Archive for the 'Directors: Keaton' Category

The ten best films of … 1924

Die Nibelungen: Siegfried

Kristin here:

For a seventh year running, we skip ranking the current year’s films and instead hark back 90 years.

We started out with a list that was essentially an appendix to an entry, but soon we were dedicating whole entries just to the list. Our entries for past years are here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, and 1923.

These lists are our way of calling attention to important silent films that some readers may have overlooked. In one case here we point out a largely forgotten film that deserves to be better known, in the hope that an archive will take the hint. With the proliferation of silent-film festivals, of DVD and Blu-ray releases with restored prints and supplemental material, and of TCM’s eclectic screenings of foreign and silent titles, there seems to be considerably more interest in these early classics. Herewith our choices for 1924.

For the last few years I’ve struggled to fill out the full list of ten films with truly deserving items. But as I’ve been predicting, the 1924 choices fell easily into place. As usual, some of these are obvious picks, already famous to most readers. Others are less obvious, and a few are unknown except to specialists. Some, though very important historically and artistically, are not currently available on DVD, which is a real shame.

At last, the USSR

Films in the Soviet Montage style make up one of the most important cinema movements of all times. The key filmmakers of the movement, Eisenstein, Pukovkin, Dovzhenko, Kuleshov, Kozintzev and Trauberg, and others began their work later than the German Expressionist and French Impressionist directors. But at last one joins our list, with Lev Kuleshov’s The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks.

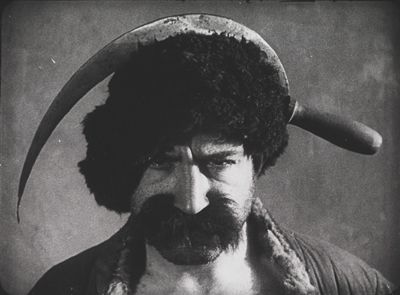

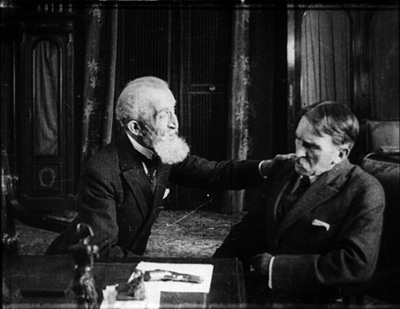

Although Kuleshov’s work has become more widely available, his most familiar work is still By the Law (1926), a grim tale of two members of a gold-prospecting team agonizing over how to bring to justice a colleague who has committed a terrible crime. Mr. West couldn’t be more different. This hilarious and grotesque comedy satirizes American perceptions of the new Soviet Union, as Mr. West, president of the YMCA, comes to for a visit, his faithful cowboy friend Jeddie in tow. They’re terrified of the barbaric land they expect to encounter, and a gang of thieves dupe Mr. West by dressing up in outfits that caricature West’s images of Bolsheviks (above).

In making the film, Kuleshov and his team drew upon the experiments they had been doing in his classes he ran of the early 1920s. Film stock was scarce and all he and his students could do was practice staging scenes and make short editing experiments. They explored the possibilities of “biomechanical acting,” a style based more on gymnastic control and energy than on psychological subtleties of facial expression.

Once the group did get the resources to make a feature, their delight is evident in the lively editing and the exuberant performances. Alexandra Khokhlova, a gangly woman who was married to Kuleshov and starred in most of his films, plays a vamp who tries to lure Mr. West into her toils. Pudovkin, who studied with Kuleshov before going into directing himself, is the well-dressed gang leader who pretends to guide Mr. West away from danger. Boris Barnet, also to become a major director, performs feats of derring-do as Jeddie tries to save Mr. West.

Mr. West is not only a satire on Western fears of post-Revolutionary Russia but also a parody of American serials. (The latter was something Barnet soon tried in an actual serial, his 1926 Miss Mend.)

Mr. West is available on DVD in Flicker Alley’s set, “Landmarks of Early Soviet Film.”

German Expressionism begins to wind down

Last year I was hard put to pick a film to represent the German Expressionist movement in the top ten. I chose Erdgeist but mentioned Schatten and Raskolnikow as runners-up. By 1924 there were fewer Expressionist films released, though the movement would linger on until 1927, mainly carried on by the two greatest directors who had worked in the Expressionist movement: F. W. Murnau and Fritz Lang. Each of these contributed a classic film in 1924: Murnau’s The Last Laugh and Lang’s two-part epic: Die Nibelungen: Siegfried and Kriemhild’s Revenge).

The Last Laugh isn’t really Expressionist. The sets are mildly in the style, but what really fascinated Murnau at this point was the freedom of camera movement introduced by French Impressionism. He set out to make a character study. Emil Jannings plays a doorman in a large hotel (none of the characters’ names are given). His regal bearing and fancy uniform bring him respect among his fellow employees and from relatives and neighbors in the lower-middle-class neighborhood where he lives. He has aged to the point where he carry large luggage and is abruptly demoted to work as a rest-room attendant.

Murnau introduced what came to be known in Germany as the entfesselte Kamera, the “unfastened camera,” beginning in the opening shot where an elevator with a grill descends, carrying the camera and dramatically revealing the lobby. Murnau may have been directly influenced by one of last year’s top-10, Cœur fidèle, where Epstein put his camera on a spinning-swings carnival ride. Murnau saw other uses for the device. Like the Impressionists, he conveyed drunkenness through moving camera, though in this case he put the actor and camera on a turntable, so that the room spins past behind Jannings, conveying the dizzy happiness of the doorman at a party (above).

Using more imagination, Murnau follows sound with his camera. As the party ends, musicians exit to the apartment-block courtyard, and one plays a final tune under the window. Starting with a close-up, the camera “cranes” diagonally up and backward until the men are in long shot. A cut takes us to the doorman inside, happily listening.

Actually the camera was not on a crane. Murnau and cinematographer Karl Freund affixed a track over the courtyard with a small metal elevator underneath, so that the camera could move both back and forth and up and down. The camera was not literally unfastened in these cases, but it looked like it was.

Murnau wanted to end the film on a grim note with the protagonist seated alone in the hotel rest room. Commercial considerations led to a happier ending, however, with him unexpectedly becoming wealthy. The twist was so outrageous that Carl Mayer, the scenarist, considered it a comment on Hollywood’s insistence on happy outcomes. Hence the English title The Last Laugh. The original German means “The Last Man.”

The Last Laugh got distribution in the USA, but it was not a success. Hollywood practitioners studied it, though, and started hanging cameras from tracks themselves and trying other tricks. The track backward above a long, laden banqueting table soon became a cliché of Hollywood cinema.

Murnau would make two more mildly Expressionist films, Tartuffe (1925) and Faust (1926) before heading to Hollywood to make the ultimate hanging-camera film, Sunrise (1927)

The Last Laugh is available from Kino in the USA and Eureka! in the UK.

One of my favorite films of the 1920s is Lang’s two-parter, Die Nibelungen: Siegfried and Die Nibelungen: Kriemhilds Rache (Kriemhild’s Revenge). An adaptation of the ancient German myth, it mostly proceeds at a stately pace until the final battle scene. Some may find it slow, especially when compared with the lively, suspenseful Dr. Mabuse der Spieler (1922) and Spione (1928). Yet its leisurely presentation is appropriate to the subject matter. Equally important, lingering over images allows us to notice the details of the extraordinary settings and costumes, with their busy decorated surfaces and their startling arrangements within the shot.

Take the image at the top of this entry. Brunhilde, having been forced to marry King Gunther against her will, envies her sister-in-law Kriemhild, who has married Siegfried, the man Brunhilde loves. In this shot, Brunhilde mounts the steps of Worms Cathedral to confront Kriemhild and assert her right to enter the cathedral first. We see her from behind and then at the upper left as her ladies follow her, wrapped in their patterned hoods and black cloaks, creating an almost abstract composition. Lang build the enormous stairway outside the cathedral in two stages and then used the set imaginatively to stage several ceremonies and dramatic conflicts.

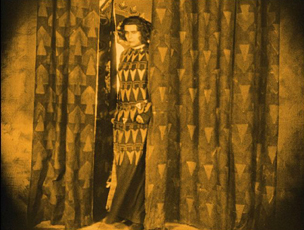

What makes this film Expressionist, I would argue, is the way the actors and settings interact, as in this moment when Brunhilde pauses by her window and then comes forward through the slightly parted curtain, exiting left. She pauses in the opening, her dress seemingly becoming part of the curtains for a moment.

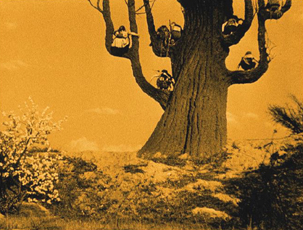

The similarity and the pause have no narrative function, but it’s a very Expressionist composition. Insistent symmetry and acting also contribute to the style. In the second plot, the Hunnish King Etzel asks for Krienhild’s hand in marriage. She agrees on the condition that he will aid her in exacting her revenge on Siegfried’s killers. Upon her move to the land of the Huns, the style becomes a more familiar sort of Expressionism, with distorted trees and buildings that looks like they were built of mud that settled oddly before drying:

The elements of the German tales are all here: love, betrayal, suicide, revenge, presented in images worth savoring.

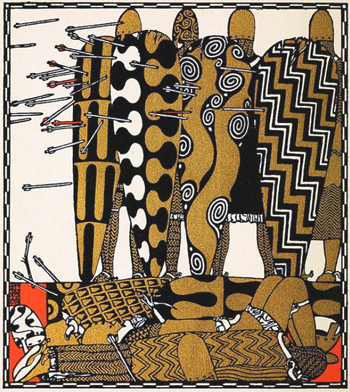

Lang was inspired in his approach to the film’s visuals by some illustrations by Carl Otto Czeschka for a 1909 retelling of Die Nibelungen published in 1909. The heavy decoration on the knight’s shields and many other surfaces in the film somewhat resemble this image, for example:

Yet the resemblance is far from exact. Clearly Lang used elements from these illustrations and took them off in his own direction.

The film has recently been restored and looks great on Blu-ray. Kino in the US and Eureka! in England have brought it out. Both have DVD editions as well.

Scandinavia’s golden age drawing to a close

During the first half of the 1920s, the Swedish cinema was a victim of its own success. Victor Sjöstrom (who has figured in these lists in 1918 and 1921, as well as in our “Lucky ’13” entry), had headed to MGM, becoming Victor Seastrom. In 1924 he released his first two films in 1924: Name the Man and He Who Gets Slapped. The latter was the newly formed MGM’s first in-house production to be released. It was a huge success, no doubt in large part due to the growing stardom of Lon Chaney, and it put the studio on the map and allowed Seastrom to stay in Hollywood, notably for The Scarlet Letter (1926) and The Wind (1928).

Mauritz Stiller (also a previous top-10 choice) was about to head for Hollywood as well, but his final Swedish film is one of his finest. Gösta Berlings Saga, a epic adaptation of Selma Lagerlöf’s novel, was made in two parts lasting over three hours. Many people will know it as the debut film of Greta Garbo. Fans should be forewarned that she is an important character and appears in the early and late scenes but disappears for a long stretch in the middle.

[December 30: As our friend Antti Alanen points out, Garbo had already acted in a comedy, Luffar-Petter (Peter the Tramp, 1922) and in some short advertisements.]

The film begins with Berling, a drunken pastor in a small town, being relieved of his duties. He ends up being taken in the “Chevaliers” at Ekeby the country estate of Margaretha Samzelius, a tough middle-aged woman who runs a group of foundries she has inherited from a lover. The Chevaliers are a group of hangers-0n, men who can drink and laze about most of the time but who must be charming and entertaining at Samzelius’ many dinner parties. Berling has a number of chances to redeem himself but ends up harming the people around him and sinking lower into despair. He is finally redeemed by the love of the Garbo character, Elizabeth, the new bride of a wealthy neighbor, to whom, it turns out through a technicality–and happy coincidence–she is not actually married.

Hansen and Garbo make a gorgeous couple (below left), but they are upstaged by the great Swedish stage actress Gerde Lundequist as Samzelius:

As usual, the film contains lovely scenes in the Swedish landscapes. There are some impressive night sleigh rides, including a famous scene in which Berling and Elizabeth are chased across a frozen lake by wolves. There is also one of the most impressive fire scenes I can recall from the silent era, as Samzelius’ efforts to smoke the Chevaliers out of the guest house where they live and inadvertently sets fire to the big main house as well.

Unfortunately the film was cut down into a single feature for its release outside Scandinavia. The Story of Gosta Berling was the main version that circulated for many years. The Swedish Film Institute restored it in stages as more footage was found, but the current print, at 183 minutes, is still missing some footage.

Beware picking up an older video release with the truncated film. The restored version was released on DVD in the USA by Kino. The original Svensk Filmindustri release (with English, French, Portuguese, German, and Spanish subtitles), is available here. The same DVD comes in a box set of six Swedish silent classics, which is widely available from the usual online sources.

Carl Dreyer has popped up on this blog several times, usually in passing. Not surprising, since David wrote a book about him way back 1981. Here he makes his second appearance on our ten-best lists (the first having been for his first feature, The President, in 1919) with Michael.

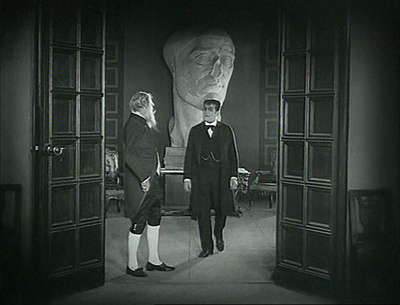

The film centers around a wealthy, aging artist, Claude Zoret. The main room of his house is decorated with several eye-catching pieces of sculpture, notably a mysterious battered head that looms in the background of many shots. Is it one of Zoret’s own works? Is it part of a collection of ancient statues? Much of the action takes place here, which has led some historians to place Michael in the tradition of the Kammerspiel. David calls it a borderline case. There are certainly scenes that leave Zoret’s studio, most notably one in a large theater set.

The film has been hailed as an early treatment of homosexuality. Although there is nothing overtly expressed, it is hard not to read such a subtext into the action. Zoret, wonderfully played by Danish director Benjamin Christensen, has many guests and admirers visit him, creating a little all-male coterie. He has taken in a young protegé, a very beautiful and very young Walter Slezak. Zoret refers figuratively to Michael as his son, but there seems to be another tie between the two. Moreover, there may be a hint that Charles Switt, a journalist apparently writing a biography of Zoret (at the center of the frame above), feels some jealousy toward the young man.

Trouble begins when a princess comes to commission a portrait from Zoret. Although he usually doesn’t do commissions, he is intrigued by her face and agrees. During her visits to the studio to pose, she meet Michael, who is immediately smitten. The affair continues as Michael becomes increasingly inconsiderate to Zoret,borrowing money to continue the affair and missing an important showing of his work. In contrast, Zoret shows unwavering generosity to Michael, despite being devastated by his desertion.

Ultimately Zoret paints his last work, showing an elderly, lonely man against a barren seascape. It is hailed as a masterpiece at a party which Michael does not attend.

The character study proceeds at Dreyer’s usual formal pace, and yet it is never dull. As much as any of his silent films, it looks forward in tone to his later sound ones.

A very nice print of Michael is available in the UK from Eureka! (not deliverable to the USA); Kino released what I assume is the same print in the USA.

She was nothing but a poor flower-maker

Every now and then I want to put a film on the list which is impossible to see unless you happen to live near one of the archives that has a print and they happen to program it. Still, in the hope of inspiring someone to restore it and make it available, I proceed.

The film is Jean Epstein’s L’Affiche (“The Poster”). Epstein first made our list last year for the much better known Cœur fidèle. L’Affiche is a bit like the earlier film, a simple melodrama made in the French Impressionist style. Its situation is highly conventional, and its plot depends on a massive coincidence.

The heroine is introduced as Marie, one of several women making artificial flowers. On her lunch break she thinks back to a romantic day she spent in the country. There she meets a young man, Richard. The couple go to an expensive restaurant, and Richard seduces Marie, and then abandons her, driving away alone the next morning.

Three years pass, and Marie has a small child, also named Richard. She enters him in a contest for the most beautiful child, with a cash prize, offered by an insurance company that wants to put the winner on their advertising posters. The boy wins, and Marie signs a 10-year contract for the rights to use little Richard’s image.

The child dies, however, and Marie visits his grave. As she leaves, she sees a huge poster with his image. The campaign has begun. Everywhere in Paris she goes, she sees the poster and finally begs the insurance company to end the campaign. The boss, however, refuses. Marie begins tearing down the posters, and she is soon arrested. Epstein handles the arrest scene without an establishing shot but builds it up through close-ups.

Initially we see only the back of Marie’s head and her arms tearing down a poster. There a cut-in to slightly closer framing as a policeman’s hand comes into the shot and touches her shoulder. A third shot shows her turning to the officer and staring in a way that suggests she is becoming mentally unbalanced. Finally a long shot establishes the scene as a second policemen enters to help arrest her.

It’s the sort of gradual revelation of space that Kuleshov was working with at the same time.

The boss of the insurance company is informed of this and sends his son to file a complaint against her. New copies of the poster are being put up all over town. The son is none other than the Richard who seduced Marie years before. Hearing her tale, he asks her forgiveness and takes her home to his parents. The father forbids their marriage, they marry anyway, and eventually (after his own younger child dies!), the boss blesses the marriage and agrees to take down the posters.

Summarized baldly, it sounds like an impossible plot to take seriously, but Epstein’s delicate, understated approach in presenting it and Nathalie Lissenko’s affecting performance as Marie manage to make it a great film. It’s full of Impressionist moments: Marie’s memory of her romantic day with Richard, a dance scene with rhythmic editing, a dream sequence, and plenty of gauzy shots and fancy wipes at transitions.

Earlier this year I complained because L’Affiche was not included in the big new box set of Epstein’s work, despite almost everything else from the period being there. It’s also not on the box set of films made at the Russian emigré studio, Albatros, even though Epstein’s other three Albatros films are there. I don’t whether there are rights problems or there simply isn’t a good enough print.

At least one streaming service claims to have L’Affiche available, but a search turns up numerous complaints about the site.

I should make mention of one other Impressionist film that came out in 1924. Perhaps it should be on the list rather than L’Affiche. It’s Marcel L’Herbier’s L’Inhumaine. L’Herbier appeared on our 1921 list for El Dorado, and even then I expressed reservations. Most of his films seem cold and by-the-numbers to me, not to mention a bit pretentious. But his films were historically important, and L’Inhumaine was influential in its use of art deco sets. At one time the film was available on DVD, but it seems to be out of print.

Three funny men …

And no, it’s not Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd this time. Chaplin didn’t release a film in 1924. His next would be what many would consider his funniest feature, The Gold Rush.

Over the years I’ve stressed that during the 1910s, the three great comics were working in shorts, honing their filmmaking and working up to their great series of features. By 1923 they had fully made the transition: Lloyd made Safety Last and Keaton Our Hospitality. Safety Last had a simpler plot, structured mainly by the stages of the hero’s climb up a building. Keaton went further with a complex story of a romance blooming between members of feuding families, using multiple locations, a developing causal line, and clever motifs. (We analyze it in Chapter 4 of Film Art: An Introduction.)

In 1924, Lloyd achieved a similar complexity with Girl Shy, one of his greatest films. He plays a bashful young tailor’s assistant who is terrified of women. Yet in secret he writes a guide for seducers, taking on the narrational persona of a jaded man of the world. Clearly he has taken his inspiration from movies of the day. The imaginary scenes from his book dramatize his success in gaining the love of a vamp (see bottom) and a flapper. The publishers decide that the book is so over the top that they will publish it as a comic story. During all this Harold develops a relationship with Mary, a quiet young woman from a wealthy family. When her father tries to buy Harold off, he pretends to spurn Mary. She is about to marry a rich man, but Harold determines to stop the wedding.

There develops one of the most epic chase scenes in all silent comedy, and indeed all cinema, as Harold commandeers all manner of vehicles, from cars and wagons to a firetruck and a speeding trolley (above).

Even Keaton never outdid that one. But from 1923 to 1927, these two each created a string of innovative, carefully crafted, hilarious films.

Girl Shy used to be available in a 3-DVD set from New Line, but that is no longer available–though one optimistic third-party seller offers it, still sealed in plastic, for $399.99). Now the individual releases of each DVD seem to be slipping out of print as well. Volume 1, which contains Girl Shy, is definitely out of print. Be forewarned: Volume 2, which includes the wonderful 1927 film The Kid Brother (look for it on a future list) seems like it’s not long for this world, and the same is true of Volume 3, with For Heaven’s Sake (1926).

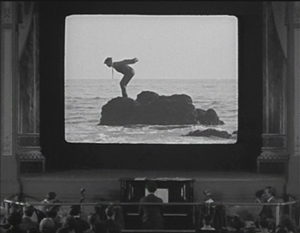

It was difficult to choose between Keaton’s two major releases of 1924, Sherlock Jr. and The Navigator. I chose the former mainly because of its perpetually astonishing transition from the frame story of a small-town projectionist unlucky in love to his dream of himself as a sophisticated detective. His dream takes the form of a movie, and the sleeping projectionist walks through the theater and into the onscreen action. With extraordinary precision, Keaton maintains a long-take framing of the pianist and audience in the auditorium while the hero onscreen undergoes a series of unexpected shot changes. In each he is in the same pose and position within the screen, but the backgrounds change arbitrarily, as when he begins to dive from a rock into the ocean and finds himself landing in a snowdrift:

The result is a marvelously convincing technical feat, giving the illusion of being a single shot as far as the theater is concerned and on the movie screen a character wandering through an appropriately dream-like series of edited shots. In general, Keaton was the most adept of the three great comics at using cinema technology to create gags, and this is his most elaborate attempt. (Though see also his short, The Playhouse, in which multiple exposures, flawlessly managed in-camera, create Keaton clones that play all the roles.)

The plot of the dream emerges after this virtuoso transition, and it remains hilarious throughout. The chase, while not quite as dazzling as the one in Girl Shy, has considerable variety of vehicles (one wonders if the two comics were consciously trying to best each other), including a passage where the hero rides the handlebars of a speeding motorcycle, unaware that the driver has fallen off.

Kino has packaged Sherlock Jr. together with Keaton’s early feature, The Three Ages (1923), and released them both on DVD and Blu-ray.

The third funny man was Ernst Lubitsch. The Marriage Circle was his second Hollywood film, and one of his best. Lubitsch had started out as a comic in silent shorts in Germany, but unlike the famous Americans, he entirely gave up acting to direct. Not that he directed only comedies, but his best films, including Lady Windermere’s Fan, Trouble in Paradise, and The Shop around the Corner, fall into that category.

The Marriage Circle is a light romantic comedy, following a chain of flirtations and misunderstandings. Prof. Stock has realized that his pretty young wife Mizzi has begun to neglect and nag him. She is soon attracted a newlywed, Dr. Braun. Mizzi happens to be an old friend of Braun’s wife Charlotte, which gives her opportunities to flirt aggressively with Braun. Charlotte is in turn admired by Braun’s medical partner, Dr. Mueller, though she laughs off his attempts to woo her.

It has often been pointed out that Lubitsch is a director of doorways. That’s not always true, but The Marriage Circle is built around visits. The five characters visit each other in various combinations, and the string of attempted seductions and jealousies builds. Stock encourages Mizzi’s pursuit of Braun, since he wants an excuse for a divorce. Charlotte naively pushes Braun into visiting Mizzi at home when she plays sick.

The sets and especially the doorways play a big role. Characters pause in doorways to take in a compromising situation they have interrupted. At one point Mizzi comes to Braun’s office. Mueller spots them in an embrace, but Braun claims he’s hugging his wife. Eager to alienate Charlotte from her husband, he opens the office door to reveal Charlotte in the waiting room:

This is the first film where one can see the “Lubitsch touch” in action. It’s an ability to use film techniques to hint at something naughty. Here the innuendos are aimed at the characters. We know more than any of them does, and the humor arises from watching them misinterpret what they see and hear. When they finally learn of their mistakes, they end the “circle” of the title.

The Marriage Circle is available to rent or buy in digital form on Amazon. I know nothing about the source or the quality. The only DVD easily available is a region 2 French one under the rather blah title Comédiennes. The print is distinctly soft (as the frame above suggests) but acceptable until a better one becomes available.

… and one not so funny

Greed is often spoken of as the film that historians and buffs would most like to see rediscovered. Part of it survives, of course–about two hours out of the original eight or so. Its producer, MGM, had it was edited down into a reasonably coherent feature, mainly by cutting out a number of characters and their subplots. I won’t say much about the film here, since it is already quite well-known.

The film is an adaptation of Frank Norris’ novel McTeague done in a naturalistic style, which was unusual for Hollywood films of that or any other day. It follows McTeague, an unlicensed dentist, who steals his friend Marcus’ girlfriend, Trina, and marries her. Their luck fluctuates, as Trina wins a lottery and McTeague is thrown out of work for not having a license. Trina becomes an obsessive miser, and McTeague, by now an alcoholic, murders her and flees to Death Valley with her money.

I find a lot of Greed heavy-handed and obvious. (I prefer the simpler Blind Husbands, which made our ten-best list for 1919.) It has an interesting style, however, with a lot of proto-Wellesian deep focus and low angles, complete with, in the case of the frame above, a hint of a ceiling. The final sequence in Death Valley is also very effective.

Apart from being 75% lost, Greed has never been released on DVD. (See Indiewire for comments on this.) In 1999 Turner Classic Movies edited a four-hour version, inserting production stills to suggest the missing scenes. This was reasonably effective, but it seems impossible to find a print of it that is not washed out and fuzzy. We’ve tried taping off TCM, as well as buying the VHS and laserdisc releases of that version. They all verge on unwatchable. I hope that the situation is not left where it is and that a true restoration is eventually done. My frame above comes from an archival 35mm print, so clearly better material exists.

The lost film that I would most like to see discovered is Lubitsch’s Kiss Me Again (1925). Given that it was made right before Lady Windermere’s Fan, there’s a good chance that it’s a masterpiece.

One of a kind

Last year I put Man Ray’s experimental short, La retour à la raison, on the list. Comparing experimental shorts to fiction features, though, seems unfair. This year I’m separating out the experimental category and will try to choose at least one film each year.

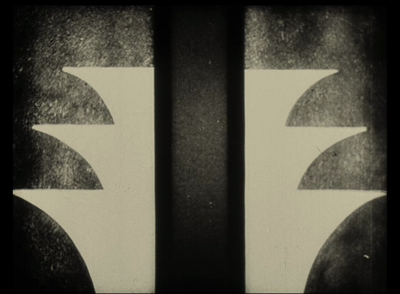

This year it’s Walter Ruttmann’s Opus 3, the third of his four films done with abstract animation.

All of the Opus films plus other Ruttmann shorts are available on a DVD set with Berlin, die Sinfonie der Grossstadt and Melodie der Welt. If you want to sample just Opus 3, which is about four minutes long, it has been posted multiple times on YouTube. Although a bit dark, this is the best copy I’ve found, and it has a nice, appropriate score by Hanns Eisler.

Bernard Eisenschitz made the connection between Lang and Czeschka in his massive Fritz Lang au travail (Cahiers du Cinéma, 2012) , pp. 38 and 42. Czeschka’s Nibelungen illustrations can be see along with the entire book on the Museum of Modern Art’s website, with a page-turning feature and the ability to enlarge the pages considerably. Individual illustrations can be found with a Google Images search on “Czeschka” and “Nibelungen.”

Thanks to Jonah Horwitz for a correction.

Girl Shy

The ten best films of … 1921

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

Kristin here:

To end the year, we’re continuing our tradition of picking the ten best films not of the current year but of ninety years ago. Our purpose is twofold. We want to provide guidance for those who may not be particularly familiar with silent cinema but who want to do a bit of exploring. We also want to throw in occasional unfamiliar films to shake up the canon of classics a bit.

Like last year, it was strangely difficult to come up with ten equally great films. There were some obvious choices, but beyond them there were a lot of slightly less wonderful items jostling for the other places on the list. The problem had several causes. Some master directors who routinely figure in our year-end ten choices had off-years. In 1921 D. W. Griffith released only one film, Dream Street, a notably weak item. (What I have to say about it can be found on pp. 108-113 of the British Film Institute’s The Griffith Project, Vol. 10.) Ernst Lubitsch released two films that seem like less interesting attempts to repeat earlier successes: Anna Boleyn (a pale imitation of Madame Dubarry) and Die Bergkatze (nice, and I was tempted to include it, but it’s less amusing than the Ossi Oswalda comedies, here and here). Cecil B. DeMille’s The Affairs of Anatol is not nearly as well structured as his earlier sophisticated rom-coms.

In other cases, films simply don’t survive. John Ford released seven films in 1921, all of which are lost.

Death comes calling, twice

Probably the easiest decision was to include The Phantom Carriage (also known as The Phantom Chariot), by Victor Sjöström. As I noted recently, the Criterion Collection has recently issued a beautiful restoration of it (DVD and Blu-ray).

When I first saw The Phantom Carriage, I was probably still an undergraduate. Given its reputation as a great classic, I was somewhat disappointed. No doubt it was partly the battered 16mm copy I watched, but the film is a bit formidable for someone not accustomed to the aesthetic of silent cinema–and especially of the great Swedish directors of the era. Its protagonist, played by Sjöström himself, is a thoroughly, determinedly unlikeable fellow, and the complex flashback structure can be a bit disconcerting on first viewing. But the effort to watch until one “gets” Sjöström is well worth it, since he’s undoubtedly one of the half dozen greatest silent directors.

The story opens on New Year’s Eve with Edit, a young Salvation Army volunteer, on her deathbed. She unexpectedly begs her colleague and mother to fetch the town drunk, David Holm, to her bedside. At the same time, Holm sits drinking in a graveyard as midnight approache. He tells two fellow inebriates the legend of the phantom carriage, the vehicle that picks up the souls of the  newly dead; it is driven each year by the last person to die at the end of the previous year. Holm then dies, and the carriage arrives, with its current driver ready to turn over the job to him. Flashbacks enact both the circumstances of how the heroine met Holm and the happy family whom Holm had alienated through his drunkenness.

newly dead; it is driven each year by the last person to die at the end of the previous year. Holm then dies, and the carriage arrives, with its current driver ready to turn over the job to him. Flashbacks enact both the circumstances of how the heroine met Holm and the happy family whom Holm had alienated through his drunkenness.

It’s a deeply affecting story, wonderfully acted and staged. In most scenes the lighting and staging are impeccable, and the famous superimpositions that portray the carriage and the dead are highly ambitious for the period and impressively executed. The filmmakers have managed to make the carriage, superimposed on real landscapes, appear to pass behind rocks and other large objects. In short, a film that has everything going for it.

Death himself appears in Der müde Tod (literally “The Tired Death,” often called Destiny, or occasionally in the old days, The Three Candles). Here the great German director Fritz Lang hits his stride, and you can expect him to figure on most of our lists from now on.

In Destiny (available on DVD from Image Entertainment) a young woman’s fiancé is killed early on. Death, a sympathetic figure who regrets what he must do, gives her three chances to find another person whose demise can substitute for her lover’s. The three episodes in which she tries take place in Arabian-Nights Baghdad, Renaissance Venice, and ancient China; each story casts her as the heroine and her lover as the hero.Things don’t go well, and Death actually gives her a fourth chance when she returns to the present.

This was Lang’s first venture into the young German Expressionist movement, which had been launched the year before with Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. The style shows up only intermittently, perhaps most dramatically in the Venetian episode when the lover shinnies up a rope along a wall painted with a gigantic splash of light. (See bottom.)

Each film has a “happy ending.” I leave it to you to determine which is grimmer.

I’m turning over the keyboard to David now, to describe a film he knows better than I do.

More Northern European drama

Mauritz Stiller alternated urban comedies (Thomas Graal’s Best Film, 1917; Thomas Graal’s Best Child, 1918; Erotikon, 1920) with more lyrical dramas and romances set in the countryside (Song of the Red Flower, 1919; Sir Arne’s Treasure, 1919). Johan (1921) is in the pastoral vein. Its integration of landscape into the drama suggests it was an effort to recapture the production values that overseas critics had praised in Sjöström’s Terje Vigen (1917) and The Outlaw and His Wife (1918). Like the Sjöström films, however, Johan offers more than splendid spectacle; it’s the study of the undercurrents of a marriage.

At the core is a love triangle. The fisherman Johan is the somewhat thick-headed son of a domineering mother. He is fond of the girl Merit, whom he and his mother rescued as a waif and brought into their household. But this synopsis is actually skewed, because Stiller and the scriptwriter Arthur Norden have told the story in an unusual way.

At the core is a love triangle. The fisherman Johan is the somewhat thick-headed son of a domineering mother. He is fond of the girl Merit, whom he and his mother rescued as a waif and brought into their household. But this synopsis is actually skewed, because Stiller and the scriptwriter Arthur Norden have told the story in an unusual way.

We’re introduced to the couple by following the rogue Vallavan’s entry into the town; Johan seems almost a secondary character until Vallavan leaves. When Johan breaks his leg, Merit agrees to be his wife. Now we’re attached to her standoint and see her life of drudgery under the petty tyranny of Johan’s mother. Vallavan returns, and Merit falls under his spell. Taking her hand, he says, “I want to rescue you.” After she has fled with him, Johan clumsily wanders the rocky shore. “Will I ever see Merit again in this life?” The narrational weight passes to him as he decides to pursue the runaways.

Like Sjöström’s Sons of Ingmar (1918-1919), Johan presents marriage as a trap for unwary women. Our shifting attachment, from Vallavan to Merit and eventually to Johan, allows us to see the situation in many dimensions. As a sort of parallel, Stiller makes fluid use of the now solidly-established conventions of continuity editing. Vallavan’s seduction of Merit is played out in tense shot/ reverse-shot, and there’s an engrossing moment involving delicate shifts in point of view. When the bedridden Johan sees Merit leaving, after his mother has cast her out of the house, he must smash a window pane with his elbow in order to call to her. Stiller’s dynamic eyelines, direction of movement, and precise changes of camera setup here show that he had mastered the American style.

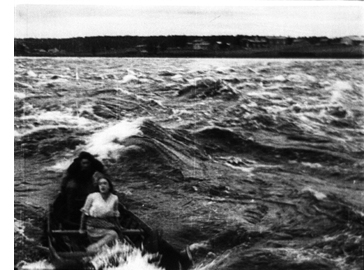

Alongside this finesse, there is still plenty of outdoor action, highlighted when Vallavan rows Merit away in the tumultuous river. Filmed from another boat, the actors are all but engulfed by the waves. It was presumably scenes like this that the parent company, Svensk Filmindustri, hoped would attract international attention. At this period Svensk, dominant in the local industry, was hoping to sell its films on a global scale. That ambitious plan failed, but it left us with many outstanding movies and soon brought Stiller, along with Sjöström, to Hollywood.

Johan is available on a Region 2 PAL DVD, coupled with Kaurismaki’s Juha, another adaptation of the Juhani Aho story.

The joys of small-town life

Last year I included two films by William C. deMille, the considerably less famous brother of Cecil B. The year 1921 saw the release of what is today his best-known film, Miss Lulu Bett. It was based  on the popular novel and play by Wisconsin author Zona Gale, who received her MA here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and in 1921 became the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for drama. The story centers around the heroine, a spinster who lives with her sister’s family, including her niece, nephew, and brother-in-law, Dwight Deacon. Dwight is a tyrant who delights in taunting Lulu over her unwed status, and the rest of the family treats her as a servant.

on the popular novel and play by Wisconsin author Zona Gale, who received her MA here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and in 1921 became the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for drama. The story centers around the heroine, a spinster who lives with her sister’s family, including her niece, nephew, and brother-in-law, Dwight Deacon. Dwight is a tyrant who delights in taunting Lulu over her unwed status, and the rest of the family treats her as a servant.

The return of the husband’s globetrotting younger brother Ninian after a twenty-year absence injects some life into the situation. Taking the family out to dinner, he realizes just how boring the family is (right), and to liven things up, suggests that he and Lulu perform mock marriage vows. Dwight realizes that the ceremony is legally binding, and, already attracted to Lulu, Ninian suggests that they treat it as a real marriage. Desperate to escape her dreary situation, Lulu agrees. The relationship proves agreeable, and Lulu declares that she will learn to love Ninian–when he reveals that he had previously been married, though he doesn’t know whether his first wife is dead (in which case he and Lulu are married) or alive (in which case they aren’t). Unwilling to take a chance, Lulu returns to the Deacons, who consider her disgraced and treat her even worse.

The film avoids melodrama. Ninian is not a villain; he’s kind to Lulu and sorry for the position he’s placed her in. It remains to Lulu to summon the gumption to leave the family and find her own happiness.The whole thing is told with restraint and little touches of humor that draw the viewer into a deep sympathy with Lulu’s plight.

Lois Wilson’s performance as Lulu is crucial in this. She is at once plain enough that we can believe she is in danger of becoming an old maid and pretty enough to plausibly attract the attention of the handsome local schoolteacher. Wilson’s most prominent role came two years later, when she starred as the heroine in James Cruze’s The Covered Wagon.

Miss Lulu Bett is the only one of William’s films available on DVD, paired with Cecil’s Why Change Your Wife? As so often happened, William seems to take a back seat to his famous brother, but the pairing is a logical one, in that William wrote the script for Why Change Your Wife?

Another small-town drama of the same year is Lois Weber’s The Blot. In 1981, when I was teaching a course on American silent film at the University of Iowa, I wanted to quickly demonstrate to the students that the silent period was not an era of exaggerated acting and naively melodramatic plots. I showed a double feature of The Blot and King Vidor’s Wine of Youth (1924). The latter portrays changing sexual mores through the story of three generations of the same family, with a young woman of the Roaring Twenties questions the necessity of marriage when she discovers that her mother is contemplating divorce. I think Wine of Youth (unfortunately not available on video) and The Blot convinced my class that silent films could be both sophisticated and subtly acted.

The “blot” of Weber’s title refers to the notion that people in professions depending on intelligence and education are poorly paid, while tradespeople and children from rich families are well off. The representatives of the underpaid are a college teacher, Prof. Griggs, and a young, idealistic minister. The parallels to recent events are striking. College professors may not be so badly paid as in the 1920s, but the move toward institutions of higher learning depending on adjunct lecturers has created a similar issue. In general, the income gap is familiar: the rich young wastrels taking Prof. Griggs’s course represent what we now call the one percent, while the professor and minister live on a much lower plane.

Weber’s drama is not quite this bald, however. Various levels of prosperity are represented. The professor’s family lives in shabby gentility, his wife grimly struggling to keep food on the table and his daughter Amelia, in delicate health due to a lack of nourishing food, working in the local library. Their neighbors are the family of a successful shoemaker, who live well but lack education. The shoemaker’s wife in particular resents what she perceives as intellectual snobbishness in the professor’s family and takes every opportunity she can to flaunt her comparative wealth.

Her son, however, has a crush on Amelia, as does the poor minister. Into this situation comes Phil West, the professor’s rich but indolent and mischievous student. Also attracted to Amelia, Phil for the first time encounters real poverty and is  shocked by it. As the plot develops, Amelia falls ill, and her mother’s increasingly desperate efforts to obtain the food necessary to nurse her to health become one of the main threads of the drama. To say that a large part of the action in the second half of the film centers on Mrs. Griggs’s temptation to steal a chicken from her neighbors might make the situation seem a trifle comic, but Margaret McWade’s remarkable performance vividly conveys the wife’s struggle in the face of real lack and her humiliations in the eyes of the shoemaker’s gloating wife. When Mrs. Griggs succumbs to temptation, the result is a brief but wrenching scene.

shocked by it. As the plot develops, Amelia falls ill, and her mother’s increasingly desperate efforts to obtain the food necessary to nurse her to health become one of the main threads of the drama. To say that a large part of the action in the second half of the film centers on Mrs. Griggs’s temptation to steal a chicken from her neighbors might make the situation seem a trifle comic, but Margaret McWade’s remarkable performance vividly conveys the wife’s struggle in the face of real lack and her humiliations in the eyes of the shoemaker’s gloating wife. When Mrs. Griggs succumbs to temptation, the result is a brief but wrenching scene.

The plot is remarkably dense and unpredictable. Every scene involves glances that lead to new knowledge or serious misunderstanding, deflecting the plot into new directions. Early on it is impossible to say which of the three young men Amelia will end up with, and even by the late scenes, when only two plausible romantic candidates remain, we have no idea which she will pick. As in many of Weber’s films, she does a bit of preaching about the social problem involved, but in The Blot she leaves this until near the end and gets it over quickly and fairly believably. The considerable but gradual change in Phil’s attitude toward education and the problems of poverty is also made believable. The prosperous neighbor’s change of attitude may seem a bit sudden, though it is somewhat motivated by a line early on.

But on the whole, even more than with Miss Lulu Bett, this is an absorbing story with characters for whom we care. Weber uses motifs as skillfully as any director in the early phase of the classical Hollywood cinema. Watch in particular how many different ways she uses the Griggs family’s cat and her two kittens: to demonstrate the family’s poverty, to be the main means of the neighbor lady’s spite, to introduce some comedy, and so on. Even more pervasive is the way that shoes become tokens of characters’ various social positions.

The Blot is available on DVD from Image. Those interested in Weber as a director should note that next summer’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna plans a retrospective of her work.

Which is best? Damfino.

In past year-end lists, we’ve watched Harold Lloyd, Charles Chaplin, and Buster Keaton creeping toward their great features of the 1920s. This year two of them move cautiously into longer films, and the other releases two more terrific one-reelers.

The Boat is one of Keaton’s most admired shorts. In it, he, his wife, and their two young sons build a boat, the Damfino, and unwisely launch it on the open ocean. Everything that can go wrong does: the life-preserver sinks, the anchor floats, and naturally a storm hits. The wife’s pancakes aren’t edible, but one temporarily patches a leak. Throughout the intrepid band carries on against all obstacles.

Less perfect but more dazzling and (perhaps) funnier is The Playhouse. The premise of a small variety theater creates an episodic, messy narrative, but it allows Keaton to play out a series of four “acts.” Initially we see Keaton buy a ticket and enter an auditorium where the audience, the orchestra, and all the performers are played by “Buster Keaton.” As one of the audience members remarks, “This fellow Keaton seems to be the whole show,” which is true in more way than one. The multiple images of Keaton were accomplished entirely in the camera, by cranking back the film with precise timing and uncovering a different part of the lens at each pass. The precision when one Keaton figure talks to or dances with another is amazing.

This all turns out to be a stagehand’s dream. (Keaton being the stagehand.) The multiplication motif returns as an act involving two pretty girls who happen to be twins–something Buster  doesn’t know, making his encounters with them ever more baffling. Later an orangutan escapes, and Buster dons make-up and costume to replace him. All hilarious stuff, though unfortunately the final act, a Zouave Guard drill, is the least funny one. Still, it’s a terrific film with a big dose of the surrealist quality that will run through the later shorts and the features.

doesn’t know, making his encounters with them ever more baffling. Later an orangutan escapes, and Buster dons make-up and costume to replace him. All hilarious stuff, though unfortunately the final act, a Zouave Guard drill, is the least funny one. Still, it’s a terrific film with a big dose of the surrealist quality that will run through the later shorts and the features.

The Boat is included on Kino’s disc of The Navigator and The Playhouse with their out-of-print DVD of The General. Still in print, however, is Kino’s eleven-disc set of the features and shorts. For those in the UK and other region-2 countries, Eureka! has a “Masters of Cinema” three-disc set, “Buster Keaton: The Complete Short Films 1917-1923,” which includes many of his earlier films with Fatty Arbuckle.

The year saw Lloyd and Chaplin make their first feature films, though both releases were still fairly short. I’m not really counting A Sailor-Made Man as one of the top ten of the year, since it’s a delightful but decidedly light item. Just another reminder that Lloyd is inching toward greatness.

Lloyd presents his “glasses” character as a brash young man who impulsively proposes to a rich man’s daughter. When the father demands that he get a job to prove his worth, Harold enlists in the navy. Highjinks ensure, culminating in a lively chase-and-rescue scene when the heroine gets kidnapped by a lecherous Arabian sheik.

Lloyd presents his “glasses” character as a brash young man who impulsively proposes to a rich man’s daughter. When the father demands that he get a job to prove his worth, Harold enlists in the navy. Highjinks ensure, culminating in a lively chase-and-rescue scene when the heroine gets kidnapped by a lecherous Arabian sheik.

The shipboard scenes allow Harold to get in some funny bits, mainly involving him trying to be tough and succeeding at first by sheer accident. Later, however, he is inspired by the heroine’s danger to become a real rescuer. It’s a sign of bigger things to come.

New Line’s Harold Lloyd boxed set is out of print, but you can still get the volumes separately. A Sailor-Made Man is in Volume 3, along with such delights as Hot Water and For Heaven’s Sake.

Chaplin’s first feature, The Kid, is a skillful blend of the rough-and-tumble slapstick that had characterized his early shorts and the sentimentality that would gradually become a more prominent trait of his films. A unmarried woman (played by Edna Purviance, the elegant beauty who made such a contrast with the Little Tramp in many of his films) abandons her infant in an expensive car which happens to get stolen moments later. Charlie finds the baby, and after numerous attempts to get rid of it–including a brief contemplation of an open storm-sewer grate–decides to raise it. The baby grows into the adorable and amusing Jackie Coogan.

Chaplin’s first feature, The Kid, is a skillful blend of the rough-and-tumble slapstick that had characterized his early shorts and the sentimentality that would gradually become a more prominent trait of his films. A unmarried woman (played by Edna Purviance, the elegant beauty who made such a contrast with the Little Tramp in many of his films) abandons her infant in an expensive car which happens to get stolen moments later. Charlie finds the baby, and after numerous attempts to get rid of it–including a brief contemplation of an open storm-sewer grate–decides to raise it. The baby grows into the adorable and amusing Jackie Coogan.

In the meantime, the mother has become a rich singer, and coincidentally she comes to the slums doing charitable work. The authorities eventually try to remove the Kid to an orphanage, and later a flop-house proprietor turns him in to receive a reward. Still, Chaplin doesn’t milk the pathos, and a happy ending duly arrives.

The Kid is available in a decent print along with A Day’s Pleasure and Sunnyside on the “Charlie Chaplin Special” DVD. Our recording off Turner Classic Movies strikes me as being slightly better quality, so you might keep an open to see if they reshow it. It was also announced this week that The Kid has been added to the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress.

Fuzzy movies, big and small

Soft-style cinematography had been tried in some films of the late 1910s, most notably in Griffith’s Broken Blossoms. But in the 1920s it spread. In Hollywood, it was mainly a technique for making beautiful images and especially for creating glamorous close-ups of actresses. In France, it was a way of tracking a character’s inner life.

Vicente Blasco Ibáñez’s 1918 novel, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse was a huge bestseller, and the first film adaptation in 1921, directed by Rex Ingram, was equally successful. To many, it is remembered for having made a super-star of its main actor, Rudolph Valentino. Anyone who has seen him as the caricatured Latin Lover of his later films will be pleasantly surprised to discover that the man could act, as could his leading lady, the lovely Alice Terry.

Ingram was the quintessential middlebrow director of the 1920s, doing big-budget, respectable adaptations of popular literature (e.g., Scaramouche, The Prisoner of Zenda). To me, Four Horsemen escapes the stodginess of the later films, at least to some extent (as does his other 1921 film, The Conquering Power). It and the other film in this section were borderline cases, chosen as much for their historical importance as their quality, perhaps, but definitely worth watching.

One of Four Horsemen‘s greatest strengths is its photography. Ingram worked consistently with one of the greatest cinematographers of the 1920s, John F. Seitz, who created glowing images of  sets and actors with selective lighting and all sort of means of softening the image. This film, more than Broken Blossoms, brought the soft style into vogue. It eventually culminated in the Dietrich films of Josef von Sternberg before a more hard-edged look came to dominate the 1940s.

sets and actors with selective lighting and all sort of means of softening the image. This film, more than Broken Blossoms, brought the soft style into vogue. It eventually culminated in the Dietrich films of Josef von Sternberg before a more hard-edged look came to dominate the 1940s.

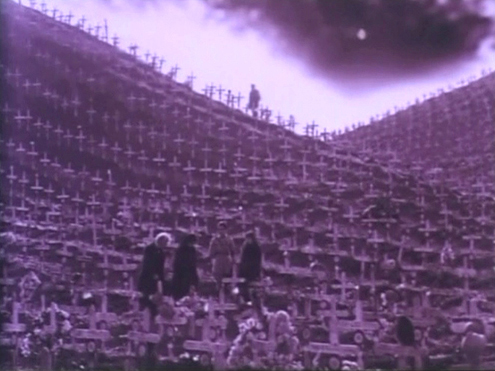

Four Horsemen was also an early entry in the anti-World War I genre of the 1920s and 1930s. Its final scene in a vast military cemetery of identical white crosses remains a powerful one. (See above.) Here, however, the Germans are still stereotypes, militaristic puppets with no redeeming features. Even that notion would gradually change, however, until nine years later All Quiet on the Western Front could recount the war from the German point of view.

Four Horsemen is available on DVD on demand from Amazon, supplied on DVD-R. In the same format, one can order it on a set with a documentary on Valentino. The reviews of the latter suggest that the visual quality is good.

(For more on this photographic style, see my “The soft style of cinematography,” in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, pp. 287-293.)

I’m not a huge fan of Marcel L’Herbier, and I’m not entirely sure that El Dorado is a full-fledged  masterpiece. But it has many virtues, and arguably it’s historically important as the first film of the French Impressionist movement to thoroughly explore ways in which camera techniques could convey perceptual and psychological states. It focuses largely on Sibilla, a singer-dancer who is the main attraction in a tawdry Spanish bar. She and some other women are performing as the story begins, but Sibilla is distracted by worries about her sick son. L’Herbier experimented with tracing her attention by placing gauzy filters over her face when she starts thinking of the boy. In the frame at the left, for example, she is in sharp focus when onstage, but as she passes into the backstage area, she goes fuzzy.

masterpiece. But it has many virtues, and arguably it’s historically important as the first film of the French Impressionist movement to thoroughly explore ways in which camera techniques could convey perceptual and psychological states. It focuses largely on Sibilla, a singer-dancer who is the main attraction in a tawdry Spanish bar. She and some other women are performing as the story begins, but Sibilla is distracted by worries about her sick son. L’Herbier experimented with tracing her attention by placing gauzy filters over her face when she starts thinking of the boy. In the frame at the left, for example, she is in sharp focus when onstage, but as she passes into the backstage area, she goes fuzzy.

In a way this is a somewhat silly, literal notion, and yet it’s exciting to see filmmakers exploring new devices relatively early in film history. Gauzy filters, distorting mirrors, slow-motion superimpositions, rhythmic cutting, and subjective moving camera were soon to be in common use by a small group of French directors. El Dorado was also the first film to be filmed within the Alhambra, which lends it considerable visual interest.

If we’re still writing this blog in 2019, our list will probably include the culminating film of the movement, and arguably L’Herbier’s best silent film, L’Argent.

Not many French Impressionist films are available in the U.S. If you have a multi-region player, El Dorado is paired with L’Herbier’s earlier L’homme du large (1920) on a French DVD.

Tigers and lepers and a mysterious yogi

We tend to think of serials as having many episodes and being low-budget additions to programs. That’s the American model, but in Europe things were different. Louis Feuillade’s serials are among the gems of the 1910s. In Germany, serials tended to have fewer episodes but bigger budgets–much bigger. Many were only two parts, most famously Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (coming next year to our top-ten list) and Die Nibelungen (coming in 2014). Lang had launched into serials with Die Spinnen (1919 and 1920). The two parts have terrific things in them, but Lang never went on to finish it.

He was, however, still collaborating on screenplays for director Joe May, who specialized in epic serials set in exotic countries and starring his wife, Mia May. Highly entertaining though these films are, they are largely forgotten, even by most lovers of silent cinema. Das indische Grabmal is the exception, though even now few have had a chance to see it. In 1996 it was shown at “Il Gionate del Cinema Muto” festival in Pordenone and was all too briefly available on an Image DVD (as The Indian Tomb) now out of print. Track it down if you can.

Full of the stars of its day, Das indische Grabmal is set largely in India, and its plot was inspired by the Taj Mahal. A ruthless maharajah (played with relish by Conrad Veidt) cloaks his cruelty under a veneer of European courtesy. He plots to shut his unfaithful princess (Erna Morena) in a beautiful tomb along with her lover (Paul Richter, better known to modern audiences as Siegfried). He calls in a famous European architect (Danish star Olaf Fønss) to build it, and the architect’s fiancée (Mia May), rightly fearing dirty work afoot, follows. One pit full of tigers and one of lepers lie waiting to endanger the visitors. The sets are beautiful. The Germans by this point could do them at full scale (above left) and as marvelously deceptive miniatures (above right). Das indische Grabmal is constantly entertaining and perhaps the best of its type, at least of the films we have access to.

Lang directed a two-part remake of this film in 1959. Both are good, but I prefer the silent one.

Some runners-up

As I mentioned, we had trouble narrowing down our list this year. Here are some others that could have replaced some of our prime choices. The German stage director Leopold Jessner adapted the play Hintertreppe (Backstairs). It’s a Kammerspiel, set in two apartments and the courtyard between them, and concerns a simple love triangle among a maid, her absent lover, and the postman who loves the maid so much that he forges letters from her sweetheart to keep her happy. Antti Alanen kindly reprinted my notes on the film here.

Carl Dreyer’s third feature, Leaves from Satan’s Book, remains one of the most widely-admired variants on the Intolerance formula of presenting thematically linked historical episodes. The dynamic final last-minute non-rescue shows that Dreyer learned a good deal from Griffith’s crosscutting too. Leaves is available on a Danish DVD with English subtitles and an alternate ending. Murata Minoru’s Japanese feature Souls on the Road, another exercise in complex crosscutting, and Feuillade’s polished L’Orphéline are solid runners-up as well. Neither is available on commercial DVD, as far as we know.

Destiny.

The ten best films of … 1920

High and Dizzy

Kristin here:

Three years ago, we saluted the ninetieth anniversary of what was arguably the year when the classical Hollywood cinema emerged in its full form. The stylistic guidelines that had been slowly formulated over the past decade or so gelled in 1917. We included a list of what we thought were the ten best surviving films of that year.

In 2008 we again posted another ten-best list, again for ninety years ago. This annual feature has become our alternative to the ubiquitous 10-best-films-of-2010 lists that print and online journalist love to publish at year’s end. It’s fun, and readers and teachers seem to find our lists a helpful guide for choosing unfamiliar films for personal viewing or for teaching cinema history. (The 1919 entry is here.)

There were many wonderful films released in 1920, but, as with 1918, I’ve had a little trouble coming up with the ten most outstanding ones. Some choices are obvious. I’ve known all along that Maurice Tourneur’s The Last of the Mohicans (finished by Clarence Brown when Tourneur was injured) would figure prominently here. There are old warhorses like Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari and Way Down East that couldn’t be left off—not that I would want to.

But after coming up with seven titles (eight, really, since I’ve snuck in two William C. de Mille films), I was left with a bunch of others that didn’t quite seem up to the same level. Sure, John Ford’s Just Pals is a charming film, but a world-class masterpiece? A few directors made some of their lesser films in 1920, as with Dreyer’s The Parson’s Widow or Lubitsch’s Sumurun. Seeing Frank Borzage’s legendary Humoresque for the first time, I was disappointed—especially when comparing it with the marvelous Lazy Bones of 1924. (Assuming we continue these annual lists, expect Borzage to show up a lot.) Chaplin didn’t release a film in 1920, and Keaton and Lloyd were still making shorts, albeit inspired shorts. Mary Pickford’s only film of the year, the clever and touching Suds, is a worthy also-ran. Choosing Barrabas over The Parson’s Widow or Why Change Your Wife? over Sumurun has a certain flip-of-the-coin arbitrariness, but we wanted to keep the list manageable. But they all repay watching.

The year 1920 can be thought of as a sort of calm before the storm. In Hollywood a new generation was about to come to prominence. Griffith would decline (Way Down East may be his last film to figure on our lists). Borzage will soon reach his prime, as will Ford. Howard Hawks will launch his career, and King Vidor will become a major director. The great three comics, Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd will move into features. In other countries, an enormous flowering of new talent will appear or gain a higher profile: Murnau, Lang, Pabst, Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Dozhenko, Kuleshov, Vertov, Ozu, Mizoguchi, Jean Epstein, Pabst, Hitchcock, and others. The experimental cinema will be invented, and Lotte Reiniger will devise her own distinctive form of animation. Watch for them all in future lists, which will be increasingly difficult to concoct

In the meantime, here’s this year’s ten (with two smuggled in). Unfortunately, some of these films are not available on DVD. They should be.

The great French emigré director Maurice Tourneur figured here last year for his 1919 film Victory. The Last of the Mohicans is just as good, if not better. I haven’t read the Cooper novel, set during the French and Indian War, but it’s obvious that Tourneur has pared down and changed the plot considerably. The sister, Alice, is made a less important character, with the plot focusing on two threads: the Indian attack on the British population as they leave their surrendered fort and on the virtually unspoken attraction between the heroine Cora and the Mohican Indian Uncas. The seemingly impassive gazes between these characters, forced to conceal their attraction, convey more passion than many more effusive performances of the silent period. The actress playing Cora also wore less makeup than was conventional, de-glamorizing her and making her a more convincing frontier heroine.

The film is remarkable for its gorgeous photography, with spectacular location landscapes, some apparently shot in Yosemite (below left). Tourneur’s signature compositional technique of shooting through a foreground doorway or cave opening or other aperture appears frequently (below right). (Brown’s account of the filming in Kevin Brownlow’s The Parade’s Gone By makes it sound as though he shot most of the picture, but in watching the film I find this hard to believe.)

Finally, the film stands out from most Hollywood films of its day for its uncompromising depiction of the ruthless violence of the conflict between the British and those Indians allied with the French. The scene in which the inhabitants of the fort leave under an assumed truce and are massacred can still create considerable suspense today, and the outcome puts paid to the notion that all Hollywood films end happily.

The word melodrama gets tossed around a lot, and many would think of much of D. W. Griffith’s output as consisting of little besides melodramas. But Way Down East is the quintessential film melodrama. An innocent young woman (Lillian Gish) is lured into a mock marriage and ends up deserted and with a baby. The baby dies and she finds a place as a servant to a large country family, where the son (Richard Barthelmess) falls in love with her. Her sinful status as an unwed mother leads the family patriarch to order her out, literally into the stormy night. She ends up on an ice flow, headed toward a waterfall. Along the way there’s comic relief from some country bumpkins and a naive professor who falls for the hero’s sister. It all works, partly because Griffith treats the main plot with dead seriousness and partly because Gish elicits considerable sympathy for her character.

Not only is it a great film, but it provides a window into the past, preserving a popular nineteenth-century play and giving insight into the drama of that era. It’s hard to think of another feature film that conveys such a genuine record of the Victorian theater, directed by a man who had made his start on the stage of the same period. (Unfortunately the film does not survive complete. The Kino version linked above is from the Museum of Modern Art’s restoration, which provides intertitles to explain what happens during missing scenes.)

Way Down East displayed a conservative attitude toward sex that was rapidly receding into the past–at least as far as the movies were concerned. The same year saw two films that set the tone for the Roaring ’20s in their more risqué depiction of romantic relationships: Cecil B. De Mille’s Why Change Your Wife? and Mauritz Stiller’s frankly titled Swedish comedy Erotikon.

De Mille has featured on our previous lists, for Old Wives for New in 1918 and Male and Female in 1919. Why Change Your Wife? ramped up the sexual aspect of the plot, however, as a Photoplay reviewer made clear: “”Having achieved a reputation as the great modern concocter of the sex stew by adding a piquant dash here and there to Don’t Change Your Husband, and a little more to Male and Female, he spills the spice box into Why Change Your Wife?” The plot is not nearly as daring as this suggests. Gloria Swanson plays a wife who is straight-laced and intellectual, driving her husband to spend time with a stylish woman who tries to seduce him. Yet he flees after one kiss, and after his wife divorces him on the assumption that he has cheated on her, he marries the seductress. The heroine discovers the error of her ways and becomes sexy in her dress and behavior. As a result the husband regains his old love for her, and they remarry. No actual adultery occurs, and the first marriage is affirmed with a happy ending.

Why Change Your Wife? may have seemed more daring because De Mille here externalizes the shifting relationships through the costumes to the point where no viewer could miss the implications. Initially the wife’s demure dresses mark her as prudish, while the woman who lures her husband away is dressed like a vamp. Once the wife lets go, she dons similar revealing, expensive designer clothes. As a result, the male members of the audience might revel in a fantasy of their ideal wife, and the women would delight in displays of fashions most of them could never own in reality. It proved a successful combination. We tend to forget it now, but the 1920s was full of variants and imitations of Why Change Your Wife?, often featuring a fashion-show scene that was nothing but a parade of models in outlandish clothes. (Early Technicolor was sometimes shone off in such sequences.) Top designers like Erté were recruited to bring their talents to such films.

Fashion as a selling point in films remains with us. The glossy new version of The Hollywood Reporter, recently decried by David, now has a regular “Hollywood Style” section. The November 24 issue ran “Costumes of The King’s Speech,” and the December 1 issue describes “Fashions of The Tourist,” with photos of Angelina Jolie in her various costumes. In addition to shots of the stars, both articles feature enticing close-ups of lipstick, shoes, jewelry,and purses.

A double feature of Why Change Your Wife? and Erotikon would provide a vivid sense of the differing moral outlooks of mainstream America and Europe in the post-war years. In Erotikon, the situation is reversed. An absent-minded entomologist neglects  his sexy wife, who is having an affair with a nobleman. She is in love, however, with a sculptor, who is having an affair with his model. The sculptor returns her love, but eventually becomes jealous, not of her husband, who is his best friend, but of her lover. When the husband finds out that his wife has been unfaithful, he is mildly upset, but he settles down happily with his cheerful young niece, who pampers his taste for plain cooking and an undemanding home life. About the only thing these two films have in common is that they view divorce, which was still quite a controversial issue in the 1920s, as sometimes benefiting the people involved. Adultery actually occurs rather than being hinted at but avoided, though faithful monogamy is ultimately put forth as the ideal.

his sexy wife, who is having an affair with a nobleman. She is in love, however, with a sculptor, who is having an affair with his model. The sculptor returns her love, but eventually becomes jealous, not of her husband, who is his best friend, but of her lover. When the husband finds out that his wife has been unfaithful, he is mildly upset, but he settles down happily with his cheerful young niece, who pampers his taste for plain cooking and an undemanding home life. About the only thing these two films have in common is that they view divorce, which was still quite a controversial issue in the 1920s, as sometimes benefiting the people involved. Adultery actually occurs rather than being hinted at but avoided, though faithful monogamy is ultimately put forth as the ideal.

Erotikon reflects some of the influences from Hollywood that were seeping into European films after the war. Sets are larger, cuts more frequent (though not always respecting the axis of action), and three-point lighting crops up occasionally. Yet Stiller maintains the strengths of the Scandinavian cinema of the 1910s, with skillful depth staging (left) and a dramatic use of a mirror. In the opening of a crucial scene where the sculptor confronts the wife with her adultery, tension builds because she does not know he is watching her until she sees him in the mirror (see bottom). Still, apart from its European sophistication, Erotikon could pass for an American film of the same era. Stiller and lead actor Lars Hansen would both be working in Hollywood by the mid-1920s.

I can’t allow the nearly unknown director William C. de Mille to take up two slots this year, though it’s tempting. William’s career was shorter than that of his much better-known brother Cecil. It peaked in 1920 and 1921, though, and I still look back fondly on the films by him that were shown in “La Giornate del Cinema Muto” festival of 1991. That year saw a large retrospective of Cecil’s films, and the organizers wisely decided to include a  sampling of William’s surviving work.

sampling of William’s surviving work.

The two men’s approaches were markedly different. Where Cecil by this point was setting his films among the rich and using visual means like costumes to make the action crystal-clear to the audience, William was more likely to favor middle-class settings with small dramas laced with humor and presented with restrained acting and small props. Despite William’s skill as a director and his ability to create sympathy for his characters, he never gained much prominence, especially compared to his brother. He retired from filmmaking in 1932, at the relatively young age of 54. Yet obviously he was attuned to his brother’s style, having written the script for Why Change Your Wife? It may be characteristic of the two that Cecil capitalized the De in De Mille, while William didn’t.

Relatively few of William’s films survive, but these include two excellent films from 1920, Jack Straw and Conrad in Quest of His Youth. I don’t remember Jack Straw well enough to describe it. It involved the hero’s falling in love with a woman when they both live in the same Harlem apartment building. When her family becomes rich, Straw disguises himself as the Archduke of Pomerania in order to woo her. Sort of a Ruritanian romance but played out in the U.S.

I remember Conrad in Quest of His Youth better. The hero returns from serving as a soldier in India. He feels old and decides to try and recover his youth. The first attempt comes when he and three cousins agree to return to their childhood home and indulge themselves in the simple pleasures of their youth. Eating porridge for breakfast is a treasured memory, but the group discovers that this and other delights are no longer enjoyable to them as adults. Conrad goes on to seek romance elsewhere and eventually finds a woman who makes him feel young again. The film’s poignant early section manages in a way that I’ve never see in any other film to convey both nostalgia for the joys of childhood and the sad impossibility of recapturing them.

Neither film is available on DVD. Indeed, I couldn’t find an image from either to use as an illustration. The only picture I located is a rather uninformative one from Conrad in Quest of His Youth, above right, which I scanned from William C.’s autobiography (Hollywood Saga, 1939). It’s no doubt an indicator of William’s modesty that the frontispiece of this book is a picture of his brother directing a film.

Maybe this entry will serve as a hint to one of the DVD companies specializing in silent movies that these two titles deserve to be made available. They’re high on my list of films I would love to see again.

Most people who study film history see Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari very early on, though they probably push it to the backs of their minds later on. I have a special fondness for Caligari precisely because I did see it early on. I took my first film course, a survey history of cinema, during my junior year. Maybe I would have gotten hooked and gone on to graduate school in cinema studies anyway, but it was Caligari that initially fascinated me. It was simply so different from any other films I had seen in what I suddenly realized was my limited movie-going experience. It inspired me to go to the library to look up more about it, a tiny exercise in film research.

Some may condemn it as stage-bound or static. Despite its painted canvas sets and heavy makeup, however, it’s not really like a stage play. Many of the sets are conceived of as representing deep space, though often only with a false perspective achieved by those painted sets:

Still, in an era when experimental cinema was largely unknown, Caligari was a bold attempt to bring a modernist movement from the other arts, Expressionism, into the cinema. It succeeded, too, and inaugurated a stylistic movement that we still study today.

I haven’t watched Caligari in years (I think I know it by heart), but I’m still fond of it. The plot is clever grand guignol. It has three of the great actors of the Expressionist cinema, Werner Krauss, Conrad Veidt, and Lil Dagover, demonstrating just what this new performance style should look like. The frame story retains the ability to start arguments. The set designs area dramatically original, and muted versions of them have shown up in the occasional film ever since 1920. Even if you don’t like it, Caligari can lay claim to being the most stylistically innovative film of its year.