Archive for the 'Directors: Liu Jiayin' Category

Good and good for you

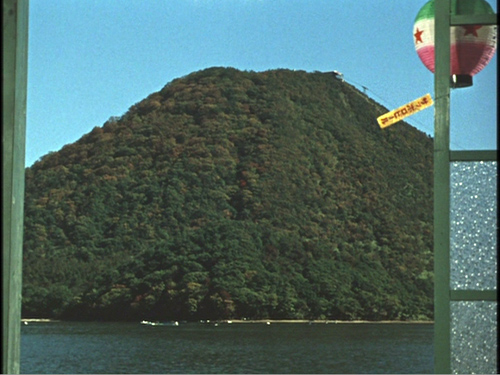

Late Autumn (Ozu Yasujiro, 1960).

DB here:

Manohla Dargis of the New York Times has just written a piece that refers to some ideas that have appeared on this site. If you see the article online, you’ll find the links to appropriate entries, but if you’ve come here after reading the paper edition of the Times, you can find the Tim Smith essay she cites here. It is a remarkable piece of work, and it’s gratifying that Dargis has called attention to it. (Tim’s video experiments have received many hundreds of thousands of downloads already.) My table-setting entry, on task-driven looking, is here.

The backstory is simple. On this site in 2008, I took a slow, unemphatic scene from There Will Be Blood as an example of how a director can subtly guide our attention without cutting, camera movement, or auditory underlining. My analysis was guided by recognition of my own responses and some knowledge of traditions of cinematic staging. Tim, in his turn, used the tools of modern perceptual research to show that we can gain firmer knowledge of directorial craft. By tracking viewers’ eye-scanning, Tim demonstrates vividly that filmmakers can shape our experience of the action on a second-by-second basis. This not only helps us understand how we grasp images. It shows that humanistic inquiry and psychological research can collaborate.

Why so unserious?

Late Spring (Ozu Yasujiro, 1949).

Those who navigate Internet eddies and flows know that dozens of responses have swirled around Dan Kois’ “Eating Your Cultural Vegetables.” Kois wants to like long, slow movies, but after trying for years, he has found that he just can’t enjoy many of them. He can mimic, even anticipate, the judgments of those who do, but in his heart he finds most of the celebrated films boring. He’s now decided to give in to his impulse and declare that he needn’t pretend to enjoy Tarkovsky or Hou Hsiao-hsien:

As I get older, I find I’m suffering from a kind of culture fatigue and have less interest in eating my cultural vegetables, no matter how good they may be for me.

As one man’s confession of guilt and fatigue, this is doubtless sincere, although its sideswiping putdowns of viewers who praise such movies suggest more calculation than humility. Still, this cry from the heart has broader implications, as many Net writers have discussed. Kois’ complaint elicited not one but two responses from the New York Times film critics A. O. Scott and Manohla Dargis. For one thing, Kois’ essay seems to offer aid and comfort to people who are afraid to try something different. Indeed, it lets them feel superior to the phonies who claim to like such films. Moreover, Kois justifies the most superficial response a moviegoer can make. Simply shrugging off a film by saying, “It’s boring!” is about as uninformative a response as saying, “It’s interesting!” And one should always be suspicious of somebody, in the name of debunkery, telling us that we shouldn’t bother to know something.

Kois’ piece exploits the special status that film enjoys in today’s culture. High and low mingle. Because movies are so accessible, and Hollywood movies are so eager to give us what somebody has decided that we want, coterie tastes are dismissed as snobbism. Things seem different in other arts. Would the Times publish a piece in which someone confessed to finding Tarkovsky’s contemporary, the Soviet composer Sofia Gubaidulina, boring? No, because to talk about her is already to enter a restricted and high-level conversation. It goes without saying that a great many listeners would be bored by her music, but who cares what non-experts think about a modern composer? Film, however, is a free-fire zone; anybody’s opinion is worth a public hearing.

I’ve kept out of the fracas because I thought Kois’ piece was silly-season fluff. Of course I wrote my own replies in my head, such as We used to have a name for this: Philistinism. I also thought that the essay operated in bad faith. Kois wasn’t as apologetic as he tried to seem. He claims humility (he “yearns…to experience culture at a more elevated level”) when really disdaining this area of cinema and considering the people who claim to enjoy it mere poseurs. The exaggerations show, I think, that this is not a serious piece:

Surely there are die-hard Hou Hsiao-hsien fans out there who grit their teeth every time a new Pixar movie comes out.

Surely not.

Still, Kois’ complaint touches on something important about film history. We have a polarized film culture: fast, aggressive cinema for the mass market and slow, more austere cinema for festivals and arthouses. That’s not to say that every foreign film is the seven-and-a-half hour Sátántangó, only that demanding works like Tarr’s find their homes in museums, cinematheques, and other specialized venues. Interestingly for Kois’ case, many of the most valuable movies in this vein don’t get any commercial distribution. The major works of Hou, Tarr, and others didn’t play the US theatre market. Sátántangó is just coming out on DVD here, nearly twenty years after its original appearance. Most of us can’t get access to the most vitamin-rich cultural vegetables, and they’re in no danger of overrunning our diet.

The race is to the slowest

City of Sadness (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1989).

For the historian, the polarization between fast pop movies and slow festival films asks to be explained. My take goes roughly this way.

From the 1940s through the 1960s, certain directors developed a new approach to telling stories. Antonioni, Dreyer, Bergman, and a few others opted for a style that relied on slower pacing and even “dead moments” that seemed to halt the narrative altogether. “Dedramatization,” it was sometimes called, and many rightly considered it a powerful innovation in the history of film as an art. But these films did get a purchase on the international movie market, often for other reasons (sex in Antonioni and Bergman, religiosity in Dreyer). They also came along at a time when there was a niche audience eager to have new cinematic experiences. (On this period see Tino Balio’s Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens.)

But artists being artists, competition grew up. The long take, for instance, got longer and more virtuosic. Miklós Jancsó, shamefully ignored today, made a series of pageants of Hungarian history in superbly sustained, intricate camera movements; some of his films have only twelve shots. But his films are sumptuous compared to what we found elsewhere. From the late 1960s through the 1970s, it seems, a new generation of filmmakers competed to make ever more austere films. They often kept the camera fixed, framed the action at a distance, and sustained the shot for many minutes. The works of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet are the high-water marks of this trend, but there were also Chantal Akerman, Theo Angelopoulos, and even Rainer Werner Fassbinder (Katzelmacher) and Wim Wenders (Kings of the Road). Werner Herzog’s successful career as a documentarist has perhaps let people forget that he once made very slow and demanding films like Fata Morgana; his Heart of Glass, screened in US arthouses in the 1970s, would surely not find a distributor today.

From a marketing standpoint, the avant-garde overplayed its hand. The new austerity came along just when Spielberg and Lucas were reinventing Hollywood. As movies got faster and louder, long-take minimalism looked perversely ascetic. Some of the directors, like Straub and Huillet, remained loyal to their project; others crossed over. It is quite a shift from Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), a 201-minute film mostly about housework, to the musical The Golden Eighties (1986) and A Couch in New York (1996). Likewise with Wenders’ Summer in the City (1970) and Wings of Desire (1987). I happen to admire both strains in these directors’ works, but there’s no doubt which is the more audience-friendly.

Today, directors who persist in long-take, slowly-paced storytelling are aiming chiefly at the festival market, which means that most of their films will be shown theatrically only, to be blunt, in France. But some of the greatest directors of our time, notably Hou Hsiao-hsien, Edward Yang, and Abbas Kiarostami, have done their best work in this mode. The US arthouse market has taken decades to discover them, through more accessible works like Flight of the Red Balloon, Yi Yi, and Certified Copy. Kois confesses to loving Yi Yi, so I’d urge him to look at Yang’s Terrorizers and A Brighter Summer Day, more rigorous but no less gripping films, though they lack the traditional arthouse bait of a charming child. Hou’s Red Balloon also has a cute kid and refers back to an arthouse classic, while Kiarostami, not normally given to couples and romances, offers us in Certified Copy a pleasantly teasing take on Antonioni and Resnais.

Minimalism of the 1970s variety got revived by 1980s American indies, notably Jim Jarmusch, but with more entertainment value. In later years he too crossed over stylistically; however unpredictable the plot maneuvers of Ghost Dog and Broken Flowers, they lack the long takes and open-ended unfolding of time we find in Stranger than Paradise. Even Kelly Reichardt, one of Kois’ targets, doesn’t give us anything like the severity of the 1970s generation. That makes the “purer” films from overseas that persist in this tradition even more off-putting. If Kois can’t take Meek’s Cutoff, as he claims, he’d find Hong Sangsoo (Oki’s Movie) or Liu Jiayin (Oxhide and Oxhide II) cinematic chloroform.

So Kois may assume that “boring” films have persisted in today’s film culture because of snobbism, but there are deeper reasons. The competition among filmmakers to push an aesthetic horizon further, the narrowing of audience tastes, the search for a budget-appropriate niche that could stand in opposition to the visual spectacle of the New Hollywood–these seem to me important factors in making slow movies a ghetto for cinephiles.

Why shouldn’t people follow Kois in giving up their vegetables? No reason, except that they’re missing some worthwhile cinematic experiences. Not all austere movies are good, but viewers who want to expand their cinematic horizons should consider the possibility of learning to look at certain movies differently. Kois can’t see that; he thinks that people who like the movies that bore him are usually phonies. But I believe that some of those admirers have developed a repertory of viewing habits that adjust to different cinematic traditions. If you can like both Stravinsky and rock and roll, why can’t you like Hou and Spielberg?

Look again, closer

Voyage to Cythera (Theo Angelopoulos, 1984).

This is the prospect opened up by Dargis’ latest article. She suggests that Kois’ response isn’t wholly based on taste. It may stem from literally not knowing how to look at certain kinds of movies.

Kois’ article treats most defenses of slow films as a matter of hand-waving and you-see-it-or-you-don’t attitudinizing. Again, he has a point: Those reactions are common, I think. The fact that cinephiles must face is that this sort of film is very difficult to talk about. We can point out the creative choices in Hollywood because narrative in some degree drives everything we see and hear. But when narrative relaxes, most viewers don’t know what to look or listen for.

The problem has haunted me for decades, ever since the 1970s when I took an interest in Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer, and Mizoguchi–all filmmakers felt, at the time, to be slow. I failed to come to grips with the problem in my 1981 book on Dreyer; I even anticipated Kois in calling Gertrud (another item that would never grace theatre screens today) boring–but I took that to be a good thing, as a challenge to conventional viewing habits.

What can I say? I was young. Since then, I think I’ve come up with better ways of talking about the other directors I mentioned, as well as some in their camp, such as Angelopoulos and Hou and Tarr. A lot of my answer comes down to the way, pace Dargis and Smith, they structure our attention.

My arguments are set out in the places I mention in the tailpiece of this entry. In brief, these filmmakers become engaging, even entertaining, when we realize that they are to some extent shifting our involvement from characters and situations to the manner of presentation. Not narrative but narration is what engages us. And we need, as Dargis points out, some schemas for grasping these alternative patterns. We have robust and refined schemas for following a story, but grasping the dynamics of narration, the how as well as the what, takes more practice, and perhaps some instruction from critics.

The process is like taking in an opera on two levels: following the stage action but also registering the patterns, the emotional highs and lows, of the music that accompanies–and sometimes overwhelms–it. Let Papagena and Papageno stammer each one’s name again and again. The repetition isn’t needed for the drama, but it’s thrilling on sheerly musical grounds.

Now imagine that sort of development transposed to cinema, in which we can appreciate, at one and the same time, not only the story’s unfolding but the patterns that present it. The supreme master of this possibility, I think, is Ozu, perhaps cinema’s Mozart. But you can find the same qualities in more somber key elsewhere. For example, in watching Angelpoulos’ Voyage to Cythera, I think that you have to be prepared to see the arrival of track workers in yellow slickers, visible through the speckled window pane in the shot above, as a kind of visual epiphany, the quiet equivalent of a stunt in a summer tentpole picture.

Given a narrative mandate, we’re on the lookout for pictorial factors that affect the dramatic situation. But when narrative slows, other things, maybe not of narrative moment, pop out, like the yellow-garbed train workers on their handcar. At such moments, it’s not that our eyes roam around aimlessly; it’s that the director guides us in a different way, toward a visual search that isn’t wholly driven by plot considerations. Here’s a shot from Ozu’s End of Summer (1961).

The principal action is a party of young people singing. But the faces are no more important than the gleaming drinks on the table, a little suite of colors and shapes that become fascinating in themselves. (For instance, several of the liquids and bottle labels sit along the same horizon line, regardless of how far the drinks are from us.) You don’t discover this half-gag, half-still-life by groping: Ozu has lit it and composed it so that you’re invited to discover it. He has found a way to activate what in most movies would be filler material. And if you think that noticing colors and shapes on the tabletop is just trivial, consider that we enjoy staring at the same sorts of patterns in an abstract Kandinsky. Or is he cultural roughage too?

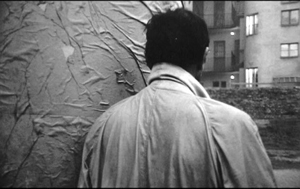

In an Ozu film, even though he cuts rather fast, we’re given time to see everything. But this isn’t random rummaging. It’s visual exploration guided by Ozu’s decisions about composition, lighting, and color. Something similar, I think, is going on with Tarr, although there it’s more a matter of texture and tactile qualities. His people shamble through mud, oily puddles, dusty corners, and tearing winds. In one shot of Damnation, a rain-soaked wall shrivels to match a wrinkled topcoat.

The story is still going forward, but by turning his protagonist from us and aligning him with the wall, Tarr has given his shot an extra layer of sensuous appeal. Try to remember the way any wall looked in Transformers 3, before it got blasted to rubble.

Slow movies let us look around, and good slow-movie makers give us something to see when we do. But what do we do when these accessory appeals don’t just accompany the narrative but swamp it? What if we lose track of the characters? The film may steer us to pictorial or auditory qualities that take over our perception.

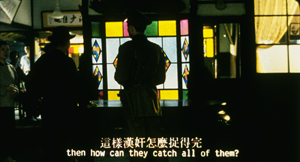

The authorities are looking for a man in the family in Hou’s City of Sadness, but you have to rely almost solely on dialogue to identify what’s going on and who’s speaking.

The sheer pictorial beauty of the shot becomes a sort of anti-narrative pretext. But if you’re alert, you won’t take the plot off the table, because at one crucial moment a figure flashes through the far left background, more or less fully lit, who may be the suspect the cops are seeking.

Sometimes you have to destroy narrative in order to save it.

Hou asks that we engage with his distant, fixed images in a complex way, being patient but vigilant, enjoying abstract geometry while also sustaining old-fashioned suspense. It’s this dynamic between story and style, fastening on plot elements but also discovering accessory pleasures and patterns, that I think constitutes one delight of the sort of films that Kois finds boring.

Add Bresson, Mizoguchi, Dreyer, Tarkovsky, and others to my list of directors whose very different styles invite us to explore what the rapid pace of most narrative cinema refuses to dwell upon. These filmmakers invite us to grasp the space and time of a scene in a fresh way. The details and dimensions of a world surge forward, not simply as a backdrop for characters hurtling toward a goal, but as something valuable in their own right. For some viewers, me included, they do more. They also ask you to transfer those viewing skills to life outside the theatre. They encourage you to find a new way to look at our world.

Not all slow, minimalist movies are good. That’s why I think critics are obliged to rebut Kois with careful analysis, not the gaseous generalities about sublimity and eternal mystery to which we too often resort. Digging deeper, we can not only answer skeptics but expand our understanding of how cinema works. These films have opened windows for many of us. Why should we keep them to ourselves?

First, thanks to Manohla Dargis for enjoyable correspondence about these issues.

Tim Smith’s blog, Continuity Boy, is a good way to keep up with his energetic and expanding research program.

Dargis mentions the invisible gorilla experiments of Chabris and Simons. I talk about their relevance to film here and here.

Kristin has written on comparable matters in Tati; she even wrote an essay on M. Hulot’s Holiday called “Boredom on the Beach.” (It and an essay on Play Time are in her book Breaking the Glass Armor.) Tati’s films, in their spasmodic pauses and shamelessly repeated or sustained gags, could also count as part of the postwar dedramatization trend.

My initial arguments about different registers of viewer perception and cognition were made in Narration in the Fiction Film (1985). My case for Ozu is in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, available online. More recently, I’ve become interested in cinematic staging and have concentrated on challenging directors like Mizoguchi, Angelopoulos, and Hou; see On the History of Film Style (1998) and Figures Traced in Light (2005). All of these “slow” filmmakers ask us to be sensitive to unusual sorts of narrative patterning, and some purely non-narrative patterning. More thoughts on these matters can be found in The Way Hollywood Tells It (20006) and Poetics of Cinema (20007).

On this site, you can find similar lines of argument, especially about Béla Tarr, Mizoguchi Kenji, and silent directors like Louis Feuillade, Victor Sjöström and some Danish creators. See director entries for Hong Sangsoo, Liu Jiayin, and others mentioned above. Later this month I hope to post a bit more about how directors guide our attention without recourse to fast-paced editing–before editing was really invented.

Sátántangó (Béla Tarr, 1994).

DIY dumplings

DB here in Madison, homebound from pneumonia, pining for Kristin and Ebertfest in Illinois:

The energetic Kevin Lee (when does he sleep?) has prepared a very nice video essay on Liu Jiayin’s Oxhide II at Moving Image Source.

The text is based partly on my blog entry on the movie from 2009. Kevin’s is something of an experimental piece, because it presents extracts from the entry in different voices and languages. I wasn’t able to narrate it because I’ve lost my voice, but the readers did better than I could have. Thanks to Evan Davis and Yuqian Yan, as well as the translators involved.

You can buy Liu’s first two Oxhide films on DVD at dGenerate Films, along with other important recent Chinese titles. Every university film department, and every serious lover of cinema, needs to own these movies. Liu shows what you can do with very few means but a lot of imagination. And Oxhide III is in the works.

And don’t forget to visit the videos of introductions and Q & A’s from this year’s Ebertfest here. Some are streaming, some are archived, all are interesting. As I typed this, Paul Fierlinger was talking about the background to My Dog Tulip.

Arthouse suspense, in big and small doses

Le Quattro Volte.

DB here:

As happened last year, I had to flee Hong Kong for medical reasons. Beset by a wracking cough, I took off three days early and upon returning to Madison wound up in hospital. Current diagnosis: pneumonia. Duration of stay: six nights and counting. A drag. But I’m lucky: no disorderly orderlies, no homicidal doctors injecting me with mind-control drugs (“You will watch only Brett Ratner films for the rest of your life. Sleep, sleep…”). I’m taken care of by expert, calm, and good-natured people. Expect no less from the best city for men’s health and care.

So I’ve been tardy in writing this final HK blog. I just wanted to talk about two extraordinary films I saw in my final days and bring up a scrap of news for followers of Chinese film.

First, the news. Liu Jiayin, of Oxhide fame, was in Hong Kong briefly to accept an Asian Film Financing Forum award for her screenplay Clean and Bright. The other winner was Li Ruijun, for his project Where Is My Home? Liu was about to visit the US for screenings at Redcat, under the sponsorship of the tireless Bérénice Reynaud, and at Cinema Pacific in Portland. I had a chance to talk briefly with her just before she departed.

First, the news. Liu Jiayin, of Oxhide fame, was in Hong Kong briefly to accept an Asian Film Financing Forum award for her screenplay Clean and Bright. The other winner was Li Ruijun, for his project Where Is My Home? Liu was about to visit the US for screenings at Redcat, under the sponsorship of the tireless Bérénice Reynaud, and at Cinema Pacific in Portland. I had a chance to talk briefly with her just before she departed.

Regular readers of this blog know my admiration for Liu’s two Oxhide films. The good news is that she is at work on Oxhide III. She wouldn’t say much about it, except that she is still reworking the script, but it sounded quite far along. In addition, she hopes to shoot Clean and Bright, a more orthodox film about a family, fairly soon as well. Oxhide IV is also planned, with the series running up to perhaps eight installments.

For more on Oxhide, including purchase information for the DVD, check Kevin Lee’s dGenerate Films website.

Leaving us hanging

Too often we think of suspense as specific to certain genres, but it’s actually a fundamental resource of all storytelling. Creating expectations about an upcoming event, sharpening them, and delaying their fulfillment–all these strategies are basic, I think, to narrative experience in general. Although some plots emphasize suspense more than others, even most “character-centered” tales wouldn’t engage us without a dose of it.

True, sometimes there’s a sort of bait-and-switch, as when suspense is conjured up but eventually dissolved. Sooner or later we realize Godot isn’t going to show up, or that Anna in L’Avventura is likely not to be found. In those cases, suspense has led us to another terrain, usually thematic, in which we’re invited to consider something more significant than learning the outcome of events. (Sometimes, though, snuffing out suspense is just a sign of slack, or Slacker, storytelling.)

Suspense is usually associated with popular plotting, so many people expect Serious Films to be lacking in suspense. Which makes it all the more interesting that Iran, one of the most-favored nations on the festival circuit, has made something of a specialty of suspenseful art movies.

We don’t recognize often enough that Kiarostami’s early films are often structured as suspenseful quests, from the boy’s attempt to return his schoolmate’s notebook in Where Is the Friend’s Home? to the final shot of Through the Olive Trees. His scripts for other directors convey this quality even more clearly. The Key is almost Griffithian in showing how a four-year-old boy struggles to rescue his younger brother when they’re locked in a kitchen with a gas leak. The Journey (Safar) is positively Ruth Rendellian: A headstrong middle-class father leaving Tehran with his family forces another car off the road and flees the scene. Instead of resting at a summer retreat, he returns obsessively to the place of the accident to check the progress of the investigation: Will he give himself away? And it isn’t just Kiarostami. Look at the suspense structure in Makhmalbaf’s Moment of Innocence, or Reza Mir-Karimi’s The Child and the Soldier, or Panahi’s The Circle.

What gives Iranian suspense films their weight is partly the fact that they don’t rely so much on the old standbys (chases, stalkings, cliffhanging rescues) but rather on psychological maneuvers, carried out largely through dialogue. Characters in these movies tend to talk a lot, pushing their concerns forward with a stubbornness that we seldom see in other national cinemas. People stick up for themselves, and the suspense comes from a clash of testimonies, pleas, and self-justifications. But it also comes from a moral dimension. My earlier examples depend on our assessing what we ought to happen (the hero of the Journey should be punished) versus what we might want to happen (he should escape). Add a dash of mystery, as we have in Through the Olive Trees (what is Tehereh thinking?) and A Taste of Cherry (what is the job Mr. Badi is hiring for?), and you have artistically ambitious filmmaking that exploits some very traditional resources of the art form.

These resources were on display in Asgar Farhadi’s earlier About Elly, which I praised in these pages two years ago. Nader and Simin, A Separation has a comparable power to seize and hold our interest. A wife fails to get a divorce and leaves the household, which includes not only her husband Nader but his Alzheimer’s-addled father and their daughter Termeh. Without Simin to care for his father, Nader hires Razieh, a working-class woman who must bring her little girl with her. Soon the job overwhelms Razieh and, for reasons not disclosed till later, she goes missing. Nader and Termeh find the old man tied to the bed, unconscious.

For this early stretch of the film, the helper Razieh trembles on the verge of hysteria, and only later do we learn why. When she returns to the apartment, she confronts Nader’s wrath, which leads to yet another turning point, but one whose significance we realize only later. To complicate matters, Razieh’s hot-headed husband becomes furious with everyone. As in About Elly, a great deal turns on what characters know at one precise moment, and our memory of when they learned something can be as elusive as theirs. And as in Henry James’ novels, much of the action is registered through the reactions of onlookers, notably the pensive daughter Termeh (below), who turns out in the final scene to be as important as any other figure in the film.

The suspense builds on many levels: the progress of the divorce, the decline of the old man, the court case that involves Razieh’s place in the household (did she steal money?), and above all the responsibility for a death. Some of these lines of action are shown resolved; a crucial one remains suspended. And that does, as often happens, oblige us to think more broadly about the film’s treatment of parent/ child relationships. We are left with an exceptionally rich film, one reflecting on class differences, religious ones, and the effects of adult problems on the children around them. Suspense not only feeds our hunger for story; it can also tease us to moral reflection, and Nader and Simin does just that.

No suspense?

How much can you purge suspense from a movie? And if you play it down, what do you put in its place to hold our interest?

One answer to these questions comes in Michelangelo Frammartino’s Le Quattro Volte. It is one of those sedate observational pieces that covers a year in the life of a village, with not much discernible dialogue but lots of lovely landscape shots. It has a cyclical rather than linear structure, beginning and ending with smoldering wood turned into charcoal–itself a metaphor for the inevitable transmutations that govern plants, animals, and men. We follow an old goatherd who eventually dies; his goats pay homage by climbing precariously to his tiny home and occupying it. A young goat is born soon after the old man’s death. The townsfolk erect an enormous Christmas tree, which at the end of the holiday is chopped down into bits, which will in turn becomes charcoal. If Nader and Simin exists largely in medium-shot, here the extreme long-shot dominates. There are no psychological interactions or dramatic issues of the sort we find in Fahradi’s films. In the rustic spirit of Rouquier’s Farrebique, we get the sheer successiveness of things, the fact that life is one damned, or placid, moment after another.

So suspense can be replaced by sheer consecutiveness, but the task then becomes to make things interesting. Frammartino does so through careful framing, evocative sound, and crisp storytelling technique. The goats pick their way up to the old man’s hillside apartment; they jostle around inside; cut to a shot of the old man’s head as he lies dead; cut to the church, with people filing out as the bell tolls. In addition , you can find suspense at more micro-levels, working not at the level of plot action as a whole but rather within and across particular scenes. After the goatherd’s death, we see another kid born: this is familiar, even clichéd, the rhythm of nature. We follow the kid’s efforts to assimilate to the herd. But as winter comes, the kid strays off, becomes isolated, and ends up lost and shivering. We must assume that he dies. So much for the great cycle of life.

At a still more microscopic level comes the shot that everyone remembers from Le Quattro Volte. It’s so salient that critics who seldom notice imagery can’t help but mention it. I won’t describe it in detail, so as not spoil the surprises, but suffice it to say that it involves a church procession, some intransigent goats, a pickup truck, and a resourceful dog. Reminiscent of Tati or Suleiman, this long shot depends on ratcheting up our expectations about how several converging events might develop, onscreen or off, and then fulfilling those expectations in startling ways. We might call the result spatial suspense: How will this composition-in-time finally resolve itself?

We should, then, never underestimate the power of suspense, even in those films which might seem to forswear it. Melodrama or pastoral, any genre can find a way to excite us by asking what can come next.

Catching up: By leaving Hong Kong early I missed the second screening of The Turin Horse; my first impressions are here. Since I wrote that, I learned that Cinema Scope has published Robert Koehler’s sensitive appreciation of the film and his enlightening interview with the cinematographer Fred Kelemen.

Nader and Sinin, A Separation.

The Dragons & Tigers’ late-night roar

Thomas Mao.

DB here:

First, the news flash: Tonight was the awards ceremony for the Dragons & Tigers competition for young filmmakers here at Vancouver. A jury doesn’t get more distinguished: it consisted of (left to right) Jia Zhang-ke, Denis Côté, and Bong Joon-ho.

They awarded two special mentions, one to Phan Dang Di’s Don’t Be Afraid, Bi! (from Vietnam) and to Xu Ruotang’s Rumination (China). On the last-named, check the still at the end of this entry.

The grand prize went to the Japanese film Good Morning to the World!, by Hirohara Satoru.

More details here. Congratulations to the winners!

Beginners’ luck

My Film and My Story.

Vancouver is unusually hospitable to shorts and features by newcomers. Two of this year’s D & T offerings illustrate how talent, unlike youth, is not wasted on the young.

A cinémathèque featuring classic films is about to reopen, and the manager has hired some twentysomethings to help her get things into shape. The result a network narrative: romantic rivalries, coming-of-sexual-age crises, the race to set up the screening space, and even a ghost story are woven together as the big day approaches. The film is split into eight chapters, each given an emblematic movie title. Two petty thieves interview for a job under the aegis of “Stranger than Paradise,” and an apparent love triangle is christened “Jules and Jim.” The cinephilia shapes the plots too, as when one boy gets the courage to kiss another after watching Happy Together.

My Film and My Story was a group project of students at the Art and Design School of Konkuk University in Seoul. Their professor proposed that each student write a script about the opening of the cinematheque, and the results were integrated into a single feature-length story. There were seven student directors, one per episode; a producer contributed an extra chapter. Most directors were on the set all the time, making suggestions and trying to fit bits together. (“We fought a lot.”) The remarkable visual consistency—smooth cutting, tight framing, and well-modulated lighting—came from the single director of photography. As the title suggests, some of the tales are based on incidents in the lives of its makers.

The film, presented in Vancouver by two of the directors, Hong Youjin and Kim Taeho, is a lively charmer, with plenty of comedy and pathos. The characters are quickly introduced, and there are nice touches of movie-nut satire. One girl with big spectacles saves all her ticket stubs, takes notes on every movie (I can identify), and is annoyed when a boy drapes his leg over the seat in front of him. The episodes make tactful use of digital techniques, particularly in one shot that fuses past and present through the classic color/ black-and-white disparity.

My Film and My Story wasn’t in the official young-film competition, but Icarus Under the Sun was. For once the ragged style of handheld video justifies itself in a tale of a girl who quits school and heads for Tokyo to work in a seedy mahjong parlor. Haruo rooms with a flighty roommate and her boyfriend, but becomes more attached to the workers in the parlor and the owner, a nearly blind, taciturn man for whom she conceives an almost daughterly affection.

The plot barely rises above anecdote, but it’s continually engaging through its focus on the performance of Abe Saori, one of the two directors. Haruo explains that she is “addicted to walking,” and some of the best scenes involve conversations during late-night wanderings in the bitter cold.

Starting out fairly choppy, the narration accumulates weight and breadth as Haruo becomes engaged in her work. The shots throughout are held rather long, but about halfway through, the scenes start to be built out of exceptionally long takes. When another worker, the boy Aran, takes sick, Haruo calls on him and we get an almost suspenseful treatment of her arrival in his apartment, with him lying almost motionless in a heap in the foreground.

The shot lasts almost four minutes as she comes forward to talk with him. Their subsequent conversation is filmed in a tight, leisurely shot as they eat burgers and explain their backgrounds—virtually the only exposition we get about Haruo’s troubled past.

The dingy look of many scenes carries a documentary conviction that a more polished work would not. And the rough texture is actually the product of patient care. Abe and her codirector Takahashi Nazuki explained that they spent ten months in shooting and two to three months in editing. But it’s no mere technical exercise either, since Abe calls it both a fictional film and a documentary about her experiences. Like her protagonist she spurned conventional schooling and went to Tokyo to live on her own. Rooming with Takahashi, she decided to make the film “to know certain shadows” in her life. Icarus Under the Sun is actually the duo’s second film, and they have already finished a third, the more technically slick Soft-Boiled Egg (Hanjuku tamago.). Another thing about young directors: They have energy.

Expecting

Takashi Miike’s 13 Assassins is not what you might expect. Unlike your typical Miike item, this one throws no curves. It is an old-fashioned, butt-stomping, gut-slashing swordplay movie, with swagger to spare. Adapted from a 1963 film, it’s Seven Samurai plus six, with explosives.

True, there’s a Miike signature moment early on that shows what Lord Noritsugu has done to a woman’s body in his quest for piquant entertainment. But this horrifying scene serves a very traditional purpose: To prove to swordmaster Shinzaemon Shimada (and us) that Noritsugu has failed his duty as a leader and must be assassinated. He isn’t merely brutal. He lives an aesthetic of exquisite savagery. He has turned droit de seigneur into performance art. A massacre, he says with a fetching smile, is fun. He is a handsome monster. We can hardly wait to watch him die—preferably like a dog, in the mud, in agony.

Thereafter all that we want from a chambara flows forth in abundance. Unsurprisingly, the plot is framed by the man-out-of-time motif. Noritsugu’s depraved tastes show that the samurai tradition and the Shogunate government have become decadent. This might be a warrior’s last chance to die nobly—but for what? What deserves a man’s loyalty? Hard times have convinced Shinzaemon that the samurai class must ultimately serve the people. But his old rival Hanbei, Noritsugu’s right-hand man, clings to the notion that the samurai serves his master, unswervingly. Hanbei goes to his death committed to traditional duty. But his commitment is proved unworthy when his lord has a little fun with his severed head.

Miike faced a choice. He could have provided each warrior a vivid backstory, differentiating and humanizing each one as Kurosawa did. Instead, given a two-hour running time, he concentrates on strategy: How can a baker’s dozen of fighters defeat Noritsugu’s troops, which will eventually swell to 200? The solution is to maneuver Noritsugu’s men into a village filled with traps that will give the assassins some advantages—surprise, rooftop ambushes, and a deployment of livestock as ordnance. Things are enlivened by a feral hunter, mocking the samurai code while wielding a mean slingshot. After supplying a sketch of each of the thirteen assassins, Miike spends his energy on action. The muddy, gory battle at the climax lasts forty-plus minutes, and is worth every penny of your admission. Magnet, the genre arm of Magnolia, has picked up 13 Assassins for early 2011 release, and you should start thanking them already.

If Miike surprises by doing something normal, Zhu Wen’s Thomas Mao really does keep you guessing. It’s a pleasure to see a movie in which you can’t imagine what will come next.

At first, things seem to go by the numbers. To a remote Chinese farm comes the artist Thomas, to stay a short while and do some drawing. His wizened host Mao provides bed (after the geese are shooed out) and board (mostly corn on the cob). The trouble is that Thomas speaks no Chinese and Mao speaks no English. Every interchange is a pas de deux of misunderstanding. Thomas generously gives Mao some money. Mao refuses—not, as Thomas thinks, because he’s too proud but because Mao considers the amount insultingly small.

So we seem to have the small-scale cross-cultural comedy, making amusing points about people’s petty differences. Then the ghosts arrive.

At least, they might be ghosts. A phantom swordsman and swordswoman float around Mao’s farm and do battle, ultimately slashing off each other’s arms before disappearing, never to return.

There are aliens too, invading Mao’s cabin with pop-concert glow sticks. They’re totally unexpected, like the warriors, and their visit is even more transitory.

Eventually Thomas leaves, and the film starts over. The second part offers a sort of crazy-mirror image of what we’ve seen so far. Artist becomes model, model becomes artist, dog becomes Doggy. If you like the double-track story of Syndromes and a Century, you’ll probably like Thomas Mao, which is less rigorous but more funny. (The very title is part of the joke.) Zhu, who has reveled in comic byplay in Seafood and South of the Clouds, gives us that rare thing, a movie that is whimsical without being precious. You learn about contemporary Chinese painting in the bargain.

More whimsy, also not overbearing: When Liu Jiayin told me last spring that she was making a movie about a plastic fish, I didn’t know what to expect. The answer comes in the short film 607. Here the ballet of family hands seen in Liu’s Oxhide II becomes more playful. 607 is part of a promotional series of shorts by independent filmmakers, and it’s sponsored by a Beijing hotel, The Opposite House.

Mr. Fish, wielded by Liu’s father, swims around the tub, occasionally flirting with a mushroom provided by her mother. Eventually Mr. Fish is tempted by a hook (the curled finger of Liu herself). Will he fall for it? In all, you have to admire the coordination of three people shifting smoothly offscreen around the tub, each person’s hands sliding out of one part of the frame and popping in somewhere else—somewhere, I need hardly say, fairly unexpected.

PS 9 October: This entry has been corrected from its initial appearance. There I had written that Liu Jiayin’s 607 is one of three films she is making for the series commissioned by The Opposite House. Actually, the entire series consists of three films made by independent filmmakers. 607 is one of those and is complete in itself. Thanks to Shelly Kraicer for the correction.

Rumination.