Archive for the 'Directors: Kiarostami' Category

A last celluloid banquet from Vancouver

Detail from “Crimson Autumn” (1931) by Ural Tansykbaev (from The Desert of Forbidden Art)

Kristin here:

A Film Unfinished (Israel; dir. Yael Hersonski, 2010)

A Film Unfinished satisfies on many levels. It is based on several reels of an unfinished Nazi propaganda film labeled “The Ghetto,” discovered among an archive of thousands of cans of Nazi footage. On a simple documentary level, the scenes in the film show precious evidence of life in the Warsaw ghetto in the 1941-42 era, before most of its inhabitants were sent to death camps. As a piece of historical research on the part of the filmmakers, who found written and taped material that shed considerable light on this mysterious footage, it  comes across as a tightly constructed detective story. For theorists of documentary who want to stress that no non-fiction films can reveal life as it is, without manipulation, A Film Unfinished provides a dramatic example.

comes across as a tightly constructed detective story. For theorists of documentary who want to stress that no non-fiction films can reveal life as it is, without manipulation, A Film Unfinished provides a dramatic example.

The samples from the silent footage shown early in A Film Unfinished show a strange combination of subject matter. Apparently candid footage of people in the street, going about their daily lives, is mixed in with scenes of well-dressed men and women in restaurants or elegant apartments. How do these incongruous scenes fit together?

The filmmakers found extensive diaries kept by one of the officials in charge of the Ghetto, as well as taped testimony given in 1961 by one of the main cameramen who recorded the footage. Passages from these, read over additional footage from the film,gradually reveal at least part of the purpose behind the footage. The Nazis apparently wanted to show that some inhabitants of the ghetto were living a normal, even luxurious life (above left). But other scenes were shot showing these same people on sidewalks. Beggars pass by them, but the actors playing the well-off Jews were instructed to ignore them. The result would  presumably have been a display of Jews not only living well but also indifferent to the fates of their less fortunate neighbors.

presumably have been a display of Jews not only living well but also indifferent to the fates of their less fortunate neighbors.

The filmmaking process frequently intrudes. Apart from the voiceover readings from witnesses to the filming, there are occasional glimpses of cameramen in the backgrounds of scenes (left). Moreover, one reel of the rediscovered film turned out to be unedited takes of several brief sequences, showing retakes of the same footage. Thus an apparently candid shot of two little boys looking into a shop window abundantly stocked with food turns out to have been staged; we even get a glimpse of one of the filmmakers leaning into the shot to direct the boys. A scene of police clearing a crowded street was done by assembling a large group of Jews and then having the police drive people away (the scene at left being part of that action). Urgency was added when the filmmakers fired shots into the air to frighten the crowd.

An added layer was given to A Film Unfinished by assembling a small group of men and women from the ghetto who witnessed many of the events. They are seen watching the film and adding comments. One remembers having seen the filming. Another worries that she will see someone she once knew among the faces on the screen. The presence of these witnesses emphasizes the fact that what we are watching in the rediscovered footage is both an elaborately staged series of events and a grim record of reality in the ghetto. A particularly grim sequence shows men with a handcart gathering corpses from the sidewalks (where helpless relatives, without any other recourse, dumped them overnight). These are taken to a mass grave, where they are stacked like firewood, covered with sheets of paper, and buried. Though the men working at this grisly task were clearly told what to do by the filmmakers, the fact remains that this gathering and disposing of bodies was a routine that went on daily in the late days of the ghetto.

A Film Unfinished would be very useful in a class on documentary cinema.

The Desert of Forbidden Art (Russian/USA/Uzbekistan; dir. Tchavdar Gorgiev and Amanda Pope, 2010)

Our interest in 1920s and 1930s Soviet avant-garde art led David and me to this film. It reveals the remarkable, unknown work of Igor Savitsky, a Russian Russian archaeologist who discovered the culture and art of the Karakalpakstan region of Uzbekistan. Applying for government funds to create the Karakalpak Museum of Arts, Savitsky initially stocked it with the jewelry, costumes, pottery, and other local cultural artifacts that were discouraged by the Soviet modernization policy.

He also discovered that there were many hidden paintings and drawings by artists whose avant-garde tendencies had gotten them into trouble with the central Soviet government in the Stalinist era. In 1966 he secretly–and very illegally–began using government money to buy up whole caches of these works. By the time of his death in 1984, he had acquired around 44,000 of them! Many are still in storage, awaiting restoration, but the galleries of this remote museum are full of extraordinary, hitherto unknown artworks.

The Desert of Forbidden Art is informative not only about the history of Savitsky and the museum, but it reveals something of the current culture of this isolated province, a culture which figures prominently in the artworks as well. Sons and daughters of the artists appear on camera, as does Marinika Babanarzorova, the museum’s current director. Naturally many beautiful artworks are on display as well.

The film touches only briefly on the fact that these artworks have been hidden away in a remote desert area which is also increasingly under the sway of Islamic extremism. A few documentary shots show the dynamiting of ancient rock-cut Buddha statues in adjacent Afghanistan in 2001. The head of the Nukus Museum was invited to appear with the film at the VIFF, but she was unable to get permission to leave the country. One is left wondering whether these artworks will need to be rescued anew.

The film is screening widely at film festivals and societies, mostly in the USA but in a few other countries as well. See its website for a schedule of upcoming showings. It also will be run in April or May, 2011 in the PBS series “Independent Lens.”

Certified Copy (France/Italy/Belgium; dir. Abbas Kiarostami, 2010)

This was the film I was most looking forward to at the festival, and it was the last–and best–one I saw. As usual, Kiarostami has come up with a novel approach to storytelling. (See David’s entry on Shirin.) After only one viewing, I’m not confident enough to say much about Certified Copy. Besides, almost anything I say about the plot will give away too much. This is a puzzle film that unfolds very slowly and very subtly.

It seems to work in ways almost opposite to those of the big puzzle film of the year, Inception. That film was almost all exposition, which we had to frantically note and try to piece together to get even a rough grasp of the plot. Certified Copy has almost no exposition–or none that we can recognize immediately or even trust when we do recognize it. I could gauge how slowly that recognition comes by the fact that the laughter at apparently incongruous behavior between the characters gradually faded. Different members of the audience realized at different moments that what had seemed incongruous maybe wasn’t after all, though it’s possible that the incongruity was just increasing right up to the end. Close to the end, only a lady two rows behind me was still laughing.

Essentially what happens is that a plot unfolds, and despite a lack of solid information, most of us probably infer from the conversations enough to assume we understand the two main characters and their relationship. Eventually their actions suggest that perhaps an entirely different plot and relationship has been unfolding all along. (This comes fairly late in the film, in maybe the last third or even quarter.) Perhaps the information we receive does not allow us to decide in this ambiguous situation, though I think people do tend to decide. I decided one way, David decided the other.

Interestingly, this mirrors in longer form the last sequence of Under the Olive Trees. There we are not told what the girl replies when the boy runs after her and proposes marriage one last time. In that case, too, I decided one way, David the other. Years ago we told Kiarostami this, and he laughed and said men tend to assume the girl accepts him, while women assume she rejected him. (I think there actually are some fairly clear clues earlier in the film that she will reject him, but explaining those would be a different entry.) That may be the case here, that men and women will reach opposite conclusions.

On the other hand, and this would require at least a second viewing, the film may remain utterly ambiguous about which plot is “real.” Or it may even stray into the territory of the inexplicable, à la Buñuel or David Lynch, where the difference parts of the story are each “true” but incompatible. M. Tsai suggests, “‘Certified Copy’ plays out a bit like a romantic comedy directed by David Lynch with its distinct two-halves connected by a thread.” (Not to be read until you’ve seen the film.)

Apart from its teasing, baffling, shifting elements, Certified Copy contains two fine lead performances and, of course, some beautiful cinematography. There’s a bit of a surprise, in that Kiarostami for the most part avoids his characteristic sweeping views of landscapes. Tuscan hilltop towns would seem to be perfect for his typical shots of vehicles struggling up bending roads, but we are largely confined inside the car during the driving scene, watching the characters and not the glimpses of trees through the windows. Those yearning to see Italy must be content with stone or painted stucco walls (as at the left).

Apart from its teasing, baffling, shifting elements, Certified Copy contains two fine lead performances and, of course, some beautiful cinematography. There’s a bit of a surprise, in that Kiarostami for the most part avoids his characteristic sweeping views of landscapes. Tuscan hilltop towns would seem to be perfect for his typical shots of vehicles struggling up bending roads, but we are largely confined inside the car during the driving scene, watching the characters and not the glimpses of trees through the windows. Those yearning to see Italy must be content with stone or painted stucco walls (as at the left).

For many links to articles and reviews, see David Hudson’s helpful wrap-up on Mubi. (Again, not until you’ve seen the film.)

Sodankylä Forever (Finland; dir. Peter von Bagh, 2010)

DB here:

Do writers write books about fanatical readers? Do composers write operas about opera lovers? Sometimes, but not to the degree that cinephiles delight in making films about their passion. Case in point: Peter von Bagh’s Sodankylä Forever. The Festival screened two films devoted to Finland’s Midnight Film Festival, which not only runs movies around the clock but hosts marathon interviews with filmmakers.

It isn’t your usual red-carpet event. The town is tiny. Guests are treated to campfire cookouts and invited to play soccer. But watching old clips, catching snatches of the Johnny Guitar theme, and hearing revered directors spin their yarns is enough to bring pleasure. There are moments of drama—Zanussi and Makavejev boycott a screening of Potemkin because of its “totalitarian” ideology—but mostly the filmmakers muse in a relaxed fashion about the good, and bad, old days.

The Yearning for the First Cinema Experience treats a core cinephile topic: What was your earliest encounter with the movies? Disney films, as you might expect, play a major role, but so too does Frankenstein (which made Victor Erice realize that people kill other people) and even the MGM lion (which startled Kiarostami in his childhood). The First Experience includes more mature epiphanies, such as Bob Rafelson’s obsessive visits to Manhattan’s Thalia. If the official classics get particular attention, it’s perhaps because, as Costa-Gavras says, “Everything was done in the silent cinema.”

So cinephiles are nostalgists, sentimentalists, even narcissists. But we aren’t oblivious to history behind the screen. The Century of Cinema episode focuses on directors’ relation to World War II (a continuing fascination of von Bagh’s). An era of purges, battlefront savagery, and prison camps, created, Szabo reflects, “a generation without fathers.” Jancsó, who served time in a Finnish POW camp, pays tribute to his hosts with a recitation, in Hungarian, of the opening of the Kalevala.

After the war, however, several Western European directors recall the advent of a new era of intelligence and creative engagement. The spirit was most apparent in the Italian Neorealist films. Erice tells of sneaking a forbidden print of Rome, Open City out of customs so that Spanish cinephiles could see it. In Eastern Europe, of course, things were different, and tales of censorship and young directors’ struggle to innovate are treated as continuations of wartime crises and constraints. Alexei German sums up the status of the artist who refuses to affirm official culture: “We are not the doctors, we are the pain.” Samuel Fuller, who has already explained that being assigned to a rear-guard unit in a retreat is a death warrant, is given the epilogue. He recalls visiting the tidiest graveyard he has ever seen and turning to watch the wind rustling the grass. Was he imagining how the scene would look on film? Naturally, arch-cinephile von Bagh shows us.

DB, Abbas Kiarostami, KT. Chicago, March 1998.

Now leaving from platform 1

From a Facebook post by Tahereh

To all my friends:

What can I reply to Hossein? He’s pursuing me so avidly, but you know he isnt really a prime catch. No education, no house. If it werent for the earthquake, I wouldnt give him a second look. But he does interest me a little—he’s made me lose track of my lines so many times!

Oh no, now he’s chasing me across the field. What can I tell him? BRB!

DB here:

Many people in the film industry hold media studies in disdain, and often the feeling is mutual. Filmmakers recoil from the abstrusities of Big Theory, and academics often consider filmmakers gearheads (just before wagging their fingers and warning us about the Intentional Fallacy). But scholars like Rick Altman, John Caldwell, Janet Staiger, Kristin, and me, and younger folks like Patrick Keating and Ben Wright have been trying to study filmmakers’ creative choices in concrete ways. Some of us even ask filmmakers what they were trying to do.

So it’s heartening to see movement in the other direction. For quite a while academically trained filmmakers like James Schamus and Todd Haynes have brought ideas from their university studies into their films. Recently Reid Rosefelt composed an enlightening blog entry on Kathryn Bigelow’s intellectual side. Now some terms and ideas are being spread even more widely across the industry.

For example, in a recent Entertainment Weekly story about why women viewers like horror, we read:

One of the most consistent tropes of the genre is the character whom filmmakers call ”the final girl” — the survivor.

Actually, it was Carol Clover, scholar of horror movies and Scandinavian epics, who came up with the “final girl” nickname in her book Men, Women, and Chainsaws. Going back to the EW sentence, you notice that academics helped popularize the term genre too, which you seldom find in Hollywood’s patter before the 1970s. And the very word trope smells of classrooms and chalkdust.

Even more striking is a recent Variety article entitled, “Transmedia Storytelling Is Future of Biz.” Peter Caranicas explains that it involves “developing a piece of intellectual property across multiple media platforms.” The Star Wars franchise is the major modern instance, as Caranicas explains.

What Lucas did went several steps beyond old-style character licensing and brand extensions. He created a unified body of work with an extensive backstory and mythology, and he determinedly guarded its canon [another academic term—DB] while simultaneously opening up peripheral parts of his universe to exploration by other contributors.

One of my former students assures me that Kristin and I used the term “transmedia” back in the 1990s, but we have no memory of doing so. More relevantly, Liz Rosenthal reminds us that Peter Greenaway was pushing the concept in 1993. “If the cinema intends to survive, it has to make a pact and a relationship with concepts of interactivity and it has to see itself as only part of a multimedia cultural adventure.”

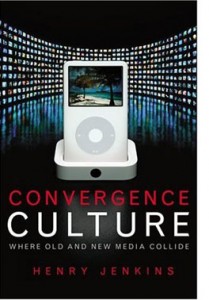

In any case, the person who brought the concept of transmedia storytelling to the forefront of media studies, and thus industry parlance, was another Wisconsin student, Henry Jenkins. Henry has made the concept part of his broader research into how modern media connect with audiences, particularly fan audiences. In his 1992 essay on Twin Peaks, he was already exploring how fans used the still-emerging internet to respond to a range of ancillary texts around Lynch’s TV series. You can get a quick acquaintance with his most recent ideas in this 2007 blog essay. For me, his argument emerged most vividly in a talk he gave at Madison some years ago. The lecture became the chapter “Searching for the Origami Unicorn” in his book Convergence Culture. For his more recent thinking, you can check his current course syllabus, which includes reading and web references, in the 11 August entry here.

The platform-shifting that Caranicas describes is planned and executed at the creative end, moving the story world calculatedly across media. These, dubbed by Jenkins “commercial extensions,” differ from “grassroots extensions,” which are created by audience members without the permission, or even the knowledge, of the creators. The commercial extensions are what I’ll be considering here.

From aggregator Movie MMORPG:

Welcome to a sophisticated world teetering on the edge of decadence. Get hammered on Italian cocktails. Fight your way out of a hospital jammed with nymphos. Cheat on your wife. Seduce a married man. Wander through the streets and stare at gushing water. Have you got what it takes to survive a day in LaNotteCity? You’ll get hooked, since the endgame is always inconclusive!

As it’s currently discussed, transmedia storytelling has two uncontroversial components and one rare but intriguing one.

First, the term implies that a story is spread among a series of discrete “texts.” This “hypernarrative” idea was explored with taxonomic zeal by Gérard Genette in his 1982 book Palimpsests. His taxonomy of storytelling is worth considering a little here because he anticipated several possibilities we’re seeing now. Many of his categories have parallels in cinema, but I’ll stick to his domain, literature.

First, the term implies that a story is spread among a series of discrete “texts.” This “hypernarrative” idea was explored with taxonomic zeal by Gérard Genette in his 1982 book Palimpsests. His taxonomy of storytelling is worth considering a little here because he anticipated several possibilities we’re seeing now. Many of his categories have parallels in cinema, but I’ll stick to his domain, literature.

Novels and short stories feed off other novels and short stories. Obvious examples are parodies, pastiches, sequels, and continuations (sequels not written by the original author). Genette also considers what he calls the “transposition,” a very roomy category that’s of particular interest to us.

Transpositions are things like translations, rewritings, and literary adaptations, as when a novel becomes a play. A transposition also occurs when the original text is pruned or compressed, as in abridged versions of Don Quixote or Moby-Dick. At the other quantitative extreme is what Genette calls augmentation. Here, the derivative work expands the original, either in style (three sentences replace one) or narrative material (extra scenes or plots).

Yet another sort of transposition occurs when the story events in the original are rendered through alternative literary techniques. Charles Lamb retells Ulysses’ adventures in a different order than Homer does, and someone could rewrite the events of Madame Bovary in first person, from Charles’ point of view. When Genette was writing, he had to reach for some esoteric examples, but nowadays we have others. Alice Randall’s The Wind Done Gone (2001) retells Gone with the Wind from the point of view of a slave on Tara. The novel Wicked is a large-scale example, as is Tom Stoppard’s Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead.

All these examples of hypernarrative operate within a single medium. The second condition of transmedia storytelling is, of course, that it crosses media. Genette considers drama and written literature to be all part of the same medium, but if you don’t, then novels turned into plays, like Les Miserables, would count as transfers across media.

In this sense, transmedia storytelling is very, very old. The Bible, the Homeric epics, the Bhagvad-gita, and many other classic stories have been rendered in plays and the visual arts across centuries. There are paintings portraying episodes in mythology and Shakespeare plays. More recently, film, radio, and television have created their own versions of literary or dramatic or operatic works. The whole area of what we now call adaptation is a matter of stories passed among media.

What makes this traditional idea sexy? I think it’s a third, less common component that Henry has spotlighted. Some transmedia narratives create a more complex overall experience than that provided by any text alone. This can be accomplished by spreading characters and plot twists among the different texts. If you haven’t tracked the story world on different platforms, you have an imperfect grasp of it.

I can follow Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories well without seeing The Seven Percent Solution or The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. These pastiches/continuations are clearly side excursions, enjoyable or not in themselves and perhaps illuminating some aspects of the original tales. But according to Henry, we can’t appreciate the Matrix trilogy unless we understand that key story events have taken place in the videogame, the comic books, and the short films gathered in The Animatrix. The Kid in The Matrix Reloaded makes cryptic reference to finding Neo by fate, but only those who have watched the short devoted to him knows what that means. If Sherlock pastiches are parasites, the texts around The Matrix exist in symbiosis, giving as much as they take.

This strategy differentiates the new transmedia storytelling from your typical franchise. In most film franchises, the same characters play out their fixed roles in different movies, or comic books, or TV shows. You need not consume all to understand one. But Henry envisages the possibility of creating a whole that is greater than its parts, a vast narrative experience that doesn’t end when the book’s last page is turned or the theatre lights come up. His idea seems to be echoed in Will Wright’s suggestion:

It’s a fractal deployment of intellectual property. Instead of picking one format, you’re designing for one mega-platform. . . . We’ve been talking about this kind of synergy for years, but it’s finally happening.

Stimulating as this prospect is, it remains rare. The Matrix is perhaps the best example, but Henry suggests that it’s also an extreme instance: “For the casual consumer, The Matrix asked too much. For the hard-core fan, it provided too little” (p. 126). More common is a Genette-style transposition, in which the core text—usually the movie—is given offshoots and roundabouts that lead back to it. As I understand it, the Star Wars novels operate under the injunction that although they can take a story situation as the basis for a new plot, in the end that plot has to leave the films’ story arc unchanged. Similarly, websites with puzzles, games, clues, and other supplementary material tend to be subordinate to the film, planting hints and foreshadowings (The Blair Witch Project, Memento). Alternatively, the A. I. website provided a largely independent story world that impinged on the movie’s action only slightly.

The “immersive” ancillaries seem on the whole designed less to complete or complicate the film than to cement loyalty to the property, and even recruit fans to participate in marketing. It’s enhanced synergy, upgraded brand loyalty.

For the most part Hollywood is thinking pragmatically, adopting Lucas’ strategy of spinning off ancillaries in ways that respect the hardcore fans’ appreciation of the esoterica in the property. Caranicas quotes Jeff Gomez, an entrepreneur in transmedia storytelling, saying that for most of his clients “we make sure the universe of the film maintains its integrity as it’s expanded and implemented across multiple platforms.” It would seem to be a strategy of expanding and enriching fan following, and consequent purchases.

As best I can tell, then, in borrowing this academic idea, the industry is taking the radical edge off. But is that surprising?

Excerpt from www.ballsup.net

What a bloody week. Just now had a chance to update things. Fact is, it’s me last post. Luckily I let that cellphone drop and grabbed the satchel just before it fell into the Thames. Me and the crew are now packing for Bimini, ready for living large but in a rush becuz Big Chris may be looking for us. Hang on, must upload now, someone’s knocking at me d

Henry’s chapter in Convergence Culture grants that “relatively few, if any, franchises achieve the full aesthetic potential of transmedia storytelling—yet” (p. 97). Perhaps that hopeful “yet” will be fulfilled outside Hollywood? In the realm of the avant-garde, Matthew Barney has elaborated his own private mythology, dispersed among artifacts and hard-to-see films. In this he followed Joseph Beuys and Salvador Dalí. But you could argue that these artists really weren’t telling an overarching story. They were creating secular cults, full of arcana that only the pious initiates of Gallery Culture could grasp.

What about something more accessible? This month in Filmmaker magazine, Lance Weiler has suggested that indie filmmakers embrace the concept of transmedia storytelling (though he doesn’t use the term). Weiler argues that the explosion of digital technology has so transformed narrative that the filmmaker has to keep up. Instead of creating a script, with its genre formulas and three-act layout, the filmmaker should generate a bible, which plots an ensemble of characters and events that spills across film, websites, mobile communication, Twitter, gaming, and other platforms. The filmmaker designs “timelines, interaction trees, and flow charts” as well as “story bridges that provide seamless flow across devices and screens.”

Weiler doesn’t offer any specific examples apart from his Head Trauma, a horror feature accompanied by an alternate reality game that involved mobile and online access. You can watch his account of the “evolution of storytelling” here, where he and Ted Hope speculate about transmedia storytelling as offering economic help to filmmakers, reclaiming authorship from corporations, and promoting new relations with the audience.

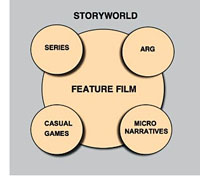

Hope and Weiler raise many fascinating questions about the prospects for multiplatform storytelling. At times, though, it seems that they accept the studio strategy of putting the film at the center of a multimedia ensemble. The diagram accompanying Weiler’s article illustrates that. It’s hard to think outside the franchise model, even if we want to denounce Hollywood for being stuck in an outdated commitment to the theatrical feature as foundational “content.”

Hope and Weiler raise many fascinating questions about the prospects for multiplatform storytelling. At times, though, it seems that they accept the studio strategy of putting the film at the center of a multimedia ensemble. The diagram accompanying Weiler’s article illustrates that. It’s hard to think outside the franchise model, even if we want to denounce Hollywood for being stuck in an outdated commitment to the theatrical feature as foundational “content.”

We should welcome experimentation, so I wish Hope, Weiler, and other creators well. But I think we ought to recognize some problems with expanding story worlds in these directions.

For one thing, most Hollywood and indie films aren’t particularly good. Perhaps it’s best to let most storyworlds molder away. Does every horror movie need a zigzag trail of web pages? Do you want a diary of Daredevil’s down time? Do you want to look at the Flickr page of the family in Little Miss Sunshine? Do you want to receive Tweets from Juno? Pursued to the max, transmedia storytelling could be as alternately dull and maddening as your own life.

Sure, somebody might go for it. Kristin points out, though, that people who would be motivated to follow up on all the transmedia bits of a spreadeagled narrative are people who would identify themselves as part of a fandom. There aren’t that many films/franchises that generate profoundly devoted fans on a large scale: The Matrix, Twilight, Harry Potter, The Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, Star Trek, maybe The Prisoner. These items are a tiny portion of the total number of films and TV series produced. It’s hard to imagine an ordinary feature, let alone an independent film, being able to motivate people to track down all these tributary narratives. There could be a lot of expensive flops if people tried to promote such things.

Consider a deeper point. Transmedia storytelling in the radical sense is posited as an active, participatory experience. Henry suggests that fans will race home from the multiplex to study up on iconography in The Matrix. Weiler’s article is accompanied by a hierarchy that lists “layers of interactivity.” The most superficial is “Passive Viewing,” defined as “Sit back and watch.” (Here Weiler parts company with Henry, who doesn’t consider ordinary viewing passive.) Further along are layers involving social networking, playing games, discussing or interacting with characters, finding hidden content, and even creating elements of the story world.

But it seems to me that film viewing is already an active, participatory experience. It requires attention, a degree of concentration, memory, anticipation, and a host of story-understanding skills. Even the simplest story gears up our minds. We may not notice this happening because our skills are so well-practiced; but skills they are. More complicated stories demand that we play a sort of mental game with the film. Trying to guess Hitchcock or Buñuel’s next twist can engross you deeply. And the very genre of puzzle films trades on brain strain, demanding that the film be watched many times (buy the DVD) for its narrational stratagems to be exposed. Films are interactive in the way a board game is: each move blocks certain possibilities, another anticipates what you’re going to do (mentally).

Moreover, how the ancillary texts add to the film is a crucial matter. No narrative is absolutely complete; the whole of any tale is never told. At the least, some intervals of time go missing, characters drift in and out of our ken, and things happen offscreen. Henry Jenkins suggests that gaps in the core text can be filled by the ancillary texts generated by fan fiction or the creators. But many films thrive by virtue of their gaps. In Psycho, just when did Marion decide to steal the bank’s money? There are the open endings, which leave the story action suspended. There are the uncertainties about motivation. In Anatomy of a Murder, did Lieutenant Manion kill his wife’s rapist in cold blood? Likewise, being locked to a certain character’s range of knowledge is the source of powerful emotional effects. We want to make the discoveries along with the character, be he Philip Marlowe or Travis Bickle.

The human imagination abhors a vacuum, I suppose, but many art works exploit that impulse by letting us play with alternative hypotheses about causes and outcomes. We don’t need the creators to close those hypotheses down. Indeed, you can argue that one of the contributions of independent film has been the possibility of pushing the audience toward accepting plots that don’t fit clear-cut norms. That innovation shrinks if we can run home to get background material online. By following the franchise logic, indie films risk giving up mystery.

At this point someone usually says that interactive storytelling allows the filmmaker to surrender some control to the viewer, who is empowered to choose her own adventure. This notion is worth a long blog entry in itself, so I’ll simply assert without proof: Storytelling is crucially all about control. It sometimes obliges the viewer to take adventures she could not imagine. Storytelling is artistic tyranny, and not always benevolent.

Another drawback to shifting a story among platforms: art works gain strength by having firm boundaries. A movie’s opening deserves to be treated as a distinct portal, a privileged point of access, a punctual moment at which we can take a breath and plunge into the story world. Likewise, the closing ought to be palpable, even if it’s a diminuendo or an unresolved chord. The special thrill of beginning and ending can be vitiated if we come to see the first shots as just continuations of the webisode, and closing images as something to be stitched to more stuff unfolding online. There’s a reason that pictures have frames.

Another drawback to shifting a story among platforms: art works gain strength by having firm boundaries. A movie’s opening deserves to be treated as a distinct portal, a privileged point of access, a punctual moment at which we can take a breath and plunge into the story world. Likewise, the closing ought to be palpable, even if it’s a diminuendo or an unresolved chord. The special thrill of beginning and ending can be vitiated if we come to see the first shots as just continuations of the webisode, and closing images as something to be stitched to more stuff unfolding online. There’s a reason that pictures have frames.

In between opening and closing, the order in which we get story information is crucial to our experience of the story world. Suspense, curiosity, surprise, and concern for characters—all are created by the sequencing of story action programmed into the movie. It’s significant, I think, that proponents of hardcore multiplatform storytelling don’t tend to describe the ups and downs of that experience across the narrative. The meanderings of multimedia browsing can’t be described with the confidence we can ascribe to a film’s developing organization. Facing multiple points of access, no two consumers are likely to encounter story information in the same order. If I start a novel at chapter one, and you start it at chapter ten, we simply haven’t experienced the art work the same way. This isn’t to say, of course, that each of us has an identical experience of a movie. It’s just that our individual experiences of the film overlap to an extent that allows us to talk about the patterning of the story under our eyes.

In correspondence with me, Henry suggests that transmedia storytelling may work best with television because of the serialized format; different people hop aboard at different points. I’d add that television’s installment-based storytelling, operating in the lived time of the audience, allows time for viewers to explore or create media offshoots. The installment-based nature of serial TV poses intriguing aesthetic problems of continuity, coherence, and memory. (See Jason Mittell’s essay on this matter.) For films, however, which are typically designed to be consumed in one sitting, multiple points of entry will tend to make plot patterns less clearly profiled.

If transmedia storytelling is difficult to apprehend for the viewer, it also makes critical analysis and evaluation much more difficult. How might we analyze overarching patterns of multiplatform plotting in The Matrix? True, one can itemize the inputs and decipher the citations, but it’s very hard to show how they work together, how they unfold, what it all adds up to—except to note that different people will encounter information bits at different times and with different states of knowledge.

Gap-filling isn’t the only rationale for spreading the story across platforms, of course. Parallel worlds can be built, secondary characters can be promoted, the story can be presented through a minor character’s eyes. If these ancillary stories become not parasitic but symbiotic, we expect them to engage us on their own terms, and this requires creativity of an extraordinarily high order.

Henry Jenkins suggests that for big-budget projects, this means finding unusually gifted collaborators. In the indie sector, the obstacles are even more considerable. Whether the result is Wendy and Lucy or Goodbye Solo, creating a first-rate feature-length movie takes tremendous talent, sweat, and resourcefulness. It is immensely harder to create a story universe that sustains the same intensity and quality across platforms. True, you can sprinkle clues and cryptic references among websites and YouTube shorts. The formulas of genre (horror, mystery) help you generate shock effects and mystification in teaser trailers. Appeal to stock characterization helps you mount a “realistic” Second Life life. But building a vast, sturdy world teeming with distinctive characters, unpredictable plotting, and human resonance is an immense task.

We await our multimedia Balzac. In the meantime, maybe indie filmmakers should settle for trying to be Chekhov.

http://tinyurl.com/scarkiller

Debbie, sorry 2 hav left SOOOO suddenlike. am @ Gila flats = cactus + varmnts. LOL with Blankethead!!! :-/

Uncl Ethan

Thanks to Henry Jenkins for comments on this entry. He recommends that interested readers have a look at Geoffrey Long’s 2007 MA thesis on the Jim Henson company, available, along with many other MIT projects, here. Thanks also to Kristin and Jeff Smith for suggestions, and to Janet Staiger for correcting my memory and calling attention to Dennis Bound’s book on “transmedia poetics” as applied to Perry Mason.

PS 11 Sept: Henry Jenkins has responded to my entry, with the first of three installments starting here.

The movie looks back at us

DB, still at the Hong Kong International Film Festival:

Abbas Kiarostami has the widest octave range of any filmmaker I know.

His humane dramas of Iranian life, from The Traveller to The Wind Will Carry Us, have justly won acclaim on the arthouse circuit. He has written scripts as well, some—like the under-seen The Journey (1994)—that are as compelling as a psychological thriller. He can conjure suspense out of the simplest acts, such as whether an adult will rip up a child’s copybook (Where Is the Friend’s Home?) or whether a four-year-old boy locked in with his baby brother can figure out how to turn off a stove (The Key). Indeed, I think that one of the great accomplishments of much modern Iranian cinema, with Kiarostomi in the vanguard, has been to reintroduce classic dramatic suspense into arthouse moviemaking.

But at times Kiarostami has moved to an opposite pole, that of extreme minimalism and “dedramatization.” The drift toward a hard-edged structure was there in Ten (2002), which gave us one of his drive-through dramas—people conversing in the front seat of a car—but in severe permutational form (different drivers, different passengers). Rigor was pushed to an extreme in Five Dedicated to Ozu (2003): Five lengthy shots of water landscapes, each many minutes long, taken at different times of day. The biggest dramatic action was the ducks walking through the frame. With Kiarostami, it seems, we cinephiles can have it all—Hitchcock and James Benning in the same filmmaker.

Now Shirin (aka My Sweet Shirin, 2008) marks another highly original exploration. I don’t expect to see a better film for quite some time.

After a credit sequence presenting the classic tale Khosrow and Shirin in a swift series of drawings, the film severs sound from image. What we hear over the next 85 minutes is an enactment of the tale, with actors, music, and effects. But we don’t see it at all. What we see are about 200 shots of female viewers, usually in single close-ups, with occasionally some men visible behind or on the screen edge. The women are looking more or less straight at the camera, and we infer that they’re reacting to the drama as we hear it.

That’s it. The closest analogy is probably to the celebrated sequence in Vivre sa vie, in which the prostitute played by Anna Karina weeps while watching La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc. Come to think of it, the really close analogy is Dreyer’s film itself, which almost never presents Jeanne and her judges in the same shot, locking her into a suffocating zone of her own.

Of course things aren’t as simple as I’ve suggested. For one thing, what is the nature of this spectacle? Is it a play? The thunderous sound effects, sweeping score, and close miking of the actors don’t suggest a theatrical production. So is it a film? True, some light spatters on the edge of the women’s chadors, as if from a projector behind them, but no light seems to be reflected from the screen. In any case, what’s the source of the occasional dripping water we hear from the right sound channel? The tale is derealized but it remains as vivid on the soundtrack as the faces are on the image track. What the women watch is, it seems, a composite, neither theatrical nor cinematic—a heightened idea of an audiovisual spectacle.

Moreover, there are the faces. We see some more than once, but new ones are introduced throughout. Spatially, they float pretty free; only occasionally do we get a sense of where the women are sitting in relation to one another. All are stunningly beautiful, whether young or old. We get an encyclopedia of expressions—neutral, alert, concentrated, bemused, amused, pained, anxious. During a battle scene, faces turn away, eyes lower, and hands shift nervously. The best person to review this movie is probably Paul Ekman, world expert on the nuances of facial signaling.

The weeping starts, by my count, about thirty-eight minutes in, during a rain scene uniting the two lovers Shirin and Khosrow. Thereafter, tears run down cheeks, along jaws and mouths, down necks and nostrils. The film is an almost absurdly pure experiment in facial empathy. It arouses us us by our sense of the story unfolding elsewhere, somewhere behind us, enhanced by lyrical vocalise and brusque sound effects, but above all by these eloquent expressions. It’s a feast for our mirror neurons. If you’re interested in reaction shots, you have to recall Dreyer remarking that “The human face is a landscape that you can never tire of exploring.”

I once asked Kiarostami how he got the remarkable performances in shot/ reverse-shot that we see in films like Through the Olive Trees and The Taste of Cherry. He said that he simply filmed one actor saying all his lines and giving all his reactions, then filmed the other. Often the two actors were never present at the same time, especially when he shot the car sequences. This montage-based approach, creating a synthetic space simply by cutting, has been taken to an extreme in Shirin, where the soundtrack supplies the reverse shot we never see. We’re told that Kiarostami filmed his female actors here reacting to dots on a board above the camera! Indeed, Kiarostami claims he decided on the Shirin story after filming the faces. Despite that, Shirin becomes one of the great ensemble pieces of screen acting, although the actors almost never share a real time and space. (Take that, green-screen wizards!) Like Godard, Kiarostami has been busy reinventing the Kuleshov effect (perhaps by way of Bresson).

This catalogue of female reactions to a tale of spiritual love reminds us that for all the centrality of men to his cinema, Kiarostami has also portrayed Iranian women as decisive, if sometimes mysterious, individuals. Women stubbornly go their own way in Through the Olive Trees and Ten. The premises of Shirin were sketched in his short, “Where Is My Romeo?” in Chacun son cinema (2007), in which women watch a screening of Romeo and Juliet. But the sentiments of that episode are given a dose of stringency here, particularly in one line Shirin utters: “Damn this man’s game that they call love!”

One last note: Kiarostami built movie production into the plot of Through the Olive Trees. Now he has given us the first fiction film I know about the reception of a movie, or at least a heightened idea of a movie. What we see, in all these concerned, fascinated faces and hands that flutter to the face, is what we spectators look like—from the point of view of a film.

For more on the production background, see the lengthy interview with Kiarostami here.