Archive for the 'Directors: Lang' Category

METROPOLIS unbound

Fritz Lang has created a lot of pretty pictures and has discovered the astonishing talent of Brigitte Helm. I cannot blame him for not being able to cut the quantity of ideas in individual scenes mercilessly enough (the water catastrophe, the duel), but instead repeatedly trying out new lighting and angles. This time the film’s qualities lie precisely in these efforts: and if the viewer knows how to make the best of something, he will derive pleasure from these images.

Rudolf Arnheim, review of Metropolis, 1927.

Along with La Roue and The Battleship Potemkin, Metropolis (1927) is one of the great sacred monsters of the cinema. Many versions circulate, and restorations never seem to stop. A beautifully restored, though incomplete, version was premiered in Berlin in 2001. This is the basis of the most authoritative DVD releases. By now, however, everybody has heard about the 2008 discovery of a significantly longer version in Argentina, a 16mm preservation copy drawn from a scratch-infested 35 nitrate original.

Since 2008 a team at the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung has been at work adding material from the Argentine version to the earlier one. Kristin and I have written earlier entries (here and here) tracing the progress of the restoration, and the team have produced a detailed website explaining their work. The result made its world premiere at the Berlin Film Festival earlier this year, and an exhaustive exhibition about the film has been running at the Deutsche Kinematek in Berlin.

Now I’ve seen it, at a screening during the Hong Kong International Film Festival. Frank Strobel, a member of the restoration team, conducted the Hong Kong Sinfonietta, and another collaborator, Martin Koerber, curator at the Deutsche Kinematek, was present to discuss the restoration process. A handsome booklet, cosponsored by the Goethe-Institut of Hong Kong, provided a lot of background. The film was projected digitally, but at very high resolution and looking quite crisp. I had a front-row center seat. I had a swell time.

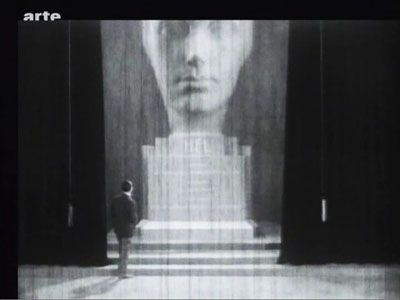

Metropolis has never been my favorite Lang of the period, but this version makes the strongest possible case for the film. It’s hard to dislike its shameless, preposterous ambitions, its stew of biblical and modern ingredients, its bold architectural vistas, and its trancelike characterizations. Also, people running crazily about in gargantuan spaces can usually hold your interest.

I just met a girl named Maria

All [the American editors] were trying to do was to bring out the real thought that was manifestly back of the production and which the Germans had simply “muffed.” I am willing to wager that “Metropolis” as it is seen at the Rialto now is nearer Fritz Lang’s idea than the version he himself released in Germany. . . . There was originally a very beautiful statue of a woman’s head, and on the base was her name–and that name was “Hel.” Now the German word for “hell” is “hoelle” so they were quite innocent of the fact that this name would create a guffaw in an English speaking audience. So it was necessary to cut this beautiful bit out of the picture . . . .

Randolph Bartlett, The New York Times, 13 March 1927

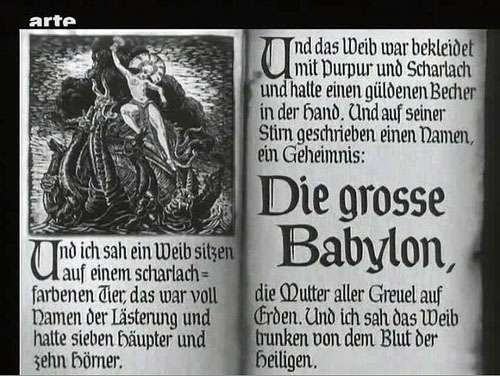

The new version gives the film a better narrative balance. Somewhat surprisingly, the plot hinges on one of the oldest and simplest narrative devices: mistaken identities. The overlord Fredersen engages the crazed scientist Rotwang to create a mechanical Maria who will lead the workers astray. Rotwang takes the occasion to avenge himself on Fredersen by having his robot urge the workers to destroy the machines. Two Marias, then–actually more, if you count the robot Maria’s incarnation as the Whore of Babylon in the Yoshiwara Club.

Thanks to the Argentine footage, we now know that another major character doubling involves Freder. At the start of the version we all know, Freder is visited by Maria and a flock of children. Upon seeing her radiant charity, he becomes suddenly convinced that he must join the oppressed workers, his “brothers and sisters.” Helping them has become his destiny. He gains an ally in Josaphat, an employee whom his father has brusquely fired. Descending to the cavernous machine halls, Freder switches identities with Georgy, a worker who returns aboveground to live Freder’s life. Freder wants him to go to Josaphat’s apartment, where they will meet. But the Thin Man, a long, leering hireling of Freder’s father, is charged with trailing Freder.

Stretches of the Thin Man subplot are missing from the previous version, but now we can see that Georgy/ Freder is a sort of early counterweight to the Maria/ Maria parallels. As in the latter case, the switch leads to misunderstanding, with the Thin Man following Georgy to the club and eventually to Josaphat. The Georgy substitution also allows Harbou and Lang to introduce the Yoshiwara Club early, but teasingly, in a rapidly dissolving montage. Only later will we get a good look at the delicious degeneracy inside.

As Martin Koerber indicated in several remarks, the older, most common version of Metropolis turns it into a science-fiction film, since it puts the robot Maria at the center of the plot. Just as important, though, is Freder’s plan for overturning class oppression, something fleshed out in the Georgy/ Josaphat material. Other new footage puts the relationship between Fredersen and Rotwang in a new light. We now see that Rotwang was in love with Fredersen’s wife Hel, and he has constructed not only a huge bust of her but also a “mechanical man,” outfitted with a distinctly female anatomy, as a sort of Hel substitute.

Fredersen diverts Rotwang’s plan to the purpose of mimicking Maria. So we get another doubling: Freder’s mother Hel becomes the firmware for the robot Maria through the machinations of two father figures. (Freder will kill one and redeem the other.) In all, the new footage yields a play of eerie Freudian substitutions.

The 2010 restoration also establishes the film as consisting of three large-scale movements. The first section, “Prelude” (Auftakt), runs a bit more than an hour. It shows Freder joining the workers and his father planning to have the Thin Man follow him. This part also introduces Rotwang, establishes Fredersen’s order to make a robot Maria, and ends with Rotwang’s capture of Maria. A second part, called “Intermezzo” and lasting about thirty minutes, is devoted to intertwining the Freder/ Josaphat plot with the creation of the robot Maria. The section more or less climaxes with a demo of the new Maria, dancing sexily at the Yoshiwara.

In “Furioso,” everything builds to a climax across a remarkable fifty minutes. The cloned Maria leads the workers to destroy the machines, fulfilling Rotwang’s plan to avenge himself on Fredersen, while the real Maria escapes from Rotwang’s compound during a fight between Rotwang and Fredersen. (We’re still lacking some of this footage.) At the same time, Freder and Josaphat converge on the underground city. The workers’ smashing of the machines triggers a flood from which the children must be saved. At the finale, during a hand-to-hand struggle with Freder, Rotwang falls to his death. There follows the famous epilogue in which Freder, “the Mediator,” must bring together hands (the foreman Grot) and head (the capitalist Fredersen).

Fluidity and freedom

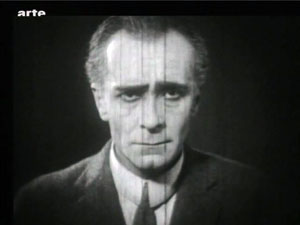

This delirious fable is rendered with unrelenting zest. Lang has now perfected his breathless version of silent-film narration. He relies on simple, immediately graspable compositions, rapid crosscutting among different plotlines, and a dynamic approach to analytical editing.

In the late 1920s, many American films became more heavily dependent on intertitles; it’s as if directors were anticipating talkies. But of Metropolis’s over 1800 shots, I counted only 26 expository titles and 156 dialogue titles—in a film running nearly 2 ½ hours. Lang plunges us into each scene with no fuss, and once we’re there, a smooth continuity carries us from shot to shot. Confronting the seven deadly sins in the cathedral, Freder turns away, twisting Georgy’s cap in his hands as he exits the frame.

Cut to the main area of the cathedral, and Freder is still twisting the cap as he enters the frame. (Like other shots from the Argentine version, this is slightly reduced because of the 16mm source.)

He lifts the cap, and we get his point of view on Georgy’s name and number.

Cut to the Yoshiwara nightclub closing, as Georgy steps groggily into the street.

Here the new footage lets us see that Lang is exploiting the sort of verbal and imagistic hooks he had developed in earlier films: from Georgy’s cap to Georgy himself, with no need of an intertitle to take us to the new scene.

Lang’s freedom of camera position is typical of late silent cinema, but he deploys his angles with characteristic precision. As usual in Europe, Hollywood-style continuity isn’t completely adhered to—there are some crossings of the 180-degree line—but Lang is careful to keep us oriented to the action through eyelines. This allows great flexibility in camera placement.

Fredersen is dictating to his secretaries while Josaphat is monitoring prices. A vast establishing shot shows all of them.

Fredersen’s pacing around his office allows Lang to introduce a new area around the window and the desk.

Now pacing in the center of the office, Fredersen pauses in his dictation and Freder bursts in behind him.

But Fredersen, who’s already holding up one hand as he speaks, simply twists his wrist, and this silences his son.

The shot approximates Freder’s point of view, but Lang gets a bonus from it. The sharp change of angle makes the imperious hand (and not, say, Fredersen’s expression) the compositional focus of the shot. In fact, this sort of hovering hand will become part of the characterization of Fredersen, and Lang will stress it through, once more, energetic changes of angle.

And still later, the framing will spotlight Freder’s pointing finger by pushing it to one zone on the far right of the shot.

Lang’s concise handling of such small actions forms a delicate counterbalance to the mass movements elsewhere in the film. Perhaps for him, both gestures and crowd scenes are merely two ways of creating a geometry that can activate every area of the screen.

The carefully controlled freedom of spatial construction is facilitated by one of Lang’s favorite tactics: shooting from directly on the axis of character interaction. (No, Wes Anderson didn’t invent this.) Lang in effect sets the camera between the two characters so that they stare out at us, as if mesmerized. The technique is most memorable in the scene in which Freder is confronted by Maria and the children.

Again, though, the Argentine material brings more instances to our attention.

Putting the camera on the axis allows Lang leeway in changing his angles. From a shot on the center line, you can cut to pretty much any other area of space.

Lang’s crisp visual narration comes to a climax in the well-named Furioso section. As the action ramps up, the characters rush from spot to spot, hurling themselves into the frame and then abruptly halting to hold the composition.

The extreme case is the robot Maria, whose head and limbs jerk puppetlike from one position to another.

In all, Lang’s precise, almost diagrammatic visual style rushes us through the film’s wild plot and dazzling architecture. An emblem of precision in the service of slightly demented material might be that memorable close-up of the robot Maria: One eye staring out normally, the other half-closed, and the mouth half-twisted in a leer, as if the circuitry in the skull was failing.

A little encyclopedia

Martin Kroeber, Togichi Akira, Winnie Fu, Sam Ho, and Wong Ain-ling discuss preservation and restoration at the Hong Kong Film Archive.

In a Q & A after the screening, Martin Koerber and Frank Strobel shared information about the version. They and their colleague Anke Wilkening could publish a whole book about the restoration, but here are some highlights, drawn as well from Martin’s comments at a lengthy seminar at the Hong Kong Film Archive.

*Sources for information about the premiere version include a copy of the script (helpfully marked with reel ends and calculations about running time), censorship cards recording the credits and intertitles reel by reel, Gottfried Huppertz’s musical score, and thousands of production stills.

*Using these materials, earlier researchers were able to create a sort of mosaic of the version that premiered in Berlin in January 1927. The resulting study film embedded long swathes of blank footage as place-holders. The fact that the Argentine shots fitted in neatly proved the validity of that edition. This study film may be ordered on DVD at nominal cost by educational and research institutions.

*What’s still missing? Some shots in the Argentine version may have been censored; we’re missing a bit in which Georgy, at liberty in a cab, sees a woman baring her body. Also lacking is nearly all the fight between Rotwang and Fredersen, which enables Maria’s escape. In addition, the Argentine print lacks a scene showing a monk preaching in the cathedral, which yields some apocalyptic images.

*If the film plays fast for contemporary tastes, don’t blame the restorers. This version runs at 24 frames per second. Actually, for the 1927 premiere the film was run even faster. The score includes passages accompanying missing footage as well as over a thousand synch-points for specific onscreen action. On the basis of this evidence, it seems that the film was designed to run at about 28 frames per second. This reminds us that silent-film running speeds were far from standardized, and they sometimes exceeded the 24 fps that would be established for sound film. (For more on this matter, go here and scroll down a bit.) In addition, Frank mentioned that in theatres with orchestras, the conductor could regulate the speed of the film with a dial set into the podium.

*Why insert the cropped 16mm footage in such obvious fashion? Couldn’t the framelines be adjusted to match the surrounding 35mm material? Yes, but this slight blowup of the footage would falsify the shot scale of the original footage and not match comparable shots in the 35mm footage. Moreover, Martin pointed out that because not all the scratches and fuzziness of the 16mm material could be purged, it’s better to let these stand stand out somewhat as evidence of the vagaries of film history–like leaving some damage visible in historic buildings.

*Why is the restoration in black and white, since most silent film restorations are in color? Lang was opposed to tinting and toning, so Metropolis premiered in black and white. This caused a debate among critics, some of whom considered it a promising departure from contemporary practices of coloring scenes. The tinted versions that one can occasionally see are likely export versions colored at the request of distributors in particular markets.

*Although future screenings of the 2010 version are to be accompanied by other ensembles devising their own music, there’s a powerful case for retaining Huppertz’s original score. It reflects the filmmakers’ intentions, and its Wagnerian romanticism and modern rhythms are enjoyable simply as music. Just as important, Huppertz designed his score around leitmotifs that, as in opera, can call to mind characters who aren’t onscreen at the moment.

*Metropolis, Martin argued, is too often considered simply a late Expressionist film or an early science-fiction effort. Now we can see that it’s much more: “a compendium of everything in the air in 1927 Germany.” It brings together political ideas, debates about class society and urban life, current trends in the fine arts, acting styles, and cinematic experiments. It owes a great deal to the “monumental” films of the late 1910s, such as Joe May’s Herrin der Welt (1919), but it’s also a synthesis of what filmmaking had become since then. “It’s a little encyclopedia of 1927 cinema. . . . There’s something in it for everybody.”

To see the restoration with the stirring score, vigorously conducted by Frank, was a high point of my Hong Kong trip and indeed of my filmgoing year.

This version of Metropolis was simulcast, if that’s the right word, on 12 February by Arte during the premiere at the Berlin International Film Festival. My frames are taken from that broadcast version; hence the bug. The restoration will be screened on Turner Classic Movies in the fall, and then released on DVD in the US by Kino International.

The epigraph quotation from Arnheim comes from Film Essays and Criticism, trans. Brenda Benthien (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997), 119. The article about the US cut of the film, which became widely seen around the world, is Randolph Bartlett, “German Film Revision Upheld as Needed Here,” New York Times (13 March 1927), X3.

Thanks to Martin Koerber for an abundance of information. For further reading, he recommends Erich Kettelhut’s memoirs on designing and filming the project, Der Schatten des Architekten (Munich: Belleville, 2009), ed. Werner Sudendorf, with many documents from sketches and photos; and the Deutschen Kinemathek exhibition catalogue, Fritz Langs Metropolis, ed. Franziska Latell and Werner Sudendorf (Munich: Belleville, 2010). You can get a sense of the tangled history of the versions of the film from Martin’s article in the latter volume, which includes a detailed account of the digital restoration. An earlier version of his piece, keyed to the 2001 version, is available as “Notes on the Proliferation of Metropolis,” in Preserve Then Show (Copenhagen: Danish Film Institute, 2002), 128-137. The Metropolis exhibition runs through 25 April.

A special thanks to Lee Tsiantis, Langian extraordinaire.

Things we like of late

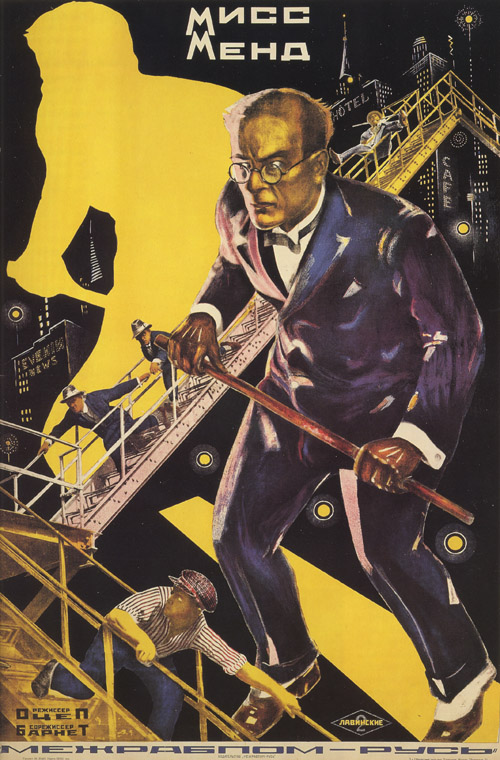

One of several posters the Stenberg brothers designed for Miss Mend.

We’ve been quite busy in the tail end of October. David sweated over a Bresson essay, started on his online version of Planet Hong Kong, and continued to help out in Lea Jacobs’ seminar on film stylistics. Kristin has started organizing a book about the statuary from the site in Egypt where she works for three weeks each year. And both of us have been steering the ninth edition of Film Art: An Introduction through the final phase of production. So instead of a blog essay this week, we offer some items from recent months that we think deserve wider notice and in some cases a pat on the back.

In our second report from the Vancouver film festival, Kristin wrote about a Chilean film, The Maid. She suggested that it was entertaining enough to be remade in English as a vehicle for an actress willing to play middle-aged and curmudgeonly. On October 16, the film was released theatrically. Starting in one theater, then going to six, and now 13 in its third week, it’s doing pretty well judging by per-theater averages. It’s not likely to get beyond big-city arthouses, but at least a release means that it should come out on DVD.

Speaking of DVDs, German silent cinema continues to be well-served with two new releases from British firm Eureka! F. W. Murnau’s 1922 film Phantom was already available in the US on the 2006 disc from Flicker Alley. The new Eureka! set includes both Phantom and Die Finanzen des Grossherzogs (1924). We saw the latter years ago at the National Film Theatre in London. It’s a comedy, and it struck us that Murnau was a bit ill at ease in that genre. Still, any Murnau film is worth a look. The set contains commentary on Die Finanzen by David Kalat, and there’s an essay on both films by Janet Bergstrom.

Speaking of DVDs, German silent cinema continues to be well-served with two new releases from British firm Eureka! F. W. Murnau’s 1922 film Phantom was already available in the US on the 2006 disc from Flicker Alley. The new Eureka! set includes both Phantom and Die Finanzen des Grossherzogs (1924). We saw the latter years ago at the National Film Theatre in London. It’s a comedy, and it struck us that Murnau was a bit ill at ease in that genre. Still, any Murnau film is worth a look. The set contains commentary on Die Finanzen by David Kalat, and there’s an essay on both films by Janet Bergstrom.

One of the best arguments that sequels and series, even those about super-villains out to rule the world, aren’t necessarily bad is Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse films. They span almost the length of his directorial career, from the two-part serial Dr. Mabuse der Spieler in 1922 through Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse in 1933, up to his last but definitely not least film, Die 1000 Augen des Dr. Mabuse (1960), which David included in his Belgian summer course. For those who can’t get enough of this arch-fiend and his followers, Eureka! has packaged all three in a new boxed set. There are numerous extras, which you can read about here. For those who have only seen The 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse dubbed in English, this set gives the option of German with subtitles or dubbed. (The films are not available from Eureka! separately.)

The films of Lev Kuleshov pupil Boris Barnet are only gradually being discovered outside Russia. One of the hits of this year’s “Il Giornate del Cinema Muto” was his 1928 comedy, The House on Trubnaya. Yes, there were Soviet Montage comedies, and this is one of the funniest. Let’s hope an enterprising company brings it out on DVD.* In the meantime, Flicker Alley is doing its bit to make Barnett known by releasing his 1926 three-part serial, Miss Mend. We saw it years ago without subtitles, so we look forward to finally finding out exactly what this fast-paced thriller is about. Something anti-capitalist involving the “Rocfeller and Co.” factory.

Soviet film was much on our minds this semester because our Cinematheque was running a series of films by Grigori Alexandrov. Probably best known for collaborating on Eisenstein’s silent films, Alexandrov came into his own in the 1930s with a series of lumpy but ingratiating musicals. They run the gamut from slapstick to mild satire (of familiar targets like bureaucrats). He likes silly gags, direct address to the audience, and a sort of relentless jollity that seems designed to prove Stalin’s claim in those years of privation that “Life has become gayer, comrades, life has become more joyous.”

Jolly Fellows (aka Jazz Comedy, 1934) is a somewhat labored effort in Marx Brothers absurdity, while Bright Path (1940) gives us a Stakhanovite Cinderella. It’s full of special-effects trickery used for comic effect, as when a poster coyly comes to life.

Although Alexandrov helped bring Hollywood production values to Soviet cinema, his 1936 Circus is a pointed critique of American racial bigotry.

Alexandrov’s best known film is Volga Volga (1938), reportedly Stalin’s favorite movie. It’s a meandering tale enacting the battle of highbrow music and popular tastes, including a clever scene (perhaps derived from the “Isn’t It Romantic?” number of Love Me Tonight) in which the movie’s principal tune jumps from boat to boat down the river, until it has become an unofficial national anthem. The films star Alexandrov’s wife, Lyubov Orlova, whose bullheaded energy swamps all resistance. The series is from a touring program, Red Hollywood, and you can read the background here.

Wisconsin Bioscope silent films went south in August–specifically, to São Paulo’s third Brazilian Days of the Silent Cinema. Here at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Dan Fuller, a photographer and historian of photography, teaches students to use classic cameras and devise their own 1910s movies. Of the two Bioscope films chosen for the São Paolo festival, A Expedição brasieira de 1916 (2006) depicts the first earthlings’ arrival on the moon. It features a stirring performance by a novice actor (above) whose film career was tragically cut short when he decided to become a professor.

Cinema in yet another land is the subject of Research Guide to Japanese Film Studies by Abé Mark Nornes and Aaron Gerow. At its center is a robust bibliography, including journals as well as books, but there’s much more: a survey of archival collections of films and documents, a list of film distributors, a gathering of online resources, and even a list of bookstores specializing in Japanese cinema. Donald Richie calls it “a reference work which both illuminates and defines this field, clearing a formerly obscured terrain for future scholarship.” Markus and Aaron are strong participants in a tide of younger scholars, both Asian and Western, who are rethinking this very important national cinema.

Images, not moving, come at you in another package. Remember Viewmasters? Vladimir, a projectionist at the Northwest Film Center in Portland, makes handsome viewmaster-style discs presenting strange tales culled from Kafka, Calvino, and less-known sources. The images are still-lifes incorporating toys and props, and it’s up to you to figure out the narrative. Concept sometimes outruns execution, but the shots suggest a childhood world turned sinister. You can even get your own viewer–called, naturally, a Vladmaster.

Images, not moving, come at you in another package. Remember Viewmasters? Vladimir, a projectionist at the Northwest Film Center in Portland, makes handsome viewmaster-style discs presenting strange tales culled from Kafka, Calvino, and less-known sources. The images are still-lifes incorporating toys and props, and it’s up to you to figure out the narrative. Concept sometimes outruns execution, but the shots suggest a childhood world turned sinister. You can even get your own viewer–called, naturally, a Vladmaster.

At Parallax View, Sean Axmaker is building an online archive of the complete run of the legendary magazine Movietone News. Richard T. Jameson and Kathleen Murphy are leading voices in American film criticism, but I suspect that the younger generation isn’t as aware of them as it should be. In Movietone News and elsewhere they provide a body of criticism that nicely balances judgment, information, and ideas. Hats off to Jim Emerson for using Halloween as an occasion to point up Richard’s astute observations on modern shot design.

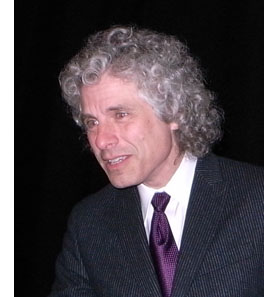

On Sunday night we went along with Jeff Smith to a campus lecture by Steven Pinker. The talk was a condensation of Pinker’s book The Stuff of Thought, a fascinating effort to show how various dimensions of language, chiefly semantics and pragmatics, reflect basic concepts of space, time, causality, and social relations. Language, Pinker says, furnishes a window into human nature. In a virtuoso turn, the book wraps up two trilogies at once: it caps a pair on cognitive and evolutionary theory (How the Mind Works and The Blank Slate) and a pair on grammar and semantics (The Language Instinct and Words and Rules).

On Sunday night we went along with Jeff Smith to a campus lecture by Steven Pinker. The talk was a condensation of Pinker’s book The Stuff of Thought, a fascinating effort to show how various dimensions of language, chiefly semantics and pragmatics, reflect basic concepts of space, time, causality, and social relations. Language, Pinker says, furnishes a window into human nature. In a virtuoso turn, the book wraps up two trilogies at once: it caps a pair on cognitive and evolutionary theory (How the Mind Works and The Blank Slate) and a pair on grammar and semantics (The Language Instinct and Words and Rules).

David first heard Pinker speak at an at extraordinary conference in Santa Barbara in August 1999. Coordinated by Leda Cosmides and John Tooby, “Imagination and the Adapted Mind” was an effort to explore how the arts could be illuminated by contemporary psychology, particularly one informed by an evolutionary perspective. This event–featuring not only Pinker but also Mark Turner, Eleanor Rosch, Ellen Dissayanake, Don Browne, and other luminaries–was a major moment in bringing “evolutionary aesthetics” to the table, although it’s taken about a decade for most humanists to catch up. (Several of the papers are available in a double issue of SubStance.) It was at that event that Pinker made his notorious suggestion that art was a byproduct of the brain’s evolution, a sort of “mental cheesecake” designed as a compact “superstimulus” appealing to our senses, mind, and emotions.

David had read The Stuff of Thought when it came out and had viewed the talk online. Sunday’s lecture remained a compelling performance, packing a remarkable number of ideas, data, and vivid examples into an entertaining seventy-five minutes. Pinker has been called the Dawkins of linguistics and cognitive psychology, but his sense of humor is rowdier. His straightfaced analysis of swearing is lively enough on the page, but it’s uproarious live.

Finally: Ever notice how many classic kung-fu movies are in widescreen? David has posted a new online essay tracing how Shaw Brothers popularized the anamorphic format in Hong Kong. The essay also considers how the widescreen format led Hong Kong filmmakers toward a distinctive approach to composition, cinematography, and dynamic movement. . . . of which the image below is a fair instance.

*[Nov 5: Thanks to James Steffen for alerting us to the fact that Edition Filmmuseum is bringing out The House on Trubnaya, along with Barnett’s other silent comedy of the same period, The Girl with the Hat Box, soon. There’s an impressive list of films in preparation, including the rare Expressionist classic Von morgens bis Mitternacht (1920), by Karl Heinz Martin. Comedy lovers should key an eye open for the release of a collection of Max Davidson’s hilarious silent comic shorts, including, we presume, the immortal Pass the Gravy.

Variety also has announced that Sundance is going national. On January 28, 2010, eight filmmakers will present their films and hold Q&As in eight theaters across the U.S.A. Madison, with one of only two Sundance multiplexes in the country, will be one of the host cities.]

Return to the 36th Chamber.

Class of 1960

DB here:

By now most people accept the idea that 1939 was a kind of Golden Year of cinema. You know, Rules of the Game, Stagecoach, Wizard of Oz, that movie about the Civil War, etc. TCM has even made a movie about 1939. On this site Kristin and I have talked about earlier wonder years, like 1913 and 1917. So in planning this year’s Bruges week-long Zomerfilmcollege (aka Cinephile Summer Camp), Stef Franck and I discussed building my lectures around a single year. I proposed 1941, but he countered with 1960.

1960 was a logical choice in providing spread for the whole program. At Bruges we intertwine several threads of lectures and screenings, and this year we had silent films (The Cat and the Canary, The Wind), Hollywood’s cinema of emigration (Florey, Siodmak, Ophuls, etc.), and contemporary Korean film. All in 35mm, of course. So picking 1960 filled in another area.

As so often happens, a contingent choice came to seem a necessary one. By the time I opened my mouth to introduce The Bad Sleep Well, I had convinced myself that 1960 was another watershed year. Consider these releases:

Rocco and His Brothers (Visconti), La Dolce Vita (Fellini), L’Avventura (Antonioni), Le Testament d’Orphée (Cocteau), Plein Soleil (Clement), À bout de souffle (Godard), Les Bonnes femmes (Chabrol), La Verité (Clouzot), The Bridge (Wicki), Wild Strawberries (Bergman), The Devil’s Eye (Bergman), Lady with the Little Dog (Heifetz), The Letter that Wasn’t Sent (Kalatozov), The Steamroller and the Violin (Tarkovsky short), The Teutonic Knights (Alexander Ford), Innocent Sorcerors (Wajda), Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (Reisz), Tunes of Glory (Neame), Sergeant Rutledge (John Ford), Psycho (Hitchcock), Spartacus (Kubrick), Elmer Gantry (Brooks), 101 Dalmatians (Disney/ Reitherman), The Magnificent Seven (Sturges), Exodus (Preminger), Home from the Hill (Minnelli), Comanche Station (Boetticher), Verboten! (Fuller), The Bellboy (Lewis), The Young One (Buñuel), TheYoung Ones (Alcoriza), The Shadow of the Caudillo (Bracho), Devi (Ray), The Cloud-Capped Star (Ghatak), This Country Where the Ganges Flows (Karmakar), Red Detachment of Women (Xie Jin), The Back Door (Li Han-hsiang), Enchanting Shadow (Li Han-hsiang), The Wild, Wild Rose (Wang Tian-lin), Desperado Outpost (Okamoto), Spring Dreams (Kinoshita), When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (Naruse), Daughter, Wives, and Mother (Naruse), Cruel Story of Youth (Oshima), The Sun’s Burial (Oshima), Night and Fog in Japan (Oshima), The Island (Shindo), Pigs and Battleships (Imamura), Sleep of the Beast (Suzuki), and Fighting Delinquents (Suzuki).

We didn’t show any of them.

Several factors constrained our choices, including the availability of good prints with Dutch subtitles, or at least English ones. We also didn’t want to run too many official classics. And we fudged a little for pedagogy’s sake. We had to include a Godard, but instead of À bout de souffle, we picked Le Petit soldat—made in 1960 but not released until 1963. The World of Apu was released in 1959 in India, though it made its world impact in the following year. Lola was finished in 1960 but released in early 1961. A dodge, but I wanted a Nouvelle Vague counterpoint to Godard, and it fit well with the Ophuls thread, and—well, it’s Demy. In any case, we wound up with a list of outstanding movies.

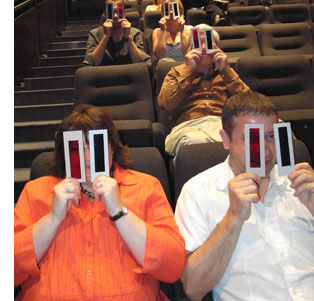

Running alongside my titles were horror films and thrillers from the same year, including Peeping Tom, Black Sunday, The Leech Woman, and Corman’s House of Usher. William Castle’s 13 Ghosts was shown with reconstructed versions of the original two-color Ghost Viewers. (Look through red if you believe in ghosts, blue if you don’t.) Imagine the shot above through a red filter. The creature, pink on the print, turns satanically crimson—confirmation that ghosts exist, although they look less like Casper and more like those Red Devil candies you ate in theatres as a kid. In a prologue, available here, Mr. Castle explains it all.

Running alongside my titles were horror films and thrillers from the same year, including Peeping Tom, Black Sunday, The Leech Woman, and Corman’s House of Usher. William Castle’s 13 Ghosts was shown with reconstructed versions of the original two-color Ghost Viewers. (Look through red if you believe in ghosts, blue if you don’t.) Imagine the shot above through a red filter. The creature, pink on the print, turns satanically crimson—confirmation that ghosts exist, although they look less like Casper and more like those Red Devil candies you ate in theatres as a kid. In a prologue, available here, Mr. Castle explains it all.

All in all, quite a week. My sessions ran from 9:00 AM to 12:30 or 1:00 PM, with the film embedded. After lunch, there were more talks and screenings, usually winding up at about 1:00 AM. Other speakers included Kevin Brownlow, Tom Paulus, Steven Jacobs, Muriel Andrin, Egbert Barten, and Christophe Verbiest (linking his talks on contemporary Korean film to the absolutely nuts 1960 Kim Ki-yong melodrama The Maid). The locals’ lectures were in Dutch, but these worthies are fluent in English, so sharing meals with them allowed me to catch up with their ideas.

Pegging a batch of movies to a single year can seem gimmicky, so I treated the films as exemplifying different trends, many of which started before 1960 and have continued since. I concentrated on trends within world film culture, though in several cases those were tied to still broader social and political developments. Above all, the 1960 frame allowed me to do the sort of comparative work I enjoy.

Generations

My first grouping was “Twilight of the Masters.” This allowed me to develop the idea that, remarkably, people who had started making films in the 1910s and 1920s were still active in the 1960s—and often making films that recalled their youthful efforts. Renoir revisited La Grande illusion in The Elusive Corporal, and Dreyer returned to his origins in tableau cinema through the staging of Gertrud.

In this connection, Fritz Lang’s 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse, his final movie, revisits his Mabuse cycle in the way his previous films for Artur Brauner revise the “sensation-films” he wrote for Joe May (especially The Indian Tomb). Drawing on some ideas in my online essay, “The Hook,” we studied Lang’s crisp transitions between scenes. From this angle, 1000 Eyes is a sort of encyclopedia of ways you can connect scenes (visual link, auditory link, association of ideas, etc.). The transitions whip up a breathless pace and steer past some plot holes, and sometimes they generate a level of mistrust, implying story possibilities that don’t turn out to be valid.

Testament’s motif of eyes and vision became expanded to television surveillance in 1000 Eyes. There might even be an oblique connection between the Hotel Luxor’s panopticon and the rise of television ownership in Europe at the period. Here, as ever, cinema doesn’t have good things to say about TV.

Twilight of another, not quite so old master: Late Autumn by Ozu. I reviewed some features of Ozu’s style and then analyzed the film as a multiple-character drama. Ozu and his collaborator Noda Kogo split up the plot in order to present different characters’ attitudes to the central situation: the question of a daughter’s marriage. The plot ingeniously withholds information about the attitude of Akiko, the mother, by deleting certain scenes that would clarify it. Here too, the old master recalls earlier films by having characters discuss their college flirtations, which invoke scenes from Days of Youth and Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth?

Both Billy Wilder and Akira Kurosawa furnished me with a second generational cohort. I know, probably nobody in his right mind would see common features between these two directors. But desperation can fuel audacity. Both emerged during the late 1930s, began directing in the 1940s, and enjoyed a string of great successes in the 1950s; but both fell on harder times in the 1960s. Both became accusatory living legends, haunting local industries that had kept them from working.

Leading up to The Apartment, I considered Wilder’s contribution to two trends. First, the industry had hit the doldrums. In Europe television and new leisure lifestyles were not yet the threat they would become, but in America, the industry needed to pull its audience away from the TV set and the barbecue. Wilder proved skilful in using Hollywood’s turn to sex as the basis for his cynical comedies. The Lubitsch touch, a worldly appreciation of the oblique approach to matters of sex, was replaced by something harsher. In Wilder’s world, there are mostly sharks and shnooks, those who take and those who are taken.

Second, I situated Wilder as a leading figure in the emergence of the writer-turned-director in the 1940s (Sturges, Huston, Brooks, Fuller, Mankiewicz, etc.). This encouraged me to probe his dramaturgy, and so we analyzed the taut structure of The Apartment’s plot. It has rightly been recognized as a model screenplay, making us sympathize with a careerist covering up his bosses’ infidelities, all the while whetting our interest by shifting the range of knowledge away from the protagonist at key moments. It also displays a nice interweaving of motifs that function both dramatically and metaphorically (especially Miss Kubelik’s hand mirror). Of course at the end I had to run a clip showing the influence of The Apartment on the opening of Jerry Maguire.

By the mid-1960s, however, Wilder was pushing his luck, especially with Kiss Me Stupid. In The Apartment he wanted to make “a movie about fucking,” and he predicted that some day people would do the deed onscreen. But having glimpsed the promised land of the 1970s, he was unable to enter. Despite some worthy efforts, notably The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, he haunted Hollywood as a major director who had outlived his moment.

Human, all too human

Kurosawa’s international fame came largely through the growth of the film festival as a prime institution of international movie culture. This situation let me sketch in the importance of festivals in bringing directors like him to world recognition. (By the way, Richard Porton has just brought out an informative collection of thoughts on film festivals.) With The Bad Sleep Well, I was able to talk a bit about something that is often forgotten—Kurosawa’s efforts in social, even political cinema. From Sugata Sanshiro, a tribute to Japanese martial arts, and The Most Beautiful, the loveliest movie you’ll ever see about girls making lenses for gunsights, up through Occupation projects like No Regrets for Our Youth and Scandal, Kurosawa engaged with political subject matter. Ikiru and I Live in Fear made this side of his work even more salient in the 1950s.

The Bad Sleep Well’s attack on corporate corruption sits well with this tendency. It considers the “iron triangle” of Japanese politics, the collusion of bureaucrats, politicians, and private industry—particularly the building industry, whose livelihood depends on bids for government projects. Still, it’s hard to believe that while Kurosawa made the film, and while Ozu made the serene Late Autumn, students were fighting police in the streets over the US-Japan security treaty. That turmoil surfaced in Oshima Nagisa’s demanding and formally daring Night and Fog in Japan.

The movie is shot with Kurosawa’s usual muscularity, including virtuoso compositions in what he called, following Toland, “pan-focus.”

The film’s twists also seemed to me worth examining. The protagonist is a minor presence in the first scenes, and his reticence in the beginning is mirrored in the finale, when he simply vanishes and his pal has to tell us what happened to him. Such a daring structure, reminiscent of the abrupt midway break in Ikiru, gives the film an almost Brechtian discomfiture, as well as highlighting the secondary characters’ rather perverse reaction to the hero’s fate.

Kurosawa was widely called a “humanist” director, and this concept sheds light on what we might call the “international film ideology” pervading festivals in the 1950s. In various areas of social and philosophical thought, a notion of humanism emerged out of disillusionment with the “age of ideology” that had engulfed the world in war. Several thinkers declared that the age of religious dogma and social collectivism, either Nazi or Communist, was over. Now what mattered were the features that drew people of all societies together, and the prospect of enlightened social action based on those commonalities—tolerance, respect, and a belief that people ultimately took individual responsibility for their communities. Catholics, Communists, and people of all stripes scrambled to call themselves humanists. As Dwight Macdonald, former Trotskyite, put it, “The root is man.”

This frame of reference can be seen in Steichen’s 1955 photo exhibition, circulated around the world in a best-selling book, called The Family of Man, as well as in the 1958 Brussels Expo, the first major world’s fair since the war. There films like For a More Human World (frame right) presented technology, science, education, and cooperation as teaming up to improve the lives of people in all nations.

This frame of reference can be seen in Steichen’s 1955 photo exhibition, circulated around the world in a best-selling book, called The Family of Man, as well as in the 1958 Brussels Expo, the first major world’s fair since the war. There films like For a More Human World (frame right) presented technology, science, education, and cooperation as teaming up to improve the lives of people in all nations.

Film festivals embraced this universalism, pointing to the great films of Italy’s Neorealist trend as proof of cross-cultural communication. Although these films often scored specifically Italian political points, they could also be seen as human documents speaking to audiences anywhere. Who could not empathize with Ricci and his son in Bicycle Thieves (named at the 1958 Expo as the third-greatest film ever made)?

The turn to humanism helps answer a puzzling question: Why Satyajit Ray? Virtually no Europeans had ever seen a film from India. What enabled a director from this country to achieve worldwide renown? And why not other Indian directors of his era, such as Raj Kapoor, Guru Dutt, Mrinal Sen, and Ritwik Ghatak? All of these had to wait many years for discovery by European tastemakers.

For one thing, Ray was highly westernized himself. He was a child of the Bengali Renaissance, a virtuoso in many fields (he composed music, drew with facility, wrote detective stories and children’s books), and an admirer of European cinema. A stint assisting Jean Renoir exposed him to one of the greatest of Western filmmakers. A viewing of The Bicycle Thieves determined him to make films. He was skeptical of imitating Hollywood, which had been a prime inspiration for Hindu cinema. He criticized Bollywood’s reliance on schematic romance and musical numbers. If any Indian director was to make the move to the festival circuit, it would be him. (You can argue that other non-European filmmakers who made it into the fold were the most “western”—Kurosawa, Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, etc.).

Just as important, Ray’s stories suited the humanist program. Whereas Ghatak and Sen made politically charged films, Ray concentrated on the individual. In The World of Apu, social conditions are shown, but as a background to the development of personality and psychological tensions. At the film’s start, students are holding a street march demanding political rights, but they are offscreen, a backdrop to Apu’s meeting with his old professor as he gets his letter of recommendation. What follows is a drama of artistic failure, blossoming love, and a young man’s confused growth to maturity and responsibility.

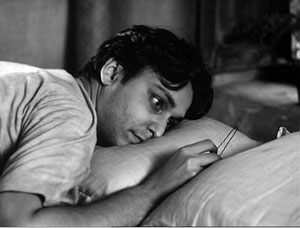

It’s a simple story, rendered lyrical through constantly developing imagery: Apu stretched out prone, the famous grimy window curtain, and a cluster of visual motifs I hadn’t noticed on previous viewing. Ray’s concise direction links the torn curtain in Apu’s room to the famous (Langian?) transition from a movie screen to a carriage window, the cluster unified by associating Apurna with male children. Thanks to Andrew Robinson’s book on Ray, we know that in the carriage scene she is already thinking of the son she will bear.

It’s easy to romanticize this handsome, happy-go-lucky hero. I think the College participants thought I was a little hard on Apu, since I treated him as far from the “conscientious and diligent” young man his professor wrote of. Surely his idealistic-novelist persona is sympathetic. But if he is to grow as the film suggests, he must have failings, and Ray shows them to us—dreamy indolence, self-centeredness, even poutiness. The film is a character study, a sort of Bildungsroman tracing how Apu learns his place in his world. Our discussion after this film was particularly rich, with one participant suggesting that in accepting his son he isn’t abandoning his art entirely, but giving it human significance: He promises to tell Kajal stories.

Ray came to directing in middle age, a somewhat rare option. So too did Gillo Pontecorvo, but the latter made many fewer films. Although Kapò, isn’t as strong a movie as our other entries, it did allow us to talk a bit about coproduction, about European cinema’s relation to World War II, and about what came to be known as the morality of technique.

European coproductions are another fundamental part of the 1960 landscape, and they illustrate how economic considerations penetrate artistic choices. (Why are American and Italian actors in the “German” film 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse? Why do we find Anouk Aimée in 8 ½ and Jeanne Moreau in La Notte? Follow the money.) For the Italian production Kapò, the primary roles are taken by an American (Susan Strasberg, playing the heroine Edith) and two French actors—the concentration camp translator played by Emmanuelle Riva and the heroic Soviet soldier played by Laurent Terzieff. The film was shot in Yugoslavia.

The story centers on a young Jewish girl who, in order to survive Nazi internment, passes herself off as a Gentile and becomes a camp commandant, whipping other prisoners into line. Other Italian films of the period, notably Rossellini’s Generale Della Rovere, were dealing with issues of conscience during the war, but Kapò was apparently the first fictional feature in Western Europe to confront the Holocaust since Alessandrini’s Wandering Jew of 1947. In 1960, Adolf Eichmann had been captured by the Mossod and stood trial the following year, and after Kapò came a few other films addressing the camps, notably Wajda’s Samson (1961) and Lumet’s The Pawnbroker (1965). So the film had a strong contemporary resonance; after its US release, it would be nominated for an Oscar.

One reason Stef and I picked Kapò was the controversy around Jacques Rivette’s accusation in Cahiers du cinéma that for a particular tracking shot Pontecorvo deserved “the most profound contempt.” The film, as Rivette indicates, is dominated by an already compromised conception of realism: grimed faces, make-up that hollows cheeks, somewhat ragged clothes, moderately shabby bunks. The shot shows the body of Theresa hurled against the electrified barbed wire, with the camera coasting slowly toward it. Her silhouette is almost classically composed, with the hands artfully pivoted and standing out against the sky. For Rivette this pictorial conceit is virtually obscene.

It seems to me that Rivette’s essay sought in part to reply to those who thought that Cahiers’ policy amounted to pure formalism. In calling for an ethics of technique, Rivette argues that artistic choices which might seem to be in the service of correct politics can betray a deeper immorality: using a historical cataclysm as an occasion for a safe realism and self-congratulatory flourishes. Similar complaints could be lodged against Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremberg and Stone’s World Trade Center. And because for the Cahiers team artistic cinema was an expression of a creator’s vision, the morally maladroit traveling shot brands the director as a man of bad faith.

Rivette isn’t saying that film artists shouldn’t try to represent historical trauma. He simply argues that other paths could be taken. For instance, Resnais’ Night and Fog and Hiroshima mon amour acknowledge that some events cannot be encompassed by normal understanding, and the form of each film enacts an effort to understand, not a fixed conclusion. What we see in Night and Fog is “a lucid consciousness, somewhat impersonal, that is unable to accept or understand or admit this phenomenon.” For Rivette, Pontecorvo seems convinced that romantic love and self-sacrifice can overcome Nazism, albeit with some help from the Red Army. He tries to explain, even prettify, an event that cannot be understood within the usual humanistic categories.

New Wave, still new

Lola.

Godard’s Le Petit soldat is far more preoccupied with uncertainties, even confusions, than Kapò is. 1960 saw an extraordinary number of former colonies, especially in Africa, gain independence, and during that year the Algerian war of resistance was spreading to Europe. Godard’s central character Bruno is working with the OAS vigilantes dedicated to killing Algerian terrorists, but when he meets the lovely Veronica Dreyer he decides to leave politics behind and flee with her to Brazil. Perhaps “decides” is the wrong word, since his actions are impulsive: he abruptly shies away from committing a political assassination, and he abruptly abandons his colleagues. But he’s captured by FLN terrorists and, in the film’s most famous sequences, tortured. At the end, he commits the assassination, not knowing that Veronica, herself in league with the Algerians, has been captured by his pals and killed. But his final voice-over is almost a shrug, and his act of murder takes on the flavor of an existentialist acte gratuite.

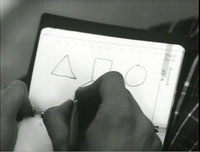

Le Petit soldat doesn’t offer heroic figures, as Kapò does in Theresa and the Soviet soldier. Nor does it allow us to sympathize much with the egotistical, capricious Bruno. The texture is more disjunctive, littered with the usual digressions and citations. Since the film was shot in Geneva, there’s a persistent motif of Swissness, with citations of Paul Klee. A sneaky one I never noticed before: the seduction game Bruno plays is modeled on the three fundamental shapes in the Bauhaus basic course, which Klee taught.

Having experimented with discontinuous imagery in À bout de souffle, Godard in his second feature turns his attention to the soundtrack, creating one of the most minimalist ones I know. If Bresson whittles down his soundtrack to a spare but recognizable realism, Le Petit soldat goes a step further, scrubbing out nearly every noise until we’re almost watching a silent film. Traffic scenes lack traffic noises, with only a car horn or a bit of dialogue breaking in. One passage on a train could almost be a sound loop.

The strategy of suppressed sound is carried to a paroxysm in the torture scenes, with the clink of handcuffs and the soft tapping of typewriter keys highlighted and bits of music played spasmodically…but no sounds of pain. Only during the rushed and almost throwaway climax, is something like a plausible city ambience heard. In a dichotomy that will be familiar throughout Godard’s work, there’s a split between image (Bruno is a photographer, and in the early part of the film he takes snapshots of Veronica in her apartment) and sound (the political factions rely on telephones and tape recorders, and the OAS thugs trick their way into Veronica’s apartment through sound recording).

In all, Le Petit soldat isn’t exactly fun but it’s exhilarating in its bursts and unexpected frictions. Next time somebody tells me that Godard’s technical innovations have all become commonplace, I’ll point to this film of 1960, which would be daring and demanding if released tomorrow.

Fun, albeit grave, is what Lola is all about. It takes formal artifice far beyond realism, creating a sort of non-musical musical. (It has one number, and even that is a sketchy rehearsal.) As geometrical as a minuet, its plot plays out in a hall of mirrors, where characters share names, pasts, and sentiments. The sailor Frankie and the wandering Michel, both in love with Lola, are blonde giants. Lola is actually named Cécile, and the little girl of the same name seems in some ways an early version of her, while Cécile’s mother has a dash of Lola in her past.

Roland starts out as the protagonist, but as he warms and cools and warms to Lola, the story momentum shifts to others. There’s Lola of course, and young Cécile who strikes up a friendship with Frankie, and Cécile’s mother who yearns a bit for Roland, and Michel, who left Nantes years ago and has lived in another movie, specifically, Mark Robson’s Return to Paradise (1952). Here the structure of the plot unfolds the network of relationships among people, linked mostly by casual encounters across a few days. The last section accordingly consists of a series of farewells, as if the story can end only by breaking ties of affection.

In surveying these films, I was struck by how much most of them owed to the growth of postwar institutions of film culture, and how strong those institutions remain. Coproductions and subsidies were feeding a massive buildup of European cinema. Contrary to what you might expect, as attendance cratered from the late 1950s onward, the number of European films produced went up. The EU countries still overproduce, releasing nearly 1200 theatrical features in 2008.

Film festivals were promoting not only universal humanism; they were also packaging films under rubrics of authorship or the New XXX Cinema and the Young ZZZ Cinema. 1940s Neorealism, aka “New Realism in Italian Cinema,” seems to have been, once more, the prototype. Festivals must make discoveries and emphasize novelties. At the same period film schools taught professional standards, and film archives showed classics and gave postwar filmmakers a more secure sense of the medium’s history. Lang, Ozu, and Wilder weren’t dependent on such institutions, but younger filmmakers were. And still are.

1960 is an arbitrary data point, but it stands out as an extraordinary year for quality. In addition, picking it as a benchmark allowed me to think about some important trends of the period. What probably didn’t show through my lumbering PowerPoints, with their charts, diagrams, and frame enlargements, was how much I learned from my Bruges stay. One of the deep satisfactions of teaching is remembering, no matter how confidently you declare your claims, how much more there is to know. Of things cinematic there is no end.

We also asked participants to read Serge Daney’s essay, “The Tracking Shot in Kapò.” Daney’s elaborate exercise in autobiography, irony, and moral reflection could not be plumbed in the time at my disposal, there or here. But it did help me understand Rivette’s argument. In preparing my lectures, I also owed a debt to some excellent books, notably Tom Gunning, The Films of Fritz Lang: Allegories of Vision and Modernity; Andrew Robinson, Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye; Carlo Celli, Gillo Pontecorvo: From Resistance to Terrorism; and Richard Brody, Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard. As ever, the invaluable documentation provided by the print editions of Screen Digest over the years enabled me to compile my tables of attendance, releases, and the like.

Late Autumn.

P.S. 3 Aug: Stef has posted snapshots from our Zomerfilmcollege here.

P.P.S. 3 Aug: This helpful correction from Roland-François Lack on Le Petit Soldat:

One small point: the organisation Bruno works for cannot be the O.A.S., which wasn’t active until the end of 1960.

He is working, rather, for ‘La main rouge’, a government sponsored counter-terrorist agency run by a Colonel Mercier (hence the name of Bruno’s associate).

Nice! Thanks.