Archive for the 'Directors: Kore-eda Hirokazu' Category

Venice 2017: Crimes, no misdemeanors

Outrage Coda (2017).

DB here:

The period from 1985-1995 was a sterling era for world cinema. Whatever you think of Hollywood of that time (it wasn’t as bad as they say), American independent film was flourishing then. On the global stage, things were even better, as witness the rising careers of Hou Hsiao-hsien, Edward Yang Dechang, Jackie Chan, Tsui Hark, Abbas Kiarostami, and Wong Kar-wai. It was exhilarating to watch these and other directors turn out splendid work like City of Sadness, A Brighter Summer Day, Police Story, Project A Part II, Peking Opera Blues, Once Upon a Time in China, The Blade, Where Is the Friend’s Home?, Through the Olive Trees, Days of Being Wild, Chungking Express, and more.

That’s not all. In Hong Kong, John Woo was redefining the urban action film with the flamboyant, romantic A Better Tomorrow (1986), The Killer (1989), and Hard-Boiled (1992). In Japan, a standup comedian known as “Beat” Takeshi Kitano took over the helming of a crime thriller, Violent Cop (1989), and decided to continue directing, turning out not only the bored-hitman saga Sonatine (1993) but also the lyrical A Scene at the Sea (1991). Another Japanese filmmaker, Kore-eda Hirokazu, launched his career with the meditative, Hou-ish Maborosi (1995).

I loved these films, and still do. Woo and Kitano belong to an older generation (mine, actually), while Kore-eda is younger. None has gone away. All came to Venice 74 with murder on their minds.

Confessed, but to what?

The Third Murder (2017).

The Third Murder (Sandome no satsujin) is Kore-eda’s first venture into the crime genre, and he brings to it the same steady humanism we find in all his work. I’ve elsewhere recorded my uneasiness with his current visual style. Unlike the grave, long-take Maborosi, his films of the last decade or so are pictorially conventional, even academic, with their big close-ups, needlessly sidling camera moves, and other features of intensified continuity. But he continues to take narrative risks, and his almost Renoirian willingness to see many moral and psychological points of view make every film fairly gripping.

The Third Murder begins abruptly. An unseen victim is bludgeoned and the body is burned. The killer is the man we’ll come to know as Misumi. He’s captured. Like 99% of people charged with crimes in Japan, he readily confesses. His lawyers face only the question of sentencing: Should they try to get him life imprisonment rather than execution? When one attorney, Shigemori, decides to investigate more closely, he peels back layers of uncertainty about the circumstances, the victim, and the motive(s). Like many a victim in crime fiction, this businessman needed killing.

Following conventions of the investigative procedural, the plot relies on secrets, viewpoint shifts that drop hints, twists that frustrate simple understanding, and flashbacks that make us question what we thought we knew. Shooting in anamorphic widescreen, Kore-eda produces some extreme framings reminiscent of Kurosawa’s High and Low, one of the films he studied while preparing the project. Despite occasionally flashy moments, it’s a soberly told tale, emphasizing characterization and social critique. By the end, Misumi acquires a weary, radiant dignity, while entrepreneurial capitalism and the justice system are revealed as compromised. (In this respect it recalls I Just Didn’t Do It, 2007, by another 80s-90s director, Suo Masayuki.) In moving to the sordid terrain of the crime story, The Third Murder shows that Kore-eda hasn’t given up his sympathetic probing of human nature and his praise for un-grandiose self-sacrifice.

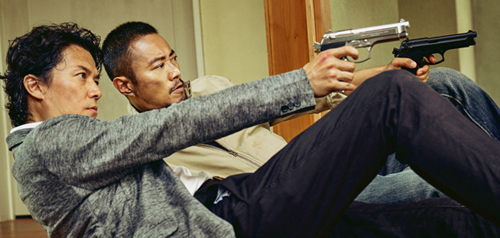

Bullets to the head and elsewhere

Manhunt (2017).

Sober and un-grandiose don’t apply to Manhunt (Zhuibu), John Woo’s return to bloody brotherhood and outsize ordnance. After prestige Hollywood efforts like Windtalkers (2002), the nationalistic costume picture Red Cliff (2008-2009), and the ensemble-disaster movie The Crossing (2014-2015), Woo is back with what he does best: showing many people firing many guns, dodging bullets (bad guys have bad aim), diving for cover in slow-motion, floating through hazes of cordite, and instantly recovering from wounds that would finish off you and me. These characters also run endlessly, hop into the path of trains, overturn vehicles, and set loose unconscionable numbers of pigeons.

1990s Hong Kong directors could make cheap pictures look expensive; given bigger budgets, they made expensive pictures look cheap. Here that cheapness shows most in some video-generated shots that recall the bad old days of edge enhancement. But who has time to study such problems when you’re smacked by a fusillade of 3000-plus shots in 105 minutes? Resistance is futile, and the pace doesn’t relent. When the fights and pursuits pause, the dialogue scenes flash by in a flurry of cuts and unfortunate lapses into English. (Much of the soundtrack recalls the eerily dubbed voices on US videos of The Killer.)

You’ve got no time to worry much about all this after an opening that drops us straight into an ambush. Ultra-cool Du Qiu drifts into a bar and quotes yakuza movies before leaving the hostesses to slaughter the gangsters dining there. It does get your attention, and it encourages you to sit through the exposition showing Du as the trusted lawyer for a corrupt pharmaceutical company. He proceeds to be framed for murder and goes on the run. Meanwhile stalwart detective Yamura, charged with bringing Du in, begins to suspect that there’s a bigger scheme afoot. Of course he is right.

This is all completely preposterous and continually enjoyable, with constantly startling action choreography and an overheated soundtrack that at one point breaks into Turandot. Here those damn pigeons don’t just soar into the sky; thanks to CGI, they flap annoyingly into the middle of fight scenes, spoiling a punch or a gunman’s aim. We have, besides our twinned heroes, one corrupt cop, one psychopathic son, one fairly mad scientist, two expert hitwomen (one played by Woo’s daughter), a fleet of black-suited motorcycle assassins, and two docile women who acquire some non-negligible lethality. In the press conference, Woo emphasized his eagerness to create women warriors, and he hasn’t stinted. There are hallucinatory images of a bloody wedding dress to enhance the feminine mystique.

Manhunt is a kind of palimpsest of Asian action movies. It’s a remake of a 1978 Takakura Ken movie released to great popularity in China during the 1980s. Woo, in Hong Kong, had already succumbed to that actor’s spell. What Alain Delon was to The Killer, Takakura is to this, and the steelly self-possession of Zhang Hanyu gives the film a solemnity amid all the flamboyance.

Woo has turned the Japanese original into a real Hong Kong movie, vintage 1992. It lacks the mournful homoeroticism of his prime-period work; these two men don’t gaze moistly at each other, but fire quips and complaints in the Lethal Weapon manner. (The bonding is strongest between the duo of female killers.) Still, it’s very welcome, with its proudly retro air and fanboy in-jokes. It earns the right to begin with a reference to a Japanese classic and conclude with a wink to A Better Tomorrow, as if that movie were the next link in a grand tradition. “Old movies always end this way,” says one of the survivors of the carnage. I wish more new movies did the same.

Hitmen in cars getting shot

Outrage Coda (2017).

Compared to Woo, Kitano is brutally laconic. In Outrage Coda, except for one Wooish slow-mo massacre, violence is brusque, shocking, and over fast. In a film full of bland pans following yakuza cars here and there, the end of one panning movement bursts into shooting before you realize it’s happening, and it ends just as suddenly. Kitano likes his confrontations, for sure, and sometimes there’s a buildup, but mostly the blood just erupts, punctuating long scenes of gangster intrigue.

Here that intrigue involves three rival gangs, each with bosses capable of remarkable lip contortions: the Hanabishi yakuza family, its once-powerful subsidiary the Sanno group, and a gang of fixers operating in Japan and Korea under the auspices of boss Chang. Add in two cops, one ready to knuckle to corrupt superiors, the other raging against them, and you have the world through which Otomo (Kitano) and his sidekick Ichikawa move. Normal life, as it’s commonly known, has no place here.

The action bristles with schemes, shifting alliances, double-crosses, faked deaths, and power grabs.”Your methods,” remarks one boss to a co-conspirator, “are increasingly more intricate.” Remarkably, after an introduction humiliating the not-so-bright Hanaba during a sexcapade, Otomo isn’t seen that much. Two-thirds of the running time are devoted to the machinations of the gangs and the cops. Otomo and Ichikawa swing into action rather late, their task being to chop through the knots of plot and counterplot.

The opening few minutes spread out the key motifs. A fishing scene displaying Kitano’s characteristic love for boyish pastimes is interrupted by the discovery of a pistol. The credits sequence announces the importance of cars with gorgeous shots of Otomo being driven through neon-lit streets, his ride seen from straight down as lights play over it. Throughout, deals are struck or broken in cars, and one memorable execution makes creative use of a Toyota. Even that banal filler, shots of cars pulling up and disgorging their riders, gets played for variations: distant thunder when bosses arrive for a conference, abstract configurations when rival forces meet on a rooftop.

During the 1990s Kitano was one of those directors working with what I’ve called planimetric staging and compass-point editing. (Wes Anderson, Terence Davies, and others worked the same territory.) Characters face the camera in medium shot, and shots change along the lens axis or at 90 degrees to it. It’s as if we were in between the characters. When I asked Kitano about the technique back then, he claimed that it was his effort at realism, capturing how people faced one another in conversation. He added that he didn’t know how to direct a scene, and this was the easiest way.

I thought that his images’ paper-doll simplicity suggested a naivete suited to Kitano’s childish hitmen. Moreover, this rigorous, geometrical technique takes on special impact when presenting mobster shootouts. Instead of ducking for cover as Woo’s heroes do, Kitano’s stand up and keep blasting, firing straight out at the viewer in tit-for-tate exchanges. His unflinching framing, refusing Woo’s camera arabesques, gives these encounters a ceremonial gravity, turning them into rituals of professional righteousness. Last man standing, indeed.

The face-to-face shootouts in Outrage Coda adhere to this style, and early in the film so do the conversations. Here is Otomo discovering Hanada in his masochistic rig.

But for many dialogue scenes Kitano has gone with more orthodox staging and shooting. We get over-the-shoulder shots for conversation, tight close-ups to emphasize character reactions, and even that commonplace of modern cinematography, the arcing movement around a speaker to pick up a listener in the background. These choices allow Kitano to expose the ripe performances of the two conspiratorial dons Nishino (Nishida Toshiyuki) and Nakata (Shiomi Sansei); their leathery skin, slip-sliding jaws, and shouted outbursts gain a lot from this treatment. Not that I’m really complaining. In a slightly longer film than Manhunt, Kitano gives us around 700 shots, less than a quarter of Woo’s outlay. Each image carries a lot of weight.

Outrage Coda concludes a trilogy, and at the press conference Kitano said that he conceived this and Outrage Beyond (2012) as one continuous phase of the story. He wanted the series to finish. The ending of this installment will fuel much speculation about his next move, and he hinted that he might adapt a forthcoming novel, one that’s a love story. He’s done one before in A Scene at the Sea, and arguably in Kikujiro (1999). His fans, who mobbed him at the panel, are certainly ready for whatever he comes up with.

Thanks as ever to all those at the Venice Film Festival who made our stay so enjoyable. Special thanks to Peter Cowie, Alberto Barbera, Michela Nazzarin, Jasna Zoranovich, and our colleagues at the Biennale College Cinema endeavor.

For more on John Woo’s style of action cinema, see my book Planet Hong Kong. I discuss planimetric staging and compass-point editing in On the History of Film Style and several blog entries, notably the persistently popular Shot-consciousness (which has side notes on Kitano) as well as entries on Wes Anderson.

John Woo and Kitano Takeshi satisfy their fans.

Dragons, tigers, and two programmers

Yellowing (Chan Tze Woon, 2016).

DB here:

It was Asian film that brought me to the Vancouver International Film Festival in 2006, when Tony Rayns asked me to serve on the Dragons and Tigers awards jury. Ever since, Kristin and I have been returning; Tony made VIFF North America’s prime venue for cutting-edge Asian film. Name a major director from the region, and you’ll find that Tony scouted his or her early work for Vancouver.

For some years now, Tony’s co-programmer has been Chinese cinema expert Shelly Kraicer, who has been no less energetic in seeking out exciting new films. You can survey their track record by scanning our VIFF blog entries across the years.

Out of the many films in this year’s D & T retrospective, here are five that I especially admire.

Genres redux

Godspeed.

Across his career, Kore-eda Hirokazu has been a genre pluralist, but in recent years he seems to have settled into the shomin-geki, the bittersweet tale of lower-middle-class life. On the heels of Our Little Sister comes another family dramedy, After the Storm.

Once a prize-winning novelist, Ryota (the lanky, lantern-jawed Abe Hiroshi) is now a racetrack addict and a cheap detective not averse to shaking down high-school kids. After his father dies, and under the jaundiced eyes of his mother, he makes feeble efforts to reunite with his divorced wife and his baseball-playing son.

As usual with Kore-eda, everything flows in simple, unforced fashion, with every shot trimly composed and expertly timed. The emphasis falls on the actors, particularly as they’re captured in mundane activities. Ryota’s mother and sister are first seen writing thank-you notes to people who came to the funeral; he swills in fast food and throws away money on lottery tickets.

Ryota is one of Kore-eda’s most objectionable protagonists. He uses his admittedly minimal surveillance skills to spy on his wife, and he tries to swipe a family scroll to pawn. In an American film, this unlikable loser would pass through an arc that makes him caring, sharing, and on the road to rehab. Instead, as in many Japanese films, the unhappy character relapses into childhood—here, curling up with his son inside a playground octopus during a typhoon. It’s his effort to mimic a bonding moment with his father, but does it succeed now? Kore-eda isn’t betting on it.

Altogether less tranquil is Godspeed, from the Taiwanese director Chung Mong-hung. Chung has given us the horror film Soul (2013), the well-received Fourth Portrait (2010), and the lively Parking (2008), which I reviewed at an earlier VIFF session.

Godspeed is a Tarantinoish excursion into the underworld. It alternates violent scenes of betrayal and reprisals with comic interludes involving a drug courier and the taxi driver he’s hired to carry him to meet the bosses. The film is made with great panache, but for me what makes it noteworthy is that the driver is played by the great Michael Hui, dean of sour Hong Kong social satire.

Hui made his name as a television star before switching to films like The Private Eyes (1976), Security Unlimited (1981), and our favorite, Chicken and Duck Talk (1988). Godspeed revives Hui’s comic persona, the tight-fisted, corner-cutting bargainer who isn’t as clever as he thinks. As Old Xu, he reminisces about Hong Kong traffic and marital woes while trying to wangle a high fare from the phlegmatic, not overbright drug mule. Their misadventures—stumbling into a funeral, being stuffed into a car boot—serve as a counterpoint to the drug war escalating around them. No masterpiece, Godspeed is a beguiling exercise and a welcome return to a legendary and apparently ageless figure of Chinese cinema.

Mysterious, and fun

Another year, another stroll through Hong Sangsoo’s garden of forking paths.

With compositions that are about as banal as they can be, the films don’t aim to dazzle us pictorially. (Nice lighting, though.) The basics are really basic: Straight-on angles, fixed long take two-shots, simple come-and-go pans, an occasional and inexplicable zoom. These are his tools.

Dialogue and performance drive the action, which consists mostly of chance encounters and conversations in cafés, bars, restaurants, and bedrooms. His characters are students, artists, and film directors (usually fairly pretentious ones). Romantic hookups emerge, only to dissolve or play themselves out in parallel worlds, the whole presented in a “stacked” arrangement of modular scenes.

These scenic blocks display an obsessive, almost never mechanical, recourse to split viewpoints, recursive time schemes, mirror inversions, and whimsically varied replays. I’ve argued earlier that these permutations often test our faulty memory for exactly what transpired in a scene many minutes before, but it should be noted that sometimes, as in the last stretch of Oki’s Movie (2010), he’ll set the variations side by side.

Or maybe just side by side in your head. If the auteur theory didn’t exist, it would have to be invented to account for the effect of Yourself and Yours. In any other movie, when a man recognizes a young woman in a café, and she says he’s mistaken her for her twin, we might be inclined to take it as a brush-off. In a Hong movie, the scene makes us think back through all his other plots that have relied on doubling. So maybe this time he’s found a new variation? Has he got an actual pair of twins who will circulate through the scenes, constantly being taken for one another?

Suffice it to say that the young woman (women?), repeatedly encountering three men who are attracted to her (them?), becomes (become?) the pretext for the usual Hong mockery of male vanity and insecurity. The lackadaisical painter Youngsoo is worried about his girlfriend Minjung, who drinks more than he’d like. Moreover, his friend reports that she’s been seen with other men. Quickly enough, we spot her sharing drinks with an older man and a film director—who discover that they are old classmates. “This is mysterious,” the director remarks, “and fun.” None of the would-be Romeos notice that the lady in question is reading Kafka’s The Metamorphosis.

Hong always has another card up his sleeve, and Yourself and Yours, while not as ingenious as his previous entry Right Now, Wrong Then (2015), is satisfyingly teasing. It also yields one of the most flagrantly self-indulgent trailers I know: faithful to the movie, but frustrating in just the right ways.

Taking it to the streets

When college students en masse join a movement for social change, their positions tend to be vindicated in the long run. In the United States, students were right to support movements against nuclear proliferation, against racial discrimination, against American involvement in Vietnam, for women’s liberation and LGBT rights, against the invasion of Iraq, and, right here in Wisconsin, against Republican union-busting and voter suppression. The same pattern can be observed around the world, in student protests in Europe, South America, and Asia. Elders deride students as naïve, but more often than not, student activists critical of the status quo get principled politics right.

Why? I suspect several causes, including the fact that many (not all) students are reading, thinking, and learning while the general populace trudges through the dull compulsion of everyday labor. College flings together students from many backgrounds and may open eyes about how other people live. (Right-wingers worry too much about liberal professors indoctrinating students. In my experience, students are more influenced by their peers than by the likes of me.) And of course the flexible scheduling of college days allows motivated students the time to engage in political action.

Whatever the causes, it’s no surprise that in Hong Kong, the street protests running from September through December of 2014 were launched by young people. In August the mainland’s Communist Party decreed that instead of direct election of the territory’s Chief Executive, candidates would be chosen by a nominating committee comprised of businessmen and politicians sympathetic to Beijing. In effect, this guaranteed a puppet leader of the type all too familiar in the territory. Students responded by organizing actions similar to the Occupy movement in America. With surprising speed, civil disobedience and sit-down occupation spread through downtown areas of Hong Kong Island and the Kowloon Peninsula.

Hong Kongers were long considered indifferent to politics, only concerned with scrambling to get ahead and make money. But the world had to notice when tens of thousands of students and ordinary men and women built vast encampments in the streets in front of chic shops and noodle restaurants. Wearing yellow ribbons and hard-hats, and armed with umbrellas to protect them against sun, rain, and tear gas, they were apparently ready for a long stay.

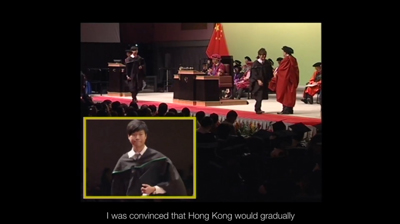

This epochal event in Hong Kong history is documented in Yellowing, a new film by Chan Tse Woon. It was made under the auspices of Ying e chi, a filmmaking collective that has been working since the propitious year 1997, when the British turned the territory over to the People’s Republic. Although framed as a diary, it’s basically a cinéma vérité account of moments and vignettes of the Umbrella Revolution. The voice-over narration is keenly personal, beginning with home-movie footage of Chan’s childhood and youth, interrupted by his memory of repeated promises that democracy would soon arrive.

Loosely organized, Yellowing offers no systematic chronology of events à la a PBS program. It’s defiantly local, a snapshot album for Hong Kongers who will recognize each phase of the movement. At the start, some gorgeous nighttime cityscapes are shattered by confrontations with police (“Police, retreat,” the students chant) and conversations with student organizers in their down time. In the two hours that follow, we spend a lot of that time with young people like the ceaselessly beaming Rachel, who’s now considering becoming a civil rights lawyer. We see one boy passing out wristbands reading, They can’t kill us all.

Students set up tents, squat in pounding rain, organize English classes, and run supply chains across the vast areas of occupation. There are clashes with police and civilians. (“Your flesh and blood belongs to your family,” a man charges.) Chan’s camera captures, helter-skelter, assaults from cops and street gangs. There are camera duels, with police filming demonstrators while demonstrators film police. Chan’s voice-over says that he thought his camera would protect him, but he still gets punched in the face. The occupiers practice tactical evasion and passive resistance, but there’s no effort to heroicize them. Many are crying as police lead them away.

Despite the almost casual presentation, you realize how much these kids are risking. Many are poor, some are trying to hang onto a job, and nearly all realize that this will change their lives. “Even if we lose this fight, we’ll lose together.” As for the angry citizens wearing blue ribbons declaring support for authorities, the students are sympathetic: “Don’t you think they need democracy too?”

The film circles back to the opening, with Daddy-cam shots of children. We hear Rachel writing in reply to a professor who had urged the students to give way for the sake of “security,” and to stop being tools of “foreign subversion.” The film lingers on her cheerful, polite suggestion that Mainland domination has replaced British colonialism, and that the children of the future deserve better.

Most of our politicians and all of our plutocrats will never know the sort of courage that these young people displayed with modest, good-humored tenacity. Unarmed—unlike the Y’all Queda fraidycats who occupied our Oregon wildlife refuge—these unprepossessing kids stood a very good chance of being brutalized by a government not known for recognizing the niceties of due process. You feel proud of the young people of Hong Kong while watching this heartbreaking, hopeful film. As often happens, the students were both righteous and right.

Not hope, fear

Ying e chi has often worked with theatres to show independent films, but Yellowing has been denied a theatrical release. Instead, Variety reports, producer Vincent Chui has arranged for guerrilla screenings. Five ticketed shows were held at the Hong Kong Film Archive, in order to qualify for this year’s Hong Kong Film Awards.

The resistance to Yellowing doubtless owes a lot to the controversy surrounding another film, Ten Years (2015). It won astonishing success in local theatres. According to Maggie Lee in Variety, it cost only US$65,000 but earned nearly $800,000 before Beijing realized how subversive it was and blasted it as a “thought virus.” Ten Years was nominated for a Hong Kong Film Award, which made the PRC cancel television coverage of the ceremony. When the film won the Best Picture prize, shock waves went through the film community, and it was denounced by producers and executives. It was soon cast out of theatres, but screenings continued in community centers, churches, and outdoor venues. It’s slated for a DVD release soon.

Ten Years consists of five shorts linked by the premise of local life in 2025. In its dystopian portrayal of Mainland domination of Hong Kong, it’s a fairly direct outgrowth of the Umbrella Revolution. But if Yellowing documents the movement’s hope, this film exposes, as many commentators have noted, fear.

One episode, “Extras,” dramatizes behind-the-scenes scenes political machinations as a sort of noir comedy. Two hapless thugs are hired to stage an assassination attempt that will arouse public support for a new security law. While the men rehearse their gun choreography, the puppeteers debate whether killing or wounding the targets would play better in the media.

Other episodes are more concerned with the cultural impact of Beijing’s dominance of local life. “Season of the End” presents scientists searching rubble for signs of now-vanished Hong Kong life, shot in ominously clinical detail. “Dialect” presumes that Mandarin is becoming the official language of the territory, and we see a taxi driver struggling to cast off his Cantonese. “Local Egg” also centers on language. Here a shopkeeper is forbidden to use the word “local” because it suggests those political factions struggling to keep Hong Kong distinct, or maybe pushing it to become independent. In an echo of the Cultural Revolution, this episode shows schoolkids in uniform arriving with iPads to check shops’ compliance with the list of forbidden words and retail items.

The most emotionally wrenching episode, “Self-Immolator,” is a pseudo-documentary. Startling scorch-marks on the sidewalk are the traces of someone who burned to death in protest of government oppression. Through talking heads, a collage of demonstration footage, and some investigation, the film traces how a young man’s hunger strike led to the mysterious self-immolation. Several candidates for the self-sacrifice are canvassed before, in a break with the documentary frame, the protest suicide is shown. In the conclusion, an umbrella is seen aflame, perhaps forming a requiem for the 2014 protests.

Ten Years is a good example of how a film can have social importance because of the moment at which it emerges. Along with Yellowing, it will be a lasting memorial to the struggles of Hong Kong people to introduce democracy to China.

Thanks to Tony and Shelly for all their work in setting up these screenings. In addition, Kristin and I are grateful to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, and Jennie Lee Craig and their colleagues for making our VIFF visit so enjoyable and enlightening. Special thanks to Tallulah for cheerfulness and Lillooet for the waffles.

Thanks to our regular attendance at VIFF, we’ve discussed many of Hong Sangsoo’s films; see the director category.

The development of the Umbrella Revolution is traced in this long New York Times story. Last August, accused student leaders got surprisingly light sentences. Some of the “localists” and Occupiers won places in the Legco elections and are expected to make waves.

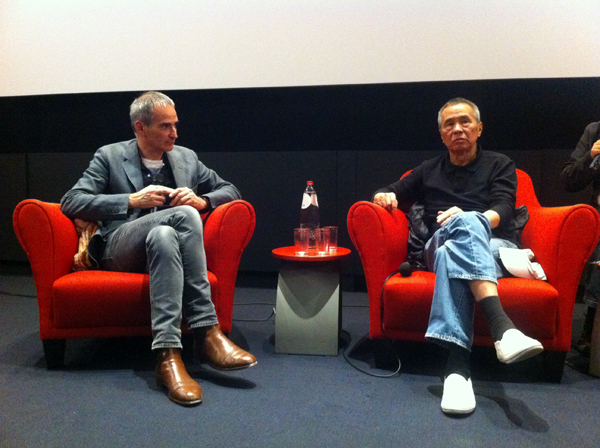

Tony Rayns and Shelly Kraicer.

Hou Hsiao-hsien: A new video lecture!

The Puppetmaster (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1993).

DB here:

The Hou Hsiao-hsien seminar held in Antwerp at the end of May was an event I was sorry to miss. The title announced a focus on Hou’s style of “just-noticeable differences,” a phrase I used to describe his rich and nuanced staging. Coordinator Tom Paulus assembled a stellar lineup of scholars:

Cristina Álvarez López, critic and researcher, co-founder and co-editor of Transit and frequent contributor to mubi.

Adrian Martin, wide-ranging critic and scholar, whose recent book, Mise en scène and Film Style, made him a natural choice for this gathering.

Bérénice Reynaud, expert on Chinese cinema and author of the first book on Hou in English, a fine monograph on City of Sadness.

Richard Suchenski, coordinator of the major Hou retrospective now touring the world and editor of a vast anthology (discussed in an earlier post).

James Udden, author of the first career monograph on Hou in English (discussed hereabouts) and reporter for us on The Assassin (here and here).

A bout of bronchitis kept me home. Chris Fujiwara, author of books on Preminger, Jerry Lewis, and Jacques Tourneur, kindly filled in for me.

But I had prepared a talk, dammit, and I chafed at the prospect of junking it.

The talk was called “The Drawer, Two Women, and the Little Toy Fan.” It centered on aspects of Hou’s 1980s and 1990s work that seemed to me to have influenced works by other filmmakers in the region. The talk ended with some speculations on developments in Hou’s own films over the last fifteen years.

Remembering that all redemption comes from the Web, I decided to put the thing up on our Vimeo channel. While fiddling with it, I realized that it was pretty narrowly addressed to Hou specialists. So I expanded it by offering more context and background, and gave it the unsexy title of “Hou Hsiao-hsien: Constraints, traditions, and trends.”

The lecture is available here on my Vimeo channel.

It can serve as an introduction to some ideas about Hou I floated in Figures Traced in Light. I’ve added comments on Hou films after Flowers of Shanghai, and I consider other filmmakers (Kore-eda, Tsai Ming-liang, Edward Yang) as well. It has pretty pictures, many drawn from 35mm prints.

I regret to report, though, that my voice-over narration, the first I recorded at home rather in a studio, is a bit ragged. And, sorry to say, the talk runs nearly seventy minutes. I take consolation in Adorno’s reply to someone who complained that The Authoritarian Personality was too long: “We didn’t have time to make it short.”

Thanks to Tom Paulus of the University of Antwerp and the Photogénie blog for sponsoring the seminar. Thanks as well to Bart Versteirt and Lisa Colpaert of the Vlaamse Dienst voor Filmcultuur vzw and to Nicola Mazzanti of the Cinematek. And of course I owe big thanks to Erik Gunneson of our department of Communication Arts who, as ever, helped me record and post the video lecture.

See our previous entry for more information about events related to Hou’s visit to Belgium. Our site has other material on Hou here and especially here and here.

Here’s a good place to acknowledge what Abé Markus Nornes and Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh have done in making available their pioneering work on City of Sadness. Long ago they put up a fascinating website on the film, which they have now updated on several platforms. Staging Memories, the free interactive iBook for Mac and iPad, can be downloaded from the Apple Bookstore. You can buy a paperback edition from Michigan Publishing here, and the PDF version of that can be viewed for free here.

In the talk I mention how Hou’s work has affinities for the “tableau” style developed in the 1910s. This isn’t a question of direct influence, but an instance of convergence: Similar early choices in a process (long take, long shot, fixed camera) led to similar options and opportunities further down the line. (A case of path dependence in film style?) You can find more on the tableau style in On the History of Film Style, Figures Traced in Light, and some entries on this site, particularly this one and these. The tableau style is also discussed in another video lecture, “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.”

Olivier Assayas and Hou Hsiao-hsien at the Master Class held at the Royal Film Archive of Belgium. Photo courtesy Nick Nguyen.

VIFF 2013 finale: The Bold and the Beautiful, sometimes together

Gebo and the Shadow (2012).

DB here:

I’m a little late catching up with our viewings at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year (it ended on the 11th), but I did want to signal some of the best things we didn’t squeeze into earlier entries. Kristin and I also want to pay tribute to one of the biggest moving forces behind the event.

Safe but not sorry

Like Father, Like Son (2013).

Among other goals, film festivals aim to provide a safe space for nonconformist filmmaking. Programmers need to find the next new thing—art cinema is as driven by novelty as Hollywood is—and they encourage films that push boundaries. What isn’t so often recognized is that sometimes festivals show filmmakers who were once quite artistically daring backing off a bit from their more radical impulses. Part of this is probably age and maturity; part of it reflects the fact that apart from daring novelties, festivals also showcase works that might cross over to wider audiences. And of course festivals will present recent works by the most distinguished filmmakers, almost regardless of the programmers’ hunches about their quality. Some sectors of the audience want to see the latest Hou or Kiarostami or Assayas.

Koreeda Hirokazu was thirty-three when Mabarosi (1995) won a prize at Venice. It’s an austerely beautiful work, presenting a disquieting family drama in very long, static takes. Once the action shifts to a seacoast village, distant shots render slowly-changing illumination playing over landscapes, while the tension between husband and wife is built out of small gestures. For example, we learn that the forlorn wife is waiting in the bus stop only when a little bit of her comes to light.

Lest this seem just fancy playing around, Koreeda occasionally used his long takes to build suspense. Yumiko’s new husband has been drinking. While he’s out of the room, she opens a drawer to retrieve the bike bell she keeps in memory of her first husband, killed in a traffic accident. The second husband returns unexpectedly, and drunkenly collapses on the table beside her. But when she lifts her hands out of her lap, she inadvertently lets the bell tinkle a little.

The sound rouses him and he asks what she’s holding. She raises her head at last and they begin a quarrel about each one’s motives in marrying the other.

Eventually he will shift woozily to the other side of the table and notice what has been sitting quietly in the frame all along: the still-open drawer on the far right.

In later films, from After Life (1998) to I Wish (2011), Koreeda’s visual design became less reliant on just-noticeable changes within a placid shot. The images have become less demanding, and more extroverted narrative lines carry stronger sentiment. The films remain admirable in their ingenious plotting and mixture of humor and pathos—which is to say, they are committed to that “cinema of quality” that makes movies exportable.

That commitment is firmly in place in Like Father, Like Son. Koreeda, now fifty-one, dares almost nothing stylistically or narratively. Yet every scene leaves a discernible tang of emotion, and his light touch assures that things never lapse into histrionics. If Nobody Knows (2004) and I Wish (2011) are his “children films,” this is, like Still Walking (2008), a movie about being a parent.

The plot has a fairy-tale premise: Babies switched at birth. Our viewpoint is aligned with the well-to-do parents and particularly the ambitious executive Ryota. When he finds that six-year-old Keita isn’t his birth son, he insists on swapping the boy into the household of the happy-go-lucky working-class Saiki family. In exchange, Ryota and his wife take in the boy that Saikis have raised as their own.

As the film proceeds, our view widens to create a welter of comparisons—two ways of being six years old, tough discipline versus easygoing parenting, what rich people take for granted and what poor people can’t, a solicitous mother versus one who can’t spare time for coddling. Koreeda is faultless in measuring the reactions of all involved. Ryota’s wife slips into quiet depression. Saiki is an affable father with a childish streak, but he also looks forward to suing the hospital. Saiki’s wife, a no-nonsense woman with two other kids to care for, is a mixture of toughness and maternal affection. As in a Renoir film, everyone has his reasons, and the drama depends on a process of adjustment stretching across many months. Climaxes become muted, though no less powerful for that.

A smile and a tear: the Shochiku studio formula, enunciated by Kido Shiro back in the 1920s, remains in force here. Simple motifs, such as images stored on a camera’s photo card, hark back to all those affectionate picture-taking scenes in Ozu’s classics. The whole is shot with a conventional polish—coverage through long lenses, straightforward scene dissection—that’s far from the strict, slightly chilly look of Maborosi.

It’s impossible to dislike this warm, meticulously carpentered film. Koreeda has proven himself a master of humanistic filmmaking, and I admire what he’s done (as these entries indicate). Those of us who’ve been following his career for nearly twenty years, however, may feel a little disappointed that he hasn’t tried to stretch his horizons a bit more.

Like Father, Like Son was rewarded with the Jury Prize at this year’s Cannes festival. Steven Spielberg, jury president, has acquired remake rights for DreamWorks.

Action, blunt or besotted

A Touch of Sin (2013).

Jia Zhang-ke’s A Touch of Sin offers a comparable adjustment to broader tastes. It’s far less forbidding than his early features Platform (2000), Unknown Pleasures (2002), and The World (2004). Somewhat like Koreeda, Jia’s earliest fiction films embraced a long-take aesthetic that tended to keep the characters’ situations framed in a broad context. (His documentaries, like the remarkable 2001 In Public, were somewhat different.) Jia proceeded to breach the boundary between documentary and fiction in Still Life (2007), Useless (2007), and 24 City (2008). With A Touch of Sin, Jia takes on a twisting, violent network narrative that is as shocking as Koreeda’s duplex story is ingratiating.

We start with a villager who fumes at the corruption in his town and carries out a vendetta against its rulers. Another story centers on a receptionist who is taken for a prostitute and abused by massage-parlor customers. A third protagonist is an uneducated young man floating among factory jobs who turns his frustration inward. Threading through these is a drifter who shoots muggers from his motorcycle and later takes up purse-snatching.

The sense of inequity and exploitation that ripples through Still Life and 24 City now explodes into rage. Rich men (one played by Jia) puff cigars while strutting through a brothel, businessmen casually exploit their mistresses and buy off politicians, and injustices are settled with fists, knives, pistols and shotguns. “I was motivated by anger,” Jia says. “These are people who feel they have no other option but violence.”

Like Koreeda, Jia has had recourse to some of the casual long-lens coverage we find in many contemporary movies, but certain shots gather weight through his signature long takes–especially shots holding on brooding characters. In all, we get a dread-filled panorama, with bursts of violence staged and filmed with an impact that reminds you how sanitized contemporary action scenes are.

For more, see Manohla Dargis’ rich Times review of the film.

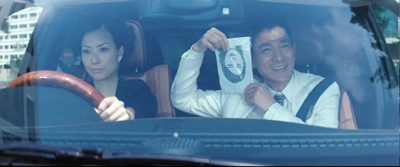

After the painstaking (and pain-giving) dynamics of Drug War (our entry is here), one of Johnnie To Kei-fung’s best recent films, it’s wholly typical that he does something outrageous. His work with Wai Ka-fai at their Milkyway company has always alternated unforgiving crime films of rarefied tenor with sweet and wacko romantic comedies that assure solid returns. But seldom have they combined the two tendencies into something as screechingly peculiar as The Blind Detective.

Initially the investigator, inexplicably named Johnston, seems to be a brother to Bun, the mad detective of To and Wai’s 2007 film. He insists on having the crime reenacted so as to intuit the perp’s identity. But since Johnston is blind, somebody else must tumble down stairs, get whacked on the head, and generally suffer severe pain in the name of the law. Ready to sacrifice herself to Johnston’s mission is officer Ho, a spry and game young woman with a crush on him.

Johnston and Ho are trying to find what happened to a schoolgirl who went missing ten years before. But this account makes the movie seem more linear than it is. Johnston makes his living from reward money, and he’s also dedicated to finding a dancing teacher he fell in love with when he had sight. So the search for Minnie is constantly deflected. Yet the digressions end up, mostly through Johnston’s inexplicable flashes of imagination, carrying them back to their main quest.

This episodic plot, or rather two plots, stretched to 130 minutes (making this the longest Milkyway release, I believe), yields something like a Hong Kong comedy of the 1980s, where slapstick, gore, and non-sequitur scenes are stitched together by the flimsiest of pretexts. The tone careens from farce (not often very funny to Westerners) to grim salaciousness. Johnston’s intuitive leaps are represented by blue-tinted fantasies that show him gliding through a scene at the moment of the murder, or assembling a gaggle of victims to declaim their stories. Characters are ever on the verge of exploding in anger or aggression, and between the big scenes Ho and Johnston dance tangos and gnaw their way through steaks, fish, and other delicacies.

Once more, the congenitally fabulous Andy Lau Tak-wah is accompanied by Sammi Cheng as his love interest, and the two ham it up as gleefully as in Love on a Diet (2001). (They were more subdued in my favorite of the cycle, Needing You…, 1999.) This is, in short, a real Hong Kong popular movie. It brought in US $2.0 million in the territory, and $33 million on the Mainland, about the same as Monsters University. If it keeps Milkyway in business, how can I object?

For a discerning take on The Blind Detective, see Kozo’s review at LoveHKFilm.

JLG in your lap

Kristin and I were keenly looking forward to 3 x 3D, the portmanteau film collecting stereoscopic shorts by Peter Greenaway, Edgar Pêra, and Jean-Luc Godard. Kristin found the Greenaway episode–sort of his version of Russian Ark, taking the camera through the labyrinth of a ducal palace and showing off elaborate digital effects–fairly appealing. But for us the Godard was the main attraction, and he didn’t disappoint.

At one level, The Three Disasters reverts to his characteristic collage of found footage, film stills, scrawled overwriting, and insistent voice-over. (Is it my imagination or does the the 83-year-old filmmaker’s croak sound increasingly like that of Alpha 60?) The montage is sometimes over-explicit, as when Charlie Chaplin is juxtaposed with Hitler. There’s a funny passage of portraits of one-eyed directors (Lang, Ford, Ray), as if to reassert the primacy of classical monocular cinema. At other points, things get obscure, as when Eisenstein’s plea for Jewish causes during World War II is followed by shots from The Lady from Shanghai. But this is the Godard of Histoire(s) du cinema, piling up impressions that beg for acolytes to identify the images and find associations among them.

Frankly, this side of Godard doesn’t grab me as much as his pseudo-, quasi-, more-or-less-narrative features. But in 3D his dispersive poetic musings take on a new vitality. He doesn’t retrofit old movie clips and still photos for 3D. Instead he superimposes them, making one cloudy plane drift over another. He can also, more forcefully, present his signature numerals and intertitles in a new way–by having them pound out of the screen and hang rigidly in front of the image.

There are also some 3D shots made specifically for the film, most consisting of handheld shots that shift around a park, a medical complex, and, of course, a media studio. The very title of Godard’s film, punning on 3D as a technical disaster, as well as a throw of the dice (dés), suggests his ambivalence toward the technology. “The digital,” his voice declares, “will be a dictatorship,” but perhaps it will never abolish chance.

As usual, Godard has fun with simple equipment. He frankly shows us his camera rig, two Canon DSLRs lashed together side by side, one upside down. By shooting them in a mirror and shifting focus, he manages to make each lens pop and recede disconcertingly, as if Escher had gone 3D. This shot alone should inspire DIY filmmakers everywhere. So too should the one-slate credits. Whereas Greenaway’s segment lists scores of names in its credit roll, Godard’s lists only four, alphabetically. I can’t wait for the feature, Farewell to Language. (Trailer here.)

Brian Clark has an informative review of The Three Disasters at twitchfilm.

Looking at the fourth wall

In nineteenth-century Portugal, the elderly Gebo ekes out a living as a company accountant. His wife Doroteia and his daughter-in-law Sofia wait with him for the return of João, a rebellious ne’er-do-well. Gebo feeds Doroteia’s illusions about their son, who has likely become an outlaw. When João returns after eight years away, he throws the family into turmoil and becomes fixated on the cash that his father safeguards for the firm.

After World War II, André Bazin noticed that many filmmakers were starting to take a creative approach to adapting plays. Olivier’s Henry IV, Welles’ Macbeth and Othello, Dreyer’s Day of Wrath, Cocteau’s Les Parents terribles, Melville’s Les Enfants terribles, Hitchcock’s Rope, and Wyler’s Little Foxes and Detective Story, are far from the “photographed theatre” that some critics feared would dominate talking pictures. For decades Manoel de Oliveira has explored avenues of theatrical adaptation that have led us to some daring destinations. Gebo and the Shadow, drawn from a 1923 play by the Portuguese Raúl Brandão, is a powerful recent example, and possibly the best film I saw at VIFF this year.

After the credits show João loitering on the docks, the film confines the action almost wholly to the parlor of Gebo’s family home. Early on we see the street outside through a window, but most of the film concentrates on the characters gathered around the room’s central table. On stage, we can imagine the table at the center and the major characters assembling around it but leaving one side clear, facing the audience–in effect, accepting the convention of the invisible fourth wall that gives us access to the space.

As the still above suggests, it seems initially that Oliveira is playing up this convention, putting us into the stage space and setting the fourth wall behind us. Very soon, though, we’re inserted between the players, so that we see the other side of this lantern-lit playing space.

For the most part, the first stretch of conversations and soliloquys among Gebo, Doroteia, and Sofia are played out in this planimetric, clothesline layout. So is the late-night arrival of the vagrant João, coming to sit opposite his father and laughing wildly. This shot corresponds to the end of the play’s first act.

On the next day, when Gebo and his family receive some friends, the table is sliced in half.

The effect is to redouble the sense of proscenium space, presenting two planimetric arrays that always keep one “behind” us.

Like other chamber-plays-on-film (Dreyer’s Master of the House, Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder), Gebo varies its spatial premises slightly to incorporate other possibilities. In the stretch corresponding to the second act of the play, the angle on the table changes twice, once to present the split table-scene above, and later, to the climactic moment when João joins Sofia and contemplates breaking open the strongbox.

Sometimes we’re shown the window and other walls, usually presented when characters leave one shot and enter another. The constructive editing helps us tie together zones of the room that aren’t ever given in an all-encompassing master shot. And the camera never moves, not even to reframe characters’ gestures.

In previous films, Oliveira has played with the ambiguities of who’s looking where. (See, for instance, Eccentricities of a Blonde-Hair Girl and The Strange Case of Angelica.) After a mysterious prologue involving João, a ravishing image presents Sofia watching at the window, then moving aside to reveal Doroteia behind her (and behind us).

As often happens, the start of a film sets up an internal norm; it teaches us how to watch it. This movie starts with a lesson in optical geometry. Sofia watches the street, goes out to scan for Gebo’s arrival, then watches Doroteia from outside the window before coming back in and resuming her position at the window. As the shot develops, we can see Doroteia lighting a lamp and reflected in the window against the distant doorway.

When Sofia walks out of the shot, Oliveira’s camera lingers on the window, in which we can still see Doroteia turning her head to watch Sofia’s coming to her. This is the shot, imperfectly reproduced, that’s at the top of today’s entry. The image isn’t far from the gently insistent changes of Koreeda’s Maborosi. This film about a shadow starts with an image of a spectre.

Constructive editing often relies on a glance offscreen, so here he can play with minute differences of eye direction. Occasionally the actors look directly out at us. But when the table is halved, as above, the eyelines get very oblique, with opposite characters looking in the same direction.

In the third act, the frontal and planimetric grouping around the table returns. Gebo has searched fruitlessly for João and has returned to take the consequences of his son’s theft.

Oliveira’s adaptation omits the play’s fourth act, when the family is reunited three years later. His version leaves the family suspended in a freeze-frame, haunted by the ghostly son who has betrayed their trust. This dramatic climax is also a visual one, with sunlight for the first time spilling into the chilly, lamplit parlor and its inhabitants startled, as if they shared João’s guilt.

Perhaps more than the other films in this entry, Jebo and the Shadow shows why we need film festivals. Oliveira’s purified experiment demands a lot from the audience, but it repays our efforts. It’s at once an engrossing story and an exciting exercise in what cinema can still do. Note as well that I have managed to get through a discussion of Oliveira’s film without mentioning his age.

For more on the film, see Francisco Ferreira’s very helpful essay in Cinema Scope.

Finally, Alan Franey has announced his departure from the job of Director of the Vancouver International Film Festival. He’s going out on a high note. This year’s edition was a solid success, and its spread to venues around town seems to have brought a wider audience. For twenty-six years Alan has led the process of making the festival one of the best in North America. He has helped give it a unique identity as home to Canadian cinema, documentaries on the arts and the environment, and outstanding current Asian cinema.

Finally, Alan Franey has announced his departure from the job of Director of the Vancouver International Film Festival. He’s going out on a high note. This year’s edition was a solid success, and its spread to venues around town seems to have brought a wider audience. For twenty-six years Alan has led the process of making the festival one of the best in North America. He has helped give it a unique identity as home to Canadian cinema, documentaries on the arts and the environment, and outstanding current Asian cinema.

For Kristin and me, he has been a wonderful friend and good-humored company. Alan’s deep commitment to great cinema has shown in his recruitment of colleagues, his skilful defusing of potential crises (most recently the shift to digital projection), and his genial, almost Zen, good nature. Fortunately for the festival, he will remain as a programmer. He deserves our lasting thanks.

Good news for US audiences on some of these titles: Sundance Selects will distribute Like Father, Like Son, while Kino Lorber has wisely acquired rights for A Touch of Sin. Gebo and the Shadow is available on an English-subtitled DVD from Fnac and Amazon.fr. It’s a very dark movie, and in order to make the frames readable here, I’ve had to brighten them a bit. These images don’t do justice to what I saw in the VIFF screening, or even to what the fairly decent DVD looks like.

For more on planimetric staging of the sort we find in Gebo and Maborosi, see entries here and here and here. It’s a common resource of modern cinema, and directors utilize it in a variety of ways.

Les trois désastres (2013).