Archive for the 'Directors: Lang' Category

Mmm, M good

DB here, boasting about Kristin:

Our series on the Criterion Channel on FilmStruck continues with this month’s entry, Kristin on M as an exceptionally rich sound film. She talks about how Lang adapted silent-film techniques to the demands of sound while also using sound to achieve effects that couldn’t be achieved purely through images.

Watching her discussion and the clips, I was reminded of what a precise director Lang was–a unique mixture of stylistic flamboyance and swift economy. You see that mix in silent masterpieces like the Mabuse films, Metropolis, The Niebelungen, and Spione. In various entries (here and here and here) I’ve dwelt on his poised, meticulous compositions that use the entire frame area. Sound gave him a new set of resources for dynamic expression. Rather than becoming more conventional, Lang’s American films seem to subtly absorb the discoveries of M. Examples are the tapping of the “blind” man’s cane in Ministry of Fear and the ominously croaking frogs in You Only Live Once. And the propulsive sound cuts in his last film, The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse, show that he never forgot that sound could be edited as freely as images.

You can sample a clip from the episode at On the Channel at Criterion’s site. A complete list of the Observations on Film Art series (eleven already!) is here. Go here for blog entries offering background on those installments.

Thanks as ever to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and all their teammates at Criterion.

In pursuit of THE CHASE

The Chase (1946).

DB here:

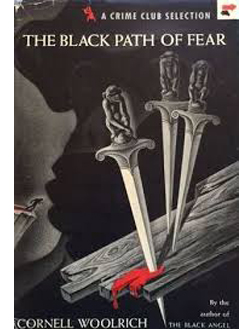

While writing my book on Forties Hollywood, I often felt that every movie I talked about was based on a bestseller, a Broadway play, or something by Cornell Woolrich. Many of the best, or at least strangest, films of the era come from his haunted imagination.

T he Chase (1946), long a cult film maudit, is for some aficionados the ultimate noir. It manages to be even more peculiar than its source novel, Woolrich’s The Black Path of Fear (1944). Although I began reading Woolrich as a teenager, I didn’t catch up with the film until the 2000s, in a so-so DVD. It has come to occupy a minor place of honor in the book (due out next fall, thanks for asking).

he Chase (1946), long a cult film maudit, is for some aficionados the ultimate noir. It manages to be even more peculiar than its source novel, Woolrich’s The Black Path of Fear (1944). Although I began reading Woolrich as a teenager, I didn’t catch up with the film until the 2000s, in a so-so DVD. It has come to occupy a minor place of honor in the book (due out next fall, thanks for asking).

Kino Lorber has recently released The Chase in a nicely cleaned-up DVD/Blu-ray edition. So all hail UCLA’s efforts restoring this neglected item, as well as its rescue of other worthy titles: Renoir’s The Southerner (1945, also from Kino Lorber), Too Late for Tears (1949), and Woman on the Run (1950), the last two from the estimable Flicker Alley. Kino Lorber has decorated the Chase release with commentary by Guy Maddin and recordings of two radio shows based on the Woolrich novel. (A pity we don’t have the Hedda Hopper radio show promoting the film, but maybe that’s lost.)

My book features The Chase because it poses with extreme prejudice the question of how far narrative innovation could go in the 1940s. Sometimes, as I’ve argued with The Great Moment and All about Eve, filmmakers go too far and get pulled back. But then readjustments necessary in postproduction may create twitches of novelty too. The Chase is another example of innovation by accident.

In the book, I mostly analyze the film. But I’ve also done a little digging into its production and promotion, as a way of explaining some of its captivating oddities. I came up with some information I haven’t seen discussed anywhere, so I thought I’d pass it along in a blog entry.

I haven’t located any scripts, alas, but our archive at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research holds other intriguing documents, including correspondence, a typescript synopsis, and a gorgeous presskit. Elsewhere I came across a document that gives clues about what the script and, at one stage, the film were like. There are reasons to think that an early version of the film was even stranger than the finished movie.

There must be spoilers, for both The Chase and The Woman in the Window (1944). Oddly enough, as we’ll see, contemporary reviewers of these movies didn’t worry about spoilers, so maybe I shouldn’t either.

Die in Havana, wake up in Miami

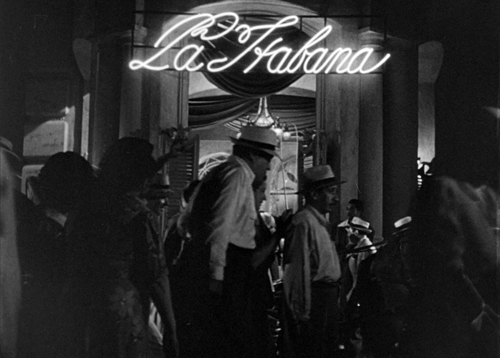

The Black Path of Fear begins in a fraught situation. Bill Scott enters a Havana club with an American woman. As they kiss, she is suddenly stabbed to death, and he’s the prime suspect. He escapes from police questioning and takes refuge in the tenement apartment of another woman, nicknamed Midnight. Scott recounts his backstory in a brief flashback, and then he sets out to find the people who have killed his woman and framed him. His effort takes him into the opium racket run by Eddie Roman from Miami. The bulk of the action takes place in Havana, with the flashback and a penultimate episode set in Miami.

The Chase shifts the book’s flashback material to its chronological place. The film begins with navy veteran Chuck Scott down on his luck. He finds a wallet belonging to crooked businessman Eddie Roman, returns it, and for his honesty is rewarded with the job of a chauffeur. He meets Eddie’s wife Lorna, and soon they are plotting to run away to Havana.

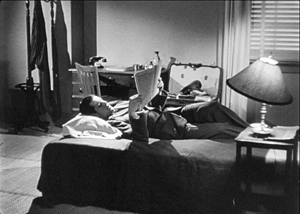

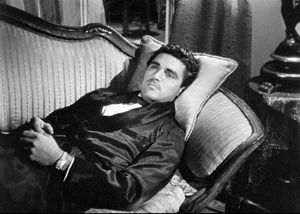

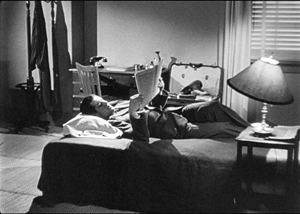

That’s when things get strange. On the night of the couple’s planned escape, Scott stretches out to read a newspaper. Fade out and up to Eddie, also stretched out, listening to a phonograph record–first in extreme long shot, then in mid-shot.

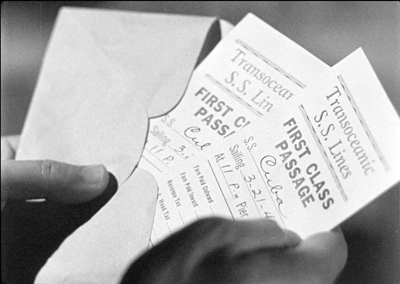

Eddie’s assistant Gino comes to Scott’s room and finds him gone. He reports to Eddie, showing the telltale travel folder.

As the recorded music continues, we are taken to a ship, where in a stateroom Scott is playing the same tune on a piano. Lorna is with him and they are evidently on their way to freedom.

Once the lovers are in Havana, The Chase follows the original novel, up to a point. Lorna is stabbed to death in the bar, Scott becomes the main suspect, and he flees the police by hiding in Midnight’s apartment. Soon Scott discovers that Gino is in Havana. He has arranged Lorna’s murder and the frame-up of Scott.

But now comes an astonishing twist, not in the novel. Gino finds Chuck hiding behind a curtain, shoots him, and dumps his body down a trap door. The body lies lifeless on the stair.

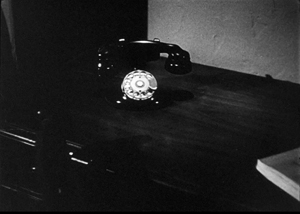

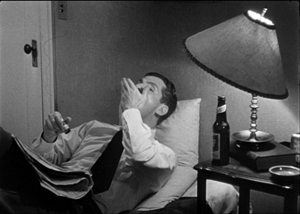

This is plotting in extremis. An hour into the film, both heroine and hero have evidently been killed and the unsavory characters have won. How to get out of this impasse? A telephone in the cellar rings. Cut to a ringing telephone on a desk, and track back. Chuck Scott is waking up, still on his bed with his newspaper.

He has dreamed the entire thirty-minute escape to Cuba, and we weren’t told he had fallen asleep.

This is the sort of twist modern filmmakers don’t advertise in advance, and indeed online accounts of the Kino Lorber disc, such as the shrewd review by Glenn Erickson, have been admirably discreet about it. Yet contemporary reviews openly revealed the device. Six out of seven trade-paper reviews I’ve found announce the dream twist. Daily Variety claimed that this “wild and disordered narrative” consumes “more than half the picture” (no) and “throws audience for a loss” (yes). Motion Picture Herald was less condemnatory—“the whole tangle untangles in a satisfactory manner”—but somehow found that Scott “has been dreaming a dream inside of a dream.”

Critics in the general press were likewise unafraid of spoilers. Life was a bit coy: “Its highly improbable plot has the eerie sensation of a bad dream.” The New York Times was more explicit: “All the foregoing horrors, however, are only a nightmare of Cummings’ ailing brain.” Of the violence, the Los Angeles Times noted, “Most. . . occurs in a dream sequence, which proves puzzling at first….” So perhaps some audiences, primed by reviews, were actually waiting for the twist. The film’s presskit does include suggestions for dream stunts exhibitors might try.

In any case, the dream has taken its toll on Chuck. Now he has amnesia, which spread among 40s movie heroes like a plague. Forgetting his promise to help Lorna escape, forgetting even how he got the chauffeur job with Eddie, he returns to his navy doctor for help. “It’s happened again,” Scott tells him. Dr. Davidson says he has “anxiety neurosis,” dismisses the Havana material as “dream-stuff,” and reassures him that he’s getting better. But from the spectator’s standpoint, the entire plot is put on hold.

The climax carries coincidence to new heights. Dr. Davidson takes Scott to a restaurant for a drink. Pieces of Chuck’s memory return, chiefly the name Lorna. At that moment Eddie and Gino stroll into the restaurant, having locked up Lorna at home. As Davidson chats with Eddie, Chuck finds the tickets to Havana in his pocket and remembers more. Rushing to Eddie’s mansion, he frees Lorna and takes her to the ship. Eddie learns of their plan and races to get to the pier, but en route his car is struck by a train.

Unlike Woolrich’s novel, The Chase takes place almost wholly in Miami, with the Havana dream as an interlude. The epilogue returns to the Havana nightclub and Chuck and Lorna in a carriage at the curb. As they embrace, Chuck says, “We’ll be together forever.”

There doesn’t seem to be any beginning

The Chase, released 22 November 1946, followed a series of and-then-I-woke-up pictures: The Woman in the Window (1944), The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry (1945), and Strange Impersonation (March 1946). All of these thrillers depend on a double bluff. They seamlessly move from waking life to a dream scenario without tipping us off. They return to real life in a symmetrical fashion, while letting us observe how we were misled.

Hooks are very helpful here. For example, in The Woman in the Window, Professor Wanley asks a club servant to remind him when it’s 10:30. He settles down to read. Dissolve to the clock chiming 10:30.

Wanley is still reading when the servant’s voice from offscreen tells him the time. The camera pulls back as the servant enters the frame.

The transition is imperceptible. At the climax of the dream, when Wanley has sought to commit suicide with an overdose of sleeping powder, we get a parallel situation: He’s seated in a chair at home, and the camera tracks in. He seems to die, as the lighting changes.

But the servant’s hand comes in to shake him, he awakes, and we hear the club clock chiming 10:30. The camera tracks back, and the glass in Wanley’s hand in the dream has become the sherry glass he held in the framing scene.

Like its predecessors, The Chase doesn’t signal its dream transition. No whirling superimpositions lead into it, no outlandish compositions announce that we’re in the middle of it. (For comparison, see Stranger on the Third Floor, 1940.) As in The Woman in the Window, the shift is cunningly concealed. Here offscreen music on Eddie Roman’s phonograph is continued as an auditory hook into the start of the dream.

In retrospect, we might argue that the Havana episode hints at its subjective status. Chuck yawns slightly as he’s reading his newspaper, though I don’t think most viewers take that as a dream cue. The concerto music, issuing from a phonograph in Eddie’s living room, is, implausibly, picked up by Scott, who plays the tune on board the ship. The light falling on Lorna and Scott in their cabin is markedly unrealistic, with a shadow dropping and rising on the porthole.

Scott tells Lorna to “Forget time,” and the song to which the couple dance in the club contains the line, “Like the stars in a dream song.” And when Dr. Davidson asks how it all began, Scott replies: “There doesn’t seem to be any beginning”—as if acknowledging the surreptitious segue into his imaginings. The Chase wouldn’t be the first 1940s film to flaunt its own artifice.

The Chase revises the dream schema in a couple of intriguing ways. For one thing, The Woman in the Window and Strange Impersonation make the dream the bulk of the film; the lead-in and lead-out are fairly perfunctory. Many other films make the dream a brief one, enclosed within long stretches of real-life action. The Chase gives us something midway between, a thirty-minute dream that functions as a block almost exactly equal to the chunk of real-world action that precedes it. We have to trace our steps backward to an earlier point of departure and then reckon how new action connects to it. Something similar happens with Uncle Harry, but there the dream comes so late as to supply the film’s climax.

Moreover, in the other films, the dream doesn’t actually alter the real-world situation that gave birth to it. Here, though, the dream has a causal function: It triggers the recurrence of Chuck’s amnesia.

The Chase goes a little farther than its predecessors in another way, The other films in the cycle keep the visual narration attached to the dreamer before and after the transition; that is, the dream’s first scene shows us the dreamer continuing to act. Both Woman in the Window transitions keep us fastened on Wanley. But the first scenes in Scott’s dream feature not Scott but Eddie and Gino. We accept this shift of attachment partly because from the start the film’s narration has been fairly unrestricted, crosscutting between Scott and Eddie. Early in the dream, this departure from Scott’s range of knowledge seems to confirm the objectivity of what follows.

Scott, it turns out, can dream what the bad guys are doing, and because of this we can get a moment of even sneakier duplicity. Within the dream, Gino finds Chuck gone. The beer bottle and discarded newspaper help reaffirm the reality of the scene because an earlier scene of Scott rising included the same props: the beer bottle on the nightstand, and a newspaper in Chuck’s lap.

With the turn to the amnesia device, things become no less dislocated. After Scott visits Dr. Davidson, he becomes surprisingly telepathic. When Eddie learns that Lorna wants to leave, he beats her and locks her in. Dissolve from her sobbing on the floor to Chuck at the bar, staring into space and remembering her name.

Immediately after we’ve seen Eddie’s car smashed by the train, Scott is waiting with Lorna in a stateroom that recalls the dream flight. He’s seized by a calm confidence, as if he intuited their salvation. “It doesn’t matter now.” From that we segue to the two kissing in the carriage outside the Havana club.

For all its attractiveness, Scott’s Cuban adventure doesn’t resolve the main plot. It postpones the Miami action by motivating his new bout of amnesia. Once Chuck loses his memory and flees Eddie’s house, the couple’s planned escape is scotched and the film has to start over by introducing a new character, the therapist Dr. Davidson, and relying on massive coincidence to bring Eddie and Gino back into the action. Perhaps this is why trade critics complained that the last stretch of the film was clumsy.

The case of the missing flashback

So far, so weird. But I think that an earlier state of The Chase was even weirder.

First, some background. Judging by the press coverage, it seems that the figure of authority on the film was the producer Seymour Nebenzal (below). He was a venerable figure, having produced many German classics—M (1931), The Threepenny Opera (1931), The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933)—before fleeing the Nazis. He spent some years in France, producing among other films Mayerling (1936) and Ophuls’ Roman de Werther (1938). Emigrating to the US, he continued to work as an independent producer, with such films as We Who Are Young (1942), Prisoner of Japan (1942), and the Sirk films Hitler’s Madman (1943) and Summer Storm (1944).

Screenwriter Philip Yordan had bought the rights to Maritta Wolff’s 1941 novel Whistle Stop, prepared a screen adaptation, and sold the whole package to Nebenzal. Nebenzal had just reconstituted his Weimar company Nero Film, and Whistle Stop (January 1946) was its first release. Yordan applied the same packaging strategy to The Black Path of Fear. He bought the rights to Woolrich’s novel, then sold them and his adaptation to Nero. Director Arthur Ripley became involved after halting work on his adaptation of Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel.

Yordan was said to have had a financial interest in the film, and apparently Nebenzal promised him the credit “Philip Yordan’s The Chase,” which didn’t come to pass. Most of the publicity spotlighted Nebenzal, who was credited with many of the creative decisions.

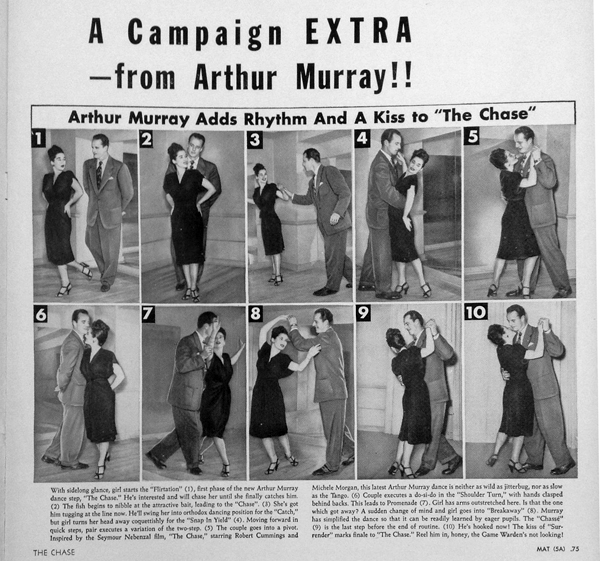

The Chase was not a low-budget project. It was promoted and distributed as an A picture. Boxoffice, the exhibitors’ trade paper, called it a “grade-A gripper, aimed at class houses.” The presskit reveals a tie-in with the Arthur Murray dance studios, which would teach patrons a new step, “The Chase.” (See at very bottom.) At worst the picture might function as a “nervous A” because of the relatively second-tier status of its stars (though Robert Cummings had profit participation in the project).

The production budget, according to an October 1947 financial statement in the WCFTR Collection, was $898,300.60. That doesn’t include debt service of about $40,000. In public statements, Nebenzal claimed that he boosted the film’s budget to $1.2 million. In all, these figures are in line with a mid-range A picture for the period; the average negative cost for all feature films in 1946 was $665,863 (in an era with a lot of B’s at $300,000 or less).

As befits its budget, The Chase contains solid miniature work and big sets, like Eddie Roman’s mansion and the Habana Club. Reviews praised its high production values, achieved by shooting at the Goldwyn studio. There are a couple of impressive crane shots, and Daily Variety reported that three camera booms were used on some scenes. There was time for finicky reshoots during and after principal photography.

In the course of production, Nebenzal issued a stream of press releases. The most important for our purposes appeared in Daily Variety of 16 September 1946.

Producer Seymour Nebenzel, believing market is glutted with flashback pictures, has ordered film editor Edward Marin to eliminate flashback sequence in Robert Cummings starrer, “The Chase.” Script was written so action could start from scratch, instead of starting with chase and then flashing back to start of action, as is done in the Cornell Woolrich novel.

Huh? What flashback?

When I found this item some years ago, I thought: Of course. The novel has a flashback to Miami, and the film moved it up to be part of the opening Setup. But then I realized: The flashback to Miami would have made sense only if the bulk of the film’s action were in Havana. But the film as we have it curtails the novel’s Havana action—most drastically, by killing off the protagonist. Was it possible there was a whole alternative film in which Scott survived and tracked down Roman’s opium-smuggling ring, as in the book? Was all that footage shot but jettisoned?

More likely, the bulk of the action was always going to take place in Miami. (The chase is a relatively small part of The Chase.) For one thing, Jack Holt was signed to play Davidson in early July. Davidson is the catalyst for the action leading to the climax, so once Holt was aboard, the final stretch of the film seems locked to Miami.

So maybe Nebenzal’s remark about taking the “flashback” out was just loose talk. He did display a general pattern of shilly-shallying. He publicly pondered, for instance, whether Lorna should live or die. He claimed to have requested two versions of the script: one in which Lorna remains dead at the end (as in the novel) and one in which she isn’t really dead (to be managed somehow). He said he’d leave it to preview audiences to decide.

This seemed to me a big tease. Nebenzal originally wanted Joan Leslie for the part and pursued her intently before discovering that she was unobtainable. Michèle Morgan, though a minor figure in the States, was a star in France; she won an acting prize at Cannes shortly before The Chase was released. By the fall Nebenzal sought to sign her to a longer-term contract. Keeping Lorna alive for more screen time, as happens in the film’s final Miami section, would be a good buildup for Morgan. In an April press release, Nebenzal had already seemed inclined toward letting Lorna live.

“After all,” he reasoned, “people want to be relieved of their daily troubles when they go to the movies. They don’t want to see their favorite actor or actress killed off.”

By September, Lorna definitely survived. Another press release:

Seymour Nebenzal shot 3 endings for “The Chase,” showing Robert Cummings and Michèle Morgan fleeing by land and sea. One ending had them scramming aboard ship, another on a train, the third on a bus. So far the bus flight is favored.

The shipboard option was chosen, obviously, but the mention of alternative escape vehicles entails that by early September, Lorna was intended to survive one way or another.

All this on-again, off-again made me disregard the item about “eliminating the flashback” as guff or misreporting. That was a mistake.

The film beneath the film

Then as now, one way to promote a new Hollywood release was to publish a novelization: not the original book that the film was based on, but a new literary text derived from the film. As I write this, Alexander Freed’s novelization of Rogue One: A Star Wars Story is available for preorder. Then as now, the novelization would be timed to arrive when the film was released.

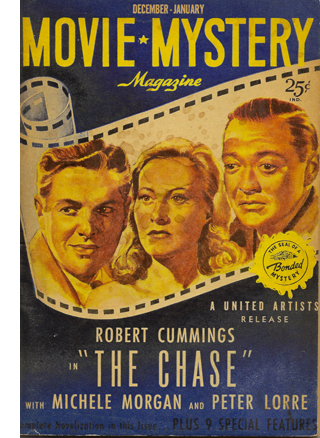

In late June Nebenzal told United Artists officials that he had arranged for a “fictionization” of The Chase, to be published in Movie Mystery Magazine. That periodical’s inaugural issue, dated December-January 1946, did appear on newsstands in November, during the film’s release.

In late June Nebenzal told United Artists officials that he had arranged for a “fictionization” of The Chase, to be published in Movie Mystery Magazine. That periodical’s inaugural issue, dated December-January 1946, did appear on newsstands in November, during the film’s release.

Novelizations, then as now, were typically prepared not from the finished film but from a script or treatment. And indeed Nebenzal indicated in his letter that he would be sending the magazine a copy of the script. It seems likely, then, that the version of the film “fictionized” in MMM reflects the state of the script in the summer of 1946. If we read the MMM version, what do we find?

We find a narrative structure that’s far more peculiar than the finished film. Here’s how it goes.

The novelization starts with Chuck and Lorna in Havana, en route to their ship. Their carriage stops at the La Habana club, they go in for a drink, and Lorna is stabbed. Arrested, Chuck escapes from the police and takes refuge with Midnight in the tenement. She asks him what brought him to this pass, and in a flashback he tells her. This takes us back to Miami, where he finds Roman’s wallet, meets Lorna, falls in love, and flees with her. The flashback ends with the couple in their cabin aboard ship.

All this conforms to Woolrich’s book, and it strongly suggests that Nebenzal wasn’t blowing smoke when he said in September that he was making the editor “eliminate the flashback.” Evidently Chuck’s flashback existed in both a shooting script and an early version of the film. Its position must have been fairly firm for some time, if as late as September Nebenzal could move it to the front of the film.

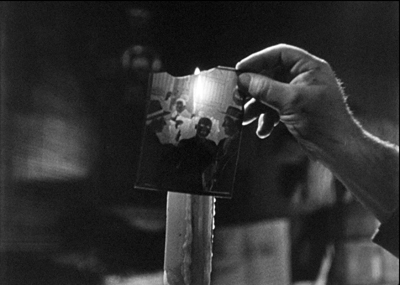

Does the novelization follow the Woolrich original after the flashback closes? It does up to a point. From the scene of Chuck and Lorna in their cabin aboard the ship, we return to the present, in Midnight’s apartment. There she advises Chuck on how to investigate Lorna’s death. He finds the photographer dead. Then comes the deviation. Chuck discovers Gino at Mrs. Chin’s shop, burning the incriminating photograph. In the novelization, Gino beats Chuck unconscious and dumps his body down to a cellar.

Now for the big twist. Chuck wakes up in his room in Roman’s mansion. Scott is now back in Miami, completely befuddled. All he can do is stumble to the phone, take some pills, and call Dr. Davidson. The novelization goes on to adhere pretty closely to the rest of the film as we have it.

In the novelization, in other words, the entire action up to this point, in both Havana and Miami, has been Chuck’s dream. Here’s the outline, just to be clear. What’s in green is veridical, what’s in red is not.

{Chuck’s dream begins: No front framing situation.}

Havana (dream): Lorna murdered at the Habana club, Chuck flees, and he meets Midnight. This contains:

Miami flashback (accurate up to the couple’s flight): Chuck hired by Eddie, meets Lorna, escapes with her on ship.

Havana (dream): Chuck investigates, is killed by Gino.

Dream ends: Chuck wakes up in Miami with amnesia.

Chuck goes to Dr. Davidson, who takes him to bar. Chuck rescues Lorna, and Gino and Eddie die in crash.

Epilogue: Couple freed, en route to Havana on ship.

Two things make this pattern striking—one minor, one pretty scandalous.

First, there’s no “front frame”: no situation that puts Chuck in a pre-dream reality. By convention, we don’t have to see him actually fall asleep, but it’s usual to provide circumstances that we can understand retrospectively as preparation for sleep. This is what we get in The Woman in the Window and other then-I-woke-up films. But this movie starts inside the dream.

Nowadays, of course, we’re used to sequences in which a dream is signaled only after the fact. In Out of Sight (1998) we see Karen Sisco sneak up on Jack Foley and then fall to kissing him in his bathtub; then the scene is revealed as a dream. But in the Forties, and even today, it wasn’t usual to have a dream launch the film and go on for over fifty minutes before revealing itself as a dream.

Second, the scandalous aspect. In the novelization’s version of the plot, and presumably the script and an early draft of the film, the dream includes the flashback to Miami. The framing dream material is fantasy, but the flashback is for the most part veridical. Eddie, Gino, Lorna et al. really did most of what we see them doing, even if the encounter with Midnight, the Habana murder, and Chuck’s fight with Gino aren’t real. The only stretch of the Miami flashback that isn’t real is the couple’s flight (which hasn’t happened yet in the waking world).

Here’s why, I suggest, we get those two lines when Chuck visits Davidson. “There doesn’t seem to be any beginning,” Chuck says. Right: because we never saw a beginning, an opening frame for the long dream stretch. And Davidson is at pains to reiterate that the Havana adventure is “dream-stuff” while Roman and Lorna are definitely real. Davidson’s remarks would have served as redundant confirmation for the audience that most of the Miami flashback could be trusted.

During the 1940s, filmmakers competed to find outlandish variants on subjective viewpoints, dreams, and flashbacks. Embedding real scenes as a flashback within a larger, definitely unreal but unmarked dream constitutes a genuine, if screwy innovation for the era.

Fixing it, sort of, in post

On all this circumstantial evidence, I surmise that the novelization’s weird structure was in the script as planned and in the film as initially shot during the summer of 1946. At some point, however—perhaps after previews—Nebenzal thought the better of it. He instructed the editor to move the Miami flashback to the front of the film, where it serves as a conventional chronological introduction to the action. But now what do you do with the Havana stuff? Are you going to kill off Lorna?

No. Clearly Nebenzal and his team had decided to keep the dream idea, but confine it wholly to the Havana episode. That allows Lorna to live at the film’s close. But now they would need to set up the dream within the Miami stretch. So they provided a frame that’s not in the novelization: the scene of Chuck stretching out on his bed as an equivocal prelude to the dream. In other words, a reshoot was called for.

Correspondence between Nebenzal and Paul Lazarus, Jr., head of advertising for United Artists, suggests considerable last-minute reworking. Nebenzal, invited to show some reels at a 19 August New York City trade event, declined, saying that nothing was in final shape. Having agreed to come to the event, he then demurred, saying he needed to start retakes on Monday 12 August. He promised to deliver the film “beginning of September,” but midway through that month he was shooting three endings, announcing a budget increase, and claiming he was eliminating the flashback. Not until 7 October did Lazarus finally get to see the film (which he praised). The trade press viewed The Chase on 11 October: a tight squeeze.

These events suggest that having decided to eliminate the flashback, Nebenzal arranged reshoots and postproduction adjustments to set up the dream with framing scenes in Chuck’s bedroom. Interestingly, those framing scenes show the bedroom as slightly different than we’ve seen it earlier. The lead-in to the dream shows the room as it looks in the later waking-up scene.

These show consistent placement of the phone on the desk, along with a chair and Chuck’s suitcase open on it. But earlier views of the room include different furnishings–no second chair by the desk, a floor lamp, a wastebasket by the bed, the phone in a different spot, a book supporting Chuck’s bedside lamp.

No big deal, of course; these shots are from earlier in the story than the night of Chuck’s departure. The hitch is that when Gino comes in after Chuck has left (that is, following Chuck’s lying on the bed in the first shot above), the room is as it was in the earlier scene. In the shot before Gino enters, we can see there’s no extra chair, all the stuff on the night table is as earlier in the film, and the Schlitz bottle is there–as it isn’t when Chuck stretched out before his departure, or when he wakes up thereafter.

The dream presentation of the room is identical with the earlier purportedly non-dream room. (As you’d expect if both setups were once part of the “real” flashback.) But those views are not identical with the look of the room when the dream began.

I’m not suggesting that the audience would notice these continuity lapses. I’m suggesting that they’re evidence of an imperfect reshoot. Here it appears that both the entry into the dream and the movement out from it weren’t filmed as they would normally be: in conjunction with the other scenes in the same set. It seems that some time after doing the first round of bedroom scenes, Nebenzal rebuilt or redressed the set and shot the first frame situation, that of Chuck going to sleep, and at the same time shot the closing situation, of him waking up. Nebenzal may have had one version of the wakeup scene already, since it was required by the earlier screenplay version. But perhaps he hadn’t completed it yet, or perhaps he just reshot it in the redressed set to be on the safe side. As far as I can tell, all the shots during Chuck’s return to consciousness are filmed in the redressed set, the one with the open suitcase.

I suspect that there was a change in the Havana sequence too. The novelization doesn’t have Chuck murdered, only struck unconscious. The film as we have it revises that to a kill. But the manner of presentation of his death—behind a curtain, with offscreen gunshots and an odd axial cut to the curtain—suggests some adjustment in production or postproduction. If the reshoot did have Chuck killed rather than clobbered, the change drives home the irreal nature of the dream. Nothing proves itself a fantasy more vividly than killing someone off in it and then revealing they’re still alive.

Endless love

If I’m right, the most ambitious storytelling innovation of the project, the veridical flashback swaddled inside an irreal dream sequence, was scotched. There are other incompatibilities between the finished film and production documents.

For example, The Black Path of Fear includes a moment when, after Lorna and Scott have escaped to the boat, they receive a telegram with a single message: LUCK. –ED It’s meant to suggest that Roman is aware of where they are and where they’re going, thus amping up the suspense. This moment is replicated in the MMM novelization, the typescript synopsis, and the synopsis in the presskit.

In the novelization, Scott burns the telegram. The moment is missing from the film, but something like this scene seems to have been planned for Chuck’s encounter with Midnight. Daily Variety reported:

Toughest camera job of the week, according to Franz Planer, lens chief for Seymour Nebenzal’s “The Chase,” is keeping the camera in focus during a 90-degree angle pan from a cablegram burning on top of a stove to a scene between Robert Cummings and Yolanda Lacca in a Havana tenement flat. It took 20 takes to get a perfect shot. The shot got added complication from the intense heat and the fact that the cameraman had to keep his eye glued to the eyepiece while moving from standing to sitting position.

This suggests that the film showed Chuck burning Roman’s message not with Lorna on shipboard but with Midnight in her apartment. The burning telegram might even have been a transition out of Chuck’s flashback explanation of what happened in Miami. That’s pretty speculative on my part, but here’s something more plausible—a fairly clear byproduct of all the last-minute reshuffling of scenes.

Once Eddie and Gino have been killed on the highway, we could end the film by showing Scott and Lorna embracing in their cabin, this time headed for Havana. That’s in fact the way the novelization and the synopses end. The film adds an extra epilogue of Eddie and Lorna embracing in the carriage outside the club. These shots are plainly recycled from early footage. Perhaps there was no suitably romantic footage of the couple’s reunion on shipboard. The shots we have don’t seem especially intimate, certainly not typical of a finale.

Or perhaps Cummings and Morgan were unavailable for retakes.

In any case, by providing the scavenged tag we have, the film raises the question: How can the real nightclub we see in the epilogue’s happy ending be, in a sort of Buñuelian recursion, the same one that Scott dreams in advance? How did Chuck know the very same bored driver would be there? The question becomes more pressing because the situation at the end seems to replay an exact moment in the dream, when the couple embrace in a carriage before going into the club. The carriage shots in the dream and in “reality” are uncannily similar. All that’s varied from the earlier scene is the order of the shots.

The last scene continues the romantic dialogue of the first Habana visit, as if nothing had happened in between. And the epilogue even uses a line that was in the opening of the novelization, and perhaps the screenplay: Chuck says he will love Lorna forever.

Maybe the filmmakers thought that audiences wouldn’t notice the near-identity with the earlier scene, and would just take it as Hollywood’s familiar here-we-go-again gimmick. But the effects are disconcerting. This nearly identical replay gives Chuck’s dream the power of prophecy. Or perhaps this last scene just starts the dream over again—and leads to the same fate for Lorna. The dream may have taken away Scott’s immediate memory of his affair with Lorna, but it has given him, through the film’s recycling of motifs, an uncanny power over the final bit of the narrative. He can intuit Eddie’s death and revisit in reality the scene of passion and murder he imagined. Were these associations fully intended by the filmmakers? Say rather that by shuffling together, somewhat desperately, characteristic 1940s devices, The Chase takes us into a winding labyrinth of alternative stories.

A later entry on the film offers some more evidence for the production changes that resulted in its peculiar structure.

First, many thanks to Mary Huelsbeck, Assistant Director of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, for helping me find valuable documents in the United Artists Corporation Records. It would be too lengthy to cite all the specific items I used, but the principal ones are in Series 3A: Producers Legal File, 1933-1936; Series 4D: The Paul Lazarus, Jr. Files, 1943-1949; and Series 5.3: United Artists Dialogues, 1928-1956.

The most important press releases are the one about the three endings, in “”Just for Variety,” Daily Variety (3 September 1946), 4, and the one about the elimination of the flashback, in “Hollywood Inside,” Daily Variety (16 September 1946), 2. The film reviews I’ve quoted are “The Chase,” Daily Variety (14 October 1946), 3; “The Chase,” Motion Picture Herald (19 October 1946), 3262; “Movie of the Week: The Chase,” Life (11 November 1946), 137; Archer Winsten, “Chase through a Maze,” New York Times (18 November 1946), 39; John L. Scott, “‘The Chase’ Suspenseful,” Los Angeles Times (25 January 1947), A5.

The Movie Mystery Magazine version includes some passages not in the final film, including internal monologues, flashbacks, and a delirious montage when Chuck is on his way to see Dr. Davidson. These are all pretty common techniques of the period, so it’s possible that the script, or an earlier version of the film, contained them.

Philip Yordan doesn’t have anything to say about these matters in the published interview with Pat McGilligan in Pat’s Backstory 2: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1940s and 1950s (University of California Press, 1991), 330-381. Yordan’s screenplay collection at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences apparently doesn’t include The Chase. Of course, if anyone knows where a script of the film may be found, I’d be grateful to learn of it.

I haven’t mentioned one of the strangest items in the film. Eddie Roman is the ultimate backseat driver, and he has installed an accelerator and clutch back there that allows him to override the driver’s control and speed up at will. He uses the gadget to test Chuck’s nerves during an outing, and it becomes the means by which he inflicts death on himself and Gino during their race to the dock. Me, I think it would have been a better payoff to let Chuck and Lorna, trussed up in the back seat while Eddie is driving, use the same mechanism to force the car to crash. But The Chase is the sort of movie that makes you spin off alternative scenarios as you please.

For in-depth information on Cornell Woolrich, the definitive source is Francis M Nevins, Jr.’s Cornell Woolrich: First You Dream, Then You Die (New York: Mysterious Press, 1988). Not a bad title for The Chase, actually. For more on flashback construction in the 1930s and 1940s, see “Grandmaster Flashback” and “Chinese boxes, Russian dolls, and Hollywood movies.”

The Chase (1946) United Artists pressbook.

Off-center 2: This one in the corner pocket

DB here, again:

We got a keen response to my entry on widescreen composition in Mad Max: Fury Road. Thanks! So it seemed worthwhile to look at composition in the older format of 4:3, good old 1.33:1–or rather, in sound cinema, 1.37: 1.

The problem for filmmakers in CinemaScope and other very wide processes is handling human bodies in conversations and other encounters (such as stomping somebody’s butt in an an action scene). You can more or less center the figures, and have all that extra space wasted. Or you can find ways to spread them out across the frame, which can lead to problems of guiding the viewer’s eye to the main points. If humans were lizards or Chevy Impalas, our bodies would fit the frame nicely, but as mostly vertical creatures, we aren’t well suited for the wide format. I suppose that’s why a lot of painted and photographed portraits are vertical.

By contrast, the squarer 4:3 frame is pretty well-suited to the human body. Since feet and legs aren’t usually as expressive as the upper part of the body, you can exclude the lower reaches and fit the rest of the torso snugly into the rectangle. That way you can get a lot of mileage out of faces, hands and arms. The classic filmmakers, I think, found ingenious ways to quietly and gracefully fill the frame while letting the actors act with body parts.

Since I’m watching (and rewatching) a fair number of Forties films these days, I’ll draw most of my examples from them. after a brief glance backward. I hope to suggest some creative choices that filmmakers might consider today, even though nearly everybody works in ratios wider than 4:3. I’ll also remind us that although the central area of the frame remains crucial, shifts away from it and back to it can yield a powerful pictorial dynamism.

Movies on the margins

Early years of silent cinema often featured bright, edge-to-edge imagery, and occasionally filmmakers put important story elements on the sides or in the corners. Louis Feuillade wasn’t hesitant about yanking our attention to an upper corner when a bell summons Moche in Fantômas (1913). A famous scene in Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912) shows Griffith trying something trickier. He divides our attention by having the Snapper Kid’s puff of cigarette smoke burst into the frame just as the rival gangster is doping the Little Lady’s drink. She doesn’t notice either event, as she’s distracted by the picture the thug has shown her, but there’s a chance we miss the doping because of the abrupt entry of the smoke.

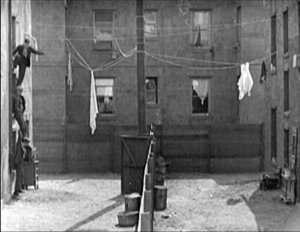

In Keaton’s maniacally geometrical Neighbors (1920), the backyard scenes make bold (and hilarious) use of the upper zones. Buster and the woman he loves try to communicate three floors up. Early on we see him leaning on the fence pining for her, while she stands on the balcony in the upper right. Later, he’ll escape from her house on a clothesline stretched across the yard. At the climax, he stacks up two friends to carry him up to her window.

Thankfully, the Keaton set from Masters of Cinema preserves some of the full original frames, complete with the curved corners seen up top. It’s also important to appreciate that in those days there was no reflex viewing, and so the DP couldn’t see exactly what the lens was getting. Framing these complex compositions required delicate judgment and plenty of experience.

Later filmmakers mostly stayed away from corners and edges. You couldn’t be sure that things put there would register on different image platforms. When films were destined chiefly for theatres, you couldn’t be absolutely sure that local screens would be masked correctly. Many projectors had a hot spot as well, rendering off-center items less bright. And any film transferred to 16mm (a strong market from the 1920s on) might be cropped somewhat. Accordingly, one trend in 1920s and 1930s cinematography was to darken the sides and edges a bit, acknowledging that the brighter central zone was more worth concentrating on.

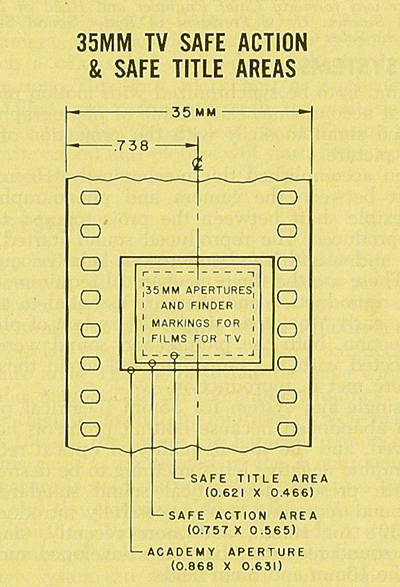

That tactic came in handy with the emergence of television, which established a “safe area” within the film frame for video transmission. TV cropped films quite considerably; cinematographers were advised in 1950 that

All main action should be held within about two-thirds of the picture. This prevents cut-off and tube edge distortion in television home receivers.

Older readers will remember how small and bulging those early CRT screens were.

By 1960, when it was evident that most films would eventually appear on TV, DP’s and engineers established the “safe areas” for both titles and story action. (See diagram surmounting this section.) Within the camera’s aperture area, which wouldn’t be fully shown on screen, the safe action area determined what would be seen in 35mm projection. “All significant action should take place within this portion of the frame,” says the American Cinematographer Manual.

Studio contracts required that TV screenings had to retain all credit titles, without chopping off anything. This is why credit sequences of widescreen films appear in widescreen even in cropped prints. So the safe title area was marked as what would be seen on a standard home TV monitor. If you do the math, the safe title area is indeed 67.7 % of the safe action area.

These framing constraints, etched on camera viewfinders, would certainly inhibit filmmakers from framing on the edges or the corners of the film shot. And when we see video versions of films from the 1.37 era (and frames like mine coming up) we have to recall that there was a bit more all around the edges than we have now.

All-over framing, and acting

Yet before TV, filmmakers in the 40s did exploit off-center zones in various ways. Often the tactic involved actors’ hands–crucial performance tools that become compositional factors. In His Girl Friday (1940), Walter Burns commands his frame centrally, yet when he makes his imperious gesture (“Get out!”) Hawks and DP Joseph Walker (genius) have left just enough room for the left arm to strike a new diagonal.

The framing of a long take in The Walls of Jericho (1948) lets Kirk Douglas steal a scene from Linda Darnell. As she pumps him for information, his hand sneaks out of frame to snatch bits of food from the buffet.

As the camera backs up, John Stahl and Arthur Miller (another genius) give us a chance to watch Kirk’s fingers hovering over the buffet. When Linda stops him with a frown, he shrugs, so to speak, with his hands. (A nice little piece of hand jive.)

The urge to work off-center is still more evident in films that exploit vigorous depth staging and deep-focus cinematography. Dynamic depth was a hallmark of 1940s American studio cinematography. If you’re going to have a strong foreground, you will probably put that element off to one side and balance it with something further back. This tendency is likely to empty out the geometrical center of the shot, especially if only two characters are involved. In addition, 1940s depth techniques often relied on high or low angles, and these framings are likely to make corner areas more significant. Here are examples from My Foolish Heart (1950): a big-head foreground typical of the period, and a slightly high angle that yields a diagonal composition.

Things can get pretty baroque. For Another Part of the Forest (1948), a prequel to The Little Foxes (1941), Michael Gordon carried Wyler’s depth style somewhat further. The Hubbard mansion has a huge terrace and a big parlor. Using the very top and very bottom of the frame, a sort of Advent-calendar framing allows Gordon to chart Ben’s hostile takeover of the household, replacing the patriarch Marcus at the climax. The fearsome Regina appears in the upper right window of the first frame, the lower doorway of the second.

In group scenes, several Forties directors like to crowd in faces, arms, and hands, all spread out in depth. I’ve analyzed this tendency in Panic in the Streets (1950), but we see it in Another Part of the Forest too. Again, character movement can reveal peripheral elements of the drama.

At the dinner, Birdie innocently thanks Ben for trying to help her family with their money problems and bolts from the room, going out behind Ben’s back. The reframing brings in at the left margin a minor character, a musician hired to entertain for the evening. But in a later phase of the scene he will–still in the distance–protest Marcus’s cruelty, so this shot primes him for his future role.

At one high point, the center area is emptied out boldly and the corners get a real workout. On the staircase, the callow son Oscar begs Marcus for money to enable him to run off with his girlfriend. (As in Little Foxes, the family staircase is very important–as it is in Lillian Hellman’s original plays.) Ben watches warily from the bottom frame edge. Nobody occupies the geomentrical center.

Later, on the same staircase, Ben steps up to confront his father while Regina approaches. It’s an odd confrontation, though, because Ben is perched in the left corner, mostly turned from us and handily edge-lit. Marcus turns, jammed into the upper right. Goaded by Ben’s taunts, he slaps Ben hard. Here’s the brief extract.

The key action takes place on the fringes of the frame, while the lower center is saved for Regina’s reaction–for once, a more or less normal human one. Even allowing for the cropping induced by the video safe-title area, this is pretty intense staging.

The corners can be activated in less flagrant ways. Take this scene from My Foolish Heart. Eloise has learned that her lover has been killed in air maneuvers. Pregnant but unmarried, she goes to a dance, where an old flame, Lew asks her to go on a drive. They park by the ocean, and she succumbs to him. Here’s the sequence as directed by Mark Robson and shot by Lee Garmes (another genius).

In the fairly conventional shot/ reverse-shot, the lower left corner is primed by Eloise’s looking down at the water and Lew’s hand stealing around her.

Later, when Lew pulls her close, (a) we can’t see her; (b) his expression doesn’t change and is only partly visible; so that (c) his emotion is registered by the passionate twist of his grip on her shoulder. Lew’s hand comes out from the corner pocket.

Perhaps Eloise is recalling another piece of hand jive, this time from her lost love.

For many directors, then, every zone of the screen could be used, thanks to the good old 4:3 ratio. It’s body-friendly, human-sized, and can be packed with action, big or small.

Mabuse directs

In other entries (here and here) I’ve mentioned one of the supreme masters of off-center framing, Fritz Lang. Superimpose these two frames and watch Kriemhilde point to the atomic apple in Cloak and Dagger (1946).

From the very start of Ministry of Fear (1944), the visual field comes alive with pouches, crannies, and bolt-holes. The first image of the film is a clock, but when the credits end the camera pulls back and tucks it into the corner as the asylum superintendant enters. (The shot is at the end of today’s entry.) Here and elsewhere, Lang uses slight high angles to create diagonals and corner-based compositions.

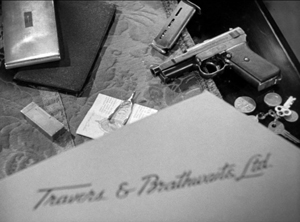

In the course of the film, pistols circulate. Neale lifts one from Mrs. Bellane (strongly primed, upper left), keeps her from appropriating it (lower center), and secures it nuzzling his left knee (lower right).

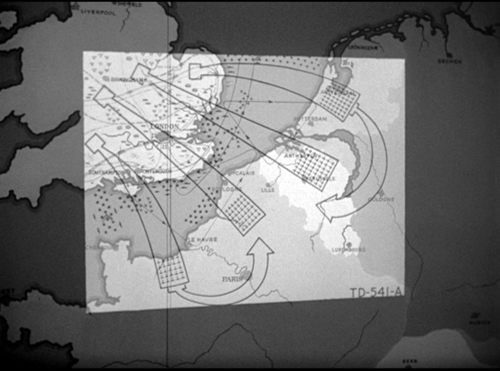

Later, Neale’s POV primes the placement of a pistol on the desktop (naturally, off-center), so that we’re trained to spot it in a more distant shot, perilously close to the hand of the treacherous Willi.

Amid so many through-composed frames, an abrupt reframing calls us to attention. Unlike Hawks and Walker’s handling of Walter in His Girl Friday, Lang and his DP Henry Sharp (great name for a DP, like Theodore Sparkuhl and Frank Planer) gives things a sharp snap when Willi raises his hand.

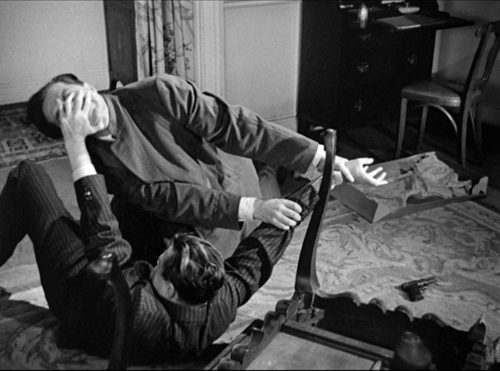

Lang drew all his images in advance himself, not trusting the task to a storyboarder. Avoiding the flashy deep-focus of Wyler and company, he created a sober pictorial flow that can calmly swirl information into any area of the frame. It’s hard not to see the stolen attack maps, surmounting today’s entry, as laying bare Lang’s centripetal vectors of movement. No wonder in the second frame up top, as Willi and Neale struggle in a wrenching diagonal mimicking the map’s arrows, that damn pistol strays off on its own.

Sometimes film technology improves over time. For instance, digital cinema today is better in many respects than it was in 1999. But not all changes are for the better. The arrival of widescreen cinema was also a loss. Changing the proportions of the frame blocked some of the creative options that had been explored in the 4:3 format. Occasionally, those options could be modified for CinemaScope and other wide-image formats; I trace some examples in this video lecture. But the open-sided framings in most widescreen films today suggest that most filmmakers haven’t explored the wide format to the degree that classical directors did with the squarish one.

More generally, it’s worth remembering that the film frame is a basic tool, creating not only a window on a three-dimensional scene but also a two-dimensional surface that requires composition–either standardized or more novel. Instead of being a dead-on target, the center can be an axis around which pictorial forces push and pull, drift away and bounce around. After all, we’re talking about moving pictures.

Thanks to Paul Rayton, movie tech guru, for information on 16mm cropping.

My image of the safe areas and the second quotation about them is taken from American Cinematographer Manual 1st ed., ed. Joseph C. Mascelli (Hollywood: ASC, 1960), 329-331. The older quotation about cropping for television comes from American Cinematographer Handbook and Reference Guide 7th ed., ed. Jackson J. Rose (Hollywood: ASC, 1950), 210.

I hope you noticed that I admirably refrained from quoting Lang, who famously said that CinemaScope was good only for…well, you can finish it. Of course he says it in Godard’s Contempt (1963), but he told Peter Bogdanovich that he agreed.

[In ‘Scope] it was very hard to show somebody standing at a table, because either you couldn’t show the table or the person had to be back too far. And you had empty spaces on both sides which you had to fill with something. When you have two people you can fill it up with walking around, taking something someplace, so on. But when you have only one person, there’s a big head and right and left you have nothing (Who the Devil Made It (Knopf, 1997), 224).

For more on the stylistics and technology of depth in 1940s American film, see The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (Columbia University Press, 1985), which Kristin and I wrote with Janet Staiger, Chapter 27, and my On the History of Film Style (Harvard University Press, 1997), Chapter 6. Many blog entries on this site are relevant to today’s post; search “deep-focus cinematography” and “depth staging.” If you want just one for a quick summary, try “Problems, problems: Wyler’s workarounds.” Some of the issues discussed here, about densely packing the frame, are considered more generally in “You are my density,” which includes an analysis of a scene in Lang’s Hangmen Also Die (1943).

Ministry of Fear (1944).

The ten best films of … 1924

Die Nibelungen: Siegfried

Kristin here:

For a seventh year running, we skip ranking the current year’s films and instead hark back 90 years.

We started out with a list that was essentially an appendix to an entry, but soon we were dedicating whole entries just to the list. Our entries for past years are here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, and 1923.

These lists are our way of calling attention to important silent films that some readers may have overlooked. In one case here we point out a largely forgotten film that deserves to be better known, in the hope that an archive will take the hint. With the proliferation of silent-film festivals, of DVD and Blu-ray releases with restored prints and supplemental material, and of TCM’s eclectic screenings of foreign and silent titles, there seems to be considerably more interest in these early classics. Herewith our choices for 1924.

For the last few years I’ve struggled to fill out the full list of ten films with truly deserving items. But as I’ve been predicting, the 1924 choices fell easily into place. As usual, some of these are obvious picks, already famous to most readers. Others are less obvious, and a few are unknown except to specialists. Some, though very important historically and artistically, are not currently available on DVD, which is a real shame.

At last, the USSR

Films in the Soviet Montage style make up one of the most important cinema movements of all times. The key filmmakers of the movement, Eisenstein, Pukovkin, Dovzhenko, Kuleshov, Kozintzev and Trauberg, and others began their work later than the German Expressionist and French Impressionist directors. But at last one joins our list, with Lev Kuleshov’s The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks.

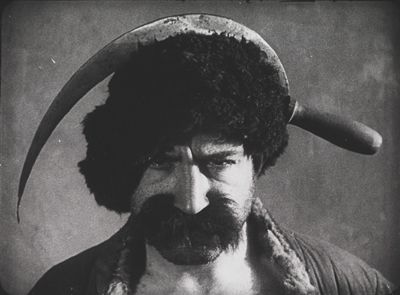

Although Kuleshov’s work has become more widely available, his most familiar work is still By the Law (1926), a grim tale of two members of a gold-prospecting team agonizing over how to bring to justice a colleague who has committed a terrible crime. Mr. West couldn’t be more different. This hilarious and grotesque comedy satirizes American perceptions of the new Soviet Union, as Mr. West, president of the YMCA, comes to for a visit, his faithful cowboy friend Jeddie in tow. They’re terrified of the barbaric land they expect to encounter, and a gang of thieves dupe Mr. West by dressing up in outfits that caricature West’s images of Bolsheviks (above).

In making the film, Kuleshov and his team drew upon the experiments they had been doing in his classes he ran of the early 1920s. Film stock was scarce and all he and his students could do was practice staging scenes and make short editing experiments. They explored the possibilities of “biomechanical acting,” a style based more on gymnastic control and energy than on psychological subtleties of facial expression.

Once the group did get the resources to make a feature, their delight is evident in the lively editing and the exuberant performances. Alexandra Khokhlova, a gangly woman who was married to Kuleshov and starred in most of his films, plays a vamp who tries to lure Mr. West into her toils. Pudovkin, who studied with Kuleshov before going into directing himself, is the well-dressed gang leader who pretends to guide Mr. West away from danger. Boris Barnet, also to become a major director, performs feats of derring-do as Jeddie tries to save Mr. West.

Mr. West is not only a satire on Western fears of post-Revolutionary Russia but also a parody of American serials. (The latter was something Barnet soon tried in an actual serial, his 1926 Miss Mend.)

Mr. West is available on DVD in Flicker Alley’s set, “Landmarks of Early Soviet Film.”

German Expressionism begins to wind down

Last year I was hard put to pick a film to represent the German Expressionist movement in the top ten. I chose Erdgeist but mentioned Schatten and Raskolnikow as runners-up. By 1924 there were fewer Expressionist films released, though the movement would linger on until 1927, mainly carried on by the two greatest directors who had worked in the Expressionist movement: F. W. Murnau and Fritz Lang. Each of these contributed a classic film in 1924: Murnau’s The Last Laugh and Lang’s two-part epic: Die Nibelungen: Siegfried and Kriemhild’s Revenge).

The Last Laugh isn’t really Expressionist. The sets are mildly in the style, but what really fascinated Murnau at this point was the freedom of camera movement introduced by French Impressionism. He set out to make a character study. Emil Jannings plays a doorman in a large hotel (none of the characters’ names are given). His regal bearing and fancy uniform bring him respect among his fellow employees and from relatives and neighbors in the lower-middle-class neighborhood where he lives. He has aged to the point where he carry large luggage and is abruptly demoted to work as a rest-room attendant.

Murnau introduced what came to be known in Germany as the entfesselte Kamera, the “unfastened camera,” beginning in the opening shot where an elevator with a grill descends, carrying the camera and dramatically revealing the lobby. Murnau may have been directly influenced by one of last year’s top-10, Cœur fidèle, where Epstein put his camera on a spinning-swings carnival ride. Murnau saw other uses for the device. Like the Impressionists, he conveyed drunkenness through moving camera, though in this case he put the actor and camera on a turntable, so that the room spins past behind Jannings, conveying the dizzy happiness of the doorman at a party (above).

Using more imagination, Murnau follows sound with his camera. As the party ends, musicians exit to the apartment-block courtyard, and one plays a final tune under the window. Starting with a close-up, the camera “cranes” diagonally up and backward until the men are in long shot. A cut takes us to the doorman inside, happily listening.

Actually the camera was not on a crane. Murnau and cinematographer Karl Freund affixed a track over the courtyard with a small metal elevator underneath, so that the camera could move both back and forth and up and down. The camera was not literally unfastened in these cases, but it looked like it was.

Murnau wanted to end the film on a grim note with the protagonist seated alone in the hotel rest room. Commercial considerations led to a happier ending, however, with him unexpectedly becoming wealthy. The twist was so outrageous that Carl Mayer, the scenarist, considered it a comment on Hollywood’s insistence on happy outcomes. Hence the English title The Last Laugh. The original German means “The Last Man.”

The Last Laugh got distribution in the USA, but it was not a success. Hollywood practitioners studied it, though, and started hanging cameras from tracks themselves and trying other tricks. The track backward above a long, laden banqueting table soon became a cliché of Hollywood cinema.

Murnau would make two more mildly Expressionist films, Tartuffe (1925) and Faust (1926) before heading to Hollywood to make the ultimate hanging-camera film, Sunrise (1927)

The Last Laugh is available from Kino in the USA and Eureka! in the UK.

One of my favorite films of the 1920s is Lang’s two-parter, Die Nibelungen: Siegfried and Die Nibelungen: Kriemhilds Rache (Kriemhild’s Revenge). An adaptation of the ancient German myth, it mostly proceeds at a stately pace until the final battle scene. Some may find it slow, especially when compared with the lively, suspenseful Dr. Mabuse der Spieler (1922) and Spione (1928). Yet its leisurely presentation is appropriate to the subject matter. Equally important, lingering over images allows us to notice the details of the extraordinary settings and costumes, with their busy decorated surfaces and their startling arrangements within the shot.

Take the image at the top of this entry. Brunhilde, having been forced to marry King Gunther against her will, envies her sister-in-law Kriemhild, who has married Siegfried, the man Brunhilde loves. In this shot, Brunhilde mounts the steps of Worms Cathedral to confront Kriemhild and assert her right to enter the cathedral first. We see her from behind and then at the upper left as her ladies follow her, wrapped in their patterned hoods and black cloaks, creating an almost abstract composition. Lang build the enormous stairway outside the cathedral in two stages and then used the set imaginatively to stage several ceremonies and dramatic conflicts.

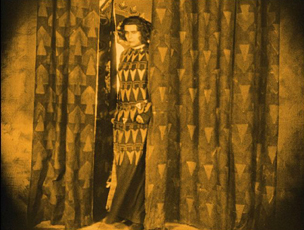

What makes this film Expressionist, I would argue, is the way the actors and settings interact, as in this moment when Brunhilde pauses by her window and then comes forward through the slightly parted curtain, exiting left. She pauses in the opening, her dress seemingly becoming part of the curtains for a moment.

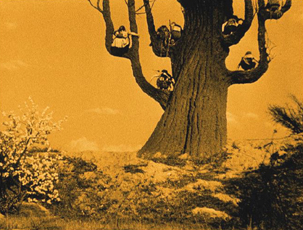

The similarity and the pause have no narrative function, but it’s a very Expressionist composition. Insistent symmetry and acting also contribute to the style. In the second plot, the Hunnish King Etzel asks for Krienhild’s hand in marriage. She agrees on the condition that he will aid her in exacting her revenge on Siegfried’s killers. Upon her move to the land of the Huns, the style becomes a more familiar sort of Expressionism, with distorted trees and buildings that looks like they were built of mud that settled oddly before drying:

The elements of the German tales are all here: love, betrayal, suicide, revenge, presented in images worth savoring.

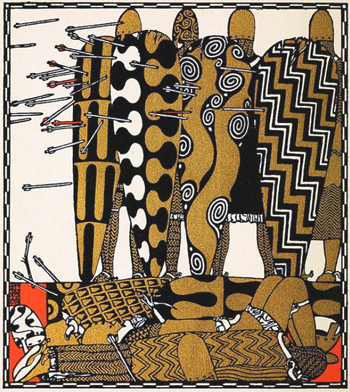

Lang was inspired in his approach to the film’s visuals by some illustrations by Carl Otto Czeschka for a 1909 retelling of Die Nibelungen published in 1909. The heavy decoration on the knight’s shields and many other surfaces in the film somewhat resemble this image, for example:

Yet the resemblance is far from exact. Clearly Lang used elements from these illustrations and took them off in his own direction.

The film has recently been restored and looks great on Blu-ray. Kino in the US and Eureka! in England have brought it out. Both have DVD editions as well.

Scandinavia’s golden age drawing to a close

During the first half of the 1920s, the Swedish cinema was a victim of its own success. Victor Sjöstrom (who has figured in these lists in 1918 and 1921, as well as in our “Lucky ’13” entry), had headed to MGM, becoming Victor Seastrom. In 1924 he released his first two films in 1924: Name the Man and He Who Gets Slapped. The latter was the newly formed MGM’s first in-house production to be released. It was a huge success, no doubt in large part due to the growing stardom of Lon Chaney, and it put the studio on the map and allowed Seastrom to stay in Hollywood, notably for The Scarlet Letter (1926) and The Wind (1928).

Mauritz Stiller (also a previous top-10 choice) was about to head for Hollywood as well, but his final Swedish film is one of his finest. Gösta Berlings Saga, a epic adaptation of Selma Lagerlöf’s novel, was made in two parts lasting over three hours. Many people will know it as the debut film of Greta Garbo. Fans should be forewarned that she is an important character and appears in the early and late scenes but disappears for a long stretch in the middle.

[December 30: As our friend Antti Alanen points out, Garbo had already acted in a comedy, Luffar-Petter (Peter the Tramp, 1922) and in some short advertisements.]

The film begins with Berling, a drunken pastor in a small town, being relieved of his duties. He ends up being taken in the “Chevaliers” at Ekeby the country estate of Margaretha Samzelius, a tough middle-aged woman who runs a group of foundries she has inherited from a lover. The Chevaliers are a group of hangers-0n, men who can drink and laze about most of the time but who must be charming and entertaining at Samzelius’ many dinner parties. Berling has a number of chances to redeem himself but ends up harming the people around him and sinking lower into despair. He is finally redeemed by the love of the Garbo character, Elizabeth, the new bride of a wealthy neighbor, to whom, it turns out through a technicality–and happy coincidence–she is not actually married.

Hansen and Garbo make a gorgeous couple (below left), but they are upstaged by the great Swedish stage actress Gerde Lundequist as Samzelius:

As usual, the film contains lovely scenes in the Swedish landscapes. There are some impressive night sleigh rides, including a famous scene in which Berling and Elizabeth are chased across a frozen lake by wolves. There is also one of the most impressive fire scenes I can recall from the silent era, as Samzelius’ efforts to smoke the Chevaliers out of the guest house where they live and inadvertently sets fire to the big main house as well.

Unfortunately the film was cut down into a single feature for its release outside Scandinavia. The Story of Gosta Berling was the main version that circulated for many years. The Swedish Film Institute restored it in stages as more footage was found, but the current print, at 183 minutes, is still missing some footage.

Beware picking up an older video release with the truncated film. The restored version was released on DVD in the USA by Kino. The original Svensk Filmindustri release (with English, French, Portuguese, German, and Spanish subtitles), is available here. The same DVD comes in a box set of six Swedish silent classics, which is widely available from the usual online sources.

Carl Dreyer has popped up on this blog several times, usually in passing. Not surprising, since David wrote a book about him way back 1981. Here he makes his second appearance on our ten-best lists (the first having been for his first feature, The President, in 1919) with Michael.

The film centers around a wealthy, aging artist, Claude Zoret. The main room of his house is decorated with several eye-catching pieces of sculpture, notably a mysterious battered head that looms in the background of many shots. Is it one of Zoret’s own works? Is it part of a collection of ancient statues? Much of the action takes place here, which has led some historians to place Michael in the tradition of the Kammerspiel. David calls it a borderline case. There are certainly scenes that leave Zoret’s studio, most notably one in a large theater set.

The film has been hailed as an early treatment of homosexuality. Although there is nothing overtly expressed, it is hard not to read such a subtext into the action. Zoret, wonderfully played by Danish director Benjamin Christensen, has many guests and admirers visit him, creating a little all-male coterie. He has taken in a young protegé, a very beautiful and very young Walter Slezak. Zoret refers figuratively to Michael as his son, but there seems to be another tie between the two. Moreover, there may be a hint that Charles Switt, a journalist apparently writing a biography of Zoret (at the center of the frame above), feels some jealousy toward the young man.

Trouble begins when a princess comes to commission a portrait from Zoret. Although he usually doesn’t do commissions, he is intrigued by her face and agrees. During her visits to the studio to pose, she meet Michael, who is immediately smitten. The affair continues as Michael becomes increasingly inconsiderate to Zoret,borrowing money to continue the affair and missing an important showing of his work. In contrast, Zoret shows unwavering generosity to Michael, despite being devastated by his desertion.

Ultimately Zoret paints his last work, showing an elderly, lonely man against a barren seascape. It is hailed as a masterpiece at a party which Michael does not attend.

The character study proceeds at Dreyer’s usual formal pace, and yet it is never dull. As much as any of his silent films, it looks forward in tone to his later sound ones.

A very nice print of Michael is available in the UK from Eureka! (not deliverable to the USA); Kino released what I assume is the same print in the USA.

She was nothing but a poor flower-maker

Every now and then I want to put a film on the list which is impossible to see unless you happen to live near one of the archives that has a print and they happen to program it. Still, in the hope of inspiring someone to restore it and make it available, I proceed.

The film is Jean Epstein’s L’Affiche (“The Poster”). Epstein first made our list last year for the much better known Cœur fidèle. L’Affiche is a bit like the earlier film, a simple melodrama made in the French Impressionist style. Its situation is highly conventional, and its plot depends on a massive coincidence.

The heroine is introduced as Marie, one of several women making artificial flowers. On her lunch break she thinks back to a romantic day she spent in the country. There she meets a young man, Richard. The couple go to an expensive restaurant, and Richard seduces Marie, and then abandons her, driving away alone the next morning.

Three years pass, and Marie has a small child, also named Richard. She enters him in a contest for the most beautiful child, with a cash prize, offered by an insurance company that wants to put the winner on their advertising posters. The boy wins, and Marie signs a 10-year contract for the rights to use little Richard’s image.

The child dies, however, and Marie visits his grave. As she leaves, she sees a huge poster with his image. The campaign has begun. Everywhere in Paris she goes, she sees the poster and finally begs the insurance company to end the campaign. The boss, however, refuses. Marie begins tearing down the posters, and she is soon arrested. Epstein handles the arrest scene without an establishing shot but builds it up through close-ups.

Initially we see only the back of Marie’s head and her arms tearing down a poster. There a cut-in to slightly closer framing as a policeman’s hand comes into the shot and touches her shoulder. A third shot shows her turning to the officer and staring in a way that suggests she is becoming mentally unbalanced. Finally a long shot establishes the scene as a second policemen enters to help arrest her.

It’s the sort of gradual revelation of space that Kuleshov was working with at the same time.

The boss of the insurance company is informed of this and sends his son to file a complaint against her. New copies of the poster are being put up all over town. The son is none other than the Richard who seduced Marie years before. Hearing her tale, he asks her forgiveness and takes her home to his parents. The father forbids their marriage, they marry anyway, and eventually (after his own younger child dies!), the boss blesses the marriage and agrees to take down the posters.

Summarized baldly, it sounds like an impossible plot to take seriously, but Epstein’s delicate, understated approach in presenting it and Nathalie Lissenko’s affecting performance as Marie manage to make it a great film. It’s full of Impressionist moments: Marie’s memory of her romantic day with Richard, a dance scene with rhythmic editing, a dream sequence, and plenty of gauzy shots and fancy wipes at transitions.

Earlier this year I complained because L’Affiche was not included in the big new box set of Epstein’s work, despite almost everything else from the period being there. It’s also not on the box set of films made at the Russian emigré studio, Albatros, even though Epstein’s other three Albatros films are there. I don’t whether there are rights problems or there simply isn’t a good enough print.

At least one streaming service claims to have L’Affiche available, but a search turns up numerous complaints about the site.

I should make mention of one other Impressionist film that came out in 1924. Perhaps it should be on the list rather than L’Affiche. It’s Marcel L’Herbier’s L’Inhumaine. L’Herbier appeared on our 1921 list for El Dorado, and even then I expressed reservations. Most of his films seem cold and by-the-numbers to me, not to mention a bit pretentious. But his films were historically important, and L’Inhumaine was influential in its use of art deco sets. At one time the film was available on DVD, but it seems to be out of print.

Three funny men …

And no, it’s not Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd this time. Chaplin didn’t release a film in 1924. His next would be what many would consider his funniest feature, The Gold Rush.

Over the years I’ve stressed that during the 1910s, the three great comics were working in shorts, honing their filmmaking and working up to their great series of features. By 1923 they had fully made the transition: Lloyd made Safety Last and Keaton Our Hospitality. Safety Last had a simpler plot, structured mainly by the stages of the hero’s climb up a building. Keaton went further with a complex story of a romance blooming between members of feuding families, using multiple locations, a developing causal line, and clever motifs. (We analyze it in Chapter 4 of Film Art: An Introduction.)

In 1924, Lloyd achieved a similar complexity with Girl Shy, one of his greatest films. He plays a bashful young tailor’s assistant who is terrified of women. Yet in secret he writes a guide for seducers, taking on the narrational persona of a jaded man of the world. Clearly he has taken his inspiration from movies of the day. The imaginary scenes from his book dramatize his success in gaining the love of a vamp (see bottom) and a flapper. The publishers decide that the book is so over the top that they will publish it as a comic story. During all this Harold develops a relationship with Mary, a quiet young woman from a wealthy family. When her father tries to buy Harold off, he pretends to spurn Mary. She is about to marry a rich man, but Harold determines to stop the wedding.

There develops one of the most epic chase scenes in all silent comedy, and indeed all cinema, as Harold commandeers all manner of vehicles, from cars and wagons to a firetruck and a speeding trolley (above).

Even Keaton never outdid that one. But from 1923 to 1927, these two each created a string of innovative, carefully crafted, hilarious films.

Girl Shy used to be available in a 3-DVD set from New Line, but that is no longer available–though one optimistic third-party seller offers it, still sealed in plastic, for $399.99). Now the individual releases of each DVD seem to be slipping out of print as well. Volume 1, which contains Girl Shy, is definitely out of print. Be forewarned: Volume 2, which includes the wonderful 1927 film The Kid Brother (look for it on a future list) seems like it’s not long for this world, and the same is true of Volume 3, with For Heaven’s Sake (1926).

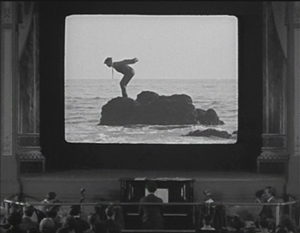

It was difficult to choose between Keaton’s two major releases of 1924, Sherlock Jr. and The Navigator. I chose the former mainly because of its perpetually astonishing transition from the frame story of a small-town projectionist unlucky in love to his dream of himself as a sophisticated detective. His dream takes the form of a movie, and the sleeping projectionist walks through the theater and into the onscreen action. With extraordinary precision, Keaton maintains a long-take framing of the pianist and audience in the auditorium while the hero onscreen undergoes a series of unexpected shot changes. In each he is in the same pose and position within the screen, but the backgrounds change arbitrarily, as when he begins to dive from a rock into the ocean and finds himself landing in a snowdrift:

The result is a marvelously convincing technical feat, giving the illusion of being a single shot as far as the theater is concerned and on the movie screen a character wandering through an appropriately dream-like series of edited shots. In general, Keaton was the most adept of the three great comics at using cinema technology to create gags, and this is his most elaborate attempt. (Though see also his short, The Playhouse, in which multiple exposures, flawlessly managed in-camera, create Keaton clones that play all the roles.)