Archive for the 'Directors: Lang' Category

The ten best films of … 1922

Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler, Part 1.

Kristin here:

As the end of the year approaches and critics are posting their ten-best lists for the year, David and I once again fail to follow that tradition. Instead, we follow our own custom, now six years old, and turn our historians’ eyes back ninety years to offer ten great films from 1922. Of course, there are many films from the silent era that are lurking in archives, waiting to be discovered. Still, pointing to some noteworthy films we do have may help viewers to explore that rich period of cinema’s past.

Our previous lists can be found here, for 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, and 1921.

For the past two years, I’ve noted that it was difficult to fill out the list of ten masterpieces. I keep thinking that I’ll get to a year where I won’t have to say that, but 1922 turns out not to be that year. Some titles were obvious, but the last one or two took some hunting.

As usual, one problem is that so many films are lost. Not one of John Ford’s three films of 1922 survives. In other cases great directors made lesser films. Important though Das Weib des Pharao was in Ernst Lubitsch’s career, partly because it shows him quickly picking up influences from Hollywood films, I can’t rank it among his first-rate titles. The same is true of Victor Sjöström, whose Vem dömer isn’t up to the level of other films like The Outlaw and His Wife.

Some of the films here, then, we consider classics but not masterpieces. Still, they have been influential and are well-regarded by other critics and historians. We’ll just call attention to them and let people form their own opinions.

Germany rules

But here are two full-fledged masterpieces, both from the German Expressionist movement. They demonstrate the potential for popular genres—here the horror and master-criminal genres—to achieve the highest level of filmmaking.

Few of F. W. Murnau’s early films survive, but there’s no doubt that he hit his stride in or before 1922. He made two outstanding films that year, Der brennende Acker (“The Burning Earth”) and Phantom, along with one of his very finest, Nosferatu. It is the earliest surviving film adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. (“Nosferatu” is Rumanian for “vampire.”)

Nosferatu is generally considered an Expressionist film, though there are only a few of the stylized sets that we tend to think of as vital to that artistic movement. Murnau instead mostly uses a combination of staging and framing in real locales to create echoes of shapes between characters and their surroundings, something usually accomplished through more painterly means in films like Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari and Die Nibelungen. The nested arches in the left image frame Hutter’s arms, while Ellen’s forlorn slump on the bench as she awaits her husband’s return is juxtaposed with the leaning crosses that hint at fruitless vigils in the past.

One of my favorite moments in Nosferatu comes during the scene where Count Orlock is about to attack Hutter in one of the bedrooms in his castle. Ellen, at home in Wisburg, somehow senses this and in a panic throws out her arms in a desperate appeal for mercy. Orlock turns and looks away from Hutter, and the next shot again shows Ellen’s appeal.

It is a classic shot/reverse-shot situation, and yet the two are in different countries, many miles apart. The situation is ambiguous. Does Orlock sense Ellen’s appeal? Does he somehow magically see her from afar? Whichever is the case, he does leave Hutter’s room, and the clear implication is that her gesture has caused that withdrawal. Such a treatment of space is unusual, to say the least.

“False” eyeline matches or shot/reverse-shot passages linking distant characters were already fairly conventional. Hoping to put another of Maurice Tourneur’s films on our ten-best list, I watched his 1922 Lorna Doone. Though it has some marvelous passages, especially in the final battle, I couldn’t justify including it. Still, it provided a more conventional version of the false shot/reverse shot. In a scene where the hero thinks of Lorna, looking off front right, the following shot shows her thinking of him and looking off left.

They are in houses on neighboring estates, but they certainly cannot see each other. Moreover, there’s no indication that either suspects the other one is thinking of him/her. There is no ambiguity. Clearly the lovers are simply daydreaming about each other. The Nosferatu scene is more puzzling and evocative.

There is much more that once could say about Nosferatu—especially the experimentation with fast motion, negative footage, and pixillation to render the supernatural nature of the vampire—but I leave that for the reader to discover. There are a number of DVD versions available, but the Kino one contains the restored print and a documentary about the film’s production; the restoration is also available in the UK from Eureka!.

If this blog is still functioning in ten years, our list will definitely include a second great vampire film, Carl Dreyer’s Vampyr.

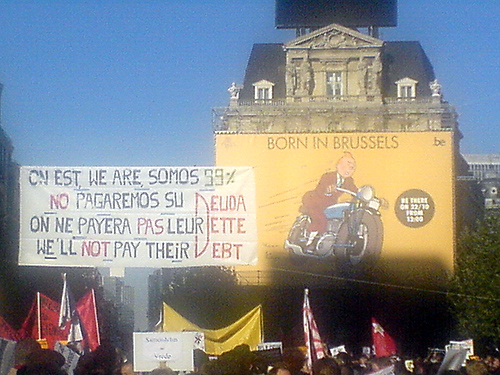

While Nosferatu plays on exotic, historic fantasy, Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (“Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler”) places its bizarre crime story squarely in contemporary Berlin. Mabuse (the incomparable Rudolf Klein-Rogge) is a master criminal with hypnotic powers, a man of innumerable disguises who lures his victims into gambling, whether in casinos or on the stock exchange. He also steals crucial documents to manipulate stock prices and controls the lives of many of the main characters. Throughout the lengthy plot, Detective von Wenk follows Mabuse’s trail, himself eventually falling under the criminal’s spell before exposing Mabuse’s identity.

Unlike with Murnau, we now have all of Lang’s early films and can judge his entire career. Arguably his first great film was Der müde Tod, which was on last year’s list. The first of his three Dr. Mabuse films (the others being Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse, 1933, and his last film, Die tausend Augen des Dr. Mabuse, 1960) was a step upward. It was made as a two-part serial: Der grosse Spieler—Ein Bild der Zeit (“The Great Gambler—A Picture of the Time”) and Inferno: Ein Spiel von Menschen unserer Zeit (“Inferno: A Play about People of Our Time”); together the parts run about four and a half hours.

The plot of Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler is very complicated and demonstrates Lang’s extraordinary ability to present a narrative visually. His sets, lighting, and staging are impeccable and already recognizably Langian. Consider the frame at the top of this entry.

In a gambling den, von Wenk, at the center top, and two important female characters, Countess Told, beside von Wenk, and Cara Carozza, left foreground, are staring at a rich old lady who has just gambled away a huge amount of money, caught by Mabuse’s spell. Her loss is the central action, yet she is placed so low in the frame as to be recognizable primarily by her silly beaded hat. Her gigolo, partly offscreen at the right, considers his position in the light of this disaster. Cara reacts with horror, the Countess and von Wenk with distress and sympathy. The other woman is an onlooker.

The tableau style of staging, keeping all the significant characters onscreen and moving them by slight increments to stress each character in turn, is still in play here, but the camera is closer to the actors, and they don’t move much. This isn’t just a tiny moment caught in the midst of a shifting composition. This is the composition. It looks remarkably modern. Each character, in his or her own way, is wondering, as we are, what has brought this minor character to such a pass. And she is tucked into a corner of the frame, as Lang will do in later films.

Dr. Mabuse‘s stress on “Our Time,” contemporary Weimar Germany, brings in the film’s Expressionistic elements. Expressionism here isn’t an all-encompassing filmic treatment that reflects a fantasy world or the psychological extremes of the characters. Instead, it is a tangible decorative impulse pervading the modern city. Below, von Wenk responds with distaste upon first viewing Count Told’s collection of modern art; yet in another scene, he calmly dines with an associate in a thoroughly Expressionist restaurant:

The bits of set visible in the background of this entry’s top frame indicate that the casino is another Expressionist locale.

The restored two-part film is available from Kino in the USA and in “The Complete Fritz Lang Dr. Mabuse Box Set” and from Eureka!’s “Masters of Cinema” series in the UK.

The grandiose and the modest as French Impressionism defines itself

The French Impressionist film movement can be said to have begun in 1918 with Abel Gance’s La Dixième Symphonie, though it has relatively few moments of the sort that came to define the style. It primarily uses superimpositions and split screen to convey a sense of the composer’s musical performances. Films by critic and theorist Louis Delluc followed, and Marcel L’Herbier explored pictorial and poetic effects in his early films. Highly subjective uses of film technique, which we think of as crucial to Impressionism, appeared in a really consistent way in El Dorado (1921), which was the first film of the movement to appear on our ten-best lists.

In 1922, the movement gained momentum with Gance’s monumental La roue. Many critics and historians consider this and Gance’s Napoléon masterpieces. I consider them more uneven, with brilliant stretches mixed in with melodramatic, sentimental, even occasionally maudlin scenes mixed in. Few people have seen all the surviving footage from La roue. The shorter versions available tend to eliminate the sentimental bits, which often run on and on. I’ve already voiced my opinions, favorable and less so, in the entry “An old-fashioned, sentimental avant-garde film,” posted when the longest version available on DVD was released by Flicker Alley.

I mentioned there that the footage cut from the shorter versions of the film seemed to be some of the sentimental moments. One such scene seems to me unintentionally risible. The hero, Sisif, is a veteran train engineer; he has suffered an injury that is slowly causing him to go blind. Unable to face turning his beloved engine over to a rival engineer, he ponders destroying it. Sitting on the engine, he asks whether it would not prefer being wrecked to being turned over to another driver. The replies to his questions are given as titles superimposed over the train:

This is, I think, representing Sisif’s delusion that the engine speaks to him, but I’m afraid it comes across as if the train is suddenly talking out loud. In a sound film it’s easy to understand that a sound can originate subjectively in the mind of a character. People don’t, however, tend to imagine sounds as written words!

There’s no question that La roue has some extraordinary scenes. The opening train wreck and its aftermath are justly famous, as is the accelerating editing in the scene in which Sisif drives his stepdaughter Norma, with whom he is secretly in love, into the city to marry another man; his agitation and thoughts of crashing the train are reflected by the increasingly shorter shots. And although it’s dangerous to make claims about any film having the first use of a given technique (usually someone will find an earlier one), Gance seems to have been the first to use stretches of single-frame editing. These occur at a moment when one character in a crisis situation (trying to avoid spoilers here) recalls a cluster of scenes from his past. Maybe the Soviet Montage directors would have come up with that idea on their own—but maybe not. Along with El Dorado, La roue helped define what were to be the main traits of Impressionism.

One thing I didn’t mention in my entry on La roue is the striking contrast between the romance plot and the many scenes shot around the train-yard, which were shot on location. They add a gritty realism that does much to make up for the melodrama—a realism that largely disappears in the final portion, when Sisif is transferred to a mountain location to run a funicular train.

Most of the French Impressionist directors, and particularly Gance, L’Herbier, and Delluc, were concerned to prove that cinema was an art form. Their films tended to be serious, poetic, and based more on in-depth psychological portraits than on the more action-oriented films of Hollywood. They were also clearly made by Artists with a capital A. Gance and L’Herbier liked to start their films with close-ups of themselves staring into the lens with artistic fervor. L’Herbier’s photos included autographs. The films were designed to appeal to an intellectual crowd, though Gance’s were also highly successful at the box-office. Other directors’ films weren’t hits, however, and as the decade progressed more of them played only in the ciné-clubs and art theaters that sprang up.

Another Impressionist film of 1922, Jacques Feyder’s Crainquebille, took a very different tack. I remember seeing Crainquebille decades ago and not thinking much of it, though it has long been considered a classic. Now, however, watching the 2005 restoration by Lenny Borger and Lobster Films, I think it’s much more interesting. That’s not surprising, given that the print I originally saw was probably the 50-minute American release version, and the restoration adds half again as much footage, bringing it to 76 minutes. (The Internet Movie Data Base lists the original Belgian release print as 90 minutes, so presumably what we have is still not complete.)

Crainquebille has been admired for its realism and for the performance of a well-known stage actor of the day, Maurice de Féraudy in the title role. Jérôme Crainquebille is an elderly vegetable peddler, and much of the film was shot in the streets and markets of Paris, sometimes using long lenses to capture scenes of crowds and passers-by, unaware of the camera’s presence. But what struck me upon seeing it again is that Feyder was trying to make an Impressionist film for ordinary cinema-goers, perhaps the working-class people who could relate best to Crainquebille’s situation and milieu.

True, the film has a prestigious pedigree, being an adaptation of an Anatole France novel and starring a famous theater actor. Yet the story is simple and told in a relatively straightforward manner. Most of the action arises from a misunderstanding: A gendarme, thinking Crainquebille has insulted him, arrests him. A leisurely scene shows the protagonist enjoying the unusual luxury of his prison cell: a comfy bed, free meals, a toasty radiator, hot and cold water in a pristine sink, and a floor clean enough to eat off. A working-class audience would probably find this wryly amusing.

More telling, though, is the fact that when the typical camera techniques of Impressionism are used, Feyder inserts explanatory intertitles just before the subjective shots occur. This particularly happens in the long central trial scene. When the gendarme steps up to testify, a title informs us, “In Crainquebille’s eyes the Constable looked as important as his testimony.” We see Crainquebille gazing forlornly off right front and then his point-of-view of the witness, looming like a giant over the courtroom:

Subsequently a passerby from the scene of the “crime,” Dr. Mathieu, testifies on Crainquebille’s behalf. A title informs us, “To Crainquebille this testimony seemed to carry little weight.” We see a similar pair of shots, with the witness a tiny figure in the midst of the court. Naturally Crainquebille is found guilty and goes off to two further weeks of free room and board.

The next scene begins with an intertitle, “Dr. Mathieu’s Nightmare.” We see Mathieu in bed and then are taken into his nightmare, which depicts the court as a stylized, hellish place with the judges fearsome figures who leap onto their desk in extreme slow motion. (I have no way of knowing what the source of these intertitles is, so I must simply assume here that they reflect what was in the original film.)

Such heavily signaled experiments wouldn’t in themselves make Crainquebille a real masterpiece, but at a time when Impressionism was just gelling as a recognizable style, it seems a laudable attempt to find a non-elitist way to use it. In addition, the shots of the market where Crainquebille goes each morning are quite lovely, taken from neighboring rooftops with telephoto lenses.

As to what was restored in this version, there is remarkably little information on the internet. My notes from an archive viewing of the shorter version in 1984 suggests that the entire opening sequence in the restored version is “new.” It consists of Crainquebille and other vegetable peddlers pushing their carts across Paris to the main market. They pass through a wealthy district, which is characterized with vignettes of rich people’s decadence. The peddlers then pass through a high-crime district, with police rounding up criminals and prostitutes. (The inclusion of prostitutes suggests why this scene was cut for the American version.) The shorter version begins with the market scene and leads quickly to a scene in which Crainquebille rescues a poor newsboy from bullies, and the the scene where he is arrested follows. The entire character of Dr. Mathieu, the sympathetic witness, was cut, so the short version has a briefer trial scene and no nightmare. The action that follows Crainquebille’s release from prison is the same as in the restored version.

Crainquebille is available as part of a set, “Rediscover Jacques Feyder French Film Master,” along with restored versions of two of his other major films of the period, L’Atlantide (as “Queen of Atlantis,” 1921) and Visages d’enfants (as “Faces of Children,” 1925).

Hollywood dramas: The somewhat old and the somewhat new

The two Hollywood films on this year’s list are very familiar Hollywood classics, so I won’t spend much time introducing them.

D. W. Griffith probably appears for the last time in our 90-year-ago lists with his historical epic, Orphans of the Storm. This tale of the French Revolution featured the last appearances for Griffith of Lillian and Dorothy Gish, whose first film roles had been in his American Biograph short, An Unseen Enemy, in 1912. They play apparent sisters, Henriette and Louise (though Louise is in fact adopted) living in a Normandy village. Louise becomes blind, but Henriette takes her to Paris in the hope of finding someone who can restore her sight. Upon arriving, they are separated and victimized, Henriette by the decadent nobility, Louise by the dishonest poor. Eventually they are caught up in the Revolution, and Henriette is nearly executed at the guillotine.

As in his best features, Griffith combines an ability to represent melodramatic stories of idealized, virginal heroines alongside naturalistic, convincing images of the poor:

Orphans of the Storm represents the lingering influence of the Victorian theater on Griffith. The slightly later Naturalistic strains of nineteenth-century literature are evident in the cynical narratives of Erich von Stroheim. His first film, and the most completely preserved, was Blind Husbands, featured in our 1919 ten-best list. As I said there, Blind Husbands is my favorite von Stroheim film, with its relative light take on attempted seduction, near marital infidelity, and retribution. Foolish Wives took the theme much further, with the director again playing the heartless rake, Count Wladislaw Sergius Karamzin. Rather than pursuing one vulnerable wife, he seduces every woman in sight, including a hotel maid and an invalid, bedridden girl (above whose bed a crucifix hangs, to make sure we grasp the sinfulness of Karamzin’s lust).

Von Stroheim famously reconstructed the casino and surrounding buildings of Monte Carlo, resulting in a budget overrun. Universal made the best of his profligacy by advertising Foolish Wives as the first million-dollar movie ever. (Whether it really was or not we shall probably never know.)

Although much of the film is fairly conventional, with shot/reverse-shot conversations, von Stroheim experimented occasionally. At the left below, he shoots into a small mirror as Karamzin secretly ogles the heroine, who is behind him, as she undresses. In a number of shots von Stroheim films through a scrim to give a canvas-like effect to a composition. Here the invalid girl whom the villain eventually tries to rape is seen with her doting father.

As with all of von Stroheim’s films after Blind Husbands, Foolish Wives was taken out of his hands by the studio and shortened considerably. Much of this was done by trimming the lengths of individual shots. The original film apparently does not survive, so it is impossible to assess the director’s style thoroughly, especially when it comes to editing. The revisions were not nearly as great, however, as with his 1924 film Greed, which was cut by well over half. Thus of all von Stroheim’s 1920s films, Foolish Wives is probably closer to what he intended than most. The standard version of the film (restored by the American Film Institute but not of sterling visual quality) is available from Kino in an edition that includes a 78-minute documentary, The Man You Loved to Hate, written by von Stroheim expert Richard Koszarski.

Hollywood silent comedy

Every year our list visits the great three slapstick comedians: Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd. Sometimes it’s all three, sometimes two. They have all been working their way through shorts to the great features of the 1920s. Chaplin made it there last year with The Kid. In 1922 he had a light year, reverting to two-reelers with The Idle Class and Pay Day, so we’ll skip him here and pick him up again later.

In 1922 it was Harold Lloyd who moved up to features with Grandma’s Boy. Not on a level with some of his later films, like Girl Shy (sure to be high on our 2014/1924 list), but a real charmer with some classic Lloyd routines.

Lloyd is undoubtedly best known for his “thrill” comedies like Safety Last (1923 and heavily favored to feature on this list next year), where he climbs a skyscraper. Still, his more typical roles in the features show him beginning as a timid or socially inept young man who gains courage or skill in the course of the narrative. In Grandma’s Boy, an amusing and touching scene introduces the hero as a perpetually frightened child, unable to stand up even to littler boys who steal his lunch. Once he has grown up, his diminutive grandmother manages to chase off an intruding hobo with her broom after the Boy (none of the characters is named) has failed do so:

Despite his timidity, the Boy has managed to attract a Girl, and a Lloydian string of gags occurs when she invites him and his thuggish Rival to visit her at home. Grandma polishes the Boy’s shoes with goose grease and dresses him in an antiquated suit with mothballs in the pockets. Once at the Girl’s house, the Boy attracts the unwanted attentions of a litter of kittens determined to lick his shoes. When the Girl reacts badly to the mothball-scented suit, the Boy hides the balls in a box of candy. This leads to a hilarious scene in which he and the Rival both accept some “candy” from the Girl and end up grimacing in sync and trying to smile every time the Girl glances at them.

As with many good classical films, almost exactly halfway comes a turning point: the sinister hobo has robbed a jewelry store and shot a man. The film’s second half becomes an extended chase in which the reluctant Boy is enlisted as a deputy. Thanks to a little psychological trick played by the Grandmother, he wins out.

Grandma’s Boy is available in the indispensable “The Harold Lloyd Collection,” one of New Line Home Entertainment’s finest achievements, or separately with some other features as Volume 2 of the same set, or even more separately with seven shorts from Kino.

Buster Keaton was still making shorts in 1922, but this doesn’t put him at a disadvantage in our list. Experts agree that of Keaton’s twenty starring shorts (after his work as sidekick to Fatty Arbuckle), the best are The Boat (1921) and Cops (1922). Both are strongly touched by the streak of surrealism that frequently shows up in Keaton’s work—as in the dream-within-a-film scene that forms the bulk of Sherlock Junior (1924).

In Cops, Keaton plays a young man trying to impress his beloved by making good in some fashion. He is duped by a crook pretending to be evicted, who sells him the furniture of a family moving house, along with the horse and wagon that has come to transport it. Taking off through the city with the furniture he intends to resell at a profit, Keaton finds himself in the midst of a police parade and innocently accused of throwing a bomb actually lobbed by an anarchist. Chaos breaks loose. No matter where our hero runs, everyone he encounters turns out to be a cop—including his sweetheart’s father and the owner of the furniture.

The film is full of wonderful sight gags. Keaton hangs his hat on the protruding hip bone of a scrawny horse, and he tries to make a mustache disguise out of a clip-on tie.

Cops is available in Kino’s collection of Keaton shorts and in its collection of most of the features and shorts. Also available in the UK in the Eureka! “Masters of Cinema” box set of all Keaton’s shorts.

Next year, Our Hospitality!

Documentary and storytelling

Although we’re not overwhelmed with admiration for our final two films, they demanded inclusion because they are recognized as canonical classics.

Nanook of the North has frequently been described as the first feature-length documentary. Here’s an example where it was dangerous to call something first. There is in fact at least one earlier, filmed at the opposite end of the Earth: Frank Hurley’s South (1919), a record of Ernest Shackleton’s famous shipwrecked expedition to the Antarctic. But Nanook found a much wider public and became a classic, while South disappeared until 1998, when it was restored by the British Film Institute.

Nanook also had the advantage of a charismatic central figure and his attractive family, a picturesque depiction of Inuit life, and a carefully scripted story that included moments of danger during a walrus hunt and humor during a visit to a trading post.

Still, the film has drawn criticism for its extensive manipulation of reality. “Nanook” was in fact an Inuk named Allakariallak, and the woman represented as his wife was not married to him. Scenes were staged, as when an already-dead seal was used in a hunt. Nanook expresses amazement at a phonograph, though he was already familiar with such devices. The Inuit had already adopted firearms for hunting by the time Flaherty filmed them, but he requested that they use spears instead.

As has been pointed out, however, Flaherty was trying to present a slightly earlier phase of the Inuit culture, preserving a lifestyle that was rapidly changing. Moreover, the documentary mode had previously consisted largely of actualities and travelogues, and there was little precedent for what Flaherty was doing. For decades after Nanook (originally subtitled A Story of Life and Love in the Actual Arctic), documentaries tended to be structured fairly explicitly as tales with entertainment value. In the wake of cinéma vérité, the issue of filmmakers interfering with their subjects and staging scenes has become controversial, but it was not a great concern in the 1920s.

If we accept the notion that this is a documentary with considerable manipulation, we can credit the film with conveying a good deal of information about the Inuit of a slightly earlier period. The igloo-building scene is interesting and informative, even if we know that the interior shots had to be made in an igloo actually open on one side to provide light for the camera.

Nanook of the North was restored and released by the Criterion Collection in 1999.

Although it also appeared in 1922, Benjamin Christensen’s Häxan tends not to get equal credit as the supposed first feature-length documentary. Perhaps that is because it barely qualifies as a documentary. It’s not clear what other genre or mode it belongs to, though it tends to be admired mostly by fans of horror films.

Häxan purports to be a lecture on the history of witchcraft. Its English title is Witchcraft through the Ages, though the original title means simply “Witches.” The first reel consists of a series of images from books both scholarly and sensational, showing ancient images of supposed witches or witch-like creatures. The claim is that witchcraft has been a universal concept in cultures throughout history. Whether this is true I can’t say, but the images shown of ancient Egyptian deities are not witches but protective figures.

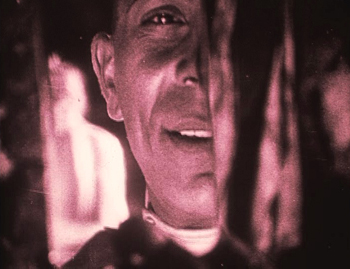

In the second reel, Christensen begins to illustrate the points being made with staged scenes of witches, surrounded by animal skeletons and other macabre items, many of them used in potions. Gradually the staged scenes develop into a narrative set in the Medieval or early Renaissance era, with one old woman being accused of witchcraft and tortured. She finally admits to being a witch and names her accusers as witches, and the imprisonment and torture spread. Like Dreyer in Leaves from Satan’s Book and Day of Wrath, Christensen condemns the very notion of witch-hunting and the hypocrisy and cruelty of the Church. Yet he shows a considerable fascination with torture methods—although in place of graphic scenes he presents static shots of contorted limbs and exhausted victims.

The true strangeness of the film, however, comes from its visualization of demons and devils as real beings. They conducting orgies, fly on broomsticks, and attempt to seduce people into evil and madness. Perhaps we are to take these images as what the Church assumes is happening, but there is no indication of that. One has to suspect that ultimately the educational “lecture” premise of the film, which is handled in a perfunctory way, is an excuse for staging scenes that range from quite powerful (see below) to merely cartoon-like, with people dressed up in crudely made costumes.

At the end the lecture mode returns, with an unconvincing series of comparisons of witchcraft with modern-day activities.

Whatever one thinks of the subject matter and its treatment, the film’s cinematography is extraordinarily beautiful.

Häxan has been restored by the Svenska Filminstitutet and was released on DVD with optional English subtitles. The restoration is available in the USA from the Criterion Collection, but I haven’t seen it or its extras. The Criterion package includes a version of the film narrated by William S. Burroughs. I haven’t seen it, but according to David’s memory of the croaky, world-weary voice-over, it adds another layer of weirdness to the proceedings.

For many years Häxan, as the only film by Christensen that was available for viewing outside archives, gave a rather distorted view of this director. Then his two earlier films, Det hemmelighedsfulde X (“The Mysterious X,” 1914) and Hævnens Nat (“Night of Revenge,” 1916) became more widely available. They were revelations—beautifully shot, tightly scripted, exciting movies. Those who don’t like Häxan should definitely watch these; they are quite different. Both are available on a single DVD from the Danske Filminstitut. The DVD has English intertitles, and the online shop is bilingual, Danish and English.

Häxan

The ten best films of … 1921

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

Kristin here:

To end the year, we’re continuing our tradition of picking the ten best films not of the current year but of ninety years ago. Our purpose is twofold. We want to provide guidance for those who may not be particularly familiar with silent cinema but who want to do a bit of exploring. We also want to throw in occasional unfamiliar films to shake up the canon of classics a bit.

Like last year, it was strangely difficult to come up with ten equally great films. There were some obvious choices, but beyond them there were a lot of slightly less wonderful items jostling for the other places on the list. The problem had several causes. Some master directors who routinely figure in our year-end ten choices had off-years. In 1921 D. W. Griffith released only one film, Dream Street, a notably weak item. (What I have to say about it can be found on pp. 108-113 of the British Film Institute’s The Griffith Project, Vol. 10.) Ernst Lubitsch released two films that seem like less interesting attempts to repeat earlier successes: Anna Boleyn (a pale imitation of Madame Dubarry) and Die Bergkatze (nice, and I was tempted to include it, but it’s less amusing than the Ossi Oswalda comedies, here and here). Cecil B. DeMille’s The Affairs of Anatol is not nearly as well structured as his earlier sophisticated rom-coms.

In other cases, films simply don’t survive. John Ford released seven films in 1921, all of which are lost.

Death comes calling, twice

Probably the easiest decision was to include The Phantom Carriage (also known as The Phantom Chariot), by Victor Sjöström. As I noted recently, the Criterion Collection has recently issued a beautiful restoration of it (DVD and Blu-ray).

When I first saw The Phantom Carriage, I was probably still an undergraduate. Given its reputation as a great classic, I was somewhat disappointed. No doubt it was partly the battered 16mm copy I watched, but the film is a bit formidable for someone not accustomed to the aesthetic of silent cinema–and especially of the great Swedish directors of the era. Its protagonist, played by Sjöström himself, is a thoroughly, determinedly unlikeable fellow, and the complex flashback structure can be a bit disconcerting on first viewing. But the effort to watch until one “gets” Sjöström is well worth it, since he’s undoubtedly one of the half dozen greatest silent directors.

The story opens on New Year’s Eve with Edit, a young Salvation Army volunteer, on her deathbed. She unexpectedly begs her colleague and mother to fetch the town drunk, David Holm, to her bedside. At the same time, Holm sits drinking in a graveyard as midnight approache. He tells two fellow inebriates the legend of the phantom carriage, the vehicle that picks up the souls of the  newly dead; it is driven each year by the last person to die at the end of the previous year. Holm then dies, and the carriage arrives, with its current driver ready to turn over the job to him. Flashbacks enact both the circumstances of how the heroine met Holm and the happy family whom Holm had alienated through his drunkenness.

newly dead; it is driven each year by the last person to die at the end of the previous year. Holm then dies, and the carriage arrives, with its current driver ready to turn over the job to him. Flashbacks enact both the circumstances of how the heroine met Holm and the happy family whom Holm had alienated through his drunkenness.

It’s a deeply affecting story, wonderfully acted and staged. In most scenes the lighting and staging are impeccable, and the famous superimpositions that portray the carriage and the dead are highly ambitious for the period and impressively executed. The filmmakers have managed to make the carriage, superimposed on real landscapes, appear to pass behind rocks and other large objects. In short, a film that has everything going for it.

Death himself appears in Der müde Tod (literally “The Tired Death,” often called Destiny, or occasionally in the old days, The Three Candles). Here the great German director Fritz Lang hits his stride, and you can expect him to figure on most of our lists from now on.

In Destiny (available on DVD from Image Entertainment) a young woman’s fiancé is killed early on. Death, a sympathetic figure who regrets what he must do, gives her three chances to find another person whose demise can substitute for her lover’s. The three episodes in which she tries take place in Arabian-Nights Baghdad, Renaissance Venice, and ancient China; each story casts her as the heroine and her lover as the hero.Things don’t go well, and Death actually gives her a fourth chance when she returns to the present.

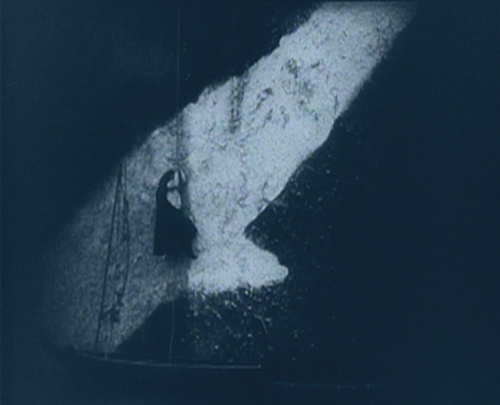

This was Lang’s first venture into the young German Expressionist movement, which had been launched the year before with Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. The style shows up only intermittently, perhaps most dramatically in the Venetian episode when the lover shinnies up a rope along a wall painted with a gigantic splash of light. (See bottom.)

Each film has a “happy ending.” I leave it to you to determine which is grimmer.

I’m turning over the keyboard to David now, to describe a film he knows better than I do.

More Northern European drama

Mauritz Stiller alternated urban comedies (Thomas Graal’s Best Film, 1917; Thomas Graal’s Best Child, 1918; Erotikon, 1920) with more lyrical dramas and romances set in the countryside (Song of the Red Flower, 1919; Sir Arne’s Treasure, 1919). Johan (1921) is in the pastoral vein. Its integration of landscape into the drama suggests it was an effort to recapture the production values that overseas critics had praised in Sjöström’s Terje Vigen (1917) and The Outlaw and His Wife (1918). Like the Sjöström films, however, Johan offers more than splendid spectacle; it’s the study of the undercurrents of a marriage.

At the core is a love triangle. The fisherman Johan is the somewhat thick-headed son of a domineering mother. He is fond of the girl Merit, whom he and his mother rescued as a waif and brought into their household. But this synopsis is actually skewed, because Stiller and the scriptwriter Arthur Norden have told the story in an unusual way.

At the core is a love triangle. The fisherman Johan is the somewhat thick-headed son of a domineering mother. He is fond of the girl Merit, whom he and his mother rescued as a waif and brought into their household. But this synopsis is actually skewed, because Stiller and the scriptwriter Arthur Norden have told the story in an unusual way.

We’re introduced to the couple by following the rogue Vallavan’s entry into the town; Johan seems almost a secondary character until Vallavan leaves. When Johan breaks his leg, Merit agrees to be his wife. Now we’re attached to her standoint and see her life of drudgery under the petty tyranny of Johan’s mother. Vallavan returns, and Merit falls under his spell. Taking her hand, he says, “I want to rescue you.” After she has fled with him, Johan clumsily wanders the rocky shore. “Will I ever see Merit again in this life?” The narrational weight passes to him as he decides to pursue the runaways.

Like Sjöström’s Sons of Ingmar (1918-1919), Johan presents marriage as a trap for unwary women. Our shifting attachment, from Vallavan to Merit and eventually to Johan, allows us to see the situation in many dimensions. As a sort of parallel, Stiller makes fluid use of the now solidly-established conventions of continuity editing. Vallavan’s seduction of Merit is played out in tense shot/ reverse-shot, and there’s an engrossing moment involving delicate shifts in point of view. When the bedridden Johan sees Merit leaving, after his mother has cast her out of the house, he must smash a window pane with his elbow in order to call to her. Stiller’s dynamic eyelines, direction of movement, and precise changes of camera setup here show that he had mastered the American style.

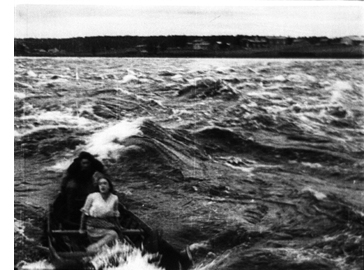

Alongside this finesse, there is still plenty of outdoor action, highlighted when Vallavan rows Merit away in the tumultuous river. Filmed from another boat, the actors are all but engulfed by the waves. It was presumably scenes like this that the parent company, Svensk Filmindustri, hoped would attract international attention. At this period Svensk, dominant in the local industry, was hoping to sell its films on a global scale. That ambitious plan failed, but it left us with many outstanding movies and soon brought Stiller, along with Sjöström, to Hollywood.

Johan is available on a Region 2 PAL DVD, coupled with Kaurismaki’s Juha, another adaptation of the Juhani Aho story.

The joys of small-town life

Last year I included two films by William C. deMille, the considerably less famous brother of Cecil B. The year 1921 saw the release of what is today his best-known film, Miss Lulu Bett. It was based  on the popular novel and play by Wisconsin author Zona Gale, who received her MA here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and in 1921 became the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for drama. The story centers around the heroine, a spinster who lives with her sister’s family, including her niece, nephew, and brother-in-law, Dwight Deacon. Dwight is a tyrant who delights in taunting Lulu over her unwed status, and the rest of the family treats her as a servant.

on the popular novel and play by Wisconsin author Zona Gale, who received her MA here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and in 1921 became the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for drama. The story centers around the heroine, a spinster who lives with her sister’s family, including her niece, nephew, and brother-in-law, Dwight Deacon. Dwight is a tyrant who delights in taunting Lulu over her unwed status, and the rest of the family treats her as a servant.

The return of the husband’s globetrotting younger brother Ninian after a twenty-year absence injects some life into the situation. Taking the family out to dinner, he realizes just how boring the family is (right), and to liven things up, suggests that he and Lulu perform mock marriage vows. Dwight realizes that the ceremony is legally binding, and, already attracted to Lulu, Ninian suggests that they treat it as a real marriage. Desperate to escape her dreary situation, Lulu agrees. The relationship proves agreeable, and Lulu declares that she will learn to love Ninian–when he reveals that he had previously been married, though he doesn’t know whether his first wife is dead (in which case he and Lulu are married) or alive (in which case they aren’t). Unwilling to take a chance, Lulu returns to the Deacons, who consider her disgraced and treat her even worse.

The film avoids melodrama. Ninian is not a villain; he’s kind to Lulu and sorry for the position he’s placed her in. It remains to Lulu to summon the gumption to leave the family and find her own happiness.The whole thing is told with restraint and little touches of humor that draw the viewer into a deep sympathy with Lulu’s plight.

Lois Wilson’s performance as Lulu is crucial in this. She is at once plain enough that we can believe she is in danger of becoming an old maid and pretty enough to plausibly attract the attention of the handsome local schoolteacher. Wilson’s most prominent role came two years later, when she starred as the heroine in James Cruze’s The Covered Wagon.

Miss Lulu Bett is the only one of William’s films available on DVD, paired with Cecil’s Why Change Your Wife? As so often happened, William seems to take a back seat to his famous brother, but the pairing is a logical one, in that William wrote the script for Why Change Your Wife?

Another small-town drama of the same year is Lois Weber’s The Blot. In 1981, when I was teaching a course on American silent film at the University of Iowa, I wanted to quickly demonstrate to the students that the silent period was not an era of exaggerated acting and naively melodramatic plots. I showed a double feature of The Blot and King Vidor’s Wine of Youth (1924). The latter portrays changing sexual mores through the story of three generations of the same family, with a young woman of the Roaring Twenties questions the necessity of marriage when she discovers that her mother is contemplating divorce. I think Wine of Youth (unfortunately not available on video) and The Blot convinced my class that silent films could be both sophisticated and subtly acted.

The “blot” of Weber’s title refers to the notion that people in professions depending on intelligence and education are poorly paid, while tradespeople and children from rich families are well off. The representatives of the underpaid are a college teacher, Prof. Griggs, and a young, idealistic minister. The parallels to recent events are striking. College professors may not be so badly paid as in the 1920s, but the move toward institutions of higher learning depending on adjunct lecturers has created a similar issue. In general, the income gap is familiar: the rich young wastrels taking Prof. Griggs’s course represent what we now call the one percent, while the professor and minister live on a much lower plane.

Weber’s drama is not quite this bald, however. Various levels of prosperity are represented. The professor’s family lives in shabby gentility, his wife grimly struggling to keep food on the table and his daughter Amelia, in delicate health due to a lack of nourishing food, working in the local library. Their neighbors are the family of a successful shoemaker, who live well but lack education. The shoemaker’s wife in particular resents what she perceives as intellectual snobbishness in the professor’s family and takes every opportunity she can to flaunt her comparative wealth.

Her son, however, has a crush on Amelia, as does the poor minister. Into this situation comes Phil West, the professor’s rich but indolent and mischievous student. Also attracted to Amelia, Phil for the first time encounters real poverty and is  shocked by it. As the plot develops, Amelia falls ill, and her mother’s increasingly desperate efforts to obtain the food necessary to nurse her to health become one of the main threads of the drama. To say that a large part of the action in the second half of the film centers on Mrs. Griggs’s temptation to steal a chicken from her neighbors might make the situation seem a trifle comic, but Margaret McWade’s remarkable performance vividly conveys the wife’s struggle in the face of real lack and her humiliations in the eyes of the shoemaker’s gloating wife. When Mrs. Griggs succumbs to temptation, the result is a brief but wrenching scene.

shocked by it. As the plot develops, Amelia falls ill, and her mother’s increasingly desperate efforts to obtain the food necessary to nurse her to health become one of the main threads of the drama. To say that a large part of the action in the second half of the film centers on Mrs. Griggs’s temptation to steal a chicken from her neighbors might make the situation seem a trifle comic, but Margaret McWade’s remarkable performance vividly conveys the wife’s struggle in the face of real lack and her humiliations in the eyes of the shoemaker’s gloating wife. When Mrs. Griggs succumbs to temptation, the result is a brief but wrenching scene.

The plot is remarkably dense and unpredictable. Every scene involves glances that lead to new knowledge or serious misunderstanding, deflecting the plot into new directions. Early on it is impossible to say which of the three young men Amelia will end up with, and even by the late scenes, when only two plausible romantic candidates remain, we have no idea which she will pick. As in many of Weber’s films, she does a bit of preaching about the social problem involved, but in The Blot she leaves this until near the end and gets it over quickly and fairly believably. The considerable but gradual change in Phil’s attitude toward education and the problems of poverty is also made believable. The prosperous neighbor’s change of attitude may seem a bit sudden, though it is somewhat motivated by a line early on.

But on the whole, even more than with Miss Lulu Bett, this is an absorbing story with characters for whom we care. Weber uses motifs as skillfully as any director in the early phase of the classical Hollywood cinema. Watch in particular how many different ways she uses the Griggs family’s cat and her two kittens: to demonstrate the family’s poverty, to be the main means of the neighbor lady’s spite, to introduce some comedy, and so on. Even more pervasive is the way that shoes become tokens of characters’ various social positions.

The Blot is available on DVD from Image. Those interested in Weber as a director should note that next summer’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna plans a retrospective of her work.

Which is best? Damfino.

In past year-end lists, we’ve watched Harold Lloyd, Charles Chaplin, and Buster Keaton creeping toward their great features of the 1920s. This year two of them move cautiously into longer films, and the other releases two more terrific one-reelers.

The Boat is one of Keaton’s most admired shorts. In it, he, his wife, and their two young sons build a boat, the Damfino, and unwisely launch it on the open ocean. Everything that can go wrong does: the life-preserver sinks, the anchor floats, and naturally a storm hits. The wife’s pancakes aren’t edible, but one temporarily patches a leak. Throughout the intrepid band carries on against all obstacles.

Less perfect but more dazzling and (perhaps) funnier is The Playhouse. The premise of a small variety theater creates an episodic, messy narrative, but it allows Keaton to play out a series of four “acts.” Initially we see Keaton buy a ticket and enter an auditorium where the audience, the orchestra, and all the performers are played by “Buster Keaton.” As one of the audience members remarks, “This fellow Keaton seems to be the whole show,” which is true in more way than one. The multiple images of Keaton were accomplished entirely in the camera, by cranking back the film with precise timing and uncovering a different part of the lens at each pass. The precision when one Keaton figure talks to or dances with another is amazing.

This all turns out to be a stagehand’s dream. (Keaton being the stagehand.) The multiplication motif returns as an act involving two pretty girls who happen to be twins–something Buster  doesn’t know, making his encounters with them ever more baffling. Later an orangutan escapes, and Buster dons make-up and costume to replace him. All hilarious stuff, though unfortunately the final act, a Zouave Guard drill, is the least funny one. Still, it’s a terrific film with a big dose of the surrealist quality that will run through the later shorts and the features.

doesn’t know, making his encounters with them ever more baffling. Later an orangutan escapes, and Buster dons make-up and costume to replace him. All hilarious stuff, though unfortunately the final act, a Zouave Guard drill, is the least funny one. Still, it’s a terrific film with a big dose of the surrealist quality that will run through the later shorts and the features.

The Boat is included on Kino’s disc of The Navigator and The Playhouse with their out-of-print DVD of The General. Still in print, however, is Kino’s eleven-disc set of the features and shorts. For those in the UK and other region-2 countries, Eureka! has a “Masters of Cinema” three-disc set, “Buster Keaton: The Complete Short Films 1917-1923,” which includes many of his earlier films with Fatty Arbuckle.

The year saw Lloyd and Chaplin make their first feature films, though both releases were still fairly short. I’m not really counting A Sailor-Made Man as one of the top ten of the year, since it’s a delightful but decidedly light item. Just another reminder that Lloyd is inching toward greatness.

Lloyd presents his “glasses” character as a brash young man who impulsively proposes to a rich man’s daughter. When the father demands that he get a job to prove his worth, Harold enlists in the navy. Highjinks ensure, culminating in a lively chase-and-rescue scene when the heroine gets kidnapped by a lecherous Arabian sheik.

Lloyd presents his “glasses” character as a brash young man who impulsively proposes to a rich man’s daughter. When the father demands that he get a job to prove his worth, Harold enlists in the navy. Highjinks ensure, culminating in a lively chase-and-rescue scene when the heroine gets kidnapped by a lecherous Arabian sheik.

The shipboard scenes allow Harold to get in some funny bits, mainly involving him trying to be tough and succeeding at first by sheer accident. Later, however, he is inspired by the heroine’s danger to become a real rescuer. It’s a sign of bigger things to come.

New Line’s Harold Lloyd boxed set is out of print, but you can still get the volumes separately. A Sailor-Made Man is in Volume 3, along with such delights as Hot Water and For Heaven’s Sake.

Chaplin’s first feature, The Kid, is a skillful blend of the rough-and-tumble slapstick that had characterized his early shorts and the sentimentality that would gradually become a more prominent trait of his films. A unmarried woman (played by Edna Purviance, the elegant beauty who made such a contrast with the Little Tramp in many of his films) abandons her infant in an expensive car which happens to get stolen moments later. Charlie finds the baby, and after numerous attempts to get rid of it–including a brief contemplation of an open storm-sewer grate–decides to raise it. The baby grows into the adorable and amusing Jackie Coogan.

Chaplin’s first feature, The Kid, is a skillful blend of the rough-and-tumble slapstick that had characterized his early shorts and the sentimentality that would gradually become a more prominent trait of his films. A unmarried woman (played by Edna Purviance, the elegant beauty who made such a contrast with the Little Tramp in many of his films) abandons her infant in an expensive car which happens to get stolen moments later. Charlie finds the baby, and after numerous attempts to get rid of it–including a brief contemplation of an open storm-sewer grate–decides to raise it. The baby grows into the adorable and amusing Jackie Coogan.

In the meantime, the mother has become a rich singer, and coincidentally she comes to the slums doing charitable work. The authorities eventually try to remove the Kid to an orphanage, and later a flop-house proprietor turns him in to receive a reward. Still, Chaplin doesn’t milk the pathos, and a happy ending duly arrives.

The Kid is available in a decent print along with A Day’s Pleasure and Sunnyside on the “Charlie Chaplin Special” DVD. Our recording off Turner Classic Movies strikes me as being slightly better quality, so you might keep an open to see if they reshow it. It was also announced this week that The Kid has been added to the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress.

Fuzzy movies, big and small

Soft-style cinematography had been tried in some films of the late 1910s, most notably in Griffith’s Broken Blossoms. But in the 1920s it spread. In Hollywood, it was mainly a technique for making beautiful images and especially for creating glamorous close-ups of actresses. In France, it was a way of tracking a character’s inner life.

Vicente Blasco Ibáñez’s 1918 novel, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse was a huge bestseller, and the first film adaptation in 1921, directed by Rex Ingram, was equally successful. To many, it is remembered for having made a super-star of its main actor, Rudolph Valentino. Anyone who has seen him as the caricatured Latin Lover of his later films will be pleasantly surprised to discover that the man could act, as could his leading lady, the lovely Alice Terry.

Ingram was the quintessential middlebrow director of the 1920s, doing big-budget, respectable adaptations of popular literature (e.g., Scaramouche, The Prisoner of Zenda). To me, Four Horsemen escapes the stodginess of the later films, at least to some extent (as does his other 1921 film, The Conquering Power). It and the other film in this section were borderline cases, chosen as much for their historical importance as their quality, perhaps, but definitely worth watching.

One of Four Horsemen‘s greatest strengths is its photography. Ingram worked consistently with one of the greatest cinematographers of the 1920s, John F. Seitz, who created glowing images of  sets and actors with selective lighting and all sort of means of softening the image. This film, more than Broken Blossoms, brought the soft style into vogue. It eventually culminated in the Dietrich films of Josef von Sternberg before a more hard-edged look came to dominate the 1940s.

sets and actors with selective lighting and all sort of means of softening the image. This film, more than Broken Blossoms, brought the soft style into vogue. It eventually culminated in the Dietrich films of Josef von Sternberg before a more hard-edged look came to dominate the 1940s.

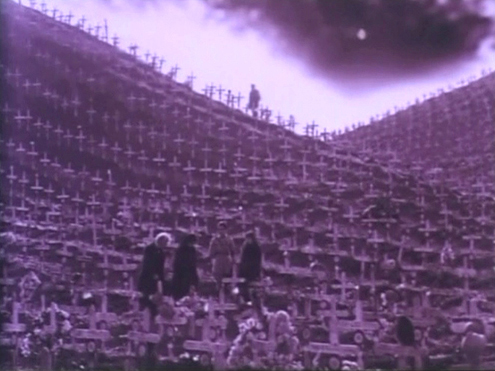

Four Horsemen was also an early entry in the anti-World War I genre of the 1920s and 1930s. Its final scene in a vast military cemetery of identical white crosses remains a powerful one. (See above.) Here, however, the Germans are still stereotypes, militaristic puppets with no redeeming features. Even that notion would gradually change, however, until nine years later All Quiet on the Western Front could recount the war from the German point of view.

Four Horsemen is available on DVD on demand from Amazon, supplied on DVD-R. In the same format, one can order it on a set with a documentary on Valentino. The reviews of the latter suggest that the visual quality is good.

(For more on this photographic style, see my “The soft style of cinematography,” in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, pp. 287-293.)

I’m not a huge fan of Marcel L’Herbier, and I’m not entirely sure that El Dorado is a full-fledged  masterpiece. But it has many virtues, and arguably it’s historically important as the first film of the French Impressionist movement to thoroughly explore ways in which camera techniques could convey perceptual and psychological states. It focuses largely on Sibilla, a singer-dancer who is the main attraction in a tawdry Spanish bar. She and some other women are performing as the story begins, but Sibilla is distracted by worries about her sick son. L’Herbier experimented with tracing her attention by placing gauzy filters over her face when she starts thinking of the boy. In the frame at the left, for example, she is in sharp focus when onstage, but as she passes into the backstage area, she goes fuzzy.

masterpiece. But it has many virtues, and arguably it’s historically important as the first film of the French Impressionist movement to thoroughly explore ways in which camera techniques could convey perceptual and psychological states. It focuses largely on Sibilla, a singer-dancer who is the main attraction in a tawdry Spanish bar. She and some other women are performing as the story begins, but Sibilla is distracted by worries about her sick son. L’Herbier experimented with tracing her attention by placing gauzy filters over her face when she starts thinking of the boy. In the frame at the left, for example, she is in sharp focus when onstage, but as she passes into the backstage area, she goes fuzzy.

In a way this is a somewhat silly, literal notion, and yet it’s exciting to see filmmakers exploring new devices relatively early in film history. Gauzy filters, distorting mirrors, slow-motion superimpositions, rhythmic cutting, and subjective moving camera were soon to be in common use by a small group of French directors. El Dorado was also the first film to be filmed within the Alhambra, which lends it considerable visual interest.

If we’re still writing this blog in 2019, our list will probably include the culminating film of the movement, and arguably L’Herbier’s best silent film, L’Argent.

Not many French Impressionist films are available in the U.S. If you have a multi-region player, El Dorado is paired with L’Herbier’s earlier L’homme du large (1920) on a French DVD.

Tigers and lepers and a mysterious yogi

We tend to think of serials as having many episodes and being low-budget additions to programs. That’s the American model, but in Europe things were different. Louis Feuillade’s serials are among the gems of the 1910s. In Germany, serials tended to have fewer episodes but bigger budgets–much bigger. Many were only two parts, most famously Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (coming next year to our top-ten list) and Die Nibelungen (coming in 2014). Lang had launched into serials with Die Spinnen (1919 and 1920). The two parts have terrific things in them, but Lang never went on to finish it.

He was, however, still collaborating on screenplays for director Joe May, who specialized in epic serials set in exotic countries and starring his wife, Mia May. Highly entertaining though these films are, they are largely forgotten, even by most lovers of silent cinema. Das indische Grabmal is the exception, though even now few have had a chance to see it. In 1996 it was shown at “Il Gionate del Cinema Muto” festival in Pordenone and was all too briefly available on an Image DVD (as The Indian Tomb) now out of print. Track it down if you can.

Full of the stars of its day, Das indische Grabmal is set largely in India, and its plot was inspired by the Taj Mahal. A ruthless maharajah (played with relish by Conrad Veidt) cloaks his cruelty under a veneer of European courtesy. He plots to shut his unfaithful princess (Erna Morena) in a beautiful tomb along with her lover (Paul Richter, better known to modern audiences as Siegfried). He calls in a famous European architect (Danish star Olaf Fønss) to build it, and the architect’s fiancée (Mia May), rightly fearing dirty work afoot, follows. One pit full of tigers and one of lepers lie waiting to endanger the visitors. The sets are beautiful. The Germans by this point could do them at full scale (above left) and as marvelously deceptive miniatures (above right). Das indische Grabmal is constantly entertaining and perhaps the best of its type, at least of the films we have access to.

Lang directed a two-part remake of this film in 1959. Both are good, but I prefer the silent one.

Some runners-up

As I mentioned, we had trouble narrowing down our list this year. Here are some others that could have replaced some of our prime choices. The German stage director Leopold Jessner adapted the play Hintertreppe (Backstairs). It’s a Kammerspiel, set in two apartments and the courtyard between them, and concerns a simple love triangle among a maid, her absent lover, and the postman who loves the maid so much that he forges letters from her sweetheart to keep her happy. Antti Alanen kindly reprinted my notes on the film here.

Carl Dreyer’s third feature, Leaves from Satan’s Book, remains one of the most widely-admired variants on the Intolerance formula of presenting thematically linked historical episodes. The dynamic final last-minute non-rescue shows that Dreyer learned a good deal from Griffith’s crosscutting too. Leaves is available on a Danish DVD with English subtitles and an alternate ending. Murata Minoru’s Japanese feature Souls on the Road, another exercise in complex crosscutting, and Feuillade’s polished L’Orphéline are solid runners-up as well. Neither is available on commercial DVD, as far as we know.

Destiny.

You are my density

DB here:

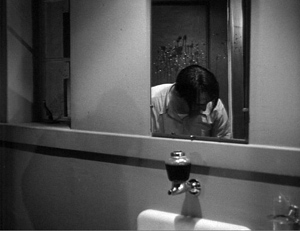

The mobster Joseph Rico is in protective custody; tomorrow he testifies against the big boss. But Rico fears reprisals, so he decides to escape. While a sleepy cop guards him in the washroom, he bends over the sink and rinses his face.

Turning so suddenly that water spatters on the mirror, he grabs the cop in an armlock and slams his head against the sink, just below the frameline.

Rico turns to the window to make his escape.

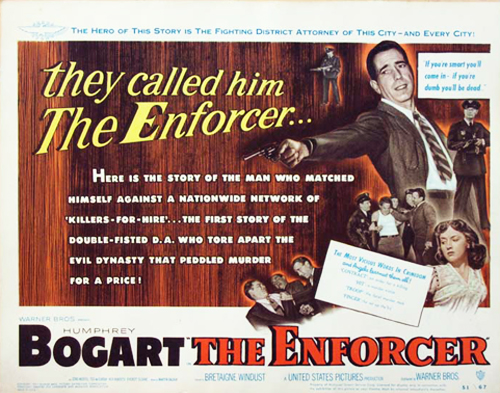

What interests me in this passage from The Enforcer (1951) is not just what happens in the mirror but also what happens on it. While Rico belabors the cop’s head, we’re given a chance to notice the splash of water that hit the mirror when Rico whirled to the attack. While the action is moving forward, we’re reminded of what had triggered it.

We get a sort of parallel reminder in the next scene, when we see the wounded cop again. He’s sporting a big bruise on his left temple, a souvenir of Rico’s assault.

Pfui. Details, you might say. Or you might (correctly) instance this as another case of Charles Barr’s enlightening notion of gradation of emphasis. But it’s worth getting a little more specific, because even this simple scene (by non-auteur director Bretaigne Windust) offers us something to think about, and something for today’s filmmakers to try.

Most films today don’t fully exploit the visual dimension of cinema. True, we have dazzling CGI and fancy camera moves. But when it comes to less flamboyant scenes, directors have limited their options by relying too much on stand-and-deliver and walk-and-talk. There are other aspects of visual storytelling that today’s filmmakers neglect. One aspect is the possibility of gracefully moving actors around the set in a sustained fixed shot. A specific tactic I’ve mentioned before is the Cross, and another involves ways to get people into a room. The option I’m going to sermonize about today is what I’ll call scenic density.

By scenic density I mean an approach to staging, shooting, and cutting in which selected details or areas change their status in the course of the action. I don’t count the bustle of background business, all that street traffic that is so much pictorial excelsior in our movies. Nor do I refer to stuffing the setting with desk and kitchen flotsam, allusive pop-culture posters, and the other distinctive “assets” that will be exploited when the film’s world gets transposed to a videogame. I mean something more expressive and intriguing.

Using it up

Go back to the Enforcer scene. The shot’s composition creates a delimited zone of action. The guard cop is framed tightly in the mirror. When the fight breaks out, it’s initially framed in that mirror–a narrowing of visual importance. Moreover, the shot is designed to highlight the spatter on the mirror. It’s fairly prominent, stuck near the center and, providentially, in the spot that the cop’s head initially occupied. The lighting picks out the drips, and in a shot where the figures move in and out of frame, there isn’t an equally constant center of interest. We’re probably concentrating on Rico’s punishing of the cop, but the dribbles of water remain prominent enough to claim our interest, especially when Rico passes out of frame.

So here’s my first condition for scenic density: the shot keeps several items of dramatic significance salient in the composition.

This technical choice asks the filmmaker to think of the frame as a field of dynamic masses and forces. Such an idea was part of the aesthetic of “advanced” European and Japanese silent cinema of the 1920s. Many directors explored this dynamism, often aided by low angles and wide-angle lenses. Here are examples from Eisenstein’s Old and New and Murnau’s Tartuffe.

This pictorial density became especially prominent in American cinema during the 1940s, when low angles, wide-angle lenses, and locations and smaller sets encouraged cinematographers to pack their compositions snugly, as in this shot from Panic in the Streets.

Boris Kaufman, cinematographer for Jean Vigo and Elia Kazan, summed up the principle:

The space within the frame should be entirely used in the composition.

Since cinema is a time-bound art, however, the salient elements in the shot could and should change. But if the frame space is wholly “used,” what room is there for change? The only options are to have the using-up elements shift position, or to reveal that the frame isn’t used up.

Vivid instances, also from the 1940s, can be seen in Anthony Mann’s work, both with and without John Alton. Generally, Mann used the new fashion for depth composition, especially big foreground elements, to heighten scenes of violence. Physical action becomes more aggressive if people rush the camera and halt in tight close-up, especially because wide-angle lenses tend to accelerate movement to the foreground. Mann thrusts violence abruptly to the camera with an almost comic-book effect, as when the club owner is shot in Railroaded, or a man is flung to the floor in Raw Deal.

Even when this in-your-face tactic isn’t employed, the Mann films find ingenious ways to develop what seem to be completely locked depth compositions. In Border Incident, Ulrich confronts the Mexican government agent Pablo, disguised as a Bracero. A looming depth shot is followed by a reverse shot displaying a compact composition.

Is the frame space fully used? The second shot above is opened up when Ulrich leans forward to sock Pablo, creating a vacant spot on the far right for Pablo to fall into. The shot is emptied and re-filled, dense once more.

Memories, memories

Aha, you may be saying. Density just refers to squinchy, fussy shots from an era that favored cheap flash. No. The Enforcer shot isn’t all that cramped. Of course the blank, unchanging walls serve to highlight the mirror-reflected fight and the water dribbling down the glass, but you can imagine how much more jammed and skewed Mann’s treatment of Rico’s escape would be. As for the flashier depth, I just needed some clear-cut cases of density, examples in which details and spatial zones become starkly salient. Now I want to suggest that scenic density can be achieved in something more spacious, even monumental. That has to do with time and memory.

Part of what gives the Enforcer shot its interest is the superimposition of two moments of action in a single space: Rico’s diversionary turn from the washstand, recorded in the splash he made on the mirror, and the struggle taking place a few seconds later. A further trace of that struggle and that splash is visible in the bruise on the cop’s head in the next scene.

That dripping spatter can stand in for the second quality of spatial density I want to highlight: Its capacity to coax us to recall earlier action in the locale. Characters leave their marks and spoors in the space, and those get activated as memories. Unlike the slick surfaces of today’s settings, in classic films the settings can bear the impress of human transit, leading us to recall bits of behavior and emotional states. Let me illustrate from Lang’s Hangmen Also Die (1943).

It’s Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia, and Gestapo Inspector Ritter is questioning Mrs. Dvorak, the vegetable seller who could identify the woman who misled the officers pursuing an assassin. Torture, or at least what we think of as torture, hasn’t started. She is simply standing in front of his desk as he brandishes his riding crop in the manner of a good movie Nazi.

When Mrs. Dvorak denies knowing the woman, Ritter taps the back-rest of the chair. It simply falls off, and we realize it’s not fastened to the chair.

Ritter says, “Pick it up again.” Now we realize that intimidation has been applied for some while; Ritter has made the woman stoop to replace the back-rest many times. She does so again as the camera tracks back. This is nicely detailed too. She starts to pick it up by bending over, finds the effort too painful, and then goes to her knees to pick it up–just as Ritter taps his riding crop against her hand, a teacher gently chiding a slow pupil.

As Mrs. Dvorak rises to put the piece back in place, the camera pans slightly right to pick up the woman bringing in a tray. Happily Ritter sniffs the coffee jug and resumes questioning the old woman.

Cut to a shot of her by the chair. “Let’s start from the beginning,” says Ritter, offscreen. Unthinkingly Mrs Dvorak starts to rest her hand on the loose slat, forgetting that the top slat is unattached. It’s a natural response. She’s been standing there for a long time and would like something to rest on, and the chair is temptingly close. (Presumably, that’s its purpose, to taunt the unwary prisoner forced to stand a long time.) Remembering just in time, she yanks her hand away. If she knocks the back-rest off, she’ll just have to pick it up again.

Cut to Ritter. “Don’t be nervous, Mrs. Dvorak. I’m prepared to—”

Cut to Mrs. Dvorak. As he continues, “–devote to you all of tonight,” she forgets herself again and relaxes her hand, this time on the back-rest. It falls off, making her start.

She looks up as Ritter says, offscreen: “Even longer if necessary.” Cut to Ritter, gesturing with a piece of sausage and saying, coaxingly, “Well?”

Slowly she goes to her knees again as the camera tracks in on her.

Back to Ritter: “That’s the girl.” Back to her, rising in pain to replace the back-rest.

The scene concludes with Ritter reminding Mrs. Dvorak that she’s in Gestapo headquarters. She acknowledges that she doesn’t expect to leave without giving information. He starts his questioning all over again as the scene fades out.

This quietly suspenseful scene establishes a bit of furniture as a key prop. Once the faulty back-rest is marked for our notice, we’re expected to remember that it’s a means of intimidation–something that Mrs. Dvorak, in her anxiety about refusing to aid the Nazis, twice forgets. Lang’s shots, simple and uncrowded, makes the chair, like the spattered mirror in The Enforcer, preserve the trace of human activity. Yet it’s more acutely integrated into the scene’s drama than the mirror, and remembering how it was used earlier makes us wait tensely to see how it will be used again.

Long-term density

Several scenes later, the Nazis threaten to kill four hundred Czech hostages if the assassin isn’t turned over to them. Mascha Novotny has set out for Gestapo headquarters to denounce the man she helped, but she changes her mind and decides not to betray her country. She will only plead for her father’s life. Once more we’re in Ritter’s office.

Centered in the frame, standing out as a pale oblong against the grayer background, the fateful chair is made salient during Mascha’s conversation with Gruber. I suspect there’s a sort of spatial suspense here–will she move to the chair and dislodge the precarious piece of wood?–but more important, I think, is the fact that the chair ineluctably reminds us of Mrs. Dvorak and her quiet resistance to pressure.

Ritter leaves to consult his superiors. When he comes back, a new composition keeps the chair prominent and lends a new centrality to the clock on Ritter’s desk, surmounted by a snarling cat or something like it. (It’s visible in shadow in the earlier scene with Mrs. Dvorak.) But now the camera arcs to minimize the Dvorak chair and show the beast and Ritter targeting Mascha.

Soon enough, as if to make sure we remember, Mrs. Dvorak is brought back in, having undergone serious torture. The camera positions reactivate our memories of the earlier scene.

As she continues to lie to protect Mascha, Mrs. Dvorak never touches the chair. Although she has been tortured, she seems wearily defiant, as if her refusal to aid the Nazis has given her some strength: no need to lean on the chair now. As a final cue to our memories, Lang has Ritter play once more with his riding crop, letting its shadow fall on her heart.

The threat is clear: For lying, the old woman will pay with her life.

The chair reappears in a later scene, but I’d argue that then it serves more as a pointer to another prop. The resistance movement fights back by framing Czaka, a beer baron sympathetic to the Nazis, as the assassin. Lang could have explicitly recalled the questioning of Mrs. Dvorak by having Czaka lean on the slat and knock it off. Instead, the composition makes Ritter’s clock more important than it was in earlier shots. As Czaka tries to defend himself, the framing blocks our view of the chair but emphasizes the snarling catlike creature on top of the clock. And the chair has shifted a little off and become a bit darker; it’s no longer as salient.

This cluster of scenes from Hangmen Also Die illustrates how scenic density can add layers to a film. One scene recalls another not only by similarity of situation and locale but by tangible marks left on it by earlier action. Having seen Mrs. Dvorak subjected to Ritter’s oily intimidation, we generally expect something like it to be applied to Anna. This conventional situation is given a rich, concrete presentation by the repeated camera positions and the simple chair that, unmoving, enters into the drama.

Of course as a Hollywood director, Lang was pressured to reuse sets and camera setups. That saved money and time. But he turned such repetitions to his advantage by letting certain objects come forward at crucial moments. They not only become part of the drama but prime us to remember them, and what they revealed, in ensuing scenes. And even though Lang never pursued the aggressive, packed deep-focus of other directors working in the 1940s, he shows how roomier, less pressurized compositions could still be charged with echoes of earlier bits of behavior.

Is this sort of visual-dramatic economy, calling on precise memories of concrete actions, lost in today’s American cinema? I suspect it is.

In studying Hangmen Also Die, I was curious about a perennial problem. Was the byplay with the chair a Lang invention on the set, or was it some version of the script, or in the original story by Lang and Bertolt Brecht?

The film didn’t have a secret script, as the poster says, but the sources do remain a bit obscure. A draft of the original story signed by Lang and Brecht, in that order, exists. It indicates only that the greengrocer, called Frau Blaschke, is subjected to eight hours of “the usual Gestapo brutality” and refuses to identify the girl. There were other drafts of the screenplay, but I don’t have access to them, if they exist, and standard sources on Brecht in Hollywood don’t mention this scene’s details.

Somewhere along the line, though, the chair-back business was concocted. I found the shooting script signed only by John Wexley (Brecht claimed that he was robbed of credit) and annotated in pencil, perhaps by Lang. That script indicates that Ritter’s room contains “a vacant chair with its seat close against desk.” and Mrs. Dvorak is standing beside it as the scene begins. Much of the dialogue is the same , with some slight changes notated in pencil, possibly by Lang. But the camera movements indicated are different from those in the final film, and more importantly so are the actions. After Mrs. Dvorak claims that she doesn’t know the woman who helped the assassin, we read the following. I indicate pencil notations with {}.

In her fatigue, she places hand on back-rest of chair. But its dowels are loose and back-rest clatters to the floor.

RITTER (saccharine): Pick it up, Mrs. Dvorak.

CAMERA MOVES IN CLOSE as she obeys, stooping with painful fatigue–she has done this many times tonight.

RITTER: Now put it back in place, Mrs. Dvorak.

(She does so)

As Ritter questions her:

MED. SHOT – MRS. DVORAK. Without thinking, she is about to place hand again on loose back-rest–when she remembers and jerks back.