Archive for the 'Directors: Lubitsch' Category

Preserving two masters

Kristin here—

This past weekend the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Cinematheque played host to Stefan Drössler, the head of the Filmmuseum in Munich. The Filmmuseum is a major force in film restoration, and on Saturday we were treated to a much longer print of Ernst Lubitsch’s 1922 epic, Das Weib des Pharao, than had previously been available.

Lubitsch on the verge of going Hollywood

This restoration came too late for me to see it before my book on the director’s silent features, Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (2005), was published. Not that that was a problem. I was dealing largely with style in that book, and the old version furnished plenty of examples to support my point. I argued that Das Weib was a turning point in Lubitsch’s career. It was the first film he made after the German ban on film imports was lifted and he was able to see recent Hollywood films for the first time since the war. It was also made with American financing, offering him the chance to work with American cameras and lighting equipment—an opportunity that gave him much more stylistic flexibility.

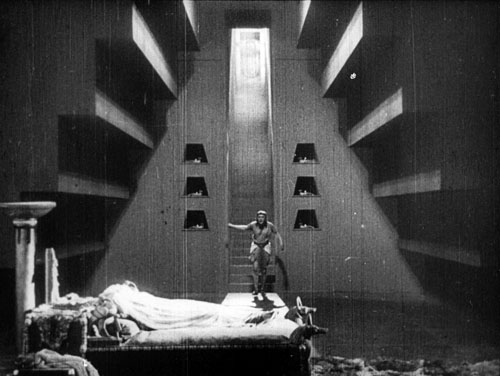

As a result, Lubitsch goes from using mostly flat, frontal light to employing the recently developed three-point lighting system. The frame above shows a very Hollywood-style lighting layout, and that’s fairly typical of this film.

Of course, it was a treat to see the film with so much new material. As I recall, the old version ran about 40 minutes, while this one is 110 minutes. There’s still footage missing, replaced in this print by still photographs and summary intertitles. Still, the plot makes a lot more sense. For the most part, the visual quality is better. The restoration depended on footage supplied by a number of archives, however, and the occasional inferior shot indicates that a less well-preserved print had to be used as source material.

The story, set in ancient Egypt, is rather clichéd and the characters little more than ciphers. The interest lies mainly in the style and the majestic scale of the production. Given a much larger budget than usual and a longer shooting schedule, Lubitsch distinctly outdid his own earlier historical dramas, Madame Dubarry (1919) and Anna Boleyn (1921). Reportedly 8000 extras participated in the battle and crowd scenes, and the sets were erected on a colossal scale. Designer Ernst Stern was a serious Egyptology buff, and despite occasional lapses, the sets, props, and hieroglyphs are a lot more authentic than those in most movies set in this era. The film’s cast also includes a remarkable line-up of some of the most prominent actors of its day: Paul Wegener, Albert Bassermann, Harry Liedtke, and Emil Jannings (above).

Perhaps, as happened recently with Metropolis, a new, complete version of Das Weib des Pharao will someday be found. As Stefan said, however, more footage from Lubitsch’s last German film, Die Flamme (1922) would be even more welcome. An intimate drama starring Pola Negri, it survives in only one tantalizing reel. That footage reveals the director’s rapidly growing grasp of continuity editing as well as three-point lighting. Clearly he was ready to make the move to Hollywood and to even further development as a filmmaker. (My own dream film to be rediscovered would be Kiss Me Again, a completely lost 1925 Warner Bros. feature. Odds are pretty good that the one film Lubitsch made between The Marriage Circle and Lady Windermere’s Fan would be a masterpiece.)

A new Walter Ruttmann DVD

Seeing a 35mm print of such a restoration well projected is the ideal, of course, especially with an expert pianist like the Cinematheque’s David Drazin providing the accompaniment. For those who can’t get to such screenings or who want to study its restorations, the Filmmuseum also makes many of its restorations, as well as art and avant-garde films, available on DVD.

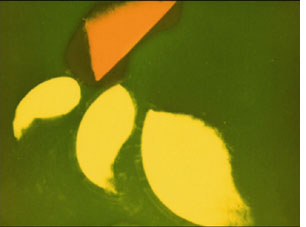

Stefan gave us a copy of one of the latest of these, a Walther (or Walter, as he sometimes spelled it) Ruttmann disc entitled “Berlin, die Sinfonie der Grossstadt & Melodie der Welt.” Actually, that’s a bit misleading, since the DVD actually contains a great deal more than those two features. All of Ruttmann’s surviving films up to 1931 are included. He was on the forefront of abstract animation, and the full series, Lichtspiel Opus I (1921), Opus II (1922), Opus III (1924), and Opus IV (1925), is included here. All have musical accompaniment, including Hanns Eisler’s 1927 score for Opus III. (That’s a frame from Opus I on the left.)

Stefan gave us a copy of one of the latest of these, a Walther (or Walter, as he sometimes spelled it) Ruttmann disc entitled “Berlin, die Sinfonie der Grossstadt & Melodie der Welt.” Actually, that’s a bit misleading, since the DVD actually contains a great deal more than those two features. All of Ruttmann’s surviving films up to 1931 are included. He was on the forefront of abstract animation, and the full series, Lichtspiel Opus I (1921), Opus II (1922), Opus III (1924), and Opus IV (1925), is included here. All have musical accompaniment, including Hanns Eisler’s 1927 score for Opus III. (That’s a frame from Opus I on the left.)

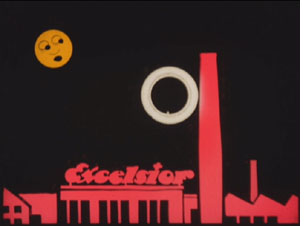

In addition, there’s a group of charming advertising films, all animated. These tend to be abstract and only bring in the product near the end. In doing the short for Excelsior tires, however, Ruttmann obviously found a round, nearly abstract shape that he could play with. A  tire rolls around in a flat landscape, having adventures that include going up and down the Excelsior factory smokestack and being threatened by spiky shapes that fail to puncture it.

tire rolls around in a flat landscape, having adventures that include going up and down the Excelsior factory smokestack and being threatened by spiky shapes that fail to puncture it.

Apart from these shorts, the two-disc set includes as bonuses a series of 22 paintings and drawings by Ruttmann, a number of texts by and about him, photographs, and so on. There’s also a CD-ROM section with additional documentation, plus a small booklet.

The two features are restorations. If you’ve only seen Berlin on a mediocre 16mm copy, this version should be a revelation. Its visual quality is gorgeous, and it has the original Edmund Meisel score, well played and well synched. The “symphony” aspect of the film makes a lot more sense with this accompaniment.

Melodie der Welt is credited with being the first German sound feature. It’s a lot simpler than Berlin. Financed  by a steamship company, it purports to follow a sailor on a huge liner around the world to exotic countries. Ruttmann takes footage from English, Greek, Japanese, and other cultures and cuts them together by topic to emphasize the similarities. Religious ceremonies are compared, military exercises intercut, children’s games assembled into a montage, people playing music (right), and so on. The laudable goal is to make customs of “exotic” peoples seem less remote and strange by showing them doing things that are not all that different from what Europeans do. A pity this was happening just before the Nazis sought to eradicate such notions of universal humanity.

by a steamship company, it purports to follow a sailor on a huge liner around the world to exotic countries. Ruttmann takes footage from English, Greek, Japanese, and other cultures and cuts them together by topic to emphasize the similarities. Religious ceremonies are compared, military exercises intercut, children’s games assembled into a montage, people playing music (right), and so on. The laudable goal is to make customs of “exotic” peoples seem less remote and strange by showing them doing things that are not all that different from what Europeans do. A pity this was happening just before the Nazis sought to eradicate such notions of universal humanity.

This set is just about ideal as a presentation of Ruttmann’s work in this period. I hope that someday a print of his 1933 fiction feature, Acciaio, will become available. It was made in Italy, and although it has been many years since I’ve seen it, I remember it as a very good film with spectacular documentary-style scenes shot in a steel mill—and as a forerunner of Neorealism.

David and I look forward to seeing Stefan at next summer’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna and to whatever new treasures he and his fellow archivists have restored.

Three nights of a dreamer

DB here:

The close-up blogathon launched by Matt Zoller Seitz is over, but it contains enough specimens and analyses for a hefty book. It also inspired Jim Emerson to devote a cine-lyric to the close-up. I missed the deadline, so I suppose that this constitutes my sideways contribution to Matt’s enterprise.

Sideways, because a full-blown analysis of In the City of Sylvia (En la ciudad de Sylvia; Dans la ville de Sylvie) would be a breach of decorum. Most people haven’t heard of this new film by José Luis Guerin, let alone seen it. I saw it at the Vancouver festival in September, and it will make its way through the festival circuit over the coming months and should show up on cable or DVD thereafter. But apart from calling attention to it as a remarkable film, I want to look at one of its most absorbing sequences and suggest some of its originality. Lee Marshall has already pointed out one of Sylvia‘s arresting features:

Guerin seems to have created pure drama without recourse to story. We’re always taught that story is the engine of drama. Not here: somehow Guerin has created an almost plotless film that has the dramatic tension of vintage Hitchcock. (1)

Although the story situation is slight, the tension we feel springs partly from vivid stylistic patterns. In other words: Minimal and uncertain story action is heightened by engaging visual narration. This narration in turn derives its power from one of the most traditional devices of filmic storytelling.

Consider the other person’s point of view

The point-of-view shot is a mainstay of cinematic storytelling, and its history is an intriguing one. Many of the earliest examples we have are motivated as views through optical gadgets. Two films by the Englishman G. A. Smith, both from 1900, handily show the options. Grandma’s Reading Glass justifies the point-of-view image as what the boy sees when he peers at granny through her big magnifier.

Smith’s As Seen through a Telescope motivates the cut-in POV shot as what our dirty old man in the foreground has an eye for.

Fairly soon, this use of the magnifying POV shot was mingling with more straightforward ones. In The Birth of a Nation (1915), D. W. Griffith offers a rough-edged example. When the Stoneman brother and sister visit Ford’s Theatre on the night of Lincoln’s assassination, we see Elsie pointing out the famous actor John Wilkes Booth.

Booth is framed in an iris, which Griffith often uses to underscore an important image. But when Elsie studies Booth through her opera glasses, Griffith, usually not fastidious about such things, supplies the same irised image, now doing duty for the sort of magnifier-masking we get in the Smith films.

Presumably a more consistent technique would show Booth in long shot first, without the iris, and reserve the optical masking for replicating the view through the opera glasses. This is what happens in Ernst Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan (1926), which contains a sequence built entirely around crisscrossed character looks. (1)

The woman of the world Mrs. Erlynne arrives at the racetrack and creates a stir, causing many men to watch her from all over the grandstand.

Note that Lubitsch has gone beyond Griffith by fitting the angle of Shot B to the viewer’s orientation, looking up. There are so many POV shots that at one point Lubitsch simply shows her from different angles and deletes the shots of each watching man.

This is a fascinating example of a process we often see in stylistic history. An “overlearned” visual convention can be treated elliptically; the filmmaker can leave out bits and we’ll fill them in. The binocular masking suffices to let us know that Mrs. Erlynne is being studied from afar. Moreover, Lubitsch gets an expressive bonus from being so concise. Now it doesn’t matter who’s watching, just that somebody is—actually, a lot of somebodies.

Later, after much more byplay with people looking at one another and misunderstanding what they see, Mrs. Erlynne sits down. Three gossips have been studying her, but now their view is blocked. So one gossip has to twist around to spy on her, and Lubitsch obligingly gives us a slightly tipped point-of-view framing—a full shot, without masking.

Adjusting her binoculars, the gossip is able to get a bigger view of Mrs. Erlynne, and she racks focus gleefully to catch a gray hair peeping out.

The visual narration in this sequence, already perfectly modulated, supplies the stylistic premise for Hitchcock’s Rear Window and all of its progeny, most recently Disturbia (2007). What might be overlooked is that by the 1920s the view through a device—field glasses, a microscope, a surveillance camera—had become a special, marked case. From then till now, the default POV pattern is the simple shot of a character looking, followed by an unadorned shot of what that person sees, from more or less the correct standpoint. Lubitsch’s sideways shot of the gossip’s view of Mrs. Erlynne, casually introduced, exemplifies the modern norm for presenting a character’s vision, and it’s so common that we seldom notice it.

POV shots: The basics

In his book Point of View in the Cinema, Edward Branigan itemizes the cues that the filmmaker can manipulate in creating a POV construction. (2) To simplify somewhat: Shot A shows a point in space and a character glance from that point. Shot B is taken from a camera position more or less approximating the point in A, and it shows an object. The shot-change presumes temporal continuity between A and B, and we assume as well that the character is aware of the object shown in B.

This seems like a complicated way of stating the obvious, but by teasing these elements apart, Branigan shows that each one can be manipulated in intriguing ways. For example, you can create a disorienting moment by violating the condition of temporal continuity. Ozu does this in Early Summer (1951), when Noriko and Aya decide to peek in at the man Noriko almost married. The two women tiptoe down a hall toward us as the camera tracks slowly backward. Ozu cuts to a forward-tracking shot that momentarily suggests a reverse angle POV on the corridor.

In fact, however, the camera movement is revealed to be the first shot of a new scene, among different characters, and we won’t ever see the man the two women went to spy on.

Here’s another interesting case, not cited by Branigan. In Halloween (1978), John Carpenter shows Laurie looking out a window and seeing Michael Myers in his mask, standing between fluttering washlines.

Cut back to Laurie, now frowning slightly.

Cut to a second POV shot; but now Michael has vanished.

This simple change in shot B’s object, Michael himself, has an uncanny effect. Did Michael just walk away from the washline? If so, this is an odd way to present it. Why not show him walking away? Alternatively, did he just disappear? Surely not; Laurie would be shocked. Carpenter wins twice over. Without obviously violating realism or directly showing that Michael has supernatural powers, he gives Michael the ability to come and go in a ghostly fashion. By the end of the film, when he miraculously disappears after a fall that would kill an ordinary person, we are prepared to believe that he is indeed, as Dr. Sam Loomis says, the Boogyman.

Who is Sylvia? What is she that all the swains commend her?

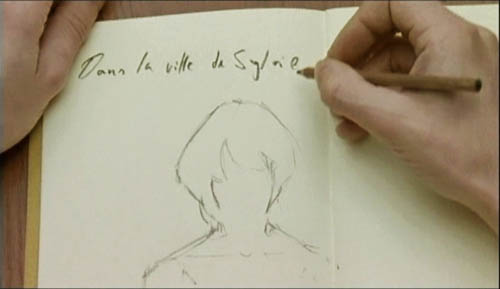

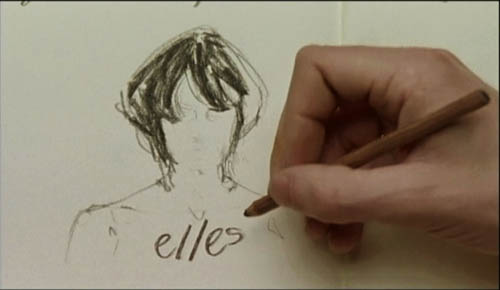

In the City of Sylvia centers on a young man staying at a hotel. We’re given no reason why he’s visiting the city, and no backstory about him. One day he’s sitting at a café. Now, across nearly twenty minutes of screen time he watches women and idly sketches them.

The sequence is a pleasure to watch, partly because of the constant refreshing of the image with faces, nearly all of them gorgeous, most of them female. Either Strasbourg has an extraordinary gene pool, or this café attracts only Ralph Lauren models. Yet the scene builds curiosity and suspense too, thanks to Guerin’s sustained and varied use of optical POV. He gives us an almost dialogue-free exploration of a cinematic space through one character’s optical viewpoint. (Stop reading here if you don’t want to know anything more about the film before you see it.)

The young man, known in Guerin’s companion film Unas fotos en la ciudad del Sylvia as the Dreamer, is almost expressionless as he scans the women’s faces. Slight shifts of his glance are accentuated by his habit of turning his head but keeping his eyes fixed. In over a hundred shots, Guerin uses some ingenious cinematic means to tease us into ever-greater absorption in the Dreamer’s visual grazing.

Fairly far into the sequence, Guerin gives us more or less the orthodox POV construction. The Dreamer looks at one woman at a table, and we see her return his look.

But here shot B isn’t really clean: the hands of the woman on the left sometimes block our view of the principal woman. This obtrusiveness is one of Guerin’s most basic strategies in the sequence. Inevitably, in passages before and after the cut I just showed, what the Dreamer is looking at is partially hidden in layers of faces and body parts.

Our prototype of the POV cut presumes a more or less single ‘point’ we are watching in shot B, but throughout this scene Guerin plays with this cue. He tantalizes us with several points to be observed, and he often obscures the most important ones. He also creates some startling juxtapositions. Near the very start we get this shot, which may or may not be the Dreamer’s POV.

By making the background girl seem to kiss the foreground guy, Guerin, as Eisenstein would say, “christens” his sequence. In effect, the image says: Watch out! Layered space will become important! When I saw this shot, I nearly jumped out of my seat.

The Dreamer is treated no differently, at least at the start. In most movies, the POV construction is set up with a clear, clean framing of our looker in shot A. Here, though, at the start of the scene Guerin peels away layers to get to our man. For the first six shots of the café, we don’t know he’s on the scene. Then he’s shown out of focus, in the background of more prominent action. The woman in the foreground has been primed to be the shot’s subject. At the moment she shifts her gaze and we try to read her expression, a second woman on the distant right shifts aside to reveal the Dreamer behind her.

Surely this is the most unemphatic entry of a protagonist we’ve seen in a while! Guerin is able to add planes to block the main ‘point’ of shot B because he’s working with long lenses, a crowded space, and careful choreography. Even focus plays a role, as in this case; our Dreamer is pretty hazy.

One upshot of this strategy is that we’re plunged into a “cubistic” space, in which slightly varied camera angles pick up bits of space we’ve seen in earlier combinations and oblige us to assemble it all in our head. Be thankful for the guy in the blue shirt above, for he plays an anchoring role in several setups that would otherwise float free.

It’s hard to convey in stills how much fascination and frustration that this teasing style creates. Like the Dreamer, we’re given only glimpses of the women, and even though we don’t know his purposes—is he just an artist in search of beauty? a serial killer picking out victims?—the partial views lure us at several levels. We try to complete the faces. We try to infer the women’s state of mind from their expressions and gestures, which are far more animated than our Dreamer’s.

And a search for story plays a part here. We’re primed for some action to start, and we browse through these shots looking for anything that might initiate it. Each face the Dreamer spots promises to kick-start a plot: when the Dreamer gets a full view of one of these women, perhaps things will get going.

Without giving away every detail, I’ll just say that the sequence has a strong visual arc as the Dreamer starts paying more and more attention to certain women. And just as he finally gets a full view of one fabulous face, his attention wanders to . . . another layer, this time one inside the café.

As he gapes at the woman inside, layers pile up, creating a cubistic climax of all the optical obstructions we’ve encountered.

The motif of reflections will take over the rest of the film’s visual design, and eventually we’ll see that some of the Dreamer’s drawings evoke the piled-up and sliced-up faces in the café shots.

Later in the film, the Dreamer will explain why he’s in the city and why he’s scanning women. We’ll have a tram ride that Guerin compares with Sunrise, and a scene in a music club that not only parallels the café sequence but evokes Manet. We’ll also have occasion to compare this film with Bresson’s Four Nights of a Dreamer, a citation signaled from the outset.

All that is to come. Even if the later scenes weren’t as compelling as they are, this café sequence would make Sylvia one of the most adventurous films I’ve seen this year. By revising the simple, long-lived POV schema, Guerin has made it yield fresh feelings and implications. Like Lubitsch’s racetrack scene, this imaginative sequence provokes the jubilation you feel in the presence of calm, precise artistry.

(1) Lee Marshall, “Past Perfect,” Screen International (19 October 2007): 27. The web version is here, but it may require a subscription.

(2) I analyze the visual narration of Lady Windermere, which I think deserves to be ranked with Potemkin and Sunrise, in Narration in the Fiction Film (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985), 178-186.

(3) Edward R. Branigan, Point of View in the Cinema: A Theory of Narration and Subjectivity in Classical Film (The Hague: Mouton, 1985), 102-121.

Arrivederci Ritrovato

The three chiefs of Cinema Ritrovato: Peter von Bagh and Gianluca Farinelli strategize, while Guy Borlée does some heavy lifting.

Our last days at Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato were as busy as the first ones. Inevitably, choices, choices. Invasion of the Body Snatchers in a rare SuperScope print, or Asta Nielsen as Hamlet? Emilio Fernandez’s melodrama Enamorada (1946) or a 1907 version of Little Red Riding Hood, with a big dog playing the Wolf? You can’t see it all, but we offer some notes on some of the choices we made.

I can’t say that I am a great fan of Frank Borzage’s films of the 1930s and 1940s. For me his great period was the mid- to late 1920s. 7th Heaven (1927) somehow manages to climb beyond its blatant sentimentality, much as the hero and heroine ascend the stairs of their tenement apartment house, and earns our emotional investment in their transcendent love. For me, Lazybones (1925) and Lucky Star (1929) were the revelations of the Borzage retrospective during the 1992 Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone. It is a true pity that both remain largely unknown.

Borzage’s No Greater Glory (1934) was shown in a stunning print supplied by Sony Columbia. It didn’t fall into any of this year’s themes but was simply one of the “Ritrovati & Restaurati” items. The film deals with rival youth gangs in Budapest who organize themselves along strict military lines. Purportedly an anti-war tale, it manages to make the self-imposed discipline and even gallantry of the boys seem almost redemptive. I found the young hero, a scrawny but brave lad who struggles to be worthy of promotion within the ranks of his chosen gang, a bit too calculated to tug at the heartstrings. Still, it was entertaining, and the print showed it—and especially Joseph H. August’s cinematography—off to the best possible advantage. (KT)

While Kristin was watching Borzage, I decided to revisit Ilya Trauberg’s Goluboi Express (1929), one of the least known of the Soviet Montage films. Like Pudovkin’s Storm over Asia, it’s an attack on Western imperialism. Chinese, many sold into servitude, are packed into the rear cars of the train, while colonialists loll around up front. Two western soldiers of fortune attack a Chinese girl, and a young Chinese tries to defend her. This launches a prolonged battle and chase while the train roars on. By 1929, Trauberg had absorbed the lessons in cutting taught by Kuleshov, Eisenstein, and Pudovkin, and he adds his own imaginative touches. The taut construction and torrential editing (over 1400 shots in less than an hour) create an electrifying experience.

This particular version is an intriguing rarity. In his introduction, Bernard Eisenschitz explained that Soviet authorities persuaded Abel Gance to distribute the film in France. Gance recut it to avoid censorship, and he commissioned musical accompaniment by Edmund Meisel, the experimental composer who scored Battleship Potemkin. Meisel’s score amplifies and sharpens Trauberg’s hammering visuals. (DB)

The book room was running for only about half the festival, so I was glad I nabbed my consumer durables early. Many high points, including a fascinating DVD collection of Marey films, but the most memorable, if only because of the struggle to carry it back home, is This Film is Dangerous. Published by the International Federation of Film Archives, this colossal book appears to present everything you wanted to know about this incendiary filmstock. It includes discussions of how nitrate came to be an ingredient of film, how the nitrate preservation movement (“Nitrate won’t wait”) started, case histories of restorations, poems in praise of nitrate, a chronology of nitrate fires, and an anonymous contribution called “Nitrate Pussy.” In all, virtually a film geek’s bathroom book, although its bulk demands a large lap. It doesn’t yet seem to be available on the FIAF website, but it should be soon.

Speaking of swag and plunder, Dan Nissen of the Danish Film Institute kindly gave me a copy of their latest DVD publication, the first of several volumes devoted to Jørgen Leth. It’s a handsome production and sure to increase interest in the man behind The Perfect Human and the target of Lars von Trier’s painstaking abuse in The Five Obstructions. It’s available at the DFI website. (DB)

Although Michael Curtiz’s 1929 epic Noah’s Ark has been shown at various festivals in recent years, I somehow had always managed to miss it. Perhaps this was just as well, since the print shown in Bologna as part of the salute to Curtiz is longer than most and has the original sound restored from the Vitaphone records. (More often the film has been shown in its silent version.) Piecing together bits from several release prints held in different archives, something approximating the 1929 release version has been reassembled and matched to the sound. The credits in the program—“Print restored by YCM laboratories, funded by Turner Entertainment Company and AT&T in collaboration with La Cinémathèque Française and The Library of Congress”—hints at the complexity of the task.

Like The Jazz Singer and other early talkies, Noah’s Ark has long stretches of purely musical accompaniment. At intervals, though, characters suddenly start speaking, usually at the lugubrious pace typical of performances at the dawn of sound. The effect is startling, especially when the transition happens within a scene. Such switches proved jarring to the reviewers of the day, but the chance to see a film hovering between silent and sound can be fascinating to a modern viewer. The pacifist message of Noah’s Ark reflects a general anti-war sentiment in Hollywood films of the 1920s and 1930s—a healthy reminder of a day when the majority of good, patriotic Americans could take a dim view of warfare. The film’s ending, in fact, optimistically declares that the Great War had put an end to all wars. (KT)

Having written a book on Ernst Lubitsch’s silent features, Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood, I was particularly interested in a dossier on the director. It included a reconstruction of Die Flamme (1922), of which only one reel survives, using publicity photos, set designs, and descriptive intertitles. Though still short at only 44 minutes, this version gives a good sense of the plot, which was certainly not evident from the existing footage.

We have long known that Lubitsch’s intended first project in Hollywood was to be a version of Faust with Mary Pickford as Marguerite. That fell through, but it went far enough that screen tests were made. Twelve minutes of tests for a series of actors trying out for the part of Mephistopheles were shown. These were not exactly a revelation, but they do shed light on this transitional moment in the director’s career. (KT)

What do we do with a terrible movie by a sublime filmmaker? I’d argue that at least three directors achieved greatness in the years before 1920: D. W. Griffith, Louis Feuillade, and Victor Sjöström. Sjöström’s Ingeborg Holm (1913), Terje Vigen (1917), The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), The Outlaw and His Wife (1918), and Sons of Ingmar (1919) remain deeply moving and cinematically inventive. Sjöström moved smoothly from the fixed camera, long-take “tableau” style of the early 1910s to profound mastery of continuity editing on the US model only a few years later. He continued into the 1920s with such key American films as The Scarlet Letter (1926) and The Wind (1928).

So it’s saddening to report that A Lady to Love (1930) is a turkey. Edward G. Robinson, in full hambone overreach, plays an Italian-American grape farmer who seems to be flourishing despite the Volstead Act. Tony brings a down-at-heel waitress from the big city to be his wife, and she grows to love him, despite a little indiscretion involving Tony’s best friend. The sort of inert stage adaptation that gave talkies a bad name, A Lady to Love is solely for completists (of which Cinema Ritrovato boasts many). It was Sjöström’s last Hollywood picture. (DB)

The programs of 1907 films continued to yield treasures. Max Linder’s career got going that year, and he had not yet settled into the debonair, top-hatted persona that would within a few years become so familiar. In the simple and not terribly funny Débuts d’un patineur, he plays a novice ice-skater reduced to tears at by the film’s end, and in the more amusing Pitou bonne d’enfants Linder is a bumbling soldier who loses a baby confided to his care by his nursemaid sweetheart. The same program contained Louis Feuillade’s ever-popular Le Thé chez la concierge, where the guests start carousing so loudly that they drown out the bell rung by tenants trying to get into the house.

There were many early attempts to record synchronous sound, though all too often the accompanying discs have been lost even if the image track survives. The 1907 films contained a few such, but one, La Marseillaise, had its singer’s original voice, remarkably clear and perfectly synchronized. The result was an unusually poignant and vivid sense of a link to a hundred-year-old performance, an immediacy that went beyond what most silent films can convey, wonderful though they might be.

A familiar but welcome short was La course aux potirons (“The Pumpkin Chase”), one of the great entries in the very familiar genre of the day, the chase film. Special effects allow a wagon-load of pumpkins (looking like they were probably constructed from old tires) to bounce along city streets, up a chimney, and through windows, followed by the usual growing group of passersby. The inclusion of a donkey, duly hauled through the windows and up the chimney, makes the whole pursuit far funnier than in most such films.

Finally, the inclusion of a series of films about bomb-throwing anarchists, another common genre of the day, reminds us that the current international situation is not altogether a new one. (KT)

The DVD awards singled out efforts to making unusual cinema available in the DVD format. The top prize, Best DVD, was won by the Ernst Lubitsch collection, from Transitfilm and the Murnau Stiftung (available, with some variations, on Kino in the US). The committee commended it as “a model in the elegant packaging of rare materials in a form that is certain to attract new audiences.”

Anke Wilkening of the Murnau Stiftung accepts the award for best DVD.

Other awards: L’amore in città (Minerva, Italy), Best discovery; Seven Samurai (Criterion, US), Best Extras; the series on German cinema published by the Munich Film Archive, Best Series; and Akerman films of the 1970s (Carlotta, France), the French Naruse set (Wild Side) and the British Naruse set (Eureka), Best Box Sets.

Peter von Bagh commented that DVD producers are continuing the traditional work of film archives, and they often go beyond what archives can afford to tackle. Ironically, we sometimes find ourselves in the position of having excellent DVD versions of films that don’t exist in equally good prints. (DB)

Finally, some snapshots. Glancing around the book room, you’ll see Sawako Ogawa and Hiroshi Komatsu pouncing on items.

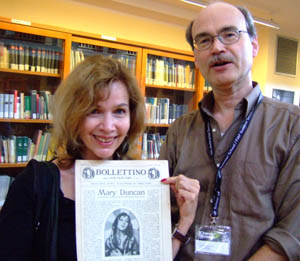

Not to be left behind, Janet Bergstrom and Richard Koszarski display Janet’s find.

Every year, Frank Kessler‘s birthday occurs during Ritrovato; this year was his fiftieth, and so Sabine Lenk made it a special treat.

At another meal, Danish film archivist Thomas Christensen, who really ought to know better, fends off the camera’s magical powers.

Same meal: shellfish and pasta sacrificed in a good cause.

Danish film historian Casper Tybjerg and Kristin sample gelato. Later I ate the one in the middle.

On the final evening, the film cans are wheeled out. Ci vediamo l’anno prossimo!

Can you spot all the auteurs in this picture?

DB here:

Some movies consist of several distinct episodes, each directed by a different filmmaker and all focused on a single theme. I’ve heard them called anthology films, omnibus films, and portmanteau films.

The earliest one I know is If I Had a Million (1932); later, Hollywood offered us Ziegfeld Follies (1946) and O. Henry’s Full House (1952). The Brits gave us the horror anthology Dead of Night (1945). Still, I think we associate the form chiefly with European cinema of the 1950s and 1960s. We got Love in the City (1953), Amori di mezzo secolo (1954), The Seven Deadly Sins (1962), RoGoPaG (1963), Les plus belles escroqueries du monde (1964), Paris vu par . . . (1965), Three Faces of Woman (1965), The World’s Oldest Trade (1967), and Amore e rabbia (1969).

Why the emergence of omnibus movies at this point in history? Some causes are surely financial. Most high-budget European films of the period had to be cross-national coproductions. Bringing in directors from several different countries could help guarantee funding under EU auspices and participating nations’ subsidy schemes. Just as important, the anthology format appeared when the festival scene was starting to become a vast clearing house for international film trade.

Although you can argue that many people seeing If I Had a Million would recognize the Lubitsch episode, Hollywood’s use of the form didn’t stress directorial differences. But as the Euro auteur was becoming a marketable commodity in the postwar era, a collection of short films could sell if they were signed by big-name filmmakers. “Paris As Seen by…” signals the importance of the different directorial approaches, and the very title of RoGoPaG invokes Rossellini, Godard, and Pasolini as brand-name labels. (Granted, the final G, Hugo Gregoretti, didn’t add much to the deal.)

For full enjoyment, the 1960s portmanteau film requires a degree of specialized film knowledge. At one level, we enjoy varied treatments of a theme, but at another we’re supposed to recognize each director’s personal vision, as we know it from other films. Even political-commentary portmanteau films like Far from Vietnam (1967), Lucía (1968), and Germany in Autumn (1978) gathered international attention because of the name recognition of the filmmakers who participated. The same branding operates in New York Stories (1989) and, more openly, in the documentary 12 registri per 12 città (“12 Directors for 12 Cities,” 1989).

The format has returned recently. We’ve had 11’09”01—Sept. 11 (2002), Eros (2004), Tickets (2005), and Paris, je t’aime (2006), the last virtually a rebooting of Paris vu par . . . . As we’d expect, such films continue to highlight the personal signatures of festival familiars. But we can spot some new twists too.

For one thing, the unifying idea may be formal as well as thematic. The episodes of 11’09”01 were all obliged to be the same length, eleven minutes, nine seconds, and one frame. Lumière et cie (1995) not only celebrated the centenary of film but obliged the directors to make their entries with a Lumière camera, to shoot without sync sound, to shoot no more than three takes, and to restrict the length to 52 seconds, the approximate running time of the earliest films. The Lumière homage also introduces the key themes of cinema and cinephilia, an angle that doesn’t seem prominent in the 1960s omnibus movies.

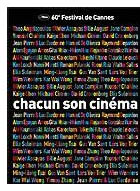

The most prominent portmanteau film so far this year fits snugly into current trends. As Anthony Kaufman writes, “Chacun son cinéma. . . showcases a range of filmmaking aesthetics, and for the most part, the program is a dazzling and memorable array of current auteur cinema.” As in other eras, we get a stylistic buffet; as in recent years, we find formal constraints and the theme of cinephilia. Commissioned for Cannes’ sixtieth anniversary by festival head Giles Jacob, the project restricts filmmakers to three minutes per episode and dictates the subject: “their state of mind of the moment as inspired by the motion picture theater.” The result was 33 short films about the joys and sorrows of film viewing and, to some degree, an extended commercial promoting the cultural value of the Cannes event.

The most prominent portmanteau film so far this year fits snugly into current trends. As Anthony Kaufman writes, “Chacun son cinéma. . . showcases a range of filmmaking aesthetics, and for the most part, the program is a dazzling and memorable array of current auteur cinema.” As in other eras, we get a stylistic buffet; as in recent years, we find formal constraints and the theme of cinephilia. Commissioned for Cannes’ sixtieth anniversary by festival head Giles Jacob, the project restricts filmmakers to three minutes per episode and dictates the subject: “their state of mind of the moment as inspired by the motion picture theater.” The result was 33 short films about the joys and sorrows of film viewing and, to some degree, an extended commercial promoting the cultural value of the Cannes event.

A half-dozen things strike me while watching the French DVD version (which has English subtitles but is unaccountably lacking the Coens’ entry). Most notable, I suppose, is the way that many of the shorts replay tendencies that are characteristic of art cinema generally (1).

1. Cinema invokes eroticism . . . We get a dreamy Wong Kar-wai scene of a man watching, or recalling, heavy petting in the theatre. Polanski’s episode plays amusingly on the similarity of orgasmic moans and painful groans. Gus van Sant’s First Kiss reinvents Sherlock Jr., while the Dardenne brothers give us a tight tale of hands in the dark. Olivier Assayas’ episode, a crisp piece of filmmaking, reveals its l’amour fou at the very end. Angelopoulos makes clever use of the Kuleshov effect to create a touching exchange between Jeanne Moreau and the lamented Mastroianni.

2. . . . and childhood, especially for the Chinese directors, who haven’t exactly risen to the occasion here. The international art film has long traded on the appeal of kids, but the treatment of them in these episodes is remarkably banal. Tsai Ming-liang, who already passed his benediction for classic cinema in Goodbye, Dragon Inn, gives us a dream of a family reunited at the pictures. Chen Kaige shows children watching—hold on now—a silent Chaplin film. Hou Hsiao-hsien provides a sepia-toned flashback to going to the movies in Taiwan, while Zhang Yimou takes us to movie night in a Mainland village. At least the Hou episode opens on a lengthy shot that nicely decenters areas of interest in a busy street scene.

3. The cinema is on the decline . . . . One way to interpret Kitano Takeshi’s cryptic sequence is that films, even his own Kids’ Return, are little more than an anachronism today. More explicitly, David Cronenberg’s single-take close-up, captured by a surveillance camera shows himself as the world’s last surviving Jew, on the threshold of suicide in a movie house.

4. . . . yet it holds us in a magical spell. Some directors celebrate the simple folk at the movies. Claude Lelouch’s parents watch Top Hat and fall in love. Raymond Depardon takes us to a rooftop cinema in Alexandria, and Wenders shows a Congolese village running Black Hawk Down on video (more kids, but this time to disturb us). Kaurismaki seems to be poking fun at this arthouse commonplace by showing foundry workers blankly watching a rather different image of workers at the end of the day. The cinema, Ruiz and González Iñárritu suggest, mesmerizes even blind people.

Walter Salles provides a charming, deflating musical dialogue (below) that might be called Far from Cannes, showing that this festival casts a quasi-religious spell felt across the world. In my favorite section, Kiarostami gives us shots of women responding to Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet. The image/sound pairing hints at their own thwarted loves, while certain lines, such as “Where be these enemies?,” seem addressed to Westerners who try to dehumanize the people of Iran.

5. Film can be silly. Von Trier, decked out in a tux, silences a businessman through extreme means, and the rest of the audience hardly notices. Jane Campion, in an awkward episode, reveals a bug living in a theatre speaker. Probably the funniest contribution shows a mute Elia Suleiman preparing for a Q & A session after a screening. There are more gags in this three minutes than in all the other episodes put together.

5. Lest we forget . . . This couldn’t help but be a nostalgia exercise, encouraging filmmakers to muse on their lives in cinema. This theme recalls Cinema Paradiso, Scola’s Splendor, and all the other films soaked in the melancholy sweetness of movie memories. Moretti (top image above), gives us an anecdotal monologue, while Youssef Chahine unashamedly thanks Cannes for giving him an award ten years ago. The most formally ingenious entry here is Atom Egoyan’s tale of a couple sitting in different screenings while texting each other. Eventually one grabs an image from La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc and passes it along, creating a parallel to what’s happening in the other film (Egoyan’s The Adjuster).

In particular, there’s nostalgia for the golden age of auteurs, the very period when the anthology film gained its purchase. Chacun son cinéma is dedicated to Fellini, and Konchalovsky’s episode centers on 8 ½. Bresson and Godard are the most frequently referenced directors. (More generally, in our new century Bresson seems to have become the prototype of the serious filmmaker.) Other icons of the 1960s, such as Mastroianni and Anna Karina, keep popping up.

6. Spot the auteur. Most episodes don’t reveal the director’s name until the end, so the cinephilia takes on a suspenseful dimension, forcing you to guess who filmed the bit you’re watching. You also have to identify movies within the movies on the basis of clips and soundtracks. It’s a great game for arthouse aficionados, but it also highlights festival cinema’s reliance on the cult of the director and the organic unity of his/her body of work.

Suppose that all these films omitted the director’s name and replaced the recognizable players with nobodies. Would any of these episodes have been accepted for Cannes’ short film programs? Probably not, but we shouldn’t be cynical about this. Clearly artworks can gain in interest by virtue of their place in history or an artist’s career. Renoir’s Sur un air de Charleston (1927), Bresson’s Les affaires publiques (1934), Dreyer’s They Caught the Ferry (1948), and Fassinder’s episode in Germany in Autumn are not masterpieces, but these shorts show fresh sides of great filmmakers, and our understanding of their accomplishment is enriched by having them.

So we’re right to recognize the director’s career as a meaningful whole. But we should also recognize that today such careers continue thanks to a distinct system of marketing. At the Cannes site, Rauol Ruiz says: “It’s a delight to be a preferred filmmaker and especially a favored filmmaker of Gilles Jacob.” The system depends on reciprocity. “Without the auteurs,” says Jacob, “there wouldn’t be a festival.” (2) In turn, auteurs are obligated to festival gatekeepers and tastemakers, the powerful critics, programmers, and impresarios. The filmmaker knows the drill. You showed my film last year, so yes, I’ll sit on a jury or offer a master class or show up on the red carpet this year.

We’re told by Anne Thompson that a more complete DVD edition, including the David Lynch entry, will be available before Christmas. That gesture makes the disc I bought the equivalent of the plain-vanilla DVD of a blockbuster that will be followed at the right moment by the Deluxe Edition. Who says the art cinema operates above pressures of business and the market?

(1) I discuss the idea of art cinema in a 1979 article, “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice,” revised in the forthcoming Poetics of Cinema.

(2) Nancy Tartaglione-Vialatte, “‘Without the auteurs there wouldn’t be a festival,'” Screen International (May 18-31, 2007), p. 15. See also the accompanying article by Nick Roddick, “The bucks start here,” pp. 14-15. These are available online to subscribers.

PS: Speaking of Cannes and the art cinema, I wrote an essay about camerawork in contemporary Danish film for the festival issue of the Danish Film Institute magazine. It’s now online here (pp 22-26). And speaking of Danish filmmakers. . . .

Atom Egoyan, Artaud Double Bill.