Archive for the 'Directors: Loznitsa' Category

Sergei Loznitsa and the Ukraine invasion

Donbass (2018).

DB here:

Of the many gifted post-Soviet-era filmmakers, one has emerged prominently in response to Russia’s invasion of the country. Sergei Loznitsa was born in Belarus, grew up in Ukraine, and now lives in Germany. Long a harsh critic of Putin’s regime and the Soviet communism that preceded it, he recently resigned from the European Film Academy, citing its lukewarm response to the atrocities in Ukraine. Here is the full text of his letter, as published in Screen International (28 February).

What a shameful text has been generated by the European Film Academy! “The invasion in Ukraine is heavily worrying us”.

When, in the spring of 2014, Oleg Sentsov was arrested, you wrote to the Russian authorities asking them to “consider this matter carefully and fairly”.

Is it really possible that after 8 years of war you still remain blind and continue to mutter some gibberish about the fact that a “daily increase of tension has an impact on filmmakers’ lives and health, morale, and creative work”.

You state in your address that there are 61 Ukrainian members among your ranks. Well, as of today, there are only 60 of them. I don’t need you “being alert and staying in touch with me”, thank you very much!

You’d better ‘stay in touch’ with your own conscience.

For four days in a row now the Russian army has been devastating Ukrainian cities and villages, killing Ukrainian citizens. Is it really possible that you – humanists, human rights and dignity advocates, champions of freedom and democracy, are afraid to call a war a war, to condemn barbarity and voice your protest?

Today, on February 28, 2022, there can be no more doubt about one thing: the European Film Academy was set up in 1989 in order to bury its head in the sand and to shy away from the catastrophe which is taking place in Europe.

Sergei Loznitsa, filmmaker

The day after Loznitsa’s resignation the EFA issued a stronger statement of condemnation.

Loznitsa has directed several documentaries and four fiction features. The documentaries are notable for their comprehensive, patient rendition of original footage of historical incidents. No Ken Burns guidance of the viewer here, no pan-and-zooms or talking heads. There’s a remarkable refusal of voice-over narration to fill in the context of what we see. Even titles are sparse. Often the necessary background is given in an envoi. Homework for the viewer: We need to read up on exactly what we’re seeing.

Loznitsa has directed several documentaries and four fiction features. The documentaries are notable for their comprehensive, patient rendition of original footage of historical incidents. No Ken Burns guidance of the viewer here, no pan-and-zooms or talking heads. There’s a remarkable refusal of voice-over narration to fill in the context of what we see. Even titles are sparse. Often the necessary background is given in an envoi. Homework for the viewer: We need to read up on exactly what we’re seeing.

The Trial (2018), for instance, is an unblinking record of an early Stalinist show trial, in which scientists are charged with anti-Soviet sabotage. They read their confessions, but under questioning they seem confused about what they’re admitting to. The whole procedure is conducted with mechanical impersonality, and you watch for any sign that the accused men will crack. Only at the end do titles tell us that their supposed secret organization was wholly a creation of the regime. Likewise, The Event (2015) records citizen mobilization in St. Petersburg during the failed communist putsch against Gorbachev in 1991. It assumes the viewer will understand that the snatches of Swan Lake heard from time to time allude to the fact that Tchaikovsky’s score was broadcast continuously in place of news reports.

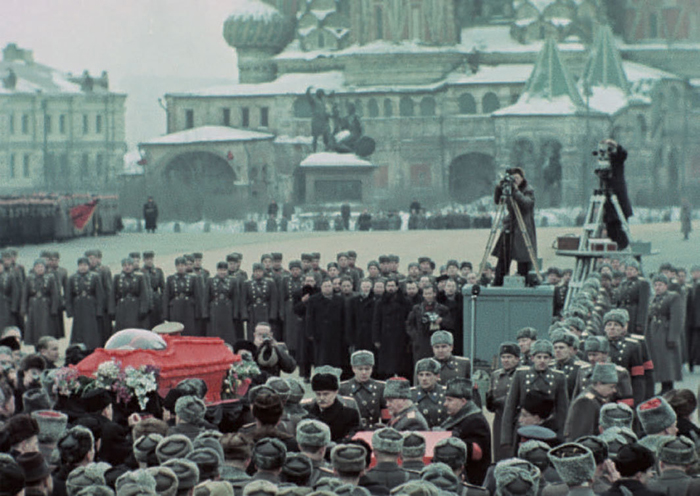

Perhaps most stunning of the documentaries I’ve seen is State Funeral (2019), an assemblage of footage of ceremonies following Stalin’s death. I’ve seen some of this material in other films, but to show the entire panorama of mourning across the Republics, mostly in dazzling color, brings home with crushing near-monotony how a regime can mobilize mass emotion. These people seem genuinely despairing at the loss of the Great Helmsman. The pageantry is at once splendid and appalling.

The three fiction films I’ve seen are bleak. My Joy (2010) follows a Russian truck driver through a landscape of poverty, corruption, and teen prostitution, and invokes World War II through a strange time-warp. In the Fog (2012) rewrites the scenario of the heroic Soviet WWII picture through the experiences of a man caught between both German occupation forces and Belarussian partisans.

Unlike these, Donbass (2018) lacks a single protagonist. It’s a string of scenes based on actual incidents from the 2010s. It shows the ongoing struggle between Putin-backed separatists and Ukrainian forces in Donesk, with ordinary people struggling to carry on. The tone is wider than in the other films, with pathetic scenes alternating with grotesque comedy. An early episode shows a woman stomping into a civic meeting and dumping a pail of shit on a bureaucrat’s head. A bit like Roy Andersson, Loznitsa connects his vignettes by having a character from one linking to the next, or letting an item of setting, such as a black Mercedes, reappear at different points. The whole film is enclosed by a tragic replay of an opening showing the staging of a fake massacre, to be filmed by an obliging official media outlet.

These films are fairly available. All the fiction features are on DVD or Blu-ray. Five of the documentaries (including A Night at the Opera, 2020, which shows a mordant sense of humor) are streaming thanks to Mubi. In the Fog is streaming from Fandor/ Amazon Prime. Some online sites are offering the films, subtitled, for free. The Guardian has made Maidan (2014) available on YouTube for the duration of the war on Ukraine, to support donations to the Ukrainian Army. This film traces the popular overthrow of President Yanukovich in the winter of 2013-2014.

Loznitsa’s films have been accorded many festival awards, in Cannes, Venice, and elsewhere. Sometimes castigated as “Russophobic,” they’re strong, bracing work and they deserve our attention, especially now.

Loznitsa’s website is here. His views of Soviet history are revealed in a spirited interview with Senses of Cinema. At Criterion’s The Current, David Hudson gives an up-to-date report. In The New Yorker Masha Gessen offers a thoughtful review of The Trial. J. Hoberman has an excellent, informative essay on State Funeral in Artforum.

Thanks to Michael Campi for the link to Maidan.

P.S. 7 March 2022: I just discovered this illuminating, detailed review of Donbass by John Bennett at The Movie Waffler.

State Funeral (2019).