Archive for the 'Directors: Mizoguchi Kenji' Category

How to hypnotize the viewer: Mizoguchi’s STREET OF SHAME on the Criterion Channel

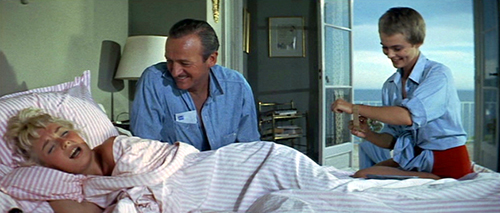

Street of Shame (1956).

Filmmakers must study the film image and its potential for expression. This is our primary responsibility.

Kenji Mizoguchi

DB here:

So much of contemporary film and TV takes pictorial space for granted. Yes, The Avengers: Endgame stuffs its frame with, well, stuff, but you’re seldom given time to see everything. Even in films not so dominated by CGI, if the the actors’ faces and gestures come across and you can hear the line readings, that’s pretty much enough. Most of the rest is there to fill out the very wide frame.

“Wait,” I hear someone saying. “Thanks to Steadicam, directors use camera movements to sweep through space all the time.” Yeah, that’s just my point: They sweep through. We’re following characters’ backs or fronts, not exploring space as such. Very seldom do we get a chance to probe what’s revealed, except in carefully wrought movies like Sunset (which tease you into trying to discern what’s not even in focus).

Moreover, today the pace of the editing is so fast, even in an “intimate” movie like Booksmart, that the actors’ faces dominate everything. For fifty years many directors have been “shooting for the box,” shoving their actors into close-ups that will read on TV, now on computers and smartphones. Like the endlessly moving camera, the big heads and the quick cuts refresh the image often enough to hold our interest in a distracting environment.

Granted, most filmmakers now supplement their fast-cut, rapid-pan close-ups with an occasional landscape shot that can look pretty, in a calendar-image sort of way. Overhead shots, now facilitated by drones, swoop us through the towering corridors of The City or across a swath of forest in a way that is undeniably impressive. This convention doesn’t count, for me, as pictorial intelligence unless somebody like Tony Scott does something, however nutty, with it.

I’m not against these stylistic choices per se; every style is valid if it’s pursued with imagination, rigor, and delicacy. Nor am I suggesting that the other extreme, so-called slow cinema, is inherently more virtuous. Long unmoving takes can be paralyzingly dull. Ozu made fast cutting just as “contemplative” as Hou or Tarr, because he knew how to design pictures.

It’s just that the norms of intensified continuity and the “free camera” have overwhelmingly dominated current practice. It’s worth remembering other ways moving pictures can be. One way to do that is to revisit film history, and the work of Mizoguchi Kenji is an ideal place to start.

His Street of Shame (1956) is the subject of this month’s Observations entry on the Criterion Channel. In it, I invite you to join me in attending a master class in staging.

The theme is Mizoguchi’s perennial one, that of the ways in which women succumb to or resist their oppression in a patriarchal society. We’re in the Dreamland brothel, where five–eventually, six–women are working at the very moment the government debates eliminating prostitution. Mizoguchi shows how they both cooperate and compete, trying to quit, deploying different strategies for managing their clients, and just getting by. It’s all done through what Mizoguchi called the “hypnotic power” of carefully choreographed images.

A personal note

In a way, Mizoguchi made me a film teacher.

During the week of 25 September 1969, what could you have have seen in Manhattan? I Am Curious: Yellow, La Chinoise, Closely Watched Trains, Miracle in Milan, Hell’s Angels ’69, Who’s That Knocking at My Door, Midnight Cowboy, The Killing of Sister George, De Sade, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, One Second in Montreal, <—->, Take the Money and Run, Alice’s Restaurant, Medium Cool, In the Year of the Pig, Easy Rider, Putney Swope, and programs of Kubelka and Jack Smith movies. There were many double bills on offer: The Wild Bunch and Ride the High Country, Yellow Submarine and The Gold Rush, King Kong and The Lady Vanishes, Seven Samurai and The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail, Monterey Pop and Don’t Look Back, The Deadly Affair and Funeral in Berlin, Little Sister and Alice in Acidland, Lonesome Cowboys and Flesh.

Yeah, those were the days before cable TV, home video, and streaming.

Yeah, those were the days before cable TV, home video, and streaming.

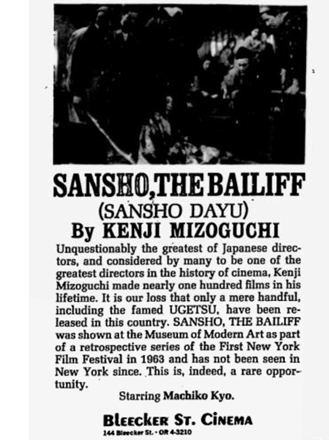

In the city for only a few hours, I didn’t go to any of those shows. There was yet another double bill at the Bleecker but I could catch only one title: not Lola Montès (I would see that in Paris a year later), but Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff.

As a teenager I had read books about cinema (Welles, Hitchcock) and in college I’d written movie reviews and participated in a film club. Now, newly graduated, I was teaching high school. The only Japanese films I’d seen were the Kurosawa standards our club programmed. Despite planning for a career in high-school teaching, I thought about film most of the time. In the pages of Film Culture and Movie I had read about Mizoguchi.

I came out of Sansho with tears streaming down my cheeks. I heard two young men in the lobby talking about the film. Did they go to NYU or Columbia or some such place? All I know was that they loved Mizoguchi’s long takes, as I did. Somehow, those takes had to be connected to the way the movie hit me. I thought something like: I’d like to study this sort of thing.

I returned to my apartment and began figuring out how to apply to graduate school.

Mizoguchi was still largely unknown, certainly unappreciated. The New York Times didn’t get around to reviewing Sansho until it resurfaced in a later run. Roger Greenspun made up for the neglect with a a gracious note.

“The Bailiff” is a film of breathtaking visual beauty, but the conditions of that beauty also change–from the etheral delicacy of its beginning (before the kidnapping), through the dark masses of the Bailiff’s compound, to the ordered perspectives of Kyoto and the governor’s palace, and finally to the spare symbolic horizons at the end.

In effect, it moves from easy poetry to difficult poetry. Its impulses, which are profound but not transcendental, follow an esthetic program that is also a moral progression, and that emerges, with supreme lucidity, only from the greatest art.

People talked that way then, with good reason.

Choreography all the way down

I didn’t see much Mizoguchi in the years following. There wasn’t much available. (And Ozu was unknown to us.) I did see Ugetsu and Street of Shame, though they didn’t grab me as fast as Sansho had. Fairly soon, though, New Yorker Films and Audio-Brandon made prints of other Mizoguchi titles available. I started using Mizoguchi films in my teaching, and the more I studied them the more I admired them. I was also inspired by critics Robin Wood and Noël Burch, who sought to explain the emotional and cinematic force of this filmmaker.

I began studying Mizoguchi’s films, traveling to Europe to see them all and make frames from prints. Eventually that work would inform my chapter on his staging in Figures Traced in Light. Although there he bested me two falls out of three, I think that discussion made some headway in analyzing his unique visual strategies. I tried to develop those ideas further in an online supplement to that chapter and in the blog entries “Secrets of the Exquisite Image” and “Sleeves.”

More skilfully and subtly than nearly anybody else, Mizoguchi arranges bodies in space to create powerful pictures. Yet his gorgeous shots aren’t just decoration. He never lets the images, elegant as they are, distract from the dramatic issues arising among the characters. The result, I argue, achieves the sort of “hypnotic power” that Mizoguchi claimed to seek.

In Mizoguchi, I suggest, a fairly dense image “becomes a story” as its elements start to mingle and separate out, letting our eye discover (with guidance) a drama as it emerges. A situation precipitates out of a rich mass of material, and the result is an accumulating tension that’s at once dramatic and pictorial. He evidently learned a lot from von Sternberg, but I think this thickening-and-release dynamic of story and style is reminiscent of Hitchcock or Lang as well.

The students were right: Mizoguchi is a master of the long take. The long take, he said, “allows me to work all the spectator’s perceptual capacities to the utmost.”

But we shouldn’t think of this technique in the sort of marathon-competition terms people apply to long takes nowadays. (The current example is Bi Gan’s Long Day’s Journey into Night.) Today’s long takes are often virtuoso traveling shots. While Mizo made wonderful use of camera movement, he knew the power of stillness. He showed that you can just clamp the camera on the tripod (or the crane) and sculpt the action in front of it.

Among Mizoguchians, there are some who find his later films stylistically compromised. Genroku Chushingura (1941-1942; below) and Loves of the Actress Sumako (1947), with their far-off figures and impeccable, “all-over” compositions, merge austerity and density in ways almost inconceivable today.

Given this radical approach, his greater reliance on closer views in the 1950s work can seem a step backward.

But Mizoguchi was a pluralistic director from his earliest days forward. As I try to show in Figures, he fitted his visual design to the needs of a scene, and even the most severe films draw on diverse techniques. Street of Shame shows his endless resourcefulness in enriching three-shots and two-shots and singles. He found choreographic possibilities at every shot scale, with small gestures and glances becoming as important as characters shifting around the set. In the last shot of the last film he made, a single darting eye commands the image and carries the drama.

Given the sustained shot, Mizoguchi fills it and drains it, re-fills it and thins it out and channels it to a climax, all with a graceful, unobtrusive choreography always driven by the emotions pulsing through the scene. I go back constantly to Philippe Demonsablon: “He emits a note so pure that the slightest variation becomes expressive.”

Mizoguchi works in melodrama. Some directors, such as Sirk, take intense situations and amp them up. But Mizoguchi, like Stahl and Preminger, is always banking the fires. His style presents hot emotions in a cool way, betting that detachment and restraint give the emotions a sort of stark purity. If more filmmakers studied his work, who knows what kind of cinema we might have? I hope you have a chance to check in on this entry.

We’re grateful as usual to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and the whole fine Criterion team, and to Erik Gunneson of the UW Department of Communication Arts.

Street of Shame is also available on a generous Criterion Eclipse DVD set. Some years back Masters of Cinema series gave us beautiful Blu-ray transfers of many Mizoguchi films. The Street of Shame edition has a fine feature-length audio commentary by Tony Rayns. Alas, the set including the film has apparently gone out of print.

Robin Wood’s influential essay on Mizoguchi is “The Ghost Princess and the Seaweed Gatherer,” in Personal Views: Explorations in Film (Gordon Fraser, 1976), 224-248. Noël Burch’s revisionist account of Japanese cinema is To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in Japanese Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979), where chapter 20 is devoted to Mizoguchi. (The book is available online here.) Roger Greenspun’s review, “‘Bailiff’ Returns,” appeared in the New York Times (17 December 1969), 61.

For more on the place of Japanese directors in film culture, you can try this entry on Kurosawa and this one on Shimizu.

Street of Shame (1956). The sign reads “Cooperative Association Members” and “Confidential Membership.” Thanks to Steve Ridgely for the translation.

Mizoguchi: Secrets of the exquisite image

Sansho the Bailiff (1954).

DB here:

First things first: Happy birthday, Mizo-san! (He was born on 16 May 1898.)

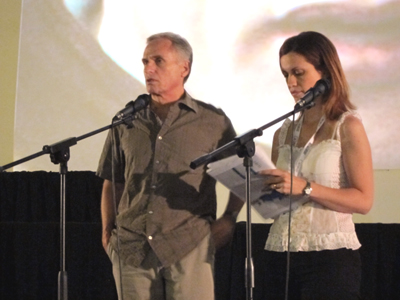

Secondary things second: This entry is based on a talk I gave a couple of weeks ago at the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, Queens, as part of its comprehensive Mizoguchi retrospective. I want to thank my friends David Schwartz and Aliza Ma for inviting me to MoMI.

A fragile and fragmentary legacy

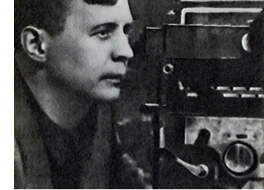

Mizoguchi, age twenty-eight, and Sakai Yoneko at Nikkatsu studio, 1926.

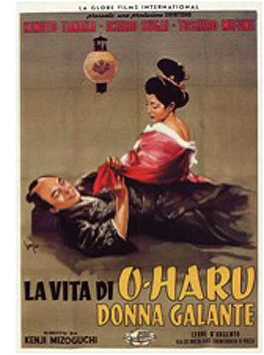

Mizoguchi Kenji’s renown in the West has flowered and faded. Like other Japanese directors, he was unknown in Europe and America before 1950. When Rashomon won the Golden Lion at Venice that year, Japanese cinema sprang onto the world’s radar. Just two years later, Mizoguchi began winning top Venice prizes with Life of Oharu (1952), Ugetsu (1953), and Sansho the Bailiff (1954). His old associate Nagata Masaichi saw export opportunities in Japanese costume pictures, especially after Gate of Hell (1953) won the Academy Award, and so Mizoguchi turned out several historical films with high-tone production values. He died in 1956, after Street of Shame (1956), a return to contemporary social commentary.

In just five years, this flare of attention and the praise of the Cahiers du cinéma critics made him second only to Kurosawa in Western recognition. During the 1960s, while Japanese critics were writing him off as outdated, international critics canonized him. Here’s Andrew Sarris in 1970.

I recently saw an obscure Mizoguchi film at New York’s Museum of Modern Art without any English subtitles, which left me up the Sea of Japan without a paddle. The program notes alerted me to the plot outline, but I was generally puzzled by the personal relationships, and the picture dragged along. . . . And then at the end the beleaguered heroine walks to a restaurant on a hillside overlooking the sea, and she orders something from a waiter in white, and the camera is high overhead, and the morning mists are bubbling all around, and the camera follows the waiter as he walks across the terrace to the restaurant and then follows him back to the heroine’s table now magically, mystically empty. It is as if death had intervened in the interval of two camera movements, to and fro, and the bubbling mists and the puzzled waiter provide the Orphic overtones of the most magical mise-en-scène since the last deathly images of F. W. Murnau’s Tabu.

Mizoguchi’s reputation was based almost completely upon his 1950s work. But as ever, film distribution shaped film tastes. Soon after the 1972 success of Tokyo Story in New York, Daniel Talbot’s New Yorker Films began circulating many major Japanese titles. Most electrifying for my generation was an abundant set of Ozu films, the arrival of which coincided with Donald Richie’s Ozu (1974). Twenty years after Mizoguchi’s emergence, Ozu began his ascent to the top of the pantheon.

Talbot’s catalogue included major Mizoguchi titles as well, notably Naniwa Elegy (1936), Sisters of Gion (1936), The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939), Genroku Chushingura (The 47 Ronin, 1941-1942), Women of the Night (1948), and My Love Has Been Burning (1949). These showed us a new Mizoguchi, one that was more pictorially daring and more sharply socially critical, than the one we had known. Soon packaged programs toured by the Japan Film Library Council revealed other films by Mizoguchi and his contemporaries. At a certain point, a Japanese colleague told me at the time, it was easier to see his nation’s prewar films in New York than in Tokyo.

Talbot’s catalogue included major Mizoguchi titles as well, notably Naniwa Elegy (1936), Sisters of Gion (1936), The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939), Genroku Chushingura (The 47 Ronin, 1941-1942), Women of the Night (1948), and My Love Has Been Burning (1949). These showed us a new Mizoguchi, one that was more pictorially daring and more sharply socially critical, than the one we had known. Soon packaged programs toured by the Japan Film Library Council revealed other films by Mizoguchi and his contemporaries. At a certain point, a Japanese colleague told me at the time, it was easier to see his nation’s prewar films in New York than in Tokyo.

A broader recognition of 1930s-1940s Japanese film was crystallized in the 1978 publication of Noël Burch’s book To the Distant Oberver: Form and Meaning in Japanese Film. Burch urged the case that Ozu, Mizoguchi, and other “mature” directors had done their most ambitious work well before the Western festivals and critics had caught up with them–that in fact the venerated postwar films were mannered and unadventurous compared to the artistically radical prewar work.

Since then, as Ozu (and Naruse, and many more) have risen to the pantheon, Mizoguchi has become quite obscure. Critics haven’t really boosted him much; his most famous film, Ugetsu, ranked 50th in the 2012 Sight & Sound poll. Nor is the range of his work easy to sample on video. In 1976, Kristin and I were obliged to go to London to see the early Ozus not in US distribution; now, everything is on DVD. But many years later I went to Brussels for a complete Mizo retrospective, and the rare titles I saw there remain nearly unknown. His festival classics and the “Talbot canon” circulate on good-quality prints and DVDs, thanks to Criterion and Janus. But other films must be hunted down in obscure foreign DVD.

Worst of all, the survival rate of Mizoguchi’s films is appalling (although not exceptional for Japan). He made 43 films between 1923 and 1929; of these, only one survives complete. For the rest of his career he made or contributed to 42 features, of which we have 30. We lack over half his output. The physical quality of what we have varies a great deal, from gorgeous (Genroku Chushingura) to appalling (The Straits of Love and Hate, 1937, blown up from a scratched and contrasty 16mm copy). In fact, copies seem to have deteriorated. Prints I saw in the 1970s of Oyuki the Virgin (1935) were in decent shape, but many copies circulating now seem to be bad dupes of those prints, now much battered. There seems to be no systematic effort to restore what we have.

Tears are easy; tragedy is hard

I can’t deny that Mizoguchi’s fluctuating reputation is due to more than availability. He is easier to admire, even to worship, than to love. His films, though visually sumptuous, can be somber and bleak. Often unremitting tales of suffering, they lack humor (though not irony). Ozu’s mix of poignancy and comedy is much easier to enjoy than Mizoguchi’s forbidding, near-tragic despair. Ozu is also a more rigorous stylist; his signature is in every frame. While Mizoguchi was no less distinctive, he was more pluralistic in his technique.

Another obstacle: despite working with melodramatic material, Mizoguchi cools it down, sometimes to the point of remoteness. For many of his films, the prototype was Japan’s shinpa drama, an early twentieth-century theatrical tradition that blended kabuki themes and situations (e.g., the conflict of love and duty) with Western-style dramaturgy. Shinpa plays tended to concentrate on the sufferings of women in a male-dominated society. Shinpa women are victimized, exploited, and condemned; when they sacrifice themselves for men, too often the men attack them, betray them, or dump them. Mizoguchi worked many variations on these plot elements. When the American Occupation demanded more liberal films from the industry, he simply let the oppressed woman win some victory in the end.

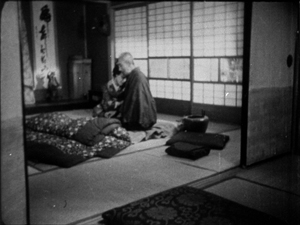

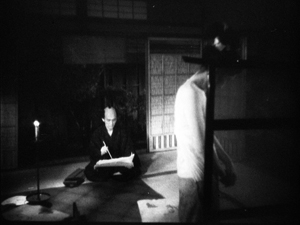

Whether the woman wins or loses, Mizoguchi refuses to beg for tears. Some directors, notably Sirk, amp up melodrama; others, like Preminger, bank the fires. Mizoguchi seems to try to extract the situation’s emotional essence, a purified anguish, that goes beyond sympathy and pity for the characters. In The Poppy (1935), here’s how he renders the moment at which a father and daughter learn that the daughter’s suitor has abandoned her. The core dramatic action is the daughter moving from the foreground to console her father, at which point they embrace.

Some climax! No close-ups, no fast cutting, no camera movement; people withdraw from us and leave us on the outside. All of which suggests that one dimension of Mizoguchi’s artistry consists of exploring how human emotions, notably the unhappier ones, can be expressed in vivid, sometimes surprisingly “cold” pictures.

Pictures tell the story

Everybody grants that Mizoguchi makes magnificent images. He has gone down in history as a pictorialist. But his pictorialism is of a peculiar kind. We tend to think of pictorialist filmmakers as, for instance, masters of landscape, like Ford in My Darling Clementine; or exponents of abstract patterning, like von Sternberg in Shanghai Express; or buccaneers of aggressive depth, like Welles in Citizen Kane.

On each of these possibilities Mizoguchi can match the masters. Here’s a landscape from Portrait of Madame Yuki (1950; this is the scene that made Sarris swoon), a geometrical shot from Hometown (1930), and a bold depth composition from Naniwa Elegy four years before Kane.

It’s not surprising that Mizoguchi relies on the image; in his youth he studied painting (interestingly, Western-style painting at that). But he is, I think, a more fervent pictorialist than his peers.

Most movie scenes consist of a story situation mapped onto the space; the style follows, emphasizes, or shapes the story’s presentation. Suppose, Mizoguchi seems to ask, that we start with an image and ask it to become a drama. That’s in a sense what seems to happen with the Poppy example above: a striking picture develops into a story through a suite of compositional changes. Or consider this, from Sansho the Bailiff. A scene starts with a bundle of brush in a village street. Gradually it becomes the site of action: two children peep out, one by one.

Our view isn’t impeded only by the brush. A man bursts eagerly into the frame, blocking the boy and girl, followed by another man. The camera tracks a bit around the foreground post. As the scene goes on passersby will intrude into the frame.

You can’t, I think, imagine many more ways to suppress our views of the kids. We strain to see past all these obstructions, and when the view finally clears and the children are visible and come forward briefly, they turn from us…and more people pass in the foreground.

This is actually an important moment in Sansho the Bailiff: The children, kidnapped from their mother, are about to become slaves. It could be rendered with all the stops out, as a scene of brutality or high tension, but instead Mizoguchi let the dialogue (after some delay) explain what’s happening. At first you might think that Zushio and Anju have escaped from their captors and are in hiding; the unfolding image initially permits that possibility. Eventually, though, the shot, expressing the children’s fear and shame as they shrink from not only the men but the camera, holds us in its own right.

Instead of an image that is a vehicle for the story, the story is gradually born out of the changing image. To some degree, this happens in many films, but not with the persistence and rigor we find in Mizogcuhi. He talked of wanting to hypnotize the viewer, and this is done, I think, as much by the minute changes in the pictures as by the dynamics of the drama.

This version of pictorialism employs several strategies. I’ll mention just three.

Now you see it, sort of

Kiyonaga Toru, Interior of a Bathhouse (1780s).

Filmmakers must study the film image and its potential for expression. This is our primary responsibility.

Mizoguchi Kenji

Traditional Japanese cinema is itself heavily pictorial, from the zigzag excitement of the 1920s swordplay films to the dynamic modernity of the city dramas and the monumental gravity of historical dramas. Directors, I’ve argued in various places, cultivated a “decorative” approach to technique. Composition, camerawork, cutting, and other tactics often created flashier compositions than we find in other national traditions. As early as 1922, Ikeda Yoshinobu was creating arabesques with a bedstead, framing the faces of grieving family members (Cuckoo).

The gridded zones of the Japanese house seems to have invited filmmakers to explore a sort of Advent-calendar style, with bodies framed in different apertures (The Abe Clan, 1938). The same idea could be applied to a bar’s Art Deco wall divider (First Steps Ashore, 1932).

I’ve also argued that this love of pocketed compositions may be an effort to echo similar impulses in Japanese graphic art. The Kinoyaga woodblock print above, with its partial views of women bathing and the little windows through which we see the male attendant watching, is a beautiful example. Perhaps filmmakers adapted this eye-beguiling tactic as a way of giving cinema some cultural credentials (if not a national identity).

Most directors don’t sustain such flashy compositions. The shots function mostly as long-shots or establishing shots, or as in the Cuckoo example, as a series of brief extracts from the larger scene. Mizoguchi drew upon this decorative tradition but let it be sustained through figures moving into and out of the apertures within the frame. He creates a game of vision, a sort of fluctuating pictorial vividness that conceals or reveals or teases us with information.

One of the most vivid examples comes in this famous scene from Sansho the Bailiff. Tamaki’s leg tendons are cut, and the other enslaved women are forced to witness it. As the struggling Tamaki is peeled away from the wall and the slavemaster walks to her offscreen, the other women become visible and an older master comes slightly forward in the central square Tamaki had occupied.

As she screams, the grid isolates each woman’s fearful turning away. As with the earlier Sansho scene, dialogue comes to “button up” the unfolding of the image: The old man tells the cringing women that all runaways will punished this way.

The impact of the act is amplified not by, say, cutting to different women’s reactions, but by letting us see them all, simultaneously, in a choreography of terror.

Mizoguchi finds an abundant variety of ways to play his game of vision. Not only are figures and faces secreted in various pigeonholes of the frame, but he can tease us with some that are merely shadows or partial figures (The Poppy; Tokyo March, 1929). Sometimes the key element, such as a character’s reaction, is obscured by a semi-transparent surface, as when the embarrassed model is caught in a corner of a screen in Utamaro and His Five Women (1946).

What other directors treated as piquant flourishes, imaginative ways to arouse our visual interest before moving in to closer views, Mizoguchi saw as a way to activate any cranny of the image and invest it with expression. But for that process to unfold, he needed time.

Intensify and prolong

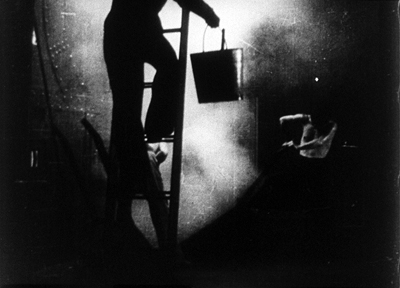

From the brief surviving fragment of Tojin Okichi (1930).

During the course of filming a scene, if an increased psychological sympathy begins to develop, I cannot cut into this without regret. I try rather to intensify and prolong the scene as long as possible.

Mizoguchi Kenji

Mizoguchi is famous as an exponent of long-take shooting. His earliest surviving film, Song of Home (1925) displays the Hollywood-style editing that most Japanese filmmakers mastered at the period. At some point–he says it was while shooting Tojin Okichi (Okichi, Mistress of a Foreigner)–he began using a method he called “one scene, one cut.” (Here “cut” apparently refers not to a shot change but to a single take, like a “cut” of meat. Hollywood filmmakers talked the same way sometimes.) That would suggest that he took every scene in a single shot, but actually he didn’t. Most of his scenes are built out of several shots, and throughout his career he would have recourse to standard analytical and shot/reverse-shot cutting for many sequences. He wasn’t as strict about the plan-sequence as, say, the Miklós Jancsó of the 1960s and 1970s was.

Still, he definitely used longer takes than most filmmakers of his day. The shots in most of his post-1935 films average between twenty-five and forty seconds in length, which means that some shots run minutes. Many of his long takes are made from static camera positions, as in the above examples. But he didn’t shrink from camera movements, either tracking shots or crane shots. Kristin and I discuss an example from Sisters of Gion in Film Art, and in his later films he enjoyed establishing a setting with a high-angle crane shot before moving in to details. He also enjoyed riding the crane and directed from it even if the shot was static.

Fixed frame or moving shot, Mizoguchi’s long takes can extract an arc of pictorial-dramatic intensity. That arc can have a clear-cut ABA pattern. In My Love Has Been Burning, the liberal feminist Eiko finds her weak lover Hayase drunk and despondent. He’s no longer the idealist she thought he was, but he defends himself as changing with the times.

Hayase says he’s got some money now and they can marry. When she doesn’t warm to the idea, he attacks her, and suddenly her face gets enlarged, upside down, when he slams her to the floor. This is the first high point of the scene.

They struggle out of frame, but Mizoguchi doesn’t follow them.

Immediately there’s a second assault on our vision: a screen abruptly crashes into the foreground.

After it settles into place, Eiko flees back into the frame, pausing by the doorway. She leaves, and Hayase totters to the same spot looking after her.

The shot has built up to one spike, the image of Eiko on her back, her face close to us, and then to a second, with the collapsing screen. At the end, the site of action returns to the beginning: a figure near the doorway, something else (Hayase, the screen) in the foreground. But in the course of this ABA pattern, the game of vision has concealed as much as it has revealed.

Throughout his career Mizoguchi experimented with the patterning of his long takes, often building them around advances to and away from the foreground, as in these examples. This tactic can be seen in a pure state in the most intense scene of the Occupation feminist film Victory of Women (1946). Here the characters rush the camera and shrink from it as the emotional pitch rises.

Tomo’s husband has just died, and she has already told her friend the lawyer Hiroko that she has no more milk for her baby. Tomo calls on Hiroko, who invites her to come in. The camera obediently tracks back as she enters and sits.

Hiroko, at first oblivious to the distraught Tomo, begins to question her. At first Tomo says that nothing has happened to her baby, and she slides away from Hiroko. She tells her that her husband died the day that they had met in the street. She edges closer to the camera.

Sobbing, she tells Hiroko that the baby is dead; he died sucking her breast. She falls out of the frame and as the camera pulls back Hiroko bends to comfort her. But she also asks Tomo to tell her exactly what happened.

Tomo confesses that staring at her crying baby, she hugged it so close that she may have killed it. As she rises, she cries, “My baby!” And she turns and staggers, like Ayako in Naniwa Elegy, to the most distant point of the set–as if hoping to escape both Hiroko and the camera.

Track in as Hiroko goes back to her, at the spot at which the shot’s action started. Once more the two women advance to the camera, with Hiroko nearly dragging Tomo back to the center. But when Hiroko suggests she go to the police, Tomo slides quickly away from her, back to us, and the camera abruptly pulls back to accommodate her. As when the paper wall crashes into the frame in My Love Has Been Burning, a spike in the drama is accompanied by a second burst into the foreground.

Hiroko rushes to embrace Tomo, assuring her that “You must not run from life, but face it!” Mizoguchi’s staging favors the doubt and fear on the face of Tomo, not the somewhat complacent Hiroko.

As Hiroko hurries off to dress for going out, Mizoguchi’s camera lingers on Tomo, not only pitiable but justifiably worried that she is condemned. As she bends and glances to and fro, Mizoguchi ends the seven-minute scene on an image of a woman with nowhere to turn. This is a terrifying final image: Is this what Hiroko meant by “facing life”?

Some of Mizoguchi’s earlier works go further still. Instead of a coming-and-going pattern, in which the characters confront the camera and then retreat, we get a going-and-going one. The most famous, about which I’ve written probably more than I should, comes in Naniwa Elegy, when Ayako, telling her boyfriend of her sexual infidelity, retreats from him, and from us.

A Western director–Wyler, say, as in The Little Foxes, or Huston–would have put the camera at exactly the opposite point, in the corner of the wall, so that Ayako would advance toward us and Nishimura’s reaction would be constantly visible in the background. It’s as if Mizoguchi anticipated such full-disclosure framing (before these men had even made their films!) and dismissed it as too easy. By suppressing characters’ expressions, he throws our attention onto Ayako’s voice and her posture, while also sustaining some suspense about how Nishimura will respond to her revelations.

Mizoguchi finds a huge variety of ways of turning images into drama, and he has left us a rich repertory of staging strategies–if we only look. Young filmmakers, are you looking?

Filigree

Tanaka Kinuyo and Mizoguchi Kenji in Venice, early 1950s.

[The long take] allows me to work all the spectator’s perceptual capacities to the utmost.

Mizoguchi Kenji

Once Mizoguchi enhances the decorative frame with surfaces and holes bristling with possibilities, and once he sustains it in time through the long take, he can build his scenes out of slight changes in the image–changes that add nuance and expressive depth to the drama. We’ve seen this already in several passages, but I want now to stress how this sharpens our attention and engagement. The restraint of Mizoguchi’s handling (restraint within sumptuousness, I should say) trains us to watch for the tiniest shift in pictorial emphasis. This is the third strategy I want to mention.

In Lady of Musashino (1951), minor changes around the deathbed drive our eye to the profile of the dying Michiko.

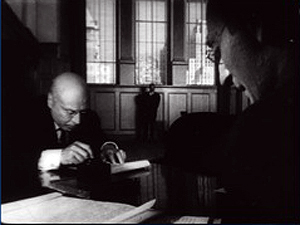

Likewise, when Oishi in Genroku Chushingura reads the master’s poem, sent to his vassals after his suicide, he lowers the paper just a little at the climax, and the gesture is echoed in the men’s slumping forward even more. (This is a movie largely made of just-noticeable differences.)

The just-noticeable differences can be triggered by tiny changes in the avenues of our vision. In Street of Shame, the brothel owner, turned from us in the middle ground, first reveals Mickey and the delivery boy down the left corridor. When he shifts his head, Mizoguchi closes off that view and allows faces and bodies of the prostitutes to fill up the corridor on the right.

Bolder movements can yield even briefer glimpses. When Oharu reads the message from her dead lover, Mizoguchi gives us a “decoy” shot: Her mother stands guard on the left and in the distance we see the door through which the father is expected to come. But the scene’s real action is taking place behind the hanging kimono, where Oharu reacts painfully to the letter. Since we can’t see her, only her wavering voice and the trembling of the kimono convey her emotion. Suddenly she starts to thrash around, her mother leaps toward her, and a tussle ensues. The kimono is pulled down in a heap.

What’s all the fuss? What is Oharu doing? The answer is given to us in an almost subliminal detail, the knife that flashes through the lower right corner of the shot in only two frames on the 35mm print. Oharu races out of the shot, bent on suicide.

So the nuances that spring up may be protracted or simply glimpsed, but either way they become the product of the image giving birth, through its transformations, to the drama. The strategy is just as applicable to closer views as to long shots. In one scene of Woman of Rumor (1954), the keeper of an elegant brothel notices a young man getting cozy with her daughter. The tension is exacerbated by the fact that she hopes to nab Dr. Hatoba herself. As the two talk, Mizoguchi buries Hatsuko in the rear of the scene, her presence signaled by a shadow and her kimono sleeve poking out from a screen.

Mizoguchi cuts directly in and provides a medium-shot of Hatsuko peeking. This might seem safe and conventional, especially in the light of daring choices like those made in Naniwa Elegy. But Mizoguchi now wants to trigger the game of vision around the woman’s face and the edge of the screen. As she listens, he teases us with a little suite of changing expressions and minute gradations of partial blockage–a sort of pictorial vibrato.

As Hatsuko edges out to approach the couple, Mizoguchi switches our attention to small, nervous hand gestures.

Once installed behind the couple, Hatsuko starts the whole process again, from eye-catching sleeves to peekaboo eavesdropping.

Mizoguchi was a fairly pluralistic filmmaker, so the strategies I’ve itemized don’t exhaust everything we encounter in his movies. Sometimes he builds scenes in a fairly orthodox way, with traditional framing and cutting. But taken as a whole, his films offer a magnificent repertory of ways in which the image can, under pressure, deepen and enrich a dramatic situation. Unlike most of today’s filmmakers, he cares about rigor, nuance, and austerity–while at the same time working with scenes of intense emotion. Admire him, worship him, love him, or just respect him: film culture can’t live fully without him.

Thanks, over forty years of viewing, to the Japan Society of New York, the Kawakita Memorial Film Institute (formerly the Japan Film Library Council), Dan Talbot and José Lopez of New Yorker Films, and the Brussels Cinematek, especially Gabrielle Claes.

The MoMI series runs until 8 June. It begins on 16 May at the Harvard Film Archive and on 19 June at Pacific Film Archive. For Fandor’s Keyframe daily, David Hudson has a varied roundup of response to MoMI’s series.

Both Criterion and Masters of Cinema offer many Mizoguchi films on DVD, some on Blu-ray. See also Criterion’s Hulu Plus offerings. Digital Meme sells DVDs of some early Mizoguchis, with benshi accompaniment; the exasperatingly brief fragment of Tojin Okichi is on volume 2..

My quotation from Andrew Sarris comes from “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1970,” in The Primal Screen (1973), 60-61.

Good clichés will never die as long as journalists need to crank out copy. The MoMI retrospective has revived the Kurosawa-Mizoguchi tug-of-war, this time among New York critics (here and here). Such sideswipe critiques and hosannas can’t really be backed up within the space limits of popular publishing. Moreover, I think that such quick assertions of taste block close consideration of the work. Once you’ve dismissed a filmmaker, you’re unlikely to probe further, and your readers will probably be even less curious. I defected years ago from the Kurosawa-Mizoguchi skirmishes.

The fact that every decade or so Mizoguchi is “rediscovered” through a retrospective indicates his elusive reputation. Among English-language scholars, the 1980s was the big period. Dudley Andrew wrote a still indispensable reference book on Mizoguchi in 1981, and Keiko McDonald offered a penetrating critical survey in 1984. Both volumes, now rare and costly, deserve to be made available in digital editions. Robert Cohen’s two-volume dissertation “Textual Poetics in the Films of Kenji Mizoguchi” (UCLA, 1983) was also significant. Since then, incredibly, we have had only one more overview in English, Mark Le Fanu’s Mizoguchi and Japan, along with an in-depth analysis of some 1930s films, Don Kirihara’s award-winning Patterns of Time. Sato Tadao’s monograph was published in Japanese in 1982, but it’s only recently been available in (a somewhat problematic) English translation (as Kenji Mizoguchi and the Art of Japanese Cinema). Two of my stills are drawn from this book. The French have been more consistently productive, with several studies over the years. A thorough account in Spanish is by the prolific Antonio Santos.

For some background on Western rankings of Mizoguchi, Kurosawa, and Ozu, see this interview with the late Hiroko Govaers. Hiroko was instrumental in bringing many classic Japanese films to Europe and the U.S.

Some of the material in today’s entry comes from Chapter 3, “Mizoguchi, or Modulation,” of my Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. That offers a much fuller account of what I think Mizoguchi is up to, although today’s blog offers some points and examples not in the chapter. Offshoots of the book’s argument can be found in this online update, and in this blog entry, which compares Mizoguchi with his sort-of-rival Wyler. My oldest piece on the director, “Mizoguchi and the Evolution of Film Language,” in Stephen Heath and Patricia Mellencamp, eds., Cinema and Language (1983), 107–117, contrasts his work with Western practitioners of deep-space staging. Background on the “decorative” impulses in traditional Japanese cinema can be found in Essays 12 and 13 in my Poetics of Cinema, and in early portions of Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema.

P. S. 29 June: Thanks to Jeff Fort for correction of a title in the original blog post!

Sansho the Bailiff.

Solo in Bologna

Kristin here:

Two days before David and I were to set out for Bologna and its annual Il Cinema Ritrovato festival, back pain struck him. He decided not to go, and so our coverage this year will be briefer. I struggled to see as much as possible, but if anything, the program was even more packed than last year.

The auteurs

The main threads included four directors who are of historical interest. Raoul Walsh was the main attraction, with emphasis less on familiar classics like Roaring Twenties and White Heat and more on hard-to-see items like Me and My Gal and other early 1930s films. Lois Weber, the first important female director in American cinema, was represented with as complete a retrospective as possible, including fragments from features not otherwise extant. Jean Grémillon, one of the less famous French prestige directors during the 1930s and 1940s, was extensively represented. And there was Ivan Pyriev (or Pyr’ev, going by the program notes’ spelling), most famous as one of the main proponents of the “kholkoz [collective farm] musicals” of the last 1930s and 1940s.

I had seen a couple of Pyriev’s films and decided to see as many as possible of the series on offer, programmed by our long-time front-row neighbor in the Cineteca venues, Olaf Möller. Pyriev is an interesting case historically. He came to filmmaking just as the Soviet Montage movement of the 1920s was coming under official pressure for its formal complexity.

I had seen a couple of Pyriev’s films and decided to see as many as possible of the series on offer, programmed by our long-time front-row neighbor in the Cineteca venues, Olaf Möller. Pyriev is an interesting case historically. He came to filmmaking just as the Soviet Montage movement of the 1920s was coming under official pressure for its formal complexity.

The Civil Servant (or The State Functionary, 1931) was a full-blown, skillful leap into Montage, with an prologue of trains coming into Moscow, shot with canted framings, low angles, and quick cuts with trains moving left, then right. The rest is a satire on bureaucracy within the national railroad system—ostensibly set during the Civil War but clearly a contemporary story. It’s broad in its humor, and it has the obvious typage in the choice of actors, the wide-angle lenses that the Montage filmmakers explored in the late 1920s, and other scenes of quick cutting with jarring reversals of directions.

Official dislike of The Civil Servant kept Pyriev from directing again for three years. Turning his back on Montage, he went to the other extreme, helping to develop the kholkoz (collective-farm) musical and making some of its liveliest, most entertaining, and most enthusiastic examples of that genre. His Traktoristi of 1939 was not shown during the festival, but one that I hadn’t seen, Swineherd and Shepherd (1941), is fully its equal. From the moment the film begins, with the camera madly tracking backward through a birch forest as the heroine runs full tilt after it, singing joyously to the masses of pigs that emerge from corrals and gallop along with her, the spectator realizes that this film will be exactly what one wants and expects from Pyriev.

A later entry in the genre, The Cossacks of the Kuban (1950), was even better, and I can see why it is Olaf’s favorite. The opening vistas of immense wheat fields, gradually moving to scenes with tiny figures and finally to ranks of harvesting machines and trucks achieves a genuine grandeur, aided considerably by the fact that by this point Pyriev is working in color. The story goes beyond the simple stock figures of some of the earlier musicals, with a stubborn Cossack who heads one collective farm nearly missing his chance at romance with a widow who heads a rival farm.

Overall, I like these films a little better than those of his more famous colleague in the creation of buoyant musicals, Grigori Alexandrov. Yet it has to be mentioned that there is a certain underlying unease in being entertained by films that created hugely idealized images of life on collective farms. In reality many peasants were starving, and few were working with such cheerful enthusiasm to increase production for the sake of the great Soviet state. One might rationalize this dissonance by thinking that Pyriev was perhaps making fun of his subject with over-the-top dialogue and musical numbers. Yet surely to many audiences at the time, this was escapist entertainment, and urban audiences may have had little sense of the blatant inaccuracy of the portrayals of the countryside.

Two more straightforward dramas, The Party Card (1936, below) and The District Secretary (1942), a war story, were more conventional Socialist Realist works, skillfully done but lacking the appeal of Pyriev’s lighter films.

It was sad to see the one post-Stalinist film from Pyriev’s late career, his adaptation of The Idiot (1958). A sumptuous production, again in color, it consisted almost entirely of overblown confrontations among characters. The actors shout all their lines at each other with almost no variation in the dramatic tone, with everything underlined by an amazingly intrusive musical score.

I saw only a few of the Walsh films, since they frequently conflicted with the Pyrievs and Grémillons and just about everything else on offer. To me, the director was a bit oversold. Peter von Bagh’s introduction to the catalog says, “Unjustly, Raoul Walsh, although blessed with so much cinephilic worship, is usually placed a few notches below his more revered colleagues Ford and Hawks. Now he will have a chance to be upgraded, in our continuing series featuring extensive screenings from Walsh’s silent period through his very rare early sound films.” Perhaps Walsh will go up a notch in people’s estimations—the screenings of his films were certainly very popular—but not, I think, the few notches it would take to place him alongside these two other masters. I enjoyed Me and My Gal, a rare 1932 comedy in which Spencer Tracy and a very young Joan Bennett adeptly exchange snappy patter, yet it occurred to me more than once during the screening that Twentieth Century (1934) is a much funnier film.

The Big Trail, shone in its original wide-screen Grandeur format on the giant Arlecchino screen, was better than I expected. Walsh was given enormous resources to tell the story of a large wagon train making its way to Oregon from the Mississippi. He showed off the crowds of wagons, cattle, and people by the simple expedient of raising the camera height so that most of the screen’s height became a tapestry of people stretching into the distance, all going about their business while the main dramatic action in the foreground occurred. This often involved a very young John Wayne, whose occasional awkward delivery of lines managed somehow to fit with his character.

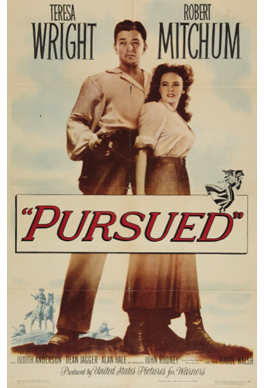

Pursued (1947), shown in an excellent 35mm print, was one of the few certified Walsh masterpieces in the series. Of course I enjoyed it. It struck me how crucial the casting of Teresa Wright as heroine Thor Callum was. So often Westerns have minor actresses as the love interest, women that one can seldom recall seeing in any other film—starlets rather than stars. Thor’s dramatic arc is pretty extreme and somewhat implausible, but Wright manages to make the character convincing and sympathetic, as well as an effective counterpoint to Robert Mitchum’s stolid Jeb Rand. James Wong Howe’s cinematography was also a big plus.

Pursued (1947), shown in an excellent 35mm print, was one of the few certified Walsh masterpieces in the series. Of course I enjoyed it. It struck me how crucial the casting of Teresa Wright as heroine Thor Callum was. So often Westerns have minor actresses as the love interest, women that one can seldom recall seeing in any other film—starlets rather than stars. Thor’s dramatic arc is pretty extreme and somewhat implausible, but Wright manages to make the character convincing and sympathetic, as well as an effective counterpoint to Robert Mitchum’s stolid Jeb Rand. James Wong Howe’s cinematography was also a big plus.

Few of Walsh’s pre-1920s films survive, but those few were shown. I skipped the wonderful Regeneration, having seen it multiple times, but I caught The Mystery of the Hindu Image, notable mainly for Walsh’s own performance as the detective, and Pillars of Society, a somewhat stodgy adaptation of the Ibsen play.

I can’t say much about the Weber films, since they were consistently in conflict with screenings of films by the other main auteurs. I regret having skipped one Pyriev film, Six O’clock in the Evening after the War (1944) to see Shoes (1916), which had been touted as one of the director’s best. It proved a considerable disappointment, stuffed with expository intertitles that often simply described what we could already see from the action in the images. This may have been because Weber’s “discovery,” Mary McLaren, was so inexpressive. She almost constantly wore the same expression of resigned sadness at her family’s grinding poverty, varying it occasionally with a look of annoyance at her father’s shiftless behavior. I tried to steer people to The Blot, which is probably Weber’s masterpiece among the surviving films.

It was fairly easy to see most of the Grémillon titles, because a number of them were repeated in the course of the week. I enjoyed Maldone, which I had seen once long ago. Its story involves a runaway heir to a large estate who has run away as a young man and now, in late middle age, works on a canal barge. Infatuated with a beautiful gypsy and spurned by her, he returns to claim his inheritance, only to be disgusted by gentrified life. Like Pyriev, Grémillon came late to one of the commercial avant-garde movements of the 1920s, French Impressionism. He uses the subjective camera effects and the rhythmic editing in a straightforward way, with little of the flashiness of a L’Herbier or a Gance. Maldone and his subsequent film, Gardiens des phare (1929), shown at the festival in a tinted Japanese print, remind me of perhaps the best filmmaker of the Impressionist movement, Jean Epstein.

This legacy might logically have led Grémillon into the Poetic Realism of France in the 1930s. Unfortunately his first sound film, La petite Lise (1930), which might be said to fit into that tradition, was not shown. After seeing several of the films on offer this year, I still think it may be his masterpiece. (We talk about it briefly in the section on early sound cinema in Film History: An Introduction.) Though some might argue that he has at least one foot in that tradition, his work is perhaps closer to what the Cahiers du cinéma critics later dubbed the Cinema of Quality.

As for the others I caught: L’étrange Monsieur Victor (1938, dominated by Raimu as a successful merchant who is not all he seems), Remorques(1939-41, perhaps Grémillon’s best-known film, re-teaming the favorite French couple of the 1930s, Jean Gabin and Michele Morgan), and Pattes blanches (literally, “White putties,” 1948). I enjoyed them all, and yet there was no sense of discovering an overlooked genius. Best of the sound features for me was Pattes blanches, which tempered Grémillon’s taste for melodrama with a hint of surrealism. The obsessive young wastrel Maurice (played by a very young Michel Bouquet), the gamine hunchback maid who falls in love with the reclusive and menacing local nobleman, and the nobleman himself, invariably bizarrely clad in his white puttees, help give the film a fascination that the others, for me at least, lack.

The themes

There were other threads oriented by genre or topic or period. These I sampled when it was possible to insert them into my schedule. One of these was “After the Crash: Cinema and the 1929 Crisis,” which included an intriguing potpourri of documentaries and fiction films from several countries and political stances, from Borzage’s A Man’s Castle to two short films by Communist-leaning Slatan Dudow, director of Kuhle Wampe. Because of my interest in international cinema styles of the late 1920s and early 1930s, I went to Pál Fejös’s Sonnenstrahl (“Sun Rays,” 1933) was shown in the festival’s first time slot, 2:30 on Saturday afternoon. It thus competed with the first showing of the Grandeur version of The Big Trail and the first program of the “Cento anni fa” set of 96 films from 1912, but such is Bologna’s lavish scheduling.

Fejös, a Hungarian, made films in Hollywood, France, Denmark, Sweden, and a number of other countries. Sonnenstrahl, with its romance between German actor Gustav Fröhlich and French leading lady Annabella, is basically a reworking of the director’s best-known film, Lonesome (1928), with touches of 7th Heaven (Borzage, 1927), redone for the Depression era. It’s a pleasant enough piece, though not up to Fejös’s best work of the 1920s. Again, the program claims to too much for the filmmaker by saying that some historians consider him “as one of the cinema’s great poets, along with Murnau and Borzage.”

The Depression program also included a surprisingly good early sound film by Julien Duvivier, David Golder (1931, above). It’s the story of a wealthy businessman, played by Harry Baur, who discovers that his wife and daughter love him only for his money. How he could have lived this long with them without realizing this is perhaps a weakness in the plot, but from the start Duvivier showed a remarkable assurance in framing, cutting, and camera movement that was continually in evidence. Sets by the great Lazare Meerson also enhanced the style.

Baur also starred as Jean Valjean in Raymond Bernard’s 1934 three-part Les Misérables. I skipped the screenings, since the film is available in a Criterion boxed set (along with Bernard’s remarkable 1932 anti-war film Wooden Crosses). The Bernard film was part of the “Ritrovati and Restaurati” thread. The presence of Baur in both David Golder and Les Misérables led to the Depression and Ritorvati threads to weave together to produce a third: “Homage to Harry Baur.”

The only other entry in this brief thematic collection was Duvivier’s La tête d’un homme (1933), the third film based on a novel by Georges Simenon. Baur stars as Commissioner Maigret, and Valery Inkijinoff (known largely as the hero of Pudovkin’s Storm over Asia/The Heir of Ghengis Khan, though he acted in numerous other films as well) plays the doomed, obsessive villain, Radek. The film is not as accomplished as David Golder, but it’s an entertaining little thriller with some novel twists. Early in the film the murder is revealed, and we know from the start the Radek committed it. The duel between him and Maigret becomes the focus of the action. Moreover, the very first scene introduces a thoroughly unlikeable fellow who initially seems to be the villain, a womanizing cad who lives by gambling and other unsavory activities, yet who himself eventually comes to be tormented and threatened by Radek.

Another intriguing thread was “Japan Speaks Out! The First Talkies from the Land of the Rising Sun.” Ordinarily I would have tried to see most of these, but again they conflicted with the auteur threads I was trying to follow. I did make it a point to see Mizoguchi’s first sound film, Hometown (1930, above), since it’s one of the hardest to see. A part talkie built around a famous Japanese tenor and opera singer, it was more an historical curiosity than a satisfying film. I reluctantly skipped Heinosuke Gosho’s delightful Madame and Wife (aka The Neighbor’s Wife and Mine), the first really successful Japanese talkie, having seen it a number of times. On David’s and Tony Raynes’ advice, I caught Yasujiro Shimazu’s First Steps Ashore, a romantic tale inspired by Von Sternberg’s The Docks of New York. It didn’t quite match the original (as what could?) but was an entertaining tale well acted by the two leads. The first frame below reflects something of the style of Docks of New York, but the second, more typical of the film, is pure Shochiku.

The organizers of Il Cinema Ritrovato have declared that they will continue to show films on 35mm as long as possible. Most of the screenings that I attended were indeed on film. There’s no doubt that the move to digital restoration became dramatically more apparent this year. Nearly all of the 10 pm screenings on the Piazza Maggiore were digital copies, including Lawrence of Arabia, Lola, La grande illusion, and Prix de beauté. David and I don’t usually go to these screenings, since we invariably want to see films in the 9 or 9:30 AM time slots and don’t want to fall asleep during them. But I did catch two digital restorations shown earlier in the evening in the Arlecchino.

The first, Voyage to Italy, was flawless and sharp—perhaps a little too sharp. I liked the film much better than the first time I saw it, maybe because I understood better the claims that are made for it as a forerunner of the art cinema of the 1960s, with the aimless, confused couple presaging the characters of directors like Antonioni.

Perhaps the high point of my week, though, was an entry in an ongoing thread at the festival, “Searching for Colour in Films.” There were many films in this category, which was broken down into the silent and sound eras. Bonjour Tristesse may well be my favorite Otto Preminger film. Our old friend Grover Crisp (above, with interpreter) returned to Bologna to introduce it in a digital restoration, but one which, he assured us, retained the grain of the original film. It was certainly a beautiful copy and looked great on the Arlecchino screen. (The frames at the top and bottom of this entry were taken from a 35mm copy, not a DVD or the new restoration.)

Il Cinema Ritrovato grows more popular each year. A number of our friends from other festivals and alumni of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s film studies program attended for the first time and vowed to return. Perhaps a sign that the event is gaining real prominence internationally was the fact that Indiewire columnist Meredith Brody also made her first visit. She conveys the impressions of a newbie in a series of posts: Day 1, Day 2, Day 3, Day 4, and Day 5. For many images of the festival guests and screenings, see the official website.

David analyzes one Hitchcock-like scene in The Party Card in his On the History of Film Style.

July 9: Thanks to Ivo Blom for correcting my spelling of Harry Baur’s name.

Good and good for you

Late Autumn (Ozu Yasujiro, 1960).

DB here:

Manohla Dargis of the New York Times has just written a piece that refers to some ideas that have appeared on this site. If you see the article online, you’ll find the links to appropriate entries, but if you’ve come here after reading the paper edition of the Times, you can find the Tim Smith essay she cites here. It is a remarkable piece of work, and it’s gratifying that Dargis has called attention to it. (Tim’s video experiments have received many hundreds of thousands of downloads already.) My table-setting entry, on task-driven looking, is here.

The backstory is simple. On this site in 2008, I took a slow, unemphatic scene from There Will Be Blood as an example of how a director can subtly guide our attention without cutting, camera movement, or auditory underlining. My analysis was guided by recognition of my own responses and some knowledge of traditions of cinematic staging. Tim, in his turn, used the tools of modern perceptual research to show that we can gain firmer knowledge of directorial craft. By tracking viewers’ eye-scanning, Tim demonstrates vividly that filmmakers can shape our experience of the action on a second-by-second basis. This not only helps us understand how we grasp images. It shows that humanistic inquiry and psychological research can collaborate.

Why so unserious?

Late Spring (Ozu Yasujiro, 1949).

Those who navigate Internet eddies and flows know that dozens of responses have swirled around Dan Kois’ “Eating Your Cultural Vegetables.” Kois wants to like long, slow movies, but after trying for years, he has found that he just can’t enjoy many of them. He can mimic, even anticipate, the judgments of those who do, but in his heart he finds most of the celebrated films boring. He’s now decided to give in to his impulse and declare that he needn’t pretend to enjoy Tarkovsky or Hou Hsiao-hsien:

As I get older, I find I’m suffering from a kind of culture fatigue and have less interest in eating my cultural vegetables, no matter how good they may be for me.

As one man’s confession of guilt and fatigue, this is doubtless sincere, although its sideswiping putdowns of viewers who praise such movies suggest more calculation than humility. Still, this cry from the heart has broader implications, as many Net writers have discussed. Kois’ complaint elicited not one but two responses from the New York Times film critics A. O. Scott and Manohla Dargis. For one thing, Kois’ essay seems to offer aid and comfort to people who are afraid to try something different. Indeed, it lets them feel superior to the phonies who claim to like such films. Moreover, Kois justifies the most superficial response a moviegoer can make. Simply shrugging off a film by saying, “It’s boring!” is about as uninformative a response as saying, “It’s interesting!” And one should always be suspicious of somebody, in the name of debunkery, telling us that we shouldn’t bother to know something.

Kois’ piece exploits the special status that film enjoys in today’s culture. High and low mingle. Because movies are so accessible, and Hollywood movies are so eager to give us what somebody has decided that we want, coterie tastes are dismissed as snobbism. Things seem different in other arts. Would the Times publish a piece in which someone confessed to finding Tarkovsky’s contemporary, the Soviet composer Sofia Gubaidulina, boring? No, because to talk about her is already to enter a restricted and high-level conversation. It goes without saying that a great many listeners would be bored by her music, but who cares what non-experts think about a modern composer? Film, however, is a free-fire zone; anybody’s opinion is worth a public hearing.

I’ve kept out of the fracas because I thought Kois’ piece was silly-season fluff. Of course I wrote my own replies in my head, such as We used to have a name for this: Philistinism. I also thought that the essay operated in bad faith. Kois wasn’t as apologetic as he tried to seem. He claims humility (he “yearns…to experience culture at a more elevated level”) when really disdaining this area of cinema and considering the people who claim to enjoy it mere poseurs. The exaggerations show, I think, that this is not a serious piece:

Surely there are die-hard Hou Hsiao-hsien fans out there who grit their teeth every time a new Pixar movie comes out.

Surely not.

Still, Kois’ complaint touches on something important about film history. We have a polarized film culture: fast, aggressive cinema for the mass market and slow, more austere cinema for festivals and arthouses. That’s not to say that every foreign film is the seven-and-a-half hour Sátántangó, only that demanding works like Tarr’s find their homes in museums, cinematheques, and other specialized venues. Interestingly for Kois’ case, many of the most valuable movies in this vein don’t get any commercial distribution. The major works of Hou, Tarr, and others didn’t play the US theatre market. Sátántangó is just coming out on DVD here, nearly twenty years after its original appearance. Most of us can’t get access to the most vitamin-rich cultural vegetables, and they’re in no danger of overrunning our diet.

The race is to the slowest

City of Sadness (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1989).

For the historian, the polarization between fast pop movies and slow festival films asks to be explained. My take goes roughly this way.

From the 1940s through the 1960s, certain directors developed a new approach to telling stories. Antonioni, Dreyer, Bergman, and a few others opted for a style that relied on slower pacing and even “dead moments” that seemed to halt the narrative altogether. “Dedramatization,” it was sometimes called, and many rightly considered it a powerful innovation in the history of film as an art. But these films did get a purchase on the international movie market, often for other reasons (sex in Antonioni and Bergman, religiosity in Dreyer). They also came along at a time when there was a niche audience eager to have new cinematic experiences. (On this period see Tino Balio’s Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens.)

But artists being artists, competition grew up. The long take, for instance, got longer and more virtuosic. Miklós Jancsó, shamefully ignored today, made a series of pageants of Hungarian history in superbly sustained, intricate camera movements; some of his films have only twelve shots. But his films are sumptuous compared to what we found elsewhere. From the late 1960s through the 1970s, it seems, a new generation of filmmakers competed to make ever more austere films. They often kept the camera fixed, framed the action at a distance, and sustained the shot for many minutes. The works of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet are the high-water marks of this trend, but there were also Chantal Akerman, Theo Angelopoulos, and even Rainer Werner Fassbinder (Katzelmacher) and Wim Wenders (Kings of the Road). Werner Herzog’s successful career as a documentarist has perhaps let people forget that he once made very slow and demanding films like Fata Morgana; his Heart of Glass, screened in US arthouses in the 1970s, would surely not find a distributor today.

From a marketing standpoint, the avant-garde overplayed its hand. The new austerity came along just when Spielberg and Lucas were reinventing Hollywood. As movies got faster and louder, long-take minimalism looked perversely ascetic. Some of the directors, like Straub and Huillet, remained loyal to their project; others crossed over. It is quite a shift from Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), a 201-minute film mostly about housework, to the musical The Golden Eighties (1986) and A Couch in New York (1996). Likewise with Wenders’ Summer in the City (1970) and Wings of Desire (1987). I happen to admire both strains in these directors’ works, but there’s no doubt which is the more audience-friendly.

Today, directors who persist in long-take, slowly-paced storytelling are aiming chiefly at the festival market, which means that most of their films will be shown theatrically only, to be blunt, in France. But some of the greatest directors of our time, notably Hou Hsiao-hsien, Edward Yang, and Abbas Kiarostami, have done their best work in this mode. The US arthouse market has taken decades to discover them, through more accessible works like Flight of the Red Balloon, Yi Yi, and Certified Copy. Kois confesses to loving Yi Yi, so I’d urge him to look at Yang’s Terrorizers and A Brighter Summer Day, more rigorous but no less gripping films, though they lack the traditional arthouse bait of a charming child. Hou’s Red Balloon also has a cute kid and refers back to an arthouse classic, while Kiarostami, not normally given to couples and romances, offers us in Certified Copy a pleasantly teasing take on Antonioni and Resnais.

Minimalism of the 1970s variety got revived by 1980s American indies, notably Jim Jarmusch, but with more entertainment value. In later years he too crossed over stylistically; however unpredictable the plot maneuvers of Ghost Dog and Broken Flowers, they lack the long takes and open-ended unfolding of time we find in Stranger than Paradise. Even Kelly Reichardt, one of Kois’ targets, doesn’t give us anything like the severity of the 1970s generation. That makes the “purer” films from overseas that persist in this tradition even more off-putting. If Kois can’t take Meek’s Cutoff, as he claims, he’d find Hong Sangsoo (Oki’s Movie) or Liu Jiayin (Oxhide and Oxhide II) cinematic chloroform.

So Kois may assume that “boring” films have persisted in today’s film culture because of snobbism, but there are deeper reasons. The competition among filmmakers to push an aesthetic horizon further, the narrowing of audience tastes, the search for a budget-appropriate niche that could stand in opposition to the visual spectacle of the New Hollywood–these seem to me important factors in making slow movies a ghetto for cinephiles.

Why shouldn’t people follow Kois in giving up their vegetables? No reason, except that they’re missing some worthwhile cinematic experiences. Not all austere movies are good, but viewers who want to expand their cinematic horizons should consider the possibility of learning to look at certain movies differently. Kois can’t see that; he thinks that people who like the movies that bore him are usually phonies. But I believe that some of those admirers have developed a repertory of viewing habits that adjust to different cinematic traditions. If you can like both Stravinsky and rock and roll, why can’t you like Hou and Spielberg?

Look again, closer

Voyage to Cythera (Theo Angelopoulos, 1984).

This is the prospect opened up by Dargis’ latest article. She suggests that Kois’ response isn’t wholly based on taste. It may stem from literally not knowing how to look at certain kinds of movies.

Kois’ article treats most defenses of slow films as a matter of hand-waving and you-see-it-or-you-don’t attitudinizing. Again, he has a point: Those reactions are common, I think. The fact that cinephiles must face is that this sort of film is very difficult to talk about. We can point out the creative choices in Hollywood because narrative in some degree drives everything we see and hear. But when narrative relaxes, most viewers don’t know what to look or listen for.

The problem has haunted me for decades, ever since the 1970s when I took an interest in Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer, and Mizoguchi–all filmmakers felt, at the time, to be slow. I failed to come to grips with the problem in my 1981 book on Dreyer; I even anticipated Kois in calling Gertrud (another item that would never grace theatre screens today) boring–but I took that to be a good thing, as a challenge to conventional viewing habits.

What can I say? I was young. Since then, I think I’ve come up with better ways of talking about the other directors I mentioned, as well as some in their camp, such as Angelopoulos and Hou and Tarr. A lot of my answer comes down to the way, pace Dargis and Smith, they structure our attention.

My arguments are set out in the places I mention in the tailpiece of this entry. In brief, these filmmakers become engaging, even entertaining, when we realize that they are to some extent shifting our involvement from characters and situations to the manner of presentation. Not narrative but narration is what engages us. And we need, as Dargis points out, some schemas for grasping these alternative patterns. We have robust and refined schemas for following a story, but grasping the dynamics of narration, the how as well as the what, takes more practice, and perhaps some instruction from critics.

The process is like taking in an opera on two levels: following the stage action but also registering the patterns, the emotional highs and lows, of the music that accompanies–and sometimes overwhelms–it. Let Papagena and Papageno stammer each one’s name again and again. The repetition isn’t needed for the drama, but it’s thrilling on sheerly musical grounds.

Now imagine that sort of development transposed to cinema, in which we can appreciate, at one and the same time, not only the story’s unfolding but the patterns that present it. The supreme master of this possibility, I think, is Ozu, perhaps cinema’s Mozart. But you can find the same qualities in more somber key elsewhere. For example, in watching Angelpoulos’ Voyage to Cythera, I think that you have to be prepared to see the arrival of track workers in yellow slickers, visible through the speckled window pane in the shot above, as a kind of visual epiphany, the quiet equivalent of a stunt in a summer tentpole picture.

Given a narrative mandate, we’re on the lookout for pictorial factors that affect the dramatic situation. But when narrative slows, other things, maybe not of narrative moment, pop out, like the yellow-garbed train workers on their handcar. At such moments, it’s not that our eyes roam around aimlessly; it’s that the director guides us in a different way, toward a visual search that isn’t wholly driven by plot considerations. Here’s a shot from Ozu’s End of Summer (1961).

The principal action is a party of young people singing. But the faces are no more important than the gleaming drinks on the table, a little suite of colors and shapes that become fascinating in themselves. (For instance, several of the liquids and bottle labels sit along the same horizon line, regardless of how far the drinks are from us.) You don’t discover this half-gag, half-still-life by groping: Ozu has lit it and composed it so that you’re invited to discover it. He has found a way to activate what in most movies would be filler material. And if you think that noticing colors and shapes on the tabletop is just trivial, consider that we enjoy staring at the same sorts of patterns in an abstract Kandinsky. Or is he cultural roughage too?

In an Ozu film, even though he cuts rather fast, we’re given time to see everything. But this isn’t random rummaging. It’s visual exploration guided by Ozu’s decisions about composition, lighting, and color. Something similar, I think, is going on with Tarr, although there it’s more a matter of texture and tactile qualities. His people shamble through mud, oily puddles, dusty corners, and tearing winds. In one shot of Damnation, a rain-soaked wall shrivels to match a wrinkled topcoat.

The story is still going forward, but by turning his protagonist from us and aligning him with the wall, Tarr has given his shot an extra layer of sensuous appeal. Try to remember the way any wall looked in Transformers 3, before it got blasted to rubble.

Slow movies let us look around, and good slow-movie makers give us something to see when we do. But what do we do when these accessory appeals don’t just accompany the narrative but swamp it? What if we lose track of the characters? The film may steer us to pictorial or auditory qualities that take over our perception.

The authorities are looking for a man in the family in Hou’s City of Sadness, but you have to rely almost solely on dialogue to identify what’s going on and who’s speaking.

The sheer pictorial beauty of the shot becomes a sort of anti-narrative pretext. But if you’re alert, you won’t take the plot off the table, because at one crucial moment a figure flashes through the far left background, more or less fully lit, who may be the suspect the cops are seeking.

Sometimes you have to destroy narrative in order to save it.

Hou asks that we engage with his distant, fixed images in a complex way, being patient but vigilant, enjoying abstract geometry while also sustaining old-fashioned suspense. It’s this dynamic between story and style, fastening on plot elements but also discovering accessory pleasures and patterns, that I think constitutes one delight of the sort of films that Kois finds boring.

Add Bresson, Mizoguchi, Dreyer, Tarkovsky, and others to my list of directors whose very different styles invite us to explore what the rapid pace of most narrative cinema refuses to dwell upon. These filmmakers invite us to grasp the space and time of a scene in a fresh way. The details and dimensions of a world surge forward, not simply as a backdrop for characters hurtling toward a goal, but as something valuable in their own right. For some viewers, me included, they do more. They also ask you to transfer those viewing skills to life outside the theatre. They encourage you to find a new way to look at our world.

Not all slow, minimalist movies are good. That’s why I think critics are obliged to rebut Kois with careful analysis, not the gaseous generalities about sublimity and eternal mystery to which we too often resort. Digging deeper, we can not only answer skeptics but expand our understanding of how cinema works. These films have opened windows for many of us. Why should we keep them to ourselves?

First, thanks to Manohla Dargis for enjoyable correspondence about these issues.

Tim Smith’s blog, Continuity Boy, is a good way to keep up with his energetic and expanding research program.

Dargis mentions the invisible gorilla experiments of Chabris and Simons. I talk about their relevance to film here and here.

Kristin has written on comparable matters in Tati; she even wrote an essay on M. Hulot’s Holiday called “Boredom on the Beach.” (It and an essay on Play Time are in her book Breaking the Glass Armor.) Tati’s films, in their spasmodic pauses and shamelessly repeated or sustained gags, could also count as part of the postwar dedramatization trend.