Archive for the 'Directors: Koepp' Category

Lie to me: MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE

Mission: Impossible (1996).

DB here:

Filmmakers rightly consider themselves problem-solvers. They deal with budget limits, scheduling constraints, temperamental staff and casts, and balky equipment. Some problems come with financial demands; others are self-imposed, such as: “Tell a story confined to a single room.” The artistic problems often demand solutions that guide viewers toward clarity, comprehension, and emotional impact.

Suppose your story situation is this. Character A is telling a story, but it’s a lie. Character B realizes it’s a lie, but doesn’t signal that recognition. This is really two problems in one: How do you tell the audience A is lying? And how do you convey that B knows but doesn’t reveal that knowledge?

These are at the crux of in an intriguing sequence in Mission: Impossible. The solutions found by screenwriter David Koepp and director Brian DePalma show how even a straightforward “entertainment movie” can pose interesting questions about cinematic expression.

Spoilers ahead. But I bet you’ve seen this movie.

The problem(s)

The Impossible Mission team has been sent to Prague, purportedly to retrieve a digital disc listing all CIA agents in Europe. They don’t know that this assignment is a pretext for finding a mole, a rogue agent who is selling secrets to foreign interests. While infiltrating a state gala, most of the team is killed. Only Ethan Hunt, point man in the mission, and Claire Phelps, the wife of the team leader Jim Phelps, survive. The IMF chief Kittridge accuses Ethan of being the mole so Ethan, along with Claire, needs to flee. But out of devotion to duty he insists on finding the mole. He learns that the mole under the alias of Job has offered to sell the NOC list to Max, a dealer in covert information. The bulk of the plot revolves around Ethan’s efforts to induce Max to reveal Job, which Ethan can do only by offering Max the NOC list—while at the same time making sure that it doesn’t really fall into Max’s hands.

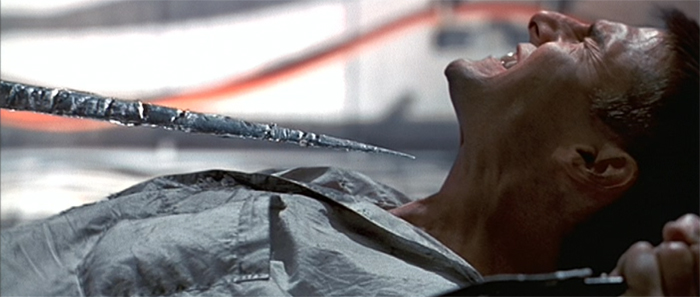

After a prologue, which I discussed in an earlier entry, the film’s first stretch revolves around the team’s invasion of the embassy party. As the scheme collapses, we see the deaths of the team members. Through cross-cutting and a moving-spotlight narration, the film shows us the technician Jack killed in an elevator shaft, Jim Phelps shot on a bridge and tumbling into the river, Sarah stabbed at a gate, and Hannah killed by a car bomb. The effects of these killings are registered largely through Ethan’s response. He hears Jack lose contact, watches video transmission of Jim’s bloody hands, finds Sarah impaled by a knife, and sees Hannah’s car explode. Later he, and we, will learn that Claire escaped.

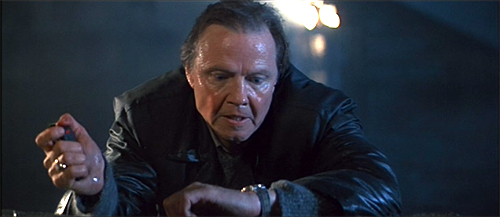

At the start of the film’s climax, Ethan discovers that Jim Phelps is still alive. In a café, Jim explains that he survived the shooting and that he saw the killer: Kittridge. Kittridge is the mole, he claims. Jack brings Jim into his plan to meet Max on the Eurostar train and apparently give her the NOC list he’s stolen from Langley.

The twist is that Jim–Ethan’s mentor, friend, and surrogate father–is lying. He is Job the mole, and he has eliminated his own team, faking the attack on himself. Thanks to crosscutting, the first version of the attacks concealed from us the actions Jim takes to kill his colleagues. The narrative problems are: How and when to tell us of Jim’s treachery? And how to represent Ethan’s state of awareness? Is he misled by Jim’s account, or does he doubt it? And what is Claire’s role in all this?

Three solutions

Singin’ in the Rain (1952).

Every creative choice eliminates alternatives, and I’ve compared classical filmmaking to selecting from a menu of more or less favored options. That menu can offer filmmakers ways of solving narrative problems. One choice for the M:I revelation is simply to present Jim telling Ethan his lies in the café. Ethan then can react in horror, leaving us to assume that he doesn’t doubt him.

This option was actually tried out in an early script draft. Jim explains and Ethan, despite some hesitation (“Hold on, it’s taking me a minute to adjust here“), seems to accept his story. Only in their final confrontation on the Eurostar does Ethan reveal that he had long before figured out that Jim had betrayed the team. We had no inkling that in the café Ethan was merely pretending to accept Jim’s account. His awareness of Jim’s scheme was held back as a surprise.

Another narrative option appears in a later script draft. This time Jim’s explanation is accompanied by flashbacks illustrating his lies. He claims to have swum to shore, patched up his gunshot wound, and followed Ethan’s trail. He then tells Ethan it was Kittridge who shot him and killed Sarah, and these moments are illustrated with quick flashback imagery. These are lying flashbacks. As a neat fillip, two of these shots replay Ethan finding Sarah’s body nearby, as if to certify Jim’s story. “Ethan just stares at Phelps, his eyes wide with surprise.” Again, we’re led to think that Ethan trusts Jim’s tale, making the train confrontation a revelation of Ethan’s outplaying Jim.

We should remember that the Hollywood menu provides the lying flashback as an option, albeit rare. In Singin’ in the Rain, for instance, Don Lockwood’s voice-over interview portrays his early career as one of refined show-business accomplishment. “Dignity—always dignity.” But the images undercut this by showing him performing slapstick routines in burlesque. Since this is a comedy, we can understand that the film’s flashbacks are debunking his pretension. As for the second problem, that of conveying a listener’s skepticism, the present-time scenes reinforce the impression of Don’s puffery by showing his pal Cosmo’s eye-rolling reaction. Still, the interviewer and presumably the radio audience are taken in.

This second M:I script variant doesn’t include such hints that Ethan doubts Jim, so the problem of the conveying the listener’s true reaction is bypassed. But the final film supplies yet another solution.

After I drafted what you’ve just read, I heard from screenwriter David Koepp. I had written him to ask about the alterations, and he talked with De Palma about them.

Brian reminded me that the intention of the scene was built around an idea — can we show Jim lying, and simultaneously see Ethan figuring out those lies in his own mind? Without telling Jim that he knows it’s a lie, Ethan is picturing for us what the truth must (or might) have been. It’s a cool idea, and, typical of DePalma, highly visual. Actually seeing on screen versions of events that may or MAY NOT have happened is something we started playing around with in M:I, and then did to a greater degree in Snake Eyes, which we wrote right after that.

Neither one of us can remember in useful detail about why we might have tried several other versions first, but my guess is that the one with Jim simply verbalizing the lie was jettisoned in favor of images for obvious (and again, DePalma-esque) reasons, i.e., it’s better to see something than to hear it. The flashback showing Kittridge as the perpetrator was likely because we wanted to keep going for as long as possible with the character I’ve come to call the Principled Antagonist — POSSIBLY a villain, turns out not to be, but always diametrically opposed to the hero and his goals.

It was good to have my hunch confirmed, and to watch filmmakers sampling the menu of options from draft to draft. The final shooting script presents the new variant. Ethan, not Jim, spells out the scheme in dialogue. This leads Jim to assume that Ethan accepts Kittridge as the culprit. But the image track shows Jim committing the crimes. As the script puts it:

A reprise of PHELPS’s narrative only now ETHAN’S telling it and camera is showing the events as ETHAN sees they actually happened.

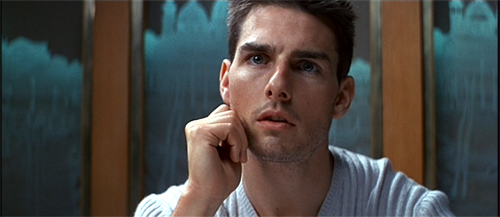

There’s still a potential obstacle, though. What if the viewer takes the flashbacks to show what really happened but doesn’t grasp that they’re Ethan’s imaginings? They might be only “the film telling us what really happened,” as in Singin’ in the Rain. How to establish that we’re following Ethan’s train of thought while he lies during his dialogue with Jim?

How to lie to a liar

Here’s the sequence as it appears in the film.

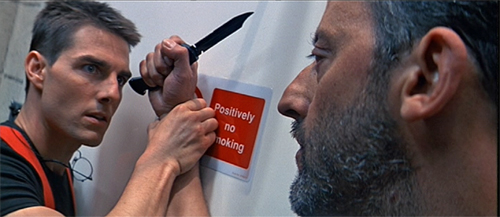

On the first problem, the sequence makes clear that Jim’s accusation of Kittridge is false. We’re introduced to Jim’s treachery with several shots showing Jim engineering Jack’s death in the elevator. Several more shots, stressed through slow-motion, illustrate how Jim faked his own death. And the knifing of Golitsyn and Sarah is attributed to Krieger. You can also argue that wily viewers will take Jim’s sidelong glance at Ethan as a tip-off to his treachery–a classic shot lingering on the Guilty One (as we’ve seen elsewhere).

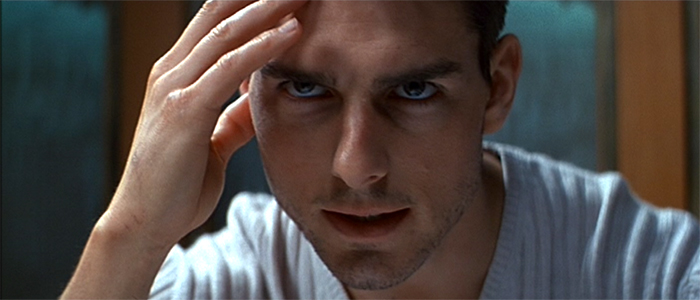

Still, how can we be sure that Ethan sees “events as they actually happened”–especially since his shock and puzzlement at hearing Jim’s tale seem so genuine?

The sequence solves the second problem with two passages that strongly imply that the flow of images reflects what’s in Ethan’s mind.

First, among phases of the stabbings at the gate, there’s the interpolated shot of Ethan pinning Krieger’s wrist to the wall during the Langley heist.

The two-shot of Ethan and Krieger, a flashback not part of Jim’s story, indicates Ethan’s realization that the knife he found in Sarah’s side was one of Krieger’s. Interestingly, this shot isn’t in the shooting script.

A stronger cue that we’re in Ethan’s mind comes with the “revised and corrected” version of Hannah’s death. Did “backup” take her out? The answer comes with a shot of Claire triggering the explosion and turning to look at the camera.

Claire’s look defies plausibility. It’s as if she is turning to glare, almost defiantly, at the Ethan who’s imagining this. Because he’s attracted to Claire, he wants to give her the benefit of the doubt. His imagination immediately proposes an alternative in which Jim sets off the bomb.

In the train at the climax, Jim will confirm Ethan’s hesitation: he was reluctant to suspect Claire. In the later stretch of the café scene, not included in my extract, the question of her loyalty is evoked as Jim urges Ethan to keep quiet about the scheme. When Ethan returns to Claire at the safe house, there remains the issue of whether her seduction of him is sincere or a further act of betrayal.

More immediately, the two problems are solved. Not only do we have the exposure of Jim’s lie, but we also get glimpses of how Ethan reconstructs what really happened. What makes this all particularly clever is that Ethan’s dialogue seems to confirm Jim’s tale. Ethan’s verbal duplicity is consistent with his talent for bluffing (as with Krieger and the fake NOC disc) and the earlier twinge of suspicion he had about Jim’s Palmer House Bible. When image and sound contradict one another here, we’re obliged to trust the image.

All of which charges Ethan’s final question–“Why, Jim? Why?”–with a double significance. Apparently asking about Kittridge’s motive, Ethan is pressing his mentor, almost desperately. Jim’s answer, about a refusal to accept the end of the Cold War, applies as much to him as to a CIA bureaucrat. We may not fully recognize it at the moment, but Ethan’s question marks the end of their friendship.

Someone might ask if every audience member will realize that the sequence solves both problems. Presumably even a ninny understands that Jim is lying; but maybe some viewers don’t get that Ethan is aware of the lie. My own inclination is to see the cues of Krieger’s knife and the revised version of Hannah’s death as pretty solid hints. Still, we might be in the realm, not unknown to Hollywood cinema, of a film that includes subtleties that not every viewer catches. I’m reminded of a screenwriter’s remark: “It’s not necessary that every viewer understand everything, only that everything can be understood.” This is presumably one reason we return to films and find more in them.

It’s also one reason it’s fun to analyze them.

Thanks to David Koepp and Brian De Palma for responding to my questions. David’s script archive is here.

The remark about understandable stories comes from Ted Elliott, as quoted in Jeff Goldsmith, “The Craft of Writing the Tentpole Movie,” Creative Screenwriting 11, no. 3 (May/ June 2004):, 53.

Mission: Impossible (1996).

KIMI: She’s here

Kimi (2022).

DB here:

Just when I worried that the solitary-woman-in-peril cycle had ended, along comes Steven Soderbergh’s Kimi on HBO Plus. Following on the fine No Sudden Move from last year, his latest effort shows how an imaginative script (from Friend of the Blog David Koepp), elegant direction, an unpredictable score, and an engagingly eccentric central performance (from Zoë Kravitz) can revivify some classic conventions.

Some critics think that when parodies show up, the genre is on the downturn. The streaming release of The Woman in the House Across the Street from the Girl in the Window (2022) might suggest that the cycle based on The Girl on the Train (2016) and The Woman in the Window (2021) had run its course. But actually, parodies can show up at any point in the life cycle of a genre. The Great K & A Train Robbery (1925) didn’t kill off the western, and Spaceballs (1987) didn’t wipe out space opera. So it’s good to know that the presence of Woman in the House Across the Street etc. doesn’t make a straightforward but sophisticated entry like Kimi any the less sparkling.

It depends on what I’ve called the Eyewitness Plot, and I’ve tried in Revisiting Hollywood to show how that emerged from the flurry of creative activity we find in 1940s studio cinema. Here the protagonist sees what may be a crime and asks the authorities to intervene. There’s enough uncertainty about the incident itself, and about the reliability of the witness, to make the police doubt that there’s been a crime. So the protagonist has to investigate–while becoming a target of violence in turn. Rear Window (1954) is the standard example, but it has many predecessors in fiction, film, and radio, notably The Window (1949). A variant relies not on sight but sound: the protagonist hears something of criminal consequence. That alternative is played out in Sorry, Wrong Number (1948) and, later, The Conversation (1974) and Blow-Out (1981).

Koepp and Soderbergh, both connoisseurs of classic Hollywood, understand the power of locking us into the perceptions of the witness while at the same time keeping us aware of the larger context of the action. Rear Window is exceptionally strict in limiting us to what Jeff sees and hears, but even then there is a telltale moment when we’re given information that would seem to contradict his belief that his neighbor has murdered his wife. More common is a balanced narrration that ties us to what the protagonist knows but occasionally strays away to supply backstory and ancillary information–usually, just enough to foster suspense.

That’s enough setup. Major spoilers follow! If you haven’t seen Kimi yet, visit and return.

She looks and listens

Angela Childs lives in lockdown. Not just the pandemic but a traumatic sexual assault has made her afraid to leave her Seattle loft, and more basically resistant to emotional contact. She works from home for Amygdala, a company promoting an Alexa/Siri gadget called Kimi. Unlike the competitors, which rely on machine learning, Amygdala has an army of monitors that track actual user dialogues with Kimi in order to correct its errors. Angela is a monitor, and on one recording she hears, muffled by music and noise, what seems to be a murder. After cleaning up a dense recording and inducing a more experienced hacker to find the user’s entire log of Kimi conversations, Angela discovers a crucial one that seems to lead up to the crime.

Here the official reluctance to believe the witness takes the form of an Amygdala executive’s demand to listen to the recording. When Angela insists that the FBI be present for the playback, the corporation takes steps to silence her. The second large section of the film consists of a prolonged chase and, back in her loft, a final confrontation with the men who committed the crime.

The film’s opening establishes, as a sort of intrinsic norm, the alternation between the wider view of the crime’s circumstances and Angela’s limited perspective. The first scene sets up Bradley Hasling awaiting Amygdala’s IPO, but worried because he’s paying off someone for suppressing information about an unnamed woman.

With our curiosity aroused, the plot can afford to introduce us to Angela and her routines in a more leisurely way. Without the Hasling scene, this stretch would be mostly character portrayal, but it gains keener interest as we must wonder how Angela’s fate will intersect with his. Glimpses of Angela fussily making her bed, brushing her teeth, and exercising on her bike also serve to illustrate how she activates Kimi for music and for computer access.

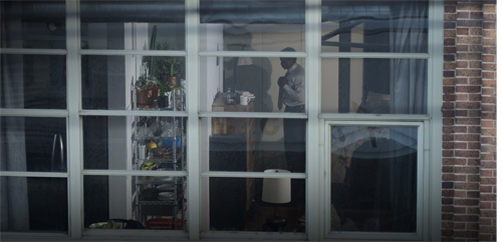

Just as important are the passages of optical POV that show her at her window scanning her street. She looks across at a family in the building opposite, and then looks up and to her left, where she sees the bearded man we’ll learn is called Kevin. He looks back at her.

She swivels her gaze to another window opposite and sees a closed curtain.

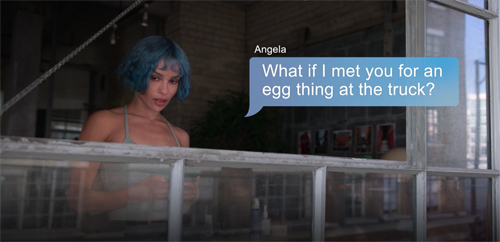

Later on the balcony she looks at the window and this time sees Terry, her casual lover, getting ready for work.

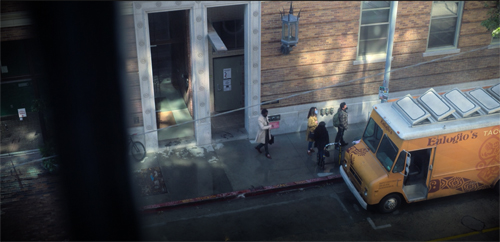

She texts him, and after an external, objective pan shot links the two buildings, she asks Terry if he wants to join her for a breakfast at the food truck down below.

However, she’s afraid to leave the apartment, and her fractured activity is rendered in discordant POV angles. After a shot of her in the shower, we see Terry at the truck, from her usual station point. There’s no lead-in shot of her looking; is she watching from offscreen after the shower, or has the narration worked behind her back, while reminding us of her usual position?

Finally, when she collapses on the floor, unable to leave, we get the same high angle on Terry at the truck, texting her and looking up.

Cut back to her still on the floor. The narration is now operating independent of her vision, but with traces of her viewpoint lingering.

The passage is capped by a shot of her at the window looking down, followed by an optical POV of the food truck, sans Terry.

Another shot of her seals the sequence, but when she pulls away from the window, we get an extra, new angle on her: from outside and above. It’s a fair approximation of what Kevin’s viewpoint on her might be. Yet there’s no shot showing him watching.

The “unclaimed” POV shots that close this scene acknowledge that however much we’re tied to the protagonist’s perceptions, the narration won’t limit us to them–that there is wiggle room to supply extra information, and to imply that our heroine is watched by others. This fluctuating access will become important in the crosscutting that provides the film’s climax.

She flees and fights

The fusion of external viewpoints and subjective ones continues in different ways later. When Angela plays the recordings of the attack, Soderbergh gives us her mental imagery–first as blurred cutaways, then as superimpositions. She’s imagining the assault. Later we’ll learn she has been a rape victim herself.

We’ll later discover that the faces of the murderers are those of the thugs who will pursue her. Yet she hasn’t seen them yet, so she can’t plausibly be visualizing them in the scene.

This is an innovation, I think. In the Forties and since, if these visualized images were to accompany the playback, the faces of the killers would have been indiscernible. Soderbergh is willing to violate plausibility in order to gain economy (introducing us to the thugs) and to continue his initial strategy of rendering subjective experience while also adding information for us.

A milder version of the tactic will be used in the climax, after Angela is captured and lying semi-unconscious in the van. We see her awake and apparently listening to the thugs’ dialogue, while superimpositions suggest the passage of the van through the neighborhood.

Incidentally, these are good examples of the persistence of “Impressionist” cinema techniques from the silent era. Soderbergh had made use of them in Unsane (2018), another film about a woman in peril.

Apart from the prologue showing Hasling’s phone call, the film’s first stretch is confined to Angela’s loft. It’s a classic “bottle” situation, a premise that Koepp is fond of. (Cf. his script for Panic Room, 2002.) It’s Angela’s sympathy for the victim of the crime that propels her out of her bubble into the wider world. Here Zoë Kravitz’s performance takes on a new dimension.

In her loft she’s clipped and brusque, dominating everyone she talks to. Her vulnerability, though, is suggested by her obsessive hand sanitizing. Emphasized by her waving her hands to dry them, it becomes practically a nervous tic.

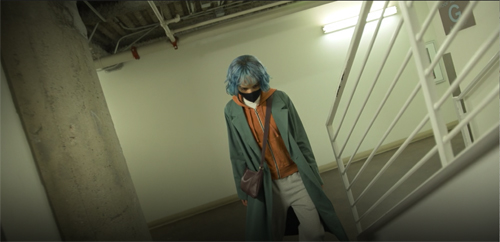

Once outside, she scoots along, arms jammed to her side, head buried in her hoodie, and body as stiff as Max Schreck’s. She tries to be as locked-in outdoors as she is indoors.

Soderberg compensates for her rigidity with camera technique that’s liberated from the confines of her loft. As Manohla Dargis points out in her review, now the film becomes a procession of canted angles and hurtling camera moves, swooping around her and trying to keep up.

Once back in the loft, however, the framing gets poised again and we’re subjected to a precise exercise in suspense. Close-ups and abrupt changes of angle provide exactly what we need to see at each instant.

And things planted quietly in the opening, particularly Angela’s knowledge of building construction, become crucial to her survival. Kimi proves to be a lifesaving sidekick, proving Hitchcock’s dictum concerning Jeff’s use of flashbulbs to save himself in Rear Window: you should use everything you’ve put into your scene.

One nice felicity: You might expect that Terry would turn out to be the “helper male” of so many women-in-peril plots (e.g., the Joseph Cotten character in Gaslight, 1944). Prototypically, this character rescues the protagonist and provides romantic interest for the future. Koepp’s screenplay shrewdly sets Terry up for this role when Angela looks outside during the gang’s siege and sees Terry’s apartment empty.

Later Terry is shown in a street-level, objective shot, walking to Angela’s building. This violation of the intrinsic POV norm suggests an impending rescue. But that prospect is canceled when he stops as if remembering something and turns back.

He does arrive, but too late to help. Terry’s expression as Angela calls 911 is a perfect capstone for the scene. The same wit flashes out of the epilogue, which suggests she’s broken out of her shell, but she still prudently uses sanitizer.

The domestic suspense thriller focused on a female protagonist remains a popular genre of novels. I devoted a chapter to it in my forthcoming book Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder. There haven’t been many film adaptations of them since The Woman in the Window, but maybe the neo-Gothic The Girl Before (2021) will unleash more. In the meantime, I’m glad that Koepp and Soderbergh have found ways to give the conventions brisk new life.

David Koepp remarks: “You’re right about the lingering effect of 40s cinema, as you and I have discussed many times. I’d say Sorry, Wrong Number was the direct antecedent here. . . I mean, the party line in Sorry, Wrong Number is basically the Alexa of its time, no?” Interesting in this connection is that the lengthy survey of Angela’s loft in the epilogue shows Kimi no longer there.

Another grace note: KT wondered if the precariously balanced kombucha bottle is psychologically revealing. It turns out to be the consummation of a moment from an earlier Koepp film.

The bottle on the edge of the counter — that was me making good on a setup I did in Secret Window, fifteen years ago. Seriously. There’s a shot in there where Johnny’s character, in a state of high anxiety and agitation, sets a glass down on his kitchen counter hastily, and doesn’t notice it’s only half on the counter. We did seventeen or twenty takes to get exactly the right gravity-defying balance on the edge. It was a pretty literal visual metaphor — you know, he’s on edge.

Thing was, in post-production I realized I had put in a perfect setup, but never paid it off. Why not have the glass fall and smash twenty minutes later, when we’re least expecting it?? Wished I had, never did.

So I used it again in Kimi, but with the (to my mind) required payoff, and at a moment of high tension. So, Angela, in her argument with Terry, is highly agitated, and smacks the bottle down on the counter carelessly, not realizing how close it is to the edge. (The KT hypothesis proves correct!) Angela forgets about it. So do we. Ten minutes later, when we’re all keyed up about something else, SMASH!

Thanks to David for corresponding.

The Hitchcock remark is this: “Here we have a photographer who uses his camera equipment to pry into the back yard, and when he defends himself he also uses his professional equipment, the flashbulbs. I make it a rule to exploit elements that are connected with a character or location. I would feel that I’d been remiss if I hadn’t made maximum use of those elements” (Truffaut/Hitchcock, rev. ed. 1983, 219).

Kimi (2022).

Another degree of Kevin Bacon: David Koepp’s YOU SHOULD HAVE LEFT

You Should Have Left (2020).

DB here:

Friend of The Blog David Koepp has written and directed a new movie that is premiering online this week. You Should Have Left is in the vein of his earlier, locked-in exercises in psychological horror, Stir of Echoes (1999) and Secret Window (2004). Both a haunted-house story and a disquieting probe into male anxiety, it’s another strong entry from Blumhouse–for me, the most interesting film company out there.

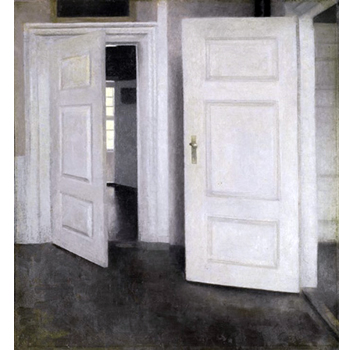

Critics sometimes say that Clint Eastwood is the last really “classical” director working now. Actually, in my view almost everybody remains a classical director to some extent. Still, the term holds especially good here. David’s handling of this scary chamber drama reminds me of the unfussy precision of Polanski in The Ghost Writer. In fact, one shot recalls the famous partial view of Ruth Gordon in Rosemary’s Baby. (Doorways are always good spots for tricky framing.)

More generally, David isn’t ashamed to invoke all the creepy conventions of the Old Dark House, suitably updated. He lays out the house’s space tidily and then disorients us about exactly where we just were. I think the Dreyer of Vampyr would appreciate the ways in which this PoMo mansion becomes a maze.

Of the other films David has directed, I’m especially fond of Ghost Town (2008) and Premium Rush (2012). And of course his scripts for Jurassic Park, War of the Worlds, and other megapix are models of construction. I also admire his superbly crafted screenplays for Panic Room (another claustrophobic exercise), for the still-too-little-appreciated The Paper, and for the bravura item that is Carlito’s Way.

You Should Have Left is currently available on demand from many cable and streaming services and will eventually show up as part of the offerings of NBC Universal/Peacock.

For more on David’s work, go here, which will lead you elsewhere.

You Should Have Left (2020).

Stuck inside these four walls: Chamber cinema for a plague year

The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972).

Privacy is the seat of Contemplation, though sometimes made the recluse of Tentation… Be you in your Chambers or priuate Closets; be you retired from the eyes of men; thinke how the eyes of God are on you. Doe not say, the walls encompasse mee, darknesse o’re-shadowes mee, the Curtaine of night secures me… doe nothing priuately, which you would not doe publickly. There is no retire from the eyes of God.

Richard Brathwaite, The English Gentlewoman (1631)

DB here:

We’re in the midst of a wondrous national experiment: What will Americans do without sports? Movies come to fill the void, and websites teem with recommendations for lockdown viewing. Among them are movies about pandemics, about personal relationships, and of course about all those vistas, urban or rural, that we can no longer visit in person. (“Craving Wide Open Spaces? Watch a Western.”)

Cinema loves to span spaces. Filmmakers have long celebrated the medium’s power to take us anywhere. So it’s natural, in a time of enforced hermitage, for people to long for Westerns, sword and sandal epics, and other genres that evoke grandeur.

But we’re now forced to pay more attention to more scaled-down surroundings. We’re scrutinizing our rooms and corridors and closets. We’re scrubbing the surfaces we bustle past every day. This new alertness to our immediate surroundings may sensitize us to a kind of cinema turned resolutely inward.

Long ago, when I was writing a book on Carl Dreyer, I was struck by a cross-media tradition that explored what you could express through purified interiors. I called it “chamber art.” In Western painting you can trace it back to Dutch genre works (supremely, Vermeer). It persisted through centuries, notably in Dreyer’s countryman Vilhelm Hammershøi (below).

Plays were often set in single rooms, of course, but the confinement was made especially salient by Strindberg, who even designed an intimate auditorium. For cinema, the major development was the Kammerspielfilm, as exemplified in Hintertreppe (1921), Scherben (1921), Sylvester (1924), and other silent German classics. Kristin and I talk about this trend here and here.

In the book I argued that Dreyer developed a “chamber cinema,” in piecemeal form, in his first features before eventually committing to it in Mikael (1924) and The Master of the House (1925). Two People (1945) is the purest case in the Dreyer oeuvre: A couple faces a crisis in their marriage over the course of a few hours in their apartment. (Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem available with English subtitles.) But you can see, thanks to Criterion, how spatial dynamics formed a powerful premise of his later masterpieces Vampyr (1932), Day of Wrath (1943), Ordet (1955), and Gertrud (1964).

Dreyer wasn’t alone. Ozu tried out the format in That Night’s Wife (1930), swaddling a husband, wife, child, and detective in a clutter of dripping laundry and American movie posters.

Bergman exploited the premise too, in films like Brink of Life (1958), Waiting Women (1952), his 1961-1963 trilogy, and Persona (1966). (All can be streamed on Criterion.)

Chamber cinema became an important, if rare expressive option for many filmmaking traditions. Writers and directors set themselves a crisp problem–how to tell a story under such constraints?

The challenge is finding “infinite riches in a little room.” How? Well, you can exploit the spatial restrictiveness by confining us to what the inhabitants of the space know. Limiting story information can build curiosity, suspense, and surprise. You can also create a kind of mundane superrealism that charges everyday objects with new force.

On the other hand, you need to maintain variety by strategies of drama and stylistic handling. Chamber cinema–wherever it turns up–offers some unique filmic effects, and maybe sheltering in place is a good time to sample it.

Herewith a by no means comprehensive list of some interesting cinematic chamber pieces. For each title, I link to streaming services supplying it.

Bottles of different sizes

From David Koepp I learned that screenwriters call confined-space movies “bottle” plots. There’s a tacit rule: The audience understands that by and large the action won’t stray from a single defined interior. In a commentary track for the “Blowback” episode of the (excellent) TV show Justified, Graham Yost and Ben Cavell discuss how TV series plan an occasional bottle episode, and not just because it affords dramatic concentration. It can save time and money in production.

Usually the bottle consists of more than a single room. The classic Kammerspielfilms roam a bit within a household and sometimes stray outdoors. But their manner of shooting provides a variety of angles that suggest continuing confinement. Dreyer went further in The Master of the House. He built a more or less functioning apartment as the set, then installed wild walls that let him flank the action from any side. Then editing could provide a sense of wraparound space.

The variations in camera setups throughout the film are extraordinary. Dreyer would create more radically fragmentary chamber spaces in La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928), while his later films would use solemn, arcing camera movements to achieve a smoother immersive effect. (For more on Dreyer’s unique spatial experimentation, here’s a link to my Criterion contribution on Master of the House. I talk about the tricks Dreyer plays with chamber space in Vampyr in an “Observations” supplement on the Criterion Channel.)

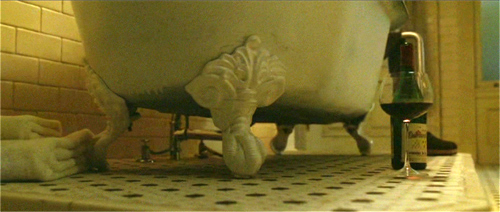

Likewise, Koepp’s screenplay for Panic Room allows David Fincher to move 360 degrees through several areas of a Manhattan brownstone. The film also offers a fine example of how our awareness of domestic details gets sharpened by a creeping camera.

Trust Fincher to find sinister possibilities in a dripping bathtub leg and a kitchen island.

Confined to quarters

Detective Story (1951).

Many chamber movies are based on plays, as you’d expect. Unlike most adaptations, though, they don’t try to “ventilate” the play by expanding the field of action. Or rather, as André Bazin pointed out, the expansion is itself fairly rigorous. They don’t go as far afield as they might.

Bazin praised Cocteau’s 1948 version of his play Les parents terribles (aka “The Storm Within”) for opening up the stage version only a little, expanding beyond a single room to encompass other areas of the apartment. This retained the claustrophobia, and the sense of theatrical artifice, but it spread action out in a way that suited cinema’s urge to push beyond the frame. The freedom of staging and camera placement is thoroughly “cinematic” within the “theatrical” premise.

Depending on how you count, Hitchcock expanded things a bit in his adaptation of Dial M for Murder. Apart from cutting away to Tony at his club, Hitchcock moved beyond the parlor to the adjacent bedroom, the building’s entryway, and the terrace.

An earlier entry on this site talks about how 3D let Sir Alfred give an ominous accent to props: a particularly large pair of scissors, and a more minor item like the bedside clock.

Hitchcock gave us a parlor and a hallway in Rope (1948), but when Brandon flourishes the murder weapon, the framing audaciously reminds us that we aren’t allowed to go into the kitchen.

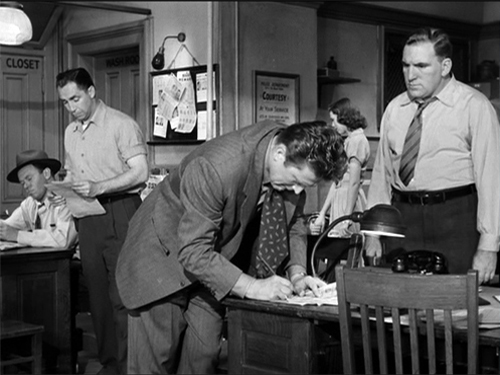

Bazin did not wholly admire William Wyler’s Detective Story (1951), despite its skill in editing and performances; he found it too obedient to a mediocre play. True, the film doesn’t creatively transform its source to the degree that Wyler’s earlier adaptation of The Little Foxes (1941) did; Bazin wrote a penetrating analysis of that film’s remarkable turning point. Detective Story is more obedient to the classic unities, confining nearly all of the action to the precinct station. Although I don’t think Wyler ever shows the missing fourth wall, he creates a dazzling array of spatial variants by layering and spreading out zones of the room. In his prime, the man could stage anything fluently.

As Bazin puts it: “One has to admire the unequaled mastery of the mise-en-scène, the extraordinary exactness of its details, the dexterity with which Wyler interweaves the secondary story lines into the main action, sustaining and stressing each without ever losing the thread.”

Some films are even more constrained. 12 Angry Men (1957), adapted from a teleplay, is a famous example. Once the jury leaves the courtroom, the bulk of the film drills down on their deliberation. Again, the director wrings stylistic variations out of the situation; Lumet claims he systematically ran across a spectrum of lens lengths as the drama developed.

But you don’t need a theatrical alibi to draw tight boundaries around the action. Rear Window (1954), adapted from a fairly daring Cornell Woolrich short story, is as rigorous an instance of chamber cinema as Rope. Here Hitchcock firmly anchors us in an apartment, but he uses optical POV to “open out” the private space.

With all its apertures the courtyard view becomes a sinister/comic/melancholy Advent calendar.

Fassbinder’s Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972) denies us this wide vantage point on the outside world. This space seems almost completely enclosed. But Fassbinder finds a remarkable number of ways to vary the set, the camera angles, and the costumes. We’re immersed in the flamboyant flotsam of several women’s lives. The result is a cascade of goofily decadent pictorial splendors.

It’s virtually a convention of these films to include a few shots not tied to the interiors. At the end, we often get a sense of release when finally the characters move outside. That happens in 12 Angry Men, in Panic Room, in Polanski’s Carnage (2011) , and many of my other examples. Without offering too many spoilers, let’s say Room (2015) makes architectural use of this option.

On the road and on the line

Filmmakers have willingly extended the bottle concept to cars. The most famous example is probably Kiarostami’s Ten (2002), which secures each scene in a vehicle and mixes and matches the passengers across episodes. The strictness of Kiarostami’s camera setups exploit the square video frame and always yield angular shot/reverse shots. They reveal how crisp depth relations can be activated through the passing landscape or in story elements that show up in through the window.

Perhaps Kiarstami’s example inspired Danish-Swedish filmmaker Simon Staho. His Day and Night (2004) traces a man visiting key people on the last day of his life, and we are stuck obstinately in the car throughout. This provides some nifty restriction, most radically when we have to peer at action taking place outside.

Staho’s Bang Bang Orangutang (2005), a portrait of a seething racist, takes up the same premise but isn’t quite so rigorous. We do get out a bit, but the camera stays pretty close to the car. I discuss Staho’s films a little in a very old entry.

Like autos, telephones provide a nice motivation for the bottle, as Lucille Fletcher discovered when she wrote the perennial radio hit, “Sorry, Wrong Number.” The plot consists of a series of calls placed by the bedridden woman, who overhears a murder plot. The film wasn’t quite so stringently limited, but the effect is of the protagonist at the center of several crisscrossed intrigues.

A purer case is the Rossellini film Una voce umana (1948), in which a desperate woman frantically talks with her lover. It relies on intense close-ups of its one player, Anna Magnani.

It’s an adaptation of a Cocteau play, which Poulenc turned into a one-act opera. In all, the duration of the story action is the same as the running time.

I wish Larry Cohen’s Phone Booth displayed a similarly obsessive concentration, but we do have the Danish thriller The Guilty, where a police dispatcher gets involved in more than one ongoing crime. We enjoyed seeing it at the 2018 Wisconsin Film Festival.

And of course car and phone can be combined, as they are in Locke (2013)–another play adaptation. Tom Hardy plays a spookily calm businessman driving to a deal while taking calls from his family and his distraught mistress. Those characters remain voices on the line while he tries to contend with the pressures of his mistakes.

House arrest, arresting houses

Sometimes you must embrace the chamber aesthetic. In 2010 the fine Iranian director Jafar Panahi was forbidden to make films and subjected to house arrest. Yet he continued to produce–well, what? This Is Not a Film (2012) was shot partially on a cellphone within (mostly) his apartment.

Wittily, he tapes out a chamber space within his apartment. Then he reads a script to indicate how absent actors could play it and how an imaginary camera could shoot it.

But his imaginary film still isn’t an actual film, so he hasn’t violated the ban. So perhaps what we have is rather a memoir, or a diary, or a home video? Panahi’s virtual film (that isn’t a film) exists within another film that isn’t a film. Yet it played festivals and circulates on disc and streaming. The absurdity, at once touching and pointed, suggests that through playful imagination, the artist can challenge censorship.

Panahi slyly pushed against the boundaries again with Closed Curtain (2013, above). Shot in his beach house, it strays occasionally outside. Next came Taxi (2015), in which Panahi took up the auto-enclosed chamber movie, with largely comic results.

More recently, he has somehow managed to make a more orthodox film, 3 Faces (2018), which considers the situation of people in a remote village.

The chamber-based premise needn’t furnish a whole movie. As in Room, Kurosawa’s High and Low (1963) is tightly concentrated in its first half. We are in two enclosures, a house and a train. The film then bursts out into a rushed, wide-ranging investigation. Large-scale or less, the chamber strategy remains a potent cinematic force.

They say that the last creatures to discover water will be fish. We move through our world taking our niche for granted. Cinema, like the other arts, can refocus our attention on weight and pattern, texture and stubborn objecthood. We can find rich rewards in glimpses, partial views, and little details. Chamber art has an intimacy that’s at once cozy and discomfiting. Seeing familiar things in intensely circumscribed ways can lift up our senses.

So take a break from the crisis and enjoy some art. But return to the world knowing that for Americans this catastrophe is the result of forty years of monstrous, gleeful Republican dismantling of our civil society. Rebuilding such a society will require the elimination of that party, and the career criminal at its head, as a political force. This pandemic must not become our Reichstag fire.

Yeah, I went there.

Thanks to the John Bennett, Pauline Lampert, Lei Lin, Thomas McPherson, Dillon Mitchell, Erica Moulton, Nathan Mulder, Kat Pan, Will Quade, Lance St. Laurent, Anthony Twaurog, David Vanden Bossche, and Zach Zahos. They’re students in my seminar, and they suggested many titles for this blog entry.

Bazin’s comments on Detective Story come in his 1952 Cannes reportage, published as items 1031-1033, and as a review (item 1180), in Écrits complets vol. I, ed. Hervé Joubert-Laurencin (Paris: Macula, 2018), pp. 918-922, 1059. My quotation comes come from the review, where he does grant that Wyler is the Hollywood filmmaker “who knows his craft best. . . . the master of the psychological film.”

The tableau style of the 1910s probably helped shift Dreyer toward the chamber model, which he learned to modify through editing. I discuss Dreyer’s relation to that style in “The Dreyer Generation” on the Danish Film Institute website. Also related is the web essay, “Nordisk and the Tableau Aesthetic.”

Some other examples could be mentioned, but I didn’t find them on streaming services in the US. It would be nifty if you could see the tricks with chamber space in Dangerous Corner (1934); fortunately it plays fairly often on TCM. There’s also Duvivier’s Marie-Octobre (1959), a tense drama about the reunion of old partisans.

I especially like the 1983 Iranian film, The Key, directed by Ebrahim Forouzesh and scripted by Kiarostami. It’s a charming, nearly wordless story of how a little boy tries to manage household crises when Mother is away. It has the gripping suspense that is characteristic of much Iranian cinema, and the boy emerges as resourceful and heroic (though kind of messy). Kids would like it, I think.

Also, I’ve neglected Asian instances. Maybe I’ll revisit this topic after a while.

P.S. 1 April 2020: Thanks to Casper Tybjerg, outstanding Dreyer scholar, for corrections about the nationality of The Guilty and the Staho films.

Gertrud (1964).