s (packing four films into a day-trip) and, during the 1970s, doing dissertation research and visiting friends and teaching for a semester at NYU. It also allowed me to get back in touch with some of my oldest friends, like Rich Acceta-Evans from junior-high days. And the trip reminded me of what a cosmopolitan film culture is like, with institutions like these and still others (Anthology Film Archives, MoMA, etc.) braving tough times to bring the right movies to lucky audiences.

Apart from those named above, I want to thank the friends we met with during our stay. Scott Foundas was particularly helpful on this entry. I gave talks at various venues, so I’m grateful to Malcolm Turvey of Sarah Lawrence College, to the NYU Film Studies faculty, and to Patrick Hogan at the University of Connecticut–Storrs. Special thanks to Ken Smith and Joanna Lee for arranging a visit to the Museum of Chinese in America for a discussion of Planet Hong Kong.

Speaking of Planet Hong Kong, I discuss The Valiant Ones in Chapter 8 there, as well as in the essay “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse,” in Poetics of Cinema. For a sensitive examination of Doomed Love, go to Tativille.

Some films in the Film Society’s Vlácil retrospective are available on DVD from Facets Multimedia. Wundkanal and Our Nazi have been issued on a single DVD edition with English subtitles, and it can be found on the Edition Filmmuseum site. Every film studies and filmmaking department should order it, I believe. See also “Truth or Consequences,” Kent Jones’ essay in Film Comment 46, 2 (May/ June 2010), 48-53, from which I’ve taken the Harlan quotation. Jones discusses other films, including Christoph Hübner’s 2007 study of Thomas Harlan, Wandersplitter, which is also available on a Filmmuseum disc. Thomas Harlan is one of the main interviewees in the documentary Kristin recently wrote about, Harlan: Im Schatten von Jud Süss.

For more coverage of the “Film Comment Selects” series, see R. Emmett Sweeney’s review on the Movie Morlocks site, with particularly discerning remarks on I Wish I Knew. Jesse Cataldo provides sharp commentary on Wundkanal at The House Next Door.

Alfred Filbert, confronted with the tattooed arm of an Auschwitz survivor (Our Nazi).