Archive for the 'Directors: Koepp' Category

The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt

Looking is as important in movies as talking is in in plays. Thanks to optical point-of-view shots (POV) and reaction-shot cutting, you can create a powerful drama without words.

Everybody knows this, but sometimes it’s good to be reminded. (I did that here long ago.) Now I have another occasion to explore this terrain. But first: How I spent my summer vacation.

After Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I went to the annual Summer Film College in Antwerp. (Instagram images here.) I’ve missed a couple of sessions (the last entry is from 2015), but this year I returned for another dynamite program. There were three threads. Adrian Martin and Cristina Álvarez López mounted a spirited defense of Brian De Palma’s achievement. Tom Paulus, Ruben Demasure, and Richard Misek gave lectures on Eric Rohmer films. I brought up the rear with four lectures on other topics. As ever, it was a feast of enjoyable cinema and cinema talk, starting at 9:30 AM and running till 11 PM or so. The schedule is here.

After Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I went to the annual Summer Film College in Antwerp. (Instagram images here.) I’ve missed a couple of sessions (the last entry is from 2015), but this year I returned for another dynamite program. There were three threads. Adrian Martin and Cristina Álvarez López mounted a spirited defense of Brian De Palma’s achievement. Tom Paulus, Ruben Demasure, and Richard Misek gave lectures on Eric Rohmer films. I brought up the rear with four lectures on other topics. As ever, it was a feast of enjoyable cinema and cinema talk, starting at 9:30 AM and running till 11 PM or so. The schedule is here.

Because I was fussing with my own lectures, I missed the Rohmer events, unfortunately. I did catch all the De Palma lectures and some of the films. Cristina and Adrian offered powerful analyses of De Palma’s characteristic vision and style. I especially appreciated the chance to watch Carlito’s Way again (script by friend of the blog David Koepp) and to see on the big screen BDP’s last film Passion, which looked fine. I confess to preferring some of his contract movies (Mission: Impossible, The Untouchables, Snake Eyes) to some of his more personal projects, but he takes chances, which is a good thing.

Two of my lectures had ties to my book Reinventing Hollywood. “The Archaeology of Citizen Kane” (should probably have been called “An Archaeology…) pulled together things touched on in blogs, topics discussed at greater length in books, and things I’ve stumbled on more recently. Maybe I can float the newer bits and pieces here some time.

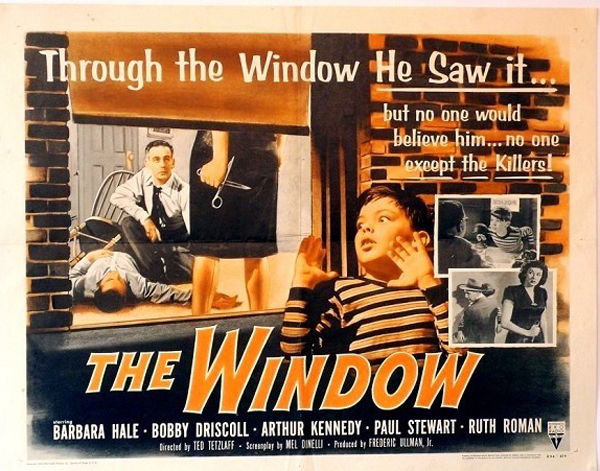

The other lecture took off from my book’s discussion of the emergence of the domestic thriller in the 1940s. We screened The Window (1949), a film that I hadn’t studied closely before. If you can see or resee it before reading on, you might want to do that. But the spoilers don’t come up for a while, and I’ll warn you when they’re impending.

Exploring the how

It is to the thriller that the American cinema owes the best of its inspirations.

Eric Rohmer

One strand of argument in Reinventing Hollywood goes like this.

During the 1930s Hollywood filmmakers mostly concentrated on adapting their storytelling traditions to sync sound and to new genres (the musical, the gangster film). By 1939 or so, those problems were largely solved. As a result, some ambitious filmmakers returned to narrative techniques that were fairly common in the silent era but had become rare in talkies. Those techniques–nonlinear plots, subjectivity, plays with viewpoint and overarching narration–were refined and expanded, thanks to sound technology and quite self-conscious efforts to create more complex viewing experiences.

Wuthering Heights, Our Town, Citizen Kane, How Green Was My Valley, Lydia, The Magnificent Ambersons, Laura, Mildred Pierce, I Remember Mama, Unfaithfully Yours, A Letter to Three Wives, and a host of B pictures and melodramas and war films and mystery stories and even musicals (Lady in the Dark) and romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan)–all these and more attest to new efforts to tell stories in oblique, arresting ways. They seem to have taken to heart a remark from Darryl F. Zanuck (right). It forms the epigraph of my book:

Wuthering Heights, Our Town, Citizen Kane, How Green Was My Valley, Lydia, The Magnificent Ambersons, Laura, Mildred Pierce, I Remember Mama, Unfaithfully Yours, A Letter to Three Wives, and a host of B pictures and melodramas and war films and mystery stories and even musicals (Lady in the Dark) and romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan)–all these and more attest to new efforts to tell stories in oblique, arresting ways. They seem to have taken to heart a remark from Darryl F. Zanuck (right). It forms the epigraph of my book:

It is not enough just to tell an interesting story. Half the battle depends on how you tell the story. As a matter of fact, the most important half depends on how you tell the story.

Put it another way. Very approximately, we might say that most 1930s pictures are “theatrical”–not just in being derived from plays (though many were) but in telling their stories through objective, external behavior. We infer characters’ inner lives from the way they talk and move, the way they respond to each other in situ. And the plot thrusts itself ever forward, chronologically, toward the big scenes that will tie together the strands of developing action. In this respect, even the stories derived from novels depend on this external, linear presentation.

In contrast, a lot of 1940s films are “novelistic” in shaping their plots through layers of time, in summoning a character or an omniscient voice to narrate the action, and in plunging us into the mental life of the characters through dreams, hallucinations, and bits of memory, both visual and auditory. We get to know characters a bit more subjectively, as they report their feelings in voice-over, or we grasp action through what they see and hear.

The distinction isn’t absolute. Some of these “novelistic” techniques were being applied on the stage as well, as a minor tradition from the 1910s on. I just want to signal, in a sketchy way, Hollywood’s 1940s turn toward more complex forms of subjectivity, time, and perspective–the sort of thing that became central for novelists in the wake of Henry James and Joseph Conrad.

In tandem with this greater formal ambition comes what we might call “thickening” of the film’s texture. Partly it’s seen in a fresh opennness to chiaroscuro lighting for a greater range of genres, to a willingness to pick unusual angles (high or low) and accentuate cuts. The thickening comes in characterization too, when we get tangled motives and enigmatic protagonists (not just Kane and Lydia but the triangles of Daisy Kenyon or The Woman on the Beach). There’s also a new sensitivity to audiovisual motifs that seem to decorate the core action–the stripey blinds of film noir but also symbolic objects (the snowstorm paperweights in Kane and Kitty Foyle, the locket in The Locket, the looming portraits and mirrors that seem to be everywhere). Add in greater weight put on density and details of staging, enhanced by recurring compositions, as I discuss in an earlier entry.

One genre that comes into its own at the period relies heavily on the new awareness of Zanuck’s how. That’s the psychological thriller.

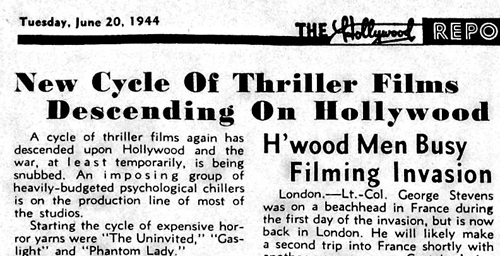

I’ve written at length about this characteristic 1940s genre (see the codicil below), so I’ll just recap. The 1930s and 1940s saw big changes in mystery literature generally. The white-gloved sleuth in the Holmes/Poirot/Wimsey vein met a rival in the hard-boiled detective. Just as important was the growing popularity of psychological thrillers set in familiar surroundings. The sources were many, going back to Wilkie Collins’ “sensation fiction” and leading to the influential works by Patrick Hamilton (Rope, Hangover Square, Gaslight). In the same years, the domestic thriller came to concentrate on women in peril, a format popularized by Mary Roberts Rinehart and brought to a pitch by Daphne du Maurier. The impulse was continued by many ingenious women novelists, notably Elizabeth Sanxay Holding and Margaret Millar. The domestic thriller was a mainstay of popular fiction, radio, and the theatre of the period, so naturally it made its way into cinema.

Literary thrillers play ingenious games with the conventions of the post-Jamesian novel. We get geometrically arrayed viewpoints (Vera Caspary’s Laura, Chris Massie’s The Green Circle) and fluid time shifts (John Franklin Bardin’s Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly). There are jolting switches of first-person narration (Kenneth Fearing’s The Big Clock), sometimes accessing dead characters (Fearing’s Dagger of the Mind). There are swirling plunges into what might be purely imaginary realms (Joel Townsley Rogers’ The Red Right Hand).

Ben Hecht remarked that mystery novels “are ingenious because they have to be.” Formal play, even trickery, is central to the genre, and misleading the reader is as important in a thriller as in a more orthodox detective story. No wonder that the genre suited filmmakers’ new eagerness to experiment with storytelling strategies.

Vision, danger, and the unreliable eyewitness

What does a thriller need in order to be thrilling? For one thing, central characters must be in mortal jeopardy. The protagonist is likely to be a target of impending violence. One variant is to build a plot around an attack on one victim, but to continue by centering on an investigator or witness to the first crime who becomes the new target. In Ministry of Fear, our hero brushes up against an espionage ring. While he pursues clues, the spies try to eliminate him.

Accordingly, the cinematic narration intensifies the situation of the character in peril. A tight restriction of knowledge to one character, as in Suspicion, builds curiosity and suspense as we wait for the unseen forces’ next move. Alternatively, a “moving-spotlight” narration can build the same qualities. In Notorious, we’re aware before Alicia is that Sebastian and his mother are poisoning her. Even “neutral” passages can mask story information through judiciously skipping over key events, as happens in the opening of Mildred Pierce.

Using point-of-view techniques to present the threats to the protagonist brought forth a distinctive 1940s cycle of eyewitness plots. Here the initial crime is seen, more or less, by a third party, and this act is displayed through optical POV devices. There typically follows a drama of doubt, as the eyewitness tries to convince people in authority that the crime has been committed. Part of the doubt arises from an interesting convention: the eyewitness is usually characterized as unreliable in some way. Sooner or later the perpetrator of the crime learns of the eyewitness and targets him or her for elimination. The cat-and-mouse game that ensues is usually resolved by the rescue of the witness.

The earliest 1940s plot of this type I’ve found isn’t a film, but rather Cornell Woolrich’s story “It Had to Be Murder,” published in Dime Detective in 1942. (It later became Hitchcock’s Rear Window. But see the codicil for earlier Woolrich examples.) The earliest film example from the period may be Universal’s Lady on a Train (1945), from an unpublished story by Leslie Charteris.

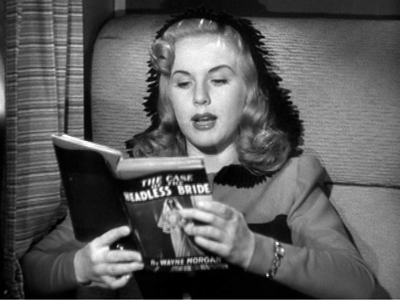

The opening signals that this will be a murder-she-said comedy. Nicki Collins is traveling from San Francisco to New York and reading aloud, in a state of tension, The Case of the Headless Bride (a dig at the Perry Mason series?). As the train pauses in its approach to Grand Central she comes to a climactic passage: “Somehow she forced her eyes to turn to the window. What horror she expected to see…” Nicki looks up from her book to see a quarrel in an apartment. One man lowers the curtain and bludgeons the other, and as Nicki reacts in surprise, the train moves on.

The over-the-shoulder framings don’t exactly mimic Nicki’s optical viewpoint, but they do attach us to her act of looking. Reverse-angle cuts show us her reactions. Her recital of the novel’s prose establishes her suggestibility and an overactive imagination. These qualities fulfill, in a screwball-comedy register, the convention of the witness’s potential unreliability. We know her perception is accurate, but her scatterbrained chatter justifies the skepticism of everybody she approaches. As the plot unrolls, her efforts to solve the mystery make her the killer’s new target.

More serious in tone was Lucille Fletcher’s radio drama, “The Thing in the Window” from 1946. In the same year, Cornell Woolrich rang a new change on the “Rear Window” theme with the short story “The Boy Who Cried Wolf,” and Twentieth Century–Fox released Shock. In this thriller an anxious wife waits in a hotel room for her husband, who has been away at war for years. Elaine Jordan’s instability is indicated by a dream in which she stumbles down a long corridor toward an enormous door that she struggles to open.

Awakening, Elaine nervously goes to the window in time to see a quarrel in an adjacent room. She watches as a man kills his wife.

Now she’s pushed over the edge. As bad luck would have it, the killer is a psychiatrist. When he learns that Elaine saw him, he takes charge of her case. He spirits her away to his private sanitarium, where he’ll keep her imprisoned with the help of his nurse-paramour.

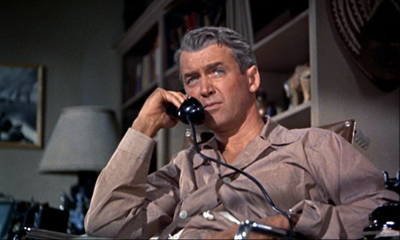

I was surprised to learn of this eyewitness-thriller cycle because the prototype of this plot was for me, and maybe you too, was a later film, Rear Window (1954). Again, the protagonist believes he’s seen a crime, though here it’s the circumstances around it rather than the act itself. Accordingly a great deal of the plot is taken up with the drama of doubt, as the chairbound Jeff investigates as best he can. He spies on his neighbor and recruits the help of his girlfriend Lisa and his police detective pal.

Hitchcock, coming from the spatial-confinement dramas Rope and Dial M for Murder, followed the Woolrich story in making his protagonist unable to leave his apartment. Following Woolrich’s astonishingly abstract descriptions of the protagonist’s views, Hitchcock made optical POV the basis of Jeff”s inquiry. By turning Woolrich’s protagonist into a photojournalist, he enhanced the premise through use of Jeff’s telephoto lenses.

Woolrich and Hitchcock’s reliance on spatial confinement worked to the advantage of the unreliable-witness convention. How much could you really see from that window? Jeff can’t check on the background information his cop friend reports. Besides, Jeff is bored and susceptible to conclusion-jumping. “Right now I’d welcome trouble.”

Hitchcock, who kept an eye on his competitors, doubtless was aware of The Window (1949), an earlier entry in the cycle. Derived from Woolrich’s “Boy Who Cried Wolf,” this RKO film has some intriguing things to teach us about the mechanics of thrillers and about the 1940s look and feel.

Spoilers follow.

At the window, and outside it

On a hot summer night, the boy Tommy Woodry is sleeping on a tenement fire escape one floor above his family’s apartment. He awakes to see Mr. and Mrs. Kellerson murder a sailor they have robbbed. Next morning Tommy tries to report the crime to his parents and then the police, but no one will believe him because he’s long been telling fantastic tales. A family emergency leaves him alone in the apartment, and the Kellersons lure him out. After nearly being killed by them, he flees to a tumbledown building nearby. There he evades Mr. Kellerson, who falls to his death. With Tommy’s parents and the police now believing him, he’s rescued from his perch on a precarious rafter.

Woolrich’s original story confines us strictly to Tommy’s range of knowledge, but in the interest of suspense screenwriter Mel Dinelli uses moving-spotlight narration. When Tommy flees the fire escape, for instance, we follow the efforts of the Kellersons to rid themselves of the body. This becomes important to show how difficult it will be for Tommy to prove his story. There’s also a moment during their coverup when the camera lingers on Mrs. Kellerson, both in profile and from the back, as if she were hesitating about going along with the plan.

This shot prepares for the climax, when as her husband is about to shove Tommy off the fire escape, she blocks his gesture and allows Tommy to escape across the rooftops.

Likewise, Woolrich’s story simply reports that the young hero waited at the police station for the result of Detective Ross’s visit to the Kellersons. The film’s narration attaches us to Ross and creates a scene of considerable suspense when we wonder if Ross will discover any clues to the murder. And whereas in the story Tommy must worry about how Kellerson will get to him, through crosscutting between Kellerson in the kitchen and Tommy locked in his room we know everything that’s happening. This permits a wry passage of suspense in which Kellerson toys with Tommy by letting him think he’s retrieving the door’s key.

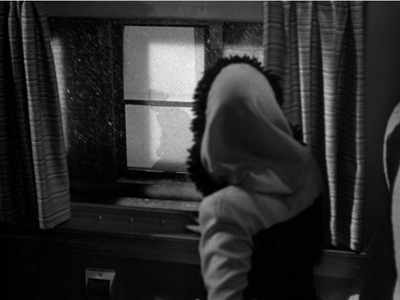

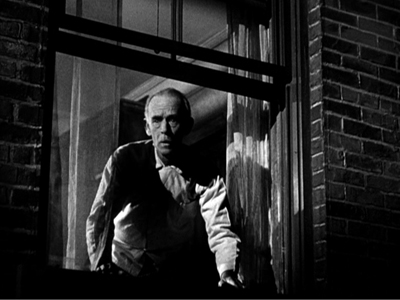

In contrast to the moving-spotlight approach, though, crucial passages are rendered with a limited range of knowledge. Optically subjective shots come to the fore here, as when Tommy witnesses the murder.

It seems likely that Hitchcock’s early American films heightened filmmakers’ awareness of subjective optical techniques, and here director Ted Tetzlaff puts them to good use. The script I’ve seen for The Window doesn’t indicate such pure POV shots, instead opting for something like what we get in Lady on a Train. “CAMERA is ON the pillow back of Tommy, so that we see his head in the f.g and the window in the b.g.” There is a shot matching these directions, but it’s surrounded by the straight POV imagery framed by Tommy’s frightened stare.

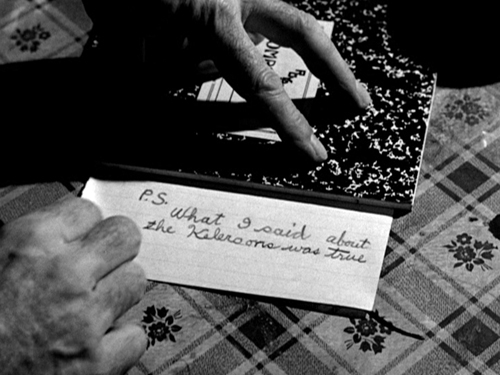

The decision by Tetzlaff and his colleagues to rely on optical POV is confirmed when, during Ross’s visit, he spots a stain on the floor.

Is this a bloodstain that will put Ross on the scent? Crucially, we haven’t seen the lethal scissors leave a trace. Kellerson explains the stain as coming from a leak in the ceiling. Obediently Ross looks up and, to prolong the suspense, so does Mrs. Kellerson, apparently as apprehensive as we are. That extra shot of her nicely delays the reveal: there is a leak above them.

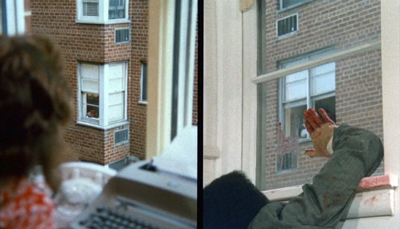

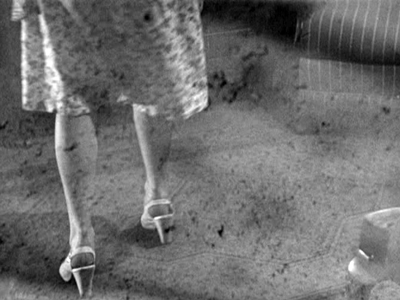

In tune with the tendency to thicken the narrative texture, this POV dynamic reappears at other moments. Tommy sees his parents leave, and the reverse angle reveals that the Kellersons see them too, and so they know that Tommy is now unguarded.

At the climax in the abandoned tenement, Tommy spots his father and the policeman outside. He shouts to get their attention, but they can’t hear.

But Kellerman does hear Tommy and uses the sound to stalk him.

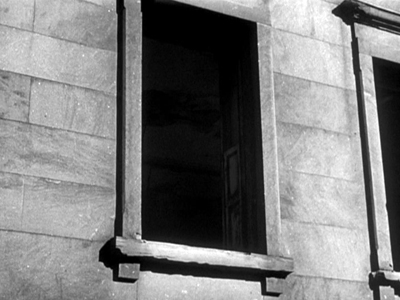

1940s stylistic thickening includes the use of audiovisual motifs that impose a distinctive look on the film. So a movie called The Window begins, after a couple of establishing shots of Manhattan street life, with a shot of a window.

This one has no special importance in the plot, but it announces the image that will recur throughout the movie. By shooting ordinary scenes through window frames, Tetzlaff reminds us that the locals live partly through those windows and the fire escapes outside.

Naturally enough, Kellerson plans to kill Tommy by having him tumble from the fire escape outside the window.

The film’s key image reappears at the end, when after Kellerson’s fall a new crop of witnesses take to their windows.

Another motif is the vertical link between the two apartments, given in looming shots of the staircase (a common piece of iconography in 1940s cinema) and in cutting that links Tommy’s bedroom to the Kellersons above him. He listens to their footsteps through his ceiling.

The next layer up, the rooftop, serves as a route from the families’ building to the abandoned one, and eventually the chase will play out there.

Vertical space more generally is important at the very start of the film. During Tommy’s mock ambush of his playmates, we look down over his shoulder. At the very end, Kellerson has trapped Tommy on the broken rafter.

The rooftop and rafter become part of another pattern, the circular one that rules the plot. Woolrich’s original story doesn’t feature the opening we have, showing Tommy in the abandoned tenement pretending to snipe at the other boys. Nor does the shooting script I’ve seen. Starting the film there establishes the locale of the climactic chase, while creating parallel scenes of Tommy hiding. We even get to see the broken rafter early on, when Tommy is prowling around his playmates.

The result is a pleasing, somewhat shocking symmetry of action: Tommy pretends to kill somebody at the start, and he succeeds in killing someone at the end.

The film offers a cluster of images that are recycled with variations, amplifying the basic story action through patterns of space and visual design.

The thickening of texture isn’t only pictorial. The drama of doubt involves a questioning of parental wisdom. Tommy’s mother actually endangers her boy by asking him to apologize to Mrs. Kellerson. More central is a testing of the father’s faith in his son. Tommy’s dilemma is to tell the truth even though he’ll be disbelieved by all the figures of social authority. The father’s increasingly desperate efforts to change Tommy’s story are revealed in Arthur Kennedy’s delicate portrayal of exasperation–at first gentle, then severe and nearly abusive.

Ed Woodry fails in his duty. The adults aren’t capable of protecting the child. A conventional plot would’ve had Ed redeem himself by rescuing his son, but the film we have leaves the killing to Tommy. It’s a grim condemnation of the people supposed to protect him.

Another convention, it seems, of the eyewitness film involves punishing the peeper. In Lady on a Train, Nicki has to brave a spooky house and risk death. Elaine of Shock suffers in the mental institution, and in Rear Window Jeff eventually falls from the very window that was his interface with the courtyard. Tommy, who acknowledges his inclination to tell whoppers, is subjected to a final burst of peril. After Kellerson has plunged to his death, Tommy is left in mid-air and he must jump to the firemen’s waiting net. In the epilogue, he announces that he’s learned his lesson, not least because of several brushes with death.

Revising the rules

The 1940s eyewitness cycle laid out some options for future thrillers. Rear Window, as we’ve seen, crystallizes the plot premise in rather pure form, and interestingly that was copied almost immediately in the Hong Kong film Rear Window (Hou chuang, 1955). Some passages are straight mimicry, albeit on a much smaller budget.

Thereafter, the eyewitness premise resurfaced, notably in Sisters (1973, with split screen) and with another child protagonist in The Client (1994).

In recent decades filmmakers have revised the premise in ways typical of post-Pulp-Fiction Hollywood. Vantage Point (2008) multiplies the eyewitnesses and uses replays to conceal and eventually reveal information. The Girl on the Train (2016), streamlining the multiple-viewpoint structure of the novel, alternates plotlines centered on three women. The novel and the film recast the eyewitness schema by making the eyewitness unable to recall exactly what she saw, thanks to an alcoholic blackout. (It’s a cousin to our old 1940s friend amnesia). This uncertainty raises the possibility that the eyewitness is actually the killer.

With its goal-directed protagonist and trim four-part plot structure, The Window is a completely classical film. As often happens, a forgivably flawed character gains our sympathy by being treated unfairly but triumphs in the end. And in the film’s integration of dramatic and pictorial elements, its alternation of subjectivity and wide-ranging narration for the sake of suspense, it nicely illustrates some ways in which 1940s filmmakers recast classical traditions for the thriller format and opened up new storytelling options.

Woolrich’s “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” is available under the title “Fire Escape” in Dead Man Blues (Lippincott, 1948), published under the pseudonym William Irish. Woolrich, ever the formalist, initially gave “It Had to Be Murder”/”Rear Window” my dream title: “Murder from a Fixed Viewpoint.” An earlier Woolrich story, “Wake Up with Death” from 1937, flips the viewpoint: A man emerges from drunken sleep to discover a murdered woman at his bedside and gets a call from someone who claims to have watched him commit the crime. Then there’s “Silhouette” from 1939, in which a couple witness a strangling projected on a window shade. See Francis M. Nevins, Jr.’s exhaustive Cornell Woolrich: First You Dream, Then You Die (Mysterious Press, 1988), 158, 186, 245. There are doubtless many earlier eyewitness thrillers, which the indefatigable Mike Grost could tabulate.

The screenplay by Mel Dinelli that I consulted, with help from Kristin, is a rather detailed shooting script dated 23 October 1947. It is housed in the Dore Schary collection at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Dinelli benefited from the thriller boom in his screenplays for The Spiral Staircase, The Reckless Moment, House by the River, Cause for Alarm!, and Beware, My Lovely.

There are plenty of discussions of thrillers on this site; try here and here. Apart from the chapter in Reinventing Hollywood, you can find overviews here and here. See also the category 1940s Hollywood. I discuss the sort of plot fragmentation characteristic of some current Hollywood cinema, built on 1940s premises, in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

For more images from my summer movie vacation, visit our Instagram page.

P.S. 24 July: Thanks very much to Bart Verbank for correcting my embarrassing name error in Rear Window! Also, if you’re wondering why I didn’t mention the very latest instantiation of the the eyewitness plot, A. J. Finn’s Woman in the Window, it’s because (a) I haven’t read it; and (b) I resist reading a book with a title swiped from a Fritz Lang movie.

DB accepts a fine Kriek from the Antwerp Summer Film College team: David Vanden Bossche, Tom Paulus, Lisa Colpaert, and Bart Versteirt.

The compleat screenwriter: David Koepp gives notes

DB here:

Regular visitors will know of my interest in David Koepp, screenwriter (Jurassic Park, War of the Worlds) and director (Ghost Town, Premium Rush). In 2013 I wrote an entry based on a long interview he kindly gave me.

Back in March of this year, David visited UW—Madison. It’s not strictly his alma mater; he left us to finish up at UCLA. Still, he retains ties to Wisconsin and recalls that while he was here he was inspired by our vast film society scene and some courses in the film and theatre departments. Across 2 ½ days he shared his experiences in a variety of settings, including Q & A’s after screenings of War of the Worlds, The Paper, and Ghost Town.

David is a craftsman who thinks about what he does. I’d call him an intellectual screenwriter if I didn’t think that made him sound more cerebral and austere than he actually is. He’s a vivacious, articulate presence: a born teacher, endowed with wit and good humor. During his visit he threw out plenty of ideas. Some are valuable for aspiring screenwriters, and others are intriguing guides for those of us who study movies.

Career paths

David Koepp and Maria Belodubrovskaya, 12 March 2015.

Starting out: If you want to write screenplays, a post at an agency isn’t ideal. It will, though, help you if you want to become a producer. Likewise, writing coverage can sensitize you to story, but it’s usually not the best route to becoming a screenwriter. It is a good path to becoming a creative executive.

Try to find a job that lets you write every day. A physically exhausting job makes you want to come home and zone out at night, when you should be writing.

Working from models: David learned a great deal from Kasdan’s Body Heat script. He recommends reading the first page of Hemingway’s novel To Have and to Have Not for a strong example of how character and story can co-exist and both start with strength and urgency.

David also urges writers to study plays, especially modern works by Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller. [In the discussion, I failed to sell Chekhov as an alternative.]

Prepare for ups and downs, no matter how far you advance. Failure can encourage you to quit, but failure is endemic to the job and must be confronted the way an athlete learns to deal with injury. You must be resilient. “It’s dealing with failure that defines you as a person.”

Creative failures are, oddly, easier to handle if you’re directing because then the decision was yours. You understand how and why the mistakes were made. It’s harder to live with when you feel your script was in perfectly good shape and a director screwed it up or failed to express it clearly.

Maintaining a career

Death Becomes Her (1992).

“The first responsibility of an artist is to pay your rent.”

“Your ideas are your currency.” Talking about your script too much is a mistake. Keep your ideas to yourself as long as you can; otherwise you lose the need to write the script.

The time to talk is at the pitch meeting. It’s a bit disagreeable, but it forces you to have a clear-cut plot. “Until you tell it, you probably don’t have meaningful command of it.” Practice once or twice with a friend before the pitch, but not so many times that it becomes rote.

“Everything after the word no is white noise.”

Your first collaborator is the producer. Take seriously the problems he or she points out, but don’t automatically accept the solutions offered. Other voices are there to raise questions and point out problems, but not to solve them. Don’t let them take that job away from you; you’ll lose your voice.

The trick is to get your vision into the screenplay so that the director and the producer see it as you do. A good script is “all about clarity.” You can’t include camera directions, but every page should have a strong, simple image, briefly expressed. For example, in Death Becomes Her, Meryl Streep is teetering at the top of the stairs, before her husband pushes her down them. The script says: “She hovers there, like Wile E. Coyote at the top of a cliff.” It wasn’t a camera direction, but it called up a certain style in the mind of the reader, and, eventually, the director.

Read your dialogue out loud, playing all the parts.

Be prepared to have to write some things by committee, but, again, listen to the problems pointed out and think about the suggestions. But never let them fix your problems or take command of your story for you. It will lose its distinctiveness. The adage is: “No one of us is as dumb as all of us.”

The creative process

“Appeasing the audience gods”: Who will want to see your story?

The writer’s trance: “You get lost in it if it’s going well.” Play music, especially soundtracks to movies with a similar feel.

David’s steps:

*Thinking: “collecting string,” coming up with ideas on your own.

*Research: reading, interviewing, going on site. For The Paper, David and his brother visited a newsroom and got stories from journalists.

*Outlining: 3 x 5 note cards consisting of the obligatory scenes (“small, unintimidating chunks of story”). The cards can be arranged into five or so columns, corresponding to beginning, middle, and end. The card array gets turned into a prose outline (10-25 pages), with dialogue. “This is the heavy lifting.” At this point, the cards have served their purpose and you probably don’t return to them.

*First draft: Basically, something you can revise from. Those revisions should be successively shorter, so the story is never obscured by excessive description, no matter how well-written. “Scripts are not about pretty writing.” Be ready to cut. “You need less than you think you do.”

The 3-act structure is like musical scales, “something you can embrace or something you can rebel against.” But without some sort of structural approach, “it is all forest, no trees.”

Hollywood rewards success, but it also expects repetition of success. Your job is to try to do something different as frequently as possible. “I tried to write in every genre that interests me.”

Over twenty-seven years, David wrote about thirty scripts. Of them, roughly two dozen got made. Of that number, nine were originals. The most successful original was Panic Room, which was born from two ideas: the popularity of “safe rooms” in urban mansions, and the claustrophobia he once experienced when trapped in a small domestic elevator in a Manhattan townhouse.

Adapting a novel: In adapting, he first writes up an outline of the book itself, as written, to internalize its its structure, before creating the movie’s structure. Don’t worry about imitating the prose texture, especially passages presenting mental states. Film is about images and sounds, visible behavior and speech. But you can be faithful to the spirit of the novel. The War of the Worlds, though an update, respects Wells’ ideas and characterization.

Don’t pass up chances to use your craft; any job can be fun. Some assignments are painting, some are carpentry.

Rewrites may be imposed by studio staff or stars (who often push for a better or bigger role). You have to fight your way through them, taking what can help and talking your way out of ideas that can hurt. “Everything is a negotiation.”

In the shooting phase, the writer is often in a black hole, with nothing much to do. You needn’t be on the set, but do have to stay available if something needs to be done.

Studying film

The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997).

What would David study if he were an academic? “I’d love to take a course that traces influences, such as the connection between Shaw Brothers and Tarantino. In other words, get away from traditional categories of genre and national cinemas and focus on conections of thought and style between apparently diverse filmmakers.”

Would he focus on directors rather than screenwriters? Yes, because the director is “the overriding creative force.” Today a screenwriter needs a director’s support to get a film done. Moreover, directors “have a degree of control you can’t imagine.” They shape performances, tone, imagery, and sound, and they often govern script rewrites. David was struck seeing You Can’t Take It with You on stage and then noticing how Capra’s film version made the play’s amiable patriarch into a capitalist villain–a characteristic Capra touch.

Accordingly, major directors like Fincher become obstinate about details. “You have to be belligerent. There’s no other way.” David was present when Spielberg couldn’t get the overhead shot he wanted in The Lost World: Jurassic Park. The plan was to frame raptors rushing through tall grass from above, so that all we see are trails converging on the fleeing people. But on the first visit to the location, the grass wasn’t tall enough. “If I don’t have the grass,” said Spielberg, “I don’t have a shot.” Tall grass had to be replanted and the shot taken later. [DB: I think that shot is borrowed, somewhat clumsily, in the Wachowskis’ Jupiter Ascending.]

Producers also can control the process. Accordingly, David would also study ones with strong identities like William Castle and Sam Spiegel.

David’s affinity is for classic Hollywood. As a kid watching on TV, he liked horror films and Sherlock Holmes movies. He likes modern films in the classic tradition. When he was 14 he saw Star Wars soon after Jaws, and these had strong impact on him. The only comparable phenomenon today, he thinks, is the Lord of the Rings trilogy.

On noir, especially Snake Eyes

Snake Eyes (1998).

What made him write so many noirish thrillers? Probably his childhood; your tastes are formed between 14 and 24. He experienced the darkness and paranoia of the 1970s, intensified by the fact of his parents divorcing. An important influence was Rosemary’s Baby as well, a film he still reveres.

Filmmakers love noir, but don’t describe your project as a noir. Studios hate the term. They believe it doesn’t sell. Panic Room isn’t a noir, the producers were told; it’s like “an Ashley Judd movie.” [Presumably before that became a problematic term too.—DB]

The morality of noir is tricky. You can have unsympathetic protagonists, but be careful handling the bag-of-money movie. You can’t reward greed. “You can’t get away with the money.” In The Killing, the money has to blow away. True Romance was less powerful, ending with the kids on the beach dancing and rich. This concern isn’t mainly about morality, just an ending that satisfies.

David wrote Carlito’s Way as a 30s Warners gangster film, with a characteristic downbeat ending. Hence the need to lead the audience to expect a dying fall: A flashback and the voice of a “nearly-beyond-the-grave narrator.” The whole movie takes place in an instant.

In Snake Eyes, David welcomed the noirish formal problem of telling the same story three times, as in Rashomon. The tripled presentation would have occupied Act 2. What about the optical POV switches? Typically, shots aren’t fully scripted, and they weren’t here: the POV angles were De Palma’s choice.

Originally the film had a classic noir flashback structure. The opening would show flood waters after the storm, with floating chips, playing cards, and a blackjack table. Then the main story would take us into the past. The climax, back in the present, was to have been a fight in the water with Sinese trying to drown Cage.

As for giving away a key element midway through: David thought it would work. (Hitchcock did it in Vertigo.) But audiences didn’t like it. They seem to feel uncomfortable knowing something big that the main character doesn’t. But what about a movie like Ransom, which also reveals the villain? Not such a problem, says David, because if you show a character lying, you should do so quickly—not hold off for many scenes and reveal it a fair distance from the climax.

“This is the fun part of storytelling: What do we tell ‘em, and when?” [DB: In Film Art, we put it this way: “Who knows what when?”]

Envoi

What about the writers’ tasks in the late phases of preproduction? As I was finishing this entry, David sent a dispatch from Inferno, Ron Howard’s latest Dan Brown adaptation. After moving from Budapest to Florence to Venice, the production starts shooting tomorrow. David writes:

David Koepp visiting the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, with Vance Kepley, Director; Amy Sloper, Head Film Archivist; and Mary Huelsbeck, Assistant Director.

David Koepp: Making the world movie-sized

Stir of Echoes (1999).

DB here:

For a long time, Hollywood movies have fed off other Hollywood movies. We’ve had sequels and remakes since the 1910s. Studios of the Golden Era relied on “swipes” or “switches,” in which an earlier film was ripped off without acknowledgment. Vincent Sherman talks about pulling the switch at Warners with Crime School (1938), which fused Mayor of Hell (1933) and San Quentin (1937). Films referred to other films too, sometimes quite obliquely (as seen in this recent entry).

People who knock Hollywood will say that this constant borrowing shows a bankruptcy of imagination. True, there can be mindless mimicry. But any artistic tradition houses copycats. A viable tradition provides a varied number of points of departure for ambitious future work. Nothing comes from nothing; influences, borrowings, even refusals–all depend on awareness of what went before. The tradition sparks to life when filmmakers push us to see new possibilities in it.

From this angle, the references littering the 1960s-70s Movie Brats’ pictures aren’t just showing off their film-school knowledge. Often the citations simply acknowledge the power of a tradition. When Bonnie, Clyde, and C. W. Moss hide out in a movie theatre during the “We’re in the Money” sequence from Gold Diggers of 1933, the scene offers an ironic sideswipe at their bungled bank job, and a recollection of Warner Bros. gangster classics. When a shot in Paper Moon shows a marquee announcing Steamboat Round the Bend, it evokes a parallel with Ford’s story about an older man and a girl. Even those who despised the tradition, like Altman, were obliged to invoke it, as in the parodic reappearances of the main musical theme throughout The Long Goodbye.

But tradition is additive. As the New Hollywood wing of the Brats—Lucas, Spielberg, De Palma, Carpenter, and others—revived the genres of classic studio filmmaking, they created modern classics. The Godfather, Jaws, Star Wars, Carrie, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and others weren’t only updated versions of the gangster films, horror movies, thrillers, science-fiction sagas, and adventure tales that Hollywood had turned out for years. They formed a new canon for younger filmmakers. Accordingly, the next wave of the 1980s and 1990s referenced the studio tradition, but it also played off the New Hollywood. For “New New Hollywood” directors like Robert Zemeckis and James Cameron, their tradition included the breakthroughs of filmmakers only a few years older than themselves.

So today’s young filmmaker working in Hollywood faces a task. How to sustain and refresh this multifaceted tradition? One filmmaker who writes screenplays and occasionally directs them has found some lively solutions.

From the ’40s to the ’10s

The Trigger Effect (1996).

David Koepp was fourteen when he saw Star Wars and eighteen when he saw Raiders. By the time he was twenty-nine he was writing the screenplay for Jurassic Park. Later he would provide Spielberg with War of the Worlds (2005) and Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008). Across the same period he worked with De Palma (Carlito’s Way, 1993; Mission: Impossible, 1996; Snake Eyes, 1998), and Ron Howard (The Paper, 1994), as well as younger directors like Zemeckis (Death Becomes Her, 1992), Raimi (Spider-Man, 2002), and Fincher (Panic Room, 2002). The young man from Pewaukee, Wisconsin who grew up with the New Hollywood became central to the New New Hollywood, and what has come after.

He spent two years at UW–Madison, mostly working in the Theatre Department but also hopping among the many campus film societies. He spent two years after that at UCLA, enraptured by archival prints screened in legendary Melnitz Hall. The result was a wide-ranging taste for powerful narrative cinema. He came to admire 1970s and 1980s classics like Annie Hall, The Shining, and Tootsie. As a director, Koepp resembles Polanski in his efficient classical technique; his favorite movie is Rosemary’s Baby, and one inspiration for Apartment Zero (1988) and Secret Window was The Tenant. You can imagine Koepp directing a project like Frantic or The Ghost Writer.

Old Hollywood is no less important to Koepp. Among his favorites are Double Indemnity, Mildred Pierce, and Sorry, Wrong Number. In conversation he tosses off dozens of film references, from specifically recalled shots and scenes to one-liners pulled from classics, like the “But with a little sex” refrain from Sullivan’s Travels.

It’s not mere geek quotation-spotting, either. The classical influence shows up in the very architecture of his work. He creates ghost movies both comic and dramatic, gangster pictures, psychological thrillers, and spy sagas. The Paper revives the machine-gun gabfests of His Girl Friday, while Premium Rush gives us a sunny update of the noir plot centered on a man pursued through the city by both cops and crooks.

One of the greatest compliments I ever got (well, it seemed like a compliment to me, anyway) was when Mr. Spielberg told me I’d missed my era as a screenwriter–that I would have had a ball in the 40s.

Like his contemporary Soderbergh, Koepp sustains the American tradition of tight, crisp storytelling. He also thinks a lot about his craft, and he explains his ideas vividly. His interviews and commentary tracks offer us a vein of practical wisdom that repays mining. It was with that in mind that I visited him in his Manhattan office to dig a little deeper.

Humanizing the Gizmo

Today, the challenge is the tentpole, the big movie full of special effects. A tentpole picture needs what Koepp calls its Gizmo, its overriding premise, “the outlandish thing that makes the big movie possible.” The Gizmo in in Jurassic Park is preserved DNA; the Gizmo in Back to the Future is the flux capacitor. “The more outlandish the Gizmo, the harder it is to write everybody around it.” The problem is to counterbalance scale with intimacy. “You need to offset what’s ‘up there’ [Koepp raises his arm] with things that are ‘down here’ [he lowers it].” This involves, for one thing, humanizing the characters. A good example, I think, is what he did with Jurassic Park.

Crichton’s original novel has a lot going for it: two powerful premises (reviving dinosaurs and building a theme park around them), intriguing scientific speculation, and a solid adventure framework. But the characterizations are pallid, the scientific monologues clunky, and the succession of chases and narrow escapes too protracted.

The film is more tightly focused. In the novel, Dr. Grant is an older widower and has no romantic relation to Ellie; here they’re a couple. In the original, Grant enjoys children; in the film, he dislikes them. Accordingly, Koepp and Spielberg supply the traditional second plotline of classic Hollywood cinema. Alongside the dinosaur plot there’s an arc of personal growth, as Grant becomes a warmer father-figure and he and Ellie become short-term surrogate parents for Tim and Alexa.

Similarly, Crichton’s hard-nosed Hammond turns into a benevolent grandfather; in the film, his defensive attitude toward the park’s project collapses when his children are in danger. Even Ian Malcolm, mordantly played by Jeff Goldblum (stroking some of the most unpredictable line-readings in modern cinema), can be seen as the wiseacre uncle rather than the smug egomaniac of the novel.

Crichton’s tale of scientific overreach becomes a family adventure. Koepp’s consistent interest in the crises facing a family meshes nicely with the same aspect of Spielberg’s work, and it gives the film an appeal for a broad audience. In the original, Tim is a boy wonder, well-informed about dinosaurs and skilled at the computer. Koepp’s screenplay shares out these areas of expertise, making Lex the hacker and letting her save the day by rebooting the park’s defense system. There’s a model of courage and intelligence for everybody who sees the movie.

While giving Crichton’s novel a narrative drive centered on the surrogate family, Koepp also creates a more compressed plot. For one thing, he slices out the chunks of scientific explanation that riddle the novel. The main solution came, Koepp says, when Spielberg pointed out that modern theme parks have video presentations to orient the visitors. Koepp and Spielberg created a short narrated by “Mr. DNA,” in an echo of the middle-school educational short “Hemo the Magnificent.” The result provides an entertaining bit of exposition that condenses many scenes in the book. Why Mr. DNA has a southern accent, however, Koepp can’t recall.

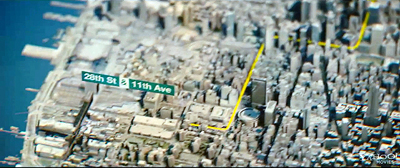

Compression like this allows Koepp to lay the film out in a well-tuned structure. Most of his work fits the four-part model discussed by Kristin and me so often (as here). In Storytelling in the New Hollywood, she shows how Jurassic displays the familiar pattern of goals formulated (part one), recast (part two), blocked (part three), and resolved (part four). When I visited Koepp, he was laying out 4 x 6 cards for his screenplay for Brilliance, seen above. He remarked that the array fell into four parts, with a midpoint and an accelerating climax.

For a smaller-scale example of compression, consider a classic convention of heist movies: the planning session. In Mission: Impossible, Ethan Hunt reviews his plan for accessing the computer files at CIA headquarters. As he starts, the reactions of the two men he’s recruiting foreshadow what they’ll do during the break-in: the sinister calculation of Krieger (Jean Reno), in particular, is emphasized by De Palma’s direction. Ethan’s explanation of the security devices shifts to voice-over and we leave the train compartment to follow an ineffectual bureaucrat making his way into the secured room. (The room and the gadgets were wholly made up for the film; the Langley originals were far more drab and low-tech.)

Everything that will matter later, including the heat-sensitive floor and the drop of moisture that can set off the alarms, is laid out visually with Ethan’s explanation serving as exposition. Like the Mr. DNA short, this set-piece, extravagant in the De Palma mode, serves to specify how things in this story will work. Here, however, the task involves what Koepp calls “baiting the suspense hook. “ Each detail is a security obstacle that Hunt’s team will have to overcome.

The world is too big

Panic Room.

The overriding problem, Koepp says, is that the world is too big for a movie. There are too many story lines a plot might pursue; there are too many ways to structure a scene; there are too many places you might put the camera. You need to filter out nearly everything that might work in order to arrive at what’s necessary.

At the level of the whole film, Koepp prefers to lay down constraints. He likes “bottles,” plots that depend on severely limited time or space or both. The Paper ’s action takes 24 hours; Premium Rush’s action covers three. Stir of Echoes confines its action almost completely to a neighborhood, while Secret Window mostly takes place in a cabin and the area around it. Even those plots based on journeys, like The Trigger Effect and War of the Worlds, develop under the pressure of time.

Panic Room is the most extreme instance of Koepp’s urge for concentration. He wanted to have everything unfold in the house during a single night and show nothing that happened outside. (He even thought about eliminating nearly all dialogue, but gave that up as implausible: surely the home invaders would at least whisper.) As it worked out, the action in the house is bracketed by an opening scene and closing scene, both taking place outdoors, but now he thinks that these throw the confinement of the main section into even sharper relief. The result is a tour de force of interiority—not even flashbacks break us out of the immense gloom of the place—and in the tradition of chamber cinema it gives a vivid sense of the overall layout of the premises.

Panic Room, like Premium Rush, relies on crosscutting to shift us among the characters and compare points of view on the action. But another way to solve the world-is-too-big problem is to restrict us to what only one characters sees, hears, and knows. This is what Polanski does in Rosemary’s Baby, which derives so much of its rising tension from showing only what Rosemary experiences, never the plotting against her. Koepp followed the same strategy in War of the Worlds. Most Armageddon films offer a global panorama and a panoply of characters whose lives are intercut. But Koepp and Spielberg decided to show no destroyed monuments or worldwide panics, not even via TV broadcasts. Instead, we adhere again to the fate of one family, and we’re as much in the dark as Ray Ferrier and his kids are. Even when Ray’s teenage son runs off to join the military assault, we learn his fate only when Ray does.

Less stringent but no less significant is the way the comedy Ghost Town follows misanthropic dentist Bertram Pincus (Ricky Gervais). After a prologue showing the death of the exploitative exec played by Greg Kinnear, we stay pretty much with Pincus, who discovers that he can see all the ghosts haunting New York. Limiting us to what he knows enhances the mystery of why these spirits are hanging around and plaguing him.

Yet sticking to a character’s range of knowledge can create new problems. In Stir of Echoes, Koepp’s decision to stay with the experience of Tom Witzky (Kevin Bacon) meant that the film would give up one of the big attractions of any hypnosis scene—seeing, from the outside, how the patient behaves in the trance. Koepp was happy to avoid this cliché and followed Richard Matheson’s original novel by presenting what the trance felt like from Tom’s viewpoint.

The premise of Secret Window, laid down in Stephen King’s original story, obliged Koepp to stay closely tied to Mort Rainey’s range of knowledge. In his director’s commentary, Koepp points out that this constraint sacrifices some suspense, as during the scene when Mort (Johnny Depp) thinks someone else is sneaking around his cabin. We can know only what he sees, as when he glimpses a slightly moving shoulder in the bathroom mirror.

Having nothing to cut away to, Koepp says, didn’t allow him to build maximum tension. Still, the film does shift away from Mort occasionally, using a little crosscutting during phone conversations and at the climax. During the big revelation, Koepp switches viewpoint as Mort’s wife arrives at the cabin; but this seems necessary to make sure the audience realizes that the denouement is objective and not in Mort’s head.

Once you’ve organized your plot around a restrictive viewpoint, breaking it can be risky. About halfway through Snake Eyes, Koepp’s screenplay shifts our attachment from the slimeball cop Rick Santoro (Nicolas Cage) to his friend Kevin (Gary Sinese). We see Kevin covering up the assassination. In the manner of Vertigo, we’re let in on a scheme that the protagonist isn’t aware of. This runs the risk of dissipating the mystery that pulls the viewer through the plot. Sealing the deal, Snake Eyes then gives us a flashback to the assassination attempt. Not only does this sequence confirm Kevin’s complicity, it turns an earlier flashback, recounted by Kevin to Rick, into a lie. Although lying flashbacks have appeared in other films, Koepp recalls that the preview audience rejected this twist. The lying flashback stayed in the film because the plot’s second half depended on the early revelation of Kevin’s betrayal.

Because the world is too big, you need to ask how to narrow down options for each scene as well as the whole plot. Fiction writers speak of asking, “Whose scene is it?” and advise you to maintain attachment to that character throughout the scene. The same question comes up with cinema.

Say the husband is already in the kitchen when the wife comes in. If you follow the wife from the car, down the corridor, and into the kitchen, we’re with her; we’ll discover that hubby is there when she does. If instead we start by showing hubby taking a Dr. Pepper out of the refrigerator and turning as the wife comes in, it’s his scene. Note that this doesn’t involve any great degree of subjectivity; no POV shot or mental access is required. It’s just that our entry point into the scene comes via our attachment to one character rather than another.

Here’s a moment of such a directorial choice in Stir of Echoes. Maggie comes home to find her husband Tom, driven by demands from their domestic ghost, digging up the back yard. Koepp could have gotten a really nice depth composition by showing us a wide-angle shot of Tom and his son tearing up the yard, with Maggie emerging through the doorway in the background. That way, we would have known about the mess before she did.

Instead, Koepp reveals that Tom’s mind has gone off the rails by showing Maggie coming out onto the back porch and staring. We hear digging sounds. “Oh…kay…” she sighs.

She walks slowly across the yard, passing their son and eventually confronting Tom, who’s so absorbed he doesn’t hear her speak to him.

Once you’ve made a choice, though, other decisions follow. So Maggie provides our pathway into the scene, but how do we present that? Koepp asks on his commentary track:

What do you think? Is it better to do what I did here, which is pull back across the yard and slowly reveal the mess he’s made, or should I have cut to her point of view of the big messy yard right in the doorway? I went for lingering tension rather than the sudden cut to what she sees. You might have done it differently.

Sticking with a central character throughout a scene can have practical benefits too. Koepp points out that his choice for the Stir of Echoes shot was affected by the need to finish as the afternoon light was waning. Similarly, in the forthcoming Jack Ryan, Koepp includes an action scene showing an assault on a helicopter carrying the hero. Koepp’s script keeps us inside the chopper as a door is blown off and Ryan is pinned under it. Rather than including long shots of the attack, it was easier and less costly to composite in partial CGI effects as bits of action glimpsed in the background, all seen from within the chopper.

Saving it, scaling it, buttoning it

Ghost Town.

Because the world is too big, you can put the camera anywhere. Why here rather than there?

Standard practice is to handle the scene with coverage: You film one master shot playing through the entire scene, then you take singles, two-shots, over-the-shoulders, and so on. Actors may speak their lines a dozen times for different camera setups, and the editor always has some shot to cut to. Alternatively, the director may speed up coverage by shooting with many cameras at once. Some of the dialogues in Gladiator were filmed by as many as seven cameras. “I was thinking,” said the cinematographer, “somebody has to be getting something good.”

Koepp opposes both mechanical and shotgun coverage. Whenever he can, he seizes on a chance to handle several pages of dialogue in a single take (a “one-er”). “There’s a great feeling when you find the master and can let it run.” Sustained shots work especially well in comedy because they allow the actors to get into a smooth verbal rhythm. The hilariously cramped three-shot in Ghost Town (shown above) could play out in a one-er because Koepp and Kamps meticulously prepared its rapid-fire dialogue exchange.

When cutting is necessary, Koepp favors building scenes through subtle gradations of scale, saving certain framings for key moments. He walked me through a striking example, a five-minute scene in Panic Room.

Meg Altman and her daughter Sarah have been besieged by home invaders. Meg has managed to flee from their sealed safety room, but Sarah is trapped there and is slipping into a diabetic coma while the two attackers hold her captive. Now two policemen, summoned by Meg’s husband, come calling. The criminals are watching what’s happening on the CC monitor. Meg must drive the cops away without arousing suspicion, or the invaders will let Sarah die.

Koepp’s scene weaves two strands of suspense, the peril of the girl and Meg’s tactics of dealing with the cops. One cop is ready to leave her alone, but another is solicitous. Meg offers various excuses for why her husband called them—she was drunk, she wanted sex—but the concerned cop persists. The scene develops through good old shot/ reverse-shot analytical editing, with variations in scale serving to emphasize certain lines and facial reactions.

At the climax, the concerned officer says that if there’s anything she wants to tell them but cannot say explicitly, she could blink her eyes as a signal. When he asks this, Fincher cuts in to the tightest shot yet on him. The next shot of Meg reveals her decision. She refuses to blink.

Fincher saved his big shot of the cop for the scene’s high point. The cop’s line of dialogue motivates the next shot, one that keeps the audience in suspense about how Meg will respond. What I love about this shot is that everybody in the theatre is watching the same thing: her eyes. Will she blink?

Building up a scene, then, involves holding something back and saving it for when it will be more powerful. An extreme case occurs in Rosemary’s Baby. I asked Koepp about a scene that had long puzzled me. Rosemary and Guy have joined their slightly dotty older neighbors, the Castevets, for drinks and dinner. Having poured them all some sherry, Castavet settles into a chair far from the sofa area, where the other three are seated.

Mr. Castevet continues to talk with them from this chair, still framed in a strikingly distant shot.

Koepp agreed that virtually no director today would film the old man from so far back. Can’t you just see the tight close-up that would hint at something sinister in his demeanor?

We found the justification in the next scene, the dinner. This is filmed with one of those arcing tracks so common today when people gather at a table, but here it has a purpose. The shot’s opening gives us another instance of the Castevets’ social backwardness, as Rosemary saws away at her steak. (You’d think people in league with Satan could afford a better cut of meat.)

Mr. Castevet proceeds to denounce organized religion and to flatter Guy’s stage performance in Luther. As the camera moves on, the fulcrum of the image becomes the old man, now seen head-on from a nearer position.

“He was saving it,” said Koepp. “He was making us wait to see this guy more closely—and even here, he’s postponing a big close-up.”

Yet having given with one hand, Polanski takes away with the other. Next Rosemary is doing the dishes with Mrs. Castevet while the men share cigarettes in the parlor. Because we’re restricted to Rosemary’s range of knowledge, we see what she sees: nothing but wisps of smoke in the doorway.

We’ll later realize that this offscreen conversation between Roman and Guy seals the deal over Rosemary’s first-born.

Empty doorways form a motif in the film (the major instance has been much commented on), and they too point up Polanski’s stinginess—or rather, his economy. He doles his effects out piece by piece, and the result is a mix of mystery and tension that will pay off gradually. Koepp likewise exploits the sustained empty frame, most notably at the end of Ghost Town.

Building up scenes in this way encourages the director to give each shot a coherence and a point. Koepp recalls De Palma’s advice: “For every shot, ask: What value does it yield?” Spielberg comes to the set with clear ideas about the shots he wants, and when scouting or rehearsing he’s trying to assure that the set design, the lighting, and the blocking will let him make them. As Koepp puts it, Spielberg is saying: “This is my shot. If I can’t do X, I don’t have a shot.”

Compared to the swirling choppiness on display in much modern cinema–say, at the moment, Leterrier’s Now You See Me–Koepp’s style is sober and concentrated. For him, the director should strive to turn a shot into a cinematic statement that develops from beginning to end. The slow track rightward in Stir of Echoes has its own little arc, following Maggie leaving the porch, moving past their son, concluding on Tom as she speaks to him and he suddenly turns to her (at the cut).

Accordingly a shot can end with a little bump, a “button” that’s the logical culmination of the action. Something as simple as Rosemary turning her head to look sidewise is a soft bump, impelling the POV shot of the doorway. Something more forceful comes in Stir of Echoes, when the people at the party chatter about hypnosis and the camera slowly coasts in on Tom, gradually eliminating everybody else until in close-up he says cockily, “Do me.”

Shooting all the conversational snippets among various characters would have required lots of coverage, and it was cleaner to keep them offscreen as the camera drew in on Tom. With the suspense raised by the track-in (a move suggested by De Palma), Koepp could treat Tom’s line as a dramatic turning point and the payoff for the shot.

In a comic register, the button can yield a character-based gag. Bertram Pincus is warming to the Egyptologist Gwen; he’s even bought a new shirt to impress her. They discuss how his knowledge of abcessed teeth can help her research into the death of a Pharaoh. A series of gags involves Pincus’ discomfiture around the mummy, with Gwen making him touch and smell it. The two-shot, Koepp says, is still the heart of dialogue cinema, especially in comedy.

Bertram offers Gwen a “sugar-free treat” and shyly turns away. The gesture reveals that he’s forgotten to take the price tag off his shirt.

This buttons up the shot with an image that reveals the characters’ attitudes. Pincus’s error undercuts his self-important explanation of the pharoah’s oral hygiene. Yet it’s a little endearing; he was in such a hurry to make a good impression he forgot to pull the tag. At the same, having Gwen see the tag shows her sudden awareness that Bertram’s offensiveness masks his social awkwardness. As Koepp puts it: “He bought a new shirt for their meeting, she realizes it, and she finds it sweet.” She’s starting to like him, as is suggested when she turns and matches his posture.

Koepp gives the whole scene its button by cutting back to a long shot as Pincus murmurs, “Surprisingly delightful.” Is he referring to his candy, or his growing enjoyment of Gwen’s company? Both, probably: He’s becoming more human.

Like the Movie Brats and the New New Hollywood filmmakers, Koepp is inspired by other films. And as with them, his usage isn’t derivative in a narrow sense. He treats a genre convention, a situation, an earlier Gizmo, or a fondly-remembered shot as a prod to come up with something new. Borrowing from other films isn’t unoriginal; in mainstream filmmaking, originality usually means revising tradition in fresh, personal ways.

There’s a lot more to be learned about screenwriting and directing from the work of David Koepp. He told me much I can’t squeeze in here, about the Manhattan logistics of shooting Premium Rush and about the newsroom ethnography behind The Paper, written with his brother Stephen. What I can say is this: He really should write a book about his craft. I expect that it would be as good-natured as his lopsided grin and quick wit. It would illuminate for us the range of the creative choices available in the New Hollywood, the New New Hollywood, and the Newest Hollywood.

Thanks to David for giving me so much of his time. We initially came into contact when he wrote to me after my blog post on Premium Rush, which now contains a P.S. extracted from his email. We had never met, and I’m glad we finally caught up with each other.

I’ve supplemented my conversation with David with ideas drawn from his DVD commentaries for Stir of Echoes, Secret Window, and Ghost Town. Soderbergh provides intriguing observations on the commentary track for Apartment Zero. I’ve also found useful comments in these published interviews: “David Koepp: Sincerity,” in Patrick McGilligan, ed., Backstory 5: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1990s (University of California Press, 2010), 71-89; Joshua Klein “Writer’s Block, [1999],” at The Onion A.V. Club; Steve Biodrowski, “Stir of Echoes: David Koepp Interviewed [2000]” at Mania; Josh Horowitz, “The Inner View–David Koepp [2004]” at A Site Called Fred; “Interview: David Koepp (War of the Worlds)[2005]” at Chud.com; Ian Freer, “David Koepp on War of the Worlds [2006],” at Empire Online; “Peter N. Chumo III, “Watch the Skies: David Koepp on War of the Worlds,” Creative Screenwriting 12, 3 (May/June 2005), 50-55; E. A. Puck, “So What Do You Do, David Koepp? [2007]” at Mediabistro; Nell Alk, “David Koepp, John Kamps Talk Premium Rush, Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s Fearlessness and Pedestrian ‘Scum’ [2012]” at Movieline; and Fred Topel, “Bike-O-Vision: David Koepp on Premium Rush and Jack Ryan [2012]” at Crave Online.

Vincent Sherman discusses screenplay switching in People Will Talk, ed. John Kobal (Knopf, 1986), 549-550. My quotation from Gladiator‘s DP comes from The Way Hollywood Tells It, p. 159. For more on David Fincher’s way with characters’ eyes, see this entry on The Social Network.

Clocked doing 50 in the Dead Zone

DB here:

August’s final weekend fizzled. Ray Subers of Box Office Mojo writes:

The Expendables 2 repeated in first place on what was easily the lowest-grossing weekend of 2012 so far: the Top 12 added up to $83.8 million, or 12 percent less than the previous low (Feb. 3-5).

This late-summer slot is usually a problem. Here’s Subers on last year’s situation, which included Hurricane Irene.

The weekend as a whole . . . is poised to be one of the slowest of the year, hurricane or no. . . . This crop of new releases [Columbiana, Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark, Our Idiot Brother] is modest at best, though Irene has given Hollywood a convenient excuse.

With few exceptions, both winter and summer have stretches which make it hard for new releases to make headway. January through March and mid-August through September are forbidding Dead Zones. Is it a vicious cycle? Do audiences stay away at these times because most releases have little appeal? Or do the distributors treat these months as dumping grounds because people tend to stay away?

Some years back, I pointed out that often these barren months yield some good, unpretentious fruit. This is the realm ruled by our B films–the action pictures, romcoms, modest dramas, and low-budget fantasy and science fiction that give the theatres minimal reasons to stay open. Often the Dead Zone can yield modest, interesting movies that escape the hyperbole that surrounds bigger productions. My example in 2008 was Cloverfield, which actually made decent money in wintry down times. Last year, there were Lone Scherfig’s One Day, Steven Soderbergh’s Contagion, Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive, and probably others I missed.

I saw only one new release in the 24-26 August window, Premium Rush. It seems to me one of the best mainstream movies I’ve seen this year, and its weak performance ($6 million on the weekend) just shows that you can’t judge by box-office numbers. I found it much more enjoyable as a movie, and more intelligent in its grasp of storytelling and audience uptake, than Marvel’s The Avengers (opening weekend $207 million) and The Dark Knight Rises ($424 million), the two hulks looming over the season.

If Truffaut is right that cinema gives us beautiful people who always find a parking space, Premium Rush is pure cinema. The gallery of characters presents hip youngsters of Benetton gorgeousness (white guy/ African American guy/ Hispanic woman/ Chinese woman/ Indian guy) up against a middle-aged white guy with an ominously overhanging lip that makes him look both stupid and perpetually peeved. Needless to say, Michael Shannon has fun with this. And the couriers always find a place to lock their bikes.

It’s also a real Manhattan movie, which is to say it invokes welcome prototypes: frantic bustle, fast talk, quarrelsome strangers, good cops, bent cops, dumb cops, collisions born of congestion, chance encounters that become significant, violence courtesy of a mafia (Chinese), and moments of casual kindness. We’re all Saroyans when it comes to the Big Apple. We endlessly sentimentalize this city in our movies, and they’re probably the better for it.

But to make a more analytical case that this is a smart, well-put-together movie, I must indulge in spoilers, which are coming right up.

Bike boy

Premium Rush is short: 83 minutes and 49 seconds, not counting credits. That’s also about the length of G-Men, The Ghost Goes West, Holiday, Shopworn Angel, Phantom Lady, The Dark Mirror, Pitfall, The Suspect, Baby Face Nelson, and the 1953 War of the Worlds. I’m not proposing length as a yardstick of value, only noting that our two-hour-plus blockbusters have forgotten what you can do in short compass.

In many B-pictures, both now and then, brevity can encourage you squeeze diverse possibilities out of a simple situation. In Premium Rush, the central situation exemplifies the screenwriter’s old adage: Swamp your protagonist with problems. Here they come fast.

At 5:17 pm, Manhattan bike messenger Wilee is assigned to pick up an envelope from Nima, a Chinese woman who works at Columbia University. He’s immediately pursued by a cop, Robert Monday, who wants what’s in the envelope. At the same time, Wilee and his girlfriend Vanessa, also a messenger, are quarreling because he missed her graduation ceremony. A heavy make is flung Vanessa’s way by Manny, an African American Adonis who’s Wilee’s only rival in virtuoso biking. And at intervals Wilee, who shoots through traffic with suicidal glee, is in the sights of a bulky bike cop. All jammed together we have a free-spirited protagonist who’s quit law school because he loves to ride, a love triangle, a sinister cop, and a mystery: What’s in the envelope? By 7:00 pm all is resolved.

The film displays the classic Hollywood double storyline–romance problems and work problems, intertwined. Still, the plot isn’t as linear as I’ve just implied. I think that the film exemplifies clever ways of working with the four-part structure that Kristin has identified as common in Hollywood features. (That’s discussed here and here and here.) My timings aren’t as exact as I’d like, but I think they’re decent approximations.

Setup (0-ca. 28:00)

After the flash-forward prologue, set at 6:33 pm, and the brief exposition of Wilee’s world view, we see him picking up the envelope at 5:17. It’s addressed to Sister Chen in Chinatown and it must arrive by 7:00.

In a chase Wilee evades Monday and the bike cop, and goes to a police station to file charges against Monday. But he has to take cover when Monday comes in. Now the film’s narration gives us a block of scenes that flashes back to earlier in the day, starting at 3:47. We see Monday lose thousands of dollars in Chinese gambling parlors. Punished by the loan shark’s thugs, he kills one of them. To make amends, he agrees to intercept a ticket that’s worth $50,000 that’s making its way to Chinatown. At the end of the flashback, Wilee, hiding in the police station’s men’s room, opens the envelope and sees that what’s inside is simply a movie stub with a Smiley scrawled on it.

In a chase Wilee evades Monday and the bike cop, and goes to a police station to file charges against Monday. But he has to take cover when Monday comes in. Now the film’s narration gives us a block of scenes that flashes back to earlier in the day, starting at 3:47. We see Monday lose thousands of dollars in Chinese gambling parlors. Punished by the loan shark’s thugs, he kills one of them. To make amends, he agrees to intercept a ticket that’s worth $50,000 that’s making its way to Chinatown. At the end of the flashback, Wilee, hiding in the police station’s men’s room, opens the envelope and sees that what’s inside is simply a movie stub with a Smiley scrawled on it.

Complicating action (ca. 28:00-48:00)

A plot’s second stretch is often a complicating action, something that changes the protagonist’s goals. Originally Wilee wanted to fulfill the delivery; now, with things getting dangerous, he decides not to. He goes back to Columbia to return the envelope to Nima.

At this point we get a flashback explaining that the ticket is a token from a Chinese crime lord, whom Nima has paid with her savings. In the meantime, Monday finds a new stratagem. Instead of trying to catch Wilee, he calls the messenger service and, citing the number on the receipt he has wrested from Nima, he changes the dropoff point. Raj, the dispatcher, gives the order to Manny, Wilee’s rival, and Manny fetches the envelope moments after Wilee has returned it.

We’re at about the midpoint of the film when Nima explains that the money is payment for her son’s illicit passage to America. Now Wilee is faced with a classic choice for an American protagonist: To mind your own business, or to risk your life and livelihood to help someone in distress. He chooses to be a hero, and that means catching up with Manny.

Development (48:00-64:00)

The development section usually doesn’t radically change the premises of the plot. Instead, it’s used to define character further, flesh out secondary aspects of the situation, rework motifs, build suspense, and, surprisingly, simply delay the conclusion. Premium Rush offers a good example of several of these functions. Pedaling frantically after Manny, Wilee phones him and offers him money to give him the envelope. Manny could have accepted, and that would initiate the climax right away.

But Manny is a competitor. We’ve seen that he has his eye on Vanessa and he’s convinced he could beat Wilee in a race. So Manny’s personality, agreeable but aggressive, motivates delay, in the form of a prolonged chase/race that, inevitably, brings in the bike cop yet again. Meanwhile, the fact that Vanessa happens to be Nima’s roommate, and that she first put Monday on Nima’s trail, puts her into the mix, pedaling fast to converge with the three men. When she and Wilee finally meet, he hides the ticket in his bike’s handlebar, creating preconditions for the climax.

But Manny is a competitor. We’ve seen that he has his eye on Vanessa and he’s convinced he could beat Wilee in a race. So Manny’s personality, agreeable but aggressive, motivates delay, in the form of a prolonged chase/race that, inevitably, brings in the bike cop yet again. Meanwhile, the fact that Vanessa happens to be Nima’s roommate, and that she first put Monday on Nima’s trail, puts her into the mix, pedaling fast to converge with the three men. When she and Wilee finally meet, he hides the ticket in his bike’s handlebar, creating preconditions for the climax.

This section builds to a pile-up that ends with what we saw at the film’s beginning: Wilee sailing across the frame and landing on the pavement. Dazed, he remembers meeting Vanessa at a bar, where he won a prize as top messenger–the prize being the bike he’s been riding. Each of the three sections we’ve seen includes a flashback, but this is the first one presented as a character’s memory.

Climax (64:00-83:49)

One sign of a climax is this: We know everything we need to know. We know what the ticket means, what all the characters want, and what the stakes are. Now we just have to watch their plans work. In the ambulance, Wilee is suffering from cracked ribs, and Monday bends over him, whacking the ribs to make him talk. Wilee admits that he’ll tell everything if he can get his bike back. This is the make-or-break moment: The hero has to find a subterfuge that will accomplish his goal. Recovering the bike will allow him to retrieve the ticket.